Abstract

Autologous disc cell transplantation (ADCT) is a cell-based therapy aiming to initiate regeneration of intervertebral disc (IVD) tissue, but little is known about potential risks. This study aims to investigate the presence of structural phenomena accompanying the transformation process after ADCT treatment in IVD disease. Structural phenomena of ADCT-treated patients (Group 1, n = 10) with recurrent disc herniation were compared to conventionally-treated patients with recurrent herniation (Group 2, n = 10) and patients with a first-time herniation (Group 3, n = 10). For ethical reasons, a control group of ADCT patients who did not have a recurrent disc herniation was not possible. Tissue samples were obtained via micro-sequestrectomy after disc herniation and analyzed by micro-computed tomography, scanning electron microscopy, energy dispersive spectroscopy, and histology in terms of calcification zones, tissue structure, cell density, cell morphology, and elemental composition. The major differentiator between sample groups was calcium microcrystal formation in all ADCT samples, not found in any of the control group samples, which may indicate disc degradation. The incorporation of mineral particles provided clear contrast between the different materials and chemical analysis of a single particle indicated the presence of magnesium-containing calcium phosphate. As IVD calcification is a primary indicator of disc degeneration, further investigation of ADCT and detailed investigations assessing each patient’s Pfirrmann degeneration grade following herniation is warranted. Structural phenomena unique to ADCT herniation prompt further investigation of the therapy’s mechanisms and its effect on IVD tissue. However, the impossibility of a perfect control group limits the generalizable interpretation of the results.

Keywords: Recurrent disc herniation, Regenerative therapy, Disc calcification, Intervertebral disc

Introduction

Approximately 40% of disc herniation patients develop chronic lower back pain following micro-sequestrectomy [1, 2]. Regenerative therapies provide new treatment options to replace conservative treatment and reconstructive surgeries for treating intervertebral disc degeneration (IDD) [3, 4]. Evaluation of these new treatments is based on clinical symptoms, patient conditions, and the current biological stage of the disc assessed by the MRI-based Pfirrmann grading scheme [5].

For the early stages of disc degeneration, a protein injection of growth factor is occasionally considered as a promising method of treatment [6], as it stimulates extracellular matrix production; however, a cell therapeutic approach also appears promising [7]. For grade IV or V degeneration, several treatment options are under investigation [8], including gene therapies which provide a more prolonged mode of growth factor delivery, as well as direct cell therapies through various types of cells [9, 10]. Most of these new treatment options are the subject of basic science and preclinical studies. However, regenerative therapies present a promising approach for the treatment of chronic back pain caused by a herniation of a lumbar intervertebral disc (IVD).

Autologous disc cell transplantation (ADCT) based therapies are currently one the most advanced treatment options and two ADCT approaches are being clinically tested [11–14]. For both approaches, cells from the anulus fibrosus (AF) and nucleus pulposus (NP) tissue sequestered from the spinal canal are isolated by enzymatic digestion via incubation with collagenase. A mix of AF and NP cells are then cultivated until a sufficient amount of cells are achieved [15]. The cells are then harvested to create the cell graft. Depending on the application form, the approach and cell grafts differ for reinjection.

The latest approach is still in phase 1 trials and injects the cells together with a scaffold material [14]. The scaffold material is an in situ polymerizing gel [13]. 12 patients were treated in the trial, with a reherniation occurring in one case after 7 months [13].

A second, older approach is the application of a pure cell suspension in NaCl, as is the case for the product chondrotransplant® DISC. Previous preclinical studies of this second approach using a canine model have suggested that ADCT [10, 16] is able to initiate regeneration [12, 17]. The first clinical trial of ADCT [11] was published in 2006 for the cell-based chondrotransplant® DISC and included 12 patients meeting the following criteria: age 18–60 years, body mass index (BMI) <28, single affected inter vertebral disc, and low grade IDD [11]. Another 8 patients were treated in a later study by the same method [18].

The results of these studies demonstrated total exclusion of responsive immune reactions, no inflammatory complications, and increased water content [11, 18]. The rate of recurrent herniation was reportedly reduced in these trials, while cancerous neoplasm formation was not observed.

Despite these published successes, disc reherniation following treatment can still occur. Therefore, the present study investigates which pathological changes occur in the disc as part of the incidence of recurrent herniation by analyzing disc sequester tissue. Due to the limited amount of tissue (approximately 1–2 cm3 worth) [19] available via sequestrectomy following disc prolapse, this study focused on analyzing morphological abnormalities in IDD tissue. Information on known degeneracy characteristics such as indicative cellular distribution [20, 21], cell morphology [22], matrix structure [23], and calcification [24] was collected and evaluated. Calcification of the intervertebral disc in particular is a well-established characteristic of degeneration [24–26].

The aim of this study is to provide a microstructural comparison of human tissue samples after: recurrent disc herniation following ADCT treatment (Group 1, n = 10), recurrent disc herniation without ADCT (Group 2, n = 10), and initial disc herniation (Group 3, n = 10), as well as a detailed chemical analysis of embedded mineral particles.

Materials and methods

Patient population

Tissue samples with a volume of 1–2 cm3 were evenly bisected into one half for histological examinations and the other for µ-CT, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS).

An analysis of Group 1 samples after the first herniation could not be conducted due to the tissue volume requirements and guidelines of the ADCT technique; Group 3 samples were collected and analyzed as an analogous control for this time step. All control group patients also met the inclusion conditions for an ADCT treatment trial and have comparable age and BMI [11, 27]. All patients were operated on explicitly due to a motor-function failure and received treatment no more than 72 hours after the appearance of symptoms. The mean age of all patients is 35.08 ± 2.78 years; Table 1 lists further detailed descriptions of the three patient groups. Patients were assessed via MRI performed with a Philips Achieva 1.5T scanner and scored using the Pfirrmann scale (grades I–V) [5], with all patients exhibiting grade V degeneration.

Table 1.

Overview of the patient group clinical data and treatments

| Parameter | Group 1 ADCT group | Group 2 conventional recurrent treatment group | Group 3 conventional treatment group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group size | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Sex | 4 female/6 male | 4 female/6 male | 3 female/7 male |

| Age | 36.7 ± 1.6 | 34.8 ± 2.9 | 34.7 ± 3.1 |

| BMI | 26.1 ± 2.2 | 26.5 ± 3.9 | 24.8 ± 3.3 |

| Level | 7 × L4/L5 and 2× L5/S1 | 7 × L4/L5 and 3× L5/S1 | 8 × L4/L5 and 2× L5/S1 |

| Recurrent herniation | Yes | Yes | No |

| Treatment | Micro-sequestrectomy | Micro-sequestrectomy | Micro-sequestrectomy |

| ADCT injection | – | – | |

| Microsequestrectomy | Microsequestrectomy | – | |

| Weeks between herniations | 17 … 77 Mean 37 ± 26.7a |

10 … 122 Mean 25.2 ± 29.6a |

– |

aThe values are not normally distributed

All tissue samples were collected as part of a clinical study investigating microstructural changes during aging and IDD.

ADCT technique

After surgery, tissue sequesters were sent in whole to the sole ADCT manufacturer CO.DON AG (Teltow, Germany) for synthesis of the chondrotransplant® DISC therapeutic agent. As the sequestrum in its entirety was required for production of the ADCT drug, it was impossible to perform analysis of the tissue before it was sent to the manufacturer. The therapeutic agent was subsequently received and stored under cryogenic conditions until treatment. The cell graft is an externally provided physiological saline cell-suspension solution that was injected with a SPROTTE® cannula (PAJUNK Medical, Geisingen, Germany) by the attending surgeon.

Histology

For all three groups, one piece of each relevant tissue sample was fixed in 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde (Carl Roth GmbH & Co.KG, Germany), dehydrated using a soaking series of ethanol dilutions (Carl Roth GmbH & Co.KG, Germany), embedded in paraffin wax (Carl Roth GmbH & Co.KG, Germany) and cut into 5 µm thick slices. Samples were stained with a modified von Kossa staining to identify possible calcium deposits [24, 28, 29]. A minimum of ten different slides per patient were imaged via light microscopy, examining dark brown stained regions of calcium deposits. Images of the slides were taken at 40× and 100× magnification.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The remaining piece of sequester tissue from each patient was fixed using 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde, rinsed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (c.c.pro GmbH, Germany), post-fixed with 0.5% (v/v) osmium tetroxide (Carl Roth GmbH & Co.KG, Germany), rinsed with PBS again, and then dehydrated via ethanol soaking series. Samples were then “Spurr” resin-embedded [30]. The resin blocks were abraded and polished to form a cross section of the tissue, then sputter coated with a 2–3 nm platinum layer. SEM investigations were performed in a FEI Quanta 3D microscope using a back-scattered electron detector (FEI, Eindhoven, Netherlands). The prepared tissue samples were then investigated regarding tissue structure, cell density, and cell morphology using the commercial software cellF (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions, Münster, Germany). Afterwards, the sample was abraded by another 50 microns, polished, and sputtered before re-imaging. This procedure was repeated for ten different levels.

Energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS)

Chemical characterization of sample tissue areas selected by SEM was performed via energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDAX Inc., Mahwah, NJ, USA) in a Jeol JSM-7401F high-resolution SEM (JEOL USA, Inc., Peabody, MA, USA) by engaging the EDS mode to produce an energy dispersive X-ray spectrum. This allowed for identification and quantification of the each sample’s elemental composition at various locations. The sample was examined by spot and surface area analyses at an acceleration voltage of 30 keV. Signal offset was determined by analysis of pure embedding resin. The separation of osmium and phosphorus peaks was conducted by unfolding the spectra in the analysis software TEAM™ EDS (EDAX Inc., Mahwah, NJ, USA) [31].

µ-CT/Nano-CT examination of intervertebral disc samples

A phoenix nanome|x 180NF (GE, USA) source with a nano-focus X-ray cone-beam and fixed stand detector with 512 × 512 pixels was used to examine material contrast differences of minute objects in tissue samples with high spatial resolution [32]. Soft tissue structures could also be investigated, as samples were previously osmium-contrasted for SEM. Eleven images were collated by the detector for each of the 500-image pattern steps over a 360° rotation using an acceleration voltage of 100 kV, beam current of 100 µA, and 400 ms exposure time. With a resulting voxel size of 25 microns, visualization of individual inclusions, e.g. calcification zones, was possible with high X-ray density [32].

Statistical data analysis

Results of the calcification analysis for each of the tissue samples provide a purely binary result (calcification 0; no calcification 1), representing a simple Bernoulli distribution. The cell density and extracellular matrix size of each patient were recorded across the 10 histological and SEM image locations analogous to the methods presented in [19]. The mean value and standard deviation for each of the three patient groups was then calculated. Significance was determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a 95% confidence interval (significance level p < 0.05) to identify any intercorrelations.

Results

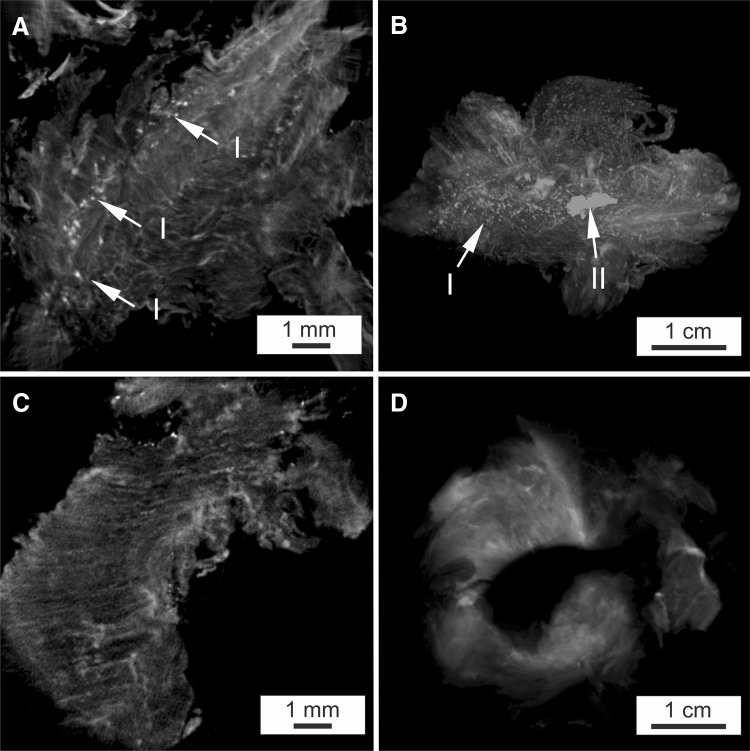

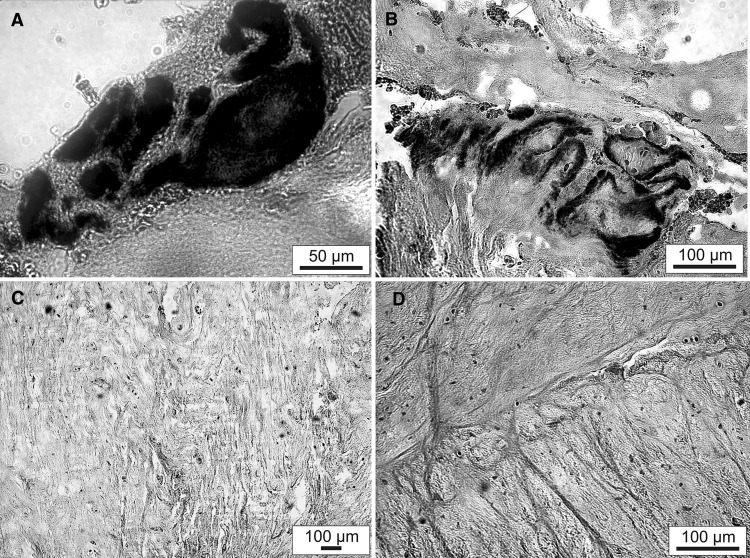

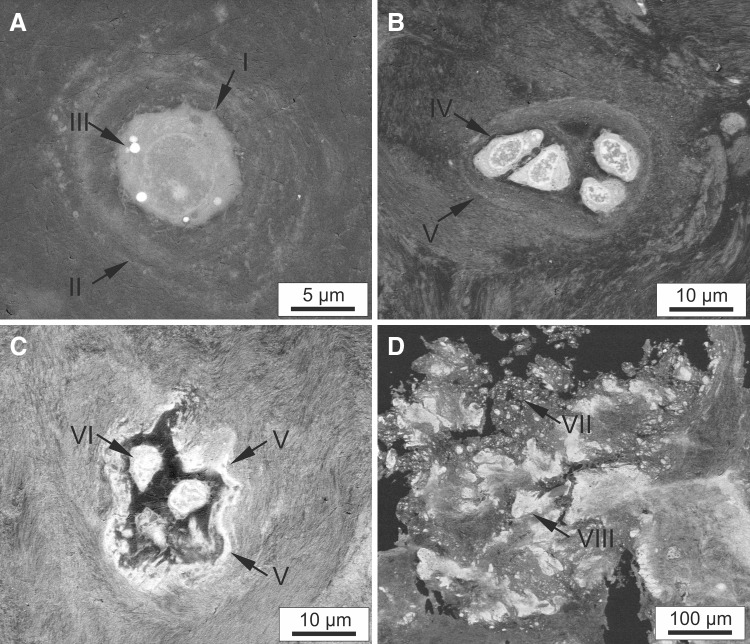

As visible in the MRI images (Fig. 1A, B), stabilization of the nucleus pulposus volume from each of the affected discs was achieved immediately following ADCT injection after the first disc herniation for all patients. Despite this, long-term success was elusive as recurrent disc herniation occurred in these patients. In addition, one ADCT patient formed a type-1 Modic change over the prolapsed time period (Fig. 1B). Contrary to the clinical and radiological findings of the tissue structure, which exhibit no concerning abnormalities, the μ-CT studies (Fig. 2) display a substantial difference in X-ray contrast between individual samples. Such a large difference could be investigated by osmium staining the sample to visualize individual collagen structures. However, none of the samples demonstrated a definitive orientation of tissue structures. Group 1 patient samples also exhibited distinct areas of greatly increased radiopacity that varied in size from a few microns (the device’s resolution limit) to several millimeters in size (Fig. 2A). Additionally, circular and elliptical particles exhibited a non-uniform distribution across the Group 1 samples, as demonstrated through 3D reconstruction (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, such particles were not observed in the cross sections of conventionally-treated patients (Fig. 2C). Figure 2D shows the sequestrum from the recurrent herniated disc of a Group 2 patient. Histological analysis of finely cut sample sections was conducted to highlight possible calcium deposits. Prepared tissue samples from Group 1 patients contained stained particles varying from 1 (Fig. 3A) to 10 µm (Fig. 3B), indicating possible calcium deposits. In comparison, the two sections prepared from tissue samples of Group 2 and Group 3 patients displayed no evidence of calcium particles (Fig. 3C, D).

Fig. 1.

A T2-MRI images of a representative group-1 patient: (left) the situation before micro-sequestrectomy of L4/5; (middle) slight increase in volume and water content by ADCT injection in L4/5; (right) recrudescence disc herniation of L4/5. B T2-MRI images of a group-1 patient with additional Modic changes: (left) the situation before micro-sequestrectomy of L5/S1 Modic Type I; (middle) slight increase in volume and water content by ADCT injection in L5/S1 Modic Type I; (right) recrudescence disc herniation of L5/S1 Modic Type I and increased zone of edema; C Representative T2-MRI images of an group-2 patient: (left) the situation before micro-sequestrectomy of L5/S1; (right) recrudescence without ADCT treatment. D T2-MRI image of a representative group-3 patient, the situation before micro-sequestrectomy L5/S1

Fig. 2.

μCT images of osmium contrasted disc tissue samples, A μCT cross-section of ADCT- treated patient, marked by I small particles with a diameter of 1 μm; B 3D reconstruction of ADCT-treated patient, marked by II large particles with a diameter of 10 μm; C μCT cross-section of conventionally treated patient–first herniation; D μCT cross-section of conventionally treated patient–second herniation

Fig. 3.

Light microscopy image of von Kossa staining of disc tissue removed by sequestrectomy after: A Recurrent disc herniation of an ADCT-treated patient (group-1); B Recurrent disc herniation of an ADCT-treated patient (group-1); C Recurrent disc herniation of a conventionally treated patient (group-2); D Single disc herniation of a conventionally treated patient (group-3)

For all included ADCT-treated patients (Group 1), the examination result was calcification (denoted as ‘0’), as evaluated by both µCT and von Kossa staining. All patients in both control groups (Group 2, Group 3) exhibited no calcification (‘1’). The probability function of the Bernoulli distribution thus provides a trivial result of q = 1 for p = 0 and q = 0 with p = 1 because calcification was seen in 100% of Group 1 patients and 0% of Group 2 and Group 3 patients.

An irregular distribution of tissue-forming cells was observed in ADCT patient samples. Figure 4a shows the SEM image of a typical cell from a representative Group 3 patient tissue sample. These separate cells are imbedded in the surrounding tissue matrix and evenly distributed throughout the tissue, with a cell density of 35.2 ± 8.6 cells/cm3. Most cells exhibited a spherical shape with a typical diameter for cartilage cells of 9.74 ± 0.86 µm. Newly generated extracellular matrix is also visible in Fig. 4A, arranged in concentric shells around the cell with each successive layer decreasing in thickness. A variety of cell clusters containing multiple, primarily spindle-shaped cells were present in ADCT patients. A comparison of such agglomerates is displayed in Fig. 4B, C, with a pocket formed around the cell cluster in Fig. 4C. Between the individual agglomerated cells, little extracellular matrix is visible. Additionally, no cell clusters larger than 20 × 20 µm in size were visible in Group 1 patients after treatment. The sample in Fig. 4B exhibited substructures of disordered, tightly-packed fibrils with relatively high contrast after osmium staining compared to EDS.

Fig. 4.

Scanning electron microscopy of herniated disc tissue: A Single cell I with surrounding, newly formed extracellular matrix II of the recurrent sequestration tissue of a patient after conventional treatment (group-3). At III strong material contrast due to fat accumulation; B Cell agglomerate with spindle-shaped cells IV embedded in dense matrix tissue V in recurrent sequester tissue after ADCT (group-1); C Cell agglomerate strongly contrasted with the surrounding area in recurrent sequester tissue after ADCT treatment (group-1); D Individual particles (VII small particles with a diameter of 1 µm and VIII large particles with a diameter of 10 µm) with no apparent substructure in recurrent sequester tissue after ADCT (group-1)

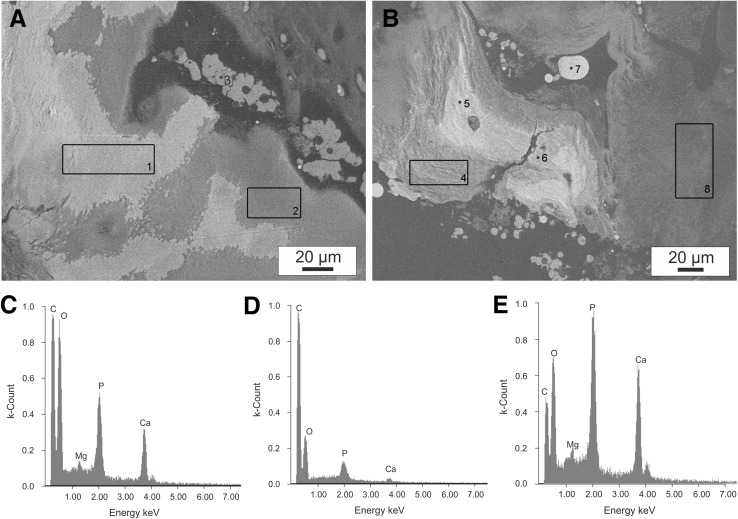

EDS analyses were performed at various tissue locations, determined through osmium detection in the local tissue, to ascertain particle composition (Fig. 5A, B). Table 2 shows the elemental distribution observed in a representative Group 1 patient; elemental composition results for all of the ADCT patients were comparable. Proportional amounts of carbon and osmium were detected through the selected staining method. By taking into account higher energy excitation levels, detectable levels of carbon, oxygen, phosphate, calcium, and a negligible concentration of magnesium were observed (Table 2) in a single particle (Fig. 5C). However, analysis of the tissue surface at position 2 (Fig. 5D), selected via SEM imaging of a fibrillar structure, only shows detectable quantities of notably higher carbon and osmium concentrations (Table 2). The peak levels of calcium and phosphate vary between particles (Table 2, position 5). Notably, substantial portions of calcium and phosphate were not detected at points 4, 7, and 8. Additionally, the variation in fractional distribution of osmium, visible in SEM images at points 2, 4, 7 and 8, correlates with a decreasing density of fibrillar tissue components. Conventionally-treated patients also displayed comparable EDS results at points 2, 4, 7, and 8. As previously demonstrated through the SEM and X-ray analyses, no particle inclusions were visible in these patients. The shape of the particles and the high osmium content at position 3 combined with the simultaneous absence of minerals, i.e. the presence of organic matrix, suggests that these are erythrocytes which have not been removed despite thorough washing.

Fig. 5.

Spot and mapping EDS analyses of different tissue regions of a group-1 patient in an SEM image: A, B SEM images with marked analysis positions 1–8 (elemental compositions shown in Table 2); C Spectra for the mapping analysis of the area of a particle 1; D Spectra for the mapping analysis of the surrounding fibrillar tissue area 2; E Spectra for the spot analysis of the particle at position 5

Table 2.

Microanalysis of the elemental compositions (in atom percent) of different sample regions marked in Fig. 5 A, B from one recurrent ADCT patient

| Position | C (at.%) | O (at.%) | Mg (at.%) | Os (at.%) | P (at.%) | Ca (at.%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 53.66 | 30.31 | 1.26 | 1.71 | 4.15 | 8.92 |

| 2 | 78.79 | 17.12 | 0.58 | 2.68 | 0.50 | 0.38 |

| 3 | 84.11 | 11.24 | 0.03 | 4.26 | 0.22 | 0.14 |

| 4 | 74.03 | 19.52 | 0.66 | 1.37 | 1.53 | 2.89 |

| 5 | 34.82 | 28.65 | 2.87 | 3.58 | 8.72 | 21.36 |

| 6 | 37.59 | 28.53 | 2.83 | 3.26 | 8.20 | 19.59 |

| 7 | 83.22 | 10.09 | 1.02 | 4.57 | 0.84 | 0.26 |

| 8 | 83.16 | 15.35 | 0.08 | 1.01 | 0.11 | 0.09 |

The osmium contrast agent and phosphorus were separated by the energetically significant spectral lines

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the presence of structural phenomena that accompany the transformation process after ADCT treatment in IVD disease. Some of the primary findings unique to Group 1 samples were the presence of calcium particles, calcification, and irregular cell distribution and clustering. These sample analyses are particularly valuable, as obtaining tissue samples following ADCT treatment in human patients is inherently difficult due to low incidence and inclusion in clinical trials.

All patients represent a younger age group (30–39 years) with a lower risk of recurrent disc herniation than older individuals (60+ years) [23], though herniation obviously cannot be precluded [33]. In the investigated age group, a herniation event represents approximately 8.8% of the patients treated at our clinic, which falls within the range of previous reportings [34–36]. The average time period between the first disc herniation and reherniation is 25.2 weeks for conventionally-treated patients (Group 2), while the average time between subsequent herniations is 37.0 weeks for ADCT-treated patients (Group 1). However, this difference is not statistically significant as the spread of individual events is too large (Table 1).

The probability of a recurrent disc herniation following ADCT is comparable to conventional treatment [11]. Yet very few clinical applications of the relatively new ADCT therapy have been performed prior to the present study, and with little accompanying literature. Thus, the source of comparable recurrent herniation rates between the two treatments was previously unknown. An inflammatory reaction in the tissue could be excluded as the cause based on previous reports [11]. However, histological examinations did show visible microstructural differences between the patient groups.

Results of calcification analysis are unambiguous: calcification in 100% of ADCT cases (Group 1) and in 0% of control cases (Group 2, Group 3). It should be noted however, that calcification in the populations sampled by Group 2 and Group 3 can occur, if extremely rarely in younger patients [37]. The tissue samples of conventionally-treated patients (Group 2, Group 3) exhibited many of the common characteristics associated with degenerated IVD’s. The tissue samples displayed a substantially decreased cell density, decreased water content, altered extracellular matrix structure, and nonhomogeneous collagen content. However, other characteristics such as spindle-shaped cells, formation of cell clusters, and calcification were not observed. Additionally, cells were uniformly distributed in the extracellular matrix, as has been described for non-degenerated IVD’s. Although the overlapping processes of aging and degradation are consistently interrelated [33, 38, 39], it is notable that all patients in the current study are under 40 years old. As such, age is a lessened factor and it may be concluded that the degenerative process is dominant. Weight-induced degeneration may also be reasonably excluded, as all patients possessed a BMI (25.9 ± 3.3) within the national average range for ‘average weight’. However, a previous study comprised of patients with a BMI greater than 25 observed an increased tendency for disc herniation [40].

Considering the younger age range, typically associated with stronger regenerative capability, these patients are ideal candidates for cell-based therapy and should be particularly inclined to positive outcomes, i.e. no reherniation. The sequestered tissue from Group 1 patients used as a cell source for ADCT was comparable to that of control patients who received conventional treatment (Group 2, Group 3). Thus, the age range, physical condition, and tissue source were positive preconditions for ADCT therapy. ADCT patients displayed positive clinical results immediately following the injection (Fig. 1A, B), demonstrated by slightly increased water content and disc volume. However, permanent stabilization of the affected IVD and restoration of NP water content were unattainable (Fig. 1A, B), indicating that the injected autologous cells were unable to produce water-binding glycosaminoglycans in the extracellular matrix. The number of cells contained in the chondrotransplant® DISC may be a critical factor for future investigation, as this value is not specified for the individual drug and may vary between 1 million and 6 million cells [11, 12]. The manufacturer’s indefinite cell count specifications are problematic when evaluating ADCT treatment. However, independent investigation of the supplied therapeutic agent is contractually prohibited by the manufacturer; the drug in its entirety must be used solely for patient treatment. Estimation of the cell number may only be achieved by evaluating what portion of the minimum 1 million injected cells remain intact and reach the nucleus pulposus region.

Therefore, it is of particular interest to investigate the alterations of injected cells that occur while inside the IVD. The formation of cell clusters and cell agglomerates detected in the ADCT patients may result from two possible explanations: IVD degeneration, as it is a defining characteristic of such [28, 33, 41–43], or the application method. To determine the primary cause, a suspension of cells and physiological saline was injected into the nucleus pulposus using a 22G injection syringe guided to the soft tissues by a 19G puncture needle. Following injection, the extracellular matrix prevented a uniform distribution of cells. The compact disc acts as a filter [28], separating the cells from the saline solution. This irregular distribution over an extended period of time results in insufficient cell nutrition, as mass transport within the degraded nucleus pulposus tissue is severely hampered [44–46]. As such, injection of a large quantity of cells did not result in a functionally adequate quantity of extracellular matrix.

Histological slices and von Kossa staining of Group 1 tissue samples demonstrate the inclusion of mineral particles in cell distribution and matrix density. Additional observations indicate that cell clusters may also act as a seed crystal for onset of calcification. A comparison between positions 5 and 7 (Fig. 5) suggests that the contrast differences seen between SEM and X-ray images may not have resulted solely from calcification. The histological evaluation (Fig. 3), commonly applied through von Kossa staining to detect calcification, offers no definitive classification [47] because the level of calcification is undervalued. The EDS atomic distribution of calcium, phosphate, and oxygen suggests that the particles are primarily composed of hydroxyapatite. At points 1 and 5 the Ca/P ratios of atomic masses are 2.15 and 2.44, respectively. For pure hydroxyapatite crystals the atomic mass ratio has a theoretical value of approximately 1.67 [25]. The possibility of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate microcrystalline deposition (CPPD) is therefore virtually eliminated, as all examined sites exhibit Ca/P atomic mass ratios greater than 1.0. This result supports previous pathological findings of degraded discs [24, 37] collected during clinical post-mortem examinations. Additionally, calcification is also dependent on the degree of IVD degeneration. Calcification occurred in both anulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus tissues in association with endochondral ossification [24]. In contrast, individual cell clusters developed a calcified matrix in ADCT patients, where compact particles are evident with and without the context of endochondral ossification. Furthermore, magnesium whitlockite formation is indicated by the presence of the magnesium peak at point 5 in Fig. 5E. The detection of magnesium whitlockite has primarily been accompanied by CPPD in patients with joint osteoarthritis [48, 49] while having been observed only once in a IDD patient [25]. In the current study, ADCT patients exhibited common abnormalities in terms of existing magnesium whitlockite deposits, as well as the nearly exclusive presence of hydroxyapatite. However, no other symptoms of osteoarthritis were observed. As such, closer observation for the initial signs of osteoarthritis should be considered as an additional procedure for further follow-up examinations. Although detection of CPPD particles could not be explicitly demonstrated in this investigation, it is possible that hydroxyapatite and CPPD may be present in the IVD in parallel [50]. Various symptoms including muscle pain, fever, and motor-sensory disturbances are exhibited by patients and may also provide indications of IVD calcification during childhood development [51]. In a histological control conducted by the manufacturer, no calcification was specified in the first sequester tissue from ADCT patients, which was later used in harvesting cells. This indicates that calcification was promoted after cell therapy administration.

Cellular phenotypic changes must also be considered, under the assumption that they are important related factors in IVD degeneration [52]. The initial condition of the extracted cells should also be considered, as these cells are extracted from a degraded disc. In the current study, all patients exhibited Pfirrmann grade V degradation of the affected discs prior to sequestration. As a result, phenotypic changes already existed in the extracted cells. Observations were described with respect to numerous factors [53] that occur in a variety of altered phenotypes during the degradation process.

Therefore in terms of obtaining cells for therapy, phenotypic changes in the protein matrix, growth factors, and pro-inflammatory cytokines and their receptors were assumed to exist in degenerated disc tissue, as has been widely described in previous literature. Although no studies have investigated increased calcification from cell culturing, phenotypic changes in this respect are conceivable [52]. Additionally, cell proliferation was obtained through a monolayer culture in absence of stimulation. Human disc cells have exhibited a significant decrease in gene expression of aggrecan and Type II and X collagen while retaining the ability to proliferate during monolayer culture. However, these genes were re-expressed when cells were re-cultured in a three-dimensional environment [54]. Therefore, it is questionable whether therapy using dedifferentiated cells can achieve permanent success.

Contrary to expectations for a regenerative therapy, we observed several structural phenomena indicative of degraded discs following ADCT in the patients analyzed. Each ADCT-treated patient with prior disc degeneration exhibited significant calcification of the affected IVD. Previously it was assumed that Modic vertebral endplate and marrow changes represent the main criteria for successful application of ADCT therapy. However, the results here suggest the necessity for detailed investigations after intervertebral disc herniation to assess degeneration grade based on each individual’s Pfirrmann score.

Due to the restriction of a low sample number, qualitative evaluations are only possible to a limited extent. For ethical reasons, it is not justifiable to examine the intervertebral disc tissue of ADCT patients without recurrent intervertebral disc herniation. As such a control group is not available and determining the presence of mineral deposits is only possible with microstructural analysis methods, it cannot be clarified whether ADCT can lead to deposits or whether the presence of deposits leads inevitably to a new intervertebral disc herniation. This limits the results with regard to their general interpretation. However, in all cases where herniation occurs, the results are clear.

A description of the morphological changes in IVD tissue is of particular interest, as it may provide some clarification for the therapy’s failure. Biochemical, pathological, and histological investigations were not possible as the amount of available sample material was limited. However, such investigations should be included as an essential part of further evaluations and development of this therapeutic procedure.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank U. Heunemann, Nico Teuscher, and A. Götz for technical assistance. We also thank Dr. Uwe Spohn and Andreas Cismak for scientific discussions and technical help. We extend special thanks to all the patients who participated in this study. The work presented in this paper was made possible by funding from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, 1315883), the DAAD RISE internship program, and the Whitaker Biomedical Engineering Research Fellowship.

Conflict of interest

This work was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, PtJ-Bio, 0315883) and the DAAD RISE internship program, and the Whitaker Biomedical Engineering Research Fellowship.

Ethical review committee

The study was approved by the independent medical ethical committee as well as the scientific committee from the faculty of medicine Martin-Luther University Halle-Wittenberg and confirmed at 14 July 2010 under approval no. EK-MLU/14072010/hm-bü.

References

- 1.Fanuele JC, Abdu WA, Hanscom B, Weinstein JN. Association between obesity and functional status in patients with spine disease. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27:306–312. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200202010-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hart LG, Deyo RA, Cherkin DC. Physician office visits for low-back-pain—frequency, clinical-evaluation, and treatment patterns from a US National Survey. Spine. 1995;20:11–19. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199501000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bron JL, Helder MN, Meisel HJ, Van Royen BJ, Smit TH. Repair, regenerative and supportive therapies of the annulus fibrosus: achievements and challenges. Eur Spine J. 2009;18:301–313. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0856-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakai D, Andersson GB. Stem cell therapy for intervertebral disc regeneration: obstacles and solutions. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11:243–256. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfirrmann CW, Metzdorf A, Zanetti M, Hodler J, Boos N. Magnetic resonance classification of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:1873–1878. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200109010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masuda K, Imai Y, Okuma M, Muehleman C, Nakagawa K, Akeda K, et al. Osteogenic protein-1 injection into a degenerated disc induces the restoration of disc height and structural changes in the rabbit anular puncture model. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:742–754. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000206358.66412.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, An HS, Tannoury C, Thonar EJ, Freedman MK, Anderson DG. Biological treatment for degenerative disc disease. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;87:694–702. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31817c1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paesold G, Nerlich AG, Boos N. Biological treatment strategies for disc degeneration: potentials and shortcomings. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:447–468. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0220-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganey T, Hutton WC, Moseley T, Hedrick M, Meisel HJ. Intervertebral disc repair using adipose tissue-derived stem and regenerative cells experiments in a canine model. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:2297–2304. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a54157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganey T, Libera J, Moos V, Alasevic O, Fritsch KG, Meisel HJ, et al. Disc chondrocyte transplantation in a canine model: a treatment for degenerated or damaged intervertebral disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28:2609–2620. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000097891.63063.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meisel HJ, Ganey T, Hutton WC, Libera J, Minkus Y, Alasevic O. Clinical experience in cell-based therapeutics: intervention and outcome. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:S397–S405. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0169-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meisel HJ, Siodla V, Ganey T, Minkus Y, Hutton WC, Alasevic OJ. Clinical experience in cell-based therapeutics: disc chondrocyte transplantation—a treatment for degenerated or damaged intervertebral disc. Biomol Eng. 2007;24:5–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bioeng.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tschugg A, Diepers M, Simone S, Michnacs F, Quirbach S, Strowitzki M, et al. A prospective randomized multicenter phase I/II clinical trial to evaluate safety and efficacy of NOVOCART disk plus autologous disk chondrocyte transplantation in the treatment of nucleotomized and degenerative lumbar disks to avoid secondary disease: safety results of Phase I—a short report. Neurosurg Rev. 2017;40:155–162. doi: 10.1007/s10143-016-0781-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tschugg A, Michnacs F, Strowitzki M, Meisel HJ, Thome C. A prospective multicenter phase I/II clinical trial to evaluate safety and efficacy of NOVOCART Disc plus autologous disc chondrocyte transplantation in the treatment of nucleotomized and degenerative lumbar disc to avoid secondary disease: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17:108. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1239-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Josimovic-Alasevic O, Libera J, Siodla V, Meisel HJ (2006). Verfahren zur Herstellung von Bandscheibenzelltransplantaten und deren Anwendung als Transplantationsmaterial, DE Patent DE10, 2004, 043449, A, 1 09 Mar 2006

- 16.Anderson DG, Albert TJ, Fraser JK, Risbud M, Wuisman P, Meisel HJ, et al. Cellular therapy for disc degeneration. Spine. 2005;30:14–19. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000175174.50235.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meisel HJ, Ganey T. Nucleus reconstruction by autologous chondrocyte transplantation. In: Mayer HM, editor. Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery. Berlin: Springer; 2006. pp. 364–373. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grochulla F, Mayer HM, Korge A. Autologous disc chondrocyte transplantation. In: Mayer HM, editor. Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery. Berlin: Springer; 2006. pp. 374–378. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friedmann A, Goehre F, Ludtka C, Mendel T, Meisel HJ, Heilmann A, et al. Microstructure analysis method for evaluating degenerated intervertebral disc tissue. Micron. 2017;92:51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan WC, Sze KL, Samartzis D, Leung VY, Chan D. Structure and biology of the intervertebral disk in health and disease. Orthop Clin North Am. 2011;42:447–464. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobayashi S, Meir A, Urban J. Effect of cell density on the rate of glycosaminoglycan accumulation by disc and cartilage cells in vitro. J Orthop Res. 2008;26:493–503. doi: 10.1002/jor.20507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams MA, Roughley PJ. What is intervertebral disc degeneration, and what causes it? Spine. 2006;31:2151–2161. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000231761.73859.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chanchairujira K, Chung CB, Kim JY, Papakonstantinou O, Lee MH, Clopton P, et al. Intervertebral disk calcification of the spine in an elderly population: radiographic prevalence, location, and distribution and correlation with spinal degeneration. Radiology. 2004;230:499–503. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2302011842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hristova GI, Jarzem P, Ouellet JA, Roughley PJ, Epure LM, Antoniou J, et al. Calcification in human intervertebral disc degeneration and scoliosis. J Orthop Res. 2011;29:1888–1895. doi: 10.1002/jor.21456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee RS, Kayser MV, Ali SY. Calcium phosphate microcrystal deposition in the human intervertebral disc. J Anat. 2006;208:13–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00504.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melrose J, Burkhardt D, Taylor TKF, Dillon CT, Read R, Cake M, et al. Calcification in the ovine intervertebral disc: a model of hydroxyapatite deposition disease. Eur Spine J. 2009;18:479–489. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0871-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meisel H, Ganey T. Minimally invasive spine surgery. In: Mayer HM, editor. Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery, New York: Springer; 2006. p. 364–73.

- 28.Cevei M, Roşca E, Liviu L, Muţiu G, Stoicănescu D, Vasile L. Imagistic and histopathologic concordances in degenerative lesions of intervertebral disks. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2011;52:327–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mulisch M, Welsch U, editors. Romeis-Mikroskopische Technik. Berlin: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spurr AR. A low-viscosity epoxy resin embedding medium for electron microscopy. J Ultrastruct Res. 1969;26:31–43. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5320(69)90033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reed SJB. Electron Microprobe Analysis and Scanning Electron Microscopy in Geology. 2. Cambridge: University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rutges JP, Jagt van der OP, Oner FC, Verbout AJ, Castelein RJ, Kummer JA, et al. Micro-CT quantification of subchondral endplate changes in intervertebral disc degeneration. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2011;19:89–95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Weiler C, Schietzsch M, Kirchner T, Nerlich AG, Boos N, Wuertz K. Age-related changes in human cervical, thoracal and lumbar intervertebral disc exhibit a strong intra-individual correlation. Eur Spine J. 2012;21:S810–818. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1922-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meredith DS, Huang RC, Nguyen J, Lyman S. Obesity increases the risk of recurrent herniated nucleus pulposus after lumbar microdiscectomy. Spine J. 2010;10:575–580. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miwa S, Yokogawa A, Kobayashi T, Nishimura T, Igarashi K, Inatani H, et al. Risk factors of recurrent lumbar disk herniation a single center study and review of the literature. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2015;28:E265–E269. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e31828215b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shamji MF, Bains I, Yong E, Sutherland G, Hurlbert RJ. Treatment of herniated lumbar disk by sequestrectomy or conventional diskectomy. World Neurosurg. 2014;82:879–883. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2013.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rutges JP, Duit RA, Kummer JA, Oner FC, van Rijen MH, Verbout AJ, et al. Hypertrophic differentiation and calcification degeneration. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2010;18:1487–1495. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vo N, Niedernhofer LJ, Nasto LA, Jacobs L, Robbins PD, Kang J, et al. An overview of underlying causes and animal models for the study of age-related degenerative disorders of the spine and synovial joints. J Orthop Res. 2013;31:831–837. doi: 10.1002/jor.22204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weiler C. In situ analysis of pathomechanisms of human intervertebral disc degeneration. Pathologe. 2013;34:251–259. doi: 10.1007/s00292-013-1813-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiler C, Lopez-Ramos M, Mayer HM, Korge A, Siepe CJ, Wuertz K, et al. Histological analysis of surgical lumbar intervertebral disc tissue provides evidence for an association between disc degeneration and increased body mass index. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:497. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boos N, Weissbach S, Rohrbach H, Weiler C, Spratt KF, Nerlich AG. Classification of age-related changes in lumbar intervertebral discs. Spine. 2002;27:2631–2644. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200212010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson WEB, Eisenstein SM, Roberts S. Cell cluster formation in degenerate lumbar intervertebral discs is associated with increased disc cell proliferation. Connect Tissue Res. 2001;42:197–207. doi: 10.3109/03008200109005650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharp CA, Roberts S, Evans H, Brown SJ. Disc cell clusters in pathological human intervertebral discs are associated with increased stress protein immunostaining. Eur Spine J. 2009;18:1587–1594. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1053-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferguson SJ, Ito K, Nolte LP. Fluid flow and convective transport of solutes within the intervertebral disc. J Biomech. 2004;37:213–221. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9290(03)00250-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang CY, Gu WY. Effects of mechanical compression on metabolism and distribution of oxygen and lactate in intervertebral disc. J Biomech. 2008;41:1184–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soukane DM, Shirazi-Adl A, Urban JP. Computation of coupled diffusion of oxygen, glucose and lactic acid in an intervertebral disc. J Biomech. 2007;40:2645–2654. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bonewald LF, Harris SE, Rosser J, Dallas MR, Dallas SL, Camacho NP, et al. von Kossa staining alone is not sufficient to confirm that mineralization in vitro represents bone formation. Calcif Tissue Int. 2003;72:537–547. doi: 10.1007/s00223-002-1057-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Halverson PB. Calcium crystal-associated diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1996;8:259–261. doi: 10.1097/00002281-199605000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lagier R, Baud CA. Magnesium whitlockite, a calcium phosphate crystal of special interest in pathology. Pathol Res Pract. 2003;199:329–335. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Feinberg J, Boachie-Adjei O, Bullough PG, Boskey AL. The distribution of calcific deposits in intervertebral disks of the lumbosacral spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;254:303–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsutsumi S, Yasumoto Y, Ito M. Idiopathic intervertebral disk calcification in childhood: a case report and review of literature. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2011;27:1045–1051. doi: 10.1007/s00381-011-1431-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao CQ, Wang LM, Jiang LS, Dai LY. The cell biology of intervertebral disc aging and degeneration. Ageing Res Rev. 2007;6:247–261. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu LT, Huang B, Li CQ, Zhuang Y, Wang J, Zhou Y. Characteristics of stem cells derived from the degenerated human intervertebral disc cartilage endplate. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26285. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kluba T, Niemeyer T, Gaissmaier C, Grunder T. Human anulus fibrosis and nucleus pulposus cells of the intervertebral disc—effect of degeneration and culture system on cell phenotype. Spine. 2005;30:2743–2748. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000192204.89160.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]