Abstract

Background

The process for evaluating kidney transplant candidates and applicable centers is distinct for patients with Veterans Administration (VA) coverage. We compared transplant rates between candidates on the kidney waiting list with VA coverage and those with other primary insurance.

Methods

Using the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients database, we obtained data for all adult patients in the United States listed for a primary solitary kidney transplant between January 2004 and August 2016. Of 302,457 patients analyzed, 3663 had VA primary insurance coverage.

Results

VA patients had a much greater median distance to their transplant center than those with other insurance had (282 versus 22 miles). In an adjusted Cox model, compared with private pay and Medicare patients, VA patients had a hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) for time to transplant of 0.72 (0.68 to 0.76) and 0.85 (0.81 to 0.90), respectively, and lower rates for living and deceased donor transplants. In a model comparing VA transplant rates with rates from four local non-VA competing centers in the same donor service areas, lower transplant rates for VA patients than for privately insured patients persisted (hazard ratio, 0.72; 95% confidence interval, 0.65 to 0.79) despite similar adjusted mortality rates. Transplant rates for VA patients were similar to those of Medicare patients locally, although Medicare patients were more likely to die or be delisted after waitlist placement.

Conclusions

After successful listing, VA kidney transplant candidates appear to have persistent barriers to transplant. Further contemporary analyses are needed to account for variables that contribute to such differential transplant rates.

Keywords: kidney transplantation, cadaver organ transplantation, transplant outcomes

United States veterans have a higher prevalence of kidney disease compared with the general population, likely related to high rates of diabetes and hypertension.1 Kidney transplantation remains the ideal treatment for qualifying veterans with advanced kidney disease. Approximately 40% of United States veterans are enrolled in Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals. However, among veterans who received kidney transplants, only approximately 15% utilized VA transplant centers.2 Kidney transplant outcomes in VA patients relative to the general population have historically been comparable,3,4 and VA patients benefit from universal coverage of immunosuppressive therapy, with low or absent copays after transplantation. The high cost of immunosuppressive medications has been shown to be a deterrent to transplantation in the general population,5 and VA benefits may help to eliminate this barrier.

Still, concerns remain that because of potential distance and infrastructural constraints, veterans may continue to have limited access to kidney transplantation through VA centers. Since 2010, transplant approval has been streamlined in the VA system by an online referral program and elimination of a central approval process. Furthermore, there has been the addition of three VA kidney transplant centers in recent years. However, efforts to further expand transplant programs for veterans have been met with resistance in some cases,6 and despite expansion, there remain only seven VA kidney transplant programs nationally, with lower than expected rates of transplantation overall (https://www.srtr.org/).

A previous analysis found that VA patients who developed ESRD between 1995 and 2004 had less access to kidney transplantation compared with patients with private insurance.7 The majority of the difference in transplant access was related to a relatively lower rate of listing for transplantation in VA patients. Here, we analyzed patients from a more recent era, focusing on those who were already listed for transplantation at VA centers. We compared time to transplantation between VA and non-VA patients covered by private, Medicare, and Medicaid insurance. We hypothesized that transplantation may be delayed even in patients who were successfully listed in VA centers. Because deceased donor transplant rates can vary greatly by region,8 we further sought to compare four primary VA transplant centers with their four competing non-VA transplant centers in the same donor service areas (DSAs). Organ offers are shared between these groups, and waiting times within these DSAs would be expected to be similar, allowing for a direct comparison of transplant rates between VA and local non-VA centers.

Methods

Patient Population

Data were obtained from the Scientific Registry of Organ Transplantation (SRTR) database, with approval from the Institutional Review Board at Cleveland Clinic. The SRTR data system includes data on all donor, waitlisted candidates, and transplant recipients in the United States, submitted by the members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, and has been described elsewhere.9

Patients aged ≥18 years and listed for a primary solitary kidney transplant between January 2004 and August 2016 were included. The first listing date was included if patients had multiple listings, and patients were included if they had primary insurance listed as VA, private, Medicare, or Medicaid. Some patients were noted to have secondary insurance, although 92% of VA patients had no secondary insurance listed at the time of initial listing (Supplemental Table 1). Because VA primary insurance would only be accepted at VA transplant centers, we used the insurance type as a surrogate for VA transplant center listing. Patients were excluded from analysis if they had no listing date or lacked insurance information.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was time from listing to kidney transplantation, censored for mortality. Secondary outcomes included time from listing to living donor transplantation (excluding deceased donor transplants), time to deceased donor transplantation (excluding living donor transplants), time to death (censored at transplant), and time to delisting. Delisting was only considered when coded reasons were related to “health deterioration” or “other,” to capture patient delisting for reasons other than transplantation or death.

VA versus Matched Local Centers

We selected four primary VA transplant centers with their four competing non-VA academic transplant centers in the same DSAs. Because of the small number of transplants performed in the three newest VA kidney transplant centers, those additional centers were not included. To be selected for this subset, patients listed in the non-VA centers required private or Medicare insurance, whereas patients listed in the VA centers had VA insurance.

Statistical Analyses

We compared candidate characteristics across the following primary insurance groups: VA, private, Medicare, and Medicaid. We used chi-squared tests to compare categorical variables and ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis tests for continuous variables. We estimated and plotted cumulative incidence functions to evaluate time to transplant, with death as a competing risk across groups. We used Cox models to evaluate the association between insurance group and transplantation and adjusted for age group, race, sex, diagnosis group, time on dialysis at listing, candidate status at listing, panel reactive antibody (PRA), body mass index group, education, malignancy, peripheral vascular disease, year of listing, region, log distance from candidate residence to listing center (distance in miles transformed on a log-10 scale), and community risk score. We tested an interaction between log-transformed distance to center and insurance type. The community risk score was derived from zip code data, with scoring on the basis of ten variables, as previously described.10 For patients missing distance and community risk score, we used mean value imputation with an indicator for missing data. We fit similar models for deceased donor transplantation (excluding live donors), for living donor transplantation (excluding deceased donors), for mortality, and for delisting due to health deterioration or other causes. Because a higher percentage of VA patients were missing data on education level, we performed a sensitivity analysis on the Cox models excluding patients that lacked education information. Because kidney allocation rates may have changed after the implementation of the Kidney Allocation System (KAS), we performed a second sensitivity analysis censoring data on December 4, 2014 (date of KAS change). We also fit competing risks regression models to evaluate the association between insurance group and transplant and accounted for the competing risk of death. Finally, we analyzed the association between insurance and transplantation, mortality, and delisting in the four major VA transplant centers and their four local non-VA competitors for the same time period. We compared candidate characteristics across the primary insurance groups within the four matched centers, and also compared patients in the four VA centers plus their matched counterparts to all other patients nationally.

All data analyses were conducted using Linux SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Graphs were produced using R 3.3.2 (the R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and the cmprsk package.

Results

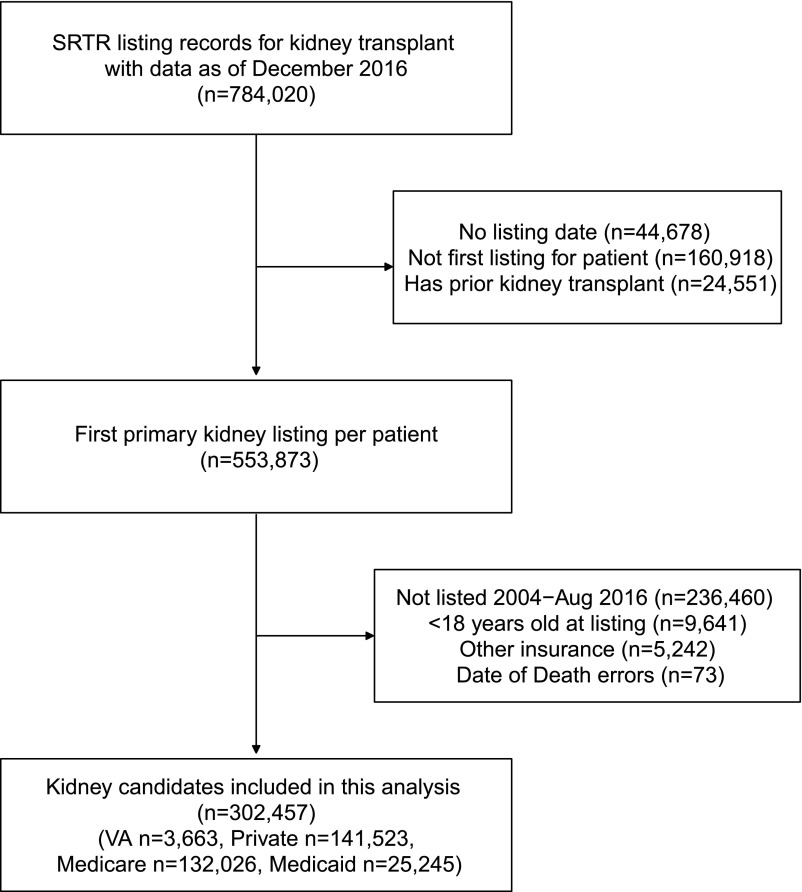

A total of 302,457 patients were included in the final study population. A flow chart showing patient inclusion and exclusion is shown in Figure 1. Of those excluded, 11,604 received a living donor kidney transplant without being listed. Of those, 62% had private insurance, compared with 47% with private insurance in the study cohort. VA insurance was conversely found in 0.4% of those with a living donor transplant without listing, compared with 1.2% of patients included in the study group.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient inclusion/exclusion.

Demographic data overall and stratified by VA, private, Medicare, or Medicaid insurance are shown in Table 1. VA patients were older and much more likely to be men, with a higher percentage of black patients. VA patients also had higher proportion of diabetes as a cause of ESRD, obesity, and malignancy. Other characteristics, including vascular disease, education, willingness to accept a hepatitis C-positive donor kidney, community risk score, and dialysis vintage were variable between insurance groups (Table 1). VA patients were less likely to be listed initially as inactive compared with other groups, and had a lower proportion of HLA antibody sensitization by PRA testing. The percentage of VA patients listed was noted to be increasing in recent years. The median distance from VA patients to their transplant center was over ten-fold greater than the distance for other insurance types (median 282 versus 22 miles), and over a quarter of VA patients traveled >500 miles to the VA transplant center. Finally, for transplanted patients, VA patients were more likely to be transplanted in a center other than the primary listing center and had higher rates of multicenter listing compared with Medicare and Medicaid (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic variables for VA patients compared with patients with other insurance nationally

| Variable | Overall, n=302,457 | VA, n=3663 | Private, n=141,523 | Medicare, n=132,026 | Medicaid, n=25,245 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 52.4±12.9 | 57.5±9.8 | 51.1±11.9 | 54.9±13.3 | 45.9±13.7 | <0.001a |

| Men | 61.3% | 92.2% | 61.6% | 61.2% | 55.2% | <0.001b |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001b | |||||

| White | 45.0% | 51.7% | 53.0% | 40.1% | 24.9% | |

| Black | 29.0% | 36.9% | 24.4% | 33.2% | 31.8% | |

| Hispanic | 17.4% | 7.3% | 13.4% | 19.5% | 30.7% | |

| Other | 8.5% | 4.1% | 9.2% | 7.1% | 12.6% | |

| Diagnosis of ESRD | <0.001b | |||||

| Diabetes | 35.5% | 41.8% | 31.4% | 40.1% | 33.3% | |

| Hypertension | 21.7% | 16.7% | 18.2% | 25.2% | 23.5% | |

| GN | 16.9% | 16.5% | 20.8% | 12.8% | 16.9% | |

| Polycystic | 7.4% | 8.3% | 10.8% | 4.4% | 4.4% | |

| Other | 18.5% | 16.6% | 18.9% | 17.4% | 22.0% | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 5.9% | 5.4% | 4.5% | 7.6% | 5.1% | <0.001b |

| Malignancy | 6.1% | 9.9% | 5.6% | 7.1% | 2.7% | <0.001b |

| Serum albumin | 3.9±0.6 | 3.8±0.5 | 3.9±0.6 | 3.9±0.6 | 3.8±0.7 | <0.001a |

| Education | <0.001b | |||||

| Unknown | 7.6% | 32.1% | 7.4% | 7.1% | 8.5% | |

| High school or less | 47.4% | 24.3% | 37.9% | 54.8% | 65.9% | |

| Some college or more | 44.9% | 43.6% | 54.8% | 38.1% | 25.6% | |

| Dialysis vintage, mo | <0.001b | |||||

| 0 | 30.9% | 31.0% | 44.9% | 16.9% | 25.7% | |

| 1–12 | 32.4% | 23.9% | 33.9% | 29.9% | 37.7% | |

| 13–24 | 18% | 21.5% | 13.5% | 23.0% | 16.5% | |

| 25–36 | 7.7% | 11.2% | 4.6% | 11.1% | 7.3% | |

| >36 | 11.0% | 12.3% | 3.1% | 19.1% | 12.8% | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | <0.001b | |||||

| ≤25 | 27.1% | 19.8% | 26.2% | 26.8% | 34.6% | |

| 26–30 | 33.0% | 36.5% | 32.6% | 33.6% | 31.0% | |

| 31–35 | 24.4% | 32.2% | 25.0% | 24.4% | 20.2% | |

| >35 | 14.3% | 11.2% | 14.9% | 14.1% | 12.9% | |

| Listed inactive | 26.8% | 13.0% | 26.9% | 26.5% | 30.1% | <0.001b |

| Any inactive status | 59.6% | 52.2% | 54.6% | 59.1% | 59.1% | <0.001 |

| Listing era | <0.001b | |||||

| 2004–2007 | 28.2% | 20.1% | 29.0% | 27.6% | 28.6% | |

| 2008–2011 | 32.2% | 31.8% | 32.2% | 32.9% | 29.6% | |

| 2012–2016 | 39.5% | 48.2% | 38.9% | 39.5% | 41.7% | |

| Panel reactive antibody >0% | 16.0% | 8.4% | 15.6% | 16.6% | 16.3% | <0.001b |

| Median distance to transplant center, miles (25%, 75%) | 22.4 (8.9, 65.8) | 281.9 (122.8, 596.9) | 22.7 (9.9, 60.7) | 23.0 (8.4, 69.8) | 13.8 (5.5, 48.6) | <0.001c |

| Transplanted in a center different from primary listing (for those transplanted) | 11.8% | 13.3% | 12.9% | 10.5% | 10.5% | <0.001b |

| Multilisting before removal from list for transplant, death, or other | 5.4% | 6.5% | 6.5% | 4.6% | 3.0% | <0.001b |

| Accept a hepatitis C-positive donor? | 3.1% | 4.4% | 2.9% | 3.2% | 3.5% | <0.001b |

| Community risk score | 19.9±10.2 | 21.4±9.9 | 18.8±10.2 | 21.1±10.0 | 19.5±10.4 | <0.001a |

| Community risk score quintiles | <0.001b | |||||

| 1 | 20.3% | 15.4% | 23.9% | 15.9% | 22.9% | |

| 2 | 19.6% | 17.2% | 20.5% | 18.7% | 19.9% | |

| 3 | 18.8% | 21.0% | 18.3% | 19.9% | 15.8% | |

| 4 | 21.8% | 21.8% | 20.3% | 23.1% | 23.7% | |

| 5 | 19.5% | 24.6% | 17.0% | 22.3% | 17.7% |

Statistics presented as means±SD or percentages unless otherwise indicated.

ANOVA P value.

Pearson chi-squared test P value.

Kruskal–Wallis test P value.

Table 2 shows a multivariable Cox regression analysis comparing transplantation, mortality, and delisting for patients with VA insurance versus other insurance groups nationally. Compared with privately insured patients, the overall hazard ratio (HR) for transplantation in VA patients was 0.72 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.68 to 0.76). The ratio for living donor transplantation was particularly low (HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.46 to 0.57), but after excluding live donor transplant recipients, there remained a reduced ratio for deceased donor transplantation (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.80 to 0.90). VA patients also had a lower HR for transplantation versus Medicare patients, nationally (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.81 to 0.90) (Table 2). There was no difference found between VA patients and Medicaid patients. All results were found to be similar, using a model with death as a competing risk (Supplemental Table 2). Sensitivity analyses excluding patients who were missing education information were similar to the main Cox analysis (Supplemental Table 3A). Sensitivity analyses censoring the study on December 4, 2014 (date of the KAS implementation) were also similar to the main Cox analysis (Supplemental Table 3B).

Table 2.

Adjusted hazard ratios for transplantation, mortality and delisting in VA patients compared to other insurance groups nationally

| Insurance Group | All Transplants | Deceased Donor Transplant | Living Donor Transplant | Death | Delistinga |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VA versus private | 0.72 (0.68, 0.76)b | 0.85 (0.80, 0.90)b | 0.51 (0.46, 0.57)b | 0.89 (0.82, 0.97)b | 1.38 (1.26, 1.51)b |

| VA versus Medicare | 0.85 (0.81, 0.90)b | 0.91 (0.85, 0.96)b | 0.77 (0.69, 0.86)b | 0.77 (0.71, 0.84)b | 1.10 (1.001, 1.20)b |

| VA versus Medicaid | 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) | 1.01 (0.95, 1.08) | 1.00 (0.89, 1.12) | 0.76 (0.70, 0.83)b | 1.04 (0.95, 1.15) |

Models adjusted for age group, race, sex, diagnosis group, time on dialysis at listing, candidate status at listing, panel reactive antibody, body mass index group, education, malignancy, peripheral vascular disease, region, year of listing, log distance to center, and community risk score. Model of deceased donor transplant excludes live donor transplants. Model of living donor transplant excludes deceased donor transplants.

Delisting for reasons of “health deterioration” or “other.”

P<0.05

We found an interaction between log distance to candidate center and insurance (Supplemental Table 4). For patients with private insurance, greater distance to the transplant center was associated with increased transplantation overall and increased living donor transplantation. For patients with Medicare insurance, greater distance was associated with less deceased donor transplantation but increased living donor transplantation. For patients with VA insurance, distance to the center was not significantly associated with transplantation. For all groups except VA, greater distance to the transplant center was associated with greater patient mortality.

The unadjusted estimated cumulative incidence of mortality, using transplant as a competing risk, for VA patients at 2 years was 7.0 (95% CI, 6.1 to 7.9) compared with 5.8 (95% CI, 5.6 to 5.9) for private insurance, 9.1 (95% CI: 8.9, 9.3) for Medicare patients, and 8.1 (95% CI: 7.8, 8.5) for Medicaid patients. The adjusted HRs for mortality are shown in Table 2 and in this model, VA patients had less mortality versus patients with private insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid. VA patients were also more likely to be delisted for health deterioration or other criteria compared with privately insured and Medicare patients nationally (Table 2).

Next, four primary VA transplant centers were compared with four local non-VA competitors. Because of limited number of Medicaid patients within these four centers, Medicaid patients were excluded from this analysis. Demographic data stratified by primary insurance in these eight centers are shown in Table 3. Again, VA patients were older, predominantly men, had a higher percentage of black patients, and a higher proportion of diabetic kidney disease. VA patients had lower PRA and a much greater median distance to the transplant center in this cohort. In this local comparison, VA patients had a lower community risk score compared with other groups. VA patients were more likely to be multilisted before removal from the waiting list, and among patients ultimately transplanted, VA patients were more likely to undergo transplant in a center other than the primary listing center (Table 3). The four VA centers and their matched non-VA counterparts were also compared with all other national data (Supplemental Table 5).

Table 3.

Demographic variables for VA patients compared with patients with other insurance at four local non-VA competing centers

| Variable | Overall (n=9765) | VA (n=2905) | Private (n=3751) | Medicare (n=3109) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 54.7±12.5 | 57.9±9.4 | 51.2±12.5 | 55.7±14.1 | <0.001a |

| Men | 71.4% | 96.3% | 60.6% | 61.0% | <0.001b |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001b | ||||

| White | 67.0% | 53.5% | 76.1% | 68.8% | |

| Black | 25.4% | 36.5% | 18.0% | 24.1% | |

| Hispanic | 4.0% | 6.4% | 2.2% | 4.0% | |

| Other | 3.5% | 3.6% | 3.8% | 3.1% | |

| Diagnosis of ESRD | <0.001b | ||||

| Diabetes | 35.6% | 45.1% | 27.9% | 35.8% | |

| Hypertension | 16.9% | 17.3% | 15.2% | 18.6% | |

| GN | 17.4% | 16.5% | 20.6% | 14.5% | |

| Polycystic | 8.9% | 7.9% | 12.1% | 5.9% | |

| Other | 21.2% | 13.2% | 24.2% | 25.2% | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 3.8% | 5.6% | 2.2% | 4.0% | <0.001b |

| Malignancy | 8.7% | 10.2% | 6.2% | 10.2% | <0.001b |

| Serum albumin | 3.9±0.5 | 3.9±0.5 | 3.9±0.6 | 3.9±0.6 | <0.001a |

| Education | <0.001b | ||||

| Unknown | 13.6% | 38.8% | 3.1% | 2.9% | |

| High school or less | 37.8% | 21.8% | 38.6% | 51.7% | |

| Some college or more | 48.6% | 39.4% | 58.3% | 45.4% | |

| Dialysis vintage, mo | <0.001b | ||||

| 0 | 30.4% | 27.9% | 41.8% | 18.9% | |

| 1–12 | 29.4% | 22.8% | 34.5% | 29.3% | |

| 13–24 | 20.2% | 23.3% | 15.1% | 23.4% | |

| 25–36 | 9.2% | 12.6% | 5.1% | 11.0% | |

| >36 | 10.8% | 13.4% | 3.5% | 17.5% | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | <0.001b | ||||

| ≤25 | 23.8% | 19.5% | 25.8% | 25.4% | |

| 26–30 | 33.4% | 37.2% | 32.0% | 31.6% | |

| 31–35 | 27.0% | 32.7% | 24.5% | 24.9% | |

| >35 | 15.1% | 10.6% | 16.9% | 17.4% | |

| Listed inactive | 9.7% | 9.7% | 10.7% | 8.5% | <0.001b |

| Any inactive status | 56.3% | 51.7% | 54.6% | 62.6% | <0.001 |

| Listing era | <0.001b | ||||

| 2004–2007 | 22.5% | 20.0% | 26.6% | 19.0% | |

| 2008–2011 | 33.9% | 34.8% | 34.0% | 32.8% | |

| 2012–2016 | 43.9% | 45.0% | 39.4% | 48.1% | |

| Panel reactive antibody >0% | 14.3% | 8.2% | 18.6% | 14.9% | <0.001b |

| Median distance to transplant center, miles (25%, 75%) | 81.6 (23.9, 210.2) | 347.0 (196.9, 701.8) | 42.5 (12.9, 101.1) | 55.6 (16.4, 102.6) | <0.001c |

| Transplanted in a center different from primary listing (for those transplanted) | 9.0% | 13.6% | 7.3% | 7.5% | <0.001b |

| Multilisting before removal from the list for transplant, death, or other | 4.8% | 6.9% | 4.8% | 2.8% | <0.001b |

| Accept a hepatitis C-positive donor? | 5.2% | 4.4% | 6.0% | 5.2% | 0.01b |

| Community risk score | 23.6±9.7 | 21.4±10.1 | 24.0±9.5 | 25.1±9.3 | <0.001a |

| Community risk score quintiles | <0.001b | ||||

| 1 | 11.1% | 16.0% | 10.1% | 7.9% | |

| 2 | 14.7% | 18.1% | 13.7% | 12.8% | |

| 3 | 8.8% | 18.3% | 4.7% | 5.0% | |

| 4 | 36.3% | 22.1% | 43.2% | 41.0% | |

| 5 | 29.0% | 25.5% | 28.3% | 33.2% |

Statistics presented as means±SD or percentages unless otherwise indicated.

ANOVA P value.

Pearson chi-squared test P value.

Kruskal–Wallis test P value.

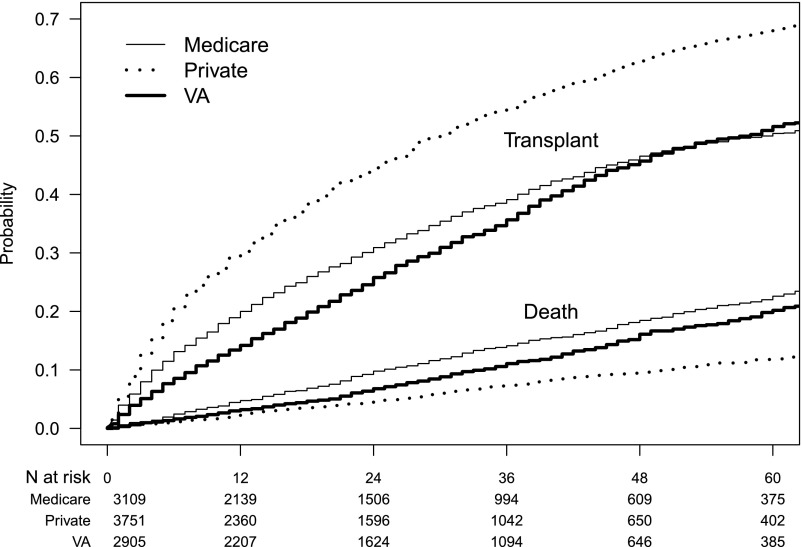

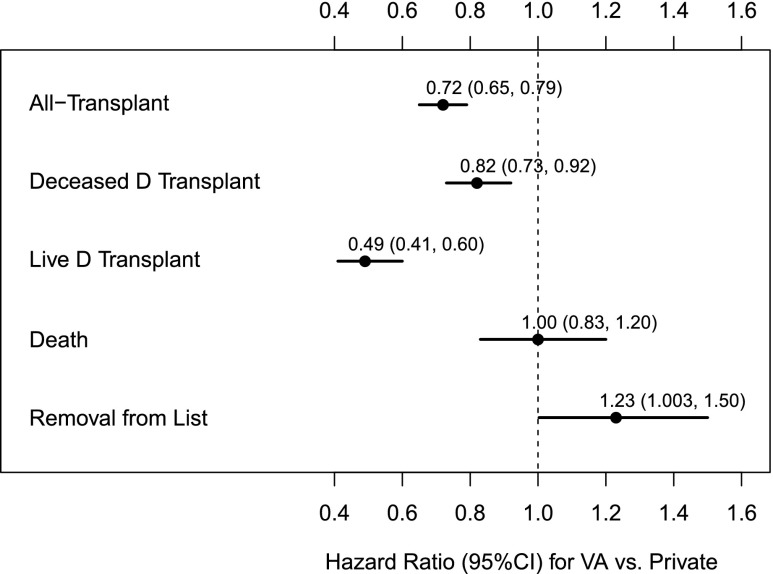

Unadjusted cumulative incidence transplant and mortality curves between patients with VA, private, and Medicare insurance in the four matched centers are shown in Figure 2. VA patients had a delay in transplantation compared with Medicare patients, with a later crossover period. By adjusted analysis, compared with privately insured, VA patients had a lower HR for transplantation overall (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.65 to 0.79), for living donor (HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.41 to 0.69), and for deceased donor transplants (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.73 to 0.92). Figure 3 shows the comparison between the four VA centers and patients with private insurance in the four competing centers. Transplantation was lower among VA patients compared with those with private insurance, whereas adjusted mortality rates were similar, and rates of delisting were higher in VA patients. The HR for transplantation in VA patients compared with Medicare patients were similar overall and for deceased donor in the four competing centers, but lower for living donor transplant (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.64 to 0.97). The adjusted mortality HR remained lower in VA patients compared with Medicare patients (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.68 to 0.96), and VA patients were also less likely to be removed from the waiting list versus local Medicare patients (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.68 to 0.99). Data were similar in a model controlling for death as a competing risk (Supplemental Table 6), Sensitivity analyses excluding patients missing education information were similar to the main Cox analysis (Supplemental Table 7A). Sensitivity analyses censoring data on December 4, 2014 (date of KAS change) were also similar to the main Cox analysis (Supplemental Table 7B).

Figure 2.

Time to transplantation or death in VA patients versus patients with private or Medicare insurance at four local competing non-VA centers.

Figure 3.

HRs (95% CIs) for transplantation, death, and removal from the waiting list in VA patients versus patients with private insurance from four local non-VA centers. D, donor.

Discussion

In this analysis of kidney transplant waiting times, we found that patients successfully listed with VA primary insurance had a lower adjusted rate of transplantation nationally compared with patients with private and Medicare insurance, with lower for both living and deceased donor transplant. Rates were similar to those seen in Medicaid patients, who are known to be disadvantaged in terms of access to kidney transplantation.11 In a second analysis comparing four VA transplant centers to four local competing centers, VA patients had a lower rate of transplantation that persisted compared with patients with private insurance. Adjusted rates of living donation were lower compared with Medicare patients, whereas patient mortality and rates of waitlist removal were higher in Medicare versus VA patients, suggesting that VA patients had greater stability on the list compared with local Medicare patients. We found that the community risk score was lower in listed VA patients compared with other insurance groups in the local four-center comparison, but this advantage did not translate into higher transplant rates.

Gill et al.7 had previously analyzed transplant rates in patients with ESRD aged 18–70 years from an earlier era, and found lower rates in patients with VA coverage compared with those with private insurance. Differences in that study were primarily related to lower rates of listing for transplantation, although an examination of patients on the waiting list did reveal a lower relative transplant rate as well (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.82 to 0.96). The study herein focused on transplant rates in listed VA patients from a more recent era. Despite demonstrating an ability to travel and being deemed medically acceptable for transplantation, VA patients continue to lag behind other groups in non-VA centers.

It is unclear what factors might be driving differences in transplant rates between VA patients and others. VA patients had less alloantibody sensitization at the time of listing and were less likely to be listed in an inactive status, which should have favored more timely transplantation.9 An analysis of non-VA United States transplant candidates found that greater distance from the transplant center predicted a lower rate of deceased donor transplantation.12 We found a more than ten-fold increase in the mean distance from a patient’s zip code to the nearest VA transplant center compared with patient distance to non-VA centers. However, surprisingly, we did not find the distance to the transplant center to be associated with transplant rates or mortality within the VA population. Transportation is provided by VA centers,13 and such travel assistance may help to offset the barriers related to distance to the transplant center.

Distance from the transplant center may rather have an effect on initial transplant evaluation and listing. An analysis of a subset of VA kidney transplant recipients from an earlier era found that only 6% received transplants from a VA center, whereas the majority utilized Medicare coverage in non-VA facilities.14 Patients were less likely to utilize the VA if they lived outside of the local VA transplant center area. A study in liver transplantation found that greater distance from a VA transplant center was associated with a lower rate of listing and a greater risk of death related to decompensated liver disease.15 Finally, VA hospital utilization overall has been shown to vary inversely with travel distance.16

A recent analysis looked at various factors related to the time from evaluation at a VA transplant center to successful listing.17 That study did not account for the barriers and delays that may occur before evaluation at the transplant center. VA transplant centers may turn a patient down sight-unseen or request additional testing that may delay evaluation. Transplant centers may also deny a patient from visiting the transplant facility if the patient lacks an accompanying social support person. Among the selected patients who were evaluated at VA transplant centers from the study above, 30% were not listed.17

Once listed, living donor transplantation is the best option for all kidney transplant candidates, and our data show that the rate of living donation was particularly low in the VA transplant population compared with privately insured patients. In the study above, 41% of surveyed patients evaluated at VA transplant centers reported having a living donor candidate available.17 However, living donor transplantation makes up <10% of transplants overall in VA centers. Barriers to living donation may exist within the VA system. Living donors may initiate an evaluation only after recipient listing, which may contribute to a low 1.1% rate of preemptive transplantation.18 In addition, a social support person cannot serve as a living donor. For example, a spouse very often serves as social support but cannot serve as a donor unless additional support people are available for both parties.

In previous eras it appeared that the majority of eligible VA patients sought kidney transplant listing locally, utilizing Medicare or other coverage. However, the utilization of VA kidney transplant centers is increasing, as witnessed by a growing rate of listing at VA centers. This may relate to a lower rate of Medicare acquisition in VA patients in the current era. VA outsourcing to non-VA dialysis centers has grown in recent years.1,19 This “fee-based” care allows VA patients to pursue dialysis treatments locally without incurring the cost of Medicare coverage. However, lack of Medicare at the time of transplant evaluation makes listing at a VA center the only option for many veterans.

Currently, with only 71 VA dialysis centers in the country, thousands of VA patients are outsourced to private dialysis facilities every year.18 There has been an effort to increase dialysis care at the VA, with the recent addition of free-standing outpatient VA dialysis centers.20 Increasing dialysis care within the VA system appears feasible and may improve patient care.18 In terms of transplantation, there has been expansion within the VA system, with the addition of three kidney transplant centers in recent years. Such an expansion of resources for transplantation may benefit veterans, as kidney transplantation is more cost-effective with improvement in quality of life compared with maintenance dialysis therapy.21 VA patients have affordable access to immunosuppressive drugs with outstanding pharmaceutical services after kidney transplantation,22 regardless of where they are transplanted.

This study has some limitations. As a retrospective analysis, we describe associations that may not be causal, and certain variables may be missing from the SRTR database that may contribute to different rates of kidney transplantation between groups. We did attempt to control for multiple variables, but were lacking in certain data points such as smoking and ischemic heart disease. We chose to study patients who had been successfully listed for transplantation by VA and non-VA transplant centers to define a healthier and more homogeneous population for whom transplantation was deemed appropriate. We also controlled for patient death as an alternative endpoint to transplantation. It is likely that some VA patients utilized non-VA coverage to obtain a transplant elsewhere, as noted by a higher rate of transplantation in VA patients outside of their primary listing center. However, such a practice should have increased the rate of transplantation in VA patients. Finally, we cannot make any firm conclusions as to why transplant rates differed between groups, and further study is required to compare patient availability, surgeon and operating room availability, and kidney allograft turn-down rates between VA and non-VA centers.

In summary, results indicated that despite successful listing for a primary solitary kidney transplant, VA patients had a reduced adjusted rate of kidney transplantation compared with patients with private insurance and Medicare nationally. Comparing four VA centers with four local non-VA competing centers revealed a persistent reduction in transplant rates compared with privately insured patients. Despite stability on the waiting list, travel benefits, and excellent medical coverage, VA kidney transplant candidates may have barriers to transplantation. Further studies are needed to identify the reasons for such barriers and to evaluate potential interventions. Specifically, identifying more specific patient characteristics, system-level factors, and institutional practice patterns that are associated with access to transplantation for VA patients are needed to define sources of differences in transplant rates.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

J.J.A. was responsible for study concept and design, interpretation of data, and writing of the manuscript. S.A. was responsible for data acquisition and analysis, writing and revising of the manuscript. K.B. was responsible for editing and revising the manuscript. N.D. was responsible for study concept and design, editing and revising the manuscript. J.D.S. was responsible for study concept and design, interpretation of data, editing and revising the manuscript.

This study had no external financial support.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related article, “Kidney Transplantation Rates of Veterans Administration–Listed Patients Compared with Rates of Patients on Nonveteran Lists,” on pages 2449–2450.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2017111204/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Wang V, Maciejewski ML, Patel UD, Stechuchak KM, Hynes DM, Weinberger M: Comparison of outcomes for veterans receiving dialysis care from VA and non-VA providers. BMC Health Serv Res 13: 26, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pullen LC: Transplantation remains daunting for many veterans. Am J Transplant 17: 1–2, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore D, Feurer I, Speroff T, Shaffer D, Nylander W, Kizilisik T, et al.: Survival and quality of life after organ transplantation in veterans and nonveterans. Am J Surg 186: 476–480, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chakkera HA, O’Hare AM, Johansen KL, Hynes D, Stroupe K, Colin PM, et al.: Influence of race on kidney transplant outcomes within and outside the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 269–277, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dageforde LA, Box A, Feurer ID, Cavanaugh KL: Understanding patient barriers to kidney transplant evaluation. Transplantation 99: 1463–1469, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pondrom S: The AJT report. Am J Transplant 14: 1951–1952, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gill JS, Hussain S, Rose C, Hariharan S, Tonelli M: Access to kidney transplantation among patients insured by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2592–2599, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vranic GM, Ma JZ, Keith DS: The role of minority geographic distribution in waiting time for deceased donor kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant 14: 2526–2534, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grams ME, Massie AB, Schold JD, Chen BP, Segev DL: Trends in the inactive kidney transplant waitlist and implications for candidate survival. Am J Transplant 13: 1012–1018, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schold JD, Heaphy EL, Buccini LD, Poggio ED, Srinivas TR, Goldfarb DA, et al.: Prominent impact of community risk factors on kidney transplant candidate processes and outcomes. Am J Transplant 13: 2374–2383, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurella-Tamura M, Goldstein BA, Hall YN, Mitani AA, Winkelmayer WC: State medicaid coverage, ESRD incidence, and access to care. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 1321–1329, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Axelrod DA, Dzebisashvili N, Schnitzler MA, Salvalaggio PR, Segev DL, Gentry SE, et al.: The interplay of socioeconomic status, distance to center, and interdonor service area travel on kidney transplant access and outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 2276–2288, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Department of Veterans Affairs : Beneficiary travel under 38 U.S.C. 111 within the Unites. Final rule. Fed Regist 73: 36796–36802, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weeks WB, West AN: Where do veterans health administration patients obtain heart, liver, and kidney transplants? Mil Med 172: 1154–1159, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg DS, French B, Forde KA, Groeneveld PW, Bittermann T, Backus L, et al.: Association of distance from a transplant center with access to waitlist placement, receipt of liver transplantation, and survival among US veterans. JAMA 311: 1234–1243, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mooney C, Zwanziger J, Phibbs CS, Schmitt S: Is travel distance a barrier to veterans’ use of VA hospitals for medical surgical care? Soc Sci Med 50: 1743–1755, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freeman MA, Pleis JR, Bornemann KR, Croswell E, Dew MA, Chang CH, et al.: Has the department of veterans affairs found a way to avoid racial disparities in the evaluation process for kidney transplantation? Transplantation 101: 1191–1199, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Crowley ST, Beddhu S, Chen JLT, Daugirdas JT, Goldfarb DS, et al.: Renal replacement therapy and incremental hemodialysis for veterans with advanced chronic kidney disease. Semin Dial 30: 251–261, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hynes DM, Stroupe KT, Fischer MJ, Reda DJ, Manning W, Browning MM, et al.; for ESRD Cost Study Group : Comparing VA and private sector healthcare costs for end-stage renal disease. Med Care 50: 161–170, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watnick S, Crowley ST: ESRD care within the US Department of Veterans Affairs: A forward-looking program with an illuminating past. Am J Kidney Dis 63: 521–529, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laupacis A, Keown P, Pus N, Krueger H, Ferguson B, Wong C, et al.: A study of the quality of life and cost-utility of renal transplantation. Kidney Int 50: 235–242, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bond CA, Raehl CL: 2006 national clinical pharmacy services survey: Clinical pharmacy services, collaborative drug management, medication errors, and pharmacy technology. Pharmacotherapy 28: 1–13, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.