Abstract

Background & objectives:

Over the past decade, the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) has served as a powerful tool to initiate and advance global tobacco control efforts. However, the control strategies have mainly targeted demand-side measures. The goal of a tobacco-free world by 2040 cannot be achieved if the supply-side measures are not addressed. This analysis was undertaken to examine the tobacco control legislations of various Parties ratifying WHO FCTC with an objective to ascertain the status of prohibition of importation, sale and manufacturing of smokeless tobacco products.

Methods:

All 180 Parties to WHO FCTC were included for the study. A comprehensive database of all the parties to FCTC was created and tobacco control legislations and regulations of all parties were studied in detail.

Results:

Overall, the sale of smokeless tobacco (SLT) products was prohibited in 45 Parties. Eleven Parties prohibited manufacturing of SLT products and six Parties imposed a ban on importation of SLT products. Australia, Bhutan, Singapore and Sri Lanka banned all three.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Comprehensive tobacco control strategy with effective tobacco cessation programme should complement strong legal actions such as prohibition on trade in SLT products to meet the public health objective of such laws and regulations. In addition, multisectoral efforts are needed for effective implementation of such restrictions imposed by the governments.

Keywords: Import, legislation, manufacture, prohibition, sale, smokeless tobacco

Tobacco use is responsible for killing more than seven million people every year globally1. However, tobacco consumption continues, especially in low- and middle-income countries, and the burden is not limited to cigarette smoking but extends to smokeless tobacco (SLT) use as well. More than 140 countries in the world suffer from the burden of SLT use with one in 10 males and one in 20 females using SLT products, globally2. The first global public health treaty, World Health Organization (WHO)-Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC)3 has provided a roadmap for protection and prevention from the tobacco epidemic by implementing the recommended demand and supply reduction measures.

Over the past decade, the treaty has served as a powerful instrument to support and advance regional and global tobacco control efforts. However, the strategies have mainly targeted demand-side measures3. There is an economic and a social interest in tobacco. It provides jobs, tax revenue and foreign exchange earnings4. Treating people for tobacco-related illnesses can be costly. Hence, future efforts will need to address supply-side measures, particularly to achieve ‘endgame’ tobacco control objectives.

Attainment of the goal of a tobacco-free world by 20404 will also need to address the supply-side measures such as sale, manufacture and importation of all tobacco products, including SLT. At present the supply-side interventions such as Articles 15, 16 and 17 of WHO FCTC are only a few in comparison to demand-side interventions3. This will build on the success of the WHO FCTC and present the opportunities for a modification within the treaty to create an ambitious and achievable goal to significantly reduce the burden caused by various forms of tobacco, especially SLT4.

Here we examine the tobacco control legislations of various parties ratifying WHO FCTC with an objective to ascertain the status of the prohibition of importation, sale and manufacturing of SLT products. In addition, experiences of some of the countries that have prohibited the sale, import or manufacture of these products are also presented.

Material & Methods

A search of published articles in peer-reviewed journals did not provide useful articles as this aspect of tobacco control has not been given due attention until recently, hence, we looked into various Conference of Parties (COP) reports, WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic 20135, 20156 and 20177 (MPOWER) and WHO SLT survey report8. This also did not give sufficient yield. Finally, we looked into the tobacco control legislations and regulations of all 180 countries which are WHO FCTC ratified Parties and studied their laws in detail9. We also cross checked the availability of SLT products from - Euromonitor International Report (2016)10.

All 180 Parties to WHO FCTC were included for the study (since European Union is also a separate FCTC party it was not included as an entity for analysis). A comprehensive database of all the Parties to FCTC was made from the implementation database of FCTC11 and the FCTC reporting instruments of different cycles were looked at till August 2017. Parties’ implementation reports or any other available documents were further reviewed and systematically confirmed against country's legislation, regulations and programmatic documents. Similarly, information gathered from other sources was either validated by Parties’ documents or other validated documents.

Data were disaggregated by the WHO Regions and high SLT burden countries for further analysis. High SLT burden estimation was based on the various national and global sources of information on tobacco use, Parties having ≥1 million SLT users and/or SLT use prevalence for males or females ≥10 per cent were classified as high SLT burden Parties. Overall, 36 Parties had high burden of SLT by this criteria. These 36 Parties were home to 95 per cent of global SLT users12. In-depth analysis of the efforts taken by various Parties in implementing the ban on sale, manufacture or import or a combination is presented as case studies.

Results

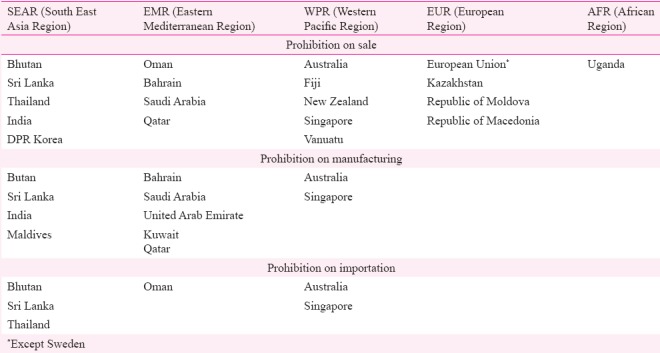

A review of SLT control policies of the 180 Parties to the WHO FCTC revealed that the sale of SLT products was prohibited in 45 Parties-Australia, Bhutan, Bahrain, Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Fiji, India, Kazakhstan, Macedonia, Moldova, New Zealand, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Uganda, Vanuatu and 27 European countries (except Sweden). Eleven Parties (Australia, Bhutan, Bahrain, India, Kuwait, Qatar, Maldives, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates) prohibited manufacturing of SLT products. Six Parties (Australia, Bhutan, Oman, Sri Lanka, Singapore and Thailand) imposed a ban on importation of SLT products. Among the earliest Parties to put a ban on import of SLT products was Thailand, in 1992, followed by Singapore a year later in 1993, and the most recent was Sri Lanka having done so in 2016. Australia, Bhutan, Singapore and Sri Lanka banned all three, i.e. manufacturing, sale and importation13,14,15. WHO Region-wise status of these prohibitions is described in Table I.

Table I.

Region-wise break up of prohibition on sale, manufacture and importation of smokeless tobacco

With the exception of Sweden, the sale of oral tobacco was prohibited in the European Union (EU) under Article 17 of the 2014 EU Tobacco Products Directive (TPD). The TPD defines ‘tobacco for oral use’ as ‘tobacco products for oral use, except those intended to be inhaled or chewed, made wholly or partly of tobacco, in powder or in particulate’. This includes moist snuff and snus, but does not include chewing tobacco16.

It was also seen that manufacturing of SLT products was banned in only three WHO Regions, with a total of eleven countries banning SLT products, Eastern Mediterranean Region toped this chart. It showed that the import of SLT products was banned in only six countries of the world (Table I). International trade agreements make it difficult for countries to ban import of products.

Status among high SLT burden parties

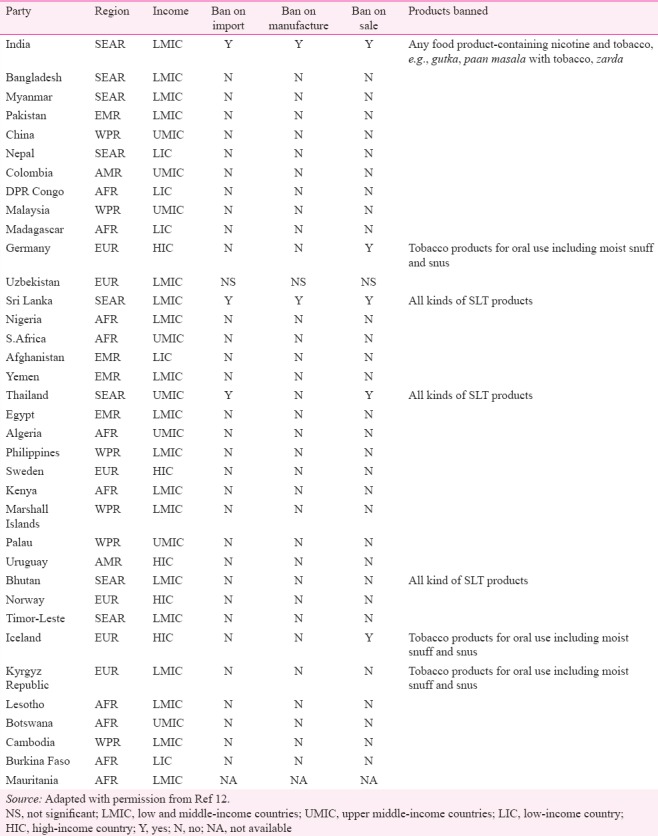

Among the 36 high SLT burden Parties, only Sri Lanka and Bhutan banned the importation, sale and manufacturing of SLT products while India banned manufacturing and sale of commonly used SLT product (gutka) and Thailand banned the import and sale of SLT products. Germany and Iceland banned the sale of tobacco products meant for oral use; however, the ban was not applicable on chewable tobacco (Table II).

Table II.

Ban on import, manufacture and sale of smokeless tobacco among high smokeless tobacco burden parties

Case studies

India: India has implemented comprehensive tobacco control measures through the national tobacco control law17 since 2003 and a dedicated national programme on tobacco control since 200718. Besides tobacco control laws, India has used other legislation as well to advance tobacco control. The Food Safety and Standards Act, 2006 is one such example19. The Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India, notified through the Food Safety and Standards Regualtions in 2011 that the use of tobacco and nicotine as an ingredient in any food item shall be prohibited20. Keeping with this regulation, several State governments started banning sale of gutka (a mixture of mouth fresheners, condiments and tobacco) and other SLT products that contained or were sold after mixing with any food items, e.g., pan masala with tobacco and zarda.

However, a study conducted in seven States (Assam, Bihar, Gujarat, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Orissa) and the National Capital Region to evaluate the impact of Gutka ban in India revealed that most of the users were purchasing tobacco and mixing it with a packet of pan masala. This innovation adversely affected the impact of ban21.

Another Indian study was done for impact evaluation of gutka ban found that the financial and social cost of selling gutka as well as public penalties had an effect on reducing, but not eliminating local gutka supply, demand and use. However, at the same time, the ban could also be contributing to increased profits and promotional activities associated with the sale of other tobacco products and increased use as well as initiation of other types of smokeless and smoked tobacco products22. Vidhubala et al23 conducted a study in Chennai to assess the availability of gutka after it was banned in Tamil Nadu. The study found that even after three years of ban, gutka and pan masala products were widely and easily available in the market. All vendors in the study claimed that they were selling tobacco only23.

Recently released population-level assessment from Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) 2 report revealed an overall decrease in the prevalence of SLT use between 2010 and 2016 (from 25.9 to 21.4%) and also one per cent decrease specifically in gutka use24.

Bhutan: The Tobacco Control Act of Bhutan (2010) regulates tobacco and tobacco products, banning the cultivation, harvesting, production, distribution and sale of tobacco and tobacco products in Bhutan, taking forward a policy dating back to 200425. Under the new law, smoking cigarettes or chewing tobacco is a non-bailable offence. Anybody in possession of tobacco may be imprisoned for up to three years if he is unable to produce a receipt declaring payment of import duties for the products. Enforcement authorities have booked more than 80 people for violation of the law and sent nearly half of them to prison25.

The Act targets smoking in particular though other forms of tobacco products also come under its ambit. Despite the ban on manufacture and sale of all tobacco products, SLT use among adults remained high at 19.7 per cent as per the STEPs survey (STEPwise approach of WHO for non-communicable diseases surveillance) conducted in 2014. Among adolescents aged 13-15 yr SLT use increased significantly, from 18.8 per cent in 2006 to 30.3 per cent in 201326. Possible reasons for this upswing despite the ban may be effective implementation of smoking ban in public places resulting in smokers switching to SLT use27.

Thailand: Thailand was the first country to impose a ban on import of SLT in 199228. The country has a unique model for tobacco control which is based on close cooperation between the Ministry of Public Health, the Thai Health Promotion Foundation and an active coalition of non-governmental organizations involved in tobacco control. This model has helped Thailand to implement a number of stringent policy measures to protect the Thai population from the dangers of tobacco and a substantial decrease in SLT use in the country. As per GATS-Thailand (2011) report29, only 3.2 per cent of people used SLT products. Some of the strong policy measures include taxation, packaging and labelling, advertising bans, import bans and smoke-free public areas30. However, it would be worth noting that there has been an increase in smoking prevalence among men in the country. Smoking is considered more modern than chewing in Thailand31.

European Union: The European Parliament called for a ban on ‘oral tobacco’ in September 198732, following a WHO Study Group recommendation to ‘pre-emptively ban the manufacture, importation and sale of SLT products before they are introduced in the market’. The EU banned oral tobacco from 1992 and reiterated the ban under its subsequent directives issued in 2001 and then in 2014. The EU directive was in response to the increasing tobacco industry tactics to aggressively introduce SLT products into the European Market. The ban, as per Article 17 of the 2014 EU33 Tobacco Products Directive (TPD), applies to all tobacco products meant for oral use, except those intended to be inhaled or chewed, made wholly or partly of tobacco, in powder or in particulate. This includes moist snuff and snus but does not include chewing tobacco or nasal snuff32. This essentially imposed a ban on sale of moist snuff and snus in all the EU Member countries, to prevent the introduction of a product that is addictive and has adverse health effects. However, it left other SLT products that are not produced for the mass market with strict labelling and ingredient regulations34.

Discussion

Almost one-fourth of the Parties enacted laws to ban the trade of all or some kinds of SLT products in some form or the other. However, the impact of these laws on the use of SLT has been different for different Parties. Most of these trade restrictions were partial, either on manufacture, import, sale or a combination of the three and on one or other form of SLT product. Only four Parties, i.e., Bhutan, Australia, Singapore and Sri Lanka prohibited all the three aspects of trade on almost all kinds of SLT products. The restrictions on different aspects of SLT trade has been imposed under different laws and not only under a tobacco control law. For example, India used the food safety law19 and European countries used the Tobacco Product Directives of the EU to restrict the trade in SLT products32,33,34. These restrictions have led to mixed outcomes with limited effect on the prevalence of SLT use. Several studies have suggested that partial bans do not work, as the tobacco industry finds one or the other way to circumvent such policies35,36,37. For example, the partial ban in India that resulted in prohibition on sale of gutka was avoided by the tobacco industry with sale of twin packs of tobacco and non-tobacco products. A comprehensive ban on SLT products in Thailand with adequate financial support to enforce and implement the law yielded better results in restricting SLT use in the country. A comprehensive measure should include both enforcement of the prohibition and also providing support to users who plan to quit and prevent substitution to another SLT use or cigarette smoking. However, effective enforcement of partial prohibitions has been helpful in containing the spread of specific kinds of SLT products in several countries including EU, Singapore and Australia.

Parties to the FCTC should consider using existing legal provisions under food safety, consumer protection like the case of India for limiting the use of SLT products within their jurisdictions and to preemptively restrict such products from entering and taking over the market. Once in force, SLT ban should be effectively monitored and enforced. Impact evaluation of SLT regulations needs to be conducted to help parties adopt comprehensive policies and programmes that are also WHO FCTC compliant, as against partial and piecemeal efforts that do not serve the policy purpose.

There were limitations in this study. Although data were presented regarding type of SLT products; but the analysis did not do a deep dive into various types of SLT products independently and took the WHO reports on face value for this information. The reports of tobacco industries were also out of scope of this study.

In conclusion, comprehensive tobacco control strategy with effective tobacco cessation programme should complement strong legal actions such as prohibition on trade in SLT products to meet the public health objectives of such laws and regulations. Complete and effective implementation of the WHO FCTC remains a precondition for taking such measures. In addition, multisectoral efforts are needed for effective implementation of such restrictions imposed by the governments.

Acknowledgment:

Authors thank WHO FCTC Secretariat for their technical guidance.

Footnotes

Financial support & sponsorship: None.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.GBD 2015 Tobacco Collaborators. Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2017;389:1885–906. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30819-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sinha DN, Gupta PC, Kumar A, Bhartiya D, Agarwal N, Sharma S, et al. The poorest of poor suffer the greatest burden from smokeless tobacco use: A study from 140 countries. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx276. December 22 doi 10.1093/ntr/nt3c276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [accessed on November 15, 2017]. Available from: http://www.who.int/fctc/text_download/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Yach D, Mackay J, Reddy KS. A tobacco-free world: A call to action to phase out the sale of tobacco products by 2040. Lancet. 2015;385:1011–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2013: Enforcing Bans on Tobacco Advertising, Promotion and Sponsorship. [accessed on November 15, 2017]. Available from: http://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/2013/en/

- 6.World Health Organization. Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic. Raising Taxes on Tobacco. 2015. [accessed on November 15, 2017]. Available from: http://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/2015/en/

- 7.World Health Organization. Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic. Implementing Smoke-Free Environments. 2017. [accessed on December 24, 2017]. Available from: http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2017/en/

- 8.World Health Organization. WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation. Report On The Scientific Basis Of Tobacco Product Regulation: Fifth Report Of a WHO Study Group. WHO Technical report series. [accessed on June 20, 2017]. p. 989. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/161512/1/9789241209892.pdf?ua=1&ua=1 .

- 9.Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. [accessed on June 20, 2017]. Available from: http://www.Tobaccocontrollaws.org .

- 10.Euro Monitor International. [accessed on June 10, 2017]. Available from: http://www.euromonitor.com/smokeless-tobacco-in-country/report .

- 11.World Health Organization. Implementation Database, WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Secretariat, Geneva. [accessed on December 23, 2017]. Available from: https://www.Untobaccocontrol.org/impltb .

- 12.Mehrotra R, Sinha DN, Szilagyi T. India, Noida: ICMR-National Institute of Cancer Prevention and Research; 2017. Global smokeless tobacco control policies and their implementation. WHO FCTC global knowledge hub on smokeless tobacco. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhutan Department of Trade. Ministry of Trade and Industry: Royal Government of Bhutan. Notification of the ban on sale of tobacco. DT/GEN-2/2004/87g. 8 November. 2004. [accessed on December 19, 2017]. Available from: http://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/files/live/Bhutan/Bhutan%20-%20Notification%20Ban%20on%20Sale%20of%20Tobacco.pdf .

- 14.Tobacco legislations. Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. [accessed on December 19, 2017]. Available from: www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/legislation/country/australia/laws .

- 15.Health Sciences Authority (Singapore). Smoking (Control of Advertisements and Sale of Tobacco) Act, Chapter 309; 31 May. 1993. [accessed on December 20, 2017]. Available from: http://www.hsa.gov.sg/publish/etc/medialib/hsa_library/health_products_regulation/legislation/smoking__control_of.Par.0416.File.dat/SMOKING%20(CONTROL%20OF%20ADVERTISEMENTS%20AND%20SALE%20OF%20TOBACCO)%20ACT%202010.pdf .

- 16.European Union. Directive 2014/40/EU of the European parliament and of the Council of 3 April 2014 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning the manufacture, presentation and sale of tobacco. Official J Eur Communities. 2014 L 127/1 (29/04/2014) [Google Scholar]

- 17.New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2003. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Cigarette and Other Tobacco Products (Prohibition of Advertisement and Regulation of Trade and Commerce, Production, Supply and Distribution) Act, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2012. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Operational Guidelines: National Tobacco Control Programme. [Google Scholar]

- 19.New Delhi: Government of India; 2018. [accessed on December 20, 2017]. Government of India. Order, Food and Safety Act, 2006, Commissioner of Food Safety and Drugs Administration. Available from: http://www.fssai.gov.in/Food_Commissioners . [Google Scholar]

- 20.Government of India. Food Safety and Standards (Prohibition and Restrictions on sales) Regulations. 2011. [accessed on December 20, 2017]. http://www.fssai.gov.in/Portals/0/Pdf/Food%20safety%20and%20standards%20(Prohibition%20and%20Restrction%20on%20sales)%20regulation,%202011.pdf .

- 21.World Health Organization, Country Office for India. [accessed on December 19, 2017]. Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/india/mediacentre/releases/2014/gutkha_study/en/

- 22.Nair S, Schensul JJ, Bilgi S, Kadam V, D’Mello S, Donta B, et al. Local responses to the Maharashtra gutka and pan masala ban: A report from Mumbai. Indian J Cancer. 2012;49:443–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.107754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vidhubala E, Pisinger C, Basumallik B, Prabhakar DS. The ban on smokeless tobacco products is systematically violated in Chennai, India. Indian J Cancer. 2016;53:325–30. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.197722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Global adult tobacco survey India factsheet 2016-17. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2016-17. [accessed on July 14, 2017]. Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/india/mediacentre/events/2017/gats2_india.pdf?ua=1 .

- 25.New Delhi: WHO-SEARO, WHO; 2015. [accessed on July 12, 2017]. World Health Organization. Global youth tobacco survey: Bhutan report 2013. Available from: http://www.apps.searo.who.int/PDS_DOCS/B5180.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. National Survey for non-communicable disease risk factors and mental health using WHO STEPS approach in Bhutan-2014. [accessed on December 23, 2017]. Available from: http://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/steps/Bhutan_2014_STEPS_Report.pdf .

- 27.Gurung MS, Pelzom D, Dorji T, Drukpa W, Wangdi C, Chinnakali P, et al. Current tobacco use and its associated factors among adults in a country with comprehensive ban on tobacco: Findings from the nationally representative STEPS survey, Bhutan, 2014. Popul Health Metr. 2016;14:28. doi: 10.1186/s12963-016-0098-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chitanondh H. Banning smokeless tobacco. Bangkok: Thailand Health Promotion Institute; 2007–2008. [accessed on December 21, 2017]. Available from: http://www.thpinhf.org/WEB%201.5%20-%20Banning%20smokeless%20T.1 . [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization. Global Adult Tobacco Survey: Thailand Report. 2011. [accessed on December 21, 2017]. Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/tobacco/surveillance/Global_Adult_Tobacco_Survey_Thailand_Report_2011.pdf .

- 30.New Delhi: World Health Organization; [accessed on July 20, 2017]. World Health Organization. South East Asia regional office. Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/tobacco/data/thailand_npa.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reichart PA, Supanchart C, Khongkhunthian P. Traditional chewing and smoking habits from the point of view of Northern Thai betel quid vendors. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2007;5:245–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The European Community. Tobacco Institute Records; RPCI Tobacco Institute and Council for Tobacco Research Records; September. 1987. [accessed on December 20, 2017]. Available from: https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/tgnh0030 .

- 33.Council of the European Union, European Parliament. Directive 2014/40/Eu of the European Parliament and of the Council of 3 April 2014 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning the manufacture, presentation and sale of tobacco and related products and repealing Directive 2001/37/EC. Off J Eur Union. 2014;L127:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kratovil ED. STA/USTI International Letter November 06. US Tobacco Records on Smokeless Tobacco. United States Tobacco Company. 1987. [accessed on December 25, 2017]. Available from: https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/rglh0037 .

- 35.Li L, Borland R, Yong HH, Sirirassamee B, Hamann S, Omar M, et al. Impact of point-of-sale tobacco display bans in Thailand: Findings from the International tobacco Control (ITC) Southeast Asia survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:9508–22. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120809508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shang C, Huang J, Cheng KW, Li Q, Chaloupka FJ. Global evidence on the association between POS advertising bans and youth smoking participation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:pii: E306. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13030306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson LM, Avila Tang E, Chander G, Hutton HE, Odelola OA, Elf JL, et al. Impact of tobacco control interventions on smoking initiation, cessation, and prevalence: a systematic review. J Environ Public Health 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/961724. 961724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]