Abstract

All lives contain negative events, but how we think about these events differs across individuals; negative events often include positive details that can be remembered alongside the negative, and the ability to maintain both representations may be beneficial. In a survey examining emotional responses to the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings, the current study investigated how this ability shifts as a function of age and individual differences in initial experience of the event. Specifically, this study examined how emotional importance (i.e., self-reported emotional arousal and personal significance), involvement (i.e., self and friend/family involvement in the 2013 Boston Marathon and self-involvement in prior marathons), and self-reported surprise upon hearing about the event related to the tendency to report focusing on the negative and positive aspects of the bombings. Structural equation models revealed that while greater emotional importance and surprise were associated with a greater focus on negative elements, involvement and age were associated with increased consideration of positive aspects. Further, emotional importance was more strongly related to an increased focus on negative aspects for young adults and an increased focus on positive aspects for older adults, highlighting a tendency for older adults to enhance positive features of an otherwise highly negative event.

Keywords: Emotion, Aging, Flashbulb Event, Arousal, Involvement

Introduction

Valence often is considered along a single dimension, ranging from high positive affect at one end to high negative affect at the other (e.g., Barrett & Russell, 1998; Green, Goldman, & Salovey, 1993). However, positive and negative affect may exist on independent scales that can be manipulated separately (e.g., Watson, Wiese, Vaidya, & Tellegen, 1999; Cacioppo & Bernston, 1994) and felt simultaneously. Highly negative events often include both positive and negative details, and the ability to maintain both representations can be beneficial to mental health by allowing individuals to enhance positive affect while experiencing the negative (Larsen, Hemenover, Norris, & Cacioppo, 2003).

For example, many individuals living in the Boston area have highly negative memories of when two bombs exploded at the finish line of the 2013 Boston Marathon. Yet this highly negative event contained related positive aspects: The week following the bombings were sprinkled with positive events as individuals learned about the heroes of the day, felt town pride and viewed signs of “Boston Strong”, and, ultimately, watched the successful capture of the suspect on live TV. This affective complexity meant that individuals could live through the same event and yet reflect on it in different ways.

The present study examines how age may influence the likelihood that an individual will report focusing on the positive aspects of this event. Age heightens focus on affective details of personal events (Comblain et al., 2004; Hashtroudi, Johnson, & Chosniak, 1990). Although this may lead to a greater experience of negative affect (Alea, Bluck, & Semegon, 2004; Levine & Bluck, 1997; Otani, et al., 2005), enhancement is often stronger for positive details (Carstensen & Mikels, 2005; Mikels, Larkin, Reuter-Lorenz, & Carstensen, 2005). For instance, a recent study (Ford, DiGirolamo & Kensinger, 2015) demonstrated that older adults use proportionally more positive words than young adults when describing a negative event.

Prior research also suggests that a person’s initial experience of a highly negative event will impact how such events are remembered. The degree of emotional arousal experienced (Conway et al., 2008; Petrician et al., 2008), perceived subjective significance (Curci et al., 2001; Lanciano et al., 2013; Er et al., 2003), personal relevance (Brown & Kulik, 1977), and surprise (Brown & Kulik, 1977) all can enhance memory for these negative events. However, no prior study has examined to what extent these variables separately enhance focus on positive and negative aspects or whether age moderates the impact of these factors. The current study used a self-report survey to investigate the independent effects of these measures, as well as their interactive effects with age, to understand what factors ultimately contribute to an increased ability to focus on the positive following a highly negative event.

Methods

Participants.

All participants who had indicated they would like to be contacted about future studies in our laboratory were mailed or e-mailed a survey 1–2 weeks after the Boston Marathon bombings occurred. The 267 surveys returned within a month of the bombings were analyzed here (Mage=54.82, SD=24.87, 19–85 years; Medu=16.24, SD=2.41, 12–21 years; 177 female; see Supplementary Figure 1 for age distribution). Participants were compensated $10 and consented in accordance with the requirements of the Institutional Review Board at Boston College.

Because this study took advantage of rapid data collection from as many participants in our laboratory database as possible, we did not establish an a priori sample size for this study. We included data from all participants who completed and returned their surveys within a month of the bombings, with no exclusions. We report the entire 20-page survey in the appendix, with the questions used in the current analysis in italics. The procedure and materials section (below) describes these questions and their relevance to the research questions.

Procedure & Materials

A one-hour survey asked participants about their memories for, and emotional reactions to, the Marathon bombings. Due to prior research suggesting memory-enhancing effects of arousal, significance, personal relevance, and surprise (Brown & Kulik, 1977; Conway et al., 2008; Curci et al., 2001; Er et al., 2003; Lanciano et al., 2013; Petrician et al., 2008), we focus on the subset of questions (in italics in the appendix) that allow us to examine these variables. Participants rated (on a scale of 1–7) the 1) emotional arousal, 2) surprise, and 3) overall significance attributed to the bombing. To assess the degree of personal involvement, participants reported their own involvement in the 2013 Boston Marathon, their involvement in prior Boston Marathons, and any friend or family involvement in the 2013 Marathon. These responses were coded as follows:

- Involvement in the 2013 Boston Marathon:

○ No involvement=0

○ Watched on television=1

○ Watched in person=2

○ Ran or volunteered=3

- Prior involvement in Boston Marathons:

○ No prior involvement=0

○ Previously watched on TV=1

○ Previously watched in person=2

○ Previously watched from the finish line, ran, or volunteered=3

- Friend or family member running in or volunteering for the 2013 Boston Marathon.

No=0

Yes=1

These measures—plus the participant’s age at the time of the survey—were the independent variables of interest in the current analysis.

The dependent variables of interest in the current analyses were participant ratings (using 7-point Likert scales) of the extent to which they have focused on the positive and negative aspects of the event since it occurred:

When I think of the marathon bombing, I think about the negative aspects – the hurt and devastation caused

When I think of the marathon bombing, I think about the positive aspects – the heroism and the way the city has come together

Similar ratings related to emotional responses to the city-wide lock-down or suspect capture were not included, as not all participants had memories for or reactions to these events.

Data Analysis.

Analyses examined how the variables discussed above contribute to the enhancement of positive and negative aspects of an event, and how the age of an individual might alter these relations. The six experience-related variables described above—emotional arousal, personal significance, 2013 self-involvement, prior self-involvement, 2013 friend/family involvement, and surprise—were entered into a Principal Components Analysis (PCA) to identify factors associated with positive or negative thoughts about the bombings. PCA was employed using a Promax rotation with Kaiser normalization due to the expectation that underlying latent variables were not orthogonal. This PCA produced three factors that are described below.

Two structural equation models (SEMs) were created and tested using LISREL 9.10 (http://www.ssicentral.com/lisrel/index.html). SEMs were utilized so that relations between predictor variables could be evaluated and estimated along with the relations between predictor and outcome variables. First, a model was created with the six observed experience-related variables (loading onto three factors identified using the PCA described above), age, and the observed ratings of focus on positive aspects and negative aspects. A correlation matrix was generated from the data of all 267 participants and entered into LISREL. Using this model, we examined the independent effects of the experience-related factors and age on participant ratings of the positive and negative aspects of the events, as well as the relation between these variables.

A second model examined how effects of the experience-related variables on positive and negative aspects may be moderated by age. To conduct this analysis within an SEM framework, interaction variables were generated by mean-centering all predictor variables and calculating the product of age and each of the 6 observed variables. A correlation matrix including age, the 6 original observed variables, and the 6 interaction variables was generated and entered into LISREL. The 6 new interaction variables were loaded onto new interaction factors, allowing us to evaluate the interactive effects by testing the paths from each new interaction factor to ratings of positive and negative aspects. If effects of age and the original experience-related variables are included in the model, a significant path from an interaction variable to an outcome variable indicates a moderating effect of age on the original variable.

To interpret the moderating effects of age on relevant relations, we compared the 92 youngest (ages 19–34) and 76 oldest (ages 76–85) in our sample. In these models, a correlation matrix including the original 6 observed experience-related variables was generated and entered into LISREL. Pathways exhibiting moderating effects of age in the prior analysis were examined to help determine the direction of the interaction.

Results

Relations between age and observed variables

Age was associated with increased significance (r=.14, p=.02) and arousal (r=.27, p<.001) and with decreased 2013 self-involvement (r=−.29, p<.001) and friend/family involvement (r=−.46, p<.001). There were no age differences in prior involvement (r=−.03, p=.61) nor surprise (r=−.08, p=.21). Age was associated with increased focus on negative (r=.41, p<.001) and positive (r=.17, p=.005) aspects. Descriptive statistics for all observed variables are presented in Supplementary Table 1; correlations between all observed variables are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

Effects of experience-related variables and age on emotional response

A PCA was utilized to identify three factors associated with an individual’s experience of the Marathon bombings from the six independent variables of interest. This analysis (see Supplementary Materials and Supplementary Tables 3 and 4) produced two latent variables that reflect measures of Emotional Importance (arousal and significance) and Involvement (2013 involvement, prior involvement, and friend/family involvement), and a third factor including just the observed surprise variable. An SEM examined the relations between these factors, age, and the two outcome variables (i.e., positive and negative aspects).

An initial model was generated examining the relation between our predictor variables (i.e., emotional importance, involvement, surprise, and age) and outcome variables (i.e., positive and negative aspects). Emotional importance was associated with increases in focus on both the positive (ϒ11=.25) and the negative (ϒ21=.45) aspects. Surprise was related to increases in only the negative aspects (ϒ23=.18). Involvement was associated with increases in the positive aspects (ϒ12=.24) and with decreased focus on the negative aspects (ϒ22= −.19). Age was associated with greater ratings of both positive (ϒ14=.21) and negative aspects (ϒ24=.28). However, this model had very poor fit [a Root Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) of above .1 (.141) and a significant discrepancy statistic (χ2(23, N=267)=145.87, p<.001]. Importantly, this model did not account for potential differences across the lifespan in initial experience variables. In other words, it did not account for the fact that young and older adults may differ in how they reported experiencing the bombings.

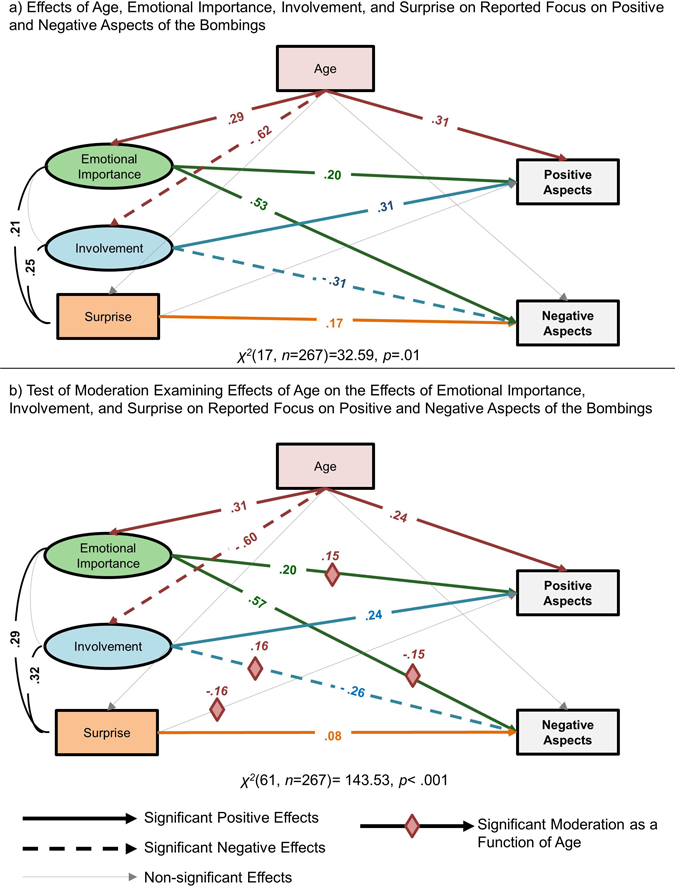

To account for the possibility that these relations would influence the effects of experience and age on emotional response, paths between age and all three initial experience variables were freed. In this model, older adults were more likely to report emotional importance (φ14=.29), but were less likely to be personally involved (φ24= - .62). The relation between age and surprise was insignificant (φ34= - .08). Emotional importance and involvement were not related (φ12=.10), but surprise was related to both emotional importance (φ13=.21) and involvement (φ23=.25). As before, emotional importance was associated with increases in focus on both the positive (ϒ11=.20) and the negative (ϒ21=.53) aspects. Surprise was related to increases in only the negative aspects (ϒ23=.17) with no relation with positive aspects (ϒ13=.05). Involvement was associated with increases in the positive aspects (ϒ12=.31) and with decreased focus on the negative aspects (ϒ22= −.31). Critically, when accounting for the relation between age and initial experience variables, age was associated with greater ratings of positive aspects only (ϒ14=.31), with the relation between age and negative aspects now insignificant (ϒ24=.08; Figure 1a and Table). This new model had an RMSEA of .06, indicating fit between good (.05) and mediocre (.08; MacCallum, Browne, & Sugawara, 1996), and the χ2 difference statistic [χ2diff (6, N=267)= 113.28, p<.001] reflected significant improvement (Supplementary Table 5).

Figure 1.

Visual representation of best-fitting models examining a) main effects of age, emotional importance, involvement, and surprise on reported focus on positive and negative aspects of the bombings and b) main effects as well as moderating effects of age on effects of emotional importance, involvement, and surprise on reported focus on positive and negative aspects of the bombings. Red= Significant effects of age; Green= Significant effects of Emotional Importance; Blue= Significant effects of Involvement; Orange= Significant effects of Surprise; Black= Significant covariance among predictor variables; Gray= Non-significant paths that were included in the model to improve overall fit. Solid lines depict positive effects while dotted lines depict negative effects. Red diamonds= Significant moderating effects of age. Ovals = Latent Variables; Rectangles = Observed Variables. Values represent model estimates of each significant effect. See table for full list of estimates.

Table.

Estimated paths among predictor variables and from predictor to outcome variables for all four estimated models.

|

Emotional

Importance |

Involvement | Surprise | Age |

Emotional

Importance X Age |

Involvement X Age |

Surprise X Age |

Negative Aspects |

Positive Aspects |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Importance | 1) 1.00 2) 1.00 3) 1.00 4) 1.00 |

1) 0.53 2) 0.57 3) 0.55 4) 0.50 |

1) 0.20 2) 0.20 3) −0.08 4) 0.46 |

||||||

| Involvement | 1) 0.10 2) 0.11 3) 0.45 4) −0.03 |

1) 1.00 2) 1.00 3) 1.00 4) 1.00 |

1) −0.31 2) −0.26 3) −0.60 4) −0.14 |

1) 0.31 2) 0.24 3) 0.46 4) 0.21 |

|||||

| Surprise | 1) 0.21 2) 0.29 3) 0.57 4) 0.02 |

1) 0.25 2) 0.32 3) 0.57 4) 0.08 |

1) 1.00 2) 1.98 3) 1.00 4) 1.00 |

1) 0.17 2) 0.08 3) 0.28 4) 0.18 |

1) 0.05 2) 0.06 3) 0.03 4) −0.18 |

||||

| Age | 1) 0.29 2) 0.31 3) na 4) na |

1) −0.62 2) −0.60 3) na 4) na |

1) −0.08 2) −0.07 3) na 4) na |

1) 1.00 2) 1.22 3) na 4) na |

1) 0.08 2) 0.02 3) na 4) na |

1) 0.31 2) 0.24 3) na 4) na |

|||

| Emotional Importance X Age |

1) na 2) 0.05 3) na 4) na |

1) na 2) ---- 3) na 4) na |

1) na 2) ---- 3) na 4) na |

1) na 2) −0.13 3) na 4) na |

1) na 2) 1.00 3) na 4) na |

1) na 2) −0.15 3) na 4) na |

1) na 2) 0.15 3) na 4) na |

||

| Involvement X Age | 1) na 2) ---- 3) na 4) na |

1) na 2) −0.41 3) na 4) na |

1) na 2) ---- 3) na |

1) na

2) 0.27 3) na 4) na |

1) na 2) 0.21 3) na 4) na |

1) na 2) 1.00 3) na 4) na |

1) na 2) 0.16 3) na 4) na |

1) na 2) −0.05 3) na 4) na |

|

| Surprise X Age | 1) na 2) ---- 3) na 4) na |

1) na 2) ---- 3) na 4) na |

1) na 2) 0.38 3) na 4) na |

1) na

2) 0.09 3) na 4) na |

1) na

2) 0.35 3) na 4) na |

1) na 2) 0.34 3) na 4) na |

1) na 2) 1.32 3) na 4) na |

1) na 2) 0.001 3) na 4) na |

1) na 2) −0.16 3) na 4) na |

1. Main Effects Model; 2. Interaction Model; 3. Young Adults Only; 4. Older Adults Only

na = Path not present in model (cannot be estimated);

---- = Path excluded from model because it did not improve fit (not estimated)

Moderating effects of age

To test interactive effects of age and initial experience, we tested a second model that included age, 3 interaction variables (e.g., Age-by-Surprise) in addition to the 3 parent initial experience variables (e.g., Surprise), and two observed outcome variables. A significant interactive effect is represented by a significant path from an interaction variable in a model that also estimates paths from the two parent variables.

An initial model was generated that estimated all of the pathways from the final main effects model (reported above). All effects were the same as in the prior model but this model fit poorly (χ2(76, N=267)=266.62, p< .001; RMSEA=.10). To examine the potential interactive effects of age and the initial experience variables on positive and negative aspects, a second model was generated that estimated the paths between interaction variables and emotional aspects outcome variables, and freed the relations among interaction variables and between interaction variables and their parent variables. The final model (Figure 1b and Table) was associated with a significant improvement in fit [χ2diff (15, N=267)=123.09, p<.001; Supplementary Table 5] with an RMSEA of .07, indicating fit between good (.05) and mediocre (.08; MacCallum, Browne, & Sugawara, 1996). The main effects of age and parent latent variables on outcome measures replicated the prior findings: Age (ϒ14=.24, emotional importance (ϒ11=.20), and involvement (ϒ12=.24) were associated with increased focus on positive aspects; emotional importance (ϒ21=.57) and surprise (ϒ13=.08) were associated with increased focus on negative aspects, and involvement was associated with decreased focus on negative aspects (ϒ12= - .26).

The effect of emotional importance on positive aspects was subject to a significant moderating effect of age (ϒ15=.15), while the effect of emotional importance on negative aspects was subject to a significant negative moderating effect of age (ϒ25= −.15). Independent models tested in the youngest (n=92) and oldest (n=76) participants revealed that the relation between emotional importance and positive aspects was significant in older adults (ϒ11=.46), but not in young (ϒ21= −.08). The relation between emotional importance and negative aspects was significant in both OA (ϒ11=.50) and YA (ϒ11=.55), but the interaction suggests that it was greater for young adults. Although there was not a significant effect of surprise on positive aspects, there was a significant negative moderating effect of age (ϒ17= −.16) suggesting a greater effect in young relative to older adults. Finally, age modulated the negative effect of involvement on negative aspects (ϒ27= .16); this negative effect of involvement was significant in young adults (ϒ12= −.60) but not in old (ϒ22= −.14; Figure 1b and Table; Scatterplots depicting all interactions are in Supplementary Figure 2).

Discussion

Even in the darkest moments, there often are silver linings. The present study was interested in how individual differences influenced the ability to focus on these silver linings following a highly negative event. Our findings reveal that the likelihood of focusing on positive aspects is related to a person’s initial involvement in and emotional reaction to an event, but also to a person’s age.

Prior research suggests that emotional arousal (Conway et al., 2008; Petrician et al., 2008), significance (Curci et al., 2001; Lanciano et al., 2013; Er et al., 2003), personal relevance (Brown & Kulik, 1977), and surprise (Brown & Kulik, 1977) may enhance memory for negative events. The current study extends this research by exploring which elements of these events are being enhanced. Emotional importance was associated with increased reporting of both the positive and the negative aspects, consistent with an overall emotional memory enhancement. It is notable that these relations were both moderated by age (see below), suggesting that emotional importance does not influence all memories equally. Surprise was associated with an increased focus on negative aspects, only. This finding may reflect a tendency for individuals to focus on the central details of highly shocking events (e.g., Berntsen, 2002), as the central components of the bombings were the most negative. Of interest, greater involvement was related to increased consideration of the positive aspects rather than the negative. This was an unexpected finding, as no prior study has looked at how these factors specifically affect the positive details of highly negative memories. As such, future work is needed to consider the types of positive details being retrieved by these individuals and the extent to which participants have intentionally focused on these details to cope with the bombings. It is possible that the effect of involvement could reflect either a coping mechanism to deal with a tragedy that hit so close to home or the fact that these individuals had more positive associations with the marathon to begin with, and thus had more positive features to consider in subsequent days.

Central to our research question, the age of the participant also influenced their affective focus. Increased age was associated with reports of a greater focus on the positive aspects of this otherwise highly negative event. This result is consistent with prior evidence that older adults use proportionally more positive words to describe negative memories than do young adults (Ford et al., 2015), suggesting that older adults may be more likely than young to think about the silver linings of negative life events. Of note, this age-related increase in positive focus remained significant even when controlling for age differences in emotional importance and involvement. Focus on negative features, on the other hand, was not significantly related to age when associations with these initial experience variables were taken into account, suggesting that age-related increases in focus on the negative aspects were mainly due to age differences in initial experience. This age-by-valence interaction in focus ratings is consistent with an age-related positivity effect in which older adults tend to focus more on positive elements in their environments and in memory (e.g., Reed et al., 2012).

Some further insight into a potential positivity enhancement in older adults is provided by the significant age-by-emotional importance interaction for positive information. Greater reported emotional importance was associated with increased ratings of focusing on the positive elements in older but not younger adults, potentially explaining why controlling for this initial experience variable did not reduce the age effect. Emotional importance was associated with an increased focus on negative aspects for both young and older adults, although a significant interaction suggests that this effect was stronger in young adults. Together, these findings highlight an age-related increase in older adults’ engagement with positive information when thinking about highly negative events. It is possible that such an increased focus on the positive may help older adults to, over time, reappraise their personal memories to become more positive (see Kennedy et al., 2004), although future work is needed to examine whether focus on these silver linings contributes to more positive memories in older adults, more generally.

The current study is limited by its reliance on a single outcome measure for focus on positive and negative aspects. A diary method that could track this information over days and weeks after the event would be preferable. Given the surprise nature of this event, however, such a method was impossible to implement within a reasonable timeframe after the bombings. A second limitation of the current study is the collection of measures intended to capture a participant’s “initial” experience of the bombings and their subsequent emotional response in the same survey. Because these data were collected at the same time, it is possible that participants’ focus on emotional aspects in the subsequent weeks caused them to misremember their initial response. Due to this possibility, we primarily focus on the effects of aging on emotional focus, mainly highlighting the effects of these initial experience variables as they relate to aging.

Despite these limitations, the current study provides insight into how individuals can experience the same negative event and yet reflect on it in different ways, and it begins to elucidate the factors that predict these differences. The results emphasize that event involvement and experience can influence the affective focus and that age can—both independently and through its interactions with initial experience—increase the focus on positive details of an otherwise highly negative event. Such age-related changes could have downstream effects on older adults’ ability to reappraise such memories in a more positive way over time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to thank Tala Berro, Maria Box, Marissa DiGirolamo, and Katherine Grisanzio for their help collecting and analyzing data for this project. We would also like to thank Dr. Ehri Ryu for her advice on the structural equation model analysis. This work was supported by NIH grant MH080833 (EAK) and by funding from Boston College.

APPENDIX

MEMORY SURVEY-TIME 1

This survey will ask about your thoughts and memories from two recent events: The 2013 Boston marathon bombings and an event of your choosing that took place during School Vacation Week or around the Easter and Passover holidays. You may skip any questions you do not wish to answer, although we hope that you will answer all questions. Any and all information collected in this study will be kept confidential and you should not include your name on this survey.

Please answer each question to the best of your knowledge as completely as possible. If you do not know/remember the answer to a question, please indicate so. Do NOT ask someone else for the answer. If you have any questions regarding this survey, you may contact the research staff of the Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience laboratory at 617–552-6949.

General Questions

Today’s date: _____________________

Your age: _____________________

Your gender: _____________________

Ethnic Background

Hispanic

Not Hispanic

Prefer not to answer

Racial Background (circle the most appropriate letter)

American Indian or Alaskan Native

Asian or Pacific Islander

African-American, Black (not Hispanic origin)

Caucasian, White (not Hispanic origin)

Other

Prefer not to answer

Education (circle highest grade/year completed)

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 | 7 8 9 10 11 12 | 13 14 15 16 | 17 18 19 20 20+ |

| (grade school) | (high school) | (college) | (graduate training) |

Are you presently (circle all the apply)

Employed full-time

Employed part-time

Retired

Full-time student

Part-time student

What is the zip code in which you live? _____________________

If you are employed, what is the zip code in which you work (or the city/neighborhood if you do not know the zip code – e.g., South Boston)? _____________________

If you are a student, what is the zip code of your school? ___________________

QUESTIONS BELOW REFER TO THE 2013 BOSTON MARATHON

Have you previously watched the Boston marathon (circle all that apply)?

| No | Yes, on TV | Yes, in person | Yes, from the finish line |

If Yes, please indicate most recent prior year you watched the Boston marathon (include an answer for both on TV and in person, if applicable) ____________

If Yes, please indicate the approximate number of years you have watched the Boston marathon ____________

Were you watching the Boston marathon this year (circle all that apply)?

| No | Yes, on TV | Yes, in person |

If Yes, where were you (what part of city) when the bombings occurred?

_______________________________________________________________________

Have you previously run in, or volunteered for, the Boston marathon (circle all that apply)?

| No | Yes, as runner | Yes, as volunteer |

If Yes, please indicate most recent prior year you participated in the Boston marathon or volunteered for the marathon (indicate which) ____________

If Yes, please indicate the approximate number of years you have participated in the Boston marathon ____________

Have you previously run in, or volunteered for, another marathon (circle all that apply)?

| No | Yes, as runner | Yes, as volunteer |

If Yes, please indicate most recent prior year you ran in or volunteered for the marathon (indicate which) ____________

If Yes, please indicate the approximate number of years you have participated in the marathon ____________

Were you participating in the marathon this year?

| No | Yes, as runner | Yes, as volunteer |

If Yes, where were you (what part of city) when the bombings occurred? ____________

_______________________________________________________________________

Did you have any relatives or close friends participating in the marathon this year?

| No | Yes, family member | Yes, friend |

If Family Member, please indicate relation of the person participating_______________

Did you have any relatives or close friends watching the marathon from the finish line?

| No | Yes, family member | Yes, friend |

If Family Member, please indicate relation of the person watching________________

Were you able to feel or hear the marathon bombings from your location (circle one)?

| Yes | No |

Were you able to hear the shots and explosions associated with suspect #1’s death from your location (circle one)?

| Yes | No |

Were you able to hear the shots leading up to suspect #2’s capture from your location (circle one)?

| Yes | No |

How did you learn of the bombings (please briefly describe; e.g., on TV, from text message, social media etc)?

Who were you with when you learned of the bombings?

What time did you learn about the bombing?

How did you learn of the “shelter-in-place” ordinance (please briefly describe; e.g., on TV, from text message, social media etc)?

Who were you with when you learned of the “shelter-in-place” ordinance?

What time did you learn about the “shelter-in-place” ordinance?

How did you learn of suspect #2’s capture (please briefly describe; e.g., on TV, from text message, social media etc)?

Who were you with when you learned of suspect #2’s capture?

What time did you learn about suspect #2’s capture?

How many people were initially reported injured and killed in the bombings (be as specific as you remember)?

What is the current estimate of number of people reported injured and killed in the bombings (be as specific as you remember)?

What were the initial cities included in the shelter-in-place ordinance?

What additional cities were included in the lock-down over the course of the day?

What transportation changes took place the day of the bombing because of safety concerns?

What hotels or other areas were evacuated?

Before the two suspects were identified, what was correctly or incorrectly reported about who is responsible for the bombings?

What has been discussed about potential, additional "incendiary devices"? Please indicate what is now known to be true vs. false, and what is still uncertain.

What has been discussed about the JFK library? Please indicate what is now known to be true vs. false, and what is still uncertain.

What has been discussed about cell phone service being shut down? Please indicate what is now known to be true vs. false, and what is still uncertain.

During the week following the bombings, how did you get additional news (please circle all that apply and indicate the extent to which each was used)?

| Very Rarely | Occasionally | Very Frequently | |

| Television | 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | ||

| Friends and family (includes phone or email) | 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | ||

| Social Media | 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | ||

| Radio | 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | ||

| Police Scanner | 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | ||

| Other (please specify:____________ | 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | ||

Are you on Facebook (circle one; if No, skip to the next question)?

| No | Yes |

If Yes, what were your friends posting (please briefly describe; e.g. information, personal stories, emotional support for people in Boston, etc)? Were these posts primarily positive (e.g., stories of heroics or human strength) or negative (e.g., anger at the bomber or fear)?

If Yes, did you post on Facebook about the bombings?

| No | Yes |

If Yes, what did you post (please briefly describe; e.g. information, personal stories, emotional support for people in Boston, etc)?

Are you on Twitter (circle one; if No, skip to the next question)?

| No | Yes |

If Yes, what were your friends tweeting (please briefly describe; e.g. information, personal stories, emotional support for people in Boston, etc)? Were these tweets primarily positive (e.g., stories of heroics or human strength) or negative (e.g., anger at the bomber or fear)?

If Yes, did you tweet about the bombings?

| No | Yes |

If Yes, what did you tweet (please briefly describe; e.g. information, personal stories, emotional support for people in Boston, etc)?

What was the content of phone calls and emails that you received immediately after the bombings (please briefly describe; e.g. information, personal stories, emotional support for people in Boston, etc)? Was this information primarily positive (e.g., stories of heroics or human strength) or negative (e.g., anger at the bomber or fear)?

What were some of the stories of heroism and helping that you remember from the day of the bombing (give a brief description of any you remember)?

What were some of the stories of heroism and helping that you remember from the day of the lock-down (give a brief description of any you remember)?

When you think about the week following the bombings, what are the first three images that come to mind?

1.

2.

3.

Are these images you saw at the time the event occurred or images that you have seen since the time of the event (e.g., photos or video footage)? Where did you initially see these images?

Did watching this event make you think of other events from your past (please describe)?

Please use the space below to share any other information you would like about what you remember about these events

We will now ask you some specific questions about the marathon bombings, the lock-down, and suspect #2’s capture.

How well do you think you will remember the details of the marathon bombings in 5–6 months?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| will remember very little | will remember everything |

How well do you think you will remember the details of the lock-down in 5–6 months?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| will remember very little | will remember everything |

How well do you think you will remember the details of suspect #2’s capture in 5–6 months?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| will remember very little | will remember everything |

What was the intensity of your emotional reaction to the marathon bombings?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| little reaction | very intense |

What was the intensity of your emotional reaction to the lock-down?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| little reaction | very intense |

What was the intensity of your emotional reaction to suspect #2’s capture?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| little reaction | very intense |

What was your emotional reaction to the marathon bombings?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| extremely negative | extremely positive |

What was your emotional reaction to the lockdown?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| extremely negative | extremely positive |

What was your emotional reaction to suspect #2’s capture?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| extremely negative | extremely positive |

To what extent did you feel in imminent personal danger during the day of the marathon bombings?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| no personal danger | extreme personal danger |

To what extent did you feel in imminent personal danger during the days following the marathon bombings?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| no personal danger | extreme personal danger |

To what extent did you feel in imminent personal danger during the lock-down?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| no personal danger | extreme personal danger |

How significant was the marathon bombing to you personally?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| Mildly significant | extremely significant |

How significant was the lock-down to you personally?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| Mildly significant | extremely significant |

How significant was suspect #2’s capture to you personally?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| Mildly significant | extremely significant |

In your opinion, how significant was the marathon bombing to the city of Boston?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| Mildly significant | extremely significant |

In your opinion, how significant was the lock-down to the city of Boston?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| Mildly significant | extremely significant |

In your opinion, how significant was suspect #2’s capture to the city of Boston?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| Mildly significant | extremely significant |

In your opinion, how significant was the marathon bombing to the nation?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| Mildly significant | extremely significant |

In your opinion, how significant was the lock-down to the nation?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| Mildly significant | extremely significant |

In your opinion, how significant was suspect #2’s capture to the nation?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| Mildly significant | extremely significant |

How surprising was the marathon bombing to you?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| mildly surprising | extremely surprising |

How surprising was the lock-down to you?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| mildly surprising | extremely surprising |

How surprising was suspect #2’s capture to you?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| mildly surprising | extremely surprising |

When I think of the marathon bombing, I think about the negative aspects -- the harm and devastation caused

| 1.........2.........3..........4..........5..........6...........7 | |

| entirely untrue | entirely true |

When I think of the marathon bombing, I think about the positive aspects -- the heroism, the way the city has come together

| 1.........2.........3..........4..........5..........6...........7 | |

| entirely untrue | entirely true |

When I think of the lock-down, I think about the negative aspects -- the anxiety and the sense of fear in the city

| 1.........2.........3..........4..........5..........6...........7 | |

| entirely untrue | entirely true |

When I think of the lock-down, I think about the positive aspects -- the heroism of police officers, the way the city has come together

| 1.........2.........3..........4..........5..........6...........7 | |

| entirely untrue | entirely true |

When I think of suspect #2’s capture, I think about the negative aspects – the violence, the destruction

| 1.........2.........3..........4..........5..........6...........7 | |

| entirely untrue | entirely true |

When I think of suspect #2’s capture, I think about the positive aspects -- the heroism of police officers, the patriotism and city pride

| 1.........2.........3..........4..........5..........6...........7 | |

| entirely untrue | entirely true |

When I think of the week of the marathon bombings, I feel more connected to others in the Boston area

| 1.........2.........3..........4..........5..........6...........7 | |

| entirely untrue | entirely true |

How frequently have you thought about the week of the marathon bombing?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | ||

| Very Rarely | Occasionally | Very Frequently |

My memories of the week of the marathon bombing often occur automatically or involuntarily

| 1.........2.........3..........4..........5..........6...........7 | |

| entirely untrue | entirely true |

I have found it hard to stop thinking about the events surrounding the marathon bombing

| 1.........2.........3..........4..........5..........6...........7 | |

| entirely untrue | entirely true |

When I think of the week of the marathon bombings, details come to me in visual flashes

| 1.........2.........3..........4..........5..........6...........7 | |

| entirely untrue | entirely true |

When I think of the week of the marathon bombings, details come to me as part of a narrative

| 1.........2.........3..........4..........5..........6...........7 | |

| entirely untrue | entirely true |

I have had a dream(s) related to the events surrounding the marathon bombing

| 1.........2.........3..........4..........5..........6...........7 | |

| entirely untrue | entirely true |

When I think of one of the events surrounding the marathon bombing, I naturally lump them together—memory of one event naturally leads to memory of other events

| 1.........2.........3..........4..........5..........6...........7 | |

| entirely untrue | entirely true |

Selecting from the list of emotion words below, what were the THREE main emotions that were generated for you by the marathon bombing?

| ______ | inactive | ______ | happy | ______ | amused |

| ______ | energetic | ______ | distressed | ______ | pleasant |

| ______ | gloomy | ______ | anxious | ______ | relaxed |

| ______ | cheerful | ______ | enthusiastic | ______ | interested |

| ______ | excited | ______ | worried | ______ | sad |

| ______ | afraid | ______ | angry | ______ | nervous |

| ______ | calm | ______ | unpleasant | ______ | aroused |

| ______ | confused | ______ | shocked | ______ | disappointed |

Selecting from the list of emotion words below, what were the THREE main emotions that were generated for you by the lock-down?

| ______ | inactive | ______ | happy | ______ | amused |

| ______ | energetic | ______ | distressed | ______ | pleasant |

| ______ | gloomy | ______ | anxious | ______ | relaxed |

| ______ | cheerful | ______ | enthusiastic | ______ | interested |

| ______ | excited | ______ | worried | ______ | sad |

| ______ | afraid | ______ | angry | ______ | nervous |

| ______ | calm | ______ | unpleasant | ______ | aroused |

| ______ | confused | ______ | shocked | ______ | disappointed |

Selecting from the list of emotion words below, what were the THREE main emotions that were generated for you by suspect #2’s capture?

| ______ | inactive | ______ | happy | ______ | amused |

| ______ | energetic | ______ | distressed | ______ | pleasant |

| ______ | gloomy | ______ | anxious | ______ | relaxed |

| ______ | cheerful | ______ | enthusiastic | ______ | interested |

| ______ | excited | ______ | worried | ______ | sad |

| ______ | afraid | ______ | angry | ______ | nervous |

| ______ | calm | ______ | unpleasant | ______ | aroused |

| ______ | confused | ______ | shocked | ______ | disappointed |

QUESTIONS ABOUT AN EVENT OF YOUR CHOOSING

Please think of an event that happened within one month of the marathon - perhaps an event during School Vacation Week, or during Easter or Passover. The event should have occurred at a specific time, in a specific place, and lasted for a day or less. Examples of good events might be a visit with family members, a dinner party with friends, etc.

Brief Description of Event:

THE QUESTIONS BELOW REFER TO THIS EVENT THAT YOU HAVE CHOSEN:

Where were you during this event?

What time did this event take place?

Who were you with during this event?

Please use the space below to share any other information you would like about what you remember about this event

How well do you think you will remember the details of this event in 5–6 months?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| will remember very little | will remember everything |

What was the intensity of your emotional reaction to this event?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |

| little reaction | very intense |

How negative was your emotional reaction to this event?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | |||

| Very negative | neither negative | very positive | or positive |

How important is this event for you personally?

| 0……...1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | ||

| not at all | Mildly important | extremely important |

In your opinion, how important is this event for the city of Boston?

| 0……...1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | ||

| not at all | Mildly important | extremely important |

In your opinion, how important is this event for the nation?

| 0……...1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | ||

| not at all | Mildly important | extremely important |

How surprising was this event for you?

| 0……...1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | ||

| not at all | Mildly important | extremely important |

How frequently have you thought about this event since it occurred?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | ||

| Very Rarely | Occasionally | Very Frequently |

How frequently have you viewed social media posts about this event since it occurred?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | ||

| Very Rarely | Occasionally | Very Frequently |

How frequently have you spoken about this event since it occurred?

| 1……….2……….3……….4……….5……….6……….7 | ||

| Very Rarely | Occasionally | Very Frequently |

Overall, what were the THREE main emotions that were generated for you by this event?

| ______ | inactive | ______ | happy | ______ | amused |

| ______ | energetic | ______ | distressed | ______ | pleasant |

| ______ | gloomy | ______ | anxious | ______ | relaxed |

| ______ | cheerful | ______ | enthusiastic | ______ | interested |

| ______ | excited | ______ | worried | ______ | sad |

| ______ | Afraid | ______ | angry | ______ | nervous |

| ______ | calm | ______ | unpleasant | ______ | aroused |

| ______ | confused | ______ | shocked | ______ | disappointed |

Thank you very much for completing this survey during a very difficult time.

We would like to contact you in a few months to ask you to fill out a similar survey once more time has passed. Please circle the best way for us to contact you. We will detach the identifying information from the rest of the survey once we receive your paperwork so that no identifying information will be kept associated with your responses.

Mailing (address: ___________________________________________________)

Phone (number: _________________________)

Email (Email address: ______________________________)

Do NOT contact me again to complete a follow-up survey.

References

- Alea N, Bluck S, & Semegon AB (2004). Young and older adults’ expression of emotional experience: Do autobiographical narratives tell a different story? Journal of Adult Development, 11(4), 235–250. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF, & Russell JA (1998). Independence and bipolarity in the structure of current affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 967–984. [Google Scholar]

- Berntsen D (2002). Tunnel memories for autobiographical events: Central details are remembered more frequently from shocking than from happy experiences. Memory & Cognition, 30, 1010–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R & Kulik J (1977). Flashbulb memories, Cognition, 5, 73–99. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, & Berntson GG (1994). Relationship between attitudes and evaluative space: A critical review, with emphasis on the separability of positive and negative substrates. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 401–423. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL & Mikels JA (2005). At the intersection of emotion and cognition. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 117–121 [Google Scholar]

- Comblain C, Van der Linden M, & Aldenhoff L (2004). The effect of ageing on the recollection of emotional and neutral pictures. Memory, 12, 673–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway R, Skitka L, Hemmerich J, Kershaw T (2008). Flashbulb memory for 11 September 2001. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 23, 605–623. [Google Scholar]

- Curci A, Luminet O, Finkenauer C, & Gisle L (2001). Flashbulb memories in social groups: A comparative test/retest study of the memory of French President Mitterrand’s death in a French and a Belgian group. Memory, 9:2, 81–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Er N (2003). A new flashbulb memory model applied to the Marmara earthquake. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 17(5), 503–517. [Google Scholar]

- Ford JH, DiGirolamo M, & Kensinger EA (in press). Healthy Aging Influences the Relation between Subjective Valence Ratings and Emotional Word Use during Autobiographical Memory Retrieval. Memory [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DP, Goldman SL, & Salovey P (1993). Measurement error masks bipolarity in affect ratings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 1029–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashtroudi S, Johnson MK, & Chrosniak LD (1990). Aging and qualitative characteristics of memories for perceived and imagined complex events. Psychology and Aging, 5, 119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy Q, Mather M, & Carstensen LL (2004). The role of motivation in the age-related positivity effect in autobiographical memory. Psychological Science, 15, 208–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanciano T, Curci A, Soleti E (2013). “I knew it would happen .. and I remember it!”: The flashbulb memory for the death of Pope John Paul II. Europe’s Journey of Psychology, 9(2), 220–230. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen JT, Hemenover SH, Norris CJ, & Cacioppo JT (2003). Turning adversity to advantage: On the virtues of the coactivation of positive and negative emotions In Aspinwall LG & Staudinger UM (Eds.), A psychology of human strengths: Perspectives on an emerging field (pp. 211–216). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Levine LJ, & Bluck S (1997). Experienced and remembered emotional intensity in older adults. Psychology and Aging, 12, 514–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW, & Sugawara HM (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1, 130–149. [Google Scholar]

- Mikels JA, Larkin GR, Reuter-Lorenz PA, & Carstensen LL (2005). Divergent trajectories in the aging mind: Changes in working memory for affective versus visual information with age. Psychology and Aging, 20, 542–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otani H, Kusumi T, Kato K, Matsuda K, Kern RP, Widner R Jr., & Ohta N (2005). Remembering a nuclear accident in Japan: did it trigger flashbulb memories? Memory, 13, 6–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrician R, Moscovitch M, & Ulrich S (2008). Cognitive resources, valence, and memory retrieval of emotional events in older adults. Psychology And Aging, 23(3), 585–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed AE, & Carstensen LL (2012). The theory behind the age-related positivity effect. Frontiers in Psychology, 3(339), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Wiese D, Vaidya J, & Tellegen A (1999). The two general activation systems of affect: Structural findings, evolutionary considerations, and psychobiological evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 820–838. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.