Abstract

Background

Nivolumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor, has revolutionized the treatment of many cancers. Due to its novel mechanisms of action, nivolumab induces a distinct profile of adverse events. Currently, the incidence and risk of developing serious adverse events (SAEs) or fatal adverse events (FAEs) following nivolumab administration are unclear.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search for phase 2 and phase 3 nivolumab trials in PubMed and Embase from inception to June 2018. Data on SAEs/FAEs were extracted from each study and pooled to calculate the overall incidence and odds ratios (ORs).

Results

A total of 21 trials with 6173 cancer patients were included in this study. The overall incidence of SAEs and FAEs with nivolumab were 11.2% (95% CI, 8.7–13.8%) and 0.3% (95% CI, 0.1–0.5%), respectively. The incidence of SAEs varied significantly with cancer type and clinical phase, but no evidence of heterogeneity was found for FAEs. Compared with conventional treatment, the administration of nivolumab did not increase the risk of SAEs (OR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.34–1.40; p = 0.29) or FAEs (OR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.27–1.39; p = 0.24). SAEs occurred in the major organ systems in a dispersed manner, with the most common toxicities appearing in the respiratory (21.4%), gastrointestinal (7.7%), and hepatic systems (6.6%). The most common cause of SAEs/FAEs was pneumonitis.

Conclusions

Although nivolumab is a relatively safe antitumor agent, nononcologists should be advised of the potential adverse events. Additionally, future studies are needed to identify patients at high risk of SAEs/FAEs to aid in the development of optimal monitoring strategies and the exploration of treatments to decrease the risks.

Keywords: Serious adverse events, Fatal adverse events, Cancer, Nivolumab

Background

Immune suppression and evasion of malignant cancer cells are hallmarks of cancer [1]. A series of coinhibitory and costimulatory receptors and their ligands, known as immune checkpoints, control these processes. Among them, the programmed cell death protein 1(PD-1)/programmed death-ligand 1(PD-L1) axis stands out as a valuable therapeutic target [2]. The development and application of antibodies targeting PD-1 and PD-L1 have been major advances in cancer treatment [3]. Nivolumab, a fully human IgG4 monoclonal antibody against PD-1, has been approved for the treatment of many cancers [3].

It is well known that cancer treatment is usually a double-edged sword. Patients often tend to overestimate the benefit and to underestimate the disadvantages [4]. SAEs can lead to treatment discontinuation, hospitalization, or even death. Accordingly, information on SAE/FAE prevalence should play an important role in the decision-making process in clinical practice. Without fully understanding the risks of SAE/FAE, healthcare practitioners and patients cannot properly balance the benefits and risks. Previous work has shown that ipilimumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor targeting cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), was associated with significantly increased risks of treatment-related mortality [5]. Both nivolumab-related SAEs and FAEs have been reported in clinical practice [6–12] and have unfortunate consequences for the patients. Accordingly, it is important to fully investigate the toxicities related to this agent. However, the incidences and risk of SAEs/FAEs are often overlooked, partly due to the lack of data. The expanding application of nivolumab for the treatment of various cancers clearly necessitates rigorous and reliable information for evaluating nivolumab-related SAEs/FAEs. Moreover, as the use of nivolumab grows, nononcology specialists will be increasingly called upon to manage the rare but clinically important organ-specific adverse events and the more prevalent general adverse events related to immune activation. Based on accumulating evidence, our aim was to summarize nivolumab-related SAEs/FAEs and to estimate the incidence and risk of SAEs/FAEs by conducting a meta-analysis among adult patients with solid tumors.

Method

Search strategy

A systematic search of the Embase and PubMed databases from inception to June 2018 was conducted with no language restrictions. Conference proceedings from the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the European Society for Medical Oncology were also searched. The search keywords and medical subject headings used were (1) Nivolumab, Opdivo, ONO-4538, BMS-936558 and MDX1106; and (2) clinical trial. Three investigators independently performed the initial search, carefully screened the titles and abstracts for relevance, and identified trials as excluded, included and uncertain. For the uncertain studies, the full-texts were reviewed for the confirmation of eligibility. Any discrepancy was resolved by discussion.

Eligibility criteria

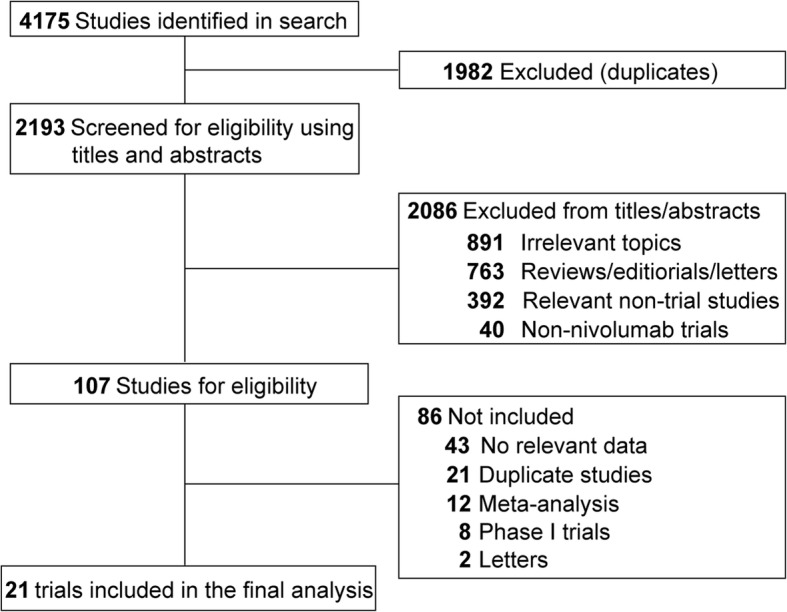

Both the inclusion and exclusion criteria were prespecified. To be eligible, studies had to meet the following criteria: (1) population: clinical phase 2 and phase 3 prospective trials involving adult patients (> 18 years old) with solid tumors; (2) intervention: at least one arm with nivolumab monotherapy; and (3) outcomes: available information on sample size, SAEs and FAEs. Phase I trials were not included because of the small sample size of patients and various doses in these studies. Other studies on this topic, including review articles, preclinical papers, early versions of data published later, editorials, and correspondences, were not included (Fig. 1). When multiple publications of the same study occurred, only the most recent and/or most complete study was included.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the eligible trials included in this study

Data extraction

An FAE is defined as death caused by nivolumab treatment, and an SAE refers to any adverse event (AE) that may lead to death, hospitalization or the prolongation of hospitalization, a life-threatening condition, congenital anomaly or birth defect, disability or permanent damage, or jeopardization of the patient’s health in a way that requires treatment to prevent one of the other outcomes. The attribution of FAEs or SAEs as treatment-related or disease-related depended on the decision of the primary investigators in the eligible studies. The information on ‘treatment-related SAE’ and ‘treatment-related FAE’ was extracted from the original publications. For all of the eligible studies, we also extracted the following information: first author’s name, year of publication, phase of the trial, cancer type, number of patients enrolled, median age, gender, treatment strategy, median treatment duration and median follow-up (Table 1). In addition, the median overall survival (OS) in each treatment arm, the hazard ratio (HR) for the OS, the number of participants evaluated for safety, the number of FAEs, and the number of SAEs were listed in Table 2. All data were extracted independently by three reviewers, and any discrepancies were resolved by discussion and consensus.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of trials included in this study

| Study | Trial phase | Underlying malignancy | No. of patients enrolled | Median age (range), year | Gender (Male/ Female) | Treatment | Median treatment duration (range), month | Median follow-up (range), month |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borghaei,2015 [6] | 3 | Lung cancer | 292 | 61(37–84) | 151/141 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 14 days | 3.0(0.5–26.0) | > 13.2 |

| 290 | 64(21–85) | 168/122 | Docetaxel 75 mg/m2 every 21 days | 3.0(0.8–17.3) | ||||

| Brahmer, 2015 [7] | 3 | Lung cancer | 135 | 62(39–85) | 111/24 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 14 days | 4.0(0.5–24.0) | < 11.0 |

| 137 | 64(42–84) | 97/40 | Docetaxel 75 mg/m2 every 21 days | 2.3(0.8–21.8) | ||||

| Carbone, 2017 [8] | 3 | Lung cancer | 271 | 63(32–89) | 184/87 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 14 days | 3.7(0–26.9) | 13.5 |

| 270 | 65(29–87) | 148/122 | Chemotherapy once every 21 days | 3.4(0–20.9) | ||||

| Ferris, 2016 [10] | 3 | Head and neck cancer | 240 | 59(29–83) | 197/43 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 14 days | 1.9 | 5.1(0–16.8) |

| 121 | 61(28–78) | 103/18 | Systemic therapy single-agent | 1.9 | ||||

| Kang, 2017 [9] | 3 | G/GJC | 330 | 62(54–69) | 229/101 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 14 days | 1.9 | 8.9 |

| 163 | 61(53–68) | 119/44 | Placebo 3 mg/kg every 14 days | 1.9 | 8.6 | |||

| Motzer, 2015 [11] | 3 | Renal cancer | 410 | 62(23–88) | 315/95 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 14 days | 5.5(0–29.6) | > 14.0 |

| 411 | 62(18–86) | 304/107 | Everolimus 10 mg daily | 3.7(0.2–25.7) | ||||

| Robert, 2015 [12] | 3 | Melanoma | 210 | 64(18–86) | 121/89 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 14 days | NR | < 16.7 |

| 205 | 66(26–87) | 125/83 | Dacarbazine 1 g/m2 every 21 days | NR | ||||

| Weber, 2017 [13] | 3 | Melanoma | 453 | 56(19–83) | 258/195 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 14 days | 12.0 | > 18.0 |

| 453 | 54(18–86) | 269/184 | Ipilimumab 10 mg/kg every 21 days | 3.0 | ||||

| Wolchok, 2017 [14] | 3 | Melanoma | 314 | 61(18–88) | 206/108 | Nivolumab 1 mg/kg + ipilimumab 3 mg/kg every 21 days | 6 | 38 |

| 316 | 60(25–90) | 202/114 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 14 days | 7.5 | 35.7 | |||

| 315 | 62(18–89) | 202/113 | Ipilimumab 3 mg/kg every 21 days | 3 | 18.6 | |||

| D’angelo, 2018 [15] | 2 | Sarcoma | 43 | 56(21–76) | 22/21 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 14 days | 2.3 | 13.6 |

| 42 | 57(27–81) | 19/23 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg + ipilimumab 1 mg/kg every 21 days | 3.7 | 14.2 | |||

| Long, 2018 [16] | 2 | Melanoma | 35 | 59(53–68) | 29/6 | Nivolumab 1 mg/kg + ipilimumab 3 mg/kg every 21 days | NR | 14.0 |

| 25 | 63(52–74) | 19/6 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 14 days | NR | 17.0 | |||

| 16 | 51(48–56) | 11/5 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 14 days | NR | 31.0 | |||

| Motzer, 2015 [19] | 2 | Renal cancer | 60 | 61 | 41/19 | Nivolumab 0.3 mg/kg every 21 days | 4.5(0–21.8) | > 24.0 |

| 54 | 61 | 40/14 | Nivolumab 2 mg/kg every 14 days | 5.6(0.8–24.0) | ||||

| 54 | 61 | 40/14 | Nivolumab 10 mg/kg every 14 days | 6.0(0.8–23.3) | ||||

| Hamanishi, 2015 [18] | 2 | Ovarian cancer | 20 | 60(47–79) | 0/20 | Nivolumab 1 or 3 mg/kg every 14 days | 3.5(1.0–12.0) | 11.0(3.0–32) |

| Hida, 2017 [29] | 2 | Lung cancer | 35 | 65(31–85) | 32/3 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 14 days | 3.6(0.5–29.3) | < 30.0 |

| Kudo, 2017 [30] | 2 | Esophageal cancer | 65 | 62(49–80) | 54/11 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 14 days | 105(0.5–5.0) | 10.8 |

| Maruyama, 2017 [31] | 2 | Hodgkin lymphoma | 17 | 63(29–83) | 13/4 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 14 days | 7.0(1.4–10.6) | 9.8(6.0–11.1) |

| Nishio, 2017 [32] | 2 | Lung cancer | 76 | 64(39–78) | 49/27 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 14 days | NR | 16.6(0.9–31.9) |

| Overman, 2017 [33] | 2 | Colorectal cancer | 74 | 53(44–64) | 44/30 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 14 days | 11.0 | 12.0 |

| Rizvi, 2015 [34] | 2 | Lung cancer | 117 | 65(57–71) | 85/32 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 14 days | 2.3 | 8.0 |

| Yamazaiki, 2017 [35] | 2 | Melanoma | 24 | 63(26–81) | 14/10 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 14 days | 11.9(0.5–21.0) | 18.8(2.0–21.5) |

| Younes, 2016 [36] | 2 | Hodgkin lymphoma | 80 | 37(28–48) | 51/29 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 14 days | 8.5 | 8.9 |

Abbreviation: G/GJC gastric and gastro-esophageal junction cancer

Table 2.

The risk and benefit of nivolumab treatment in cancer

| Study | Underlying malignancy | No. of patients enrolled | Median OS (95% CI), month | HR (95% CI) | P value | No. of patients (safety) | FAE | SAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borghaei,2015 [6] | Lung cancer | 292 | 12.2(9.7–15.0) | 0.73(0.59–0.89) | 0.002 | 287 | 1 | 21 |

| 290 | 9.4(8.1–10.7) | 268 | 1 | 53 | ||||

| Brahmer, 2015 [7] | Lung cancer | 135 | 9.2(7.3–13.3) | 0.59(0.44–0.79) | < 0.001 | 131 | 0 | 9 |

| 137 | 6.0(5.1–7.3) | 129 | 3 | 31 | ||||

| Carbone, 2017 [8] | Lung cancer | 271 | 14.4(11.7–17.4) | 1.02(0.80–1.30) | NR | 267 | 2 | 46 |

| 270 | 13.2(10.7–17.1) | 263 | 3 | 48 | ||||

| Ferris, 2016 [10] | Head and neck cancer | 240 | 7.5(5.5–9.1) | 0.70(0.51–0.96) | 0.01 | 236 | 2 | NR |

| 121 | 5.1(4.0–6.0) | 111 | 1 | NR | ||||

| Kang, 2017 [9] | G/GJC | 330 | 5.3(4.6–6.4) | 0.63(0.51–0.78) | < 0.0001 | 330 | 5 | 33 |

| 163 | 4.1(3.4–4.9) | 161 | 2 | 8 | ||||

| Motzer, 2015 [11] | Renal cancer | 410 | 25.0(21.8-not reached) | 0.73(0.57–0.93) | 0.002 | 406 | 0 | NR |

| 411 | 19.6(17.6–23.1) | 397 | 2 | NR | ||||

| Robert, 2015 [12] | Melanoma | 210 | Not reached | 0.42(0.25–0.73) | < 0.001 | 206 | 0 | 19 |

| 205 | 10.8(9.3–12.1) | 205 | 0 | 18 | ||||

| Weber, 2017 [13] | Melanoma | 453 | NR | NR | NR | 452 | 0 | NR |

| 453 | NR | NR | NR | 453 | 2 | NR | ||

| Wolchok, 2017 [14] | Melanoma | 314 | Not reached | NR | NR | 313 | 2 | NR |

| 316 | 37.6(29.1-not reached) | NR | NR | 313 | 1 | NR | ||

| 315 | 19.9(16.9–24.6) | NR | NR | 311 | 1 | NR | ||

| D’angelo, 2018 [15] | Sarcoma | 43 | 10.7(5.5–15.4) | NR | NR | 42 | 0 | 8 |

| 42 | 14.3(9.6-not reached) | NR | NR | 42 | 0 | 11 | ||

| Long, 2018 [16] | Melanoma | 35 | NR | NR | NR | 35 | 0 | 16 |

| 25 | NR | NR | NR | 25 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 16 | NR | NR | NR | 16 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Motzer, 2015 [19] | Renal cancer | 60 | 18.2 | NR | NR | 59 | 0 | NR |

| 54 | 25.5 | NR | NR | 54 | 0 | NR | ||

| 54 | 24.7 | NR | NR | 54 | 0 | NR | ||

| Hamanishi, 2015 [18] | Ovarian cancer | 20 | 20.0 | NR | NR | 20 | 0 | 5 |

| Hida, 2017 [29] | Lung cancer | 35 | 16.3(12.4–25.4) | NR | NR | 35 | 0 | 3 |

| Kudo, 2017 [30] | Esophageal cancer | 65 | 10.8(7.4–13.3) | NR | NR | 65 | 0 | 10 |

| Maruyama, 2017 [31] | Hodgkin lymphoma | 17 | NR | NR | NR | 17 | 0 | 6 |

| Nishio, 2017 [32] | Lung cancer | 76 | 17.1(13.3–23.0) | NR | NR | 76 | 0 | 15 |

| Overman, 2017 [33] | Colorectal cancer | 74 | NR | NR | NR | 74 | 0 | 9 |

| Rizvi, 2015 [34] | Lung cancer | 117 | 8.2(6.1–10.9) | NR | NR | 117 | 2 | NR |

| Yamazaiki, 2017 [35] | Melanoma | 24 | NR | NR | NR | 24 | 0 | 4 |

| Younes, 2016 [36] | Hodgkin lymphoma | 80 | NR | NR | NR | 80 | 0 | 5 |

Abbreviation: G/GJC gastric and gastro-esophageal junction cancer FAE, fatal adverse event SAE Serious adverse event; OS overall survival; CI confidence interval; HR hazard ratio; NR not reported

Statistical analysis

To calculate the incidence, the number of patients receiving nivolumab and the number of SAEs/FAEs were extracted from eligible studies. For the OR calculations, patients treated with nivolumab were compared with those assigned to a chemotherapy/placebo arm in the same trial. Four studies [13–16] were not included in the OR analysis because ipilimumab was administered in the control arms. When the trials reported no SAE/FAE in one arm, a classic half-integer continuity correction was used for the calculation.

Statistical heterogeneity across the trials was evaluated by Cochran’s Q statistic. The I2 statistic was calculated to assess the extent of inconsistency attributable to the heterogeneity across different studies [17]. The assumption of homogeneity was considered invalid for I2 > 25% or P < 0.05. The pooled ORs and incidences were calculated using a fixed-effects model or a random-effects model, depending on the heterogeneity of the included trials. To check the impact of various clinicopathological variables on FAEs, we further conducted post hoc subgroup analysis based on the underlying malignancy and clinical phase.

All analyses were conducted using MedCalc 13.0 (MedCalc Software, Belgium) and Stata 12.0 (StataCorp, USA). Two-sided P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Search results and study characteristics

A total of 4175 potentially relevant articles were identified from the initial search, including 2140 studies from PubMed and 2035 trials from Embase. A total of 1982 articles were excluded because of duplications. After the titles and abstracts were screened, 2086 studies did not meet the inclusion criteria. Upon further review of the whole texts of the remaining 107 potentially eligible articles, 21 trials (36 arms) with 6173 patients were enrolled for the final analysis (Fig. 1).

Within these 21 eligible studies, 9 were phase 3 RCTs, 3 were phase 2 RCTs, and 9 were single-arm phase 2 trials. Of the 36 arms, 7 arms were with chemotherapy/placebo, 3 arms were with nivolumab + ipilimumab, and 2 arms were with ipilimumab (Table 1), leaving a total of 24 arms of patients to be evaluated for the incidence of SAEs/FAEs with nivolumab. The number of patients per nivolumab arm with associated safety data ranged from 16 to 453 (average of 156), with a total of 3732 patients with SAE/FAE information available (Table 2). The most common cancer types were lung cancer (6 studies, 1623 patients) and melanoma (5 studies, 2366 patients). The dosage of nivolumab was 3 mg/kg every 14 days in all but two studies. In one trial, the applied dosage was 1 or 3 mg/kg [18], and dosages of 0.3, 2 and 10 mg/kg were applied in another trial [19]. The treatment duration with nivolumab ranged from 1.5 months to 11.9 months (average of 5.3 months).

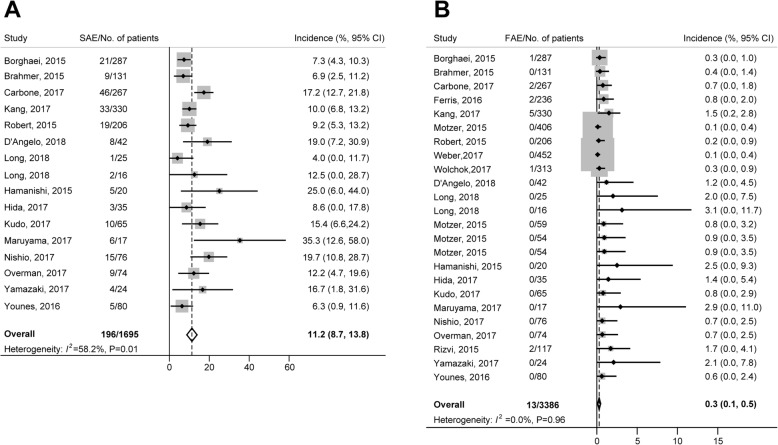

SAEs

Of the 21 trials included in our study, SAE information was unavailable in 6 trials; therefore, 15 studies (16 arms) were eligible for the analysis of SAE incidence (Table 2). A total of 1695 subjects receiving nivolumab monotherapy were included, and 196 SAEs were reported. Using a random-effects model (significant heterogeneity, I2 = 58.2%; P = 0.01), the overall incidence of SAEs was 11.2% (95% CI, 8.7–13.8%; Fig. 2A). The incidence of SAEs varied significantly with cancer type (P < 0.001) and clinical phase (P < 0.001). The incidence rates for different cancer types were, in decreasing order, ovarian cancer (25.0%), sarcoma (19.1%), colorectal cancer (12.2%), lung cancer (11.8%), Hodgkin lymphoma (11.3%), gastric/gastro-esophageal cancer (10.9%) and melanoma (9.6%). The causes of nivolumab-related SAEs are summarized in Table 3. The most common SAEs occurred in the respiratory (n = 42, 21.4%), gastrointestinal (n = 15, 7.7%), and hepatic systems (n = 13, 6.6%). The most common SAEs were pneumonitis (n = 16, 8.2%), interstitial lung disease (n = 11, 5.6%) and colitis (n = 7, 3.6%). It was noted that pneumonitis occurred in lung cancer (n = 14) and gastric or gastro-esophageal junction cancer (n = 2); interstitial lung disease occurred in lung cancer (n = 6), gastric or gastro-esophageal junction cancer (n = 4) and Hodgkin lymphoma (n = 1); and colitis occurred in lung cancer (n = 3), gastric or gastro-esophageal junction cancer (n = 2), colorectal cancer (n = 1) and melanoma (n = 1).

Fig. 2.

Overall incidence of SAEs (a) and FAEs (b) associated with nivolumab treatment FAE, fatal adverse event; SAE, serious adverse event

Table 3.

Specific causes for nivolumab-related SAE (serious adverse event) and FAE (fatal adverse event)

| Nivolumab-related AE | SAE (n = 196) | Disease type (n) | FAE(n = 13) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory events | 42(21.4%) | LC (30), G/GJC (9), HL (1), M (1), S (1) | 5(38.5%) |

| Pneumonitis | 16 | LC (14), G/GJC (2) | LC (2), G/GJC (1), HNC (1) |

| Interstitial lung disease | 11 | LC (6), G/GJC (4), HL (1) | 0 |

| Pleural effusion | 4 | LC (2), M (1), S (1) | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 2 | LC (1), G/GJC (1) | G/GJC (1) |

| Lung disorder | 2 | LC (2) | 0 |

| Lung infection | 2 | G/GJC (2) | 0 |

| Bronchitis | 1 | LC (1) | 0 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 | LC (1) | 0 |

| Hypoxia | 1 | LC (1) | 0 |

| Respiratory tract infection | 1 | LC (1) | 0 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 | LC (1) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal events | 15(7.7%) | LC (7), CC (3), G/GJC (2), S (2), M (1) | 0(0.0%) |

| Colitis | 7 | LC (3), G/GJC (2), CC (1), M (1) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 3 | CC (1), LC (1), S (1) | 0 |

| Nausea | 2 | LC (2) | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 1 | LC (1) | 0 |

| Anorexia | 1 | S (1) | 0 |

| Gastritis | 1 | CC (1) | 0 |

| Hepatic events | 13(6.6%) | LC (9), G/GJC (1), CC (1), HL (1), M (1) | 1(7.7%) |

| AST increased | 6 | LC (6) | 0 |

| Hepatotoxicity | 5 | LC (2), M (1), G/GJC (1), HL (1) | 0 |

| ALT increased | 1 | CC (1) | 0 |

| Transaminases increased | 1 | LC (1) | 0 |

| Hepatitis | 0 | NA | G/GJC (1) |

| Renal and urinary events | 9(4.6%) | LC (3), G/GJC (3), CC (1), HL (1), M (1) | 0(0.0%) |

| Blood creatinine increased | 2 | LC (2) | 0 |

| Hyponatremia | 2 | G/GJC (1), HL (1) | 0 |

| Acute kidney injury | 1 | CC (1) | 0 |

| Renal impairment | 1 | M (1) | 0 |

| Tubulointerstitial nephritis | 1 | LC (1) | 0 |

| Urinary tract infection | 2 | G/GJC (2) | 0 |

| Cardiovascular events | 6(3.1%) | LC (5), OC (1) | 2(15.4%) |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 2 | LC (2) | 0 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 | LC (1) | 0 |

| Cardiac tamponade | 1 | LC (1) | 0 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 1 | OC (1) | 0 |

| Pericardial effusion | 1 | LC (1) | 0 |

| Cardiac arrest | 0 | NA | G/GJC (1) |

| Ischemic stroke | 0 | NA | LC (1) |

| Nervous system events | 6(3.1%) | M (2), LC (2), OC (2) | 1(7.7%) |

| Encephalitis | 1 | LC (1) | LC (1) |

| Headache | 2 | M (2) | 0 |

| Disorientation | 1 | OC (1) | 0 |

| Dizziness | 1 | LC (1) | 0 |

| Gait disorder | 1 | OC (1) | 0 |

| Endocrine events | 6(3.1%) | LC (2), G/GJC (2), CC (1), HL (1) | 0(0.0%) |

| Adrenal insufficiency | 2 | LC (1), CC (1) | 0 |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | 2 | G/GJC (2) | 0 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 | HL (1) | 0 |

| Hypothyroidism | 1 | LC (1) | 0 |

| Musculoskeletal events | 5(2.6%) | LC (3), CC (2) | 0(0.0%) |

| Arthritis | 1 | CC (1) | 0 |

| Myasthenic syndrome | 1 | LC (1) | 0 |

| Osteonecrosis | 1 | LC (1) | 0 |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica | 1 | LC (1) | 0 |

| Pain | 1 | CC (1) | 0 |

| Blood events | 2(1.0%) | S (2) | 1(7.7%) |

| Anemia | 1 | S (1) | 0 |

| Decreased platelet count | 1 | S (1) | 0 |

| Neutropenia | 0 | NA | M (1) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue events | 1(0.5%) | HL (1) | 0(0.0%) |

| Rash | 1 | HL (1) | 0 |

| Other | 20(10.2%) | LC (6), G/GJC (5), HL (3), OC (2), S(2), M (1), CC (1) | 3(23.1%) |

| Pyrexia | 5 | LC (2), G/GJC (2), HL (1) | 0 |

| Infusion related reaction | 4 | LC (2), HL (2) | 0 |

| Fever | 3 | OC (2), S (1) | 0 |

| Dehydration | 3 | G/GJC (2), S (1) | 0 |

| Chills | 1 | LC (1) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 1 | G/GJC (1) | 0 |

| Radio-necrosis | 1 | M (1) | 0 |

| Stomatitis | 1 | CC (1) | 0 |

| Subdural hematoma | 1 | LC (1) | 0 |

| Multiorgan failure | 0 | NA | LC (1) |

| Hypercalcemia | 0 | NA | HNC (1) |

| Unknown reason | 0 | NA | G/GJC (1) |

Abbreviation: ALT alanine aminotransferase; AST aspartate aminotransferase; CC colorectal cancer; G/GJC gastric or gastro-esophageal junction cancer; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; HNC head and neck cancer; LC lung cancer; M melanoma; OC ovarian cancer; S sarcoma

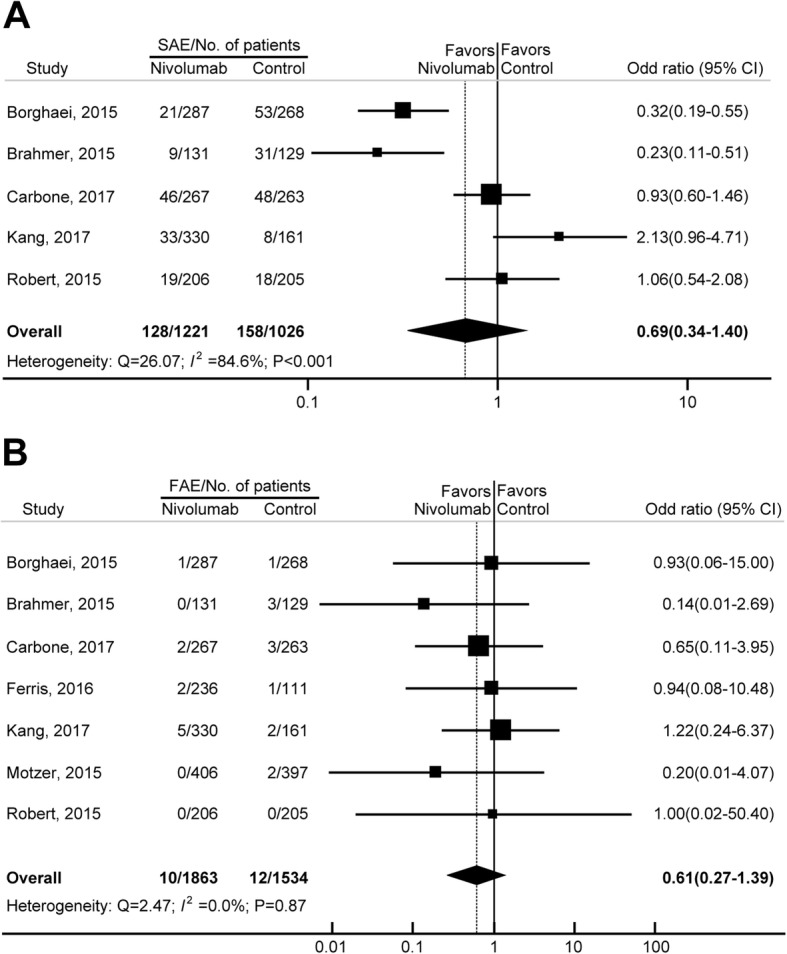

Of the 15 eligible studies, 8 trials were single-arm phase 2 studies, 2 trials included other immunotherapy as controls, and the 5 remaining studies were eligible for OR analysis. Among the 2247 patients (nivolumab: 1221; control: 1026) in these five RCTs, the overall OR of SAEs induced by nivolumab was 0.69 (95% CI, 0.34–1.40, P = 0.29; incidence 10.5% versus 15.40%; Fig. 3A), indicating no significantly increased risk of SAEs associated with nivolumab compared with the controls. This estimate was obtained using a random-effects model because a significant heterogeneity in the increased risk of SAEs with nivolumab treatment was revealed (Q = 26.07, I2 = 84.6%, P < 0.001). The cause for this heterogeneity was explored, and the OR of SAEs with nivolumab differed significantly by cancer type (P < 0.01). The risk for SAEs for different tumor types were, in decreasing order, gastric/gastro-esophageal cancer (OR, 2.13; 95% CI, 0.96–4.71); melanoma (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.54–2.08) and lung cancer (OR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.18–1.02).

Fig. 3.

Odds ratios (ORs) of SAEs (a) and FAEs (b) associated with nivolumab versus the controls

FAEs

In this study, 3386 cancer patients receiving nivolumab from 21 trials (24 arms) were included in the analysis of the incidence of FAEs. A total of 13 FAEs were reported. Using a fixed-effects model, the overall incidence of FAEs was 0.3% (95% CI, 0.1–0.5%; Fig. 2B). No significant heterogeneity was observed (heterogeneity test, I2 = 0.0%; P = 0.96). The incidence rates for various tumor types were, in decreasing order, gastric/gastro-esophageal cancer (1.27%), head and neck cancer (0.85%), lung cancer (0.55%) and melanoma (0.09%). The causes of nivolumab-related FAEs were 4 cases of pneumonia and one case each of encephalitis, multiorgan failure, hypercalcemia, hepatitis, cardiac arrest, exertional dyspnea, ischemic stroke, neutropenia, and unknown reason (Table 3).

Of the 21 eligible studies, 9 trials were single-arm phase 2 studies, 5 trials included other immunotherapy as controls, and the remaining 7 studies were eligible for OR analysis. Among the 3397 patients (nivolumab: 1863; control: 1534) in the 7 eligible RCTs, the overall OR of FAEs induced by nivolumab was 0.61 (95% CI, 0.27–1.39, P = 0.24; incidence 0.5% versus 0.8%; Fig. 3B), indicating that the risk of nivolumab-related FAEs was not significantly different from those in the control arms. No significant heterogeneity was identified, despite clear disparities in cancer type, treatment duration and control type (Q = 2.47; I2 = 0.0%; P = 0.87). Because no significant heterogeneity was observed, subgroup analyses were not conducted for FAEs. To account for any potential clinical heterogeneity not detected by our statistical tests, we also pooled the data using a random-effects model, and the OR and 95% CI remained unchanged.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study focused specifically on SAEs and FAEs among cancer patients treated with nivolumab. Based on 21 trials with 6173 patients, our results showed that the overall incidence of treatment-related SAEs and FAEs were 11.2% and 0.3%, respectively. SAEs/FAEs occurred in the major organ systems in a dispersed manner, with the most common toxicities appearing in the respiratory, gastrointestinal, and hepatic systems. Additionally, nivolumab administration did not increase the risk of SAEs/FAEs in adult patients with solid tumors. These findings demonstrated that nivolumab was a relatively safe antitumor agent and, therefore, should have clinical implications.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have dramatically improved the outlook of cancer treatment. It is also well established that these agents are associated with immune-related AEs, which can be fatal in some cases. It was reported that ipilimumab could increase the risk of mortality by 130% in cancer patients, with an overall FAE incidence of 1.13% [5]. Interestingly, thus far, numerous patients have received nivolumab therapy, and immune-related toxicities similar to those associated with anti-CTLA-4 have been observed; however, in general, the frequency was generally lower with nivolumab. It is possible that because the PD-1 and PD-L1 checkpoint acts later in the T cell response, which results in a more restricted T cell reactivity toward tumor cells, nivolumab is well-tolerated in clinical practice [20]. In addition, it should be noted that most of the ipilimumab studies were performed relatively early, when the knowledge about immune-related AEs was lower and the management guidelines for such AEs were not established.

Previous research revealed that nivolumab treatment had a significantly lower risk for any grade of AE compared with chemotherapeutics, and the most common any-grade AEs were fatigue, rush, pruritus, diarrhea, nausea and asthenia [21]. Fatigue alone occurred in over 25% of cancer patients treated by nivolumab. In contrast, our analysis demonstrated that nivolumab treatment and conventional therapy had similar risks for severe toxicities in terms of SAEs and FAEs. Nivolumab-related SAEs occurred in 10% patients and were dispersed in the major organ systems. The incidence of serious fatigue was much lower in patients treated with nivolumab (n = 1, 0.06%) because of early detection and proper management.

Our study shows that the most common SAEs were pneumonitis, interstitial lung disease, and colitis. The higher risk of both all-grade and high-grade pneumonitis with ICIs has been reported by several studies [22–24]. Moreover, we also revealed that nivolumab-induced pneumonitis was the most common cause of FAEs. The pooled incidences of all-grade and high-grade pneumonitis in patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors were 3.2% and 1.1%, respectively [24], while our data revealed that the incidence of serious nivolumab-related pneumonitis was 0.9%, and the incidence of FAEs caused by pneumonitis was 0.2%. Pulmonary toxicity constitutes the predominant nivolumab-related cause of mortality. Clinicians should pay attention to any patient presenting with pulmonary symptoms, including hypoxia, dry cough, and shortness of breath. Pathologically, treatment-related immune pneumonitis was believed to be similar to interstitial pneumonitis associated with collagen vascular disease. Radiologically, evidence of interstitial pneumonitis may be presented using high-resolution computed tomography [23].

Immune-related colitis is also an increasingly encountered SAE requiring appropriate management. However, a recent meta-analysis revealed that the incidence of colitis induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors was higher in ipilimumab-containing regimens compared with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors [25]. The incidences of all-grade and high-grade colitis in patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 were 1.3% and 0.9%, respectively [25], while our data demonstrated that the incidence of serious colitis was 0.4%.

The prevention of nivolumab-related SAEs/FAEs consists of early detection and aggressive treatment of potentially dangerous AEs, such as pneumonitis, colitis and hepatotoxicity. General management principles include temporary or permanent application of nivolumab. Moreover, the administration of immune modulatory drugs, like infliximab, glucocorticoids and azathioprine, has proved helpful in many studies [26, 27].

Our study has important clinical implications. It is reported that mortalities associated with adverse drug reactions account for approximately 5% of all hospital fatalities [28]. Accordingly, benefit/risk evaluation should play an essential role in the decision-making process during the selection of cancer treatments. Patients should recognize the increased risk of treatment-related mortality before consenting to any therapy. Our study could be important in considering the benefit/risk trade-off by providing the overall incidences and relative risks for SAEs/FAEs in patients treated with nivolumab.

Our study has several strengths. We performed a comprehensive review, utilizing the most up-to-date published data. All of the included original studies are phase 2 or phase 3 RCTs, which minimized selection bias. Moreover, with the accumulating evidence and enlarged sample sizes, this study had enhanced statistical power, leading to more reliable and precise clinical outcome estimates.

This study also has some limitations. First, our study is based on data from clinical trials rather than individual patients. This may include some confounding factors, such as previous therapies received, patients’ comorbidities, and concomitant medications. Second, clinical trials are usually not designed specifically to address toxic events; thus, asymptomatic adverse events may be ignored in the prospective assessment. Third, the incidence of SAEs among the eligible trials had significant heterogeneity. In this study, we adjusted this heterogeneity by applying a random-effects model to calculate the overall incidence.

Conclusions

In summary, nivolumab treatment did not increase the risk of serious and fatal drug-related adverse events. Considering that immune checkpoint inhibitors have shown important clinical benefit in numerous cancers, nononcologists should be advised of their potential adverse events. Additionally, future studies are needed to identify patients at high risk for SAEs/FAEs to aid in the development of optimal monitoring strategies and the exploration of treatments to decrease risks.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31571417 and No. 31600713), the Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province (No. H2016023 and No. QC2015109), the Health and Family Planning Commission Foundation of Heilongjiang Province (No. 2014–403), and the Start-up Foundation of Harbin Medical University (No. 2016 LCZX37). The funding sources had no role in the design and execution of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- CC

colorectal cancer

- CI

confidence interval

- CTLA-4

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4

- FAE

fatal adverse event

- G/GJC

gastric or gastro-esophageal junction cancer

- HL

Hodgkin lymphoma

- HNC

head and neck cancer

- HR

hazard ratio

- ICI

immune checkpoint inhibitor

- LC

lung cancer

- M

melanoma

- NR

not reported

- OC

ovarian cancer

- OS

overall survival

- PD-1

programmed cell death protein 1

- PD-L1

programmed death-ligand 1

- S

sarcoma

- SAE

Serious adverse event

Authors’ contributions

BZ, HZ, and JZ contributed to the conception and design of the study, the acquisition of data, and the analysis and interpretation of the data. They also wrote the original draft of the manuscript and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Bin Zhao, Email: doctorbinzhao@126.com.

Hong Zhao, Email: doctorhongzhao@126.com.

Jiaxin Zhao, Email: doctorzhaojiaxin@163.com.

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun C, Mezzadra R, Schumacher TN. Regulation and function of the PD-L1 checkpoint. Immunity. 2018;48(3):434–452. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ribas A, Wolchok JD. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science. 2018;359(6382):1350–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.aar4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffmann TC, Del Mar C. Patients' expectations of the benefits and harms of treatments, screening, and tests: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):274–286. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang S, Liang F, Li W, Wang Q. Risk of treatment-related mortality in cancer patients treated with ipilimumab: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2017;83:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, Spigel DR, Steins M, Ready NE, Chow LQ, Vokes EE, Felip E, Holgado E, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(17):1627–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, Crino L, Eberhardt WE, Poddubskaya E, Antonia S, Pluzanski A, Vokes EE, Holgado E, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(2):123–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carbone David P., Reck Martin, Paz-Ares Luis, Creelan Benjamin, Horn Leora, Steins Martin, Felip Enriqueta, van den Heuvel Michel M., Ciuleanu Tudor-Eliade, Badin Firas, Ready Neal, Hiltermann T. Jeroen N., Nair Suresh, Juergens Rosalyn, Peters Solange, Minenza Elisa, Wrangle John M., Rodriguez-Abreu Delvys, Borghaei Hossein, Blumenschein George R., Villaruz Liza C., Havel Libor, Krejci Jana, Corral Jaime Jesus, Chang Han, Geese William J., Bhagavatheeswaran Prabhu, Chen Allen C., Socinski Mark A. First-Line Nivolumab in Stage IV or Recurrent Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;376(25):2415–2426. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1613493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang YK, Boku N, Satoh T, Ryu MH, Chao Y, Kato K, Chung HC, Chen JS, Muro K, Kang WK, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer refractory to, or intolerant of, at least two previous chemotherapy regimens (ONO-4538-12, ATTRACTION-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10111):2461–2471. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31827-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferris RL, Blumenschein G, Jr, Fayette J, Guigay J, Colevas AD, Licitra L, Harrington K, Kasper S, Vokes EE, Even C, et al. Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1856–1867. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, George S, Hammers HJ, Srinivas S, Tykodi SS, Sosman JA, Procopio G, Plimack ER, et al. Nivolumab versus Everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(19):1803–1813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, Dutriaux C, Maio M, Mortier L, Hassel JC, Rutkowski P, McNeil C, Kalinka-Warzocha E, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):320–330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weber J, Mandala M, Del Vecchio M, Gogas HJ, Arance AM, Cowey CL, Dalle S, Schenker M, Chiarion-Sileni V, Marquez-Rodas I et al: Adjuvant Nivolumab versus Ipilimumab in resected stage III or IV melanoma. N Engl J Med 2017, 377(19):1824–1835. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Rutkowski P, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, Lao CD, Wagstaff J, Schadendorf D, Ferrucci PF, et al. Overall survival with combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1345–1356. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D'Angelo SP, Mahoney MR, Van Tine BA, Atkins J, Milhem MM, Jahagirdar BN, Antonescu CR, Horvath E, Tap WD, Schwartz GK, et al. Nivolumab with or without ipilimumab treatment for metastatic sarcoma (Alliance A091401): two open-label, non-comparative, randomised, phase 2 trials. The Lancet Oncology. 2018;19(3):416–426. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30006-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long GV, Atkinson V, Lo S, Sandhu S, Guminski AD, Brown MP, Wilmott JS, Edwards J, Gonzalez M, Scolyer RA, et al. Combination nivolumab and ipilimumab or nivolumab alone in melanoma brain metastases: a multicentre randomised phase 2 study. The Lancet Oncology. 2018;19(5):672–681. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamanishi J, Mandai M, Ikeda T, Minami M, Kawaguchi A, Murayama T, Kanai M, Mori Y, Matsumoto S, Chikuma S, et al. Safety and antitumor activity of anti-PD-1 antibody, Nivolumab, in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian Cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33(34):4015–4022. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.3397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Motzer RJ, Rini BI, McDermott DF, Redman BG, Kuzel TM, Harrison MR, Vaishampayan UN, Drabkin HA, George S, Logan TF, et al. Nivolumab for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase II trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33(13):1430–1437. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.0703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdel-Rahman O., Helbling D., Schmidt J., Petrausch U., Giryes A., Mehrabi A., Schöb O., Mannhart M., Oweira H. Treatment-related Death in Cancer Patients Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clinical Oncology. 2017;29(4):218–230. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tie Y, Ma X, Zhu C, Mao Y, Shen K, Wei X, Chen Y, Zheng H. Safety and efficacy of nivolumab in the treatment of cancers: a meta-analysis of 27 prospective clinical trials. Int J Cancer. 2017;140(4):948–958. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishino M, Giobbie-Hurder A, Hatabu H, Ramaiya NH, Hodi FS. Incidence of programmed cell death 1 inhibitor-related pneumonitis in patients with advanced Cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA oncology. 2016;2(12):1607–1616. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdel-Rahman O, Fouad M. Risk of pneumonitis in cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a meta-analysis. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2016;10(3):183–193. doi: 10.1177/1753465816636557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang S, Liang F, Zhu J, Chen Q. Risk of pneumonitis associated with programmed cell death 1 inhibitors in Cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16(8):1588–1595. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang DY, Ye F, Zhao S, Johnson DB. Incidence of immune checkpoint inhibitor-related colitis in solid tumor patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6(10):e1344805. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1344805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson DB, Friedman DL, Berry E, Decker I, Ye F, Zhao S, Morgans AK, Puzanov I, Sosman JA, Lovly CM. Survivorship in immune therapy: assessing chronic immune toxicities, health outcomes, and functional status among long-term Ipilimumab survivors at a single referral center. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3(5):464–469. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnston RL, Lutzky J, Chodhry A, Barkin JS. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 antibody-induced colitis and its management with infliximab. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(11):2538–2540. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0641-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Jama. 1998;279(15):1200–1205. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.15.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hida T, Nishio M, Nogami N, Ohe Y, Nokihara H, Sakai H, Satouchi M, Nakagawa K, Takenoyama M, Isobe H, et al. Efficacy and safety of nivolumab in Japanese patients with advanced or recurrent squamous non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2017;108(5):1000–1006. doi: 10.1111/cas.13225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kudo T, Hamamoto Y, Kato K, Ura T, Kojima T, Tsushima T, Hironaka S, Hara H, Satoh T, Iwasa S, et al. Nivolumab treatment for oesophageal squamous-cell carcinoma: an open-label, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(5):631–639. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30181-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maruyama D, Hatake K, Kinoshita T, Fukuhara N, Choi I, Taniwaki M, Ando K, Terui Y, Higuchi Y, Onishi Y, et al. Multicenter phase II study of nivolumab in Japanese patients with relapsed or refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Sci. 2017;108(5):1007–1012. doi: 10.1111/cas.13230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishio M, Hida T, Atagi S, Sakai H, Nakagawa K, Takahashi T, Nogami N, Saka H, Takenoyama M, Maemondo M, et al. Multicentre phase II study of nivolumab in Japanese patients with advanced or recurrent non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer. ESMO open. 2016;1(4):e000108. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2016-000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Overman MJ, McDermott R, Leach JL, Lonardi S, Lenz HJ, Morse MA, Desai J, Hill A, Axelson M, Moss RA, et al. Nivolumab in patients with metastatic DNA mismatch repair-deficient or microsatellite instability-high colorectal cancer (CheckMate 142): an open-label, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(9):1182–1191. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30422-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rizvi NA, Mazieres J, Planchard D, Stinchcombe TE, Dy GK, Antonia SJ, Horn L, Lena H, Minenza E, Mennecier B, et al. Activity and safety of nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, for patients with advanced, refractory squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 063): a phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(3):257–265. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70054-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamazaki N, Kiyohara Y, Uhara H, Uehara J, Fujimoto M, Takenouchi T, Otsuka M, Uchi H, Ihn H, Minami H. Efficacy and safety of nivolumab in Japanese patients with previously untreated advanced melanoma: a phase II study. Cancer Sci. 2017;108(6):1223–1230. doi: 10.1111/cas.13241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Younes A, Santoro A, Shipp M, Zinzani PL, Timmerman JM, Ansell S, Armand P, Fanale M, Ratanatharathorn V, Kuruvilla J, et al. Nivolumab for classical Hodgkin's lymphoma after failure of both autologous stem-cell transplantation and brentuximab vedotin: a multicentre, multicohort, single-arm phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(9):1283–1294. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30167-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.