Abstract

Catecholamine (CA) neurons within the A1 and C1 cell groups in the ventrolateral medulla (VLM) potently increase food intake when activated by glucose deficit. In contrast, CA neurons in the A2 cell group of the dorsomedial medulla are required for reduction of food intake by cholecystokinin (CCK), a peptide that promotes satiation. Thus dorsal and ventral medullary CA neurons are activated by divergent metabolic conditions and mediate opposing behavioral responses. Acute glucose deficit is a life-threatening condition, and increased feeding is a key response that facilitates survival of this emergency. Thus, during glucose deficit, responses to satiation signals, like CCK, must be suppressed to ensure glucorestoration. Here we test the hypothesis that activation of VLM CA neurons inhibits dorsomedial CA neurons that participate in satiation. We found that glucose deficit produced by the antiglycolytic glucose analog, 2-deoxy-d-glucose, attenuated reduction of food intake by CCK. Moreover, glucose deficit increased c-Fos expression by A1 and C1 neurons while reducing CCK-induced c-Fos expression in A2 neurons. We also selectively activated A1/C1 neurons in TH-Cre+ transgenic rats in which A1/C1 neurons were transfected with a Cre-dependent designer receptor exclusively activated by a designer drug (DREADD). Selective activation of A1/C1 neurons using the DREADD agonist, clozapine-N-oxide, attenuated reduction of food intake by CCK and prevented CCK-induced c-Fos expression in A2 CA neurons, even under normoglycemic conditions. Results support the hypothesis that activation of ventral CA neurons attenuates satiety by inhibiting dorsal medullary A2 CA neurons. This mechanism may ensure that satiation does not terminate feeding before restoration of normoglycemia.

Keywords: chemogenetics, cholecystokinin, 2-deoxy-d-glucose, glucoprivation, satiation

INTRODUCTION

There is abundant evidence that catecholamine (CA) neurons located in the dorsal and ventral hindbrain participate in control of food intake. However, dorsal and ventral CA neurons differ dramatically both with regard to the stimuli that engage them and the responses they facilitate. A subgroup of CA neurons in the ventrolateral medulla (VLM) is essential for responding to life-threatening decreases in glucose availability (glucoprivation) (25, 40, 42, 43, 47). These neurons are located in cell groups C1 and rostral A1 (25) among CA neurons that mediate responses to a variety of other physiological emergencies, such as hypotension, nociception, and hypoxia (12). The respective roles and relative importance of C1 and rostral A1 neurons in glucoregulation have not been fully distinguished. However, activation of C1 and rostral A1 neurons by glucoprivation evokes powerful counterregulatory responses that increase glucose availability, including increased food intake, corticosterone secretion, and mobilization of glucose from peripheral storage sites (1, 22, 39–43, 47).

Dorsal hindbrain neurons in noradrenergic cell group A2 lie within the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS). In contrast to VLM CA neurons, A2 neurons are activated by vagal afferent neurons that respond to cholecystokinin (CCK), a gastrointestinal peptide secreted when alimentation is adequate or in response to increased gastric distension (11, 32, 36–38, 50), and during pathology, stress, and malaise, conditions that also reduce food intake (33). Thus dorsal and ventral CA neurons are activated under divergent metabolic or nutritional conditions and contribute to diametrically opposite behavioral responses, both of which are important for overall metabolic homeostasis. Nevertheless, feeding in response to glucoprivation is an urgent matter and would seem to require suppression of any response that might interfere with increased ingestion. However, circuitry that may enable this interaction is unclear. Therefore, in this experiment, we hypothesized that CCK-induced reduction of food intake and activation of A2 CA neurons are attenuated during glucoprivation and that this attenuation is mediated via activation of CA neurons in the C1 and rostral A1 regions of the VLM.

In this study, we examined the activation of CA neurons in A1/C1 (the overlap of rostral A1 and C1) and A2 and the feeding responses they mediate following administration of CCK and the production of glucose deficit. Our results confirm earlier observations showing that CCK activates a subgroup of A2 neurons (8, 33, 35), whereas glucoprivation induced by 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2DG) activates subgroups of CA neurons within C1 and rostral A1 (25, 39, 43, 44). We also found that systemic 2DG attenuates both CCK-induced activation of A2 neurons and CCK-induced reduction of food intake. Our hypothesis that attenuation of CCK-induced reduction of food intake and inhibition of A2 neurons is mediated by activation of VLM CA neurons also was supported by our observation that selective chemogenetic activation of A1/C1 neurons reduces c-Fos expression in A2 neurons and attenuates CCK-induced reduction of food intake in the absence of glucoprivation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Adult female Long-Evans rats expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the tyrosine hydroxylase (Th) promoter [Long-Evans-Tg(Th-Cre) 3.1] and their wild-type non-Cre littermates (Th-Cre+ and Th-Cre− rats, respectively) (55) and adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Simonsen Laboratories) were used in these experiments. Transgenic rats were bred in the VBRB vivarium at Washington State University from breeding stock generously provided by Dr. Karl Deisseroth (Stanford University). Genotyping of transgenic rats was performed from an ear punch at 3 wk of age using PCR, as described previously (25). Rats were maintained on a 12-h:12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 AM) with ad libitum access to pelleted rodent food (catalog no. 5001; LabDiet), except during tests described below. Tap water was always available ad libitum. All experimental procedures conform to NIH guidelines and were approved by Washington State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Experimental Design

Feeding tests.

All feeding tests were conducted in the animals’ home cages using standard pelleted rodent diet, and experimental tests were separated by at least 3 days. All tests were initiated in the morning, during the animals’ light phase, beginning at 8:30 AM. Because metabolic context modulates the potency of CCK in suppressing food intake, experiments examining interaction of 2DG (Sigma-Aldrich) and CCK (CCK octapeptide; Peptides International) and those experiments examining the interaction of selective clozapine-N-oxide (CNO; Tocris) activation of VLM CA neurons with CCK were conducted in the morning after 16-h (overnight) food deprivation. In this case, we expected that control levels of food intake would be high and most likely reveal robust reductions of intake by CCK under control conditions. For other experiments, testing occurred in the morning after 1 or 3 h of food deprivation so that control intake would be low and the stimulatory effects of 2DG would be apparent.

Interaction of 2DG and CCK in control of food intake.

In this group of experiments, we tested the hypothesis that 2DG-induced glucoprivation would attenuate CCK-induced reduction of food intake. We examined responses of both males and females to determine whether food intake was altered in a similar way in each sex when 2DG and CCK were administered together in our testing protocol. Stage of estrous was not assessed in the female rats. After 16-h (overnight) food deprivation, transgenic female (n = 14, 247.6 ± 4.9 g body wt, 15–18 wk old) and Sprague-Dawley male (n = 12, 296.2 ± 6.9 g body wt , 11–12 wk old) rats were injected with 2DG (200 mg/kg sc) or saline (Sal) and 60 min later with CCK (5 μg/kg ip) or Sal using the following combinations: Sal + Sal, 2DG + Sal, Sal + CCK, 2DG + CCK. Because food intake, measured 30 and 60 min after the second injection, was similar in males and females, both sexes were used in the remaining experiments. However, each experiment utilized only one sex.

Effects of 2DG on CCK-induced c-Fos expression in the hindbrain.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 14, 431.0 ± 6.8 g body wt; 14–15 wk old), after 3-h food deprivation, were injected with 2DG (200 mg/kg sc) or Sal, 20 min before a Sal or CCK (5 μg/kg ip) injection. Treatment groups were Sal + Sal, 2DG + Sal, Sal + CCK, 2DG + CCK. Food was withheld for 90 min after the second injection to allow for expression of c-Fos, and rats were then euthanized and prepared for immunohistochemical analysis. Coronal sections were collected and processed for detection and quantification of dopamine-β hydroxylase (DBH) and c-Fos immunoreactivity in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMV), the NTS, and VLM. DBH was used to identify CA neurons, and c-Fos was used as an indicator of neuronal activation. To further test the effects of 2DG and CCK on c-Fos expression, 16-h overnight fasted female transgenic rats (n = 14, 250.1 ± 4.7 g body wt, 17–21 wk old) were injected with 2DG or Sal followed 60 min later by CCK or Sal, using the same drug combinations and doses as described above. Food was withheld, and brains were collected 90 min after the second injection for immunohistochemical analysis of c-Fos and DBH neurons in A1/C1, middle C1 (C1m), and rostral C1 (C1r).

Effects of selective chemogenetic activation of A1/C1 CA neurons on CCK-induced satiety and c-Fos expression in NTS and VLM.

In this group of experiments, Th-Cre+ transgenic rats with A1/C1 transfection of the designer receptor exclusively activated by a designer drug (DREADD) virus were tested to determine whether selective activation of A1/C1 CA neurons in the absence of systemic glucoprivation would produce effects on CCK-induced feeding and c-Fos expression that are similar to those produced by systemic 2DG.

In previous work, we demonstrated the selectivity of DREADD transfection in VLM CA neurons and the effectiveness of systemic CNO in activating these neurons and stimulating feeding (25). In the present experiments, the efficacy, specificity, and localization of the virus transfection were confirmed by feeding tests using the DREADD receptor agonist, CNO (1 mg/kg ip) to induce feeding. In this test, 2DG (200 mg/kg sc), CNO (1 mg/kg ip), or Sal control were tested in separate groups of female Th-Cre+ rats in which the DREADD construct was transfected bilaterally in A1/C1 (n = 16, 262.2 ± 4.8 g body wt, 19–20 wk old) to establish equivalency of 2DG and CNO doses for stimulation of feeding in a 4-h test in 1-h food-derived rats. Nontransfected female Th-Cre+ rats were also tested using the same drug doses and protocol to assure that the stimulation of feeding by CNO was in fact mediated by the activations of CNO of transfected neurons and not by activation of other neurons, for example, by CNO itself or by CNO breakdown products (n = 10, 259.8 ± 9.4 g body wt, 17–20 wk old).

We next examined the effect of CNO (1 mg/kg ip) on reduction of food intake by CCK (5 µg/kg ip) in 16-h food-deprived female Th-Cre+ rats with DREADD transfection of A1/C1 neurons (n = 16, 266.3 ± 4.9 g body wt, 21–22 wk old). Treatment groups were Sal + Sal, CNO + Sal, Sal + CCK, CNO + CCK, with the first injection delivered 60 min before the second injection. Food intake was measured at 30 and 60 min after the second injection. These same treatments and protocol were then repeated to examine CCK-induced c-Fos expression in NTS and VLM. In this test, food was withheld during the test, and rats were euthanized 90 min after the second injection. Brain tissue was prepared as described for visualization and quantification of c-Fos in the NTS and VLM.

Adeno-associated virus injection into A1/C1.

Catecholamine cell groups in the hindbrain are defined as described in The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (30). Cell bodies of group A2 neurons are located in the caudal portion of the NTS in the dorsal hindbrain. Those of groups C1 and A1 are continuously distributed along the rostrocaudal extent of the VLM. We refer to the overlap of C1 with rostral A1 as A1/C1 (14.1–13.4 mm caudal to bregma), the medial portion of C1 as C1m (13.3–12.5 mm caudal to bregma), and the most rostral portion of C1 as C1r (12.4–11.8 mm caudal to bregma). For intracranial injections, rats were anesthetized using 1.0 ml/kg of ketamine-xylazine-acepromazine cocktail (50 mg/kg ketamine HCl, Fort Dodge Animal Health; 5.0 mg/kg xylazine, Vedco; 1.0 mg/kg acepromazine, Vedco) and placed in a stereotaxic device. Rats were injected with the recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV) (serotype 2) containing a Cre-dependent doubly floxed inverted open reading frame encoding a reporter gene (mCherry) under a human synapasin I promotor, AAV2-DIO-hSyn-hM3D(Gq)-mCherry (AAV-hM3D, 1–2 × 1012 particles/ml, University of North Carolina Vector Core). Following transfection with this vector, the DREADD receptor is selectively expressed only by Cre-expressing neurons, in this case A1/C1 CA neurons.

Injections (200 nl/site) were delivered bilaterally into the A1/C1 area through a pulled glass capillary pipette (30-µm tip diameter), using a Picospritzer. Pipettes entered the brain dorsolateral to the targeted VLM site and were driven ventromedially at a 14° angle to avoid inadvertent damage to or transfection of CA neurons in NTS by potential diffusion of the viral construct along the pipette tract. The following coordinates were used: 13.75 mm caudal to bregma, 4.0–4.1 mm lateral to midline, and 8.4–8.9 mm ventral to the skull surface (30). Previous work from our laboratory has shown that mCherry expression in CA neurons is maximal and stable between 5 and 10 wk after the virus injection (25). Therefore, all tests were conducted 5–10 wk after transfection. Th-Cre− rats with AAV-hM3D injection into VLM showed no mCherry expression, indicating that expression of the construct was Cre dependent, as anticipated. As described above, the efficacy, specificity, and localization of the virus transfection were confirmed, first by feeding tests using the receptor agonist CNO (1 mg/kg ip) to induce feeding and, after completion of behavioral tests, were further confirmed by immunohistochemical detection of the reporter gene mCherry and c-Fos expression in the VLM CA neurons following CNO injection. Our previous work has shown that selective activation of CA neurons in the C1 and rostral A1 subregions by systemic CNO elicits feeding with a potency and time course comparable to systemic injection of the glucoprivic agent, 2DG (25). In this experiment, we did not inject DREADD constructs into the dorsal hindbrain, as we have not been able to identify a construct that selectively transfects A2 neurons in these transgenic rats.

Immunohistochemical analyses.

The effects of the above treatments, as in Experimental Design, on neuroanatomical parameters were investigated using immunohistochemistry (IHC). Rats were tested in the morning after a 3- or 16-h (overnight) fast using the same dose and drug combinations as described above, except that animals did not receive food after the second injection. Ninety minutes after the second injection, they were euthanized by deep isoflurane-induced anesthesia (Halocarbon Products). Just before cessation of the heartbeat, rats were perfused transcardially with PBS (pH 7.4), followed by freshly made 4% formaldehyde/PBS solution. Brains were rapidly removed and placed in 4% formaldehyde/PBS for 5 h, followed by immersion in 25% sucrose in PBS overnight at room temperature. Brains were then cut at 40-µm thickness using a cryostat. Coronal brain sections (three serial sets) were collected for analysis of the distribution and selectivity of the transfected AAV-hM3D, expression of c-Fos induced by the treatments, and expression of CA biosynthetic enzyme, DBH. For double or triple immunofluorescence staining, sections were incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C (2 days) in 10% normal horse serum (NHS)/PBS, washed, and then incubated in secondary antibodies (4 h) (21, 24). The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-DsRed (ClonTech Laboratories, for detecting mCherry), mouse anti-DBH (Millipore, for detecting CA neurons), and goat anti-c-Fos (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Secondary antibodies were donkey anti-mouse, donkey anti-rabbit, or donkey anti-goat, conjugated with Alexa 488, Cy3, or Alexa 647 (all diluted 1:500 in 1% NHS/PBS; Jackson ImmunoResearch). Sections were mounted and coverslipped with ProLong Gold medium (ThermoFisher Scientific) then examined and photographed using a Zeiss epifluorescent microscope.

Cell counting in VLM and NTS.

Cells with positive IHC staining were counted manually in VLM and NTS CA regions from digital images. Cells with positive staining in A1/C1, C1m, and C1r regions (at 13.8–13.5, 13.1–12.8, and 12.3–12.0 mm caudal to bregma, respectively) were counted in three (2DG + CCK experiments) or four (CNO + CCK experiments) sections per rat for each region. Extent of the AAV diffusion from the targeted transfection site (A1/C1) was measured as the range of sections with greater than five mCherry+ cells in the VLM. Positive cells in caudal NTS were counted at five rostrocaudal levels at 14.2–14.0, 13.9–13.6, 13.5–13.2, 13.1–12.7, and 12.6–12.4 mm caudal to bregma, respectively, and labeled as NTS-1, -2, -3, -4, and -5 in this study. For NTS-4, three (2DG + CCK experiments) or four (CNO + CCK experiments) sections per rat were counted. For all other NTS subregions, two sections per rat were counted. Data were presented as averages per side for each subregion.

Statistics

All results are presented as means ± SE. One-way or two-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis of data. After significance was determined, multiple comparisons between individual groups were tested by a post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All results are presented as means ± SE. One-way or two-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis of data. After significance was determined, multiple comparisons between individual groups were tested by a post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

2DG Reduced Satiety Effects of CCK

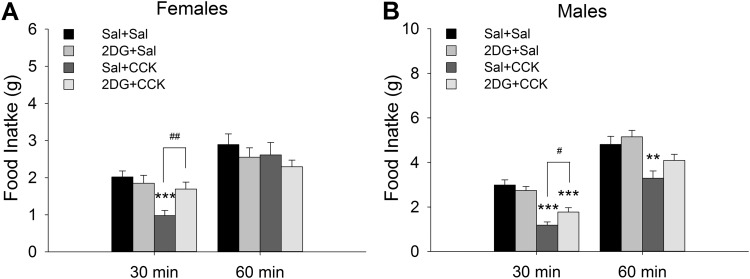

CCK significantly reduced food intake in 16-h food-deprived rats, and 2DG preinjection reduced the satiety effect of CCK in both female and male rats (Fig. 1). One-way ANOVA indicated significance among all groups during the first 30 min of the test in females [F(3,55) = 6.624, P < 0.001, n = 14 rats/group] and males [F(3,47) = 18.6, P < 0.001, n = 12 rats/group]. Post hoc analysis revealed that feeding was significantly reduced in Sal + CCK female and male rats during the first 30 min after the CCK injection (P < 0.001, Sal + CCK vs. Sal + Sal). The satiety effect of CCK was no longer significant at 60 min in females (P = 0.479 among groups) but remained significant in males (P = 0.004, Sal + CCK vs. Sal + Sal). In both females and males, preinjection with 2DG reduced satiety effect of CCK (P = 0.007 and 0.039, for females and males, respectively, 2DG + CCK vs. Sal + CCK). After overnight deprivation, food intake was increased significantly in both Sal + Sal and 2DG + Sal males and females, but intakes after 2DG + Sal did not differ from intakes after Sal + Sal in either males (P = 0.37) or females (P = 0.499).

Fig. 1.

Pretreatment with 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2DG) antagonizes cholecystokinin (CCK)-induced reduction of food in both female and male rats. After 16-h (overnight) food deprivation, female (A) and male (B) rats were injected with 2DG (200 mg/kg sc) or saline (Sal) and 60 min later with CCK (5 µg/kg ip) or Sal. Food intake 30 and 60 min after the last injection was measured. CCK significantly reduced 30-min food intake in both males and females, and 2DG reduced this inhibition. Data are expressed as means ± SE, n = 14 and 12 rats for each treatment in A and B, respectively. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. Sal + Sal; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, 2DG + CCK vs. Sal + CCK (by post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls test after 1-way ANOVA).

2DG Reduced CCK-Induced c-Fos Expression in A2 Neurons But Increased c-Fos in A1/C1 Neurons

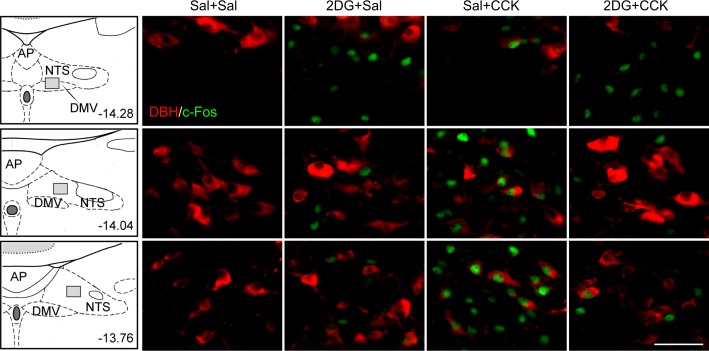

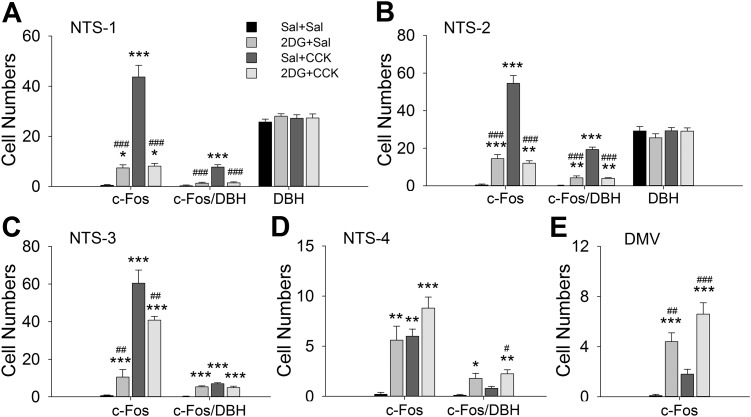

Preinjection of 2DG (200 mg/kg sc) significantly reduced CCK-induced c-Fos expression in the hindbrain in 3-h food-deprived male rats. Figure 2 shows high-magnification immunofluorescent images from NTS and DMV from the four treatment groups. Figure 3 shows quantified data for DBH, c-Fos, and DBH/c-Fos immunoreactive cells for four NTS and one DMV level. CCK significantly increased c-Fos expression in A2 CA neurons in caudal NTS [F(3,27) = 32.424, 89.697, 19.700, P < 0.001 between groups for NTS-1, -2, and -3; P < 0.001, Sal + CCK vs. Sal + Sal; n = 6–8 sections per group per subregion from 3 to 4 rats per group] but not in A1/C1 CA neurons in the VLM (Fig. 4). CCK also activated significant numbers of non-CA neurons in the NTS (NTS-1 through NTS-4; Fig. 3). In contrast, 2DG increased c-Fos expression in A1/C1 CA neurons (Fig. 4), activated very few A2 neurons, and significantly reduced CCK-induced c-Fos expression in NTS A2 neurons (P < 0.001, 2DG + CCK vs. Sal + CCK at NTS-1 and NTS-2; Fig. 3). In DMV, 2DG, but not CCK, enhanced c-Fos expression (Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 2.

Effect of 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2DG) on cholecystokinin (CCK)-induced c-Fos expression in hindbrain catecholamine (CA) and non-CA neurons. After 3-h food deprivation, male rats were injected with saline (Sal) or 2DG (200 mg/kg sc) 20 min before a Sal or CCK (5 µg/kg ip) injection. Food was withheld for 90 min, and rats were then euthanized and prepared for immunohistochemical analysis. Coronal sections, including dorsal motor nucleus of vagus (DMV) and 2 nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) subregions (NTS-1 at 14.01 and NTS-2 at 13.76 mm caudal to bregma, respectively), are shown for the 4 treatments. Red labeling indicates dopamine-β hydroxylase (DBH) immunoreactivity (-ir), and green indicates c-Fos-ir. Schematic representation of coronal brain sections is presented on the left, and distance (in mm) caudal to bregma is shown. High-magnification immunofluorescent images show the region indicated by shaded rectangles in each schematic. Bar = 50 µm. AP, area postrema.

Fig. 3.

Cell counts in nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) and dorsal motor nucleus of vagus (DMV) subregions in 3-h-fasted male rats. Rats were treated as in Fig. 2. Cells showing c-Fos, dopamine-β hydroxylase (DBH), or c-Fos/DBH staining were counted at each of 4 different rostrocaudal levels of NTS, NTS-1 (A), -2 (B), -3 (C), and -4 (D) (at 14.2–14.0, 13.9–13.6, 13.5–13.2, and 13.1–12.7 mm caudal to bregma, respectively), and in DMV (E) (at 14.3–14.1 mm caudal to bregma). Data shown are means ± SE from 3–4 rats per treatment. n = 6–8 sections per group per subregion. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. saline (Sal) + Sal; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. Sal + cholecystokinin (CCK) (by post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls test after 1-way ANOVA). 2DG, 2-deoxy-d-glucose.

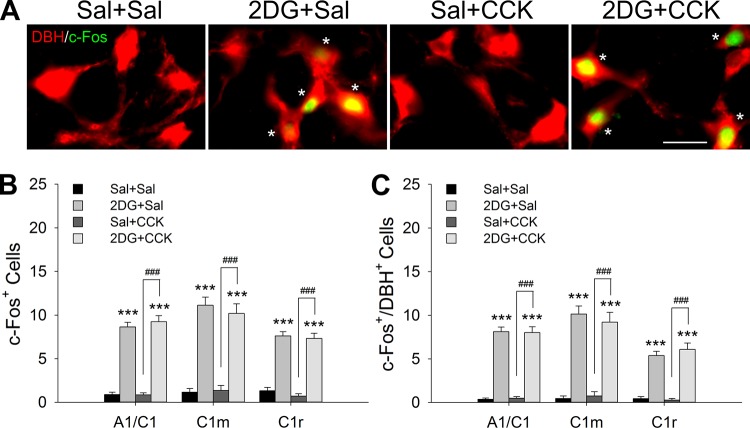

Fig. 4.

Cell counts in C1 and rostral A1 overlap (A1/C1) (A), middle C1 (C1m) (B), and rostral C1 (C1r) (C) subregions in 3-h-fasted male rats. 4 groups of rats were treated as in Fig. 3 and euthanized for immunohistological analysis. Average counts of c-Fos, dopamine-β hydroxylase (DBH), and c-Fos/DBH in A1/C1, C1m, and C1r are shown as means ± SE from 3–4 rats per treatment. n = 6–8 sections per group per subregion. ***P < 0.001 vs. saline (Sal)-Sal; ###P < 0.001 vs. Sal + cholecystokinin (CCK) (Student-Newman-Keuls test after 1-way ANOVA). 2DG, 2-deoxy-d-glucose.

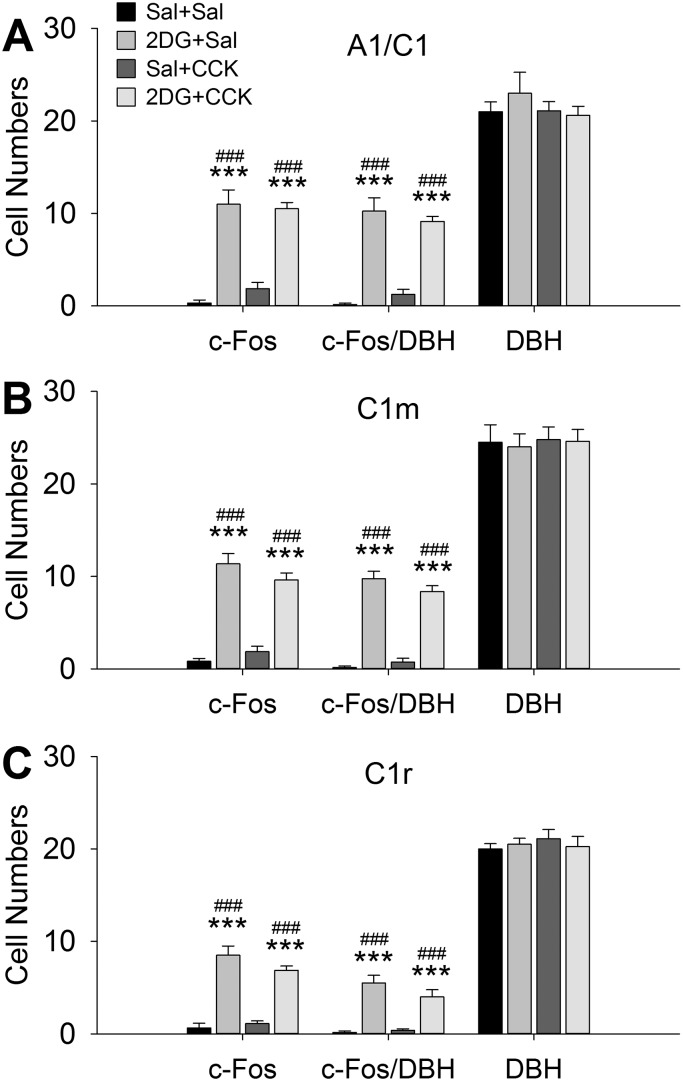

CCK Did Not Alter 2DG-Induced Activation of VLM Neurons

As shown in Fig. 4, 2DG activated CA neurons in A1/C1, C1m, and C1r in these 3-h food-deprived male rats [F(3,27) = 33.654, 71.188, 18.334, respectively, for A1/C1, C1m, and C1r, P < 0.001 among groups; P < 0.001, 2DG + Sal or 2DG + CCK vs. Sal + Sal; n = 6–8 sections per group per subregion from 3 to 4 rats per group]. In contrast, CCK did not increase c-Fos in any of the VLM CA subgroups (P > 0.419, Sal + CCK vs. Sal + Sal) and did not reduce 2DG-induced c-Fos expression in these neurons (P > 0.089, 2DG + CCK vs. 2DG + Sal). Similarly, in overnight fasted female rats, most of the neurons in VLM activated by 2DG were CA neurons (Fig. 5). As in 3-h fasted rats, 2DG significantly increased c-Fos expression in DBH-immunoreactive neurons in A1/C1, C1m, and C1r [F(3,41) = 89.078, 55.618, 42.871, respectively, for A1/C1, C1m, and C1r, P < 0.001 among groups; P < 0.001, 2DG + Sal or 2DG + CCK vs. Sal + Sal; n = 9–12 sections per group per subregion from 3 to 4 rats per group], and this effect was not altered by CCK (P > 0.358, 2DG + CCK vs. 2DG + Sal). In addition, CCK alone did not increase or decrease c-Fos in VLM non-CA neurons.

Fig. 5.

Expression of c-Fos in ventrolateral medulla in overnight fasted female rats. After 16-h (overnight) food deprivation, female rats were injected with 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2DG) (200 mg/kg sc) or saline (Sal) and 60 min later with cholecystokinin (CCK) (5 µg/kg ip) or Sal. Brains were collected for immunohistochemistry 90 min after the last injection. A: representative images of dopamine-β hydroxylase (DBH) (red) and c-Fos (green) double staining in C1 and rostral A1 overlap (A1/C1) region. Asterisks in the photomicrographs indicate double-labeled neurons. Bar = 25 µm. B: c-Fos-positive cells in A1/C1, middle C1 (C1m), and rostral C1 (C1r) catecholamine subregions. C: double-labeled c-Fos/DBH cells in A1/C1, C1m, and C1r. Data shown are means ± SE from 3–4 rats per treatment. n = 9–12 sections per group per subregion. ***P < 0.001 vs. Sal + Sal; ###P < 0.001 2DG + CCK vs. Sal + CCK (by post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls test after 1-way ANOVA).

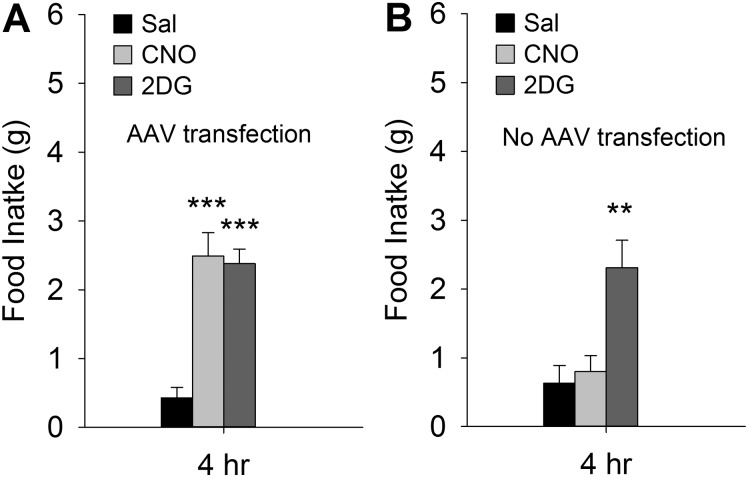

Systemic CNO Increased Feeding in VLM AAV-hM3D-Transfected Rats But Not in Nontransfected Rats

The importance of VLM CA neurons for reducing CCK-induced satiation was further tested using chemogenetic tools to produce selective activation of A1/C1 neurons. First, the dependence of CNO-induced feeding on activation of CA neurons was tested using A1/C1 AAV-hM3D-Gq-transfected (Fig. 6A) and nontransfected (Fig. 6B) female Th-Cre+ rats. In transfected rats, systemic CNO (1 mg/kg ip) stimulated feeding with potency similar to systemic 2DG [200 mg/kg sc; F(2,47) = 22.261, P < 0.001 among groups; P = 0.747, CNO vs. 2DG; n = 16 rats per group]. In contrast, CNO did not stimulate feeding in nontransfected rats [F(2,29) = 9.222, P < 0.001 among groups; P = 0.697, CNO vs. Sal; n = 10 rats per group], indicating that CNO-induced stimulation of feeding was due to its effect on transfected neurons.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) and 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2DG) effects on food intake in A1/C1AAV-hM3D-transfected and nontransfected rats. Female Th-Cre+ rats transfected bilaterally with injection of adeno-associated virus (AAV)-hM3D into the C1 and rostral A1 overlap (A1/C1) cell group (A) and nontransfected female Th-Cre+ rats (B) were used in these experiments. They were tested for intake of standard rodent chow in a 4-h test following systemic injection of saline (Sal) (intraperitoneally), 2DG (200 mg/kg sc), or CNO (1 mg/kg ip). Intake of chow was increased equally by 2DG and CNO in transfected rats. Nontransfected rats increased their food intake in response to 2DG but not to CNO. n = 16 or 10 rats per treatment for A and B, respectively. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. Sal (by post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls test after 1-way ANOVA).

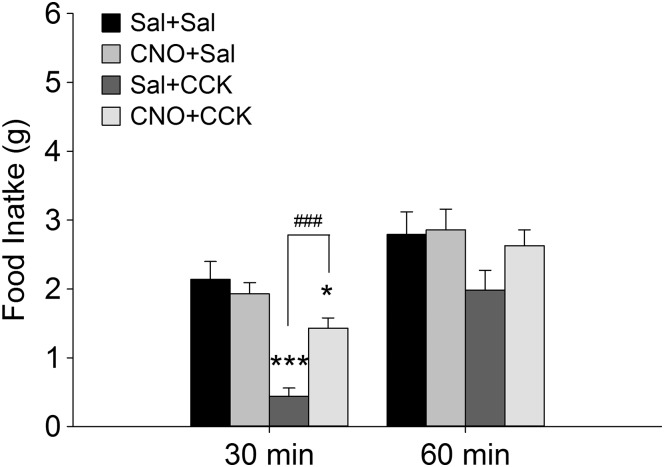

Selective CNO Activation of A1/C1 CA Neurons Reduced CCK-Induced Satiation

We then tested the effect of CNO and CCK on food intake in female Th-Cre+ rats after bilateral AAV-hM3D-Gq transfection of A1/C1. Rats were food deprived overnight and tested in the morning using the same protocol as in 2DG + CCK pairings. Figure 7 shows that food intake was significantly reduced at the 30-min time point in Sal + CCK rats [F(3,63) = 17.340, P < 0.001 among groups; P < 0.001, Sal + CCK vs. Sal + Sal; n = 16 rats per group) and that this reduction of food intake was blocked in the CNO + CCK rats (P < 0.001, CNO + CCK vs. Sal + CCK). The CCK-induced reduction of food intake was no longer significant in Sal + CCK rats after 60 min (P = 0.127 among groups), as also shown in Sal + CCK females without AAV transfection in Fig. 1.

Fig. 7.

Effects of clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) on reduction of food intake by cholecystokinin (CCK) in A1/C1AAV-hM3D-transfected rats. AAV, adeno-associated virus; A1/C1, C1 and rostral A1 overlap region. Female A1/C1AAV-hM3D rats were fasted (16 h) and tested to determine the effects of CNO on CCK-induced suppression of food intake. Results show that food intake was reduced significantly 30 min after CCK injection in saline (Sal) + CCK rats, compared with Sal + Sal rats, whereas preinjection of CNO (1 mg/kg ip) reduced the satiety effect of CCK (CNO + CCK). Data are means ± SE. n = 16 rats for each treatment. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs. Sal + Sal; ###P < 0.001 CNO + CCK vs. Sal + CCK (by post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls test after 1-way ANOVA).

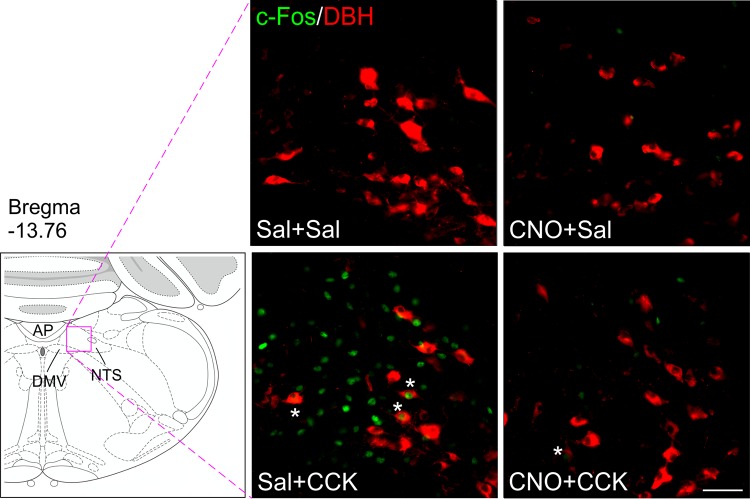

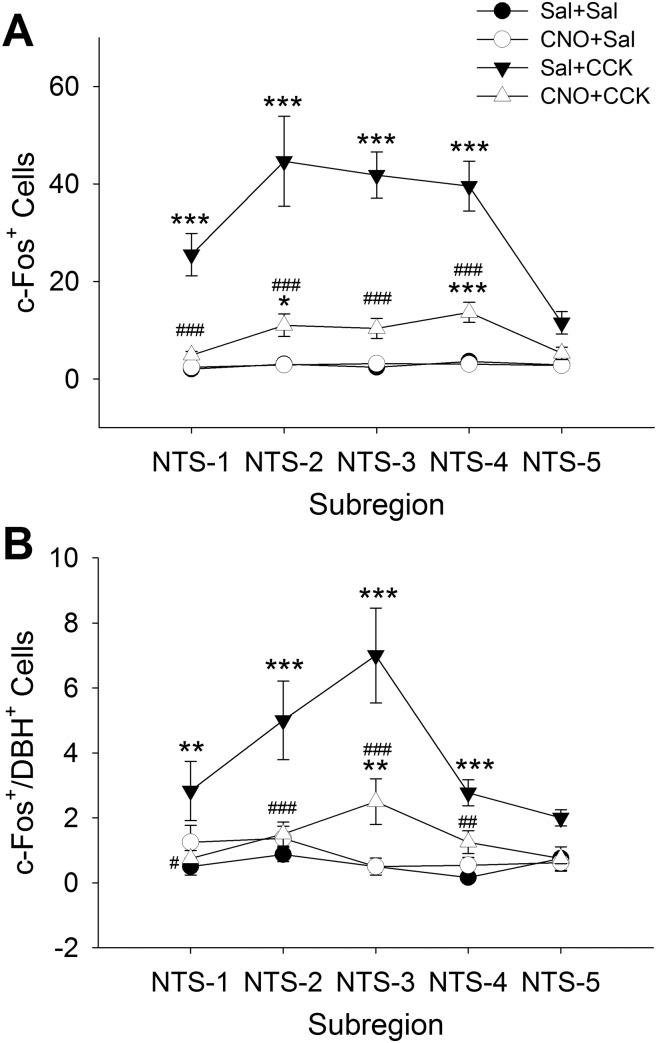

Selective CNO Activation of A1/C1 CA Neurons Reduced CCK-Induced c-Fos Expression in A2 Neurons

Using protocols described above, we also examined effects of CNO on CCK-induced c-Fos expression in NTS CA neuron in female A1/C1AAV-hM3D rats. Figure 8 shows that CCK (5 µg/kg ip) activated c-Fos in a subpopulation of CA neurons in caudal NTS levels and that prior injection of CNO (1 mg/kg ip) reduced this effect. Figure 9 shows quantification and distribution of c-Fos+ and c-Fos+/DBH+-expressing cells at five levels of the NTS in each of the four treatment groups (Sal + Sal, CNO + Sal, Sal + CCK, CNO + CCK). Total c-Fos expression was elevated in Sal + CCK rats, mostly in the caudal NTS, or NTS-1, -2, -3, and -4 (P < 0.001, Sal + CCK vs. Sal + Sal, post hoc test after 2-way ANOVA revealing P < 0.001 for treatment, NTS levels, and interaction; n = 6–8 sections per group per subregion from 3–4 rats per group), but not in rostral NTS-5 (P = 0.084). Although in CNO + CCK rats, this number was reduced nearly to that of Sal + Sal rats, whereas CNO + Sal rats were indistinguishable from Sal + Sal rats with respect to NTS total c-Fos expression (Fig. 9A). Although the number of DBH cells that were activated in these levels of the NTS was smaller than the total number of CCK-activated neurons (Fig. 9B), the relative distribution and level of activation across treatment groups were similar to total c-Fos expression (P < 0.01, Sal + CCK vs. Sal + Sal at NTS-1 through NTS-4). CNO significantly reduced CCK-induced activation of A2 CA neurons (P < 0.05, CNO + CCK vs. Sal + CCK at NTS-1 through NTS-4).

Fig. 8.

Expression of c-Fos in nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) after clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) and cholecystokinin (CCK) injection in A1/C1AAV-hM3D rats. AAV, adeno-associated virus; A1/C1, C1 and rostral A1 overlap region. Female A1/C1AAV-hM3D rats were treated in 4 groups as in Fig. 7, and brain tissues were prepared for immunohistochemistry 90 min later after the last injection. Representative images of dopamine-β hydroxylase (DBH) (red) and c-Fos (green) from NTS-2 (13.76 mm caudal to bregma) are shown. Schematic representation of coronal brain section is presented on the left, and distance (in mm) caudal to bregma is shown. High-magnification immunofluorescence images show the region indicated by a pink rectangle for each group. Asterisks in the photomicrographs indicate double-labeled (c-Fos/DBH) neurons. Bar = 50 µm. Sal, saline; AP, area postrema; DMV, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus.

Fig. 9.

Effects of clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) and cholecystokinin (CCK) on nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) c-Fos expression in A1/C1AAV-hM3D rats. AAV, adeno-associated virus; A1/C1, C1 and rostral A1 overlap region. Cell counts of total c-Fos-positive (A) or double-stained [c-Fos/dopamine-β hydroxylase (DBH) (B)] cells at 5 rostrocaudal levels of the NTS, designated on the x-axis as NTS-1, -2, -3, -4, and -5 (14.2–14.0, 13.9–13.6, 13.5–13.2, 12.1–12.7, and 12.6–12.4 mm caudal to bregma, respectively). Female A1/C1AAV-hM3D rats were treated, as in Fig. 8, with the following drug combinations: saline (Sal) + Sal, CNO + Sal, Sal + CCK, CNO + CCK. Brains were collected 90 min after the last injection for immunohistochemistry. Data shown are means ± SE from 3–4 rats per treatment. n = 6–8 sections per group per subregion (n = 9–12 sections for NTS-4). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. Sal + Sal; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 CNO + CCK vs. Sal + CCK (by post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls test after 2-way ANOVA).

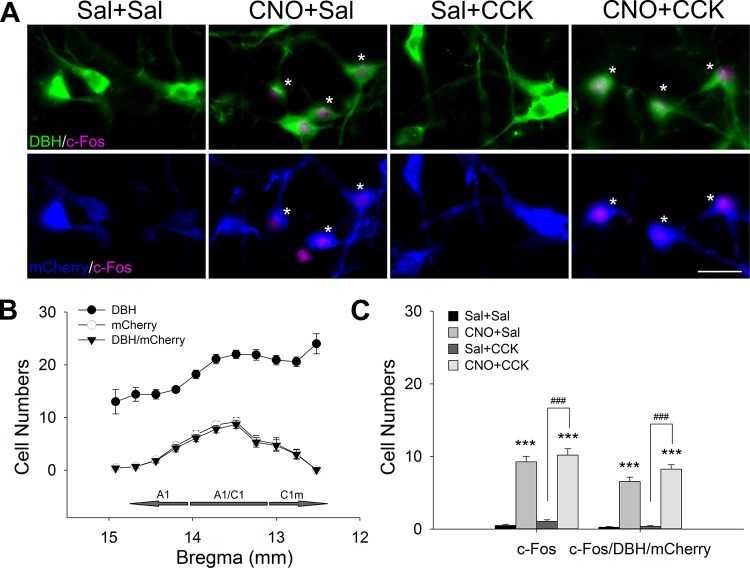

Expression of c-Fos in VLM after CNO and CCK injections in female A1/C1AAV-hM3D rats is shown in Fig. 10. AAV transfection was limited to DBH neurons, and the double-stained (mCherry/DBH) and mCherry-positive cells were concentrated in A1/C1 region within the area targeted by the AAV injections (Fig. 10B). CNO increased c-Fos expression in A1/C1 (Fig. 10, A and C). Quantification results of c-Fos-positive and triple-labeled (c-Fos/DBH/mCherry) cells in A1/C1 region in A1/C1AAV-hM3D rats in the four treatment groups indicate that CNO [F(3, 59) = 76.046, P < 0.001 between groups; P < 0.001, CNO + Sal vs. Sal + Sal; n = 12–16 sections per group from 3–4 rats], but not CCK (P > 0.5, Sal + CCK vs. Sal + Sal), increased c-Fos expression in CA neurons (Fig. 10C).

Fig. 10.

Effects of clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) and cholecystokinin (CCK) on ventrolateral medulla (VLM) c-Fos expression in A1/C1AAV-hM3D rats. AAV, adeno-associated virus; A1/C1, C1 and rostral A1 overlap region. 4 groups of female A1/C1AAV-hM3D rats were treated, as in Figs. 8 and 9, and brain tissue was collected for immunohistochemistry 90 min after the last injection. A: representative images of dopamine-β hydroxylase (DBH) (green), mCherry (blue), and c-Fos (magenta) triple staining in A1/C1. Asterisks in the photomicrographs indicate triple-labeled neurons. Bar = 50 µm. Sal, saline. B: quantified caudo-rostral distribution of DBH+, mCherry+, and DBH+/mCherry+ cells along VLM column. C1m, medial C1. C: cell counts of total c-Fos and triple-labeled (c-Fos/DBH/mCherry) cells in A1/C1 region. CNO increased c-Fos expression in transfected A1/C1 catecholamine neurons, but CCK did not. Data shown are means ± SE from 3–4 rats per treatment. n = 12–16 sections per group. ***P < 0.001 vs. Sal + Sal; ###P < 0.001 CNO + CCK vs. Sal + CCK (by post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls test after 1-way ANOVA).

DISCUSSION

The ability to achieve and maintain energy homeostasis requires the integration of both hunger and satiation signals to balance energy input with energy utilization. Satiation signals, such as the gut peptide CCK, play a major role in reduction of food intake when nutrients in the small intestine indicate an adequate level of alimentation (36, 37). However, the effectiveness of gastrointestinal satiation signals is modified by an animal’s present metabolic or nutritional state. Therefore, it is conceivable that a signal, such as CCK, which is released in response to fatty acids and protein in the small intestine (5), might inhibit food intake and prevent satisfaction of a specific macronutrient need, such as the need for glucose. Because it is the essential energy substrate of the brain, cells in the hindbrain closely monitor glucose availability and initiate robust counterregulatory responses, including robust increases in food intake, when reduced glucose availability threatens brain function (39, 41).

Catecholamine neurons in the VLM are essential for increased food intake and other responses to reduced glucose availability. Specifically, a subpopulation of CA neurons in the A1 and C1 cell groups exhibits increased c-Fos expression in response to reduced glucose availability (44). Furthermore, injection of glucose antimetabolites directly into the A1/C1 area triggers increased food intake (1, 25, 42), and destruction of CA neurons in those VLM cell groups reduces increased food intake in response to glucoprivation (26, 40, 47), as does silencing of Dbh and neuropeptide Y (Npy) gene expression (23). Therefore, although one cannot conclude that A1/C1 CA neurons are themselves glucose monitors, their response to glucoprivation is essential for defending the brain during glucoprivic emergency.

In contrast to A1/C1 neurons in the VLM, very few A2 neurons in the NTS increase c-Fos expression in response to systemic glucoprivation (44). Rather, a subpopulation of A2 neurons is strongly activated in response to systemic CCK injection, as well as in response to several other stimuli that reduce food intake (27). Furthermore, destruction of A2 neurons is associated with attenuation of CCK-induced reduction of food intake (33). Thus it is apparent that A2 CA neurons contribute to a behavioral response that potentially opposes increased food intake mediated by A1/C1 CA neurons. In other words, reduction of food intake by A2 neuron activation might interfere with increased food intake during glucoprivation. Therefore, a mechanism by which termination of food intake by gastrointestinal satiation signals, such as CCK, could be prevented or attenuated during ongoing glucoprivation would seem to be physiologically adaptive.

As expected from previous work (2), experiments reported here show that intraperitoneal injection of CCK reduced food intake in both male and female rats. Importantly, we also found that pretreatment of the rats with 2DG attenuated CCK-induced reduction of food intake. Interestingly, attenuation of CCK-induced reduction of food intake appeared to be somewhat more robust in females than in males. We cannot account for this apparent male/female difference. However, female rats are more sensitive to reduction of food intake by CCK during estrus, and estrogen itself reduces food intake and enhances the response to CCK (2). We and others have demonstrated previously that glucoprivation suppresses estrous cycles and disrupts reproductive function (3, 4, 13, 14). Therefore, it is conceivable that, in our experiment, suppression of estrus amplified attenuation of the effects of CCK in our female cohort. In any event, our results clearly indicate that systemic glucoprivation activates a mechanism to dampen satiation in response to CCK in both male and female rats.

Consistent with prior reports by others (27, 34), we observed in this study increased c-Fos expression in A2 CA neurons following intraperitoneal injection of CCK. Also consistent with our own previous reports (44), we found here that systemic 2DG induced c-Fos expression in A1/C1 CA neurons. However, when 2DG was administered before CCK, c-Fos expression by A2 neurons was markedly suppressed, whereas expression by A1/C1 neurons was sustained. Thus it appears that 2DG selectively increases A1/C1 neuronal activity while inhibiting the activity of A2 CA neurons. Destruction of A2 neurons by direct A2 injections of the immunotoxin anti-DBH-saporin has been reported to attenuate reduction of food intake by CCK (34). Hence, our observation of reduced CCK-induced c-Fos expression in A2 neurons of 2DG-treated rats is consistent with the interpretation that suppression of A2 neuron activation during glucoprivation leads to attenuated CCK-induced satiation.

There are several potential avenues by which glucose deficit might attenuate c-Fos expression by A2 CA neurons. It might be argued that A2 neurons are themselves sensitive to glucose and that glucose deficit directly inhibits their activity. Indeed, Roberts et al. (48) have reported that elevating extracellular glucose concentrations increases A2 neuron excitability by increasing glutamate release from vagal afferent inputs to these neurons. Therefore, it is conceivable that reduced glucose oxidation, as occurs following 2DG injection, might produce the opposite effect, reducing glutamate release in response to CCK, thereby attenuating A2 excitation and reduction of food intake. However, this mechanism does not appear to explain the inhibition of A2 neurons and attenuation of CCK-induced reduction of food intake following 2DG treatment. First, subdiaphragmatic vagotomy and capsaicin-induced lesion of vagal sensory neurons do not impair the feeding or adrenomedullary responses to 2DG (38, 45, 46). Second, systemic 2DG treatment is accompanied by sympathoadrenally mediated hyperglycemia (10, 51), such that extracellular glucose concentrations are elevated, not reduced, under our testing conditions (although glucose utilization is blocked). Consequently, one might expect levels of synaptic glutamate and A2 excitation to be increased, not decreased, according to this mechanism. Third, and even more compelling, is that, when we selectively activated VLM CA neurons using DREADD technology in this experiment, CCK-induced reduction of food intake was attenuated, and CCK-induced increase in c-Fos expression in A2 neurons was prevented. Importantly, these results indicate that activation of A1/C1 neurons attenuated reduction of food intake and A2 c-Fos expression, even in the absence of reduced glucose oxidation. Therefore, it seems clear that activation of A1/C1 neurons is critical for attenuation of A2 neuron activity even in the absence of glucoprivation, suggesting that A1/C1 activation inhibits A2 neurons via direct or multisynaptic neural connections between the two cell groups.

The circuitry by which A1/C1 activation inhibits A2 neuron activity and attenuates CCK-induced reduction of food intake is not known, and multiple possibilities exist. However, we favor the hypothesis that inhibition of A2 and other NTS neurons is mediated via direct innervation of NTS neurons by A1/C1 terminals. This hypothesis is consistent with the fact that the hypophagic effect of CCK and the orexigenic effect of glucoprivation are present even in rats decerebrated at the midbrain level (7, 9, 11). In addition, axonal CA processes extending from the VLM to the A2 region have been reported previously in our work (25) and by others (12, 52). Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that multisynaptic projections of A1/C1 neurons involving additional brain sites might contribute to inhibition of the action of CCK. For example, A1/C1 neurons densely innervate the hypothalamus, and hypothalamic projections densely innervate the middle and caudal NTS. Previous work has shown that activation of hypothalamic NPY neurons innervating the NTS, not only suppresses CCK-induced hypophagia, but also decreases Th phosphorylation in A2 (8). In this regard, it is intriguing that many A1/C1 neurons also coexpress NPY (49) and that DBH/NPY-coexpressing neurons are a VLM phenotype that appears to be required for glucoprivic feeding (23). Collectively, these findings raise the possibility that A1/C1 CA/NPY neurons may inhibit the A2 neuron response to CCK via monosynaptic projections that release NPY, whereas collaterals of these neurons or other A1/C1 neurons may project rostrally to activate hypothalamic NPY neurons with NTS projections that also contribute to A2 inhibition.

When examining CCK-induced c-Fos expression in the NTS, one is immediately struck by the fact that A2 neurons account for a relatively small percentage of c-Fos-expressing neurons. In this regard, it is interesting that 2DG treatment, not only resulted in attenuation of CCK-induced c-Fos expression in A2 CA neurons, but also attenuated c-Fos expression by the much more prevalent non-CA neurons in the NTS. This observation suggests that inhibitory effects of glucoprivation go beyond a selective effect on A2 neurons and may extend to neurons that mediate functions other than those ascribed to the NTS CA neurons. It is possible of course that activity of these non-CA c-Fos-expressing neurons is driven by CCK-induced activation of A2 CA neurons. An argument against this interpretation, however, is that Rinaman (34) reported that immunotoxin destruction of A2 neurons, which attenuated CCK-induced reduction of food intake, did not significantly reduce CCK-induced c-Fos expression in non-CA NTS neurons. Therefore, we think it is likely that glucoprivically driven inhibitory mechanisms that attenuate CCK-induced c-Fos expression in A2 neurons also act on non-CA NTS neurons. Additionally, we would argue that reduction of c-Fos in non-CA NTS neurons probably depends on glucoprivic activation of A1/C1 CA neurons because, when A1/C1 CA neurons are selectively stimulated via transfected DREADD activation, CCK-induced c-Fos expression is attenuated in non-CA NTS neurons, as well as in A2 neurons.

An additional point deserving expansion is that CCK treatment and increased A2 neuron c-Fos expression were not associated with reduced c-Fos expression in the VLM or attenuation of 2DG-evoked food intake. Therefore, it is apparent that, whatever the mechanism by which A1/C1 and A2 neurons interact, the relationship is not directly reciprocal, at least not during acute glucoprivation.

It is not immediately obvious why or how glucoprivic signals would be elicited during satiation. However, this life-threatening situation does occur in diabetics on insulin therapy in situations where insulin dose and glucose levels are inadvertently mismatched and blood glucose level rapidly falls, too often with harmful or lethal consequences (6, 28). Furthermore, A2 CA neurons, and other NTS neurons, contribute to suppression of food intake during illness and malaise (33), when reduced glucose availability may be comorbid. Therefore, mechanisms by which these neurons can be inhibited under such circumstances in the interest of glucose restoration would have significant survival value.

Finally, it is apparent that chronic imbalance or impaired interaction of activities in feeding and satiety circuits can lead to potentially large and sustained shifts in energy balance, including obesity. In this regard, previous reports suggest the involvement of both central and peripheral CA neurons in the development of obesity in rodents. Reduced feeding responses to glucose deficits have been reported in both diet-induced obese and monogenic obese rodent strains (15, 17, 29, 53, 54), and decreased activation of central CA neurons also has been reported in obese rat strains (17–20, 29). Rats in which hindbrain CA projections to the hypothalamus are retrogradely lesioned using the CA-selective immunotoxin, anti-DBH-saporin (31, 56), increase visceral adiposity, insulin resistance, and blood glucose. These changes occur even when rats are maintained on a chow diet (16), but they are accentuated by high-fat diet. On the basis of the present findings, these effects may be attributable to destruction or malfunction of CA neurons in both the dorsal and ventral medulla, emphasizing the importance of CA neuron interaction, not only on emergency control of food intake, but also on the overall control of metabolic homeostasis and body weight.

Perspectives and Significance

The glucoprivic control of food intake is a counterregulatory response to life-threatening reductions in glucose availability. As such, it is crucial that food consumption driven by glucoprivation is not terminated or reduced by satiation signals that terminate food intake during normal meals. Our results indicate that CA neurons subserving glucoprivic feeding activate circuitry that effectively suppresses hindbrain neurons that mediate satiation, such as those activated by the gut peptide CCK. The results highlight the adaptive importance of dominance and reciprocity among neural circuits responsible for control of food intake under differing physiological and environmental conditions.

GRANTS

This work was supported by PHS Grant DK114187 (to S. Ritter) and ADA 1-18-IBS-156 (to S. Ritter).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.-J.L. and S.R. conceived and designed research; A.-J.L. and Q.W. performed experiments; A.-J.L. and Q.W. analyzed data; A.-J.L. and S.R. interpreted results of experiments; A.-J.L. prepared figures; A.-J.L. and S.R. drafted manuscript; A.-J.L. and S.R. edited and revised manuscript; A.-J.L., Q.W., and S.R. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Robert C. Ritter for discussion and comments regarding this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrew SF, Dinh TT, Ritter S. Localized glucoprivation of hindbrain sites elicits corticosterone and glucagon secretion. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R1792–R1798, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00777.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asarian L, Geary N. Sex differences in the physiology of eating. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 305: R1215–R1267, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00446.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Briski KP, Alhamami HN, Alshamrani A, Mandal SK, Shakya M, Ibrahim MHH. Sex differences and role of estradiol in hypoglycemia-associated counter-regulation. Adv Exp Med Biol 1043: 359–383, 2017. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-70178-3_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briski KP, Nedungadi TP. Adaptation of feeding and counter-regulatory hormone responses to intermediate insulin-induced hypoglycaemia in the ovariectomised female rat: effects of oestradiol. J Neuroendocrinol 21: 578–585, 2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2009.01872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandra R, Liddle RA. Cholecystokinin. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 14: 63–67, 2007. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3280122850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cryer PE. Hypoglycemia-associated autonomic failure in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Adv Pharmacol 42: 620–622, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(08)60827-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darling RA, Ritter S. 2-Deoxy-d-glucose, but not mercaptoacetate, increases food intake in decerebrate rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 297: R382–R386, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90827.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de La Serre CB, Kim YJ, Moran TH, Bi S. Dorsomedial hypothalamic NPY affects cholecystokinin-induced satiety via modulation of brain stem catecholamine neuronal signaling. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 311: R930–R939, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00184.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flynn FW, Grill HJ. Insulin elicits ingestion in decerebrate rats. Science 221: 188–190, 1983. doi: 10.1126/science.6344221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galansino G, Parmeggiani A, Fromm DG, Bogartz LJ, Foa PP. Studies on 2-deoxy-d-glucose-induced hyperglycemia. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 116: 1005–1006, 1964. doi: 10.3181/00379727-116-29432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grill HJ, Smith GP. Cholecystokinin decreases sucrose intake in chronic decerebrate rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 254: R853–R856, 1988. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1988.254.6.R853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guyenet PG, Stornetta RL, Bochorishvili G, Depuy SD, Burke PG, Abbott SB. C1 neurons: the body’s EMTs. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 305: R187–R204, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00054.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.I’Anson H, Starer CA, Bonnema KR. Glucoprivic regulation of estrous cycles in the rat. Horm Behav 43: 388–393, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0018-506X(03)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.I’Anson H, Sundling LA, Roland SM, Ritter S. Immunotoxic destruction of distinct catecholaminergic neuron populations disrupts the reproductive response to glucoprivation in female rats. Endocrinology 144: 4325–4331, 2003. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikeda H, Nishikawa K, Matsuo T. Feeding responses of Zucker fatty rat to 2-deoxy- d-glucose, norepinephrine, and insulin. Am J Physio Endocrinol Metabl 239: E379–E384, 1980. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1980.239.5.E379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SJ, Jokiaho AJ, Sanchez-Watts G, Watts AG. Catecholaminergic projections into an interconnected forebrain network control the sensitivity of male rats to diet-induced obesity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 314: R811–R823, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00423.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levin BE. Reduced norepinephrine turnover in organs and brains of obesity-prone rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 268: R389–R394, 1995. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.268.2.R389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levin BE. Reduced paraventricular nucleus norepinephrine responsiveness in obesity-prone rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 270: R456–R461, 1996. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.2.R456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levin BE, Sullivan AC. Glucose-induced norepinephrine levels and obesity resistance. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 253: R475–R481, 1987. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1987.253.3.R475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levin BE, Triscari J, Sullivan AC. The effect of diet and chronic obesity on brain catecholamine turnover in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 24: 299–304, 1986. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(86)90354-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li AJ, Wang Q, Davis H, Wang R, Ritter S. Orexin-A enhances feeding in male rats by activating hindbrain catecholamine neurons. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 309: R358–R367, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00065.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li AJ, Wang Q, Dinh TT, Powers BR, Ritter S. Stimulation of feeding by three different glucose-sensing mechanisms requires hindbrain catecholamine neurons. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 306: R257–R264, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00451.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li AJ, Wang Q, Dinh TT, Ritter S. Simultaneous silencing of Npy and Dbh expression in hindbrain A1/C1 catecholamine cells suppresses glucoprivic feeding. J Neurosci 29: 280–287, 2009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4267-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li AJ, Wang Q, Elsarelli MM, Brown RL, Ritter S. Hindbrain catecholamine neurons activate orexin neurons during systemic glucoprivation in male rats. Endocrinology 156: 2807–2820, 2015. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li AJ, Wang Q, Ritter S. Selective pharmacogenetic activation of catecholamine subgroups in the ventrolateral medulla elicits key glucoregulatory responses. Endocrinology 159: 341–355, 2018. doi: 10.1210/en.2017-00630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madden CJ, Stocker SD, Sved AF. Attenuation of homeostatic responses to hypotension and glucoprivation after destruction of catecholaminergic rostral ventrolateral medulla neurons. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291: R751–R759, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00800.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maniscalco JW, Rinaman L. Overnight food deprivation markedly attenuates hindbrain noradrenergic, glucagon-like peptide-1, and hypothalamic neural responses to exogenous cholecystokinin in male rats. Physiol Behav 121: 35–42, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCrimmon RJ. Update in the CNS response to hypoglycemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97: 1–8, 2012. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pacak K, McCarty R, Palkovits M, Cizza G, Kopin IJ, Goldstein DS, Chrousos GP. Decreased central and peripheral catecholaminergic activation in obese Zucker rats. Endocrinology 136: 4360–4367, 1995. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.10.7664655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Picklo MJ, Wiley RG, Lappi DA, Robertson D. Noradrenergic lesioning with an anti-dopamine beta-hydroxylase immunotoxin. Brain Res 666: 195–200, 1994. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90772-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raybould HE, Gayton RJ, Dockray GJ. Mechanisms of action of peripherally administered cholecystokinin octapeptide on brain stem neurons in the rat. J Neurosci 8: 3018–3024, 1988. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-08-03018.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rinaman L. Hindbrain noradrenergic A2 neurons: diverse roles in autonomic, endocrine, cognitive, and behavioral functions. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 300: R222–R235, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00556.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rinaman L. Hindbrain noradrenergic lesions attenuate anorexia and alter central cFos expression in rats after gastric viscerosensory stimulation. J Neurosci 23: 10084–10092, 2003. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-31-10084.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rinaman L, Hoffman GE, Dohanics J, Le WW, Stricker EM, Verbalis JG. Cholecystokinin activates catecholaminergic neurons in the caudal medulla that innervate the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in rats. J Comp Neurol 360: 246–256, 1995. doi: 10.1002/cne.903600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ritter RC. Increased food intake and CCK receptor antagonists: beyond abdominal vagal afferents. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 286: R991–R993, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00116.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ritter RC, Covasa M, Matson CA. Cholecystokinin: proofs and prospects for involvement in control of food intake and body weight. Neuropeptides 33: 387–399, 1999. doi: 10.1054/npep.1999.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ritter RC, Ritter S, Ewart WR, Wingate DL. Capsaicin attenuates hindbrain neuron responses to circulating cholecystokinin. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 257: R1162–R1168, 1989. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.257.5.R1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ritter S. Monitoring and maintenance of brain glucose supply: importance of hindbrain catecholamine neurons in this multifaceted task. In: Appetite and Food Intake: Central Control, edited by Harris RBS. Boca Raton, FL: CRC, 2017. doi: 10.1201/9781315120171-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ritter S, Bugarith K, Dinh TT. Immunotoxic destruction of distinct catecholamine subgroups produces selective impairment of glucoregulatory responses and neuronal activation. J Comp Neurol 432: 197–216, 2001. doi: 10.1002/cne.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ritter S, Dinh TT, Li AJ. Hindbrain catecholamine neurons control multiple glucoregulatory responses. Physiol Behav 89: 490–500, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ritter S, Dinh TT, Zhang Y. Localization of hindbrain glucoreceptive sites controlling food intake and blood glucose. Brain Res 856: 37–47, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)02327-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ritter S, Li AJ, Wang Q, Dinh TT. Minireview: the value of looking backward: the essential role of the hindbrain in counterregulatory responses to glucose deficit. Endocrinology 152: 4019–4032, 2011. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ritter S, Llewellyn-Smith I, Dinh TT. Subgroups of hindbrain catecholamine neurons are selectively activated by 2-deoxy-d-glucose induced metabolic challenge. Brain Res 805: 41–54, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)00655-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ritter S, Taylor JS. Capsaicin abolishes lipoprivic but not glucoprivic feeding in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 256: R1232–R1239, 1989. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.256.6.R1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ritter S, Taylor JS. Vagal sensory neurons are required for lipoprivic but not glucoprivic feeding in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 258: R1395–R1401, 1990. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.258.6.R1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ritter S, Watts AG, Dinh TT, Sanchez-Watts G, Pedrow C. Immunotoxin lesion of hypothalamically projecting norepinephrine and epinephrine neurons differentially affects circadian and stressor-stimulated corticosterone secretion. Endocrinology 144: 1357–1367, 2003. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-221076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roberts BL, Zhu M, Zhao H, Dillon C, Appleyard SM. High glucose increases action potential firing of catecholamine neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract by increasing spontaneous glutamate inputs. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 313: R229–R239, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00413.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sawchenko PE, Swanson LW, Grzanna R, Howe PR, Bloom SR, Polak JM. Colocalization of neuropeptide Y immunoreactivity in brainstem catecholaminergic neurons that project to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. J Comp Neurol 241: 138–153, 1985. doi: 10.1002/cne.902410203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith GP, Gibbs J. Role of CCK in satiety and appetite control. Clin Neuropharmacol 15, Suppl 1: 476A, 1992. doi: 10.1097/00002826-199201001-00248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith GP, Root AW. Effect of feeding on hormonal responses to 2-deoxy-D-glucose in conscious monkeys. Endocrinology 85: 963–966, 1969. doi: 10.1210/endo-85-5-963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stornetta RL, Inglis MA, Viar KE, Guyenet PG. Afferent and efferent connections of C1 cells with spinal cord or hypothalamic projections in mice. Brain Struct Funct 221: 4027–4044, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00429-015-1143-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tkacs NC, Levin BE. Obesity-prone rats have preexisting defects in their counterregulatory response to insulin-induced hypoglycemia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287: R1110–R1115, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00312.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsujii S, Bray GA. Effects of glucose, 2-deoxyglucose, phlorizin, and insulin on food intake of lean and fatty rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 258: E476–E481, 1990. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1990.258.3.E476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Witten IB, Steinberg EE, Lee SY, Davidson TJ, Zalocusky KA, Brodsky M, Yizhar O, Cho SL, Gong S, Ramakrishnan C, Stuber GD, Tye KM, Janak PH, Deisseroth K. Recombinase-driver rat lines: tools, techniques, and optogenetic application to dopamine-mediated reinforcement. Neuron 72: 721–733, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wrenn CC, Picklo MJ, Lappi DA, Robertson D, Wiley RG. Central noradrenergic lesioning using anti-DBH-saporin: anatomical findings. Brain Res 740: 175–184, 1996. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(96)00855-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]