Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Conventional therapies for hypereosinophilic syndromes (HES) have variable efficacy and carry significant long-term toxicities. Anti-IL-5 (mepolizumab) therapy has a glucocorticoid (GC)-sparing effect in GC-sensitive HES, but the efficacy of mepolizumab in treatment-refractory HES patients with severe disease has not been examined to date.

OBJECTIVE:

To identify predictors of response to mepolizumab in subjects with severe treatment-refractory HES and compare long-term outcomes in these subjects with HES subjects treated with conventional therapies.

METHODS:

Retrospective analysis of clinical and laboratory data from 35 HES subjects treated with mepolizumab and 55 HES subjects on conventional therapy, all followed at a single center, was performed.

RESULTS:

Peak eosinophilia, GC sensitivity, pulmonary involvement, HES clinical subtype, and pretreatment serum IL-5 were correlated with mepolizumab response. Despite evidence of more severe disease at baseline, mepolizumab-treated subjects had comparable long-term clinical outcomes to HES subjects treated with conventional therapies and reported improvements in therapy-related comorbidities. Subjects managed with mepolizumab monotherapy had fewer disease flares than HES subjects on conventional therapies or mepolizumab-treated HES subjects requiring additional HES therapies.

CONCLUSIONS:

This study confirms that mepolizumab is an effective and well-tolerated therapy for HES, but suggests that response is more likely in GC-responsive subjects with idiopathic or overlap forms of HES. A primary benefit of treatment is the reduction of comorbidity due to discontinuation or the reduction of conventional HES therapies. Although subjects who completely discontinued GC had the most benefit, high-dose mepolizumab was a safe and effective salvage therapy for severe, treatment-refractory HES. Published by Elsevier Inc. on behalf of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018;∎:∎-∎)

Keywords: Eosinophilia, Hypereosinophilic syndrome, Interleukin 5, Monoclonal antibody

Hypereosinophilic syndromes (HES) are defined by an absolute eosinophil count (AEC) >1.5 × 103/μL with evidence of eosinophil-related clinical manifestations. Currently available therapies, including glucocorticoids (GC), and immunomodulatory and cytotoxic therapies, have variable efficacy and significant toxicity.1 Safe and effective therapies that target eosinophils are clearly needed.2

Mepolizumab (Nucala; GlaxoSmithKline) is a monoclonal antibody to IL-5 developed for the treatment of asthma. Although early asthma trials failed to meet clinical efficacy endpoints, the reduction in AEC and tissue eosinophilia was observed, prompting several small studies of anti-IL-5 therapy (mepolizumab and reslizumab) in HES.3-5 Based on these results, a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of monthly mepolizumab (750 mg intravenously [IV]) was initiated in 84 GC-sensitive HES subjects. Mepolizumab was well tolerated and demonstrated a long-term GC-sparing effect in this trial and the subsequent open-label extension.6,7 More recently, the safety and efficacy of mepolizumab therapy was demonstrated in severe eosinophilic asthma,8-11 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,12 and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA).13 Mepolizumab is currently approved for the treatment of severe eosinophilic asthma (100 mg subcutaneous [SC] every 4 weeks) and EGPA (300 mg SC every 4 weeks).

Mepolizumab has been available since 2005 through a compassionate use program (HES CUP) to treat HES patients with life-threatening disease refractory or intolerant to conventional therapies, including GC.14 Efficacy in this patient population has not been examined to date. This retrospective analysis had 2 aims: (1) to describe the characteristics and predictors of mepolizumab response in a single-center cohort of HES subjects enrolled in HES CUP; and (2) to compare long-term outcomes of mepolizumab responders to HES subjects treated with conventional therapy.

METHODS

Study populations

Medical charts of subjects seen at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) between December 30, 1994, and August 18, 2015, on an institutional review board-approved protocol to study eosinophilic disorders (NCT00001406) were reviewed. All analyses were performed post hoc, and methods were not prespecified. For the purpose of this study, HES was defined as (1) hypereosinophilia (AEC 1.5 × 103/μL) on at least 2 occasions, (2) the presence of eosinophil-associated clinical manifestations, and (3) the absence of a secondary cause for which treatment is directed at the underlying etiology (eg, parasitic infection or neoplasia). NIH HES subjects were divided into 2 groups: (1) those who received ≥1 dose (750 mg IV) mepolizumab and (2) those who never received mepolizumab but were treated with conventional therapies. All subjects who received mepolizumab on HES CUP (NCT00244686) were approved by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) based on (1) the presence of life-threatening HES and failure of ≥3 conventional therapies or (2) prior mepolizumab trial participation with clinical response. All subjects signed informed consent. Interim analysis of all subjects receiving mepolizumab through HES CUP (clinical cutoff date September 23, 2013) was performed and quality checked by GSK. All other analyses were performed by NIH without GSK assistance.

Mepolizumab clinical response

The first part of the study focused on predictors of clinical response in subjects who received high-dose mepolizumab. Clinical response to mepolizumab was categorized as complete (improved or resolved symptoms and normal AEC on ≤10 mg of prednisone) or partial (improved symptoms and AEC requiring >10 mg prednisone and/or additional HES therapy) in subjects who remained on mepolizumab for >3 months (Figure 1, A). Nonresponders were defined by persistent eosinophilia and/or lack of symptomatic improvement leading to drug discontinuation after ≤3 monthly doses.

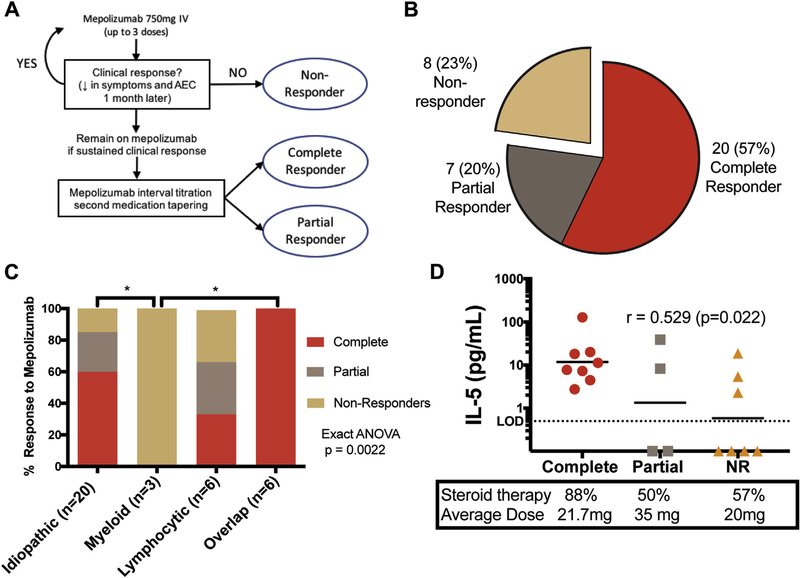

FIGURE 1.

Clinical response to mepolizumab. A, Schematic of clinical decision making and determination of response to mepolizumab. B, Numbers and percentages of HES subjects by response. C, Mepolizumab response by clinical subtype. Exact ANOVA testing was performed on clinical subtype and mepolizumab response (P =.0022). *Indicates significant differences in pairwise comparisons (adjusted P < .05). D, Pretreatment serum IL-5 levels in 19 subjects with active disease, categorized by response to mepolizumab. The horizontal line indicates the geometric mean. Red circles denote complete responders, gray squares partial responders, and orange triangles non-responders. Baseline percentage of subjects on GC therapy and mean dose are indicated. AEC, Absolute eosinophil count; ANOVA, analysis of variance; GC, glucocorticoid; HES, hypereosinophilic syndrome; IV, intravenous; LOD, limit of detection; NR, nonresponder.

Long-term outcomes analysis

In the second part of the study, long-term outcomes were compared between HES subjects treated with mepolizumab for >6 months (MEPO HES) and those who never received mepolizumab (CONTROL HES) (Figure 2). Baseline was defined as the date of the first mepolizumab infusion (MEPO HES) or the initial NIH visit (CONTROL HES). All subjects included in this comparison were followed for ≥5 years or died within 5 years of the baseline visit. Subjects who received <6 doses of mepolizumab (n = 3; all alive at the clinical cutoff time point) were excluded regardless of the length of clinical follow-up.

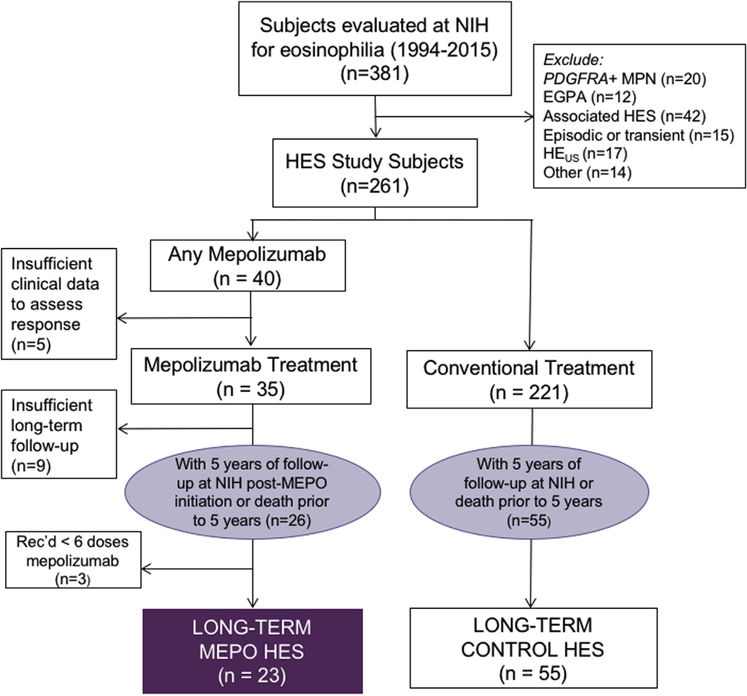

FIGURE 2.

Study populations. EGPA, Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis; HES, hypereosinophilic syndrome; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasm; NIH, National Institutes of Health; PDGFRA-platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha

Clinical and laboratory variables

Baseline study variables included HES clinical subtype (myeloid, lymphocytic, idiopathic, or overlap15); peak AEC (highest documented AEC before baseline); prior HES therapies; HES onset (first documented AEC >1.5 × 103/μL); duration of HES, from disease onset to baseline; HES organ system involvement (constitutional, cardiac, neurologic, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, hematologic, otolaryngologic, and musculoskeletal); length of clinical follow-up; drug therapy at initial and last visit; and GC sensitivity: Group I (symptoms controlled on≤10 mg prednisone daily), Group II (requires 11–20 mg prednisone daily), Group III (requires ≥21 mg prednisone daily), or Group IV (unresponsive to 60 mg prednisone daily for ≥1 week).16 Study variables assessed from the baseline visit until the last clinical encounter were scored by a single physician and included death, malignancy, HES-related hospitalizations (admitted for >24 hours), HES medications at initial and last clinical encounter, flares (disease worsening on >4 weeks’ stable therapy necessitating a change in HES medication), new diagnosis or exacerbation of comorbidity related to HES treatment, and improvement in therapy-related morbidity.

Assessment of serum cytokine levels

Serum cytokines were measured by Luminex (IL-5, IL-3, IL-13, and GM-CSF; Millipore, Billerica, Mass) or ELISA (IL-33; Raybiotech, Norcross, Ga) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Samples were tested in duplicate. Lower limits of detection were 0.5 pg/mL (IL-5), 0.7 pg/mL (IL-3), 1.3 pg/mL (IL-13), 7.5 pg/mL (GM-CSF), and 2.2 pg/mL (IL-33). Samples with undetectable levels were assigned a value of 0.1 pg/mL.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test (paired analyses) for 2-sample comparison of numeric outcomes and Fisher’s exact test for comparison of nominal or binary outcomes. A 2-sided exact Cochrane-Armitage trend test was performed on end-organ manifestations and response to mepolizumab therapy. Spearman correlation analyses measured association of GC sensitivity and serum cytokine levels with the 3 categories of mepolizumab response. Exact analysis of variance (ANOVA) testing using equally spaced scores was used to compare HES subtype response with mepolizumab. Adjustments for multiple comparisons used Holm’s adjustment and defined families by each Table or Figure, except for pairwise comparisons after ANOVA analyses that used a step-down procedure based on Tukey-Welch levels.17 Adjusted P values were used for interpretation of serum cytokine levels other than IL-5 due to their exploratory nature. P value <.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

RESULTS

Study cohort

After excluding eosinophilic subjects with platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA)-positive myeloid neoplasm, biopsy-proven EGPA, associated HES, episodic or transient HES, hypereosinophilia of unknown significance, and subjects without documentation of AEC 1.5 × 103/μL, 261 subjects with HES were included in the retrospective analysis (Figure 2). Of the 261 subjects, 40 received ≥1 dose of mepolizumab 750 mg IV. Clinical response was evaluable in 35 of 40 (88%). Thirteen subjects were enrolled after participation in a prior clinical trial of mepolizumab3,6,18 and 22 subjects for life-threatening, treatment-refractory HES (Table I). Demographic characteristics at enrollment and ultimate treatment status of 189 non-NIH HES subjects enrolled in HES CUP before September 23, 2013, were no different from those of the 29 of 35 NIH HES subjects enrolled during the same time frame, with the exception of a longer duration of HES illness in the NIH cohort (Table E1, available in this article’s Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org).

Table I.

Characteristics of mepolizumab-treated subjects at enrollment

| Characteristic | Subjects (n [ 35) |

|---|---|

| Median age (range) | 44 (12–72) |

| Gender (M/F) | 13/22 |

| Race | |

| White | 26 (74%) |

| Black/African American | 4 (11%) |

| Asian | 2 (6%) |

| Other | 3 (9%) |

| HES subtype | |

| Idiopathic | 20 (57%) |

| Myeloid variant | 3 (9%) |

| Lymphocytic variant | 6 (17%) |

| Overlap | 6 (17%) |

| Median duration of HES, y (range) | 4.6 (0.38–21) |

| Enrollment inclusion criteria | |

| Prior participation in clinical trial with response | 13 (37%) |

| Treatment-refractory, with life-threatening HES | 22 (63%) |

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the 35 NIH HES subjects enrolled on the GSK-sponsored mepolizumab compassionate use program (HES CUP). GSK, GlaxoSmithKline; HES, hypereosinophilic syndrome; NIH, National Institutes of Health.

TABLE E1.

Characteristics of NIH cohort versus cohorts at other sites

| HES NIH (n = 29) | HES Other (n = 189*) | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | |||

| ≤ 45 | 12 (41%) | 78 (42%) | NS |

| >45 | 17 (59%) | 108 (58%) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 10 (34%) | 91 (49%) | NS |

| Female | 19 (66%) | 96 (51%) | |

| Duration of HES (y) | |||

| ≤5 | 11 (38%) | 108 (61%) | P = .027 |

| >5 | 18 (62%) | 71 (40%) | |

| Enrollment category | |||

| Previous trial Participant | 12 (42%) | 62 (33%) | NS |

| Compassionate use | 17 (58%) | 127 (67%) | |

| Current status | |||

| On study | 22 (76%) | 128 (68%) | NS |

| Prematurely withdrawn | 7 (24%) | 60 (32%) | |

| Missing information | 0 | 1 (0.1%) | |

Data collected by GSK as of cutoff date September 23, 2013, which includes 29 NIH subjects (HES NIH) and 189 subjects at other sites (HES Other). Six NIH subjects were not captured in this analysis because they were enrolled after September 23, 2013.

GSK, GlaxoSmithKline; HES, hypereosinophilic syndrome; NIH, National Institutes of Health; NS, not significant.

The number of subjects in the HES Other group for whom data were available varied slightly for the different parameters: Age (n = 186), Gender (n = 187), Duration of Illness (n = 179). The denominators used for analysis included only subjects with available data.

Response to mepolizumab

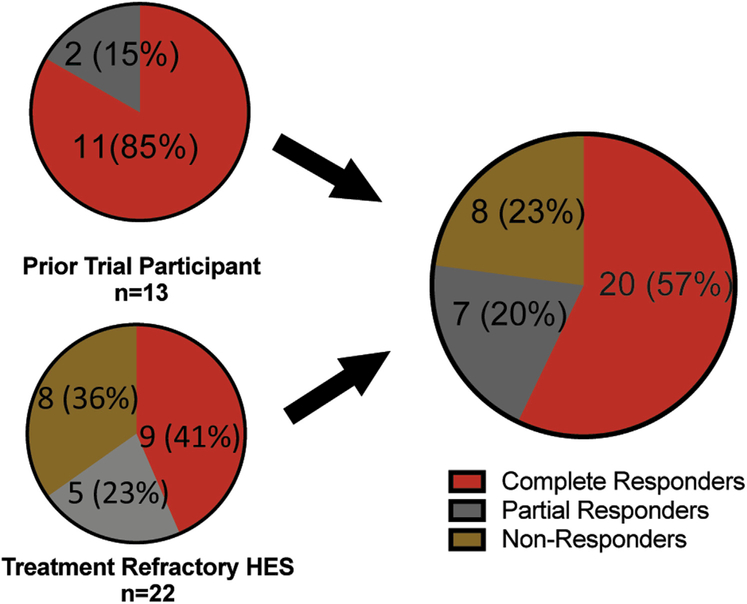

Among the 35 HES subjects treated with mepolizumab and with an evaluable response, 57% (20 of 35) demonstrated a complete response, 20% (7 of 35) had a partial response, and 23% (8 of 35) were nonresponders (Figure 1, A and B). Subjects enrolled based on prior trial participation with clinical response had a higher rate of complete (10 of 12; 83%) and partial response (2 of 12; 17%) than those enrolled because of treatment-refractory, life-threatening HES (complete response 10 of 23 [43%]; partial response 5 of 23 [22%]; Figure E1, available in this article’s Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org). A detailed listing of each subject with his or her clinical subtype, AEC, and therapy at baseline and at 3 months is provided grouped by response to mepolizumab in Table E2 (available in this article’s Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org). AEC measured 3 months after the first dose was within normal limits in all 20 complete responders but remained elevated in 5 of 7 partial responders and 7 of 8 nonresponders.

FIGURE E1.

Clinical response to mepolizumab by enrollment criteria. Clinical response to mepolizumab in the NIH study cohort as a whole (right) and based on enrollment criteria (left). Subjects who participated in a prior trial of mepolizumab in HES with clinical response are shown in the upper-left panel and subjects enrolled directly on the compassionate use protocol for treatment-refractory, life-threatening HES are shown in the lower left. HES, Hypereosinophilic syndrome; NIH, National Institutes of Health.

TABLE E2.

Mepolizumab-treated subjects by clinical response

| Subject | Clinical subtype | Baseline therapy | Baseline AEC × 103/μL | Post 3 MEPO therapy | Post 3 MEPO AEC × 103/μL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete responders | |||||

| 2 | Idiopathic | P 30 mg qD | 1.2 | P 5 mg qOD | 0.033 |

| 4 | Idiopathic | P 20 mg qD | 0.518 | P 5 mg qOD | 0.093 |

| 8 | Idiopathic | MP 2.5 mg qD | 1.647 | MP 3 mg qD | 0.106 |

| 9 | Overlap | P 7.5 mg qD | 0.760 | None | 0.030 |

| 10 | Idiopathic | P 20 mg qD | 1.920 | P 2 mg qOD, P 5 mg qOD | 0.020 |

| 11 | Idiopathic | MP 4 mg qD | 0.707 | MP 2 mg qOD, MP 3 mg qOD | 0.075 |

| 13 | Overlap | P 10 mg qOD, omalizumab | 0.285 | P 10 mg qOD, omalizumab | 0.050 |

| 16 | Idiopathic | P 5 mg qOD, P 10 mg qOD | 1.016 | None | 0.124 |

| 17 | Lymphocytic | P 20 mg qOD | 0.266 | P 1 mg qOD, P 5 mg qOD | 0.020 |

| 18 | Idiopathic | MP 16 mg qD | 1.600 | MP 4 mg qD | 0.094 |

| 21 | Idiopathic | P 20 mg qD | Normal | None | Normal |

| 23 | Overlap | P 25 mg qD | 0.890 | P 5 mg qOD, P 3 mg qOD | 0.154 |

| 24 | Idiopathic | P 5 mg qD | 3.500 | None | 0.040 |

| 25 | Overlap | P 100 mg qD | 1.170 | P 25 mg qD | 0 |

| 26 | Overlap | P 20 mg qD | 0.370 | P 10 mg qD | 0.071 |

| 28 | Overlap | Beclomethasone | 4.978 | NA | Normal |

| 30 | Idiopathic | P 5 mg qD | 1.100 | None | 0.100 |

| 32 | Idiopathic | None | 2.989 | None | 0.089 |

| 34 | Idiopathic | None | 9.280 | None | 0.160 |

| 35 | Lymphocytic | P 20 mg qD | 2.403 | P 2 mg qOD, P 5 mg qOD | 0.392 |

| Partial responders | |||||

| 1 | Idiopathic | P 40 mg qD | 8.660 | P 20 mg qD | 0.590 |

| 3* | Idiopathic | P 30 mg qD, HU 1 gm qD | 5.170 | P 12 mg qD | 5.370 |

| 20* | Idiopathic | P 30 mg qD, IMAT, HU | 14.337 | IMAT, HU | 5.580 |

| 22 | Lymphocytic | P 20 mg qD | 1.780 | P 15 mg | 0.890 |

| 29* | Lymphocytic | P 20 mg qD | 0.788 | P 5 mg | 0.152 |

| 31* | Idiopathic | pegIFN 180 mcg qwk | 5.511 | None | 0.048 |

| 33* | Idiopathic | HU 500 qD | 3.040 | None | 4.000 |

| Nonresponders | |||||

| 5† | Lymphocytic | P 35 mg qD | 6.610 | P 30 mg qD | 0.490 |

| 6 | Idiopathic | IFN 3 mU TIW | 7.800 | IFN 3 mU TIW, Cytoxan | 6.700 |

| 7 | Myeloid | HU 500 mg q3D | 1.610 | HU 500 mg q3D | 1.700 |

| 12 | Myeloid | MP 500 mg iv BID | 2.542 | P 12.5 mg qD | 2.600 |

| 14 | Idiopathic | P 30 mg qD | 6.350 | None | 5.450 |

| 15†,‡ | Lymphocytic | None | 5.000 | None | 1.803 |

| 19 | Idiopathic | IFN 4mU qD | 1.353 | MTX 20 mg qwk | 5.640 |

| 27‡ | Myeloid | Nilotinib BID, P 10 mg qD | 7.220 | Nilotinib BID, P 10 mg qD | 10.620 |

AEC, Absolute eosinophil count; HU, hydroxyurea; IFN, interferon-α, IMAT, imatinib; MP, methylprednisolone; MTX, methotrexate; P, prednisone.

Ultimately required ≥10 mg prednisone or alternative agent in addition to mepolizumab to control symptoms and AEC.

No change in symptoms despite drop in AEC.

Received 1 dose of mepolizumab only and started alternative therapy due to inadequate response.

Predictors of response to mepolizumab

Among the many baseline variables assessed, only peak AEC, GC sensitivity, pulmonary involvement, HES clinical subtype, and serum cytokine levels were significantly correlated with mepolizumab response (Figure 1, D; Table II; Tables E3 and E4, available in this article’s Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org). Geometric mean peak AEC ranged from 5.24 × 103/μL (0.8–20.2 × 103/μL) in complete responders to 13.04 × 103/μL (5.4–79 × 103/μL) in nonresponders and was negatively correlated with response (r = 0.436, adjusted P = .038). GC-refractory subjects were also more likely to fail mepolizumab therapy (r = 0.845, adjusted P < .001). Although the number of organ systems involved was comparable in all groups, those with pulmonary involvement were more likely to respond to mepolizumab (adjusted P = .01), whereas those with cardiac involvement showed a trend toward poorer response (adjusted P = .05) (Table E3, available in this article’s Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org).

Table II.

Baseline clinical and laboratory predictors of mepolizumab response

| Mepolizumab response |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Complete (n = 20) | Partial (n = 7) | None (n = 8) | Significance |

| Duration of HES, y (range) | 6.01 (0.38-1.4) | 5.54 (1.24-14.8) | 6.13 (0.82-15.4) | NS |

| GM peak AEC x 103/μL (range) | 5.24 (0.8-20.2) | 19.28 (2.9-80.11) | 13.04 (5.4-79) | r = -0.436 CI: -0.672 to -0.121 P = .009* |

| Baseline BMI, kg/m2 (range) | 26.8 (19.5-38.4) | 25.9 (20.5-43.9) | 27.4 (20.3-32.7) | NS |

| No. of organ systems involved (range) | 5 (1-6) | 5 (3-5) | 4 (3-5) | NS |

| GC sensitivity† | ||||

| Group I | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Group II | 10 | 0 | 0 | r = 0.845 CI: 0.694 to 0.925‡ |

| Group III | 5 | 3 | 0 | P = .00017 |

| Group IV | 0 | 3 | 6 | |

| Insufficient data | 3 | 1 | 2 | NS |

Spearman correlations were performed with individual baseline variables and response to mepolizumab (nonresponder ¼ 1, partial ¼ 2, complete ¼ 3). Median values within each response group are reported, unless otherwise indicated.

AEC, Absolute eosinophil count; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; GC, glucocorticoid; GM, geometric mean; HES, hypereosinophilic syndrome; NS, unadjusted P > .05.

Adjusted P = .038.

Definitions of GC sensitivity: Group I controlled on ≤10 mg prednisone, Group II controlled on 11–20 mg prednisone, Group III controlled on ≥21 mg prednisone, Group IV, nonresponder to 60 mg prednisone daily for 1 week. Correlation was performed between mepolizumab response and GC sensitivity, with Group IV (GC nonresponder) assigned the lowest value and Group I (controlled with ≤10 mg prednisone) assigned the highest value.

Adjusted P = .00085.

TABLE E3.

Spectrum of baseline end organ manifestations among the clinical response groups

| Mepolizumab response |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organ system | NIH cohort (n = 35) | Complete (n = 20) | Partial (n = 7) None (n = 8) | Unadjusted P value | Adjusted P value | |

| Constitutional | 17 (49%) | 7 (35%) | 4 (57%) 6 (75%) | NS | NS | |

| Cardiac | 8 (23%) | 1 (5%) | 3 (43%) 4 (50%) | .0069 | .0553 | |

| Neurologic | 9 (26%) | 5 (25%) | 2 (29%) 2 (25%) | NS | NS | |

| Pulmonary* | 26 (74%) | 19 (95%) | 4 (57%) 3 (38%) | .0014 | .0122 | |

| Gastrointestinal | 15 (43%) | 12 (60%) | 2 (29%) 1 (13%) | .0227 | NS | |

| Skin/soft tissue | 27 (77%) | 15 (75%) | 6 (86%) 6 (75%) | NS | NS | |

| Otolaryngologic | 19 (54%) | 14 (70%) | 4 (57%) 1 (13%) | .0131 | NS | |

| Hematologic | 13 (37%) | 4 (20%) | 3 (43%) 6 (75%) | .0102 | NS | |

| Musculoskeletal | 11 (31%) | 6 (30%) | 3 (43%) 3 (38%) | NS | NS | |

Two-sided Cochrane-Armitage trend test performed. Both unadjusted P values and adjusted P values are shown (adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Holm method). NIH, National Institutes of Health; NS, not significant.

TABLE E4.

End organ manifestations (CONTROL HES vs MEPO HES)

| Organ system | Long-term CONTROL HES | Long-term MEPO HES | Fisher’s exact test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constitutional | 27 (49%) | 10 (43%) | NS |

| Cardiac | 7 (13%) | 3 (13%) | NS |

| Neurologic | 9 (16%) | 6 (26%) | NS |

| Pulmonary | 29 (53%) | 20 (87%) | P = .0047* |

| Gastrointestinal | 21 (38%) | 13 (57%) | NS |

| Skin/soft tissue | 36 (65%) | 18 (78%) | NS |

| Otolaryngologic | 21 (38%) | 13 (57%) | NS |

| Hematologic | 17 (31%) | 4 (17%) | NS |

| Musculoskeletal | 21 (38%) | 7 (30%) | NS |

HES, Hypereosinophilic syndrome; NS, not significant.

Holm adjusted P = .042.

HES clinical subtype was a significant predictor of response to mepolizumab (Figure 1, C; P = .0022). HES overlap subtype was the most responsive, and PDGFRA-negative myeloid HES (MHES) the most refractory. Pairwise comparisons demonstrated significant differences in mepolizumab response between myeloid and overlap HES (adjusted P = .023) and between myeloid and idiopathic HES (adjusted P = .022). In lymphocytic variant HES (LHES), where eosinophilia is driven by T-cell overproduction of IL-5, mepolizumab response was equally divided among response groups.

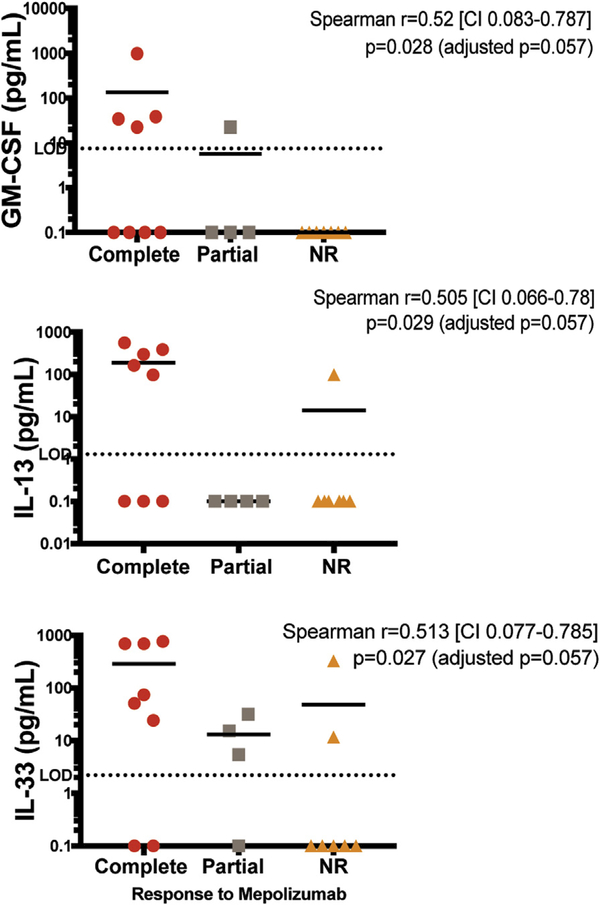

Serum levels of IL-5, the target of mepolizumab therapy, as well as levels of other cytokines implicated in eosinophilia, were measured in 19 subjects with available samples who received mepolizumab for treatment-refractory, life-threatening HES. In contrast to published data from the prior placebo-controlled trial in GC-sensitive subjects,6 increased serum IL-5 was positively correlated with mepolizumab responsiveness in these treatment-refractory HES subjects (r = 0.53, P = .02; Figure 1, D). Pretreatment serum levels of IL-33, a known driver of IL-5 production, were also positively correlated with mepolizumab response (Figure E2, available in this article’s Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org). Serum levels of IL-13, a type 2 cytokine often produced in concert with IL-5, and GMCSF, a cytokine that drives eosinophilopoiesis, showed a trend toward an association with response, but were below the level of detection in many subjects. Serum levels of IL-3 were undetectable.

FIGURE E2.

Pretreatment serum cytokine levels by treatment response. Pretreatment serum cytokine levels in 19 subjects with active disease, categorized by response to mepolizumab. The horizontal bars indicate the geometric mean within each group. Dotted lines indicate the limit of detection for each assay. Samples below the limit of detection are assigned a value of 0.1 pg/ mL. Red circles denote complete responders, gray squares partial responders, and orange triangles nonresponders. CI, Confidence interval; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; NR, nonresponder.

Long-term outcomes of mepolizumab treatment

To evaluate the long-term clinical outcomes of mepolizumab treatment, subjects who received >6 doses of mepolizumab treatment with ≥5 years of clinical follow-up after mepolizumab initiation (MEPO HES, n = 23) were compared with HES subjects who never received mepolizumab therapy with ≥5 years of clinical follow-up (CONTROL HES, n = 55). Subjects in either group who died before 5 years of follow-up were also included (Figure 2).

The 2 groups were similar with respect to baseline demographic characteristics, length of follow-up, peak AEC, number of organ systems involved, or HES subtype (Table III). However, MEPO HES subjects were more likely to have pulmonary involvement (87% vs 53%, adjusted P < .05) (Table E4, available in this article’s Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org). More importantly, the MEPO HES group had a longer median duration of HES illness before baseline (4.58 vs 1.98 years, adjusted P< .05), had failed more therapies before treatment (median 3 vs 1, adjusted P < .001), and were less likely to respond to GC (adjusted P < .001) (Table III). These features suggest greater disease severity in the MEPO HES cohort. Despite this, mortality was not increased in the MEPO HES group (9% [2 of 23] vs 20% [11 of 55] in the CONTROL HES group, P = NS; Table IV). A total of 10 subjects (4 in the MEPO HES group and 6 in the CONTROL HES group) developed malignancies (P = NS).

Table III.

Baseline characteristics of long-term MEPO vs CONTROL HES

| Long-term group | CONTROL HES (n = 55) | MEPO HES (n = 23) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (M/F) | 27/28 | 9/14 | NS |

| Median age (range) | 53.4 (1.8-85.2) | 44.7 (12.2-72) | NS |

| Race | |||

| White | 45 (81%) | 19 (83%) | NS |

| Black | 4 (7%) | 3 (13%) | |

| Other | 6 (11%) | 1 (4%) | |

| Median follow-up, y (range) | 7.3 (0.003-17.4) | 8.5 (0.7-11) | NS |

| HES subtype | NS | ||

| Idiopathic | 25 (45.5%) | 15 (65.2%) | |

| Myeloid variant | 2 (3.6%) | 0 | |

| Lymphocytic variant | 10 (18.2%) | 3 (13%) | |

| Overlap | 18 (32.7%) | 5 (21.7%) | |

| GM peak AEC cells × 103/μL (range) | 7.51 (0.91-10) | 6.40 (0.8-55) | NS |

| Median duration of HES, y (range) | 1.98 (0.38-21.4) | 4.58 (0.16-34.1) | P = .0046 Adjusted P = .032 |

| Median no. of organ systems involved (range) | 3 (2-7) | 5 (2-7) | NS |

| Median no. of prior therapies tried (range) | 1 (0-6) | 3 (1-6) | P = .0002 Adjusted P = .0018 |

| GC sensitivity* | |||

| Group I | 26 (47%) | 2 (9%) | Cochrane-Armitage trend P = .00017 Adjusted P = .0017 |

| Group II | 10 (18%) | (39%) | |

| Group III | 3 (5%) | 7 (30%) | |

| Group IV | 1 (2%) | 1 (4%) | |

| No data | 15 (27%) | 4 (17%) | NS |

AEC, Absolute eosinophil count; GC, glucocorticoid; GM, geometric mean; HES, hypereosinophilic syndrome; NS, unadjusted P > .05.

Definitions of GC sensitivity: Group I controlled on 10 mg prednisone, Group II controlled on 11–20 mg prednisone, Group III controlled on 21 mg prednisone, Group IV, nonresponder to 60 mg prednisone daily for 1 week.

Table IV.

Long-term clinical outcomes

| Long-term group | CONTROL HES (n = 55) | MEPO HES (n = 23) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subject status | Alive: 44 (80%) | Alive: 21 (91%) | NS |

| Malignancy | 6 (10.9%) 3 BCC, 1 MM, 1 ovarian ca, 1 SCC | 4 (17.4%) 1 BCC, 1 AITL, 1 colon ca (aFAP), 1 SCC | NS |

| HES-related hospitalizations | |||

| Affected subjects | 11 (20%) | 2 (8.7%) | |

| Episodes (mean rate) | 25 (6.6) | 2 (0.01484) | NS* |

| New/worsening therapy-related morbidity | |||

| Affected subjects | 21 (38%) | 2 (8.7%) | |

| Reports (mean rate) | 44 (0.105) | 18 (0.0867) | NS* |

| Improvement in therapy-related morbidity | |||

| Affected subjects | 0 | 6 (26%) | |

| Reports (mean rate) | 0(0) | 8 (0.04732) | P = .0004† |

| Disease flares episodes requiring medication change | |||

| Affected subjects | 44 (80%) | 11 (48%) | |

| Episodes | 204 | 57 (overall) 26 (MEPO alone, n = 16) 31 (MEPO + other therapy, n = 7) | |

| Mean rate | 7.034 | 0.427 (overall) 0.193 (MEPO alone, n = 16) 0.960 (MEPO + other therapy, n = 7) | NS* (overall) Kruskal-Wallis P = .0147‡ |

Subject event rate is events divided by follow-up time in years and the mean rate is presented.

aFAP, Attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis; AITL, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; BCC, basal cell carcinoma; HES, hypereosinophilic syndrome; MM, multiple myeloma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

After normalization by individual subject follow-up time, statistical analysis was performed on individual subject event rate.

Adjusted P value = .0024.

Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA, nonparametric with multiple comparisons against CONTROL HES vs MEPO alone adjusted P = .016; CONTROL HES vs MEPO + other therapy P = NS; MEPO alone vs MEPO + other therapy adjusted P = .0096.

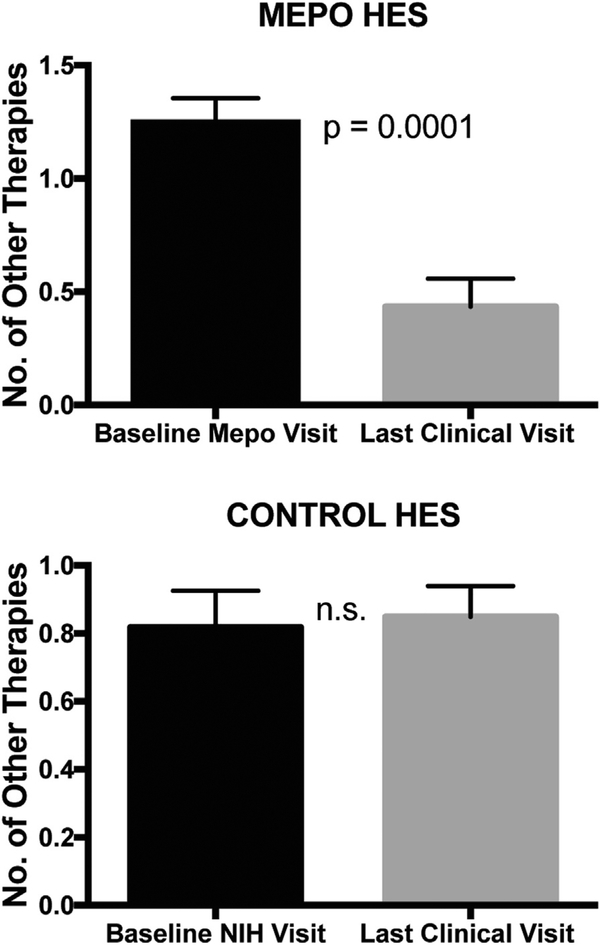

Outcomes associated with long-term morbidity, including HES-related hospitalizations, therapy-related morbidity, and disease flares, were comparable between the 2 groups with 2 exceptions (Table IV). MEPO HES subjects reported improvement in therapy-related morbidity (8 vs 0 reports in CONTROL subjects; P < .001; Table IV). This was likely related to the ability to discontinue medications with known toxicities in the MEPO HES group (from 1.3 to 0.4; P < .001) but not the CONTROL HES group (0.8 to 0.8; P = NS) (Figure 3). Second, when the MEPO HES group was separated into subjects ultimately managed on mepolizumab alone (MEPO alone) versus those requiring the addition of another agent (MEPO + other therapy), there was a significant difference in the rates of disease flare between the CONTROL HES, MEPO alone, and MEPO + other therapy (P < .05, Table IV). Pairwise comparisons reveal that the MEPO alone group had significantly fewer disease flares(mean0.193flares per year) than those in the CONTROL HES group (mean 7.034 flares per year) or the MEPO þ other therapy group (mean 0.96 flares per year) (P < .05).

FIGURE 3.

The number of HES medications at baseline and last study visit (excluding mepolizumab) were enumerated for subjects treated with conventional HES therapy (CONTROL HES) and those treated with mepolizumab (MEPO HES). Bars indicate mean and the lines indicate the standard deviation of each group. Paired Wilcoxon signed rank test was performed in each group. HES, hypereosinophilic syndrome.

Mepolizumab dosing in responders

The clinical status and mepolizumab dosing as of the clinical cutoff date are provided for each MEPO HES subject in Table V. All subjects initiated mepolizumab therapy at 750 mg IV monthly. During the follow-up period, mepolizumab dosing interval extension was achieved in 19 of 23 subjects (range every 5–12 weeks) (Table V). Dose reduction to less than 700 mg was successful in 8 of 11 (73%) subjects attempted. Six subjects were able to reduce the dose to 500 mg IV every 8 to 12 weeks, and 2 were receiving 300 mg SC monthly. A taper was not attempted in the remaining 12 subjects for logistical reasons (n = 4), partial response on the maximal dose (n = 3), or because therapy was already discontinued (n = 5).

Table V.

Current status and therapy of long-term mepolizumab responders

| Subject | Current mepolizumab treatment |

Current/last mepolizumab dose |

Dosing frequency (wk) |

Concurrent HES therapies | Dose taper attempt? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Y | 500 mg IV | Q12 | Y | |

| 4 | Y | 500 mg IV | Q12 | Y | |

| 10 | Y | 300 mg SC | Q4 | Y | |

| 11 | Y | 500 mg IV | Q8 | Y | |

| 16 | Y | 300 mg SC | Q4 | Y | |

| 17 | Y | 500 mg IV | Q12 | P 10 mg | Y |

| 30 | N* | 500 mg IV | Q10 | Y | |

| 35 | Y | 500 mg IV | Q8 | Y | |

| 18 | Y | 750 mg IV | Q8 | Medrol 4 mg | Y → F |

| 23 | Y | 750 mg IV | Q12 | Y → F | |

| 26 | Y | 750 mg IV | Q6 | P 5 mg | Y → F |

| 8 | Y | 750 mg IV | Q12 | N† | |

| 21 | Y | 750 mg IV | Q8 | N† | |

| 24 | Y | 750 mg IV | Q12 | N† | |

| 25 | Y | 750 mg IV | Q5 | N† | |

| 20 | Y | 750 mg IV | Q4 | IFNα 1 mU sc | N‡ |

| 31 | Y | 750 mg IV | Q8 | P 10 mg | N‡ |

| 34 | Y | 750 mg IV | Q6 | N‡ | |

| 1 | N§ | 750 mg IV | Q4 | Budesonide 9 mg, P 50 mg | NA |

| 13 | N¶ | 750 mg IV | Q12 | Omalizumab q2 week | NA |

| 28 | N¶ | 750 mg IV | Q4 | NA | |

| 29 | N*,§ | 750 mg IV | Q4 | P 6 mg | NA |

| 32 | N* | 750 mg IV | Q8 | NA |

Status as of August 18, 2015. Mepolizumab discontinued due to

malignancy

death, or

patient choice. Regarding attempts to taper to 500 mg IV, Y is successfully taper dose. Dose taper to 500 mg not attempted due to

logistical reasons (ie, drug not managed by NIH) or due to

clinical reasons. Partial responders are subjects 1, 20, 29, and 31. F, Attempted taper but patient unable to tolerate; HES, hypereosinophilic syndrome; IV, intravenous; N, no attempt made to taper; NA, not applicable as the patient no longer on therapy; SC, subcutaneous.

DISCUSSION

Although prior studies have demonstrated that mepolizumab (750 mg IV monthly) is well tolerated and enables sustained GC dose reduction in HES,6,19 little is known about predictors of response or the long-term effects of mepolizumab as compared with conventional therapy in those subjects with the greatest need for safe and effective alternative therapies (ie, severe GC-refractory HES). This 2-part retrospective study begins to address these questions. Although our data confirm the safety and efficacy of mepolizumab treatment in HES in general, they also highlight some important issues that may impact the selection of HES patients for mepolizumab therapy in the future.

A strength of this retrospective study is the diverse group of HES subjects, including those with GC-sensitive disease (prior clinical trial participants) and those with treatment-refractory, life-threatening disease, a group that was excluded from prior clinical trial participation and likely represents the other extreme of HES. Neither group alone represents the true spectrum of HES. Data from a multicenter retrospective analysis of treatment responses demonstrated that although 85% of HES patients respond to some dose of GC at 1 month, 40% of these individuals ultimately discontinue therapy because of the development of resistance or medication intolerance.1 These data suggest that 30% to 40% of HES patients are long-term GC responders. The proportion of HES patients with severe treatment-refractory disease is unknown. The overall mepolizumab response rate in the current study was 77% (complete and partial responders combined). This may be an underestimate of the response rate in the true general HES population given that those with treatment-refractory, life-threatening HES comprised two-thirds of the study cohort.

In the prior placebo-controlled trial of mepolizumab in GC-sensitive HES subjects, 84% (36 of 43) receiving drug met the primary endpoint, defined as ability to taper prednisone dose ≤10 mg daily, compared with 43% (18 of 42) receiving placebo.6 Unfortunately, these response rates cannot be directly compared with those in this study because of differences in the definition of clinical response and the significant placebo response rate in the prior trial. Nevertheless, the data suggest that high-dose mepolizumab may be less effective in subjects with HES who are GC-resistant, because all of the mepolizumab nonresponders in this study were also GC-resistant (n = 6) or had insufficient data for analysis (Table II), whereas none of the complete responders and 3 of 7 of the partial responders were GC-resistant. Nonetheless, the 3 mepolizumab partial responders who were GC-resistant were able to taper background therapy with clinical improvement despite incomplete disease and AEC control at 3 months.

A number of additional clinical and laboratory features were significantly associated with mepolizumab response: peak AEC, HES clinical subtype, and type of organ system involvement. Higher peak AEC may be a surrogate for disease severity and/or overall eosinophilic drive, which at some threshold may be insurmountable for even high-dose mepolizumab. Alternately, high peak AEC in the nonresponders and partial responders may reflect a different (IL-5 independent) mechanism driving the eosinophilia. The lack of response noted in the MHES subjects, all 3 of whom had JAK2 mutations, supports the latter hypothesis.

Recent data suggest that clinical subtype may be an important predictor of response to different HES therapies such as GC and imatinib.16,20 In the prior placebo-controlled mepolizumab trial, response rates in the subjects with LHES were similar to those in the study group as a whole, but LHES subjects were less likely to maintain eosinophil suppression.19 Data from this study are consistent with a role for clinical subtype in predicting response to mepolizumab, with the most compelling differences between the myeloid subtypes versus idiopathic or overlap HES. This might be due to different mechanisms of disease pathogenesis. For example, proliferation of clonal eosinophils (MHES) may be relatively IL-5 independent, whereas eosinophilia in the context of a Th2 response, as in eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease (overlap HES), may be relatively more dependent on IL-5. Mepolizumab responders were significantly more likely to have pulmonary involvement, whereas cardiac involvement was more frequent in nonresponders. Although this may reflect organspecific differences in eosinophil pathogenesis in HES, alternative explanations include the confounding effects of HES subtype and GC sensitivity.

Serum cytokine analysis in subjects with active disease before mepolizumab treatment demonstrated positive correlations between mepolizumab response and baseline serum levels of IL-5 and IL-33 (a driver of ILC2 production of IL-5)21 and a trend toward a correlation with GM-CSF and IL-13. These results support IL-5-driven eosinophilia as a major predictor of response. This relationship was likely missed in the prior placebo-controlled trial because nearly all subjects were in remission on moderate-to-high doses of GC at the time of sample acquisition.6,19 In many untreated HES subjects, serum IL-5 levels are detectable and correlate with AEC.22 Little is known about the effect of therapy on serum IL-5 levels in HES, although in one study, AEC suppression by prednisone, but not by interferon-a, led to IL-5 reduction in a subject with LHES.23 Because overproduction of eosinophilopoietic cytokines other than IL-5 could circumvent the action of the drug, serum levels of GM-CSF and IL-3 were also assessed. The trend toward a positive correlation between serum GM-CSF levels and mepolizumab response suggests that this is not the case for GM-CSF. Whether increased local production of IL-3 in the bone marrow could be responsible for treatment failure in some cases cannot be excluded.

In the second part of the study, long-term clinical outcomes were compared between mepolizumab responders (MEPO HES) and subjects treated only with conventional agents (CONTROL HES). This is an important question given the relative expense of mepolizumab and lack of data describing the long-term outcomes of conventional therapy in patients with PDGFRA-negative HES. The limitations of this study include the relatively small number of subjects, differential disease severity between the comparator groups, and the retrospective nature of the analysis. However, HES is a rare disease, and a major strength of this study is the duration and detail of clinical follow-up data collected on a research protocol designed to study the natural history of HES.

At baseline, MEPO HES subjects had a longer duration of HES illness, had failed more therapies, and were less likely to be GC responsive, suggesting that they had more severe disease than CONTROL HES subjects. Despite this, MEPO HES subjects did not demonstrate greater rates of mortality, malignancy, or negative clinical outcomes (Table IV). Larger studies will be needed to confirm these findings. Whereas the number and rate of HES-related hospitalizations and disease flares were also similar between the CONTROL and MEPO HES groups, the rate of disease flares was significantly decreased in MEPO HES subjects controlled on mepolizumab alone as compared with the CONTROL HES group and with the MEPO HES group requiring any additional HES therapy (including GC). Rates of new-onset and worsening therapy-related comorbidities (eg, cataracts from long-term steroid usage, interferon-a-induced hypothyroidism) were not different. However, only the MEPO HES group demonstrated improvement in therapy-related comorbidities. Taken together, these data suggest that the ability to discontinue conventional HES medications is an important benefit of mepolizumab therapy with resultant improvement in numbers of HES disease flares and comorbidities.

The most appropriate dose of mepolizumab for HES treatment remains unknown. Although many subjects in our study could decrease the dose of mepolizumab and/or increase the dosing interval, 4 of 23 subjects required monthly mepolizumab at 750 mg IV to maintain disease control. In EGPA, early open-label studies using mepolizumab at 750 mg IV monthly led to remission in 80% to 100% of subjects24,25 in comparison with a 53% remission rate in the recent placebo-controlled multicenter trial using mepolizumab at 300 mg SC monthly,13 although this dose effect can be explained, at least partially, by different definitions of remission.

The current retrospective analysis of subjects on HES CUP confirms that mepolizumab is an effective and well-tolerated long-term therapy for GC-responsive HES and demonstrates that high-dose (750 mg IV) mepolizumab can be effective salvage therapy in patients with treatment-refractory, life-threatening HES. A multicenter phase 3 trial of mepolizumab (300 mg SC monthly) for severe GC-responsive HES is underway (NCT 02836496). Although data from HES CUP suggest that 300 mg SC monthly is likely to be effective in most of these subjects, optimal dosing in patients with GC-refractory disease requires further study. A better understanding of the disease mechanism in mepolizumab nonresponders is also needed to identify alternative therapies.

What is already known about this topic?

Mepolizumab treatment has been studied in glucocorticoid (GC)-sensitive hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) subjects and demonstrated a lasting GC-sparing effect.

What does this article add to our knowledge?

High-dose mepolizumab treatment can be effective in life-threatening, treatment-refractory HES. Predictors of response include clinical subtype, serum IL-5 level, and GC sensitivity. Compared with conventionally treated HES, mepolizumab-treated HES subjects require fewer additional HES medications and report improvement in morbidity.

How does this study impact current management guidelines?

Larger prospective studies are needed to confirm mepolizumab efficacy in this group of treatment-refractory HES subjects.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the NIH Clinical Center staff and the research subjects.

This project was funded in part by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH). This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, NIH, under Contract No. HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. The hypereosinophilic syndrome compassionate use study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (NCT00244686/GSK ID 104317).

Abbreviations used

- AEC

Absolute eosinophil count

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- CUP

Compassionate use program

- EGPA

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- GC

Glucocorticoid

- GSK

GlaxoSmithKline

- HES

Hypereosinophilic syndrome

- IV

Intravenous

- LHES

Lymphocytic variant HES

- MHES

Myeloid variant HES

- PDGFRA

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha

- SC

Subcutaneous

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: H. Ortega and J. Steinfeld are GlaxoSmithKline employees and shareholders. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Ogbogu PU, Bochner BS, Butterfield JH, Gleich GJ, Huss-Marp J, Kahn JE, et al. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: a multicenter, retrospective analysis of clinical characteristics and response to therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009; 124:1319–1325.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bochner BS, Book W, Busse WW, Butterfield J, Furuta GT, Gleich GJ, et al. Workshop report from the National Institutes of Health Taskforce on the Research Needs of Eosinophil-Associated Diseases (TREAD). J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;130:587–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garrett JK, Jameson SC, Thomson B, Collins MH, Wagoner LE, Freese DK, et al. Anti-interleukin-5 (mepolizumab) therapy for hypereosinophilic syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;113:115–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plötz S-G, Simon H-U, Darsow U, Simon D, Vassina E, Yousefi S, et al. Use of an anti-interleukin-5 antibody in the hypereosinophilic syndrome with eosinophilic dermatitis. N Engl J Med 2003;349:2334–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klion AD, Law MA, Noel P, Kim Y-J, Haverty TP, Nutman TB. Safety and efficacy of the monoclonal anti-interleukin-5 antibody SCH55700 in the treatment of patients with hypereosinophilic syndrome. Blood 2004;103:2939–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothenberg ME, Klion AD, Roufosse FE, Kahn JE, Weller PF, Simon H-U, et al. Treatment of patients with the hypereosinophilic syndrome with mepolizumab. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1215–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roufosse FE, Kahn J-E, Gleich GJ, Schwartz LB, Singh AD, Rosenwasser LJ, et al. Long-term safety of mepolizumab for the treatment of hypereosinophilic syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;131:461–467.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haldar P, Brightling CE, Hargadon B, Gupta S, Monteiro W, Sousa A, et al. Mepolizumab and exacerbations of refractory eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med 2009;360:973–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nair P, Pizzichini MMM, Kjarsgaard M, Inman MD, Efthimiadis A, Pizzichini E, et al. Mepolizumab for prednisone-dependent asthma with sputum eosinophilia. N Engl J Med 2009;360:985–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pavord ID, Korn S, Howarth P, Bleecker ER, Buhl R, Keene ON, et al. Mepolizumab for severe eosinophilic asthma (DREAM): a multicentre, doubleblind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2012;380:651–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ortega HG, Liu MC, Pavord ID, Brusselle GG, FitzGerald JM, Chetta A, et al. Mepolizumab treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pavord ID, Chanez P, Criner GJ, Kerstjens HAM, Korn S, Lugogo N, et al. Mepolizumab for eosinophilic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1613–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wechsler ME, Akuthota P, Jayne D, Khoury P, Klion A, Langford CA, et al. Mepolizumab or placebo for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1921–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duncan EA, Ortega H, Gleich G, Price R, Yancey S, Klion AD. Observational experience describing the use of mepolizumab in patients with hypereosinophilic syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191: A1365. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klion AD. How I treat hypereosinophilic syndromes. Blood 2015;126:1069–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khoury P, Abiodun AO, Holland-Thomas N, Fay MP, Klion AD. Hypereosinophilic syndrome subtype predicts responsiveness to glucocorticoids. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018;6:190–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hochberg Y, Tamhane AC. Multiple Comparison Procedures. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein ML, Collins MH, Villanueva JM, Kushner JP, Putnam PE, Buckmeier BK, et al. Anti-IL-5 (mepolizumab) therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006;118:1312–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roufosse F, de Lavareille A, Schandené L, Cogan E, Georgelas A, Wagner L, et al. Mepolizumab as a corticosteroid-sparing agent in lymphocytic variant hypereosinophilic syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010; 126:828–835.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khoury P, Desmond R, Pabon A, Holland-Thomas N, Ware JM, Arthur DC, et al. Clinical features predict responsiveness to imatinib in platelet-derived growth factor receptor-alpha-negative hypereosinophilic syndrome. Allergy 2016;71:803–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartemes KR, Iijima K, Kobayashi T, Kephart GM, McKenzie AN, Kita H. IL33-responsive lineage-CD25+ CD44(hi) lymphoid cells mediate innate type 2 immunity and allergic inflammation in the lungs. J Immunol 2012;188:1503–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khoury P, Makiya M, Klion AD. Clinical and biological markers in hypereosinophilic syndromes. Front Med (Lausanne) 2017;4:240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cogan E, Schandené L, Crusiaux A, Cochaux P, Velu T, Goldman M. Brief report: clonal proliferation of type 2 helper T cells in a man with the hypereosinophilic syndrome. N Engl J Med 1994;330:535–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moosig F, Gross WL, Herrmann K, Bremer JP, Hellmich B. Targeting interleukin-5 in refractory and relapsing Churg-Strauss syndrome. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:341–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim S, Marigowda G, Oren E, Israel E, Wechsler ME. Mepolizumab as a steroid-sparing treatment option in patients with Churg-Strauss syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;125:1336–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]