Abstract

As a potent chemotherapy drug, cisplatin is also notorious for its side-effects including nephrotoxicity in kidneys, presenting a pressing need to identify renoprotective agents. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity involves epigenetic regulations, including changes in histone acetylation. Bromodomain and extraterminal (BET) proteins are “readers” of the epigenetic code of histone acetylation. Here, we investigated the potential renoprotective effects of JQ1, a small molecule inhibitor of BET proteins. We show that JQ1 significantly ameliorated cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in mice as indicated by the measurements of kidney function, histopathology, and renal tubular apoptosis. JQ1 also partially prevented the body weight loss during cisplatin treatment in mice. Consistently, JQ1 inhibited cisplatin-induced apoptosis in renal proximal tubular cells. Mechanistically, JQ1 suppressed cisplatin-induced phosphorylation or activation of p53 and Chk2, key events in DNA damage response. JQ1 also attenuated cisplatin-induced MAP kinase (p38, ERK1/2, and JNK) activation. In addition, JQ1 enhanced the expression of antioxidant genes including nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 and heme oxygenase-1, while diminishing the expression of the nitrosative protein inducible nitric oxide synthase. JQ1 did not suppress cisplatin-induced apoptosis in A549 nonsmall cell lung cancer cells and AGS gastric cancer cells. These results suggest that JQ1 may protect against cisplatin nephrotoxicity by suppressing DNA damage response, p53, MAP kinases, and oxidative/nitrosative stress pathways.

Keywords: cisplatin nephrotoxicity, DNA damage response, JQ1, MAPK, p53, ROS

INTRODUCTION

Cisplatin (Cis-diamminedichloroplatinum II) is a potent antitumor agent being used in the treatment of a wide range of cancers. Nephrotoxicity is a well-recognized side effect of cisplatin-based chemotherapy in cancer patients, which leads to acute kidney injury (AKI) and subsequent chronic renal problems. After a single dose of cisplatin, ~25–40% patients exhibit a progressive decline in renal function, which is characterized by a decline in glomerular filtration rate, increased serum creatinine, and reduced serum magnesium and potassium levels (22, 25, 30). Currently, no effective approaches are available to prevent cisplatin nephrotoxicity during chemotherapy.

Although the pathogenesis of cisplatin nephrotoxicity is not entirely clear, it is known that cisplatin activates multiple signaling pathways in renal tubular cells, resulting in inflammation, oxidative stress, and tubular cell injury and death (22, 25, 30, 37). We and others have especially delineated a rapid DNA damage response in cisplatin nephrotoxicity that consists of sequential activation of ATR and Chk2, resulting in p53 activation for renal tubular cell death (16, 26, 27, 34, 38). In addition, there are p53-independent pathways that contribute to renal tubular injury in cisplatin nephrotoxicity (13), and one such pathway includes mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (2, 9, 24, 28).

The bromodomain and extraterminal (BET) proteins have a unique structure to specifically recognize and bind acetylated lysine residues in histones to activate gene transcription and, as a result, these proteins are “readers” of the epigenetic code of histone acetylation (21, 22). In mammalian cells, there are four BET family members, including BRD2, BRD3, BRD4, and BRDT. BET inhibitors are acetylated histone mimics, which bind the BRD domains in BET proteins to displace them from binding to acetylated lysine residues on chromatin, resulting in the inhibition of gene transcription (6). JQ1 is one of the most characterized BET inhibitors with high specificity against BET proteins (7). In kidneys, Zhou et al. (39) showed that JQ1 can delay cyst growth and preserve renal function in a murine model of polycystic kidney disease. More recent work by Suarez-Alvarez et al. (33) further showed that JQ1 may block the transcription of key proinflammatory genes and suppress renal inflammation in murine models of unilateral ureteral obstruction, antiglomerular basal membrane nephritis, and angiotensin II infusion. It remains unclear if BET inhibitors (e.g., JQ1) may have beneficial effects on AKI. This study was designed to determine the effect of JQ1 on cisplatin-induced AKI or nephrotoxicity and investigate the underlying mechanisms. Using both cell culture and mouse models, we have demonstrated a protective role of JQ1 in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. JQ1 may protect kidney cells and tissues by suppressing DNA damage response, MAPK activation, and oxidative/nitrosative stress during cisplatin treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibodies.

JQ1 was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Other chemicals including cisplatin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Antibodies were from the following sources: anti-BRD4 antibody from Abcam (Cambridge, MA); anti-cleaved caspase-3, cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), p53, phospho p53 (Ser-15), phospo-Chk2, phospo-H2AX, extracellular-receptor kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), p38, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinases (JNK), phospho-JNK, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) antibodies from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA); anti-phospho-ERK1/2, phospho-p38 antibodies from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Grand Island, NY); and anti-inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and anti-β-actin antibodies from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). All secondary antibodies were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA).

Animals and treatment.

Eight-week-old, male C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and were supplied with water and food ad libitum under 12:12-h light-dark cycle and constant temperature (22 ± 1°C) and humidity (50 ± 5%). All experiments were carried out following the protocol approved by the Institute Animal Care and Usage Committee of Charlie Norwood Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Male mice were randomly divided into three experimental groups with six animals per group. For cisplatin treatment, 30 mg/kg cisplatin were freshly prepared in saline and injected intraperitoneally into mice as previously (24, 34, 38). To test the effect of JQ1, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 20 mg/kg JQ1 24 h before cisplatin administration and then daily after cisplatin treatment. Three days after cisplatin treatment, the mice were weighed and then killed to collect blood and kidney samples.

Renal function measurement.

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine levels were determined to indicate renal function by using commercial kits as before (24, 34, 38). BUN was measured with a kit from Biotron Diagnostics (Hemet, CA), and absorbance at 520 nm was recorded. Serum creatinine was measured using a kit from Stanbio Laboratory (Boerne, TX), and the absorbance at 510 nm was monitored at 20 and 80 s of reaction. BUN and creatinine levels (mg/dl) were then calculated based on standard curves.

Renal histology.

For histology, paraffin-embedded kidney sections were cut into 5 μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Evaluation of histopathological changes in this study included loss of brush border, tubular dilation, cast formation, and cell lysis. Tissue damage was scored based on the percentage of damaged tubules as described previously (24, 34, 38): 0, no damage; 1, less than 25% damage; 2, 25−50% damage; 3, 50–75% damage; and 4, more than 75% damage.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP-mediated nick-end labeling staining of kidney tissues.

The terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP-mediated nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay for detection of apoptosis was performed by using the in situ Cell Death Detection kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) as before (24, 34, 38). Briefly, kidney sections were deparaffinized by incubation with 0.1 M sodium citrate, pH 6.0 at 65 °C for 1 h. TUNEL reaction mixture was then added, and these slices were incubated in a humidified chamber buffer for 1 h at 37 °C. Positive staining was detected by Axioplan2 fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Germany). The number of positive cells was counted in a random, blinded fashion in 10–20 nonoverlapping fields for each section.

Cell culture and treatments.

The renal proximal tubular cell (RPTC) line was originally obtained from Dr. Ulrich Hopfer (Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH) and maintained in Ham's F-12/DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (5 g/ml transferrin, 5 μg/ml insulin, 1 ng/ml EGF, 4 μg/ml dexamethasone, and 1% antibiotics). RPTCs were plated at a density of 0.8 × 106 cells/dish in 35-mm dishes to reach confluence by the next day for treatment as previously (16, 26, 27). JQ1 was then added to the cells at a final concentration of 100 nM for 2 h. The cells were then incubated with or without 20 μM cisplatin in the presence of JQ1 for indicated time. After the treatment, the cells were analyzed by morphology for apoptosis or harvested with lysis buffer for various biochemical analyses.

Morphological analysis of apoptosis in cell culture.

Apoptotic cells were identified by their morphology as described previously (16, 26, 27). Briefly, cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 (10 μg/ml; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 2–3 min and then examined by phase contrast and fluorescence microscopy. Apoptosis is characterized by cell morphological changes, including shrunken configuration, apoptotic bodies, and condensed and fragmented nuclei. Four fields with ∼200 cells/field were examined in each dish to estimate the percentage of apoptosis. Each experiment was independently repeated three times.

Immunoblot analysis.

We performed immunoblot analysis as previously (26, 27). Briefly, the protein concentrations were determined by using the BCA reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Equal amounts of proteins were resolved on 8–15% SDS polyacrylamide gels, followed by transferring onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were then incubated sequentially with 5% fat-free milk blocking buffer for 1 h, the primary antibodies at 4°C overnight, washing buffer, and conjugated secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. The protein bands were revealed by using Clarity Western ECL Blotting Substrates (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Densitometry analysis of protein band signal was performed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Statistics.

Data are expressed as the means ± SE. Statistical analysis was conducted using the GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni post hoc test to compare more than two groups and the Student's t-test to compare two groups. Results were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

JQ1 ameliorates cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity.

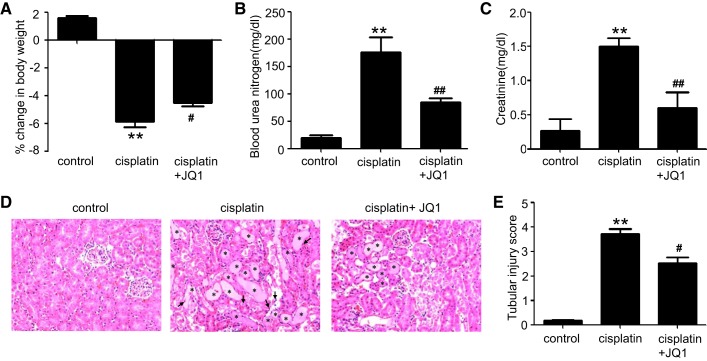

To assess the effects of JQ1 on cisplatin-induced AKI, male C57BL/6 mice were injected with 20 mg/kg cisplatin in the presence or absence of JQ1. Cisplatin induced significant toxicity in mice as indicated by the loss of body weight at 72 h (Fig. 1A). These mice also showed a marked deterioration of renal function as indicated by significant increases in BUN (Fig. 1B) and serum creatinine (Fig. 1C). Notably, JQ1 suppressed the body weight loss as well as BUN and serum creatinine increases during cisplatin treatment. Furthermore, histological examinations showed obvious tubular damage, including hyaline cast formation and renal tubule lysis, in kidney tissues following cisplatin administration, which was also partially but significantly inhibited by JQ1 (Fig. 1, D and E).

Fig. 1.

Effect of JQ1 on cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in C57BL/6 mice. C57BL/6 mice were given 1 intraperitoneal injection of 30 mg/kg cisplatin or saline as control. To test the effect of JQ1, 20 mg/kg JQ1 were injected 24 h before cisplatin and then injected daily for 3 days. Blood samples were collected for blood urea nitrogen and creatinine measurement. A: %change in body weight. B: blood urea nitrogen. C: serum creatinine. D: representative renal histology shown by hematoxylin and eosin staining (×200). E: scoring of acute tubular injury. Values are the means ± SE (n = 6). **P < 0.01 vs. control group; #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 vs. cisplatin group.

JQ1 attenuates cisplatin-induced renal apoptosis in mice.

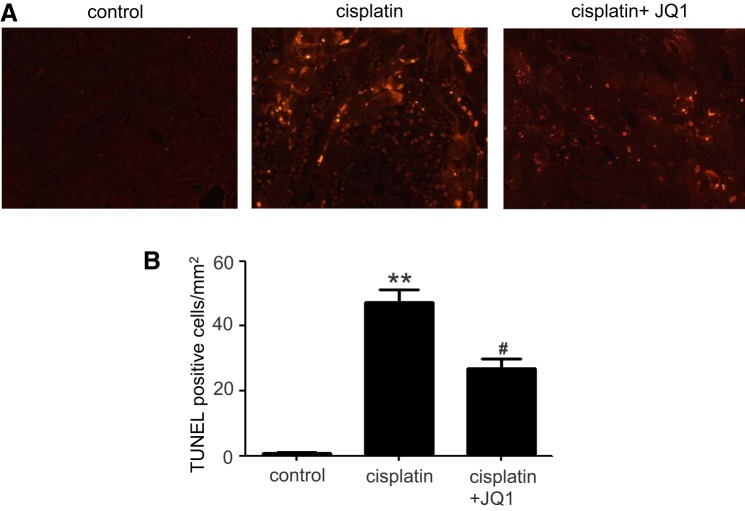

Apoptosis of renal tubular epithelial cells plays a major role in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity (22, 23, 25). We examined whether JQ1 could effectively prevent cisplatin-induced apoptosis by using the TUNEL assay. As shown in Fig. 2A, cisplatin treatment significantly increased apoptotic cells in kidney tissues as compared with control tissues, and JQ1 treatment markedly decreased the number of TUNEL-positive cells. Quantification by counting TUNEL-positive cells further verified the observation (Fig. 2B), further indicating the protective role of JQ1 in cisplatin nephrotoxicity.

Fig. 2.

Effect of JQ1 on cisplatin-induced apoptosis in renal tubules. C57BL/6 mice were injected intraperitoneally with JQ1 at 20 mg/kg 24 h before cisplatin (30 mg/kg) administration and then daily after cisplatin treatment for 3 days. A: representative images of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP-mediated nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining. B: quantification of TUNEL-positive cells in kidney tissues. Values are the means ± SE (n = 6). **P < 0.01 vs. control group; #P < 0.05 vs. cisplatin group.

JQ1 decreases cisplatin-induced apoptosis in RPTCs.

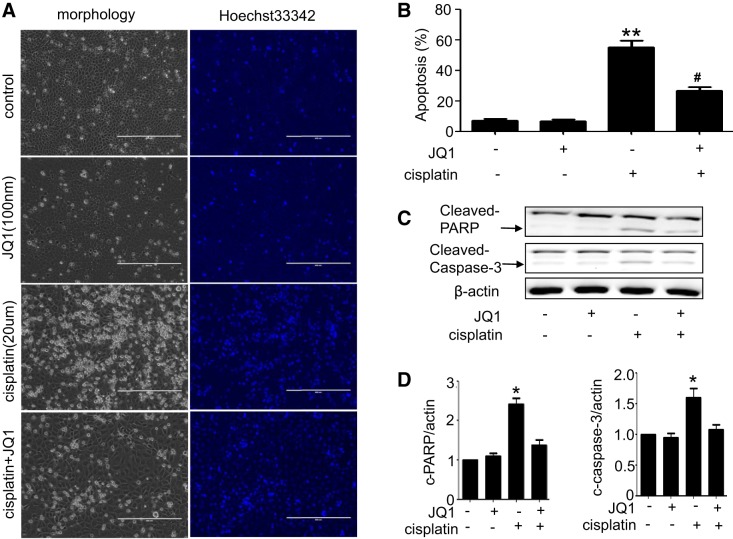

To determine the effect of JQ1 on cisplatin-induced apoptosis in vitro, we pretreated cultured RPTCs with 100 nM JQ1 for 2 h and then subjected the cells to 20 μM cisplatin treatment for 16 h in the presence of 100 nM JQ1. As shown in Fig. 3A, cells in control and JQ1-only group showed normal healthy morphology with minimal apoptosis. Cisplatin treatment for 16-h induced massive apoptosis, showing cellular and nuclear condensation and fragmentation. Cisplatin-induced apoptosis was inhibited by JQ1. Quantification by cell counting indicated that cisplatin induced around 55% apoptosis, which was suppressed to 25% by JQ1 (Fig. 3B). Consistently, cisplatin-induced caspase-3 and PARP cleavage was also prevented by JQ1 (Fig. 3, C and D).

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of cisplatin-induced apoptosis by JQ1 in renal proximal tubular cells (RPTCs). RPTCs were pretreated with 0.1 μM JQ1 for 2 h and then coincubated with or without 20 μM cisplatin for 16 h. A: morphology. Cells were stained with 10 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 to record nuclear and cellular morphology by fluorescence and phase-contrast microscopy. B: %apoptosis evaluated by counting the cells with typical apoptotic morphology. Values are the means ± SE (n = 3). **P < 0.01 vs. control group; #P < 0.05 vs. cisplatin group. C: immunoblot analyses of cleaved caspase-3 and cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1). Immunoblots were representative of 3 independent experiments. D: densitometry analysis. Values are the means ± SE (n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. control group.

JQ1 suppresses cisplatin-induced p53 phosphorylation and activation.

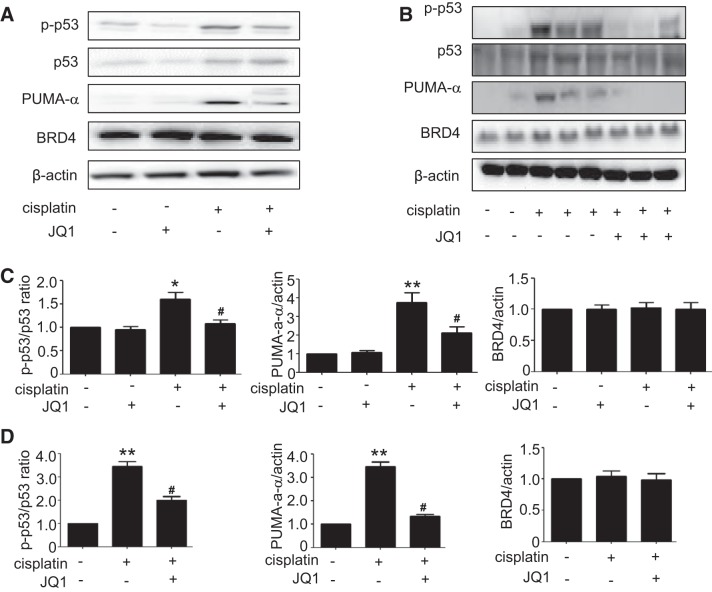

A major signaling pathway leading to cisplatin-induced renal cell apoptosis and nephrotoxicity involves p53 induction and activation (12). We hypothesized that the cytoprotective effects of JQ1 might be related to the suppression of p53 activation during cisplatin treatment. To test this possibility, we first analyzed total and phosphorylated (Ser15) p53 by immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 4A, cisplatin treatment increased p53 phosphorylation at serine-15, which was decreased obviously by JQ1. Consistently, JQ1 suppressed the induction of PUMA-α, a downstream target gene of p53 in cisplatin nephrotoxicity (15). In vivo, JQ1 also suppressed p53 phosphorylation/activation and PUMA-α induction (Fig. 4B). Quantitative analysis by densitometry further verified the inhibitory effect of JQ1 on p53 activation during cisplatin treatment of RPTC cells and mice (Fig. 4, A and B). JQ1 did not alter the expression of BRD proteins (e.g., BRD4 in Fig. 4), which is not surprising because JQ1 inhibits BRD proteins by direct binding to prevent their association with lysine-acetylated chromatin and consequent gene transcription (7).

Fig. 4.

Suppression of cisplatin-induced p53 phosphorylation and activation by JQ1 in vivo and in vitro. A and C: immunoblot analyses of total p53, p-p53, PUMA-a, and BRD4 in renal proximal tubular cells (RPTCs). RPTCs were pretreated with 0.1 μM JQ1 for 2 h and then coincubated with or without 20 μM cisplatin for 16 h to collect cell lysate for immunoblot analyses. A: representative immunoblots of 3 independent experiments. C: densitometric analysis. Values are the means ± SE (n = 3). B and D: immunoblot analyses of total p53, p-p53, PUMA-a, and BRD4 in mice. C57BL/6 mice were given 1 intraperitoneal injection of 30 mg/kg cisplatin or saline as control. To test the effect of JQ1, 20 mg/kg JQ1 were injected 24 h before cisplatin and then injected daily for 3 days. Kidney cortical tissues were extracted for analysis. B: representative immunoblots. D: densitometric analysis. Values are the means ± SE (n = 6). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 vs. control group; #P < 0.05 vs. cisplatin group.

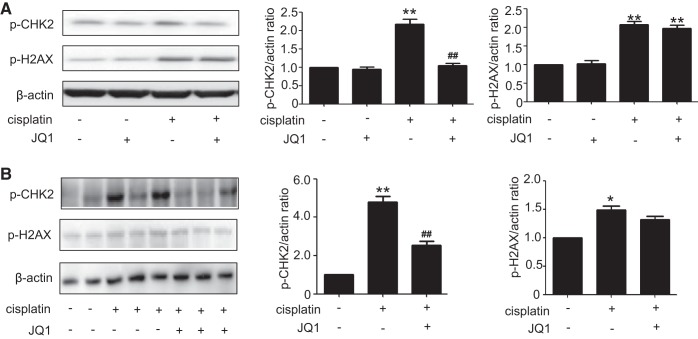

JQ1 blocks cisplatin-induced phosphorylation of Chk2 but not H2AX.

Our previous study demonstrated a rapid DNA damage response triggered by cisplatin that contributes to p53 activation and renal cell apoptosis (26). In this response, ATR [ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and Rad3 related] accumulates at discrete nuclear foci or DNA damage sites resulting in the phosphorylation/activation of Chk2, which may further phosphorylate p53. To determine whether JQ1 suppresses p53 activation by interrupting the DNA damage response, we analyzed the phosphorylation of Chk2. As shown in Fig. 5, cisplatin induced the phosphorylation of Chk2 and H2AX (a biochemical hallmark of DNA damage) in RPTC cells. JQ1 ameliorated Chk2 phosphorylation during cisplatin treatment, while it did not block H2AX phosphorylation. These data indicate that JQ1 may suppress Chk2-mediated DNA damage response during cisplatin nephrotoxicity without diminishing DNA damage.

Fig. 5.

Suppression by JQ1 of cisplatin-induced activation of Chk2 but not H2AX. A: immunoblot analysis of p-CHK2 and p-H2AX in renal proximal tubular cells (RPTCs). RPTCs were pretreated with 0.1 μM JQ1 for 2 h and then coincubated with or without 20 μM cisplatin for 16 h to collect cell lysate for immunoblot analyses. Left: representative immunoblots. Right: densitometric analysis. Immunoblots were representative of 3 independent experiments. Values are the means ± SE (n = 3). B: immunoblot analysis of p-CHK2 and p-H2AX in kidney tissues from mice. C57BL/6 mice were given 1 intraperitoneal injection of 30 mg/kg cisplatin or saline as control. To test the effect of JQ1, 20 mg/kg JQ1 were injected 24 h before cisplatin and then injected daily for 3 days. Kidney cortical tissues were extracted for immunoblot analysis. Left: representative immunoblots. Right: densitometric analysis. Values are the means ± SE (n = 6). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 vs. control group; ##P < 0.01 vs. cisplatin group.

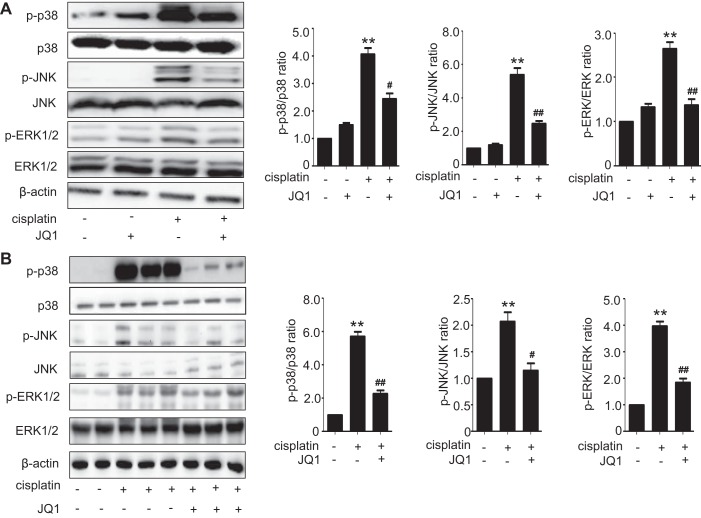

JQ1 inhibits cisplatin-induced MAPK signaling pathways.

Given that cisplatin-induced renal tubular cell death has also been associated with the activation of MAPK signaling pathways, we subsequently analyzed the possible effects of JQ1 on the phosphorylation levels of ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 kinase during cisplatin treatment. As shown in Fig. 6A, cisplatin increased the phosphorylation of p38, ERK1/2, and JNK in RPTC cells, which was attenuated by JQ1. Consistently, cisplatin induced the phosphorylation of p38, ERK1/2, and JNK in mouse kidney tissues, which was also suppressed by JQ1. There were no significant differences in the expression of total ERK, JNK, or p38 proteins between these groups.

Fig. 6.

Effect of JQ1 on cisplatin-induced MAPKs activation in vivo and in vitro. A: immunoblot analyses of p-p38, p38, p-JNK, JNK, p-ERK, and ERK in renal proximal tubular cells (RPTCs). RPTCs were pretreated with 0.1 μM JQ1 for 2 h and then coincubated with or without 20 μM cisplatin for 16 h to collect cell lysate for immunoblot analyses. Left: representative immunoblots. Right: densitometric analysis. Immunoblots were representative of 3 independent experiments. Values are the means ± SE (n = 3). B: immunoblot analyses of p-p38, p38, p-JNK, JNK, p-ERK, and ERK in renal tissues from mice. C57BL/6 mice were given 1 intraperitoneal injection of 30 mg/kg cisplatin or saline as control. To test the effect of JQ1, 20 mg/kg JQ1 were injected 24 h before cisplatin and then injected daily for 3 days. Kidney cortical tissues were extracted for immunoblot analysis. Left: representative immunoblots. Right: densitometric analysis. Values are the means ± SE (n = 6). **P < 0.01 vs. control group; #P < 0.05 and ## P < 0.01 vs. cisplatin group.

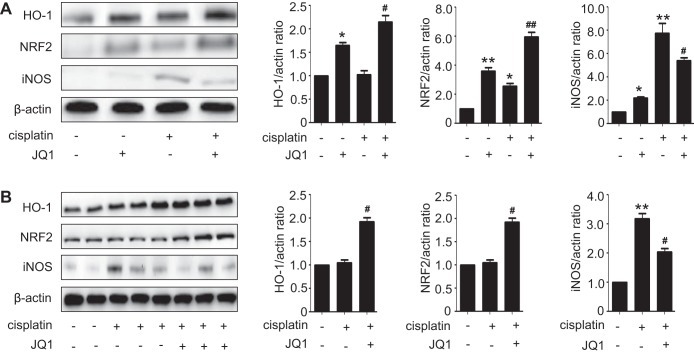

JQ1 induces the expression of antioxidant proteins and attenuates cisplatin-induced nitrosative stress.

Oxidative stress is known to contribute to cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. To investigate the effect of JQ1 on renal oxidative stress in cisplatin-induced kidney injury, we assessed the expression of Nrf2, a master regulator of antioxidant responses, and its target gene HO-1. In RPTC cells, treatment with cisplatin or JQ1 alone induced Nrf2 and HO-1 expression, while JQ1 plus cisplatin induced further expression of these antioxidant proteins (Fig. 7A). In mouse kidneys, cisplatin or JQ1 alone did not significantly induce Nrf2 and HO-1, whereas JQ1 plus cisplatin did (Fig. 7B). iNOS, a key enzyme in nitrosative stress, was implicated in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. We detected a significant increase in iNOS expression in RPTC cells and mouse kidneys during cisplatin treatment, which was partially but significantly suppressed by JQ1 (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

JQ1 enhances nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) induction during cisplatin treatment while suppressing iNOS. A: immunoblot analysis of Nrf2, HO-1, and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in renal proximal tubular cells (RPTCs). RPTCs were pretreated with 0.1 μM JQ1 for 2 h and then coincubated with or without 20 μM cisplatin for 16 h to collect cell lysate for immunoblot analyses. Left: representative immunoblots. Right: densitometric analysis. Immunoblots were representative of 3 independent experiments. Values are the means ± SE (n = 3). B: immunoblot analyses of Nrf2, HO-1, and iNOS in renal tissues from mice. C57BL/6 mice were given 1 intraperitoneal injection of 30 mg/kg cisplatin or saline as control. To test the effect of JQ1, 20 mg/kg JQ1 were injected 24 h before cisplatin and then injected daily for 3 days. Kidney cortical tissues were extracted for immunoblot analysis. Left: representative immunoblots. Right: densitometric analysis. Values are the means ± SE (n = 6). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 vs. control group; #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 vs. cisplatin group.

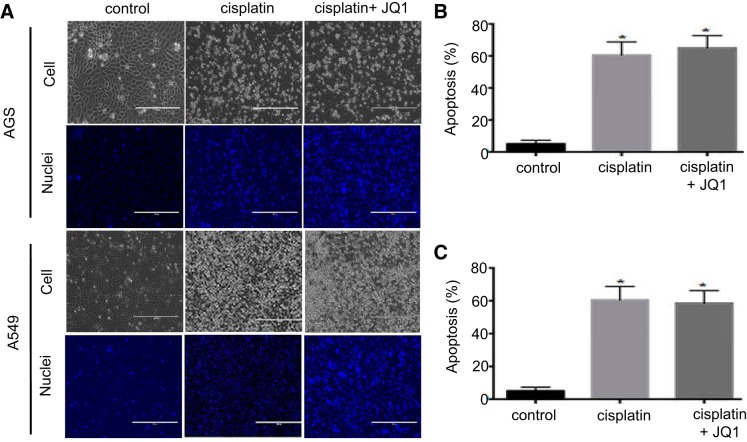

JQ1 does not suppress cisplatin-induced apoptosis in cancer cell lines.

To determine whether the JQ1 might affect the antitumor efficacy of cisplatin, we examined the effects of JQ1 on cisplatin-induced apoptosis in A549 nonsmall cell lung cancer cell line and AGS gastric cancer cell line. Phase-contrast microscopy in combination with Hoechst 33342 staining showed JQ1 slightly increased apoptosis during cisplatin treatment of AGS cells (Fig. 8, A and B). In A549 cells, JQ1 did not affect cisplatin-induced apoptosis (Fig. 8, A and C). These data suggest that JQ1 may not suppress the anticancer effect of cisplatin in tumors.

Fig. 8.

JQ1 does not suppress cisplatin-induced apoptosis in cancer cells. A: A549 and AGS cancer cells were pretreated with JQ1 (1.0 μmol/l) for 2 h and then coincubated with 10 μM cisplatin for 24 h; cell morphology is shown. Cells were stained with 10 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 to record nuclear and cellular morphology by fluorescence and phase-contrast microscopy. B: apoptotic AGS cells were counted by morphology to determine %apoptosis. C: apoptotic A549 cells were counted by morphology to determine %apoptosis. Values are the means ± SE (n = 3). *P < 0.01 vs. control group.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have demonstrated that the BET/BRD protein inhibitor JQ1 can effectively protect against cisplatin-induced kidney injury or nephrotoxicity using both in vivo mouse and in vitro RPTC cell models. Mechanistically, we show that JQ1 may attenuate cisplatin-induced DNA damage response, MAP kinase (MAPK) activation, and oxidative/nitrative stress, resulting in the amelioration of renal tubular cell apoptosis.

Recent studies have begun to test the therapeutic potential and efficacy of BET/BRD protein inhibitors against cancer, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease (6). JQ1 is a well-characterized BET inhibitor that binds to the BRD domains in BET proteins with high specificity and displaces them from acetylated histones in chromatin (6). In other words, JQ1 is an inhibitor of the “reader” of the epigenetic code of histone acetylation. In kidneys, JQ1 was shown to delay cyst growth and preserve renal function in a murine model of polycystic kidney disease by inhibiting c-Myc gene and cystic epithelial cell proliferation (39). More recently, JQ1 was shown to reduce the expression of various proinflammatory mediators by blocking the activity of BRD4 in experimental models of unilateral ureteral obstruction, antiglomerular basement membrane nephritis, and angiotensin II infusion (33). Our present study now further demonstrates the beneficial effect of JQ1 in acute kidney injury models of cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Together, these a few studies support that BET/BRD inhibitors may have therapeutic potentials for both chronic and acute kidney diseases.

As an inhibitor of BET/BRD family proteins, JQ1 prevents the binding of BRD to acetylated histones in chromatin without suppressing BET/BRD protein expression. Consistently, JQ1 did not significantly affect BRD4 expression in our experiments (Fig. 4). Although JQ1 was initially shown to bind and inhibit BRD4, it may also inhibit BRD2 and BRD3 (3). BRD proteins could have overlapping and distinct functions (19). Thus future investigations are needed to determine the respective roles of individual BET/BRD family proteins in cisplatin nephrotoxicity.

Multiple signaling pathways contribute to renal tubular cell death during cisplatin nephrotoxicity (22, 25, 30). We and others have especially demonstrated a critical pathogenic role of DNA damage response and the associated p53 activation (12, 40). ATM (ataxia-telangiectasia mutated), ATR (ATM and Rad3 related), and DNA-PK (DNA-dependent protein kinase) kinases are the major molecular sensors of DNA damage (21). Our previous study showed that ATR is the major DNA damage sensor protein kinase in cisplatin nephrotoxicity, which accumulates to nuclear foci resulting in the phosphorylation of H2AX. Furthermore, ATR phosphorylates and activates Chk2, which further phosphorylates and activates p53 to induce apoptosis (26). In our present study, H2AX phosphorylation was not affected by JQ1, but Chk2 was (Fig. 5). This observation suggests that JQ1 may interfere with Chk2 activation during cisplatin treatment without reducing DNA damage or blocking the initial DNA damage-sensing process.

DNA damage response is the major cause of p53 activation in cisplatin nephrotoxicity (12, 40). Therefore, p53 inhibition by JQ1 observed in the present study can be explained by the inhibitory effect of JQ1 on DNA damage response. However, other mechanisms may contribute p53 regulation by JQ1 as well. For example, BRD4 was shown to be a functional partner of p53 (36). By this molecular interaction, BRD4 may cooperate with p53 to induce downstream target gene transcription (36). In the present study, we show that JQ1 inhibited p53 induction and phosphorylation during cisplatin treatment (Fig. 4). Moreover, the induction of PUMA-α (a proapoptotic p53 target gene in cisplatin nephrotoxicity; ref. 15), was prevented by JQ1. It remains unclear to what extents the effect of JQ1 on PUMA-α induction is by blocking BRD/p53 interaction. Interestingly, apart from phosphorylation, p53 is subjected to a variety of post-translational modifications, including acetylation. We and others detected p53 acetylation during cisplatin treatment of renal tubular cells (5, 18). Although being known as epigenetic “readers” of histone acetylation, the BET/BRD family proteins may also bind acetylated lysine residues in, and regulate, nonhistone proteins (6). It would be interesting to determine the relationship between p53 acetylation, BRD binding, and their regulation in cisplatin nephrotoxicity.

In addition to DNA damage response and p53 activation, MAPK signaling plays an important role in cisplatin nephrotoxicity (22, 25, 30). ERK1/2, JNK, and the p38 MAPKs constitute the MAPK family. Previous studies detected the phosphorylation/activation of MAPKs in cisplatin nephrotoxicity and inhibition of MAPKs reduced tissue damage and improved renal function in vivo (8, 17, 28). In TC71 and A673 cell lines, JQ1 directly inhibited ERK1/2 signaling in a dose- and time-dependent manner (11). In our present study, cisplatin treatment led to obvious phosphorylation/activation of ERK1/2, JNK and p38, and importantly, this activation was suppressed by JQ1 (Fig. 6). Thus JQ1 may also protect kidney cells and tissues in cisplatin nephrotoxicity partially by blocking MAPKs, although the mechanism whereby JQ1 inhibits MAPKs remains elusive.

Our study also provides the evidence for JQ1 regulation of several oxidative/nitrosative stress genes in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Oxidative/nitrosative stress is known to contribute to cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Upon cisplatin treatment, there is a robust production of reactive oxygen species in kidney cells and tissues, among which hydroxyl radicals accumulate rapidly and drastically. We showed previously that scavenging of hydroxyl radicals with dimethylthiourea led to the attenuation of p53 activation and the decrease of tubular cell death during cisplatin treatment (14). Nrf2 is a transcription factor responsible for the expression of key antioxidant genes, and recent studies have implicated Nrf2 in cellular defense against cisplatin nephrotoxicity (1, 31). HO-1 is a major renoprotective gene that is upregulated in various kidney injury models (20). Interestingly, HO-1 is also a downstream gene of Nrf2 involved in the regulation of intracellular redox-balancing (29). In our study, cisplatin induced the expression of Nrf2 in RPTC cells, which was further increased by JQ1 (Fig. 7). Similar effect was observed for JQ1 on HO-1 induction during cisplatin treatment. These results are consistent with the previous study by Hussong et al. (10), where BRD4 knockdown increased HO-1 expression by enhancing the Nrf2 DNA-binding affinity, demonstrating a role of BRD proteins in cellular response to oxidative stress. Together, these results suggest that upregulation of Nrf2 and its downstream cytoprotective genes (e.g., HO-1) may be responsible for the antioxidant defense effect of JQ1 in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Moreover, the iNOS expression and the formation of potent cytotoxic peroxynitrite through the interaction of superoxide radical with nitric oxide have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity (41). JQ1 was shown to reduce nitric oxide production in mice (35). Our data show that JQ1 significantly decreased the levels of iNOS expression (Fig. 7). Therefore, suppression of renal oxidative and nitrative stress by JQ1 likely contributes to the renoprotective effect of JQ1 in cisplatin nephrotoxicity.

Therapeutically, it is important to consider whether a renoprotective agent may affect the chemotherapy efficacy of cisplatin in tumors (24, 25); in other words, if a renoprotective agent significantly reduces or diminished chemotherapy effect, then the agent will not be useful clinically (2, 14). In this regard, JQ1 appears to be promising because JQ1 itself has anticancer effects against hematological cancers as well as solid tumors including nonsmall-cell lung cancer, prostate cancer, breast cancer, medulloblastoma, and neuroblastoma (4, 6, 32). We examined the effects of JQ1 on cisplatin-induced apoptosis in A549 nonsmall cell lung cancer cell line and AGS gastric cancer cell line. While cisplatin induced apoptosis in both cancer cell lines, JQ1 did not show significant effects. Thus JQ1 may have the potential to prevent cisplatin nephrotoxicity without compromising its anticancer efficacy. By demonstrating the renoprotective effect of JQ1 in cisplatin nephrotoxicity, our current study may pave the road for further preclinical tests in tumor-bearing animal models and clinical investigation in human patients.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 81430017, Science and Technology Planning Project of Shenzhen of China Grant JCYJ20150403101146288, Sanming Project-Chen Xiangmei Team of Shenzhen of China Grant 102, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants DK-058831 and DK-087843, and Department of Veterans Administration Grant 5I01BX000319.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.S., J.L., X.Z., and Z.D. conceived and designed research; L.S., J.L., and Y.Y. performed experiments; L.S., J.L., Y.Y., X.Z., and Z.D. analyzed data; L.S., J.L., X.Z., and Z.D. interpreted results of experiments; L.S. prepared figures; L.S. drafted manuscript; L.S., J.L., Y.Y., X.Z., and Z.D. approved final version of manuscript; Y.Y., X.Z., and Z.D. edited and revised manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aleksunes LM, Goedken MJ, Rockwell CE, Thomale J, Manautou JE, Klaassen CD. Transcriptional regulation of renal cytoprotective genes by Nrf2 and its potential use as a therapeutic target to mitigate cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 335: 2–12, 2010. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.170084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arany I, Megyesi JK, Kaneto H, Price PM, Safirstein RL. Cisplatin-induced cell death is EGFR/src/ERK signaling dependent in mouse proximal tubule cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F543–F549, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00112.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker EK, Taylor S, Gupte A, Sharp PP, Walia M, Walsh NC, Zannettino AC, Chalk AM, Burns CJ, Walkley CR. BET inhibitors induce apoptosis through a MYC independent mechanism and synergise with CDK inhibitors to kill osteosarcoma cells. Sci Rep 5: 10120, 2015. doi: 10.1038/srep10120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaidos A, Caputo V, Karadimitris A. Inhibition of bromodomain and extra-terminal proteins (BET) as a potential therapeutic approach in haematological malignancies: emerging preclinical and clinical evidence. Ther Adv Hematol 6: 128–141, 2015. doi: 10.1177/2040620715576662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong G, Luo J, Kumar V, Dong Z. Inhibitors of histone deacetylases suppress cisplatin-induced p53 activation and apoptosis in renal tubular cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F293–F300, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00410.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferri E, Petosa C, McKenna CE. Bromodomains: structure, function and pharmacology of inhibition. Biochem Pharmacol 106: 1–18, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Filippakopoulos P, Qi J, Picaud S, Shen Y, Smith WB, Fedorov O, Morse EM, Keates T, Hickman TT, Felletar I, Philpott M, Munro S, McKeown MR, Wang Y, Christie AL, West N, Cameron MJ, Schwartz B, Heightman TD, La Thangue N, French CA, Wiest O, Kung AL, Knapp S, Bradner JE. Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains. Nature 468: 1067–1073, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nature09504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Francescato HD, Costa RS, Júnior FB, Coimbra TM. Effect of JNK inhibition on cisplatin-induced renal damage. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 2138–2148, 2007. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Francescato HD, Costa RS, Silva CG, Coimbra TM. Treatment with a p38 MAPK inhibitor attenuates cisplatin nephrotoxicity starting after the beginning of renal damage. Life Sci 84: 590–597, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hussong M, Börno ST, Kerick M, Wunderlich A, Franz A, Sültmann H, Timmermann B, Lehrach H, Hirsch-Kauffmann M, Schweiger MR. The bromodomain protein BRD4 regulates the KEAP1/NRF2-dependent oxidative stress response. Cell Death Dis 5: e1195, 2014. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacques C, Lamoureux F, Baud’huin M, Rodriguez Calleja L, Quillard T, Amiaud J, Tirode F, Rédini F, Bradner JE, Heymann D, Ory B. Targeting the epigenetic readers in Ewing sarcoma inhibits the oncogenic transcription factor EWS/Fli1. Oncotarget 7: 24125–24140, 2016. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang M, Dong Z. Regulation and pathological role of p53 in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 327: 300–307, 2008. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.139162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang M, Wang CY, Huang S, Yang T, Dong Z. Cisplatin-induced apoptosis in p53-deficient renal cells via the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F983–F993, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90579.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang M, Wei Q, Pabla N, Dong G, Wang CY, Yang T, Smith SB, Dong Z. Effects of hydroxyl radical scavenging on cisplatin-induced p53 activation, tubular cell apoptosis and nephrotoxicity. Biochem Pharmacol 73: 1499–1510, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang M, Wei Q, Wang J, Du Q, Yu J, Zhang L, Dong Z. Regulation of PUMA-alpha by p53 in cisplatin-induced renal cell apoptosis. Oncogene 25: 4056–4066, 2006. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang M, Yi X, Hsu S, Wang CY, Dong Z. Role of p53 in cisplatin-induced tubular cell apoptosis: dependence on p53 transcriptional activity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F1140–F1147, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00262.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jo SK, Cho WY, Sung SA, Kim HK, Won NH. MEK inhibitor, U0126, attenuates cisplatin-induced renal injury by decreasing inflammation and apoptosis. Kidney Int 67: 458–466, 2005. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.67102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim DH, Jung YJ, Lee JE, Lee AS, Kang KP, Lee S, Park SK, Han MK, Lee SY, Ramkumar KM, Sung MJ, Kim W. SIRT1 activation by resveratrol ameliorates cisplatin-induced renal injury through deacetylation of p53. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 301: F427–F435, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00258.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar K, DeCant BT, Grippo PJ, Hwang RF, Bentrem DJ, Ebine K, Munshi HG. BET inhibitors block pancreatic stellate cell collagen I production and attenuate fibrosis in vivo. JCI Insight 2: e88032, 2017. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.88032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lever JM, Boddu R, George JF, Agarwal A. Heme oxygenase-1 in kidney health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 25: 165–183, 2016. doi: 10.1089/ars.2016.6659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maréchal A, Zou L. DNA damage sensing by the ATM and ATR kinases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 5: a012716, 2013. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller RP, Tadagavadi RK, Ramesh G, Reeves WB. Mechanisms of cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Toxins (Basel) 2: 2490–2518, 2010. doi: 10.3390/toxins2112490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ozkok A, Edelstein CL. Pathophysiology of cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. BioMed Res Int 2014: 967826, 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/967826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pabla N, Dong G, Jiang M, Huang S, Kumar MV, Messing RO, Dong Z. Inhibition of PKCδ reduces cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity without blocking chemotherapeutic efficacy in mouse models of cancer. J Clin Invest 121: 2709–2722, 2011. doi: 10.1172/JCI45586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pabla N, Dong Z. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: mechanisms and renoprotective strategies. Kidney Int 73: 994–1007, 2008. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pabla N, Huang S, Mi QS, Daniel R, Dong Z. ATR-Chk2 signaling in p53 activation and DNA damage response during cisplatin-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem 283: 6572–6583, 2008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707568200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pabla N, Ma Z, McIlhatton MA, Fishel R, Dong Z. hMSH2 recruits ATR to DNA damage sites for activation during DNA damage-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem 286: 10411–10418, 2011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.210989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramesh G, Reeves WB. p38 MAP kinase inhibition ameliorates cisplatin nephrotoxicity in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F166–F174, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00401.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sahin K, Tuzcu M, Gencoglu H, Dogukan A, Timurkan M, Sahin N, Aslan A, Kucuk O. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate activates Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Life Sci 87: 240–245, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sánchez-González PD, López-Hernández FJ, López-Novoa JM, Morales AI. An integrative view of the pathophysiological events leading to cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Crit Rev Toxicol 41: 803–821, 2011. doi: 10.3109/10408444.2011.602662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shelton LM, Park BK, Copple IM. Role of Nrf2 in protection against acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 84: 1090–1095, 2013. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi J, Vakoc CR. The mechanisms behind the therapeutic activity of BET bromodomain inhibition. Mol Cell 54: 728–736, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suarez-Alvarez B, Morgado-Pascual JL, Rayego-Mateos S, Rodriguez RM, Rodrigues-Diez R, Cannata-Ortiz P, Sanz AB, Egido J, Tharaux PL, Ortiz A, Lopez-Larrea C, Ruiz-Ortega M. Inhibition of bromodomain and extraterminal domain family proteins ameliorates experimental renal damage. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 504–519, 2017. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015080910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei Q, Dong G, Yang T, Megyesi J, Price PM, Dong Z. Activation and involvement of p53 in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1282–F1291, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00230.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wienerroither S, Rauch I, Rosebrock F, Jamieson AM, Bradner J, Muhar M, Zuber J, Müller M, Decker T. Regulation of NO synthesis, local inflammation, and innate immunity to pathogens by BET family proteins. Mol Cell Biol 34: 415–427, 2014. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01353-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu SY, Lee AY, Lai HT, Zhang H, Chiang CM. Phospho switch triggers Brd4 chromatin binding and activator recruitment for gene-specific targeting. Mol Cell 49: 843–857, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Y, Liu H, Liu F, Dong Z. Mitochondrial dysregulation and protection in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Arch Toxicol 88: 1249–1256, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00204-014-1239-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang D, Liu Y, Wei Q, Huo Y, Liu K, Liu F, Dong Z. Tubular p53 regulates multiple genes to mediate AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 2278–2289, 2014. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013080902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou X, Fan LX, Peters DJ, Trudel M, Bradner JE, Li X. Therapeutic targeting of BET bromodomain protein, Brd4, delays cyst growth in ADPKD. Hum Mol Genet 24: 3982–3993, 2015. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu S, Pabla N, Tang C, He L, Dong Z. DNA damage response in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Arch Toxicol 89: 2197–2205, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s00204-015-1633-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zirak MR, Rahimian R, Ghazi-Khansari M, Abbasi A, Razmi A, Mehr SE, Mousavizadeh K, Dehpour AR. Tropisetron attenuates cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in mice. Eur J Pharmacol 738: 222–229, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]