Abstract

Shortcomings of approaches to classifying psychopathology based on expert consensus have given rise to contemporary efforts to classify psychopathology quantitatively. In this paper, we review progress in achieving a quantitative and empirical classification of psychopathology. A substantial empirical literature indicates that psychopathology is generally more dimensional than categorical. When the discreteness versus continuity of psychopathology is treated as a research question, as opposed to being decided as a matter of tradition, the evidence clearly supports the hypothesis of continuity. In addition, a related body of literature shows how psychopathology dimensions can be arranged in a hierarchy, ranging from very broad “spectrum level” dimensions, to specific and narrow clusters of symptoms. In this way, a quantitative approach solves the “problem of comorbidity” by explicitly modeling patterns of co‐occurrence among signs and symptoms within a detailed and variegated hierarchy of dimensional concepts with direct clinical utility. Indeed, extensive evidence pertaining to the dimensional and hierarchical structure of psychopathology has led to the formation of the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) Consortium. This is a group of 70 investigators working together to study empirical classification of psychopathology. In this paper, we describe the aims and current foci of the HiTOP Consortium. These aims pertain to continued research on the empirical organization of psychopathology; the connection between personality and psychopathology; the utility of empirically based psychopathology constructs in both research and the clinic; and the development of novel and comprehensive models and corresponding assessment instruments for psychopathology constructs derived from an empirical approach.

Keywords: Psychopathology, mental disorder, personality, nosology, classification, dimensions, clinical utility, Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology, ICD, DSM, RDoC

Throughout the history of psychiatric classification, two approaches have been taken to delineating the nature of specific psychopathologies1. A first one might be termed authoritative: experts gather under the auspices of official bodies, and delineate classificatory rubrics through group discussions and associated political processes. This approach characterizes official nosologies, such as the DSM and the ICD. It also often characterizes official efforts to influence the constructs and conceptualizations that frame the perspectives of funding bodies. For example, the US National Institute of Mental Health's Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) effort involved the delineation of constructs that were shaped and organized by panels of experts2.

A second approach might be termed empirical. In this approach, data are gathered on psychopathological building blocks. These data are then analyzed to address specific research questions. For example, does a specific list of symptoms delineate a single psychopathological entity or, by contrast, do those symptoms delineate multiple entities? This approach is sometimes characterized as more “bottom up”, compared with the more “top down” approach of official nosologies. This is because the approach generally starts with basic observations and works to assemble them into classificatory rubrics, rather than working from a set of assumed rubrics to fill in the detailed features of those rubrics.

Obviously, these approaches, although distinguishable, are not entirely separable. Authoritative classification approaches have relied on specific types of empiricism as part of their construction process, and an empirical approach begins with the expertise needed to assemble and assess specific psychopathological building blocks (e.g., signs and symptoms). Nevertheless, it is clear that authoritative approaches tend to weigh putative expertise, disciplinary background, and tradition heavily.

To pick a specific example, the construction of DSM‐5 was primarily a psychiatric endeavor, by virtue of the disciplinary background of most participants and by the nature of the body that served to generate and publish the manual (i.e., the American Psychiatric Association). As part of the DSM‐5 construction process, field trials were undertaken to evaluate the reliability of specific mental disorder diagnoses. Interestingly, these trials produced a wide range of reliability estimates, encompassing evidence of weak reliability for many common diagnostic entities, such as major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder3. In spite of questionable reliability, these constructs remain enshrined in DSM‐5 and constitute the official “diagnostic criteria and codes” in Section II of the manual.

Because of these types of sociopolitical dynamics (e.g., asserting the existence of specific psychopathological categories ex cathedra despite questionable evidence), authoritative approaches have come under increased scrutiny. Many types and sources of scrutiny coalesce around the scientific disappointments that have accompanied research on diagnostic categories. Simply put, the categories of official nosologies have not provided compelling guidance in the search for etiology and pathophysiology. As a result, the empirical approach to classification is now attracting great interest as a potential alternative to diagnosis by presumed authority and fiat.

In the present paper, we summarize some key types of evidence that have emerged from the burgeoning literature on empirical approaches to psychiatric classification. We focus in particular on: a) evidence pertaining to the continuous versus discrete nature of psychopathological constructs; b) evidence for the hierarchical organizational structure of psychopathological constructs; and c) evidence for specific empirically‐based organizational rubrics.

In our discussion of specific empirically‐based organizational rubrics, we focus on a consortium that has recently formed to organize and catalyze empirical research on psychopathology, the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) Consortium. As we discuss the work of this consortium, we consider major issues that confront an empirical approach to classification, as it continues to evolve. These issues correspond to existing workgroups in the consortium, and hence, we use the foci of those workgroups to organize our discussion.

Specifically, those workgroups and our discussion are organized around: a) continued research on the organization of broad spectra of psychopathology; b) the connection between personality and psychopathology; c) the utility of constructs derived from an empirical approach (e.g., the ability of these constructs to organize research on pathophysiology); d) translation of empirical research into clinical practice; e) the development of novel and comprehensive models and corresponding assessment instruments for constructs derived from an empirical approach.

THE CONTINUOUS VS. DISCRETE NATURE OF PSYCHOPATHOLOGICAL PHENOTYPES

Perhaps the most fundamental difference between current authoritative psychiatric nosologies and empirical research on psychopathology classification pertains to the continuous vs. discrete nature of constructs. Through tradition and putative authority, authoritative nosologies claim that psychopathologies are organized into discrete diagnostic entities. By contrast, an empirical approach to classification treats the discrete vs. continuous nature of psychopathology as a research question4. When treated as a research question, evidence points toward the generally continuous nature of psychopathological variation.

Taxometric evidence

Taxometric methods originated in the writings of P. Meehl, and evaluate the possibility that a set of symptoms (or other indicators of psychopathology) delineate a discrete group. These methods have been used extensively, such that there is now a considerable literature on their application. This literature was summarized quantitatively by Haslam et al5. Based on findings from 177 articles, encompassing data from over half a million research participants, psychopathological variation was found to be continuous as opposed to discrete, i.e., there was little consistent evidence for taxa.

Subsequent taxometric reports in diverse areas also tend to reveal greater evidence for continuity as opposed to discreteness. For example, recent taxometric investigations have provided evidence for the continuity of subclinical paranoia and paranoid delusions6, adolescent substance use7, and depression in youth8. Occasional evidence for potential discreteness is also reported9, 10, emphasizing the importance of ongoing quantitative summaries of this literature.

Psychometric studies of putative taxa are important to establish their validity, such as evaluating stability over time. That is, longitudinal stability of putative taxon membership is also a key means of evaluating a taxonic conjecture, inasmuch as psychopathology taxon membership is conceptualized as a stable property over modest time intervals (e.g., weeks or months). For example, Waller and Ross11 reported evidence that pathological dissociation might be taxonic. Watson12 investigated this putative taxon and found that taxon membership was not stable across a two‐month interval, whereas continuous indicators of dissociation were strongly stable.

In sum, extensive evidence suggests that the likelihood of identifying discrete psychopathology groups empirically via taxometrics is not high. By contrast, the taxometrics literature generally points to the continuity of psychopathological variation, emphasizing the greater relative utility and empirical accuracy of continuous as opposed to discrete conceptualizations of psychopathology.

Model‐based evidence

Taxometric procedures originally evolved to some extent outside of the mainstream statistical literature. Within the more mainstream literature, approaches have emerged that rely on the ability to fit models to raw data on symptom patterns, and to use all of the extensive information in those data to adjudicate between continuous, discrete and hybrid accounts of psychopathology constructs. These approaches are often termed model‐based, because they rely on formal statistical models that describe the distributional form of the constructs that underlie symptoms.

Generally, direct comparison of continuous and discrete models via these approaches have indicated that psychopathological constructs tend to be more continuous than discrete13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19. Nevertheless, there are also occasional suggestions of potentially meaningful discontinuities, particularly as conceptualized in models that have both continuous and discrete features20, 21, 22.

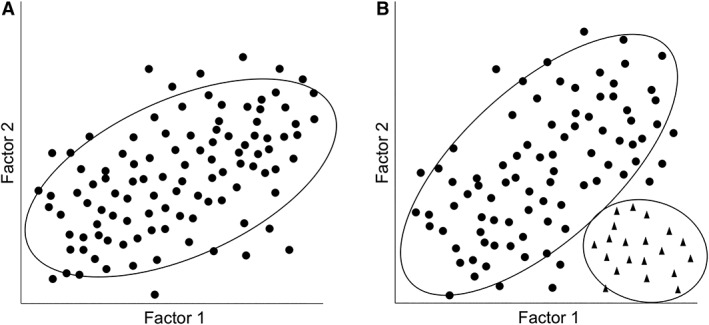

For example, Figure 1 depicts a bivariate distribution similar to the results found in Forbes et al20. Panel A shows a sample where the two continuous factors are moderately correlated for all participants (i.e., all participants are drawn from a single underlying population, akin to the results Forbes et al found for the relationships among depression, anxiety and sexual dysfunctions for women). In contrast, Panel B shows a discontinuity in the data where two groups emerge: the majority of the sample has a strong positive correlation between the factors, but a subgroup of the sample has a weak negative correlation (i.e., participants are drawn from two distinct underlying populations, akin to the results Forbes et al found for men). Generally speaking, the development and comparison of models of latent structure remains a profitable and active area of inquiry, because this approach provides an empirical means of directly comparing and potentially integrating categorical and continuous conceptions of psychopathology23, 24.

Figure 1.

Illustration of hypothetical data compatible with fully continuous and partially discrete models of psychopathological variation. In Panel A, the data points are generally well captured by positing a single group, in which Factor 1 and Factor 2 are positively correlated. In Panel B, the data are better captured by positing two groups, one in which Factor 1 and Factor 2 are positively correlated (the circles), and a second smaller group in which Factor 1 and Factor 2 are weakly negatively correlated (the triangles).

However, similar to the situation with potential taxa, the discontinuities need to map truly discrete features of psychopathology (i.e., be reliable and replicable) to be meaningful. Consider, for example, how these requirements played out in a project reported by Eaton et al25. In this project, model based clustering was used to discern potential discrete personality disorder groups. This approach works well in a variety of scientific areas, when there are actual discontinuities to be detected (e.g., character recognition, tissue segmentation; see http://www.stat.washington.edu/mclust/). Eaton et al therefore applied this approach to a large data set (N=8,690) containing samples from four distinguishable populations (clinical, college, community and military participants). Potential discontinuities observed in each sample were not replicated across samples. By contrast, a dimensional model of the data was readily replicated across the samples. The authors interpreted these findings as suggesting that personality disorder features did not delineate replicable discontinuities, but instead, represented replicable continuities.

In sum, efforts to identify potential discontinuities on the basis of data are important endeavors, because they continue to expose dimensional conjectures to risky and direct tests. Nevertheless, similar to what has been learned from decades of taxometric research, the bulk of the existing model‐based evidence points to the dimensional nature of psychopathology.

Implications of dimensionality

Evidence to date, stemming from multiple empirical approaches, generally points to the continuity of psychopathological phenotypes. As a result, contemporary empirical approaches often conceptualize psychopathological constructs as dimensional, which has a number of implications. For example, it highlights the extent to which the categories of official nosologies are out of sync with data on the dimensional nature of psychopathology. This disparity is well recognized, and also, very challenging to navigate in a sociopolitical sense, because so many professional endeavors are firmly intertwined with the category labels enshrined in official nosologies26. In this paper, we do not detail specific events that have recently played out surrounding this challenge (e.g., pertaining to DSM‐5 and ICD‐11), but we do note that the challenge needs to be faced head‐on if official nosologies aim to be founded on solid empirical footing27.

We also note here another key implication of the dimensional nature of psychopathology, pertaining to relations between manifest psychopathology and its correlates. Specifically, the continuous nature of psychopathological variation provides a framework for understanding the form and nature of relations between cumulative risk factors, manifest psychopathology, and important outcomes28. Consider distal and putatively etiologic correlates, such as specific genetic and environmental risk factors. Continuous phenotypic variation suggests (but does not prove) that the relevant etiologic elements are likely multiple and numerous. Multiple relatively independent causes give rise to continuous phenotypic variation, as is observed with many human phenotypes, e.g. height29, 30. Similar to physical phenotypes, psychopathological phenotypes are likely the result of specific mixtures of numerous etiologic influences, with both proportions of influence and the resulting phenotypes varying continuously across persons31.

In sum, the concept of continuous variation among persons in etiologic mixture dovetails well with the observation of continuous phenotypic variation, and provides generative strategies for etiologic research. For example, persons with similar phenotypic values may have arrived at those values in distinct ways. Hence, profitable research strategies might focus less on “cases” and “controls”, and more on developing multivariate models of the joint distribution of etiologic (e.g., genomic polymorphisms) and continuous phenotypic observations in larger samples32.

Turning from causes to consequences, thinking about continuous variation and the public health consequences of psychopathology may also provide novel insights. Although psychopathology appears to be a continuous predictor, the nature of its relationship with public health consequences could take numerous forms, at least in theory. Thinking about this situation may provide insights that go well beyond an artificial “cases vs. controls” research strategy. For example, continuous psychopathology may very well show a monotonically‐increasing and generally linear relationship with impairment33, 34. Or, the relationship could have non‐linear features, e.g., accelerating in a certain region of continuous psychopathological variation22, 35.

Again, the key point here is that these possibilities are empirically tractable when psychopathology is modeled dimensionally, yet obscured through the artificial dichotomization that characterizes traditional psychiatric nosologies. Somewhat ironically, continuous measurement of psychopathology is essential to evaluating the possibility that there are meaningful thresholds, beyond which social and occupational dysfunction becomes increasingly more likely.

HIERARCHICAL ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE OF PSYCHOPATHOLOGICAL DIMENSIONS

One perennial issue in developing an empirically‐derived and dimensional approach to psychopathology pertains to general organizing principles. In traditional authoritative and categorical approaches to classification, this issue is tacitly addressed by the organizational structure of the classificatory effort. For example, the specific workgroup structure of the DSM‐5 construction effort implies an organization of psychopathology into rubrics that reflect the workgroup names, and that structure trickles down into the chapter structure of the printed classification.

Might organizational issues also be addressed empirically? Evidence described in the foregoing section stems from asking if a specific set of signs and symptoms delineates a specific dimension as opposed to a specific category. This evidence suggests that psychopathology is generally dimensional in nature, but how many dimensions are there, and how are these dimensions organized?

Work in this area has generally progressed from asking “what is the correct number of dimensions” to realizing that this question is somewhat specious, because individual difference dimensions (e.g., individual differences in the propensity to experience specific psychopathological signs and symptoms) are organized hierarchically. This understanding has been important in resolving a variety of classificatory conundrums, typically focused in areas where two or more psychopathological constructs contain variation that is both shared and unique.

Perhaps the most classic example pertains to anxiety and depression36. The tendency to experience pathological anxiety is clearly correlated with the tendency to experience pathological depression, yet these tendencies are also distinguishable. Categorical nosologies have difficulty managing these situations, because they tend to lead to proposals of “mixed categories” (e.g., a category of mixed anxiety and depression that is putatively distinguishable from a category of anxiety only and a category of depression only). If anxiety and depression are more dimensional than categorical, as well as correlated but not perfectly correlated, then most patients will not fit neatly into any of these three categories. This tends to lead to difficulties making categorical diagnostic determinations in practice. For example, a mixed anxiety‐depression category was proposed for DSM‐5, but did not emerge from the field trials as a reliable diagnosis37.

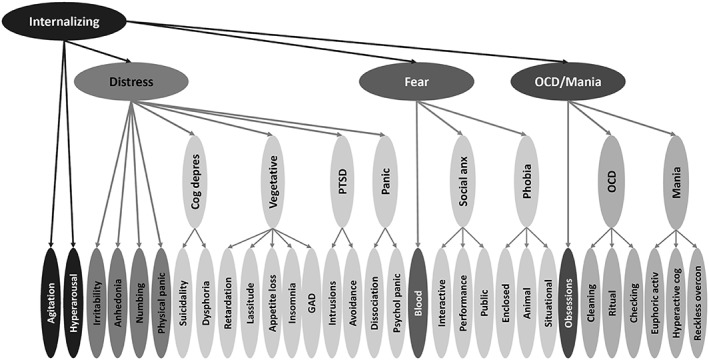

The key to resolving these sorts of dilemmas is to realize that the evidence is most readily compatible with conceptualizing anxiety and depressive phenomena (as well as other dimensional phenomena) as encompassed by hierarchically organized dimensions. To illustrate this point concretely, consider a model developed by Waszczuk et al38, portrayed in Figure 2. This model, which is based on extensive data, shows how specific anxiety and depressive phenomena are associated with continuous degrees of similarity and distinctiveness, across four hierarchically arranged levels of generality vs. specificity. These hierarchical levels reflect the overall degree of empirical co‐occurrence vs. distinctiveness of the phenomena encompassed by the model. Concepts higher in the figure are more general and broad, whereas concepts lower in the figure are more specific and narrow.

Figure 2.

Illustration of an empirically based model of the internalizing spectrum. Constructs higher in the figure are broader and more general, whereas constructs lower in the figure are narrower and more specific (adapted from Waszczuk et al38). PTSD – post‐traumatic stress disorder, Social anx – social anxiety, OCD – obsessive‐compulsive disorder, GAD – generalized anxiety disorder, Cog depress – cognitive depression, Psychol panic – psychological panic, Euphoric activ – euphoric activation, Hyperactive cog – hyperactive cognition, Reckless overcon – reckless overconfidence.

At the most general level, diverse anxious and depressive phenomena are understood to be aspects of a general domain of internalizing psychopathology. However, as is apparent in both data and clinical work in this area, although anxious and depressive phenomena are indeed correlated, they are not perfectly correlated and, therefore, are distinguishable from one another. Hence, one level down, distinctions emerge among distress, fear, and obsessive‐compulsive (OCD)/manic phenomena. Note that this is a more refined and empirically based understanding when compared with DSM chapter headings, because, rather than being delineated by individual committees, this model uses data to encompass the breadth of phenomena that fall into the internalizing domain.

Accordingly, at a third level of specificity, key distinctions emerge among aspects of the three distress, fear and OCD/mania domains. OCD and mania are distinguishable at this level, as are specific aspects of these broader domains, such as the cognitive and vegetative aspects of depression. Indeed, considered across levels, these patterns have fundamental conceptual and clinical implications. For example, these patterns highlight the connection between OCD and manic phenomena, as well as their distinctiveness from distress and fear. This may be traceable to the connection that OCD and manic phenomena share with the broad spectrum of psychosis, and how this psychotic aspect both drives OCD and mania together, and separates them from other parts of the internalizing spectrum39. Finally, at the lowest level of the hierarchy lie specific symptom clusters, such as checking, lassitude, and so on.

In sum, the Figure 2 model solves the problem of “comorbidity between anxiety and depression” by using data to model the empirical organization of emotional disorder phenomena. Rather than forcing these phenomena into committee‐derived categories, they are modeled as they are in nature. As a result, “complex presentations” (e.g., persons who present with a mix of emotional disorder symptoms) are handled because these presentations can be readily represented by a specific profile of problems. This understanding then drives case conceptualization in the clinic40, and strategies for identifying key correlates (e.g., neural response) in the laboratory41.

Evidence for dimensional hierarchies can be found throughout psychopathology, and is not limited to anxiety and mood phenomena. Indeed, this evidence is sufficiently comprehensive that it has formed the basis for a consortium of researchers interested in empirical approaches to psychopathology, the HiTOP Consortium42. We turn now to describe the main features of the model that frames HiTOP, as well as the issues and topics that are currently being pursued within HiTOP.

EVIDENCE FOR SPECIFIC EMPIRICALLY‐BASED ORGANIZATIONAL RUBRICS

Given evidence that psychopathological phenotypes are dimensional in nature, and that these dimensions are organized hierarchically, what types of classificatory rubrics emerge in an empirical hierarchy of psychopathological dimensions? The HiTOP Consortium focuses on these and related issues.

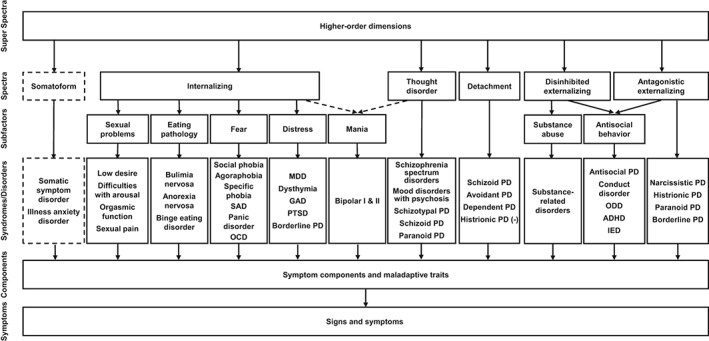

The consortium currently consists of 70 investigators with backgrounds in diverse disciplines (e.g., psychology, psychiatry and philosophy), and this group has proposed a working dimensional and hierarchical model, derived from the literature on empirical psychopathology classification. This model is portrayed in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Working Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) consortium model. Constructs higher in the figure are broader and more general, whereas constructs lower in the figure are narrower and more specific (adapted from Kotov et al43). SAD – separation anxiety disorder, OCD – obsessive‐compulsive disorder, MDD – major depressive disorder, GAD – generalized anxiety disorder, PTSD – post‐traumatic stress disorder, PD – personality disorder, ODD – oppositional defiant disorder, ADHD – attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder, IED – intermittent explosive disorder.

The model is not intended to be the final word on empirical psychopathology classification. Indeed, the purpose of articulating this model was to provide a first draft that might frame continued inquiry, and thereby move discourse away from tendentious debates about various reified classification schemes. Nevertheless, the model does summarize a substantial literature, reviewed by Kotov et al43 as background for the hierarchical structure portrayed in Figure 3. Here, we will briefly outline the main features of the model, and then turn to discuss various workgroups within the consortium, which formed to address major issues in the field of empirical psychopathology classification.

As portrayed in Figure 3, the working HiTOP model is hierarchical in nature. Constructs higher in the figure summarize the tendencies for constructs lower in the figure to co‐occur in specific patterns. For example, consistent with Figure 2, the broad internalizing spectrum in Figure 3 encompasses more specific “sub‐spectra” such as the fear, distress and mania spectra. However, the model in Figure 3 was intended to synthesize the entire available literature on empirical classification and, as a result, its scope and breath is considerably larger than the Figure 2 model, which was designed specifically to delineate the internalizing spectrum.

Consider spectra adjacent to internalizing in the Figure 3 model. In addition to the internalizing spectrum, five other major empirical divisions of psychopathology are portrayed on the same level. Currently, the model posits major spectra labeled somatoform, thought disorder, detachment, disinhibited externalizing, and antagonistic externalizing. These concepts are reminiscent of, but not necessarily coterminous with, similar constructs in existing authoritative nosologies such as the DSM and ICD. For example, the current HiTOP model posits the existence of a somatoform spectrum that is separable from other major psychopathology spectra, and roughly similar in content to somatoform diagnoses in DSM‐5.

While the evidence for the somatoform spectrum is limited (as indicated by the dashed lines in Figure 3), this spectrum illustrates a general principle of empirical classification research. Phenomena that are not explicitly considered within a specific scope can be considered by expanding that scope accordingly. For example, somatoform constructs are not as heavily researched as other phenomena on the level of major spectra (e.g., internalizing and externalizing), and this provides an important opportunity for targeted and focused research44. Specifically, how closely do somatoform concepts align with other spectrum concepts, and what are the shared and distinguishing features of these concepts?

Rather than being handled in relatively insular literatures aligned with traditional classificatory rubrics, the HiTOP framework provides novel opportunities for more targeted and synthetic research on key empirical questions in classification. For example, how do somatoform phenomena covary with other phenomena in the HiTOP model? Are they better understood as an aspect of the broader internalizing spectrum, or are they sufficiently distinguished to form their own separate spectrum? If they have both shared and distinctive features, are intervention efforts more effective if focused on the shared features, or on the distinctive features? Such questions are posed and framed by thinking about somatoform phenomena in the context of psychopathology broadly, in ways that go well beyond a more piecemeal approach to parsing and conceptualizing psychopathology.

Similar to the situation with the somatoform spectrum, other constructs on the spectra level have varying volumes of associated literature, as well as being associated with specific arrangements portrayed in Figure 3. Recognizing these hypothesized arrangements provides generative avenues for novel research. Consider examples pertinent to each of the spectra in Figure 3. The thought disorder spectrum reflects the close empirical connections among psychotic phenomena that have historically been divided between more dispositional vs. more acute manifestations45, 46. This empirical distinction thereby becomes a topic for continuing empirical inquiry, and not an issue presumably settled by the unfortunate tradition of studying personality and clinical disorders in separate literatures47.

For example, the ICD‐11 proposal for personality disorders does not encompass a psychoticism domain, not because psychotic phenomena are outside of a comprehensive multivariate model of maladaptive personality, but rather because tradition places them in a different chapter within the ICD (and in contrast with the DSM, which assigns schizotypal disorder primarily to the personality disorders chapter, with a secondary assignment as part of the schizophrenia spectrum in the schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders chapter48). Likewise, antisocial personality disorder is assigned both to the personality disorder and the disruptive, impulse control and conduct disorders chapter. In the HiTOP approach, these sorts of fundamental issues become topics for empirical inquiry.

Similar issues are addressed by the two externalizing spectra portrayed in Figure 3. The current HiTOP model reflects the distinction between the two major aspects of externalization: antagonism (hurting others intentionally) and disinhibition (acting on impulse or in response to a current stimulus, with little consideration of consequences49). As such, it also reflects the ways in which these separable aspects are both present in traditional DSM diagnostic criteria sets. For example, DSM‐IV defined antisocial personality disorder, and similar DSM diagnostic concepts, represent a mix of antagonistic and disinhibited features50. The HiTOP model posits that separating these empirically‐based features may result in greater clarity regarding the classification of specific phenomena. For example, the model posits a closer connection between substance related disorders and disinhibition than between substance related disorders and antagonism. In addition, the model ties together closely aligned externalizing phenomena that are spread throughout DSM chapters and various literatures (e.g., child and adult manifestations of basic antagonistic tendencies, as well as phenomena such as intermittent explosive disorder).

Finally, consider the detachment (avoidance of socioemotional engagement) spectrum portrayed in Figure 3. Similar to somatoform phenomena, detachment phenomena have not been as heavily studied as other major spectra. In addition, similar to externalizing phenomena, detachment has been somewhat diffused throughout traditional nosologies, being captured within the features of a number of traditional personality disorders. The HiTOP model recognizes the evidence that detachment appears to be a major spectrum of adult psychopathology. As such, the model underlines the importance of understanding the public health significance of pathological socioemotional avoidance, as opposed to spreading this feature across constructs that have attracted relatively less clinical and research attention, compared with more florid manifestations of psychopathology.

Below the level of spectra in Figure 3 are levels encompassing subfactors and disorders. These concepts reflect a mix of more traditional and more empirically based rubrics. The presence of traditional diagnostic labels on Figure 3 is not to reify these concepts (many of which are highly heterogeneous, and therefore in need of empirical refinement), but rather, to provide a cross walk to traditional and familiar DSM‐style labels. As the model implies, the heterogeneity of these phenomena provides important opportunities for clarifying investigations.

Consider, for example, borderline personality disorder (BPD), which is listed below both the distress and antagonistic externalizing rubrics in the working HiTOP model. BPD encompasses a number of distinguishable elements and, as a result, tends to be associated with diverse psychopathology spectra51, 52. Indeed, the majority of the variance in BPD is shared with other forms of psychopathology (rather than being unique to it), emphasizing the importance of reducing BPD and similar constructs to their constituent elements, and working to reconstitute those elements in an empirical manner.

This type of refinement endeavor has been clarifying in specific literatures where it has been undertaken. For example, empirical efforts underlie large segments of the DSM‐5 alternative personality disorder model, and frame the essential structure of the ICD‐11 personality disorder approach, in ways that go fundamentally beyond traditional personality disorder rubrics. Thinking broadly, the HITOP model underlines the general utility of this type of empirical refinement endeavor, pursued with regard to psychopathology writ large.

THE HIERARCHICAL TAXONOMY OF PSYCHOPATHOLOGY CONSORTIUM (HiTOP) AS A FRAMEWORK FOR CONTINUED PROGRESS

HiTOP is intended to serve as a consortium to organize and stimulate progress on an empirical approach to classifying psychopathology. To facilitate this progress, the consortium is organized into a series of workgroups. The workgroup rubrics do not exhaust all the important issues that might be addressed in empirical psychopathology classification. Nevertheless, they do reflect themes that have emerged to organize current HiTOP efforts. Importantly, membership in HiTOP is not closed, and there are many opportunities to get involved in various aspects of the endeavor42.

Higher‐order dimensions workgroup

A significant challenge posed by the model in Figure 3 is its breadth. As implied by the distinction between Figure 2 and Figure 3 (i.e., the distinction between detail and breadth), many empirical classification efforts have been understandably focused on specific spectra of psychopathology. Above the level of internalizing in Figure 3 is the “super spectra” level, which is currently open, largely because relations among various psychopathology spectra remains an active area of empirical inquiry. For example, there has been recent interest in a general psychopathology dimension, akin to the general dimension found in the cognitive abilities literature53, 54.

Although there is little doubt that variation in psychopathology spectra is generally correlated (i.e., multi‐morbidity is encountered frequently), important issues remain to be addressed in contemplating the organizational structure of psychopathology above the spectrum level. For example, for a hierarchical construct to be “truly general”, its influence on constructs below it in a hierarchy should be relatively uniform. Contrary to this conceptualization, the magnitude of influence of the general psychopathology factor on specific constructs below it has not been necessarily uniform. For example, Caspi et al53 modeled a general factor of psychopathology and found it to be associated primarily with psychotic phenomena. Lahey et al54 also modeled a general factor of psychopathology, but found it to be associated primarily with phenomena that fall generally into the distress subdomain of internalizing (albeit they did not specifically study psychotic phenomena).

These distinctions between various representations of the general factor of psychopathology may relate to important technical issues surrounding the meaning and interpretation of a general factor. For example, technical issues have arisen in the literature on individual differences in cognitive test performance. In that literature, it is now understood that ways of modeling general factors (e.g., using a bifactor versus a hierarchical structural model), and ways of comparing models (e.g., based on fit indices), differ in subtle but important ways from many traditional approaches to structural modeling55, 56, 57. These issues have yet to be addressed thoroughly in the psychopathology literature, and are therefore a focus of current activity in the higher order workgroup.

Furthermore, we note that the breadth of psychopathology in various studies of potential general factors is less than the breadth of psychopathology encompassed in Figure 3. How to efficiently assess (and thereby have the opportunity to model) the entire breadth of psychopathology covered by Figure 3 presents an important – and daunting – challenge. In addition, the current model does not encompass the neurodevelopmental spectrum (e.g., intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorders, learning disorders), the neurocognitive disorders, and the paraphilic disorders.

Measures development workgroup

Many existing measures assess different aspects of the HiTOP scheme (see https://psychology.unt.edu/hitop). Nevertheless, as of this writing, a comprehensive measure designed to assess the entire breadth of psychopathology covered in Figure 3 does not exist. The measures development workgroup in HiTOP was created to address this issue directly. The related but distinct goals of the measurement workgroup are to: a) simultaneously develop measures for all proposed symptom dimensions and personality traits encompassed by HiTOP in the service of empirically refining the model through psychometrically rigorous structural work, and b) based on this work, developing clinical useful tools designed to permit researchers and mental health practitioners to reliably, validly and efficiently assess all components of the HiTOP model.

In the service of building clinically useful tools, which is an important translational goal of HiTOP more generally, a number of fundamental measurement issues arise. We list just a few here to give a feel for some of the challenges ahead. For example, if the conceptualization of psychopathology is dimensional, should skip‐outs (or other adaptive techniques) be employed to enhance the efficiency of assessment (akin to skip‐outs designed on a rational basis to enhance the efficiency of traditional category assessment via structured interview)? Traditionally, dimensional approaches to psychopathology have been more closely associated with questionnaire as opposed to interview assessment strategies (because of the close intellectual and historical connections between psychometrics and questionnaire development). How can interview approaches – often favored in clinical research contexts – be developed that reflect more dimensional conceptualizations (e.g., the Structured Interview for the Five Factor Model58 and the Interview for Mood and Anxiety Symptoms38)? In addition, assessment of traditional categories via interview is typically modularized; only specific modules are used in many assessments, consistent with the constructs targeted. Can or should dimensional assessment be similarly modularized? Is this even possible or desirable, given the evidence portrayed in Figure 3, that all varieties of psychopathology are positively correlated? Finally, how can transient symptom manifestations and chronic maladaptive trait characteristics be seamlessly integrated within a single instrument?

Normal personality workgroup

The resemblance between the model portrayed in Figure 3 and well‐established models of human personality variation, particularly the prominent Five Factor Model59, is clear. This resemblance is not accidental, but rather reflects the ways in which personality forms the empirical psychological infrastructure for the development of specific varieties of psychopathological symptoms59. Nevertheless, a number of interesting and important issues arise in recognizing the intertwined nature of variation in personality and psychopathology.

For example, as noted earlier, the model in Figure 3 reflects empirical connections based on extant literature that was framed by constructs that vary in their associated presumed periodicity. By tradition, DSM frames some disorders as more episodic (e.g., mood disorders), and other disorders are more dispositional (e.g., personality disorders). Stepping back from this act of historical fiat, what in actuality are the distinctions between more dispositional personality constructs, and more acute symptom constructs? Both seem important in comprehensive case conceptualization but, practically and empirically, what strategies might help to parse similarities and differences, yet also unify them in a more comprehensive model? These are the sorts of issues that fall into the bailiwick of the HiTOP normal personality workgroup.

Utility workgroup

Implicit in articulating the type of model portrayed in Figure 3 is the idea that this model has utility, i.e., that it can do some useful work in the world that will help to propel research and clinical practice. The role of the utility workgroup is to realize this potential explicitly. A number of examples might be mentioned, but those that seem particularly salient involve connections of empirical psychopathological phenotypes with neural mechanisms and genomic variants, given contemporary funding priorities. The biomedical research enterprise (e.g., the basic paradigm framing funding bodies such as the US National Institutes of Health) prioritizes the role of fundamental biological processes in addressing issues in public health. This prioritization reflects the success of this paradigm in addressing many health problems during the 20th century. Accordingly, there is substantial interest and financial investment in understanding the neural bases of manifest psychopathology.

HiTOP constructs have a key role to play in furthering this endeavor. For example, the RDoC initiative has sometimes been criticized for providing limited guidance in conceptualizing clinical psychopathology per se. This may in some ways reflect a disjunction between what RDoC has aimed to achieve, and what investigators are seeking. To our reading, RDoC aimed to focus attention and effort on more fundamental neurobiological constructs as promising topics for research. The intent was not necessarily to re‐conceptualize phenotypic psychopathology60. In this way, HiTOP represents a necessary and desirable counterpart to RDoC. The interface between the neurobiological constructs of RDoC and the more phenotypic constructs of HiTOP represents a key means of connecting structure and process in understanding psychopathology.

Clinical translation workgroup

Although traditional nosologies are framed by their category labels, dimensional approaches to psychopathology are also clearly part and parcel of clinical practice. Psychosocial and pharmacological intervention strategies often are effective because they track clinically salient clusters of symptom dimensions61. Indeed, dimensional conceptualization and corresponding intervention strategies are arguably (if not always explicitly) the essence of clinical practice62. Triage is often a matter of matching the intensity of the presentation with the intensity of intervention. In routine clinical practice, the key decision is not typically “to treat or not to treat”. Rather, the key decision is “what level of intervention best suits this level of need?”.

To pick a specific example, persons presenting with substance use problems are not clinically homogenous in their level of problems and corresponding need for a specific treatment approach (indeed, the DSM‐5’s more dimensional conceptualization of substance use disorder reflects this reality). Instead, milder presentations can often be treated effectively through outpatient detoxification (assuming medical stabilization); more severe presentations often benefit from more structured approaches (e.g., partial hospitalization); and very severe presentations often require at least an initial inpatient stay (e.g., for purposes of medical stabilization). As this example makes clear, conceptualizing substance use presentations as “present vs. absent” would be fundamentally at odds with routine and responsible clinical practice63. The clinical translation workgroup serves to make these sorts of dimensional considerations more explicit, and to help disseminate specific dimensionally‐oriented approaches to front‐line clinicians.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

There has been considerable recent interest in empirical approaches to psychopathology classification. This interest has arisen for various reasons, but arguably, the overarching consideration and motive is to place classification on an empirical playing field, as opposed to relying more on the political considerations that influence traditional nosological endeavors, such as the DSM revision process.

This empirical classification movement is well intended, but numerous challenges remain. For example, will progress result more from a distributed approach, or from a more centrally organized approach? In many sciences, a distributed approach facilitates progress. Laboratories compete for resources, and seek to replicate other laboratories’ work. Classification of psychopathology, however, presents different kinds of scientific and practical challenges. For example, there is a need for coherence in conceptualizing the entire breadth of the subject matter. This need is arguably more acute than in many more focal scientific endeavors. That is, a piecemeal classification would have limited utility in portraying the entire picture, and portraying the entire picture is a key goal in addressing the limitations of extant schemes (e.g., the generally piecemeal nature of category‐driven research efforts).

The HiTOP Consortium formed as a way of addressing this need for breadth and coherence, closely tethered to data. However, HiTOP, like endeavors before it, is a consortium of human clinicians, scientists and scholars, each with their own unique perspectives, in addition to their shared goals. Although focused squarely on the role of data in adjudicating nosological controversies via its principles42, how will HiTOP navigate new evidence, which, after all, is not self‐interpreting? We are optimistic that these challenges can (and indeed must) be surmounted, because moving toward a more empirical approach is critical to the ultimate intellectual health and credibility of the field.

The next phase in the development of HiTOP and the broader field of empirical psychopathology classification may prove to be a watershed in arriving at a data‐based approach to age old questions in classification, and therefore, a system that bridges and unifies both research and clinical practice in mental health.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

R.F. Krueger is supported by the US National Institutes of Health, NIH (R01AG053217, U19AG051426) and the Templeton Foundation; A.J. Shackman by the US NIH (DA040717 and MH107444) and the University of Maryland, College Park; A. Wright by the US National Institute of Mental Health, NIMH (L30MH101760); N.C. Venables by the US National Institute of Drug Abuse (T320A037183); U. Reininghaus by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (451‐13‐022). The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funding sources.

REFERENCES

- 1. Blashfield R. The classification of psychopathology: neo‐kraepelinian and quantitative approaches. Berlin: Springer, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cuthbert BN. The RDoC framework: facilitating transition from ICD/DSM to dimensional approaches that integrate neuroscience and psychopathology. World Psychiatry 2014;13:28‐35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Clarke DE et al. DSM‐5 field trials in the United States and Canada, Part II: test‐retest reliability of selected categorical diagnoses. Am J Psychiatry 2013;170:59‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lubke GH, Miller PJ. Does nature have joints worth carving? A discussion of taxometrics, model‐based clustering and latent variable mixture modeling. Psychol Med 2015;45:705‐15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Haslam N, Holland E, Kuppens P. Categories versus dimensions in personality and psychopathology: a quantitative review of taxometric research. Psychol Med 2012;42:903‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Elahi A, Perez Algorta G, Varese F et al. Do paranoid delusions exist on a continuum with subclinical paranoia? A multi‐method taxometric study. Schizophr Res 2017;190:77‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu RT. Substance use disorders in adolescence exist along continua: taxometric evidence in an epidemiological sample. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2017;45:1577‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu RT. Taxometric evidence of a dimensional latent structure for depression in an epidemiological sample of children and adolescents. Psychol Med 2016;46:1265‐75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Morton SE, O'Hare KJM, Maha JLK et al. Testing the validity of taxonic schizotypy using genetic and environmental risk variables. Schizophr Bull 2017;43:633‐43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Witte T, Holm‐Denoma J, Zuromski K et al. Individuals at high risk for suicide are categorically distinct from those at low risk. Psychol Assess 2017;29:382‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Waller NG, Ross CA. The prevalence and biometric structure of pathological dissociation in the general population: taxometric and behavior genetic findings. J Abnorm Psychol 1997;106:499‐510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Watson D. Investigating the construct validity of the dissociative taxon: stability analyses of normal and pathological dissociation. J Abnorm Psychol 2003;112:298‐305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carragher N, Krueger RF, Eaton NR et al. ADHD and the externalizing spectrum: direct comparison of categorical, continuous, and hybrid models of liability in a nationally representative sample. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2014;49:1307‐17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Conway C, Hammen C, Brennan PA. A comparison of latent class, latent trait, and factor mixture models of DSM‐IV borderline personality disorder criteria in a community setting: implications for DSM‐5. J Pers Disord 2012;26:793‐803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Krueger RF, Markon KE, Patrick CJ et al. Externalizing psychopathology in adulthood: a dimensional‐spectrum conceptualization and its implications for DSM‐V. J Abnorm Psychol 2005;114:537‐50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vrieze SI, Perlman G, Krueger RF et al. Is the continuity of externalizing psychopathology the same in adolescents and middle‐aged adults? A test of the externalizing spectrum's developmental coherence. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2012;40:459‐70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Walton KE, Ormel J, Krueger RF. The dimensional nature of externalizing behaviors in adolescence: evidence from a direct comparison of categorical, dimensional, and hybrid models. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2011;39:553‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wright AGC, Krueger RF, Hobbs MJ et al. The structure of psychopathology: toward an expanded quantitative empirical model. J Abnorm Psychol 2013;122:281‐94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eaton NR, Krueger RF, Markon KE et al. The structure and predictive validity of the internalizing disorders. J Abnorm Psychol 2013;122:86‐92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Forbes MK, Baillie AJ, Schniering CA. Where do sexual dysfunctions fit into the meta‐structure of psychopathology? A factor mixture analysis. Arch Sex Behav 2016;45:1883‐96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kramer MD, Arbisi PA, Thuras PD et al. The class‐dimensional structure of PTSD before and after deployment to Iraq: evidence from direct comparison of dimensional, categorical, and hybrid models. J Anxiety Disord 2016;39:1‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Klein DN, Kotov R. Course of depression in a 10‐year prospective study: evidence for qualitatively distinct subgroups. J Abnorm Psychol 2016;125:337‐48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lubke GH, Luningham J. Fitting latent variable mixture models. Behav Res Ther 2017;98:91‐102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Masyn KE, Henderson CE, Greenbaum PE. Exploring the latent structures of psychological constructs in social development using the dimensional‐categorical spectrum. Soc Dev 2018;12:82‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eaton NR, Krueger RF, South SC et al. Contrasting prototypes and dimensions in the classification of personality pathology: evidence that dimensions, but not prototypes, are robust. Psychol Med 2011;41:1151‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zachar P, Krueger R, Kendler K. Personality disorder in DSM‐5: an oral history. Psychol Med 2015;46:1‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hopwood CJ, Kotov R, Krueger RF et al. The time has come for dimensional personality disorder diagnosis. Personal Ment Health 2018;12:82‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Forbes M, Tackett J, Markon K et al. Beyond comorbidity: toward a dimensional and hierarchical approach to understanding psychopathology across the life span. Dev Psychopathol 2016;28:971‐86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lello L, Avery SG, Tellier L et al. Accurate genomic prediction of human height. bioRxiv (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. von Eye A, DeShon RP. Directional dependence in developmental research. Int J Behav Dev 2012;36:303‐12. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kendler KS. A joint history of the nature of genetic variation and the nature of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 2015;20:77‐83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Okbay A, Baselmans B, De Neve J et al. Genetic variants associated with subjective well‐being, depressive symptoms, and neuroticism identified through genome‐wide analyses. Nat Genet 2016;48:624‐33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Markon KE. How things fall apart: understanding the nature of internalizing through its relationship with impairment. J Abnorm Psychol 2010;119:447‐58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jonas K, Markon K. A model of psychosis and its relationship with impairment. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2013;48:1367‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wakschlag LS, Estabrook R, Petitclerc A et al. Clinical implications of a dimensional approach: the normal: abnormal spectrum of early irritability. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015;54:626‐34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. J Abnorm Psychol 1991;100:316‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Möller HJ, Bandelow B, Volz HP et al. The relevance of ‘mixed anxiety and depression’ as a diagnostic category in clinical practice. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2016;266:725‐36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Waszczuk M, Kotov R, Ruggero C et al. Hierarchical structure of emotional disorders: from individual symptoms to the spectrum. J Abnorm Psychol 2017;126:613‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chmielewski M, Watson D. The heterogeneous structure of schizotypal personality disorder: item‐level factors of the schizotypal personality questionnaire and their associations with obsessive‐compulsive disorder symptoms, dissociative tendencies, and normal personality. J Abnorm Psychol 2008;117:364‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Barlow DH, Farchione TJ, Bullis JR et al. The unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders compared with diagnosis‐specific protocols for anxiety disorders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2017;74:875‐84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Venables NC, Yancey JR, Kramer MD et al. Psychoneurometric assessment of dispositional liabilities for suicidal behavior: phenotypic and etiological associations. Psychol Med 2018;48:463‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stony Brook School of Medicine . The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP). https://medicine.stonybrookmedicine.edu/HITOP.

- 43. Kotov R, Krueger RF, Watson D et al. The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): a dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies. J Abnorm Psychol 2017;126:454‐77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Forbes M, Kotov R, Ruggero C et al. Delineating the joint hierarchical structure of clinical and personality disorders in an outpatient psychiatric sample. Compr Psychiatry 2017;79:19‐30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Carpenter WT, Bustillo JR, Thaker GK et al. The psychoses: cluster 3 of the proposed meta‐structure for DSM‐V and ICD‐11. Psychol Med 2009;39:2025‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Guloksuz S, van Os J. The slow death of the concept of schizophrenia and the painful birth of the psychosis spectrum. Psychol Med 2018;48:229‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kotov R, Watson D, Krueger RF et al. Thought disorder spectrum of the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): bridging psychosis and personality pathology. Submitted for publication.

- 48. Tyrer P, Crawford M, Mulder R. Reclassifying personality disorders. Lancet 2011;377:1814‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Krueger RF, Markon KE, Patrick CJ et al. Linking antisocial behavior, substance use, and personality: an integrative quantitative model of the adult externalizing spectrum. J Abnorm Psychol 2007;116:645‐66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Krueger R, Tackett J. The externalizing spectrum of personality and psychopathology: an empirical and quantitative alternative to discrete disorder approaches In: Beauchaine T. Hinshaw S. (eds). Oxford handbook of externalizing disorders. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015:79‐89. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Eaton NR, Krueger RF, Keyes KM et al. Borderline personality disorder co‐morbidity: relationship to the internalizing‐externalizing structure of common mental disorders. Psychol Med 2011;41:1041‐50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sharp C, Wright AG, Fowler JC et al. The structure of personality pathology: both general (‘g’) and specific (‘s’) factors? J Abnorm Psychol 2015;124:387‐98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Caspi A, Houts RM, Belsky DW et al. The p factor: one general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric disorders? Clin Psychol Sci 2014;2:119‐37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lahey BB, Krueger RF, Rathouz PJ et al. Validity and utility of the general factor of psychopathology. World Psychiatry 2017;16:142‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Morgan GB, Hodge KJ, Wells KE et al. Are fit indices biased in favor of bi‐factor models in cognitive ability research?: a comparison of fit in correlated factors, higher‐order, and bi‐factor models via Monte Carlo simulations. Intelligence 2015;3:2‐20. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Eid M, Geiser C, Koch T et al. Anomalous results in G‐factor models: explanations and alternatives. Psychol Methods 2017;22:541‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Murray AL, Johnson W. The limitations of model fit in comparing the bi‐factor versus higher‐order models of human cognitive ability structure. Intelligence 2013;41:407‐22. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Trull TJ, Widiger TA, Burr R. A structured interview for the assessment of the five‐factor model of personality: facet‐level relations to the axis II personality disorders. J Pers 2001;69:175‐98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Widiger TA, Presnall JR. Clinical application of the five‐factor model. J Pers 2013;81:515‐27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Clark LA, Cuthbert B, Lewis‐Fernández R et al. Three approaches to understanding and classifying mental disorder: ICD‐11, DSM‐5, and the National Institute of Mental Health's Research Domain Criteria (RDoC). Psychol Sci Public Interest 2017;18:72‐145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Waszczuk MA, Zimmerman M, Ruggero C et al. What do clinicians treat: diagnoses or symptoms? The incremental validity of a symptom‐based, dimensional characterization of emotional disorders in predicting medication prescription patterns. Compr Psychiatry 2017;79:80‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Helzer J, Kraemer H, Krueger R. The feasibility and need for dimensional psychiatric diagnoses. Psychol Med 2006;36:1671‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gastfriend DR, Mee‐Lee D. The ASAM patient placement criteria: context, concepts and continuing development. J Addict Dis 2003;1:1‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]