Abstract

Research indicates that Latinos underutilize substance abuse interventions; cultural variables may contribute to difficulties accessing and completing treatment for this group. As a result, there is a need to understand the role of cultural constructs in treatment outcomes. The purpose of this study was to investigate how levels of Collectivism (COL) and Individualism (IND) relate to length of stay and relapse outcomes in self-run recovery homes. We compared Latinos in several Culturally Modified recovery Oxford Houses to Latinos in traditional recovery Oxford Houses. By examining COL and IND in the OH model, we explored whether aspects of COL and IND led to longer lensgths of stay and better substance use outcomes in the OH model. We hypothesized that higher levels of COL would predict longer stays in an Oxford House and less relapse. COL did not have a main effect on length of stay. However, COL had a significant interaction effect with house type such that COL was positively correlated with length of stay in traditional houses and negatively correlated with length of stay in the Culturally Modified condition; that is those with higher collectivism tended to stay longer in traditional houses. When we investigated COL, length of stay, and substance use, COL was negatively correlated with relapse in the Culturally Modified houses and positively correlated with relapse in the traditional houses. In other words, those with higher COL spent less time and had less relapse in the Culturally Modified compared to the traditional Oxford Houses. The implications of these findings are discussed.

Keywords: recovery homes, Oxford House, culturally modified houses

In 2010, 50.5 million or 16 percent of the U.S population were of Latino origin, and by 2030 they are expected to represent 21.6 percent of the U.S population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014). The Latino community represents a diverse group of individuals from various ethnicities and cultures who trace their origins to several nations from Latin America (Alvarez, Jason, Olson, Ferrari, & Davis, 2007; Comas-Diaz, 2001). Behavioral research on Latinos tends to compare Latinos with other cultural and ethnic groups to determine whether there are any differences based on cultural and ethnic background. Some have suggested that Latinos subscribe to “Collectivism (COL).” Collectivism assumes that the group influences and molds the individual, whereas individualism (IND) emphasizes individual self-determination and self-actualization.

A number of studies have examined these cultural constructs in the U.S. In a large study of students from nine colleges and universities in the US, Schwartz, et al. (2010) found that communalism, familism, and filial piety clustered onto a single factor, which was closely and positively related to collectivism but only weakly and positively related to individualism. In a second study by Schwartz et al. found that his factor was positively associated with both positive psychosocial functioning and psychological distress. Oyserman and colleagues’ (2002) found different cultural groups did not differ significantly in IND, but European Americans were significantly lower in COL than Asian American and Latino/Hispanic Americans. However, contextually, individualism/collectivism may differ across cultural groups. As our study focused on Latino populations, rather than focusing on differences in individualism/collectivism between ethnic groups, it is important to examine the literature regarding acculturation within the Latino group.

As previously noted Schwartz and colleagues (2010) created a model of acculturation that provoked the study of collectivism and individualism. Their model is now the standard with which Researchers work when studying acculturation. Schwartz et al. (2014) recently examined individualism/collectivism in the US among recent Hispanic immigrants. They predicted increased health risks when immigrants conformed to American culture. Moreover, individualist values predicted greater numbers of oral sex partners and unprotected sex for boys. However, for boys, adopting American values predicted less heavy drinking, fewer oral and vaginal/anal sex partners, and less unprotected vaginal/anal sex. Given the complexity of these findings, Schwartz and colleagues suggested that future research should attempt to better understand these influences, thereby allowing researchers to design more effective ways to culturally inform our interventions.

Research studies on substance abuse in Latino populations is sparse, and predominately focuses on adolescents (Alvarez et al., 2007). While substance use and abuse rates for Latinos are not different from those of other ethnic groups, Latinos tend to underutilize treatment (Guerrero, Marsh, Khachikian, Amaro, & Vega, 2013). The literature indicates that cultural differences between patients and clinicians may lead to premature termination of care. Lower levels of treatment involvement ultimately leads to poorer outcomes (Alegria et al., 2006; Guerrero et al., 2013).

In addition to Latinos underutilizing treatment, many who do finish treatment are not provided adequate aftercare services (Jason et al., 2013). Examining and understanding outcomes for Latinos seeking aftercare services is important because substance abuse is a chronic condition that requires ongoing intervention (McKay & Weiss, 2001). To address the need for aftercare services, a number of self-help groups have been developed, some of which involve residential care. One example of a community-based aftercare setting is Oxford House (OH), which was founded by recovering individuals whose goal was to provide sober housing and support to peers seeking long-term abstinence. Since its inception, OH has grown into an international network of over 1,900 homes, serving over 10,000 men and women in the U.S. Since the early 1990’s, a team of researchers at DePaul University has studied OH (Jason, Olson & Foley, 2008). The OH model provides self-help, sober living environment that follows democratic values. The houses are financially self-supported and each member is required to pay their equal share of rent and living expenses. OH has not prescribed length of stay and there are no professionals involved in the house. All residents must follow three rules: pay rent and contribute to the maintenance of the house, abstain from using alcohol and other drugs, and avoid disruptive behavior. Violation of the rules results in evection from the house (Oxford House, Inc., 2008).

A NIAAA-supported study successfully recruited 150 individuals who completed treatment at alcohol and drug abuse facilities in the Chicago metropolitan area. Half of the participants were randomly assigned to live in an OH, while the other half received community-based aftercare services (Usual Care). We were able to track over 89% of the OH and 86% of the Usual Care participants throughout the two year follow-up. Results from this randomized study indicated significantly lower relapse for OH (31.6%) than Usual Care participants (64.8%) at 24 months post-discharge from residential treatment (Jason, Olson, Ferrari, & LoSasso, 2006). Further, OH residents were more likely to be employed (76.1% vs. 48.6%) and less likely to report engagement in illegal activities (0.9% vs. 1.8%). In addition, longer lengths of stay were associated with better outcomes. However, in national samples of Oxford Houses, Latinos represented only 3% of the house residents (Jason, Davis, Ferrari, & Anderson, 2007). We concluded that Latinos are underrepresented within the Oxford House population, and almost all Latinos in the study had high levels of assimilation. Most were U.S.-born. Only two residents were familiar with Oxford House prior to entering residential treatment, and the participants decided to move to an Oxford House based on information they received from counselors and peers. Regarding concerns prior to entering Oxford House, many felt that House policies would be too restrictive and similar to those they had experienced at half-way houses. Half of them also had concerns about being the only Latino house member. In spite of these initial concerns, participants reported overwhelmingly positive experiences in Oxford Houses. Most participants said that they “blended into the house” within the first few weeks. But the participants also informed us that many Latinos do not have access Oxford House because they are either unfamiliar with the program or there are no Spanish-speaking Oxford Houses. In order to increase Latino representation in Oxford Houses, they said more information should be provided to substance abuse treatment programs regarding this innovative mutual-help program, and that there should be more opportunities for Spanish-speaking individuals to join the Oxford House program.

In an effort to study this issue in more detail, we developed in Illinois culturally modified Oxford houses. Outcomes from these residents were compared to outcomes for Latinos within traditional OHs (Contreras et al, 2012). In that study, Jason et al. (2013) found significant increases in employment income, with the size of the change significantly greater in the Culturally Modified Oxford Houses. The study also found significant decreases in alcohol use over time, with larger decreases over time in the traditional recovery homes. In addition, lower levels of linguistic acculturation were related to higher alcohol use at baseline and greater decreases in alcohol use over time. That study had not found differences between house types of this acculturation measure. However, this effect might have been due to regression toward the mean given that there were differential baseline levels of alcohol use.

In the current study, we investigated how Latinos differ in levels of COL and IND. We hypothesized that higher levels of COL would predict longer stays in an Oxford House and less relapse. Additionally, by examining COL and IND in the Culturally Modified and traditional OH models, we explored whether aspects of COL and IND led to longer lengths of stay and better substance use outcomes in these two models. To summarize, this study sought to understand the role of cultural constructs in treatment outcome, and it investigated whether COL and IND predicted length of stay and relapse in OH and how house type (e.g. traditional or Culturally Modified Oxford House) might moderate this relationship.

Method

Participants

The current study used archival data from an NIH-funded study of Oxford House (Jason et al., 2013). Participants for the original study were recruited from multiple community-based organizations and health facilities from a large metropolitan area in the Midwest. The inclusion criteria set by the investigators from the original study were: 1) participants had to be from Latino backgrounds, 2) participants had successfully completed a substance abuse treatment program, and 3) participants abstained from alcohol and illicit substances at the time they were recruited.

In the culturally-modified OHs, all residents were Latino, and participants had the option of speaking English, Spanish or a mixture of both languages. In these houses, residents could address experiences that may be more specific to Latino culture such as the involvement of family in a person’s recovery activities. In addition, residents of culturally-modified OHs could more easily use culturally-congruent communication styles, characterized by “personalismo,”“simpatia,”, and “respeto.”

At baseline there were 135 Latino participants, 117 males (86.7%) and 18 females (13.3%) who were either assigned to Culturally Modified (N = 70) or to traditional (N= 50) OHs. Other participants (N = 15) declined to go to an OH after completing the assessment. The mean age of the participants who were in the Culturally Modified OH was 35 (SD 10.0) and for the traditional OHs was 37 (SD 10.3). Nearly half of the participants were born in Puerto Rico, Mexico and other Latin American countries (49%), with a mean length of stay of 19 years in the U.S main land. Participants in the traditional OHs had a mean of 11.3 years of education (SD 2.4), and the mean for the Culturally Modified OH was 11.5 years of education (SD 1.9). Demographics/descriptive statistics table with data for both groups is provided elsewhere (Jason et al., 2013). In a prior study (Jason et al., 2013), we examined whether there were significant baseline sociodemographic differences between the groups, but no significant differences among demographic variables were found for those in the traditional versus culturally modified OHs. No significant differences were found in the number of days spent in the traditional OH versus the culturally modified OH from baseline to follow-up.

Seventy percent (N = 85) of the 135 participants completed the six-month follow-up interview and were included in the current analysis. However, one participant who completed the six-month follow-up was not included in the current study because he never lived in an Oxford House. When comparing the 36 who dropped out and did complete the follow-up interview with the 84 who remained in the study, there were no significant differences in regards to age, education years, and income. For the 84 participants who remained in the study, 53.6 % (n = 45) individuals were in the Culturally Modified OHs and 46.6% (n = 39) were in the traditional OHs (Jason et al., 2013).

Instruments

Demographics.

A 24-item demographic questionnaire was used to collect participants’ age, gender, place of birth, country of origin, years in the U.S. and treatment setting. This instrument was translated and back-translated by the research team that included several bilingual/bicultural members. Participants were also asked to report their place of birth which was dummy coded as non-U.S. born =0 or non-U.S. born=1. Puerto Ricans who were born in the island were placed in the non-U.S. born group.

Individualism and Collectivism Scale

(Oyserman et al., 2002). This scale is a 36-item, 5-point Likert-type self-report measure developed to assess Individualism (IND) and Collectivism (COL). It was administered at the 6 month follow-up. The range of possible scores is as follow: 1=strongly disagree, 2=somewhat disagree, 3=neither agree nor disagree, 4=somewhat agree, and 5=strongly agree. Three subscales, Common Fate, Familism, and Interrelatedness were used to create the construct of COL and the three subscales of Valuing Uniqueness, Valuing Freedom/Happiness, and Valuing Personal Achievement were used to create the construct of IND. The IND scale contains a total of 17 items. An average score of the 17 items was used with higher scores indicating higher levels of individualism. The COL scale contains a total of 19 items. An average score of the 19 items was used with higher scores indicating higher levels of collectivism. Oyserman et al. developed the scale using items based on each of the facets of individualism and collectivism from items used in other measures (e.g., Triandis et al., 1988; Triandis et al., 1990). Reliabilities appear adequate in samples of U.S. Canadian and Japanese college students. Cronbach alphas for the current sample (N = 84) are the following: IND = .786; COL = .873.

Form-90 Timeline Follow-back

(Miller, 1996). This instrument provides a linear measure of alcohol and substance consumption within a 180-day time span.. The Form-90 was administered at baseline and at the 6 month follow up from the time the participant left the Oxford House. The Form-90 was translated into Spanish using translation and back-translation procedures along with regular discussions among team members by a bilingual team that included a professional translator, a psychologist, and a psychology graduate student (W. Miller, personal communication, October, 2005). The Form-90 had been used in several studies with Latino samples to produce valid data (Arroyo, Miller et al., 2003; Arroyo, Westerberg et al., 1998). For this study, our dependent variable was “any use” as defined by the Timeline Follow-back as positive alcohol or drug use days.

Procedures

Data was collected as part of a larger study comparing outcomes in Traditional and Culturally Modified OHs (Jason et al., 2013). The DePaul University IRB approved the original study and the Adler School of Professional Psychology IRB also approved the current investigation. Recruitment of participants began in fall 2009 and the study was completed in the summer of 2013. A bilingual and bicultural research team was formed to facilitate outreach, recruitment and assessment of Latino and Latina participants. Using online search engines and statewide lists of treatment and mental health providers, research assistants generated a list of substance treatment programs, hospitals, community agencies and churches that provide services to Latinos. The outreach strategy consisted of contacting these sites via phone and email to introduce the Culturally Modified OH project for Latinos. A team of OH alumni, two of them Latinos, worked to establish ties with staff and potential participants at various treatment centers. Recruiters provided information on recovery home options, described the nature of the study to potential participants, and facilitated the interview process. Recruiters approached Latinos interested in continuing their recovery in an OH prior to their discharge. The assessment interview was administered in Spanish or in English by bilingual/bicultural research assistants, graduates students, and the project director. The interview took place at the treatment facility, from which they were recruited, in an OH, or in the Center for Community Research at DePaul University. All interviews were conducted in rooms where confidentiality and privacy could be established.

Participants were given an explanation about the nature, purpose and goals of the study. Participants gave informed consent by signing the consent form provided by the original researchers. Consent forms were in Spanish and English. Interviewers also explained that participation in the study was entirely voluntary and that did not exclude them from being assigned to an OH. Assessments and consent forms were collected after participants were accepted either into a Culturally Modified OH or a traditional OH assignment was based on various factors, including participants’ dominant language (English vs. Spanish), house preference (i.e., location, Culturally Modified OH vs. traditional OH) and openings available. After completing the interview, participants received $30 dollars as a compensation for their participation. Six months later, participants were asked to complete a second interview, and participants received $30 dollars as a compensation for their participation.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The mean score for the Individualism scale was 3.38 (SD = 0.38) and the mean score for the Collectivism scale was 2.94 (SD = 0.50). The mean length of stay in days was 115 for the traditional OHs and 100 for the Culturally Modified OHs.

Main Hypotheses

It was first hypothesized that higher levels of collectivism would predict longer stay in an OH. However, total length of stay in an OH was not significantly correlated to COL total scores. In addition, total length of stay in an OH was not significantly correlated to total IND scores.

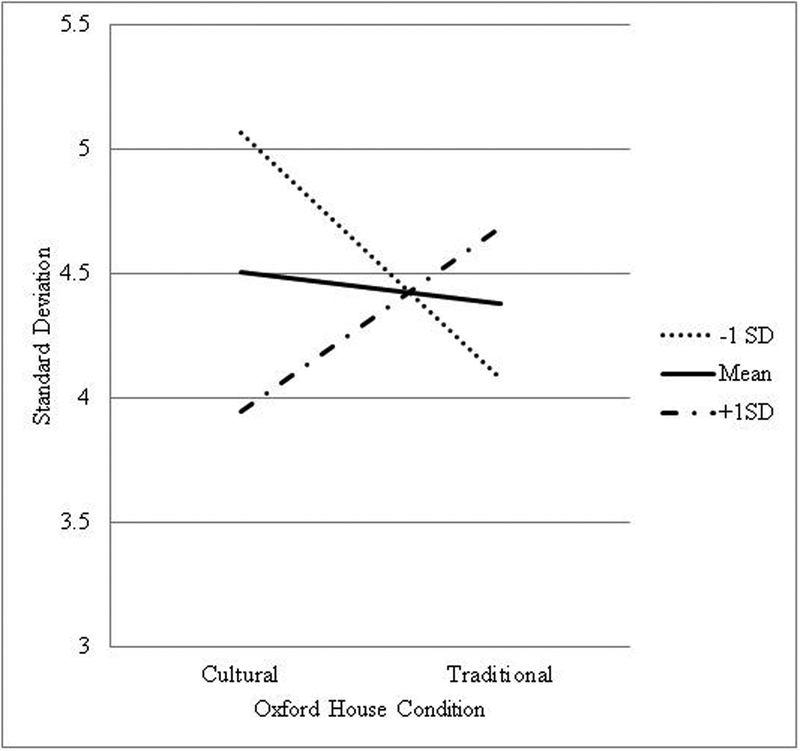

Moderation

We next explored the relationship between collectivism and individualism and length of stay in Oxford House would be moderated by house type (e.g. Culturally Modified OH or traditional OH). The test for an interaction effect between COL and house type predicting length of stay was performed using a generalized linear model. The interaction was significant [Wald χ2 = 9.75, p < .01—note the Wald χ2 = t2 in a regular regression or (−1.718/.5501)2] with a negative relationship indicating that higher scores of collectivism were associated with shorter length of stays in the culturally modified Oxford House (see Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Length of Stay as a function of Collectivism and Condition

We next investigated collectivism, individualism, length of stay, and substance use. The dependent variable was “any use” as defined by the Timeline Follow-back as positive alcohol or drug use days. Modeling was done with a Generalized Linear Model using a logistic link. With the addition of substance use outcomes, 36.9% (31/84) had one or more alcohol or drug use days between baseline and the 6 month follow-up. First, when simply comparing the results by House Type (Culturally Modified OH vs. traditional OH) versus the null, a significant difference was detected (B = .931, Wald χ2 = 3.875, p < .05, OR = 2.538) where the likelihood (as measured by the odds ratio) is 2.5 times greater to relapse as compared to the traditional house (note this isn’t the ratio of the probabilities which would be 1.82 [(21/45)/(10/39)]). While House Type was significant when looking at changes to indicators of model fit the explanatory power is small. The House Type model AIC (110.59) is only slightly improved over the Null AIC (112.62) and the reduction in the Deviance/Degree of Freedom (1.300 vs. 1.333) is similarly small.

While we found that IND was not significant as a main effect or moderator, the analysis of COL revealed that length of stay and House Type were significant main effects and that COL was significant as moderator with House Type (see Table 1). The magnitude of the odds ratios should also be noted with all variables contributing relatively large effect sizes.

Table 1:

Generalized Linear Model Results with Collectivism Moderated by House Type

| Parameter | B | Std. Error | Wald Chi-Square | df | Sig. | Exp(B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −1.801 | .5444 | 10.948 | 1 | .001 | .165 |

| [House =Culturally Mod] | 1.664 | .6392 | 6.772 | 1 | .009 | 5.278 |

| [House =Traditional] | 0 | . | . | . | . | 1 |

| ZLNDAYS | −1.571 | .3797 | 17.105 | 1 | .000 | .208 |

| ZCOLLECT | 1.093 | .4419 | 6.123 | 1 | .013 | 2.985 |

| [House=Culturally Mod] * ZCOLLECT | −2.051 | .6917 | 8.796 | 1 | .003 | .129 |

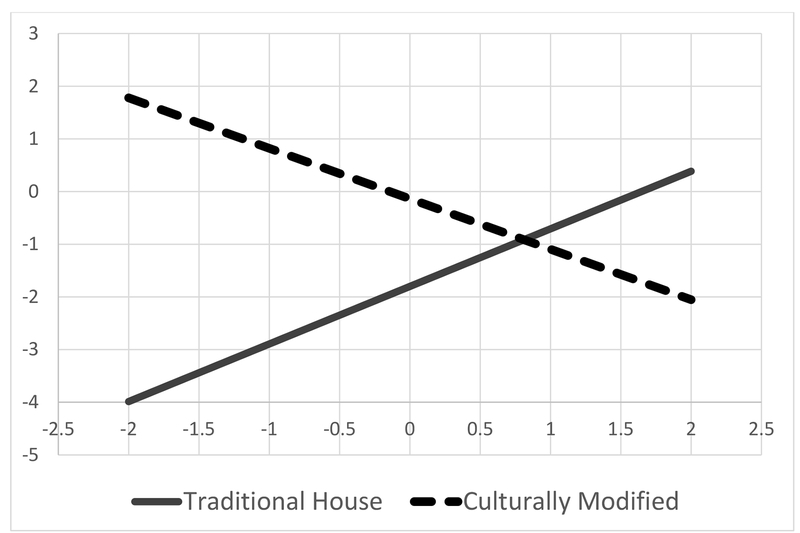

The resulting predictive equations reduce to:

For traditional OH: ln(odds)= −1.801–1.571(ZlnDays)+1.093(ZCollect)

For Culturally Modified OH: ln(odds)= −.137–1.571(ZlnDays)-.958(ZCollect)

The model when including Length of Stay and COL portrays a more powerful and explanatory set of predictive relations with relapse. This analysis reduces to main effects from House Type, length of stay, with a significant interaction between COL and House Type such that COL is negatively correlated with relapse in the Culturally Modified OH and positively correlated with relapse in the traditional OH (See Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Predicted Ln(Odds) by ZCollectivism (ZLOS – 0 or Mean)

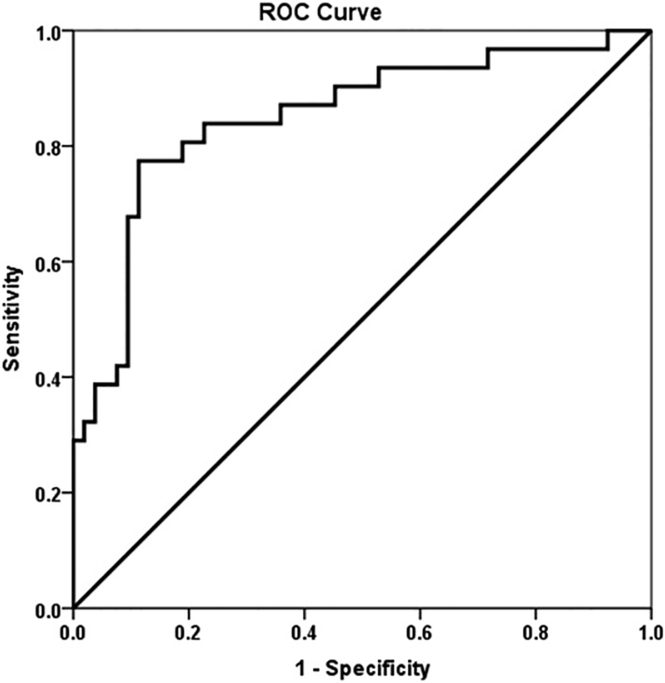

With respect to fit, this model has significant predictive power as illustrated by the ROC analysis (See Figure 3) where the area under the curve was .85 (standard error = .046; p < .01), and also by the fit statistics. When compared to the House Type only model, the AIC has decreased from 110.59 to 88.54, and the Deviance/Degree of Freedom from 1.300 to .994.

Figure 3.

ROC curve

Discussion

We initially found that those with higher collectivism tended to stay longer in traditional houses. This was a somewhat surprising and paradoxical finding. That is, COLwas not predictive of overall length of stay.

This paradoxical result was clarified with the addition of substance use outcomes. Those with higher COL spent less time and had less relapse in the Culturally Modified Oxford Houses compared to the traditional Oxford Houses. This is important given COL’s dispositional orientation, and its interaction with settings may have powerful treatment effects for people in recovery.

Previous research on client retention has suggested that developing culturally sensitive treatment programs can increase participation, retention rates, and success in treatment (Alegría et al., 2006; Alvarez et al., 2007; Guerrero, Marsh, et al., 2013 Guerrero, Campos, et al., 2012). This study found that Latinos with higher COL scores left the culturally modified OH sooner than individuals with lower COL scores, but had less relapse. Past research has indicated that briefer stays are associated with more relapse (Jason et al., 2006). It is possible that in the current study these individuals received what they needed from the Culturally Modified groups quicker, thus the COL dispositional entity might be of importance for understanding what individuals need from these types of community based recovery settings.

The literature on COL and IND indicate that these two constructs or mindsets are cross-culturally relevant (Triandis, 1993; Oyserman et al., 2002; Oyserman 2011). The results of this study support this finding. Even though the COL and IND scale was not given at baseline to compare if these two cultural syndromes changed after living in an OH for more than six months, the current findings demonstrate that these are not mutually exclusive entities, and in fact, they are positively correlated with each other.

Individuals who adopt a COL trait tend to link their sense of self with others, have a strong sense of duty, and have a strong sense of social obligation. Potential negative outcomes for collectivist individuals include: difficulties creating new relationships with others who are not part of their in-group, difficulty trusting others, being assertive, standing up to authority, and feelings prejudice (Kim, 1994; Hui & Triandis, 1986; Oyserman et al., 2002; Oyserman & Sorensen, 2009; Singelis, 1994; Singelis et al., 1995). It is possible that participants who had higher COL scores in the Culturally Modified OH left the house sooner might be that after being able to maintain progress in their recovery they felt they were ready to return to their in-group (e.g. family, extended family, friends, and nation). Data regarding the social supports networks would be needed to validate this assumption. The fact that they had better relapse outcomes also supports this explanation. Furthermore, Oxford Houses are independently run using democratic principles. The house members are responsible for maintaining the house by paying rent, completing chores, and attending weekly business meetings (Oxford House, Inc., 2008). The OH model tries to foster a sense of community among the members, and simultaneously promotes its members to become independent. This model may be more congruent with an IND framework, but might also be very effective for maintaining abstinence for those with a COL orientation. The relationships among the members are casual and are maintained for a purpose (e.g. to maintain the house, and stay sober). However, creating a sense of community entails collectivistic traits since the house requires the members to depend on each other to maintain the house and become part of the Oxford House community.

Regardless of why collectivism is influential in predicting substance use outcomes, the findings illustrate a phenomenon of significant and powerful differential effects that may be underestimated when averaged across groups. That is, the simultaneous existence of positive and negative correlations by group become a null effect when averaged. The interaction of disposition and setting does appear to make a difference in relapse likelihoods. Several limitations associated with this data set must be acknowledged, including lack of random assignment to the groups. In addition, the sample was limited to individuals who self-identified primarily as Mexican and Puerto Rican and were either born in the U.S. mainland or lived here an average of 19 years. Nativity could be a confounding variable, as is length of time in the country, and should be controlled for in future studies. Because the other domains for acculturation were not controlled for, it is not possible to know whether results relate specifically to collectivism, or other unmeasured/uncontrolled for variables.

Gender and the sample size are other limitations as most of the participants were male and the sample was relatively small. Another limitation of this study is that the data on individualism and collectivism were not collected during the baseline. Instead, participants were given the scale after they were living in the Oxford House for a minimum of six months. Hence, we do not have data to understand if and how living in a traditional OH or a Culturally Modified OH might have influenced the levels of COL and IND. In addition, for the Individualism/Collectivism scale, Likert scales are culturally biased in Latino populations. These issues differ by acculturation, country of origin, etc., and, this alone may confound the data. In addition, the Individualism/Collectivism scale should have been validated with Latino populations.

Despite the study’s limitations, its findings have significant implications for treatments programs that are considering cultural modification. The current study represents a starting point in the exploration of how the constructs of COL and IND manifest themselves in treatment programs and if they positively or negatively influence in retention and relapse. This is the first study that has examined the construct of COL and IND in a substance abuse aftercare program.

Based on the results of this study, current literature, and limitations, recommendations for future research are the following. Researches who would like to consider doing a similar study should consider utilizing a larger sample including Latinas and Latinos from other nationalities to take into consideration the heterogeneity of the Hispanic population in the U.S. To obtain a clearer perspective on how collectivism and individualism differ for Latino subgroups future research should consider including individual who are not U.S.-born and have been in the U.S. less than five years. Choosing a sample with diverse immigrant histories across the Latino subgroups would allow for a better comparison and enable researchers to explore whether levels of individualism and collectivism differ in each subgroup. Furthermore, researchers should consider including other measures such as an acculturation scales, language use, and ethnic identity to see how these constructs relate to COL and IND and which variable more strongly predict length of stay.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the financial support from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA grant numbers AA12218 and AA16973). We also appreciate the revolving loan funds and support provided by the Illinois Department of Alcohol and Substance Abuse.

Contributor Information

Leonard A. Jason, DePaul University

Roberto D. Luna, Adler University

Josefina Alvarez, Adler University.

Ed Stevens, DePaul University.

References

- Alegría M, Page JB, Hansen H, Cauce AM, Robles R, Blanco C, Cortes DE, Amaro H, Morales A, Berry P (2006). Improving drug treatment services for Hispanics: Research gaps and scientific opportunities. Drug Alcohol Dependence, 84, 76–S84. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez J, Jason LA, Olson BD, Ferrari JR, & Davis MI (2007). Substance abuse prevalence and treatment among Latinos and Latinas. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 6(2), 115–141. doi: 10.1300/J233v06n02-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo J, Miller WR, & Tonigan JS (2003). The influence of Hispanic ethnicity on long-term outcome in three alcohol treatment modalities. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64, 98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo J, Westerberg VS, & Tonigan JS (1998). Comparison of treatment utilization and outcome for Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 59, 286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Diaz L (2001). Hispanics, Latinos, or Americanos: The evolution of identity. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 7, 115–120. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.7.2.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras R, Álvarez J, DiGangi J, Jason LA, Sklansky L, Mileviciute I, & Ponziano F (2012). No place like home: Examining a bilingual-bicultural, self-run substance abuse recovery home for Latinos. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 3, 2–9. Retrieved from http://www.gjcpp.org/en/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon HM & Kemmelmeier M (2001). Cultural orientations in the United States: (Re) Examining differences among ethnic groups. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32, 348364. doi: 10.1177/0022022101032003006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaines SO, Marelich WD, Bledsoe KL Steers WN, Henderson MC Granrose CS,…& Page MS (1997). Links between race/ethnicity and cultural values as mediated by racial/ethnic identity and moderated by gender. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 1460–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero EG, Campos M, Urada D, & Yang JC (2012). Do cultural and linguistic competence matter in Latinos’ completion of mandated substance abuse treatment? Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 7, 34. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-7-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero EG, Marsh JC, Khachikian T, Amaro H, & Vega WA (2013). Disparities in Latino substance use, service use, and treatment: Implications for culturally and evidence-based interventions under health care reform. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 122, 805–813. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui CH, Triandis HC (1986) Individualism-collectivism: A study of cross-cultural researchers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 17, 225–248. doi: 10.1177/0022002186017002006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Davis MI, Ferrari JR, Anderson E (2007). The need for substance abuse after-care: Longitudinal analysis of Oxford House. Addictive Behaviors, 32, 803–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Digangi JA, Álvarez A, Contreras R, López-Tamayo R, Gallardo S, & Flores S (2013). Evaluating a bilingual voluntary community-based health organization. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 124), 321–338. dio: 10.1080/15332640.2013.836729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Olson BD, & Foley K (2008). Rescued lives: The OH approach to substance abuse. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Olson BD, Ferrari JR, & Lo Sasso AT (2006). Communal housing settings enhance substance abuse recovery. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 1727–1729. PMCID: PMC1586125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR & Weiss RV (2001) A review of temporal effects and outcome predictors in substance abuse treatment studies with long-term follow-ups: Preliminary results and methodological issues. Evaluation Review, 25, 113–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR (1996). Manual for Form-90: A structured assessment interview for drinking and related behaviors (Vol 5, Project MATCH Monograph Series). Rockville, MD: National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D (2011). Culture as situated cognition: Cultural mindsets, cultural fluency, and meaning making. European Review of Social Psychology, 22, 164–214. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2011.627187 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Coon HM, & Kemmelmeier M (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 3–72. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.128.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D & Sorensen N (2009). Understanding cultural syndrome effects on what and how we think: A situated cognition model In Wyer R, Hong Y-Y, & Chiu C-Y, (Eds), Understanding culture: Theory, research and application (pp. 25–52). New York, NY: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford House, Inc. Oxford House Manual 2008. Retrieved June, 2013, from http://www.oxfordhouse.org/userfiles/BasicOHManual2008a.pdf. Ethnic Minority Psychology. 21, 4, 548–560. dio: 10.1037/a0021370 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Des Rosiers SE, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Zamboanga BL, Huang S,….Szapocznik J (2014). Domains of acculturation and their effects on substance use and sexual behavior in recent Hispanic immigrant adolescents. Prevention Science,15, 385–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Weisskirch RS, Hurley EA, Zamboanga BL, Park IJK, Kim SY, Umaña-Taylor A, Castillo LG, Brown E, & Greene AD (2010). Communalism, familism, and filial piety: Are they birds of a collectivist feather? Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16(4), 548–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singelis TM (1994). The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 580–591. doi: 10.1177/0146167294205014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singelis TM, Triandis HC, Bhawuk DPS, Gelfand MJ (1995). Horizontal and vertical dimensions of individualism and collectivism: A theoretical and measureament refinement. Cross-Cultural Research, 29, 240–275. doi: 10.1177/106939719502900302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens EB, Jason LA, Ferrari JR, Hunter B (2011). Self-efficacy and Sense of Community among adults recovering from substance abuse. North American Journal of Psychology, 12(2): 255–264. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2010). The NSDUH Report: Substance Use among Hispanic Adults. Rockville, MD: Retrieved January 2015 from: http://www.taadas.org/publications/prodimages/NSDUH%20sub%20among%20hispan%20adults.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC (1993). Collectivism and Individualism as cultural syndromes. Cross-Cultural Research, 27, 155–180. doi: 10.1177/106939719302700301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC (1986). Individualism-Collectivism: A study of cross-cultural researchers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 17, 255–248.doi: 10.1177/0022002186017002006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC, Bontempo R, Villareal MJ, Asai M, & Lucca N (1988). Individualism and collectivism: Cross-cultural perspectives on self-ingroup relationships. Journal of personality and Social Psychology, 54(2), 323 dio: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.2.323 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC, McCusker C, & Hui CH (1990). Multimethod probes of Individualism and Collectivism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(5), 1006. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.59.5.1006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of the Census (2014). Current population survey. Retrieved on August 12, 2015, from https://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2014.html