Abstract

Cholesterol is a major regulator of multiple types of ion channels, but the specific mechanisms and the dynamics of its interactions with the channels are not well understood. Kir2 channels were shown to be sensitive to cholesterol through direct interactions with “cholesterol-sensitive” regions on the channel protein. In this work, we used Martini coarse-grained simulations to analyze the long (μs) timescale dynamics of cholesterol with Kir2.2 channels embedded into a model membrane containing POPC phospholipid with 30 mol% cholesterol. This approach allows us to simulate the dynamic, unbiased migration of cholesterol molecules from the lipid membrane environment to the protein surface of Kir2.2 and explore the favorability of cholesterol interactions at both surface sites and recessed pockets of the channel. We found that the cholesterol environment surrounding Kir channels forms a complex milieu of different short- and long-term interactions, with multiple cholesterol molecules concurrently interacting with the channel. Furthermore, utilizing principles from network theory, we identified four discrete cholesterol-binding sites within the previously identified cholesterol-sensitive region that exist depending on the conformational state of the channel—open or closed. We also discovered that a twofold decrease in the cholesterol level of the membrane, which we found earlier to increase Kir2 activity, results in a site-specific decrease of cholesterol occupancy at these sites in both the open and closed states: cholesterol molecules at the deepest of these discrete sites shows no change in occupancy at different cholesterol levels, whereas the remaining sites showed a marked decrease in occupancy.

Introduction

The interplay between cholesterol and ion channels is one of the major mechanisms for regulating ion channel function, with numerous types of ion channels known to be sensitive to the level of cholesterol in the membrane (1, 2, 3). Over the last two decades, an increasing number of studies have shown that in contrast to previous belief, cholesterol regulation of multiple types of ion channels is stereospecific, indicating that direct, specific cholesterol-protein interactions play the central role in these interactions (4, 5, 6, 7, 8). Furthermore, our studies, which focused on inwardly rectifying K+ channels, a major class of K channels, demonstrated not only that the direct interaction of cholesterol suppresses these channels both in mammalian cells (6) and reconstituted liposomes (9) but also that cholesterol can bind to purified bacterial KirBac1.1 channels and that direct cholesterol-KirBac1.1 binding is essential for the functional inhibitory effect (10).

To identify these direct interaction sites on Kir channels, we previously used docking analyses of a cholesterol molecule with a Kir2.1 homology model followed by short-timescale atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to predict cholesterol-binding pockets, which were further validated by site-directed mutagenesis and electrophysiological recordings (11). Using this approach, unbiased for the presence of the known motifs, we identified putative cholesterol-binding regions located at the nonannular hydrophobic pockets of Kir2.1 formed by the transmembrane helices, which do not contain any known cholesterol-binding motifs (11). A similar cholesterol-binding region was identified more recently for Kir2.2 channels (12). However, although our previous work successfully identified a putative binding pocket of amino acid residues important for cholesterol sensitivity, computational experiments were limited to docking analyses and short-timescale MD simulations, the latter used primarily to fine-tune the results of the docking analysis. The limitation of this approach is that docking analyses neglect to consider the effects of the surrounding membrane environment on the energetic favorability of ligand binding sites, potentially biasing results toward pockets within the target protein and failing to consider potential binding sites on the surface of the protein. Furthermore, docking analyses are typically performed with a rigid protein structure, which fails to account for the inherently dynamic nature of proteins in their native environment and the potential for induced-fit ligand binding sites (13, 14). Likewise, these simulations did not allow taking into account diffusion of cholesterol from the membrane to the channel surface, as atomistic simulations typically are limited in scale with respect to both simulation time and simulation size (15, 16). Therefore, in the current study, we explored cholesterol-Kir interactions by employing coarse-grained MD simulations of Kir2.2 in a model membrane environment of cholesterol and palmitoyloleoylphosphatidylcholine (POPC), resulting in a 200-fold increase in timescale from what was studied previously. We chose Kir2.2 because of the recently identified crystal structure (17). We have shown previously that all subtypes of Kir 2 channels (2.1, 2.2, 2.3, and 2.4) are suppressed by cholesterol, with Kir2.1 and Kir2.2 being equally sensitive (6). Moreover, the homology between 2.1 and 2.2 sequences (70% sequence identity) allows for the comparison of cholesterol-binding regions between the two channels.

In the current study, we performed coarse-grained simulations of cholesterol interactions with Kir2.2 channels in both open and closed states of the channel and found that Kir2.2 interacts with an ensemble of cholesterol molecules simultaneously in both states, with some forming transient contacts on the channel surface while others segregate into discrete, more nonannular pockets. Analyzing these findings using a network theory-based approach uncovers to our knowledge novel, discrete cholesterol-binding sites that are different in the open and closed configurations.

Materials and Methods

Establishing the coarse-grained, membrane-embedded Kir topology

The crystal structures for the open and closed states of the Kir2.2 channel (PDB: 3SPI, 3JYC) were obtained from the RCSB (Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics) protein data bank. Residues missing from the protein were modeled with the Modeller9.16 program (18). Each protein structure was then mapped to a coarse-grained topology using the martinize.py script downloaded from the Martini website (http://cgmartini.nl/index.php/tools2/proteins-and-bilayers/204-martinize). Finally, for each state, the coarse-grained Kir protein was embedded in a bilayer containing 1045 POPC molecules and 429 cholesterol molecules (30 mol%) using the insane.py script (http://cgmartini.nl/index.php/tools2/proteins-and-bilayers). We chose POPC as the primary phospholipid for the bilayer, as cholesterol-binding sites have been successfully identified on the basis of using cholesterol in model POPC bilayers (19, 20, 21). The bilayer was constructed such that cholesterol was randomly distributed in the xy plane, subject to a zone of exclusion extending radially 75 Å beyond the Kir channel. Simulations were run using the GROMACS simulation package version 5.0.7 (22) with the Martini 2.2 force field (23). In the Martini scheme, sets of typically four heavy atoms are grouped together to form interaction particles, each with specific particle type that dictates thermodynamic interactions. POPC molecules are represented by choline and phosphate particles, two glycerol linkage particles, and nine particles making up the acyl tails (24). Cholesterol molecules are represented by a polar head group particle, five ring particles, and two tail particles (25).

As coarse graining necessarily reduces the detail of inter-residue interactions that govern higher-order protein structure (e.g., hydrogen bonds), quantitative recapitulation of dynamics can be facilitated by the use of elastic networks to constrain secondary and tertiary structure. Herein, we use the ElneDyn approach (26) to construct a network of elastic bonds between series of Martini backbone particles (representing the Cα atoms). The prevalence and strength of these elastic bonds should be chosen to best reflect the dynamics of the protein in question. We considered two possible approaches to defining a network for each Kir subunit (26). In the first case, we employed a “full” elastic network constructed such that Cα particles within 10 Å of one another (excluding nearest and next-nearest neighbors) were connected by harmonic bonds with a force constant of 1000 kJ/mol nm2. In the second case, we defined the elastic network in a “domain-specific” fashion, treating the transmembrane domain (residues 60–190) and the cytosolic domain of the protein independently. This yielded two elastic networks for each Kir subunit, with Cα particles within each domain connected wherever the 10 Å criterion was satisfied. The residues making up each domain were determined by the CATH database (27). The “full” and “domain-specific” parameterizations, as well as an elastic network-free representation of the protein, were evaluated with regard to their ability to predict the binding behavior of the well-studied Kir ligand phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2).

PIP2 simulations

A three-step equilibration protocol was used, with each step executed for 100 ns with a time step of 20 fs. All three equilibration steps employed a Berendsen pressure coupling algorithm set to 1 atm and a velocity-rescale temperature coupling algorithm set to 310.15 K. A reaction field straight cutoff was used (28). In the first step, position restraints were applied to the backbone particles of Kir2.2, and a flat-bottom position restraint was applied to membrane PIP2 to prevent PIP2-protein contacts. In the second step, the protein position restraints were replaced with a flat-bottom restraint, allowing the protein to move but constraining its lateral diffusion and maintaining separation from PIP2. In the final step, we removed all restraints. Continuing the simulation from this point yielded a 1 μs NPT production run. In the production run, a Parrinello-Rahman pressure coupling algorithm replaces the Berendsen pressure coupling algorithm. Snapshots were taken every 200 ps. This simulation protocol was repeated eight times, with particle velocities reinitialized before each run.

Cholesterol simulations

Simulations involving cholesterol were executed in a similar fashion, with the same three-step protocol followed by a production run. Position restraints were applied to Kir2.2 in the first 100 ns equilibration step, replaced by a flat-bottom restraint in the second. A flat-bottom position restraint was applied to membrane cholesterol in steps 1 and 2 to prevent sterol-protein interaction before protein and membrane equilibration. In the final step, we removed all restraints and subsequently executed a 20 μs NPT production run. We chose a 20 μs runtime to ensure adequate sampling of cholesterol interactions with the channel. A runtime of 20 μs has been shown in a previous work to be a sufficient time for convergence of cholesterol contacts around a membrane-embedded protein (21). As before, the Berendsen pressure coupling algorithm was replaced with a Parrinello-Rahman coupling algorithm. Snapshots were taken every 200 ps. This simulation protocol was repeated four times, in each case with reinitialized velocities.

Quantifying cholesterol-residue contacts

In our study, we describe cholesterol-protein interactions on a per-residue basis and quantify their prevalence in two ways: contact duration and maximal occupancy. Contact duration quantifies the total amount of time individual amino acid residues are within 6 Å of any cholesterol molecule’s center of mass, irrespective of how long each individual pairwise contact lasts. In contrast, maximal occupancy is a measure of the persistence of individual cholesterol-residue interactions. It quantifies the longest continuous contact a given amino acid residue has with any cholesterol molecule. We chose 6 Å as the contact distance because it approximates the first energy minimum of the Leonard-Jones potential in the Martini force field and is a commonly used cutoff for determining contact between particles (19, 29, 30). It is important to note that, given the high mobility of the cholesterol tail, we chose to define the center of mass of a given cholesterol molecule such that the two tail particles of the coarse-grained cholesterol molecule are excluded. As Kir2.2 is a homotetramer, the same residue in each subunit yields an independent measure for maximal occupancy or contact duration in a given simulation. We used the aggregate of these samples across all the simulations to calculate a mean of each metric for each residue.

Characteristic diffusion time of cholesterol

Contacts between cholesterol and membrane proteins can occur purely incidentally because of diffusive collisions as the sterol moves through the membrane. These contacts can be discriminated as those that persist for less than the time required for diffusion over the 6 Å contact distance. To determine this characteristic time, we executed a simulation of 30 mol% cholesterol in a cholesterol-POPC membrane (i.e., absent the embedded protein) and quantified the in-plane diffusivity of the sterol. The characteristic diffusion time was then estimated according to

| (1) |

where D is the lateral diffusion constant of cholesterol and the characteristic diffusion length, LC, is set to the interaction cutoff of 6 Å. This approach was chosen because of the large range of timescales exhibited by cholesterol interacting with the channel and because cholesterol molecules near the channel are not undergoing unrestricted Brownian motion. Calculating a diffusion time in a bare POPC/cholesterol bilayer serves as a conservative lower bound estimate for discriminating diffusive contact from more persistent interactions.

Identifying binding sites by functional network analysis

Network theory is an approach to studying complex systems by representing agents of the system and interactions between them as a graphical model consisting of nodes (agents) and edges (pairwise interactions) (31). When network theory is employed to study protein-ligand binding or its structural sequelae, the edges and nodes making up the network typically map out intra- and intermolecular structure, i.e., ligand-residue or residue-residue proximity (32, 33). The resulting graph is then quantitatively parsed to provide information that supports 1) rigid-body predictive scoring of potential binding sites or 2) characterization of changes in protein structure and dynamics, e.g., conformation change and potential allostery (33). However, relationships between residues can also be defined functionally, guided by some measure of concurrent interaction of groups of residues on a given ligand molecule. This approach has been used, for example, to interpret NMR data to quantitatively assess the importance of individual amino acids in dictating protein-protein interactions and their functional consequences (34). Whereas the structural network approach works well for well-defined binding interactions (e.g., “tight” binding to a single site), functional network analysis helps to filter large datasets and identify the multiple contact regions of varying affinity that may be present on a cholesterol-sensitive protein embedded in a cholesterol-rich membrane. Here, we detail the approach we developed to identify binding sites by rendering this complex, multiagent system as a network of functionally correlated nodes (residues) and edges (connections indicating likelihood of simultaneous sterol contact).

We applied network analysis to those sterol molecules that we defined as binders. Binders are the subset of the 429 cholesterol molecules in our simulation system that, at some point in each 20 μs simulation, met a quantitative criterion for persistence. We chose to classify persistence by a weighted-time metric that selects for those ligands that form prolonged and morphologically stable interactions with the ion channel. Specifically, for each cholesterol interaction, the number of unique residue contacts at each time step during the interaction was counted. Binding events were defined as those interactions in which the total number of unique residue contacts over the duration of the cholesterol interaction exceeded a threshold of 25,000.

For each residue, we created a binary data array that indicated whether or not contact with the sterol in question occurred in each frame of the simulation (1 if present; 0 if absent). For each pair of residues, it was then possible to evaluate the likelihood of concurrent ligand contacts by quantifying similarity of these arrays. We determined similarity by evaluating a ϕ coefficient—analogous to a linear correlation coefficient but applied to dichotomous data. This coefficient and its corresponding p-value permitted us to identify those pairs of residues whose contacts with the sterol are positively correlated with p < 0.05. A positive correlation coefficient indicates a likelihood that two residues will be in simultaneous contact with the bound cholesterol molecule. Conversely, a negative correlation coefficient indicates a likelihood that contact with one residue precludes contact with the other (as would be expected for residues that are not in close proximity).

We collated these findings into an adjacency matrix, i.e., a matrix in which every nonzero entry indicates the positively valued correlation coefficient between residue i and residue j (31). This matrix was then used to create a graphical representation of the contact network. The network depicts every contacting residue as a node, the size of which indicates the relative duration of contact between the sterol of interest and the residue in question. Edges connecting nodes indicate concurrent contacts with the sterol. The edges are weighted according to the relevant correlation coefficient. The graph generated by this method was then segregated by modularity class (35). Modularity is a metric that quantifies the interconnectivity within subregions of a network, with each modularity class being a cluster of nodes that are more connected to each other than they are to nodes of other classes (35). Given our chosen definition of edges, this clustering provides a quantitative means of grouping residues that show a strong tendency to form simultaneous contact with an individual sterol molecule. We identify the binding site as the cluster that includes the largest nodes, i.e., the residues that make the longest contacts. We note here that not all residues in the binding cluster will necessarily exhibit long contact times. If the ligand exhibits considerable mobility within the binding site, the cluster will also include residues whose functionality assigns them to the binding site despite what could be relatively intermittent contact with the sterol.

After employing this approach to identify binding residues for all binding sterols, we used two approaches to determine whether the binding events clustered into one or more characteristic binding sites. First, we evaluated pairwise ϕ coefficients to quantify similarity between networks and examined the statistically significant positive correlations that appeared. Second, we employed a k-means unbiased learning approach to group the networks into clusters characterizing different binding sites (36, 37). The k-means clustering approach can be used to determine both an appropriate number of clusters to describe the data and the particular cluster to which each sterol’s network belongs. For each cluster, the algorithm also returns a centroid, i.e., the group of residues emblematic of the cluster. We used the centroid to define the binding site.

Results

Model validation of domain-specific elastic network

We first considered the parameterization of our coarse-grained simulations of Kir2.2 with respect to the elastic network constraining the protein. We considered three different parameterizations of the elastic network (29, 38, 39): 1) a “full” elastic network, which constrains the protein to its crystal structure; 2) a domain-specific network, which constrains the individual transmembrane and cytosolic domains but connects them via the elastic mesh; and 3) no elastic network. A schematic representing the major domains of the Kir2.2 channel (M1 and M2 transmembrane domain, the pore helix, the slide helix, and the cytosolic domain) are shown in Fig. S1. To determine which approach would be optimal, we validated our model by simulating the interaction of Kir2.2 with PIP2. This interaction has been well studied (30, 40), and the PIP2-bound Kir2.2 crystal structure is known (17). In each simulation, we determine the ligand-binding pocket by identifying the amino acid residues in contact with PIP2. A contact was defined as any instance in which a particle of the PIP2 headgroup was within 6 Å of the center of mass of a Kir residue side chain. These contacts were aggregated over time, and the number of contacts attributed to each residue was expressed as a percentage of total number of ligand-protein contacts. Following the approach described previously by Schmidt et al., we considered binding residues to be those to which we could attribute greater than 5% of total contacts.

Results for each of the three network parameterizations were compared with each other and with the results of atomistic reference simulations reported in Schmidt et al. (Fig. S2). As the figure shows, the binding residues identified from all three parameterizations showed good agreement with the residues of the reference simulations. The simulations using the full elastic network predicted six of the seven residues identified in the reference simulation, with the seventh residue, Trp79, just below the 5% cutoff. Additionally, they identified two residues not predicted in the reference, Ala68 and Gln192. The simulations using no elastic network predicted four of the seven residues identified in the reference simulation, Arg78, Arg80, Lys188, and Lys189, as well as four additional residues not identified in the reference simulations, Arg65, Ile77, Arg190, and Lys220. The simulations using the domain-specific elastic network also identified six of the seven residues identified in the reference simulation, with the seventh (Trp79) being just below the 5% cutoff, as well as one additional residue, Ala68. This is the same residue that was identified with the full elastic network. As the domain-specific elastic network produced the same overlap with the reference simulations while only identifying one “false positive” residue, we chose to use the domain-specific elastic network as the parameterization for Kir2.2 in our cholesterol/POPC simulations.

Kir2.2 dynamically interacts with an ensemble of cholesterol molecules in the membrane environment

In this study, we interrogated the dynamic interactions of Kir2.2 channels with cholesterol molecules in a POPC model membrane at 30 mol% cholesterol, a typical level of cholesterol in mammalian plasma membranes (41). Our simulations show that the Kir2.2 channel is interacting with an ensemble of cholesterol molecules, with multiple cholesterol molecules interacting with each subunit at any given time. Specifically, we found that the channel interacts with an average of 22 ± 1 cholesterol molecules (Fig. 1 A). This is representative of all cholesterol-channel interactions, including very transient interactions on the protein-lipid bilayer interface as well as persistent interactions of cholesterol both on the surface of the protein and within hydrophobic pockets formed in between the helices of the transmembrane domain. A representative snapshot of our simulation system can be seen in Fig. 1 B, showing, from this perspective, eight cholesterol molecules in contact with the channel (other molecules in contact with the protein are obscured from view by the membrane and the channel). Cholesterol molecules were observed to freely associate with and dissociate from the surface of the channel. This unbiased diffusion is evident in Fig. 1 C, which shows a selection of trajectories for individual cholesterol molecules. A detailed analysis of the interacting residues is presented in the next section of this work.

Figure 1.

(A) The average number of cholesterol molecules within 6 Å of the channel over time. Dark line represents the average of all simulations. Individual simulations are shown behind in a lighter shade. (B) A representative snapshot of the simulation, showing cholesterol interacting with the lipid bilayer-exposed surface of the channel. (C) A top-down view of the channel in the membrane, with representative 600 ns trajectories of individual cholesterol molecules showing association with and dissociation from the channel. Each separate cholesterol trajectory is colored separately. (D) The average fractional occupancy of each residue in the TM region (Asp60 to Arg190). (E) Visualization of those residues on the channel with a fractional occupancy of 0.5 or greater. Residues corresponding to one individual subunit are highlighted. (F) The average number of cholesterol molecules in contact with 1–15 separate residues simultaneously. To see this figure in color, go online.

Instead of exclusively localizing in any one location, cholesterol was found to interact with every part of the channel that is exposed to the lipid membrane environment. As a first step to determining whether there are any preferential interactions, we evaluated the fractional occupancy of each amino acid residue in the transmembrane (TM) region. That is, we quantified the amount of time that a given amino acid residue was in contact with any constituent particle of any cholesterol molecule and expressed this total contact time as a fraction of total simulation time (Fig. 1 D). We found that there were 27 different residues with a fractional occupancy of 0.5 or greater. These residues form a largely contiguous region spanning the TM domain of the channel, including residues located in more recessed pockets (Fig. 1 E). Moreover, we found that the number of residues simultaneously in contact with a given cholesterol molecule forms a continuum of behaviors, with some cholesterol molecules being in contact with one or few residues, whereas approximately half of the cholesterol molecules in contact with the channel interact with six or more residues at once (Fig. 1 F).

Segregating Kir2-cholesterol contacts

Molecular simulation studies have predominantly identified ligand-binding residues by calculating the contact time between a ligand and the residues with which it interacts on a target protein (16, 42). As described in the Materials and Methods, contact time can be defined in one of two ways: through contact duration or through maximal occupancy. Recognizing the broad range of timescales characterizing interactions between cholesterol and the protein, we quantified the interactions with both metrics. Both parameters were evaluated for the portion of the channel from residues Asp60 to Arg190, which comprise the TM helices, the slide helix, and the pore domain. Residues outside of this region are not included in the histogram, as they comprise the cytosolic domain and showed no contact with cholesterol.

We found that there were 21 residues that made up the upper quartile of contacts based on contact duration. A visualization of these residues from the top and side views of the channel can be seen in Fig. 2 A. The histogram of contact durations (Fig. 2 D) exhibits predominant peaks corresponding to the two α-helices of the TM domains (Arg80 to Ile107 and Phe156 to Met184), as well a smaller peak corresponding to the slide helix (Met70 to Arg78). Binding residues would typically be identified as those residues with long contact times. Here, we observe a broad range of contact durations across several residues of the TM domain, with no clear statistical outliers. This is perhaps unsurprising, as evaluating total contact duration fails to discriminate between residues that experience very frequent, short-lived sterol contacts (∼1–10 ns) and those that participate in fewer contacts of much longer duration (∼1–10 μs). Notably, although a subset of five of these residues (Leu83, Leu91, Ser93, Ile167, Val168) overlaps strongly with the cholesterol recognition regions identified in our previous study (11), the current analysis shows that several other residues also exhibit abundant interactions with cholesterol.

Figure 2.

Visualization of residues that comprise the upper quartile of contact durations (A), the statistical outliers of maximal occupancy (B), and those residues identified via contact duration that are not maximal occupancy outliers (C). (D) A histogram showing average contact duration for each residue in the TM region (Asp60 to Arg190). (E) A histogram showing average maximal occupancy for each residue in the same region. (F) A plot showing the average number of residue-residue contacts and residue-POPC contacts per nanosecond for residues Asp60 to Arg190. Highlighted residues correspond to those identified in (B; dark circles) and (C; light circles). To see this figure in color, go online.

With regard to maximal occupancy, sterol contact behaviors reveal a heavily tailed distribution from which 13 residues emerge as statistical outliers (τ = 1.5 × interquartile range + third quartile). A visualization of these outlier residues is presented in red in Fig. 2 B, with the corresponding histogram presented in Fig. 2 E. As might be expected, the residues that are characterized by high maximal occupancy (persistent interactions) overlap with and are a subset of the residues characterized by contact duration. In fact, 11 out of 13 residues identified as maximal occupancy outliers are also identified as residues with long contact duration. Only one residue, Ile177, is identified through maximal occupancy and not contact duration.

Notably, there is also a subset of residues identified through the first metric that are not identified via maximal occupancy and do not overlap with previously identified binding sites. These residues are concentrated primarily on the surface of the protein at the protein-lipid bilayer interface (Fig. 2 C). As they appear via the contact-duration criterion but not via maximal occupancy, these residues are characterized as having frequent but relatively short-lived contacts with cholesterol.

Interestingly, we also found that the duration of contact time for individual cholesterol molecules spanned several orders of magnitude, and the aggregate of all cholesterol-channel contacts formed a power-law distribution (Fig. S3). This is very similar to what has been described for cholesterol molecules interacting with B2A receptor (21).

Redefining annularity as a continuum

Previously, the literature has described the location of ligand-binding sites on the TM region of proteins as annular or nonannular (2, 3, 4). However, given the dynamic nature of lipid-protein interactions in the membrane, the definitions of annularity based on static structures might not reflect the complexity of these interactions. Analyzing the annularity of cholesterol-Kir2.2 contacts via dynamic long-term MD simulations allows new insights into these definitions. To this end, we performed a 20 μs simulation of the Kir channel in a pure POPC membrane. Then, for each residue, we evaluated the number of residue-residue contacts and the number of residue-lipid contacts that occurred over the duration of the simulation. For the residues making up the TM region (Asp60 to Arg190), these quantities are presented in Fig. 2 F as a two-dimensional plot indicating the mean number of contacts per nanosecond. The results from our simulations suggest that strictly defining a residue as “annular” or “nonannular” is not a meaningful distinction. When plotted for the entire TM region, it becomes clear that the residues do not neatly segregate into distinctly annular or nonannular regions. Rather, there is a gradient of “annularity” with residues found throughout.

Given this new perspective, we examined the relative annularity of the residues identified from the analyses in Fig. 2, B and C by highlighting their location in Fig. 2 F. Those points highlighted in red are the residues identified in Fig. 2 B as being maximal occupancy outliers, whereas those highlighted in yellow are the residues found in Fig. 2 C as having frequent but short contacts. As can be seen from the plot, the residues themselves exhibit a range of annularity, and the overall trend is that the region of the channel with more persistent cholesterol contacts is decidedly less annular, whereas the residues with frequent, shorter contacts make up a more annular surface on the channel. Thus, our current analysis suggests that, in addition to the nonannular cholesterol-binding regions of Kir2 channels that we and others have identified previously (11, 12), cholesterol may also interact with the annular regions of Kir2 channels.

The microenvironment of cholesterol molecules interacting with the channel

Our simulations point to the fact that Kir2.2-cholesterol interactions exhibit a range of timescales and contact patterns. We decided, therefore, to interrogate the microenvironment of these interactions as defined by the relative degree of cholesterol-phospholipid versus cholesterol-residue contacts. For each cholesterol molecule associating with the channel, we calculated the number of protein residues and POPC particles the cholesterol molecule was in contact with at each instant in time. This information was used to create a population density map indicating the likelihood of a cholesterol molecule being in contact with n residues versus m lipid particles (Fig. 3 A). The figure shows the average number of cholesterol molecules per frame that are experiencing each specific microenvironment condition, visualized with a pseudocolor scheme. First, as expected, there is an inverse relationship between the number of residue contacts versus the number of phospholipid contacts. It is also not surprising to see that the highest frequency region corresponds to those cholesterol molecules experiencing singular residue contacts. We found that the bulk of these single-residue contacts were short lived, lasting for less than 2 ns, which is the characteristic time for membrane cholesterol to diffuse a distance equivalent to the contact cutoff of 6 Å in a protein-free POPC/cholesterol bilayer and is similar to experimental determinations of the lateral diffusion of cholesterol (44, 45). Thus, we consider these to be incidental contacts with the protein due to cholesterol diffusion in the membrane. Details of the estimation of the diffusion time can be found in Materials and Methods.

Figure 3.

(A) A bivariate histogram showing the average number of cholesterol molecules per time in contact with x POPC particles and y separate residues. Cholesterol contacts were segregated into cohorts based on the number of separate residues in simultaneous contact with each interacting cholesterol molecule. Within each cohort, the frequency of each unique residue was calculated, represented as a percentage of total contacts. Examples of these are shown for (B) a histogram of residue contacts for the 11-residue cohort and (C) a histogram of residue contacts for the four-residue cohort. The frequency of each residue cohort was also calculated. The average number of events observed in a 20 μs simulation for each cohort is shown in (D). (E) The average interaction time of each residue cohort is shown in a bar plot on the left. On the right is a boxplot showing interaction times for cohorts 1–8 and cohorts >9. To see this figure in color, go online.

More interestingly, the cholesterol population density map shown in Fig. 3 A suggests the existence of discrete behaviors segregated by number of concurrent residue contacts. We next investigated whether the number of concurrent residue contacts (referred to hereafter as the “residue cohort”) mapped to a particular set of residues in the Kir structure. To do this, we took each residue cohort (1–12 concurrent residue contacts) and calculated the frequency with which each TM residue appeared as a member of that cohort. This frequency was reported as a percentage of total contacts, and the corresponding histograms for each cohort are shown in Fig. S4. Qualitatively, there appear to be at least two general behaviors in the shapes of the histograms. For cohorts of fewer than eight residues, the histograms are characterized by a broad distribution, with few—if any—residues making up more than 5% of the contacts (Fig. S4, Aa–h). For cohorts of greater than 10 residues, there appear to be two narrower sets of well-represented residues, with several being responsible for more than 5% of contacts (Fig. S4, Ai–l). Moreover, we used a χ2 distance metric to quantitatively discriminate between the patterns exhibited by the histograms. The results of this analysis are shown in Fig. S4 B. On this basis, we confirm that there are indeed two characteristic behaviors. Typical examples of these two behaviors are shown in Fig. 3, B and C. One behavior is characteristic of cohorts containing up to eight contact residues, and the other maps to cohorts containing nine or more residues. Notably, the residues in these two groups, cohorts 1–8 and cohorts 9–12, correspond closely to those identified in Fig. 2, C and B, respectively. Nine of the 10 largest peaks in the histograms for cohorts 1–8 are residues with frequent but short-lived contacts, and nine of the 10 largest peaks for cohorts 9–12 are maximal occupancy outliers.

In examining these residue cohorts, we also considered the frequency with which each cohort appears in the simulation and the length of time for which each cohort persists. For every continuous sterol-channel interaction, we determined the duration of contact and calculated an average size for the contact-residue cohort. As Fig. 3 D shows, we found that the vast majority (95%) of cholesterol-channel interactions occur with three or fewer residues. Additionally, we found that when cholesterol interacts with nine or more residues, it leads to more stable interactions, with corresponding contact times that are many orders of magnitude longer than those interactions that involve only a few residues (Fig. 3 E).

Concentration dependence of cholesterol-channel interactions

Previous studies have shown that a 50% depletion of cholesterol from the membrane with methyl-β-cyclodextrin leads to a significant increase in Kir2 channel activity (6, 46). We tested whether a similar twofold decrease in our simulation system affects the number of cholesterol molecules interacting with the channel as well as the pattern of their interactions. We found that when we decreased cholesterol levels from 30 to 15 mol% in the model membrane, the number of cholesterol molecules in contact with the channel also decreased from 22 ± 1, as shown in Fig. 1 A, to 11 ± 1 (Fig. 4 A).

Figure 4.

(A) The average number of cholesterol molecules found to be within 6 Å of the channel over time in simulations containing 15 mol% cholesterol. Dark line represents the average of the simulations. Individual simulations are shown behind in a lighter shade. (B) Bivariate histograms, showing the average number of cholesterol molecules per time in contact with x POPC particles and y separate residues. The top histogram is of simulations containing 30 mol% cholesterol, and the bottom histogram is of simulations containing 15 mol% cholesterol. (C) A two-dimensional (2D) plot of the χ2 distances calculated for each pair of residue cohorts at 15 and 30 mol%. (D) Boxplots showing the interaction times of cohorts >9 (left) and 1–8 (right) for 30 and 15 mol%. To see this figure in color, go online.

Furthermore, we repeated the microenvironment analysis (using the same method as described in Fig. 3) to assess the distribution of contact patterns in the 15 mol% condition. We found that, although the number of overall cholesterol contacts decreased, the inverse relationship between residue and phospholipid contacts and the segregation into two patterns of residue contacts were preserved (Fig. 4 B; see the histograms in Fig. S5 A for 15 mol%, as compared with Fig. S4 A for 30 mol%). The segregation into two patterns under the 15 mol% condition is further validated by a χ2 analysis (Fig. S5 B). Moreover, if we identify the residues dominating the 2–8 residue cohorts and the 9–12 residue cohorts, we find almost complete overlap between the 15 and 30 mol% conditions. We also applied a χ2 analysis comparing the equivalent cohorts at 15 and 30 mol% and quantitatively confirmed the similarity between the patterns of cholesterol-Kir2.2 interactions in membranes containing higher and lower cholesterol levels (Fig. 5 C).

Figure 5.

Network representations of two separate cholesterol-binding events (A and B). Nodes are sized according to total contact time, and edges between nodes are sized according to the corresponding correlation coefficient. (C) A 2D plot of the ϕ coefficient for each pair of binding events, representing the similarity in identified residues. (D) A plot showing the correlations between events with a p-value < 0.05. (E) A visualization of site I and site II. Their shared residue, Ile171, is indicated. (F) A closeup of site I. Subsites Ia and Ib are indicated, as are their shared residues. To see this figure in color, go online.

Although the overall pattern of contacts remained consistent, decreasing the cholesterol level in the membrane results in a decrease in the average contact time for cholesterol molecules interacting with either a small (1–8) or a large (>9) number of residues. This is represented by the boxplots shown in Fig. 4 D. In the left plot, we compare cholesterol contact times for 9–12 cohorts at 30 and 15 mol%. As was shown above, these cohorts represent a relatively small number of events with long contact times (up to almost 20 μs). But, the median contact duration at 15 mol% is significantly shorter than at 30 mol%. Similarly, the 1–8 residue cohorts, which are characterized by much more frequent but shorter cholesterol-Kir2.2 interactions, also show significant decrease in median contact time upon decrease of cholesterol level (right plot, Fig. 4 D).

Cholesterol-recognition region maps to discrete binding sites

Establishing that multiple cholesterol molecules interact with the channel protein concurrently and identifying an array of residues that have frequent and persistent interactions with cholesterol led us to question whether these residues form distinct cholesterol-binding sites or a continuous, cholesterol-favorable environment. To address this question, we posited that a binding site is a set of residues that have a high likelihood of simultaneous contact with a particular bound sterol and used principles from network theory to identify these highly correlated “neighborhoods” of residues. In this analysis, the residue contact pattern for a given sterol is represented as a network of nodes (residues) and edges (connections indicating likelihood of simultaneous contact). Moreover, contact residues can be segregated on the basis of interconnectivity to identify cholesterol-binding sites. We performed this analysis for the persistent binding events, as defined through both the duration of a given cholesterol molecule’s contact and the number of cholesterol-residue interactions present. Through this weighted binding metric, we found 25 such persistent binding events in the 30 mol% simulations. Fig. 5, A and B shows examples of network representations for two separate binding events. In our approach, each network depicts a unique sterol binding event wherein every binding residue is represented as a node, the size of indicates the relative duration of contact between the sterol of interest and the residue in question. Edges connecting nodes indicate concurrent contacts with the sterol and are weighted according to the relevant correlation coefficient, which varies in size. This variation in correlation coefficients reflects the flexibility of cholesterol within an interaction site. An example of this flexibility within a site is shown in Fig. S6.

After applying this approach to all 25 binding sterols, we used two approaches to determine whether these binding events clustered into one or more discrete binding sites. The similarity analysis depicted in Fig. 5, C and D has the sterol binding events grouped according to their k-means clustering, which highlights coherent groups. Visual inspection of the statistically significant ϕ coefficients indicates that there are two separate, persistent binding sites evident in these simulations. These two sites form a contiguous region but are distinct from one another, sharing only a single residue, Ile171. The residues making up these sites are shown in Table 1. One of these binding sites, site I, falls between two subunits, whereas the other, site II, falls between two α-helices of the same subunit. These sites are visualized in Fig. 5 E. Between the two sites, binding at site I was observed to occur more frequently than at site II, with an average rate of 4.25 instances per simulation (17 total events: eight at site Ia, nine at site Ib), whereas only seven instances of binding at site II were observed across the four simulations for an average rate of 1.75. Binding at these two sites was also observed to occur simultaneously. These binding interactions were replicated across different subunits of the protein, confirming their consistency and the possibility of simultaneous occupation across the homotetramer.

Table 1.

Residues Comprising the Discrete Cholesterol-Binding Sites for the Open and Closed States

| Site Ia | Site Ib | Site II |

|---|---|---|

| ∗Leu83, ∗Ser87, Ile167, ∗Cys170, Ile171 | Leu84, Ser87, Leu88, Leu91, Val163, Val164, Ile167 | ∗Ala89, Val92, Ser93, Val168, Ile171, ∗Ile172, ∗Phe175 |

| Site III | Site Ib | Site IV |

|---|---|---|

| Met70, ∗∗Leu83, Leu84, Phe86, ∗∗Ser87, Phe90, ∗∗Cys170, Phe175, Met176, Ile180 | same as above | Met70, Phe71, Cys74, Met82, Leu85, ∗∗Ala89, ∗∗Ile172, ∗∗Phe175, Met176 |

Residues shared by the analogous binding sites in the open (∗) and closed (∗∗) states of the ion channel.

Use of the unbiased clustering approach reinforces the existence of sites I and II and further segregates site I into two subregions that we denote as sites Ia and Ib. These subgroups are also evident in the ϕ coefficient analysis, albeit with moderate intercorrelation. Sites Ia and Ib are located atop one another in the intersubunit groove and share residues Ser87 and Ile167 (Fig. 5 F). The two subsites were occupied at a similar rate in the simulations, with eight binding instances at site Ia and nine at site Ib. We also observed concurrent occupation of the two sites by separate cholesterol molecules.

Cholesterol segregates into different sites in the open and closed states of the channel

To explore the state-dependence of these binding sites, we performed simulations of Kir2.2 in a POPC/cholesterol bilayer using the closed-state crystal structure of the channel (PDB: 3JYC). Similar to the simulations performed for the open state of Kir2.2 described above, we performed three 20 μs simulations of the closed-state channel in a 30 mol% cholesterol bilayer and repeated the analyses performed for the open channel. In the closed state, we again observed simultaneous interaction of Kir2.2 with multiple cholesterol molecules. We observed, on average, 24 separate cholesterol molecules interacting with the channel at each particular time, which is similar to the number of cholesterol molecules interacting with the channel in the open state (22 molecules at any given time). Likewise, these interactions exhibit a broad range of contact times that follow a power-law distribution (Fig. S7).

We then applied our network theory approach to identify the binding sites of cholesterol on the closed-state channel. We found 21 cholesterol-binding events (i.e., interactions meeting our criterion for persistence, as defined in the Materials and Methods). After rendering each of these contacts into a network (see typical examples of the networks for individual binding events in Fig. 6, A and B), we performed similarity analyses to determine the number of unique binding sites (Fig. 6, C and D). Interestingly, we found three distinct binding sites, only one of which (site Ib) also appeared in the open-state simulations (Fig. 6 E). The other two sites, hereafter called sites III and IV, represent sites distinct from the sites Ia and II identified for the open state (Fig. 6, E and F), as determined by the k-means clustering algorithm in the similarity analysis. It is also interesting to note, however, that there is a partial overlap in the residues identified for site Ia in the open conformation and site III in the closed conformation of the channel and in the residues identified for sites II and IV for the open and closed conformations respectively. Specifically, in each pair, Ia versus III and II versus IV, there is an overlap of three residues. The amino acid residues comprising all of the Kir2.2 binding sites in both open and closed conformations of the channel are presented in Table 1.

Figure 6.

Network representations of two separate cholesterol-binding events. (A and B) Nodes are sized according to total contact time, and edges between nodes are sized according to the corresponding correlation coefficient. (C) A 2D plot of the ϕ coefficient for each pair of binding events, representing the similarity in identified residues. (D) A plot showing the correlations between events with a p-value < 0.05. (E) A visualization of site Ib, site III, and site IV. Their shared residues, Met70, Phe71, and Phe175, are indicated. (F) A closeup of sites III and IV, indicating their shared residues. To see this figure in color, go online.

These similarities between sites Ia and III and between II and IV are more apparent in the three-dimensional structures. Site III is located between two subunits, whereas site IV lies on a single subunit, at the cytosolic interface near the slide helix. This arrangement is analogous to the open channel, wherein two sites are situated between two subunits (Ib and III) and one site is situated between the α-helices of a single subunit (IV). Furthermore, visual inspection of these sites shows that the identified sites in the closed state are located shifted downward from their respective analogs in the open state. Specifically, site III lies below site Ia in the intersubunit space. Likewise, site IV is situated below site II, lying in the same groove but shifted closer to the cytosolic interface (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Visualizations of (A) site Ia on the open channel and the analogous (B) site III on the closed channel and (C) site II on the open channel and the analogous (D) site IV on the closed channel. To see this figure in color, go online.

Asymmetric concentration dependence of discrete sites in both the open and closed states

We then repeated the network analysis to interrogate binding events in simulations containing 15 mol% cholesterol for Kir2.2 in its open and closed states.

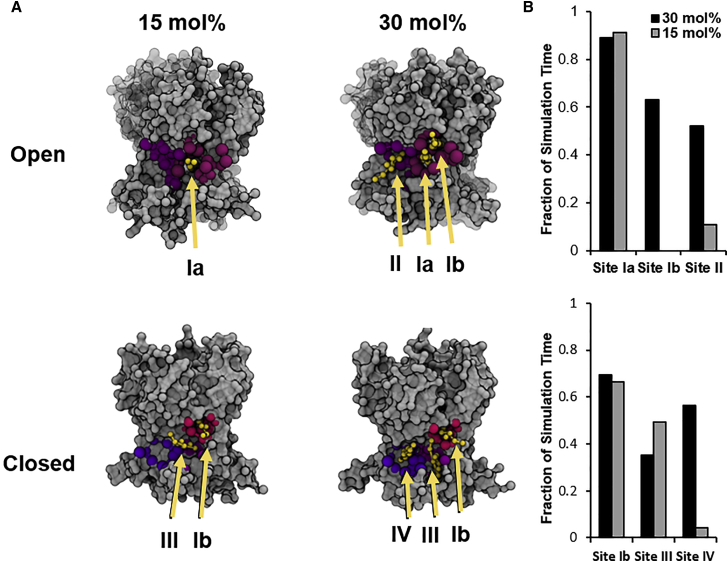

Open state

Using the weighted contact metric, we identified 13 total binding events in the open-state system at 15 mol% as opposed to the 25 such events observed at 30 mol%. Furthermore, the network analysis revealed that decreasing cholesterol content prompted an asymmetric decrease in occupancy of the binding sites. In contrast to the higher cholesterol level, at 15 mol%, the binding of cholesterol occurred preferably and almost exclusively at site Ia, whereas no binding events were observed at site Ib and only a few events at site II (Fig. 5). More specifically, at 15 mol%, 10 binding events were observed at site I and two were observed at site II, resulting in a 5:1 occupancy ratio. At 30 mol% cholesterol, this ratio was 2.4:1. Looking at the subsites, we see even more marked asymmetry. Although sites Ia and Ib were similarly occupied at 30 mol% (2/simulation at Ia and 2.2/simulation at Ib), only site Ia was occupied at 15 mol%. In other words, regardless of whether the open channel is imbedded into the membrane with 30 or 15 mol% cholesterol, site Ia was occupied by a cholesterol molecule 90% of the time. In contrast, the occupancy of sites Ib and II dropped dramatically: for site Ib, the occupancy dropped from 60% to zero, and for site II, it dropped from 50 to 10% (Fig. 8 A). In summary, the reduction of membrane cholesterol content by 50% prompted a loss of site Ib binding events and a marked decrease in site II binding events, leaving site Ia occupancy unchanged.

Figure 8.

(A) Representative snapshots of the TM domains of Kir2.2open in a 15 mol% cholesterol simulation, with cholesterol only occupying site Ia (top left); Kir2.2open in a 30 mol% cholesterol simulation, with cholesterol occupying sites Ia, Ib, and II (top right); Kir2.2closed in a 15 mol% cholesterol simulation, with cholesterol occupying sites Ib and III (bottom left); and Kir2.2closed in a 30 mol% cholesterol simulation, with cholesterol occupying sites Ib, III, and IV (bottom right). The rest of the protein and the membrane lipids are hidden for clarity. (B) Bar plots of the percentage of simulation time cholesterol occupies sites Ia, Ib, and II at 30 and 15 mol% in the open-state simulations (top) and of the percentage of simulation time cholesterol occupies sites Ib, III, and IV at 30 and 15 mol% in the closed-state simulations (bottom). To see this figure in color, go online.

Closed state

In the simulations of the closed-state channel, we also see a similar asymmetric concentration dependence of the discrete binding sites. We observed that site Ib was occupied 60% of the time regardless of the concentration, which is comparable to its occupancy at 30 mol% in the open-state simulations. Thus, cholesterol occupancy of site Ib is concentration dependent in the open state but not in the closed state of the channel. Likewise, occupancy at site III, which is situated between two subunits similarly to site Ia in the open state, remained unchanged between the two concentrations, staying at 40–50%. However, cholesterol at site IV, which is analogous to site II in the open state, showed a marked decrease from 56 to 5% occupancy. Thus, the occupancy of the single subunit site is sensitive to cholesterol concentration in both the closed and open states. The differences between the binding sites in the open and the closed states of Kir2.2 provide a new window into understanding the dynamics of these interactions, as further discussed in the next section.

Discussion

Our coarse-grained simulations of Kir2.2 showed that the entire TM region of the channel is in dynamic contact with cholesterol and that the interactions between Kir and cholesterol are ever present. This is a departure from previous investigations of cholesterol-ion channel interactions, which have conceptualized the process from the perspective of ligand-pocket binding rather than treating cholesterol as a native membrane element with a range of potential interaction sites and interaction times (8, 11, 12, 47, 48, 49, 50). The larger simulation size compared to atomistic simulations and the dynamic nature of the coarse-grained (CG) simulations allowed us to consider the channel in relation to its surrounding membrane environment, leading to the identification of a variety of both annular and nonannular interactions between cholesterol and the channel. Moreover, the microsecond timescale of these CG simulations also allowed us to analyze the dynamics of cholesterol-channel contacts, which was essential for discovering how cholesterol-Kir2.2 interactions are altered with physiologically relevant changes in the level of membrane cholesterol. Our main findings are 1) multiple cholesterol molecules interact with the Kir2.2 channel concurrently; 2) cholesterol-Kir2.2 interactions can be segregated into persistent, “rare” binding events at deeply embedded, nonannular binding pockets and transient, high-frequency events localized at the lipid bilayer-channel interface; and 3) that a decrease in membrane cholesterol results in a proportional decrease in the number of cholesterol molecules interacting with the channels and a corresponding decrease in interaction time. Furthermore, combining the long-timescale simulations with our network analysis led us to identify discrete cholesterol-binding sites within the general cholesterol-binding region, the locations of which change depending on the conformational state of the channel. We also discovered significant differences in the sensitivity of these sites to the lowering of cholesterol levels in the membrane.

Two general approaches were used in previous investigations to identify cholesterol-binding pockets on ion channels: identifying known cholesterol-binding motifs, such as CRAC and CARC in the sequence of the protein (2, 51, 52), or performing a docking of cholesterol to the channel structure unbiased to the presence of known motifs (11, 53, 54). The cholesterol-recognition amino acid consensus motif (CRAC) and its mirror image CARC have been identified as major elements involved in cholesterol binding in a variety of TM proteins (2, 51, 55). These motifs and their energetic requirements were explored in detail in nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) (51). Using the first approach, validated by site-directed mutagenesis and functional studies, CRAC/CARC-related cholesterol-binding sites were identified in TRPV1 channels (47), BK channels (48), P2X7 (56), and voltage-gated potassium channels Kv1.3 (50). However, a recent analysis of the database of multiple protein structures complexed with cholesterol revealed that the three known cholesterol-binding motifs (CRAC, CARC, and cholesterol consensus motif) only make up a subset of cholesterol-binding regions, whereas multiple identified cholesterol-protein complexes did not feature any of these motifs (57). An alternative approach uses a combination of unbiased docking analysis with MD simulations, wherein the docking of cholesterol is performed on the entire channel structure and the resulting conformations are tested for stability by the simulations (11, 53, 54, 58). Using this approach, cholesterol-binding regions were identified in the voltage-dependent anion channel, nAChR, and GABAA receptors (53, 54, 58). Furthermore, we combined this approach with further validation by site-directed mutagenesis and electrophysiology to identify cholesterol-binding regions of Kir2.1 channels (11). Interestingly, the cholesterol-binding regions identified by the unbiased docking analysis in these studies did not contain any of the known cholesterol-binding motifs, underscoring that these motifs do not comprehensively define cholesterol-ion channel interactions.

Overall, although these two methods can successfully identify clusters of “cholesterol-binding” residues, the relatively static nature of these two approaches cannot take into account a key molecular feature—interaction dynamics and timescale. Previous studies from our lab and others therefore provided no information about the dynamics of cholesterol-Kir2 interactions (11, 12). Moreover, these earlier studies could not explore cholesterol interactions with the surface of the protein on the channel-lipid bilayer interface. In the current study, our CG simulations provide, to our knowledge, new insights into cholesterol-Kir interaction sites by considering the channel in dynamic contact with the lipid bilayer environment. It is important to note that, as a coarse-grained model, there are certain built-in limitations to using the Martini force field. The 4-to-1 mapping of heavy atoms into interaction particles reduces the degrees of freedom in a simulation and reduces the computational expense of executing molecular simulations. This allows for accessing longer timescales but leads to a smoothing of the energetic landscape and a loss of finer molecular detail. Likewise, using the Martini force field for protein simulations requires an elastic network to be parameterized, restricting the conformation of the protein to a single state and preventing the direct observation of conformational changes. These are important considerations to make when interpreting the results of a CG simulation, and a number of recent reviews detail the strengths and limitations of the Martini model and specifically the use of the Martini model for protein-lipid and protein-sterol interactions (16, 59, 60). However, although there are limitations, simulations using the Martini model have been successful in identifying lipid binding sites on membrane-embedded proteins that were further corroborated through crystallography experiments (61, 62). Consequently, these types of CG simulations have seen a rapid expansion in their use for determining the molecular mechanics of lipid membrane-protein interactions: in the context of cholesterol, interaction sites have been determined for several types of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) as well as nAChR and serotonin receptors (20, 21, 63, 64). We found here that the entire TM region of the channel was accessible to cholesterol and consequently that this region was fully sampled by cholesterol molecules. We observed that individual molecules can undergo both rapid (ns) and slow (μs) exchange with various sites on the protein and noted that “cholesterol-sensitive” residues interact with cholesterol with nonuniform lengths of time and frequency, similar to what has been hypothesized for GPCRs (43). Given the vast excess of cholesterol molecules versus Kir channels in vivo, transient contacts of many cholesterol molecules with the channel are likely an unavoidable feature of membrane-embedded proteins, which has been noted earlier for GPCRs (42). Furthermore, the extent to which cholesterol samples the entire TM surface of Kir is in line with what has been recently observed in simulations of cholesterol and A2A adenosine receptors (21), lending further credence to the idea that the complex milieu of cholesterol molecules surrounding ion channels must be considered altogether and from a dynamic perspective to fully appreciate the sterol’s regulatory effect on ion channels. More specifically, we used two types of analysis to elucidate the nature of cholesterol-Kir2.2 interactions: analyzing the dynamics of the interactions (occupancy times and the frequency of the cholesterol-Kir2.2 contacts) and analyzing the microenvironment of the interacting cholesterol molecules in terms of the ratio of cholesterol-phospholipid versus cholesterol-residue interactions. Interestingly, both approaches converged to reveal two types of cholesterol-Kir2.2 interactions: 1) persistent events lasting multiple microseconds that occur in between the TM helices, which correspond to the nonannular sites identified in our previous studies; and 2) short-lived events more at the surface of the channel-lipid bilayer interface that have not been identified before. We propose that transient binding events on the surface of the protein might constitute the pathway for cholesterol entering the deeper pockets of the channel. More studies are needed to investigate this hypothesis.

Furthermore, our current dynamic analysis provides strong evidence for our previous hypothesis that cholesterol explores a large conformational space within its binding regions on the channel. Although previously this hypothesis was based on identifying multiple overlapping, predicted poses of cholesterol bound to the channel, here we observed this phenomenon directly. This binding flexibility seems to be a common feature of many cholesterol-protein interactions, as the same mobility has been noted for cholesterol interactions with β2-andrenergic receptors and A2A adenosine receptors, among others (20, 21, 42). Given this flexibility of cholesterol-Kir contacts, we applied principles from network theory to address the challenge of identifying the amino acid residues that comprise discrete binding sites. By defining residue relationships based on likelihood of concurrent interaction with the same ligand molecule, we were able to capture those residues that were playing a role in cholesterol binding, even when the cholesterol molecule in question was highly flexible in its pocket and did not interact with every binding residue simultaneously. This differs from previous uses of network theory in the study of protein-ligand binding, which have predominantly created interaction networks from residue-residue or residue-ligand proximity (32, 33, 65). The results from our network theory approach showed that there are in fact four discrete sites: sites I and II, which were found in the open-state simulations, and sites III and IV, which were found in the closed-state simulations and characterized by distinct sets of binding residues. Furthermore, site I can contain simultaneous binding of two cholesterol molecules and can therefore be divided into two subsites, Ia and Ib, a division that was supported by application of unbiased clustering.

Identification of these sites provides a significant improvement compared to previously identified cholesterol-binding regions of Kir2 channels. Specifically, in our previous study, we identified a relatively large area between the TM helices of Kir2.1 within the hydrophobic core of the lipid bilayer as a “cholesterol-binding region” (11). A similar region was also identified in Kir2.2 (12). Here, using the network analysis, we could identify discrete cholesterol-binding sites within this previously identified region. Notably, we also found that the presence of these specific sites was dependent on the conformational state of the Kir2.2 channel.

It is also interesting to note that in comparing the binding sites in the open- and closed-state simulations, there is partial overlap in the identified residues as well as close physical proximity between Ia in the open and III in the closed state and II in the open and IV in the closed state. More specifically, sites II and IV both sit on a single subunit and share three residues, whereas sites Ia and III both sit between two subunits, near the cytosolic interface, and share three residues. Furthermore, it appears that both of the sites identified in the closed state simulations are shifted downward and closer to the cytosolic interface with respect to the sites identified in the open-state simulations.

This study also provides the first structural insights, to our knowledge, into how lowering the cholesterol level of the membrane affects cholesterol’s interactions with its specific binding sites on an ion channel. When cholesterol levels in the membrane are decreased twofold from 30 to 15 mol%, we see a proportional decrease in the number of cholesterol molecules interacting with the channel. With respect to the microenvironment of interacting cholesterol molecules, the general pattern of those interactions remains the same: segregation into rare, persistent, nonannular binding events and more frequent annular binding. In addition to the decrease in the number of cholesterol molecules interacting with the channel, we also see a decrease in the average contact time for interacting cholesterol in cholesterol-depleted conditions. Most importantly, upon cholesterol depletion, we observed significantly different changes in occupancy of the distinct cholesterol-binding sites in both the open and closed states. Specifically, we found that for the open channel, site Ia is occupied equally at both 30 and 15 mol%, whereas site II and site Ib see a dramatic decrease in occupancy upon cholesterol depletion, with site Ib disappearing entirely. Similarly, for the closed channel, sites Ib and IV are equally occupied at both 30 and 15 mol%, whereas the occupancy of site III drops dramatically at 15 mol%. This asymmetry in occupancy implies a difference in cholesterol’s affinity for these sites, possibly dictated by cholesterol-mediated perturbations to the conformation of the protein.

Finally, based on the proximity of cholesterol-binding sites in the open and closed states of Kir2.2 described above and their occupancy depending on cholesterol concentration, we would like to suggest a potential mechanism for cholesterol regulation of these channels: we suggest that cholesterol occupancy of sites III and IV stabilizes Kir2.2 in the closed state, whereas occupancy of sites I and II does not. It is possible that cholesterol may migrate from sites Ia and II to sites III and IV as the channel conformation changes from open to closed, stabilizing the closed state. Furthermore, the loss of cholesterol binding from sites Ib and II that follows a decrease in cholesterol level of the membrane, which is known to increase Kir2.2 activity, is expected to stabilize the channel in the open state. Similarly, the loss of cholesterol binding from site IV may destabilize the closed state, leading to further loss of cholesterol binding from site Ib and migration of cholesterol from site III to site Ia, resulting in a stabilized open state. Clearly, this is just a hypothetical model that needs to be addressed in the future studies. Some further insights on the effect of these binding sites on the structural stability of Kir2.2 might be obtained by utilizing atomistic simulations. Altogether, this analysis provides further foundation for experimental studies, including crystal structures of the channel in different cholesterol environments.

Author Contributions

N.B., I.L., and B.S.A. wrote the manuscript; N.B., I.L., and B.S.A. designed research; N.B. performed research; N.B., M.A.A.A., and B.S.A. contributed analytic tools; N.B. and B.S.A analyzed data.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institute of Health grants HL-073965 and HL-083298 (I.L.) and T32 HL-82547 (M.A.A.A.)

Editor: D. Peter Tieleman.

Footnotes

Seven figures are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(18)30972-X.

Contributor Information

Belinda S. Akpa, Email: bsakpa@ncsu.edu.

Irena Levitan, Email: levitan@uic.edu.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Rosenhouse-Dantsker A., Mehta D., Levitan I. Regulation of ion channels by membrane lipids. Compr. Physiol. 2012;2:31–68. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c110001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fantini J., Barrantes F.J. How cholesterol interacts with membrane proteins: an exploration of cholesterol-binding sites including CRAC, CARC, and tilted domains. Front. Physiol. 2013;4:31. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levitan I., Singh D.K., Rosenhouse-Dantsker A. Cholesterol binding to ion channels. Front. Physiol. 2014;5:65. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romanenko V.G., Rothblat G.H., Levitan I. Modulation of endothelial inward-rectifier K+ current by optical isomers of cholesterol. Biophys. J. 2002;83:3211–3222. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75323-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Addona G.H., Sandermann H., Jr., Miller K.W. Low chemical specificity of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor sterol activation site. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1609:177–182. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00685-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romanenko V.G., Fang Y., Levitan I. Cholesterol sensitivity and lipid raft targeting of Kir2.1 channels. Biophys. J. 2004;87:3850–3861. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.043273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bukiya A.N., Singh A.K., Dopico A.M. The steroid interaction site in transmembrane domain 2 of the large conductance, voltage- and calcium-gated potassium (BK) channel accessory β1 subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:20207–20212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112901108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbera N., Ayee M.A.A., Levitan I. Differential effects of sterols on ion channels: stereospecific binding vs stereospecific response. Curr. Top. Membr. 2017;80:25–50. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctm.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh D.K., Rosenhouse-Dantsker A., Levitan I. Direct regulation of prokaryotic Kir channel by cholesterol. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:30727–30736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.011221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh D.K., Shentu T.P., Levitan I. Cholesterol regulates prokaryotic Kir channel by direct binding to channel protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1808:2527–2533. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenhouse-Dantsker A., Noskov S., Levitan I. Identification of novel cholesterol-binding regions in Kir2 channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:31154–31164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.496117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fürst O., Nichols C.G., D’Avanzo N. Identification of a cholesterol-binding pocket in inward rectifier K(+) (Kir) channels. Biophys. J. 2014;107:2786–2796. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.10.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sousa S.F., Fernandes P.A., Ramos M.J. Protein-ligand docking: current status and future challenges. Proteins. 2006;65:15–26. doi: 10.1002/prot.21082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang S.Y., Zou X. Advances and challenges in protein-ligand docking. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010;11:3016–3034. doi: 10.3390/ijms11083016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ingólfsson H.I., Lopez C.A., Marrink S.J. The power of coarse graining in biomolecular simulations. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2014;4:225–248. doi: 10.1002/wcms.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hedger G., Sansom M.S.P. Lipid interaction sites on channels, transporters and receptors: recent insights from molecular dynamics simulations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1858:2390–2400. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen S.B., Tao X., MacKinnon R. Structural basis of PIP2 activation of the classical inward rectifier K+ channel Kir2.2. Nature. 2011;477:495–498. doi: 10.1038/nature10370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Webb B., Sali A. Protein Structure Prediction. Springer; 2014. Protein structure modeling with MODELLER; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sengupta D., Chattopadhyay A. Identification of cholesterol binding sites in the serotonin1A receptor. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116:12991–12996. doi: 10.1021/jp309888u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Genheden S., Essex J.W., Lee A.G. G protein coupled receptor interactions with cholesterol deep in the membrane. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2017;1859:268–281. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rouviere E., Arnarez C., Lyman E. Identification of two new cholesterol interaction sites on the A2A adenosine receptor. Biophys. J. 2017;113:2415–2424. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abraham M.J., T. Murtola, R, Lindahl E. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015;1:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Jong D.H., Singh G., Marrink S.J. Improved parameters for the martini coarse-grained protein force field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013;9:687–697. doi: 10.1021/ct300646g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marrink S.J., Risselada H.J., de Vries A.H. The MARTINI force field: coarse grained model for biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:7812–7824. doi: 10.1021/jp071097f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ingólfsson H.I., Melo M.N., Marrink S.J. Lipid organization of the plasma membrane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:14554–14559. doi: 10.1021/ja507832e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Periole X., Cavalli M., Ceruso M.A. Combining an elastic network with a coarse-grained molecular force field: structure, dynamics, and intermolecular recognition. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009;5:2531–2543. doi: 10.1021/ct9002114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sillitoe I., Lewis T.E., Orengo C.A. CATH: comprehensive structural and functional annotations for genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D376–D381. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Jong D.H., Baoukina S., Marrink S.J. Martini straight: boosting performance using a shorter cutoff and GPUs. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2016;199:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Jong D.H., Periole X., Marrink S.J. Dimerization of amino acid side chains: lessons from the comparison of different force fields. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012;8:1003–1014. doi: 10.1021/ct200599d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt M.R., Stansfeld P.J., Sansom M.S. Simulation-based prediction of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate binding to an ion channel. Biochemistry. 2013;52:279–281. doi: 10.1021/bi301350s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borgatti S.P., Halgin D.S. On network theory. Organ. Sci. 2011;22:1168–1181. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu G., Zhou J., Shen B. The topology and dynamics of protein complexes: insights from intra-molecular network theory. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2013;14:121–132. doi: 10.2174/1389203711314020004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Ruvo M., Giuliani A., Di Paola L. Shedding light on protein-ligand binding by graph theory: the topological nature of allostery. Biophys. Chem. 2012;165–166:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurzbach D. Network representation of protein interactions: theory of graph description and analysis. Protein Sci. 2016;25:1617–1627. doi: 10.1002/pro.2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blondel V.D., Guillaume J.-L., Lefebvre E. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J. Stat. Mech. 2008;2008:P10008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nasrabadi N.M. Pattern recognition and machine learning. J. Electron. Imaging. 2007;16:049901. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bishop C.M. Oxford University Press, Oxford; 1995. Neural Networks for Pattern Recognition. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monticelli L., Kandasamy S.K., Marrink S.J. The MARTINI coarse-grained force field: extension to proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:819–834. doi: 10.1021/ct700324x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siuda I., Thøgersen L. Conformational flexibility of the leucine binding protein examined by protein domain coarse-grained molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Model. 2013;19:4931–4945. doi: 10.1007/s00894-013-1991-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]