Abstract

Background:

Breast cancer is a great concern for women’s health; early detection can play a key role in reducing associated morbidity and mortality. The objective of this study was to systematically assess the effectiveness of model-based interventions for breast cancer screening behavior of women.

Methods:

We searched Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science, Science Direct, Cochrane library and Google scholar search engines for systematic reviews, clinical trials, pre- and post-test or quasi-experimental studies (with limits to publication dates from 2000-2017), Keywords were: breast cancer, screening, systematic review, trials, and health model. In this review, qualitative analysis was used to assess the heterogeneity of data.

Results:

Thirty six articles with 17,770 female participants were included in this review. The Health belief model was used in twenty three articles as the basis for intervention. Two articles used both the Health belief model and the Health Promotion Model, 5 articles used Health belief model and The Trans theoretical Model, 2 used Hthe ealth belief model and Theory planned behavior, 2 used the Health belief model and the Trans theoretical Model, 2 used the Trans theoretical Model, 1 used social cognitive theory, and 1 used Systematic Comprehensive Health Education and Promotion Model. The results showed that model-based educational interventions are more effective for BSE and CBE and mammography screening behavior of women compare to no model based intervention. The Health belief model was the most popular model for promoting breast cancer screening behavior.

Conclusions:

Educational model-based interventions promote self-care and create a foundation for improving breast cancer screening behavior of women and increase policy makers’ awareness and efforts towards its enhancement breast cancer screening behavior.

Keywords: Breast cancer, health, model, screening, systematic review, women

Introduction

Breast cancer is a prevalent disease of women (Abolfotouh et al., 2015) and also a public concern that threaten lives of women (Nergiz-Eroglu and Kilic, 2010). It is anticipated that more than one million new cases of breast cancer occurs annually worldwide (Shiryazdi et al., 2014). Early detection of women’s breast cancer leads to increase their survival rates after diagnosis and reduces the related mortality (İz and Tümer, 2016; Ardahan et al., 2015). So, promotion of breast cancer screening behavior decreases breast cancer morbidity and mortality through early diagnosis of the disease (Arrospide et al., 2015).There are three ways for breast cancer screening including: breast self-examination, clinical examination by medical personnel, and mammography (Calonge et al., 2009).

Several factors including: type of medical insurance of women and women’s employment status (Tsunematsu et al., 2013), history of breast disease and familial history of BC (breast cancer) (Allahverdipour et al., 2011), low knowledge and breast cancer literacy (Talley et al., 2016), are shown to be effective on breast cancer screening behavior of women.

Health beliefs of women impact on their breast cancer screening approach (Ersin et al., 2015) such as concerns about breast cancer (Hay et al., 2006), low perceived susceptibility (Petro-Nustas et al., 2013), low motivation, perceived benefits and self-efficacy (Hajian-Tilaki and Auladi, 2014), lack of perceived benefit, low motivation for performing breast cancer screening (Veena et al., 2015, Dündar et al., 2006) are known to be barriers of screening behaviors (Tavafian et al., 2009), Overcoming these barriers and increasing perceived self-efficacy and motivation are important to promote breast cancer screening behavior among women (Noroozi and Tahmasebi, 2011).

Theoretical models identified the factors that underlie health behaviors (Noar and Zimmerman, 2005), comprehensive integrative psychosocial models, are an essential first step for enhancing health behavior (Reid and Aiken, 2011). Some evidence indicated that interventions which used for promotion of health based on behavioral theories are more effective than those without a theoretical base (Glanz and Bishop, 2010). Different models for health change behavior were the base of interventions to promote breast cancer screening behaviors (Ashing-Giwa, 1999). Educational cancer prevention program is very cost-effectiveness program which empower people to give preventive behaviors (Changizi and Kaveh, 2017). Evidence showed that education about breast cancer prevention methods can improve BCS behavior of women (Levano et al., 2014).

There is lack of any review on model based educational interventions for promoting breast cancer screening behavior (O’Mahony et al., 2017). This study aims to review the application of health behavior model-based educational interventions for promoting breast cancer screening behavior of women. Hopefully, the review could help to plan effective model based future strategies to improve screening behavior of women and consequently reduce mortality and morbidity of breast cancer among women.

Materialds and Methods

Search Strategy

This study is a systematic review to determine the effects of model-based interventions to improve Breast cancer screening behavior (BCS) of women. All published articles (RCT, pre- and post-test design or quasi-experimental) were assessed from July 2000 to March 2017 in English language. We searched from databases including Scopus, PubMed, Science Direct, Cochrane library and Google scholar search engine. The search was based on the following keywords: breast cancer, screening, health belief model, health promotion model, social cognitive theory, theory of planned behavior, Trans theoretical Model, PRECEDE-PROCEED model, Systematic Comprehensive Health Education and Promotion Model. Therefore, articles were limited to date 2000 – 2017.

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Selection of studies

Two authors reviewed the eligibility of all included articles and also evaluated the risk of bias and the data for included articles such as country of origin, information on demographic characteristics of participants of the study, the number of participants in each group, aim of study, design and duration of study, measurement tools, adverse effect of each intervention and the type of educational intervention and main results of study were extracted. All studies based on different models for their educational programs for breast cancer screening were considered as the inclusion criteria for the study. All the trials used a standard, valid and reliable questionnaire for measuring the breast cancer screening behavior of women.

Types of Participants

All clinical trials (RCT, pre- and post-test or quasi-experimental) with inclusion criteria of all women without diagnosis a previous breast cancer.

Types of Interventions

All clinical trials (RCT, pre- and post-test or quasi-experimental) involving educational program based on health models versus no intervention or versus another educational intervention.

Types of Comparator/control

Another intervention or No intervention.

Types of Outcome measures

Educational interventions based on different health behavior models’ adverse outcomes related to false positive findings of symptoms assessed by any validated scale.

Risk of Bias

The EPHPP is a tool used to evaluate of intervention design studies. This tool evaluates six domains: study design, blinding, selection bias, data collection method, confounders and dropouts. In this tool each domain is rated as weak (1), moderate (2) and strong (3) and total score provided by average of domain scores.. Based on total score, quality of studies is rated as weak (1.00–1.50), moderate (1.51–2.50) or strong (2.51–3.00) and the maximum total score is three (Thomas et al., 2004; Deeks et al., 2003; Armijo-Olivo et al., 2012). Two researchers was performed Search in databases; the abstracts were first assessed and then some articles underwent final assessment according to EPHPP and inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria. According to these criteria, articles achieving a score of 1.51 or more were included in the study.

Data analysis

The qualitative analysis was used in this review due to the heterogeneity of the data.

Results

Thirty six articles with 17,770 female participants in different contraries and Continents of world included in this twenty three article utilized a Health belief model (HBM) and 1 articles used both HBM and HPM, 5 articles used HBM and The Trans theoretical Model (TTM), 2 used HBM and (Theory planed behavior) TPB, 3 used TTM, 1 used Social cognitive theory (SCT) and finally 1 used Systematic Comprehensive Health Education and Promotion Model (SHEP).

The results of our study showed that several health behavior models were influencing on BSE, CBE and mammography screening behavior of women.

Health belief model

The results of the present review showed HBM-based educational intervention increases the women’s health motivation about BCS. Individuals’ behaviors and decisions related to general health conditions such as breast cancer can be evaluated using HBM (Aşcı and Şahin, 2011), According to this model, a woman decide to perform the screening while she perceives susceptibility to BC and severity of BC and perceives benefits and barriers of breast cancer screening behavior (Dündar et al., 2006).

Characteristics of Health belief model based studies showed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Health Belief Model Based Studies

| First Author/Year/location | Study Method/sample | Intervention | Outcome | quality rating EPHPP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kocaöz et al, (2017) /Turkey | “semi-experimental / N=342” | Theoretical and practical education | “In participants the susceptibility, benefits of BSE self-efficiency, and benefits of mammography perceptions increased while the seriousness, barriers of BSE, and mammography decreased.” | Moderate |

| Parsa et al, (2016)/ Iran | “quasi-experimental / 250 women (n=75 each group)” | “The intervention group received 90 minutes in four sessions GATHER consultancy technique and educational booklet /the control group received o any intervention” | In both groups 3 month After intervention, there was significant difference between the mean scores of perceived benefits and barriers, health motivation, self-sufficient, and doing the screening. in the intervention group there was no significant difference between the mean score of perceived susceptibility and severity | Moderate |

| Akhtari-Zavare et al, (2016)/ Malaysia | RCT/N=370(intervention=186, control=184) | The intervention group received, 16, 2-h workshops | The result showed that 6, 12 months after intervention the mean total HBM score in intervention group was significantly higher than CON. | Strong |

| Heydari et al, (2016)/ Iran | RCT/N=120(n=60group education/n=60multimedia education) | In group education two sessions lasting 45-60 min. In multimedia education planned based on HBM through CD, and educational SMS to their telephone | Result showed that in group education health motivation and perceived benefit were higher than the multimedia group. (93.33%) of group education and (83.33%) of multimedia group had intention of mammography. | Moderate |

| Kolutek et al, (2016)/ Turkey | quasi-experimental/N=153 | “Training practices were conducted using lecturing, demonstration, and question and answer techniques. The Telephone Reminder Intervention” | After the training practices mean scores of the seriousness, benefits of BES and self-efficacy, susceptibility, barriers to BES, and mammography and benefits of mammography under the HBM Scale for BC Screening significantly increased. | Moderate |

| Rezaeian et al, (2014)/ Iran | “Population-based controlled trial / N=290 Control=145 Intervention=145” | The intervention group received educational program (PowerPoint presentation, educational film, group discussion, brain storming, question and answer and pamphlet)/the control group received no intervention | After intervention in intervention group the mean scores of perceived susceptibility, severity, benefits, barriers and self-efficacy of mammography and health motivation significantly higher than the CON group. | Strong |

| Eskandari-torbaghan et al, (2014)/ Iran | “ Interventional design N=130 (65 intervention,65 control)” | Intervention group received Lectures, questions and answers, PowerPoint presentation, video and educational booklet/ Control group received no any intervention | After intervention awareness, perceived sociability and benefits, barriers and behavior in the intervention group was significantly higher than CON. | “Moderate” |

| Farma et al, (2014)/ Iran | “semi-experimental/ N=24” | The educational intervention(lecture, view video, group discussion) | In the intervention group score of all subscale of HBM significantly increased. | Moderate |

| Wang et al, (20120/Washington | “RCT/ N= 592” | “1)Culturally tailored video 2)Generic video 3) Control group received a Chinese double-sided breast cancer fact sheet” | Both videos reduced perceived barriers, improved screening knowledge, and increased screening intentions. | Moderate |

| Peterson et al, (2012) / Oregon | “RCT/ N=211 women with mobility impairments” | A 90-minute, small- group, participatory workshop with 6 months of structured telephone support | There were No significant group effect was observed for mammography | Moderate |

| Moodi et al, (2011) / Iran | “semi-experimental/ N=243” | One educational session (120 minutes) | After intervention the mean scores of knowledge, perceived susceptibility, severity, benefit and barrier significantly increased. | Moderate |

| “Sadler et al, (2011)/ America” | “RCT/N=428 219 intervention 209 control group” | “Intervention group salon-based BC education program control group received information about diabetes” | After the first 6 months of the program’s operation, women in the BC intervention group significantly greater frequency engaged in mammography screening relative to CON group. Consistent with the HBM, women in the BC intervention showed a shift in behaviors and increased BC screening. | Moderate |

| Ceber et al, (2010)/ Turkey | “Pretest-posttest /N=291(intervention=134, Control=157)” | the experimental group received the educational program (small group educational presentations, group videotapes on how to perform BSE, miniature lump model demonstration and practice in BSE and CBE) / the control group received no any intervention | The mean score of BC knowledge of women in the experimental group were higher than the control group. The experimental group significantly more likely motivated and to feel confident, also their total score on the health belief scale was much better than that of the CON. in the experimental group The application percentage of CBE and mammography was higher | Moderate |

| Aghamolaei et al, (2010)/ Iran | RCT/ N=240 (129 in each group) | Educational sessions by lecture | In the intervention group all HBM subscale significantly higher than CON. | Moderate |

| Aydin Avci et al, (2009)/ Turkey | “Pretest-posttest /N=51 in model group and 42 the video group” | The video group received a videotape explaining BSE, CBE and mammography and was 20 min in duration/the scale model group, was shown and oral information about BSE, mammography and CBE. | After the education in the video group, were showing increasing changes of susceptibility perceived self-efficacy and knowledge of BSE, and Perceived benefits of mammography. In the model group, susceptibility and perceived benefits of mammography and perceived self-efficacy of BSE, increased. | Moderate |

| DeFrank et al, (2009)/ Carolina | “RCT 1) N=847 Enhanced usual care reminder.2)N=1355Automated telephone reminder. N=1345Enhanced letter reminder" | The EUCRs, delivered as mailed letters, The mailed ELR was a full-color, four-page booklet with a quilt graphic on the cover./The ATRs were delivered as automated telephone calls by TeleVox Software | Women assigned to ATRs were significantly more likely to have had mammograms than women assigned to EUCRs. | Moderate |

| Gursoy et al, (2009)/ Turkey | “quasi-experimental design/ N=200 students, 168 mothers” | University students were trained by the School of Health students about BSE through group training methods. Then, these trained university students were asked to train their mothers about BSE | The results show that after training the women’s knowledge level increased 2-fold, also the perceived benefits and confidence significantly increased. | Moderate |

| Doris et al, (2002)/ Florida | non-equivalent experimental Experimental=116,Comparison=27 | loss-framed telephonic message | Mammogram performance in the loss-framed message group women n were 6 times more. | Moderate |

| Secginli et al, (2011)/ Turkey | “RCT/ N=190(intervention=97, control =93)” | The intervention group received Education with Booklet, Film, Calendar, Card/ The control group received No intervention | In the intervention group, significantly increasing were seen from pre- to posttest in perceived susceptibility, benefits of mammography and BSE, and confidence but perceived barriers to mammography were decreased. In the intervention group were seen No significant changes for perceived barriers to BSE. | Moderate |

| Jane Lu et al, (2001)/ Taiwanese | “quasi-experimental design/N=198 women” | “The monthly telephone reminders received BSE pamphlets” | The results of the study showed that the program significantly increased BSE accuracy and frequency, perceived benefit and competence of BSE, and decreased perceived susceptibility and barriers. | Moderate |

| Gozum et al, (2010)/ Turkey | “Pretest-posttest / N=5100 with 40 peer training women” | Oral presentation, group discussion, training CD about BSE and mammography | After peer training, scores significantly increases in the dimensions of motivation about healthcare, seriousness, mammography benefits, and benefits and self-efficacy of BSE and decrees in barriers to BSE and mammography training. | Moderate |

| Özgül et al, (2009)/ Turkey | “Pretest-posttest/ N=193 female 59 were peer trainer” | “The one-to-one education by peer trainers posters” | After peer education mean knowledge scores significantly increased. The rate of regular BSE significantly increased, perceived benefits and confidence of BSE increased and perceived barriers significantly decreased. | Moderate |

| Hall et al, (2005)/ United States | “Pretest, post-test N=53(intervention=30,Control=23)" | 60–70 minutes educational program | In the intervention group the mean score of Susceptibility, Benefits and barriers of mammography and BSE and Confidence were significantly higher than CON. | Moderate |

Kocaöz et al., (2017) indicated that education program based on HBM increased the attitudes and BCS behaviors of women. Parsa et al., (2016) study, showed that HBM based intervention with GATHER (Greet, ASK, TELL, Help, Explain, Return) consultancy technique could help to improve the knowledge and beliefs about BCS and BSE performance. Heydari and Noroozi, (2015) reported that group education and multimedia education based on HBM lead to raise BC knowledge and participation in mammography. Kolutek et al., (2016) reported that HBM based intervention significantly increased rate of performing BSE. Akhtari-Zavare et al., (2016) in their study indicated that in the intervention group only three subscales score of HBM (benefits, barrier, and confidence of BSE) were significantly improved. Peterson et al., (2012) reported that in women with mobility impairments the HBM based education was not effective on mammography screening behavior. In Eskandari-torbaghan et al., (2014) study, after HBM based intervention in the intervention group the awareness, perceived susceptibility and benefits, barriers and behavior were significantly higher than control. Farma et al., (2014) reported that HBM based education have significant impact on improving BCS behavior. Rezaeian et al., (2014) reported that small group education based on HBM increased the knowledge and health beliefs about BC and mammography. Hall et al., (2005) reported that HBM based education were effective on knowledge and beliefs about breast cancer. Moodi et al., (2011) reported that HBM based education improved attitude and knowledge of female university students regarding BSE. Ceber et al., (2010) reported that the mean score of BC knowledge of women in the experimental group were higher than the control. The experimental group significantly more likely motivated and to feel confident, but there were no significant differences in perceived susceptibility, seriousness of BC, benefits and barriers to BSE. Avci and Gozum, (2009) study showed that both video and model methods intervention based on HBM were effective in changing BCS health beliefs of women. Aghamolaei et al., (2010) reported that health education program based on HBM promote BSE in women. Wang et al., (2012) reported that in the cultural and generic video interventions based on HBM modified mammography screening attitude of Chinese immigrant women. Sadler et al., (2011) resulted that after the HBM based program, women in the intervention group significantly higher rate of mammography screening. DeFrank et al., (2009) showed that mailed and automated telephone reminders interventions based on HBM were effective in promoting repeat mammography. Doris et al., (2002) demonstrated that intervention based on HBM in the loss-framed message group lead to women in this group were 6 times more likely to obtain a mammogram performance. Özgül et al., (2009) reported that peer education based on HBM increased BC knowledge and improved the BSE performance. Gozum et al., (2010) mentioned that after peer training based on HBM had positive effect on promoting practice, beliefs and knowledge, of women. Secginli and Nahcivan, (2011) reported that for the intervention group, significant changes were seen in perceived susceptibility, benefits of BSE and mammography, and confidence (all increased), but perceived barriers to mammography decreased. Results of Cohen and Azaiza (2010) Study shows that culture-based intervention based on HBM effective in BCS behavior of women. Gursoy et al., (2009) indicated that the HBM based education from daughter to mother enhance women’s knowledge about BSE.Lu et al., (2001) stated that the program significantly increased BSE accuracy, BSE frequency, perceived benefit of BSE, perceived competence in BSE and decreased perceived susceptibility to breast cancer and perceived barriers to practice BSE.

The Trans theoretical Model (TTM)

According this model behavioral changes occur through a process of different stages (precontemplation, relapse, relapse risk, contemplation, action and maintenance stages). Farajzadegan et al., (2016) and Ghahremani et al., (2016) reported that educational interventions base on TTM improve BSE performance of women. Lin and Judith (2010) mentioned that tailored intervention group based on TTM had a better outcome and higher mean posttest scores relative to the Standard in group (Lin and Effken, 2010). Lin and Wang (2009) in their study reported that complete tailored intervention had significantly higher scores on intention to have a mammogram relative to the standard intervention group. Characteristics of TTM model based studies showed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Included Studies Based on TTM, SCT and SHEP Models

| First Author/Year/ location | “Study Method/sample” | Model | Intervention | Outcome | “quality rating EPHPP” |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghahremani et al, (2016) / Iran | “quasi-experimental N=168” | The Trans theoretical Model | 45-minute sessions educational program about BSE. | In the intervention group subscale of TTM (self-efficacy, stages of change, decisional balance) significantly higher than CON. | Moderate |

| Lin and Judith (2010)/ Taiwan | “pretest–posttest design/ N=128 (64 in each group)” | The Trans theoretical Model | The tailored intervention group received a feedback, personal testimonies, and role modeling/The standard intervention group received mammography brochures. | after intervention the tailored intervention group had significantly more positive perceptions of mammography and more intention to have mammography than the standard intervention group | Moderate |

| Lin & Wang (2009)/ | “pretest–posttest design/ N=185” | The Trans theoretical Model | “1.Complete tailored intervention(N= 61): education activity, utilizing a personal testimony activity, and an environmental reevaluation technique 2.Tailored message intervention(N = 6 3)received computer-generated messages 3.Standard intervention(N = 61): received educational brochures” | The result showing CTI earned a higher mean (60.56) post intervention score than that of both TMI (57.95) and SI (53.26). | Moderate |

| Mirzaii et al, (2016)/ Iran | “randomized quasi-experimental N=120” | SHEP model | SHEP-based educational intervention was implemented in the form of workshops and two four-hour sessions (total: 8 h) | After the intervention, in the experimental group women had significantly higher attitude scores relative to the CON. Also in the experimental group significant increase was seen in the BSE scores. | Moderate |

| Goel et al, (2016)/ United States | “Pretest-post test N=97” | social cognitive theory | intervention group viewed a brief video | “In the intervention group the proportion of mammogram referrals Were significantly higher than CON” | Moderate |

Table 3.

Characteristics of Included Studies Based on Mixed Models

| First Author/Year/ location | “Study Method/sample” | Model | Intervention | Outcome | “quality rating EPHPP” |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tuzcu et al, (2016)/ Turkey | “Quasi experimental N=200 women (100 in each group)” | HBM-HPM | “65minute training Consultation by telephone Reminder cards” | In women in the intervention group after intervention the rates of mammography; BSE and CBE were significantly higher than women in the CON. | Moderate |

| Lee-Lin et al, (2015)/ America | “RCT N= 300 Intervention=147 Control=153” | HBM/TTM | “Educational intervention class A scripted verbal presentation accompanied by PowerPoint slides Control group received No intervention” | The result showed, that intervention group compared the CON was 9 times more likely to complete mammograms. | Moderate |

| Cohen& Azaiza (2010)/ Israeli | “Pretest posttest,/ N=66” | HBM/TTM | the intervention group received tailored telephone / The control group received any intervention | After intervention 47.6% of women in intervention group and 12.5% of women in CON group scheduled or attended a CBE (p<0.05), 38% of the intervention group and 75% of the CON group had only irregularly attended or never CBE. | Moderate |

| “Champion et al, (2007)/ India” | “prospective randomized intervention/ N=1244” | HBM/TTM | (1) usual care, (2) tailored telephone counseling, (3) tailored print, or (4) tailored print and telephone counseling | For contemplators, the combination of telephone and print was clearly the most effective intervention for promoting mammography; it appears that adding the printed material to the phone messaging hah and additive effect. | Moderate |

| Champion et al, (2006)/ America | “prospective randomized intervention N=344” | HBM/TTM | 1) pamphlet only (2) culturally appropriate video(3) interactive computer-assisted instruction program | The result showed that adherence to mammography in the interactive computer-assisted instruction program group was greater than two other intervention groups. | Moderate |

| “Champion et al, (2003)/ America” | “RCT N=773” | HBM/TTM | 1)standard care(2)tailored telephone counseling, (3) tailored in-person counseling, (4) non tailored recommendation letter signed (by scanned signature) by their primary care physician(5) tailored telephone counseling plus non tailored physician recommendation letter(6) tailored in-person counseling plus non tailored physician recommendation letter, usual care | All intervention groups have higher odds of mammography relative to the usual care group. Women receiving a combination of physician recommendation and in-person counseling have a higher odds of mammography adherence relative to the physician recommendation group (OR = 1.84) and telephone counseling group (OR =1.78). | Moderate |

| Taymoori et al, (2015)/ Iran | “RCT N=184 TPB (N = 60) HBM (N = 63) control group (N = 61)” | HBM/TPB | “There were 8 sessions for the HBM and TPB interventions that focused on perceived threat (lecture, Reminder card, small groups discussion, consulting) the CON group received pamphlets” | In the intervention groups women perceived severity and susceptibility of BC and perceived benefits and self-efficacy of mammography use increased but perceived barriers about mammography use decreased. Women in intervention groups have greater perceived control and higher levels of positive subjective norms regarding mammography. | Moderate |

| “Farhadifar et al, (2016)/ Iran” | “ N=176 (TPB = 62; HBM = 58; CON = 56).” | HBM/TPB | “1) An 20-week timeline intervention Lecture intervention based on (HBM); 2) a tailored individual counseling and reminders/pamphlets targeting in TPB 3) a control group received no intervention.” | The screening in women in the HBM group have significantly increased compare to CON group due to greater susceptibility, perceived control, and self-efficacy, and women in the TPB- group have greater odds of performance mammograms compare to CON lead to increased self-efficacy and much reductions in barriers. | Moderate |

Social cognitive theory (SCT)

This theory demonstrate that a multifaceted causal operate together with goals, outcome and perceived environmental barriers and facilitators in the regulation of behavior (Bandura, 2004). Goel and O’Conor, (2016) showed that a brief, pre-visit video based on SCT significantly increased mammography referrals. Characteristics of SCT model based studies showed in Table 2.

Systematic Comprehensive Health Education and Promotion Model: (SHEP)

SHEP is an innovative developmental method in the health promotion system, this model based on the of “Knowledge Management” theory (Mirzaii et al., 2016). Mirzaii et al, (2016) mentioned that education based on SHEP had positive effect on attitudes and BCS behavior of women. Characteristics of SHEP model based studies showed in Table 2.

Mixed model

In this study eight articles used different mix models. Tuzcu et al, (2016) demonstrated the rates of mammography; BSE and CBE in the intervention group based on HBM-HPM were significantly higher than control group. In the intervention group, the self-efficacy perceptions benefit and health motivation, increased but perceptions of barriers and susceptibility decreased. Farhadifar et al., (2016) reported that HBM and TPB based interventions had positive effect on mammography screening behavior. Lee-Lin et al., (2015) mentioned that the culturally targeted educational based HBM-TTM program significantly increased mammogram screening in women. Taymoori et al., (2015) reported that educational intervention based on HBM and TPB improved mammography screening of women. The Results of Cohen and Azaiza (2010) Study shows HBM-TTM culture based intervention reduced the berries and improved BCS behavior. Champion et al., (2006) demonstrated that tailored HBM-TTM based education program is more effective than targeted messages (print or video format) in mammography screening behavior of low income African American women. Champion et al., (2007) reported that all interventions based on HBM-TTM had positive effect on mammography screening behavior of women. In Champion et al., (2003) study tailored interventions based on HBM and TTM lead to increase mammography screening in older women. Characteristics of Mixed model based studies showed in Table 2.

Discussion

This review provides new insight into the effectiveness of model based interventions on breast cancer screening behavior of women; our result showed that health behavior models could help to enhance BCS behavior of women.

About three fourth of the studies were included in our study were about the HBM based interventions with different educational intervention (including: GATHER consultancy technique, multimedia education, brain storming, pamphlet, video and educational booklet, mailed letters, telephone reminder, reminder cards etc.). Almost all of HBM based studies showed positive effect in different subscale of HBM on BSE, CBE or mammography screening behavior but only in one study which included women with mobility impairments there were no significant group effect for mammography. Sohl and Moyer, (2007) in a meta-Analytic review reported that Tailored Interventions based on HBM had strong effect on BCS behavior. In this review only 45% of studies HBM mixed to other models, these interventions improve the BC awareness of women and increased awareness and performance of the BSE, CBE and mammography screening in the intervention group. The result of a systematic review which conducted by Ersin and Bahar, (2011) about Effect of Health Belief Model and Health Promotion Model on Breast Cancer Early Diagnosis Behavior showed that the intervention based on these models in improving and maintaining breast cancer screening behavior. A study in Asian American women about BCS rate showed that culturally cancer education programs could increase access to breast cancer screening (Sadler et al., 2009). Also cancer education interventions have a positive effect on breast cancer knowledge of women (Zeinomar and Moslehi, 2013).

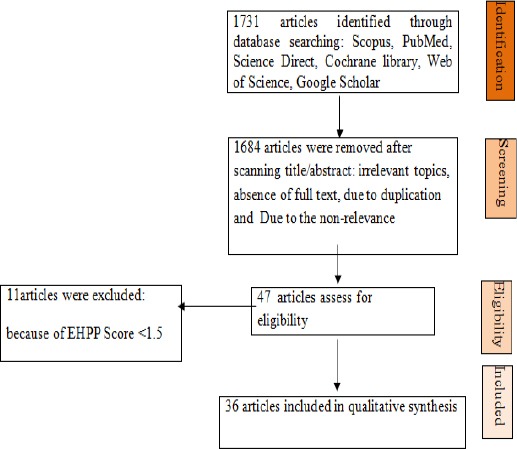

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Articles Selection

The Trans theoretical Model, Systematic Comprehensive Health Education and Promotion Model, Health Promotion Model, theory of planned behavior are the other models used in different educational program such as workshops, tailored mail and telephone intervention, apartment billboards, peer education, which review in our study. Health models are useful on health perceptions of women (Ergin et al., 2012). The Health Promotion Model categorizes the factors that influencing human behaviors, this model survey the behavioral and situational factors and interpersonal relation (Galloway, 2003). The theory of Planned Behavior demonstrate attitude toward the behavior, and perceived behavioral control and subjective norm (Asare, 2015). The purpose of the systematic comprehensive health education and promotion model was increasing health literacy and mentoring peer health educators (Mirzaii et al., 2016). Trans theoretical Model helps planners programs based on an individual’ motivation, and ability (Glanz et al., 2008).

Our review showed that the trans-theoretical model combined with the other models were successful than other models because this model is based on the stages of behavioral change but other models show the creating behavior mechanism, so for this reason, combined this model with the other models will lead to greater success program. Structure of the TTM is more complex than other models, and this model is effective to promote both individual and population level health behavior change programs (Taylor, 2007).Cancer education and Health Behavioral Counseling based on TTM can promote healthy lifestyles (McLaughlin et al., 2010).

In a meta-analysis study reported that Health models improve breast cancer screening in women (Ergin et al., 2012). In review article with title “Applying the Trans-theoretical Model to Cancer Screening Behavior” concluded that Stage of change and decisional balance appear to use to mammography performance (Spencer et al., 2005). Lawal et al., (2016) in their narrative review article reported that among four health behavioral theories and models (the HBM, TBP, TTM, and the theory of care seeking behavior), the theory of care seeking behavior uses broader constructs and is affective in participation of women in mammography screening. Ahmadian and Samah, (2013) in their article reviews several cognitive theories and models associated with BC screening and they reported that in Asian women a few empirical study were about the application of health theories in promoting to the BC prevention programs and a few studies addressed the individual cognitive factors that are likely to motivate women to protect against BC in Asia.

Cancer education interventions lead to increasing constructive health behaviors (Booker et al., 2014). Breast cancer screening education is a low cost program with high benefit for women’s health in worldwide (Kennedy et al., 2016). Education about breast cancer can increase BCS practice and knowledge of women (Gözüm et al., 2010).

The strength of the study is that our study is based on experimental studies which performed in different area of world. Further recommendations for research would include studies specifically

In conclusion, the educational model-based interventions promote self-care and create a foundation for improving breast cancer screening behavior of women and increase policy makers’ awareness and efforts toward enhancing breast cancer screening promotion. Model-based interventions are more successful than interventions that are not based model because these programs are based on understanding the mechanism of health behavior change and researchers with accurate understanding of the mechanism or process of behavior change programs are more likely to succeed plan.

Limitations

In this review due to the heterogeneity of the data, we cannot do meta-analysis. The other limitation of our study is that we only use common educational behavior change models so another studies needs to review the impact of other models on breast cancer screening behavior of women.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Acknowledgments

The all author thanks from midwifery and reproductive health Research Center of Shahid Beheshti Medical University.

References

- 1.Abolfotouh MA, Ala'A AB, Mahfouz AA, et al. Using the health belief model to predict breast self examination among Saudi women. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1163. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2510-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abood DA, Coster DC, Mullis AK, Black DR. Evaluation of a “loss-framed” minimal intervention to increase mammography utilization among medically un-and under-insured women. Cancer Detect Prev. 2002;26:394–400. doi: 10.1016/s0361-090x(02)00120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aghamolaei T, Hasani L, Tavafian SS, Zare S. Improving breast self-examination: An educational intervention based on health belief model. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2011;4:82–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmadian M, Samah AA. Application of health behavior theories to breast cancer screening among Asian women. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:4005–13. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.7.4005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akhtari-Zavare M, Juni MH, et al. Result of randomized control trial to increase breast health awareness among young females in Malaysia. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:738. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3414-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allahverdipour H, Asghari-Jafarabadi M, Emami A. Breast cancer risk perception, benefits of and barriers to mammography adherence among a group of Iranian women. Women Health. 2011;51:204–19. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2011.564273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ardahan M, Dinc H, Yaman A, Aykir E, Aslan B. Health beliefs of nursing faculty students about breast cancer and self breast examination. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:7731–6. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.17.7731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, Biondo PD, Cummings GG. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the cochrane collaboration risk of bias tool and the effective public health practice project quality assessment tool: methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18:12–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arrospide A, Rue M, Vanravesteyn NT, et al. Evaluation of health benefits and harms of the breast cancer screening programme in the Basque Country using discrete event simulation. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:671. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1700-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asare M. Using the theory of planned behavior to determine the condom use behavior among college students. Am J Health Stud. 2015;30:43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asci ÖS, Şahin NH. Effect of the breast health program based on health belief model on breast health perception and screening behaviors. Breast J. 2011;17:680–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2011.01143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashing-Giwa K. Health behavior change models and their socio-cultural relevance for breast cancer screening in African American women. Womens Health. 1999;28:53–71. doi: 10.1300/J013v28n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avci IA, Gozum S. Comparison of two different educational methods on teachers'knowledge, beliefs and behaviors regarding breast cancer screening. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2009;13:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:143–64. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Booker A, Malcarne VL, Sadler GR. Evaluating outcomes of community-based cancer education interventions: A 10-year review of studies. J Cancer Educ. 2014;29:233–40. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0578-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calonge N, Peitti DB, Dewitt TG, et al. Screening for breast cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:716–26. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ceber E, Turk M, Ciceklioglu M. The effects of an educational program on knowledge of breast cancer, early detection practices and health beliefs of nurses and midwives. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:2363–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Champion V, Maraj M, Hui S, et al. Comparison of tailored interventions to increase mammography screening in nonadherent older women. Prev Med. 2003;36:150–8. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(02)00038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Champion V, Skinner CS, Hui S, et al. The effect of telephone versus print tailoring for mammography adherence. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65:416–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Champion VL, Springston JK, Zollinger TW, et al. Comparison of three interventions to increase mammography screening in low income African American women. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006;30:535–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chanizi M, Kaveh MH. Educational interventions and cancer prevention: A systematic review. J Cell Immunotherapy. 2017;3:17–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen M, Azaiza F. Increasing breast examinations among Arab women using a tailored culture-based intervention. Int J Behav Med. 2010;36:92–99. doi: 10.1080/08964280903521313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deeks J, Dinnes J, D'amico R, et al. Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technol Assess (Winchester, England) 2003;7:1–173. doi: 10.3310/hta7270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Defrank JT, Rimer BK, Gierisch JM, et al. Impact of mailed and automated telephone reminders on receipt of repeat mammograms: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:459–467. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dundar PE, Özmen D, Özturk B, et al. The knowledge and attitudes of breast self-examination and mammography in a group of women in a rural area in western Turkey. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ergin AB, Sahin NH, Sahin FM, et al. Meta analysis of studies about breast self examination between 2000-2009 in Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:3389–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ersin F, Bahar Z. Effect of health belief model and health promotion model on breast cancer early diagnosis behavior: a systematic review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:2555–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ersin F, Gozukara F, Polat P, Ercetin G, Bozkurt ME. Determining the health beliefs and breast cancer fear levels ofwomen regarding mammography. Turk J Med Sci. 2015;45:775–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eskandari-Torbaghan A, Kalan-Farmanfarma K, Ansari-Moghaddam A, Zarei Z. Improving breast cancer preventive behavior among female medical staff: the use of educational intervention based on health belief model. Malays J Med Sci. 2014;21:44–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farajzadegan Z, Fathollahi-Dehkordi F, Hematti S, et al. The transtheoretical model, health belief model, and breast cancer screening among Iranian women with a family history of breast cancer. J Res Med Sci. 2016;21:122. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.193513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farhadifar F, Molina Y, Taymoori P, Akhavan S. Mediators of repeat mammography in two tailored interventions for Iranian women. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:149. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2808-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farma KKF, Jalili Z, Zareban I, Pour MS. Effect of education on preventive behaviors of breast cancer in female teachers of guidance schools of Zahedan city based on health belief model. J Educ Health Promot. 2014;3:77. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.139240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galloway RD. Health promotion: causes, beliefs and measurements. Clin Med Res. 2003;1:249–58. doi: 10.3121/cmr.1.3.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghahremani L, Kaveh M, Ghaem H. Self-care education programs based on a trans-theoretical model in women referring to health centers: Breast self-examination behavior in Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:5133–8. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2016.17.12.5133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glanz K, Bishop DB. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:399–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice, John Wiley and Sons. 4th edition. 2008:1–516. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goel MS, O'conor R. Increasing screening mammography among predominantly Spanish speakers at a federally qualified health center using a brief previsit video. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99:408–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gozum S, Karayurt Ö, Kav S, Platin N. Effectiveness of peer education for breast cancer screening and health beliefs in eastern Turkey. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33:213–20. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181cb40a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gursoy AA, Ylmaz F, Nural N, et al. A different approach to breast self-examination education: Daughters educating mothers creates positive results in Turkey. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32:127–34. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181982d7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hajian-Tilaki K, Auladi S. Health belief model and practice of breast self-examination and breast cancer screening in Iranian women. Breast Cancer. 2014;21:429–34. doi: 10.1007/s12282-012-0409-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hall CP, Wimberley PD, Hall JD, et al. Teaching breast cancer screening to African American women in the Arkansas Mississippi river delta. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32:857–63. doi: 10.1188/05.onf.857-863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hay JL, Mccaul KD, Magnan RE. Does worry about breast cancer predict screening behaviors?A meta-analysis of the prospective evidence. Prev Med. 2006;42:401–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heydari E, Noroozi A. Comparison of two different educational methods for teachers'mammography based on the Health Belief Model. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:6981–6. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.16.6981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.İZ FB, Tumer A. Assessment of breast cancer risk and belief in breast cancer screening among the primary healthcare nurses. J Cancer Educ. 2016;31:575–81. doi: 10.1007/s13187-015-0977-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karayurt Ö, Dicle A, Malak AT. Effects of peer and group education on knowledge, beliefs and breast self-examination practice among university students in Turkey. Turk J Med Sci. 2009;39:59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kennedy LS, Bejarano SA, Onega TL, Stenquist DS, Chamberlin MD. Opportunistic breast cancer education and screening in rural Honduras. J Glob Oncol. 2016;2:174–80. doi: 10.1200/JGO.2015.001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kocaoz S, Ozcelik H, Talas MS, et al. The effect of education on the early diagnosis of breast and cervix cancer on the women's attitudes and behaviors regarding participating in screening programs. J Cancer Educ. 2017:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s13187-017-1193-8. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kolutek R, Avci IA, Sevig U. Effect of planned follow-up on married women's health beliefs and behaviors concerning breast and cervical cancer screenings. J Cancer Educ. 2016;33:375–82. doi: 10.1007/s13187-016-1114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lawal O, Murphy F, Hogg P, Nightingale J. Health behavioural theories and their application to women's participation in mammography screening: a narrative review. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2016;2016:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jmir.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee-Lin F, Nguyen T, Pedhiwala N, Dieckmann N, Menon U. A breast health educational program for Chinese-American women:3-to 12-month postintervention effect. Am J Health Promot. 2015;29:173–81. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.130228-QUAN-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levano W, Miller JW, Leonard B. Public education and targeted outreach to underserved women through the national breast and cervical cancer early detection program. Cancer. 2014;120:2591–6. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin ZC, Wang SF. A tailored web-based intervention to promote women's perceptions of and intentions for mammography. J Nursing Res. 2009;17:249–60. doi: 10.1097/JNR.0b013e3181c15a38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin ZC, Effken JA. Effects of a tailored web-based educational intervention on women's perceptions of and intentions to obtain mammography. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:1261–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.LU ZYJ. Effectiveness of breast self-examination nursing interventions for Taiwanese community target groups. J Adv Nurs. 2001;34:163–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mclaughlin RJ, Fasser CE, Spence LR, Holcomb JD. Development and implementation of a health behavioral counseling curriculum for physician assistant cancer education. J Cancer Educ. 2010;25:9–15. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0038-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mirzaii K, Nessari Ashkezari S, Khadivzadeh T, Shakeri MT. Evaluation of the effects of breast cancer screening training based on the systematic comprehensive health education and promotion model on the attitudes and breast self-examination skills of women. Evid Based Care. 2016;6:7–18. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moodi M, Mood MB, Sharifirad GR, Shahnazi H, Sharifzadeh G. Evaluation of breast self-examination program using Health Belief Model in female students. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16:316. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nergiz-Eroglu U, Kilic D. Knowledge, attitude and beliefs women attending mammography units have regarding breast cancer and early diagnosis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;12:1855–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Noar SM, Zimmerman RS. Health behavior theory and cumulative knowledge regarding health behaviors: are we moving in the right direction? Health Educ Res. 2005;20:275–90. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Noroozi A, Tahmasebi R. Factors influencing breast cancer screening behavior among Iranian women. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:1239–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.O'mahony M, Comber H, Fitzgerald T, et al. Interventions for raising breast cancer awareness in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017:1–35. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011396.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Parsa P, Mirmohammadi A, Khodakarami B, Roshanaiee G, Soltani F. Effects of breast self-examination consultation based on the health belief model on knowledge and performance of Iranian women aged over 40 years. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:3849–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peterson JJ, Suzuki R, Walsh ES, Buckley DI, Krahn GL. Improving cancer screening among women with mobility impairments: Randomized controlled trial of a participatory workshop intervention. Am J Health Promot. 2012;26:212–6. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.100701-ARB-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Petro-Nustas W, Tsangari H, Phellas C, Constantinou C. Health beliefs and practice of breast self-examination among young Cypriot women. J Transcult Nurs. 2013;24:180–8. doi: 10.1177/1043659612472201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reid AE, Aiken LS. Integration of five health behaviour models: common strengths and unique contributions to understanding condom use. Psychol Health. 2011;26:1499–1520. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.572259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rezaeian M, Sharifirad G, Mostafavi F, Moodi M, Abbasi MH. The effects of breast cancer educational intervention on knowledge and health beliefs of women 40 years and older, Isfahan, Iran. J Educ Health Promot. 2014;3:59–64. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.131929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sadler GR, Hung J, Beerman PR, et al. Then and now: comparison of baseline breast cancer screening rates at 2 time intervals. J Cancer Educ. 2009;24:4–9. doi: 10.1080/08858190802683560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sadler GR, KO CM, Wu P, et al. A cluster randomized controlled trial to increase breast cancer screening among African American women: the black cosmetologists promoting health program. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103:735. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30413-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Secginli S, Nahcivan NO. The effectiveness of a nurse-delivered breast health promotion program on breast cancer screening behaviours in non-adherent Turkish women: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48:24–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shiryazdi SM, Kholasehzadeh G, Nematzadeh H, Kargar S. Health beliefs and breast cancer screening behaviors among Iranian female health workers. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:9817–22. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.22.9817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sohl SJ, Moyer A. Tailored interventions to promote mammography screening: a meta-analytic review. Prev Med. 2007;45:252–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Spencer L, Pagell F, Adam ST. Applying the transtheoretical model to cancer screening behavior. Am J Health Behav. 2005;29:36–56. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.29.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Talley CH, Yang L, Williams KP. Breast cancer screening paved with good intentions: Application of the information–motivation–behavioral skills model to racial/ethnic minority women. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016;20:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tavafian SS, Hasani L, Aghamolaei T, Zare S, Gregory D. Prediction of breast self-examination in a sample of Iranian women: an application of the Health Belief Model. BMC Womens health. 2009;9:37. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-9-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Taylord D. A review of the use of the health belief model (HBM), the theory of reasoned action (TRA), the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) and the trans-theoretical model (TTM) to study and predict health related behaviour change. School of Pharmacy, University of London. 2007:1–212. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Taymoori P, Molina Y, Roshani D. Effects of a randomized controlled trial to increase repeat mammography screening in Iranian women. Cancer Nurs. 2015;38:288. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thomas B, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004;1:176–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tsunematsu M, Kawaski H, Masuoka Y, Kakehashi M. Factors affecting breast cancer screening behavior in Japan-assessment using the health belief model and conjoint analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:6041–8. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.10.6041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tuzcu A, Bahar Z, Gozum S. Effects of interventions based on health behavior models on breast cancer screening behaviors of migrant women in Turkey. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39:40–50. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Veena K, Kollopaka R, Rekha R. The knowledge and attitude of breast self examination and mammography among rural women. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2015;4:1511–6. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang JHY, Schwrtz MD, Luta G, Maxwell AE, Mandelblatt JS. Intervention tailoring for Chinese American women: comparing the effects of two videos on knowledge, attitudes and intentions to obtain a mammogram. Health Educ Res. 2012;27:523–36. doi: 10.1093/her/cys007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zeinomar N, Moslehi R. The effectiveness of a community-based breast cancer education intervention in the New York State Capital Region. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28:466–73. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0488-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]