Abstract

Objective

Baicalin, a kind of flavonoid extracted from the dry root of Scutellaria, possesses potent anticancer bioactivities in various tumor cell lines. Accumulating evidences show that baicalin induces autophagy and apoptosis to suppress the cancer growth. Moreover, the antineoplastic role of baicalin in human glioblastoma cells remains to be uncovered.

Methods

Both U87 and U251 human glioblastoma cell lines were employed in the present study. Cell viability was tested by Cell Counting Kit-8 and colony-forming assay; Flow cytometry was employed to analyze cell apoptosis, cell cycle, and Ca2+ content. Cell immunofluorescence assays were used for analyzing terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL), light chain 3 beta (LC3B), 5,5′,6,6′-Tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethyl-imidacarbocyanineiodide (JC-1), and Ca2+ content. The protein levels were tested by Western blot. The SPSS software was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Baicalin suppressed the proliferation, migration, and invasion ability of human glioblastoma cells in a dose-dependent manner. Baicalin induced the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and led to mitochondrial apoptosis. The maturation of microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-LC3B indicated the activation of autophagy potentially through PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, and inhibition of autophagy by 3-methyladenine decreased the apoptotic cell ratio. Besides, baicalin increased the intercellular Ca2+ content; meanwhile, chelation of free Ca2+ by 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid inhibited both apoptotic and autophagy. Finally, baicalin suppressed tumor growth in vivo.

Conclusion

Our observations suggest that baicalin exerts cytotoxic effects on human glioblastoma cells by the autophagy-related apoptosis through Ca2+ movement to the cytosol. Furthermore, baicalin has the potential as a candidate for the treatment of glioblastoma.

Keywords: baicalin, glioblastoma, autophagy, mitochondrial apoptosis, PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, Ca2+-dependent pathway

Introduction

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common malignant tumor in the central nervous system, which accounts for ~50% of glioma.1 The canonical treatment of GBM is surgery accompanied by chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The promising prognosis of patients with GBM is poor due to its high proliferation and invasion ability as well as the insensitivity to chemoradiotherapy. As recently estimated, the median survival is about 12–16 months.2 Hence, new strategies for GBM treatment are urgent to be discovered.

Baicalin (7-glucuronic acid-5,6-dihydroxy-flavone) is the major bioactive flavone derived from the root of Scutellaria baicalensis,3 which is commonly used in the traditional Chinese medicine. As previously reported, baicalin harbors remarkable bioactivities, including antioxidation and anti-inflammation, with little toxicity to normal tissues.3,4 Recently, the anticancer function of baicalin is emerging in breast cancer,5 colon cancer,6 and hematological malignancies.7 However, the potential mechanism underlying the cancer cytotoxicity remains unclear, which partially attributes to the autophagy induction ability of baicalin.8,9

Autophagy is a protective conserved process that eliminates physiological byproducts of metabolism.10 Autophagy is a process that initiates with the double-membraned organelles containing the disposable cytoplasmic entities and then these organelles fuse with lysosomes to degrade the cargo. Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 beta (LC3B) serves as the biomarker of the end stage of autophagosome formation.11 LC3B-II, the maturation form of LC3B, locates on the somatic membrane of autophagosomes that represents the activity of autophagy.

Autophagy plays a double-edged role in tumor initiation and progression. It is essential for autophagy to inhibit oncogenesis in pre-malignant cells, but sustain the cancer progression by protecting cancer cells from metabolic stress and by feeding cellular metabolism and repair mechanisms.11 However, excessive activation of autophagy can lead to cell death (type 2 cell death), which is different from apoptosis (type 1 cell death) according to the morphological status.11 Autophagy and apoptosis frequently occur in a hierarchical or independent fashion to contribute to cell death. Nevertheless, excessive autophagy may act as an accomplice upstream of apoptotic cell death, even though inhibition of autophagy can enhance the apoptosis induced by cytotoxic constituents in some cases. Collectively, the relationship between autophagy and apoptosis is complicated for the sake of discrepancies in cell type, stimulus, and environment.12

It is well understood that autophagy is regulated by an intricate control map. Mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) is the best-characterized repressor of autophagic flux.11 PI3K/Akt pathway reduces apoptosis, promotes the survival of cells, and activates downstream mTOR to regulate autophagy.13 In addition, baicalin downregulated PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway as previously reported.14

Calcium is a versatile intracellular second messenger, and it is involved in many pathophysiological processes including gene transcription, and cell differentiation and death.15 An increase in the intercellular Ca2+ levels causes ER stress and constitutes prominent proapoptotic signals,16 which were proven in abundant number of studies. Moreover, Ca2+ overload in the cytosol can induce autophagy potentially via the AMPK/mTOR pathway. Ca2+ binds to calmodulin (CaM) and activates AMPK, which then inhibits mTOR and triggers autophagy.17 Ca2+ is an intermingled stimulator of apoptosis and autophagy, and whether baicalin can increase intercellular Ca2+ is still unknown.

In this present study, we investigated the antineoplastic effect of baicalin of glioblastoma in vitro. The findings here demonstrated that baicalin reduced glioblastoma growth and motility in a dose-dependent manner. Baicalin activated autophagy and apoptosis, while inhibition of autophagy by 3-methyladenine (3-MA) unequivocally decreased the apoptosis. Moreover, Ca2+-dependent pathway is the potential mechanism underlying baicalin-induced apoptosis and autophagy, which was confirmed by the fact that chelation of Ca2+ by 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA) significantly decreased apoptosis and autophagy after baicalin treatment.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

U87 and U251 human glioblastoma cell lines were purchased from the Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Normal human astrocyte (NHA) primary cultures were gained from the Institute of Basic Medical Sciences (Beijing, China). U87 and U251 were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (HyClone, GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, UT, USA). NHA were grown in the Astrocyte Medium (AM, Sciencell, San Diego, CA, USA) as utilized elsewhere.18 The cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2.

Regents and antibodies

Baicalin and 3-MA were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St Louis, MO, USA). BAPTA-AM was purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Shanghai, China). Anti-Bax, anti-Bcl-xl, anti-cleaved caspase 3, anti-PARP, anti-mTOR, anti-p-mTOR, anti-AKT, anti-p-AKT, anti-cyclin D1, anti-cyclin B1, anti-cyclin A, anti-ZO-1, anti-Catenin, anti-Vimentin, and anti-β-actin antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Anti-LC3B, anti-MMP-2, and anti-beclin 1 antibodies were purchased from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO, USA). Anti-HMGB1 and anti-p62/SQSTM1 antibodies were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated and FITC-conjugated antirabbit or antimouse IgG antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA, USA).

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was done with the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) following the manufacturer’s instruction. NHA, U87 and U251 cells were seeded in the 96-well plates at 5×103 cells for 24 hours before baicalin administration. Baicalin was diluted in the DMEM into the concentrations of 0, 25, 50, 100, 150, 200, and 300 µM. After treatment for 48 hours, we removed the previous medium and then added 10% CCK-8 diluted with DMEM 100 µL per well. After incubating at 37°C for 2 hours, the plates were analyzed with Bio-Rad ELISA microplate reader at the value of 450 nm wavelength (OD450). We calculated the viability with the following formula: cell viability = (OD450 of treated groups/OD450 of control group)×100%.

Colony-forming assay

U87 and U251 cells were seeded onto the six-well plates at a density of 1,000 cells per well. We changed the medium (0, 50, 100, 150, 200, and 300 µM baicalin) every 3 days and incubated the plates for 12 days. After methanol fixing for 20 minutes, the colonies were stained with 0.1% crystal violet (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) for photographing.

Migration and invasion assay

Transwell assays were employed to evaluate the motility and invasive captivity of U87 and U251 cells when treated with baicalin. For migration assay, a total of 2×105 cells in 200 µL DMEM were added into the upper chamber of 6.5 mm transwells with 8.0 µm pore polycarbonate membrane inserts (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA). However, for invasion assay, the upper chambers were covered with additional matrigel matrix (Corning Incorporated). After incubating at 37°C for 16 hours, we cleaned up the cells in the interior of the chamber that did not penetrate the membrane. Subsequently, the chambers were fixed with paraformalde-hyde for 15 minutes and then stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 10 minutes. The migrating cells were observed in six microscopic fields (200×) under an inverted microscope by two investigators blind to the grouping (Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Jena, Germany).

Flow cytometry

For cell cycle analysis, U87 and U251 cells were harvested and fixed with 75% ethanol. After propidium iodide (PI) staining, nuclei were analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

For apoptosis analysis, cells were harvested and suspended with 500 µL of binding buffer containing 5 µL of Annexin V-FITC (AV) (KGA108, KeyGEN, China) and 5 µL of PI (BD Biosciences) and then the apoptotic cells were analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

For Ca2+ content analysis, about 2 µM Ca2+ indicator, fluo-2 (KGAF022, KeyGEN, Nanjing, China), was loaded into the U87 and U251 cells for 60 minutes at 25°C, and the level of intracellular Ca2+ was finally estimated by flow cytometry (BD Biosciences) using FL2 fluorescent intensity.

Western blot

Western blot assays were operated as described elsewhere.19 In brief, U87 and U251 cells were treated with 0, 25, 50, 100, 200, and 300 µM baicalin for 48 hours and then harvested. Equal amounts of samples were subjected to electrophoresis on 8%–12% SDS–PAGE gels and then transferred onto a PVDF membrane (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). After blocked with 5% skim milk for 2 hours at room temperature, the blots were incubated at 4°C overnight with separate primary antibodies. After washing with TBST, membranes were incubated with the corresponding secondary HRP-conjugated antibodies. Finally, the protein bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagents (EMD Millipore) using a chemiluminescence imaging system (Tanon, Shanghai, China).

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) analysis

The apoptotic cells were observed by fluorescence stain using a TUNEL detection kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) according to the method described elsewhere.20 The extensive DNA fragmentation of the U87 and U251 cells was featured with condensed nuclei. All the slides and tumor sections were observed in six microscopic fields (400×) by two investigators blind to the grouping.

Immunofluorescence

U87 and U251 cells were seeded onto the glass cover slips and allowed to attach overnight. After separate concentration of baicalin (0, 100, 200, and 300 µM) treatment for 48 hours, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes and then treated with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes. The primary antibodies of LC-3B was incubated at 4°C overnight following by the CY3-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 minutes. All the images were taken using a ZEISS immunofluorescence microscope (400×).

Immunohistochemical staining

For immunohistochemistry analysis, the U87 xenograft tumor tissue sections (4–6 µm) were incubated with anti-Ki-67 antibody (1:200, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA) overnight at 4°C. The sections were incubated with HRP-conjugated IgG (1:500, Santa Cruz) for 1 hour followed by washing in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for two times, 10 minutes each. Ki-67 was stained with diaminobenzidine and cell nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential

We used the mitochondrial membrane potential assay kit with 5,5′,6,6′-Tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethyl-imidacarbocyanineiodide (JC-1) (Beyotime) to analyze the effect of baicalin on mitochondria following the manufacturer’s instruction. U87 and U251 cells were administrated with baicalin (0, 100, 200, and 300 µM) for 48 hours and then were subjected to the JC-1 staining in the incubator for 30 minutes. The aggregates (red) and the monomer (green) were visualized under the ZEISS immunofluorescence microscope (400×).

Tumor xenografts study

All experimental procedures and protocols involving mice were reviewed and approved by the Animal Investigation Ethics Committee of Jinling Hospital and were conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals by the National Institutes of Health. A total of 1×107 U87 cells were suspended in 100 µL of PBS and injected subcutaneously in the right flank of male BALB/c athymic nude mice (Charles River Breeding Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA) at the age of 4–6 weeks. The tumor volume (V) was calculated by the following formula: V (mm3) = (major axis) × (minor axis)2 × 0.5236. We evaluated the tumor volume and body weight every 3 days. The mice were randomly assigned into three groups (0, 50, and 100 mg/kg of baicalin). Once the tumor was palpable, different concentrations of baicalin were intra-peritoneally injected into the nude mice every 24 hours for 10 consecutive days. Finally, the nude mice were euthanized and the tumors were dissected, weighed, and photographed.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) software was employed to analyze all the data. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM and evaluated by Student’s t-test and ANOVA for multiple comparisons. P<0.05 was considered as a gauge of statistical difference.

Results

Baicalin inhibits the proliferation of glioblastoma cells

To investigate the inhibitory role of baicalin on human glioblastoma cell lines (U87 and U251), we employed the CCK-8 assay to determine the cell viability. Baicalin was added into the cell medium in a concentration gradient (0, 25, 50, 100, 150, 200, and 300 µM) for 48 hours. We found that baicalin significantly reduced cell viability to about 50% in a dose of 300 µM (Figure 1A and B). Besides, we used NHAs to evaluate the biotoxicity of baicalin. Our results showed that baicalin did not influence the viability of NHAs to the dose of 300 µM (Figure 1C).

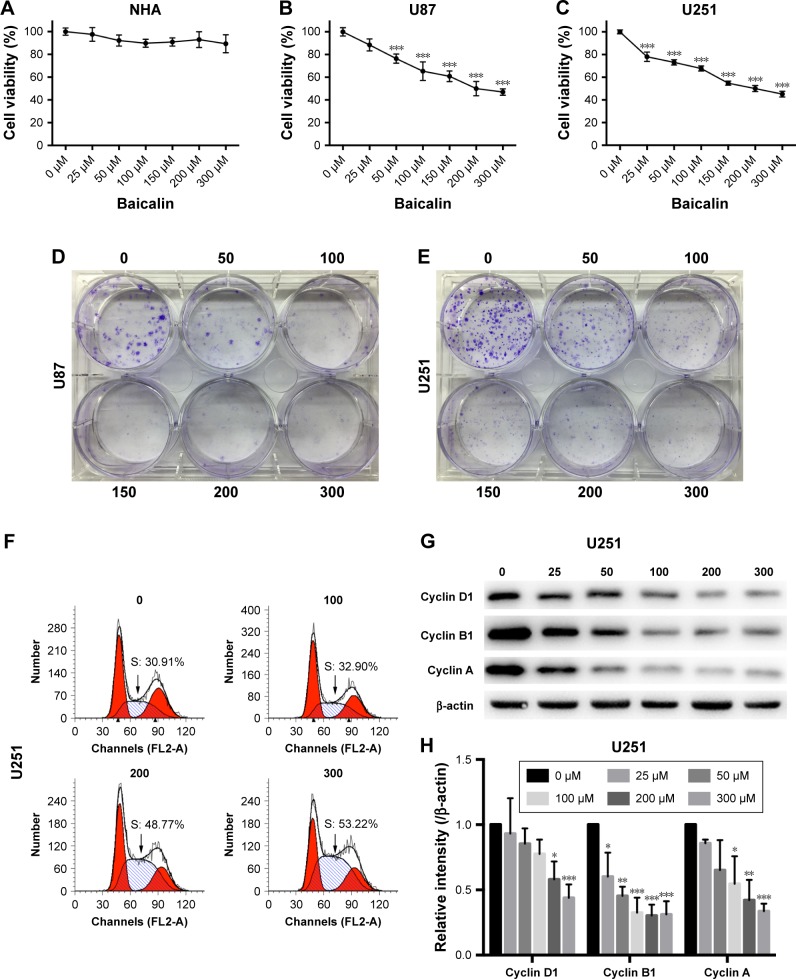

Figure 1.

Baicalin inhibits proliferation and induced S-phase arrest of glioblastoma cells.

Notes: (A–C) NHA, U87, U251 cells were treated with baicalin at the indicated concentrations (0, 25, 50, 100, 150, 200, and 300 µM) for 48 hours, and the cell viability was analyzed by CCK-8 assay. Baicalin suppressed the cell viability of glioblastoma without affecting NHA. (D, E) Increasing concentrations of baicalin (0, 50, 100, 150, 200, and 300 µM) repressed the colony forming with decreasing colony number and size. (F) Baicalin increased the percentage of S-phase in the cell cycle in U251 cells. (G, H) The expression of S-phase arrest proteins, cyclin D1, cyclin B1, and cyclin A, was reduced after baicalin treatment in a dose-dependent manner. The relative protein levels of control cells were adjusted to the value of 1. Data were represented as the means ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs control group (0 µM baicalin).

Abbreviations: CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; NHA, normal human astrocyte.

The colony-forming assay was employed to determine the long-term repressive role of baicalin on U87 and U251. Separate concentrations of baicalin (0, 50, 100, 150, 200, and 300 µM) were administrated to the six-well plate for 12 days. As shown in Figure 1D and E, the size and the number of colonies were much smaller after treatment with baicalin than the control group.

Baicalin blocks the cell cycle of glioblastoma cells in S phase

To evaluate the effect of baicalin administration on cell cycle profile, we utilized the flow cytometry to analyze the cell cycle distribution of glioblastoma after pretreated with 0, 100, 200, and 300 µM baicalin for 48 hours. The observation showed that in U251 cell line treated with different doses of baicalin, the percentage of cells in S phase increased in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1F). We subsequently examined the cyclin A, cyclin B1, and cyclin D1 protein level, which directly regulated the S-phase transition.21 We found that baicalin obviously restrained the expression of cyclin A, cyclin B1, and cyclin D1 (Figure 1G and H). However, the S-phase blockage did not apply to U87 cells (data not shown). Taken together, all these results suggested that baicalin reacted on the S-phase arrest in the U251 glioblastoma cell line.

Baicalin suppresses the migration and invasion ability of glioblastoma cells

The motility of U87 and U251 cells were measured by transwell assays. After treatment with separate doses of baicalin (0, 100, 200, and 300 µM) for 16 hours, the cells that penetrated the polycarbonate membrane with or without matrigel matrix were visualized by microscope in the 200× magnification. As shown in Figure 2A and B, the migration and invasion ability was dose dependently suppressed by baicalin. We then counted the cells in six different fields every chamber and found that baicalin inhibited the motility of glioblastoma statistically (Figure 2C and D).

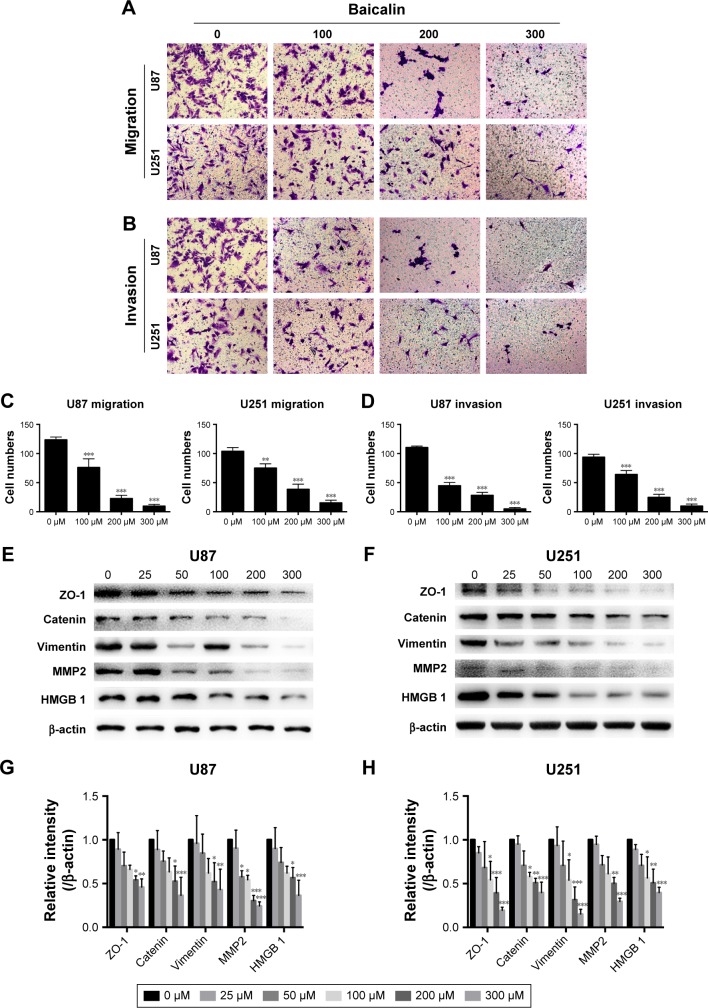

Figure 2.

Baicalin (0, 100, 200, and 300 µM) suppresses the migration (A) and invasion (B) ability of glioblastoma cells in transwell assays. (C, D) Quantification of the number of migrated and invasive cells was analyzed in six independent fields. (E–H) The expression of cell motility related proteins, ZO-1, β-catenin, Vimentin, HMGB 1, and MMP 2, was decreased after baicalin treatment. The relative protein levels of control cells were adjusted to the value of 1. Data were represented as the means ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs control group (0 µM baicalin).

Abbreviations: HMGB 1, High mobility group box 1; MMP 2, matrix metalloproteinase-2; ZO-1, Zonula occludens-1.

Next, we analyzed several protein levels that related to the migration and invasion ability. The expression of ZO-1, β-catenin, Vimentin, HMGB 1, and MMP 2 were detected by Western blot (Figure 2E and F) and we observed a significant decrease of all the protein levels (Figure 2G and H). Collectively, our observations indicated that baicalin suppressed the migration and invasion of glioblastoma cells in a concentration-dependent manner.

Baicalin induces mitochondrial apoptosis in glioblastoma cells

As mentioned above, baicalin suppressed the glioblastoma growth; however, whether baicalin played a role in the induction of apoptosis still needed investigation. Bcl-xl is the antiapoptotic protein in the Bcl-2 family, while Bax is the pro-apoptotic protein. They locate in the outer membrane of mitochondria and control the permeability of cytochrome c through mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channel. The release of cytochrome c activates PARP and caspase 3, thus triggering the apoptotic cascade. Here, we found that baicalin increased the expression of Bax and decreased Bcl-xl, which promoted the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria. The activated form of PARP and caspase 3 were upregulated in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3A–D).

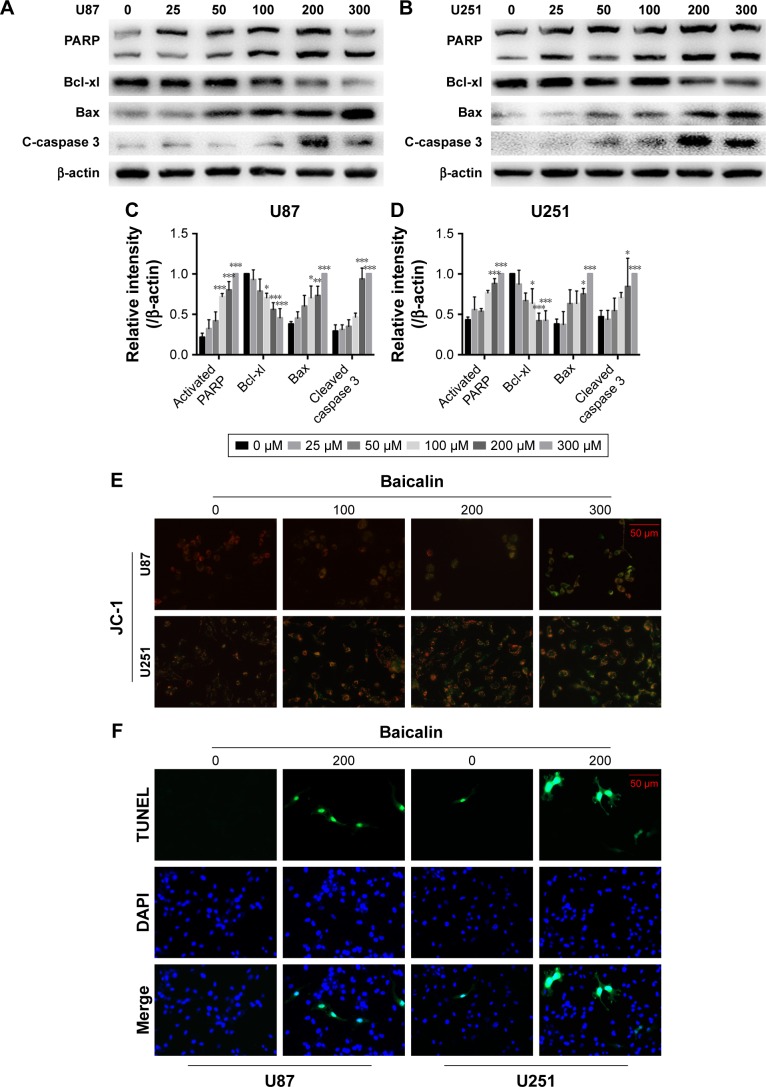

Figure 3.

Baicalin induces the mitochondrial apoptosis.

Notes: (A–D) The expression of proapoptotic proteins, PARP, Bax, and cleaved caspase 3, was increased, while that of the antiapoptotic protein, Bcl-xl, was decreased in U87 and U251 cells after separate doses of baicalin treatment. The relative protein levels of control cells were adjusted to the value of 1. (E) The mitochondrial membrane potential (∆ψm) was detected by JC-1 staining. The green fluorescence represented the monomer of JC-1, which indicated the dissipation of ∆ψm after baicalin treatment. Baicalin (0, 100, 200, and 300 µM) treatment increased the green fluorescence in a dose-dependent manner. (F, G) TUNEL analysis showed that the late-phase apoptotic cells were increased after 200 µM baicalin treatment in both U87 and U251 cells. Quantification of the number of TUNEL-positive cells was analyzed in six independent fields. Data were represented as the means ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs control group (0 µM baicalin).

Abbreviations: JC-1, 5,5′,6,6′-Tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethyl-imidacarbocyanineiodide; PARP, Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling.

Besides, the mitochondrial apoptosis attributes to the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (∆ψ m) that regulates the release of cytochrome c. We then analyzed the JC-1 as a molecular probe of ∆ψm. As shown in Figure 3E, the monomer of JC-1 was formed and visualized in green when the ∆ψm was destroyed after treatment with baicalin (0, 100, 200, 300 µM).

To verify the proapoptotic effect of baicalin, we then employed TUNEL analysis to show the late-phase apoptosis of cells. Figure 3F and G showed that the TUNEL-positive cells were increased significantly after treatment with 200 µM baicalin. Collectively, the above findings demonstrated that baicalin induced mitochondrial apoptosis in glioblastoma cells.

Baicalin induces autophagy-related apoptosis via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway

We then ascertained the autophagy induction role of baicalin. First, we analyzed the expression of LC3B-II, the biomarker of autophagosome formation, by Western blot and immunofluorescence. Figure 4A showed that baicalin induced autophagy in a dose-dependent manner. We also found that beclin 1 protein level was increased and p62, the scaffold protein of autophagosome, was decreased, which suggested the activation of autophagy. Besides, PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway was reported to be involved in the regulation of both autophagy and apoptosis. Therefore, this pathway was studied and we found that the phosphorylation of AKT and mTOR were decreased (Figure 4B–E), which further certified the apoptosis and autophagy induced by baicalin.

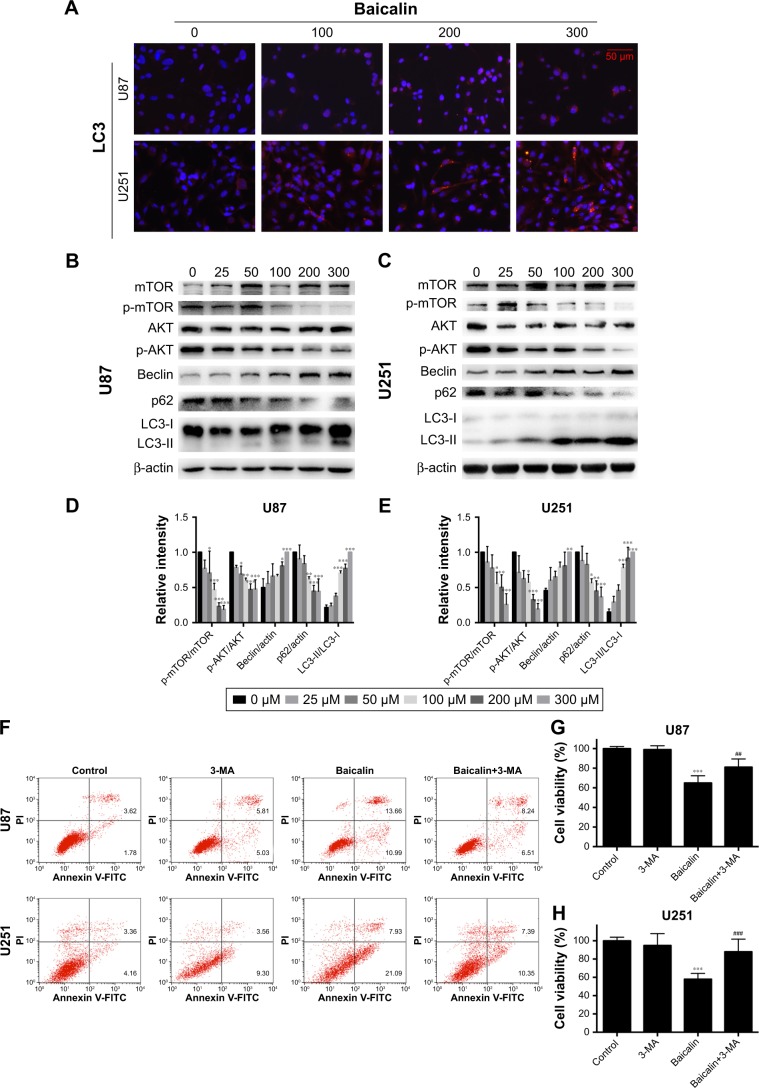

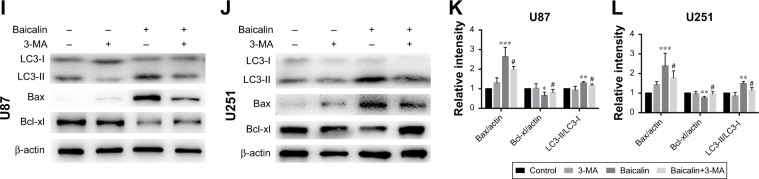

Figure 4.

Baicalin triggers autophagy-related apoptosis via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway.

Notes: (A) The immunofluorescence staining of LC3B (red) showed that baicalin increased the autophagosome formation. (B–E) The expression of mature LC3B (LC3B-II) was increased with the upregulation of beclin 1 and the degradation of p62. The phosphorylation of AKT and mTOR was decreased, which were detected by Western blot and then quantified by imageJ. (F–L) U87 and U251 cells were treated with either 200 µM baicalin or 3 mM 3-MA, or a combined treatment of baicalin and 3-MA. (F) Apoptotic cell ratio was detected by flow cytometry. 200 µM baicalin increased the apoptotic rate while additional 3-MA administration with baicalin significantly decreased apoptosis. The right upper and right lower quadrants of each figure represent the apoptotic cell ratio. (G, H) The cell viability was measured by CCK-8 assay. A combined baicalin and 3-MA administration significantly restored the cell viability. 3 mM 3-MA did not influence the cell proliferation. (I–L) The protein level of LC3B-II was inhibited by 3-MA treatment. The expression of PARP and Bax was decreased and Bcl-xl was increased when treated with combined 3-MA and baicalin compared with baicalin alone. The relative protein levels of control cells were adjusted to the value of 1. Data were represented as the means ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs control group. #P<0.05 vs baicalin group, ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 vs baicalin group.

Abbreviations: 3-MA, 3-methyladenine; LC3B, light chain 3 beta; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin; PARP, Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase.

However, the relationship between apoptosis and autophagy induced by baicalin was still unclear. 3-MA was commonly regarded as the inhibitor of the autophagosome formation in the early stage. So 200 µM baicalin or 3 mM 3-MA or together was administrated in the U87 and U251 cells to analyze the apoptosis and proliferation. Cell apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry following Annexin V/PI staining and the results showed that apoptotic cell ratio was decreased after baicalin treatment with additional 3-MA while 3-MA alone did not show the effect (Figure 4F). CCK-8 assay revealed that the combination treatment of baicalin and 3-MA restored the cell viability, which was inhibited by baicalin alone (Figure 4G and H). As shown in Figure 4I–L, LC3B-II was inhibited by 3-MA, and decreased Bax and upregulated Bcl-xl were observed after additional 3-MA treatment compared with baicalin alone. Taken together, these observations suggested that autophagy induced by baicalin was partially a prerequisite to cell apoptosis.

Baicalin increases intercellular Ca2+ content in glioblastoma cells

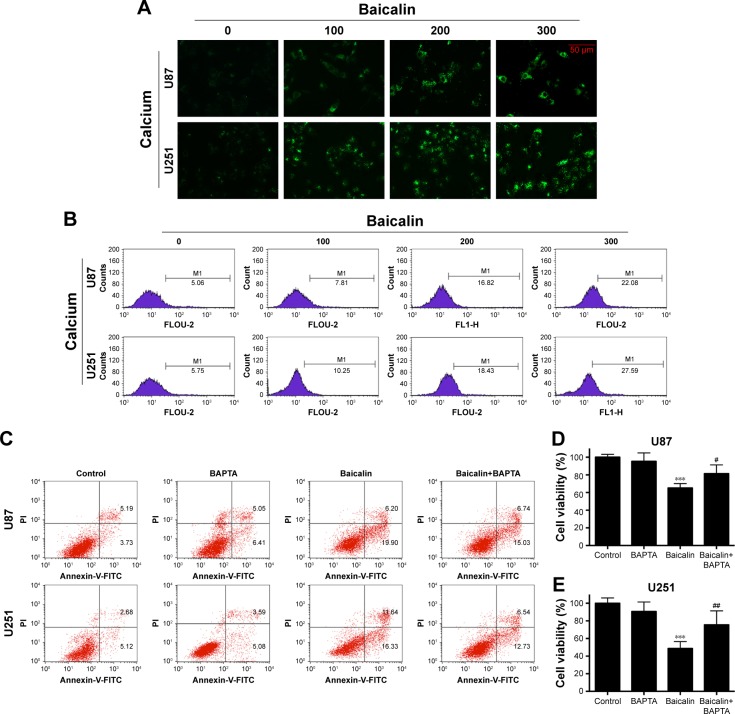

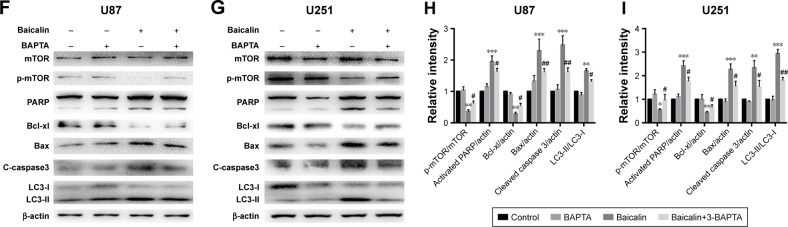

Calcium is a stimulator of both autophagy and apoptosis and whether calcium is the initiator of cytotoxicity ignited by baicalin needs uncovering. We then employed flou-2 fluorescence and flow cytometry to determine the Ca2+ content, U87 and U251 cells showed an increased intercellular Ca2+ after baicalin administration in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5A and B). BAPTA-AM, a kind of Ca2+ chelator that can penetrate cell membrane, was used to chelate inter-cellular free Ca2+ to antagonize the baicalin-induced Ca2+ overload. Cells were pretreated with 5 µM BAPTA for 1 hour and then treated with or without baicalin for 48 hours. Our observations showed that BAPTA pretreatment significantly decreased the apoptotic ratio and restored the cell viability compared with baicalin alone (Figure 5C–E). Autophagy-related protein levels of p-mTOR, LC3B were restored (Figure 5F–I) and suggested that BAPTA pretreatment inhibited the activation of autophagy. Moreover, apoptosis-related protein levels of PARP, Bcl-xl, Bax and cleaved caspase 3 were also restored (Figure 5F–I) and suggested that BAPTA pretreatment suppressed apoptosis induced by baicalin. Hence, the intercellular Ca2+ overload contributed to the autophagy and apoptosis induced by baicalin in U87 and U251 cells. When the free Ca2+ was chelated, autophagy and apoptosis were inhibited.

Figure 5.

Baicalin increases intercellular Ca2+ content.

Notes: (A, B) The intercellular Ca2+ was measured by flou-2 fluorescence and flow cytometry. Baicalin (0, 100, 200, and 300 µM) was added onto cells for 48 hours and then subjected to analysis. The relative level of Ca2+ content was increased, which is represented by the size and brightness of the Ca2+ dots (A) or M1 percentage (B), M1 represents the relative percentage of Ca2+ content, which was defined by positive distribution of Ca2+ in the 0 µM group (the peak value in the 0 µM group was defined as the negative distribution). (C–I) U87 and U251 cells were pretreated with Ca2+ chelator 5 µM BAPTA for 1 hour and then subjected to 0 or 200 µM baicalin for 48 hours. Cells were divided into four groups: Control, BAPTA, Baicalin, and Baicalin+ BAPTA group. (C) The apoptotic cell ratio of the four groups was measured by flow cytometry. The Baicalin+ BAPTA group showed a less apoptotic ratio compared with the Baicalin group. The right upper and right lower quadrants of each figure represent the apoptotic cell ratio. (D, E) CCK-8 assay showed that when pretreated with BAPTA, the cell viability was increased after baicalin treatment compared with baicalin alone group. BAPTA pretreatment did not show cytotoxicity to glioblastoma cells. (F–I) Autophagy-related protein levels of mTOR and LC3B were restored when pretreated with BAPTA compared with baicalin group. Proapoptotic protein levels of PARP, Bax, and cleaved caspase 3 were downregulated while the antiapoptotic protein level of Bcl-xl was upregulated when pretreating with BAPTA. The relative protein levels of control cells were adjusted to the value of 1. Data were represented as the means ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs control group. #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 vs baicalin group.

Abbreviations: BAPTA, 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid; CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin; PARP, Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase.

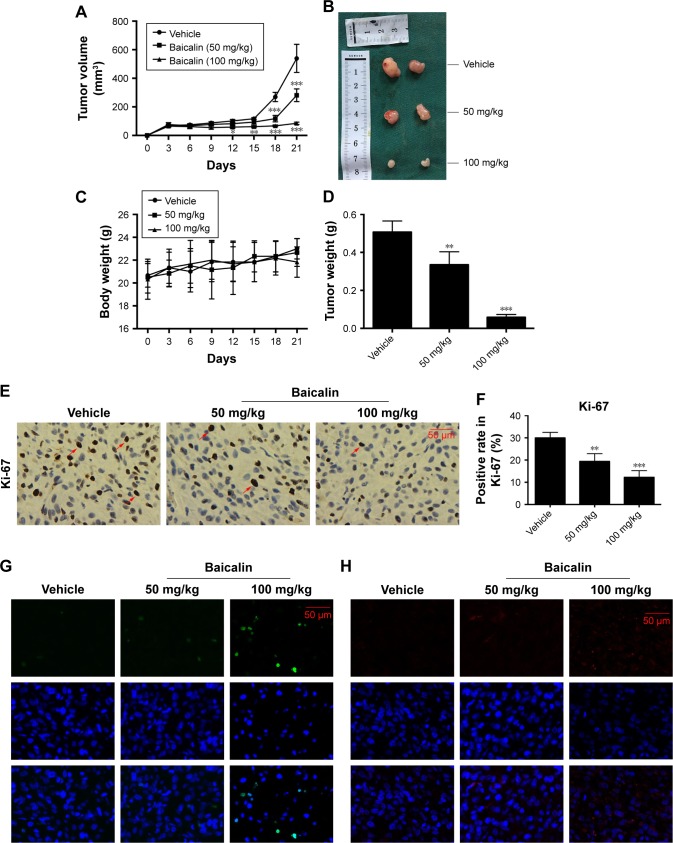

Baicalin inhibits tumor growth in tumor xenografts study

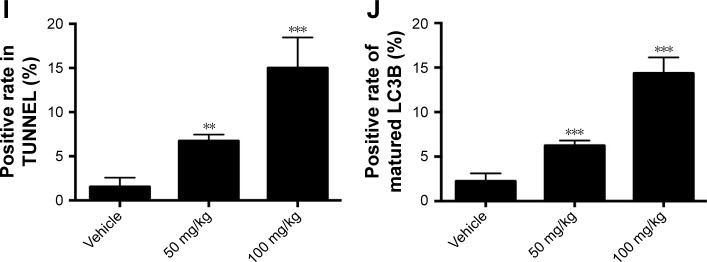

Next, we aimed to determine the effects of baicalin on glioblastoma growth in vivo, the immune-deficient nude mice bearing U87 tumor xenografts were employed. The detailed procedure of the xenograft mouse model was elucidated above. As shown in Figure 6A and B, D, the tumor volume and weight were significantly inhibited by intraperitoneal injection of saline or baicalin (50, 100 mg/kg). The total body weight of nude mice did not change overtly (Figure 6C). The tumors of the xenografts were then fixed by paraffin for section analysis. The immunohistochemical staining showed that baicalin lowered the expression of Ki-67, which serves as a vital biomarker of cancer cell proliferation (Figure 6E and F). In addition, TUNEL and immunofluorescence of LC3B showed that baicalin suppressed apoptosis and autophagy in xenografts (Figure 6G–J). Collectively, these data indicated that baicalin suppressed glioblastoma growth in vivo.

Figure 6.

Baicalin inhibits tumor growth in vivo.

Notes: (A–D) The nude mice bearing U87 tumor xenografts were subjected to saline or baicalin (50 and 100 mg/kg). Baicalin treatment inhibited tumor volume (A and B) and weight (D), but did not affect body weight (C). (E, F) The immunohistochemical staining showed that baicalin suppressed the expression of Ki-67 (positive cells were stained brown in the nuclei); the red arrows point to the ki-67 positive cells. (G, I) TUNEL (green) showed that baicalin increased apoptotic ratio. (H, J) The immunofluorescence of LC3B (red) showed that baicalin increased autophagy in tumor xenografts. Quantification of the number of TUNEL and LC3B-positive cells was analyzed in six independent fields. Data were represented as the means ± SEM of independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs vehicle group.

Abbreviations: LC3B, light chain 3 beta; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling.

Discussion

Glioblastomas are lethal brain tumors characterized by angiogenesis and pseudopalisading necrosis and surgical resection remains the mainstay of treatment for patients with glioblastoma.22 Recent studies on glioblastoma treatment mainly focused on the emerging nanomedicine and therapies that capitalize on cell-specific signaling and immunotherapy targeted on GBM and glioma stem cell (CSC).22–24 Notably, the extracted bioactive regents of Chinese traditional medicine play a vital role in the treatment of glioblastoma.25 In this work, we demonstrated that baicalin repressed the proliferative and invasive rate of human glioblastoma cells in vitro and vivo in dose-dependent manners. Baicalin induced the S-phase blockage and mitochondrial apoptosis; moreover, baicalin triggered the synergistic cytotoxicity of autophagy and apoptosis potentially through the Ca2+-dependent pathway. Interestingly, we found that baicalin induced S-phase arrest in cell cycle only in the U251 cell line, while the U87 cell line did not show the same S-phase inhibition. This discrepancy may be due to the different regulatory mechanism of cell growth inhibition in specific glioblastoma cell type. Further studies are needed to delineate the potential mechanism of the difference in cell cycle arrest in U87 and U251 cells.

ROS is a byproduct of the mitochondrial metabolism. Excessive ROS production may lead to apoptosis with the opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pore, thus releasing cytochrome c to trigger the activation of caspase 3.26 Baicalin is canonically regarded as the ROS scavenger with its phenolic structure capable to transfer electron-free radicals27 as verified by its little toxicity to NHA. In the colon cancer, baicalin in a dose of 40 µM could enhance superoxidase dismutase activity and decrease ROS content.6 However, 250 µM of wogonoside (another flavonoid from Scutellaria) administration to glioblastoma could increase the ROS production and induce mitochondrial apoptosis.25 This possibly attributes to the phenoxy radicals generated by peroxidase that serves as pro-oxidants or the depletion of glutathione content28 or excessive autophagy. Interestingly, we found that baicalin induced mitochondrial apoptosis with the dissipation of mitochondrial membrane potential (∆ψm) potentially via the induction of excessive autophagy. Nevertheless, the role of ROS in the glioblastoma apoptosis caused by baicalin still needs delineation with detail in further study.

An abundant literature reveals that flavonoids such as baicalin and baicalein can induce autophagy in solid tumors.29 In this present study, we demonstrated that baicalin triggered autophagy in a dose-dependent manner. The maturation of LC3B, the increased expression of beclin 1, and the degradation of p62 together indicated that the increased formation of autophagosome. In addition, beclin 1 functions as a tumor suppressor. Knocking down of beclin 1 gene in mice spontaneously develops various cancers, including lung cancer and lymphoma. Its role in the elongation of forming autophagosome with phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate is well elucidated;30 however, beclin 1 contains the BCL2 homology-3 domain, which is capable of binding to the antiapoptotic protein (Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl), thus favoring apoptosis to some extent.31 Collectively, the induction of autophagy may exert an influence on apoptosis with baicalin treatment on glioblastoma and whether autophagy itself could lead to cellular demise is still an issue to be resolved.

When glioblastoma cells suffer from cellular stress such as treatement with temozolomide, autophagy always preserves homeostasis by providing the cell-intrinsic cytoprotection and by changing the microenvironmental conditions, thus leading to chemotherapy resistance and immunosurveillance.12,32 However, in some circumstances, massive autophagy kills cells in a way of self-destruction or, alternatively, hardwiring of autophagy to proapoptotic cascade.12 Here, this study demonstrated that inhibition of autophagy by 3-MA could decrease apoptosis, which indicated that autophagy is prior to apoptosis induced by baicalin to certain extent. Autophagy-related apoptosis is mainly determined by the autophagosome forming in the apoptotic cells and the restoration of cell apoptosis via suppression of autophagy. Taken together with aforementioned mechanisms, these results suggest that baicalin shows cytotoxicity to human glioblastoma cells in a synergistic effect of apoptosis and autophagy.

As previously documented, a mixed phenotype of autophagy and apoptosis could be detected following the treatment of the same stimuli. Intriguingly, the common mechanism underlying baicalin-induced cytotoxicity is still little investigated. Chang et al reported that baicalein (aglycone form of baicalin) induced Ca2+ flux into the cell through the PKC-dependent, 2-APB-sensitive store-operated Ca2+ channels. Moreover, the release of Ca2+ from the ER to cytosol is dependent on the PLC pathway.33 Increase in the free Ca2+ concentrations always leads to aggravated ER stress and the disturbance of mitochondrial membrane potential, thus leading to mitochondrial apoptosis.34 Hoyer-Hansen et al demonstrated that unwanted cytoplasmic Ca2+ led to autophagy via the activation of CaM-dependent kinase kinase-β and inhibition of mTOR.17 In addition, several studies indicated that calpains stimulated by cytoplasmic Ca2+ could significantly conduce autophagy and apoptosis.35 Here, in this study, we found that baicalin treatment in the glioblastoma cells significantly increased the cytosolic Ca2+ content. When pretreated with BAPTA, cells suffered less from baicalin-induced autophagy and apoptosis. However, our work did not go deep into the efflux of intercellular Ca2+ between ER and mitochondria, which were connected by mitochondria-associated membrane.36 Besides, BAPTA pretreatment restored the expression of phosphorylated mTOR without the restoration of phosphorylated AKT (data not shown). This suggests that Ca2+ overload may trigger the AMPK/mTOR pathway instead of PI3K/Akt pathway. Collectively, these clues above lend to the hypothesis that Ca2+ overload is the profound mechanism underlying the autophagy and apoptosis induced by baicalin.

To sum up, the findings in our study showed baicalin suppressed the proliferation, migration, and invasion ability of glioblastoma in a dose-dependent manner and the synergistic effect of apoptosis and autophagy induced by baicalin contribute to its cytotoxicity to human glioblastoma cells. The strong evidence proves that baicalin, the natural extracted flavonoid, is a promising therapeutic agent for the treatment of glioblastoma.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No 81402072 and No 81672503) and the National Natural Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars of China (No 81702484).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Sanai N, Berger MS. Surgical oncology for gliomas: the state of the art. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(2):112–125. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilbert MR, Dignam JJ, Armstrong TS, Colman H, et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):699–708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li-Weber M. New therapeutic aspects of flavones: the anticancer properties of Scutellaria and its main active constituents Wogonin, Baicalein and Baicalin. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35(1):57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang DY, Wu J, Ye F, et al. Inhibition of cancer cell proliferation and prostaglandin E2 synthesis by Scutellaria baicalensis. Cancer Res. 2003;63(14):4037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou T, Zhang A, Kuang G, et al. Baicalin inhibits the metastasis of highly aggressive breast cancer cells by reversing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition by targeting β-catenin signaling. Oncol Rep. 2017;38(6):3599. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.6011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Z, Ma L, Su M, et al. Baicalin induces cellular senescence in human colon cancer cells via upregulation of DEPP and the activation of Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(2):217. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0223-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen H, Gao Y, Wu J, et al. Exploring therapeutic potentials of baicalin and its aglycone baicalein for hematological malignancies. Cancer Lett. 2014;354(1):5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan HY, Wang N, Man K, et al. Autophagy-induced RelB/p52 activation mediates tumour-associated macrophage repolarisation and suppression of hepatocellular carcinoma by natural compound baicalin. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1942. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang SF, Wu MY, Cai CZ, Li M, Lu JH. Autophagy modulators from traditional Chinese medicine: mechanisms and therapeutic potentials for cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;194:861–876. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.10.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galluzzi L, Baehrecke EH, Ballabio A, et al. Molecular definitions of autophagy and related processes. Embo J. 2017;36(13):1811–1836. doi: 10.15252/embj.201796697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rybstein MD, Bravo-San Pedro JM, Kroemer G, Galluzzi L. The autophagic network and cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20(3):243–251. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maiuri MC, Zalckvar E, Kimchi A, Kroemer G. Self-eating and self-killing: crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(9):741–752. doi: 10.1038/nrm2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thorpe LM, Yuzugullu H, Zhao JJ. PI3K in cancer: divergent roles of isoforms, modes of activation and therapeutic targeting. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(1):7–24. doi: 10.1038/nrc3860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li X, Zou K, Gou J, et al. Effect of baicalin-copper on the induction of apoptosis in human hepatoblastoma cancer HepG2 cells. Med Oncol. 2015;32(3):72. doi: 10.1007/s12032-015-0527-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tajeddine N. How do reactive oxygen species and calcium trigger mitochondrial membrane permeabilisation? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1860(6):1079–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rizzuto R, Pozzan T. Microdomains of intracellular Ca2+: molecular determinants and functional consequences. Physiol Rev. 2006;86(1):369–408. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00004.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Høyer-Hansen M, Bastholm L, Szyniarowski P, et al. Control of macroautophagy by calcium, calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase-beta, and Bcl-2. Mol Cell. 2007;25(2):193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang Y, Xie X, Chen L, et al. Bioactive polycyclic quinones from marine Streptomyces sp. 182SMLY. Mar Drugs. 2016;14(1):10. doi: 10.3390/md14010010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, Wang H, Sun K, et al. Chrysin suppresses proliferation, migration, and invasion in glioblastoma cell lines via mediating the ERK/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2018;12:721–733. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S160020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding H, Wang H, Zhu L, Wei W. Ursolic acid ameliorates early brain injury after experimental traumatic brain injury in mice by activating the Nrf2 pathway. Neurochem Res. 2017;42(2):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11064-016-2077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Itoh T, Ono A, Kawaguchi K, et al. Phytol isolated from watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) sprouts induces cell death in human T-lymphoid cell line Jurkat cells via S-phase cell cycle arrest. Food Chem Toxicol. 2018;115:425–435. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin X, Kim LJY, Wu Q, et al. Targeting glioma stem cells through combined BMI1 and EZH2 inhibition. Nat Med. 2017;23(11):1352–1361. doi: 10.1038/nm.4415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mai WX, Gosa L, Daniels VW, et al. Cytoplasmic p53 couples oncogene-driven glucose metabolism to apoptosis and is a therapeutic target in glioblastoma. Nat Med. 2017;23(11):1342–1351. doi: 10.1038/nm.4418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ozdemir-Kaynak E, Qutub AA, Yesil-Celiktas O. Advances in glioblastoma multiforme treatment: new models for nanoparticle therapy. Front Physiol. 2018;9:170. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang L, Wang H, Cong Z, et al. Wogonoside induces autophagy-related apoptosis in human glioblastoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2014;32(3):1179–1187. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshida H, Kong YY, Yoshida R, et al. Apaf1 is required for mitochondrial pathways of apoptosis and brain development. Cell. 1998;94(6):739–750. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81733-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Havsteen BH. The biochemistry and medical significance of the flavonoids. Pharmacol Ther. 2002;96(2–3):67–202. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00298-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Modriansky M, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, et al. Anti-/pro-oxidant effects of phenolic compounds in cells: are colchicine metabolites chain-breaking antioxidants? Toxicology. 2002;177(1):105–117. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gong WY, Zhao ZX, Liu BJ, Lu LW, Dong JC. Exploring the chemo-preventive properties and perspectives of baicalin and its aglycone baicalein in solid tumors. Eur J Med Chem. 2017;126:844–852. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim J, Kim YC, Fang C, et al. Differential regulation of distinct Vps34 complexes by AMPK in nutrient stress and autophagy. Cell. 2013;152(1–2):290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elgendy M, Ciro M, Abdel-Aziz AK, et al. Beclin 1 restrains tumorigenesis through Mcl-1 destabilization in an autophagy-independent reciprocal manner. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5637. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levy JMM, Towers CG, Thorburn A. Targeting autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17(9):528. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang HT, Chou CT, Kuo DH, et al. The Mechanism of Ca(2+) movement in the involvement of baicalein-induced cytotoxicity in ZR-75-1 human breast cancer cells. J Nat Prod. 2015;78(7):1624–1634. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orrenius S, Mcconkey DJ, Bellomo G, Nicotera P. Role of Ca2+ in toxic cell killing. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1989;10:281–285. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(89)90029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yousefi S, Perozzo R, Schmid I, et al. Calpain-mediated cleavage of Atg5 switches autophagy to apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8(10):1124–1132. doi: 10.1038/ncb1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fujimoto M, Hayashi T. New insights into the role of mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2011;292:73–117. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386033-0.00002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]