Abstract

BACKGROUND

The recurrence score based on the 21-gene breast cancer assay predicts chemotherapy benefit if it is high and a low risk of recurrence in the absence of chemotherapy if it is low; however, there is uncertainty about the benefit of chemotherapy for most patients, who have a midrange score.

METHODS

We performed a prospective trial involving 10,273 women with hormone-receptor–positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–negative, axillary node–negative breast cancer. Of the 9719 eligible patients with follow-up information, 6711 (69%) had a midrange recurrence score of 11 to 25 and were randomly assigned to receive either chemoendocrine therapy or endocrine therapy alone. The trial was designed to show noninferiority of endocrine therapy alone for invasive disease–free survival (defined as freedom from invasive disease recurrence, second primary cancer, or death).

RESULTS

Endocrine therapy was noninferior to chemoendocrine therapy in the analysis of invasive disease–free survival (hazard ratio for invasive disease recurrence, second primary cancer, or death [endocrine vs. chemoendocrine therapy], 1.08; 95% confidence interval, 0.94 to 1.24; P = 0.26). At 9 years, the two treatment groups had similar rates of invasive disease–free survival (83.3% in the endocrine-therapy group and 84.3% in the chemoendocrine-therapy group), freedom from disease recurrence at a distant site (94.5% and 95.0%) or at a distant or local–regional site (92.2% and 92.9%), and overall survival (93.9% and 93.8%). The chemotherapy benefit for invasive disease–free survival varied with the combination of recurrence score and age (P = 0.004), with some benefit of chemotherapy found in women 50 years of age or younger with a recurrence score of 16 to 25.

CONCLUSIONS

Adjuvant endocrine therapy and chemoendocrine therapy had similar efficacy in women with hormone-receptor–positive, HER2-negative, axillary node–negative breast cancer who had a midrange 21-gene recurrence score, although some benefit of chemotherapy was found in some women 50 years of age or younger. (Funded by the National Cancer Institute and others; TAILORx ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00310180.)

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women in the United States and worldwide.1 Hormone-receptor–positive, axillary node–negative disease accounts for approximately half of all cases of breast cancer in the United States.2 Adjuvant chemotherapy reduces the risk of recurrence,3–5 with effects that are proportionally greater in younger women but that are little affected by nodal status, grade, or the use of adjuvant endocrine therapy.6,7 These findings led a National Institutes of Health consensus panel to recommend adjuvant chemotherapy for most patients,8 a practice that has contributed to declining breast cancer mortality.9 However, the majority of patients may receive chemotherapy unnecessarily.

The 21-gene recurrence-score assay (Oncotype DX, Genomic Health) is one of several commercially available gene-expression assays that provide prognostic information in hormone-receptor–positive breast cancer.10,11 The recurrence score based on the 21-gene assay ranges from 0 to 100 and is predictive of chemotherapy benefit when it is high, whether a high score is defined as 31 or higher12,13 or 26 or higher12,14; when the recurrence score is low (0 to 10), it is prognostic for a very low rate of distant recurrence (2%) at 10 years that is not likely to be affected by adjuvant chemotherapy.12,14 Although expert panels recommend the use of the 21-gene assay,15,16 uncertainty remains as to whether chemotherapy is beneficial for the majority of patients, who have a mid-range recurrence score.

The Trial Assigning Individualized Options for Treatment (TAILORx) was designed to address these gaps in our knowledge by determining whether chemotherapy is beneficial for women with a mid-range recurrence score of 11 to 25. It was a prospective clinical trial, a type of trial that provides the highest level of evidence supporting the clinical usefulness of a biomarker.17 Another objective of the trial was to prospectively confirm that a low recurrence score of 0 to 10 is associated with a low rate of distant recurrence when patients are treated with endocrine therapy alone.18

Methods

Trial Oversight

We conducted a prospective clinical trial sponsored by the National Cancer Institute that was coordinated by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) and subsequently by the ECOG–American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ACRIN) Cancer Research Group, with other federally funded groups participating, including the Southwest Oncology Group, Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology, NRG Oncology, and Canadian Cancer Trials Group. Women who participated in the trial provided written informed consent, including a statement of willingness to have treatment assigned or randomly assigned on the basis of the recurrence-score results. An Oncotype DX recurrence-score assay was performed in a central laboratory (Genomic Health) on samples obtained from every woman who participated in the trial.10 Additional details are provided in the Supplementary Appendix and the protocol, both of which are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

The authors performed the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; the final submitted manuscript, which incorporated changes recommended by the coauthors and by Genomic Health, was reviewed and approved by all the authors, who vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and for adherence of the trial to the protocol. No one who is not an author contributed to the manuscript. Commercial support was not provided for the planning and execution of the trial but was provided by Genomic Health for the collection of follow-up information from the treating sites.

Trial Population, Treatment, and End Points

We enrolled women who were 18 to 75 years of age; had hormone-receptor–positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–negative, axillary node–negative breast cancer; and met National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for the recommendation or consideration of adjuvant chemotherapy (the full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria is provided in the Supplementary Appendix). On the basis of the 21-gene recurrence score, women were assigned to one of four treatment groups. Women with a recurrence score of 10 or lower were assigned to receive endocrine therapy only, and women with a score of 26 or higher were assigned to receive chemotherapy plus endocrine (chemoendocrine) therapy. Women with a midrange score of 11 to 25 underwent randomization and were assigned to receive either endocrine therapy alone or chemoendocrine therapy. Additional details are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

The standardized definitions for efficacy end points (STEEP) criteria were used for end-point definitions (Section 6B in the Supplementary Appendix).19 The primary end point was invasive disease–free survival, defined as freedom from invasive disease recurrence, second primary cancer, or death. Key secondary end points included freedom from recurrence of breast cancer at a distant site (which corresponds to the STEEP definition of distant recurrence–free interval), freedom from recurrence of breast cancer at a distant or local–regional site (which corresponds to the STEEP definition of recurrence-free interval), and overall survival. Full definitions of all the end points are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

Statistical Analysis

The overall sample size was driven by the need to include a sufficient number of patients with a recurrence score of 11 to 25 to test the noninferiority of endocrine therapy alone (the experimental group) to chemoendocrine therapy (the standard group) in this cohort of patients. Because of concern that nonadherence to the assigned treatment could make determination of an appropriate noninferiority margin problematic, the test of noninferiority used a null hypothesis of no difference, as when testing for superiority, but with a larger type I error (one-sided 10%) and smaller type II error (5%) than usual. In this approach, controlling the type II error is critical, so failure to reject equality provides evidence for a conclusion of noninferiority. A 5-year rate of invasive disease–free survival of 90% with chemoendocrine therapy and of 87% or less with endocrine therapy alone, which corresponds to a 32.2% higher risk of an invasive disease recurrence, second primary cancer, or death as a result of not administering chemotherapy (hazard ratio, 1.322), was prespecified as unacceptable.12,14

The primary analysis was a comparison according to the assigned treatment. Because of a rate of nonadherence (12%) that was larger than had originally been projected (5%), the sample size of the group that underwent randomization (i.e., women with a recurrence score of 11 to 25) was increased by 73% (relative to a design with 100% adherence, based on the Lachin–Foulkes correction),20 which resulted in a target sample size of 6517 eligible patients undergoing randomization. The analysis was also performed according to the actual treatment given in order to explore the effect of nonadherence. The final analysis took place on March 2, 2018, at which time the prespecified number of events required for full information (835 events) had occurred. The analysis methods are further described in Section 6B in the Supplementary Appendix.

Results

Characteristics of the Patients

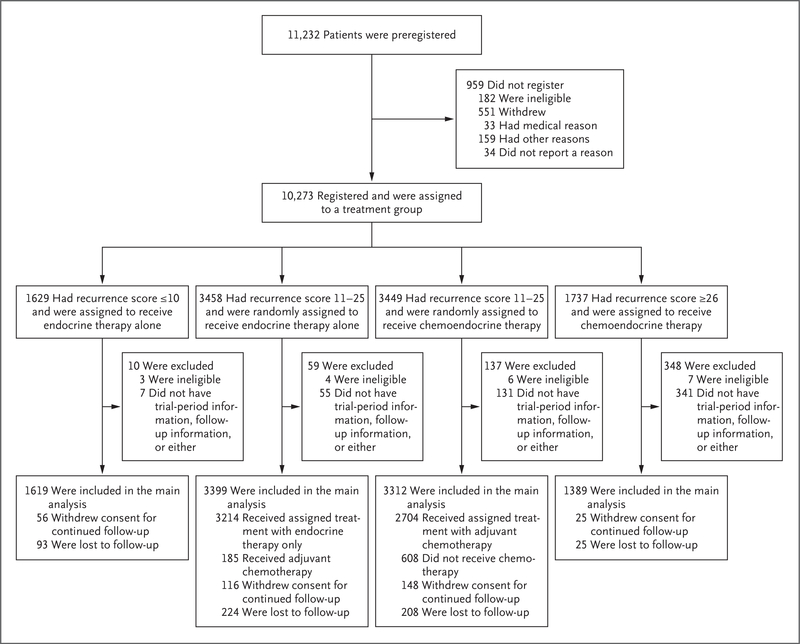

A total of 10,273 women were registered between April 7, 2006, and October 6, 2010, of whom 10,253 were eligible for participation. Among the 9719 eligible patients with follow-up information who were included in the main analysis set, 6711 (69%) had a recurrence score of 11 to 25, 1619 (17%) had a recurrence score of 10 or lower, and 1389 (14%) had a recurrence score of 26 or higher (Fig. 1). The median duration of follow-up in the cohort of patients with a recurrence score of 11 to 25 was 90 months for invasive disease–free survival and 96 months for overall survival. The characteristics of the trial population that was included in the main analysis are shown in Table 1, and in Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix.

Figure 1. Registration, Randomization, and Follow-up.

All the patients who met the eligibility criteria and provided written informed consent were preregistered; a primary tumor specimen was subsequently obtained and sent to the Genomic Health laboratory for the 21-gene assay. On receipt of the assay report and recurrence-score result by the treating physician, the enrolling site then assigned patients to a treatment group. If the recurrence score was 10 or lower, the patient was assigned to receive endocrine therapy alone. If the recurrence score was 26 or higher, the patient was assigned to receive chemoendocrine therapy. If the recurrence score was 11 to 25, the patient underwent randomization and was assigned to receive either endocrine therapy or chemoendocrine therapy. The stratification factors that were used in randomization were tumor size (≤2 cm vs. >2 cm), menopausal status (pre- vs. postmenopausal), planned chemotherapy (taxane-containing vs. not), planned radiation therapy (whole breast and no boost irradiation planned vs. whole breast and boost irradiation planned vs. partial breast irradiation planned vs. no planned radiation therapy for patients who had undergone a mastectomy), and recurrence-score group (11 to 15 vs. 16 to 20 vs. 21 to 25), which was added midway through the trial.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Patients in the Intention-to-Treat Population at Baseline.*

| Characteristic | Recurrence Score of ≤10 | Recurrence Score of 11–25 | Recurrence Score of ≥26 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endocrine Therapy (N = 1619) |

Endocrine Therapy (N = 3399) |

Chemoendocrine Therapy (N = 3312) |

Chemoendocrine Therapy (N = 1389) |

|

| Median age (range) — yr | 58 (25–75) | 55 (23–75) | 55 (25–75) | 56 (23–75) |

| Age ≤50 yr — no. (%) | 429 (26) | 1139 (34) | 1077 (33) | 409 (29) |

| Menopausal status — no. (%)† | ||||

| Premenopausal | 478 (30) | 1212 (36) | 1203 (36) | 407 (29) |

| Postmenopausal | 1141 (70) | 2187 (64) | 2109 (64) | 982 (71) |

| Tumor size in the largest dimension — cm‡ | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 1.5 (1.2–2.0) | 1.5 (1.2–2.0) | 1.5 (1.2–2.0) | 1.7 (1.3–2.3) |

| Mean | 1.74±0.76 | 1.71±0.81 | 1.71±0.77 | 1.88±0.99 |

| Histologic grade of tumor — no./total no. (%) | ||||

| Low | 530/1572 (34) | 959/3282 (29) | 934/3216 (29) | 89/1363 (7) |

| Intermediate | 931/1572 (59) | 1884/3282 (57) | 1837/3216 (57) | 590/1363 (43) |

| High | 111/1572 (7) | 439/3282 (13) | 445/3216 (14) | 681/1363 (50) |

| Estrogen-receptor expression — no. (%) | ||||

| Negative | 5 (<1) | 6 (<1) | 3 (<1) | 40 (3) |

| Positive | 1614 (>99) | 3393 (>99) | 3309 (>99) | 1349 (97) |

| Progesterone-receptor expression — no./total no. (%) | ||||

| Negative | 28/1583 (2) | 267/3339 (8) | 251/3240 (8) | 405/1353 (30) |

| Positive | 1555/1583 (98) | 3072/3339 (92) | 2989/3240 (92) | 948/1353 (70) |

| Clinical risk — no./total no. (%)§ | ||||

| Low | 1227/1572 (78) | 2440/3282 (74) | 2359/3214 (73) | 589/1359 (43) |

| High | 345/1572 (22) | 842/3282 (26) | 855/3214 (27) | 770/1359 (57) |

| Primary surgery — no. (%) | ||||

| Mastectomy | 516 (32) | 935 (28) | 917 (28) | 368 (26) |

| Breast conservation | 1103 (68) | 2464 (72) | 2395 (72) | 1021 (74) |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy — no. (%) | ||||

| Yes | 8 (0.5) | 185 (5.4) | 2704 (81.6) | 1300 (93.6) |

| No | 1611 (99.5) | 3214 (94.6) | 608 (18.4) | 89 (6.4) |

Plus–minus values are means ±SD. The characteristics were well balanced between the two randomly assigned groups (i.e., the two groups with a recurrence score of 11 to 25) for all the factors listed. The differences between the group with a recurrence score of 10 or lower and the combined randomly assigned groups were significant for age, menopausal status, histologic grade, progesterone receptor status, and surgical procedure (P<0.001 for all comparisons). The differences between the group with a recurrence score of 26 or higher and the combined randomly assigned groups were significant for the distributions of age (P = 0.003), menopausal status (P<0.001), tumor size (P<0.001), histologic grade (P<0.001), and progesterone receptor status (P<0.001).

A mong the 14 patients for whom menopausal status was not reported, those who were 50 years of age or younger were classified as premenopausal.

T here were 86 patients with a tumor size recorded as 0.5 cm or less and 20 patients with a tumor size greater than 5 cm. Information on tumor size was missing for 2 patients with a recurrence score of 11 to 25 in the chemoendocrine-therapy group and for 1 patient with a recurrence score of 26 or higher.

C linical risk was defined as in the MINDACT (Microarray in Node Negative Disease May Avoid Chemotherapy) trial (i.e., with low risk defined as low histologic grade and tumor size ≤3 cm, intermediate histologic grade and tumor size ≤2 cm, or high histologic grade and tumor size ≤1 cm; and with high risk defined as all other cases with known values for grade and tumor size).

Adjuvant Therapy in the Cohort with a Recurrence Score of 11 to 25

The median duration of endocrine therapy was 5.4 years, with similar distributions of durations in the two randomly assigned treatment groups, including approximately 35% rates of adjuvant endocrine therapy extending beyond 5 years (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). The most common chemotherapy regimens among the patients who were randomly assigned to and treated with chemotherapy were docetaxel–cyclophosphamide (56%) and anthracycline-containing regimens (36%). The endocrine therapy regimens among postmenopausal women most commonly included an aromatase inhibitor (91%); among premenopausal women, endocrine therapy regimens most commonly included either tamoxifen alone or tamoxifen followed by an aromatase inhibitor (78%), and suppression of ovarian function was used in 13% of premenopausal women (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). The rate of nonadherence to the assigned treatment was 11.8% overall, including 5.4% among patients who were randomly assigned to receive endocrine therapy alone and 18.4% among those who were randomly assigned to receive chemoendocrine therapy (Table 1). In the as-treated population, some of the differences in baseline characteristics between the treatment groups were significant (Table S3 in Supplementary Appendix).

Invasive Disease–free Survival and Other End Points in the Cohort with a Recurrence Score of 11 to 25

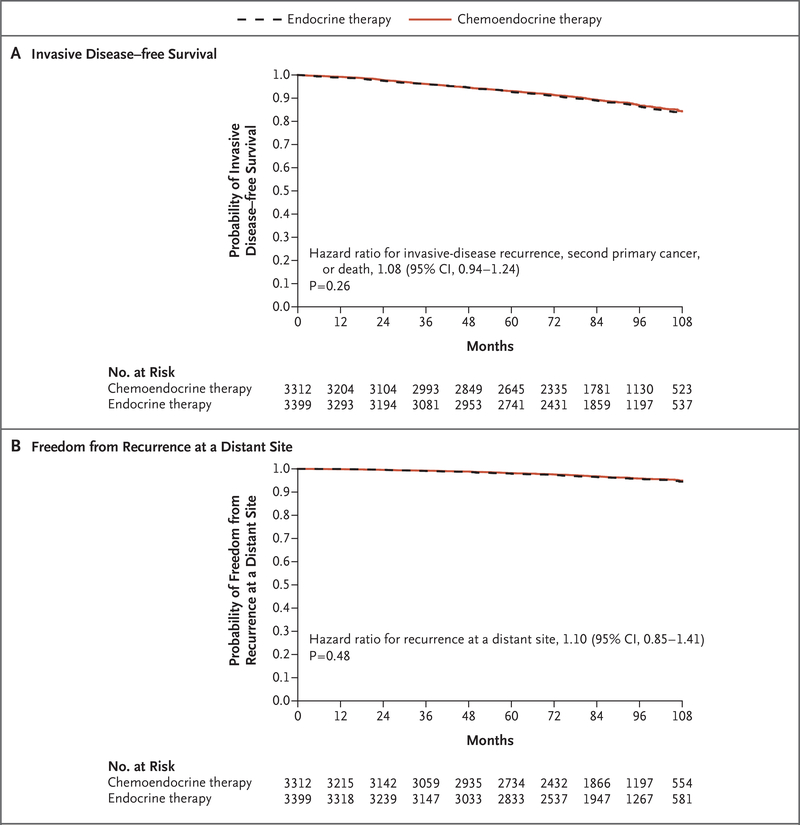

There had been 836 events of invasive disease recurrence, second primary cancer, or death (the components of invasive disease–free survival, the primary end point) in the two randomly as-signed treatment groups at the time of the final analysis, including 338 (40.4%) recurrences of breast cancer as the first event, of which 199 (23.8% of the total events) were distant recurrences (Tables S4 and S5 in the Supplementary Appendix). In the intention-to-treat population, endocrine therapy was noninferior to chemoendocrine therapy in the analysis of invasive disease–free survival (hazard ratio for invasive disease recurrence, second primary cancer, or death [endocrine vs. chemoendocrine therapy], 1.08; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.94 to 1.24; P = 0.26) (Fig. 2A). Endocrine therapy was likewise noninferior to chemoendocrine therapy in the analyses of other end points, including freedom from recurrence of breast cancer at a distant site (hazard ratio for recurrence, 1.10; P = 0.48) (Fig. 2B), freedom from recurrence of breast cancer at a distant or local–regional site (hazard ratio for recurrence, 1.11; P = 0.33), and overall survival (hazard ratio for death, 0.99; P = 0.89). Additional details regarding these end points are provided in Figure S2 and Section 6B in the Supplementary Appendix.

Figure 2. Clinical Outcomes among Patients with a Recurrence Score of 11 to 25.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of survival rates in the analysis according to the assigned treatment group are shown for the group that received endocrine therapy alone and the group that received chemoendocrine therapy in the intention- to-treat analysis of invasive disease–free survival (defined as freedom from invasive disease recurrence, second primary cancer, or death) and freedom from recurrence of breast cancer at a distant site. The hazard ratios are for the endocrine-therapy group versus the chemoendocrine-therapy group.

The results of the as-treated analyses were consistent with those of the intention-to-treat analyses for invasive disease–free survival (hazard ratio for invasive disease recurrence, second primary cancer, or death [endocrine vs. chemoendocrine therapy], 1.14; 95% CI, 0.99 to 1.31; P = 0.06), freedom from recurrence of breast cancer at a distant site (hazard ratio for recurrence, 1.03; P = 0.81), freedom from recurrence of breast cancer at a distant or local–regional site (hazard ratio for recurrence, 1.12; P = 0.28), and overall survival (hazard ratio for death, 0.97; P = 0.78) (Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). The estimated 9-year rates of invasive disease– free survival in the as-treated population were 83.1% for patients who received endocrine therapy alone and 84.7% for those who received chemoendocrine therapy. The outcomes were unlikely to have been affected by incomplete follow-up information (Section 6E in the Supplementary Appendix).

Survival Rates in All Recurrence-Score Cohorts and Treatment Groups

The estimated survival rates at 5 and 9 years for all treatment groups and end points are shown in Table 2. At 9 years in the intention-to-treat population, among patients with a recurrence score of 11 to 25, the rate of invasive disease– free survival was 83.3% in the endocrine-therapy group and 84.3% in the chemoendocrine-therapy group; the corresponding rates were 94.5% and 95.0% for freedom from recurrence of breast cancer at a distant site, 92.2% and 92.9% for freedom from recurrence of breast cancer at a distant or local–regional site, and 93.9% and 93.8% for overall survival. When all recurrencescore cohorts (≤10, 11 to 25, and ≥26) and treatment-group assignments were considered, there were significant differences in the rates of invasive disease–free survival, recurrence, and death (P<0.001), driven largely by the higher likelihood of having an event in the cohort with a recurrence score of 26 or higher (Fig. S4 in the Supplementary Appendix). Distant recurrence was associated with recurrence score as a continuous variable between 11 and 25, but there was no significant interaction between chemotherapy treatment and recurrence score in this range (Figs. S5 through S10 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Table 2.

Estimated Survival Rates According to Recurrence Score and Assigned Treatment in the Intention-to-Treat Population.*

| End Point and Treatment Group | Rate at 5 Yr | Rate at 9 Yr |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Invasive disease-free survival-†- | ||

| Score of ≤10, endocrine therapy | 94.0±0.6 | 84.0±1.3 |

| Score of 11–25, endocrine therapy | 92.8±0.5 | 83.3 ±0.9 |

| Score of 11–25, chemoendocrine therapy | 93.1±0.5 | 84.3±0.8 |

| Score of ≥26, chemoendocrine therapy | 87.6±1.0 | 75.7±2.2 |

| Freedom from recurrence of breast cancer at a distant site | ||

| Score of ≤ lO, endocrine therapy | 99.3±0.2 | 96.8±0.7 |

| Score of 11–25, endocrine therapy | 98.0±0.3 | 94.5±0.5 |

| Score of 11–25, chemoendocrine therapy | 98.2±0.2 | 95.0±0.5 |

| Score of ≥ 26, chemoendocrine therapy | 93.0±0.8 | 86.8±1.7 |

| Freedom from recurrence of breast cancer at a distant or local-regional site | ||

| Score of ≤ 10, endocrine therapy | 98.8±0.3 | 95.0±0.8 |

| Score of 11–25, endocrine therapy | 96.9±0.3 | 92.2±0.6 |

| Score of 11–25, chemoendocrine therapy | 97.0±0.3 | 92.9±0.6 |

| Score of ≥ 26, chemoendocrine therapy | 91.0±0.8 | 84.8±1.7 |

| Overall survival | ||

| Score of ≤ lO, endocrine therapy | 98.0±0.4 | 93.7±0.8 |

| Score of 11–25, endocrine therapy | 98.0±0.2 | 93.9±0.5 |

| Score of 11–25, chemoendocrine therapy | 98.1±0.2 | 93.8±0.5 |

| Score of ≥ 26, chemoendocrine therapy | 95.9±0.6 | 89.3±1.4 |

Plus–minus values are Kaplan–Meier estimates ±SE.

Invasive disease–free survival was defined as freedom from invasive disease recurrence, second primary cancer, or death.

Interactions According to Subgroup in the Cohorts with a Recurrence Score of 11 to 25

We performed exploratory analyses to determine whether any subgroups might have derived some benefit from chemotherapy in the intention-totreat population, with a focus on covariates that were prognostic or associated with greater benefit from chemotherapy, such as younger age (Section 6F and Fig. S11 in the Supplementary Appendix).6 There were no significant interactions between chemotherapy treatment and most of the prognostic covariates examined, including recurrence-score category (either 11 to 15 vs. 16 to 20 vs. 21 to 25, or 11 to 17 vs. 18 to 25), tumor size (≤2 cm vs. >2 cm), histologic grade (low vs. intermediate vs. high), clinical risk category (high vs. low), and menopausal status (pre- vs. postmenopausal). There were significant interactions between chemotherapy treatment and age (≤50 vs. 51 to 65 vs. >65 years) for invasive disease–free survival (P = 0.03) and for freedom from recurrence of breast cancer at a distant or local–regional site (P = 0.02) but not at a distant site (P = 0.12). The effect of treatment also varied significantly over the six combinations of menopausal status and recurrence-score category (11 to 15 vs. 15 to 20 vs. 21 to 25) (P = 0.02) and over the nine combinations of age and recurrence-score category (P = 0.004) for invasive disease–free survival (Figs. S12 and S13 in the Supplementary Appendix) but not for freedom of recurrence of breast cancer at a distant site or distant or local–regional site. In women 50 years of age or younger, chemotherapy was associated with a lower rate of distant recurrence than endocrine therapy if the recurrence score was 16 to 20 (percentage-point difference, 0.8 at 5 years and 1.6 at 9 years) or 21 to 25 (percentage-point difference, 3.2 at 5 years and 6.5 at 9 years), although the rates of overall survival were similar (Table 3). Conversely, in the 40% of women 50 years of age or younger who had a recurrence score of 0 to 15, the rate of distant recurrence was approximately 2% at 9 years among those who had been assigned (either randomly or nonrandomly) to endocrine therapy alone.

Table 3.

Estimated Survival Rates According to Recurrence Score and Assigned Treatment among Women 50 Years of Age or Younger in the Intention-to-Treat Population.*

| End Point and Treatment Group | Rate at 5 Yr | Rate at 9 Yr |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Invasive disease-free survival† | ||

| Score of ≤ 1O. endocrine therapy | 95.1±1.1 | 87.4±2.0 |

| Score of 11–15. endocrine therapy | 95.1±1.1 | 85.7±2.2 |

| Score of 11–15. chemoendocrine therapy | 94.3±1.3 | 89.2±1.9 |

| Score of 16–20. endocrine therapy | 92.0±1.3 | 80.6±2.5 |

| Score of 16–20. chemoendocrine therapy | 94.7±1.1 | 89.6±1.7 |

| Score of 21–25. endocrine therapy | 86.3±2.3 | 79.2±3.3 |

| Score of 21–25. chemoendocrine therapy | 92.1±1.8 | 85.5±3.0 |

| Score of ≥ 26. chemoendocrine therapy | 86.4±1.9 | 80.3±2.9 |

| Freedom from recurrence of breast cancer at a distant site | ||

| Score of ≤ 1O. endocrine therapy | 99.7±0.3 | 98.5±0.8 |

| Score of 11–15. endocrine therapy | 98.8±0.6 | 97.2±1.0 |

| Score of 11–15. chemoendocrine therapy | 98.5±0.7 | 98.0±0.8 |

| Score of 16–20. endocrine therapy | 98.1±0.7 | 93.6±1.4 |

| Score of 16–20. chemoendocrine therapy | 98.9±0.5 | 95.2±1.3 |

| Score of 21–25. endocrine therapy | 93.2±1.7 | 86 9±2.9 |

| Score of 21–25. chemoendocrine therapy | 96.4±1.2 | 93.4±2.3 |

| Score of ≥ 26. chemoendocrine therapy | 91.1±1.6 | 88 7±2.1 |

| Freedom from recurrence of breast cancer at a distant or local-regional site | ||

| Score of≤1O. endocrine therapy | 98.4±0.6 | 95.4±1.3 |

| Score of 11–15. endocrine therapy | 97.5±0.8 | 93.3±1.6 |

| Score of 11–15. chemoendocrine therapy | 97.2±0.9 | 94.4±1.5 |

| Score of 16–20. endocrine therapy | 95.7±1.0 | 89.6±1.9 |

| Score of 16–20. chemoendocrine therapy | 97.2±0.8 | 93.0±1.5 |

| Score of 21–25. endocrine therapy | 89.8±2.0 | 82.0±3.2 |

| Score of 21–25. chemoendocrine therapy | 94.2±1.6 | 90.7±2.5 |

| Score of ≥ 26. chemoendocrine therapy | 88.6±1.8 | 86.1±2.2 |

| Overall survival | ||

| Score of≤1O. endocrine therapy | 100.0 | 98.6±0.9 |

| Score of 11–15. endocrine therapy | 99.3±0.4 | 96.8±1.0 |

| Score of 11–15. chemoendocrine therapy | 98.9±0.6 | 97.5±0.9 |

| Score of 16–20. endocrine therapy | 98.6±0.6 | 95.8±1.2 |

| Score of 16–20. chemoendocrine therapy | 99.8±0.2 | 96.1±1.2 |

| Score of 21–25. endocrine therapy | 98.2±0.9 | 92.7±2.0 |

| Score of 21–25. chemoendocrine therapy | 98.3±0.8 | 93.9±1.9 |

| Score of ≥ 26. chemoendocrine therapy | 95.6±1.1 | 92.4±1.9 |

Plus–minus values are Kaplan–Meier estimates ±SE.

Invasive disease–free survival was defined as freedom from invasive disease recurrence, second primary cancer, or death.

Discussion

In this prospective, randomized trial, we found that among 6711 women with hormone-receptor– positive, HER2-negative, axillary node–negative breast cancer and a midrange recurrence score of 11 to 25 on the 21-gene assay, endocrine therapy was not inferior to chemoendocrine therapy, which provides evidence that adjuvant chemotherapy was not beneficial in these patients. This finding contrasts those of previous biomarker validation studies that were performed retrospectively with the use of archival tumor specimens, in which a substantial benefit for the prevention of distant recurrence has been found for the combination of chemotherapy and endocrine therapy in patients with a recurrence score of 26 or higher.12,13 The 9-year rate of distant recurrence in women with a recurrence score of 11 to 25 in our trial was approximately 5%, irrespective of chemotherapy use, a finding consistent with that predicted from the original report showing a significant treatment interaction between chemotherapy benefit and a recurrence score of 26 or higher.14 Updated results for patients with a low recurrence score of 10 or less, who were previously reported as having a 1% distant recurrence rate at 5 years in our trial,18 now indicate a 9-year rate of distant recurrence of approximately 3%.

Population-based studies have shown a recurrence-score distribution similar to that observed in this prospective trial, along with no apparent benefit from chemotherapy in the recurrence-score range of 11 to 25 and a significant association between recurrence score and recurrence or 5-year breast cancer–specific mortality, which indicates the generalizability of our findings to clinical practice.21,22 Although the rate of nonadherence to the assigned treatment was 12% overall, the sample size was adjusted to compensate for this, and the as-treated analysis produced results similar to those of the intention-to-treat analysis. The rate of nonadherence was similar to those in previous trials evaluating breast conservation or high-dose chemotherapy.23,24 Only 24% of first events included in the primary end point (invasive disease recurrence, second primary cancer, or death) were distant recurrences, the type of recurrence that is most influenced by adjuvant chemotherapy,7 which also has some effect in reducing other events, such as local–regional recurrence or contralateral breast cancer.25,26

A total of 40% of women who were 50 years of age or younger had a recurrence score of 15 or lower, which was associated with a low rate of recurrence with endocrine therapy alone. Exploratory analyses indicated that chemotherapy was associated with some benefit for women 50 years of age or younger who had a recurrence score of 16 to 25 (a range of scores that was found in 46% of women in this age group). A greater treatment effect from adjuvant chemotherapy has been noted in younger women,7 which may be at least partly explained by an antiestrogenic effect associated with premature menopause induced by chemotherapy.27 We did not collect data on chemotherapy-induced menopause. It remains unclear whether similar benefits could be achieved with ovarian suppression plus an aromatase inhibitor instead of chemo-therapy.28,29

The MINDACT (Microarray in Node Negative Disease May Avoid Chemotherapy) trial was also a prospective trial integrating a gene-expression assay (with 70 genes) and randomized assignment of chemotherapy.30 The primary end point in the trial focused on 644 patients with high clinical risk (48% node-positive, 8% HER2-positive) and low genomic risk who were assigned to receive no chemotherapy, and the prespecified prognostic end point of a 5-year rate of distant metastasis–free survival of more than 92% in this group of patients was met. Evidence-based guidelines recommend that the use of the assay be considered in cases of hormone-receptor–positive, HER2-negative breast cancer and high clinical risk but not low clinical risk as defined in that trial.31 When the same clinical risk definitions were applied in our trial, 73.9% of the patients were at low clinical risk and 26.1% were at high clinical risk in the randomized treatment groups (Table 1), and we found no evidence suggesting a chemotherapy benefit in either risk group.

On the basis of previous information regarding the clinical validity and usefulness of the 21-gene assay, the use of adjuvant chemotherapy has declined substantially in hormone-receptor– positive, HER2-negative, axillary node–negative breast cancer.32 The results of our trial suggest that the 21-gene assay may identify up to 85% of women with early breast cancer who can be spared adjuvant chemotherapy, especially those who are older than 50 years of age and have a recurrence score of 25 or lower, as well as women 50 years of age or younger with a recurrence score of 15 or lower. Ongoing clinical trials are obtaining additional information on the clinical usefulness of the 21-gene assay in women with hormone-receptor–positive breast cancer and positive axillary nodes33 and evaluating the clinical usefulness of the 50-gene assay in this context.34

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the United States government.

Supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (award numbers CA180820, CA180794, CA189828, CA180790, CA180795, CA180799, CA180801, CA180816, CA180821, CA180838, CA180822, CA180844, CA180847, CA180857, CA180864, CA189867, CA180868, CA189869, CA180888, CA189808, CA189859, CA189804, CA190140, and CA180863), the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute (grants 015469 and 021039), the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, the Komen Foundation, the Breast Cancer Research Stamp issued by the U.S. Postal Service, and Genomic Health.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org. Authors who reported serving as paid consultants for Genomic Health within 36 months before publication include Drs. Goetz and Kaklamani; Dr. Paik reports holding a patent issued and licensed to Genomic Health, with all rights transferred to the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) Foundation.

We thank Sheila Taube, Ph.D., and JoAnne Zujewski, M.D., National Cancer Institute, for their support of the trial at its inception and development; the staff at the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG)–American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ACRIN) Operations Office in Boston and the Cancer Trials Support Unit for their efforts; Una Hopkins, R.N., D.N.P., for serving as the study liaison for the trial; the late Robert L. Comis, M.D., former chair of ECOG and cochair of ECOG-ACRIN, for his prescient leadership in supporting biomarker-directed clinical trials; the thousands of women who participated in the trial; the leadership of the National Breast Cancer Coalition for endorsing the trial; and Mary Lou Smith, J.D., M.B.A., for her work as a patient advocate for breast cancer clinical research.

Footnotes

A full list of the investigators in this trial is provided in the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org.

Contributor Information

Joseph A. Sparano, Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY

Robert J. Gray, Dana–Farber Cancer Institute, Boston.

Della F. Makower, Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY.

Kathleen I. Pritchard, Sunnybrook Research Institute, Toronto.

Kathy S. Albain, Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine, Maywood, and Northwestern University, Chicago both in Illinois.

Daniel F. Hayes, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Charles E. Geyer, Jr, Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine and the Massey Cancer Center, Richmond.

Elizabeth C. Dees, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and Duke University Medical Center, Durham both in North Carolina

Matthew P. Goetz, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL

John A. Olson, Jr., University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and Duke University Medical Center, Durham both in North Carolina.

Tracy Lively, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD.

Sunil S. Badve, Indiana University School of Medicine and Indiana University Hospital Indianapolis

Thomas J. Saphner, Vince Lombardi Cancer Clinic, Two Rivers and Fox Valley Hematology and Oncology, Appleton both in Wisconsin

Lynne I. Wagner, Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine, Maywood, and Northwestern University, Chicago both in Illinois

Timothy J. Whelan, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON both in Canada.

Matthew J. Ellis, Washington University, St. Louis

Soonmyung Paik, National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Pathology Office and University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh;

William C. Wood, Emory University, Atlanta

Peter M. Ravdin, University of Texas, San Antonio

Maccon M. Keane, Cancer Trials Ireland, Dublin.

Henry L. Gomez Moreno, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplasicas, Lima, Peru

Pavan S. Reddy, Cancer Center of Kansas, Wichita

Timothy F. Goggins, Vince Lombardi Cancer Clinic, Two Rivers and Fox Valley Hematology and Oncology, Appleton both in Wisconsin.

Ingrid A. Mayer, Vanderbilt University, Nashville

Adam M. Brufsky, National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Pathology Office and University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh;

Deborah L. Toppmeyer, Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey, New Brunswick

Virginia G. Kaklamani, Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine, Maywood, and Northwestern University, Chicago both in Illinois.

Jeffrey L. Berenberg, University of Hawaii Cancer Center, Honolulu

Jeffrey Abrams, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD

George W. Sledge, Jr., Indiana University School of Medicine and Indiana University Hospital Indianapolis

References

- 1.Jemal A, Center MM, DeSantis C, Ward EM. Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010; 19: 1893–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howlader N, Altekruse SF, Li CI, et al. US incidence of breast cancer subtypes defined by joint hormone receptor and HER2 status. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014; 106(5):dju055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mansour EG, Gray R, Shatila AH, et al. Efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in high-risk node-negative breast cancer: an intergroup study. N Engl J Med 1989;320: 485–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mansour EG, Gray R, Shatila AH, et al. Survival advantage of adjuvant chemotherapy in high-risk node-negative breast cancer: ten-year analysis — an intergroup study. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 3486–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher B, Dignam J, Wolmark N, et al. Tamoxifen and chemotherapy for lymph node-negative, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1997;89: 1673–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 2005;365: 1687–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Comparisons between different polychemotherapy regimens for early breast cancer: meta-analyses of long-term outcome among 100,000 women in 123 randomised trials. Lancet 2012; 379: 432–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abrams JS. Adjuvant therapy for breast cancer — results from the USA Consensus Conference. Breast Cancer 2001;8:298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munoz D, Near AM, van Ravesteyn NT, et al. Effects of screening and systemic adjuvant therapy on ER-specific US breast cancer mortality. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014; 106(11):dju289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paik S, Shak S, Tang G, et al. A multi-gene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2817–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwa M, Makris A, Esteva FJ. Clinical utility of gene-expression signatures in early stage breast cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017;14:595–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paik S, Tang G, Shak S, et al. Gene expression and benefit of chemotherapy in women with node-negative, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:3726–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albain KS, Barlow WE, Shak S, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of the 21-gene recurrence score assay in postmenopausal women with node-positive, oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer on chemotherapy: a retrospective analysis of a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:55–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sparano JA, Paik S. Development of the 21-gene assay and its application in clinical practice and clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:721–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlson RW, Brown E, Burstein HJ, et al. NCCN Task Force report: adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2006;4:Suppl 1:S1–S26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris L, Fritsche H, Mennel R, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2007 update of recommendations for the use of tumor markers in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:5287–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simon RM, Paik S, Hayes DF. Use of archived specimens in evaluation of prognostic and predictive biomarkers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009;101:1446–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sparano JA, Gray RJ, Makower DF, et al. Prospective validation of a 21-gene expression assay in breast cancer. N Engl Med 2015;373:2005–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hudis CA, Barlow WE, Costantino JP, et al. Proposal for standardized definitions for efficacy end points in adjuvant breast cancer trials: the STEEP system. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:2127–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lachin JM, Foulkes MA. Evaluation of sample size and power for analyses of survival with allowance for nonuniform patient entry, losses to follow-up, non-compliance, and stratification. Biometrics 1986;42:507–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petkov VI, Miller DP, Howlader N, et al. Breast-cancer-specific mortality in patients treated based on the 21-gene assay: a SEER population-based study. NPJ Breast Cancer 2016;2:16017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stemmer SM, Steiner M, Rizel S, et al. Clinical outcomes in patients with nodenegative breast cancer treated based on the recurrence score results: evidence from a large prospectively designed registry. NPJ Breast Cancer 2017;3:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher B, Bauer M, Margolese R, et al. Five-year results of a randomized clinical trial comparing total mastectomy and segmental mastectomy with or without radiation in the treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 1985;312:665–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tallman MS, Gray R, Robert NJ, et al. Conventional adjuvant chemotherapy with or without high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation in high-risk breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2003;349:17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mamounas EP, Tang G, Liu Q. The importance of systemic therapy in minimizing local recurrence after breast-conserving surgery: the NSABP experience. J Surg Oncol 2014;110:45–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bertelsen L, Bernstein L, Olsen JH, et al. Effect of systemic adjuvant treatment on risk for contralateral breast cancer in the Women’s Environment, Cancer and Radiation Epidemiology Study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swain SM, Jeong J-H, Geyer CE Jr, et al. Longer therapy, iatrogenic amenorrhea, and survival in early breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;362:2053–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Francis PA, Regan MM, Fleming GF, et al. Adjuvant ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;372:436–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fleming G, Francis PA, Lang I, et al. Randomized comparison of adjuvant tamoxifen (T) plus ovarian function suppression (OFS) versus tamoxifen in premenopausal women with hormone receptor positive (HR+) early breast cancer (BC): update of the SOFT trial. Cancer Res 2017;78:Suppl: GS4–03 abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cardoso F, van’t Veer LJ, Bogaerts J, et al. 70-Gene signature as an aid to treatment decisions in early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:717–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krop I, Ismaila N, Andre F, et al. Use of biomarkers to guide decisions on adjuvant systemic therapy for women with early-stage invasive breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline focused update. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:2838–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurian AW, Bondarenko I, Jagsi R, et al. Recent trends in chemotherapy use and oncologists’ treatment recommendations for early-stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2018;110:493–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong WB, Ramsey SD, Barlow WE, Garrison LP Jr, Veenstra DL. The value of comparative effectiveness research: projected return on investment of the Rx- PONDER trial (SWOG S1007). Contemp Clin Trials 2012;33:1117–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bartlett J, Canney P, Campbell A, et al. Selecting breast cancer patients for chemotherapy: the opening of the UK OPTIMA trial. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2013;25:109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.