Abstract

Nucleosomes cover most of the genome and are thought to be displaced by transcription factors (TFs) in regions that direct gene expression. However, the modes of interaction between TFs and nucleosomal DNA remain largely unknown. Here, we have systematically explored interactions between the nucleosome and 220 TFs representing diverse structural families. Consistently with earlier observations, we find that the majority of the studied TFs have less access to nucleosomal DNA than to free DNA. The motifs recovered from TFs bound to nucleosomal and free DNA are generally similar; however, steric hindrance and scaffolding by the nucleosome result in specific positioning and orientation of the motifs. Many TFs preferentially bind close to the end of nucleosomal DNA, or to periodic positions at its solvent-exposed side. TFs often also bind to nucleosomal DNA in a particular orientation. Some TFs specifically interact with DNA located at the dyad position where only one DNA gyre is wound, whereas other TFs prefer sites spanning two DNA gyres and bind specifically to each of them. Our work reveals striking differences in TF binding to free and nucleosomal DNA, and uncovers a rich interaction landscape between TFs and the nucleosome.

The packaging of eukaryotic genomes is accomplished by histones, proteins that form an octameric complex that binds to the DNA backbone, forming nucleosomes1–4. In a canonical nucleosome, a 147 bp segment of DNA is wrapped around the histone octamer in a left-handed, superhelical arrangement for a total of 1.65 turns, with the DNA helix entering and exiting the nucleosome from the same side of the histone octamer. The two DNA gyres are parallel to each other except at the position located between the entering and the exiting DNA, where a dyad region of ~15 bp contains only a single DNA gyre.

The nucleosome presents a barrier for the binding of other proteins such as RNA polymerases to DNA5–8. Similarly, most TFs are thought to be unable to bind to nucleosomal DNA9,10, except for a specific class of TFs called the pioneer factors11. Despite the importance of the nucleosome in both chromatin organization and transcriptional control12–17, the effect of nucleosomes on TF binding has not been systematically characterized.

Results

Nucleosome CAP-SELEX

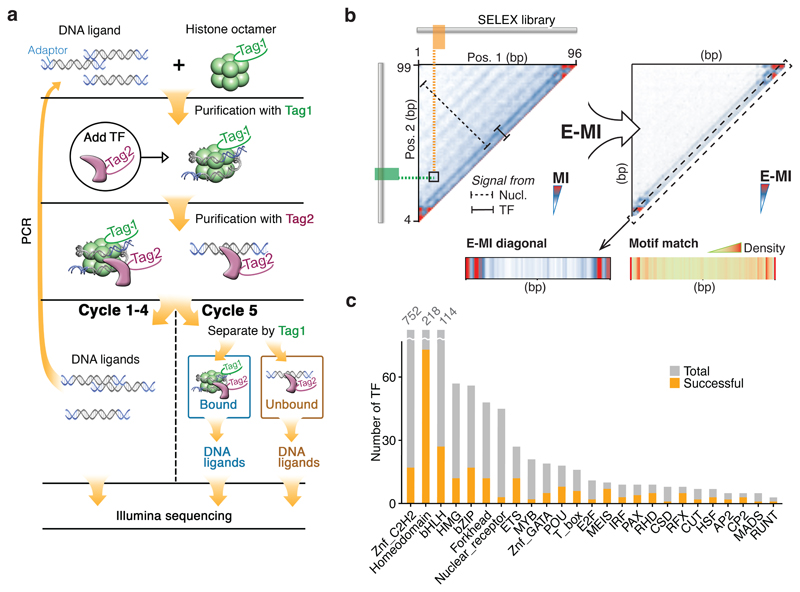

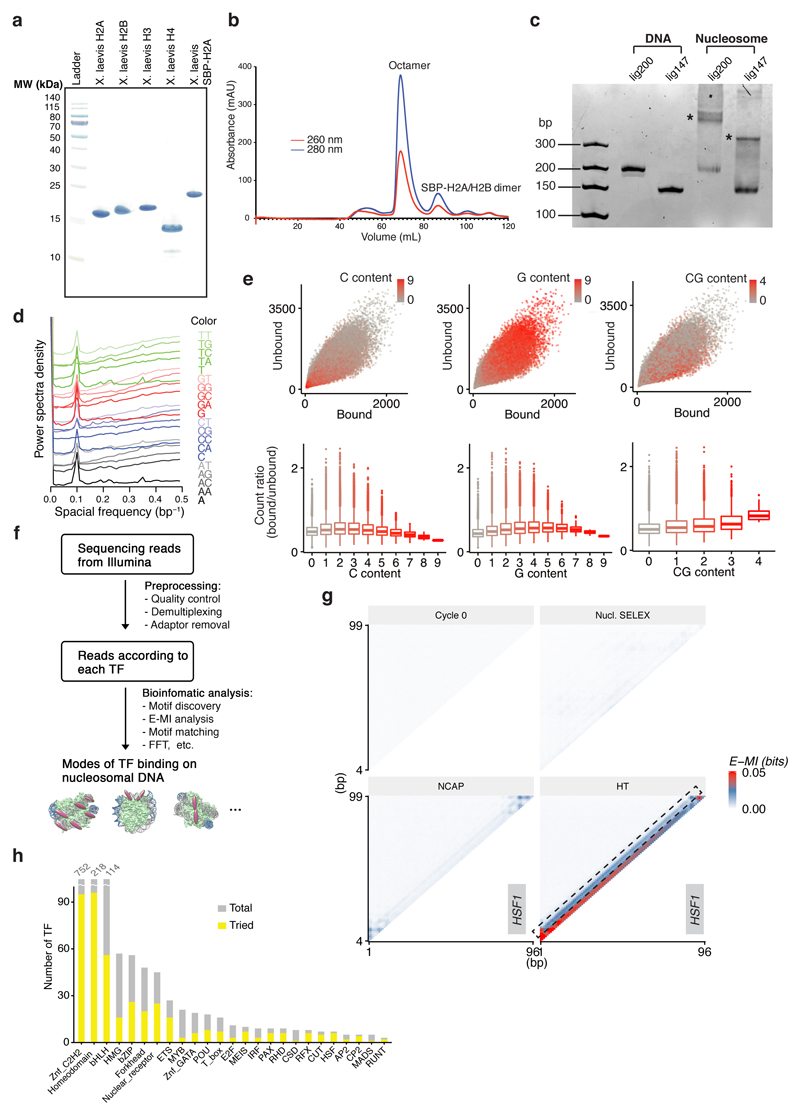

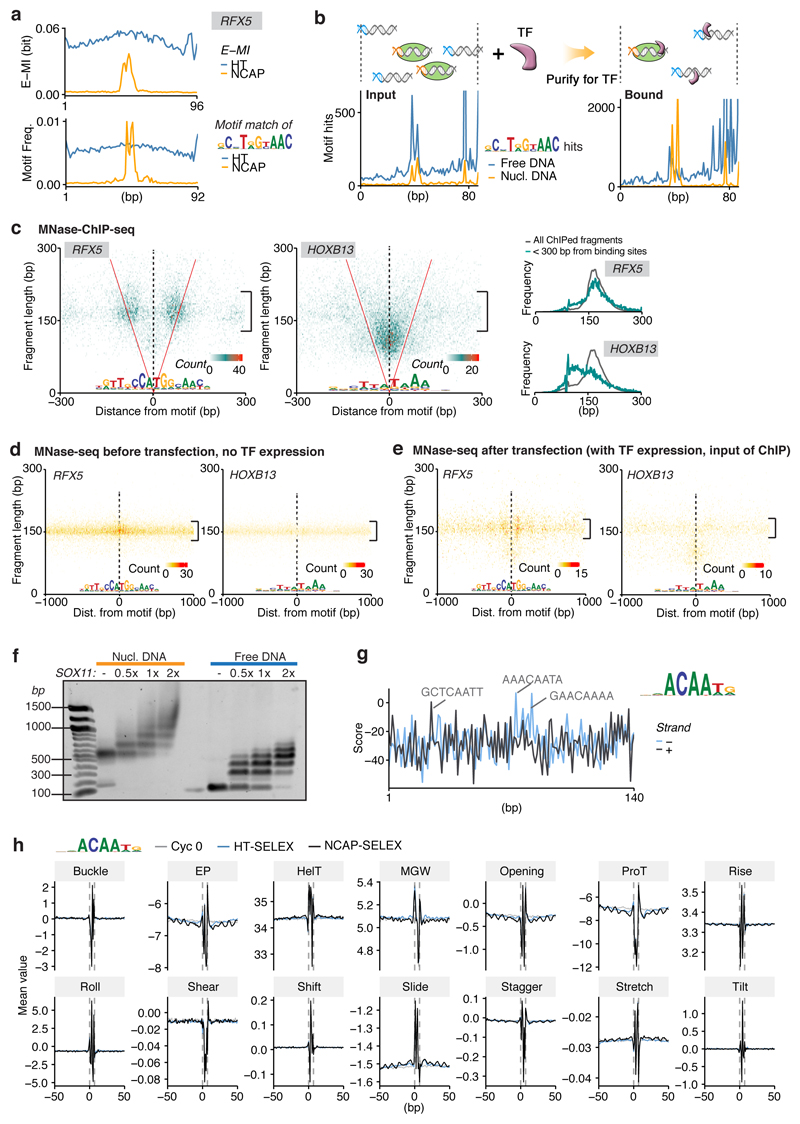

To determine the effect of nucleosomes on TF-DNA binding, we developed Nucleosome Consecutive Affinity-Purification SELEX (NCAP-SELEX; Fig. 1a; Extended Data Fig. 1). The method is based on analysis of enrichment of specific sequences from complex 147 bp (lig147) or 200 bp (lig200) DNA libraries, containing either 101 or 154 bp randomized regions, respectively. The sequences are reconstituted into a nucleosome, and the complexes incubated with TFs, which are subsequently purified and the bound DNA recovered by PCR. After multiple selection rounds, dissociated nucleosomal DNA is separated from intact nucleosomes. Analysis of the NCAP-SELEX enriched sequences allows inference of TF binding specificities and positions on nucleosomal DNA, together with their effect on the stability of the nucleosome.

Figure 1. Nucleosome CAP-SELEX.

a, Schematic representation of NCAP-SELEX. The DNA ligands for SELEX contain a randomized region (grey) with fixed adaptors (blue). The protocol first selects ligands that are favored by the nucleosome, and then from the nucleosome-bound ligand pool selects ligands that bind to a given TF. The orthogonal tagging of histone H2A (tag1) and TFs (tag2) enables the consecutive affinity purification. In the last (5th) cycle, the TF-bound DNA ligands are further separated into nucleosome-bound and unbound libraries before sequencing. b, TF-signal analysis by E-MI. Both the TF (solid bar) and the nucleosome (dotted bar) binding signals can be captured by the mutual information (MI) between 3-mer distributions at two non-overlapping positions of the ligand (left). In our analysis, we further focus on MI of the most enriched 3-mer pairs (E-MI, right) to filter out the nucleosome signals. Most analyses in this manuscript use the E-MI diagonal (box, containing E-MI from directly adjacent non-overlapping 3-mer pairs) because it is most informative of TF binding and generally similar to motif-matching result (bottom). c, Family-wise coverage of successful TFs.

We performed SELEX both using nucleosomal (NCAP-SELEX) and free DNA (HT-SELEX18,19) using 413 human TF extended DNA binding domains (eDBDs) and 46 full-length (FL) constructs (Extended Data Fig. 1h; Supplementary Table 1). The selected TFs covered 29% of the high-confidence TFs from Vaquerizas et al.20. The enriched sequences were analyzed computationally using motif matching, de novo motif discovery, and mutual information (MI) pipelines (see Methods). Because nucleosomes can affect TF motifs21, we primarily used a MI measure, which can capture any type of enriched sequence pattern (see Fig. 1b). Standard MI analysis also captures nucleosome sequence preference. To separate TF signals from the nucleosome signal, we limited the MI measure to the most highly enriched subsequences (enriched sequence based MI; E-MI; Fig. 1b). In parallel, we also analyzed all data using motif-based approaches to explain and validate the findings based on E-MI (Supplementary Data 1, 2). Among the tested TFs, 220 eDBDs and 13 FLs were successful (Fig. 1c; see Methods for details).

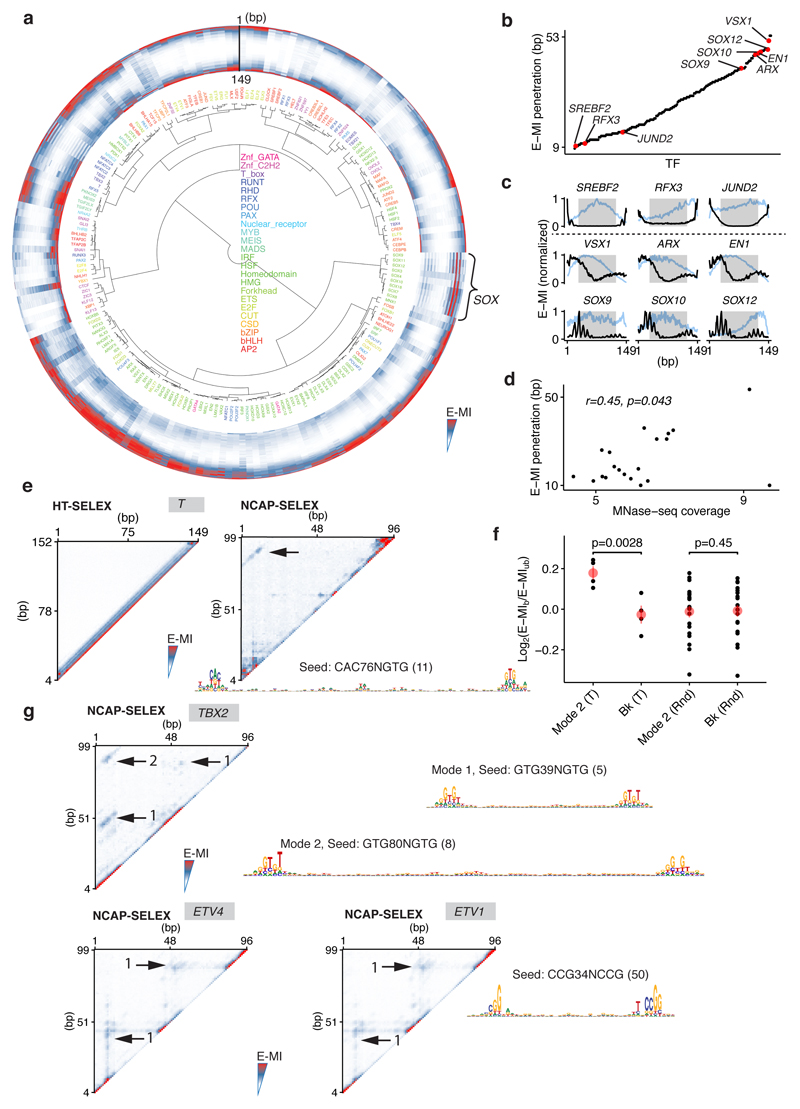

Nucleosome inhibits TF binding

To determine the general effect of nucleosomes on TF-DNA binding, we analyzed E-MI signals on lig200, which can accommodate only one nucleosome and contains both nucleosomal and free DNA (Fig. 2a; Extended Data Fig. 2, 3). On lig200 almost all TFs had a lower E-MI signal at the center (Extended Data Fig. 2a), where the nucleosome occupancy is highest, indicating that DNA-binding of most TFs is inhibited or spatially restricted by the presence of a nucleosome. However, the effect of the nucleosome on TF binding varied strongly between the TFs (Extended Data Fig. 2b, c). For example, SREBF2, RFX3, and JUND2 only show E-MI signal at the extreme ends of the ligand, suggesting that in the presence of free DNA, they are largely excluded from nucleosomal DNA. In contrast, other TFs such as VSX1, ARX, EN1, and SOXs are more capable of binding nucleosomal DNA. The biochemical ability of TFs to bind to nucleosomal DNA affected their binding also in vivo in K562 cells (Extended Data Fig. 2d). These results indicate that the nucleosome often inhibits TF-DNA binding, but that the extent of the effect varies greatly between TFs.

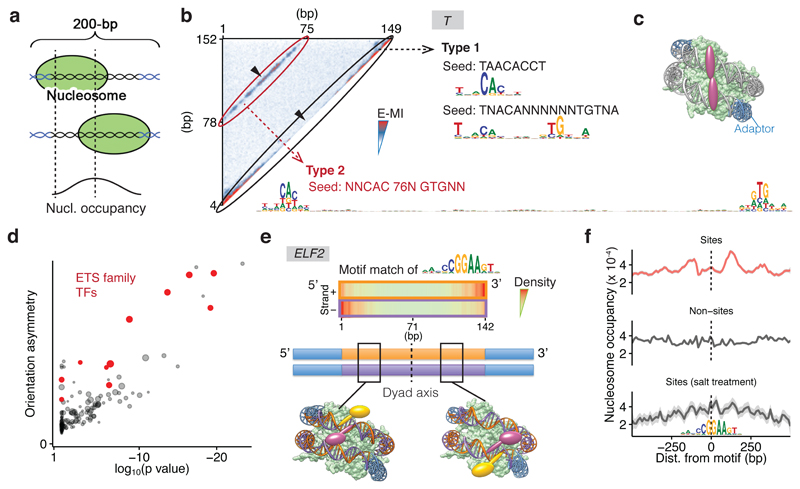

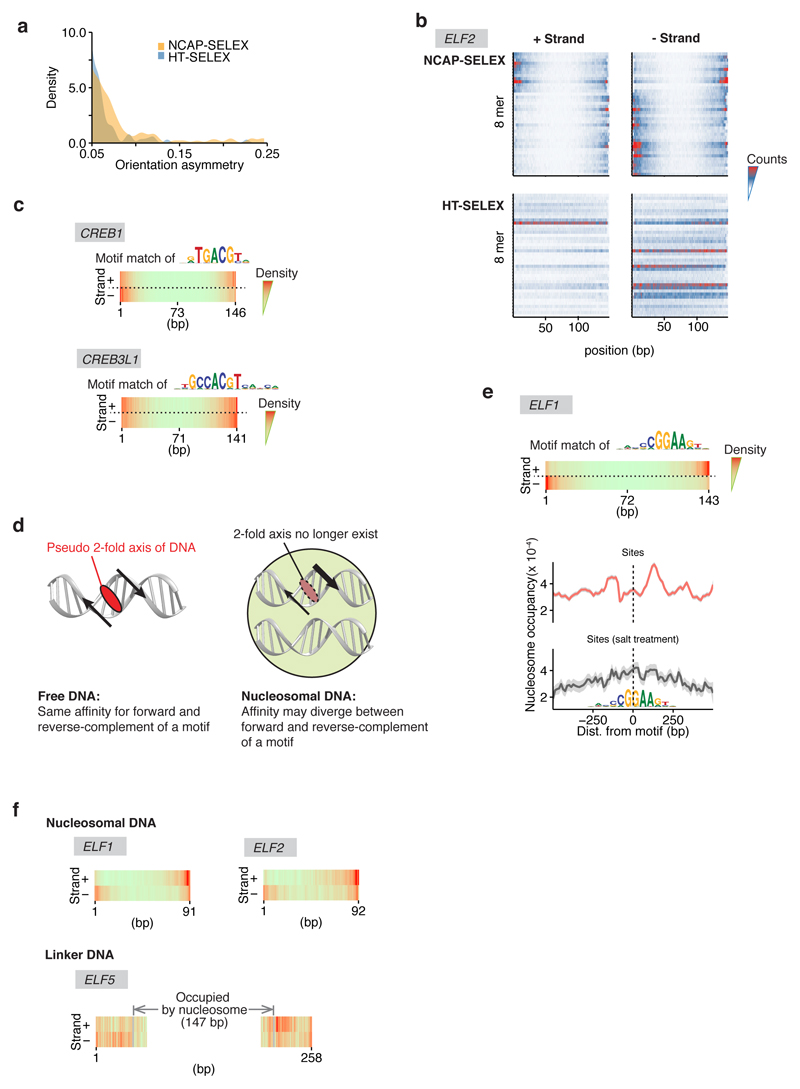

Figure 2. Nucleosome scaffolds DNA and breaks its rotational symmetry, enabling new TF binding modes.

a, Schematic representation of single nucleosomes assembled on different positions of lig200 (top, middle), resulting in higher nucleosome occupancy towards the center (bottom). b, Two different binding types of T (brachyury) on nucleosomal DNA. Heatmap shows E-MI for all combinations of positions on lig200. Type 1 signal near the diagonal yields short motifs similar to those on free DNA. The Type 2 signal corresponds to a ~80-bp-long motif. Note that in contrast to Type 1 signal, Type 2 signal is not inhibited by the high nucleosome occupancy at the center (arrowheads). c, Schematic representation of TFs that bind both gyres of nucleosomal DNA. d, Orientational asymmetry of binding of individual TFs on nucleosomal DNA. y-axis: binding energy difference between two relative orientations of the most enriched subsequences. x-axis: t-test p-value of the difference compared to binding on free DNA (see Methods). Note that most ETS-family TFs (red) show prominent asymmetry. Dot size represents the extent of signal enrichment in each TF’s NCAP-SELEX library. e, Orientational asymmetry of the ETS factor ELF2. At the 5’ end of the ligand, ELF2 motif (top) is enriched on the minus strand, because ELF2 prefers to bind DNA in one orientation relative to the nucleosome (yellow, left bottom cartoon). At the 3’ end of the ligand, ELF2 motif is enriched on the plus strand, as this leads to the same orientation of the ELF2 protein with respect to the nucleosome (yellow, right bottom). Note also that the two yellow ELF2 proteins make symmetric contacts, but to different strands of DNA (marked orange and purple; adapters are indicated in blue). Note that TF positions on the ligand are not fixed, for simplicity only few example positions are shown. f, Asymmetric nucleosome distribution around genomic ELF2 sites (top, sites positioned at center). Asymmetry is not observed for the same ELF2 sites after salt treatment to mobilize the nucleosome (bottom) or for ELF2 motifs without ChIP signal (middle). Nucleosome positions are shown as frequency of the center of MNase-fragments (140–170 bp). Each profile (n=999 data points) is LOESS smoothed with a span of 0.05 and plotted with the SE band.

TFs can bind both nucleosomal DNA gyres

Some chromatin modifying enzymes22 and synthetic molecules23 can bind both DNA gyres wrapped around the nucleosome. To explore whether TFs can also exhibit such a binding mode, we analyzed the entire 2D E-MI signals. We found that binding of the T-box family TF brachyury (T) to nucleosomal DNA resulted in two prominent E-MI signals (Fig. 2b). One was located at the E-MI diagonal, i.e. observed between adjacent subsequences, whereas the other resulted from sequences located ~ 80 bp from each other. The first signal represents binding of T to nucleosomal DNA similarly to free DNA. The second is associated with an ~ 80 bp motif, indicating dimeric binding spanning both DNA gyres (Fig. 2c). This type of binding was also observed for lig147 but not detected on free DNA (Extended Data Fig. 2e). The signal for the long motif is stronger on the ligands that remained bound to the nucleosome (Extended Data Fig. 2f), indicating that the gyre-spanning mode of T stabilizes nucleosomes. Similar binding was also observed for another T-box factor, TBX2 (Extended Data Fig. 2g), but not for other TFs. Despite the clear biochemical ability of T and TBX2 to bind to nucleosomal DNA using the cross-gyre motif, we did not identify this motif from available ChIP-seq data24,25. Thus, the biological role, if any, of this binding mode needs to be addressed by further experimentation. For some TFs, we also identified weak signals for another binding mode, where the TFs contact nucleosomal DNA at positions spaced by ~ 40 bp (e.g. TBX2 and ETV; Extended Data Fig. 2g). These results indicate that the nucleosome scaffold enables new binding modes for TFs that are not possible on free DNA.

Nucleosome affects TF binding orientation

In analysis of motif matches on lig200, we noted that some TFs’ motifs displayed a bias of matches in one orientation at the 5’ end, and in the other orientation at the 3’ end of the ligand. This pattern was observed for many ETS and CREB bZIP factors (Fig. 2d, e; Extended Data Fig. 4). The orientational preference induced by the nucleosome can be explained by the fact that nucleosome breaks the rotational symmetry of DNA (Extended Data Fig. 4d); depending on TF orientation, a particular side of a TF will be in proximity with either the second gyre of nucleosomal DNA, or the histone proteins.

To determine whether the directional binding of TFs to a nucleosome is also observed in vivo, we mapped nucleosome positions genome-wide in the human colorectal cancer cell line LoVo using micrococcal nuclease digestion followed by sequencing (MNase-seq). We found that the nucleosome distribution is asymmetric (p < 0.0003, two-side t-test) around ELF1 and ELF2 in vivo sites (Fig. 2f; Extended Data Fig. 4e). Such asymmetry is not observed for the same ELF2 sites after salt treatment that laterally mobilizes the nucleosomes, or around ELF2 motif matches that do not show ChIP-seq signal (Fig. 2f). The nucleosome occupancy is lower upstream than downstream of the ELF2 sites. This pattern likely suggests that the more stable binding of ELF2 downstream of the nucleosome displaces the nucleosome or pushes it upstream. Several chromatin features that are asymmetric relative to TF occupied sites have been reported26–28. Our observation that nucleosome itself induces asymmetry in preferred TF binding orientation provides a potential mechanistic basis for these findings.

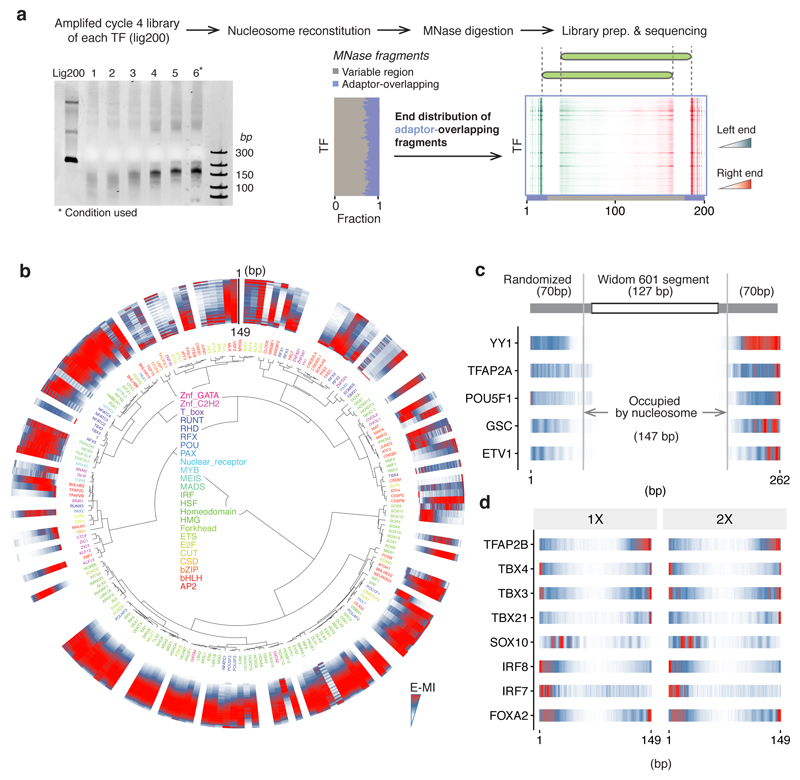

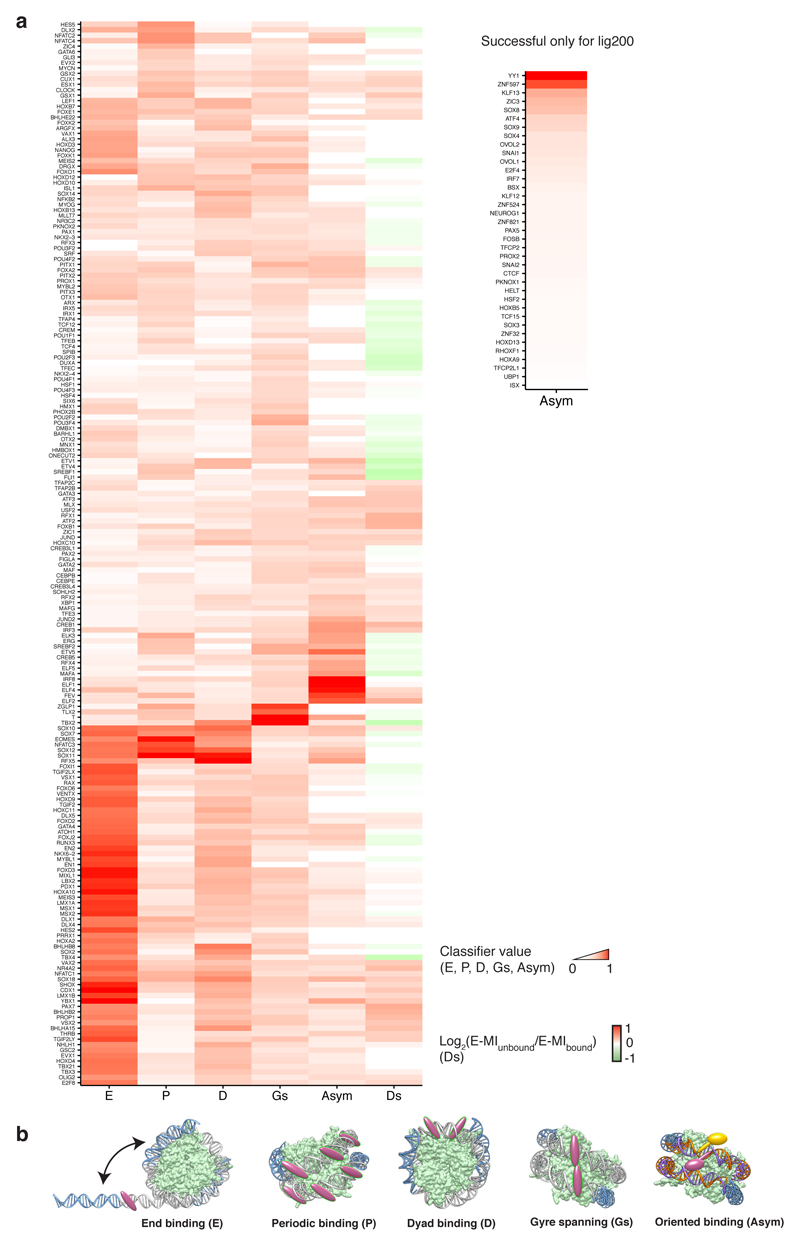

Nucleosome induces positional TF binding preferences

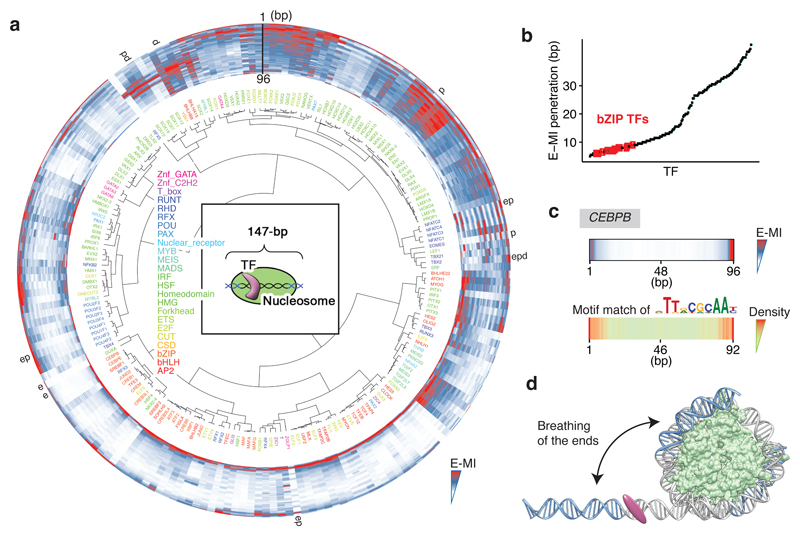

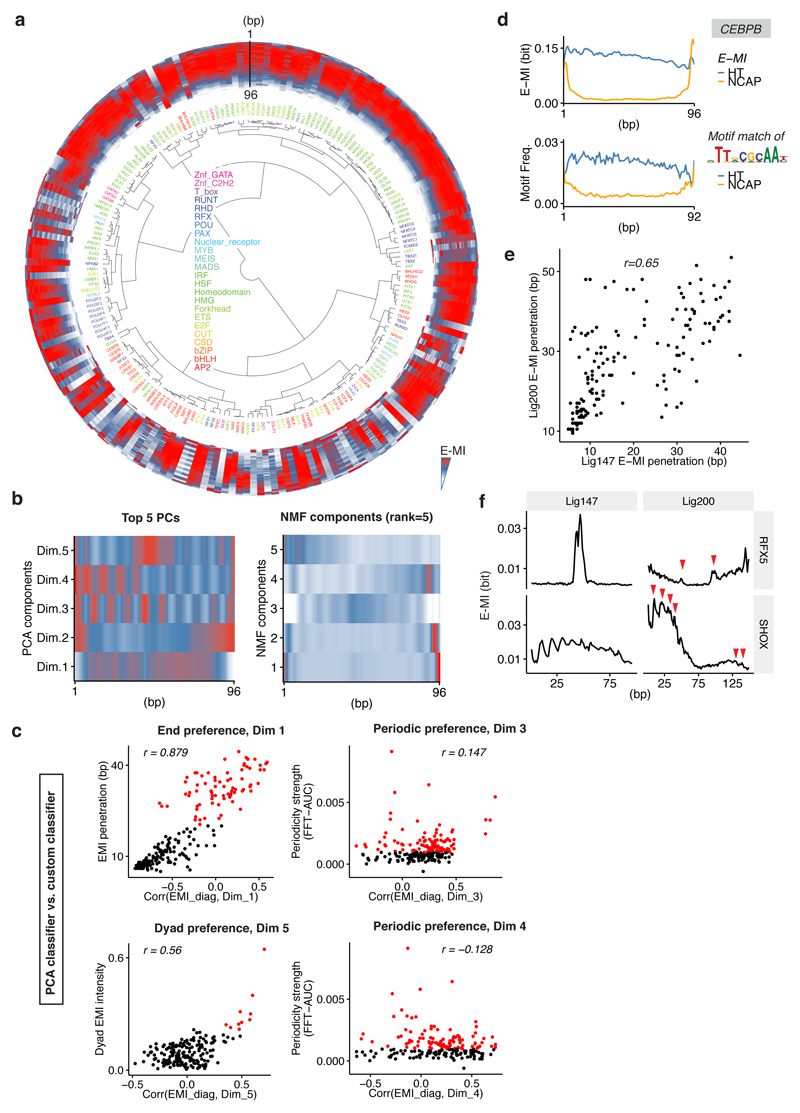

Next we analyzed the positional preference of TF binding on nucleosomal DNA. We designed the 147 bp NCAP-SELEX ligand (lig147) that matches the preferred length of nucleosomal DNA29, allowing more precise mapping of TF binding positions relative to the nucleosome. The results indicate that the presence of nucleosome restricts TF binding, and induces several types of positional preference (Fig. 3; Extended Data Fig. 5, 6). Expert analyses and machine learning analyses (see Methods and Extended Data Fig. 6b, c) revealed three types of positional preference on nucleosomal DNA (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Table 5): (1) End preference; these TFs prefer positions towards the end of the ligand that are partially accessible due to a process called “breathing”1,30,31. Many TFs of this class either radially cover more than 180° of the DNA circumference (e.g. bZIP and bHLH), or bind to long motifs through a continuous interaction with DNA (e.g., C2H2 Zinc fingers) (Fig. 3a). (2) Periodic preference; these TFs tend to bind to periodic positions on nucleosomal DNA, and (3) Dyad preference; these TFs prefer to bind to nucleosomal DNA near the dyad position.

Figure 3. Nucleosome induces positional preference to TF binding.

a, Hierarchical clustering of the E-MI diagonals for NCAP-SELEX with the 147-bp ligand (lig147). E-MI diagonal is scaled for each TF (see Methods). The names of the TFs are colored by family. TFs from the same family tend to be clustered together. A few TFs were annotated as examples to illustrate their end (e), periodic (p), and dyad (d) preferences (see Supplementary Table 5). Note the preferences are not mutually exclusive. Center: schematic illustration of the fixed position of nucleosome on lig147. b, E-MI penetration of each TF on lig147. All bZIP TFs are marked with red. c, E-MI diagonal and motif matching results for the bZIP factor CEBPB. d, Schematic representation showing a TF that prefers the ends of nucleosomal DNA due to breathing. Both ends of nucleosomal DNA will breathe but only one is illustrated here for clarity.

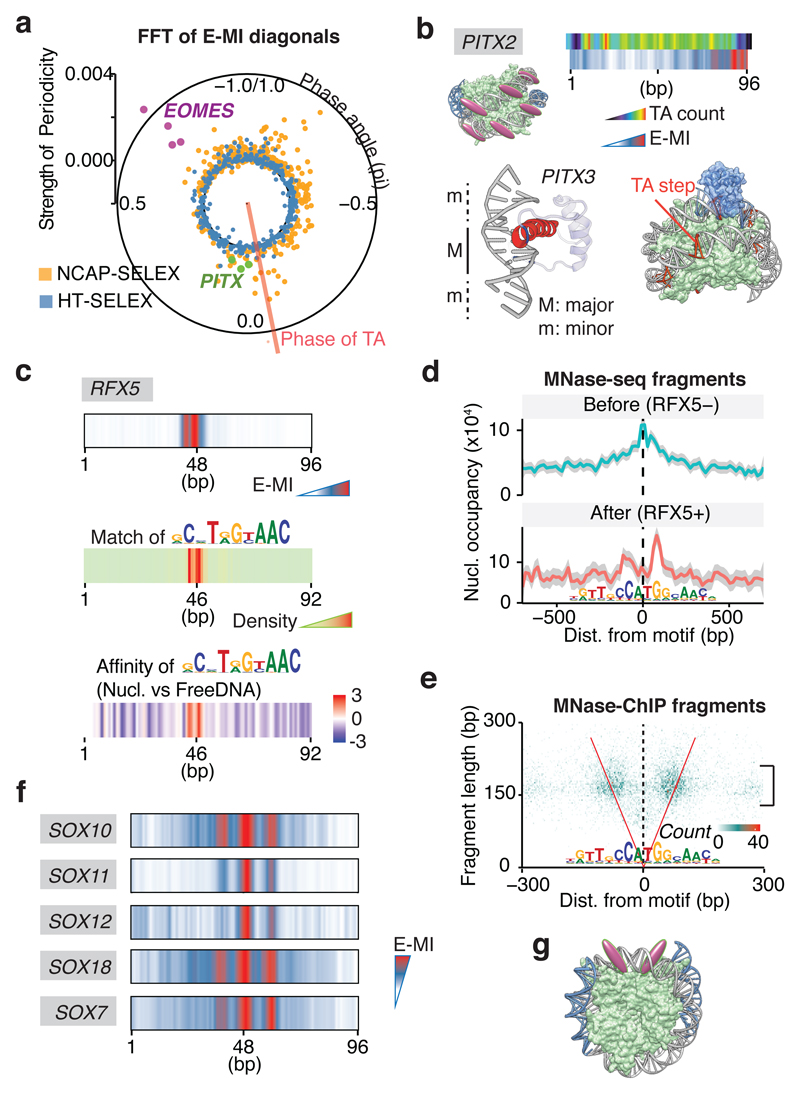

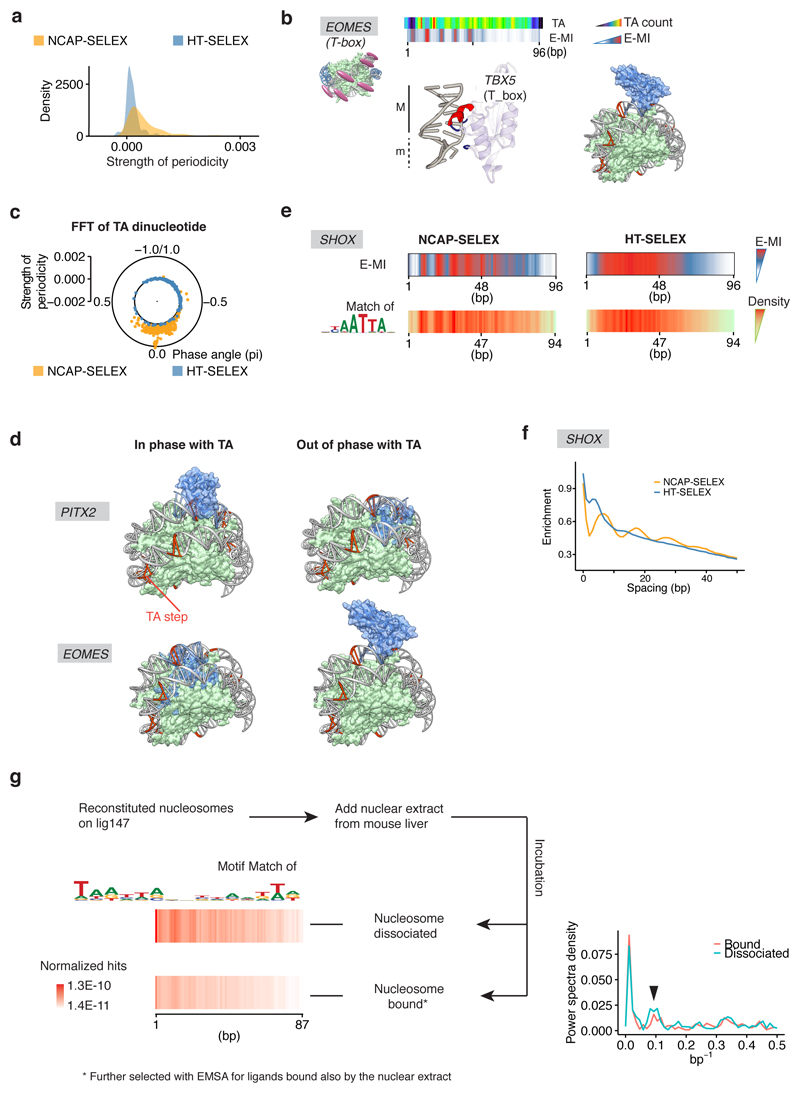

Half of the circumference of nucleosomal DNA is in close proximity to the histones. As DNA is helical, equivalent positions that could be accessible to TFs are located at ~10 bp intervals. Accordingly, we found that many TFs prefer to bind to positions located ~10 bp apart on nucleosomal DNA (Fig. 3a; Extended Data Fig. 7). By applying a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to the E-MI diagonals, we obtained both the strength and rotational position (phase) of the ~10 bp periodicity for each TF (Fig. 4a). Analysis of the rotational position of binding for the TFs revealed that both major and minor grooves of nucleosomal DNA were accessible from the solvent side. For example, PITX and EOMES prefer almost opposite phases (Fig. 4a). This is consistent with the known structures; PITX contacts DNA principally via the major groove32 (structure in Fig. 4b), whereas T-box TFs such as EOMES contact DNA mainly via the minor groove33,34 (Extended Data Fig. 7b). Such periodic preference of binding has been reported previously for p53 and the glucocorticoid receptor35,36, but the prevalence of this phenomenon was unclear. Among the TF families, periodic binding was particularly common among homeodomain TFs (Fig. 3a), and was also detected for homeodomain TFs from mouse liver (Extended Data Fig. 7g). Taken together, the results suggest that consistently with structural data37 (Extended Data Fig. 5a), many TFs can bind nucleosomal DNA from the solvent-accessible side.

Figure 4. Periodic and position-specific binding of TFs to nucleosomal DNA.

a, TF binding on nucleosomal DNA commonly displays ~10 bp periodic pattern. The polar plot shows strength and phase derived from FFT of E-MI diagonals, for both NCAP-SELEX (orange) and HT-SELEX (blue; free DNA). Note that EOMES (magenta, four replicates) and PITX (green for PITX1, 2, 3) have opposite phases. Phase of TA dinucleotide (red line) indicates where histones contact nucleosomal DNA40. b, PITX prefers exposed major grooves on nucleosomal DNA. The E-MI diagonal of PITX is in phase with the TA peaks along the ligand. Accordingly, the structure of PITX (PDB entry 2LKX) shows contacts with DNA principally in the major groove (M). The base-contacting helices (red) and loops (blue) are indicated. Cartoon representation to the right shows that the steric hindrance is minimal when PITX (blue) binds in phase with TA (orange) on the nucleosome structure (PDB entry 3UT9). c, RFX5 prefers to bind near the nucleosome dyad. E-MI diagonal (top), motif matching (middle), and competition assay (bottom) are shown. Positive values in the competition assay indicate preference towards nucleosomal-DNA. d, Binding of RFX5 affects local nucleosome profile in vivo. Nucleosome distribution is examined by MNase-seq before (top) and after (bottom) exogenous expression of RFX5 in HEK293 cells. RFX5 motif matches within MNase-ChIP peaks are centered. Nucleosome occupancy is shown as frequency of the center of MNase-fragments (140–170 bp). Each profile (n=1401 data points) is LOESS smoothed with a span of 0.05 and plotted with the SE band. Before RFX5 expression, the nucleosome occupancy is higher at the RFX5 sites than the surrounding region (top); the nucleosomes are shifted after the expression of RFX5 (bottom). e, MNase-ChIP indicates that RFX5 binds to nucleosomal DNA in vivo. Counts of MNase-ChIP fragments are binned to 3 bp by 3 bp bins according to their lengths and center positions. Note that most ChIPed fragments are ~150 bp in size (bracket) and overlap the RFX5 motif (are between the red “V” lines), indicating that RFX5 prefers to bind to nucleosomal DNA. f, E-MI diagonal of SOX family TFs showing preferred binding around the dyad. g, Schematic representation of TFs that prefer to bind around the dyad.

Analysis of the positional preference of TFs on nucleosomal DNA also revealed that the dyad region is strongly preferred by some TFs (Fig. 4c –g; Extended Data Fig. 8; see also refs.38,39). For example, RFX5 shows very strong binding to the dyad positions of lig147 (Fig. 4c); based on a competition assay, RFX5’s affinity to dyad positions is higher than to free DNA (Fig 4c, bottom; Extended Data Fig. 8b). To test whether RFX5 also prefers nucleosomal DNA in vivo, we expressed RFX5 in HEK-293 cells, followed by detection of nucleosome positions and RFX5 occupied sites using MNase-seq and MNase-ChIP. HEK-293 cells do not endogenously express RFX5, and in untransfected cells the positions where exogenous RFX5 binds are located at a maximum of nucleosome occupancy (Fig. 4d; Extended Data Fig. 8). However, upon RFX5 expression, RFX5 forms a complex with nucleosomes, where the positions of the nucleosomes are shifted to the sides of the RFX5 bound sites (Fig. 4d, e). These results indicate that RFX5 prefers nucleosomal DNA in vivo, and that it potentially can induce nucleosome remodeling. In addition to RFX5, we also found that multiple SOX TFs have a preference for binding to dyad DNA (Fig. 4f, g). Such preference for SOX11 was validated with electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA; Extended Data Fig. 8). Taken together, our results indicate that on nucleosomal DNA, some TFs display a strong preference towards the dyad region.

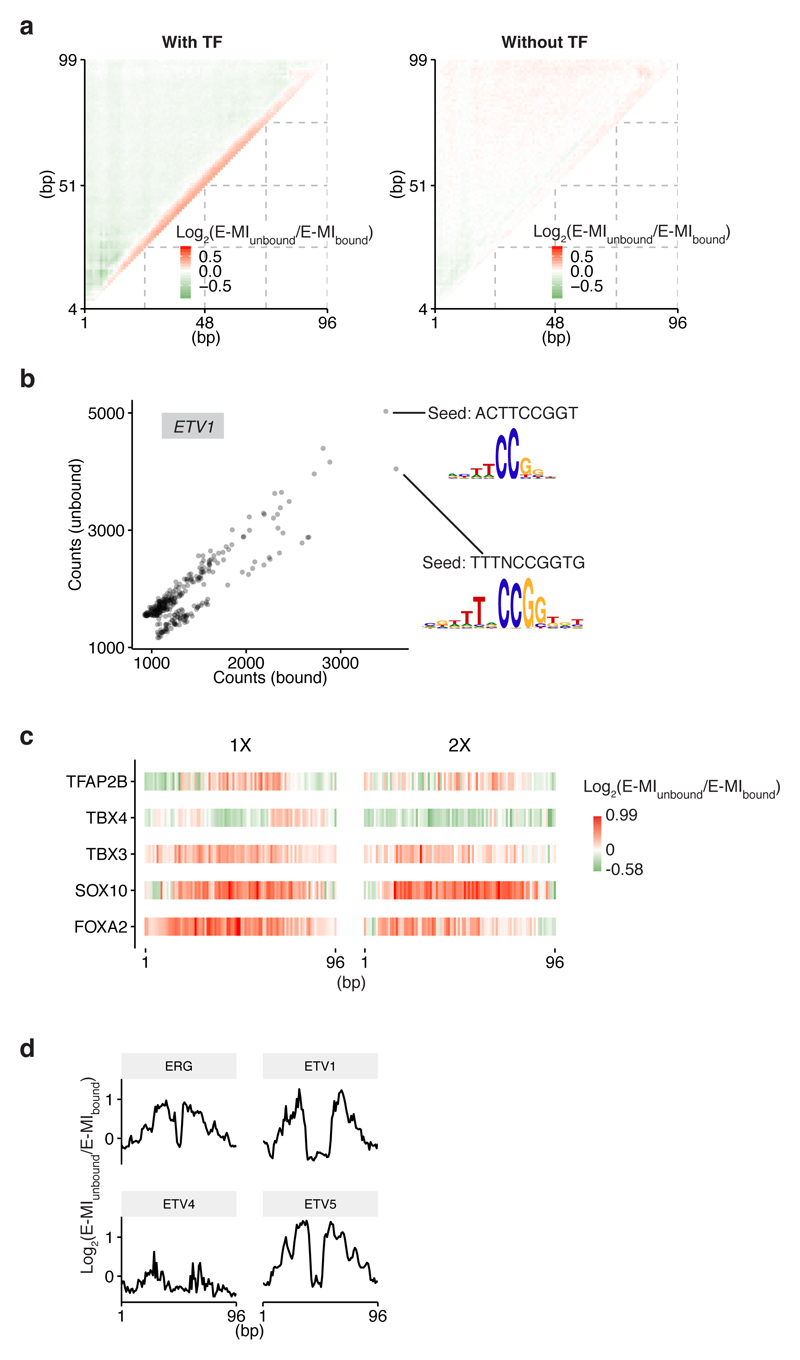

Effect of TF binding on nucleosome dissociation

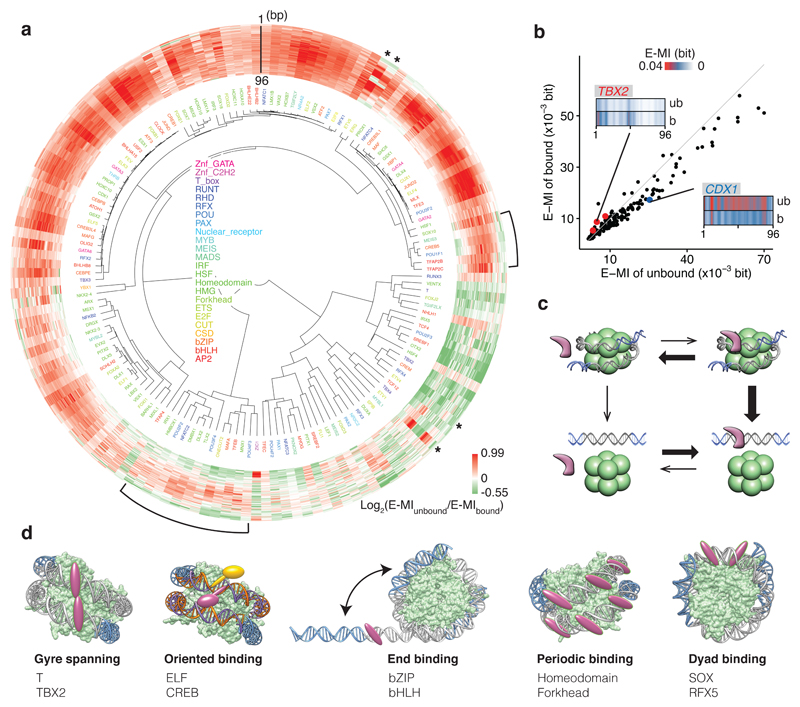

To determine whether TF binding affects the stability of the nucleosome, we performed an additional affinity capture step to separate the nucleosome-bound and dissociated DNA (unbound) in the last cycle of lig147 NCAP-SELEX (Fig. 1a; Fig. 5; Extended Data Fig. 9). Control experiments lacking TFs showed very little difference between the E-MI signal of the bound and unbound libraries, whereas in the presence of TFs, clear differences were observed (Fig. 5a; Extended Data Fig. 9a). We found that most TFs (e.g. CDX1) have stronger E-MI in the unbound library compared to that of the bound library, suggesting that they can facilitate nucleosome dissociation upon binding (Fig. 5b, c). However, we also identified a few exceptional TFs whose binding stabilized the nucleosome. These include the T-box TFs, such as TBX2 (Fig. 5b). Moreover, TFs’ effect on nucleosome stability is also dependent on their binding mode and position on the nucleosomal DNA (Fig. 5a; Extended Data Fig. 9).

Figure 5. Effects of TF binding on nucleosome stability.

a, Hierarchical clustering of the differential E-MI diagonal between the nucleosome-bound and the unbound cycle 5 libraries. Most TFs have stronger signal in the unbound library, indicating that their binding destabilizes the nucleosome. Brackets denote TFs that both destabilize and stabilize the nucleosome in a position-dependent way. Asterisks denote the ETS factors with a specific pattern of positional dependence. b, Mean strengths of E-MI diagonals in the nucleosome-bound and unbound cycle 5 libraries. The scatterplot shows the mean E-MI for the diagonals of each TF (dots), and for both the bound library (y axis) and the unbound library (x axis). The grey line represents where y=x. Most TFs have stronger signals in the unbound library (e.g. CDX1, blue). A few TFs show the reverse (e.g. TBX2, red, 3 replicates). For CDX1 and TBX2 the E-MI diagonals of the bound (b) and the unbound (ub) libraries are also illustrated. c, TF binding facilitates nucleosome dissociation. Binding of most TFs (magenta) to nucleosomal DNA leads to formation of a relatively unstable ternary complex (top right), and facilitates dissociation of the nucleosomes because the TFs prefer free DNA over nucleosomal DNA (bottom right). An alternative mechanism where the nucleosome first dissociates (left bottom) is not consistent with the observed effect of nucleosome on positional binding preferences of TFs (see also Fig 3). d, The identified major TF-nucleosome interaction modes.

Discussion

TFs and the nucleosome are central elements regulating eukaryotic gene expression. In this study, we developed a new method, NCAP-SELEX, for analysis of nucleosome-TF interactions, and systematically examined the binding preference of 220 TFs on nucleosomal DNA. We identified five major interaction patterns between TFs and the nucleosome (Fig. 5d; Extended Data Fig. 10; Supplementary Table 5). The interaction modes are consistent with structural considerations, and not mutually exclusive. They include (1) binding spanning the two gyres of nucleosomal DNA; (2) orientational preference; (3) end preference; (4) periodic preference; and (5) preferential binding to the dyad region.

Binding of most TFs facilitated the dissociation of nucleosomes. The simplest mechanism to explain this finding is that TFs bind to nucleosomal DNA and form a ternary complex. This complex is relatively unstable because the TFs prefer free DNA over nucleosomal DNA; this difference in affinity provides the free energy that facilitates dissociation of the nucleosome. Although the histone octamer binds 147 bp DNA more strongly than most TFs, within the ~ 10 bp segment that is bound by a TF, the bonds formed by the TF are stronger than those formed by histones. Therefore, binding of a TF to partially dissociated nucleosome can also prevent rewinding of the TF-bound DNA segment to the nucleosome.

The TFs that facilitate dissociation of nucleosome function as potential activators that can open chromatin and regulate gene expression. Some TFs, in turn, stabilized the nucleosome. These factors could repress gene expression, or to precisely position nucleosomes at specific genomic loci. Our findings are related to previous analyses that have identified pioneer TFs, which can access nucleosomal DNA11. However, our observations indicate that a binary classification of TFs is not sufficient to capture the complete diversity of the interaction landscape between TFs and the nucleosome. Taken together, our results explain in part the complexity of the relationship between sequence and gene expression in eukaryotes, and provide a basis for future studies aimed at understanding transcriptional regulation based on biochemical principles.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Experiment design and data analysis strategy of NCAP-SELEX.

a, Expression of the recombinant histones from X. laevis. For each lane 3 µg histone is loaded. Similar purifications for untagged H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 have been repeated for at least three times. The SBP-H2A purification was performed once. b, Size-exclusion chromatogram of the histone octamer. Such octamer formation has been performed twice and the results were highly consistent. c, EMSA result showing the reconstituted nucleosomes using lig147 and lig200. The original ligands are also loaded as reference. The asterisks indicate the nucleosome bands. Similar results are seen in four independent nucleosome reconstitutions. For gel source data see Supplementary Figure 1. d, Oligonucleotide periodicity in the library enriched by nucleosome. As a quality control of nucleosome reconstitution, we verified whether nucleosome by itself is enriching the previously reported ~10-bp periodic oligonucleotide signal41,42. Nucleosome SELEX (without TF) were carried out for four cycles to enrich nucleosome-favoring ligands. The counts of each single and di-nucleotide across each individual ligand were Fourier transformed and summed up for the whole library. A clear peak around 0.1 bp-1 (corresponding to the reported ~10-bp periodicity) is visible for most mono and dinucleotides. e, The C/G/CG preferences of nucleosome. All 9-mers were counted for the nucleosome-favored (bound) and the nucleosome-disfavored (unbound) libraries. The point representing each 9-mer is colored according to its C/G/CG content (top), and the count ratios between the bound and the unbound libraries are summarized for 9-mers of different C/G/CG contents (bottom). For the box plots grouped by C/G content, the sample sizes of the boxes are 19683, 59049, 78732, 61236, 30618, 10206, 2268, 324, 27, and 1, respectively for 9-mer groups containing 0 to 9 C/G. For the box plots grouped by CG dinucleotide content, the sample sizes of the boxes are 151316, 91824, 17784, 1200, and 20, respectively for 9-mer groups containing 0 to 4 CG. The line within each box represents the median; the lower and upper boundaries of the box indicate the first and third quartiles. The whiskers represent the 1.5-fold interquartile range. More extreme values are indicated with dots. f, Analysis pipeline for the ligands enriched in NCAP-SELEX. g, E-MI strength comparison for libraries with and without TF signals. The E-MI heatmaps represent signals in the input (cycle 0) library, in the cycle 4 library of nucleosome-favored sequences (Nucl. SELEX), and in the NCAP- and HT-SELEX cycle 4 libraries. The libraries enriched with TF (NCAP and HT) have much stronger E-MI signals compared to the cycle 0 and the nucleosome-SELEX library. The detected dimer signals of HSF1 in HT-SELEX is boxed. h, Family-wise coverage of TFs tried in NCAP-SELEX.

Extended Data Figure 2. NCAP-SELEX with lig200.

a, Hierarchical clustering of the E-MI diagonals for NCAP-SELEX with the 200-bp ligand (lig200). The E-MI diagonal for each TF is oriented radially. The randomized region is 154 bp and contains 149 windows for MI calculation between neighboring 3 mers. The names of the TFs are colored by family with the coloring scheme indicated on the center. TFs from the same family tend to be clustered together (e.g., SOX, indicated). Because of the gradient of nucleosome occupancy, the penetration of the E-MI signal into the center of the E-MI diagonals (E-MI penetration; see Methods for details) reflects the ability of each TF to bind to nucleosomal DNA. Note that almost all TFs have lower E-MI towards the center of lig200, indicating their lower affinity to nucleosomal DNA than to free DNA. Such decrease of E-MI towards the center is rarely observed in the absence of the nucleosome. Note that the binding inhibition of TF to nucleosomal DNA occurs in the absence of higher order effects, such as chromatin compaction, remodeling or histone modification. This results directly verifies the mutually antagonistic role of TFs and the nucleosome13,43,44, which was biochemically validated only for a few cases before45,46. The E-MI diagonals shown are scaled for each TF (see Methods). Due to the fixed adaptor sequences, TFs may prefer one end of the lig200 over the other end. b, E-MI penetration of individual TFs on lig200. TFs are ordered according to their E-MI penetration depth towards the center of the ligand. This order reflects TFs’ ability to bind nucleosome-occupied DNA. Note that the penetration of E-MI into the ligand center (E-MI penetration; see Methods for details) varies strongly between the TFs. TFs representing either of the two ends are colored red and exemplified in (c). c, The diagonal of E-MI for TFs with high (top) and low (bottom) E-MI penetrations. Because HT (blue) and NCAP-SELEX (black) may differ in stringency, each E-MI diagonal is normalized by dividing its maximum value. On lig200 the central 94 bp (shaded grey) is always occupied by a nucleosome. d, Correlation between E-MI penetration and TF’s capability to bind nucleosomal DNA in vivo. Per base-pair coverage of MNase fragments (>140 bp) at ChIP-seq peaks of the TFs (x axis) is plotted against their E-MI penetration (y axis) in NCAP-SELEX. The calculation of Pearson’s r and the correlation test is performed for n=20 TFs. The observed correlation suggests that TFs’ ability to bind nucleosomal DNA in NCAP-SELEX (E-MI penetration) partially explains the nucleosome occupancy at TFs’ sites in K562 cells. Thus the biochemical ability of TFs to bind to nucleosomal DNA also affects their binding in vivo. e, (Left) E-MI heatmap of T (brachyury) in HT-SELEX using lig200. Pairwise E-MI for all 3-mer pairs is presented as a heatmap. The signal is only visible near the diagonal, no E-MI signal across ~80 bp is detected. (Right) The gyre-spanning mode (arrow) of T (brachyury) on lig147. The corresponding motif is derived with the indicated seed for a specific position (number in the parentheses) in the high E-MI region (arrow). PWM generation follows our previous method47 using multinomial 1. f, Type 2 binding of Brachyury (T) stabilizes nucleosome from dissociation. Log2 ratio of E-MI between the bound and unbound libraries (cycle five) is calculated for both the Type 2 binding and for the background E-MI level (see Methods for details) of Brachyury (T). Compared to the unbound, the bound library has stronger Type 2 binding but a similar background. As a control, for 20 random TFs (Rnd), the log2 ratio of E-MI between the bound and unbound libraries is also calculated for both the Type 2 binding (hypothetic) and for the background E-MI level. For these TFs the bound libraries have similar E-MI strength as the unbound in the region corresponding to the Type 2 binding of Brachyury (T). Data are mean ± s.d.; two-sided t-test was used, 95% CI, 0.097–0.202 (T) and -0.008–0.004 (random TFs). The sample sizes are n=20 libraries for random TFs and n=4 independent SELEX replicates for Brachyury (T). The raw data for the random control TFs are listed in Supplementary Data 3. g, E-MI heatmap of TBX2, ETV4, and ETV1 in NCAP-SELEX using lig147. The E-MI signals across ~80 (type 2) or ~40 bp (type 1) are indicated with arrows. The corresponding motif of each binding type is derived with the indicated seed for a specific position (number in the parentheses) in the high E-MI regions (arrows). Note that the E-MI signals across ~40 bp are position-specific, with one binding event being observed near the dyad, and the other(s) on the opposite side of the nucleosome, with the two contacts separated by ~180°. This binding mode can be achieved by TF dimers that contact nucleosomal DNA in a pincer-like manner. However, as the individual TFs are located far from each other in this binding mode, it more likely suggests that the nucleosome may have two allosteric states, or may form a higher order complex with these TFs.

Extended Data Figure 3. Control experiments with lig200.

a, Determination of nucleosome positions for NCAP-SELEX libraries (lig200, all TFs). To examine if nucleosome has preferred positioning on lig200, nucleosomes were loaded onto the amplified cycle 4 NCAP-SELEX library of each TF. After digestion with MNase, the remaining DNA fragments were collected and sequenced. A titration was first carried out to find the appropriate concentration of MNase. As shown in the gel image (left, see Supplementary Figure 1 for source data), 4.8, 2.4, 1.2, 0.6, 0.3, 0.15 units of MNase (lane 1–6) were added into each 25 µl reaction containing the purified nucleosome. According to the results, the asterisk-marked condition was chosen for the reactions to determine nucleosome position. After sequencing, the fractions of MNase fragments that mapped to the variable region (grey) and to the adaptor-overlapping region (blue) of lig200 are visualized (middle, each row corresponds to a TF). To identify potential positional preference of nucleosome on lig200, the adaptor-overlapping fragments are analyzed for their end distributions. Distributions of both the left end (cyan) and the right end (red) of the MNase-digested fragments on lig200 are shown (right, each row correspond to a TF). Such distributions likely indicate that nucleosomes have two relatively preferred positions on lig200 (illustrated by cartoon in green). Note that most nucleosomes are not positioned by the adaptor (middle) thus are randomly distributed. b, E-MI diagonals for HT-SELEX with the 200-bp ligand (lig200). TFs are arranged according to the clustering for NCAP-SELEX libraries (Extended Data Fig. 2a) to facilitate comparison. TFs without a lig200 HT-SELEX control are left as blank. The E-MI diagonal for each TF is oriented radially and the names of the TFs are colored by family as indicated. The E-MI diagonals are scaled for each TF. Some TFs show preferred positions on lig200, likely due to the fixed adaptors. c, TFs prefer free DNA to the edge of a nucleosome. For a few randomly chosen TFs, NCAP-SELEX was run using a ligand (Lig70Nlinker, sequence in Supplementary Table 2) that positions nucleosome at its center by embedding a segment of Widom 601 sequence, and with randomized flankings. At a low resolution, TFs’ E-MI signal decreases monotonically towards the nucleosome-occupied region. Thus the higher E-MI at the flankings of lig200 (Extended Data Fig. 2a) suggests TFs’ preference for free DNA, rather than for the edge of a nucleosome. E-MI diagonals are scaled for each TF. d, E-MI diagonals for TFs at doubled concentrations. The concentration effect on TFs’ E-MI diagonal is explored by running NCAP-SELEX at doubled (2×) concentrations for a few randomly chosen TFs. Compared to the E-MI diagonal with the original TF concentrations (1×), the change on E-MI pattern is minor.

Extended Data Figure 4. Nucleosome breaks the rotational symmetry of DNA.

a, Density plot representing the orientational asymmetry of all TFs in NCAP-SELEX and in HT-SELEX. In NCAP-SELEX, more TFs bind with high orientational asymmetry than in HT-SELEX. A few TFs can prefer different ends of the ligand for the two binding directions in HT-SELEX; this is likely induced by the adaptor sequences. However, there are more TFs with higher orientational asymmetry in NCAP-SELEX libraries, despite the fact that for most TFs their signals are stronger in HT-SELEX libraries. b, Orientation asymmetry of ELF2 revealed by using top 8-mers. Each row of the heatmap corresponds to the counts distribution of a top 8-mer (non-palindromic) across the positions of the SELEX ligand. Hits of the top 8-mers occur at different ends for different strands of nucleosomal DNA (i.e. an 8-mer and its reverse-complement prefer different ends), whereas their distribution is relatively homogeneous for free DNA. c, Orientation asymmetry of CREB TFs. CREB TFs have different motif density distributions for the two strands of nucleosomal DNA. The motif used for matching is indicated above. The “–” strand profile is from the density of the reverse-complement motif. d, Break of the 2-fold rotational symmetry of DNA induces preferred orientation of TFs. Left: free DNA has a 2-fold axis (red ellipse) perpendicular to the helix axis. Motifs in two orientations are symmetric with each other with respect to a 180° rotation centered on the axis. Right: for motifs on nucleosomal DNA, if the other strand of DNA or the histone proteins (green) affects binding, the 2-fold axis of DNA no longer exists, as a 180° rotation centered on the axis no longer generates an identical conformation (the rotated image not superimposable with the original one). Such break of rotational symmetry occurs also on the linker DNA that immediately flanks the nucleosome (f). e, (Top panel) The orientational asymmetry of ELF2 in NCAP-SELEX of lig200. (Bottom panel) The asymmetric nucleosome distribution around genomic ELF1 sites (top). Such asymmetry is not observed for the same ELF1 sites after a 30 min 500 mM KCl treatment to mobilize the nucleosome (bottom). ELF1 motif matches are positioned at the center. Frequency of the center of MNase-fragments (140–170 bp) is visualized for nearby regions to represent the nucleosome occupancy. Each profile (n=999 data points) is LOESS smoothed with a span of 0.05 and plotted with the SE band. f, The orientational binding of ELF occurs on both the nucleosomal DNA and the nearby linker region. The motif matches of ELF on lig147 (top) suggest that the orientational binding occurs on nucleosomal DNA. In addition, the motif matches of ELF on the 293-bp ligand (bottom; nucleosome positioned at the center, ligand schematic in Extended Data Fig. 3c) indicates that the orientational binding also occurs on nearby linker DNA regions.

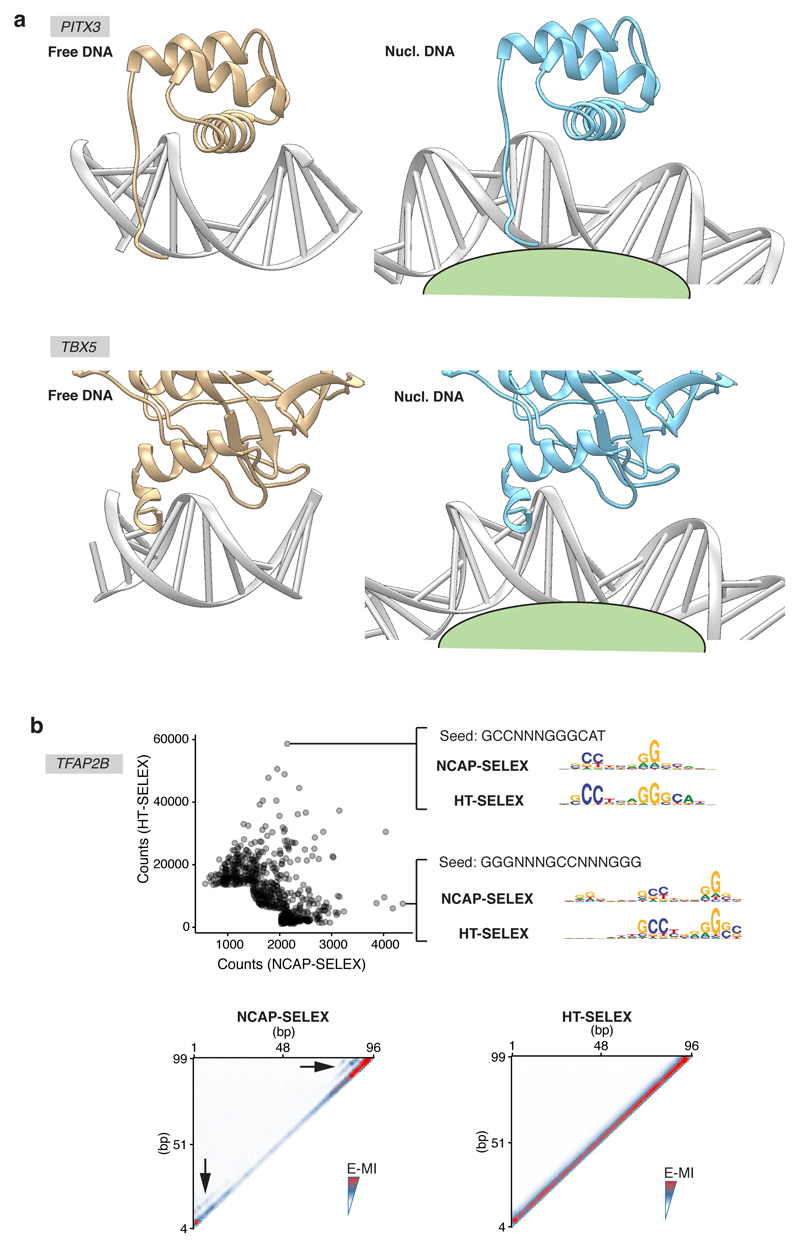

Extended Data Figure 5. TFs can bind nucleosomal DNA without significant motif change.

a, Cartoons showing that TFs are theoretically able to contact grooves of the bent nucleosomal DNA from the solvent-exposed side. The left panel for each TF shows the structures (PITX3: 2LKX, TBX5: 2X6V). For the right panels of each TF, the PDB structure of the TF is aligned to the nucleosome structure (3UT9) as described in the Methods (section “FFT analysis and structure alignment”). The corresponding base-pairs of the nucleosomal DNA were replaced with coot48 according to the DNA sequence in each TF’s PDB structure. The models are visualized with UCSF Chimera.49 b, TFAP binds nucleosomal DNA with slightly different specificity than free DNA. The scatter plot (top panel) shows the counts of gapped 9-mers from SELEX libraries of TFAP2B, enriched with NCAP-SELEX (x axis) and HT-SELEX (y axis). The examined 9-mers consists of three segments of trimers interspaced with two gaps (0–5 bp). Only the most enriched 9-mers (top 300 in each library and in the combined library) are shown from clarity. For comparison, the most differentially enriched gapped 9-mers were also used as seeds to derive the corresponding motifs from both libraries (right). The heatmap (bottom panel) shows the pairwise E-MI for all combinations of positions on lig147, in the presence (left) and absence (right) of nucleosome. The arrowheads indicate the additional signals developed in the presence of nucleosome.

Extended Data Figure 6. NCAP-SELEX with lig147.

a, E-MI diagonals for HT-SELEX with the 147-bp ligand (lig147). TFs are arranged according to the clustering for NCAP-SELEX libraries (Fig. 3a) to facilitate comparison. The E-MI diagonal for each TF is oriented radially and scaled. The names of the TFs are colored by family as indicated. b, The top five PCs (Principle Component) and the components from NMF (Non-negative Matrix Factorization) with rank equals 5. The E-MI diagonals of lig147 (n=195 TFs) were used in the dimension reduction. For visualization purpose, each component is centered and scaled. Note that the five PCs (left) correspond well to the three identified positional preferences of TFs on nucleosomal DNA (End: Dim 1, 2; Periodic: Dim 3, 4; Dyad: Dim 5). c, Comparison between the scores from PC classifiers and custom classifiers. Red points indicate the TFs defined as displaying respective preferences according to custom classifiers. The PC classifiers are well in accord with custom classifiers for the End and the Dyad preferences (left), but not for the Periodic preference (right). Because the phase of periodic preference can vary continuously whereas PCs can only capture discrete values, the custom FFT-based classifier is more natural for such purpose. The libraries of n=195 TFs were used in the analyses. The correlation coefficients (Pearson’s r) are also indicated. d, E-MI diagonal and motif matching results for the bZIP factor CEBPB. In HT-SELEX (without nucleosome), the binding signal is more distributed across the ligand. e, Pearson’s correlation between TFs’ E-MI penetrations on lig200 and on lig147. The libraries of n=155 TFs, which are successful with both lig200 and lig147, were used in this analysis. TFs’ end preference on lig200 reveals that they prefer free DNA to nucleosomal DNA. Such free-DNA preference likely also explains TFs’ end preference on lig147 due to the observed correlation of E-MI penetrations. For each TF, the E-MI penetration values differ between lig147 and lig200 because free-DNA regions are expected near the ends of lig200, but not present on lig147. f, Correspondence between TF’s E-MI patterns on lig147 and on 1ig200. The E-MI diagonals of RFX5 and SHOX on lig200 and those on lig147 are plotted together for comparison. The peaks on lig200 that illustrates the central preference of RFX5 and periodic preference of SHOX are indicated with red arrowheads. The weaker preference patterns on lig200 are due to the delocalization of the nucleosome on lig200, however still visible because the two fixed adaptors dictate two weakly preferred nucleosome positions.

Extended Data Figure 7. TFs with periodic preferences.

a, Density plot showing the periodicity strength of all TFs in NCAP-SELEX (orange) and HT-SELEX (blue). Note that the overall periodicity of E-MI is stronger for the NCAP-SELEX library compared to the free-DNA HT-SELEX library. b, Minor groove binder prefers exposed minor grooves (m) on nucleosomal DNA. The E-MI diagonal of EOMES (T-box) is out of phase with the TA peaks, suggesting it binds positions where nucleosomal DNA’s minor groove is facing outside (TA peaks indicate nucleosome-DNA contacts, whereas E-MI visualizes TF-DNA contacts, see Methods for details). Accordingly, the TBX5 (T-box) structure (PDB entry 2X6V) shows contacts with DNA principally in the minor groove. Cartoon representation to the right shows that the steric hindrance is minimal when TBX5 (blue) binds out of phase with TA (orange) on the nucleosome structure (PDB entry 3UT9). c, Strength and phase of the ~10 bp periodicity of TA dinucleotide in NCAP-SELEX and HT-SELEX libraries. For the library (lig147) enriched by a specific TF, the strength and phase information is derived from FFT of the TA counts at each position of the library. In the polar plot, each dot represents one TF’s library. The overall periodicity is stronger in the NCAP-SELEX libraries (yellow) than in the HT-SELEX libraries (blue), suggesting an enrichment of nucleosome signal. The TA phases in all TFs’ NCAP-SELEX libraries are similar, thus the rotational positioning of nucleosome on the SELEX ligand is similar for all TF’s libraries. In contrast, the phase of the E-MI periodicity is much more dispersed (Fig. 4a), suggesting the preference of TFs towards different grooves of DNA. d, Cartoon representations of the 3D structures of PITX3 (PDB entry 2LKX) and TBX5 (T_box, PDB entry 2X6V) in complexes with nucleosomal DNA. PITX3 and TBX5 structures were shown to illustrate the groove preferences of PITX2 and EOMES (T-box). The DNA ligand in the nucleosome structure (PDB entry 3UT9) contains phased TA steps (orange). Consistent with the SELEX result, PITX is more compatible with nucleosomal DNA when it binds in phase with TA, whereas T-box is more compatible when it binds out of phase with TA. Therefore, when TF binds nucleosomal DNA according to the identified patterns, the steric conflict between TF and the histones is minimized. e, E-MI diagonal and motif matching results for SHOX in NCAP-SELEX and HT-SELEX. The E-MI diagonal agrees with the motif matching result. f, The ~10 bp periodicity for the preferred spacing of SHOX dimers on nucleosomal DNA. In NCAP-SELEX libraries of many periodic binders (SHOX as an example), enrichment of the most abundant 3-mer tandem repeats oscillates as a function of the spacing between the repeats. The enrichment is evaluated by log2-ratio between the observed and expected occurrences. The observed ~10 bp periodicity with dimer spacing originates from the periodic availability of nucleosomal DNA. However, in most cases such binding appears not to be cooperative, based on the fact that the observed frequency of ligands with two motifs can be well estimated by the frequency of ligands that contain only one motif (data not shown). g, Homeodomain TFs from mouse liver prefer periodic positions on nucleosomal DNA. Motif hits of homeodomain TFs show a periodic pattern for both the nucleosome-bound and nucleosome-dissociated (unbound) libraries after incubation with mouse liver nuclear extract; however, the unbound library has more motif hits, indicating that binding events to the presented motif facilitates the dissociation of nucleosome. To more clearly visualized the ~10 bp periodicity, the Fourier-Transformed spectra for both libraries are also shown to the right. The arrowhead indicates the peaks for the ~10 bp periodicity.

Extended Data Figure 8. TFs with the dyad preference.

a, E-MI diagonal and motif matching results for RFX5. The distribution of binding events is more spread in the absence of nucleosome (HT-SELEX). b, The design of the competition assay and the raw counts of RFX5 motif matches. Differently barcoded nucleosomal DNA (orange) and free DNA (blue) were mixed as input, and incubated with the TF protein. Purification for the TF-bound species was then performed. Matches of the indicated RFX5 motif was counted for both the nucleosomal DNA (orange) and the free DNA (blue), and for both of the input and the bound libraries. On nucleosomal DNA, more motif hits near the center of the ligand are observed after purification. c, MNase-ChIP fragments near the binding sites of RFX5 and HOXB13. Motif matches within MNase-ChIP peaks of each TF are positioned at the center. Counts of MNase-ChIP fragments are binned to 3 bp by 3 bp bins according to their lengths and center positions. Nucleosome distribution is reflected by the signal intensity of the ~150 bp fragments (bracket). This visualization resembles the reported “V-plot”50. Length distribution of all ChIPed fragments and that of fragments < 300 bp from the TF sites are shown on the right. Note that HOXB13 enriches ~120 bp ChIP fragments at its sites (middle), suggesting that similarly to most TFs50,51, its binding sites in the genome are depleted of nucleosomes. In contrast, RFX5 enriches nucleosome-sized fragments (left). Most of the enriched fragments also have their center positioned between the red “V” lines, and thus overlap with the TF motifs. d, Nucleosome distribution near the binding sites of RFX5 and HOXB13 before transfection (no TF expression). MNase-seq fragments around the identified TF sites are visualized as in (c). The sites later bound by exogenous RFX5 are located at the maximum of nucleosome occupancy (left). e, Nucleosome distribution near the binding sites of RFX5 and HOXB13 after transfection (with TF expression). The nucleosomes are now positioned aside the exogenous RFX5 sites (left). f, EMSA of SOX11 complexes with nucleosome and with free DNA. Nucleosome is reconstituted and purified using a modified Widom 601 sequence, which contains a SOX11 binding sequence (extracted from cycle 4 SELEX library) embedded close to the dyad. Each 40 µl reaction contains 1 µg DNA, together with SOX11 protein at a molar ratio of 0, 0.5, 1, 2 (indicated on top of each lane) to DNA. Here the observed multiple shifts likely reveal the binding of SOX11 to additional weaker sites on the ligand (g). For gel source data, see Supplementary Figure 1. g, The score of SOX11 motif across the EMSA ligand (see Methods for ligand sequence). The top 3 binding sites are indicated. h, DNA shape features around SOX11 motifs. DNA shape features were calculated using DNAshapeR52,53, for NCAP-SELEX (black), HT-SELEX (blue), and cycle 0 (input, grey) libraries. The black line is plotted last thus may hide other lines when all values are similar. Boundary of the motif is indicated with dashed vertical lines. Only the ligands with motifs around the center (position range: 36-58) are included in the analysis.

Extended Data Figure 9. TF binding affects the stability of nucleosome.

a, E-MI difference between the bound and the unbound cycle 5 libraries. The bound and the unbound libraries were collected either in the presence (left) or in the absence (right) of TFs. The heatmaps visualize E-MI differences between the bound and unbound libraries for all position combinations of 3-mer pairs, and each pixel on the heatmap is a mean of all the examined TFs’ E-MI difference at this pixel. For individual TFs, value at each pixel is calculated as log2(E-MIunbound/E-MIbound). Testing nucleosome dissociation in the absence of TF was aimed to verify whether the TF motifs on lig147 by themselves can affect the nucleosome’s stability. Note that in general, binding events close to the center of nucleosomal DNA more efficiently dissociated the nucleosome (left). This observation is in accordance with the mutually exclusive nature between TFs and the nucleosome. While TFs generally have lower affinity to the center of the lig147, it is also conceivable that TF binding close to the center will more efficiently undermine the DNA-histone interactions, and in turn lead to a higher rate of nucleosome dissociation. TFs bound close to the ends could have decreased the flexibility of the DNA there and subsequently disfavor the dissociation of DNA ends from the histones, which in turn contributes to nucleosome stability. b, The efficiency of nucleosome dissociation induced by ETV1 is dependent on its binding specificity. To displace nucleosome, binding with the shorter motif is more efficient than binding with the longer motif, because the shorter motif is more enriched in the dissociated library (unbound). c, Differential E-MI diagonals for TFs at doubled concentrations. TF’s ability to dissociate or stabilize nucleosome is revealed by the log ratio of E-MI between the unbound and the bound cycle 5 libraries (differential E-MI). The concentration effect on TFs’ differential E-MI diagonal is explored by running NCAP-SELEX followed by the dissociation assay at doubled (2×) concentrations of the TFs. The differential E-MI diagonals at 2× TF concentrations resemble those at the original (1×) TF concentrations. d, Differential E-MI diagonals for the four ETS family TFs indicated by asterisks in Fig. 5a.

Extended Data Figure 10. Modes of TF-nucleosome interaction.

For each TF, the strengths of all identified TF-nucleosome interaction modes, together with its ability to dissociate nucleosome, are shown in the heat map (a). The displayed features include TF’s positional preferences (E: end, P: periodic, D: dyad) on nucleosomal DNA, gyre-spanning binding mode (Gs), orientational asymmetry (Asym), and TF’s ability to dissociate nucleosome (Ds). TFs succeeded only in NCAP-SELEX with lig200 are presented to the right for their orientational asymmetry. In the heatmap values are scaled into 0 to 1 for each mode, except for the dissociation, where TFs that stabilize nucleosome are given negative values (green). The raw data are provided in Supplementary Table 5. (b) All the identified modes can be explained by the structural features of nucleosome. TFs with the end preference (E) bind nucleosomal DNA close to the entry and exit positions. This preference is in line with the probability of spontaneous dissociation (breathing) of nucleosomal DNA, which decreases from the end to the center54–56. TFs with a strong end preference are likely less compatible with nucleosomal DNA thus only bind to the dissociated regions. These TFs could be structurally hindered by nucleosome, because one side of the nucleosomal DNA is masked by the histones. Moreover, nucleosomal DNA is bent sharply, which could impair TF-DNA contacts if TFs have evolved to specifically bind to free DNA. TFs with the periodic preference (P) binds every ~10.2 bp positions on nucleosomal DNA. This preference arises also because nucleosomal DNA is accessible only from one side, which leads to significant accessibility change along each pitch (~10.2 bp) of the DNA helix. TFs that bind to short motifs, or to discontinuous motifs, are still able to occupy the available periodic positions on nucleosomal DNA. TFs with the dyad preference (D) tend to bind close to the nucleosomal dyad. Structurally, the dyad is distinct from other regions of the nucleosomal DNA. The dyad contains only a single DNA gyre, and features the thinnest histone disk29,37. These characteristics of the dyad DNA reduce the steric barrier for TF binding. The relatively weak DNA-histone interaction around the dyad could allow TFs that bend DNA upon binding (e.g., SOXs57) to deform DNA more easily at the dyad compared to other positions. In addition, the entry and exit of nucleosomal DNA are also close to the dyad; together with the dyad DNA, they provide a scaffold for specific configurations of TFs. FOXA has been suggested to make use of this scaffold to achieve highly specific positioning close to the dyad39,58. However, the dyad positioning of FOXA is not observed in this study using eDBD, potentially because the full length of FOXA is required for its interaction with the nucleosome59. A few T-box TFs were found to bind nucleosomal DNA with the gyre-spanning binding mode (Gs). Such mode is observed because DNA grooves align across the two nucleosomal DNA gyres29. The parallel gyres could specifically associate with TF dimers, or TFs having long recognition helices or multiple DNA binding domains. The dual-gyre binding is possible only on nucleosomal DNA, and it thus stabilizes the nucleosome from dissociation, and may therefore function to lock a nucleosome in place at a specific position. Many TFs such as ETS and CREB show an orientational asymmetry (Asym) upon binding to the nucleosomal DNA. The nucleosomal environment has induced such preference by breaking the local rotational symmetry of DNA. In accord with the mutually exclusive nature between TF and nucleosome binding, most TFs were found to dissociate nucleosomes (Ds). While nucleosome weakens the affinity of incompatible TFs, binding of such TFs are expected to weaken the nucleosome-DNA contacts as well. The ability of TFs to dissociate nucleosome is required for them to open chromatin and to activate transcription. Moreover, we also observed TFs that both stabilize and destabilize nucleosomal DNA, depending on their relative position of binding. Such ability could be used to more precisely position local nucleosomes. All the identified TF-nucleosome interactions suggest that the TF-nucleosome interaction could be more complicated than the previously suggested pioneer/non-pioneer classification of TFs11. We observed that for eDBD of almost all TFs, including known pioneer factors such as FOX and SOX, free DNA was nonetheless preferred than nucleosomal DNA. However, some pioneer factors can bind relatively better to the interior of the nucleosome (e.g. FOX and SOX). In addition, some other TFs prefer nucleosomal DNA at restricted positions, or with one of their multiple binding motifs. These strategies are likely related to pioneer factor’s access to nucleosomal DNA.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Acknowledgments

We thank F. Zhong, A. Jolma, J. Zhang, and J. Toivonen for valuable suggestions, E. Inns for proofreading, T. Kivioja for critical review of the manuscript, and L. Hu, J. Liu, and S. Augsten for technical assistance. Funding, J.T.: EU Horizon 2020 project MRGGrammar (664918), Cancerfonden (120529, 150662), Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (2013.0088), Vetenskapsrådet (D0815201), Academy of Finland CoE (312042); P.C.: DFG (SFB860, SPP1935), ERC AdG TRANSREGULON (693023), Volkswagen Foundation; S.D.: EMBO fellowship ALTF 949-2016.

Footnotes

Author Contributions J.T., F.Z. and P.C. conceived the experiments. F.Z. performed most experiments and analyses. L.F. produced the histone octamers. B.S. and E.K. contributed to generation and analysis of the MNase-seq and ChIP-seq data, respectively. B.W. and S.D. performed SOX EMSA and the binding assay with nuclear proteins, respectively. Y.Y. contributed to protein production and motif analysis. M.T., K.N. and E.M contributed to design and analysis of sequencing and structure data. F.Z. and J.T. interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the findings and contributed to the manuscript.

Author Information Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints. All next-generation sequencing data have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under accession PRJEB22684.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Andrews AJ, Luger K. Nucleosome structure(s) and stability: variations on a theme. Annu Rev Biophys. 2011;40:99–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-042910-155329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Segal E, Widom J. What controls nucleosome positions? Trends Genet. 2009;25:335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richmond TJ, Davey CA. The structure of DNA in the nucleosome core. Nature. 2003;423:145–150. doi: 10.1038/nature01595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGinty RK, Tan S. Nucleosome structure and function. Chem Rev. 2015;115:2255–2273. doi: 10.1021/cr500373h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jin J, et al. Synergistic action of RNA polymerases in overcoming the nucleosomal barrier. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:745–752. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raveh-Sadka T, et al. Manipulating nucleosome disfavoring sequences allows fine-tune regulation of gene expression in yeast. Nat Genet. 2012;44:743–750. doi: 10.1038/ng.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teves SS, Weber CM, Henikoff S. Transcribing through the nucleosome. Trends Biochem Sci. 2014;39:577–586. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartzog GA. Transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13:119–126. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(03)00024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thurman RE, et al. The accessible chromatin landscape of the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:75–82. doi: 10.1038/nature11232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neph S, et al. An expansive human regulatory lexicon encoded in transcription factor footprints. Nature. 2012;489:83–90. doi: 10.1038/nature11212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zaret KS, Mango SE. Pioneer transcription factors, chromatin dynamics, and cell fate control. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2016;37:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Segal E, Raveh-Sadka T, Schroeder M, Unnerstall U, Gaul U. Predicting expression patterns from regulatory sequence in Drosophila segmentation. Nature. 2008;451:535–540. doi: 10.1038/nature06496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirny LA. Nucleosome-mediated cooperativity between transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:22534–22539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913805107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyer LA, et al. Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2005;122:947–956. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roy S, et al. Identification of functional elements and regulatory circuits by Drosophila modENCODE. Science. 2010;330:1787–1797. doi: 10.1126/science.1198374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stanojevic D, Small S, Levine M. Regulation of a segmentation stripe by overlapping activators and repressors in the Drosophila embryo. Science. 1991;254:1385–1387. doi: 10.1126/science.1683715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan J, et al. Transcription factor binding in human cells occurs in dense clusters formed around cohesin anchor sites. Cell. 2013;154:801–813. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yin Y, et al. Impact of cytosine methylation on DNA binding specificities of human transcription factors. Science. 2017;356 doi: 10.1126/science.aaj2239. eaaj2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jolma A, et al. DNA-dependent formation of transcription factor pairs alters their binding specificity. Nature. 2015;527:384–388. doi: 10.1038/nature15518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaquerizas JM, Kummerfeld SK, Teichmann SA, Luscombe NM. A census of human transcription factors: function, expression and evolution. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:252–263. doi: 10.1038/nrg2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soufi A, et al. Pioneer transcription factors target partial DNA motifs on nucleosomes to initiate reprogramming. Cell. 2015;161:555–568. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nodelman IM, et al. Interdomain communication of the Chd1 chromatin remodeler across the DNA gyres of the nucleosome. Mol Cell. 2017;65:447–459. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edayathumangalam RS, Weyermann P, Gottesfeld JM, Dervan PB, Luger K. Molecular recognition of the nucleosomal “supergroove”. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6864–6869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401743101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faial T, et al. Brachyury and SMAD signalling collaboratively orchestrate distinct mesoderm and endoderm gene regulatory networks in differentiating human embryonic stem cells. Development. 2015;142:2121–2135. doi: 10.1242/dev.117838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lolas M, Valenzuela PDT, Tjian R, Liu Z. Charting Brachyury-mediated developmental pathways during early mouse embryogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:4478–4483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402612111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kundaje A, et al. Ubiquitous heterogeneity and asymmetry of the chromatin environment at regulatory elements. Genome Res. 2012;22:1735–1747. doi: 10.1101/gr.136366.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherwood RI, et al. Discovery of directional and nondirectional pioneer transcription factors by modeling DNase profile magnitude and shape. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:171–178. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dunham I, et al. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Isaac RS, et al. Nucleosome breathing and remodeling constrain CRISPR-Cas9 function. Elife. 2016;5:e13450. doi: 10.7554/eLife.13450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poirier MG, Bussiek M, Langowski J, Widom J. Spontaneous access to DNA target sites in folded chromatin fibers. J Mol Biol. 2008;379:772–786. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaney BA, Clark-Baldwin K, Dave V, Ma J, Rance M. Solution structure of the k50 class homeodomain PITX2 bound to DNA and implications for mutations that cause Rieger syndrome. Biochemistry. 2005;44:7497–7511. doi: 10.1021/bi0473253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stirnimann CU, Ptchelkine D, Grimm C, Muller CW. Structural basis of TBX5-DNA recognition: the T-Box domain in its DNA-bound and -unbound form. J Mol Biol. 2010;400:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coll M, Seidman JG, Muller CW. Structure of the DNA-bound T-box domain of human TBX3, a transcription factor responsible for ulnar-mammary syndrome. Structure. 2002;10:343–356. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00722-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cui F, Zhurkin VB. Rotational positioning of nucleosomes facilitates selective binding of p53 to response elements associated with cell cycle arrest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:836–847. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Q, Wrange O. Accessibility of a glucocorticoid response element in a nucleosome depends on its rotational positioning. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4375–4384. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGinty RK, Tan S. Recognition of the nucleosome by chromatin factors and enzymes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2016;37:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2015.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou BR, et al. Structural mechanisms of nucleosome recognition by linker histones. Mol Cell. 2015;59:628–638. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iwafuchi-Doi M, et al. The pioneer transcription factor FoxA maintains an accessible nucleosome configuration at enhancers for tissue-specific gene activation. Mol Cell. 2016;62:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Struhl K, Segal E. Determinants of nucleosome positioning. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:267–273. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zaret KS, Mango SE. Pioneer transcription factors, chromatin dynamics, and cell fate control. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2016;37:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirny LA. Nucleosome-mediated cooperativity between transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:22534–22539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913805107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGinty RK, Tan S. Recognition of the nucleosome by chromatin factors and enzymes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2016;37:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2015.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iwafuchi-Doi M, et al. The pioneer transcription factor FoxA maintains an accessible nucleosome configuration at enhancers for tissue-specific gene activation. Mol Cell. 2016;62:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Collings CK, Fernandez AG, Pitschka CG, Hawkins TB, Anderson JN. Oligonucleotide sequence motifs as nucleosome positioning signals. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10933. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lowary PT, Widom J. New DNA sequence rules for high affinity binding to histone octamer and sequence-directed nucleosome positioning. J Mol Biol. 1998;276:19–42. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramachandran S, Henikoff S. Transcriptional regulators compete with nucleosomes post-replication. Cell. 2016;165:580–592. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li M, et al. Dynamic regulation of transcription factors by nucleosome remodeling. Elife. 2015;4:e06249. doi: 10.7554/eLife.06249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sekiya T, Muthurajan UM, Luger K, Tulin AV, Zaret KS. Nucleosome-binding affinity as a primary determinant of the nuclear mobility of the pioneer transcription factor FoxA. Genes Dev. 2009;23:804–809. doi: 10.1101/gad.1775509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hayes JJ, Wolffe AP. Histones H2A/H2B inhibit the interaction of transcription factor IIIA with the Xenopus borealis somatic 5S RNA gene in a nucleosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1229–1233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jolma A, et al. Multiplexed massively parallel SELEX for characterization of human transcription factor binding specificities. Genome Res. 2010;20:861–873. doi: 10.1101/gr.100552.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF chimera - A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Henikoff JG, Belsky JA, Krassovsky K, MacAlpine DM, Henikoff S. Epigenome characterization at single base-pair resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:18318–18323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110731108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kasinathan S, Orsi GA, Zentner GE, Ahmad K, Henikoff S. High-resolution mapping of transcription factor binding sites on native chromatin. Nat Methods. 2014;11:203–209. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chiu TP, et al. DNAshapeR: an R/Bioconductor package for DNA shape prediction and feature encoding. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:1211–1213. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chiu TP, Rao S, Mann RS, Honig B, Rohs R. Genome-wide prediction of minor-groove electrostatic potential enables biophysical modeling of protein-DNA binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:12565–12576. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Polach KJ, Widom J. Mechanism of protein access to specific DNA sequences in chromatin: a dynamic equilibrium model for gene regulation. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:130–149. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anderson JD, Widom J. Sequence and position-dependence of the equilibrium accessibility of nucleosomal DNA target sites. J Mol Biol. 2000;296:979–987. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li G, Levitus M, Bustamante C, Widom J. Rapid spontaneous accessibility of nucleosomal DNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:46–53. doi: 10.1038/nsmb869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Privalov PL, Dragan AI, Crane-Robinson C. The cost of DNA bending. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:464–470. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ye ZQ, et al. Genome-wide analysis reveals positional-nucleosome-oriented binding pattern of pioneer factor FOXA1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:7540–7554. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cirillo LA, et al. Opening of compacted chromatin by early developmental transcription factors HNF3 (FoxA) and GATA-4. Mol Cell. 2002;9:279–289. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00459-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.