Abstract

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a global public health problem affecting approximately 2% of the human population. The majority of HCV infections (more than 70%) result in life-long persistence of the virus that substantially increases the risk of serious liver diseases, including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. The remainder (less than 30%) resolves spontaneously, often resulting in long-lived protection from persistence upon reexposure to the virus. To persist, the virus must replicate and this requires effective evasion of adaptive immune responses. In this review, the role of humoral and cellular immunity in preventing HCV persistence, and the mechanisms used by the virus to subvert protective host responses, are considered.

I. INTRODUCTION

The existence of hepatitis C virus(es) was first predicted 35 years ago to explain transfusion-associated liver disease in individuals not infected with the hepatitis A or B viruses (Alter et al., 1975; Feinstone et al., 1975; Prince et al., 1974). The description in 1989 of a single hepatitis C virus (HCV) that caused most posttransfusion and community acquired non-A non-B hepatitis marked a significant turning point toward understanding the epidemiology, natural history, and pathogenesis of this disease (Choo et al., 1989; Houghton, 2009). Seroepidemiology studies indicate that HCV has infected approximately 2% of the world’s population. The virus establishes persistent, life-long viremia in about 75% of infected humans and significantly increases the risk of progressive liver diseases, including inflammation, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. The discovery of HCV has also facilitated the development of new small molecule inhibitors of virus replication (designated STAT-C agents) that will soon be an adjunct to, and perhaps eventually replace, current standard therapy with pegylated type I interferon and ribavirin that is toxic, expensive, and frequently ineffective (Shimakami et al., 2009).

HCV is a member of the Flaviviridae and the prototype virus in the hepacivirus genus (Moradpour et al., 2007). It has a small RNA genome of about 10,000 nucleotides encoding a single polyprotein of 3000 amino acids that is processed by host cell and viral proteases into 10 in-frame proteins (Moradpour et al., 2007). At least one small frame-shifted protein of unknown function is also produced. Structural proteins include a core or nucleocapsid and two envelope glycoproteins. Seven nonstructural proteins are important for HCV replication. There are at least six distinct genotypes that can be further classified into subtypes defined by phylo-genetic relationships (Simmonds et al., 2005). HCV circulates as a population of different but closely related genomes in infected individuals (Simmonds et al., 2005). How the virus manages to avoid immune responses and establish life-long persistence is still a mystery. It is apparent that most viral proteins important for HCV replication also participate in evasion of innate and/or adaptive immune responses. As an example, the NS3 helicase/protease is critical for HCV replication and a prime target for small-molecule STAT-C inhibitors. NS3 protease activity also disrupts induction of innate immune defenses through RIG-I (retinoic acid inducible gene 1) and toll-like receptor 3 (TLR-3) sensors by cleavage of cellular intermediates important in signal transduction (Foy et al., 2003; Gale and Foy, 2005; Li et al., 2005). Despite the tremendous efficiency of HCV in establishing persistence, spontaneous clearance of infection in some individuals provides optimism that chronic hepatitis C can be prevented by vaccination and perhaps treated by immunotherapeutic approaches.

II. PATTERNS OF HCV REPLICATION

HCV replication and adaptive immune responses have been studied in humans and chimpanzees, the only species other than man with known susceptibility to infection. Transmission of non-A non-B hepatitis from humans to chimpanzees provided an animal model for initial characterization of the agent as a small enveloped RNA virus and paved the way for molecular cloning ofthe HCV genome (Alter et al., 1978; Hollinger et al., 1978; Tabor etal., 1978). Although there havebeen few detailed studies of the issue, spontaneous resolution of HCV infection may be more common in chimpanzees than in humans (Bassett et al., 1998; Lanford et al., 2001). Moreover, these animals do not develop serious progressive liver disease, at least in the time frame described for most human infections. Despite these differences, chimpanzees have been invaluable for comparison of immunity in HCV infections that spontaneously resolve or persist. The chimpanzee model has several important advantages for the study of HCV-specific humoral and cellular immunity. Animals can be infected with genetically defined strains of HCV, including molecular clones that are sequence-matched with antigens used to probe immunity. Moreover, serial liver and blood samples can be collected from the earliest times after virus challenge for studies of immunity.

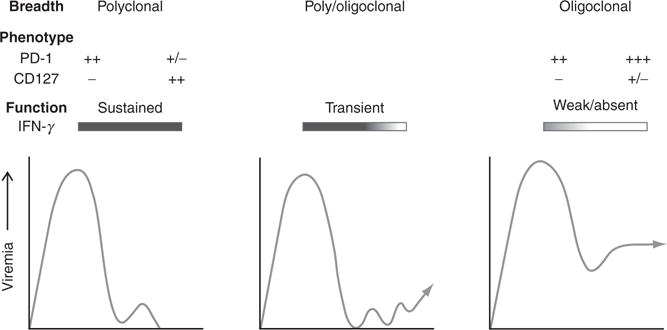

Patterns of acute phase HCV replication are well defined in both species (Abe et al., 1992; Fang et al., 2003; Larghi et al., 2002; Spada et al., 2004; Thimme et al., 2001, 2002). HCV RNA is detectable in serum within a few days of exposure to the virus and usually peaks 8–12 weeks later when serum transaminases are elevated. Three common patterns of viremia have been observed (Fig. 1). The first pattern leads to spontaneous resolution of infection. Peak viremia and serum transaminase levels are typically observed 8-12 weeks after infection and then drop sharply. This is followed by permanent clearance of HCV RNA from serum, sometimes after several weeks or months of low-level, fluctuating viremia. Spontaneous resolution appears to result in long-lived immunity that, at least for some, provides protection against HCV persistence upon reexposure to the virus (see Section IV). The second pattern is difficult to distinguish from the first because the sharp initial decline in acute phase viremia is also followed by a period of partial control so effective that HCV RNA is often intermittently undetectable in serum (Fig. 1). However, after a variable period of time (sometimes up to 1 year or more), viremia that is low and fluctuating transitions to a high, stable pattern characteristic of chronic hepatitis C (Abe et al., 1992; McGovern et al., 2009; Mosley et al., 2008; Thimme et al., 2001, 2002). In the third pattern of viremia, limited or no control of virus replication is observed before persistence is established (Fig. 1). Viremia is remarkably stable in the chronic phase of infection, although steady-state levels vary over a 2–3 log10 range among infected individuals (Arase et al., 2000; Fanning et al., 2000; Gordon et al., 1998; Nguyen et al., 1996; Thomas et al., 2000). In this review, recent evidence that adaptive immunity influences the pattern of acute phase virus replication and the outcome of infection is considered. Mechanisms of immune evasion important to persistence of this small RNA virus are also discussed.

FIGURE 1.

Three patterns of viremia have been described during the acute phase of HCV infection. In individuals who clear the infection (left panel), viremia peaks several weeks after infection when functional polyclonal CD4+ and CD8+ T responses targeting epitopes in most viral cell proteins are first detected in blood. CD8+ T cells lose expression of the coinhibitory molecule PD-1 and gain expression of the CD127 IL-7 receptor that is required for self-renewal of memory populations. Transient control of viremia can be observed for several months to a year after infection (middle panel). As indicated in the panel, these infections frequently persist, but resolution has also been observed after a prolonged period of low-level, fluctuating viremia. The end of transient virus control is associated with loss of CD4+ T helper cell function. Infections that persist without transient control of viremia have been described (right panel). T cell responses, if detected, are not sustained and usually target a limited number of epitopes. Most CD8+ T cells express high levels of PD-1. CD127 is low or absent. This exhausted phenotypic profile may be attenuated if the targeted viral epitope acquires an escape mutation (see Section IV, C1 and C2 for details).

III. HUMORAL IMMUNITY TO HCV

It has been known for two decades that seroconversion is substantially delayed during acute hepatitis C, with serum antibodies appearing several weeks after the initiation of virus replication regardless of infection outcome (Chen et al., 1999). Progress toward understanding the role of antibodies in HCV infection has been slow. This is due almost entirely to the technically challenging task of studying HCV attachment and entry into host cells, and whether this process is susceptible to neutralization by antibodies generated during infection. In the absence of a cell culture system supporting HCV replication, surrogate assays for virus binding, entry, and neutralization were developed using cell lines presumed to express viral receptors. As reviewed below, HCV ligands used in these cell culture models gradually evolved in sophistication from soluble recombinant envelope glycoproteins to synthetic virus-like particles (VLP) and finally retrovirus particles pseudotyped with HCV envelope glycoproteins (HCVpp). With the relatively recent advent of HCV strains that can complete the entire replication cycle in cell culture (designated HCVcc), it has been possible to validate and extend insights into the requirements for HCV entry, antibody-mediated neutralization, and evasion mechanisms.

A. Methods to study HCV entry and neutralization

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell production of a soluble recombinant E2 protein that was fully glycosylated and capable of binding conformation-dependent antibodies provided the first key reagent for studying HCV attachment to cells (Rosa et al., 1996). Binding of recombinant E2 to the Molt-4 T cell line as quantified by flow cytometry represented a key breakthrough in early efforts to identify cellular receptors for HCV and develop surrogate assays for antibody neutralization (Rosa et al., 1996). Expression cloning of cDNA libraries from Molt-4 cells revealed that the tetraspanin CD81 bound soluble recombinant E2 with high affinity (Pileri et al., 1998) and this interaction could be blocked by antibodies to E2 or CD81 (Rosa et al., 1996). Noninfectious VLP produced from insect cells that expressed the HCV core, E1 and E2 proteins have also been used to assess antibody-mediated blockade of cellular entry (Baumert et al., 2000). The approaches were largely superseded by the development of pseudoparticles containing rhabdo-(Lagging et al., 2002; Meyer et al., 2000) or retro-(Bartosch et al., 2003c; Hsu et al., 2003) virus core particles bearing HCV envelope glycoproteins. HCVpp containing retrovirus core particles are now widely used in entry and neutralization assays. They offer distinct advantages for studying the virus–host cell interaction, including the ability to pseudotype retrovirus core particles with E1 and E2 glycoproteins from different HCV strains and direct visualization of target cell transduction by incorporation of a reporter gene (Bartosch et al., 2003c; Hsu et al., 2003). As detailed below, HCVpp facilitated studies of the molecular interaction between E2 and cellular receptors, and neutralization of HCV entry into hepatoma cells by antibodies from infected or vaccinated humans and animals (Bartosch et al., 2003a; Logvinoff et al., 2004). HCVpp assays were validated by correlating in vitro neutralization with antibody-mediated protection of chimpanzees from infection (Bartosch et al., 2003a). While the HCVpp model remains important, the demonstration that select genotype 1a (Yi et al., 2006), 1b (Silberstein et al., 2010), and 2a (Lindenbach et al., 2005; Wakita et al., 2005; Zhong et al., 2005) HCVcc strains productively infect cultured cells provided a major new approach to dissect virus–host cell interactions. An HCV replicon containing all structural and nonstructural genes of a genotype 2a virus from a Japanese patient with fulminant hepatitis replicated in hepatoma cells without adaptive mutations and produced particles that could initiate infection in chimpanzees. HCVcc containing complete or recombinant JFH-1 genomes are now the most widely used adjunct to HCVpp for studies of virus neutralization and receptor-mediated entry into cells (Lindenbach et al., 2005; Zhong et al., 2005).

B. HCV attachment and entry

There is a consensus that E1 and E2 are critical for cellular attachment and entry because infection fails if HCVpp lack one of these envelope glycoproteins (Bartosch et al., 2003c; Drummer et al., 2003; Hsu et al., 2003). E1 and E2 exist as heterodimers in the lipid bilayer of the virus (Dubuisson and Rice, 1996; Lavie et al., 2007) and mediate cellular entry via clathrin-dependent endocytosis, delivering the viral genome from the early endosome to the cytoplasm by a pH-dependent fusion process (Blanchard et al., 2006; Meertens et al., 2006). One recent study integrated a model of E2 tertiary structure based on the position of nine disulfide bonds with published functional data to obtain a tentative map of the CD81 binding site and identify a candidate loop involved in fusion (Krey et al., 2010). However, crystal structures of the envelope glycoproteins have not yet been solved and so there is limited information on the location of neutralizing B cell epitopes relative to the functional domains of E2.

Internalization of HCVpp and HCVcc is, with few exceptions, restricted to cultured cells of the hepatocyte lineage, suggesting that the HCV host range is defined at least in part by the distribution of cellular receptor(s) for the virus (Bartosch et al., 2003b; Flint et al., 2006; Hsu et al., 2003; Lavillette et al., 2005b). The low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor (Molina et al., 2007), the C-type lectins dendritic cell (DC), and liver/lymph-node (L) specific intracellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing integrin (DC-SIGN and L-SIGN, respectively; Cormier et al., 2004; Lozach et al., 2003, 2004) and/or glycosaminoglycans (Barth et al., 2006) may facilitate virus attachment to target cells. For instance, ApoE associated with the virion can bind the LDL receptor on hepatocytes and blockade of this interaction interferes with HCV entry (Burlone and Budkowska, 2009; Owen et al., 2009). Four cellular proteins are required for virus internalization in cell culture models. These include CD81 (Bartosch et al., 2003b; Hsu et al., 2003; Lindenbach et al., 2005; Pileri et al., 1998), the scavenger receptor class member B1 (SR-B1; Bartosch et al., 2003b; Grove et al., 2007; Kapadia et al., 2007; Scarselli et al., 2002) and the tight junction proteins, claudin-1 (Evans et al., 2007) and occludin (Benedicto et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2009; Ploss et al., 2009). Claudin-6 and claudin-9 may substitute for claudin-1 in this process (Meertens et al., 2008; Zheng et al., 2007). Successful HCVpp and HCVcc infection of nonpermissive cells that coexpressed SR-B1, CD81, claudin-1, and occludin demonstrated that all four proteins were necessary for viral entry (Ploss et al., 2009). This approach involving transfection of human genes into rodent cells also facilitated mapping of cellular receptors that govern the species specificity of HCV entry. Receptor orthologues of rodent origin bind E2 with reduced efficiency and may interact less efficiently with human receptor components (Catanese et al., 2010; Haid et al., 2010; Ploss et al., 2009). How HCV is thought to interact with these cellular proteins for attachment, entry, and release of the viral genome into the cytoplasm of target cells is reviewed below.

CD81 and SR-B1 were first identified as viral receptors based on their physical association with soluble recombinant E2 proteins. The CD81 tetraspanin is widely expressed on human tissues and is important for signal transduction in a variety of cells, including B and T lymphocytes (Levy and Shoham, 2005). SR-B1 is restricted to liver cells and steroidogenic tissue and serves as a primary receptor for multiple ligands, including high-density lipoproteins (HDL), low-density lipoproteins (LDL), and very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL; Krieger, 2001). Experimental evidence implicating these proteins in virus entry is strong. Antibodies directed against CD81 or SR-B1, and siRNA-mediated silencing of the genes encoding these cellular proteins, substantially impair entry of HCVpp and/or HCVcc (Bartosch et al., 2003b; Kapadia et al., 2007; Lavillette et al., 2005b; Lindenbach et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2004). It is likely that they cooperate in the entry process because combination of antibodies to these cellular proteins also synergistically blocks HCVcc infection of hepatoma cells (Kapadia et al., 2007; Zeisel et al., 2007). Antibodies directed against CD81 can also block HCV infection of human hepatocytes grafted into immunodeficient mice (Meuleman et al., 2008). E2 binds the large extracellular loop (LEL) of CD81 via multiple discontinuous amino acids that have been mapped using monoclonal antibodies and by mutagenesis of E2 domains (Stamataki et al., 2008), and by identification of residues required for adaptation of E2 binding to murine CD81 (Bitzegeio et al., 2010).

SR-B1 is thought to bind hypervariable region 1 (HVR-1) that is located at the N-terminus of the E2 glycoprotein. Cellular entry of HCVpp that lack this E2 sequence cannot be blocked by SR-B1-specific antibodies (Bartosch et al., 2005). HCV and HDL appear to interact with distinct regions of SR-B1 because mutagenesis of the receptor impaired HCV infectivity without loss of HDL binding (Catanese et al., 2010). SR-B1 is involved in very early steps in virus entry, perhaps including initial virus attachment (Catanese et al., 2010), but a role in postbinding steps is also suggested by SR-B1 antibody blockade studies (Zeisel et al., 2007). Finally, infection of hepatoma cells can be enhanced or inhibited by HDL and oxidized LDL, respectively, indicating that the interplay between SR-B1, its natural ligands, and the virus is complex and not yet fully understood (Bartosch et al., 2005; Dreux et al., 2006; Voisset et al., 2006; von Hahn et al., 2006).

Soluble recombinant E2 was not used to identify claudin-1 and occludin as HCV receptors. Instead, these tight junction proteins were implicated in HCV entry by an iterative cloning strategy that depended on expression of cDNA libraries in cells that were not fully permissive for HCV infection. Physical interaction of these cellular proteins with E2, if it occurs, is poorly understood. An association between occludin and E2 in the endoplasmic reticulum has been reported (Benedicto et al., 2009), although the nature of the interaction and how it governs the entry process remains to be defined. Reduced expression of claudin-1 and occludin inhibited HCV glycoprotein-dependent cell-to-cell fusion, suggesting that both tight junction proteins act at a late stage of virus entry (Benedicto et al., 2009; Evans et al., 2007). How the virus contacts claudin-1 and occludin is unknown. The interaction of E2 and CD81 activates GTPase and this may mediate actin-dependent relocalization of the E2-CD81 complex to cell contact sites that contain tight junction proteins (Brazzoli et al., 2008). A physical interaction between claudin-1 and CD81 that is critical for HCV infection has been documented by mutagenesis (Harris et al., 2010) and antibody blockade studies (Krieger et al., 2010). Whether HCV enters cells via tight junctions is unknown, but two recent studies suggest that this is not essential at least in culture models involving hepatoma cell lines. Pools of nonjunctional claudin-1 that can complex with CD81 have been observed at the basolateral membrane of polarized hepatoma cells (Mee et al., 2009). Visualization of fluorescent-labeled HCV particles as they are internalized has provided evidence of a complex involving the virus, claudin-1, and CD81 that forms outside tight junctions (Coller et al., 2009; Harris et al., 2010; Mee et al., 2009). This model is attractive as it is consistent with virus entry into the liver through the sinusoidal blood supply and subsequent association with receptors on the basal surface of polarized hepatocytes (Stamataki et al., 2008).

C. Mapping of neutralization epitopes

E2 contains continuous (linear) and discontinuous (nonlinear) neutralizing epitopes involved in binding to CD81 and/or the SR-B1 viral receptors. Two of the best characterized regions containing linear epitope(s) are (i) the HVR-1 spanning amino acids 384–401 and (ii) an adjacent sequence spanning amino acids 413–420 of E2 (Owsianka et al., 2001, 2005; Tarr et al., 2006, 2007). Antibodies against HVR-1 are found in most if not all naturally infected humans but are isolate-specific and evolve continuously. A temporal correlation between the appearance of anti-HVR antibodies and the emergence of HCV variants provided the first presumptive evidence of an acute phase neutralizing response (Farci et al., 2000; Kato et al., 1993, 1994; Taniguchi et al., 1993; Weiner et al., 1992). Conversely, limited or no HVR-1 diversification was observed in viruses from humans with hypogamma-globulinemia or chimpanzees that failed to generate antibodies to E2 (Bassett et al., 1998; Booth et al., 1998; Penin et al., 2001; Puntoriero et al., 1998; Ray et al., 2000). Passive neutralization of HCV infectivity by anti-HVR antibodies before challenge of chimpanzees provided direct evidence that HVR-1 contains neutralizing epitope(s) (Farci et al., 1996).

The adjacent epitope spanning amino acids 413–420 that is involved in CD81 binding was first defined by monoclonal antibodies generated from rodents immunized with recombinant E2 (Owsianka et al., 2001, 2005; Tarr et al., 2006, 2007). In comparison to HVR-1, it is poorly recognized in naturally infected humans. Only 2.5% of sera from subjects with resolved or chronic hepatitis C recognized amino acids 413–420 of E2 (Tarr et al., 2007). The epitope defined by the rodent antibodies also differs from HVR-1 because it is highly conserved across most HCV genotypes (Broering et al., 2009; Owsianka et al., 2005). HCVcc with mutations in this conserved epitope can arise spontaneously (Dhillon et al., 2010) or by selection in the presence of the cognate neutralizing antibodies (Dhillon et al., 2010; Gal-Tanamy et al., 2008) during in vitro replication in hepatoma cells. Expanded use of these models of virus adaptation should provide new insights into the interaction of the virus with host cell receptors as well as mechanisms of antibody neutralization and evasion.

A number of conformation-dependent epitopes in E2 were also defined using antibodies from HCV-infected humans (Johansson et al., 2007; Keck et al., 2005, 2007; Law et al., 2008; Op De Beeck et al., 2004). Alanine-scanning mutagenesis and competitive binding assays with panels of human monoclonal antibodies, or antigen-binding fragments generated from phage display libraries, provided evidence for three conformational domains or regions (operationally designated A, B, and C) within E2 that are antigenic (Keck et al., 2004; Law et al., 2008). Antibodies targeting domain A epitopes are nonneutralizing and may be derived from isolated envelope proteins rather than virions (Keck et al., 2005; Law et al., 2008). Antibodies specific for domain B and C epitopes neutralized infectivity, probably by competitive inhibition of the CD81–E2 interaction. In support of this concept, many of the amino acids required for binding of the domain B antibodies (G530, D535, and W529; Johansson et al., 2007; Keck et al., 2008a, b, 2009; Law et al., 2008; Owsianka et al., 2008; Perotti et al., 2008) were identical to residues critical for E2 binding to CD81 (Johansson et al., 2007; Owsianka et al., 2006; Rothwangl et al., 2008). One recent study documented that a broadly cross-reactive monoclonal antibody directed against domain B provided protection from HCV infection in mice reconstituted with human hepatocytes (Law et al., 2008).

D. Antibody responses and infection outcome

Whether antibodies modify the course of HCV infection or contribute to spontaneous resolution is controversial. Direct evidence supporting involvement of the humoral immune response in control of HCV replication or resolution of infection is sparse. Spontaneous resolution without seroconversion has been observed in chimpanzees (Cooper et al., 1999) and humans (Christie et al., 1997; Post et al., 2004), including some with primary antibody deficiency (Christie et al., 1997). Although the number of subjects with hypogammaglubulinemia who permanently cleared viremia was small, this study provided support for the concept that anti-HCV antibodies are not necessarily required for a successful infection outcome (Christie et al., 1997). On the other hand, passive transfer of serum containing HCV immunoglobulins to chimpanzees substantially delayed, but did not prevent, replication of the virus upon challenge (Krawczynski et al., 1996), suggesting that antibodies can alter the trajectory of infection.

Studies conducted before validated neutralization assays were available suggested an association between the rapid onset of an antibody response to E2 and infection outcome. As an example, subjects who spontaneously resolved HCV infection were more likely to have serum antibodies against the E2 HVR within the first 6 months of infection when compared with those who developed persistent viremia, even when the timing of antibody responses to the core or nonstructural proteins was approximately the same (Dittmann et al., 1991; Zibert et al., 1997). This result was corroborated and extended by more recent studies employing the HCVpp neutralization assay. In a single-source outbreak of hepatitis C involving multiple subjects, HCV clearance was associated with rapid induction of neutralizing antibodies in the early phase of infection (Pestka et al., 2007). However, it remains uncertain if the neutralizing antibodies had a primary role in containment of infection or were simply a surrogate marker of a more effective T cell response.

A broad pattern of cross-reactivity against genetically diverse HCV strains by serum antibodies from persistently infected humans suggests continuous evolution of the virus. (Bartosch et al., 2003a; Kaplan et al., 2007; Lavillette et al., 2005b; Logvinoff et al., 2004; Meunier et al., 2005; Netski et al., 2005; Steinmann et al., 2004; von Hahn et al., 2007; Wakita et al., 2005). Few longitudinal studies have addressed this issue because construction of multiple HCVcc or HCVpp that incorporate serial envelope sequences that emerge over time is technically challenging. Nevertheless, HCVpp were used to study the evolution of neutralizing antibodies and envelope glycoprotein E2 in one subject, designated H, who provided serial serum samples over 26 years of acute and persistent HCV replication (von Hahn et al., 2007). Analysis of neutralization at the time of seroconversion revealed a response that was narrowly directed against the autologous virus (Logvinoff et al., 2004; von Hahn et al., 2007). Broadly cross-reactive antibodies were present 8 months later as persistent infection was established, but they did not neutralize HCVpp containing contemporaneous envelope glycoproteins. Emergence of the cross-reactive response was associated with diversification of E2 and loss of reactivity against the early HVR sequences encoded by the virus during the acute phase of infection (von Hahn et al., 2007). One recent detailed study of persistent viruses from subject H identified mutations in E2 that also facilitated escape from neutralizing antibodies targeting conformation-dependent domain B epitopes (Keck et al., 2009). Taken together, these data indicate that broadening of the neutralizing response was associated with loss of recognition of time-matched envelope glycoproteins, and are consistent with continuous escape of HCV under selection pressure from antibodies (von Hahn et al., 2007). Another study documented that neutralizing antibodies drive HCV envelope sequence evolution in humans that develop chronic infections (Dowd et al., 2009). Importantly, resolution of acute hepatitis C was correlated with an antibody response that effectively neutralized autologous time-matched viruses (Dowd et al., 2009).

E. Attenuation and evasion of the humoral immune response

Studies in subject H indicate that HCV evades antibody responses in part by mutational escape of conformation-dependent epitopes like those in domain B and linear epitopes like HVR-1. HVR-1 may also play a unique role in mutational escape by serving as a decoy for neutralizing antibody responses against other functionally important but less mutable epitopes (Mondelli et al., 2001; Ray et al., 1999; von Hahn et al., 2007). It may be well adapted for this role because chemicophysical properties of HVR-1 important to receptor-mediated cellular entry appear to be highly conserved (Penin et al., 2001; Puntoriero et al., 1998) despite exceptional immunogenicity and capacity for rapid mutation (Mondelli et al., 2001; Ray et al., 1999; von Hahn et al., 2007). In addition to serving as a decoy for neutralizing antibody responses, HVR-1 may physically protect or mask adjacent epitopes from B cell recognition. For instance, most humans fail to recognize the epitope spanning amino acids 413–420 defined by the rodent monoclonal antibodies (Tarr et al., 2007). It has been proposed that this CD81 binding site is concealed from immune recognition by residues 384–401 that comprise the HVR-1 domain (Bankwitz et al., 2010). At least two other mechanisms that attenuate antibody recognition of E2 neutralizing epitopes have been described. The 11 N-linked glycosylation sites of E2 are occupied and mutation of those sites located near residues important for CD81 binding increased the sensitivity of HCV to neutralization by monoclonal antibodies and patient serum (Falkowska et al., 2007; Helle et al., 2007). Finally, it appears that nonneutralizing antibodies can interfere with humoral responses against epitopes critical to virus entry. For instance, antibodies to two E2 epitopes (mapped to amino acids 412–426 and 434–446) were recently isolated from the plasma of humans with chronic hepatitis C. Peptide blockade or immunoaffinity depletion of serum antibodies against the 434–446 epitope revealed potent residual neutralizing activity against the adjacent 412–426 epitope of multiple HCV genotypes (Zhang et al., 2009).

HCV may also evade neutralization by direct cell-to-cell transfer of virus (Timpe et al., 2008; Witteveldt et al., 2009) or masking of E2 epitopes by lipids. Density and sedimentation properties of virions in human serum provided evidence for a physical association with lipoproteins (Kanto et al., 1995; Nielsen et al., 2006; Prince et al., 1996), including β-lipoprotein (Agnello et al., 1999; Prince et al., 1996; Thomssen et al., 1992; Wunschmann et al., 2000). Furthermore, involvement of the VLDL pathway in the assembly and release of HCVcc particles from cultured hepatoma cells has now been documented (Chang et al., 2007; Huang et al., 2007; Lavillette et al., 2005a). The hypothesis that virions associated with lipoproteins are less sensitive to antibody-dependent neutralization is supported by the observation that HDL facilitates HCVpp infection, and reduces the sensitivity of the virus to antibody-mediated neutralization (Bartosch et al., 2005; Dreux et al., 2006; Lavillette et al., 2005a).

IV. CELLULAR IMMUNITY TO HCV

Several observations indicate a critical role for cell-mediated immunity in spontaneous resolution of HCV infection. To summarize, early studies of infection in humans and chimpanzees established a temporal kinetic relationship between initial control of acute phase viremia and expansion of functional CD4+ helper and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (Bowen and Walker, 2005a; Rehermann, 2009). To prevent persistence, these responses must be sustained past the point that viral genomes are eradicated from host cells. Indeed, as reviewed below, premature failure of the acute phase CD4+ T helper cell response may be the best predictor of persistence. Immunogenetic associations between the outcome of infection and expression of specific HLA class I and II alleles also support the concept that T cells influence the course of infection (Singh et al., 2007). As an example, one recent study confirmed that the DRB1*0101 class II allele and certain alleles belonging to the HLA-B*57 class I group were associated with an absence of HCV RNA in a large multiracial group of HCV seropositive women (Kuniholm et al., 2010). Animal studies have provided the most direct evidence for involvement of T cells in infection outcome. Antibody-mediated depletion of CD4+ or CD8+ prolonged T cells from immune chimpanzees resulted in or persistent infection upon rechallenge with HCV (Grakoui et al., 2003; Shoukry et al., 2003). Moreover, vaccination of chimpanzees with genes encoding nonstructural proteins substantially blunted acute phase viremia after experimental challenge with HCV (Folgori et al., 2006). Because this genetic vaccine did not encode envelope glycoproteins that elicited neutralizing antibodies, it is reasonable to conclude that T cells primed by the nonstructural proteins enhanced acute phase control of HCV replication (Folgori et al., 2006).

A. Methods to study HCV-specific T cell immunity

State of the art methods for determining the frequency, function, and phenotype of antiviral T cells have been adapted for the study of HCV infection in humans and chimpanzees (Yoon and Rehermann, 2009). Briefly, mononuclear cells are typically stimulated ex vivo with synthetic recombinant proteins or overlapping peptide sets that are usually closely matched to the polyprotein encoded by the HCV strain or genotype circulating in the infected individual(s). Virus-specific T cell responses are then measured using readouts like proliferation (for instance, incorporation of 3H-tdr or dilution of a membrane marker dye like CFSE) or cytokine production (by ELISpot or intracellular cytokine staining; Yoon and Rehermann, 2009). A key advantage of the cytokine readout is accurate quantification of functional HCV-specific T cells. If T cells lack function, as is frequently the case in chronic infections, direct visualization of virus-specific populations is preferable. Soluble tetrameric class I molecules that incorporate viral epitopes have been essential for visualization of HCV-specific T cells in persistent HCV infection (Shiina and Rehermann, 2009). Conjugation of a fluorophore to a class I “tetramer” facilitates detection of HCV-specific T cells isolated from blood or liver by flow cytometry regardless of whether they retain effector functions.

Lack of a cell culture model supporting virus replication hindered studies of the interaction between HCV-specific T cells and infected hepatocytes. This situation has improved with the development of genomic and subgenomic HCV replicons and HCVcc strains that replicate in hepatoma cells (Jo et al., 2009; Soderholm et al., 2006; Uebelhoer et al., 2008). For instance, these models can be used to assess activation or inhibition of T lymphocytes by infected cells, susceptibility of virus replication to T cell cytotoxic activity or cytokine production, and the impact of immune escape mutations on viral fitness for replication (Jo et al., 2009; Soderholm et al., 2006; Uebelhoer et al., 2008).

Finally, there are some important limitations and caveats in the study of HCV-specific T cell immunity, particularly in persistently infected individuals. First and foremost, blood is the most accessible tissue but HCV-specific T cells are generally absent or present at low frequency in circulation (Bowen and Walker, 2005a). Whether circulating T cells are representative of intrahepatic populations is controversial. Most HCV-specific T cells are highly localized to the liver where effector functions and phenotype might differ. With the exception of explanted liver obtained during transplant, the tissue is commonly accessed only by percutaneous biopsy. From these small tissue samples, the number of recovered mononuclear cells is usually too low for direct assessment of T cell frequency, phenotype, or function. Moreover, serial liver biopsy of humans is uncommon, particularly during the acute phase of infection, and so evolution of the cellular immune response at the site of infection is difficult to study.

B. Acute phase T cell responses

T cells are present in blood and liver of most humans and chimpanzees with acute hepatitis C but the response is remarkably delayed when compared with many other viral infections. Although the kinetic is highly variable, expansion of T cells in blood is often not evident until 8–12 weeks after infection, coincident with the peak in serum transaminases and initial control of viremia (Fig. 1; Bowen and Walker, 2005a; Rehermann, 2009). This exceptionally long delay in generation of primary T cell immunity is unexplained, but is observed in most infections regardless of outcome. Available data strongly suggest that successful control of infection requires cooperation between CD8+ cytotoxic and CD4+ helper T cells.

1. CD8+ T cells

Acute phase CD8+ T cell responses in chimpanzees and humans that clear the infection are remarkably broad, targeting multiple unique class I restricted epitopes in all viral proteins (Cooper et al., 1999; Lechner et al., 2000b; Thimme et al., 2001, 2002), with the possible exception of the alternative reading frame protein designated F (Drouin et al., 2010). In blood CD8+ T cells frequencies against individual epitopes can exceed 3–4% when measured in functional assays or by tetramer analysis (Lechner et al., 2000b). Frequencies are almost certainly higher in the liver, the site of virus replication. During the acute phase of infection CD8+ T cells appear to expand in blood several days or weeks before they acquire effector functions (Lechner et al., 2000b; Shoukry et al., 2003; Thimme et al., 2001). The significance of this phenomenon is uncertain because effector activity (most notably the ability to produce IFN-γ) eventually recovers and is evident regardless of whether infections ultimately resolve or persist. CD8+ T cells that expand during the acute phase of infection transiently express the coinhibitory molecule programmed cell death 1 (PD-1; Kasprowicz et al., 2008; Radziewicz et al., 2008; Urbani et al., 2006b) and activation markers including HLA class II, CD38, and CD69 (Appay et al., 2002; Lechner et al., 2000a; Thimme et al., 2001; Urbani et al., 2006b). Resolution of HCV infection results in contraction of the CD8+ T cell response and enhanced expression of molecules associated with long-term memory including BcL-2 that inhibits apoptosis and CD127, a component of the IL-7 receptor that is required for self-renewal of memory populations (Badr et al., 2008; Golden-Mason et al., 2006; Urbani et al., 2006a). PD-1 expression is also lost or substantially reduced as virus load declines and the infection is terminated (Bowen et al., 2008; Kasprowicz et al., 2008; Radziewicz et al., 2007).

There is considerable heterogeneity in the strength of acute phase CD8+ T cell responses in those who follow a chronic course. Responses can be transiently detected in the blood of many subjects during acute hepatitis C and sometimes target multiple epitopes (Cox et al., 2005a; Kaplan et al., 2007; Lauer et al., 2005; Lechner et al., 2000a). Differences in the vigor of acute phase CD8+ T cell activity are illustrated by studies in chimpanzees experimentally infected with the virus (Gottwein et al., 2010; Thimme et al., 2002). Two animals in a recent study developed a persistent infection after HCV challenge, but one had CD8+ T cell activity against all HCV proteins and transient control of replication. CD8+ T cells from the other animal targeted one HCV protein and exerted limited if any antiviral activity (Gottwein et al., 2010). Where CD8+ T cell populations have been tracked from the acute to chronic phase of infection, responses that initially target several epitopes narrow dramatically as persistence is established (Cox et al., 2005a; Lauer et al., 2005; Lechner et al., 2000a). Even though responses are often more narrowly focused in the chronic phase of infection, there is no apparent preference for epitopes in the structural, nonstructural, and alternative reading frame proteins (Bain et al., 2004; Ward et al., 2002). It is likely that effector functions are lost sequentially during the transition from the acute to chronic phase of infection, as is the case in LCMV infection of mice where cytotoxicity and production of IL-2 fail early in infection, followed by IFN-γ production just before exhaustion is fully established (Shin and Wherry, 2007).

Intrahepatic CD8+ T cells that are a remnant of an earlier acute phase response can be recovered from the liver of humans and chimpanzees several years after persistence is established (Grabowska et al., 2001; He et al., 1999; Koziel et al., 1992; Meyer-Olson et al., 2004; Nelson et al., 1997; Wong et al., 1998). Many of these populations target class I epitopes that acquired escape mutations years earlier. However, some recognize intact epitopes but provide no apparent control of HCV replication (Erickson et al., 2001; He et al., 1999; Koziel et al., 1992; Nakamoto et al., 2008; Nelson et al., 1997; Neumann-Haefelin et al., 2008; Spangenberg et al., 2005; Wong et al., 1998), probably because they lack effector functions due to exhaustion (Golden-Mason et al., 2007a; Gruener et al., 2001; Kasprowicz et al., 2008; Nakamoto et al., 2008; Radziewicz et al., 2007; Spangenberg et al., 2005). Exhausted HCV-specific CD8+ T cells are prone to apoptosis unless rescued in cell culture by cytokines like IL-2 (Radziewicz et al., 2007). Unlike CD8+ T cells from those who resolve infection, CD127 is usually reduced or undetectable and PD-1 is constitutively expressed (Golden-Mason et al., 2007a; Kasprowicz et al., 2008; Nakamoto et al., 2008; Radziewicz et al., 2007; Urbani et al., 2006b). How T cells targeting intact and mutated epitopes survive in the persistently infected liver without any apparent mechanism for self-renewal is uncertain but probably depends on constant stimulation with HCV antigens. One intriguing possibility is that lymph nodes draining the liver are a site of CD8+ T cell renewal in chronic hepatitis C. Perihepatic lymph nodes from individuals with advanced hepatitis C were recently shown to harbor HCV-specific CD8+ T cells that appeared to retain effector functions when compared with those in the liver and blood (Moonka et al., 2008).

While most HCV-specific CD8+ T cells are exhausted, there is evidence that some populations have alternate functions that could facilitate persistence or modulate the course of infection. For instance, HCV-specific CD8+ T cells that produce IL-10 (Abel et al., 2006; Accapezzato et al., 2004; Kaplan et al., 2008; Rowan et al., 2008) and/or TGF-β (Alatrakchi et al., 2007; Rowan et al., 2008) have been observed in the blood and liver of persistently infected subjects. These cytokines are considered anti-inflammatory and have the potential to block effective antiviral immunity in acute or chronic phases of infection. Why CD8+ T cells would produce this set of suppressive cytokines is unclear, but one recent study has shown that ligation of the viral receptor CD81 drives naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to produce IL-13 (Serra et al., 2008). Antigen-specific stimulation of PBMC from individuals with chronic hepatitis C can also elicit IL-17, a proinflammatory mediator (Billerbeck et al., 2010; Rowan et al., 2008). Production of this cytokine appears to be associated with an expansion of CD8+ T cells that express CD161, a type C lectin also known as NKRP1A (Billerbeck et al., 2010; Northfield et al., 2008). Interestingly, CD8+ T cells with intense cell surface expression of CD161 had a unique phenotypic profile that included expression of the transcription factor retinoic acid-related orphan receptor γ-t, cytokine receptors (IL-23R and IL-18R) and chemokine receptors including CXCR6 that is important for liver homing (Billerbeck et al., 2010). CD8+ T cells that expressed CD161 were markedly enriched in liver and have the potential to modulate HCV replication or liver disease by production of IL-17 and IL-22 (Billerbeck et al., 2010).

2. CD4+ T cells

HCV-specific CD4+ T cells are particularly important to the outcome of infection, at least in part because they provide support for effector CD8+ T cells in acute hepatitis C. Loss of helper activity has been associated with poor CD8+ T cell function (Francavilla et al., 2004; Kaplan et al., 2007, 2008; Urbani et al., 2006a). Moreover, antibody-mediated depletion of CD4+ T cells from immune chimpanzees resulted in failure of CD8+ T cell-mediated control of HCV replication and emergence of viruses with escape mutations in class I restricted epitopes (Grakoui et al., 2003). A key role for CD4+ T cells is also indicated by the striking temporal relationship between control of acute viremia and detection of a functional, multispecific CD4+ T cell response in blood as first documented using proliferation assays (Diepolder et al., 1995; Gerlach et al., 1999; Missale et al., 1996). Acute phase CD4+ T cells are generally present at lower frequency and target fewer epitopes in infections that persist, even though transient responses that are indistinguishable from acute resolving infections have been described (Thimme et al., 2001). More recently, HLA class II tetramers were used to visualize HCV-specific CD4+ T cells in the blood of all HCV-infected subjects regardless of infection outcome (Lucas et al., 2007). CD4+ T cell populations remain detectable in the circulation of subjects who resolved the infection but frequencies dropped below the level of detection in those who followed a persistent course (Day et al., 2003; Lucas et al., 2007). This is consistent with comprehensive mapping of CD4+ T cell responses in individuals with chronic versus resolved infections (Day et al., 2002; Schulze zur Wiesch et al., 2005). CD4+ T cells targeting multiple epitopes were detected in the blood of subjects with resolved but not chronic infections (Day et al., 2002; Schulze zur Wiesch et al., 2005). Studies in humans subjects have demonstrated that transient control of HCV replication is lost if CD4+ T cells lose the ability to proliferate or produce antiviral (proinflammatory) cytokines like IFN-γ or IL-2 during the acute phase of infection (Gerlach et al., 1999; Ulsenheimer et al., 2003, 2006). HCV-specific CD4+ T cells can be recovered from the blood and liver of humans with chronic hepatitis C after stimulation with antigens and cytokines (Penna et al., 2002; Schirren et al., 2000) but whether they are functional in situ is unknown. An analysis of CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood demonstrated a selective loss in the ability to produce IL-2 even though IFN-γ production was retained (Semmo et al., 2005). Explanations for spontaneous CD4+ T cell failure in some infections remain poorly developed even though it is perhaps the most reliable predictor of HCV persistence.

C. Mechanisms for evading and silencing T cell responses

As noted above, CD4+ and CD8+that T cells are primed in most if not all HCV infections persist. Deletion of primed HCV-specific T cells from the repertoire has not been formally demonstrated, although the virus can exploit holes in the TcR repertoire in some individuals who develop a persistent infection (Wolfl et al., 2008). Multiple mechanisms have been proposed to explain the failure of intrahepatic T cells to control HCV infection. Inadequate priming by dysfunctional professional antigen presenting cells and/or an absence of innate signals may impair generation of an adaptive immune response (Szabo and Dolganiuc, 2008), but these features of HCV infection have not yet been precisely correlated with suboptimal T cell differentiation, survival, or effector function. Recombinant viral proteins can modulate T cell function in cell culture models by binding surface receptors. For instance, the HCV core protein can bind the gC1qR complement receptor on T cells, impairing proliferation and interferon-γ production by inhibiting Stat phosphorylation of SOCS signaling molecules (Cummings et al., 2009). Similarly, ligation of CD81 on naive CD4+ and CD8+ recently T cells by the E2 glycoprotein was reported to drive production of IL-13 (Serra et al., 2008). It is important to emphasize that the relevance of these mechanisms identified in cell culture models to HCV persistence has not yet been established in humans or chimpanzees. How binding of an HCV protein to a receptor that is widely expressed on resting or activated lymphocytes leads to a very specific lesion in HCV-specific T cell immunity, without imposing a more global suppressive effect on all T cells, remains to be explained.

Three mechanisms contributing to the evasion and silencing of T cell immunity against HCV will be considered in detail. They include (i) mutational escape of epitopes, (ii) expression of coinhibitory molecules that deliver negative signals to T cells, and (iii) regulatory T cell activity. Emerging data suggest that these mechanisms are interconnected and together may contribute to a profound, virus-specific defect in adaptive cellular immunity. Most published studies describe mechanisms of CD8+ T cell failure, but the fate of CD4+ T cells is also considered where data are available.

1. Mutational escape

The positive-stranded RNA genome of HCV is replicated by the error-prone RNA-dependent RNA polymerase encoded by the viral NS5b gene. The lack of a proofreading mechanism imparts on the virus a remarkable capacity for adaptive mutation. Mutations in class II epitopes have been reported to skew patterns of cytokine production (Wang et al., 2003), and antagonize (Frasca et al., 1999) or abrogate recognition (von Hahn et al., 2007; Wang and Eckels, 1999) by HCV-specific CD4+ T cells. Nevertheless, a pervasive pattern of class I epitope escape has not been observed in naturally infected humans (Fleming et al., 2010) or chimpanzees (Fuller et al., 2010), except perhaps in animals vaccinated before virus challenge (Puig et al., 2006). It is possible that CD4+ T cells do not consistently exert selection pressure against the virus, perhaps because they fail very early in acute infection. These results reinforce the view that helper activity is silenced by other as yet unidentified mechanisms. CD8+ T cells, on the other hand, are a potent selective force that act on HCV genomes to enrich for immune escape variants (Bowen and Walker, 2005b). This was first demonstrated in chimpanzees experimentally infected with a genetically defined HCV inoculum (Weiner et al., 1995). Identification of class I MHC epitopes and sequencing of viruses that emerged during the acute and chronic phases of infection provided the first statistical evidence that CD8+ T cells exert Darwinian selection pressure against some (but not all) class I epitopes (Erickson et al., 2001). This mechanism is also operational in humans where a persistent outcome of infection has been correlated with emergence of HCV escape variants (Cox et al., 2005b; Ray et al., 2005; Tester et al., 2005; Timm et al., 2004). Escape mutations that arise after several years of chronic infection have been described (Erickson et al., 2001; von Hahn et al., 2007). For instance in subject H an escape mutation in a class I epitope was observed more than two decades after persistent infection was established (von Hahn et al., 2007). Nevertheless, late escape may not be a common occurrence. Studies in chimpanzees (Fernandez et al., 2004) and humans (Kuntzen et al., 2007) indicate that the rate of nonsynonymous mutation is highest in the first few weeks or months of persistent infection, consistent with the view that CD8+ T cells can exert selection pressure for a limited period of time before they lose function (Cox et al., 2005a; Urbani et al., 2005).

Large populations of HCV sequences derived from HLA-defined humans have provided phylogenetic evidence of class I mutational escape (Neumann-Haefelin et al., 2008; Poon et al., 2007; Rauch et al., 2009; Timm et al., 2007). While these studies have yielded strong evidence for divergent evolution caused by CD8+ T cell selection pressure, many changes are often in the direction of an ancestral HCV sequence (Ray et al., 2005; Salloum et al., 2008; Timm et al., 2004). This pattern has been interpreted as evidence for reversion of escape variants that impair replicative fitness of the virus. Cell culture models of HCV replication support this view (Ray et al., 2005; Salloum et al., 2008; Timm et al., 2004). Growth of replicons or HCVcc engineered to contain some class I escape mutations is substantially impaired in cultured cells (Dazert et al., 2009; Soderholm et al., 2006; Uebelhoer et al., 2008). One of these studies examined a series of sequential escape mutations that appeared in one epitope of a genotype 1a virus as persistence was established in a chimpanzee (Erickson et al., 2001). Mutations that appeared in the epitope at the earliest time points after infection of the chimpanzee were least fit for replication in the cell culture model (Uebelhoer et al., 2008). It remains to be determined if these escape mutations also impair replication of the virus after it is transmitted to a new host, and the extent to which compensating adaptive mutations increase stability of amino acid substitutions that facilitate escape from antiviral CD8+ T cells.

The issue of whether mutational escape in class I epitopes is a cause or consequence of persistent infection remains unsettled. As noted above, not all class I epitopes targeted by CD8+ T cells escape and so it may not be a requirement for persistence. The percentage of epitopes that undergo mutation is highly variable, ranging from less than 20% of epitopes in some studies (Komatsu et al., 2006; Kuntzen et al., 2007) to greater than 60% in others (Cox et al., 2005b). The importance of escape mutations in some key epitopes is favored by studies in chimpanzees, where there was a statistically significant increase in the rate of nonsynonymous mutation in class I epitopes of viruses that persist when compared with those that are cleared (Erickson et al., 2001). In support of this statistical analysis, an association between escape mutation and loss of immune control early in infection has been documented in one study involving a limited number of subjects (Guglietta et al., 2009). Finally, immune selection pressure driven by CD8+ T cells might be altered by vaccination (Zubkova et al., 2009) or new antiviral therapies that target nonstructural HCV proteins important for virus replication. As an example, known drug resistance sites in the HCV protease and polymerase may overlap with class I epitopes, raising the possibility of HLA-associated immune resistance to the drugs (Gaudieri et al., 2009; Salloum et al., 2010).

2. Inhibitory receptor signaling

As noted above, some HCV class I epitopes remain intact during chronic infection even though cognate CD8+ T cells persist in the liver, sometimes at high frequency (Erickson et al., 2001; Spangenberg et al., 2005). This indicates that mechanism(s) other than mutational escape silence CD8+ T cells in persistent HCV infection. Functional exhaustion of HCV-specific CD8+ T cells targeting intact epitopes is almost certainly critical for persistence and may be mediated or reinforced by signaling through PD-1 that has an intracellular domain containing an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory (ITIM) as well as an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch (ITSM) motif. PD-1 ligation by its receptors, PD-L1 or PD-L2, impairs induction of the cell survival factor Bcl-xL and expression of transcription factors associated with effector cell function, including GATA-3, Tbet, and Eomes (Keir et al., 2008).

Establishing an association between PD-1 expression on T cells during acute hepatitis and the outcome of infection is complicated because this receptor is naturally upregulated on activated CD8+ T cells. PD-1 expression is elevated on HCV-specific CD8+ T cells during acute hepatitis C, but has not been consistently associated with resolution or persistence of infection (Kasprowicz et al., 2008; Radziewicz et al., 2008; Urbani et al., 2008). Very high levels of PD-1 expression are associated with caspase-9 dependent apoptosis of CD8+ T cells from individuals that ultimately develop a chronic infection (Radziewicz et al., 2008). Regulation of T cell function and survival during the acute phase of infection is probably determined by other positive and negative signals in addition to those delivered by PD-1. As an example, the costimulatory B7 ligand CD86 that is normally present on antigen presenting cells was coexpressed with PD-1 on HCV-specific CD8+ T cells and served as a unique marker of effective IL-2 signaling as measured by the phosphorylation state of STAT-5 (Radziewicz et al., 2010). Loss of CD86 and sustained expression of PD-1 on the T cell surface was observed as HCV persistence was established. Whether expression of molecules like CD86 transiently tempers or counter-balances inhibitory PD-1 signals during acute hepatitis C remains to be determined.

As noted above strong circumstantial evidence implicates PD-1 in maintenance of the persistent state once it has been established. HCV-specific CD8+ T cells in the blood and liver of persistently infected humans display high levels of PD-1 (Golden-Mason et al., 2007b; Penna et al., 2007; Urbani et al., 2006b, 2008) and the intrahepatic populations are prone to apoptosis (Radziewicz et al., 2007). Importantly, antibody-mediated block-ade of PD-1 signaling in cell culture models restores proliferation if not function to these exhausted CD8+ T cells (Golden-Mason et al., 2007b; Nakamoto et al., 2008; Radziewicz et al., 2007; Urbani et al., 2008). High, sustained expression of PD-1 on HCV-specific T cells, combined with restoration of function in the cell culture model by receptor blockade, suggests that anti-PD-1 antibodies could provide a therapeutic effect in patients with chronic infection. Early phase clinical trials of PD-1 blockade have been initiated to test in humans the safety of a strategy that could provide an important adjunct to direct suppression of HCV replication by antiviral agents (see ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00703469 for details).

Studies in the LCMV model of persistent infection predict that multiple inhibitory receptors coregulate CD8+ T cell exhaustion (Blackburn et al., 2009). PD-1 is not the only inhibitory molecule expressed by HCV-specific CD8+ T cells. Inhibitory receptors such as PD1, 2B4 (a SLAM-receptor that can deliver activating or inhibitory signals), CD160 (a coinhibitory glycoylphosphatidylinositol-anchored receptor), and KLRG1 (killer cell-lectin-like receptor G1) were coexpressed by many HCV-specific CD8+ T cells in one study (Bengsch et al., 2010). Collectively, they impaired proliferative capacity and effector functions in persistent infection. The inhibitory receptor cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4) was also preferentially upregulated on PD-1-positive T cells from the liver but not blood of chronically HCV-infected patients (Nakamoto et al., 2009). Coexpression of PD-1 and CTLA-4 inhibitory receptors on intrahepatic T cells was associated with a profound loss of virus-specific effector functions that could be reversed in cell culture by simultaneous blockade of the PD-1 and CTLA-4 signaling pathways (Nakamoto et al., 2009). In this study antibody-mediated inhibition of either receptor alone did not restore T cell function. Other receptors may also contribute to HCV-specific T cell exhaustion. Recently, coexpression of PD-1 and Tim-3 (the T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing molecule 3) was described on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in chronic hepatitis C, including some intrahepatic populations that were HCV-specific (Golden-Mason et al., 2009). Interference with TIM-3 signaling also restored antigen-stimulated proliferation of T cells and increased IFN-γ production while decreasing IL-10 output (Golden-Mason et al., 2009).

Finally, it is very likely that mutational escape of epitopes and exhaustion mediated by coinhibitory receptor signaling are interdependent. As an example, CD8+ T cells targeting escaped epitopes tend to express higher levels of CD127 and lower levels of PD-1 than those targeting intact epitopes in the acute (Rutebemberwa et al., 2008) and chronic (Bengsch et al., 2010; Kasprowicz et al., 2010) phases of infection. These studies suggest that continuous stimulation with viral antigens reinforces the exhausted phenotype. Expression of CD127, even at low levels, could explain persistence of CD8+ T cells targeting epitopes that have escaped. Whether these T cells truly retain some effector functions or a capacity for self-renewal that distinguishes them from those targeting intact epitopes remains unknown.

3. Regulatory CD8+ T cell activity

Two types of regulatory T cells (Treg) have been defined. They include natural Treg that develop in the specialized environment of the thymus and adaptive Treg that mature extrathymically (Sakaguchi et al., 2010). Phenotypic markers that uniquely define Treg are controversial, but most studies operationally use CD4, the transcription factor forkhead box P3 (FoxP3), and the IL-2Rα chain (CD25) to identify and manipulate these populations (Sakaguchi et al., 2010). Treg are thought to act by production of suppressive cytokines like IL-10 or TGF-β, or by receptor-mediated sequestration of IL-2 that is required for effector T cell activity (Bluestone and Abbas, 2003; Sakaguchi et al., 2010). These functional activities are important for maintenance of immune tolerance but also have the potential to modulate the course of HCV infection (Bluestone and Abbas, 2003; Sakaguchi et al., 2010). It has been proposed that they dampen HCV-specific effector T cell activity during the acute or chronic phases of infection, simultaneously contributing to a persistent state and tempering immunopathological damage to the liver.

At present, there is no direct experimental evidence that Treg activity during acute hepatitis C results in persistent infection. HCV infection of chimpanzees did provoke proliferation of Treg because T cell receptor excision circles in FoxP3-positive cells were diluted when compared to uninfected animals (Manigold et al., 2006). Functional FoxP3-positive CD4+ T cells have been expanded from blood of human subjects during the acute phase of HCV infection, but frequencies did not differ in subjects with acute resolving versus persistent outcomes (Smyk-Pearson et al., 2008). Similar results were obtained when HCV-specific Treg that expressed FoxP3 were visualized with MHC class II tetramers (Heeg et al., 2009). Only transient expansion of adaptive Treg was observed in blood and did not correlate with development of persistent viremia (Heeg et al., 2009). While it is possible that analysis of intrahepatic Treg function would reveal an influence on the outcome of acute hepatitis C, it is perhaps more likely that changes in the frequency and function of these regulatory T cells represent a response to the inflammatory environment in the liver of most infected individuals.

Treg may be active in the chronic phase of infection to reinforce exhaustion of effector T cells. Production of anti-inflammatory mediators like TGF-β and IL-10 by natural and adaptive CD4+ Treg was documented in chronically infected subjects (Ebinuma et al., 2008; Kaplan et al., 2008; Langhans et al., 2010; MacDonald et al., 2002; Ulsenheimer et al., 2003). Virus-responsive Treg from the blood of individuals with chronic hepatitis C have a stable FoxP3 phenotype and function, and may be genetically programmed for survival (Li et al., 2009). Others have documented that depletion of CD25-positive mononuclear cells from PBMC of subjects with chronic hepatitis C increased the frequency of T cells responding to HCV antigen stimulation in proliferation or IFN-γ ELISpot assays (Boettler et al., 2005; Cabrera et al., 2004; Rushbrook et al., 2005; Sugimoto et al., 2003). While this ex vivo experimental approach provided some preliminary circumstantial evidence for enhanced Treg activity in chronic hepatitis C, their importance in maintaining persistent HCV replication in the liver of infected humans has remained unresolved. Immunohistochemical staining has revealed that a high proportion of CD4+ T cells in the liver express the transcriptional regulator FoxP3 (Ward et al., 2007). One recent study confirmed that the liver harbors high frequencies of Foxp3 positive-Treg, and that they suppress effector T cell activity via a contact-dependent mechanism (Franceschini et al., 2009). Impressively, the frequency of intrahepatic Foxp3 positive-Treg correlated directly with serum HCV virus load and inversely with hepatocellular injury. These Treg also expressed exceptionally high levels of PD-1 that modulated suppressive activity upon ligation of PD-L1 that is expressed on liver parenchymal cells. Antibody-mediated inhibition of PD-1 signaling relieved a block on IL-2 driven STAT-5 phosphorylation, resulting in enhanced proliferation and suppressive activity by Treg (Franceschini et al., 2009). Finally, while some of the intrahepatic Treg proliferated in response to HCV antigens, the proportion that are natural versus adaptive (i.e., antigen-specific) remains to be determined.

V. IMMUNITY ACQUIRED BY NATURAL INFECTION CAN PROTECT AGAINST HCV PERSISTENCE: IMPLICATIONS FOR VACCINATION

HCV-specific T cells are detectable in blood for at least two decades after resolution of infection even in humans who no longer have detectable antibody responses to the virus (Takaki et al., 2000). There is evidence that memory T cells primed naturally by successful resolution of infection protect against persistence upon reexposure to the virus. Studies involving humans serially exposed to the virus through intravenous drug use have provided valuable insight into this issue. Virus replication following reinfection of humans who spontaneously cleared a prior HCV infection is well documented so sterilizing immunity is probably uncommon if it occurs at all (Aberle et al., 2006; Aitken et al., 2008a; Grebely et al., 2006; Mehta et al., 2002; Micallef et al., 2007; Mizukoshi et al., 2008; Osburn et al., 2009; Page et al., 2009; van de Laar et al., 2009). However, the magnitude and duration of viremia is substantially decreased in secondary versus primary infection and is associated with HCV-specific T cell immunity (Aberle et al., 2006; Bharadwaj et al., 2009; Mehta et al., 2002; Mizukoshi et al., 2008; Osburn et al., 2009). Critical support for the role of memory T cells in HCV reinfection was generated using the animal model. Rechallenge of immune chimpanzees often resulted in low-level transient virus replication (Bassett et al., 2001; Lanford et al., 2004; Major et al., 2002) that was associated with recall of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses (Grakoui et al., 2003; Nascimbeni et al., 2003; Shoukry et al., 2003). Antibody-mediated depletion of CD4+ helper (Grakoui et al., 2003) or CD8+ cytotoxic (Shoukry et al., 2003) T cells from immune chimpanzees caused prolonged or even persistent infection. It is important to note that protection afforded by successful resolution of one HCV infection is not absolute in humans or chimpanzees. This is perhaps best illustrated by an animal study where transient virus replication was observed after multiple sequential infections before persistence was finally established (Bukh et al., 2008). Moreover, some humans with chronic hepatitis C harbor T cells that target HCV strains or genotypes unrelated to the persistent virus (Schulze Zur Wiesch et al., 2007; Sugimoto et al., 2005). It is likely that these T cells are a marker of an earlier resolved infection that ultimately failed to protect against persistence. Documented persistent infection in humans who had spontaneously cleared earlier infection(s) supports this interpretation (Mehta et al., 2002; van de Laar et al., 2009). It is possible that immunity is less effective against heterologous HCV genotypes (Prince et al., 2005), although sequential infection and clearance of unrelated HCV genotypes has been documented in animals (Bukh et al., 2008; Lanford et al., 2004) and humans (Aitken et al., 2008b). A key unanswered question is whether immunity primed by natural infection can be recapitulated by vaccination. As noted above, vaccination of chimpanzees with nonstructural HCV proteins does not prevent infection with HCV (Folgori et al., 2006). However, the course of infection was altered because acute phase viremia was substantially reduced when compared to unvaccinated control animals (Folgori et al., 2006). These preliminary studies suggest that priming of T cells alone could be sufficient to shift the balance of most HCV infections away from persistence and toward resolution. However, the ability of the virus to undermine the response even when replication is substantially controlled cannot be underestimated and a comprehensive approach that involves priming of humoral and cellular immunity may be desirable (Frey et al., 2010; Houghton and Abrignani, 2005).

VI. SUMMARY

HCV is somewhat unique amongst human viruses in its ability to establish either persistent life-long infection or durable immunity that can protect against persistence after reexposure to the virus. This has provided a unique opportunity to define mechanisms of protective immunity and evasion by a small human RNA virus. Mutational escape from humoral and cellular immune responses is a common finding in humans and chimpanzees with a persistent outcome of infection. However, this mechanism alone cannot explain the remarkable ability of HCV to persist. Failure of the CD4+ T helper cell activity early in infection is likely a central event in subversion of B and CD8+ T lymphocyte responses and establishment of persistence. Mechanisms underpinning an HCV-specific defect in CD4+ T cell immunity remain very poorly understood. Closing this gap in knowledge would likely accelerate development of safe and effective vaccines.

HCV can also rapidly acquire resistance to STAT-C inhibitors targeting the protease and polymerase enzymes and so it is likely that they will be used in combination with type I interferon and ribavirin for the foreseeable future. How interferon and ribavirin inhibit the virus is not known, but could involve direct interference with replication, modulation of immunity, or both. Replacement of interferon and ribavirin is desirable because of toxicity and lack of a predictable therapeutic effect in humans. Further studies of adaptive immunity may suggest immunotherapeutic approaches to chronic hepatitis C that could be used in combination with small molecule inhibitors of HCV replication may provide substitutes. For instance, a detailed picture of how the virus utilizes CD81, SR-B1, and the tight junction proteins to initiate infection should facilitate development of attachment and entry inhibitors that may be useful in combination with STAT-C inhibitors. Finally, modulation of cellular immunity by interference with inhibitory signaling pathways like PD-1 and CTLA-4 could conceivably provide a well-defined approach to restoration of host responses capable of eradicating the infection.

References

- Abe K, Inchauspe G, Shikata T, Prince AM. Three different patterns of hepatitis C virus infection in chimpanzees. Hepatology. 1992;15:690. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840150423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel M, Sene D, Pol S, Bourliere M, Poynard T, Charlotte F, Cacoub P, Caillat-Zucman S. Intrahepatic virus-specific IL-10-producing CD8 T cells prevent liver damage during chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2006;44:1607. doi: 10.1002/hep.21438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aberle JH, Formann E, Steindl-Munda P, Weseslindtner L, Gurguta C, Perstinger G, Grilnberger E, Laferl H, Dienes HP, Popow-Kraupp T, Ferenci P, Holzmann H. Prospective study of viral clearance and CD4(+) T-cell response in acute hepatitis C primary infection and reinfection. J Clin Virol. 2006;36:24. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Accapezzato D, Francavilla V, Paroli M, Casciaro M, Chircu LV, Cividini A, Abrignani S, Mondelli MU, Barnaba V. Hepatic expansion of a virus-specific regulatory CD8(+) T cell population in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:963. doi: 10.1172/JCI20515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnello V, Abel G, Elfahal M, Knight GB, Zhang QX. Hepatitis C virus and other flaviviridae viruses enter cells via low density lipoprotein receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken CK, Lewis J, Tracy SL, Spelman T, Bowden DS, Bharadwaj M, Drummer H, Hellard M. High incidence of hepatitis C virus reinfection in a cohort of injecting drug users. Hepatology. 2008a;48:1746. doi: 10.1002/hep.22534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken CK, Tracy SL, Revill P, Bharadwaj M, Bowden DS, Winter RJ, Hellard ME. Consecutive infections and clearances of different hepatitis C virus genotypes in an injecting drug user. J Clin Virol. 2008b;41:293. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alatrakchi N, Graham CS, van der Vliet HJ, Sherman KE, Exley MA, Koziel MJ. Hepatitis C virus (HCV)-specific CD8+ cells produce transforming growth factor beta that can suppress HCV-specific T-cell responses. J Virol. 2007;81:5882. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02202-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alter HJ, Holland PV, Morrow AG, Purcell RH, Feinstone SM, Moritsugu Y. Clinical and serological analysis of transfusion-associated hepatitis. Lancet. 1975;2:838. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)90234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alter HJ, Purcell RH, Holland PV, Popper H. Transmissible agent in non-A, non-B hepatitis. Lancet. 1978;1:459. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)90131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appay V, Dunbar PR, Callan M, Klenerman P, Gillespie GM, Papagno L, Ogg GS, King A, Lechner F, Spina CA, Little S, Havlir DV, et al. Memory CD8 T cells vary in differentiation phenotype in different persistent virus infections. Nat Med. 2002;8:379. doi: 10.1038/nm0402-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arase Y, Ikeda K, Chayama K, Murashima N, Tsubota A, Suzuki Y, Saitoh S, Kobayashi M, Suzuki F, Kumada H. Fluctuation patterns of HCV-RNA serum level in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:221. doi: 10.1007/s005350050334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr G, Bedard N, Abdel-Hakeem MS, Trautmann L, Willems B, Villeneuve JP, Haddad EK, Sekaly RP, Bruneau J, Shoukry NH. Early interferon therapy for hepatitis C virus infection rescues polyfunctional, long-lived CD8+ memory T cells. J Virol. 2008;82:10017. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01083-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain C, Parroche P, Lavergne JP, Duverger B, Vieux C, Dubois V, Komurian-Pradel F, Trepo C, Gebuhrer L, Paranhos-Baccala G, Penin F, Inchauspe G. Memory T-cell-mediated immune responses specific to an alternative core protein in hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2004;78:10460. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10460-10469.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankwitz D, Steinmann E, Bitzegeio J, Ciesek S, Friesland M, Herrmann E, Zeisel MB, Baumert TF, Keck ZY, Foung SK, Pecheur EI, Pietschmann T. Hepatitis C virus hypervariable region 1 modulates receptor interactions, conceals the CD81 binding site, and protects conserved neutralizing epitopes. J Virol. 2010;84:5751. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02200-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth H, Schnober EK, Zhang F, Linhardt RJ, Depla E, Boson B, Cosset FL, Patel AH, Blum HE, Baumert TF. Viral and cellular determinants of the hepatitis C virus envelope-heparan sulfate interaction. J Virol. 2006;80:10579. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00941-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartosch B, Bukh J, Meunier JC, Granier C, Engle RE, Blackwelder WC, Emerson SU, Cosset FL, Purcell RH. In vitro assay for neutralizing antibody to hepatitis C virus: Evidence for broadly conserved neutralization epitopes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003a;100:14199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335981100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartosch B, Dubuisson J, Cosset FL. Infectious hepatitis C virus pseudo-particles containing functional E1-E2 envelope protein complexes. J Exp Med. 2003b;197:633. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartosch B, Vitelli A, Granier C, Goujon C, Dubuisson J, Pascale S, Scarselli E, Cortese R, Nicosia A, Cosset FL. Cell entry of hepatitis C virus requires a set of co-receptors that include the CD81 tetraspanin and the SR-B1 scavenger receptor. J Biol Chem. 2003c;278:41624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305289200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartosch B, Verney G, Dreux M, Donot P, Morice Y, Penin F, Pawlotsky JM, Lavillette D, Cosset FL. An interplay between hypervariable region 1 of the hepatitis C virus E2 glycoprotein, the scavenger receptor BI, and high-density lipoprotein promotes both enhancement of infection and protection against neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2005;79:8217. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8217-8229.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett SE, Brasky KM, Lanford RE. Analysis of hepatitis C virus-inoculated chimpanzees reveals unexpected clinical profiles. J Virol. 1998;72:2589. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2589-2599.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett SE, Guerra B, Brasky K, Miskovsky E, Houghton M, Klimpel GR, Lanford RE. Protective immune response to hepatitis C virus in chimpanzees rechallenged following clearance of primary infection. Hepatology. 2001;33:1479. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.24371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumert TF, Wellnitz S, Aono S, Satoi J, Herion D, Tilman Gerlach J, Pape GR, Lau JY, Hoofnagle JH, Blum HE, Liang TJ. Antibodies against hepatitis C virus-like particles and viral clearance in acute and chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2000;32:610. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.9876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedicto I, Molina-Jimenez F, Bartosch B, Cosset FL, Lavillette D, Prieto J, Moreno-Otero R, Valenzuela-Fernandez A, Aldabe R, Lopez-Cabrera M, Majano PL. The tight junction-associated protein occludin is required for a postbinding step in hepatitis C virus entry and infection. J Virol. 2009;83:8012. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00038-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]