Abstract

Shrikes use their beaks for procuring, dispatching and processing their arthropod and vertebrate prey. However, it is not clear how the raptor-like bill of this predatory songbird functions to kill vertebrate prey that may weigh more than the shrike itself. In this paper, using high-speed videography, we observed that upon seizing prey with their beaks, shrikes performed rapid (6–17 Hz; 49–71 rad s−1) axial head-rolling movements. These movements accelerated the bodies of their prey about their own necks at g-forces of approximately 6 g, and may be sufficient to cause pathological damage to the cervical vertebrae and spinal cord. Thus, when tackling relatively large vertebrates, shrikes appear to use inertia of their prey's own body against them.

Keywords: feeding, Lanius, prey immobilization, shrike

1. Introduction

Shrikes (Passeriformes: Laniidae) are medium-sized (approximately 50 g) predatory songbirds, best known for their tendency to impale their prey [1]. Although the dietary composition of arthropods and vertebrates varies among species [1], most shrikes possess features adapted for carnivory [2]. Vertebrate prey of shrikes range 13–206% of their body mass [3] and probably are more difficult than arthropods to subdue, given their greater strength and potential to inflict harm [4–6]. Their falcon-like upper bills house a sharply hooked tip and tomial projections of the rhamphotheca [2], which are thought to penetrate between cervical vertebrae of their prey and cause partial paralysis [2,4].

Previous workers have described prey-capture and killing behaviour in shrikes, emphasizing the importance of the beak and jaw strength for delivering mortal bites to the neck of their prey [4,5,7,8]. Few, however, have described other aspects of prey processing, such as the vigorous shaking or pounding of prey against the substrate that ensues immediately upon prehension [9–11]. We captured and quantified this underappreciated aspect of shrike predatory behaviour through high-speed videography of captive San Clemente loggerhead shrikes (Lanius ludovicianus mearnsi) attacking vertebrate prey. We measured the frequencies and angular accelerations of these prey-handling movements to address our ultimate objective of understanding the relative roles of beak shape, bite force and prey-handling kinematics in processing vertebrate prey.

2. Material and methods

We filmed complete or partial prey attacks for 37 shrikes at the San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research captive San Clemente loggerhead shrike facility, located on San Clemente Island, CA, USA, where wild-caught endemic shrikes are bred to augment natural populations [12]. Shrikes at this facility are regularly fed live crickets, mealworms, juvenile (11.6 ± 3.6 g (mean ± s.d.), n = 16) and adult (17.3 ± 3.2 g, n = 11) domestic black mice (Mus musculus) and on occasion side-blotched lizards (Uta stansburiana; 3.3 ± 1.3 g, n = 3) within ‘feeding corrals’ [12], which we modified (0.58 m2 plywood floor with 0.3 m tall and 0.6 cm thick Plexiglas walls) for filming. We used 1−2 TroubleShooter HR 3GB (Fastec Imaging™) monochrome high-speed video cameras, with Nikon AF Nikkor 24–120 mm f/3.5–5.6D lenses. We placed cameras at corral-level inside the enclosures approximately 1.2 m from the Plexiglas panels, and operated them from a blind outside using a laptop running MiDAS OS (Xcitex, Inc.). We filmed under natural light, at frame rates of 50−250 fps, shutter speeds of 1−2 × 1/frame rate and pixel resolutions of 640 × 480 to 1280 × 1024. We report data from 28 vertebrate prey-attack video sequences, comprising seven adult (greater than 1 year old) and six juvenile (less than or equal to 1 year old) unrestrained shrikes, that captured prey-shaking behaviour.

We tallied the number of half-oscillations per second: a lateral rotation (roll) of the head about its long axis, starting from a neutral, horizontal position, to the furthest extent of its left or right rotation, and back again to neutral. For comparability with other studies, however, we halved our half-oscillation rates to express frequencies (Hz) as full ‘cycles’. As birds were unrestrained, it was difficult to obtain video of complete cycles of prey-shaking in which the bird was aligned head-on to the camera lens throughout the whole sequence (electronic supplementary material, figure S1). We tracked prey-shaking in the only video suited for detailed analysis by digitizing two landmarks on the shrike's head (the dorsocranial base of the beak and along the dorsocaudal end of the black mask on both sides of the head) and two on the mouse's body (the tip of the rostrum and the base of the tail at the rump) in each of the 64 frames encompassing approximately four oscillatory cycles using ImageJ [13]. We tracked the sequence five times (with images ordered randomly) to account for tracking error. For each frame, we computed the angles of the lines formed between the shrike's beak and each other landmark, and their instantaneous angular velocities (ω) and accelerations (α) (electronic supplementary material, text S1 and figure S1). We then used cross-correlation analysis (set to a ½ cycle ‘window’ of five frames [14]) to determine the lag between the mouse's body and head angles over time. Videos of four additional attacks afforded views of prey-shaking sufficient only for estimating the average angular velocities (ωavg) from the time required to complete an approximately 90° turn of the head. Finally, we estimated the rotational torque (τ) exerted by the body of the mouse about its own neck, from the product of α and the rotational inertia about the centre of mass (ICM) estimated for the average-sized mouse in our study from [15] (additional details in electronic supplementary material, text S2).

3. Results

Shrikes immobilized and killed vertebrate prey by repeatedly biting the head or neck, or by latching onto the nape with their beaks and vigorously shaking them with rapid, long-axis head rolls (figure 1; electronic supplementary material, videos S1–S3). Although this behaviour was not captured by video for all shrikes, 13/14 that were filmed completing their kills performed it at some point during the sequence. The mean ± s.d. cycle frequencies (11.02 ± 3.07 Hz, n = 28 attack sequences by 13 shrikes) and ωavg (57.3 ± 9.5 rad s−1, n = 4 attack sequences by four shrikes) were within ranges reported for non-predatory shaking behaviours of other birds [16] and mammals [17].

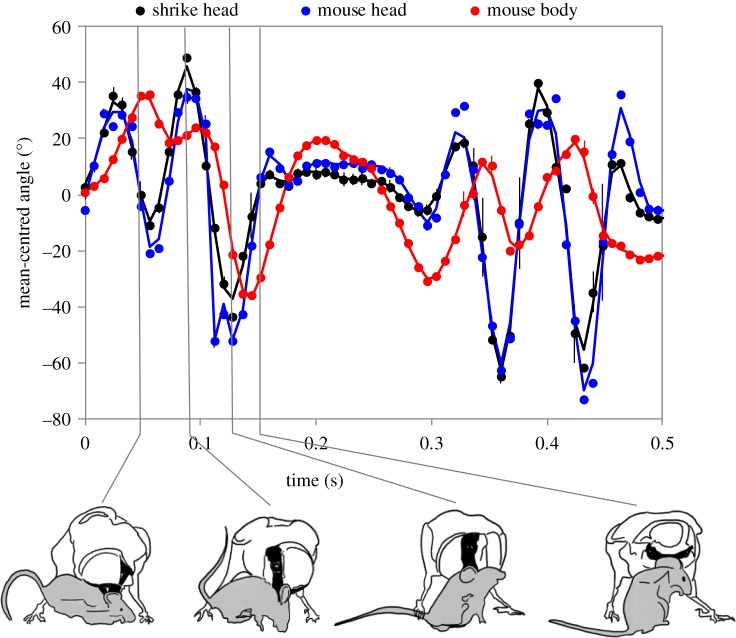

Figure 1.

Approximately four cycles from a representative sequence of an adult male shrike shaking an adult mouse immediately upon capture. Dots are mean-centred angles (± s.d. from five repeated measurements) of the shrike's head (black) and mouse's head (blue) and body (red), computed from landmark coordinates (curves represent low-pass filtered data).

Our kinematic analysis of one approximately 58 g adult male shrike shaking an approximately 17 g adult mouse yielded approximately four cycles of axial head rotations (figure 1). The shrike's head rotations reached mean ± s.d. (n = 5 repeated measures) |peaks| of 68.9 ± 2.5° in amplitude and ω = 71.2 ± 8.7 rad s−1. The mouse's body rotation reached peaks of ω = 39.4 ± 1.4 rad s−1, α = 2696.1 ± 125.2 rad s−2 and 6.0 ± 0.3 g (assuming r = 0.0217 m; electronic supplementary material, figure S2). The peak cross-correlation (r = 0.46 ± 0.03 at a lag of −2 frames for all repeated measures) between the mouse's body and head indicated that the angular movements of the mouse's body lagged those of its head by approximately 0.016 s. Based on the rotational inertia for the average-sized mouse (ICM = 7.99 × 10−6 kg m2), we obtained a peak τ of 0.022 ± 0.001 N m (n = 5 repeated measures) exerted by the body of the mouse about its own neck.

4. Discussion

Adult shrikes rely almost exclusively on their beaks for capturing, processing and ingesting prey. However, an underappreciated component of their prey-processing behaviour is the rapid axial head-rolling movements performed by many of the shrikes we observed upon seizing vertebrate prey. We suggest that the angular accelerations shrikes impart on their prey may be sufficient to cause pathological damage to the spinal column. Furthermore, the motions of the mouse's head and body progressively become shifted out of phase (figure 1), potentially inducing greater compressive forces on the vertebrae from simultaneous flexion and extension of the cervical spine [18].

We estimated a peak instantaneous acceleration corresponding to 6 g for a mouse's body about its neck while being shaken by a shrike. By analogy, victims of low-speed rear-end car crashes experience head accelerations of 2–12 g [19]. These accelerations can result in cervical spine extensions that exceed physiological ranges [20], and damage the cervical facet capsular ligaments that stabilize the zygapophyseal joints between successive vertebrae [21]. In rats, these ligaments rupture at stresses of 2–4 MPa and a mean tensile force of 2.45 N [22]. Assuming that a moment arm equal to the dorsoventral depth (approximately 2.1 mm, estimated from [22]) of the rats' vertebral centrum can place the capsular ligaments into tension upon sufficient acceleration of the body relative to the head, then approximately 0.0051 N m would be required to cause failure (electronic supplementary material, figure S2). Thus, our estimate of torque on the cervical spine of the mouse during the shrike's head-rolling behaviour is approximately four times greater than that required to fail the capsular ligaments of rats approximately 20 times larger than the mice in this study. Cade [4] showed that of the 94 ‘major’ wounds inflicted on prey by Northern Shrikes, 55 were along the middle cervical vertebrae, which coincides with the region of tension and buckling of whiplash-related injuries to human car collision victims [20].

Similar prey-shaking behaviour has been reported for other birds [23–25], crocodilians [26], mammals [27], snakes [28], lizards [29] and has even been inferred in Tyrannosaurus rex [30]. However, save for ‘spinning’ in crocodiles [26], many of these differ substantively from our observations of axial head-rolling in shrikes, in that the prey are beaten against the substrate [23,25], or the action emanates primarily from side-to-side (yaw) movements [28,31]. When combined with the effects of beak shape and bite force [32], this behaviour may help explain how shrikes dispatch relatively larger vertebrate prey than would be expected for their body sizes [2], and provides another example of the importance of prey inertial forces for feeding in predators [26,30].

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Melissa Booker and the U.S. Navy for access to San Clemente Island and logistical support, and to Justyn Stahl and the SCI Shrike Working Group for facilitating this research. Jaelean Carrero, Sarah Sheldon, Angela Sewell, Kathy De Falco and other SDZG staff provided instrumental support. Nick Broccoli assisted with digitizing and Katherine Shaw helped prepare figures. Alejandro Rico-Guevara, Bill Ryerson, Kurt Schwenk, Carl Schlichting, Eric Schultz and Robert Colwell provided critical feedback on data and manuscript drafts. Comments by Jake Socha and two referees vastly improved the manuscript.

Ethics

Live prey were not used solely for the purpose of this study; captive shrikes were routinely fed live prey for ensuring predatory proficiency upon their release into the wild [12], and no additional mice were killed than would have occurred without the videos. We filmed under University of Connecticut IACUC #E08-003 and #E11-014.

Data accessibility

Data and videos accompanying this article have been uploaded as electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contributions

D.S. and M.A.R. conceived the study; S.M.F. facilitated the project, supervised the fieldwork and edited manuscript drafts; D.S. gathered and analysed data; D.S. and M.A.R. wrote the paper. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be held accountable for its content.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

This project was funded by NSF DDIG IOS-1110716.

References

- 1.Yosef R. 2008. Family Laniidae (Shrikes). In Handbook of the birds of the world, vol. 13 (eds del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Christie DA). Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cade TJ. 1995. Shrikes as predators. Proc. West. Found. Vertebr. Zool. 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ingold JJ, Ingold DG. 1987. Loggerhead Shrike kills and transports a Northern Cardinal. J. Field Ornithol. 58, 66–68. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cade TJ. 1967. Ecological and behavioral aspects of predation by the Northern Shrike. Living Bird 6, 43–86. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith SM. 1973. A study of prey-attack behaviour in young Loggerhead Shrikes, Lanius ludovicianus l. Behaviour 44, 113–141. ( 10.1163/156853973X00355) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craig RB. 1978. An analysis of the predatory behavior of the Loggerhead Shrike. Auk 95, 221–234. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busbee EL. 1976. The ontogeny of cricket killing and mouse killing in loggerhead shrikes (Lanius ludovicianus l .). Condor 78, 357–365. ( 10.2307/1367696) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olsson V. 1984. The winter habits of the Great Grey Shrike Lanius excubitor. III. Hunting methods . Vår Fågelvärld 43, 405–414. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller AH. 1931. Systematic revision and natural history of the American shrikes (Lanius). Univ. Calif. Publ. Zool. 38, 11–242. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bent AC. 1950. Life histories of north American wagtails, shrikes, vireos, and their allies. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gwinner E. 1961. Über die entstachelungshandlung des neuntöters (Lanius collurio). Die Volgelwarte 21, 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farabaugh SM. 2013. Final report: 2012 propagation and behavior of the captive population of the San Clemente loggerhead shrike (Lanius ludovicianus mearnsi). San Diego, CA: D.o.D., U.S. Navy, Natural Resources Program, Naval Facilities Engineering Command, Southwest. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rasband WS. 1997–2011 Imagej. Version 1.44p Bethesda, MD: US National Institutes of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 14.PASW. 2007. PASW® advanced statistics 18. Chicago, IL: SPSS, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walter RM, Carrier DR. 2002. Scaling of rotational inertia in murine rodents and two species of lizard. J. Exp. Biol. 205, 2135–2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ortega-Jimenez VM, Dudley R. 2012. Aerial shaking performance of wet Anna's hummingbirds. J. R. Soc. Interface 9, 1093–1099. ( 10.1098/rsif.2011.0608) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dickerson AK, Mills ZG, Hu DL. 2012. Wet mammals shake at tuned frequencies to dry. J. R. Soc. Interface 9, 3208–3218. ( 10.1098/rsif.2012.0429) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swartz EE, Floyd RT, Cendoma M. 2005. Cervical spine functional anatomy and the biomechanics of injury due to compressive loading. J. Athl. Training 40, 155–161. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nordhoff LS. 2005. Motor vehicle collision injuries: biomechanics, diagnosis, and management. Sudbury, Canada: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panjabi MM, Pearson AM, Ito S, Ivancic PC, Wang JL. 2004. Cervical spine curvature during simulated whiplash. Clin. Biomech. 19, 1–9. ( 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2003.09.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brownstein SP, Puglisi BF. 2016. Evaluation of cervical capsular ligament injuries following whiplash injury. Ortho. Rheum. Open Access J. 2, 555599. (doi:10.19080/OROAJ.2016.02.555599) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quinn KP, Winkelstein BA. 2007. Cervical facet capsular ligament yield defines the threshold for injury and persistent joint-mediated neck pain. J. Biomech. 40, 2299–2306. ( 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.10.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beal KG, Gillam LD. 1979. On the function of prey beating by roadrunners. Condor 81, 85–87. ( 10.2307/1367862) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spottiswoode CN, Koorevaar J. 2012. A stab in the dark: chick killing by brood parasitic honeyguides. Biol. Lett. 8, 241–244. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2011.0739) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gotanda KM, Sharpe DMT, Léon LFD. 2015. Galapagos mockingbird (Mimus parvulus) preys on an invasive mammal. Wilson J. Ornithol. 127, 138–141. ( 10.1676/14-055.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fish FE, Bostic SA, Nicastro AJ, Beneski JT. 2007. Death roll of the alligator: mechanics of twist feeding in water. J. Exp. Biol. 210, 2811–2818. ( 10.1242/jeb.004267) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Estes RD. 1991. The behavior guide to African mammals: including hoofed mammals, carnivores, primates. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gans C. 1961. The feeding mechanism of snakes and its possible evolution. Am. Zool. 1, 217–227. ( 10.1093/icb/1.2.217) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loop MS. 1974. The effect of relative prey size on the ingestion behavior of the bengal monitor Varanus bengalensis (Sauria: Varanidae). Herpetologica 30, 123–127. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snively E, Russell AR. 2007. Functional variation of neck muscles and their relation to feeding style in Tyrannosauridae and other large theropod dinosaurs. Anat Rec 290, 934–957. ( 10.1002/ar.20563) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Immelmann K, Beer C. 1989. A dictionary of ethology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sustaita D, Rubega MA. 2014. The anatomy of a shrike bite: bill shape and bite performance in Loggerhead Shrikes. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 112, 485–498. ( 10.1111/bij.12298) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data and videos accompanying this article have been uploaded as electronic supplementary material.