Abstract

Introduction:

Chronic pain in adolescents is a significant medical condition, affecting the physical and psychological well-being of youth and their families. Pain-related stigma is a significant psychosocial factor in adolescents with chronic pain that has been understudied, despite its implications for negative health outcomes, poor quality of life, and increased healthcare utilization.

Objectives:

To examine pain-related stigma in the literature documenting pediatric and adult health-related stigma and present preliminary findings from a focus group of adolescents with chronic pain.

Methods:

In this narrative review, we explored pain-related stigma research and conceptualized the literature to address pain-related stigma among adolescents with chronic pain. Additionally, we conducted a focus group of four adolescent females with chronic pain and using content analyses, coded the data for preliminary themes.

Results:

We propose a pain-related stigma model and framework based on our review and the findings from our focus group. Findings suggest that medical providers, school personnel (ie, teachers and school nurses), peers and even family members enact pain-related stigma toward adolescents with chronic pain.

Conclusions:

Based on this narrative review, there is preliminary evidence of pain-related stigma among adolescents with chronic pain and future research is warranted to better understand the nature and extent of this stigma within this population.

Keywords: Stigma, Chronic pain, Adolescents

1. Introduction

Chronic pain in adolescents is defined as persistent or recurring pain for at least 3 months and has a reported prevalence of 11% to 38%.23 Common pediatric pain complaints include abdominal, back, headache, and diffuse musculoskeletal pain,41 and often are unexplained. Chronic pain negatively affects several functional domains in youth, including school attendance32 and peer relationships,10 and is associated with comorbid anxiety51 and/or depression.22 Chronic pain syndromes are clinically challenging to medical providers, patients, and families. Youth with chronic pain can become frustrated when others disbelieve their pain symptoms, an experience that has also been documented in adult populations,1,24,25 and some evidence suggests that medical providers expressed being puzzled by pain reports of patients that seem disproportionate to medical findings.4 The subjectivity of pain assessment and the invisibility of pain symptoms can contribute to diagnostic uncertainty as well as adolescent perceptions of symptom disbelief by others, including family members, school personnel, peers, and medical providers. As a result of these experiences, adolescents with chronic pain problems are vulnerable to stigma, a phenomenon that has received little attention in this youth population. Because adolescence is a critical period for identity formation and for developing social relationships, the research suggests that pain-related stigma in this population may have particularly large impact on self-esteem and psychosocial health.14,52

Pain-related stigma has been identified as a public health priority in the 2016 National Pain Strategy,40 due to its potential impact on delayed diagnosis, treatment bias, and impairment in treatment recovery. The economic costs of chronic pain in the United States are $635 billion,15 with estimates of $19.5 billion in adolescents alone.17 Diagnostic uncertainty about the conditions presented by adolescents with chronic pain can increase stigma and result in parents' pursuit of numerous medical evaluations for a “legitimate” cause for their child's pain, increasing health care utilization and costs.21

In this review, we summarize the limited literature examining pain-related stigma in the disease experience of adolescents with chronic pain. In addition, we present preliminary qualitative findings regarding pain-related stigma from focus group research with adolescent females with chronic pain. Collectively, this information highlights the implications of pain-related stigma for adolescents and their families, including increased health care utilization, poor quality of health care, and poor health outcomes.

2. Conceptualization of pain-related stigma

The study of social stigma has existed primarily in psychology, sociology, political science, and allied health fields. There has been increasing attention to stigma in chronic health conditions34; within pediatric populations, stigma has been examined in HIV,12,47 epilepsy,2,33 obesity,42,44,49 and sickle cell disease (SCD).56 Stigmatizing experiences have been linked to poor health and increased psychological distress in these youth populations.44,47,56

2.1. Definitions and terminology of stigma

Stigma is the phenomenon in which a person is singled out, judged, and criticized for possessing an attribute considered undesirable by society; it reflects a social construction that devalues a person because he or she possesses a specific attribute.16 Individuals with stigmatized identities are often unfairly discredited, stereotyped, rejected, and/or ostracized in society because of their stigmatized status. There has been considerable recognition of stigma in the context of health, with decades of evidence documenting societal stigmatization of individuals based on their illness or disease.59 Examples of health conditions that are commonly stigmatized include obesity, HIV/AIDS, epilepsy, chronic fatigue syndrome, and chronic pain.39 Health disparities, poor treatment outcomes, and avoidance of treatment documented among individuals with stigmatized health conditions have resulted in broad recognition of stigma as a legitimate barrier interfering with patient health.43

Stigmatization experiences can be characterized as enacted, felt, anticipated, and/or internalized.35 Enacted stigma refers to negative feelings or beliefs held in society toward individuals with the stigmatizing attribute, resulting in stigmatizing behavior toward the individual. Felt stigma is the perception of stigmatized individuals that they are being devalued and unfairly treated by others because of their stigmatizing attribute. Anticipated stigma is the belief of the stigmatized individual that he or she will be negatively judged in the future because of his or her stigmatizing identity. Internalized stigma occurs when stigmatized individuals adopt negative societal beliefs and stereotypes, and engage in self-blame, applying societal stigma to oneself. Thus, stigma consists of intersecting social processes: (1) an individual enacting the stigma belief onto the stigmatized person, and (2) the stigmatized person experiencing distress in response to the stigmatizing event.35 These distinctions may also be relevant to the impact on well-being that stigmatization may have on an individual, particularly if that stigmatization becomes internalized.

3. Implications of stigma for pediatric chronic pain

The majority of chronic pain stigma research has been conducted in adults.24,25,39,40 Pain-related stigma has been linked to increased stress and anxiety, disruptions in social and romantic relationships, social isolation, employment difficulties, and reduced educational opportunities in adults.53 However, adolescents with chronic pain have received little attention, despite the implications of stigma for their quality of health care and well-being. Few studies have evaluated felt stigma and health outcomes in pediatric pain. Wakefield et al.56 reported that among 28 youth with SCD, more perceived stigma was associated with greater reported pain burden and poorer quality of life. Similarly, in a study of 92 adolescents hospitalized for acute SCD episodes, higher SCD stigma scores predicted more pain interference, more loneliness, poorer quality of life, and less pain reduction.36 Two studies have investigated enacted stigma among medical providers4 and teachers29 using vignettes to elicit perceptions of symptom disbelief in pediatric chronic pain. Stigmatizing attitudes from multiple sources may drive social isolation and suffering, and could partly account for poor health outcomes in this population, including depression,22 anxiety,51 poor school functioning,32 and social impairment.10

As the recovery from chronic pain requires functioning in the context of escalated pain episodes, experiencing stigma in the form of negative judgments and blame from peers and authority figures (eg, medical providers and school staff) could undermine coping efforts and hinder recovery. Through our review, we highlight several sources of pain-related stigma toward adolescents, including medical providers, school personnel, family, and peers. Responses from a focus group of adolescent female chronic pain patients (described below) will serve to illustrate how stigmatizing events are experienced by these patients. As concepts of concealability and controllability are highly relevant to pain-related stigma, these 2 concepts are also described.

4. Potential sources of pain-related stigma toward adolescents

4.1. Medical providers

The “invisibility” of pain symptoms contributes to ambiguity and possible frustration in the evaluation of chronic pain conditions for medical providers. Likewise, the difficulty in diagnosing the cause for chronic pain can lead medical providers to question the veracity of pain reports. Many chronic pain conditions do not present with clear medical etiology and may thus prompt medical providers to interpret symptoms as either “real” or “fake.”7 The biomedical model that dominates medical practice has led to dualistic views of chronic pain symptoms, declaring them as either “medical” or “psychological” conditions. For some providers, only medical symptoms (not psychological) are viewed to be “real”; such attitudes among medical providers may indicate a fundamental lack of understanding of the complexities of chronic pain and its determinants. For example, a study evaluating medical provider perceptions of the origin of pain symptoms in a child population using vignettes demonstrated that providers who perceived less medical etiology of the pain condition reported more stigma and less sympathy toward that patient.4 Likewise, adult female patients with back pain reported that their pain has been minimized to “only psychological” when there is an absence of medical findings.27

Parents of children with chronic pain may also be affected by the experience of stigma by medical providers. Parents often experience distress when faced with diagnostic uncertainty regarding their child's chronic pain symptoms, resulting in the seeking of medical justification or an observable cause for their child's pain.21 Thus, the consciously or unconsciously held beliefs of medical providers likely contribute to pain-related stigma among adolescents with chronic pain.

4.2. School personnel

Chronic pain in adolescents interferes with school attendance and academic performance.32 Adolescents with more severe pain conditions have reported poorer attendance, increased academic pressure, lower satisfaction with school, and more experiences of bullying relative to nonaffected classmates.54 School personnel, specifically teachers, administrators, and nurses have reported several barriers to providing accommodations for adolescents with chronic pain, including a lack of education about chronic pain treatment.30 The visible presence of an organic disease process is the single most influential factor for teachers' supportive responses to pain in adolescents.29 Moreover, one research study revealed that 47.1% of school nurses believed that students with chronic pain were faking or seeking attention for their pain symptoms.60 These findings suggest that school personnel may struggle with interpreting the “invisibility” of persistent pain symptoms in the presence of diagnostic uncertainty. As demonstrated with medical providers, when presented with vignettes of children with chronic pain, teachers also tended to endorse a biomedical view of the pain problem, rather than a biopsychosocial one.28

As no research has directly investigated school personnel as a source of pain-related stigma toward youth, it is important for future research to examine this issue in the school environment. In particular, several key questions warrant attention. First, there may be a lack of chronic pain education and understanding among educators and nursing staff.30 Diagnostic uncertainty from the medical community may translate into misunderstanding within the school environment.28 Second, there may be institutional barriers to providing appropriate school accommodations for students with chronic pain.30 Third, the continuing needs of students with chronic pain conditions may reduce nurse or teacher empathy over time. Finally, teachers may hold implicit and/or explicit biases about people with chronic pain, which may extend to negative attitudes toward their students.

4.3. Family members

Research suggests that families of children with chronic pain tend to experience poorer family functioning compared with healthy control groups.26 Functional impairment, not pain intensity, contributes to poor family functioning.26,31 This finding makes intuitive sense because greater functional impairment increases pressure on parents to encourage their child to function in the context of his/her chronic pain. Negative medical findings and possible communication from medical providers that their child's pain is “all in their head” may lead parents to similarly question the legitimacy of their child's symptoms.

The search for medical justification for their child's apparent, but invisible, incapacity is a major source of distress for parents, and one that absorbs considerable resources.18,21 Often, the diagnosis and treatment of chronic pain in adolescents entail multiple visits to multiple health care providers. This is particularly true if multidisciplinary care for chronic pain is sought, which often includes physical therapy, routine medical visits, and psychological interventions. The financial strain on the family related to numerous appointments can be perceived by the adolescent with chronic pain as a burden and could lead to self-blame or internalized stigma. The internalization and self-blame can contribute to symptoms of anxiety and depression in an overweight adult population.9 As this has not yet been studied in the context of youth with chronic pain, internalized stigma is an important priority for the future work. It is also possible that pain-related stigma is a mediator for poor family functioning and psychological distress among adolescents with chronic pain and their families. Furthermore, the impact of pain-related stigma on parents of children with chronic pain, who may both experience and enact pain-related stigma, is also largely unknown. Parents play an instrumental role in their child's health care utilization, and if they feel that their child's needs are not met due to perceived disbelief by medical providers, health care costs could increase if parents seek care from additional medical professionals. In light of these complexities, further research is needed to evaluate parent–child relationships in the context of pain-related stigma and its impact on health care utilization and perceived quality of care.

4.4. Peers

A particularly difficult challenge experienced by adolescents with chronic pain is lack of peer support. Adolescence is a developmental period characterized by significant physical, emotional, and social changes.13 Adolescents rely on their friendships and peer networks to help adapt to such changes, and the absence of peer support at this critical time can be devastating, resulting in missing periods of school, being excluded from social exchanges, feeling different, isolated, or not understood by those who should be friends.13,14,32

Social isolation experienced by adolescents with chronic pain is common due to functional impairment secondary to disease,14 yet disbelief of pain symptoms exacerbates the social disruption and disease-related burden in this young population. Research indicates that social exclusion may occur when there is a perception that an individual has medically unexplained pain,7 as these youth are suspected of attention seeking. Social support buffers adolescents with chronic pain from negative health outcomes.10 Furthermore, social functioning mediates the relationship between adolescents' chronic pain experience and school impairment.50 Previous research has established that peer victimization occurs among adolescents with chronic illnesses,38 and this holds true for chronic pain.11,54,55 There is a clear need for research in this area to identify the nature and extent of peer victimization toward youth with chronic pain, and how these experiences are associated with psychosocial functioning and distress.

5. Moderators of stigma: concealability and controllability

Concealability and controllability have been conceptualized as moderating constructs of stigma experiences in health-related stigma research.35 Concealability refers to how well the stigmatized attribute of an individual can be hidden from others, either in certain situations or all the time. People with concealable stigmatized identities, such as those with mental illness or substance abuse, may be buffered from exposure to societal stigma while their identity is hidden. However, although these individuals can potentially manage exposure to stigma more than individuals with visible conditions, such as obesity, people with concealable stigmatized identities are vulnerable to considerable psychological distress.45 Concealability has been studied among adolescents with HIV, some of whom use silence as a way to prevent and manage potential negative reactions from their peers and the community.12 Rao et al. found that adolescents with HIV often hid their illnesses, in part to avoid stigma from peers and family. The desire to conceal their illness had serious ramifications when they hid information from health care providers, and their own medication adherence suffered.47 When it comes to chronic pain, adolescents may vary in their desire or ability to hide their symptoms from others. When pain does not interfere with physical mobility, chronic pain conditions can be more easily concealed. Because of the anticipation of stigma, adolescents with chronic pain may attempt to mask their pain symptoms. It will be important for future research to identify whether adolescents with chronic pain try to conceal their symptoms, and if so, what impact this has on their well-being.

Adolescent experiences of pain-related stigma may also be influenced by others' perception of whether or not they are at fault for their pain condition. Controllability relates to the perception of how much an individual is perceived to be at fault or is blamed for acquiring the stigmatizing attribute. For example, individuals who are overweight are frequently viewed as being personally responsible for their excess weight.58 Research shows that individuals who are perceived to be personally responsible for their stigmatized status are more likely to be socially stigmatized than individuals who are not blamed for their stigmatizing condition.58

Controllability can be applied to adolescents with chronic pain depending on the extent to which psychological factors are attributed to the onset or maintenance of their condition. The dichotomy of “medical” vs “psychological,” as perceived by medical providers4 and school personnel,28,60 may play an important role in perceptions of controllability of chronic pain. When an adolescent receives the message that his/her pain is “all in your head” and thus perceived by others to be psychological in nature, it may lead to self-blame and internalized stigma. Although concepts of concealability and controllability have not been directly assessed in youth with chronic pain, these issues warrant examination in efforts to better understand the nature and impact of their pain-related stigma experiences.

6. Conceptual model of pain-related stigma in adolescents

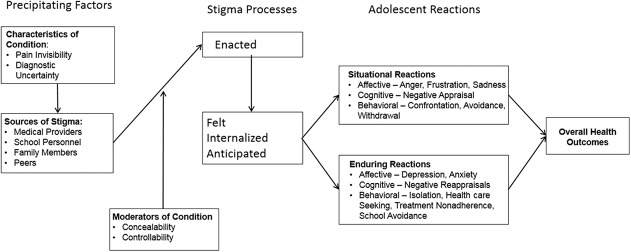

Below, we outline a potential framework for how pain-related stigma may influence adolescents with chronic pain (Fig. 1). It is expected that different chronic pain problems will entail different levels of visibility and perceived controllability. Future research examining visibility and controllability can help inform whether, and to what extent, these moderators of stigma impact quality of life for youth with chronic pain. If connections are present between these moderators and effects on quality of life, it may be useful to direct research to changing those relationships (eg, challenging perceptions of controllability).

Figure 1.

Proposed pain-related stigma model in adolescents with chronic pain.

Likewise, some sources of stigma (eg, family and peers) could have greater impacts on felt and internalized stigma than other sources. The stigma enacted against adolescents with SCD by peers, teachers, and providers could additionally reflect intentional or unconscious bias. Implicit, unconscious biases can be very difficult to alter, and recent efforts to improve unconscious biases in other areas (eg, race relations) may be informative for future research examining chronic pain stigma (eg, Burgess et al.6).

Furthermore, different stigma processes may have different implications for health outcomes in youth with chronic pain. For example, it might be predicted that internalized stigma could have particularly strong effects on self-esteem and psychological well-being, whereas anticipated or experienced stigma could adversely impact social relationships and school avoidance. Our model provides numerous paths that can be tested and offers a framework to guide future work in this area.

7. Focus group: adolescents with chronic pain

As an initial example to illustrate the complex aspects of chronic pain stigma described above, we present here some initial findings from a small focus group of adolescents with chronic pain. Patients aged 12 to 17 years with a documented chronic pain condition were recruited from an outpatient pediatric pain management clinic. Patients with a comorbid chronic medical condition, such as diabetes or juvenile idiopathic arthritis, were excluded to reduce potential bias stemming from other disease-related stigma. Recruitment is ongoing, and we currently have preliminary data from 1 of the 4 focus groups planned. The focus group consisted of 4 adolescent females with chronic pain (age m = 16.55, SD = 1.09). The participants were identified with the following pain conditions: pain amplification syndrome (n = 2), generalized abdominal and chest pain (n = 1), and complex regional pain syndrome (n = 1). Institutional review board approval was obtained, and we collected parental informed consent and patient assent before the focus group interview. Participants were given $20 compensation for study participation. Using a semistructured interview, we asked questions targeting pain-related experiences in a clear, open-ended manner. After participants responded to a question, the interviewer probed for more information to further understand their experiences. The focus group was approximately 60 minutes in duration and was recorded, transcribed, and reviewed for errors in transcription.

Key questions for the focus groups included the following:

(1) Tell me about how your chronic pain was diagnosed. What was your experience of how doctors initially reacted to your pain?

(2) How have teachers and school nurses reacted to your pain? In what ways have they been supportive? In what ways have they not been supportive?

(3) Tell me about how other students and friends reacted to your pain? In what ways have they been supportive? In what ways have they not been supportive?

(4) How do your parents and/or other members of your family support or do not support your pain condition?

(5) Tell me about any time you have felt excluded or treated unfairly by others because of your pain.

(6) Tell me about any time you have been made to feel ashamed of your pain.

(7) Tell me about any time you have been teased or judged negatively because of your pain.

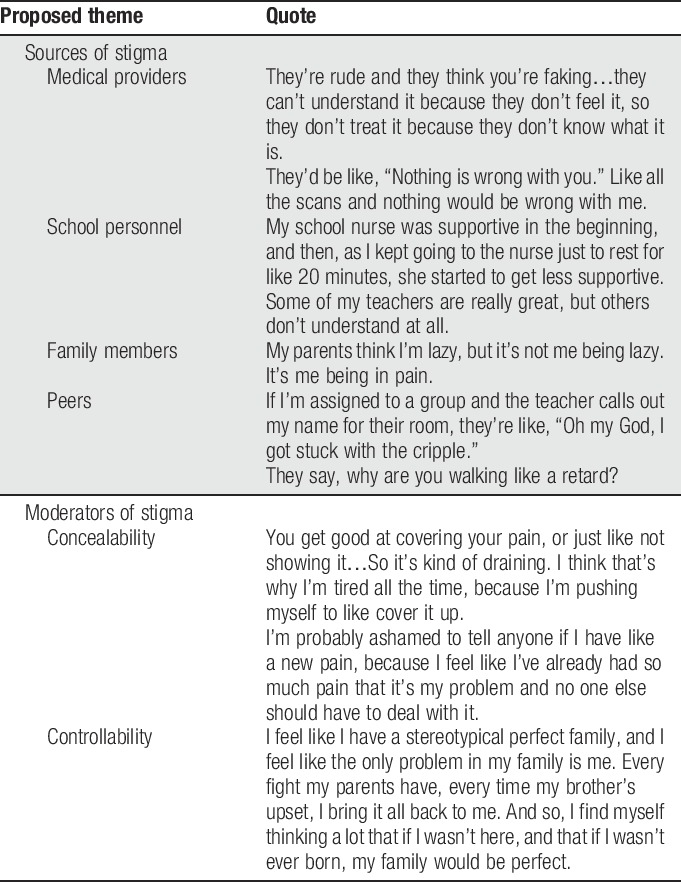

Because of the preliminary nature of the study, the data were not coded to saturation of themes. Instead, the data were reviewed by one coder, who has expertise in chronic pain and stigma, for preliminary themes to include in this review. Pain-related stigma responses that emerged from this focus group are present in Table 1. Several of the patients' responses related to several topics discussed in this review are as follows: sources of stigma, concealability of stigma, and perceived controllability of stigma. The patients reported remarks about their chronic pain that were consistent with stigma made by authority figures, such as teachers and medical providers. In particular, the responses highlight how harmful the expressed attitudes of those in authority (medical personnel and teachers) can be, as well as how socially isolated the respondents may feel as a result of their comments.

Table 1.

Adolescent chronic pain focus group proposed themes and quotes.

8. Research requirement: measurement of pain-related stigma

For research to advance in this understudied area, there is a need to develop and test measures that adequately and accurately assess experiences of pain-related stigma in youth populations. Van Brakel53 conducted a review of health-related stigma measures in children and adult disease and mental health populations. The findings of this review characterized health-related stigma measurement approaches into 4 categories: (1) evaluating actual discrimination experienced by stigmatized individuals, (2) assessment of perceived or internalizing stigma, (3) assessment of stigma beliefs/enacted stigma from others toward stigmatized individuals, and (4) screening for discriminatory practices, legislation, services, and materials. Van Brakel53 concluded that the most promising measures of perceived stigma were the HIV Stigma Scale,3 the Internalised Stigma of Mental Illness Scale,5 an Epilepsy Stigma Scale developed by Jacoby et al.,19 and the Child Stigma Scale developed for children with epilepsy.2

Given that more research has been conducted in adult chronic pain populations than youth populations, pain-related stigma measures for adults have been developed and validated.25,57 However, surveys of stigma intended for adults with chronic pain24,25 cannot capture the unique experiences of stigma perceived by adolescents. Adolescents may not only perceive stigma differently due to their age and developmental stage, but the sources and impact of enacted stigma may also differ considerably. For example, the influence of peers may be more salient and impactful for adolescents than adults. Adverse effects of stigma on job functioning may be particularly impactful on adults, whereas the effect on social status and functioning may be most problematic for adolescents (eg, Forgeron et al.13). When adolescents with chronic pain have reported perceived injustice related to their pain symptoms, they have endorsed poorer outcomes in several domains, including pain intensity, school functioning, catastrophizing, social functioning, and functional disability.37 Although this study was not specific to stigma, it may be a preview of how perceptions of discrimination from enacted stigma may impact the many aspects of psychosocial health in adolescents with chronic pain. The accumulation of enacted stigma and potential discrimination from these groups likely has a significant impact on adolescent social development, which is a crucial aspect to identity formation within this age group.

The availability of existing health-related stigma measures in youth populations is limited to conditions such as epilepsy,2,33 neurological disorders,46 and obesity.48 The Child Stigma Scale,2 developed to evaluate stigma in children with epilepsy, has been adapted to evaluate health-related stigma in youth with SCD.56 Adapting measures developed for other child health conditions to address stigma in adolescents with chronic pain is challenging due to the different ways in which stigma may be experienced across these conditions. For example, epilepsy is a health condition that can be verified through medical findings and, thus, there is likely less enacted stigma related to diagnostic certainty when compared to adolescents with chronic pain. Adolescent chronic pain stigma warrants a unique measurement tool to accurately assess the unique constructs that reflect their stigmatizing experiences.

Of the limited research examining adolescents with chronic pain, previous work has evaluated stigma in young populations with pain conditions4,20 using adaptations of the Chronic Pain Stigma Scale.48 This measure is conceptually promising, but has yet to be validated in the peer-reviewed literature. In light of these limitations, the development and validation of pain-related stigma measures for adolescents with chronic pain is a clear priority for the systematic investigations of pain-related stigma in this population. Future pain-related stigma measurement development for adolescents with chronic pain should include the perception of felt and experiences of internalized stigma as well as the extent to which adolescents attempt to conceal their pain symptoms from others and the level of perceived controllability of their chronic pain condition. Measurement development targeting enacted stigma in medical providers, school personnel, family members, and peers should also be considered.

9. Conclusion

Stigma in chronic pain has received little attention,8 especially among adolescents. Although there is evidence of stigma experienced by adults with chronic pain, this literature does not examine the important sources and complex social pressures that affect adolescents (from peers, school, and family), or the inherent challenges present during the developmental period of adolescence itself. The 2 studies that focused on perceived injustice or stigma in youth pain populations demonstrated that disbelief of symptoms led to a negative impact on health outcomes.37,56 This review provides an important first step in highlighting areas in need of research to better understand the role that stigma plays in the lives of adolescents with chronic pain.

As measurement development progresses in this area, future research can begin to delineate the nature and extent of pain-related stigma from different sources, including medical providers, school personnel, family members, and peers. There is preliminary evidence to suggest that the invisibility of pain in the assessment of adolescent chronic pain may be one contributor to pain-related stigma expressed by medical providers4 and school personnel.28 Additional factors could contribute to assumptions that adolescents are “faking” their pain symptoms, such as individual stressors, adolescent history of anxiety and depression, or stigma beliefs toward adults with chronic pain. Identifying the nature of these relationships and the potential impacts of pain-related stigma on adolescents are clearly warranted. Addressing misconceptions about chronic pain held by teachers and providers is one obvious first step suggested by this review to improve clinical outcomes and inform the development of clinical interventions to target pain-related stigma.

In summary, this review and our preliminary focus group findings highlight the need for increased attention among researchers and clinicians to the neglected area of pain-related stigma in adolescents. Prioritizing efforts in this area can help determine the effects of pain-related stigma on youth health outcomes and quality of life, and ultimately help to reduce stigma towards this vulnerable population. The development of a stigma measure that specifically assesses the complex social dynamics of adolescents with chronic pain is a necessary early step for research in this area.

Disclosures

There are no conflicts of interests to disclose.

This research is supported by the Goldfarb Pain and Palliative Medicine Fund.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contribution of Cheryl Beck, DNSc, CNM, FAAN, who provided consultation on their focus group methodology. The authors also acknowledge the adolescents with chronic pain who were willing to share their experiences with them.

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

References

- [1].Abraham A, Silber TJ, Lyon M. Psychosocial aspects of chronic illness in adolescence. Indian J Pediatr 1999;66:447–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Austin JK, MacLeod J, Dunn DW, Shen J, Perkins SM. Measuring stigma in children with epilepsy and their parents: instrument development and testing. Epilepsy Behav 2004;5:472–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health 2001;24:518–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Betsch TA, Gorodzinsky AY, Finley GA, Sangster M, Chorney J. What's in a name? Health care providers' perceptions of pediatric pain patients based on diagnostic labels. Clin J Pain 2017;33:694–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Boyd Ritsher J, Otilingam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Res 2003;121:31–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Burgess D, van Ryn M, Dovidio J, Saha S. Reducing racial bias among health care providers: lessons from social-cognitive psychology. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:882–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].De Ruddere L, Bosmans M, Crombez G, Goubert L. Patients are socially excluded when their pain has no medical explanation. J Pain 2016;17:1028–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].De Ruddere L, Craig KD. Understanding stigma and chronic pain. PAIN 2016;157:1607–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Durso LE, Latner JD. Understanding self-directed stigma: development of the weight bias internalization scale. Obesity 2008;16:S80–S86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Eccleston C, Wastell S, Crombez G, Jordan A. Adolescent social development and chronic pain. Eur J Pain 2008;12:765–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Fales J, Rice S, Palermo T. (231) Daily peer victimization experiences predict functional disability among adolescents seeking treatment for chronic pain: a prospective diary study. J Pain 2016;17:S33. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fielden SJ, Chapman GE, Cadell S, Hallman LS. Managing stigma in adolescent HIV: silence, secrets and sanctioned spaces. Cult Health Sex 2011;13:267–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Forgeron PA, Chorney JM, Carlson TE, Dick BD, Plante E. To befriend or not: naturally developing friendships amongst a clinical group of adolescents with chronic pain. Pain Manag Nurs 2015;16:721–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Forgeron PA, King S, Stinson JN, McGrath PJ, MacDonald AJ, Chambers CT. Social functioning and peer relationships in children and adolescents with chronic pain: a systematic review. Pain Res Manag 2010;15:27–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gaskin DJ, Richard P. The economic costs of pain in the United States. J Pain 2012;13:715–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Goffman E. Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Groenewald CB, Essner BS, Wright D, Fesinmeyer MD, Palermo TM. The economic costs of chronic pain among a cohort of treatment-seeking adolescents in the United States. J Pain 2014;15:925–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hunfeld JA, Perquin CW, Duivenvoorden HJ, Hazebroek-Kampschreur AA, Passchier J, van Suijlekom-Smit LW, van der Wouden JC. Chronic pain and its impact on quality of life in adolescents and their families. J Pediatr Psychol 2001;26:145–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jacoby A, Baker G, Smith D, Dewey M, Chadwick D. Measuring the impact of epilepsy: the development of a novel scale. Epilepsy Res 1993;16:83–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Jenerette C, Brewer CA, Crandell J, Ataga KI. Preliminary validity and reliability of the sickle cell disease health-related stigma scale. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2012;33:363–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jordan AL, Eccleston C, Osborn M. Being a parent of the adolescent with complex chronic pain: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Eur J Pain 2007;11:49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kashikar-Zuck S, Goldschneider KR, Powers SW, Vaught MH, Hershey AD. Depression and functional disability in chronic pediatric pain. Clin J Pain 2001;17:341–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].King S, Chambers CT, Huguet A, MacNevin RC, McGrath PJ, Parker L, MacDonald AJ. The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: a systematic review. PAIN 2011;152:2729–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kool MB, Van Middendorp H, Lumley MA, Schenk Y, Jacobs JW, Bijlsma JW, Geenen R. Lack of understanding in fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis: the Illness Invalidation Inventory (3*I). Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1990–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kool MB, Van Middendorp H, Boeije HR, Geenen R. Understanding the lack of understanding: invalidation from the perspective of the patient with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:1650–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lewandowski AS, Palermo TM, Stinson J, Handley S, Chambers CT. Systematic review of family functioning in families of children and adolescents with chronic pain. J Pain 2010;11:1027–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lillrank A. Back pain and the resolution of diagnostic uncertainty in illness narratives. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:1045–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Logan DE, Catanese SP, Coakley RM, Scharff L. Chronic pain in the classroom: teachers' attributions about the causes of chronic pain. J Sch Health 2007;77:248–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Logan DE, Coakley RM, Scharff L. Teachers' perceptions of and responses to adolescents with chronic pain syndromes. J Pediatr Psychol 2006;32:139–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Logan DE, Curran JA. Adolescent chronic pain problems in the school setting: exploring the experiences and beliefs of selected school personnel through focus group methodology. J Adolesc Health 2005;37:281–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Logan DE, Scharff L. Relationships between family and parent characteristics and functional abilities in children with recurrent pain syndromes: an investigation of moderating effects on the pathway from pain to disability. J Pediatr Psychol 2005;30:698–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Logan DE, Simons LE, Stein MJ, Chastain L. School impairment in adolescents with chronic pain. J Pain 2008;9:407–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].MacLeod JS, Austin JK. Stigma in the lives of adolescents with epilepsy: a review of the literature. Epilepsy Behav 2003;4:112–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Major B, Dovidio JF, Link BG. The oxford handbook of stigma, discrimination, and health. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Major B, Dovidio JF, Link BG, Calabrese SK. Stigma and its implications for health: introduction and overview. In: Major B, Dovidio JF, Link BG, editors. The oxford handbook of stigma, discrimination, and health. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018. p. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Martin SR, Cohen LL, Mougianis I, Griffin A, Sil S, Dampier C. Stigma and pain in adolescents hospitalized for sickle cell vasoocclusive pain episodes. Clin J Pain 2018;34:438–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Miller MM, Scott EL, Trost Z, Hirsh AT. Perceived injustice is associated with pain and functional outcomes in children and adolescents with chronic pain: a preliminary examination. J Pain 2016;17:1217–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Mukherjee S, Lightfoot J, Sloper P. The inclusion of pupils with a chronic health condition in mainstream school: what does it mean for teachers? Educ Res 2000;42:59–72. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Newton BJ, Southall JL, Raphael JH, Ashford RL, LeMarchand K. A narrative review of the impact of disbelief in chronic pain. Pain Manag Nurs 2013;14:161–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].NINDS. National pain strategy: a comprehensive population health-level strategy for pain. 2015:1–72. Available at: https://iprcc.nih.gov/sites/default/files/HHSNational_Pain_Strategy_508C.pdf. Accessed 1 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Perquin CW, Hunfeld JAM, Hazebroek-Kampschreur AAJM, van Suijlekom-Smit LW, Passchier J, Koes BW, van der Wouden JC. Insights in the use of health care services in chronic benign pain in childhood and adolescence. PAIN 2001;94:205–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Pont SJ, Puhl R, Cook SR, Slusser W. Stigma experienced by children and adolescents with obesity. Pediatrics 2017;140:e20173034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Puhl RM, Heuer CA. Obesity stigma: important considerations for public health. Am J Public Health 2010;100:1019–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Puhl RM, Wall MM, Chen C, Bryn Austin S, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Experiences of weight teasing in adolescence and weight-related outcomes in adulthood: a 15-year longitudinal study. Prev Med 2017;100:173–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Quinn DM, Earnshaw VA. Concealable stigmatized identities and psychological well-being. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 2013;7:40–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Rao D, Choi SW, Victorson D, Bode R, Peterman A, Heinemann A, Cella D. Measuring stigma across neurological conditions: the development of the stigma scale for chronic illness (SSCI). Qual Life Res 2009;18:585–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Rao D, Kekwaletswe TC, Hosek S, Martinez J, Rodriguez F. Stigma and social barriers to medication adherence with urban youth living with HIV. AIDS Care 2007;19:28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Reed P. Chronic pain stigma: development of the chronic pain stigma scale. Unpublished manuscript, Alliant University, San Francisco, CA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Rosenthal L, Earnshaw VA, Carroll-Scott A, Henderson KE, Peters SM, McCaslin C, Ickovics JR. Weight- and race-based bullying: health associations among urban adolescents. J Health Psychol 2015;20:401–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Simons LE, Logan DE, Chastain L, Stein M. The relation of social functioning to school impairment among adolescents with chronic pain. Clin J Pain 2010;26:16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Tegethoff M, Belardi A, Stalujanis E, Meinlschmidt G. Comorbidity of mental disorders and chronic pain: chronology of onset in adolescents of a national representative cohort. J Pain 2015;16:1054–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Upshur CC, Bacigalupe G, Luckmann R. “They don’t want anything to do with you”: patient views of primary care management of chronic pain. Pain Med 2010;11:1791–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Van Brakel W. Measuring health-related stigma—a literature review. Psychol Health Med 2006;11:307–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Vervoort T, Logan DE, Goubert L, De Clercq B, Hublet A. Severity of pediatric pain in relation to school-related functioning and teacher support: an epidemiological study among school-aged children and adolescents. PAIN 2014;155:1118–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Voerman JS, Vogel I, de Waart F, Westendorp T, Timman R, Busschbach JJ, van de Looij-Jansen P, de Klerk C. Bullying, abuse and family conflict as risk factors for chronic pain among Dutch adolescents. Eur J Pain 2015;19:1544–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Wakefield EO, Popp JM, Dale LP, Santanelli JP, Pantaleao A, Zempsky WT. Perceived racial bias and health-related stigma among youth with sickle cell disease. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2017;38:129–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Waugh OC, Byrne DG, Nicholas MK. Internalized stigma in people living with chronic pain. J Pain 2014;15:550.e1–550.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Weiner B, Perry RP, Magnusson J. An attributional analysis of reactions to stigmas. J Pers Soc Psychol 1988;55:738–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Weiss M, Ramakrishna J. Stigma interventions and research for international health. Lancet 2006;367:536–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Youssef NN, Murphy TG, Schuckalo S, Intile C, Rosh J. School nurse knowledge and perceptions of recurrent abdominal pain: opportunity for therapeutic alliance? Clin Pediatr 2007;46:340–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]