Abstract

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a physical and biochemical barrier that precisely controls cerebral homeostasis. It also plays a central role in the regulation of blood-to-brain flux of endogenous and exogenous xenobiotics and associated metabolites. This is accomplished by molecular characteristics of brain microvessel endothelial cells such as tight junction protein complexes and functional expression of influx and efflux transporters. One of the pathophysiological features of ischemic stroke is disruption of the BBB, which significantly contributes to development of brain injury and subsequent neurological impairment. Biochemical characteristics of BBB damage include decreased expression and altered organization of tight junction constituent proteins as well as modulation of functional expression of endogenous BBB transporters. Therefore, there is a critical need for development of novel therapeutic strategies that can protect against BBB dysfunction (i.e., vascular protection) in the setting of ischemic stroke. Such strategies include targeting tight junctions to ensure that they maintain their correct structure or targeting transporters to control flux of physiological substrates for protection of endothelial homeostasis. In this review, we will describe the pathophysiological mechanisms in cerebral microvascular endothelial cells that lead to BBB dysfunction following onset of stroke. Additionally, we will utilize this state-of-the-art knowledge to provide insights on novel pharmacological strategies that can be developed to confer BBB protection in the setting of ischemic stroke.

Keywords: blood-brain barrier, endothelial cell, oxidative stress, tight junctions, transporters

INTRODUCTION

Stroke is a primary cause of morbidity and mortality (14). In the United States, there are approximately 795,000 new incidences of stroke each year (14). On average, a stroke occurs once every 40 seconds and someone dies from a stroke every 4 minutes (14). Globally, stroke is the second leading cause of death behind only ischemic heart disease (14). Several factors have been identified that increase risk of stroke including diabetes mellitus, history of transient ischemic attacks, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, cigarette smoking, and low serum concentrations of HDL cholesterol (14). Clearly, stroke is a significant public health concern that is in great need of novel treatment paradigms.

Of all strokes, 86% are ischemic in nature (14). The pathophysiology of ischemic stroke is characterized by impaired blood supply that greatly reduces delivery of oxygen and other essential nutrients (i.e., glucose) to an affected brain region. This results in an irreversibly damaged ischemic core and potentially salvageable surrounding tissue known as the penumbra (84). In the central nervous system (CNS), oxygen and glucose are required to enable sufficient production of ATP for physiological cellular functions. These nutrients are used for maintenance of intracellular homeostasis and to ensure that monovalent/divalent ion gradients (i.e., Na+, K+, Ca2+) do not collapse (4, 145). Reduced ATP levels in the ischemic brain can lead to ion gradient failure via impaired functioning of Na+-K+-ATPase and Ca2+-ATPase activity, which allows cations (i.e., Na+) to accumulate within the cell. Additionally, activity of endothelial ion transporters [i.e., Na-K-Cl cotransporter (NKCC), Na/H exchanger (NHE)] is stimulated during of ischemic stroke, a process that contributes to increased secretion of Na+, Cl−, and water across the blood-brain barrier (BBB) (106). Extracellular fluid then follows this net movement of sodium ions, a pathophysiological process that results in cytotoxic edema. It is also paramount to note that stimulation of NKCC and NHE can lead to Na+ accumulation in endothelial cells themselves. This occurs during ischemic stroke when increased uptake of Na+ ions at the luminal membrane of the endothelial cell is not counterbalanced by effective Na+ extrusion mediated by Na+-K+-ATPase, a mechanism that can lead to endothelial cell swelling and contribute to BBB breakdown (106). Na+ in the CNS following an ischemic insult may also be mediated by altered functionality of ion channels expressed at the level of the BBB (22). Additionally, Na+ uptake causes plasma membrane depolarization, leading to opening of voltage-gated cation channels and reverses the direction of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, bringing additional Ca2+ into the cell (69, 87). It should be noted that the rapid increase in intracellular Ca2+ triggers substantial neuronal release of excitatory neurotransmitters (i.e., glutamate, dopamine). High concentrations of glutamate and dopamine are toxic to neurons and lead to increased neuronal cell death and development of an infarction (4). Glutamate excitotoxicity coupled with cellular depolarization is particularly injurious to the brain due to overstimulation of metabotropic glutamate receptors as well as extensive activation of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) and N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, events that result in disruption of CNS calcium homeostasis (9, 145). Cerebral ischemia causes a rapid reduction in ATP reserves, which occurs in an effort to sequester intracellular Ca2+ concentrations and by Na+-K+-ATPase attempting to restore Na+ and K+ gradients (116). Ca2+ sequestration is ultimately futile and calcium overload leads to excessive stimulation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent enzymes such as nitric oxide synthase as well as multiple Ca2+-dependent enzymes such as proteases, phospholipases, and endonucleases (36). Increased activation of such catalytic enzymes can cause protein degradation, phospholipid hydrolysis, and DNA damage as well as disruption of cellular signaling and enzymatic reactions. Generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide anions increases dramatically during ischemia due to high Ca2+-induced mitochondria dysfunction and impairment of ROS defense enzymes. Neurons in the ischemic core that have died via necrotic processes release cytotoxic elements into the interstitial space that can penetrate adjacent neurons through damaged plasma membranes caused by lipid peroxidation and activity of phospholipases. In addition to ROS generation, cerebral ischemia is accompanied by widespread inflammation demarcated by cytokines, adhesion molecules, and other inflammatory mediators (55).

It is well established that the BBB is disrupted during ischemic stroke, which can lead to vasogenic edema formation and hemorrhagic transformation (8, 98, 147). The BBB is an essential physical and biochemical barrier that separates the CNS from the systemic circulation. Primary functions of the BBB include, but are not limited to, control of CNS homeostasis and protection of brain tissue from exposure to potentially toxic substances. Therefore, BBB disruption following ischemic stroke can have severe pathological consequences that can exacerbate brain injury and contribute to cognitive impairment. Current knowledge in the BBB field has uncovered a multiplicity of molecular pathways that can lead to significant changes at the level of the cerebral microvasculature. Indeed, identification and characterization of these molecular pathways has provided opportunities to develop novel therapeutic approaches to protect against BBB dysfunction in the context of ischemic stroke. In this review, we will outline molecular characteristics of the BBB and how these features of the microvascular endothelial cell are modulated in the setting of ischemic stroke. We will also provide new perspective on therapeutic strategies that can be developed to confer vascular protection in ischemic stroke by targeting specific components of the BBB.

THE BBB AND THE NEUROVASCULAR UNIT

The BBB primarily exists at the level of the brain microvascular endothelium; however, endothelial cells are not intrinsically capable of forming a “barrier.” Indeed, development of barrier characteristics in cerebral endothelial cells requires coordinated cell-cell interactions and signaling from glial cells (i.e., astrocytes, microglia), pericytes, neurons, and extracellular matrix (16, 20). Such an intricate relationship implies existence of a “neurovascular unit (NVU).” The concept of the NVU emphasizes that the dynamic BBB response to stressors requires coordinated interactions between various CNS cell types and structures. In fact, damage to the BBB is an early pathological event in ischemic stroke that occurs prior to onset of neuronal injury (30, 132). In this review, we will focus on molecular constituents of brain microvascular endothelial cells and how these features of the BBB are modulated in ischemic stroke. The role of other cellular components of the NVU in stroke pathophysiology has been reviewed in detail elsewhere (54, 79, 127).

PHYSIOLOGICAL FUNCTIONS OF THE BBB

The physiological roles of the BBB have been discussed by brain barrier scientists in several excellent publications (1, 2, 28, 47, 103). In brief, the BBB functions to supply brain tissue with essential nutrients and to efficiently control elimination of waste materials from the brain. It expresses a multiplicity of ion transporters and channels that regulate CNS ion concentrations and control brain water and electrolyte balance, thereby producing an extracellular milieu in brain parenchyma that provides an optimal medium for neuronal and glial function. Specifically, intracerebral concentrations of K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ as well as CNS pH are tightly controlled by the brain microvascular endothelium (45, 59, 104). Additionally, the BBB protects brain parenchyma from fluctuations in ionic composition that can occur following a meal or exercise. In the absence of a functional BBB, such ionic shifts could lead to profound disturbances in neuronal and glial signaling. The BBB separates pools of neurotransmitters and neuroactive agents between central (i.e., brain) and peripheral (i.e., blood) compartments so that these two systems can function without “cross talk.” Because of its large surface area (i.e., ~20 m2 per 1.3 kg brain) and the short diffusion distance between neurons and capillaries, the BBB has the predominant role in regulating the brain microenvironment (2). This critical role of the BBB requires the microvascular endothelium to function as a “brain guard.” Such essential physiological functions have required brain microvascular endothelial cells to have evolved distinct molecular characteristics that enable them to protect CNS tissue from potentially toxic endogenous and exogenous substances that may be present in the blood.

ENDOTHELIAL CELLS AND THE BBB

Physiological functioning of the CNS requires precise regulation of the extracellular space in the brain parenchyma. Additionally, metabolic demands of cerebral tissue account for approximately 20% of total oxygen consumption in the body (35). Therefore, the interface between CNS and systemic circulation must possess mechanisms that can facilitate nutrient transport, exactly regulate ion balance, and provide a barrier to potential toxins. This emphasizes a critical need for both physical and biochemical mechanisms that contribute to BBB barrier properties.

Anatomically, BBB endothelial cells are characterized by a lack of fenestrations, minimal pinocytotic activity, and presence of tight junctions (1). Cerebral endothelial cells also have increased mitochondrial content, which enables the generation of biological energy that is required to drive transport of solutes into and out of the brain (108). Several receptors, ion channels, and influx/efflux transport proteins are expressed in brain microvascular endothelial cells. Transporters are a critical biochemical mechanism that are prominently involved in permitting brain entry of some substances while restricting blood-to-brain flux of others across the microvascular endothelium (134).

MOLECULAR CHARACTERISTICS OF THE BBB: TIGHT JUNCTION PROTEIN COMPLEXES

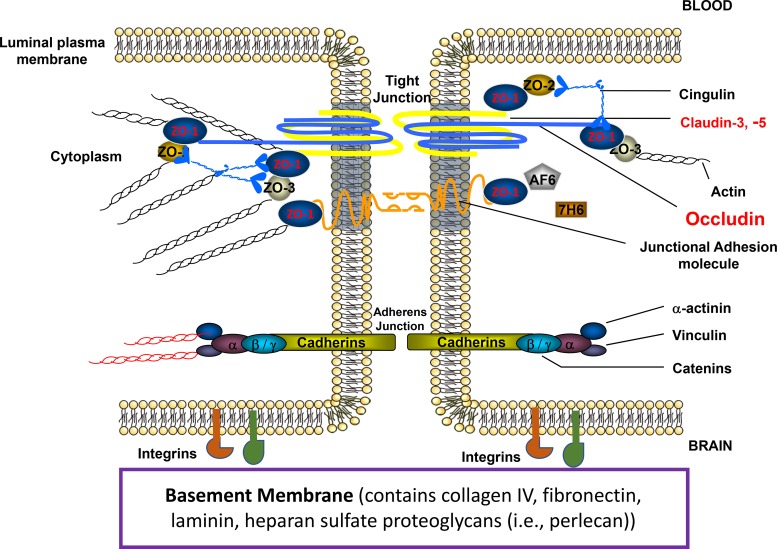

BBB endothelial cells are interconnected by tight junctions (Fig. 1), which are large, multiprotein complexes maintained by direct contact with astrocytes (58). Physiologically, tight junctions regulate movement of solutes between adjacent endothelial cells (i.e., paracellular diffusion) via formation of a continuous and impermeable barrier. As such, tight junctions ensure that the BBB restricts free flow of water and solutes, a property that is quantified by a high transendothelial resistance (i.e., 1,500–2,000 Ω·cm2) (21). BBB tight junction formation primarily involves specific transmembrane proteins [i.e., claudins, tricellulin, occludin, junctional adhesion molecules (JAMs)] that are linked to cytoskeletal filaments by interactions with accessory proteins [i.e., zonula occludens (ZO) proteins] (129).

Fig. 1.

Molecular organization of tight junction protein complexes at the mammalian blood-brain barrier. Following onset of ischemic stroke, tight junction protein complexes are disrupted, which leads to breakdown of the blood-brain barrier (BBB). BBB disruption is further exacerbated by degradations of integrins, which are also expressed at the plasma membrane of brain microvascular endothelial cells. ZO-1, zonula occludens-1. [Adapted from Ronaldson and Davis (127) with permission from Bentham Science.]

Several lines of evidence indicate that transmembrane tight junction proteins are critical for maintenance of functional BBB integrity. Claudins are 20- to 24-kDa proteins that contribute to the physiological “seal” of the tight junction (31, 46). Claudin-5 is the predominant claudin isoform that limits paracellular diffusion of small molecules (46). Barrier function can also be influenced by claudin-1, claudin-3, and claudin-12 (31, 46). Tricellulin is believed to play a role in limiting blood-to-brain movement of large molecules via the paracellular route (46, 120); however, its role in regulating BBB integrity in the setting of cerebral ischemia has not been studied. Occludin is a critical transmembrane regulator of BBB functional integrity in vivo (85, 93, 130). Occludin assembles into dimers and higher-order oligomers, a characteristic that is required for control of paracellular permeability. JAM isoforms regulate paracellular permeability at the BBB, particularly with respect to immune cells (i.e., neutrophils, monocytes/macrophages) (138, 155). Loss of JAM protein expression and/or migration of JAM proteins away from the tight junction directly leads to loss of BBB properties at the microvascular endothelium (43, 153).

Proper physiological functioning of the BBB, particularly restriction of paracellular solute transport, requires association of transmembrane tight junction proteins with cytoplasmic accessory proteins. In brain microvascular endothelial cells, membrane-associated guanylate kinase-like (MAGUK) proteins are involved in clustering of tight junction protein complexes to the cell membrane (42). Three MAGUK proteins have been identified at the tight junction: ZO-1, -2, and -3. ZO-1 links transmembrane tight junction proteins to the actin cytoskeleton (34). Previous studies have shown that dissociation of ZO-1 from the junction complex is associated with increased permeability, indicating that the ZO-1-transmembrane protein interaction is critical to tight junction stability and function (3, 37, 91). Similar to ZO-1, ZO-2 binds tight junction constituents as well as signaling molecules and transcription factors (15). ZO-3 has also been detected in brain microvascular endothelial cells; however, its precise role in maintenance of BBB properties has not been elucidated (144).

MOLECULAR CHARACTERISTICS OF THE BBB: ADHERENS JUNCTIONS

Adherens junctions are specialized cell-cell interactions that are formed by cadherins and associated proteins that are directly linked to actin filaments (119). Cadherins regulate endothelial function by activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling, an intracellular pathway that organizes the cytoskeleton and enables complex formation with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor 2. Therefore, cadherin-mediated signaling is essential for endothelial layer integrity and for the spatial organization of new microvessels (73). Barrier-forming endothelium has been shown to express higher levels of cadherin-10 relative to VE-cadherin (156). In contrast, circumventricular organs and choroid plexus capillaries (i.e., brain microvasculature that is devoid of BBB properties) primarily express VE-cadherin (156). Optimal cadherin function requires direct association with catenins. At least four catenin isoforms (i.e., β, α, Χ, and p120) are expressed at the BBB, with β-catenin linking cadherin to α-catenin, which binds this protein complex to the actin cytoskeleton (95). In vitro studies by Steiner and colleagues (143) demonstrated that the heparin sulfate proteoglycan agrin contributes to barrier properties of adherens junctions by promoting localization of VE-cadherin and β-catenin to endothelial cell junctions. Paracellular expression of VE-cadherin and/or β-catenin is associated with BBB repair following focal astrocyte loss in vivo (157).

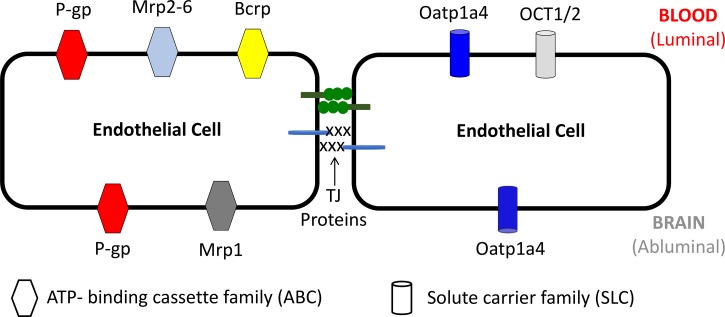

MOLECULAR CHARACTERISTICS OF THE BBB: TRANSPORTERS

Proteins expressed at the BBB are central determinants of the ability of endogenous and exogenous substances to permeate biological membranes. Such transport processes include ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters and solute carrier (SLC) transporters (134). BBB localization of those ABC and SLC transport proteins that are critical determinants of CNS permeation of drugs relevant to ischemic stroke treatment are depicted in Fig. 2. ABC transporters require biological energy via hydrolysis of ATP to transport xenobiotics and their metabolites against their concentration gradient. ABC transporters that are expressed at the brain microvascular endothelium include P-glycoprotein (P-gp), multidrug resistance proteins (Mrps), and breast cancer resistance protein (Bcrp). P-gp transports a vast array of structurally diverse compounds from different chemical classes, whereas Mrps are primarily involved in cellular efflux of anionic drugs as well as their glucuronidated, sulfated, and glutathione-conjugated metabolites (27, 96, 131, 134). Bcrp has significant overlap in substrate specificity profile with P-gp and has been shown to recognize a vast array of sulfo-conjugated organic anions, hydrophobic, and amphiphilic compounds (124). In fact, Bcrp has been shown to function in a synergistic manner with P-gp to limit brain permeation of drugs (5, 17, 29, 107, 114, 136).

Fig. 2.

Localization of ATP-binding cassette and solute carrier transporters at the blood-brain barrier. Bcrp, breast cancer resistance protein; Mrp, multidrug resistance protein; Oatp, organic anion transporting polypeptide; OCT, organic cation transporter; P-gp, P-glycoprotein.

In contrast to ABC transporters, membrane transport of circulating solutes by SLC family members is governed by either an electrochemical gradient utilizing an inorganic or organic solute as a driving force or the transmembrane concentration gradient of the substance actually being transported. SLC transporters that can facilitate blood-to-brain delivery of therapeutics relevant to treatment of ischemic stroke include organic anion transporting polypeptides (Oatps) and organic cation transporters (Octs). Oatps have distinct substrate preferences for amphipathic solutes (44, 128). For example, Oatps are well known to transport 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors (i.e., statins), which have been shown to exhibit neuroprotective and antioxidant properties (12, 146, 162). The primary Oatp isoform that is involved in blood-to-brain drug transport at the human BBB is OATP1A2 (39). In vitro studies in human and rat brain microvessel endothelial cells have shown expression of OCT1 and OCT2, with localization primarily at the luminal plasma membrane (81). An established transport substrate for OCT1/OCT2 is 1-amino-3,5-dimethyladamantane (i.e., memantine), a clinically approved NMDA receptor antagonist that is sometimes included in treatment regimens for ischemic stroke (94). The exact mechanism of memantine transport across the BBB requires more detailed investigation; however, therapeutic targeting of memantine to the CNS via OCT-dependent drug delivery may prove to be an effective mechanism to enhance the utility of this neuroprotective drug in ischemic stroke therapy.

DISRUPTION OF BBB INTEGRITY IN THE SETTING OF ISCHEMIC STROKE

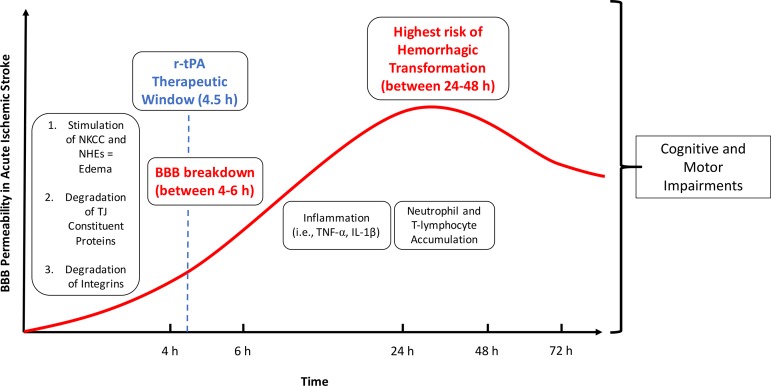

One of the hallmarks of ischemic stroke pathology is breakdown of the BBB, which is characterized by alterations of tight junction protein complexes (causing increased paracellular solute leak), modulation of transport proteins and endocytotic transport mechanisms (leading to changes in transcellular transport for some substances), and inflammatory damage, processes that trigger cognitive and motor impairment (Fig. 3). Such barrier breakdown leads to a significant increase in paracellular permeability at the level of the cerebral microvasculature, a remarkable pathological feature of stroke (68, 115). It is critical to note that BBB breakdown is a precursor to serious clinical consequences of ischemic stroke such as hemorrhagic transformation (64). One of the most significant contributors to BBB breakdown in stroke is activation of proteinases such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (172). This includes MMPs that are activated by hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α)-dependent mechanisms (i.e., MMP-2) and MMPs whose activation is triggered by cytokines (i.e., TNF-α, IL-1β) such as MMP-3 and MMP-9 (165). Involvement of MMPs in BBB disruption following ischemic stroke has been reported in experimental stroke models (13, 71, 171). Furthermore, elevation of MMP-9 has been reported in stroke patients (18). MMPs, in particular MMP-2 and MMP-9, directly compromise the BBB by degrading tight junction constituent proteins (83, 117, 121, 164, 165). The role of MMPs in BBB breakdown is highlighted by the observation that inhibition of MMP isoforms prevents BBB disruption following ischemic injury (25, 147, 166). Integrins, transmembrane glycoprotein receptors for the extracellular matrix, also play a significant role in BBB breakdown (165). Physiologically, integrins interact with constituents of the basement membrane (i.e., collagen IV, fibronectin, laminin, heparin sulfate proteoglycans such as perlecan) to regulate BBB permeability and transport (90, 165). In ischemic stroke, integrins are rapidly degraded, which leads to BBB breakdown and subsequent edema, inflammation, and exacerbation of stroke injury (165). Further evidence for the critical role of integrins in stroke pathogenesis comes from a recent study by Roberts and colleagues (123) who showed that mice lacking α5 integrin are resistant to cerebral infarction following focal cerebral ischemia. Overall, damage and subsequent opening of the BBB is a key event in development of the distinct processes of intracerebral hemorrhage and brain edema that follow onset of ischemic stroke.

Fig. 3.

Mechanisms of blood-brain barrier dysfunction in the setting of ischemic stroke. Early events involved in BBB breakdown following ischemic stroke include stimulation of sodium transporters (i.e., NKCC, NHE), which lead to edema, and degradation of tight junction constituent proteins and integrins, which cause increased paracellular leak at the BBB. BBB breakdown becomes apparent 4–6 h after stroke onset. Later events that contribute to continued barrier disruption include inflammation and accumulation of immune cells (i.e., neutrophils, T-lymphocytes) in brain parenchyma. Overall, BBB breakdown in the setting of ischemic stroke contributes to development of cognitive and motor symptoms. BBB, blood-brain barrier; NHE, Na-H exchanger; NKCC, Na-K-Cl cotransporter; r-tPA, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator.

Disruption of tight junction protein complexes is a hallmark of BBB disruption in the setting of ischemic stroke. In models of experimental stroke, altered expression of claudin-5 is associated with significant increases in paracellular solute permeability (41, 83, 139, 153). Ischemia-induced changes in claudin-5 localization and/or expression may result from altered protein trafficking that is mediated by caveolin-1 (141). The essential role for caveolin-1 in the pathophysiology of BBB dysfunction is underscored by studies in caveolin-1 knockout mice where loss of this protein was shown to prevent tight junction protein loss (24, 62). Immunofluorescence staining of brain microvascular endothelial cells has demonstrated expression of the transmembrane protein tricellulin at points of cell-to-cell contact (57). Similarly, altered occludin expression is associated with BBB dysfunction in several pathologies including hypoxia/aglycemia (19), hypoxia-reoxygenation (H/R) stress (85, 158), and focal cerebral ischemia (38, 78, 82). Hypoxia, cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury, and focal cerebral ischemia are associated with reduced ZO-1 expression at the BBB (60, 74, 168, 171). VE-cadherin expression was also decreased at the BBB in mice subjected to focal cerebral ischemia, suggesting that adherens junction disruption contributes to BBB dysfunction in the context of stroke (149, 154). More recently, studies in a rodent model of experimental ischemic stroke demonstrated activation of the VE-cadherin promoter and increased VE-cadherin protein expression at the BBB following focal cerebral ischemia, suggesting that adherens junction formation may be a primary mechanism in the poststroke reconstruction of the BBB (101).

Studies in in vivo models of experimental stroke have provided considerable information on solute leak across the BBB. Using the transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model, Pfefferkorn and Rosenberg (112) demonstrated enhanced leak of sucrose, a vascular marker that does not typically cross the BBB, in the ischemic hemisphere as compared with the contralateral hemisphere. BBB disruption in the setting of ischemic stroke is profound and involves blood-to-brain flux of large-molecular-weight solutes in addition to small-molecule xenobiotics. In fact, it is well known that BBB disruption such as that observed in experimental models of focal cerebral ischemia is sufficient to allow accumulation of Evan’s blue dye in the ischemic hemisphere (60). Evan’s blue dye, when unconjugated to plasma proteins, is a moderately sized molecule with a molecular mass of 960.8 Da. It is well established that Evan’s blue dye irreversibly binds to albumin in vivo. This leads to formation of a large complex with a molecular mass in excess of 60,000 Da. Indeed, a solute with such a large molecular mass can only permeate the BBB under considerable pathological stress such as that observed in the setting of ischemic stroke (100). For example, Li and colleagues (77) observed increased leakage of Evan’s blue-albumin into ischemic brain tissue 6 hours following reperfusion in an in vivo model of focal cerebral ischemia. Such dramatic changes in BBB permeability following MCAO is likely due to endothelial redistribution of tight junction proteins (60). Reorganization of tight junction proteins following focal cerebral ischemia is also mediated by VEGF (167) and nitric oxide (NO) (163).

BBB dysfunction and subsequent leak across the BBB following ischemic stroke enables considerable movement of vascular fluid across the microvascular endothelium and development of vasogenic edema (135). Recent studies using the MCAO model have shown that water movement across the BBB is exacerbated by enhanced brain accumulation of sodium ions. Increased flux of Na+ and Cl−, and subsequent flux of osmotically obliged water, across the BBB results from enhanced expression and activity of NKCC (150) and NHE1 and/or NHE2 (72). MCAO studies in spontaneously hypertensive rats demonstrate that the NHE1 transporter is a critical regulator of ischemia-induced infarct volume (51). More recently, treatment with a small-molecule inhibitor of the BBB calcium-activated potassium channel KCa3.1 (i.e., TRAM-34) showed reduced sodium uptake and cytotoxic edema following MCAO, suggesting a role for KCa3.1 in the development of edema in focal cerebral ischemia (22). Increased transendothelial flux of sodium across the BBB during ischemic stroke can also involve upregulation of sodium-dependent glucose transporters (SGLTs). Specifically, blockade of SGLT1 in MCAO rats significantly reduced infarct and edema ratios, suggesting that this critical transporter may be a key determinant of stroke outcome (148).

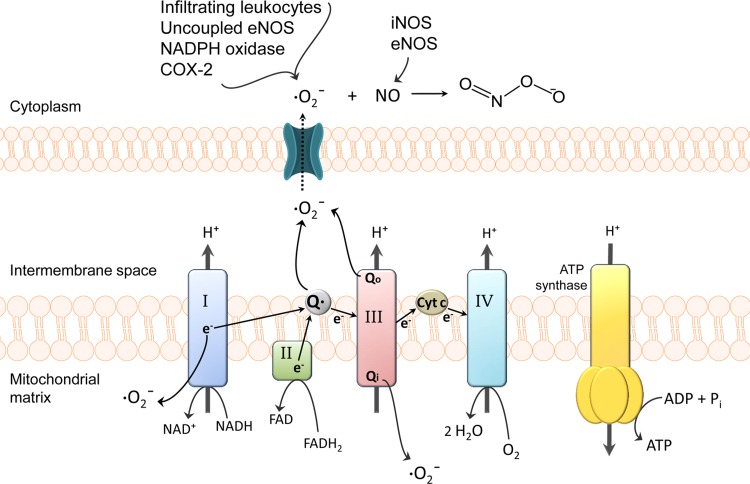

Functional BBB integrity is disrupted by production of ROS and subsequent oxidative stress (Fig. 4). Production of superoxide anion, a potent ROS generated when molecular oxygen is reduced by only one electron, is a known mediator of cellular damage following stroke (49, 70). Superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzymes tightly control biological activity of superoxide anion, a by-product of physiological processes. Under oxidative stress conditions, superoxide is produced at high levels that overwhelm the metabolic capacity of SOD. This phenomenon is supported by the observation that infarct size and cerebral edema were markedly reduced in mice engineered to overexpress SOD (70). Increased levels of superoxide can contribute to BBB dysfunction (86, 105). BBB injury can be intensified by conjugation of superoxide and NO to form peroxynitrite, a cytotoxic and proinflammatory molecule. Peroxynitrite causes damage to cerebral microvessels through lipid peroxidation, consumption of endogenous antioxidants [i.e., glutathione (GSH)], and induction of mitochondrial failure (109, 145). Peroxynitrite is known to induce endothelial damage by its ability to nitrosylate tyrosine, leading to functional modifications of critical proteins (133). Peroxynitrite formation at the BBB becomes more likely with activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) because NO rapidly diffuses through membranes and reacts with superoxide anion (109).

Fig. 4.

Generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cerebrovascular endothelial cells. During ischemia, mitochondrial superoxide levels increase via nitric oxide (NO) inhibition of cytochrome complexes and oxidation of reducing equivalents in the electron transport chain (ETC). Complex I as well as both sides of complex III (i.e., Qi and Qo sites) are the most common sources of mitochondrial superoxide. Superoxide generated within the intermembrane space of mitochondria can reach the cytosol through voltage-dependent mitochondrial anion channels (169). Superoxide levels further increase via cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), NADPH oxidase, uncoupled endothelial NO synthase (eNOS), and infiltrating leukocytes. The resulting high levels of superoxide, coupled with the activation of NO-producing eNOS/inducible NOS (iNOS), increases the likelihood of peroxynitrite formation. Peroxynitrite-induced cellular damage includes protein oxidation, tyrosine nitration, DNA damage, and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) activation, lipid peroxidation, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Cyt c, cytochrome c. [Adapted from Thompson and Ronaldson (145) with permission from Elsevier.]

Inflammatory stimuli are critical mediators of BBB disruption in the setting of stroke. Previous research has demonstrated that inflammatory mechanisms in focal cerebral ischemia are mediated through proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β, which are produced within 2–6 hours following an ischemic insult (151). Proinflammatory signaling induces adhesion molecules and subsequent transmigration of activated neutrophils, lymphocytes, or monocytes into brain parenchyma (40, 61, 111). In particular, neutrophil infiltration plays a critical role in enhancing BBB permeability and worsening stroke outcomes. This is emphasized by studies showing that inhibition of adhesion molecules or neutrophil integrin proteins protects against BBB disruption by reducing the numbers of neutrophils that are recruited to the brain in the setting of ischemic injury (23, 53). In contrast, enhanced migration of regulatory T cells across the BBB may have protective effects. It has been previously shown that regulatory T cells may inactivate MMP-9, thereby attempting to limit BBB leak (75, 76). Despite these novel observations, the role of regulatory T cells on BBB integrity in ischemic stroke remains unclear (80). Physiologically, expression of adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 are expressed at low levels at the BBB; however, their expression is significantly increased in response to stroke (111, 142). Proinflammatory mediators also modulate endogenous BBB transporters and tight junction proteins. For example, TNF-α increased expression of P-gp but decreased expression of Bcrp in a human brain endothelial cell line (i.e., hCMEC/d3 cells) (113). Additionally, TNF-α and IL-1β have been observed to decrease expression of occludin and ZO-1 (6, 125). Altered expression of occludin and ZO-1 in the setting of stroke may be associated with enhanced tyrosine and/or threonine phosphorylation that is triggered by enhanced production and secretion of inflammatory mediators in the ischemic brain (63, 125, 144). Interestingly, phosphorylation of occludin in the setting of H/R stress, a component of ischemic stroke, is mediated by increased activation of protein kinase C isoforms (158). Modulation of other posttranslational modifications to tight junction proteins (i.e., methylation, glycosylation) in the ischemic brain may be an additional factor associated with BBB dysfunction in the setting of stroke (140).

THERAPEUTIC APPROACHES FOR BBB PROTECTION IN ISCHEMIC STROKE

Targeting the Tight Junction

The BBB is clearly compromised in response to ischemic stroke. A critical “component” of stroke is cerebral hypoxia and subsequent brain injury resulting from reoxygenation/reperfusion (i.e., H/R stress). Over the past many years, BBB changes associated with H/R stress have been studied using an in vivo rodent model (56, 85, 93, 146, 158–160). Changes in BBB integrity due to tight junction disruption under H/R conditions were evidenced by enhanced brain accumulation of [14C]sucrose (85, 93, 158, 159). Additionally, H/R stress increased BBB leak to dextrans (molecular mass ranging between 4 kDa and 10 kDa) in hippocampal and cortical microvessels, suggesting enhanced paracellular permeability to small and large solutes (158). These alterations in vascular permeability in animals subjected to H/R stress were directly associated with an increase in the expression of HIF-1α and NF-κB in nuclear extracts isolated from intact microvessels (160). Changes in brain xenobiotic uptake are not likely attributed to modifications in cerebral blood flow because blood flow changes are negligible in the in vivo H/R model (159). Changes in [14C]sucrose and dextran accumulation in brain tissue were correlated with modified organization and/or expression of constituent tight junction proteins including occludin, claudin-5, and ZO-1 (85, 159, 161). Of particular significance was the observation that H/R stress disrupted disulfide-bonded occludin oligomeric assemblies, thereby preventing monomeric occludin from forming a physical barrier to paracellular diffusion (93). These changes in tight junction organization and BBB solute leak also correlated with a significant increase in brain water content following H/R, providing further evidence that disruption of the BBB under a “component” of cerebral ischemia contributes to vasogenic edema (161).

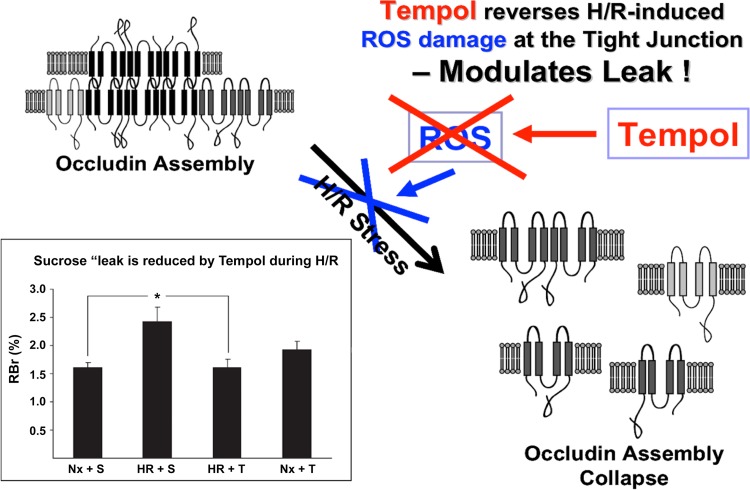

Production of ROS has been shown to modulate BBB expression of claudin-5 and occludin thereby increasing paracellular solute leak (137). Therefore, there is potential that BBB disruption in diseases with an oxidative stress component (i.e., ischemic stroke) could be attenuated via the use of an antioxidant drug. One such therapeutic is 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxyl (TEMPOL), a stable and membrane-permeable antioxidant. TEMPOL shows SOD-like activity towards the superoxide anion as well as reactivity with hydroxyl radicals, nitrogen dioxide, and the carbonate radical. TEMPOL readily crosses the BBB and has been previously shown to provide neuroprotection as a free radical scavenger in several models of brain injury and ischemia (26, 118). With respect to the BBB, administration of TEMPOL prior to H/R greatly attenuated CNS uptake of [14C]sucrose (85). Furthermore, TEMPOL preserved occludin localization at the tight junction and prevented collapse of occludin oligomeric assemblies in animals subjected to H/R stress, suggesting that this antioxidant drug can confer vascular protection (Fig. 5) (85). Restoration of BBB integrity coincided with a decrease in nuclear translocation of HIF-1α and a decrease in endothelial expression of the stress biomarker heat shock protein 70 (hsp70) in rats subjected to H/R and administered TEMPOL (85). Taken together, these observations provide evidence that the tight junction can be targeted pharmacologically during ischemic stroke for the purpose of reducing oxidative stress-associated injury and blood-to-brain solute leak.

Fig. 5.

Effect of TEMPOL on hypoxia-reoxygenation (H/R)-mediated disruption of the tight junction. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and subsequent oxidative stress are known to disrupt assembly of critical tight junction proteins such as occludin. Previous data show that administration of TEMPOL, a ROS scavenger, prevents disruption of occludin oligomers. Furthermore, TEMPOL attenuates the increase in sucrose leak across the blood-brain barrier observed in animals subjected to H/R stress. These observations demonstrate that the tight junction can be targeted pharmacologically in an effort to confer vascular protection during ischemic stroke. Nx, normoxia; S, sucrose; T, TEMPOL. [Adapted from Ronaldson and Davis (127) with permission from Bentham Science.]

Targeting Endogenous BBB Transporters

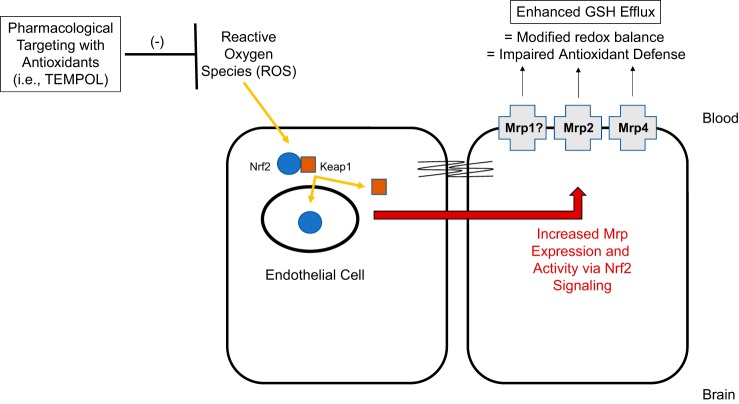

BBB transporters mediate the flux of endogenous substrates, many of which are essential to the cellular response to pathophysiological stressors. One such substance is the endogenous antioxidant GSH. During oxidative stress, GSH is oxidized to glutathione disulfide (GSSG). Therefore, the redox state of a cell is represented by the ratio of GSH to GSSG. In vitro studies using human and rodent brain microvascular endothelial cells have demonstrated that hypoxia reduces cellular GSH levels and decreases the GSH:GSSG ratio, suggesting the presence of oxidative stress (99, 102). Using an in vivo animal model, oxidative stress was shown to modify expression and/or assembly of occludin, claudin-5, and ZO-1, an effect that caused BBB disruption (19, 85, 91, 93, 158, 159). BBB leak that is associated with alterations in tight junction proteins can result in blood-to-brain flux of neurotoxic substances and/or contribute to vasogenic edema. Therefore, BBB protection and/or repair in stroke is paramount to protecting the brain from neurological damage. One approach that can accomplish this therapeutic objective is to prevent cellular loss of GSH from endothelial cells by targeting transporters that facilitate efflux of GSH into the blood (20). BBB transporters that can transport GSH, as well as GSSG, include Mrp1, Mrp2, and Mrp4 (50, 56, 110, 122). It is well known that increased cellular concentrations of GSH are cytoprotective while processes that promote GSH loss are injurious to cells (11). Therefore, it stands to reason that pharmacological targeting of Mrps during oxidative stress may have considerable therapeutic benefits including BBB protection. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that inhibition of Mrp-mediated transport using the established inhibitor MK571 prevented GSH efflux transport in primary cultures of astrocytes (11, 126).

Adding to the complexity of therapeutic targeting of Mrps to confer vascular protection in stroke is the knowledge that Mrp functional expression can change in response to oxidative stress (89, 126). Altered BBB expression of Mrps may prevent endothelial cells from retaining effective GSH concentrations. A thorough understanding of signaling pathways involved in Mrp regulation during oxidative stress will enable development of pharmacological approaches to target Mrp-mediated efflux (i.e., GSH transport) for the purpose of preventing BBB disruption in ischemic stroke. One intriguing signaling pathway is the nuclear factor E2-related factor-2 (Nrf2) pathway that is well known to be activated in response to oxidative stress. In the presence of ROS, the cytosolic Nrf2 repressor Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) undergoes structural alterations that cause dissociation from the Nrf2-Keap1 complex. This enables Nrf2 to translocate to the nucleus and induce transcription of genes that possess an antioxidant response element at their promoter (7, 48, 88). It has been shown that Nrf2 activation induces expression of Mrp1, Mrp2, and Mrp4 (7, 48, 56, 89, 152). An emerging concept is that Nrf2 acts as a “double-edged sword”: it can provide tissue protection while, at the same time, cause deleterious effects in a cell (88). Therefore, an alteration in the balance of Mrp isoforms via activation of Nrf2 signaling may adversely affect redox balance and antioxidant defense at the BBB. Indeed, this points towards a need for rigorous study of pharmacological strategies that can modulate Nrf2 signaling and control expression of Mrp isoforms and/or GSH transport at the brain microvascular endothelium (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Prevention of blood-brain barrier (BBB) dysfunction by targeting multidrug resistance protein (Mrp) isoforms in brain microvessel endothelial cells. Our laboratory has reported that expression of Mrp1, Mrp2, and Mrp4 are increased at the BBB in the setting of hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) stress. H/R stress is known to decrease glutathione (GSH) levels and increase glutathione disulfide (GSSG) concentrations in brain microvascular endothelial cells. We postulate that changes in GSH/GSSG transport occur during H/R as a result of altered functional expression of at least one Mrp isoform. Since nuclear factor E2-related factor-2 (Nrf2), a ROS sensitive transcription factor, is known to regulate Mrps, we propose that this signaling pathway is a central mechanism for regulation of Mrps at the BBB. Antioxidant drugs can be used as pharmacological tools to understand how targeting activation of the Nrf2 pathway can control Mrp expression and/or activity.

SUMMARY AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

The field of BBB physiology, particularly the study of tight junction protein complexes and transport systems, has rapidly advanced over the past quarter century. It is now established that tight junction protein complexes are dynamic in nature and can organize and reorganize in response to ischemic stroke. These changes in tight junctions can lead to increased BBB permeability to small-molecule drugs via paracellular diffusion. Additionally, endogenous BBB transporters (i.e., Mrps) represent viable molecular targets for BBB protection in the setting of ischemic stroke. Molecular machinery involved in regulation of these endogenous transport systems (i.e., Nrf2 signaling) is just now becoming fully characterized. These crucial discoveries have identified multiple targets that can be exploited for protection against BBB dysfunction. Perhaps targeting of currently marketed or novel drugs to efflux transporters such as Mrp1, Mrp2, and Mrp4 will lead to significant advancements in ischemic stroke treatment. However, stroke possesses a complicated pathophysiology that is further challenged by the existence of comorbid conditions. Factors such as chronical age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, and hyperlipidemia are likely to affect the therapeutic effectiveness of pharmacological strategies aimed at conferring BBB protection in the setting of stroke. For example, stroke is a neurological and vascular disease that is considerably more prevalent in aged individuals (14). Quantitative MRI studies have demonstrated that BBB breakdown is more extensive in aged Wistar rats as compared with their young counterparts following experimental stroke (65). Studies in stroke-prone hypertensive rats demonstrated that elevated blood pressure resulted in reduced expression of ZO-1 and occludin and increased numbers of white matter lesions (33). Additionally, hypertension is associated with increased expression of ICAM-1 as the brain microvascular endothelium, a finding that is associated with a greater degree of cognitive impairment following stroke (97). Similarly, there is considerable evidence that mild and severe hyperglycemia/diabetes mellitus type II causes BBB dysfunction and can lead to cerebrovascular disorders (32, 66, 67). Diabetes mellitus type II contributes to BBB breakdown, brain infarction, edema formation, memory deficits, hemorrhagic transformation, and vascular disturbances following ischemic injury (10, 52, 92, 170). Clearly, improved translation of preclinical studies aimed at developing novel strategies to confer BBB protection in the setting of ischemic stroke must consider biological variables and comorbid conditions in the experimental design. This knowledge is critical to inform future work aimed at studying the interplay of tight junction protein complexes, transporters, and intracellular signaling pathways at the BBB and how these systems can be effectively targeted for improved stroke treatment and health outcomes.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01-NS084941 and Arizona Biomedical Research Commission Grant ADHS16-162406 to P. T. Ronaldson.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

W.A. and P.T.R. prepared figures; W.A., D.T., and P.T.R. drafted manuscript; W.A. and P.T.R. edited and revised manuscript; P.T.R. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbott NJ. Blood-brain barrier structure and function and the challenges for CNS drug delivery. J Inherit Metab Dis 36: 437–449, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s10545-013-9608-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbott NJ, Rönnbäck L, Hansson E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat Rev Neurosci 7: 41–53, 2006. doi: 10.1038/nrn1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abbruscato TJ, Lopez SP, Mark KS, Hawkins BT, Davis TP. Nicotine and cotinine modulate cerebral microvascular permeability and protein expression of ZO-1 through nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed on brain endothelial cells. J Pharm Sci 91: 2525–2538, 2002. doi: 10.1002/jps.10256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adibhatla RM, Hatcher JF. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and matrix metalloproteinases in the pathogenesis of stroke: therapeutic strategies. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 7: 243–253, 2008. doi: 10.2174/187152708784936608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agarwal S, Elmquist WF. Insight into the cooperation of P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) and breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) at the blood-brain barrier: a case study examining sorafenib efflux clearance. Mol Pharm 9: 678–684, 2012. doi: 10.1021/mp200465c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahishali B, Kaya M, Kalayci R, Uzun H, Bilgic B, Arican N, Elmas I, Aydin S, Kucuk M. Effects of lipopolysaccharide on the blood-brain barrier permeability in prolonged nitric oxide blockade-induced hypertensive rats. Int J Neurosci 115: 151–168, 2005. doi: 10.1080/00207450590519030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aleksunes LM, Slitt AL, Maher JM, Augustine LM, Goedken MJ, Chan JY, Cherrington NJ, Klaassen CD, Manautou JE. Induction of Mrp3 and Mrp4 transporters during acetaminophen hepatotoxicity is dependent on Nrf2. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 226: 74–83, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alluri H, Wiggins-Dohlvik K, Davis ML, Huang JH, Tharakan B. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction following traumatic brain injury. Metab Brain Dis 30: 1093–1104, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s11011-015-9651-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arai K, Lok J, Guo S, Hayakawa K, Xing C, Lo EH. Cellular mechanisms of neurovascular damage and repair after stroke. J Child Neurol 26: 1193–1198, 2011. doi: 10.1177/0883073811408610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Artola A. Diabetes-, stress- and ageing-related changes in synaptic plasticity in hippocampus and neocortex–the same metaplastic process? Eur J Pharmacol 585: 153–162, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ballatori N, Krance SM, Notenboom S, Shi S, Tieu K, Hammond CL. Glutathione dysregulation and the etiology and progression of human diseases. Biol Chem 390: 191–214, 2009. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barone E, Cenini G, Di Domenico F, Martin S, Sultana R, Mancuso C, Murphy MP, Head E, Butterfield DA. Long-term high-dose atorvastatin decreases brain oxidative and nitrosative stress in a preclinical model of Alzheimer disease: a novel mechanism of action. Pharmacol Res 63: 172–180, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bauer AT, Bürgers HF, Rabie T, Marti HH. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 mediates hypoxia-induced vascular leakage in the brain via tight junction rearrangement. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 30: 837–848, 2010. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Floyd J, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Mackey RH, Matsushita K, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Thiagarajan RR, Reeves MJ, Ritchey M, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sasson C, Towfighi A, Tsao CW, Turner MB, Virani SS, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 135: e146–e603, 2017. [Erratum in Circulation 135: e646, 2017.] doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Betanzos A, Huerta M, Lopez-Bayghen E, Azuara E, Amerena J, González-Mariscal L. The tight junction protein ZO-2 associates with Jun, Fos and C/EBP transcription factors in epithelial cells. Exp Cell Res 292: 51–66, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blanchette M, Daneman R. Formation and maintenance of the BBB. Mech Dev 138: 8–16, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breedveld P, Beijnen JH, Schellens JH. Use of P-glycoprotein and BCRP inhibitors to improve oral bioavailability and CNS penetration of anticancer drugs. Trends Pharmacol Sci 27: 17–24, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brouns R, Wauters A, De Surgeloose D, Mariën P, De Deyn PP. Biochemical markers for blood-brain barrier dysfunction in acute ischemic stroke correlate with evolution and outcome. Eur Neurol 65: 23–31, 2011. doi: 10.1159/000321965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown RC, Davis TP. Hypoxia/aglycemia alters expression of occludin and actin in brain endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 327: 1114–1123, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brzica H, Abdullahi W, Ibbotson K, Ronaldson PT. Role of transporters in central nervous system drug delivery and blood-brain barrier protection: relevance to treatment of stroke. J Cent Nerv Syst Dis 9: 1179573517693802, 2017. doi: 10.1177/1179573517693802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butt AM, Jones HC, Abbott NJ. Electrical resistance across the blood-brain barrier in anaesthetized rats: a developmental study. J Physiol 429: 47–62, 1990. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen YJ, Wallace BK, Yuen N, Jenkins DP, Wulff H, O’Donnell ME. Blood-brain barrier KCa3.1 channels: evidence for a role in brain Na uptake and edema in ischemic stroke. Stroke 46: 237–244, 2015. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.007445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi EY, Santoso S, Chavakis T. Mechanisms of neutrophil transendothelial migration. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 14: 1596–1605, 2009. doi: 10.2741/3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi KH, Kim HS, Park MS, Kim JT, Kim JH, Cho KA, Lee MC, Lee HJ, Cho KH. Regulation of caveolin-1 expression determines early brain edema after experimental focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke 47: 1336–1343, 2016. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cui J, Chen S, Zhang C, Meng F, Wu W, Hu R, Hadass O, Lehmidi T, Blair GJ, Lee M, Chang M, Mobashery S, Sun GY, Gu Z. Inhibition of MMP-9 by a selective gelatinase inhibitor protects neurovasculature from embolic focal cerebral ischemia. Mol Neurodegener 7: 21, 2012. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-7-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cuzzocrea S, McDonald MC, Mazzon E, Filipe HM, Costantino G, Caputi AP, Thiemermann C. Beneficial effects of tempol, a membrane-permeable radical scavenger, in a rodent model of splanchnic artery occlusion and reperfusion. Shock 14: 150–156, 2000. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200014020-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dallas S, Miller DS, Bendayan R. Multidrug resistance-associated proteins: expression and function in the central nervous system. Pharmacol Rev 58: 140–161, 2006. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.2.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daneman R. The blood-brain barrier in health and disease. Ann Neurol 72: 648–672, 2012. doi: 10.1002/ana.23648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Vries NA, Zhao J, Kroon E, Buckle T, Beijnen JH, van Tellingen O. P-glycoprotein and breast cancer resistance protein: two dominant transporters working together in limiting the brain penetration of topotecan. Clin Cancer Res 13: 6440–6449, 2007. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DiNapoli VA, Huber JD, Houser K, Li X, Rosen CL. Early disruptions of the blood-brain barrier may contribute to exacerbated neuronal damage and prolonged functional recovery following stroke in aged rats. Neurobiol Aging 29: 753–764, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dithmer S, Staat C, Müller C, Ku MC, Pohlmann A, Niendorf T, Gehne N, Fallier-Becker P, Kittel Á, Walter FR, Veszelka S, Deli MA, Blasig R, Haseloff RF, Blasig IE, Winkler L. Claudin peptidomimetics modulate tissue barriers for enhanced drug delivery. Ann NY Acad Sci 1397: 169–184, 2017. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ennis SR, Keep RF. Effect of sustained-mild and transient-severe hyperglycemia on ischemia-induced blood-brain barrier opening. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 27: 1573–1582, 2007. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fan Y, Yang X, Tao Y, Lan L, Zheng L, Sun J. Tight junction disruption of blood-brain barrier in white matter lesions in chronic hypertensive rats. Neuroreport 26: 1039–1043, 2015. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fanning AS, Jameson BJ, Jesaitis LA, Anderson JM. The tight junction protein ZO-1 establishes a link between the transmembrane protein occludin and the actin cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem 273: 29745–29753, 1998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fantin A, Vieira JM, Gestri G, Denti L, Schwarz Q, Prykhozhij S, Peri F, Wilson SW, Ruhrberg C. Tissue macrophages act as cellular chaperones for vascular anastomosis downstream of VEGF-mediated endothelial tip cell induction. Blood 116: 829–840, 2010. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-257832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fellman V, Raivio KO. Reperfusion injury as the mechanism of brain damage after perinatal asphyxia. Pediatr Res 41: 599–606, 1997. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199705000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fischer S, Wobben M, Marti HH, Renz D, Schaper W. Hypoxia-induced hyperpermeability in brain microvessel endothelial cells involves VEGF-mediated changes in the expression of zonula occludens-1. Microvasc Res 63: 70–80, 2002. doi: 10.1006/mvre.2001.2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frankowski JC, DeMars KM, Ahmad AS, Hawkins KE, Yang C, Leclerc JL, Doré S, Candelario-Jalil E. Detrimental role of the EP1 prostanoid receptor in blood-brain barrier damage following experimental ischemic stroke. Sci Rep 5: 17956, 2015. doi: 10.1038/srep17956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao B, Hagenbuch B, Kullak-Ublick GA, Benke D, Aguzzi A, Meier PJ. Organic anion-transporting polypeptides mediate transport of opioid peptides across blood-brain barrier. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 294: 73–79, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gelderblom M, Leypoldt F, Steinbach K, Behrens D, Choe CU, Siler DA, Arumugam TV, Orthey E, Gerloff C, Tolosa E, Magnus T. Temporal and spatial dynamics of cerebral immune cell accumulation in stroke. Stroke 40: 1849–1857, 2009. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.534503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gibson CL, Srivastava K, Sprigg N, Bath PM, Bayraktutan U. Inhibition of Rho-kinase protects cerebral barrier from ischaemia-evoked injury through modulations of endothelial cell oxidative stress and tight junctions. J Neurochem 129: 816–826, 2014. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.González-Mariscal L, Betanzos A, Avila-Flores A. MAGUK proteins: structure and role in the tight junction. Semin Cell Dev Biol 11: 315–324, 2000. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haarmann A, Deiss A, Prochaska J, Foerch C, Weksler B, Romero I, Couraud PO, Stoll G, Rieckmann P, Buttmann M. Evaluation of soluble junctional adhesion molecule-A as a biomarker of human brain endothelial barrier breakdown. PLoS One 5: e13568, 2010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hagenbuch B, Meier PJ. Organic anion transporting polypeptides of the OATP/SLC21 family: phylogenetic classification as OATP/SLCO superfamily, new nomenclature and molecular/functional properties. Pflugers Arch 447: 653–665, 2004. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1168-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hansen AJ. Effect of anoxia on ion distribution in the brain. Physiol Rev 65: 101–148, 1985. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1985.65.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haseloff RF, Dithmer S, Winkler L, Wolburg H, Blasig IE. Transmembrane proteins of the tight junctions at the blood-brain barrier: structural and functional aspects. Semin Cell Dev Biol 38: 16–25, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hawkins BT, Davis TP. The blood-brain barrier/neurovascular unit in health and disease. Pharmacol Rev 57: 173–185, 2005. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.2.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hayashi A, Suzuki H, Itoh K, Yamamoto M, Sugiyama Y. Transcription factor Nrf2 is required for the constitutive and inducible expression of multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 in mouse embryo fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 310: 824–829, 2003. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heo JH, Han SW, Lee SK. Free radicals as triggers of brain edema formation after stroke. Free Radic Biol Med 39: 51–70, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hirrlinger J, Dringen R. Multidrug resistance protein 1-mediated export of glutathione and glutathione disulfide from brain astrocytes. Methods Enzymol 400: 395–409, 2005. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hom S, Fleegal MA, Egleton RD, Campos CR, Hawkins BT, Davis TP. Comparative changes in the blood-brain barrier and cerebral infarction of SHR and WKY rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R1881–R1892, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00761.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang J, Liu B, Yang C, Chen H, Eunice D, Yuan Z. Acute hyperglycemia worsens ischemic stroke-induced brain damage via high mobility group box-1 in rats. Brain Res 1535: 148–155, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang T, Gao D, Hei Y, Zhang X, Chen X, Fei Z. D-allose protects the blood brain barrier through PPARγ-mediated anti-inflammatory pathway in the mice model of ischemia reperfusion injury. Brain Res 1642: 478–486, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iadecola C. The neurovascular unit coming of age: a journey through neurovascular coupling in health and disease. Neuron 96: 17–42, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iadecola C, Alexander M. Cerebral ischemia and inflammation. Curr Opin Neurol 14: 89–94, 2001. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200102000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ibbotson K, Yell J, Ronaldson PT. Nrf2 signaling increases expression of ATP-binding cassette subfamily C mRNA transcripts at the blood-brain barrier following hypoxia-reoxygenation stress. Fluids Barriers CNS 14: 6, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s12987-017-0055-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Iwamoto N, Higashi T, Furuse M. Localization of angulin-1/LSR and tricellulin at tricellular contacts of brain and retinal endothelial cells in vivo. Cell Struct Funct 39: 1–8, 2014. doi: 10.1247/csf.13015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Janzer RC, Raff MC. Astrocytes induce blood-brain barrier properties in endothelial cells. Nature 325: 253–257, 1987. doi: 10.1038/325253a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jeong SM, Hahm KD, Shin JW, Leem JG, Lee C, Han SM. Changes in magnesium concentration in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid of neuropathic rats. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 50: 211–216, 2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.00925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jiao H, Wang Z, Liu Y, Wang P, Xue Y. Specific role of tight junction proteins claudin-5, occludin, and ZO-1 of the blood-brain barrier in a focal cerebral ischemic insult. J Mol Neurosci 44: 130–139, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s12031-011-9496-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jickling GC, Liu D, Ander BP, Stamova B, Zhan X, Sharp FR. Targeting neutrophils in ischemic stroke: translational insights from experimental studies. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 35: 888–901, 2015. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jin X, Sun Y, Xu J, Liu W. Caveolin-1 mediates tissue plasminogen activator-induced MMP-9 up-regulation in cultured brain microvascular endothelial cells. J Neurochem 132: 724–730, 2015. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kago T, Takagi N, Date I, Takenaga Y, Takagi K, Takeo S. Cerebral ischemia enhances tyrosine phosphorylation of occludin in brain capillaries. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 339: 1197–1203, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kassner A, Merali Z. Assessment of blood-brain barrier disruption in stroke. Stroke 46: 3310–3315, 2015. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kaur J, Tuor UI, Zhao Z, Barber PA. Quantitative MRI reveals the elderly ischemic brain is susceptible to increased early blood-brain barrier permeability following tissue plasminogen activator related to claudin 5 and occludin disassembly. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 31: 1874–1885, 2011. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kawai N, Stummer W, Ennis SR, Betz AL, Keep RF. Blood-brain barrier glutamine transport during normoglycemic and hyperglycemic focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 19: 79–86, 1999. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199901000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Keep RF, Andjelkovic AV, Stamatovic SM, Shakui P, Ennis SR. Ischemia-induced endothelial cell dysfunction. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 95: 399–402, 2005. doi: 10.1007/3-211-32318-X_81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Keep RF, Xiang J, Ennis SR, Andjelkovic A, Hua Y, Xi G, Hoff JT. Blood-brain barrier function in intracerebral hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 105: 73–77, 2008. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-09469-3_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kiedrowski L. NCX and NCKX operation in ischemic neurons. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1099: 383–395, 2007. doi: 10.1196/annals.1387.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim GW, Lewén A, Copin J, Watson BD, Chan PH. The cytosolic antioxidant, copper/zinc superoxide dismutase, attenuates blood-brain barrier disruption and oxidative cellular injury after photothrombotic cortical ischemia in mice. Neuroscience 105: 1007–1018, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00237-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kumari R, Willing LB, Patel SD, Baskerville KA, Simpson IA. Increased cerebral matrix metalloprotease-9 activity is associated with compromised recovery in the diabetic db/db mouse following a stroke. J Neurochem 119: 1029–1040, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07487.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lam TI, Wise PM, O’Donnell ME. Cerebral microvascular endothelial cell Na/H exchange: evidence for the presence of NHE1 and NHE2 isoforms and regulation by arginine vasopressin. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 297: C278–C289, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00093.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lampugnani MG, Dejana E. Adherens junctions in endothelial cells regulate vessel maintenance and angiogenesis. Thromb Res 120, Suppl 2: S1–S6, 2007. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(07)70124-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li H, Gao A, Feng D, Wang Y, Zhang L, Cui Y, Li B, Wang Z, Chen G. Evaluation of the protective potential of brain microvascular endothelial cell autophagy on blood-brain barrier integrity during experimental cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Transl Stroke Res 5: 618–626, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s12975-014-0354-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li P, Gan Y, Sun BL, Zhang F, Lu B, Gao Y, Liang W, Thomson AW, Chen J, Hu X. Adoptive regulatory T-cell therapy protects against cerebral ischemia. Ann Neurol 74: 458–471, 2013. doi: 10.1002/ana.23815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li P, Mao L, Liu X, Gan Y, Zheng J, Thomson AW, Gao Y, Chen J, Hu X. Essential role of program death 1-ligand 1 in regulatory T-cell-afforded protection against blood-brain barrier damage after stroke. Stroke 45: 857–864, 2014. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li Y, Xu L, Zeng K, Xu Z, Suo D, Peng L, Ren T, Sun Z, Yang W, Jin X, Yang L. Propane-2-sulfonic acid octadec-9-enyl-amide, a novel PPARα/γ dual agonist, protects against ischemia-induced brain damage in mice by inhibiting inflammatory responses. Brain Behav Immun 66: 289–301, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liang J, Qi Z, Liu W, Wang P, Shi W, Dong W, Ji X, Luo Y, Liu KJ. Normobaric hyperoxia slows blood-brain barrier damage and expands the therapeutic time window for tissue-type plasminogen activator treatment in cerebral ischemia. Stroke 46: 1344–1351, 2015. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.008599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liebner S, Dijkhuizen RM, Reiss Y, Plate KH, Agalliu D, Constantin G. Functional morphology of the blood-brain barrier in health and disease. Acta Neuropathol 135: 311–336, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s00401-018-1815-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liesz A, Kleinschnitz C. Regulatory T cells in post-stroke immune homeostasis. Transl Stroke Res 7: 313–321, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s12975-016-0465-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lin CJ, Tai Y, Huang MT, Tsai YF, Hsu HJ, Tzen KY, Liou HH. Cellular localization of the organic cation transporters, OCT1 and OCT2, in brain microvessel endothelial cells and its implication for MPTP transport across the blood-brain barrier and MPTP-induced dopaminergic toxicity in rodents. J Neurochem 114: 717–727, 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu C, Duan Z, Guan Y, Wu H, Hu K, Gao X, Yuan F, Jiang Z, Fan Y, He B, Wang S, Zhang Z. Increased expression of tight junction protein occludin is associated with the protective effect of mosapride against aspirin-induced gastric injury. Exp Ther Med 15: 1626–1632, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu J, Jin X, Liu KJ, Liu W. Matrix metalloproteinase-2-mediated occludin degradation and caveolin-1-mediated claudin-5 redistribution contribute to blood-brain barrier damage in early ischemic stroke stage. J Neurosci 32: 3044–3057, 2012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6409-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liu S, Levine SR, Winn HR. Targeting ischemic penumbra: part I– from pathophysiology to therapeutic strategy. J Exp Stroke Transl Med 3: 47–55, 2010. doi: 10.6030/1939-067X-3.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lochhead JJ, McCaffrey G, Quigley CE, Finch J, DeMarco KM, Nametz N, Davis TP. Oxidative stress increases blood-brain barrier permeability and induces alterations in occludin during hypoxia-reoxygenation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 30: 1625–1636, 2010. [Erratum in J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 31: 790–791, 2011.] doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lochhead JJ, McCaffrey G, Sanchez-Covarrubias L, Finch JD, Demarco KM, Quigley CE, Davis TP, Ronaldson PT. Tempol modulates changes in xenobiotic permeability and occludin oligomeric assemblies at the blood-brain barrier during inflammatory pain. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302: H582–H593, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00889.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Luo J, Wang Y, Chen H, Kintner DB, Cramer SW, Gerdts JK, Chen X, Shull GE, Philipson KD, Sun D. A concerted role of Na+-K+-Cl− cotransporter and Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in ischemic damage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 28: 737–746, 2008. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ma Q. Role of nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 53: 401–426, 2013. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011112-140320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Maher JM, Dieter MZ, Aleksunes LM, Slitt AL, Guo G, Tanaka Y, Scheffer GL, Chan JY, Manautou JE, Chen Y, Dalton TP, Yamamoto M, Klaassen CD. Oxidative and electrophilic stress induces multidrug resistance-associated protein transporters via the nuclear factor-E2-related factor-2 transcriptional pathway. Hepatology 46: 1597–1610, 2007. doi: 10.1002/hep.21831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Marcelo A, Bix G. The potential role of perlecan domain V as novel therapy in vascular dementia. Metab Brain Dis 30: 1–5, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s11011-014-9576-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mark KS, Davis TP. Cerebral microvascular changes in permeability and tight junctions induced by hypoxia-reoxygenation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H1485–H1494, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00645.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.McBride DW, Legrand J, Krafft PR, Flores J, Klebe D, Tang J, Zhang JH. Acute hyperglycemia is associated with immediate brain swelling and hemorrhagic transformation after middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 121: 237–241, 2016. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-18497-5_42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McCaffrey G, Willis CL, Staatz WD, Nametz N, Quigley CA, Hom S, Lochhead JJ, Davis TP. Occludin oligomeric assemblies at tight junctions of the blood-brain barrier are altered by hypoxia and reoxygenation stress. J Neurochem 110: 58–71, 2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06113.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mehta DC, Short JL, Nicolazzo JA. Memantine transport across the mouse blood-brain barrier is mediated by a cationic influx H+ antiporter. Mol Pharm 10: 4491–4498, 2013. doi: 10.1021/mp400316e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Meng W, Takeichi M. Adherens junction: molecular architecture and regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 1: a002899, 2009. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Miller DS, Bauer B, Hartz AM. Modulation of P-glycoprotein at the blood-brain barrier: opportunities to improve central nervous system pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol Rev 60: 196–209, 2008. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.07109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Möller K, Pösel C, Kranz A, Schulz I, Scheibe J, Didwischus N, Boltze J, Weise G, Wagner DC. Arterial hypertension aggravates innate immune responses after experimental stroke. Front Cell Neurosci 9: 461, 2015. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mracsko E, Veltkamp R. Neuroinflammation after intracerebral hemorrhage. Front Cell Neurosci 8: 388, 2014. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Muruganandam A, Smith C, Ball R, Herring T, Stanimirovic D. Glutathione homeostasis and leukotriene-induced permeability in human blood-brain barrier endothelial cells subjected to in vitro ischemia. Acta Neurochir Suppl 76: 29–34, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nagaraja TN, Keenan KA, Fenstermacher JD, Knight RA. Acute leakage patterns of fluorescent plasma flow markers after transient focal cerebral ischemia suggest large openings in blood-brain barrier. Microcirculation 15: 1–14, 2008. doi: 10.1080/10739680701409811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nakano-Doi A, Sakuma R, Matsuyama T, Nakagomi T. Ischemic stroke activates the VE-cadherin promoter and increases VE-cadherin expression in adult mice. Histol Histopathol 33: 507–521, 2018. doi: 10.14670/HH-11-952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Namba K, Takeda Y, Sunami K, Hirakawa M. Temporal profiles of the levels of endogenous antioxidants after four-vessel occlusion in rats. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 13: 131–137, 2001. doi: 10.1097/00008506-200104000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Neuwelt EA, Bauer B, Fahlke C, Fricker G, Iadecola C, Janigro D, Leybaert L, Molnár Z, O’Donnell ME, Povlishock JT, Saunders NR, Sharp F, Stanimirovic D, Watts RJ, Drewes LR. Engaging neuroscience to advance translational research in brain barrier biology. Nat Rev Neurosci 12: 169–182, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nrn2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nischwitz V, Berthele A, Michalke B. Speciation analysis of selected metals and determination of their total contents in paired serum and cerebrospinal fluid samples: an approach to investigate the permeability of the human blood-cerebrospinal fluid-barrier. Anal Chim Acta 627: 258–269, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2008.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nito C, Kamada H, Endo H, Niizuma K, Myer DJ, Chan PH. Role of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase/cytosolic phospholipase A2 signaling pathway in blood-brain barrier disruption after focal cerebral ischemia and reperfusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 28: 1686–1696, 2008. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.O’Donnell ME. Blood-brain barrier Na transporters in ischemic stroke. Adv Pharmacol 71: 113–146, 2014. doi: 10.1016/bs.apha.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Oberoi RK, Mittapalli RK, Elmquist WF. Pharmacokinetic assessment of efflux transport in sunitinib distribution to the brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 347: 755–764, 2013. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.208959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Oldendorf WH, Cornford ME, Brown WJ. The large apparent work capability of the blood-brain barrier: a study of the mitochondrial content of capillary endothelial cells in brain and other tissues of the rat. Ann Neurol 1: 409–417, 1977. doi: 10.1002/ana.410010502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pacher P, Beckman JS, Liaudet L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol Rev 87: 315–424, 2007. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Paulusma CC, van Geer MA, Evers R, Heijn M, Ottenhoff R, Borst P, Oude Elferink RP. Canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter/multidrug resistance protein 2 mediates low-affinity transport of reduced glutathione. Biochem J 338: 393–401, 1999. doi: 10.1042/bj3380393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Petty MA, Lo EH. Junctional complexes of the blood-brain barrier: permeability changes in neuroinflammation. Prog Neurobiol 68: 311–323, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0082(02)00128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pfefferkorn T, Rosenberg GA. Closure of the blood-brain barrier by matrix metalloproteinase inhibition reduces rtPA-mediated mortality in cerebral ischemia with delayed reperfusion. Stroke 34: 2025–2030, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000083051.93319.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Poller B, Drewe J, Krähenbühl S, Huwyler J, Gutmann H. Regulation of BCRP (ABCG2) and P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) by cytokines in a model of the human blood-brain barrier. Cell Mol Neurobiol 30: 63–70, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s10571-009-9431-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Polli JW, Olson KL, Chism JP, John-Williams LS, Yeager RL, Woodard SM, Otto V, Castellino S, Demby VE. An unexpected synergist role of P-glycoprotein and breast cancer resistance protein on the central nervous system penetration of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor lapatinib (N-3-chloro-4-[(3-fluorobenzyl)oxy]phenyl-6-[5-([2-(methylsulfonyl)ethyl]aminomethyl)-2-furyl]-4-quinazolinamine; GW572016). Drug Metab Dispos 37: 439–442, 2009. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.024646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Prakash R, Carmichael ST. Blood-brain barrier breakdown and neovascularization processes after stroke and traumatic brain injury. Curr Opin Neurol 28: 556–564, 2015. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Pundik S, Xu K, Sundararajan S. Reperfusion brain injury: focus on cellular bioenergetics. Neurology 79, Suppl 1: S44–S51, 2012. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182695a14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]