Abstract

Objective

To study the association between neighbourhood socioeconomic status and diabetes prevalence, incidence, and control in the entire population of northeastern Madrid, Spain.

Setting

Electronic health records of the primary-care system in four districts of Madrid (Spain).

Participants

269 942 people aged 40 or older, followed from 2013 to 2014.

Exposure

Neighbourhoodsocioeconomic status (NSES), measured using a composite index of seven indicators from four domains of education, wealth, occupation and living conditions.

Primary outcome measures

Diagnosis of diabetes based on ICPC-2 codes and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c %).

Results

In regression analyses adjusted by age and sex and compared with individuals living in low NSES neighbourhoods, men living in medium and high NSES neighbourhoods had 10% (95% CI: 6% to 15%) and 29% (95% CI: 25% to 32%) lower prevalence of diabetes, while women had 27% (95% CI: 23% to 30%) and 50% (95% CI: 47% to 52%) lower prevalence of diabetes. Moreover, the hazard of diabetes in men living in medium and high NSES neighbourhoods was 13% (95% CI: 1% to 23%) and 20% (95% CI: 9% to 29%) lower, while the hazard of diabetes in women living in medium and high NSES neighbourhoods was 17% (95% CI: 3% to 29%) and 31% (95% CI: 20% to 41%) lower. Individuals living in medium and high SES neighbourhoods had 8% (95% CI: 2% to 15%) and 15% (95% CI: 9% to 21%) lower prevalence of lack of diabetes control, and a decrease in average HbA1c % of 0.05 (95% CI: 0.01 to 0.10) and 0.11 (95% CI: 0.06 to 0.15).

Conclusions

Diabetes prevalence, incidence and lack of control increased with decreasing NSES in a southern European city. Future studies should provide mechanistic insights and targets for intervention to address this health inequity.

Keywords: social epidemiology, social inequalities, spain, record linkage, diabetes, neighborhoods

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We study the entire population of an area of a very large city (Madrid) where almost 600 000 people live, resulting in a very large sample size and decreased concerns for selection bias as compared to regular cohort studies or surveys.

The diagnosis of diabetes in our electronic health records has been validated before and shown to have a very high validity with a kappa of 0.99, but we cannot achieve the level of standardisation of measurements of cohort studies.

We use HbA1c, which is a robust measure of diabetes control and is the standard of care in clinical practice.

We used an exposure constructed from publicly available indicators, increasing the replicability of our findings and the applicability to other health outcomes, but restricting our capacity to build a complex exposure that may capture socioeconomic status better.

The available data for individual level confounders were restricted to basic socio-demographics (age and sex), which opens the possibility for residual confounding in our inferences (especially individual level socioeconomic status).

Introduction

The burden of diabetes has seen a large increase in Western countries in recent decades.1 Diabetes-attributable costs in the European Union have been estimated to be over $100 billion per year and are predicted to continue increasing in the following decades.2 Population preventive strategies are needed to decrease this burden,3 taking into consideration mass influences that differ across populations.3

Among these mass influences are neighbourhood characteristics. A large body of literature has explored contextual socioeconomic influences on health. In particular, the association between neighbourhood socioeconomic status (NSES) and several measures of diabetes (prevalence, incidence or control) is robust and has been replicated in the USA,4–10 other Anglo-Saxon countries11–19 and northern and central Europe20–26 including in experimental or quasi-experimental settings.21 27 Nonetheless, these influences have received scant attention in southern Europe.28 Moreover, previous studies have shown a strong social gradient in diabetes mortality in Spain, which warrants further mechanistic insights into its causes.29 Recent studies have shown that segregation patterns and neighbourhood selection phenomena is changing in southern Europe,30 necessitating a study of the health outcomes associated with these changes.

Finally, many of the studies outlined above use data from research-driven cohort studies. While these types of studies have the advantage of standardised and high-quality data collection, they may suffer from a number of biases derived from a non-random sampling of the study participants.31 In particular, the role that context plays in determining selection into a study may be particularly relevant in studies on the effect of context on health.31 With electronic health records (EHR) in a health system with universal health coverage, these drawbacks may be overcome by avoiding the necessity for sampling altogether.

Taking the above into consideration, we studied the association between NSES and diabetes prevalence, incidence and control in an electronic health record-based cohort of the entire population of northeastern Madrid that includes data on more than 640 000 people.

Methods

Study setting

This study was conducted within the HeartHealthyHoods project (www.hhhproject.eu) in the city of Madrid, Spain.32 We took data for 2013 and 2014 from all healthcare centres in four districts of the city of Madrid, all belonging to the same health district. These four districts contain around 20% of the total population of Madrid and are representative of the rest of the city of Madrid (online appendix figure 1). Our unit of analysis is the census section (n=427), which is the smallest area for which the census collects data and has around 1200 people (range: 583 to 3865). Individual-level data were obtained from EHR including 640 217 individuals registered in any health centre of the area. These EHR contain data on patient age, sex, residential location, clinical diagnoses and laboratory values (lipids and HbA1c).

bmjopen-2017-021143supp001.pdf (427.2KB, pdf)

Since this screening for cardiovascular risk factors is limited to people 40 years and older,32 we restricted our dataset to people born after January 1, 1973 (aged 40 or older by 2013). Our final study sample was composed of 270 660 individuals, of which 23 908 had a diagnosis of diabetes. Primary care EHR includes 99.5% of the individuals living in the area per the census.32

Neighbourhood socioeconomic status

The main exposure of this study was NSES. To measure NSES, we considered the four domains of the Spanish Commission to Reduce Health Inequalities33: education, wealth, occupation and living conditions. To search for indicators to measure these four domains, we explored all available data sources, to our knowledge, on social, economic and contextual factors in Madrid, Spain. We looked for readily available indicators (to ease replicability) that were measured at the neighbourhood or census section level (to improve granularity) and that were available for several years (to allow for further studies looking at longitudinal changes). After this process we selected seven indicators that represent the four domains: education—(1) primary education (% people above 25 years of age with primary studies or below), (2) university education (% people above 25 years of age with university education or above); wealth—(3) average housing prices (per sq. m); occupation—(4) part-time employment (% workers in part-time jobs), (5) temporary employment (% workers in temporary jobs), (6) manual occupational class (% workers in manual or unqualified jobs); and living conditions—(7) unemployment rate (% registered unemployed individuals/people aged 16 to 64). Indicator data were obtained from the Padrón (a continuous and universal census collected for administrative purposes), the social security and employment services registries and the IDEALISTA report (a report from a large real estate corporation in Spain). All data were available by January 2013. The online resource contains a detailed description of the operationalisation of indicators.

We computed a weighted index of the seven indicators by: (1) making the directionality of the associations consistent, by reversing some of the indicators (primary education, part-time employment, temporary employment, manual occupational class and unemployment rate) so that all indicators had a consistent association with the final index; (2) for each indicator, we centred by the mean and divided it by the SD in order to obtain a Z-score of each indicator; (3) in each domain, we averaged the Z-score of each indicator, resulting in a Z-score for each domain (education, wealth, occupation and living conditions) and (4) finally, we calculated the composite index of NSES by averaging the Z-score of each of the four domains. This composite NSES index was then operationalised in separate analyses as a categorical variable (NSES in tertiles) or as a continuous variable.

Diabetes prevalence, incidence and control

Diabetes diagnoses were extracted from the EHR for all individuals, as recorded by primary care physicians during their usual clinical practice. A type-2 diabetes diagnosis was defined using the T90 diagnosis code of the ICPC-2 (‘diabetes non-insulin dependent’). A previous study has validated the diagnosis of diabetes in this dataset with a kappa of 0.99, with high sensitivity (99.5%) and specificity (99.5%).34 Prevalent cases were defined as diabetes diagnoses dated before 1 January 2013. Incident cases were those occurring from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2014 in people free of diabetes by baseline (1 January 2013). We operationalised lack of diabetes control as either a dichotomous variable (HbA1c>=7%) or a continuous variable (HbA1c %). If more than one value of HbA1c was available, we used the last available measurement of the year.

Statistical methods

The overall goal of this analysis is to study the association between NSES and diabetes prevalence, incidence and control. We computed descriptive statistics by tertile of NSES.

To study the association between NSES and diabetes prevalence or lack of control (binary indicator) we used a log-binomial regression model with robust standard errors clustered at the census section level using a sandwich Huber–White estimator. These models were adjusted for age (in five categories; 40 to 49, 50 to 59, 60 to 69, 70 to 79 and 80 and older) and sex. Continuous HbA1c (for diabetes control) was examined using a linear regression with robust standard errors clustered at the census section level using a sandwich Huber–White estimator. Around 21% of the sample that had prevalent diabetes had no HbA1c % measured in 2013 or 2014. To assess whether this missing data affected our inferences, we did a sensitivity analysis using a conditional mean imputation of HbA1c % in people with diabetes. In this model, we predicted the HbA1c % value using age, sex, healthcare centre, NSES index and diagnosis of other cardiovascular risk factors or conditions (hypertension, dyslipidaemia, prevalent cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease and retinopathy). We then compared the point estimates of the association between prevalent lack of control and average HbA1c % obtained with and without conditional mean imputation.

In the analysis of diabetes incidence, each individual entered the sample on 1 January 2013 and exited on the date of diabetes diagnosis (outcome), date of death (censored), date of moving out of a health centre in the area (censored) or study end by 31 December 2014 (administrative censoring). We used Kaplan–Meier survival estimates to explore the differences in the hazard of diabetes incidence by NSES tertile. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the adjusted association, with clustered standard errors on the census section. Since we censored individuals at death, a potential competing risk, our estimates from the model are analogous to cause-specific hazard ratios, and can therefore be interpreted as the increase in the hazard of diabetes if people that do not die. We checked the proportionality of hazards assumption by plotting Schoenfeld residuals and by checking their trend over time.35

To graphically display the association between the exposure and the outcome variables, we also modelled the associations above using restricted cubic splines with four knots in the percentiles recommended by Harrell.36 A previous report in the Spanish setting highlighted a significant interaction by sex of contextual socioeconomic status and diabetes,28 so we explored whether this interaction existed in our analysis and displayed stratified results if this was the case. All analyses were conducted in R V.3.3.0 (R Software Foundation).

Results

Study population

Table 1 shows a description of the study population by tertile of NSES and in the total population. The total sample size was 269 942 people, with around 25%, 30% and 45% of the population living in low, medium and high NSES areas. Overall, the median age was 56.5 (IQR=47.4 to 69.8) and 54.9% of the population were women. Of this, 8.8% of the population older than 40 years of age had diabetes, 1.0% developed diabetes during follow-up and the average HbA1c in diabetic people was 6.7 (IQR=6.2 to 7.5). Thirty-nine percent of all diabetic people had uncontrolled diabetes (HbA1c equal or above 7%). Stratifying the population by tertile of NSES revealed that younger people lived in neighbourhoods with higher SES. The prevalence of diabetes decreased sharply with NSES (11.9% in the lowest NSES, 9.6% in the medium NSES and 6.5% in the highest NSES), and the incidence of diabetes followed a similar gradient by NSES (1.3%, 1.1% and 0.9% in the lowest, medium and highest NSES areas).

Table 1.

Study population by 1 January 2013

| Variable | Total | Tertile 1 (Lowest NSES) |

Tertile 2 (Mid NSES) |

Tertile 3 (High NSES) |

P values* |

| Sample Size (N) | 2 69 942 | 68 369 | 81 072 | 1 20 501 | |

| Median Age (IQR) | 56.5 (47.4;69.8) | 58.6 (48.3;74.5) | 58.1 (48.0;71.1) | 54.7 (46.6;66.9) | <0.001 |

| % Men | 45.1% | 44.6% | 44.2% | 45.9% | <0.001 |

| % Women | 54.9% | 55.4% | 55.8% | 54.1% | |

| % Death during follow-up | 1.2% | 1.4% | 1.3% | 1.0% | <0.001 |

| % Moved during follow-up | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.673 |

| % With prevalent diabetes | 8.8% | 11.9% | 9.6% | 6.5% | <0.001 |

| % With incident diabetes† | 1.0% | 1.3% | 1.1% | 0.9% | <0.001 |

| Median HbA1c (IQR) | 6.7 (6.2;7.5) | 6.7 (6.2;7.5) | 6.7 (6.2;7.5) | 6.7 (6.2;7.4) | <0.001 |

| HbA1c>=7% | 38.8% | 40.5% | 38.7% | 37.1% | 0.237 |

| HbA1c<5% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.285 |

| HbA1c 5%–6.5% | 41.1% | 40.0% | 40.5% | 42.7% | |

| HbA1c 6.5%–7% | 20.1% | 19.4% | 20.6% | 20.3% | |

| HbA1c 7%–9% | 32.4% | 34.0% | 32.2% | 30.9% | |

| HbA1c>9% | 6.1% | 6.3% | 6.3% | 5.7% | |

| Primary education, % (IQR) | 24.6% (15.1;32.2) | 36.3% (30.7;40.3) | 24.7% (20.8;27.9) | 11.6% (7.1;19.5) | <0.001 |

| University education, % (IQR) | 20.8% (13.0;33.7) | 10.2% (7.4;13.0) | 20.8% (16.8;24.7) | 40.1% (29.9;52.5) | <0.001 |

| Unemployment rate, % (IQR) | 12.6% (10.6;13.8) | 13.8% (13.8;16.4) | 12.6% (12.0;12.7) | 8.9% (7.8;10.6) | <0.001 |

| Part-time workers, % (IQR) | 23.4% (18.7;25.9) | 26.7% (24.8;26.8) | 23.4% (22.4;25.9) | 16.5% (12.7;19.4) | <0.001 |

| Temporary workers, % (IQR) | 19.0% (17.3;20.9) | 20.9% (20.4;21.5) | 20.4% (18.9;20.9) | 16.7% (13.8;18.2) | <0.001 |

| Manual class, % (IQR) | 37.1% (27.4;40.0) | 40.3% (40.0;43.1) | 37.1% (36.2;40.0) | 22.4% (17.4;30.2) | <0.001 |

| Property value, EUR/m2(IQR) | 2286.0 (1975.0;2659.0) | 1776.0 (1561.0;1971.0) | 2243.0 (2128.0;2398.0) | 2832.0 (2608.0;3382.0) | <0.001 |

| SES index (IQR) | 0.0 (-0.6;0.6) | −0.8 (-1.2;−0.6) | −0.2 (-0.3;0.1) | 1.0 (0.6;1.6) | <0.001 |

*P value -values for continuous individual-level characteristics were computed using a clustered Somers’ D comparison of medians; P-values for categorical individual-level characteristics were computed using Donner’s χ2 adjusted for clustered data. P-values for contextual characteristics were conducted at the neighbourhood level using a Kruskal-Wallis test for the comparison of medians.

†Incident diabetes refers to new diagnoses of diabetes in 2013 or 2014 in people free of diabetes at baseline.

NSES, neighbourhood socioeconomic status index.

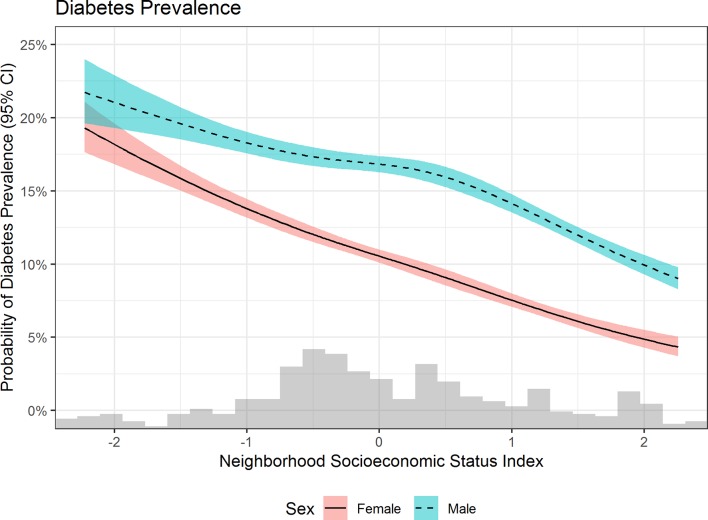

NSES and diabetes prevalence

Table 2 shows the association between NSES and diabetes prevalence, control and incidence. Diabetes prevalence was associated in a dose–response manner to NSES. This association was significantly stronger in women as compared with men (P value for the interaction <0.001). In particular, compared with men living in low NSES neighbourhoods, those living in medium NSES neighbourhoods had 8% lower prevalence of having diabetes (PR=0.92, 95% CI 0.89 to 0.96), while those living in the highest NSES neighbourhoods had 24% lower prevalence of diabetes (PR=0.76, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.80). In the case of women, those living in medium and high NSES neighbourhoods had 24% and 46% lower prevalence of diabetes, respectively, as compared with those living low NSES neighbourhoods (PR=0.76, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.79, and PR=0.54, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.57). These associations were consistent in models looking at continuous NSES: a one SD increase in NSES was associated with 14% and 26% lower prevalence of diabetes in men and women, respectively (PR=0.86, 95% CI 0.84 to 0.87, PR=0.74, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.75). Figure 1 shows the association using continuous NSES with restricted cubic splines, where the steeper pattern for women is evident.

Table 2.

Association of neighbourhood socioeconomic status (NSES) and diabetes outcomes

| Variable | Total | Men | Women | |||

| Diabetes Prevalence | ||||||

| PR (95% CI) | P values | PR (95% CI) | P values | PR (95% CI) | P values | |

| Tertile 1 of NSES (Low) | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | |||

| Tertile 2 of NSES (Middle) | 0.84 (0.82 to 0.87) | <0.001 | 0.92 (0.89 to 0.96) | <0.001 | 0.76 (0.73 to 0.79) | <0.001 |

| Tertile 3 of NSES (High) | 0.66 (0.64 to 0.68) | <0.001 | 0.76 (0.74 to 0.80) | <0.001 | 0.54 (0.52 to 0.57) | <0.001 |

| Continuous NSES | 0.80 (0.79 to 0.81) | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.84 to 0.87) | <0.001 | 0.74 (0.72 to 0.75) | <0.001 |

| Variable | Lack of Diabetes Control (HbA1c> =7%) | |||||

| PR (95% CI) | P values | PR (95% CI) | P values | PR (95% CI) | P values | |

| Tertile 1 of NSES (Low) | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | |||

| Tertile 2 of NSES (Middle) | 0.95 (0.91 to 0.99) | 0.014 | 0.94 (0.88 to 0.99) | 0.033 | 0.96 (0.90 to 1.02) | 0.158 |

| Tertile 3 of NSES (High) | 0.91 (0.87 to 0.95) | <0.001 | 0.88 (0.83 to 0.93) | <0.001 | 0.95 (0.89 to 1.01) | 0.117 |

| Continuous NSES | 0.96 (0.94 to 0.98) | <0.001 | 0.95 (0.93 to 0.98) | <0.001 | 0.97 (0.95 to 1.00) | 0.07 |

| Variable | Lack of Diabetes Control (Continuous HbA1c %) | |||||

| Beta (95% CI) | P values | Beta (95% CI) | P values | Beta (95% CI) | P values | |

| Tertile 1 of NSES (Low) | 0 (Ref.) | 0 (Ref.) | 0 (Ref.) | |||

| Tertile 2 of NSES (Middle) | −0.05 (-0.10 to −0.01) | 0.021 | −0.07 (-0.13 to −0.01) | 0.021 | −0.03 (-0.09 to 0.03) | 0.31 |

| Tertile 3 of NSES (High) | −0.11 (-0.15 to −0.06) | <0.001 | −0.13 (-0.19 to −0.07) | <0.001 | −0.08 (-0.14 to −0.02) | 0.014 |

| Continuous NSES | −0.04 (-0.06 to −0.02) | <0.001 | −0.05 (-0.07 to −0.02) | <0.001 | −0.03 (-0.06 to −0.01) | 0.011 |

| Variable | Diabetes Incidence | |||||

| HR (95% CI) | P values | HR (95% CI) | P values | HR (95% CI) | P values | |

| Tertile 1 of NSES (Low) | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | |||

| Tertile 2 of NSES (Middle) | 0.85 (0.77 to 0.95) | 0.003 | 0.87 (0.77 to 0.99) | 0.041 | 0.83 (0.71 to 0.97) | 0.021 |

| Tertile 3 of NSES (High) | 0.75 (0.68 to 0.83) | <0.001 | 0.80 (0.71 to 0.91) | <0.001 | 0.69 (0.59 to 0.80) | <0.001 |

| Continuous NSES | 0.86 (0.83 to 0.90) | <0.001 | 0.90 (0.85 to 0.94) | <0.001 | 0.82 (0.77 to 0.87) | <0.001 |

*Models adjusted by age, sex and year and clustered on the census section. Results for diabetes prevalence and lack of diabetes control (binary) are shown in prevalence ratios (95% CI); results for lack of diabetes control (continuous) are presented as changes in average HbA1c % (95% CI); results for diabetes incidence are presented as hazard ratios (95% CI).

Figure 1.

Estimated diabetes prevalence by levels of neighbourhood socioeconomic status index.

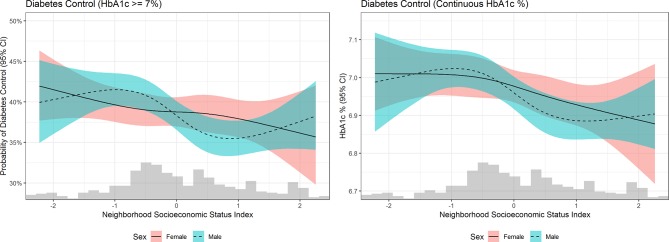

NSES and diabetes control

Table 2 also shows the association between NSES and diabetes control, operationalised as a dichotomous variable (lack of diabetes control, or HbA1c>=7%) or a continuous variable (HbA1c %). There was no significant interaction by sex in the NSES and diabetes control (P value for the interaction=0.219 and 0.358 in the dichotomous and continuous model). As compared with people with diabetes living in the lowest NSES neighbourhoods, those living in medium NSES areas had 5% lower prevalence of lack of diabetes control (PR=0.95, 95% CI 0.91 to 0.99), while those living in the highest NSES areas had 9% lower prevalence of lack of diabetes control (PR=0.91, 95% CI 0.87 to 0.95). Moreover, a one SD increase in NSES was associated with 4% lower prevalence of lack of diabetes control (PR=0.96, 95% CI 0.94 to 0.98). These associations were maintained when looking at continuous HbA1c: diabetic people living in medium and high NSES had a lower average HbA1c % (see table 2). Figure 2 shows the prevalence of lack of diabetes control and average HbA1c levels across levels of NSES using restricted cubic splines, showing a linear decrease both in lack of control and in average HbA1c % with increasing NSES. In the sensitivity analysis using conditional mean imputation of HbA1c %, we found no change in our inferences after accounting for missing HbA1c % (see online appendix figure 2).

Figure 2.

Estimated diabetes control by levels of neighbourhood socioeconomic status.

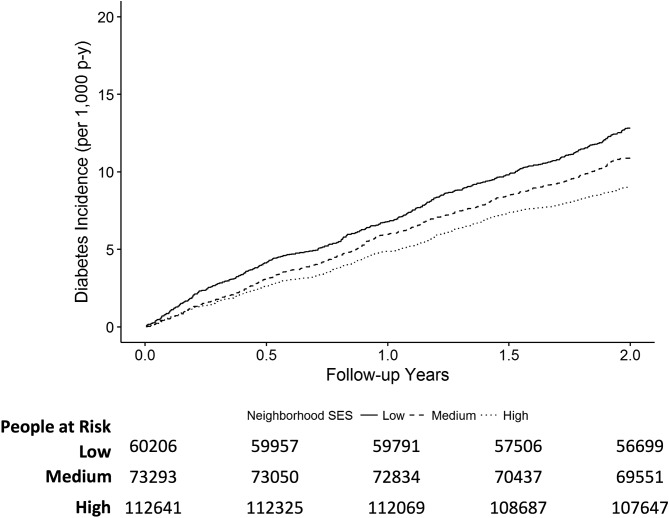

NSES and diabetes incidence

Overall, at 1 and 2 years of follow-up, the diabetes incidence was 5.7 per 1000 and 10.5 per 1000. Figure 3 shows the Kaplan–Meier estimate of diabetes incidence by tertile of NSES, showing a social gradient in diabetes incidence (lower NSES corresponding to higher diabetes incidence, P<0.001). Table 2 also shows the results of the adjusted Cox proportional hazards models. We found a significant interaction by sex (P value for interaction=0.004). The hazard of diabetes incidence in men living in medium and high NSES neighbourhoods was 13% and 20% lower compared with men living in low NSES neighbourhoods (HR=0.87, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.99, and HR=0.80, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.91). A stronger association was observed in women, as the hazard of diabetes incidence in women living in medium and high NSES neighbourhoods was 17% and 31% lower compared with women living in low NSES neighbourhoods (HR=0.83, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.97, and HR=0.69, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.80). These associations were consistent in models looking at continuous NSES: a one SD increase in NSES was associated with a 10% and 18% decrease in the hazard of incident diabetes in men and women, respectively (HR=0.90, 95% CI 0.85 to 0.94, and HR=0.82, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.87). We tested the assumption of proportionality of hazards and found no evidence to reject the null hypothesis of proportionality (P value for the global chi2-test=0.604 for the unadjusted model, and 0.365 for the fully adjusted model).

Figure 3.

Adjusted Kaplan-Meier survival curve of diabetes incidence by neighbourhood socioeconomic status (SES). Results predicted from models adjusted by age, sex and year and clustered on the census section. For prediction purposes age was set to the third category (60 to 70 years of age).

Discussion

This study has shown a strong association between NSES and diabetes burden. In particular, there is a dose–response association: as NSES increases, diabetes prevalence, lack of control and incidence decrease in a linear fashion. This association is seen for both a categorical (tertiles) and a continuous operationalisation of the exposure. There seems to be an interaction by sex in the association with diabetes prevalence and incidence, which is stronger in women as compared to men.

Previous studies have shown analogous results to ours. A report by Larrañaga found an increase in the prevalence of diabetes in more deprived neighbourhoods in the Basque Country (northern Spain), using a sample of primary care practices,28 displaying a similar interaction by sex as our study. Other studies using EHR in other countries have found significant associations between area-level poverty, deprivation or socioeconomic status and diabetes prevalence, incidence and control. A study by Cox15 using EHR from a Scottish region found increased diabetes prevalence in more deprived areas, as measured using the Carstair index of deprivation. Studies by Mezuk20 and Sundquist26 showed a significant increase in diabetes incidence in the Swedish population living in medium and high deprivation neighbourhoods, measured using four indicators of NSES. Several studies in the UK,12 16 18 19 USA10 and Israel37 have studied the association of NSES with diabetes control as measured by HbA1c % in EHR, finding a consistent gradient similar to ours (lower NSES associated with lower likelihood of control or higher HbA1c %). Other studies using data from cross-sectional surveys or cohort studies, but with similar spatial units as ours have also found significant associations in the USA,4–6 9 France22 and Sweden.23 Our study is the first in Spain (and to our knowledge in southern Europe) to show an association between NSES and diabetes control.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Our study has several strengths. First, we study the entire population of an area of a very large city (Madrid) where almost 600 000 people live.32 This results in a very large sample size and decreased concerns for selection bias as compared to regular cohort studies or surveys.31 Second, the diagnosis of diabetes in our EHR has been validated before and shown to have a very high validity with a kappa of 0.99.34 Third, HbA1c represents a robust measure of diabetes control and is the standard of care in clinical practice. Finally, we used an exposure constructed from publicly available indicators, increasing the replicability of our findings and the applicability to other health outcomes. Our study also has some limitations. First and foremost, while the validity of our measures of diabetes prevalence, incidence and control is high,34 we cannot achieve the standardisation of measurements that cohort studies do. While there exists the possibility of differential measurement error, we have no reason to suspect that the accuracy of the measure of diabetes prevalence varies by socioeconomic status, given that Spain has a universal healthcare system. Second, while our exposure is built from publicly available indicators, this also restricts our capacity to build a complex exposure that may capture socioeconomic status better. Third, the available data for individual level confounders were restricted to basic socio-demographic variables, age and sex, which opens the possibility for residual confounding in our inferences. In particular, we do not have data on individual-level socioeconomic status. Unmeasured confounding by neighbourhood selection may be an important source of bias in our study. However, whether adjusting for individual-level socioeconomic status brings estimates closer to the truth or induces overadjustment may depend on the level of social mobility of each country.38 Last, the generalisability of these results to other Spanish or European cities may be limited for cities that do not have similar segregation patterns. Recent research has shown increased segregation in Madrid, with levels similar to London.30

The implications of our study are several. As this is the first study, to our knowledge, to show strong contextual gradients in diabetes burden in Spain, we believe these findings should be incorporated in the National Health Equity Strategy. Research wise, this study opens the possibility to study the connection between contextual factors (food, physical activity, tobacco and alcohol environment) and diabetes. Future studies may consider providing specific mechanistic insights into the contextual determinants of diabetes in southern Europe. For example, Auchincloss and Christine have reported over several studies39 40 increased prevalence and incidence of diabetes with lower availability of healthy foods or physical-activity-promoting resources, but research on these mechanistic pathways is lacking in Spain and southern Europe in general. In particular, the association of contextual socioeconomic status and unhealthy food environments has not been thoroughly replicated in Europe and may actually follow a different gradient.41 We have previously shown that neighbourhoods in Madrid with improving socioeconomic status indicators have an increased proportion of supermarkets and decreased proportion of fruit and vegetable stores,42 a contextual change undesired by neighbours and perceived as not conducive to better diets.43 44 We have also previously shown that walkability may follow an inverse social gradient in Madrid45 (worse walkability in higher NSES areas), but that this association may not hold in gentrifying areas.45 In summary, understanding the mechanisms (and therefore potential intervention targets) linking NSES to diabetes may require studies that take into consideration changes in both the exposure and the outcome side.

WHO has identified social determinants as underlying many of the health inequities observed within countries,46 and resulting strategies to ameliorate social determinants through a system change are under way in countries including Spain.47 For diabetes, an unhealthy diet, lack of physical activity, and subsequent obesity are some of the main modifiable risk factors that are adversely impacted by social determinants. Understanding the contextual contributors to the social patterning of diabetes we have described in this study can offer opportunities for prevention through structural changes.48 Nonetheless, these strategies need not be restricted to macro-level changes. Globally, intensive lifestyle diabetes prevention programmes49 present an evidence-based opportunity that is not reliant on environmental structural change. Diabetes prevention programmes using this model have proven effective in reducing diabetes incidence in persons in lower income communities in the USA.50 There is also initial evidence that patient diabetes self-management programmes focused on barriers to care and social determinants can improve diabetes self-management skills, health behaviours and HbA1c in low-income patients and communities.51 52 For reference, our results regarding the 2-year incidence of diabetes in high socioeconomic status as compared with low socioeconomic status areas (HR=0.80 and 0.69 in men and women, respectively) have an association with reduced diabetes incidence similar to a 1.2 kg and 2.1 kg reduction in body weight in the DPP trial.53 Focusing diabetes prevention efforts in lower NSES areas may help in ameliorating health inequalities. Our study provides a framework to identify areas that may require more intensive efforts by linking diabetes outcomes with readily measurable NSES.

Conclusion

To conclude, our study is the first to show a social gradient in diabetes burden by contextual measures of socioeconomic status in southern Europe. The use of universal EHR of an entire population improves representability and statistical power, providing a rich representation of population health patterns. Future studies should provide targets for intervention to address this population health inequity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

UB was supported by a Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future – Lerner Fellowship and a Postgraduate Fellowship from the Obra Social La Caixa.

Footnotes

Contributors: UB and MF conceptualized the study. UB conducted the statistical analysis and drafted the first version of the manuscript. UB, MF and FHB interpreted results and revised the first version of the manuscript. LSP and IdC organized and conducted health data collection. MF obtained funding for the study. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: MF was supported by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007– 2013/ERC Starting Grant HeartHealthyHoods Agreement n. 336893). FHB was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Diabetes Research Center (P30DK079637).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Madrid Primary Care Research Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Neighborhood SES indicators are available online as detailed in the appendix. Health data was obtained from the primary care system and cannot be shared due to privacy concerns.

References

- 1. NCD-RisC. Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4·4 million participants. The Lancet 2016;387:1513–30. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00618-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang P, Zhang X, Brown J, et al. Global healthcare expenditure on diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;87:293–301. 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol 1985;14:32–8. 10.1093/ije/14.1.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Corriere MD, Yao W, Xue QL, et al. The association of neighborhood characteristics with obesity and metabolic conditions in older women. J Nutr Health Aging 2014;18:792–8. 10.1007/s12603-014-0551-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Garcia L, Lee A, Zeki Al Hazzouri A, et al. The impact of neighborhood socioeconomic position on prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes in older latinos: the sacramento area latino study on aging. Hisp Health Care Int 2015;13:77–85. 10.1891/1540-4153.13.2.77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gaskin DJ, Thorpe RJ, McGinty EE, et al. Disparities in diabetes: the nexus of race, poverty, and place. Am J Public Health 2014;104:2147–55. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johnson RC, Schoeni RF. Early-life origins of adult disease: national longitudinal population-based study of the United States. Am J Public Health 2011;101:2317–24. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krishnan S, Cozier YC, Rosenberg L, et al. Socioeconomic status and incidence of type 2 diabetes: results from the Black Women’s Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 2010;171:564–70. 10.1093/aje/kwp443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Piccolo RS, Duncan DT, Pearce N, et al. The role of neighborhood characteristics in racial/ethnic disparities in type 2 diabetes: results from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) survey. Soc Sci Med 2015;130:79–90. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.01.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Geraghty EM, Balsbaugh T, Nuovo J, et al. Using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to assess outcome disparities in patients with type 2 diabetes and hyperlipidemia. J Am Board Fam Med 2010;23:88–96. 10.3122/jabfm.2010.01.090149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Connolly V, Unwin N, Sherriff P, et al. Diabetes prevalence and socioeconomic status: a population based study showing increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in deprived areas. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000;54:173–7. 10.1136/jech.54.3.173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hippisley-Cox J, O’Hanlon S, Coupland C. Association of deprivation, ethnicity, and sex with quality indicators for diabetes: population based survey of 53,000 patients in primary care. BMJ 2004;329:1267–9. 10.1136/bmj.329.7477.1267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Booth GL, Creatore MI, Moineddin R, et al. Unwalkable neighborhoods, poverty, and the risk of diabetes among recent immigrants to Canada compared with long-term residents. Diabetes Care 2013;36:302–8. 10.2337/dc12-0777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Borkhoff CM, Saskin R, Rabeneck L, et al. Disparities in receipt of screening tests for cancer, diabetes and high cholesterol in Ontario, Canada: a population-based study using area-based methods. Can J Public Health 2013;104:284–90. doi:10.17269/cjph.104.3699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cox M, Boyle PJ, Davey PG, et al. Locality deprivation and Type 2 diabetes incidence: a local test of relative inequalities. Soc Sci Med 2007;65:1953–64. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bebb C, Kendrick D, Stewart J, et al. Inequalities in glycaemic control in patients with Type 2 diabetes in primary care. Diabet Med 2005;22:1364–71. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01662.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guthrie B, Emslie-Smith A, Morris AD. Which people with Type 2 diabetes achieve good control of intermediate outcomes? Population database study in a UK region. Diabet Med 2009;26:1269–76. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02837.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. James GD, Baker P, Badrick E, et al. Ethnic and social disparity in glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes; cohort study in general practice 2004-9. J R Soc Med 2012;105:300–8. 10.1258/jrsm.2012.110289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Millett C, Car J, Eldred D, et al. Diabetes prevalence, process of care and outcomes in relation to practice size, caseload and deprivation: national cross-sectional study in primary care. J R Soc Med 2007;100:275–83. 10.1177/014107680710000613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mezuk B, Chaikiat Å, Li X, et al. Depression, neighborhood deprivation and risk of type 2 diabetes. Health Place 2013;23:63–9. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. White JS, Hamad R, Li X, et al. Long-term effects of neighbourhood deprivation on diabetes risk: quasi-experimental evidence from a refugee dispersal policy in Sweden. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2016;4:517–24. 10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30009-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chaix B, Billaudeau N, Thomas F, et al. Neighborhood effects on health: correcting bias from neighborhood effects on participation. Epidemiology 2011;22:18–26. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181fd2961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cubbin C, Sundquist K, Ahlén H, et al. Neighborhood deprivation and cardiovascular disease risk factors: protective and harmful effects. Scand J Public Health 2006;34:228–37. 10.1080/14034940500327935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Müller G, Kluttig A, Greiser KH, et al. Regional and neighborhood disparities in the odds of type 2 diabetes: results from 5 population-based studies in Germany (DIAB-CORE consortium). Am J Epidemiol 2013;178:221–30. 10.1093/aje/kws466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Müller G, Wellmann J, Hartwig S, et al. Association of neighbourhood unemployment rate with incident Type 2 diabetes mellitus in five German regions. Diabet Med 2015;32:1017–22. 10.1111/dme.12652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sundquist K, Eriksson U, Mezuk B, et al. Neighborhood walkability, deprivation and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a population-based study on 512,061 Swedish adults. Health Place 2015;31:24–30. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ludwig J, Sanbonmatsu L, Gennetian L, et al. Neighborhoods, obesity, and diabetes–a randomized social experiment. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1509–19. 10.1056/NEJMsa1103216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Larrañaga I, Arteagoitia JM, Rodriguez JL, et al. Socio-economic inequalities in the prevalence of Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular risk factors and chronic diabetic complications in the Basque Country, Spain. Diabet Med 2005;22:1047–53. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01598.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Reques L, Giráldez-García C, Miqueleiz E, et al. Educational differences in mortality and the relative importance of different causes of death: a 7-year follow-up study of Spanish adults. J Epidemiol Community Health 2014;68:1151–60. 10.1136/jech-2014-204186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tammaru T, van Ham M, Marcińczak S, et al. Socio-Economic segregation in European Capital Cities: East Meets West: Taylor & Francis, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Weisskopf MG, Sparrow D, Hu H, et al. Biased exposure-health effect estimates from selection in cohort studies: are environmental studies at particular risk? Environ Health Perspect 2015;123:1113–22. 10.1289/ehp.1408888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bilal U, Díez J, Alfayate S, et al. Population cardiovascular health and urban environments: the Heart Healthy Hoods exploratory study in Madrid, Spain. BMC Med Res Methodol 2016;16:104 10.1186/s12874-016-0213-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Borrell C, Malmusi D, Muntaner C. Introduction to the Evaluating the impact of structural policies on health inequalities and their social determinants and fostering change (SOPHIE) project. Int J Health Serv 2017;47:10–17. 10.1177/0020731416681891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. de Burgos-Lunar C, Salinero-Fort MA, Cárdenas-Valladolid J, et al. Validation of diabetes mellitus and hypertension diagnosis in computerized medical records in primary health care. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:146 10.1186/1471-2288-11-146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika 1994;81:515–26. 10.1093/biomet/81.3.515 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Harrell F. Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic and ordinal regression, and survival analysis: Springer, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wilf-Miron R, Peled R, Yaari E, et al. Disparities in diabetes care: role of the patient’s socio-demographic characteristics. BMC Public Health 2010;10:729 10.1186/1471-2458-10-729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Glass TA, Bilal U. Are neighborhoods causal? Complications arising from the ’stickiness' of ZNA. Soc Sci Med 2016;166:244–53. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Auchincloss AH, Diez Roux AV, Mujahid MS, et al. Neighborhood resources for physical activity and healthy foods and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: the Multi-Ethnic study of Atherosclerosis. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1698–704. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Christine PJ, Auchincloss AH, Bertoni AG, et al. Longitudinal associations between neighborhood physical and social environments and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1311–20. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Díez J, Bilal U, Cebrecos A, et al. Understanding differences in the local food environment across countries: A case study in Madrid (Spain) and Baltimore (USA). Prev Med 2016;89:237–44. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bilal U, Jones-Smith J, Diez J, et al. Neighborhood social and economic change and retail food environment change in Madrid (Spain): the heart healthy hoods study. Health Place 2018;51:107–17. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Díez J, Conde P, Sandin M, et al. Understanding the local food environment: a participatory photovoice project in a low-income area in Madrid, Spain. Health Place 2017;43:95–103. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Díez J, Valiente R, Ramos C, et al. The mismatch between observational measures and residents' perspectives on the retail food environment: a mixed-methods approach in the Heart Healthy Hoods study. Public Health Nutr 2017:2970–9. 10.1017/S1368980017001604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gullón P, Bilal U, Cebrecos A, et al. Intersection of neighborhood dynamics and socioeconomic status in small-area walkability: the Heart Healthy Hoods project. Int J Health Geogr 2017;16:21 10.1186/s12942-017-0095-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. The Lancet 2005;365:1099–104. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74234-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Merino Merino B, Vega Morales J, Gil Luciano A, et al. Integration of social determinants of health and equity into health strategies, programmes and activities: health equity training process in Spain. 2013.

- 48. Franco M, Bilal U, Diez-Roux AV. Preventing non-communicable diseases through structural changes in urban environments. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69:509–11. 10.1136/jech-2014-203865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, et al. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet 2009;374:1677–86. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61457-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ackermann RT, Finch EA, Brizendine E, et al. Translating the diabetes prevention program into the community. The DEPLOY Pilot Study. Am J Prev Med 2008;35:357–63. 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fitzpatrick SL, Golden SH, Stewart K, et al. Effect of DECIDE (Decision-making Education for Choices In Diabetes Everyday) Program Delivery Modalities on Clinical and Behavioral Outcomes in Urban African Americans With Type 2 Diabetes: a randomized trial. Diabetes Care 2016;39:2149–57. 10.2337/dc16-0941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hill-Briggs F, Lazo M, Peyrot M, et al. Effect of problem-solving-based diabetes self-management training on diabetes control in a low income patient sample. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:972–8. 10.1007/s11606-011-1689-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hamman RF, Wing RR, Edelstein SL, et al. Effect of weight loss with lifestyle intervention on risk of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006;29:2102–7. 10.2337/dc06-0560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-021143supp001.pdf (427.2KB, pdf)