Abstract

Background & objectives:

The association of smokeless tobacco (SLT) with cardiovascular diseases has remained controversial due to conflicting reports from various countries. Earlier meta-analyses have shown significantly higher risk of fatal myocardial infarction and stroke in SLT users. However, the risk of hypertension (HTN) with SLT products has not been reviewed earlier. This systematic review was undertaken to summarize the evidence available from global literature on the association of SLT with cardiovascular outcomes – heart disease, stroke and HTN.

Methods:

A systematic literature search was performed in PubMed and Google Scholar since their inception till October 2017 using pre-decided search terms and inclusion/exclusion criteria. Data were extracted from studies included independently by two authors and reviewed.

Results:

The review included 50 studies - 23 on heart disease, 14 on stroke and 14 on HTN. Majority of the studies evaluating heart disease or stroke were conducted in the European Region and most of these did not find a significant association between SLT use and either of these outcomes. On the other hand, 70 per cent of the studies on HTN were reported from South-East Asian Region and about half of the studies found a higher risk of HTN in SLT users.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Current available evidence is insufficient to conclusively support the association of cardiovascular diseases with SLT use due to variability in results and methodological constraints in most of the studies. Region and product-specific well-designed studies are required to provide this evidence to the policymakers. However, advice on cessation of SLT products should be offered to patients presenting with cardiovascular diseases.

Keywords: Cardiovascular, hypertension, myocardial infarction, smokeless tobacco, stroke

Systematic ReviewSmokeless tobacco (SLT) is a large heterogeneous group of products used either orally or nasally without combustion1. Over the years, SLT has assumed global epidemic proportions with users in more than 100 countries2. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has accepted the causative role of SLT products in oral cancer3. However, the linkage of SLT with cardiovascular diseases, i.e., coronary heart disease (CHD)/myocardial infarction (MI)/heart failure, stroke and hypertension (HTN), has not been accepted widely. This is due to the interregion variation in the results available in existing literature, which in turn has been attributed to the differing chemical composition, manufacturing practices and methods of use of products used in various regions4. Various studies have demonstrated deep-rooted community perceptions favouring the use of SLT despite evidence supporting the deleterious health effects of these products. A study from Bangladesh showed that SLT was considered to be a remedy for toothache though almost all participants accepted that these products caused heart disease, cancer and tuberculosis5. A recent study from Nigeria revealed that SLT users believed it to aid in sleep, protect against cold and act as a cure for headaches, apart from giving a ‘feel of high’6.

Earlier meta-analyses have demonstrated a higher risk of fatal CHD and stroke in SLT users, though significant positive association with non-fatal outcome was not demonstrated. These analyses have also highlighted the regional variation in these associations4,7,8,9. HTN has been included in a few studies for its association with SLT use10,11. However, the same has not been summarized as yet in the available literature.

Hence, the present systematic review was undertaken to summarize the available updated evidence on the association of SLT use with heart disease, stroke and HTN with a focus on the debate regarding the association between SLT and CHD.

Material & Methods

Literature search was undertaken independently by two experts (RG and SG) who reviewed all publications. In the event of disagreement, discussions were held to reach a consensus regarding the suitability of the publication. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed12. The inclusion criteria included as follows: (i) Articles published till October 2017 in English language or other languages with summary providing detailed results in English; (ii) Exposure variable: SLT. Studies including both smokers as well as SLT users were considered only if separate results for SLT users were provided; (iii) Outcome variable: cardiovascular disease, CHD or MI or heart failure or stroke or HTN or high blood pressure (BP); and (iv) Study design: case-control, cohort or cross-sectional studies with at least 150 total participants.

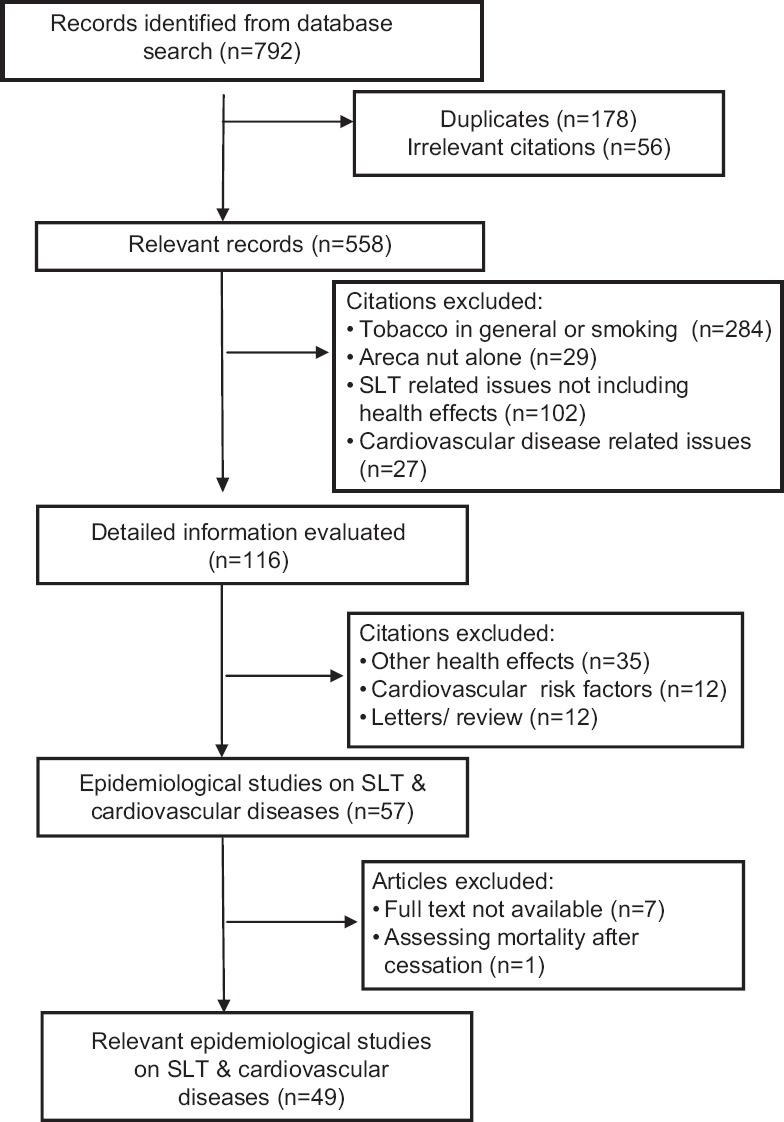

Case reports, case studies, letters or reviews were excluded. Studies reporting on cardiovascular risk factors only and not including outcome were also excluded from the study. PubMed and Google Scholar were used as the primary databases for literature search. An initial search yielded 792 articles. In addition, cross-references of all selected publications as well as earlier reviews on this topic were checked for more articles. The search strategy is outlined in Figure.

Figure.

Search strategy for epidemiological studies on smokeless tobacco (SLT) and cardiovascular diseases included in systematic review.

Results

A total of 50 studies were included in this review (23 with outcome of heart disease, 14 reports on stroke and 14 on HTN).

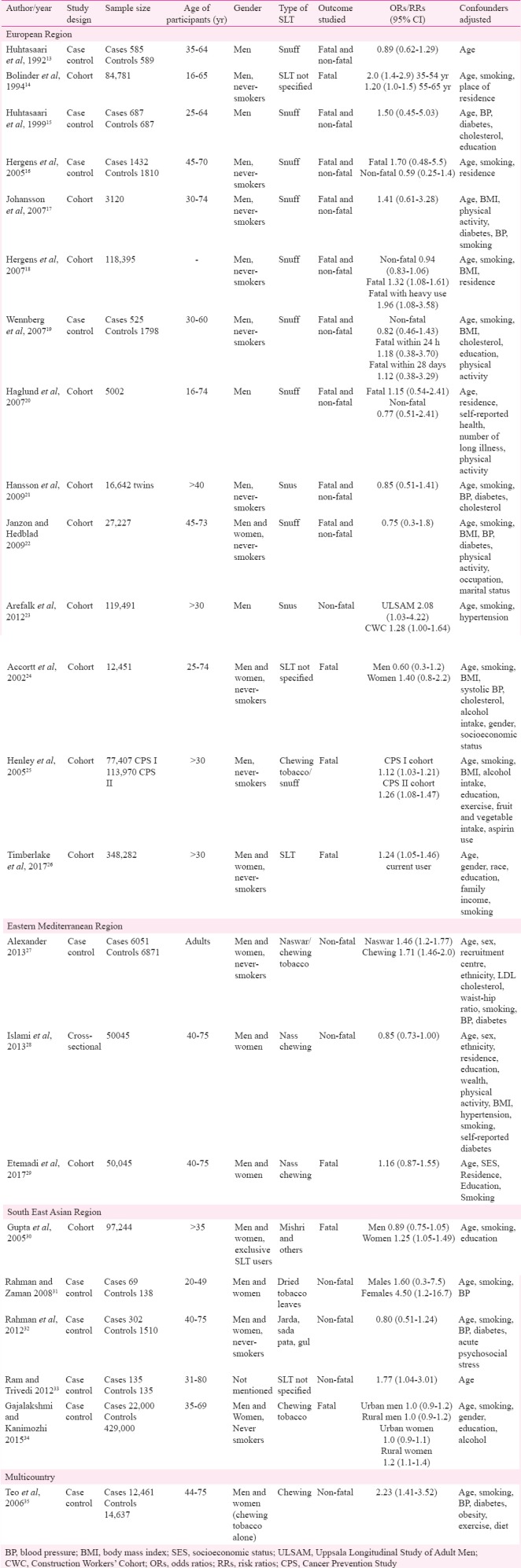

Smokeless tobacco and heart disease: Of the 23 studies reporting on the risk of heart disease in SLT users (Table I), 11 were conducted in European Region (EUR)13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23, three each in American Region (AMR)24,25,26 and Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR)27,28,29 and five were reported from South-East Asia Region (SEAR)30,31,32,33,34. One study, INTERHEART35, was multicountry, though the majority of SLT users belonged to SEAR Region.

Table I.

Detailed characteristic of studies on smokeless tobacco (SLT) and heart disease included in the systematic review

Studies from European region (EUR): Seven of 11 studies from this Region were cohort while four were case control. Except for the study by Janzon and Hedblad22, all other reports included only male SLT users in the adult age range. The predominant type of SLT consumed was snuff (eight studies) or snus (two studies), while the study by Bolinder et al14 did not specify the SLT product used by study participants. The outcome evaluated in one study was fatal CHD14 while in four others, separate results were given for fatal as well as non-fatal CHD16,18,19,20. In five studies, both fatal and non-fatal outcomes were included, though separate results were not given13,15,17,21,22. One study evaluated the risk of first hospitalization due to heart failure23.

Of the 11 studies, two reported the significant positive association of fatal CHD with SLT use14,18. The other three studies reporting on fatal CHD did not find a similar association. The rest of the studies also did not report a significantly increased risk of CHD in SLT users. The study assessing the association of SLT and heart failure demonstrated a higher risk of failure in current snus users23.

Smoking was adjusted in eight studies (including three with positive association). However, other confounding risk factors for CHD such as body mass index, BP, diabetes and cholesterol levels were adjusted in fewer studies.

Studies from South-East Asia Region (SEAR): Majority (four of five) of the studies were case-control design and included both males and females though gender-wise results were provided in only three studies30,31,34. SLT product included in these studies was predominantly chewable tobacco in the form of mishri, jarda, sada pata, gul and others. Three studies evaluated non-fatal outcome31,32,33 while two included only fatal CHD30,34. Two studies showed an overall significant positive association between SLT use and non-fatal CHD31,33. Two studies30,34 reported significantly increased risk of fatal CHD in female SLT users only. Smoking was adjusted in four out of five studies while other risk factors were adjusted in fewer studies.

Studies from American Region (AMR) and Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR): All the three reports from AMR were cohort studies evaluating only fatal outcome. Two studies included both males and females24,26 while the other had only male participants25. All the studies adjusted for smoking while two adjusted for body mass index (BMI). In contrast, one study from EMR was cohort29, one was case-control27 and the third was cross-sectional28. All studies included males and females using naswar/nass or chewing tobacco. The outcome evaluated was fatal in one study29 and non-fatal in other27,28. Smoking was adjusted in all studies; however, other factors such as BP, diabetes and cholesterol were adjusted in only one study27.

Of the studies from AMR, two reported significantly higher risk of fatal CHD in SLT users25,26 while the third study did not find an association between the two24. The results in studies from EMR were also variable (significant in one27 and not in other two28,29).

The landmark INTERHEART case-control study35 reported a significantly higher risk of non-fatal CHD in tobacco chewers [odds ratio (OR) 2.23, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.41-3.52]. The study adjusted for factors such as smoking, BP, diabetes and obesity.

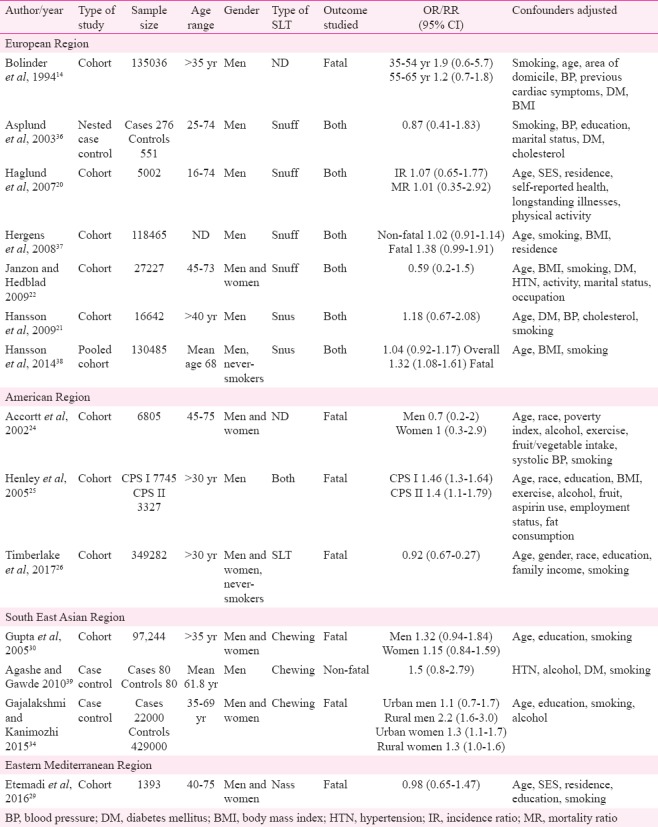

Smokeless tobacco (SLT) and stroke: Fourteen studies were retrieved on the topic of risk of stroke in SLT users. Seven were reported from EUR14,20,21,22,36,37,38, three each from SEAR30,34,39 and AMR24,25,26 and one from EMR29 (Table II). Majority (10) were cohort studies, one nested case-control and two case-control design. Six of seven EUR studies included only males while one included both genders. Only fatal stroke was reported in six studies while non-fatal outcome was reported in three. Four studies included both outcomes, though only two of these provided separate results for fatal stroke.

Table II.

Studies evaluating smokeless tobacco (SLT) and stroke included in the review

All the EUR studies failed to report a significant positive association between SLT use and stroke. One study from SEAR and one from AMR demonstrated a significantly higher risk of fatal stroke in SLT users25,34. Most of the studies (13 of 14) adjusted for smoking as a confounding factor or included never-smoking participants. Only five studies considered HTN as a confounding variable14,21,22,24,39 while diabetes was adjusted in four studies14,21,22,39.

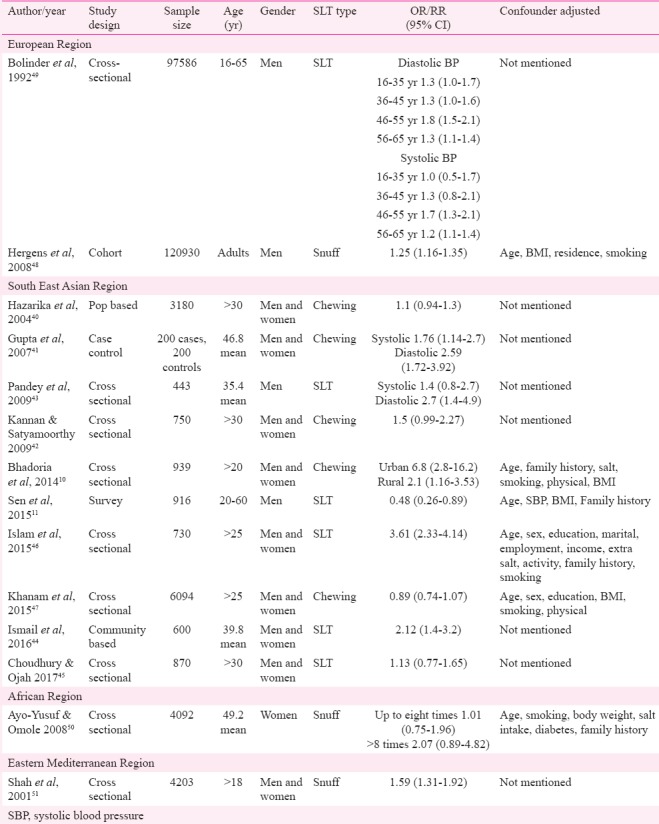

Hypertension in smokeless tobacco users: In contrast to CHD and stroke, a majority of the included studies on the participant of risk of HTN in SLT users were reported from SEAR (eight from India10,11,40,41,42,43,44,45 and two from Bangladesh46,47). Two studies were retrieved from EUR48,49 and one each from AFR50 and EMR51. Most of the studies were cross-sectional and all included adult participants (Table III). Ten of the 14 studies included only men while one had only female participants. In five studies, participants used chewing tobacco, three focused on snuff while the rest six studies did not specify the SLT product used.

Table III.

Study characteristics of included reports on risk of hypertension in smokeless tobacco (SLT) users

Six of 14 studies demonstrated a significant positive association between SLT use and HTN. One study reported significant risk of diastolic HTN in SLT users but not for systolic HTN. Another study found a significant risk of diastolic HTN in SLT users of all age groups (16-65 yr) while systolic HTN was higher in the age range of 46-65 yr49. The remaining six studies did not find any significant association between HTN and SLT use. Only four studies adjusted smoking as confounding variable while three considered salt intake as a confounder.

Discussion

Although SLT has been causatively linked to adverse health effects including addiction, cancers of oral cavity, oesophagus and pancreas and poor reproductive outcomes, its association with cardiovascular diseases has not been accepted widely52. This has mainly been due to the conflicting reports on this topic from various Regions and countries4,7,8,9. Meta-analyses conducted so far on the participant of SLT use and cardiovascular risk have included CHD or MI and stroke4,7,8,9. None of these included the assessment of risk of HTN in SLT users. In the present review all the three cardiovascular outcomes were included in SLT users.

Smokeless tobacco use and heart disease: Heart disease was the most frequently studied cardiovascular outcome with maximum number of studies. Marked regional variation was identified in the results on the association of SLT use with heart disease. Majority of the studies from EUR did not report significantly increased risk of CHD in SLT users while studies from SEAR30,31,34 showed positive association between the two. This regional difference has been attributed to the variation in chemical composition of the products used in these Regions4.

Although European studies do not support the association of CHD with SLT, there have been reports of higher mortality rate due to CHD in individuals switching from cigarettes to spit tobacco [hazard ratio (HR) 1.13, 95% CI 1.00-1.29] in multivariate model adjusted for the duration and number of cigarettes smoked per day before switching apart from other confounding factors53. In this context, reduction of post-MI mortality risk in snus quitters as opposed to continuing snus users (HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.32-1.02) has also been demonstrated54. Such reports support the hypothesis of deleterious effects of SLT products on cardiac functions independently of concurrent or past smoking status. A recently published meta-analysis on the association of SLT use with CHD from our group9 showed significantly higher risk of fatal CHD in SLT users (1.10, 95% CI 0.00-1.27). Regional variation was also reported in this analysis with higher risk for European users compared to other Regions9.

The effect of SLT over cardiovascular risk factors has also been evaluated. Gutka chewers were found to have a significant higher resting heart rate and lower delta heart rate (the difference between maximal heart rate and resting rate) immediately after chewing gutka55. Delta heart rate has been reported to be a risk factor for cardiovascular mortality independent of age, smoking, systolic BP, serum cholesterol and triglyceride level and physical fitness56. Others have reported greater prevalence of risk factors such as obesity, tachycardia at rest, HTN, high total and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and changes on electrocardiogram in SLT users41. A study from Turkey has found impairment in left atrial mechanical function and prolongation of atrial electromechanical coupling intervals in users of maras powder and suggested these changes to be markers of tendency for atrial fibrillation57. Altered lipid profile with lower serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and significantly increased total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol and triglycerides have been demonstrated with SLT products such as naswar and chewing tobacco58,59. However, these results and their implications for cardiovascular disease need to be confirmed in further studies.

Smokeless tobacco use and cerebrovascular disease: Cerebrovascular disease, especially stroke, is a global health problem and a leading cause of disability and death. Smoking has been incriminated as a major risk factor in causation of stroke60,61. However, the association with SLT is similar to that for CHD with conflicting results in studies from various Regions and within a particular Region as well. Majority of the European studies did not report any significant positive association between SLT and stroke, though Hergens et al37 found a significant risk of fatal ischaemic stroke in SLT users, but the same was not detected for haemorrhagic stroke. This difference in risk according to subtype of stroke could well be explained on the basis of differing aetiologic mechanisms of haemorrhagic and ischaemic stroke62.

An earlier meta-analysis demonstrated that 12.8 per cent higher risk of stroke in current users of SLT especially for studies from the United States but not for Swedish users. The risk of fatal stroke was also found to be higher in SLT users in this analysis7. Vidyasagaran et al4 found no overall association of SLT use and non-fatal stroke while risk of fatal events was 13.9 per cent higher in SLT users. Similar results were reported in another meta-analysis of cause-specific mortality in SLT users8. One study evaluated the risk of subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) in smokers and snuff users. The authors found 2.5 times higher risk of SAH in smokers; however, consumption of snuff did not impart a similar risk ratio (relative risk 0.48, 95% CI 0.17-1.30)63.

In addition to the studies included in this review, two other reports that evaluated risk of cardiovascular disease (including both MI and stroke) in SLT users were found50,64. These did not provide separate results for the outcomes and hence, were not included in the present review. One of these studies found an excess risk of cardiovascular disease-related disability pension in the age group of 56-65 yr (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.1-1.9)50. The other study reported a 1.27-fold greater incidence of cardiovascular diseases in current SLT users (95% CI 1.06-1.52) compared to nonusers, and this risk was independent of demographic, socio-economic and other tobacco-related variables64. Hence, there appears to be a significant positive association between SLT use and fatal stroke.

Hypertension and smokeless tobacco use: HTN, an important risk factor for death and morbidity globally, is one of the major causes of ischaemic heart disease, stroke and heart failure65,66,67. For developing countries like India, rule of halves68, i.e., half of the hypertensives are undetected, half of those detected are untreated and half of treated are not well controlled is still valid and poses a significant challenge for control of HTN and incident cardiovascular diseases68,69.

Cigarette smoking has been shown to cause an acute elevation of BP and heart rate due to effect of nicotine on sympathetic nervous system70. However, chronic effect of smoking on BP has not been effectively established due to conflicting reports. Thuy et al71 reported a dose-response relationship between smoking and HTN while others have found a lower BP in smokers compared to non-smokers72. The causal association of SLT with HTN is also similarly debated with approximately half of the studies reporting a significant positive association between the two parameters and the rest not corroborating the same. Some authors have demonstrated an acute increase in heart rate and BP along with elevation of plasma epinephrine after administration of SLT products73. Studies reporting a positive association of SLT use with HTN postulate that frequent use of these products leads to continuous moderate levels of nicotine in blood causing sympathetic nervous system activation and rise in BP48. Additives such as sodium and licorice used in some SLT products are also thought to have hypertensive effects74. A study from SEAR compared BP between smokers and SLT users and found a significantly higher mean diastolic BP in SLT users compared to smokers75. However, this study was limited by the small sample size. A study of ambulatory 24 h BP monitoring in healthy SLT users demonstrated a significantly higher mean systolic BP during daytime as well as in 24 h recordings76. In participants ≥45 yr old, all daytime diastolic and most of systolic BP recordings were significantly elevated in SLT users. BP in SLT users was found to have a strong positive association with serum cotinine values (r=0.48, P<0.001), indicating predominant effect of nicotine on these circulatory parameters76.

Strengths and limitations: The main strengths of this review were the global perspective, comprehensive nature of cardiovascular diseases considered and thoroughness of the literature search on this topic. An earlier policy statement from the American Heart Association summarized the potential cardiovascular effects of SLT use, including all three diseases, but included only Swedish and American studies74. Other reviews and meta-analyses have evaluated MI and/ or stroke only4,7,8,9. This review provides an updated global evidence on all three major cardiovascular outcomes – heart disease, stroke and HTN.

The major limitation of this review was the lack of adequate confounder adjustment in many studies. Although smoking was adjusted as a confounder or study participants included only never-smokers in majority of the reports, other disease-specific risk factors were not adjusted universally in all studies. For instance, risk factors such as HTN, BMI, serum cholesterol levels and physical activity were considered in only a few studies evaluating CHD or MI. Similarly, most of the studies on the risk of HTN in SLT users did not adjust for excess salt intake, obesity, level of physical activity, alcohol intake and stress. In particular, studies from SEAR were found to be poor in confounder adjustment. There is also paucity of studies from African and Western Pacific Regions in the current literature in spite of high prevalence of SLT use in some areas of these Regions. Since the present review was not aimed for a quantitative analysis of risk estimate, it was not possible to comment conclusively on the risk association of cardiovascular diseases with SLT use. However, the available literature does indicate a significantly higher risk of fatal cardiac and cerebrovascular events in SLT users.

Conclusion & way forward

To elucidate a clear view of the cardiovascular risk associated with SLT use, future well-designed studies, preferably multicountry with uniformity in case definition, study methods and relevant confounder adjustments, are imperative. Since regional variability in cardiovascular effects has been demonstrated due to differences in product composition, studies from all regions are required for definitive opinion on the participant. Clarity on the issue of association of cardiovascular disease with SLT would assist the policymakers to include mandatory SLT cessation advice for patients presenting with one of these diseases or their risk factors.

Footnotes

Financial support & sponsorship: None.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Rahman MA. A systematic review of epidemiological studies on the association between smokeless tobacco use and coronary heart disease. J Public Heal Epidemiol. 2011;3:593–603. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sinha D, Agarwal N, Gupta P. Prevalence of smokeless tobacco use and number of users in 121 Countries. Br J Med Med Res. 2015;9:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyon, France: 2004. Smokeless tobacco and some tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. v.89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vidyasagaran AL, Siddiqi K, Kanaan M. Use of smokeless tobacco and risk of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23:1970–81. doi: 10.1177/2047487316654026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahman MA, Mahmood MA, Spurrier N, Rahman M, Choudhury SR, Leeder S, et al. Why do bangladeshi people use smokeless tobacco products? Asia Pac J Public Health. 2015;27:NP2197–209. doi: 10.1177/1010539512446957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adedigba MA, Aransiola J, Arobieke RI, Adewole O, Oyelami T. Between traditions and health: Beliefs and perceptions of health effects of smokeless tobacco among selected users in Nigeria. Subst Use Misuse. 2018;53:565–73. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2017.1349796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boffetta P, Straif K. Use of smokeless tobacco and risk of myocardial infarction and stroke: Systematic review with meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b3060. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinha DN, Suliankatchi RA, Gupta PC, Thamarangsi T, Agarwal N, Parascandola M, et al. Global burden of all-cause and cause-specific mortality due to smokeless tobacco use: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Tob Control. 2018;27:35–42. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta R, Gupta S, Sharma S, Sinha DN, Mehrotra R. Risk of coronary heart disease among smokeless tobacco users: Results of systematic review and meta-analysis of global data. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018 Jan 9; doi: 10.1093/ntr/nty002. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nty002. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhadoria AS, Kasar PK, Toppo NA, Bhadoria P, Pradhan S, Kabirpanthi V, et al. Prevalence of hypertension and associated cardiovascular risk factors in central India. J Family Community Med. 2014;21:29–38. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.128775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sen A, Das M, Basu S, Datta G. Prevalence of hypertension and its associated risk factors among Kolkata-based policemen: A sociophysiological study. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2015;4:225. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huhtasaari F, Asplund K, Lundberg V, Stegmayr B, Wester PO. Tobacco and myocardial infarction: Is snuff less dangerous than cigarettes? BMJ. 1992;305:1252–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6864.1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bolinder G, Alfredsson L, Englund A, de Faire U. Smokeless tobacco use and increased cardiovascular mortality among swedish construction workers. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:399–404. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.3.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huhtasaari F, Lundberg V, Eliasson M, Janlert U, Asplund K. Smokeless tobacco as a possible risk factor for myocardial infarction: A population-based study in middle-aged men. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:1784–90. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00409-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hergens MP, Ahlbom A, Andersson T, Pershagen G. Swedish moist snuff and myocardial infarction among men. Epidemiology. 2005;16:12–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000147108.92895.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johansson SE, Sundquist K, Qvist J, Sundquist J. Smokeless tobacco and coronary heart disease: A 12-year follow-up study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2005;12:387–92. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000169189.22302.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hergens MP, Alfredsson L, Bolinder G, Lambe M, Pershagen G, Ye W. Long-term use of Swedish moist snuff and the risk of myocardial infarction amongst men. J Intern Med. 2007;262:351–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wennberg P, Eliasson M, Hallmans G, Johansson L, Boman K, Jansson JH. The risk of myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death amongst snuff users with or without a previous history of smoking. J Intern Med. 2007;262:360–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haglund B, Eliasson M, Stenbeck M, Rosén M. Is moist snuff use associated with excess risk of IHD or stroke? A longitudinal follow-up of snuff users in Sweden. Scand J Public Health. 2007;35:618–22. doi: 10.1080/14034940701436949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansson J, Pedersen NL, Galanti MR, Andersson T, Ahlbom A, Hallqvist J, et al. Use of snus and risk for cardiovascular disease: Results from the Swedish Twin Registry. J Intern Med. 2009;265:717–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janzon E, Hedblad B. Swedish snuff and incidence of cardiovascular disease. A population-based cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2009;9:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-9-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arefalk G, Hergens MP, Ingelsson E, Arnlöv J, Michaëlsson K, Lind L, et al. Smokeless tobacco (snus) and risk of heart failure: Results from two Swedish cohorts. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012;19:1120–7. doi: 10.1177/1741826711420003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Accortt NA, Waterbor JW, Beall C, Howard G. Chronic disease mortality in a cohort of smokeless tobacco users. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:730–7. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henley SJ, Thun MJ, Connell C, Calle EE. Two large prospective studies of mortality among men who use snuff or chewing tobacco (United states) Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16:347–58. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-5519-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Timberlake DS, Nikitin D, Johnson NJ, Altekruse SF. A longitudinal study of smokeless tobacco use and mortality in the United States. Int J Cancer. 2017;141:264–70. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexander M. Tobacco use and the risk of cardiovascular diseases in developed and developing countries. Cambridge: University of Cambridge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Islami F, Pourshams A, Vedanthan R, Poustchi H, Kamangar F, Golozar A, et al. Smoking water-pipe, chewing nass and prevalence of heart disease: A cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from the Golestan Cohort Study, Iran. Heart. 2013;99:272–8. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Etemadi A, Khademi H, Kamangar F, Freedman ND, Abnet CC, Brennan P, et al. Hazards of cigarettes, smokeless tobacco and waterpipe in a Middle Eastern Population: A cohort study of 50000 individuals from Iran. Tob Control. 2017;26:674–82. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta PC, Pednekar MS, Parkin DM, Sankaranarayanan R. Tobacco associated mortality in Mumbai (Bombay) India. Results of the Bombay Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:1395–402. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rahman MA, Zaman MM. Smoking and smokeless tobacco consumption: Possible risk factors for coronary heart disease among young patients attending a tertiary care cardiac hospital in Bangladesh. Public Health. 2008;122:1331–8. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rahman MA, Spurrier N, Mahmood MA, Rahman M, Choudhury SR, Leeder S. Is there any association between use of smokeless tobacco products and coronary heart disease in Bangladesh? PLoS One. 2012;7:e30584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ram RV, Trivedi A. Smoking, smokeless tobacco consumption & coronary artery disease – A case control study. Natl J Community Med. 2012;3:264–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gajalakshmi V, Kanimozhi V. Tobacco chewing and adult mortality: A case-control analysis of 22,000 cases and 429,000 controls, never smoking tobacco and never drinking alcohol, in South India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:1201–6. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.3.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Teo KK, Ounpuu S, Hawken S, Pandey MR, Valentin V, Hunt D, et al. Tobacco use and risk of myocardial infarction in 52 countries in the INTERHEART study: A case-control study. Lancet. 2006;368:647–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asplund K, Nasic S, Janlert U, Stegmayr B. Smokeless tobacco as a possible risk factor for stroke in men: A nested case-control study. Stroke. 2003;34:1754–9. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000076011.02935.A1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hergens MP, Lambe M, Pershagen G, Terent A, Ye W. Smokeless tobacco and the risk of stroke. Epidemiology. 2008;19:794–9. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181878b33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hansson J, Galanti MR, Hergens MP, Fredlund P, Ahlbom A, Alfredsson L, et al. Snus (Swedish smokeless tobacco) use and risk of stroke: Pooled analyses of incidence and survival. J Intern Med. 2014;276:87–95. doi: 10.1111/joim.12219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Agashe A, Gawde N. Stroke and the use of smokeless tobacco – A case-control study. Healthline. 2013;4:13–8. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hazarika NC, Narain K, Biswas D, Kalita HC, Mahanta J. Hypertension in the native rural population of Assam. Natl Med J India. 2004;17:300–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gupta BK, Kaushik A, Panwar RB, Chaddha VS, Nayak KC, Singh VB, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in tobacco-chewers: A controlled study. J Assoc Physicians India. 2007;55:27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kannan A, Satyamoorthy TS. An epidemiological study of hypertension in a rural household community. Sri Ramachandra J Med. 2009;2:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pandey A, Patni N, Sarangi S, Singh M, Sharma K, Vellimana AK, et al. Association of exclusive smokeless tobacco consumption with hypertension in an adult male rural population of India. Tob Induc Dis. 2009;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ismail IM, Kulkarni AG, Meundi AD, Amruth M. A community-based comparative study of prevalence and risk factors of hypertension among urban and rural populations in a coastal town of S outh India. Sifa Med J. 2016;3:41. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Choudhury SA, Ojah J. A cross sectional study on hypertension and tobacco consumption in the rural adult population of Kamrup, Assam. Int J Sci Res. 2017;6:740–4. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Islam SM, Mainuddin A, Islam MS, Karim MA, Mou SZ, Arefin S, et al. Prevalence of risk factors for hypertension: A cross-sectional study in an urban area of Bangladesh. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2015;2015:43. doi: 10.5339/gcsp.2015.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khanam MA, Lindeboom W, Razzaque A, Niessen L, Milton AH. Prevalence and determinants of pre-hypertension and hypertension among the adults in rural Bangladesh: Findings from a community-based study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:203. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1520-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hergens MP, Lambe M, Pershagen G, Ye W. Risk of hypertension amongst Swedish male snuff users: A prospective study. J Intern Med. 2008;264:187–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.01939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bolinder GM, Ahlborg BO, Lindell JH. Use of smokeless tobacco: Blood pressure elevation and other health hazards found in a large-scale population survey. J Intern Med. 1992;232:327–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1992.tb00593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ayo-Yusuf OA, Omole OB. Snuff use and the risk for hypertension among black South African women. S Afr Fam Pract. 2008;50:64–8. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shah SM, Luby S, Rahbar M, Khan AW, McCormick JB. Hypertension and its determinants among adults in high mountain villages of the Northern areas of Pakistan. J Hum Hypertens. 2001;15:107–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boffetta P, Hecht S, Gray N, Gupta P, Straif K. Smokeless tobacco and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:667–75. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Henley SJ, Connell CJ, Richter P, Husten C, Pechacek T, Calle EE, et al. Tobacco-related disease mortality among men who switched from cigarettes to spit tobacco. Tob Control. 2007;16:22–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.018069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arefalk G, Hambraeus K, Lind L, Michaëlsson K, Lindahl B, Sundström J. Discontinuation of smokeless tobacco and mortality risk after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2014;130:325–32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pakkala A, Ganashree CP, Raghvendra T. Cardiopulmonary efficiency in gutka chewers: An Indian study. J Med Investig Pract. 2014;9:74–8. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sandvik L, Erikssen J, Ellestad M, Erikssen G, Thaulow E, Mundal R, et al. Heart rate increase and maximal heart rate during exercise as predictors of cardiovascular mortality: A 16-year follow-up study of 1960 healthy men. Coron Artery Dis. 1995;6:667–79. doi: 10.1097/00019501-199508000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Akcay A, Aydin MN, Acar G, Mese B, Çetin M, Akgungor M, et al. Evaluation of left atrial mechanical function and atrial conduction abnormalities in maras powder (smokeless tobacco) users and smokers. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2015;26:114–9. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2014-070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sajid F, Bano S. Effects of smokeless dipping tobacco (Naswar) consumption on antioxidant enzymes and lipid profile in its users. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2015;28:1829–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khurana M, Sharma D, Khandelwal PD. Lipid profile in smokers and tobacco chewers – A comparative study. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48:895–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shinton R, Beevers G. Meta-analysis of relation between cigarette smoking and stroke. BMJ. 1989;298:789–94. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6676.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shinton R. Lifelong exposures and the potential for stroke prevention: The contribution of cigarette smoking, exercise, and body fat. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1997;51:138–43. doi: 10.1136/jech.51.2.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: The Framingham Study. Stroke. 1991;22:983–8. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.8.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koskinen LO, Blomstedt PC. Smoking and non-smoking tobacco as risk factors in subarachnoid haemorrhage. Acta Neurol Scand. 2006;114:33–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yatsuya H, Folsom AR ARIC Investigators. Risk of incident cardiovascular disease among users of smokeless tobacco in the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:600–5. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vasan RS, Beiser A, Seshadri S, Larson MG, Kannel WB, D’Agostino RB, et al. Residual lifetime risk for developing hypertension in middle-aged women and men: The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA. 2002;287:1003–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.8.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, et al. Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–52. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wilber JA, Barrow JG. Hypertension – A community problem. Am J Med. 1972;52:653–63. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(72)90055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Deepa R, Shanthirani CS, Pradeepa R, Mohan V. Is the ‘rule of halves’ in hypertension still valid.– Evidence from the Chennai Urban Population Study? J Assoc Physicians India. 2003;51:153–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Faizi N, Ahmad A, Khalique N, Shah MS, Khan MS, Maroof M. Existence of rule of halves in hypertension: an exploratory analysis in an Indian village. Mater Sociomed. 2016;28:95–8. doi: 10.5455/msm.2016.28.95-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ilgenli TF, Akpinar O. Acute effects of smoking on right ventricular function. A tissue Doppler imaging study on healthy subjects. Swiss Med Wkly. 2007;137:91–6. doi: 10.4414/smw.2007.11375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thuy AB, Blizzard L, Schmidt MD, Luc PH, Granger RH, Dwyer T. The association between smoking and hypertension in a population-based sample of Vietnamese men. J Hypertens. 2010;28:245–50. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833310e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Berglund G, Wilhelmsen L. Factors related to blood pressure in a general population sample of Swedish men. Acta Med Scand. 1975;198:291–8. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1975.tb19543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wolk R, Shamsuzzaman AS, Svatikova A, Huyber CM, Huck C, Narkiewicz K, et al. Hemodynamic and autonomic effects of smokeless tobacco in healthy young men. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:910–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Piano MR, Benowitz NL, Fitzgerald GA, Corbridge S, Heath J, Hahn E, et al. Impact of smokeless tobacco products on cardiovascular disease: Implications for policy, prevention, and treatment: A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;122:1520–44. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181f432c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Habib N, Rashid M, Begum U, Ahter N, Akhter D. Blood pressure parameters among smokers and smokeless tobacco users in a tertiary level hospital. Med Today. 2013;25:28–31. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bolinder G, de Faire U. Ambulatory 24-h blood pressure monitoring in healthy, middle-aged smokeless tobacco users, smokers, and nontobacco users. Am J Hypertens. 1998;11:1153–63. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(98)00137-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]