Abstract

Psychiatric disorders (such as bipolar disorder, depression, and schizophrenia) affect the lives of millions of individuals worldwide. Despite the tremendous efforts devoted to various types of psychiatric studies and rapidly accumulating genetic information, the molecular mechanisms underlying psychiatric disorder development remain elusive. Among the genes that have been implicated in schizophrenia and other mental disorders, disrupted in schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) and glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) have been intensively investigated. DISC1 binds directly to GSK3 and modulates many cellular functions by negatively inhibiting GSK3 activity. The human DISC1 gene is located on chromosome 1 and is highly associated with schizophrenia and other mental disorders. A recent study demonstrated that a neighboring gene of DISC1, translin-associated factor X (TRAX), binds to the DISC1/GSK3β complex and at least partly mediates the actions of the DISC1/GSK3β complex. Previous studies also demonstrate that TRAX and most of its interacting proteins that have been identified so far are risk genes and/or markers of mental disorders. In the present review, we will focus on the emerging roles of TRAX and its interacting proteins (including DISC1 and GSK3β) in psychiatric disorders and the potential implications for developing therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: TRAX, DISC1, GSK3β, Mental disorders, DNA damage, DNA repair, Oxidative stress, A2AR, PKA

Background

Mental disorders (such as bipolar disorder, depression, and schizophrenia) have recently become great concerns because of the resultant heavy social and economic burdens on societies [1–3]. Rapidly progressing genetic technologies have provided many details regarding the genetic nature of mental disorders. Among the genes that have been revealed by genetic analyses of schizophrenia and other mental disorders, the function of disrupted in schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) has been intensively investigated. Biochemical investigations suggest that DISC1 is a scaffold protein that regulates various cellular functions (including cytoskeletal processes, intracellular transport, dendritic spine development activities, neuronal development, the cAMP-signaling pathway, and DNA repair) by interacting with various proteins [4–12]. Thus, DISC1 has been considered as a hub protein for schizophrenia and possibly other mental diseases (Table 1).

Table 1.

Potential involvement of TRAX-interacting proteins in three psychiatric disorders

| Binding partner | Full name | Gene name | Schizophrenia | Autism | Panic attack |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2AR [5, 132, 134] | A2A adenosine receptor | ADORA2A | Drug target [164–166] | Risk gene (#) | Risk gene [167] |

| Akap9 [168] | A-kinase anchoring protein 9 | AKAP9 | Risk gene [169, 170] | Risk gene (#, [171–173]) | Risk gene [167] |

| ATM [137] | Ataxia telangiectasia mutated | ATM | Risk gene [139, 174] | – | – |

| C1D [136] | nuclear matrix protein C1D | C1D | (1) Risk gene (*) | – | – |

| (2) Drug target [175] | |||||

| DISC1 [5] | Disrupted in schizophrenia 1 | DISC1 | (1) Risk gene (*) | Risk gene [176, 177] | Risk gene [167] |

| (2) Drug target [116, 178] | |||||

| GSK3β [5] | Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 Beta | GSK3B | (1) Risk gene (*) | Risk gene [179, 180] | Risk gene [181] |

| (2) Drug target [182] | |||||

| KIF2A [134, 183] | Kinesin Family Member 2A | KIF2A | Risk gene (*) | – | – |

| MEA2 [168] | Male-enhanced antigen 2 | MEA2 | – | – | – |

| PLCβ1 [184, 185] | Phospholipase C Beta 1 | PLCB1 | Risk gene (*, [185–187]) | Risk gene (#, [188]) | – |

| SUN1 [168] | SUN domain-containing protein 1 | SUN1 | – | – | – |

| Translin [126–128, 130, 189, 190] | Translin | TSN | Risk gene [191, 192] | Risk gene (#, [193]) | – |

| TRAX-interacting protein-1 [22] | Translin Associated Factor X Interacting Protein 1 | TSNAXIP1 | Risk gene [194] | – | – |

The corresponding references are listed in parentheses. “-”, no information. *, http://www.szdb.org/score.php. #, https://gene.sfari.org/database/human-gene/

Previous genetic studies have associated DISC1 and a neighboring gene (translin-associated factor X, TSNAX) with multiple mental disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar spectrum disorder, and major depressive disorder) [13–15] (Table 1). TRAX was initially identified as a binding partner of an RNA/DNA-binding protein (translin [16]). Further investigations revealed that similar to DISC1, TRAX regulates distinct cellular functions by selectively binding to designated partner(s). Moreover, the list of TRAX-interacting proteins overlaps with that of DISC1 (Table 2). Both TRAX and DISC1 are involved in facilitating DNA repair [5]. Chien et al. demonstrated that TRAX forms a complex with DISC1 and GSK3β in the cytoplasmic region of resting neurons. Upon stresses that cause oxidative DNA damage, inhibiting GSK3β causes the TRAX/DISC1/GSK3β complex to dissociate and release TRAX to facilitate ATM-mediated DNA repair [5]. Because the incomplete repair of oxidative DNA damage may contribute to the development of psychotic disorders [1, 17, 18] and because TRAX and many of its interacting proteins (Table 1) are risk genes and/or markers of mental disorders, the present review focuses on the emerging role of TRAX/DISC1 interactome(s) in DNA repair as well as their potential implications in psychiatric disorders.

Table 2.

Pathways interacting with DISC1 and/or TRAX

| Pathway | Binding partner | Full name | Interaction with TRAX | Interaction with DISC1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cAMP/PKA | A2AR [5, 132, 134] | A2A adenosine receptor | + [132] | Nd |

| Akap9 [168] | A-Kinase Anchoring Protein 9 | + [168] | + [194, 195] | |

| ATF4 | Activating Transcription Factor 4 | nd | + [194, 196, 197] | |

| ATF5 | Activating Transcription Factor 5 | nd | + [194, 198–200] | |

| ATF7IP | Activating Transcription Factor 7 | nd | + [194] | |

| D2R | Dopamine D2 receptor | nd | + [146] | |

| PDE4B | Phosphodiesterase 4B | nd | + [8, 194, 201] | |

| PDE4D | Phosphodiesterase 4D | nd | + [194, 202] | |

| Wnt signaling | GSK3β [5] | Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 β | + [5] | + [5, 7, 194] |

| β-catenin | Catenin β-1 | nd | + [7, 194, 203] | |

| DIXDC1 | DIX Domain Containing 1 | nd | + [194, 204] | |

| TNIK | TRAF2 And NCK Interacting Kinase | nd | + [194, 205, 206] | |

| WNT3A | Wnt Family Member 3A | nd | + [194] | |

| Intracellular Transport | Dynactin | Dynactin | nd | + [207] |

| FEZ1 | Fasciculation And Elongation Protein Zeta 1 | nd | + [208, 209] | |

| HZF | Haematopoetic zinc finger | nd | + [12] | |

| KIF1B | Kinesin Family Member 1B | nd | + [12] | |

| KIF2A | Kinesin Family Member 2A | + [134, 183] | nd | |

| KIF5A | Kinesin Family Member 5A | nd | + [11, 12] | |

| Miro1/2 | Mitochondrial Rho GTPase 1/2 | nd | + [9, 210] | |

| SNPH | Syntaphilin | nd | + [10] | |

| TRAK1/2 | Trafficking kinesin protein-1/2 | nd | + [9] | |

| Translin | Tanslin | + [211] | nd | |

| DNA repair | ATM | ataxia-telangiectasia mutated | + [137] | nd |

| C1D | nuclear matrix protein C1D | + [136] | nd | |

| Rad21 | Double-strand-break repair protein rad21 homolog | Nd | + [212, 213] |

Accumulating evidence suggests the involvement of DISC1/TRAX in several signaling pathways and machineries that mediate a wide variety of cellular functions. +, direct interaction. nd, not determined. The corresponding references are listed in parentheses

DNA damage, oxidative stress, and mental health

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are usually generated through mitochondrial oxidative reactions [19]. Excessive ROS levels are a source of oxidative stress, which causes oxidative damage to DNA, proteins and lipids. ROS can attack the nitrogenous bases and sugar-phosphate backbone of DNA to cause single- and double-stranded DNA breaks that ultimately lead to genetic mutations and toxicity [20]. When cells are subjected to increased levels of ROS and reactive nitrogen species, multiple cellular impairments (e.g., oxidative DNA damage) occur [21]. Accumulating evidence suggests that elevated ROS levels and the resultant oxidative damage are major factors in human health and diseases [21–24]. Because the brain uses approximately 20% of the total oxygen in the body and generates significant amounts of free radicals, the brain is more susceptible to oxidative stress than other organs. Moreover, elevated ROS levels have been implicated in most neurological diseases (such as mental disorder and neurodegenerative diseases) [25–27]. Elevated levels of serum oxidative markers (such as 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine, 8-OHdG) have also been reported in patients with trauma or diseases of the brain [28–31].

Ample evidence suggests that increased oxidative stress, which may cause oxidative DNA damage and mitochondrial dysfunction, is a common feature of mental disorders in the brain. Mitochondrial dysfunction is associated directly with elevated levels of oxidative stress and the progression of mental disorders [18, 19, 32]. For example, the nuclear gene expression levels of mitochondrial proteins, including electron transport chain (ETC) complexes I–V, are significantly decreased in the hippocampus and postmortem frontal cortex of patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia [33–35]. It is important to note that ETC complex I is one of the major sources of ROS in mitochondria. Moreover, the expression levels of NADH:Ubiquinone oxidoreductase core subunit v2 (NDUFV2), a mitochondrial complex I subunit gene, were decreased in lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from patients with bipolar disorder [36]. These findings indicate that mitochondria dysfunction is a major factor that contributes to the development of mental disorders, including bipolar disorder and schizophrenia [19]. Another important feature of the brains of patients with mental disorders is an imbalance in the levels of dopamine and glutamate (for a review, see [37]). Accumulating evidence suggests that hypofunction of NMDA receptors was observed in schizophrenia [38, 39]. Several NMDA receptor antagonists (e.g., phencyclidine and ketamine) therefore have been shown to induce schizophrenia-like symptoms [40, 41]. Other studies reported that hypofunction of synaptic NMDA receptors are detrimental to neurons. Activation of synaptic NMDA receptors promotes signaling pathways that have been implicated in neuronal survival [42]. Thus, the enhancement of NMDA receptor function may serve as a potential therapeutic strategy for patient with schizophrenia. It should be noted that excess glutamate causes calcium influx and subsequently facilitates the generation of ROS [43, 44].

In addition to high oxidative stress levels, impaired DNA repair is also a pathogenic feature of mental disorders [1]. Many genes involved in DNA repair or DNA damage detection have also been implicated in mental disorders. For example, variants of genes involved in DNA repair, such as x-ray repair cross complementing 1 (XRCC1), XRCC3, human 8-oxoguanine DNA N-glycosylase 1 (hOGG1), and xeroderma pigmentosum group D (XPD), have been documented in schizophrenia pathophysiology [2]. Improving DNA repair is thus a possible strategy for developing therapeutic interventions for mental disorders. In the present review, the emerging role of a new set of risk genes (DISC1, GSK3β, and TRAX) for mental disorders in the repair of oxidative DNA damage will be discussed.

GSK3

GSK3 was originally identified as a highly specific serine/threonine kinase for glycogen synthase in rabbit skeletal muscle [45]. There are two types of GSK3, GSK3α and GSK3β, and these are encoded by two different genes that share 83% identity in humans [46]. GSK3 activity can be regulated positively by the phosphorylation of GSK3α and GSK3β at Tyr279 and Tyr216, respectively [47], and negatively by the phosphorylation of GSK3α and GSK3β at Ser21 and Ser9, respectively [48, 49]. The phosphorylation of Tyr279-GSK3α and Tyr216-GSK3β are intramolecular autophosphorylation events [50], whereas the phosphorylation of Ser21-GSK3α and Ser9-GSK3β can be mediated by several kinases, including AKT [51] and protein kinase A (PKA) [52]. Both GSK3α and GSK3β are expressed highly in the mouse brain [53], whereas GSK3β is mainly expressed in the human brain [54]. GSK3β is thus expected to play a critical role in the brain.

As a kinase, GSK3β is involved in diverse biological activities and pathways by phosphorylating its downstream substrates. Briefly, GSK3β regulates neurite outgrowth, neuronal polarization and microtubule dynamics by phosphorylating several microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs), such as tau [55], MAP1β [56] and collapsin response mediator protein-2 (CRMP-2) [57]. GSK3β also regulates structural synaptic plasticity. GSK3β phosphorylates β-catenin and promotes β-catenin degradation [58]. GSK3β deletion in a subset of cortical and hippocampal neurons results in constitutively active β-catenin, which reduces spine density and excitatory synaptic neurotransmission [59]. GSK3β deletion in dentate gyrus (DG) excitatory neurons also reduces the levels of several synaptic proteins and subunits of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4- isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors and inhibits calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII)/CaMKIV-cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) signaling [60]. Furthermore, GSK3β is involved in long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD). During LTP induction in the DG and CA1 areas of the hippocampus, the phosphorylation level of GSK3β at Ser9 is increased, which subsequently inhibits the induction of LTD [61–63]. GSK3β overexpression in the hippocampus reduces neurotransmitter release and hyper-phosphorylates tau, which impairs the induction of LTP and learning [64, 65]. In addition, GSK3 inhibition rescues the number of abnormal dendritic spines and glutamatergic synapses in pyramidal neurons and may improve the psychiatric pathogenesis caused by DIXDC1/GSK3 axis impairment in mental disorders [66].

GSK3β is also involved in apoptotic regulation in response to several stresses, including DNA damage [67] and oxidative stress [68]. In response to DNA damage, the interaction between GSK3β and p53 enhances the activity of GSK3β and p53-mediated apoptosis via increasing p21 protein levels and caspase-3 activation [67]. GSK3β inactivation protects hippocampal [69] and cerebellar granule neurons [70] from irradiation-induced death through inhibiting p53 accumulation [71]. In neurons, oxidative stress exposure for a short period of time reduces the activity of GSK3β, while prolonged exposure to ROS increases GSK3β activity [72, 73]. Therefore, GSK3β is a redox-sensitive kinase. GSK3β activation in response to oxidative stress downregulates the nuclear-localized NF-E2-related factor 2 (NRF2), which inhibits the expression of antioxidant genes, such as heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), and sensitizes neurons to oxidative stress-induced death [72]. Furthermore, GSK3β activation in response to oxidative stress phosphorylates and induces the degradation of CRMP-2, a cytoskeleton regulator involved in lithium response in bipolar disorder patients [74], and results in axonal degeneration and neuronal death [73, 75]. GSK3β inhibition is thus expected to protect neurons from oxidative stress-induced damage and death. Consistently, GSK3β inhibition through activating A2A adenosine receptor (A2aR) has protective effects on oxidative stress-induced DNA damage because its binding partner (TRAX) is released to facilitate DNA repair and improve survival [5].

Accumulating evidence suggests that the dysregulation of GSK3β and/or its up/downstream molecules may contribute to bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. The inhibitory phosphorylation levels of GSK3 are lower in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from bipolar disorder patients than in those from healthy controls [76], but not in platelets [77]. Interestingly, although the protein levels of GSK3 are higher in PBMCs from type 1 bipolar disorder patients than in those from normal subjects, the amount of inhibitory GSK3 phosphorylation shows only a decreasing trend [78]. Conversely, the protein levels of GSK3β in the frontal cortex and cerebrospinal fluid are lower in schizophrenia patients than in normal subjects [79, 80]. However, other studies have failed to show changes in the protein levels or activity of GSK3β in patients with mental diseases compared to normal controls [81, 82].

One reason that GSK3β is linked to psychiatric diseases is that GSK3 is a target of lithium, a mood stabilizer used to treat mental diseases [83]. Lithium enhances the phosphorylation of GSK3β at Ser9 to inhibit GSK3β directly through competition with magnesium [84] and indirectly by activating AKT [85]. Significant efforts have thus been devoted to the design and development of new GSK3 inhibitors [86–89]. Several new GSK3 inhibitors have been assessed in mouse models of bipolar diseases. For example, the maleimide derivative, 3-(Benzofuran-3-yl)-4-(indol-3-yl)maleimide compound 2B, which mimics the structure of lithium, inhibits GSK3β activity and locomotor hyperactivity induced by the combination of amphetamine and chlordiazepoxide as a model for the manic phase of bipolar disease [90]. Additional GSK3 inhibitors (including indirubin, alsterpaullone, TDZD-8, AR-A014418, SB-216763, and SB-627772) were shown to inhibit rearing hyperactivity in the amphetamine-induced hyperactivity [91]. In the present review, we focus on a novel function of GSK3 that may provide new insights into the role of GSK3 in neuronal development and psychiatric pathogenesis.

DISC1

DISC1 was initially identified in a large Scottish family with a spectrum of mental diseases (including schizophrenia, recurrent major depression and bipolar disorder) [92–95]. The N-terminal globular domain of DISC1 contains a conserved nuclear localization signal, and the C-terminal coiled-coil region is predicted to mediate its interactions with different proteins [96]. DISC1 is highly expressed in the heart, brain and placenta of humans [94] and in the heart, brain, kidney, and testis of mice [97]. DISC1 expression in the brain is regulated during development; its highest level occurs during the neonatal-infancy period and decreases gradually with age in human brains [98]. It is important to note that DISC1 expression may be regulated by environmental stimuli too. For example, the activation of Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) during viral infection leads to the downregulation of DISC1 through myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MYD88) and subsequently impairs dendritic arborization and neuronal development [99]. Such cytoarchitectural defects (e.g., dendritic organization) have been found in schizophrenic subjects [100, 101], suggesting the importance of DISC1 in the regulation of neuronal development at prenatal and neonatal stages. Given the correlation between the deficits in neuronal development and the risk of developing schizophrenia, schizophrenia is also referred to as a neurodevelopmental disorder.

Previous studies suggest that DISC1 functions as a scaffold protein and mediates diverse neurodevelopmental processes by interacting with different proteins (Table 2). Specifically, DISC1 regulates cytoskeletal processes (e.g., neurite outgrowth and neuronal migration) by interacting with several proteins that are localized to the centrosome and axonal growth cones, including lissencephaly 1 (LIS1), nuclear distribution nudE-Like 1 (NDEL1) [11, 102], NDE1 [103], pericentriolar material 1 (PCM1), and Bardet-Biedl syndrome 4 (BBS4) [104].Given that DISC1 is located at the post-synaptic density (PSD) in the human neocortex [105], DISC1 is likely to play an important role in dendritic spine development and synaptic activities. DISC1 interacts with kalirin-7 (kal-7) at the glutamatergic PSD and mediates the interaction between kal-7 and PSD-95 or Rac family small GTPase 1 (Rac1) to regulate the size and number of spines [6].

Another important function of DISC1 is its regulation of the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-signaling pathway by binding and inhibiting phosphodiesterase 4B (PDE4B; Table 2). Increased cAMP levels cause DISC1 and PDE4B dissociation and enhance PDE4B activity [8]. The DISC1/PDE4 complex also regulates the PKA-mediated phosphorylation and association of a complex (NDE1/LIS1/NDEL1) important for neuronal development [106]. In addition, DISC1 interacts with several key molecules in the cAMP/PKA pathway, including an anchoring protein of PKA (A-kinase anchoring protein 9 (AKAP9); Table 2), several transcription factors (activating transcription factor 4 and 5 (ATF4 and ATF5); Table 2) that recognize the cAMP response element, and a Giα-coupled receptor that suppresses cAMP production upon activation (D2 dopamine receptor (D2R); Table 2).

DISC1 also plays an important role in intracellular transport (Table 2). By interacting with syntaphilin (SNPH), Mitochondrial Rho GTPase 1/2 (Miro1/2), and Trafficking kinesin protein-1/2 (TRAK1/2), DISC1 mediates the transport of mitochondria in the axons and dendrites [4, 9, 10]. DISC1 is involved in the transport of synaptic vesicles because it stabilizes the interaction between fasciculation and elongation protein zeta 1 (FEZ1) and synaptotagmin-1 (SYT-1) in the axons [107]. Moreover, DISC1 interacts with hematopoietic zinc finger (HZF) to mediate the dendritic transport of inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 1(ITRP1) mRNA [12].

Another important interacting protein of DISC1 is GSK3β, as well as several proteins involved in the Wnt pathway (Table 2). The direct binding of DISC1 inhibits GSK3β activity [7]. The interaction between DISC1 and GSK3β controls the fate of neural progenitors in the ventricular zone/subventricular zone [7] and subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus [97]. GSK3β inhibition prevents the phosphorylation and degradation of β-catenin, its downstream target [58], resulting in increased neural progenitor proliferation [108]. Intriguingly, the phosphorylation of DISC1 at Ser710 determines the affinity of DISC1 toward its binding partners. For example, non-phosphorylated DISC1 at Ser710 inhibits GSK3β and subsequently activates β-catenin signaling. Conversely, the phosphorylation of DISC1 at Ser710 increases the affinity of DISC1 for another binding partner, BBS protein, which facilitates the recruitment of BBS to the centrosome and subsequently causes the transition from progenitor proliferation to neuronal migration in the developing cortex [109]. It is interesting to note that the PKA-mediated inhibitory phosphorylation of GSK3β at Ser9 leads to the dissociation of the DISC1/GSK3β/TRAX complex and facilitates TRAX-mediated DNA repair in neurons [5]. These results collectively suggest that phosphorylation is a key modulatory mechanism that regulates the complex formation of DISC1 and other interaction proteins through which a wide variety of cellular functions are regulated.

Ample genetic evidence links DISC1 with major mental illnesses. The balanced (1;11) translocation of DISC1 within a Scottish family increased the incidence of major mental illnesses [95], probably due to the decrease in DISC1 protein levels [8] or the production of a dominant-negative C-terminal truncated DISC1 that loses its interaction with DISC1-interacting proteins [110, 111]. In addition, expression levels of the DISC1-interacting proteins LIS1 and NDEL1 are decreased in the brains of schizophrenia patients and are associated with high-risk DISC1 SNPs [98]. To date, the DISC1 gene has been identified as a risk factor for major mental illnesses [13, 112–120]. In contrast, some other reports have failed to show the association between DISC1 variants and mental diseases [121–123]. Further investigations of the roles of DISC1 in mental disorders are needed.

TRAX

TRAX was first discovered as a binding partner of translin using a yeast two-hybrid system. Amino acid sequence alignment revealed that TRAX displays 28% identity with translin [16]. Because the genetic removal of translin promotes the degradation of TRAX, TRAX stability appears to be controlled by its binding partner (i.e., translin [124]). Both TRAX and translin are highly enriched in the brain. The heteromeric complex composed of TRAX and translin shows nucleic acid binding activity in brain extracts [125] and plays a role in dendritic RNA trafficking in neurons [126, 127]. The heteromeric translin/TRAX complex also functions as an endoribonuclease that cleaves passenger strands of siRNA and therefore facilities siRNA guide strand loading onto the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) in Drosophila [128]. In contrast, the TRAX/translin complex suppresses microRNA (miRNA)-mediated silencing in mammalian cells by degrading pre-miRNA with mismatched stems and subsequently reversing miRNA-mediated silencing [129] (Fig. 1). In support of this hypothesis, TRAX/translin was recently shown to play a critical role in regulating long-term memory by suppressing microRNA silencing at activated synapses [130]. Given that aberrant profiles of miRNAs and their targeted genes have been implicated in mental disorders (such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and autism) (for a review, see [131]), the role of abnormal TRAX/translin regulation in mental disorders warrants future investigations.

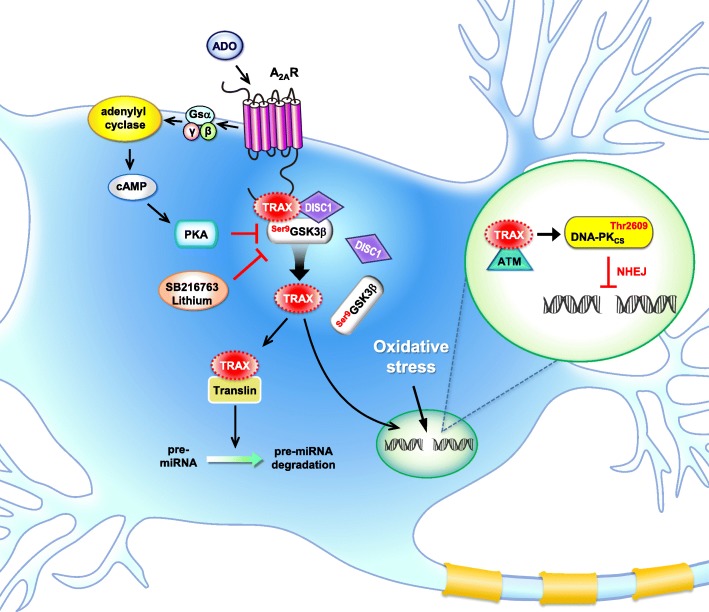

Fig. 1.

A schematic representation showing the major functions of TRAX and its interacting proteins. In neurons, TRAX interacts with the C terminus of the A2A adenosine receptor (A2AR), a Gsα-coupled receptor that activates adenylyl cyclase to produce cAMP upon stimulation with adenosine (ADO). At the resting stage, TRAX forms complexes with GSK3β and DISC1. High oxidative stress is known to cause double-strand DNA breaks. Activating the A2AR/PKA-dependent pathway or inhibiting GSK3β using selective inhibitors (e.g., SB216763 or lithium) release TRAX from the complex and assist in ATM/DNA-PK-dependent non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair in the nuclei [5, 137]. TRAX may also bind with translin to regulate the amount of miRNA and downstream gene expression profiles [130].

Similar to DISC1, TRAX also has many interacting proteins with a wide variety of functions. Most of these TRAX-interacting proteins are risk genes, markers, or drug targets for psychotic disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, autism, and panic disorders; Table 1). For example, A2AR is the binding partner of TRAX [132]. A2AR is a Gsα-coupled receptor that activates the cAMP/PKA pathway upon stimulation [133]. A2AR activation or TRAX overexpression rescues the impaired neurite outgrowth caused by p53 blockade in a neuronal cell line (PC12) and primary hippocampal neurons. Knocking down TRAX or preventing the interaction between TRAX and its interacting protein (kinesin heavy chain member 2A, KIF2A) blocks the rescue effect of A2AR activation [134]. Of note, KIF2A is a schizophrenia susceptibility gene [135]. A2AR is a risk gene for autism and anxiety disorders, and a marker for schizophrenia (Table 1).

Two of the TRAX-interacting proteins (C1D and ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase) are involved directly in DNA repair. C1D is an activator of DNA- dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK). Upon DNA damage induced by γ-irradiation, TRAX increasingly interacts with C1D in mammalian cells, suggesting that TRAX might participate in DNA repair [136]. ATM is a serine/threonine kinase and is activated and recruited by DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) to phosphorylated proteins (e.g., histone H2A (H2AX) and p53) that are important for DNA repair. In the absence of TRAX, ATM fails to be recruited to DSB sites to initiate the DNA repair machinery and subsequently causes cell death due to insufficient DNA damage repair [5, 137]. During oxidative stress-induced DNA damage in neurons, TRAX forms a complex with DISC1 and GSK3β in the cytoplasmic region. A2AR stimulation activates PKA, which phosphorylates GSK3β at Ser9 and dissociates the TRAX/DISC1/GSK3β complex so that TRAX can enter the nuclei to facilitate DNA repair [5] (Fig. 1). The role of TRAX and its interacting proteins in mental disorders appear important because ample evidence suggests that incomplete oxidative DNA damage repair may contribute to the development of psychotic disorders [1, 17, 18]. Most of the major components (including ATM, [138, 139]) involved in TRAX-mediated DNA repair are also risk genes of mental disorders (Table 1).

Consistent with the hypothesis that TRAX is involved in the development of mental disorders, genetic studies have implicated TRAX in major psychiatric diseases. The human TSNAX gene is located at 1q42.1 and adjacent to the DISC1 gene. Several TSNAX transcripts contain the DISC1 sequence at the 3’ end due to intergenic splicing in human adult and fetal tissues [93]. A SNP analysis revealed that 2 SNPs (i.e., rs1615409 and rs766288) are located within intron 4 of TSNAX, and 2 SNPs (i.e., rs751229 and rs3738401) were found in DISC1 in Finnish schizophrenia patients [13]. A rare AATG haplotype comprising these 4 SNPs is positively associated with the reaction time to visual targets and negatively with the gray matter density in Finnish schizophrenia patients [140]. Furthermore, another SNP analysis identified that rs1655285 at intron 5 of TSNAX and a haplotype comprising rs1630250 and rs1615409 within TSNAX are associated with Finnish bipolar spectrum disorder [15]. The SNP rs766288 at intron 4 of TSNAX has been reported to be associated with Japanese female major depressive disorder [14]. These studies collectively suggest that TRAX is a risk gene for major mental diseases. It should also be noted that TRAX and DISC1 share several interacting proteins (e.g., GSK3β and AKAP9; Table 2) and functional pathways/machineries (e.g., the cAMP/PKA pathway, Wnt signaling, intracellular transport and DNA repair; Table 2); thus, they may act together to regulate important pathophysiological events, including the development of mental disorders.

Regulation of the TRAX/DISC1/GSK3β complex and therapeutic relevance

Although DISC1 mediates many different cellular functions, it has not been implicated in DNA repair until a recent report [5] demonstrating that DISC1 interacts with GSK3β and TRAX; this complex facilitates DNA repair by binding to ATM [137]. This finding leads to a new mechanistic role of DISC1 in mental disorders in which accumulating oxidative DNA damage and insufficient DNA repair contribute to the pathogenesis [1, 17, 18]. Disassembly of the TRAX/DISC1/GSK3β complex, followed by the release of TRAX, provides a new means to facilitate DNA repair and ameliorate the damage caused by unrepaired DSBs. For example, A2AR activation dissociates TRAX/DISC1/GSK3β complex tethering at its C terminus through a PKA-dependent pathway and amends the DNA damage-induced apoptosis [5]. Consistent with an important role of A2AR in facilitating DNA repair, A2AR activation ameliorates oxidative DNA damage in human medium spiny neurons (MSNs) derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [141]. Interestingly, the amount of A2AR is altered in different brain regions of patients with schizophrenia [142, 143], supporting that A2AR might play an important role in schizophrenia. Because A2AR is an antagonistic binding partner of the D2R and may suppress the hyperfunction of D2R in schizophrenia [144], A2AR agonists are potentially advantageous anti-schizophrenic drugs (for a review, see [145]). D2R is a primary target of antipsychotic drugs. It forms complex with not only A2AR but also DISC1 to mediate the D2R-dependent activation of GSK3β [146]. This is of great interest because DISC1 binds with TRAX and GSK3β [5]. Whether D2R activation affects the accumulation of oxidative DNA damage and contributes to pathogenesis requires further investigation.

It is important to note that adenosine is known to regulate the dopamine and glutamate- mediated neurotransmissions, the major neurotransmitter systems involved in schizophrenia pathophysiology [147–149]. Dysfunction of purinergic system is one of the factors that cause schizophrenia [149, 150]. Moreover, inhibition of adenosine kinase (ADK), which controls adenosine level, exhibits anti-psychotic-like efficacy, while overexpression of ADK causes changes in the sensitivity to psychomimetic drugs in mice [151, 152]. Consistent with the abovementioned hypothesis, increased brain adenosine tone using an inhibitor of adenosine uptake (i.e., dipyridamole) indirectly activates adenosine receptors and hasWr beneficial effects on patients with schizophrenia [153]. Likewise, inhibiting adenosine clearance using ABT702 to globally increase adenosine tone also ameliorates the psychotic and cognitive phenotypes of schizophrenia in mice [151]. Given that adenosine is also known to play an important role during neurodevelopment. (for a review, see [154]). Augmenting the adenosine tone in the brain using various approaches might thus serve as a therapeutic means to treat schizophrenia as well as to prevent the development of schizophrenia [154, 155].

Lithium is an inhibitor of GSK3 and a common mood stabilizer for treating mental disorders. To date, the underlying molecular mechanism of lithium’s action remains largely elusive [156, 157]. Accumulating evidence suggests that chronic treatment with lithium inhibits the oxidative damage evoked by glutamate [158] and increases the expression level of the anti-apoptotic factor Bcl2 [159, 160]. Treatment with lithium also protects neurons by facilitating the NHEJ repair-mediated DNA repair pathway [161]. Chronic treatment with lithium results in not only the inhibition of GSK3β but also the regulation of many anti-apoptotic proteins. For example, lithium inhibits calcium influx via regulating the NMDA receptor and reduces apoptosis by directly inhibiting GSK3β [162]. Because inhibiting GSK3β causes the disassembly of the TRAX/DISC1/GSK3β complex and releases TRAX to facilitate DNA repair [5], at least part of the actions of lithium might be mediated by the TRAX/DISC1/GSK3β complex. New GSK3β inhibitors have been actively developed for brain diseases [163], which may pave the way for establishing new treatments for schizophrenia.

Conclusions

As a major gene implicated in schizophrenia and other mental disorders, DISC1 is known to regulate various cellular functions by interacting with proteins of different machineries. Ample evidence suggests that DISC1 is a hub protein for schizophrenia and possibly other mental diseases. Emerging evidence also suggests that TRAX, a neighboring gene of DISC1, not only physically interacts with DISC1 but also switches binding partners under different pathophysiological conditions as does DISC1. Because the studies regarding TRAX are still in their infancy, the overlapping functional pathways of DISC1 and TRAX appear limited at this time (Table 2) but may become more evident when more binding partners of TRAX are revealed in the future. Most importantly, genetic evidence suggests that DISC1 and TRAX are closely associated with several major mental disorders (such as schizophrenia, autism, and anxiety disorder; Table 1). Therefore, it is certainly worth further exploring the role of the DISC1/TRAX complex in psychiatric disorders. Because oxidative DNA damage accumulation and insufficient DNA repair have been implicated in the development and progression of mental disorders, the recently reported function of the DISC1/TRAX/GSK3β complex in DNA repair also warrants further investigations of the temple and the special regulation of this complex during neuronal development and disease progression. Further understanding of when and where the DISC1/TRAX/GSK3β complex is formed and how the complex can be effectively dissembled by either GSK3β inhibitors or PKA activators (such as A2AR agonists or PDE4 inhibitors) would pave the way for developing new therapeutic agents for mental disorders.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Tsung Hung Hung at the Medical Art Room of Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Academia Sinica for the preparation of Fig. 1.

Funding

This work was supported by the Institute of the Biomedical Sciences of Academia Sinica (103-Academia Sinica Investigation Award-06).

Abbreviations

- 8-OHdG

8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine

- A2aR

A2A adenosine receptor

- ADK

Adenosine kinase

- ADO

Adenosine

- AKAP9

A-kinase anchoring protein 9

- AMPA

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4- isoxazolepropionic acid

- ATF

Activating transcription factor

- ATM

Ataxia-telangiectasia mutated

- BBS4

Bardet-Biedl syndrome 4

- C1D

Nuclear matrix protein C1D

- cAMP

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CREB

Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII)/CaMKIV-cAMP response element binding protein

- CRMP-2

Collapsin response mediator protein-2

- D2R

D2 Dopamine receptor

- DG

Dentate gyrus

- DISC1

Disrupted in schizophrenia 1

- DIXDC1

DIX domain containing 1

- DNA-PK

DNA- dependent protein kinase

- DSBs

DNA double-strand breaks

- ETC

Electron transport chain

- FEZ1

Fasciculation and elongation protein zeta 1

- GSK3

Glycogen synthase kinase 3

- H2AX

Histone H2A

- HO-1

Heme oxygenase-1

- hOGG1

Human 8-oxoguanine DNA N-glycosylase 1

- HZF

Hematopoietic zinc finger

- iPSCs

Induced pluripotent stem cells

- ITRP1

Inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 1

- kal-7

Kalirin-7

- KIF2A

Kinesin heavy chain member 2A

- LIS1

Lissencephaly 1

- LTD

Long-term depression

- LTP

Long-term potentiation

- MAPs

Microtubule-associated proteins

- MEA2

Male-enhanced antigen 2

- miRNA

microRNA

- Miro1/2

Mitochondrial Rho GTPase 1/2

- MSNs

Medium spiny neurons

- MYD88

Myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88

- NDEL1

Nuclear distribution nudE-Like 1

- NDUFV2

NADH:Ubiquinone oxidoreductase core subunit V2

- NHEJ

Non-homologous end joining

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- NRF2

Nuclear-localized NF-E2-related factor 2

- PBMCs

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PCM1

Pericentriolar material 1

- PCP

Phencyclidine

- PDE4B

Phosphodiesterase 4B

- PKA

Protein kinase A

- PLCβ1

Phospholipase C Beta 1

- PSD

Post-synaptic density

- Rac1

Rac family small GTPase 1

- Rad21

Double-strand-break repair protein rad21 homolog

- RISC

RNA-induced silencing complex

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SNPH

Syntaphilin

- SUN1

SUN domain-containing protein 1

- SYT-1

Synaptotagmin-1

- TLR3

Toll-like receptor 3

- TNIK

TRAF2 and NCK interacting kinase

- TRAK1/2

Trafficking kinesin protein-1/2

- TRAX

Translin-associated factor X

- WNT3A

Wnt family member 3A

- XPD

Xeroderma pigmentosum group D

- XRCC

X-ray repair cross complementing

Authors’ contributions

YC outlined and wrote the manuscript. YTW wrote part of the manuscript and prepared the tables. TC wrote part of the manuscript and prepared the figure and table. IIK analyzed literatures and prepared tables. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yu-Ting Weng, Email: r96b46010@ntu.edu.tw.

Ting Chien, Email: tingchien0628@gmail.com.

I-I Kuan, Email: lia3677@gmail.com.

Yijuang Chern, Email: bmychern@ibms.sinica.edu.tw.

References

- 1.Markkanen Enni, Meyer Urs, Dianov Grigory. DNA Damage and Repair in Schizophrenia and Autism: Implications for Cancer Comorbidity and Beyond. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2016;17(6):856. doi: 10.3390/ijms17060856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Odemis S, Tuzun E, Gulec H, Semiz UB, Dasdemir S, Kucuk M, Yalcinkaya N, Bireller ES, Cakmakoglu B, Kucukali CI. Association between polymorphisms of DNA repair genes and risk of schizophrenia. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2016;20(1):11–17. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2015.0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raza MU, Tufan T, Wang Y, Hill C, Zhu MY. DNA damage in major psychiatric diseases. Neurotox Res. 2016;30(2):251–267. doi: 10.1007/s12640-016-9621-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkin TA, MacAskill AF, Brandon NJ, Kittler JT. Disrupted in Schizophrenia-1 regulates intracellular trafficking of mitochondria in neurons. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16(2):122–124. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chien T, Weng YT, Chang SY, Lai HL, Chiu FL, Kuo HC, Chuang DM, Chern Y. GSK3beta negatively regulates TRAX, a scaffold protein implicated in mental disorders, for NHEJ-mediated DNA repair in neurons. Mol Psychiatry. 2018. 10.1038/s41380-017-0007-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Hayashi-Takagi A, Takaki M, Graziane N, Seshadri S, Murdoch H, Dunlop AJ, Makino Y, Seshadri AJ, Ishizuka K, Srivastava DP, Xie Z, Baraban JM, Houslay MD, Tomoda T, Brandon NJ, Kamiya A, Yan Z, Penzes P, Sawa A. Disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) regulates spines of the glutamate synapse via Rac1. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(3):327–332. doi: 10.1038/nn.2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mao Y, Ge X, Frank CL, Madison JM, Koehler AN, Doud MK, Tassa C, Berry EM, Soda T, Singh KK, Biechele T, Petryshen TL, Moon RT, Haggarty SJ, Tsai LH. Disrupted in schizophrenia 1 regulates neuronal progenitor proliferation via modulation of GSK3beta/beta-catenin signaling. Cell. 2009;136(6):1017–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Millar JK, Pickard BS, Mackie S, James R, Christie S, Buchanan SR, Malloy MP, Chubb JE, Huston E, Baillie GS, Thomson PA, Hill EV, Brandon NJ, Rain JC, Camargo LM, Whiting PJ, Houslay MD, Blackwood DH, Muir WJ, Porteous DJ. DISC1 and PDE4B are interacting genetic factors in schizophrenia that regulate cAMP signaling. Science. 2005;310(5751):1187–1191. doi: 10.1126/science.1112915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norkett R, Modi S, Birsa N, Atkin TA, Ivankovic D, Pathania M, Trossbach SV, Korth C, Hirst WD, Kittler JT. DISC1-dependent regulation of mitochondrial dynamics controls the morphogenesis of complex neuronal dendrites. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(2):613–629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.699447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park C, Lee SA, Hong JH, Suh Y, Park SJ, Suh BK, Woo Y, Choi J, Huh JW, Kim YM, Park SK. Disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) and Syntaphilin collaborate to modulate axonal mitochondrial anchoring. Mol Brain. 2016;9(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s13041-016-0250-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taya S, Shinoda T, Tsuboi D, Asaki J, Nagai K, Hikita T, Kuroda S, Kuroda K, Shimizu M, Hirotsune S, Iwamatsu A, Kaibuchi K. DISC1 regulates the transport of the NUDEL/LIS1/14-3-3epsilon complex through kinesin-1. J Neurosci. 2007;27(1):15–26. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3826-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsuboi D, Kuroda K, Tanaka M, Namba T, Iizuka Y, Taya S, Shinoda T, Hikita T, Muraoka S, Iizuka M, Nimura A, Mizoguchi A, Shiina N, Sokabe M, Okano H, Mikoshiba K, Kaibuchi K. Disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1 regulates transport of ITPR1 mRNA for synaptic plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(5):698–707. doi: 10.1038/nn.3984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hennah W, Varilo T, Kestila M, Paunio T, Arajarvi R, Haukka J, Parker A, Martin R, Levitzky S, Partonen T, Meyer J, Lonnqvist J, Peltonen L, Ekelund J. Haplotype transmission analysis provides evidence of association for DISC1 to schizophrenia and suggests sex-dependent effects. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(23):3151–3159. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okuda A, Kishi T, Okochi T, Ikeda M, Kitajima T, Tsunoka T, Okumukura T, Fukuo Y, Kinoshita Y, Kawashima K, Yamanouchi Y, Inada T, Ozaki N, Iwata N. Translin-associated factor X gene (TSNAX) may be associated with female major depressive disorder in the Japanese population. NeuroMolecular Med. 2010;12(1):78–85. doi: 10.1007/s12017-009-8090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palo OM, Antila M, Silander K, Hennah W, Kilpinen H, Soronen P, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Kieseppa T, Partonen T, Lonnqvist J, Peltonen L, Paunio T. Association of distinct allelic haplotypes of DISC1 with psychotic and bipolar spectrum disorders and with underlying cognitive impairments. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16(20):2517–2528. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aoki K, Ishida R, Kasai M. Isolation and characterization of a cDNA encoding a Translin-like protein, TRAX. FEBS Lett. 1997;401(2–3):109–112. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(96)01444-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steckert AV, Valvassori SS, Moretti M, Dal-Pizzol F, Quevedo J. Role of oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder. Neurochem Res. 2010;35(9):1295–1301. doi: 10.1007/s11064-010-0195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang JF, Shao L, Sun X, Young LT. Increased oxidative stress in the anterior cingulate cortex of subjects with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(5):523–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prabakaran S, Swatton JE, Ryan MM, Huffaker SJ, Huang JT, Griffin JL, Wayland M, Freeman T, Dudbridge F, Lilley KS, Karp NA, Hester S, Tkachev D, Mimmack ML, Yolken RH, Webster MJ, Torrey EF, Bahn S. Mitochondrial dysfunction in schizophrenia: evidence for compromised brain metabolism and oxidative stress. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9(7):684–697. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kavanagh JN, Redmond KM, Schettino G, Prise KM. DNA double strand break repair: a radiation perspective. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18(18):2458–2472. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mariani E, Polidori MC, Cherubini A, Mecocci P. Oxidative stress in brain aging, neurodegenerative and vascular diseases: an overview. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2005;827(1):65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chestkov IV, Jestkova EM, Ershova ES, Golimbet VG, Lezheiko TV, Kolesina NY, Dolgikh OA, Izhevskaya VL, Kostyuk GP, Kutsev SI, Veiko NN, Kostyuk SV. ROS-induced DNA damage associates with abundance of mitochondrial DNA in white blood cells of the untreated schizophrenic patients. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. 2018;8587475:2018. doi: 10.1155/2018/8587475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hassan W, Noreen H, Castro-Gomes V, Mohammadzai I, da Rocha JB, Landeira-Fernandez J. Association of Oxidative Stress with psychiatric disorders. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22(20):2960–2974. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666160307145931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Velzen LS, Wijdeveld M, Black CN, van Tol MJ, van der Wee NJA, Veltman DJ, Penninx B, Schmaal L. Oxidative stress and brain morphology in individuals with depression, anxiety and healthy controls. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017;76:140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ng F, Berk M, Dean O, Bush AI. Oxidative stress in psychiatric disorders: evidence base and therapeutic implications. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11(6):851–876. doi: 10.1017/S1461145707008401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salim S. Oxidative stress and psychological disorders. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2014;12(2):140–147. doi: 10.2174/1570159X11666131120230309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salim S. Oxidative stress and the central nervous system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2017;360(1):201–205. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.237503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ceylan D, Scola G, Tunca Z, Isaacs-Trepanier C, Can G, Andreazza AC, Young LT, Ozerdem A. DNA redox modulations and global DNA methylation in bipolar disorder: effects of sex, smoking and illness state. Psychiatry Res. 2018;261:589–596. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen CM, Wu YR, Cheng ML, Liu JL, Lee YM, Lee PW, Soong BW, Chiu DT. Increased oxidative damage and mitochondrial abnormalities in the peripheral blood of Huntington's disease patients. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;359(2):335–340. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang MC, Lai YC, Lin SK, Chen CH. Increased blood 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine levels in methamphetamine users during early abstinence. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2018;44(3):395–402. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2017.1344683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soeiro-de-Souza MG, Andreazza AC, Carvalho AF, Machado-Vieira R, Young LT, Moreno RA. Number of manic episodes is associated with elevated DNA oxidation in bipolar I disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16(7):1505–1512. doi: 10.1017/S1461145713000047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deicken RF, Fein G, Weiner MW. Abnormal frontal lobe phosphorous metabolism in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(6):915–918. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.6.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ben-Shachar D, Karry R. Sp1 expression is disrupted in schizophrenia; a possible mechanism for the abnormal expression of mitochondrial complex I genes, NDUFV1 and NDUFV2. PLoS One. 2007;2(9):e817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Konradi C, Eaton M, MacDonald ML, Walsh J, Benes FM, Heckers S. Molecular evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction in bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(3):300–308. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun X, Wang JF, Tseng M, Young LT. Downregulation in components of the mitochondrial electron transport chain in the postmortem frontal cortex of subjects with bipolar disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2006;31(3):189–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Washizuka S, Kakiuchi C, Mori K, Kunugi H, Tajima O, Akiyama T, Nanko S, Kato T. Association of mitochondrial complex I subunit gene NDUFV2 at 18p11 with bipolar disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2003;120B(1):72–78. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Howes O, McCutcheon R, Stone J. Glutamate and dopamine in schizophrenia: an update for the 21st century. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29(2):97–115. doi: 10.1177/0269881114563634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Banerjee A, Wang HY, Borgmann-Winter KE, MacDonald ML, Kaprielian H, Stucky A, Kvasic J, Egbujo C, Ray R, Talbot K, Hemby SE, Siegel SJ, Arnold SE, Sleiman P, Chang X, Hakonarson H, Gur RE, Hahn CG. Src kinase as a mediator of convergent molecular abnormalities leading to NMDAR hypoactivity in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20(9):1091–1100. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao XM, Sakai K, Roberts RC, Conley RR, Dean B, Tamminga CA. Ionotropic glutamate receptors and expression of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits in subregions of human hippocampus: effects of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(7):1141–1149. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.7.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farber NB. The NMDA receptor hypofunction model of psychosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1003:119–130. doi: 10.1196/annals.1300.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Javitt DC. Glutamate and schizophrenia: phencyclidine, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors, and dopamine-glutamate interactions. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;78:69–108. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(06)78003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hardingham GE, Fukunaga Y, Bading H. Extrasynaptic NMDARs oppose synaptic NMDARs by triggering CREB shut-off and cell death pathways. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5(5):405–414. doi: 10.1038/nn835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hirose K, Chan PH. Blockade of glutamate excitotoxicity and its clinical applications. Neurochem Res. 1993;18(4):479–483. doi: 10.1007/BF00967252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zeevalk GD, Bernard LP, Sinha C, Ehrhart J, Nicklas WJ. Excitotoxicity and oxidative stress during inhibition of energy metabolism. Dev Neurosci. 1998;20(4–5):444–453. doi: 10.1159/000017342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Embi N, Rylatt DB, Cohen P. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 from rabbit skeletal muscle. Separation from cyclic-AMP-dependent protein kinase and phosphorylase kinase. Eur J Biochem. 1980;107(2):519–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb06059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ali A, Hoeflich KP, Woodgett JR. Glycogen synthase kinase-3: properties, functions, and regulation. Chem Rev. 2001;101(8):2527–2540. doi: 10.1021/cr000110o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hughes K, Nikolakaki E, Plyte SE, Totty NF, Woodgett JR. Modulation of the glycogen synthase kinase-3 family by tyrosine phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1993;12(2):803–808. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05715.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stambolic V, Woodgett JR. Mitogen inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta in intact cells via serine 9 phosphorylation. Biochem J. 1994;303(Pt 3):701–704. doi: 10.1042/bj3030701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sutherland C, Cohen P. The alpha-isoform of glycogen synthase kinase-3 from rabbit skeletal muscle is inactivated by p70 S6 kinase or MAP kinase-activated protein kinase-1 in vitro. FEBS Lett. 1994;338(1):37–42. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cole A, Frame S, Cohen P. Further evidence that the tyrosine phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) in mammalian cells is an autophosphorylation event. Biochem J. 2004;377(Pt 1):249–255. doi: 10.1042/bj20031259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cross DA, Alessi DR, Cohen P, Andjelkovich M, Hemmings BA. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature. 1995;378(6559):785–789. doi: 10.1038/378785a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fang X, Yu SX, Lu Y, Bast RC, Jr, Woodgett JR, Mills GB. Phosphorylation and inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 by protein kinase A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(22):11960–11965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220413597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yao HB, Shaw PC, Wong CC, Wan DC. Expression of glycogen synthase kinase-3 isoforms in mouse tissues and their transcription in the brain. J Chem Neuroanat. 2002;23(4):291–297. doi: 10.1016/S0891-0618(02)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lau KF, Miller CC, Anderton BH, Shaw PC. Expression analysis of glycogen synthase kinase-3 in human tissues. J Pept Res. 1999;54(1):85–91. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.1999.00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cho JH, Johnson GV. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta phosphorylates tau at both primed and unprimed sites. Differential impact on microtubule binding. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(1):187–193. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206236200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lucas FR, Goold RG, Gordon-Weeks PR, Salinas PC. Inhibition of GSK-3beta leading to the loss of phosphorylated MAP-1B is an early event in axonal remodelling induced by WNT-7a or lithium. J Cell Sci. 1998;111(Pt 10):1351–1361. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.10.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yoshimura T, Kawano Y, Arimura N, Kawabata S, Kikuchi A, Kaibuchi K. GSK-3beta regulates phosphorylation of CRMP-2 and neuronal polarity. Cell. 2005;120(1):137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aberle H, Bauer A, Stappert J, Kispert A, Kemler R. Beta-catenin is a target for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. EMBO J. 1997;16(13):3797–3804. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ochs SM, Dorostkar MM, Aramuni G, Schon C, Filser S, Poschl J, Kremer A, Van Leuven F, Ovsepian SV, Herms J. Loss of neuronal GSK3beta reduces dendritic spine stability and attenuates excitatory synaptic transmission via beta-catenin. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20(4):482–489. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu E, Xie AJ, Zhou Q, Li M, Zhang S, Li S, Wang W, Wang X, Wang Q, Wang JZ. GSK-3beta deletion in dentate gyrus excitatory neuron impairs synaptic plasticity and memory. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):5781. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06173-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cai F, Wang F, Lin FK, Liu C, Ma LQ, Liu J, Wu WN, Wang W, Wang JH, Chen JG. Redox modulation of long-term potentiation in the hippocampus via regulation of the glycogen synthase kinase-3beta pathway. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45(7):964–970. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hooper C, Markevich V, Plattner F, Killick R, Schofield E, Engel T, Hernandez F, Anderton B, Rosenblum K, Bliss T, Cooke SF, Avila J, Lucas JJ, Giese KP, Stephenson J, Lovestone S. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibition is integral to long-term potentiation. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25(1):81–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peineau S, Taghibiglou C, Bradley C, Wong TP, Liu L, Lu J, Lo E, Wu D, Saule E, Bouschet T, Matthews P, Isaac JT, Bortolotto ZA, Wang YT, Collingridge GL. LTP inhibits LTD in the hippocampus via regulation of GSK3beta. Neuron. 2007;53(5):703–717. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gomez de Barreda E, Perez M, Gomez Ramos P, de Cristobal J, Martin-Maestro P, Moran A, Dawson HN, Vitek MP, Lucas JJ, Hernandez F, Avila J. Tau-knockout mice show reduced GSK3-induced hippocampal degeneration and learning deficits. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;37(3):622–629. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhu LQ, Wang SH, Liu D, Yin YY, Tian Q, Wang XC, Wang Q, Chen JG, Wang JZ. Activation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibits long-term potentiation with synapse-associated impairments. J Neurosci. 2007;27(45):12211–12220. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3321-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martin PM, Stanley RE, Ross AP, Freitas AE, Moyer CE, Brumback AC, Iafrati J, Stapornwongkul KS, Dominguez S, Kivimae S, Mulligan KA, Pirooznia M, McCombie WR, Potash JB, Zandi PP, Purcell SM, Sanders SJ, Zuo Y, Sohal VS, Cheyette BNR. DIXDC1 contributes to psychiatric susceptibility by regulating dendritic spine and glutamatergic synapse density via GSK3 and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(2):467–475. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Watcharasit P, Bijur GN, Zmijewski JW, Song L, Zmijewska A, Chen X, Johnson GV, Jope RS. Direct, activating interaction between glycogen synthase kinase-3beta and p53 after DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(12):7951–7955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122062299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang Z, Ge Y, Bao H, Dworkin L, Peng A, Gong R. Redox-sensitive glycogen synthase kinase 3beta-directed control of mitochondrial permeability transition: rheostatic regulation of acute kidney injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;65:849–858. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.08.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yazlovitskaya EM, Edwards E, Thotala D, Fu A, Osusky KL, Whetsell WO, Jr, Boone B, Shinohara ET, Hallahan DE. Lithium treatment prevents neurocognitive deficit resulting from cranial irradiation. Cancer Res. 2006;66(23):11179–11186. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cross DA, Culbert AA, Chalmers KA, Facci L, Skaper SD, Reith AD. Selective small-molecule inhibitors of glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity protect primary neurones from death. J Neurochem. 2001;77(1):94–102. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.t01-1-00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thotala DK, Hallahan DE, Yazlovitskaya EM. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta inhibitors protect hippocampal neurons from radiation-induced apoptosis by regulating MDM2-p53 pathway. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19(3):387–396. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rojo AI, Sagarra MR, Cuadrado A. GSK-3beta down-regulates the transcription factor Nrf2 after oxidant damage: relevance to exposure of neuronal cells to oxidative stress. J Neurochem. 2008;105(1):192–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wakatsuki S, Furuno A, Ohshima M, Araki T. Oxidative stress-dependent phosphorylation activates ZNRF1 to induce neuronal/axonal degeneration. J Cell Biol. 2015;211(4):881–896. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201506102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tobe BTD, Crain AM, Winquist AM, Calabrese B, Makihara H, Zhao WN, Lalonde J, Nakamura H, Konopaske G, Sidor M, Pernia CD, Yamashita N, Wada M, Inoue Y, Nakamura F, Sheridan SD, Logan RW, Brandel M, Wu D, Hunsberger J, Dorsett L, Duerr C, Basa RCB, McCarthy MJ, Udeshi ND, Mertins P, Carr SA, Rouleau GA, Mastrangelo L, Li J, Gutierrez GJ, Brill LM, Venizelos N, Chen G, Nye JS, Manji H, Price JH, McClung CA, Akiskal HS, Alda M, Chuang DM, Coyle JT, Liu Y, Teng YD, Ohshima T, Mikoshiba K, Sidman RL, Halpain S, Haggarty SJ, Goshima Y, Snyder EY. Probing the lithium-response pathway in hiPSCs implicates the phosphoregulatory set-point for a cytoskeletal modulator in bipolar pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(22):E4462–E4471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1700111114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wakatsuki S, Saitoh F, Araki T. ZNRF1 promotes Wallerian degeneration by degrading AKT to induce GSK3B-dependent CRMP2 phosphorylation. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(12):1415–1423. doi: 10.1038/ncb2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Polter A, Beurel E, Yang S, Garner R, Song L, Miller CA, Sweatt JD, McMahon L, Bartolucci AA, Li X, Jope RS. Deficiency in the inhibitory serine-phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 increases sensitivity to mood disturbances. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(8):1761–1774. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.de Sousa RT, Zanetti MV, Talib LL, Serpa MH, Chaim TM, Carvalho AF, Brunoni AR, Busatto GF, Gattaz WF, Machado-Vieira R. Lithium increases platelet serine-9 phosphorylated GSK-3beta levels in drug-free bipolar disorder during depressive episodes. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;62:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li X, Liu M, Cai Z, Wang G, Li X. Regulation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 during bipolar mania treatment. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(7):741–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00866.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kozlovsky N, Belmaker RH, Agam G. Low GSK-3beta immunoreactivity in postmortem frontal cortex of schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(5):831–833. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kozlovsky N, Regenold WT, Levine J, Rapoport A, Belmaker RH, Agam G. GSK-3beta in cerebrospinal fluid of schizophrenia patients. J Neural Transm. 2004;111(8):1093–1098. doi: 10.1007/s00702-003-0127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Beasley C, Cotter D, Everall I. An investigation of the Wnt-signalling pathway in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. Schizophr Res. 2002;58(1):63–67. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(01)00376-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ide M, Ohnishi T, Murayama M, Matsumoto I, Yamada K, Iwayama Y, Dedova I, Toyota T, Asada T, Takashima A, Yoshikawa T. Failure to support a genetic contribution of AKT1 polymorphisms and altered AKT signaling in schizophrenia. J Neurochem. 2006;99(1):277–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Klein PS, Melton DA. A molecular mechanism for the effect of lithium on development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(16):8455–8459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ryves WJ, Harwood AJ. Lithium inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3 by competition for magnesium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280(3):720–725. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Beaulieu JM, Sotnikova TD, Yao WD, Kockeritz L, Woodgett JR, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG. Lithium antagonizes dopamine-dependent behaviors mediated by an AKT/glycogen synthase kinase 3 signaling cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(14):5099–5104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307921101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dandekar MP, Valvassori SS, Dal-Pont GC, Quevedo J. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta as a putative therapeutic target for bipolar disorder. Curr Drug Metab. 2018;19(8):663–73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 87.Hur EM, Zhou FQ. GSK3 signalling in neural development. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11(8):539–551. doi: 10.1038/nrn2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Saraswati AP, Ali Hussaini SM, Krishna NH, Babu BN, Kamal A. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 and its inhibitors: potential target for various therapeutic conditions. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;144:843–858. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.11.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shim SS, Stutzmann GE. Inhibition of glycogen synthase Kinase-3: an emerging target in the treatment of traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2016;33(23):2065–2076. doi: 10.1089/neu.2015.4177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kozikowski AP, Gaisina IN, Yuan H, Petukhov PA, Blond SY, Fedolak A, Caldarone B, McGonigle P. Structure-based design leads to the identification of lithium mimetics that block mania-like effects in rodents. Possible new GSK-3beta therapies for bipolar disorders. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129(26):8328–8332. doi: 10.1021/ja068969w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kalinichev M, Dawson LA. Evidence for antimanic efficacy of glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) inhibitors in a strain-specific model of acute mania. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14(8):1051–1067. doi: 10.1017/S1461145710001495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Blackwood DH, Fordyce A, Walker MT, St Clair DM, Porteous DJ, Muir WJ. Schizophrenia and affective disorders--cosegregation with a translocation at chromosome 1q42 that directly disrupts brain-expressed genes: clinical and P300 findings in a family. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69(2):428–433. doi: 10.1086/321969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Millar JK, Christie S, Semple CA, Porteous DJ. Chromosomal location and genomic structure of the human translin-associated factor X gene (TRAX; TSNAX) revealed by intergenic splicing to DISC1, a gene disrupted by a translocation segregating with schizophrenia. Genomics. 2000;67(1):69–77. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Millar JK, Wilson-Annan JC, Anderson S, Christie S, Taylor MS, Semple CA, Devon RS, St Clair DM, Muir WJ, Blackwood DH, Porteous DJ. Disruption of two novel genes by a translocation co-segregating with schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9(9):1415–1423. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.9.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.St Clair D, Blackwood D, Muir W, Carothers A, Walker M, Spowart G, Gosden C, Evans HJ. Association within a family of a balanced autosomal translocation with major mental illness. Lancet. 1990;336(8706):13–16. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91520-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Taylor MS, Devon RS, Millar JK, Porteous DJ. Evolutionary constraints on the disrupted in schizophrenia locus. Genomics. 2003;81(1):67–77. doi: 10.1016/S0888-7543(02)00026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ma L, Liu Y, Ky B, Shughrue PJ, Austin CP, Morris JA. Cloning and characterization of Disc1, the mouse ortholog of DISC1 (disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1) Genomics. 2002;80(6):662–672. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.7012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lipska BK, Peters T, Hyde TM, Halim N, Horowitz C, Mitkus S, Weickert CS, Matsumoto M, Sawa A, Straub RE, Vakkalanka R, Herman MM, Weinberger DR, Kleinman JE. Expression of DISC1 binding partners is reduced in schizophrenia and associated with DISC1 SNPs. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(8):1245–1258. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chen CY, Liu HY, Hsueh YP. TLR3 downregulates expression of schizophrenia gene Disc1 via MYD88 to control neuronal morphology. EMBO Rep. 2017;18(1):169–183. doi: 10.15252/embr.201642586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Akbarian S, Kim JJ, Potkin SG, Hetrick WP, Bunney WE, Jr, Jones EG. Maldistribution of interstitial neurons in prefrontal white matter of the brains of schizophrenic patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(5):425–436. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830050061010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Glantz LA, Lewis DA. Decreased dendritic spine density on prefrontal cortical pyramidal neurons in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(1):65–73. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Brandon NJ, Handford EJ, Schurov I, Rain JC, Pelling M, Duran-Jimeniz B, Camargo LM, Oliver KR, Beher D, Shearman MS, Whiting PJ. Disrupted in schizophrenia 1 and Nudel form a neurodevelopmentally regulated protein complex: implications for schizophrenia and other major neurological disorders. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;25(1):42–55. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bradshaw NJ, Christie S, Soares DC, Carlyle BC, Porteous DJ, Millar JK. NDE1 and NDEL1: multimerisation, alternate splicing and DISC1 interaction. Neurosci Lett. 2009;449(3):228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.10.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kamiya A, Tan PL, Kubo K, Engelhard C, Ishizuka K, Kubo A, Tsukita S, Pulver AE, Nakajima K, Cascella NG, Katsanis N, Sawa A. Recruitment of PCM1 to the centrosome by the cooperative action of DISC1 and BBS4: a candidate for psychiatric illnesses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(9):996–1006. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.9.996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kirkpatrick B, Xu L, Cascella N, Ozeki Y, Sawa A, Roberts RC. DISC1 immunoreactivity at the light and ultrastructural level in the human neocortex. J Comp Neurol. 2006;497(3):436–450. doi: 10.1002/cne.21007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bradshaw NJ, Soares DC, Carlyle BC, Ogawa F, Davidson-Smith H, Christie S, Mackie S, Thomson PA, Porteous DJ, Millar JK. PKA phosphorylation of NDE1 is DISC1/PDE4 dependent and modulates its interaction with LIS1 and NDEL1. J Neurosci. 2011;31(24):9043–9054. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5410-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Flores R, 3rd, Hirota Y, Armstrong B, Sawa A, Tomoda T. DISC1 regulates synaptic vesicle transport via a lithium-sensitive pathway. Neurosci Res. 2011;71(1):71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chenn A, Walsh CA. Regulation of cerebral cortical size by control of cell cycle exit in neural precursors. Science. 2002;297(5580):365–369. doi: 10.1126/science.1074192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ishizuka K, Kamiya A, Oh EC, Kanki H, Seshadri S, Robinson JF, Murdoch H, Dunlop AJ, Kubo K, Furukori K, Huang B, Zeledon M, Hayashi-Takagi A, Okano H, Nakajima K, Houslay MD, Katsanis N, Sawa A. DISC1-dependent switch from progenitor proliferation to migration in the developing cortex. Nature. 2011;473(7345):92–96. doi: 10.1038/nature09859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kamiya A, Kubo K, Tomoda T, Takaki M, Youn R, Ozeki Y, Sawamura N, Park U, Kudo C, Okawa M, Ross CA, Hatten ME, Nakajima K, Sawa A. A schizophrenia-associated mutation of DISC1 perturbs cerebral cortex development. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7(12):1167–1178. doi: 10.1038/ncb1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ozeki Y, Tomoda T, Kleiderlein J, Kamiya A, Bord L, Fujii K, Okawa M, Yamada N, Hatten ME, Snyder SH, Ross CA, Sawa A. Disrupted-in-Schizophrenia-1 (DISC-1): mutant truncation prevents binding to NudE-like (NUDEL) and inhibits neurite outgrowth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(1):289–294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0136913100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Deng D, Jian C, Lei L, Zhou Y, McSweeney C, Dong F, Shen Y, Zou D, Wang Y, Wu Y, Zhang L, Mao Y. A prenatal interruption of DISC1 function in the brain exhibits a lasting impact on adult behaviors, brain metabolism, and interneuron development. Oncotarget. 2017;8(49):84798–84817. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Duff BJ, Macritchie KAN, Moorhead TWJ, Lawrie SM, Blackwood DHR. Human brain imaging studies of DISC1 in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression: a systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2013;147(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Eachus H, Bright C, Cunliffe VT, Placzek M, Wood JD, Watt PJ. Disrupted-in-Schizophrenia-1 is essential for normal hypothalamic-pituitary-interrenal (HPI) axis function. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26(11):1992–2005. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hennah W, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Paunio T, Ekelund J, Varilo T, Partonen T, Cannon TD, Lonnqvist J, Peltonen L. A haplotype within the DISC1 gene is associated with visual memory functions in families with a high density of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10(12):1097–1103. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hikida T, Gamo NJ, Sawa A. DISC1 as a therapeutic target for mental illnesses. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2012;16(12):1151–1160. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2012.719879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hu G, Yang C, Zhao L, Fan Y, Lv Q, Zhao J, Zhu M, Guo X, Bao C, Xu A, Jie Y, Jiang Y, Zhang C, Yu S, Wang Z, Li Z, Yi Z. The interaction of NOS1AP, DISC1, DAOA, and GSK3B confers susceptibility of early-onset schizophrenia in Chinese Han population. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;81:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Shao L, Lu B, Wen Z, Teng S, Wang L, Zhao Y, Wang L, Ishizuka K, Xu X, Sawa A, Song H, Ming G, Zhong Y. Disrupted-in-Schizophrenia-1 (DISC1) protein disturbs neural function in multiple disease-risk pathways. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26(14):2634–2648. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Terrillion CE, Abazyan B, Yang Z, Crawford J, Shevelkin AV, Jouroukhin Y, Yoo KH, Cho CH, Roychaudhuri R, Snyder SH, Jang MH, Pletnikov MV. DISC1 in astrocytes influences adult neurogenesis and Hippocampus-dependent behaviors in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42(11):2242–2251. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Tomoda T, Hikida T, Sakurai T. Role of DISC1 in neuronal trafficking and its implication in neuropsychiatric manifestation and Neurotherapeutics. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(3):623–629. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0556-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Devon RS, Anderson S, Teague PW, Burgess P, Kipari TM, Semple CA, Millar JK, Muir WJ, Murray V, Pelosi AJ, Blackwood DH, Porteous DJ. Identification of polymorphisms within disrupted in schizophrenia 1 and disrupted in schizophrenia 2, and an investigation of their association with schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder. Psychiatr Genet. 2001;11(2):71–78. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200106000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kockelkorn TT, Arai M, Matsumoto H, Fukuda N, Yamada K, Minabe Y, Toyota T, Ujike H, Sora I, Mori N, Yoshikawa T, Itokawa M. Association study of polymorphisms in the 5' upstream region of human DISC1 gene with schizophrenia. Neurosci Lett. 2004;368(1):41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Mathieson I, Munafo MR, Flint J. Meta-analysis indicates that common variants at the DISC1 locus are not associated with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(6):634–641. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Yang S, Cho YS, Chennathukuzhi VM, Underkoffler LA, Loomes K, Hecht NB. Translin-associated factor X is post-transcriptionally regulated by its partner protein TB-RBP, and both are essential for normal cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(13):12605–12614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313133200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Finkenstadt PM, Jeon M, Baraban JM. Trax is a component of the Translin-containing RNA binding complex. J Neurochem. 2002;83(1):202–210. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Chiaruttini C, Vicario A, Li Z, Baj G, Braiuca P, Wu Y, Lee FS, Gardossi L, Baraban JM, Tongiorgi E. Dendritic trafficking of BDNF mRNA is mediated by translin and blocked by the G196A (Val66Met) mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(38):16481–16486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902833106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Finkenstadt PM, Kang WS, Jeon M, Taira E, Tang W, Baraban JM. Somatodendritic localization of Translin, a component of the Translin/Trax RNA binding complex. J Neurochem. 2000;75(4):1754–1762. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Liu Y, Ye X, Jiang F, Liang C, Chen D, Peng J, Kinch LN, Grishin NV, Liu Q. C3PO, an endoribonuclease that promotes RNAi by facilitating RISC activation. Science. 2009;325(5941):750–753. doi: 10.1126/science.1176325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Asada K, Canestrari E, Fu X, Li Z, Makowski E, Wu YC, Mito JK, Kirsch DG, Baraban J, Paroo Z. Rescuing dicer defects via inhibition of an anti-dicing nuclease. Cell Rep. 2014;9(4):1471–1481. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]