Introduction

There has been tremendous interest in the development of clean and environmentally benign methods for the transformation of biomass into platform chemicals and biofuels.1 Recent advancements in this field have enabled the conversion of an array of biomass-based materials into biofuel feedstocks.2 Plants are an excellent source of biomass energy due to the sequestered carbon dioxide and ensuing host of organics comprising them;3 photosynthesis in plants occurs most optimally by absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.4 Therefore, plants are an ideal source of renewable energy5 and a sustainable resource with superb advantages.6 Biomass provides clean energy, reduces dependency on fossil fuels and burden on landfills. Most importantly, it can be used to produce wide-ranging platform chemicals such as glucose, fructose, vanillin, and others.7 which can be further upgraded into biofuels, solvents and pharmaceutical scaffolds.8 However, reported industrial processes for upgrading of biomass have presented several obstacles9 and are often plagued with higher capital costs, large physical space burdens, as well as energy demands in terms of harvesting and collection.10 Therefore, the need for a sustainable, efficient and low-cost biomass upgrade process is required, preferably one that can be deployed locally in the form of modular and portable units to reduce the biomass bulk at the source to manageable amounts and alleviate transportation requirements. Modern research and development advancements in chemical processing11 have made it possible to shorten process time and reduce energy consumption by deploying innovative and progressive intensification techniques.12–14 Eco-friendly metal catalysts have been often used for upgrading of biomass,15 with a recent example being a photoactive bimetallic catalyst for the conversion of 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde (Vanillin), a common component of lignin, to 2-methoxy-4-methylphenol, a potential biofuel.16 Varma et al. further demonstrated the same method can generate γ-valerolactone from the biomass-derived levulinic acid under the visible light.17 However, these methods require extended reaction times and setup; in general, the current strategy for the conversion and upgrading of biomass are very energy and time demanding endeavors.18 The use of a continuous flow reactor for this purpose appears to be an ideal alternative to the batch process with proven advantages of flow chemistry over those of traditional methods.19 A rapid mixing of reagents promotes more frequent molecular interactions resulting in a faster reaction, quicker process optimization, and greater formation of the selective product(s).20

In this paper, we demonstrate the conversion of biomass-derived materials into value added chemicals that can be used as a potential source of biofuels, solvents, and pharmaceutical feedstocks. This is accomplished by using a continuous flow reactor in the presence of a bimetallic catalyst, consisting of silver and palladium nanoparticles over a graphitic carbon nitride surface (AgPd@g-C3N4), and formic acid from biomass origin as a hydrogen source; inherently photoactive graphitic carbon nitride support is readily obtainable from urea.16 The graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) was preferred as support for the synthesis of AgPd@g-C3N4 catalyst due to its nitrogenous framework which holds metal nanoparticles firmly and evade the metal leaching in the recycling process.

Result and discussion

The AgPd@g-C3N4 catalyst was synthesized by the impregnation of silver and palladium nanoparticles over the graphitic nitride surface as reported in literature.16, 17 The bimetallic catalyst was then directly used for the upgrading of biomass in a 1/16” stainless steel coiled tube flow reactor, 10m in length, with an internal diameter of 0.8 mm and total internal dead volume of 5.03mL. The entire coil reactor was then immersed in an oil bath made up of a Paratherm® NF mineral oil and temperature uniformity was ensured by placing the oil bath on a continuously stirred magnetic hotplate. The temperature attained by the oil bath contributes to efficient heat transfer via a thin film of reaction mixture flowing through the coiled tube thus allowing it to rapidly reach the needed activation energy. The reaction mixture was pumped through the pre-heated coil via the inlet port using a peristaltic pump. This facilitated not only the lateral pushing of the fluid within the reaction zone, but also creating a highly mixed reaction fluid within the reactor. The reaction output (product mixture) was then collected at the exit port.

In order to obtain optimized reaction conditions generating high product yields, several experimental reactions were conducted. Initially, the conversion of 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde (Vanillin), a common lignin-derived component, into 2-methoxy-4-methylphenol was performed using the AgPd@g-C3N4 catalyst and formic acid as a source of hydrogen. Several parametric experiments were performed by varying the temperature and flow rate to obtain high product conversions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Reaction optimization for upgrading of vanillin using coil reactor

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Catalyst | Residence Time (min) | Temperature (°C) | Flow rate (rnL/rnm) | Conversiona |

| 1 | AgPd@g-C3N4 | 5 | r.t. | 1 | - |

| 2 | AgPd@.g-C3N4 | 6 | r.t. | 0.85 | - |

| 3 | AgPd@.g-C3N4 | 7 | r.t. | 0.7 | - |

| 4 | AgPd@g-C3N4 | 10 | r.t. | 0.5 | - |

| 5 | AgPd@.g-C3N4 | 16 | r.t. | 0.3 | - |

| 6 | AgPd@g-C3N4 | 50 | r.t. | 0.1 | traces |

| 7 | AgPd@.g-C3N4 | 50 | 40 | 0.1 | 23% |

| 8 | AgPd@.g-C3N4 | 50 | 50 | 0.1 | 49% |

| 9 | AgPd@g-C3N4 | 50 | 60 | 0.1 | 81% |

| 10 | AgPd@g-C3N4 | 50 | 70 | 0.1 | 100% |

| 11 | AgPd@g-C3N4 | 50 | 75 | 0.1 | 100% |

| 12b | AgPd@.g-C3N4 | 50 | 70 | 0.1 | 100% |

| 13c | AgPd@.g-C3N4 | 50 | 70 | 0.1 | 100% |

| 14d | AgPd@.g-C3N4 | 50 | 70 | 0.1 | 100% |

| 15e | AgPd@g-C3N4 | 50 | 70 | 0.1 | 89% |

| 16 | Pd/C | 50 | 70 | 0.1 | 5% |

| 17 | Ru/C | 50 | 70 | 0.1 | 4% |

| 18 | Raney Ni | 50 | 70 | 0.1 | traces |

| 19 | AgPd@C | 50 | 70 | 0.1 | 31% |

| 20 | AgPd@Si02 | 50 | 70 | 0.1 | 33% |

| 21 | AgPd@GO | 50 | 70 | 0.1 | 29% |

| 22 | AgPd@Fe304 | 50 | 70 | 0.1 | 9% |

| 23 | AgPd@MgO | 50 | 70 | 0.1 | 6% |

Reaction condition:

Vanillin (1 mmol), formic acid (1.5 mmol), AgPd@g~C3N4 (100 mg), water(4.5 mL), methanol(0.5 mL),

75 mg of AgPd@g-C3N4,

50 mg of AgPd@g-C3N4,

25 mg of AgPd@g-C3N4,

15 mg of AgPd@g-C3N4

Vanillin was dissolved in a mixture of water and methanol in the presence of bimetallic catalyst and formic acid and was passed through the coil reactor that was equilibrated at room temperature, ambient pressure, and different flow rates (Table 1, entries 1–6). Only at a flow rate of 0.1mL/min that a trace amount of the desired product was obtained (Table 1, entry 6). Using this finding, more experiments were conducted by maintaining the same flow rate (0.1mL/min) and increasing the temperature of the reaction (Table 1, entries 7–11). As the reaction temperature was increased, the formation of 2-methoxy-4-methylphenol increased showing the reaction is temperature dependent (Table 1, entries 10–11). Further increasing the reaction temperature (to 75 oC) did not show any significant improvement quantitatively (Table 1, entry 11). Additional studies were then conducted by varying the quantity of the catalyst, AgPd@g-C3N4 (Table 1, entries 12–15); an optimal amount of the desired product was obtained using 25mg of catalyst (Table 1, entry 14). Commercially available catalysts (Table 1, entries 16–18) were also assessed for the hydrodeoxygenation of vanillin; less than 5% conversion was observed. In addition, other catalysts were synthesized and evaluated by changing the support from g-C3N4 to activated carbon, silica, graphene oxide, iron oxide and magnesium oxide; they all resulted in low conversion of the desired product (Table 1, entries 19–23).

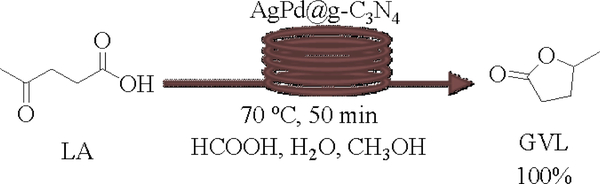

After the successful conversion of 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde to 2-methoxy-4-methylphenol via hydrodeoxygenation, we embarked on the synthesis of γ-valerolactone (GVL) via cyclative hydrogenation of biomass-derived levulinic acid (LA). Using the aforementioned optimized conditions (Table 1, entry 14), the experiment was conducted that afforded quantitative yield, 100% of the desired product, GVL (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of GVL

Conclusions

In conclusion, a simple high-yielding protocol has been developed that enables, in a continual flow operation, upgrading of lignin-derived phenolics into biofuels in the presence of a bimetallicAgPd@g-C3N4 catalyst. Conversion of levulinic acid to γ-valerolactone was also successfully accomplished using this bimetallic AgPd@g-C3N4 catalyst and formic acid as source of hydrogen rather than hydrogen gas. The mutual interaction and synergistic effect of silver and palladium nanoparticles with g-C3N4 support increases the degree of decomposition of formic acid into hydrogen. This makes bimetallic AgPd@g-C3N4 catalyst, a very efficient and highly active in hydrodeoxygenation and cyclative dehydrogenation reaction. This efficient method demonstrates that a continuous flow reactor is a viable alternative to the conventional method for upgrading of biomass in terms of energy, cost, and easily scalable operation for bulk production.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

KT and SV are ORISE participants at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Cincinnati, Ohio. This article was supported in part by an appointment to the ORISE Research Participant Program supported by an interagency agreement between EPA and DOE and may not necessarily reflect the views of EPA. No official EPA endorsement should be inferred.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or policies of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Any mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

An economically viable and environmentally benign continuous flow intensified process has been developed that demonstrates its ability to upgrade biomass into potential biofuels, solvents, and pharmaceutical feedstocks using a bimetallic AgPd@g-C3N4 catalyst.

Notes and references

- 1.a) Petrusa L and Noordermeer MA, Green Chem., 2006, 8, 861–867; [Google Scholar]; b) Liu B and Zhang Z, ACS Catal., 2016, 6, 326–338; [Google Scholar]; c) Safarik I, Pospiskova K, Baldikova E and Safarikova M, Biochem. Eng. J, 2016, 116, 17–26; [Google Scholar]; d) Chinnappan A, Baskar C and Kim H, RSC Adv., 2016, 6, 63991–64002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Isikgor FH and Becer CR, Polym. Chem, 2015, 6, 4497–4559; [Google Scholar]; b) Chakraborty S, Aggarwal V, Mukherjee D, Andras K, Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng, 2012, 7, S254–S262; [Google Scholar]; c) Alonso DM, Bond JQ and Dumesic JA, Green Chem., 2010, 12, 1493–1513; [Google Scholar]; d) Gallezot P, Chem. Soc. Rev, 2012, 41, 1538–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Taub DR, Nature Education Knowledge, 2010, 3, 21; [Google Scholar]; b) Verma R and Suthar S, BioEnergy Research, 2015, 8, 1589–1597; [Google Scholar]; c) McKendry P, Bioresource technology, 2002, 83, 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruan CJ, Shao HB and Teixeira da Silva JA, Crit. Rev. Biotechnol, 2012, 32, 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakakura T, Choi J-C and Yasuda H, Chem. Rev, 2007, 107, 2365–2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karp A and Shield I, New Phytologist, 2008, 179, 15–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Binder JB, Raines RT, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2009, 131, 1979–1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Corma A, Iborra S and Velty A, Chem. Rev, 2007, 107, 2411–2502; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sharma RK and Bakhshi NN, Can. J. Chem. Eng, 1991, 69, 1071–1081; [Google Scholar]; c) Alonso DM, Wettstein SG and Dumesic JA, Chem. Soc. Rev, 2012, 41, 8075–8098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Zhang Q, Chang J, Wang T and Xu Y, Energy Fuels, 2006, 20, 2717–2720; [Google Scholar]; b) Robinson AM, Hensley JE and Medlin JW, ACS Catal, 2016, 6, 5026–5043; [Google Scholar]; c) Xu X, Li Y, Gong Y, Zhang P, Li H and Wang Y J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2012, 134,16987–16990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Baxter L, Fuel, 2005, 84, 1295–1302; [Google Scholar]; b) Pentananunt R, Rahman AM and Bhattacharya SC, Energy, 1990, 15, 1175–1179. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varma RS, ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng, 2016, 4, 5866–5878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reddy BVV, Yalla S and Gonzalez MA, J. Flow Chem, 2015, 5, 172–177. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddy BVV, Gonzalez MA and Varma RS, Curr. Org. Chem, 2013, 17, 2268–2278. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez MA and Ciszewski JT, Org. Process Res. Dev, 2009, 13, 64–66. [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Besson M, Gallezot P and Pinel C, Chem. Rev, 2014, 114, 1827–1870; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yang C, Li R, Cui C, Liu S, Qiu Q, Ding Y and Zhang B, Green Chem., 2016, 18, 3684–3699. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verma S, Baig RBN, Nadagouda MN and Varma RS, Green Chem., 2016, 18, 1327–1331. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verma S, Baig RBN, Nadagouda MN and Varma RS, ChemCatChem, 2016, 8, 690–693. [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Singh AK, Jang S, Kim JY, Sharma S, Basavaraju KC, Kim M-G, Kim K-R, Lee JS, Lee HH and Kim D-P, ACS Catal., 2015, 5, 6964–6972; [Google Scholar]; b) Herbst A and Janiak C, CrystEngComm, 2017, DOI: 10.1039/C6CE01782G; [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c) Yung MM, Stanton AR, Iisa K, French RJ, Orton KA and Magrini KA, Energy & Fuels, 2016, 30, 9471–9479. [Google Scholar]

- 19.a) Gutmann B, Elsner P, Cox DP, Weigl U, Roberge DM and Kappe CO, ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng, 2016, 4, 6048–6061; [Google Scholar]; b) Pastre JC, Browne DL and Ley SV, Chem. Soc. Rev, 2013, 42, 8849–8869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.a) McQuade DT and Seeberger PH, J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 6384–6389; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Porta R, Benaglia M, and Puglisi A, Org. Process Res. Dev, 2015, 20, 2–25; [Google Scholar]; c) Feiz A, Bazgir A, Balu AM and Luque R, Sci. Rep, 2016, 6, 32719; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Gutmann B, Cantillo D and Kappe CO, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2015, 54, 6688–6729; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Gemoets HPL, Su Y, Shang M, Hessel V, Luque R and Neol T, Chem. Soc. Rev, 2016, 45, 83–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.