SUMMARY

Prolonged seizures of SE result from failure of mechanisms of seizure termination or activation of mechanisms that sustain seizures. Reduced GABA-A receptor-mediated synaptic transmission contributes to impairment of seizure termination. However, mechanisms that sustain prolonged seizures are not known. We propose that insertion of GluA1 subunits at the glutamatergic synapses cause potentiation of AMPA receptor (AMPAR)-mediated neurotransmission which helps to spread and sustain seizures.

The AMPAR-mediated neurotransmission of CA1 pyramidal neurons was increased in animals in SE induced by pilocarpine. The surface membrane expression of GluA1 subunit-containing AMPARs on CA1 pyramidal neurons was also increased. Blockade of NMDA receptors (NMDARs) 10 min after the onset of continuous electrographic seizure activity prevented the increase in the surface expression of GluA1 subunits. NMDAR antagonist MK-801 in conjunction with diazepam also terminated seizures which were refractory to MK-801 or diazepam alone.

Future studies using mice lacking the GluA1 subunit expression will provide further insights into the role of GluA1 subunit-containing AMPAR plasticity in sustaining seizures of SE.

Keywords: Status epilepticus, AMPA receptor, GluA1 subunit

Status epilepticus is recently redefined as a condition resulting either from the failure of the mechanisms responsible for seizure termination or from the initiation of mechanisms, which lead to abnormally, prolonged seizures (after time point t1). It is a condition, which can have long-term consequences (after time point t2), including neuronal death, neuronal injury, and alteration of neuronal networks, depending on the type and duration of seizures1. Repetitive seizures of status epilepticus reduce GABA-A receptor-mediated inhibition in key structures is well documented2. This reduced inhibition can compromise mechanisms of seizure termination. However, the mechanisms that initiate abnormally prolonged seizures are poorly understood.

We propose that potentiated AMPA receptor (AMPAR) -mediated transmission can sustain SE. Hippocampal pyramidal neurons are highly active during seizures and SE3;4. NMDA receptors are activated during status epilepticus. The activation of these receptors can potentiate AMPARs through GluA1 insertion5. Neuronal injury and death during SE are believed to result from excessive excitatory transmission6. The potentiation of recurrent excitatory connections can lead to neuronal synchrony and seizure propagation7. Several studies have shown that AMPAR antagonists effectively terminate SE8–10. However, the precise mechanism of enhanced AMPAR transmission and its role in sustaining SE are unclear.

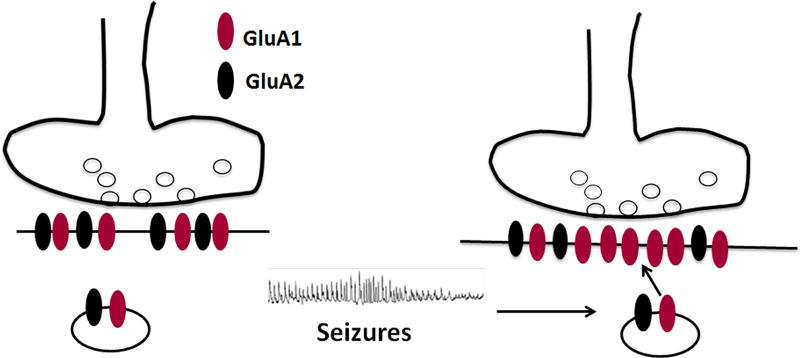

A large body of experimental and modeling data suggests that focal seizures are initiated by the mutual excitation of hippocampal (or cortical) pyramidal neurons. The enhancement of excitatory transmission can initiate and propagate seizures11–13. We propose that seizures enhance AMPAR-mediated transmission in activated neurons by causing GluA1 insertion into glutamatergic synapses (Fig. 1). Each seizure modifies the transmission of a few neurons; more neurons are modified by repeated seizures engaging a progressively larger set of neurons (Fig. 2). These neurons form a self-perpetuating and propagating network, ultimately resulting in SE.

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram illustrating the hypothesis that seizures cause insertion of GluA1 subunit-containing AMPARs at glutamatergic synapses of CA1 pyramidal neurons. The increase in the fraction of GluA1 subunits incorporated into the receptors leads to the expression of calcium-permeable receptors with inwardly rectifying currents as well as augmentation of synaptic AMPAR-mediated current amplitude.

Figure 2.

A schematic diagram showing the proposed hypothesis that seizures activate a few neurons; repeated seizures cause activation of more and more neurons that could have synchronized activity, which can spread and sustain prolonged seizures of SE.

AMPARs are homomeric or heteromeric oligomers comprising multiple GluA1-GluA4 subunits14 (genes Gria1–4). In the hippocampus, most AMPARs are composed of GluA1 and GluA4 subunits, with a minor contribution of GluA2/3 subunits15;16. The GluA1 subunit is well expressed in CA1 and CA3 pyramidal neurons and dentate granule cells of the hippocampus, septum, entorhinal cortex, olfactory bulb, olfactory cortex, sensory and motor cortices, striatum, and cerebellum. Expression in the thalamus is mostly limited to the midline nuclei. The plasticity of the GluA1 subunit also plays a role in other forms of activity-dependent plasticity, such as long-term potentiation (LTP), homeostatic plasticity, open eye potentiation during the formation of ocular dominance columns, and hypoxia-induced seizures. The GluA1 subunit (similarly to other AMPAR subunits) is an integral membrane protein with an extracellular domain, three membrane-spanning domains, a hairpin intra-membrane pore lining domain and three intracellular domains, including a carboxy tail (C-tail) that plays an important role in AMPAR trafficking. The phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of serine 831 and serine 841 in the C-tail can mediate rapid GluA1 plasticity. The phosphorylation of these sites can increase the probability of channel opening and single channel conductance. AMPAR trafficking is modulated by the phosphorylation of these sites17–19. The effects of phosphorylation/dephosphorylation on receptor trafficking and LTP are complex as revealed by studies on phospho-deficient and phospho-mimetic knockin mice. It is well known that NMDA receptor activation plays a role in LTP/LTD GluA1 plasticity and phosphorylation.

We tested whether AMPAR-mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) are enhanced by the delivery of the GluA1 subunit to synapses in CA1 pyramidal neurons during benzodiazepine-resistant SE20. Hippocampal slices were prepared from rats after 40 minutes of pilocarpine-induced self-sustaining SE, in which the EEG demonstrated continuous seizure activity and allowed 20 minutes of recovery. The AMPAR-mediated action potential-independent miniature EPSCs (mEPSCs) were subsequently recorded according to methods described previously21. The mEPSCs recorded from the CA1 pyramidal neurons of SE animals were larger than those recorded from controls20. However, the frequency, rise time, and decay of the mEPSCs did not change. We also recorded spontaneous EPSCs from CA1 pyramidal neurons; their amplitudes increased.

Increased neuronal activity incorporates GluA1 subunit-containing AMPARs into synapses, which likely increases the proportion of GluA1 homomers and reduces GluA1/GluA2 heterodimers at the synapse (Fig. 1). Because GluA2-lacking AMPARs produce rectifying channels, we expected increased rectification of AMPAR currents in SE animals22. EPSCs electrically evoked in the CA1 pyramidal neurons of SE animals demonstrated rectification at depolarized potentials compared to non-rectifying EPSCs evoked from control animals. A rectification index (RI) was defined as the ratio of the current amplitude recorded at +40 mv to −40 mV. The RI in SE animals was 0.35 ± 0.079 (n= 8 cells/7 animals) less than the RI in control animals (0.96 ± 0.065; n= 8 cells/5 animals, p<0.0001)20.

We then tested whether seizure activity induced the trafficking of GluA1 subunit-containing AMPARs to the surface of the membrane. Using a biotinylation assay, we found that the surface expression of the GluA1 subunit increased in the CA1 region during prolonged SE20. The surface expression of the AMPAR GluA1 subunit was higher in the CA1 region microdissected from animals in SE for 1 hour when compared to the naïve animals. An alternative way of measuring surface and intracellular fractions of proteins is to cross-link all of the surface proteins, eliminate them from detection, and measure the intracellular fraction using BS3 assay. The BS3 assay revealed reduced expression of the GluA1 subunit in the intracellular CA1 region fraction in SE animals. The intracellular expression of the GluA1 subunit decreased in the CA1 region of 60 min SE hippocampi compared to the controls; the total amount of GluA1 subunit proteins were similar in the SE and control animals20. Because the total GluA1 subunit expression was unaltered during SE, this assay confirmed that the surface expression of the GluA1 subunit increased in the CA1 region of SE animals. This finding was further confirmed in mice (167 ± 25% of that in controls, n=4, p<0.05). In summary, during self-sustaining SE, AMPAR-mediated ESPCs recorded from CA1 pyramidal neurons were potentiated, and the surface expression of the GluA1 subunit increased.

NMDAR activation regulates the surface membrane insertion of GluA1 subunit-containing AMPARs during LTP23. NMDARs are activated during SE24 and may play a role in the increased surface expression of GluA1 subunit. To block NMDARs, animals were treated with MK-801 (2 mg/kg), a non-competitive NMDAR antagonist that acts via the phencyclidine (PCP) site, 10 min after the first stage 5 behavioral seizure occurred. The surface expression of the GluA1 subunit determined 1 hour after the onset of SE using a biotinylation assay in MK-801-treated SE animals was similar to that in controls (120 ± 24% of that in controls, N= 5, p > 0.05). A BS3 assay also revealed that MK-801 treatment prevented an increase in surface expression of GluA1 subunits during SE. Treatment of animals with MK-801 alone without SE for 50 min did not alter the intracellular expression of GluA1 subunits.

The blockade of NMDARs prevented GluA1 subunit upregulation. We determined whether MK-801 combined with benzodiazepine treatment after the start of continuous seizure activity would terminate SE. Animals were treated with MK-801 (2 mg/kg) or diazepam (10 mg/kg, ip) either alone or in combination 10 min after the seizure activity became continuous. The EEG power in the 1–60 Hz frequency range remained high for 120 min in the animals treated with MK-801 alone or diazepam alone20. However, the combination of diazepam and MK-801 rapidly decreased the EEG power20. Visual analysis of the EEG traces was performed to determine the point of SE termination, which was defined by the slowing of spike wave discharges to below 2 Hz and the development of arrhythmic patterns without the recurrence of seizures for 60 min. SE continued unabated in the MK-801-treated animals (377 ± 89 min, N= 5) and in the diazepam-treated animals (367 ± 113 min, N= 5). However, a combination of MK-801 and diazepam rapidly terminated the SE (28 ± 16 min, N= 6, p < 0.05 ANOVA with post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparison test).

Treatment of animals with diazepam also blocked the increase in GluA1 subunit surface expression20. This further supports the hypothesis that seizure activity causes insertion of GluA1 subunit-containing AMPA receptors on the surface membrane of CA1 neurons.

Thus, AMPAR-mediated synaptic neurotransmission of CA1 neurons was potentiated during SE. Enhanced glutamatergic transmission on CA1 pyramidal neurons can facilitate seizure spread to its targets: subiculum, entorhinal cortex, septum, olfactory tubercle, mid-line thalamic nuclei and mammillary body. Studies to image seizure spread from the hippocampus to the rest of the brain can help test whether these targets are activated during SE. Other studies determining whether the mice lacking GluA1 subunit expression have shorter duration SE, with limited spread will provide additional insights into the role of GluA1 subunit-containing AMPARs in spreading and sustaining seizures.

Key Bullet points.

AMPA receptor-mediated synaptic neurotransmission of CA1 pyramidal neurons was enhanced in animals in SE.

The surface expression of GluA1 subunit-containing AMPA receptors was also increased in the CA1 neurons of animals in SE.

Blockade of NMDA receptors prevented SE-associated increase in GluA1 subunit-containing AMPA receptors.

A combination of MK-801 and diazepam terminated benzodiazepine refractory SE.

We hypothesize that enhanced AMPA receptor transmission plays an important role in sustaining SE.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grants RO1 NS 040337 and RO1 NS 044370 (JK).

Footnotes

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Neither of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Trinka E, Cock H, Hesdorffer D, et al. A definition and classification of status epilepticus: Report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification of Status Epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2015;56:1515–23. doi: 10.1111/epi.13121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joshi S, Kapur J. GABAA receptor plasticity during status epilepticus. In: Noebels JL, et al., editors. Jasper's Basic Mechanisms of the Epilepsies. Bethesda MD: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 545–51. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lothman E. The biochemical basis and pathophysiology of status epilepticus. Neurology. 1990;40:13–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen JW, Naylor DE, Wasterlain CG. Advances in the pathophysiology of status epilepticus. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 2007;186:7–15. 7–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. AMPA receptor trafficking at excitatory synapses. Neuron. 2003;40:361–79. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00640-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujikawa DG. Prolonged seizures and cellular injury: understanding the connection. Epilepsy Behav. 2005;7(Suppl 3):S3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jefferys JG, Traub RD. Electrophysiological substrates for focal epilepsies. Prog Brain Res. 1998;116:351–8. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)60447-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jefferys JG, Traub RD. Electrophysiological substrates for focal epilepsies. Prog Brain Res. 1998;116:351–8. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)60447-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogawski MA, Donevan SD. AMPA receptors in epilepsy and as targets for antiepileptic drugs. Adv Neurol. 1999;79:947–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogawski MA. Revisiting AMPA receptors as an antiepileptic drug target. Epilepsy Curr. 2011;11:56–63. doi: 10.5698/1535-7511-11.2.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin BS, Kapur J. A combination of ketamine and diazepam synergistically controls refractory status epilepticus induced by cholinergic stimulation. Epilepsia. 2008;49:248–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01384.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prasad A, Williamson JM, Bertram EH. Phenobarbital and MK-801, but not phenytoin, improve the long-term outcome of status epilepticus. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:175–81. doi: 10.1002/ana.10085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wasterlain CG, Baldwin R, Naylor DE, Thompson KW, Suchomelova L, Niquet J. Rational polytherapy in the treatment of acute seizures and status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2011;52(Suppl 8):70–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borges K, Dingledine R. AMPA receptors: molecular and functional diversity. Prog Brain Res. 1998;116:153–70. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)60436-7. 153-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wenthold RJ, Petralia RS, Blahos J, II, Niedzielski AS. Evidence for multiple AMPA receptor complexes in hippocampal CA1/CA2 neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1982–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-06-01982.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu W, Shi Y, Jackson AC, et al. Subunit composition of synaptic AMPA receptors revealed by a single-cell genetic approach. Neuron. 2009;62:254–68. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu W, Roche KW. Posttranslational regulation of AMPA receptor trafficking and function. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2012;22:470–9. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu H, Real E, Takamiya K, et al. Emotion enhances learning via norepinephrine regulation of AMPA-receptor trafficking. Cell. 2007;131:160–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee HK, Barbarosie M, Kameyama K, Bear MF, Huganir RL. Regulation of distinct AMPA receptor phosphorylation sites during bidirectional synaptic plasticity. Nature. 2000;405:955–9. doi: 10.1038/35016089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joshi S, Rajasekaran K, Sun H, Williamson J, Kapur J. Enhanced AMPA receptor-mediated neurotransmission on CA1 pyramidal neurons during status epilepticus. Neurobiol Dis. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2017.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun J, Kapur J. M-type potassium channels modulate Schaffer collateral-CA1 glutamatergic synaptic transmission. J Physiol. 2012;590:3953–64. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.235820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rajasekaran K, Todorovic M, Kapur J. Calcium-permeable AMPA receptors are expressed in a rodent model of status epilepticus. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:91–102. doi: 10.1002/ana.23570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Derkach VA, Oh MC, Guire ES, Soderling TR. Regulatory mechanisms of AMPA receptors in synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:101–13. doi: 10.1038/nrn2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naylor DE, Liu H, Niquet J, Wasterlain CG. Rapid surface accumulation of NMDA receptors increases glutamatergic excitation during status epilepticus. Neurobiology of Disease. 2013;54:225–38. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]