Abstract

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is often accompanied by multiple comorbidities, which are associated with an increased risk of exacerbation, a poor health-related quality of life, and high mortality. However, differences in comorbidity profile by race and ethnicity in COPD patients have not been fully elucidated.

Methods

Participants aged 40 to 79 years with spirometry-defined COPD from the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (2007–2012) and from the Korea NHANES (2007–2015) were analyzed to compare the prevalence of comorbidities by race and ethnicity group. Comorbidities were defined using questionnaire data, physical exams, and laboratory tests.

Results

Non-Hispanic Whites had the highest prevalence of dyslipidemia (65.5%), myocardial infarction (6.2%), osteoarthritis (40.1%), and osteoporosis (13.6%), while non-Hispanic Blacks had the highest prevalence of asthma (24.0%), hypertension (70.2%), stroke (7.3%), diabetes mellitus (DM) (23.3%), anemia (16.4%), and rheumatoid arthritis (11.9%). Compared to non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks had a significantly higher prevalence of hypertension, stroke, DM, anemia, and rheumatoid arthritis after adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, and smoking status, while Hispanics had a significantly higher prevalence of DM and anemia, and Koreans had significantly lower prevalences of all comorbidities except stroke, DM, and anemia.

Conclusions

COPD-related comorbidities varied significantly by race and ethnicity, and different strategies may be required for the optimal management of COPD and its comorbidities in different race and ethnicity groups.

Keywords: COPD, Comorbidity, Race, Ethnicity

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common respiratory disease characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitations [1]. Due to the ongoing epidemic of smoking and to prolonged life expectancy, COPD is projected to increase in prevalence and to contribute over 4.5 million annual deaths worldwide by 2030 [2, 3].

Since aging and smoking are independent risk factors not only for COPD, but also for multiple chronic diseases, COPD is often accompanied by comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), osteoporosis, metabolic syndrome, depression, and several types of cancer [4]. Furthermore, in COPD patients, these comorbidities are associated with an increased risk of exacerbation [5], a poor health-related quality of life [6], increased utilization of health services [7], and high mortality [8]. As a consequence, recent COPD guidelines give special emphasis to the management of comorbid conditions in COPD [1].

COPD guidelines, however, have been developed using data primarily from populations of European descent. COPD and associated comorbidities have multiple genetic, behavioral, environmental, and socioeconomic risk factors, which may vary substantially across racial groups, like other diseases [9–11], but differences in comorbidity profile by race and ethnicity in COPD patients have not been fully elucidated. This study aimed to evaluate differences in comorbidity profile by race and ethnicity in subjects with COPD participating in nationally representative surveys from the United States and South Korea.

Methods

Participants

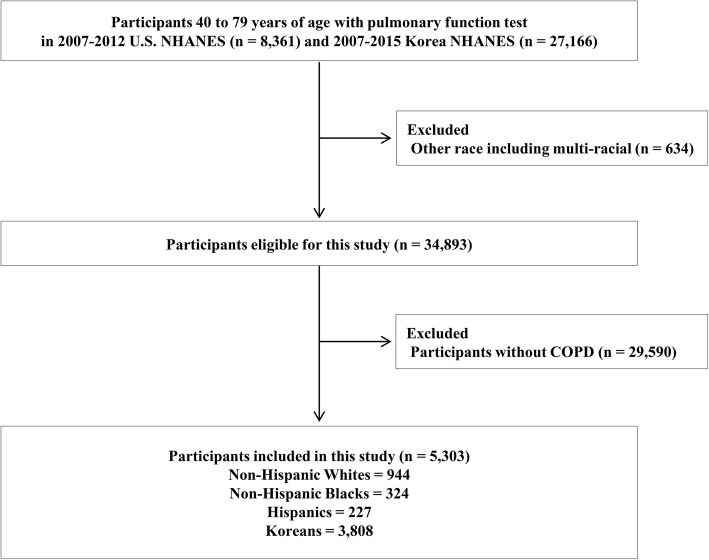

We used data from the 2007–2012 cycles of the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and from the 2007–2015 cycles of the Korea NHANES (KNHANES). Both surveys provide nationally representative data of the non-institutionalized population using a multi-stage cluster sampling design. We restricted our analysis to men and women 40 to 79 years old with spirometry-defined COPD [pre-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) / forced vital capacity (FVC) < 70%] [12]. Among U.S. NHANES participants, we further restricted the analysis to those who self-identified as Non-Hispanic White (n = 944), Non-Hispanic Black (n = 324), or Hispanic (n = 227). KNHANES provided a representation of Asians (n = 3808), as the number of Asian participants with COPD in U.S. NHANES was too small for comparisons (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study participants. COPD was defined as pre-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 s / forced vital capacity < 70%. COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, NHANES National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Spirometric measurement

In both surveys, spirometry was performed according to the recommendations of the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society [13]. Absolute values of FEV1 and FVC were obtained, and the percentage of predicted values for FEV1 and FVC were calculated using the reference equation obtained from an analysis of the general U.S. population for U.S. NHANES [14] and a representative Korean sample for KNHANES [15].

Definitions

COPD was defined based on pre-bronchodilator FEV1 / FVC < 0.7, and COPD severity was classified as mild (FEV1 ≥ 80% predicted), moderate (50% ≤ FEV1 < 80% predicted), or severe-to-very severe (FEV1 < 50% predicted) [1]. Height and weight were measured and body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Obesity was defined as BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m2 and overweight was defined as BMI = 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 in Non-Hispanic Whites, Non-Hispanic Blacks, and Hispanics, and as BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 for obesity and as BMI = 23.0–24.9 for overweight in Koreans according to World Health Organization guidelines [16].

Comorbidities were defined as a self-reported physician diagnosis. In addition, hypertension was defined as the use of antihypertensive medication, a systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg, or a diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg. Dyslipidemia was defined as the use of lipid-lowering medications or a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level greater than 130 mg/dL or high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level less than 40 mg/dL [17]. Diabetes mellitus (DM) was defined as the use of glucose-lowering medications or a fasting plasma glucose level ≥ 126 mg/dL. Anemia was defined as hemoglobin level < 13 g/dL in men and < 12 g/dL in women [18].

Outcomes

We compared the comorbidity profile by race and ethnicity in subjects with COPD participating in U.S. and Korea NHANES. As comorbidities, we included asthma, hypertension, dyslipidemia, stroke, myocardial infarction, DM, and osteoporosis, which were recommended for screening and management in the Global Initiative for COPD guideline [1], plus anemia, osteoarthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis (RA), three common conditions having a substantial impact on the quality of life.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis used the svy commands in Stata (release 13.1; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) to account for survey weights and for the complex sampling design. For each comorbidity, we calculated its prevalence and 95% confidence interval (CI) by race and ethnicity group and used log binomial regression to estimate adjusted prevalence ratios (aPRs) and 95% CIs comparing each race and ethnicity group to Non-Hispanic Whites, adjusting for age, sex, BMI, and smoking status.

Results

The average age of non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, and Hispanics was similar (59.8, 59.6, and 59.6 years, respectively), but Koreans were older on average (63.6 years, p < 0.001; Table 1). By sex, the proportions of men among non-Hispanic Whites and non-Hispanic Blacks were similar (59.1 and 60.2%, respectively), and lower than among Hispanic (69.2%) and Korean (73.8%) participants. Hispanic participants were the most likely to be overweight or obese (72.6%), while Non-Hispanic Blacks and Koreans were the most likely to be current smokers (42.4 and 41.6%, respectively). By severity, non-Hispanic Blacks had the highest proportion of severe-to-very-severe COPD (9.2%), while Hispanics had the lowest (3.6%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants with COPD aged 40–79 by race and ethnicity, U.S. NHANES 2007–2012 and Korea NHANES 2007–2015a

| U.S. NHANES | Korea NHANES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White (n = 944) | Non-Hispanic Black (n = 324) | Hispanicb (n = 227) | Korean (n = 3808) | p value | |

| Age, years | 59.8(0.4) | 59.6 (0.7) | 59.6 (0.8) | 63.6 (0.2) | < 0.001 |

| Age group, years | < 0.001 | ||||

| 40–49 | 18.7 (1.7) | 20.7 (2.9) | 19.7 (3.1) | 11.3 (0.7) | |

| 50–59 | 31.2 (2.2) | 30.9 (2.6) | 29.9 (3.9) | 23.2 (0.9) | |

| 60–69 | 30.3 (2.4) | 24.1 (1.8) | 32.0 (3.0) | 31.2 (0.9) | |

| 70–79 | 19.8 (1.3) | 24.2 (2.5) | 18.3 (2.7) | 34.3 (1.0) | |

| Men, % | 59.1 (2.4) | 60.2 (2.3) | 69.2 (4.2) | 73.8 (0.9) | < 0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.7 (0.2) | 27.8 (0.4) | 28. 6 (0.4) | 23.7 (0.1) | < 0.001 |

| BMI group | 0.023 | ||||

| Underweight | 1.9 (0.5) | 3.1 (1.2) | 0 | 2.7 (0.4) | |

| Normal | 32.3 (1.6) | 35.1 (2.8) | 27.4 (3.4) | 38.9 (1.1) | |

| Overweight | 37.8 (1.5) | 33.4 (2.3) | 41.9 (3.7) | 27.6 (0.9) | |

| Obese | 27.9 (1.4) | 28.4 (2.6) | 30.7 (3.8) | 30.7 (1.0) | |

| Smoking | < 0.001 | ||||

| Current | 33.5 (2.4) | 42.4 (3.4) | 26.4 (2.8) | 41.6 (1.0) | |

| Former | 39.9 (2.1) | 26.4 (2.2) | 35.5 (2.9) | 27.9 (0.9) | |

| Never | 26.6 (2.1) | 31.3 (2.8) | 38.1 (3.3) | 30.5 (1.0) | |

| Spirometry | |||||

| FVC, % predicted | 96.5 (0.7) | 96.7 (1.1) | 97.9 (1.4) | 90.5 (0.3) | < 0.001 |

| FEV1, % predicted | 80.3 (0.7) | 77.5 (1.1) | 82.6 (1.3) | 77.8 (0.3) | < 0.001 |

| COPD severityc | 0.106 | ||||

| Mild | 52.3 (2.3) | 46.5 (3.1) | 60.4 (4.1) | 46.4 (1.0) | |

| Moderate | 41.3 (2.2) | 44.4 (3.1) | 36.0 (4.3) | 48.7 (1.1) | |

| Severe-to-very severe | 6.4 (0.8) | 9.2 (2.3) | 3.6 (1.1) | 4.9 (0.4) | |

aValues are presented as weighted means (standard error of the mean) or weighted percentage (standard error of the percentage)

bHispanic was defined as Mexican American or other Hispanic

cParticipants were categorized as having mild (FEV1 / FVC < 0.7 and FEV1 ≥ 80% predicted), moderate (FEV1 / FVC < 0.7 and 50% ≤ FEV1 < 80% predicted), or severe-to-very severe (FEV1 / FVC < 0.7 and FEV1 < 50% predicted) disease based on the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease guideline

COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, NHANES National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), BMI body mass index, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 s, FVC forced expiratory vital capacity

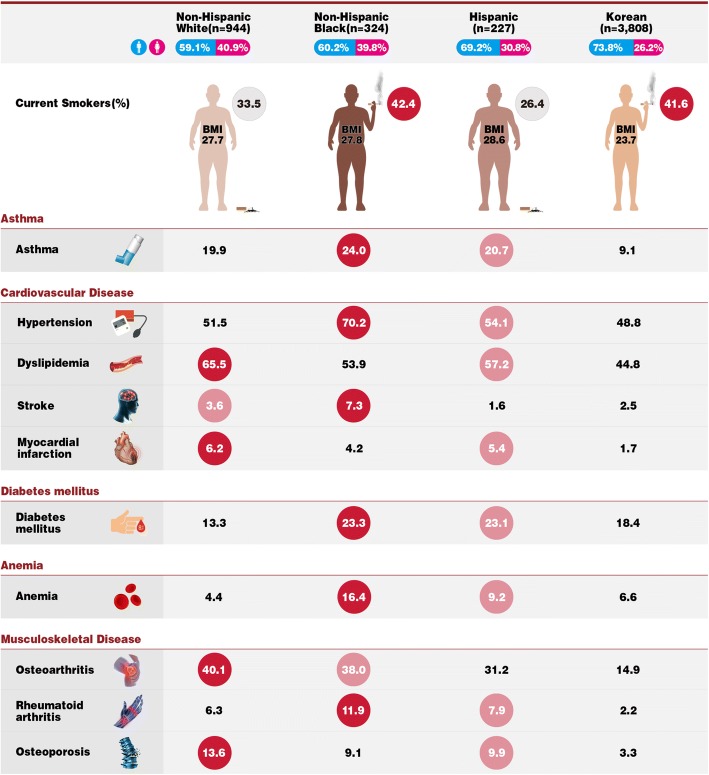

Non-Hispanic White participants had the highest prevalence of dyslipidemia (65.5%), myocardial infarction (6.2%), osteoarthritis (40.1%), and osteoporosis (13.6%), while non-Hispanic Blacks had the highest prevalence of asthma (24.0%), hypertension (70.2%), stroke (7.3%), DM (23.3%), anemia (16.4%), and RA (11.9%) (Table 2 and Fig. 2). Hispanics had very high prevalences of all comorbidities except for stroke, ranking second in the prevalence of asthma, hypertension, myocardial infarction, DM, anemia, RA, and osteoporosis compared to other race and ethnicity groups. Koreans had the lowest prevalence of all comorbidities except for stroke, DM, and anemia.

Table 2.

Prevalence of comorbidities (95% confidence intervals) among participants with COPD aged 40–79 by race and ethnicity, U.S. NHANES 2007–2012 and Korea NHANES 2007–2015

| U.S. NHANES | Korea NHANES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White (n = 944) | Non-Hispanic Black (n = 324) | Hispanica (n = 227) | Korean (n = 3808) | P value | |

| Asthma | 19.9 (16.5 to 23.7) | 24.0 (19.4 to 29.3) | 20.7 (14.3 to 29.0) | 9.1 (8.0 to 10.4) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | |||||

| Hypertension | 51.5 (47.4 to 55.7) | 70.2 (64.0 to 75.6) | 54.1 (46.4 to 61.5) | 48.8 (46.8 to 50.8) | < 0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 65.5 (61.2 to 69.7) | 53.9 (47.3 to 60.3) | 57.2 (48.5 to 65.4) | 44.8 (42.7 to 47.0) | < 0.001 |

| Stroke | 3.6 (2.6 to 4.8) | 7.3 (4.6 to 11.3) | 1.6 (0.5 to 5.3) | 2.5 (2.0 to 3.1) | 0.003 |

| Myocardial infarction | 6.2 (4.7 to 8.1) | 4.2 (2.6 to 6.6) | 5.4 (3.3 to 8.8) | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.3) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 13.3 (10.8 to 16.4) | 23.3 (18.6 to 28.8) | 23.1 (17.5 to 29.7) | 18.4 (16.8 to 20.1) | < 0.001 |

| Anemia | 4.4 (3.0 to 6.3) | 16.4 (12.3 to 21.6) | 9.2 (5.8 to 14.3) | 6.6 (5.7 to 7.6) | < 0.001 |

| Musculoskeletal disease | |||||

| Osteoarthritis | 40.1 (36.4 to 44.0) | 38.0 (33.0 to 43.2) | 31.2 (24.5 to 38.8) | 14.9 (13.5 to 16.5) | < 0.001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 6.3 (4.3 to 9.1) | 11.9 (8.4 to 16.4) | 7.9 (5.2 to 12.0) | 2.2 (1.6 to 2.8) | < 0.001 |

| Osteoporosis | 13.6 (10.9 to 16.9) | 9.1 (6.5 to 12.7) | 9.9 (6.1 to 15.4) | 3.3 (2.7 to 4.1) | < 0.001 |

aHispanic was defined as Mexican American or other Hispanic

COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, NHANES National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of comorbidities among participants with COPD aged 40–79 by race and ethnicity, U.S. NHANES 2007–2012 and Korea NHANES 2007–2015. COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, NHANES National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Compared to non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Black participants had a significantly higher prevalence of hypertension (aPR 1.36, 95% CI 1.23 to 1.51), stroke (aPR 2.01, 95% CI 1.16 to 3.47), DM (aPR 1.76, 95% CI 1.34 to 2.31), anemia (aPR 3.82, 95% CI 2.42 to 6.04), and RA (aPR 1.83, 95% CI, 1.16 to 2.89) after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, and smoking status, while Hispanics had a higher prevalence of DM (aPR 1.64, 95% CI 1.18 to 2.29) and anemia (aPR 2.18, 95% CI 1.23 to 3.86). Koreans had significantly lower prevalences of all comorbidities except stroke, DM, and anemia (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted prevalence ratios and 95% confidence intervals for comorbidities in participants with COPD aged 40–79, U.S. NHANES 2007–2012 and Korea NHANES 2007–2015a

| U.S. NHANES | Korea NHANES | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White (n = 944) | Non-Hispanic Black (n = 324) | Hispanicb (n = 227) | Korean (n = 3808) | |

| Asthma | Reference | 1.23 (0.92 to 1.65) | 1.05 (0.72 to 1.53) | 0.56 (0.43 to 0.72) |

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||

| Hypertension | Reference | 1.36 (1.23 to 1.51) | 1.03 (0.89 to 1.20) | 0.88 (0.81 to 0.95) |

| Dyslipidemia | Reference | 0.83 (0.72 to 0.96) | 0.86 (0.73 to 1.00) | 0.68 (0.63 to 0.73) |

| Stroke | Reference | 2.01 (1.16 to 3.47) | 0.47 (0.14 to 1.61) | 0.69 (0.45 to 1.06) |

| Myocardial infarction | Reference | 0.66 (0.39 to 1.12) | 0.86 (0.49 to 1.53) | 0.21 (0.14 to 0.33) |

| Diabetes mellitus | Reference | 1.76 (1.34 to 2.31) | 1.64 (1.18 to 2.29) | 1.11 (0.90 to 1.38) |

| Anemia | Reference | 3.82 (2.42 to 6.04) | 2.18 (1.23 to 3.86) | 1.31 (0.90 to 1.91) |

| Musculoskeletal disease | ||||

| Osteoarthritis | Reference | 0.95 (0.82 to 1.10) | 0.81 (0.65 to 1.01) | 0.35 (0.30 to 0.40) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Reference | 1.83 (1.16 to 2.89) | 1.40 (0.85 to 2.31) | 0.31 (0.20 to 0.50) |

| Osteoporosis | Reference | 0.68 (0.45 to 1.03) | 0.74 (0.46 to 1.20) | 0.22 (0.16 to 0.32) |

aAdjusted for age, sex, BMI group (underweight, normal, overweight, or obese using World Health Organization criteria for the U.S. population and Asian criteria for the Korean population), and smoking status (current, former, or never)

bHispanic was defined as Mexican American or other Hispanic

COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, NHANES National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Discussion

We found major differences in the comorbidity profile among race and ethnicity groups in subjects with COPD. Non-Hispanic Whites had a comorbidity pattern characterized by dyslipidemia, myocardial infarction, osteoarthritis, and osteoporosis. Non-Hispanic Blacks had a high prevalence of current smokers as well as a high prevalence of multiple comorbidities, especially asthma, hypertension, stroke, DM, anemia, and RA. Hispanics had the highest average BMI levels, as well as high prevalences of asthma and DM. Finally, Koreans had the highest prevalence of current smokers, but lower prevalences of other comorbidities except for stroke, DM, and anemia. Given that coexisting comorbidities have an adverse impact on COPD prognosis, early recognition and management of prevalent disease based on racial differences could reduce the clinical burden of disease in COPD patients.

CVD is a key comorbidity in COPD patients and a major determinant of mortality and functional status [19]. In our study, non-Hispanic Whites had a pattern of CVD comorbidities characterized by a high prevalence of dyslipidemia and coronary disease, while non-Hispanic Blacks had a pattern driven by hypertension, DM, and stroke. These were like the results of a previous study that compared COPD comorbidities between non-Hispanic Whites and non-Hispanic Blacks [20]. In comparison, Hispanics had a pattern driven by obesity and DM. In addition to CVD, asthma is a major comorbidity as well as a risk factor in COPD, complicating treatment and further impairing functional status. Asthma prevalence was particularly high among non-Hispanic Blacks, although non-Hispanics Whites and Hispanics also had a relatively high prevalence. Considering their high prevalence and disease burden, clinicians should consider active screening and management of CVD and asthma in COPD patients.

Anemia has recently been recognized as an independent prognostic predictor of increased hospitalization and mortality in COPD [21–24]. It is also an important comorbidity linked to nutritional deficiency and poor exercise performance among COPD patients [23]. Previous studies have suggested the possibility of improving functional outcomes by correcting anemia [25, 26], and active screening and management of anemia among COPD patients may be beneficial for clinical outcomes, especially among non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics.

Non-Hispanic Blacks had very high prevalences of COPD risk factors and comorbidities. Multiple sources of health disparities and inequalities, including socioeconomic factors, environmental hazards, behavioral factors, and access to health care and preventive services, contribute to the excess burden of disease and mortality among non-Hispanic Blacks in the U.S. [27]. The presence of multiple comorbidities may further complicate management and prognosis in these patients [28, 29]. It may be necessary, however, to develop integrated approaches to prevention and management to reduce the burden of chronic disease-related morbidity and mortality, particularly among non-Hispanic Black subjects with COPD.

Hispanic subjects with COPD had a very high burden of overweight and obesity and DM, although the prevalence of myocardial infarction was lower than in non-Hispanic Whites. The lower prevalence of CVD, despite relatively high levels of metabolic risk factors among Hispanics, has been termed the Hispanic paradox [30], but the reasons for this paradox are controversial. Irrespective of the implications of elevated BMI in Hispanic patients, the high prevalence of overweight and obesity in this group should prompt proper management, as morbid obesity is a risk for poor management and functional decline in COPD [31, 32].

Finally, although Korean COPD patients were older, more likely to be smokers, and more likely to be male than other race or ethnicity groups, they had the lowest prevalences of most comorbidities. A similar pattern has been observed in other Asian countries [33]. In particular, the low prevalence of myocardial infarction in Koreans may reflect lower background rates of the disease due to environmental or genetic factors. Since smoking is a predominant risk factor for COPD among Asians and considering the increasing number of Asians in the U.S., more active surveillance regarding COPD and its comorbidities may be warranted.

Several limitations need to be considered when interpreting our findings. First, we used a cross-sectional study and we do not have information on the timing of the development of each comorbidity. We were, thus, unable to establish causal inferences. Our objective, however, was to compare the comorbidity patterns across race and ethnicity groups, not to identify causal pathways of comorbidities. The different comorbidity patterns may be due to different prevalences of risk factors such as smoking, obesity, socioeconomic status, or environmental exposures, but race and ethnicity may affect the development of comorbidities. Second, we could not evaluate the prevalence of some important COPD-related comorbidities or conditions, such as obstructive sleep apnea or use of long-term oxygen therapy, due to lack of data in either U.S. NHANES or KNHANES. Third, we did not have data that would allow us to evaluate the outcomes of the different comorbidities. This information is important for understanding the impact of the differences in comorbidity profile by race and ethnicity. Given the racial differences in outcomes such as emergency room visits and duration of hospital stays [7], further studies should evaluate the management and outcomes of COPD, including exacerbations and mortality, by comorbidity profile. Fourth, we used data for Koreans as we did not have data for other Asian groups. However, Korean COPD patients had similar overall characteristics as other Asian COPD patients, including Taiwanese, Japanese, or Chinese patients, although the degree of exposure to biomass fuels differed across Asian groups [33].

Conclusions

In our study, COPD-related comorbidities occurred disproportionally according to race and ethnicity, and different strategies may be required for the optimal management of COPD and its comorbidities for different race and ethnicity groups. Furthermore, the generation of local maps of COPD-related comorbidities may help in planning different strategies for the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of COPD and its associated comorbidities.

Acknowledgments

Availability of data and materials

All data extracted in this study are included in this article.

Funding

Not applicable.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- aPR

adjusted prevalence ratio

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- COPD

chronic obstructive lung disease

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- FEV1

forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- FVC

forced vital capacity

- KNHANES

Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

Authors’ contributions

HL, JC, and HYP were responsible for the conception and design of the study. HL, SS, SG, JC, and HYP conducted the experiments and data acquisition. HL, SS, SG, DZ, DK, YRJ, GYS, RP, EG, JC, and HYP undertook the analysis and interpretation of the data. HL, SG, EG, JC, and HYP drafted the manuscript. HL, SS, SG, DZ, DK, YRJ, GYS, RP, EG, JC, and HYP made a critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

As we used publicly available data, our institutions waived the need for ethical approval. The original U.S. NHANES and KNHANES surveys we used were approved by the relevant institutional review boards and all participants provided written, informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

HYP has received lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Boehringer-Ingelheim. HL, SHS, SG, DZ, DK, YRJ, GYS, RP, EG, and JC have no competing interests to declare.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.GOLD. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. (2018 Report) Available from www.goldcopd.org. Assessed 1 June 2018.

- 2.Lopez AD, Shibuya K, Rao C, Mathers CD, Hansell AL, Held LS, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current burden and future projections. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:397–412. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00025805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Projecitons of mortaity and causes of death, 2015 and 2030. Available at: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/projections/en/. Assessed 1 June 2018.

- 4.Vanfleteren LE, Spruit MA, Groenen M, Gaffron S, van Empel VP, Bruijnzeel PL, et al. Clusters of comorbidities based on validated objective measurements and systemic inflammation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:728–735. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201209-1665OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westerik JA, Metting EI, van Boven JF, Tiersma W, Kocks JW, Schermer TR. Associations between chronic comorbidity and exacerbation risk in primary care patients with COPD. Respir Res. 2017;18:31. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0512-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huber MB, Wacker ME, Vogelmeier CF, Leidl R. Comorbid influences on generic health-related quality of life in COPD: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Westney G, Foreman MG, Xu J, Henriques King M, Flenaugh E, Rust G. Impact of comorbidities among Medicaid enrollees with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, United States, 2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:E31. doi: 10.5888/pcd14.160333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sin DD, Anthonisen NR, Soriano JB, Agusti AG. Mortality in COPD: role of comorbidities. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:1245–1257. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00133805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haiman CA, Stram DO, Wilkens LR, Pike MC, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, et al. Ethnic and racial differences in the smoking-related risk of lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:333–342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bahrami H, Kronmal R, Bluemke DA, Olson J, Shea S, Liu K, et al. Differences in the incidence of congestive heart failure by ethnicity: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2138–2145. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.19.2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutierrez J, Williams OA. A decade of racial and ethnic stroke disparities in the United States. Neurology. 2014;82:1080–1082. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lange P, Celli B, Agusti A, Boje Jensen G, Divo M, Faner R, et al. Lung-function trajectories leading to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:111–122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:179–187. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi JK, Paek D, Lee JO. Normal predictive values of spirometry in Korean population. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2005;58:230–242. doi: 10.4046/trd.2005.58.3.230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO . Physical Status: The use and interpretation of anthropometry: report of a World Health Organization (WHO) expert committee. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Force USPST. Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Davidson KW, Epling JW, Jr, et al. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316:1997–2007. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.15450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization . Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of Anaemia and assessment of severity. Vitamin and mineral nutrition information system. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sin DD, Man SF. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:8–11. doi: 10.1513/pats.200404-032MS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Putcha N, Han MK, Martinez CH, Foreman MG, Anzueto AR, Casaburi R, et al. Comorbidities of COPD have a major impact on clinical outcomes, particularly in African Americans. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2014;1:105–114. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.1.1.2014.0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chambellan A, Chailleux E, Similowski T. Prognostic value of the hematocrit in patients with severe COPD receiving long-term oxygen therapy. Chest. 2005;128:1201–1208. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez-Rivera C, Portillo K, Munoz-Ferrer A, Martinez-Ortiz ML, Molins E, Serra P, et al. Anemia is a mortality predictor in hospitalized patients for COPD exacerbation. COPD. 2012;9:243–50. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2011.647131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oh YM, Park JH, Kim EK, Hwang SC, Kim HJ, Kang DR, et al. Anemia as a clinical marker of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the Korean obstructive lung disease cohort. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9:5008–5016. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.10.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park SC, Kim YS, Kang YA, Park EC, Shin CS, Kim DW, et al. Hemoglobin and mortality in patients with COPD: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:1599–1605. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S159249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schonhofer B, Wenzel M, Geibel M, Kohler D. Blood transfusion and lung function in chronically anemic patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:1824–1828. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199811000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silverberg DS, Mor R, Weu MT, Schwartz D, Schwartz IF, Chernin G. Anemia and iron deficiency in COPD patients: prevalence and the effects of correction of the anemia with erythropoiesis stimulating agents and intravenous iron. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;14:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-14-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report — United States, 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/other/su6203.pdf. Accessed 1 June 2018. [PubMed]

- 28.Decramer M, Janssens W. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and comorbidities. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:73–83. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(12)70060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hillas G, Perlikos F, Tsiligianni I, Tzanakis N. Managing comorbidities in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:95–109. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S54473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodriguez CJ, Allison M, Daviglus ML, Isasi CR, Keller C, Leira EC, et al. Status of cardiovascular disease and stroke in Hispanics/Latinos in the United States: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;130:593–625. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Donnell DE, Ciavaglia CE, Neder JA. When obesity and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease collide. Physiological and clinical consequences. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:635–644. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201312-438FR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katz P, Iribarren C, Sanchez G, Blanc PD. Obesity and functioning among individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) COPD. 2016;13:352–359. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2015.1087991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oh YM, Bhome AB, Boonsawat W, Gunasekera KD, Madegedara D, Idolor L, et al. Characteristics of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in the pulmonology clinics of seven Asian cities. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2013;8:31–39. doi: 10.2147/copd.s36283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data extracted in this study are included in this article.