Abstract

Protein tyrosine sulfation (PTS), catalyzed by membrane-anchored tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase (TPST), is one of the most common post-translational modifications of secretory and transmembrane proteins. PTS, a key modulator of extracellular protein–protein interactions, accounts for various important biological activities, namely, virus entry, inflammation, coagulation, and sterility. The preparation and characterization of TPST is fundamental for understanding the synthesis of tyrosine-sulfated proteins and for studying PTS in biology. A sulfated protein was prepared using a TPST-coupled protein sulfation system that involves the generation of the active sulfate 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) through either PAPS synthetase (PAPSS) or phenol sulfotransferase. The preparation of sulfated proteins was confirmed through radiometric or immunochemical assays. In this study, enzymatically active Drosophila melanogaster TPST (DmTPST) and human TPSTs (hTPST1 and hTPST2) were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) host cells and purified to homogeneity in high yield. Our results revealed that recombinant DmTPST was particularly useful considering its catalytic efficiency and ease of preparation in large quantities. This study provides tools for high-efficiency, one-step synthesis of sulfated proteins and peptides that are useful for further deciphering the mechanisms, functions, and future applications of PTS.

Introduction

Protein tyrosine sulfation (PTS), one of the most common post-translational modifications (PTMs), was first reported in 1954.1 PTS occurs in the trans-Golgi network, and the sulfated proteins and peptides are typically transmembrane or secretory proteins.2 Tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase (TPST) (Enzyme Commission number: 2.8.2.20) is a type II membrane enzyme that is delineated to transfer the sulfuryl group from 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) onto a specific tyrosine residue within target proteins and peptides. This reaction is widespread in multicellular eukaryotic organisms, and TPST can be detected in most tissues and cell types in humans and rats.3,4 Total sulfated proteins were speculated to account for approximately 1% of tyrosine residues in an organism.5 To date, approximately 300 proteins are identified to be sulfated proteins.6 Most of these proteins and peptides have been implicated in the intracellular trafficking and proteolytic processing of secreted proteins. The sulfate group can be recognized through PTS and has been identified as a key modulator of extracellular protein–protein interactions (PPIs), which involve hormonal regulation, hemostasis, inflammation, and infectious diseases.6−8 PTM is believed to alter the strength of PPIs and further modulate ligand–receptor binding, intercellular communication, and signaling.2,9,10 A recent proteome chip study showed that sulfated proteins can be prepared on a chip by a TPST-catalyzed reaction.11

The preparation of TPST from Golgi-enriched membrane fractions was reported previously.12 However, both TPSTs (TPST1 and TPST2) were likely to be copurified from the procedures, and methods for separating TPST1 and TPST2 have not been reported.13 Moreover, the concentration of TPSTs is not high in the original crude extract, and TPSTs in a mixture may affect the efficiency of PTS. The preparation of recombinant TPSTs can markedly increase the concentration of the target enzyme and also ensure the preparation of the desired enzyme. TPSTs in humans and mice have been reported to be first identified through molecular cloning.14−16 Since then, similar studies have revealed recombinant TPSTs in other species, namely, Drosophila melanogaster, Danio rerio, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Arabidopsis thaliana.17−20

PTS is crucial for regulating various biological reactions and has become a target for drug design. A sulfated chemokine receptor (C–C chemokine receptor type 5, CCR5) interacts with envelope glycoprotein 120 (gp120) of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), which facilitates HIV-1 entry into cells. Tyrosine-sulfated peptides derived from gp120 potently block HIV-1 entry by mimicking the N-terminus structure of CCR5.21 The salivary gland of leech secretes hirudin, a potent anticoagulant protein. PTS on hirudin enhances its interaction with thrombin, and sulfated hirudin has become an effective drug for preventing thrombin-induced blood coagulation.22 The preparation of sulfated proteins and peptides is essential for studying PTS-related diseases. Table 1 summarizes methods for preparing sulfated proteins and peptides.

Table 1. Methods for the Preparation of Sulfated Proteins/Peptidesa.

| method | target | advantages | disadvantage | refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fmoc-based solid-phase strategy | peptide | well-controlled on peptide sulfation site | cumbersome procedure, limited to small peptide, difficulty for production of multiple sulfotyrosine | (23) |

| expanded genetic code | protein | well-controlled on protein sulfation site | cumbersome procedure, techniques not wildly available, inconsistent yield | (24) |

| prokaryotic expression system | protein | require only standard techniques in molecular biology | difficultly of plasmid coexpression | (25) |

| in vitro coupled-enzyme system (this study) | protein/peptide | simple and efficient for both protein and small peptide | preparation of required enzymes needed | this study |

This table summarizes and compares previously reported methods with the methods used in the present study.

Commercially available sulfated peptides are prepared through 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl-based solid-phase peptide synthesis involving sulfotyrosine residues.23 This chemical synthesis method reveals the exact position of the sulfated tyrosine residue in a peptide. The procedure involves cumbersome protection and deprotection of functional groups and is thus limited to the synthesis of small peptides. Moreover, acidic deprotection conditions often result in desulfation, which complicate the preparation of multiple sulfotyrosine residues in a peptide.23 Non-native sulfated peptides that may not exist in a biological system can also be obtained using this method. A study expanded the genetic code method and reported the direct cotranslational expression of sulfated tyrosine proteins in Escherichia coli.24 The PTS site can be specifically designed by introducing the amber nonsense codon to encode a sulfated tyrosine residue. In contrast to the previously described chemical synthesis of sulfated peptides, this method is favorable for synthesizing mid-sized proteins but not small peptides. In addition, the expanded genetic code method requires cumbersome procedures for plasmid construction, sulfotyrosyl t-RNA synthesis, and E. coli modification. The efficient expression of the sulfated protein is also challenging because the sulfated protein may affect the E. coli growth.24 Another method for producing biologically active sulfated proteins has been developed by implanting an artificial PTS system in E. coli.25 This prokaryotic sulfated protein-generating system involves the coexpression of two plasmids: one pertaining to the expression of the PTS system and the other pertaining to the expression of the target protein. The implementation of this system requires only standard molecular biology techniques; however, the expression of the sulfated protein may have limitations similar to those described for the expanded genetic code method. Therefore, an efficient and direct method is required for the in vitro production of biologically active proteins and peptides. The sulfated proteins and peptides can be monitored using radioactive, immunochemical, and fluorescent assays.26−29,17

In this study, we prepared recombinant TPSTs that catalyze the proteins and peptides in PTS with high efficiency. The P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) peptide or its fusion protein was used as the target for PTS reaction.13,17,18,25 PSGL-1 is a glycoprotein found on the plasma membrane of neutrophils or monocytes. There are three potential tyrosine sulfation sites at the amino terminus of PSGL-1.30 To rapidly obtain substrates of high purity, tyrosine substrates were purified using the glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion tag. The PTS level was negligible on GST, and the TPST activity on GST–PSGL-1 was not affected by the GST fusion tag (Figure S1). The GST fusion tag could be an excellent tool for the purification of other types of PTS substrates.31,32 According to the catalyst efficiency results, we established an optimal sulfated protein and peptide system. Herein, we report the in vitro synthesis of sulfated proteins and peptides by using a coupled enzyme system that does not involve cumbersome chemical synthesis and may avoid uncertainties in a cell. This system requires enzymes to catalyze the synthesis of activated sulfate compounds and the transfer of the activated compounds to the target proteins and peptides. The final sulfated proteins and peptides can be synthesized by simply incubating all required ingredients in a batch. Thus, this method is a direct and easy process for preparing biologically active sulfated proteins and peptides.

Results and Discussion

Sequence Comparison among hTPST1, hTPST2, and DmTPST

All known TPST-containing organisms, except for D. melanogaster, have two TPSTs.2,16 Notably, these TPSTs differ in their sequence and enzymatic properties. We selected three TPSTs in our study. Figure 1 shows the protein sequences of hTPST1, hTPST2, and DmTPST, which share approximately 60% identity with a similar length. Both hTPSTs and DmTPST show α-helical transmembrane proteins comprising highly hydrophobic domains in the amino terminus. According to the topological analysis of the primary sequence (Figure 1), the transmembrane region is marked in red on the N terminus of TPSTs. The transmembrane regions have low sequence identity (Figure 1), which increases to approximately 75% among these TPSTs after the exclusion of this domain sequence. Truncated hTPST2 without the transmembrane domain has been reported to be secreted by stably transfected Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells.14,15 Human and rat TPSTs have been identified and characterized in human saliva and rat submandibular salivary glands, respectively.33,34 The hydrophobic domain is likely to reduce the protein solubility and thus interfere with protein folding and purification. In our study, the hydrophobic transmembrane domains of hTPSTs and DmTPST were truncated, and only the catalytic domains of the TPSTs were expressed.

Figure 1.

Sequence analysis of TPSTs from humans and D. melanogaster. The pairwise sequence alignment was performed by ClustalW (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw2/index.html) and sorted and shaded by the BOXSHADE web server (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/BOX_form.html). The black background indicates identical amino acids, and the gray one indicates conserved substitutions. The residue colored in red is the predicted transmembrane domain calculated by PSIPRED (http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/psipred/psiform.html) and ranged from residues 6 to 28 for both human TPST1 and TPST2 and from 12 to 28 for D. melanogaster TPST. The pairwise sequence identities of these TPSTs were 57, 56, and 65% for DmTPST–hTPST1, DmTPST–hTPST2, and hTPST1–hTPST2, respectively. In the absence of the transmembrane region, the sequence identity of the catalysis domain increased to approximately 75%.

Expression and Purification of Recombinant TPSTs

To facilitate the expression and purification of stable and active TPSTs, we removed the TPST transmembrane domain and fused it with various tags and fusion proteins with expression vectors (Table 2). In our study, the highest expression of soluble TPSTs was achieved using the pET-43.1a expression vector that contains N-utilization substance protein A (NusA) insertion. In hTPST2 construction, we closed the his-tag on the 5′ end of pET-43.1a for complete expression. The prokaryotic expression condition was further optimized at 20 °C for 24 h to achieve the maximal soluble amount of TPST and was purified to near homogeneity (Figure 2). Similar results were obtained for the expression and purification of NusA–hTPST1, NusA–hTPST2, and NusA–DmTPST. In this paper, the NusA-fusion TPSTs are abbreviated for DmTPST, hTPST1, and hTPST2. In a typical experiment, 15.3 mg (DmTPST), 5.7 mg (hTPST1), and 4 mg (hTPST2) of the purified TPST fusion proteins were obtained from 1 L cell culture (Table 3). This is the first detailed report on the expression and purification of active recombinant TPSTs prepared from prokaryotic expression. Prokaryotic expressions of TPST reported previously resulted in an inactive form and refolding is needed.35,36 TPSTs have been expressed in many eukaryotic systems such as HEK293-T, CHO, and SF9 insect cells and yeast.14,15,20,37 The prokaryotic expression system generally provides high expression of the target protein; in addition, the plasmid can be easily constructed for the expression of heterologous enzymes. It has been shown that coexpression of the enzyme system and the protein substrate can be achieved in the same prokaryotic expression system and the sulfated protein is produced simultaneously.25 This system can be very useful for both academic researchers and the future industrial applications to produce desired properly sulfate-modified proteins.

Table 2. Vectors Used for TPST Expressiona.

| vector | fusion tagb | result |

|---|---|---|

| pGEX-4T1 | GST fusion | low solubility |

| pET-22a | signal peptide | low solubility |

| pET-30a | his-tag, S-tag | low solubility |

| pET-32a | Trx fusion, his-tag, S-tag | low solubility |

| pET-39a | Dsba fusion, his-tag, S-tag | low solubility |

| pET-41a | GST fusion, his-tag, S-tag | soluble form with GroEL contamination |

| pET-43.1a | NusA fusion, his-tag x2, S-tag | soluble form |

| pET-44a | NusA fusion, his-tag x2, S-tag | soluble form with NusA contamination |

Commercially available expression vectors were used to determine the solubility of TPSTs, following prokaryotic expression in E. coli. Modifications based on these vectors are described in the text.

The fusion tags are abbreviated as follows: GST: glutathione S-transferase; his-tag: hexahistidine peptide; S-tag: the 15-aa peptide, which interacts with ribonuclease S protein; Trx: thioredoxin; DsbA: disulfide oxidoreductase, which can be used to export recombinant protein into the periplasm; NusA: N-utilization substance protein A.

Figure 2.

Plasmid construction, expression, and purification of recombinant TPSTs. (A) Schematic of recombinant TPSTs in fusion proteins. DmTPST and hTPST1 were expressed as NusA at the N-terminal fused protein containing two his-tags. hTPST2 was also expressed with NusA as only one his-tag at the N terminus. The calculated molecular weight of the TPST fusion protein was approximately 96 kDa. (B) SDS–PAGE of recombinant TPST before and after purification for DmTPST, hTPST1, hTPST2, and their crude extracts. Lane “C-” indicates crude extracts. Lane M is the standard protein molecular weight marker. The arrowheads indicate TPSTs.

Table 3. Purification of Recombinant TPSTsa.

| enzyme | step | total protein (mg) | total activity (OD450nm/min)b | specific activity (OD450nm/min/mg)c | yield (%)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DmTPST | crude extract | 364 | 50.4 | 0.14 | 24 |

| Ni-NTA column | 15 | 12.2 | 0.79 | ||

| hTPST1 | crude extract | 278 | 25.2 | 0.09 | 13 |

| Ni-NTA column | 6 | 3.3 | 0.57 | ||

| hTPST2 | crude extract | 328 | 3.4 | 0.01 | 15 |

| Ni-NTA column | 4 | 0.5 | 0.13 |

Procedures for the expression and purification of TPSTs are provided in the Materials and Methods section.

Enzyme activity was measured based on the PAPSS–TPST coupled enzyme assay by ELISA, with GST–PSGL-1 serving as the substrate. The total activity was calculated according to the specific activity results.

The specific activity was determined according to the results of the HRP-produced signal per minute at OD450nm. GST–PSGL-1 was used as the substrate; the TPST reaction time and amount were 60 min and 10 μg, respectively.

The purification yield was calculated according to the total activity results.

In this study, DmTPST was observed to yield superior results in terms of the total enzyme and its activity. Furthermore, we observed that NusA is critical in the recombinant fused TPST protein not only for promoting its expression but also for strengthening its stability (Figure S2 and Table S2). Thus, NusA-fused TPSTs are suitable for the large-scale synthesis of sulfated proteins/peptides in vitro that often requires prolonged incubation time. In particular, we found that DmTPST is a suitable catalyst for organic synthesis because its enzymatic activity and quantity following prokaryotic expression were much higher than those of NusA-fused human TPSTs (Table 3).

Enzymatic Synthesis of Sulfated Proteins/Peptides

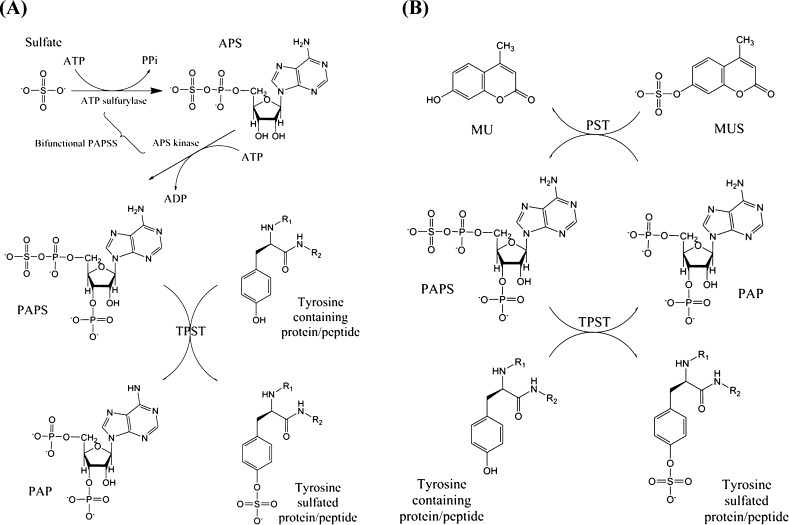

Figure 3 shows two schemes, both of which exploit coupled enzyme activities to accumulate the PAPS sulfonate donor that was subsequently used to generate TPST-catalyzed sulfated proteins/peptides. TPST activity was frequently evaluated using the radioactive-labeled PAPS; however, commercial PAPS is typically contaminated with considerable amounts of PAP.38 PAP is a potent product inhibitor of many sulfotransferases, and it might engender a low catalytic efficiency of TPSTs, as previously reported.25 In the first PAPSS–TPST scheme (Figure 3A), PAPSS was used to catalyze the generation of PAPS from ATP and SO42–.39,40 The advantage of this method is that the radioactive-labeled PAPS and the resulting sulfated proteins/peptides can be obtained directly from inorganic sulfate. The enzyme kinetics of TPST was also determined easily by the PAPSS–TPST system. Figure 3B presents the second scheme for the preparation of sulfated proteins/peptides. In such a scheme, PAPS is regenerated through phenol sulfotransferase-catalyzed MUS and PAP.41 The advantage of this method is that the progress of protein sulfation can be continuously monitored by a fluorometer because of the production of 4-methylumbilliferone (MU), a fluogenic compound, from MUS.17 Excess phenol sulfotransferase was included in the reaction mixture to catalyze the transfer of the sulfonate group from MUS to PAP and to regenerate PAPS required for PTS. Thus, the increase in the fluorescence signal of MU (excitation: 360 nm and emission peak: 450 nm) reflects the amount of PTS. Unlike the previous scheme, the concentration of PAPS can be stably controlled under this assay condition. According to Chen et al., this factor makes the second scheme an excellent strategy for determining the enzyme kinetics of TPSTs.17 In principle, both approaches (Figure 3) could eventually yield the desired sulfated proteins/peptides; however, their efficiencies could markedly vary in prolonged reaction times that are often required for synthesizing a large amount of enzymatic products. Most enzymatic activities are determined at their initial reaction stage to avoid various complications following enzymatic reactions, such as the change in substrate–product concentration and stability of enzymes. Such complications are likely to occur in the two coupled enzyme systems. Because the objective of the present study was to synthesize sulfated proteins, we further developed an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for identifying sulfated proteins and compared the efficacy of the two schemes for synthesizing sulfated proteins.

Figure 3.

Preparation of sulfated protein by two types of coupled enzyme systems. (A) PAPSS–TPST coupled PTS. Activated sulfate in PAPS was first obtained from inorganic sulfate and ATP catalyzed by PAPSS. The sulfated protein was prepared from PAPS and a protein substrate catalyzed by TPST. Radioactive sulfate can be used to produce radioactive-labeled sulfated proteins. (B) Phenol sulfotransferase–TPST coupled PTS. PAPS is regenerated from PAP and MUS catalyzed by phenol sulfotransferase to produce MU that yields fluorescence.

Identification of Recombinant Sulfated Proteins for High-Throughput Screening with ELISA

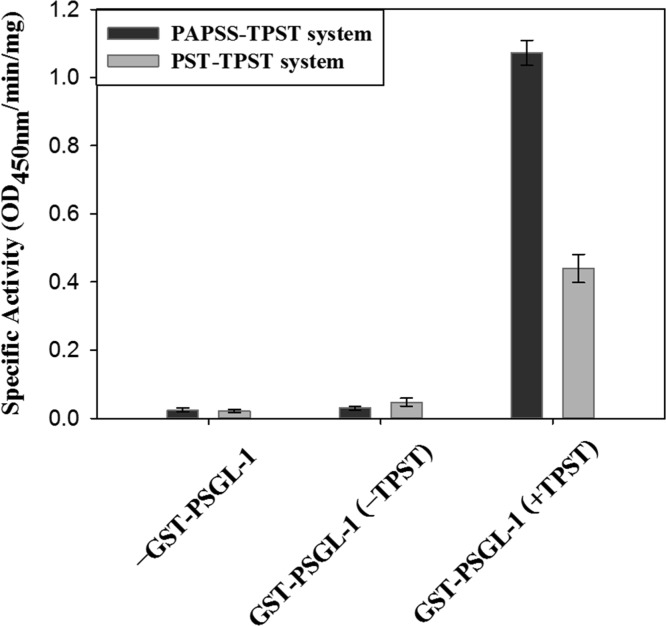

The aforementioned methods for detecting protein/peptide sulfation are typically designed for monitoring TPST activity in a short period during the initial linear production of sulfated proteins/peptides. A longer incubation time may be required to obtain near completion of the final sulfated products. In this study, ELISA was observed to efficiently detect and characterize the final sulfated proteins through a PTS scheme similar to the aforementioned scheme. The ELISA detection of the sulfated proteins can be performed conveniently in an ELISA plate and determined using anti-sulfotyrosine and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies by incubating with TMB. GST–PSGL-1 was first coated on an ELISA plate, which was subsequently blocked with milk. The PTS reaction and control experiment were subsequently conducted. All reagents required can be included in a one-pot reaction by either of the two schemes (Figure 3). Figure 4 shows that the sulfated proteins could be obtained only by using a complete reaction mixture in either the PAPSS–TPST or phenol sulfotransferase–TPST system. Negative results were obtained in the absence of both TPSTs, the protein substrate, indicating that the sulfated proteins were obtained through either the PAPSS–TPST or phenol sulfotransferase–TPST system and were recognized by the anti-sulfotyrosine antibody. Figure S3 shows the progress curve of PTS using various amounts of TPST. Data provided in Table S1 show the effect of substrate concentration on ELISA readings. The purpose of ELISA in our research is to quickly determine the reaction conditions for TPST and also used as a second method to confirm the protein sulfation. Figure 4 demonstrates that sulfated proteins could also be determined by ELISA. The amount of TPST used for catalyzing the reaction given in the figure legend and were determined according to our previous results shown in Figure S3 and Table S1. The PTS results determined by ELISA were consistent with those obtained using fluorescence17 and radioactive (Figure 6) methods. However, ELISA is more direct and convenient for determining PTS following long incubation times. The enzymatic activity can be more conveniently determined using the fluorescent assay (Figure 3B). The radioactive assay is cumbersome but favorable for obtaining direct evidence and confirming the transfer of the sulfate group from inorganic sulfate to PAPS and to the sulfated protein.

Figure 4.

In situ determination of two PTS schemes by ELISA. GST–PSGL-1 was coated on an ELISA plate, which was subsequently blocked with milk. The immobilized GST–PSGL-1 was then treated with the PAPSS–TPST or phenol sulfotransferase–TSPT system. Control experiments in the absence of each critical ingredient, GST–PSGL-1, and TPST were conducted to confirm that the PTS reaction on the target protein proceeded as expected. The sulfated proteins/peptides were recognized by anti-sulfotyrosine antibody, as described in the Materials and Methods section. The specific activity was determined according to the results of the HRP-produced signal per minute at OD450nm, and the DmTPST reaction time and amount were 60 min and 10 μg, respectively. Each data point was obtained from three independent measurements, and the error bar indicates standard deviation (SD).

Figure 6.

Detection of radioactive sulfated proteins/peptides. The sulfation of PSGL-1 was conducted using the scheme of the PAPSS–TPST system (Figure 1A). The 35S-labeled substrate yielded radioactive sulfate from PAPS synthesized in situ from 35S-containing inorganic sulfate. Lanes “–substrate (+TPST),” “PSGL-1 (−TPST),” “GST (−TPST),” and “GST–PSGL-1 (−TPST)” were the negative controls, indicating controlled reactions in the absence of one such component from the complete reaction mixture. Lanes “PSGL-1 (+TPST),” “GST (+TPST),” and “GST–PSGL-1 (+TPST)” contained a complete reaction mixture, as described in the Materials and Methods section for the sulfation of the substrate. The arrowheads indicate the spot of [35S] sulfated proteins/peptides. The bottom spots indicate unreacted [35S] sulfate and [35S] PAPS.

Comparison of the PTS Efficiency of Two Coupled Enzyme System Sulfation Schemes with Three Recombinant TPSTs in a Long Incubation Period

In a long incubation period, an enzyme-catalyzed reaction may differ from a reaction with a short reaction time because of various factors such as the stability of enzymes, accumulation of products that may become inhibitory at higher concentrations (Ki), and change in substrate concentration (Km) that can significantly affect Vmax. Prolonged incubation in such systems may yield excess amounts of PAP, which inhibits various sulfotransferases.42 The described PTS schemes were previously used13 for determining the initial rate as a characteristic of the kinetics of TPSTs. However, a long incubation time will likely be required to prepare sulfated proteins. We compared the efficiency of the two sulfation schemes in a long reaction time (Figure 5). We coated 1 μg of GST–PSGL-1 at a volume of 100 μL on the ELISA plate, which was subsequently blocked with milk. PTS was conducted for 0–150 min by using either the PAPSS–TPST or phenol sulfotransferase–TPST system. We compared the PTS efficiency of orthologous TPSTs (Figure 5) and observed that the PTS efficiency of DmTPST was higher than that of hTPSTs on the GST–PSGL-1 substrate. The sulfated GST–PSGL-1 was generated by DmTPST in a short time (approximately 5 min), but hTPSTs required more incubation time. Most species have two types of TPSTs to catalyze PTS, except for D. melanogaster, which has only one TPST. The two types of TPSTs might have a competitive or regulatory relationship, influencing the specificity and sensitivity of the substrate. Our results indicated that DmTPST maintained a high PTS efficiency for a substrate from a different species. In the same figure, the PTS efficiency levels of DmTPST in the two coupled enzyme systems were compared. GST–PSGL-1 has three tyrosine residues at the 46, 48, and 51 positions, and its PTS efficiency was different at these residues. We calculated the yield of sulfated GST–PSGL-1 at 5 min by plotting a calibration curve. The amount of sulfated GST–PSGL-1 produced coincided with that of GST–PSGL-1 used for immobilization. The signal of sulfated GST–PSGL-1 in the PAPSS–TPST-coupled enzyme system continued to increase; however, the signal of the sulfated GST–PSGL-1 in the phenol sulfotransferase–TPST system was constant after 5 min. Therefore, the PTS reaction occurs at more than one tyrosine residue in the PAPSS–TPST system but only at one tyrosine residue in the phenol sulfotransferase–TPST system. In the PTS reaction of GST–PSGL-1, the enzyme-catalyzed reaction may behave differently for these residues because of various factors such as PAPS or substrate concentration that markedly affects the PTS efficiency. The phenol sulfotransferase–TPST system does not exist in organisms, and a high concentration of PAPS may cause inhibition. However, the PAPSS–TPST system is present in organisms; PAPSS generates PAPS from inorganic sulfate, and PAPS continues to be consumed in the PTS reaction. Therefore, the PAPSS–TPST system has a lower inhibition response than does the phenol sulfotransferase–TPST system. The effects of the two coupled enzyme systems on different tyrosine residues will be further clarified in future studies. Finally, the sulfated product was observed to be generated by DmTPST and the PAPSS–TPST system.

Figure 5.

PTS under long incubation time. PTS was determined by ELISA, as described in Figure 4, which was conducted from 5 to 150 min by using either the PAPSS–TPST or phenol sulfotransferase–TPST system. Three recombinant enzymes, DmTPST (circle dot), hTPST1 (triangle dot), and hTPST2 (square dot), were examined. The reaction condition was the same as that described in Figure 4, except for the reaction time. PTS by the PAPSS–TPST system is shown as filled dots and that by the phenol sulfotransferase–TPST system is shown as open dots. The total activity was determined according to the HRP-produced signal per minute at OD450nm, and the TPST reaction amount was 10 μg. The mole of sulfated products was calculated by plotting the standard curve of sulfated GST–PSGL-1 in terms of the HRP-produced signal per minute at OD450nm. Each data point was obtained from three independent measurements, and the error bar indicates SD.

Yield and Purification of Sulfated GST–PSGL-1

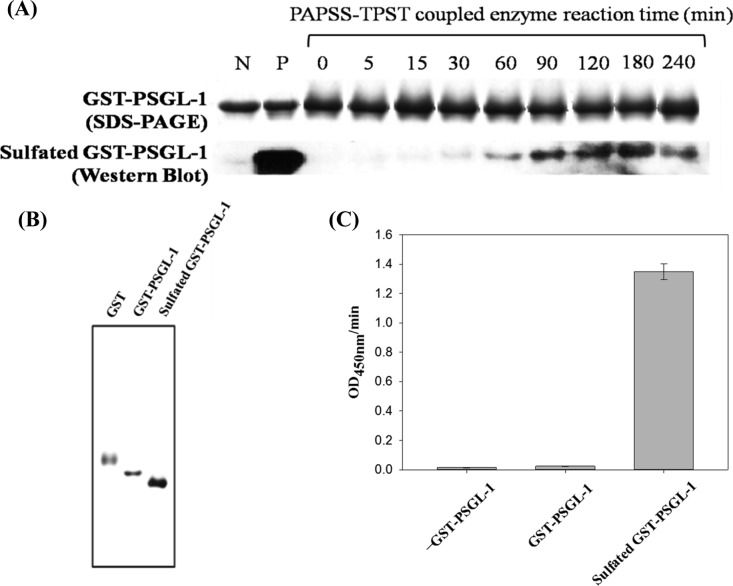

According to previous reports, the preparation of TPST for synthesizing sulfated proteins/peptides is expensive and difficult.43 The sulfated GST–PSGL-1 generated by DmTPST and the PAPSS–TPST system, as reported in the previous section, was further confirmed using a traditional radioactive method. We used GST–PSGL-1 and PSGL-1 as samples to prepare 35S-labeled sulfated proteins (Figure 6). The result revealed that the sulfated proteins could be obtained only from a PTS reaction mixture (lanes 3 and 7, Figure 6). In the absence of either the protein substrate (lane 1, Figure 6) or TPST (lanes 2, 4, and 6, Figure 6), the reaction yielded only negative results. The GST protein (lanes 4 and 5, Figure 6) was not a TPST substrate and therefore also showed negative results. These data strongly indicate that the 35S-labeled sulfated protein obtained by this reaction scheme was synthesized from 35S inorganic sulfate. Figure 7A shows that the yield of sulfated GST–PSGL-1 markedly increased after the PTS reaction. SDS–PAGE was the internal control for ensuring the protein quantity in each well. Western blotting revealed GST–PSGL-1 (lane N) and sulfated GST–PSGL-1 (lane P) as the negative and positive controls, respectively. The amount of sulfated GST–PSGL-1 was found decreasing after 180 min probably due to the high concentration of the product. The sulfated compounds are known to be labile, and sulfotransferase may catalyze the reverse reaction.44 It is proposed that, following the long incubation period, the accumulation of the sulfated GST–PSGL-1 became decreasing because of its low stability in aqueous solution. In addition, possible reverse reactions catalyzed by the enzyme system may also eliminate the sulfated compounds in long incubation period because of the change of the balance between substrate and product. However, the catalytic mechanism of the sulfotransferase-catalyzed nonphysiologic reverse reaction has not been studied to a significant extent. The positive control signal was stronger than the PAPSS–TPST reaction signal because the sulfated GST–PSGL-1 had been purified. The mixed reagent also affected the sulfated GST–PSGL-1 signal, as observed through western blotting. GST–PSGL-1 was allowed to react for 180 min to maximize the product yield. Next, the PTS reactant was diluted and reloaded into the GSTrap column; the purification procedure executed using the GSTrap sepharose column was repeated (the detailed procedure is described in the Materials and Methods section). The sulfated GST–PSGL-1 determined through native PAGE (pH 8.0) is shown in Figure 7B. The sulfated GST–PSGL-1 was further confirmed by ELISA (Figure 7C); the results revealed homogeneous sulfated GST–PSGL-1. Any PTS substrate could be catalyzed using the coupled enzyme system and then further purified.

Figure 7.

Identification and confirmation of sulfated product. (A) In vitro synthesis of sulfated GST–PSGL-1 with the PAPSS–TPST system by DmTPST. The amount of 5 μg GST–PSGL-1 was loaded in each well. SDS–PAGE of total GST–PSGL-1 stained with Coomassie blue is shown in the upper panel as an internal control. Western blotting for sulfated GST–PSGL-1 was probed by the anti-sulfotyrosine monoclonal antibody (lower panel). Lanes N and P indicate GST–PSGL-1 and sulfated GST–PSGL-1 as negative and positive controls, respectively. The sulfated GST–PSGL-1 (lane P) was obtained with the PAPSS–TPST system reacted for 240 min and was purified using the GSTrap sepharose column. The detailed procedure is reported in the Materials and Methods section. (B) Native PAGE of GST, GST–PSGL-1, and purified sulfated GST–PSGL-1 obtained with the PAPSS–TPST system after reaction for 240 min. Electrophoresis was performed under 8% PAGE in pH 8.0. (C) The sulfated products were confirmed by ELISA with blank, GST–PSGL-1, and purified sulfated GST–PSGL-1. Furthermore, 1 μg of sulfated GST–PSGL-1 was coated on an ELISA plate. The Y-axis represents HRP-produced signal per minute at OD 450nm. Each data point was obtained from three independent measurements, and the error bar indicates SD.

Conclusions

In this study, we purified large quantities of homogenous TPSTs from D. melanogaster and humans for sulfated GST–PSGL-1 synthesis. Coupled enzyme methods were used to generate sulfated GST–PSGL-1, which was subsequently detected using ELISA. Our results on the synthesis of sulfated proteins/peptides can contribute to studies on PTS-induced PPIs. Furthermore, the coupled enzyme methods can be observed through radiometry and fluorimetry. ELISA could facilitate the large-scale screening of the potential substrate and optimization of reaction conditions. Radiometry could accurately examine substrate candidates. Fluorimetry could enable the real-time and rapid detection of the product at the preliminary stage. These methods can be combined to generate and detect sulfated products and are not limited by the size or number of substrates. Our findings reveal that DmTPST is a highly efficient enzyme and that the PAPSS–TPST system is an optimal method for sulfated GST–PSGL-1 synthesis. The synthesis of sulfated proteins/peptides not only facilitates studying the basic biochemical mechanisms of TPST but also provides materials for PTS-induced PPIs. The study results can be used to explain the physiological function of PTS in the future.

Materials and Methods

Materials

A human TPST clone was obtained from GenDiscovery Biotechnology, Inc (Taiwan). D. melanogaster TPST (DmTPST) was kindly provided by Dr. Jyh-Lyh Juang of the Division of Molecular and Genomic Medicine, National Health Research Institutes, Miaoli, Taiwan. The compound was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) by using designed primers (Table 4). PfuTurbo DNA polymerase was purchased from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA, USA). T4 DNA ligase, BamHI, EcoRI, and XhoI restriction endonucleases were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA, USA). Furthermore, oligonucleotide primers were synthesized by Mission Biotech Co., Ltd. (Taiwan). Expression vectors and BL21(DE3) were obtained from Novagen (Madison, WI, USA). Tris[hydroxymethyl]aminomethane (Tris), 2-[N-morpholino]ethanesulfonic acid (MES), sodium chloride, ATP, β-mercaptoethanol, ethylenediaminetetra acetic acid (EDTA), MU, 4-MU sulfate (MUS), adenosine 3′,5′-diphosphate (PAP), 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS), 3,3′5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB), imidazole, and l-glutathione reduced and inorganic pyrophosphatase were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Potassium phosphate (dibasic), glycine, and SDS were obtained from J.T. Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ, USA). HisTrap and GSTrap sepharose columns were obtained from GE Healthcare (Uppsala, Sweden). Na2[35S]SO4 (1050–1600 Ci/mmol) of 99.0% radiochemical purity was purchased from PerkinElmer (Boston, MA, USA). Moreover, cellulose thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates were purchased from Merck (Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA). High-binding 96-well microplates were purchased from PerkinElmer. Anti-sulfotyrosine antibody (clone sulfo-1C-A2) and HRP-conjugated mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody (H- and L-chain specific) were purchased from Millipore and Abcam, respectively. The PSGL-1 peptide was synthesized by Genemed Synthesis, Inc. (San Antonio, USA), and its purity was verified through high-performance liquid chromatography. All other chemicals were of the highest purity commercially available.

Table 4. Primers for Gene Cloning of Orthologous TPSTsa.

| name | primersb | |

|---|---|---|

| DmTPST | forward | 5′-TGAAGAATTCGACGCCCCCAACGAGCTCTCCTC-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-TGCCCTCGAGCTCTCCCACAGCATTCGATTGGC-3′ | |

| hTPST1 | forward | 5′-ATGGATCCATGGAATGCCATCACCGGATA-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-ATCTCGAGCTCCACTTGCTCAGTCTGTG-3′ | |

| hTPST2 | forward | 5′-TGAAGGATCCCTAGAGTGCCGGGCGGTGCTGGC-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-GCCACTCGAGTCACGAGCTTCCTAAGTGGGAGG-3′ | |

| PSGL-1 | forward | 5′-GATCCGCCACCGAATATGAGTACCTAGATTATGATTTCCTGG -3′ |

| reverse | 5′-AATTCCAGGAAATCATAATCTAGGTACTCATATTCGGTGGCG -3′ | |

The primers used for clone constructs were designed for the catalytic domain in each TPST. The transmembrane domains predicted by the PSIPRED web server were truncated in this study.

The restriction sites of the sticky ends are underlined in each primer.

Sequence Alignment and Transmembrane Domain Analysis of TPSTs

The transmembrane region and orientation of TPSTs were predicted by PSIPRED (http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/psipred/psiform.html).45 Only the hydrophobicity scores exceeding 0 were considered significant to be the potential transmembrane region. The multiple sequence alignment was performed by the RE-MuSiC software tool (http://bioalgorithm.life.nctu.edu.tw/RE-MUSIC/),46 and the sequence identity scores were calculated by ClustalW2 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/).47 The alignment results were sorted and shaded by the BOXSHADE web server (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/BOX_form.html).

Clones of TPSTs and Their Substrates

The genes of human TPST1 (hTPST1) and TPST2 (hTPST2) as well as DmTPST were subcloned into the pET-43.1a vector. The predicted catalytic domain of TPSTs was amplified by PCR by using specific primers (Table 4). The oligonucleotides were designed to contain BamHI (hTPST1 and hTPST2) or EcoRI (DmTPST) restriction sites in the forward direction and the XhoI restriction site in the reverse direction. The cDNA fragments were inserted into the BamHI–XhoI or EcoRI–XhoI double restriction sites and subsequently confirmed through sequencing with an ABI Prism 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), following the standard protocol. The specific primers (Table 4) were designed to produce self-annealed cDNA encoding the N-terminal region of PSGL-1 (ATEYEYLDYDFL). The self-annealed oligonucleotides were subcloned into the BamHI–XhoI restriction site of pGEX-4T-1 for prokaryotic expression.

Expression and Purification of TPSTs and Their Substrates

A single colony of BL21(DE3) includes TPSTs; GST–PSGL-1 plasmids were inoculated in Luria–Bertani broth with ampicillin as the antibiotic at 37 °C. BL21(DE3) was allowed to grow to an OD600nm of 0.4–0.6 and then induced with 1 mM isopropyl-thio-β-d-galactoside (IPTG), followed by incubation for 24 h at 20 °C. The bacterial cultures were harvested through centrifugation and then homogenized with ice-cold HisTrap buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, and 10% glycerol) for TPST and ice-cold GSTrap buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 10% glycerol) for GST–PSGL-1. The crude homogenates were centrifuged at 30 000 g for 30 min, and the collected supernatants were individually fractionated using HisTrap and GSTrap sepharose columns. Furthermore, TPST was eluted with 50 mL HisTrap buffer B (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole, and 10% glycerol), and GST–PSGL-1 was eluted with 50 mL GSTrap buffer B (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, and 10 mM glutathione). The mixture of PTS-treated (PAPSS–TPST or phenol sulfotransferase–TPST coupled enzyme system) GST–PSGL-1 (i.e., sulfated GST–PSGL-1) was diluted 10-fold with ice-cold GSTrap buffer A. The diluted solution was reloaded into the GSTrap sepharose column, and the column loaded with glutathione was used to elute the sulfated GST–PSGL-1. The purity of the proteins was determined through SDS–PAGE, and the sulfated GST–PSGL-1 was further determined through 8% native PAGE in pH 8.0.

Preparation and Determination of Isotope 35S-Labeled Sulfated Protein Catalyzed Using the PAPSS–TPST System

PTS on GST–PSGL-1 (containing the PSGL-1 peptide at the N-terminal) and PSGL-1 peptide (ATEYEYLDYDFL) was catalyzed using the PAPSS–TPST system, and the PTS degree was monitored using 35S. The complete reaction mixture included a TPST substrate (either 120 μM GST–PSGL-1 or 120 μM PSGL-1 in this study), 4 mM Na2[35S]SO4, 1 mM ATP, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM MgCl2, 50 mM MES buffer (pH 6.5), 5 μg recombinant PAPS synthetase (PAPSS), 4 μg DmTPST, and 0.5 U pyrophosphatase in a final volume of 20 μL. The PTS degree was examined by spotting 1 μL aliquot of the reaction mixture on a cellulose TLC plate and developing the plate with n-butanol/pyridine/formic acid/water (5:4:1:3, by volume) as the solvent system. The dried plate was exposed to a Kodak BioMax MR film, which provided the optimal resolution for 35S autoradiography. The photographic plate was exposed to overlap through cellulose TLC. A liquid scintillation analyzer was used to detect the sulfation site in terms of the number of counts per minute.

Preparation and Determination of Sulfated Proteins Catalyzed Using the Phenol Sulfotransferase–TPST System

The complete reaction included 50 mM MES buffer (pH 6.5), 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 30 μM PAPS, 2 mM MUS, GST–PSGL-1, 17 mU phenol sulfotransferase, and DmTPST (10 μg) in 100 μL solution. TPST catalyzed the tyrosine sulfation of GST–PSGL-1 and yielded the same amount of PAP simultaneously. Phenol sulfotransferase immediately transferred the sulfuryl group of MUS to PAP by tyrosine sulfation and yielded PAPS and MU. The total amount of tyrosine sulfation can be calculated using the fluorescent signal of MU (excitation: 360 nm; emission peak: 450 nm).17

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay-Based Detection on Sulfated Proteins

The TPST substrate GST–PSGL-1 was coated on a 96-well microtiter plate [DNA-BIND (N-oxysuccinimide) modified surface] in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer overnight. The wells were subsequently blocked with 5% milk for 1 h at room temperature and washed three times with PBS plus Tween-20 [PBST:PBS (pH 7.4) containing 0.05% Tween-20]. PTS on the immobilized protein was catalyzed by the PAPSS–TPST or phenol sulfotransferase–TPST system, followed by PBST wash three times. A primary antibody (anti-sulfotyrosine IgG antibody, 1:1000 dilution) was then added and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Next, an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (anti-mouse IgG antibody, 1:6000 dilution) was added, and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at room temperature after washing three times with PBST. HRP reaction was developed with 100 μL TMB and stopped with 100 μL of 2 M H2SO4. Finally, the sulfated protein was determined at OD450nm.

Western Blotting

Total proteins were separated through 12% reduced SDS–PAGE and electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane by using a general western transfer protocol (Bio-Rad, USA). The membrane was blocked with 5% skim milk in tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 1 h at room temperature. The sulfated proteins were probed with anti-sulfotyrosine IgG antibody (1:1000 dilution) in TBS with Tween-20 (TBST) overnight at 4 °C. Furthermore, this membrane was washed five times with TBST for 5 min and then immersed in TBST with 5% milk and anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:10 000 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. The blot was visualized by chemiluminescence produced by HRP catalysis for 1–30 min. For examining the effects of time on PAPSS–TPST system catalysis, a standard assay with various reaction times (0, 5, 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, and 240 min) was conducted, followed by western blotting, to monitor the PTS content.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the Center For Intelligent Drug Systems and Smart Bio-devices (IDS2B) from The Featured Areas Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan and by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (105-2311-B-009-001) and the Wan Fang Hospital (102swf07).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.7b01533.

Tables and figures containing additional enzyme activity measurements and kinetics (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bettelheim F. R. Tyrosine-O-sulfate in a peptide from fibrinogen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1954, 76, 2838–2839. 10.1021/ja01639a073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore K. L. The biology and enzymology of protein tyrosine O-sulfation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 24243–24246. 10.1074/jbc.r300008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishiro E.; Sakakibara Y.; Liu M.-C.; Suiko M. Differential enzymatic characteristics and tissue-specific expression of human TPST-1 and TPST-2. J. Biochem. 2006, 140, 731–737. 10.1093/jb/mvj206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura M.; Naito S. Tissue-specific mRNA expression profiles of human carbohydrate sulfotransferase and tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 30, 821–825. 10.1248/bpb.30.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeuerle P. A.; Huttner W. B. Tyrosine sulfation of yolk proteins 1, 2, and 3 in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 6434–6439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibert C.; Sakmar T. P. Toward a framework for sulfoproteomics: Synthesis and characterization of sulfotyrosine-containing peptides. Biopolymers 2008, 90, 459–477. 10.1002/bip.20821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu W.; Rosenquist G. L.; Ansari A. A.; Gershwin M. E. Autoimmunity and tyrosine sulfation. Autoimmun. Rev. 2005, 4, 429–435. 10.1016/j.autrev.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monigatti F.; Hekking B.; Steen H. Protein sulfation analysis–A primer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1764, 1904–1913. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farzan M.; Babcock G. J.; Vasilieva N.; Wright P. L.; Kiprilov E.; Mirzabekov T.; Choe H. The role of post-translational modifications of the CXCR4 amino terminus in stromal-derived factor 1 alpha association and hiv-1 entry. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 227, 29484–29489. 10.1074/jbc.m203361200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehoe J. W.; Bertozzi C. R. Tyrosine sulfation: a modulator of extracellular protein-protein interactions. Chem. Biol. 2000, 7, R57–R61. 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B.-Y.; Chen P.-C.; Chen B.-H.; Wang C.-C.; Liu H.-F.; Chen Y.-Z.; Chen C.-S.; Yang Y.-S. High-Throughput Screening of Sulfated Proteins by Using a Genome-Wide Proteome Microarray and Protein Tyrosine Sulfation System. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 3278–3284. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b02853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeuerle P. A.; Huttner W. B. Tyrosine sulfation is a trans-Golgi-specific protein modification. J. Cell Biol. 1987, 105, 2655–2664. 10.1083/jcb.105.6.2655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.-S.; Wang C.-C.; Chen B.-H.; Hou Y.-H.; Hung K.-S.; Mao Y.-C. Tyrosine sulfation as a protein post-translational modification. Molecules 2015, 20, 2138–2164. 10.3390/molecules20022138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang Y.-B.; Moore K. L. Molecular cloning and expression of human and mouse tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase-2 and a tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase homologue in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 24770–24774. 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang Y.-b.; Lane W. S.; Moore K. L. Tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase: purification and molecular cloning of an enzyme that catalyzes tyrosine O-sulfation, a common posttranslational modification of eukaryotic proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998, 95, 2896–2901. 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beisswanger R.; Corbeil D.; Vannier C.; Thiele C.; Dohrmann U.; Kellner R.; Ashman K.; Niehrs C.; Huttner W. B. Existence of distinct tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase genes: molecular characterization of tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998, 95, 11134–11139. 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B.-H.; Wang C.-C.; Lu L.-Y.; Hung K.-S.; Yang Y.-S. Fluorescence assay for protein post-translational tyrosine sulfation. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2013, 405, 1425–1429. 10.1007/s00216-012-6540-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishiro E.; Liu M.-Y.; Sakakibara Y.; Suiko M.; Liu M.-C. Zebrafish tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase: molecular cloning, expression, and functional characterization. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2004, 82, 295–303. 10.1139/o03-084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T. H.; Kim D. H.; Nam H. W.; Park S. Y.; Shim J.; Cho J. W. Tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase regulates collagen secretion in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Cells 2010, 29, 413–418. 10.1007/s10059-010-0049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori R.; Amano Y.; Ogawa-Ohnishi M.; Matsubayashi Y. Identification of tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009, 106, 15067–15072. 10.1073/pnas.0902801106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimbro R.; Peterson F. C.; Liu Q.; Guzzo C.; Zhang P.; Miao H.; Van Ryk D.; Ambroggio X.; Hurt D. E.; De Gioia L.; Volkman B. F.; Dolan M. A.; Lusso P. Tyrosine-sulfated V2 peptides inhibit HIV-1 infection via coreceptor mimicry. EBioMedicine. 2016, 10, 45–54. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone S. R.; Hofsteenge J. Kinetics of the inhibition of thrombin by hirudin. Biochemistry 1986, 25, 4622–4628. 10.1021/bi00364a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.; Dong J.; Li S.; Liu Y.; Wang Y.; Yoon L.; Wu P.; Sharpless K. B.; Kelly J. W. Synthesis of Sulfotyrosine-Containing Peptides by Incorporating Fluorosulfated Tyrosine Using an Fmoc-Based Solid-Phase Strategy. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2016, 55, 1835–1838. 10.1002/anie.201509016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. C.; Cellitti S. E.; Geierstanger B. H.; Schultz P. G. Efficient expression of tyrosine-sulfated proteins in E. coli using an expanded genetic code. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 1784–1789. 10.1038/nprot.2009.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L.-Y.; Chen B.-H.; Wu J. Y.-S.; Wang C.-C.; Chen D.-H.; Yang Y.-S. Implantation of post-translational tyrosylprotein sulfation into a prokaryotic expression system. ChemBioChem 2011, 12, 377–379. 10.1002/cbic.201000540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaprasad P.; Kasinathan C. Isolation of tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase from rat liver. Gen. Pharmacol. 1998, 30, 555–559. 10.1016/s0306-3623(97)00304-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T.-A.; Yasuda S.; Williams F. E.; Liu M.-Y.; Suiko M.; Sakakibara Y.; Yang Y.-S.; Liu M.-C. A target-specific approach for the identification of tyrosine-sulfated hemostatic proteins. Anal. Biochem. 2009, 390, 88–90. 10.1016/j.ab.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffhines A. J.; Damoc E.; Bridges K. G.; Leary J. A.; Moore K. L. Detection and purification of tyrosine-sulfated proteins using a novel anti-sulfotyrosine monoclonal antibody. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 37877–37887. 10.1074/jbc.m609398200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassen K. S.; Bradbury A. R. M.; Rehfeld J. F.; Heegaard N. H. H. Microscale characterization of the binding specificity and affinity of a monoclonal antisulfotyrosyl IgG antibody. Electrophoresis 2008, 29, 2557–2564. 10.1002/elps.200700908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura Y.; Wakita T.; Shimizu H. Tyrosine sulfation of the amino terminus of PSGL-1 is critical for enterovirus 71 infection. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1001174 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura Y.; Shimojima M.; Tano Y.; Miyamura T.; Wakita T.; Shimizu H. Human P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 is a functional receptor for enterovirus 71. Nat. Med. 2009, 15, 794–797. 10.1038/nm.1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibert C.; Cadene M.; Sanfiz A.; Chait B. T.; Sakmar T. P. Tyrosine sulfation of CCR5 N-terminal peptide by tyrosylprotein sulfotransferases 1 and 2 follows a discrete pattern and temporal sequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002, 99, 11031–11036. 10.1073/pnas.172380899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- William S.; Ramaprasad P.; Kasinathan C. Purification of tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase from rat submandibular salivary glands. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1997, 338, 90–96. 10.1006/abbi.1996.9800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasinathan C.; Ramaprasad P.; Sundaram P. Identification and characterization of tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase from human saliva. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2005, 1, 141–145. 10.7150/ijbs.1.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teramoto T.; Fujikawa Y.; Kawaguchi Y.; Kurogi K.; Soejima M.; Adachi R.; Nakanishi Y.; Mishiro-Sato E.; Liu M.-C.; Sakakibara Y.; Suiko M.; Kimura M.; Kakuta Y. Crystal structure of human tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase-2 reveals the mechanism of protein tyrosine sulfation reaction. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1572. 10.1038/ncomms2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibert C.; Sanfiz A.; Sakmar T. P.; Veldkamp C. T. Preparation and Analysis of N-Terminal Chemokine Receptor Sulfopeptides Using Tyrosylprotein Sulfotransferase Enzymes. Methods Enzymol. 2016, 570, 357–388. 10.1016/bs.mie.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W.; Duckworth B. P.; Geraghty R. J. Fluorescent peptide sensors for tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase activity. Anal. Biochem. 2014, 461, 1–6. 10.1016/j.ab.2014.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin E.-S.; Yang Y.-S. Colorimetric determination of the purity of 3′-phospho adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate and natural abundance of 3′-phospho adenosine 5′-phosphate at picomole quantities. Anal. Biochem. 1998, 264, 111–117. 10.1006/abio.1998.2800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooqui A. A. 3′-phophoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate metabolism in mammalian tissues. Int. J. Biochem. 1980, 12, 529–536. 10.1016/0020-711x(80)90003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaassen C. D.; Boles J. W. Sulfation and sulfotransferases 5: the importance of 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) in the regulation of sulfation. FASEB J. 1997, 11, 404–418. 10.1096/fasebj.11.6.9194521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.-T.; Liu M.-C.; Yang Y.-S. Fluorometric assay for alcohol sulfotransferase. Anal. Biochem. 2005, 339, 54–60. 10.1016/j.ab.2004.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman E.; Best M. D.; Hanson S. R.; Wong C.-H. Sulfotransferases: structure, mechanism, biological activity, inhibition, and synthetic utility. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2004, 43, 3526–3548. 10.1002/anie.200300631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson L. S.; Zhu J. Z.; Widlanski T. S.; Stone M. J. Regulation of chemokine recognition by site-specific tyrosine sulfation of receptor peptides. Chem. Biol. 2009, 16, 153–161. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyapochkin E.; Kumar V. P.; Cook P. F.; Chen G. Reaction product affinity regulates activation of human sulfotransferase 1A1 PAP sulfation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2011, 506, 137–141. 10.1016/j.abb.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuffin L. J.; Bryson K.; Jones D. T. The PSIPRED protein structure prediction server. Bioinformatics 2000, 16, 404–405. 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.4.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung Y.-S.; Lee W.-H.; Tang C. Y.; Lu C. L. RE-MuSiC: a tool for multiple sequence alignment with regular expression constraints. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, W639–W644. 10.1093/nar/gkm275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenna R.; Sugawara H.; Koike T.; Lopez R.; Gibson T. J.; Higgins D. G.; Thompson J. D. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 3497–3500. 10.1093/nar/gkg500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.