Abstract

To evaluate whether Palmitoyl-pentapeptide (Pal-KTTKS), a lipidated subfragment of type 1 pro-collagen (residues 212–216), plays a role in fibroblast contractility, the effect of Pal-KTTKS on the expression of pro-fibrotic mediators in hypertropic scarring were investigated in relation with trans-differentiation of fibroblast to myofibroblast, an icon of scar formation. α-SMA was visualized by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy with a Cy-3-conjugated monoclonal antibody. The extent of α-SMA-positive fibroblasts was determined in collagen lattices and in cell culture study. Pal-KTTKS (0–0.5 µM) induced CTGF and α-SMA protein levels were determined by western blot analysis and fibroblast contractility was assessed in three-dimensional collagen lattice contraction assay. In confocal analysis, fibroblasts were observed as elongated and spindle shapes while myofibroblast observed as squamous, enlarged cells with pronounced stress fibers. Without Pal-KTTKS treatment, three quarters of the fibroblasts differentiates into the myofibroblast; α-SMA-positive stress fibers per field decreased twofold with 0.1 µM Pal-KTTKS treatment (75 ± 7.1 vs 38.6 ± 16.1%, n = 3, p < 0.05). The inhibitory effect was not significant in 0.5 µM Pal-KTTKS treatment. Stress fiber level and collagen contractility correlates with α-SMA expression level. In conclusion, Pal-KTTKS (0.1 µM) reduces α-SMA expression and trans-differentiation of fibroblasts to myofibroblast. The degree of reduction is dose-dependent. An abundance of myofibroblast and fibrotic scarring is correlated with excessive levels of α-SMA and collagen contractility. Delicate balance between the wound healing properties and pro-fibrotic abilities of pentapeptide KTTKS should be considered for selecting therapeutic dose for scar prevention.

Keywords: KTTKS, Myofibroblast, α-SMA, CTGF, Scar

Introduction

A sub-fragment of type-1 collagen with a minimum necessary sequence of KTTKS (Lys-Thr-Thr-Lys-Ser, MW = 563.64, Log P = −3.27) has been reported to increase collagen production in fibroblasts [1–3]. In present, there are still contradiction regarding the effect of KTTKS on the tissue regeneration and dermal wound healing process [4, 5]. Whether continuous exposure to KTTKS would improve the cosmetic appearance and wound healing process still needs to be clarified [6–8]. To increase the skin penetration, attachment of palmitic acid to the N-terminal group of lysine through the formation of amide was introduced as a palmitoyl-KTTKS (Pal-KTTKS, MW = 802.05, Log P = 3.32). Regarding the biological mechanism, there’s limited information in the literature. Most of the reported clinical benefits were obtained by using a formulation containing palmitoyl-KTTKS and other active ingredients combined. Previous in vivo published studies did not differentiate the role of Pal-KTTKs with other ingredients presence in the formulation. Thus the reported beneficial clinical effects could not be readily verified [9].

Regulation of collagen synthesis and deposition is a direct approach to the control of scar tissue formation [10]. Connective Tissue Growth Factor (CTGF) in early wound healing stage has beneficial effect in collagen production and proper organizing and epithelialization [11–13]. However, sustained over-expression of CTGF induced fibrosis CTGF elevation has been implicated in number of fibrotic lesions [14, 15]. Recent studies have demonstrated that in addition to its direct effect on extracellular matrix turnover, it may stimulate fibroblast–-myofibroblast differentiation, as it is capable of up-regulating α-SMA in fibroblast. During normal wound repair, myofibroblasts are transiently present at the wound site causing wound contraction and restoration of tissue integrity [16, 17]. Once the wound had regained normal structure and function, myofibroblasts disappear by apoptosis. However, in pathological states, myofibroblasts persists and produce excess of extracellular matrix deposition and tissue deformation leading to scarring [18, 19]. Even though myofibroblasts are crucial for proper wound repair, their timely disappearance is crucial for preventing undesirable scarring process [20, 21].

In this study, we investigated how palmitoyl-pentapeptide (Pal-KTTKS) could modify the outcome of wound healing, scar disposition. The effect of Pal-KTTKS on α-SMA and CTGF, a pro-fibrotic mediators involved in hyper-tropic scarring were investigated in relation with modulation of trans-differentiation of fibroblast to myo-fibroblast, the most reliable marker of hypertropic scar formation.

Materials and methods

Materials

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma chemicals (MO, USA). Human dermal fibroblast was provided from dept. dermatology, Seoul National University. Pal-KTTKS pentapeptide was purchased from Peptron Co. (Daejeon, Korea). DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium) culture medium and FBS (fetal bovine serum) were purchased from Cellgro (Washington DC, USA), PS (Penicillin Streptomycin) was purchased from Gibco (NY, USA) and Cultrex®Rat Collagen I was purchased from Trevigen (MD, USA).

Cell lines

Primary human foreskin fibroblasts were cultured in a 6 well plate (5 × 105 cells/well) in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum and 100 units/mL penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere with 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

In vitro wound healing study

In vitro fibroblast wound model was prepared as reported previously [22]. In brief, cells were plated in six-well plates at 1 × 105cells/well confluence and grown for 24 h. After scratching with a sterile 10 µL micro tip, cells were treated with Pal-KTTKS for predetermined time points (3–6 h) in incubator. After treating with Pal-KTTKS, cell morphology, cell migration and proliferation were observed and images were captured and analyzed with Olympus microscopy system composed of an inverted microscope (OLYMPUS CK40-F200) and Camera (Olympus DP-21, Japan). Wound closure areas were quantified by using Analysis TS Auto Olympus soft imaging solution GmbH program at predetermined post injury time. Digitized images were captured with an inverted microscope (Olympus CK40-F200, Japan) and digital camera (Olympus DP21, Japan) (objective lens × 10, eyepiece × 10) expose time 2000 ms, sensitivity ISO100 (×100).

CTGF immunoblot analysis

After 6 h Pal-KTTKS treatment, cells were rinsed with cold PBS and lysed in SDS-lysis buffer. Equal amounts of protein extracts in SDS-lysis buffer were subjected to 12% SDS-PAGE analysis and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Anti-CTGF antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz (CA, USA). β-actin antibody was from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA). Enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia, Buckinghamshire, U.K.) system was used for detection. Relative intensity of the bands were determined by an Image Analyzer Gel Logic 200 Imaging System (NY, USA).

α-SMA western blot analysis

After scratching with a sterile 10 µL micro tip, cells were cultured with and without Pal-KTTKS in the absence of fetal bovine serum (FBS). The cells are washed 2–3 times with cold PBS. Each well was added 70–80 µL lysis buffer (1 M tris (pH 6.8) 500 µL, 10% SDS 2 mL, 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0) 20 µL, 1 M DDT 1 mL, protease inhibitor 1tab, D.W 5.48 mL; total 10 mL) to prepare a supernatant. The concentration of the supernatant was measured by Bradford method using Protein Assay Reagent (Bio-Rad, USA). The protein were separated by SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide), transferred onto PVDF membrane and probed with specific polyclonal antibodies and secondary antibodies. Protein-antibody complexes were visualized by the enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Pharmacia, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Collagen lattice contraction

After the cells were cultured with and without Pal-KTTKS for 6 h, control and Pal-KTTKS treated cells were trypsinized. Collagen lattice contraction was prepared with 1.4 mL bovine dermal collagen and 0.4 mL 5× DMEM (Sigma, USA) and then making the pH to 7.2–7.5 with NaOH. And 0.2 mL of the cell suspension (containing 5 × 105 cells) was added to the dermal collagen solution. Before making collagen mixture, six-well plate was coated with BSA for 1 h in incubator. Place the 2 mL collagen mixture into a well of the six-well plate, then, BSA was removed. Collagen lattices were allowed to gel for 60 min in an atmosphere with 95% air and 5% at 37 °C. After 60 min, the collagen lattices were detached from the surface of the well by rimming the lattice with a sterile spatula. The 4 mL of serum–free medium (SFM) was added to each well. And the rate of contraction was determined by measuring lattice diameter at predetermined time.

Confocal immuno-fluorescence analysis

The cells were plated in 8-well-slide glass at 2.0 × 104cells/well (250 µL) confluence and grown for 16 h. After scratching with 0.5–10 µL micro tips, the cells were cultured with and without Pal-KTTKS for 6 h in incubator. And then tested fibroblast samples were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 1 h and washed twice in PBS and then placed in 1% Triton X-100 (300 µL/well) for 15 min and blocked with 10% FBS for 1 h at room temperature. Following sample preparation, immunohistochemistry was performed for the detection of a-SMA using indirect immunofluorescence with the primary antibody against a-SMA, monoclonal anti-a-SMA-Cy3 conjugated (Sigma, USA) at a dilution of 1:200 in FBS for 16 h in incubator. Slides were washed twice in PBS. Treated samples were exposed to 4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylinodole (DAPI) (Sigma, USA) staining solution at a dilution of 1:5000 for 1 min. DAPI is a blue fluorescent nuclear stain, and this step was ensured to visualize nuclei. The slides were washed twice in PBS, mounted in antifade reagent 10 µL and fixed it with cover slips. Images were viewed with a confocal laser-scanning microscope, Zeiss Laser Confocal Microscope (ZEISS-LSM 700, Jena, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Numerical results are presented as the mean ± SD of all experiments. Mean values were tested by a Student’s t test. Differences were considered to be statistically significant at p values p < 0.05 indicated by an asterisk (**). The positive linear correlation between fibroblast contraction and α-SMA expression was statistically tested.

Results

Effect of KTTKS on the trans-differentiation of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts

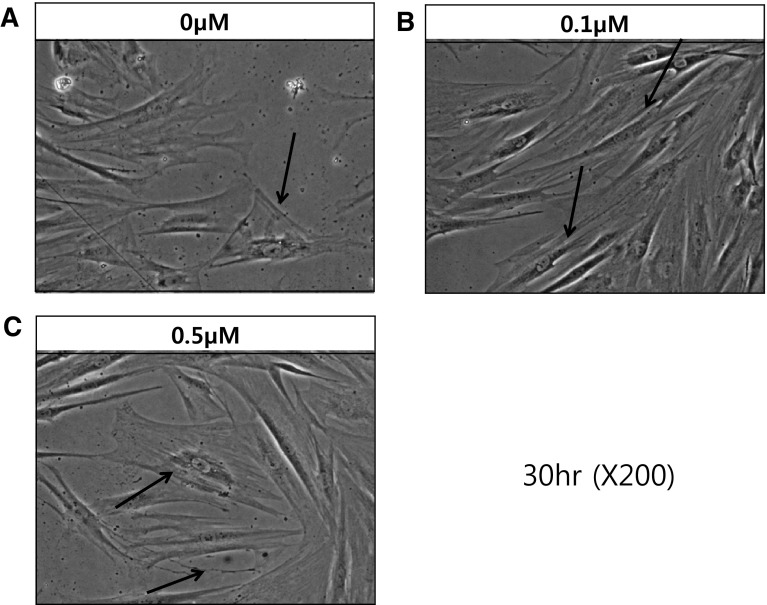

Effect of Pal-KTTKS on the trans-differentiation of fibroblast to myofibroblast was investigated in human dermal fibroblast wound model. Figure 1A–C show phase contrast Images of scratched dermal fibroblasts at 30 h post injury time without (0 µM) or with Pal-KTTKS treatment (0.1 or 0.5 µM). In serum-free media (SFM), Pal-KTTKS untreated conditions, large squamous polygonal myofibroblasts (arrow) were observed (Fig. 1A). In Pal-KTTKS treated cells (0.1 µM)), mostly typical biaxial spindle-shaped fibroblasts (arrow) were observed (Fig. 1B). This result clearly demonstrates the inhibitory effect of Pal-KTTKS (0.1 µM) on the trans-differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. However, Fig. 1C shows the enlarged squamous myofibroblast cells (arrow) still present at higher dose of Pal-KTTKS (0.5 µM).

Fig. 1.

Differences in cell morpholohy: phase contrast images of wounded dermal fibroblasts at 30 h post injury without Pal-KTTKS serum free media (A), 0.1 µM Pal-KTTKS treatment (B) and 0.5 µM Pal-KTTKS treatment (C). A representative image is shown from three replicates (n = 3)

Effect of KTTKS on the expression of cytokines

Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF)

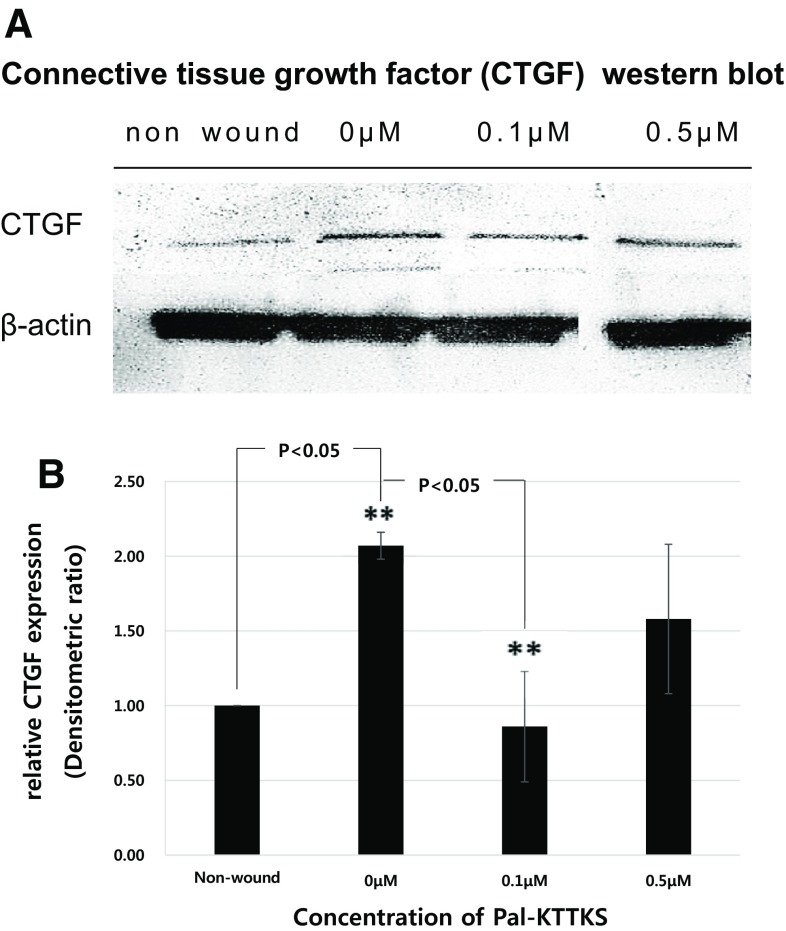

Figure 2A shows western blot analysis of CTGF in fibroblasts in response to different concentrations of Pal-KTTKS treatment (0–0.5 µM). Non-wounded (normal) cells express negligible CTGF. CTGF level increased 2.1-fold in wound cells and the level of CTGF was reduced in Pal-KTTKS treated cells. Expression of CTGF relative to β-actin, normalized to non-wound is summarized in Fig. 2B. The expression of CTGF was reduced in low doses (0.1 µM) of Pal-KTTKS treated cells. And the extent of CTGF inhibition was leveled down as the Pal-KTTKS concentration was further increased to 0.5 µM.

Fig. 2.

Western blot analysis of CTGF expression in wounded fibroblasts in response to different concentrations of Pal-KTTKS (A). Each panel represents relative CTGF expression in different concentrations of Pal-KTTKS treated (0–0.5 µM) wound fibroblast group as compared with normal, un-wounded fibroblasts (B). Statistical significances between Pal-KTTKS untreated and treated groups were evaluated using Student’s t test. Bars represent mean ± SEM of three replicates per treatment conditions (**statistically different from Pal-KTTKS untreated group (0 µM), p < 0.05)

Alpha smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)

Effect of Pal-KTTKS on α-SMA expression was studied at different concentration ranges (0–0.5 µM). To understand how the scratch wound condition increase the a-SMA expression, un-wounded fibroblasts were studied as a comparison. Figure 3A shows western blot analysis of α-SMA in fibroblasts in response to different concentrations of Pal-KTTKS treatment. Non-wounded (normal) cells express negligible α-SMA. Wounded fibroblasts up regulate a-SMA expression more than twofold. Expression of a-SMA relative to ß-actin, normalized to non-wound is summarized in Fig. 3B. The expression of α-SMA was reduced by 62% (p < 0.05) in 0.1 µM treated cells as compared to non treatment (0 µM).

Fig. 3.

Western blot analysis of α-SMA expression in wounded fibroblasts in response to different concentrations of Pal-KTTKS (A). Primary dermal fibroblasts from female human forehead were grown to 80% confluence on 100 mm tissue culture plates, and serum/growth factor starved for 4 h. Semiconfluent cultures were treated with Pal-KTTKS. Expression levels of α-SMA are represented relative to normal, non wound control (B). Bars represent mean ± SEM of three replicates per treatment conditions (**significantly different from Pal-KTTKS untreated control (p < 0.05)

Collagen lattice contraction

The fibroblast-populated collagen lattice (FPCL) contraction assay was used to examine that Pal-KTTKS could alter fibroblast-mediated contraction of collagen lattices. Figure 4A shows that Pal-KTTKs inhibited FPCL contraction in a dose-dependent manner. Pal-KTTKS treatment (0.1 µM) induced a decrease in contraction rate as compared to the untreated cells. Figure 4B shows the percentage of contraction of FPCL when they were treated with different concentrations of Pal-KTTKS (0–0.5 µM). Without Pal-KTTKS treatment, FPCL maintained its initial diameter (78.59 ± 0.85%). Pal-KTTKS treatment (0.1 µM) maintained its initial diameter (84.92 ± 0.43%). The degree of collagen contraction is correlated with α-SMA expression level.

Fig. 4.

A Representative photographic images of fibroblast-populated collagen lattices (FPCL) after wounding and Pal-KTTKS treatment at 0 and 42 h observation time: non wound; wounded without Pal-KTTKS treatment (0 µM) and wounded with Pal-KTTKS (0.1 µM) treatment. B Percentage of contraction of collagen lattices 24 h after Pal-KTTKS treatment. Relative percentage of collagen contraction in Pal-KTTKS treated (0 to 0.5 µM) and without Pal-KTTKS treated groups are statistically different with 95% confidence interval (p < 0.05). Whereas, at high concentration of Pal-KTTKS treated group (0.5 µM), no statistically significant differences as compared to control was observed. Bars represent mean ± SEM of three replicates per treatment conditions (**significantly different from Pal-KTTKS untreated (0 µM) wound fibroblasts, p < 0.05)

Confocal immunofluorescence analysis

Myofibroblasts are highly contractile cells with prominent stress fibers. Expression of α-SMA is considered as the most reliable marker of myofibroblasts [16, 20]. Confocal immune-fluorescence analysis was conducted to observe the expression of α-SMA.

Figure 5A shows representative confocal sections of immune-fluorescence staining for α-SMA (red) and nuclear staining (blue) with DAPI. Normal, non wound cells exhibit basal negligent level of α-SMA staining (Nonwound), while the untreated cells (0 µM) exhibited cellular hypertrophy and squamous morphology with strong staining of α-SMA and more pronounced actin stress fibers. In the overlaid confocal sections without Pal-KTTKS treatment, abundance of α-SMA were presented (75.0 ± 7.1%, n = 3). Pal-KTTKS treated (0.1 µM) cells show negligible α-SMA staining. In higher concentration (0.5 µM) of Pal-KTTKS treated cells, α-SMA positive stress fibers were increased. Calculation of the α-SMA expression ratio (number of α-SMA expressed cells/number of DAPI stained cells) was summarized in Fig. 5B. The expression of α-SMA was dependent on the concentration of Pal-KTTKS treatment. After scarring, α-SMA expressing cells increased to twofold (p < 0.05) and Pal-KTTKS treatment (0.1 µM) reduced the level of α-SMA to (38.6 ± 16.1%, n = 3, p < 0.05) as compared to untreated cells. The extent of α-SMA inhibition was leveled down as the Pal-KTTKS concentration was further increased to 0.5 µM.

Fig. 5.

A Confocalimmunofluorescence analysis (X20, confocal microscopy (ZEISS-LSM700), blue; DAPI, Red; Cy3) Fibroblast differentiation to myofibroblast phenotype is characterized by the expression and assembly of smooth muscle actin into stress fibers. Immunohistochemical staining for α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) on day 9, using a diaminobenzidine (DAB) detection system, demonstrates a reduction in the number of α-smooth muscle actin expressing cells after Pal-KTTKS treatment (0.1 µM) compared with no treatment (0 µM) and higher concentration of Pla-KTTKS treatment (0.5 µM). All images are representative of three independent experiments. B Effect of Pal-KTTKS on α-SMA expression in confocal analysis. α-SMA expression ratio (number of α-SMA expressed cells/number of DAPI stained cells) was summarized. The expression of α-SMA was dependent on the concentration of Pal-KTTKS treatment. After scarring, α-SMA expressing cells increased to 2.1 fold (p < 0.05) and Pal-KTTKS treatment (0.1 µM) reduced the level of α-SMA to (38.6 ± 16.1%, n = 3, p < 0.05) as compared to untreated cells. The extent of α-SMA inhibition was leveled down as the Pal-KTTKS concentration was further increased to 0.5 µM. Bars represent mean ± SEM of three replicates per treatment conditions (**significantly different from Pal-KTTKS untreated (0 µM) wound fibroblasts, **p < 0.05)

Discussion

Collagen is the most abundant protein in mammals and it is a key component of the extracellular matrix [23]. Controlling its production is the key element in tissue regeneration. In regenerative healing (without scarring), myofibroblast usually disappear by apoptosis. However, in pathological states such as hypertropic scars, the persistence of myofibroblasts contributes to overproduction of extracellular matrix (ECM), excessive α-SMA expression and contraction. To reduce the size of an open wound without scarring, delicate balance between the formation of connective tissue and degradation of excessive extracellular collagen matrix deposition is crucial [24, 25]. As the crucial balance between collagen production and breakdown disrupted, proliferative scarring occurred. Rinkevich and coworkers investigated the effects of inhibiting dipeptidyl peptidase, a cell surface serine exopeptidase on scar formation during wound healing using a small molecule (diprotin A) and observed that faster wound closure implies that there are higher extra collagen matrix disposition (scar) occurs [26]. Mas-Chamberlin proposed a very insightful explain how breakdown product of collagen can play a role in wound healing process. He claimed that nature is economical and we can learn from her. During the wound healing process, macromolecules such as collagen, elastin, are broken down into smaller fragments by collagenase, elastase. The break-up of collagen is not random, however, oligopeptide fragments of defined amino acid sequence are released with biological signaling activity like local hormones [27]. Some specific fragments either stimulate or inhibit collagen neo-synthesis in the fibroblasts to speed up the tissue repair process. The less inhibitory effect at high concentration (0.5 µM) of Pal-KTTKS treated group correlates with faster wound closure and higher α-SMA expression [25]. The role of Pal-KTTKS in relation to growth factors and cell migration during wound healing needs further investigation. Our study claims for optimizing dose of Pal-KTTKS for anti scar therapy. Future studies focusing on the concentration range from 0.01 to 1.0 µM of Pal-KTTKS and understanding the self-assembling nano-fibrillar structure of this amphiphilic peptide and its structural transition and its extracellular matrix degradation property depending on concentration [28, 29] could provide us an insight to determine how delicate balance between the wound healing properties and pro-fibrotic abilities of pentapeptide KTTKs is achieved. In addition, considering significant barrier property of stratum corneum, the outer most layer of the skin and extensive protease present in dermis, dermal bioavailability of Pal-KTTKS should be very minimal [30]. In this sense, topical application of high concentration of Pal-KTTKS may not cause serious adverse effects. However, when Pal-KTTKs is administered as an injection or micro-needle type delivery system, which can directly expose this collagen stimulating penta-peptide (KTTKS) to the dermis, dose should be carefully considered.

In conclusion, Pal-KTTKS (0.1 µM), a pentapeptide from type I procollagen reduces α-SMA expression and trans-differentiation of fibroblasts to myofibroblast. The degree of reduction is dose-dependent. At higher concentration (0.5 µM) of Pal-KTTKS, pro-fibrotic mediator, α-SMA expression remains high. Delicate balance between the wound healing properties and pro-fibrotic abilities of pentapeptide KTTKS should be considered for selecting therapeutic dose for wound healing.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Duksung Women’s University Research Grants 2014. We thank Prof. Kyung Chan Park at Department of Dermatology, School of Medicine, Seoul National University for his valuable discussion and for providing primary human dermal fibroblasts.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest with any person or any organization.

Ethical statement

There are no animal experiments carried out for this study.

References

- 1.Katayama K, Armendariz Borunda J, Raghow R. A pentapeptide from type 1 procollagen promotes extracellular matrix production. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9941–9944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castelletto V, Hamley IW, Perez J, Abezgauz L, Danino D. Fibrillar superstructure from extended nanotapes formed by a collagen-stimulating peptide. Chem Commun. 2010;46:9185–9187. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03793a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsai WC, Hsu CC, Chung CY, Lin MS, Li MS, Pang JH. The pentapeptide KTTKS promoting the expressions of type 1 collagen and transforming growth factor-β of tendon cells. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:1629–1634. doi: 10.1002/jor.20455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones RR, Castelletto V, Connon CJ, Hamley IW. Collagen stimulating effect of peptide amphiphile C-16-KTTKS on human fibroblasts. Mol Pharm. 2013;10:1063–1069. doi: 10.1021/mp300549d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Juan FM, Beatriu E, Maria DS-M, Marta TS, Ian WH, Ashkan D, et al. Self-assembly of a peptide amphiphile: transition from nanotape fibrils to micelles. Soft Matter. 2013;9:3558–3564. doi: 10.1039/c3sm27899a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farwick M, Grether-Beck S, Marini A, Maczkiewitz U, Lange J, Kohler T, et al. Bioactive tetrapeptide GEKG boosts extracellular matrix formation: in vitro and in vivo molecular and clinical proof. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20:600–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maquart FX, Pasco S, Ramont L, Hornebeck W, Monboisse JC. An introduction to matrikines: extracellular matrix-derived peptides which regulate cell activity implication in tumor invasion. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2004;49:199–202. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2003.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roanne RJ, Valeria C, Che JC, Ian WH. Collagen stimulating effect of peptide amphiphile C16-KTTKS on human fibroblasts. Mol Pharm. 2013;10:1063–1069. doi: 10.1021/mp300549d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abu Samah NH, Heard CM. Topically applied KTTKS: a review. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2011;33:483–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2494.2011.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reid R, Mogford JE, Butt R, Miller AG, Mustoe T. Inhibition of procollagen C-proteinase reduces scar hyperthrophy in a rabbit model of cutaneous scarring. Wound Rep Regen. 2006;14:138–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang M, Huang H, Li J, Huang W, Wang H. Connective tissue growth factor increases matrix metalloproteinase-2 and suppresses tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-2 production by cultured renal interstitial fibroblasts. Wound Rep Regen. 2007;15:817–824. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alfaro MP, Deskins DL, Wallus M, DasGupta J, Davidson JM, Nanney LB, et al. A physiological role for connective tissue growth factor in early wound healing. Lab Invest. 2013;93:81–95. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2012.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frazier K, Williams S, Kothapalli D, Klapper H, Grotendors GR. Stimulation of fibroblast cell growth, matrix production and granulation tissue formation by CTGF. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;107:404–4011. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12363389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leask A, Holmes A, Abraham DJ. Connective tissue growth factor: a new and important player in the pathogenesis of fibrosis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2002;4:136–142. doi: 10.1007/s11926-002-0009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sonnylal S, Shi-wen X, Leoni P, Naff K, Van Pelt C, Nakamura H, et al. Selective expression of CTGF in fibroblasts in vivo promotes systemic tissue fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1523–1532. doi: 10.1002/art.27382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hinz B. Formation and function of the myofibroblast during tissue repair. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:526–537. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hinz B, Celetta G, Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Chaponnier C. Alpha-smooth muscle actin expression upregulates fibroblast contractile activity. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:2730–2741. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.9.2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabbiani G. The myofibroblast in wound healing and fibrocontractive diseases. J Pathol. 2003;200:500–503. doi: 10.1002/path.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daniels JT, Schultz GS, Blalock TD, Garrett Q, Grotendorst GR, Dean NM, et al. Mediation of transforming growth factor-β1-stimulated matrix contraction by fibroblasts: a role for CTGF in contractile scarring. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:2043–2052. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63562-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Desai VD, Hsia HC, Schwarzbauer JE. Reversible modulation of myofibroblast differentiation in adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e86865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans RA, Tian YC, Steadman R, Phillips AO. TGF-1-mediated fibroblast-myofibroblast terminal differentiation—the role of Smad proteins. Exp Cell Res. 2003;282:90–100. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4827(02)00015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moon HK, Yong HY, Cho Lee AR. Optimum scratch assay condition to evaluate CTGF expression for anti-scar therapy. Arch Pharm Res. 2012;35:383–388. doi: 10.1007/s12272-012-0220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang J, Sato T. Effect of type I collagen derivative from Tilapia Scale on odontobalst-like cells. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2015;12:231–238. doi: 10.1007/s13770-014-0114-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diegelman RF, Evans MC. Wound Healing: an overview of acute, Fibrotic and delayed healing. Front Biosci. 2004;9:283–289. doi: 10.2741/1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boris H, Giuseppe C, James JT, Giulio G, Christine C. Alpha-smooth muscle actin expression upregulates fibroblast contractile activity. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:2730–2741. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.9.2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rinkevich Y, Walmsley G, Hu M, Maan A, Newman A, Drukker M, et al. Identification and isolation of a dermal lineage with intrinsic fibrogenic potential. Science 2015;348(6232). doi:10.1126/science.aaa2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Mas-Chamberlin C, Mondon P, Peschard O, Lintner K. Matrikine technology and barrier repair: the ultimate in anti-age skin care? Cosmetic Sci Technol 2004;53.

- 28.Dehsorkhi A, Castelletto V, Hamley IW. Self-assembling amphiphilic peptides. J Pept Sci. 2014;20:453–467. doi: 10.1002/psc.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maquart FX, Bellon G, Pasco S, Monboisse JC. Matrikines in the regulation of extracellular matrix degradation. Biochimie. 2005;87:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi YL, Park EJ, Kim E, Na DH, Shin YH. Dermal stability and in vitro skin permeation of collagen pentapeptides (KTTKS) Biomol Ther. 2014;22:321–327. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2014.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]