Abstract

The inverse association between smoking and educational attainment has been reported in cross-sectional studies. Temporality between smoking and education remains unclear. Our study examines the prospective association between high school cigarette and smoking post-secondary education enrollment. Data were collected from a nationally representative cohort of 10th graders who participated in the Next Generation Health Study (2010-2013). Ethnicity/race, urbanicity, parental education, depression symptoms, and family affluence were assessed at baseline. Self-reported 30-day smoking was assessed annually from 2010-2012. Post-secondary education enrollment was measured in 2013 and categorized as either not enrolled or enrolled in technical school, community college, or 4-year college/university. Multinomial logistic regression was used to evaluate the association between cigarette smoking duration and post-secondary education enrollment (N=1681). Participants who smoked 1, 2, or 3 years during high school had lower odds of attending a 4-year college (relative to a no enrollment) than non-smokers (adjusted OR: smoking 1 year=0.30, 2 years=0.28, 3 years=0.14). Similarly, participants who smoked for 2 or 3 years were less likely than non-smokers to enroll in community college (adjusted OR: 2 years=0.31, 3 years=0.40). These associations were independent of demographic and socioeconomic factors. There was a prospective association between high school smoking and the unlikelihood of enrollment in post-secondary education. If this represents a causal association, strategies to prevent/delay smoking onset and promote early cessation in adolescents may provide further health benefits by promoting higher educational attainment.

Keywords: post-secondary education, adolescent, high school, smoking, tobacco prevention

INTRODUCTION

Educational attainment is a social determinant of health, which is comprised of social factors proposed as “causes of the causes” for health condition [1,2], Higher educational attainment is associated with better health-related behaviors, more social support, positive mental health, and ultimately, longer life expectancy [2-5]. National surveillance data show that educational attainment is inversely associated with cigarette smoking among US adults. For example, data from the 2014 National Health Interview Survey revealed the prevalence of smoking among adults was 22.9% for less than high school education, 21.7% for high school diploma, 19.7% for some college education, 17.1% for associate degree, 7.9% for with undergraduate degree, and 5.4% for graduate degree [6]. Similarly, previous young adult studies also found that those enrolled in 4-year colleges had the lowest prevalence of current smoking, followed by those enrolled in 2-year colleges, while those who only completed high school had the highest prevalence of current smoking [7,8]3. These studies suggest that low educational attainment is a risk factor for health-related behaviors, specifically smoking [2,5].

Temporality between educational attainment and smoking is not clearly established, but there is evidence to suggest a bi-directional relationship. The association of smoking with post-secondary education enrollment may have long-term implications for educational attainment, such as health and social outcomes. For example, smoking may be adopted by adolescents as a maladaptive coping strategy for stress generated by poor academic performance, negative affect, or familial/social neglect [9,10]. This suggests that academic failure precedes tobacco use. On the other hand, there is limited relevant evidence that smoking is a strong predictor of educational underperformance [11,12,13,14].

Adolescent nicotine dependence may influence adolescents’ ability to concentrate when abstaining from smoking for a few hours, such as during standardized tests. Cross-sectional studies show that adolescents who smoke cigarettes performed significantly worse on standardized tests when compared with their non-smoking peers [15,16,17]. Moreover, smoking negatively affects other risky health behaviors, such as dietary habits [18, 19, 20], physical activity [20,21], alcohol use [16,21], and sleep [23,24] among smokers; these complex factors, solely or together as a cluster, may reduce adolescents’ ability to focus on learning. Therefore, poor academic performers who smoke cigarettes are more likely to not attend college than nonsmoking peers as well as those who receive high academic scores. Nonetheless, research regarding college enrollment and smoking is highly dominated by current college-enrolled students and to our knowledge, no studies to date have examined whether adolescent smoking predicts subsequent post-secondary education enrollment.

To expand our limited understanding of the role that smoking may have in directly shaping later educational outcomes, the current study assessed the association between cigarette smoking during high school and post-secondary education enrollment in a prospective cohort study of adolescents. We hypothesized that longer high school smoking history is inversely associated with post-secondary education enrollment. Specifically, we posited that adolescents who reported longer cigarette smoking duration in high school, compared to non-smokers, were less likely to advance into vocational/technical schools, two-year colleges, and four-year colleges after high school.

METHODS

Data source and sampling

The Next Generation Health Study is a longitudinal study that followed a nationally representative cohort of U.S. high school 10th grade students first assessed in 2009-2010. The study used a three-stage stratified sampling design. Primary sampling units comprised of school districts stratified by nine census divisions. Of the 137 high schools (public, private, and parochial) randomly chosen for the study, 80 high schools joined the study. Tenth grade classes in core subjects were randomly selected at each school for participation. Eligible students participated upon parental consent and student assent. Students provided consent for participation at the assessment following their 18th birthday. The study oversampled African American participants to provide adequate population estimates for ethnic and racial differences. Trained research staff administered a school-based, self-reported, voluntary, and confidential paper questionnaire during the 10th grade (baseline or T1, N=2524) [25]. Participants were surveyed annually via web-based assessments in 11th grade (T2, 2010-2011, N=2439), 12th grade (T3, 2011-2012, N=2407), and one year post-secondary education (T4, 2012-2013, N=2177). Most of the sample graduated from high school or obtained a GED at T4. For these analyses, 1681 students completed all four surveys from baseline to T4 and self-reported post-secondary enrollment status at T4. Students with missing information between baseline and T4 (N=451, 20.0%) as well as students who self-reported current high school attendance at T4 (N=42, 2.0%) were excluded from this current study. Of those excluded from analysis, students were more likely male (p<0.0001), of non-Hispanic Black descent (p<0.0001), and of lower family affluence (p<0.0001). In the overall analyses, there were significant interaction differences between smoking and post-secondary education enrollment for gender (p<0.01) and ethnicity/race (p<0.01). The institutional review board (IRB) of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development approved all procedures and study materials.

Measures

Cigarette smoking in past month.

At T1, T2, and T3, smoking behavior was assessed by asking adolescents, “On how many occasions (if any) have you smoked cigarettes in the last 30-days?” Students were asked to respond from (1) never (2) one or twice (3)3-5 times (4) 6-9 times (5) 10-19 times (6) 20-39 times (7) 40 times or more. A dichotomized variable was created with 0 for never and 1 representing smoking at least once in the past month. This question was derived from the Health Behavior in School-age Children questionnaire [26]. The cigarette smoking duration in high school corresponds to summative years of smoking participation, where 0 is no years, 1 is any one of the three years, 2 is two of the three years, and 3 is all three years during high school.

Post-secondary education enrollment.

Participants were asked at T4, “Are you currently attending school?” Responses included (1) No, I am not attending school; Yes, (2) high school (3) technical/vocational school (4) community college (5) college/university (6) graduate school or professional school. These analytic responses were categorized into: no enrollment (i.e., not attending school), technical/vocational school, community college, and 4-year college/university.

Covariates.

To account for differences between gender, ethnicity/race, parental education attainment, family affluence, negative affect (e.g. depressive symptoms), urbanicity, and school poverty index per school addresses, these baseline variables were included in the analyses as covariates. Parental education attainment was the highest education level reported for the participant’s mother or father, and collapsed into five categories: (1) less than high school, (2) high school diploma or GED, (3) some college, technical school, vocational school, or associate’s degree, (4) bachelor’s degree, and (5) graduate degree. Family affluence scale (FAS) was used to measure adolescents’ perception of family wealth or socioeconomic status through a sum composite of a four-item measure: (1) number of computers the family owns; (2) does the family own a car, van, or truck; (3) has own bedroom and (4) number of family vacations in the past year [27]. Answers included no=0; yes, one=l; and yes, two or more=2. The composite score was then categorized into three levels: low (score=0-2), medium (score=3-5), and high (score=6-9). Urbanicity is based on the National Center for Education Statistics’ locale code typology of metro-centric areas assigned to school districts [28]. Urbanicity was categorized as ‘urban’ (large central city, midsize city), ‘suburb’ (urban fringe of a large city, urban fridge of a mid-size city, large town, small town), and ‘rural’ (rural outside/inside mid-size city). School poverty index was determined by high school districts with a disproportionate number of families living in poverty. Ethnicity/race were classified into four categories: Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, and non-Hispanic Other (comprised of non-Hispanic Asian, American Indian, Alaskan Native, and Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander). Depressive symptoms were ascertained through the Modified Depression Scale [29] to assess levels of adolescent psychological distress. The 6-item scale asked how often students were sad, were grouchy/irritable or in a bad mood, felt hopeless about the future, felt like not eating or eating more than usual, slept a lot more or a lot less than usual, and had difficulty concentrating on school work in the past 30-days. Response options were never, seldom, sometimes, often and always (α=0.81).

Statistical Analysis

Prevalence of smoking duration by post-secondary education enrollment was assessed. Multinomial regression models were used to assess the association between smoking duration in high school at T1-3 and post-secondary education enrollment at T4, using not enrolled and 0 years of cigarette smoking as references. These multivariable models adjusted for gender, parental educational attainment, family affluence, urbanicity, depressive symptoms, school poverty index, and ethnicity/race. Analyses to fit proportional odds were attempted, but assumptions were violated, therefore smoking duration (number of years for which any past 30-day smoking was reported) was modeled as an ordinal categorical variable (with no smoking as the reference) to allow for a non-linear association. For each level of smoking (1, 2, or 3 years vs. 0 years), adjusted odds ratios represent the likelihood of being enrolled in technical/vocational school, community college, and 4-year college (relative to not being enrolled). This model is equivalent to a series of 3 logistic regression models, one for each category of post-secondary education (omitting the other education categories) relative to no enrollment. We performed stratified analysis by gender and by ethnicity/race to examine if the association between smoking duration and post-secondary education enrollment differed by these demographic variables. Aspects of the complex survey design, which include clustering and sampling weights, were considered in the analysis. Sampling weights were created for the cohort of participants that remained in the study from T1 to T4. In addition, school districts were clustered to account for the multilevel survey design. The significance level was set at 0.05.SAS, version 8.0 [30], specifically, PROC SURVEYMEANS, PROC SURVEYFREQ, PROC GLIMMIX, were used to account for the complex sampling design and differential probabilities of enrollment and participation across waves.

RESULTS

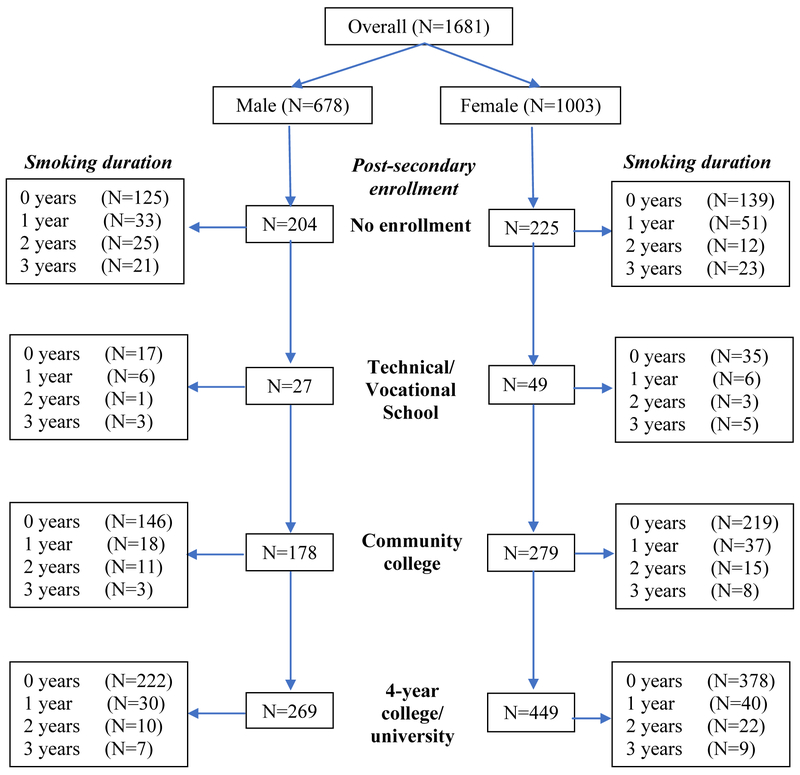

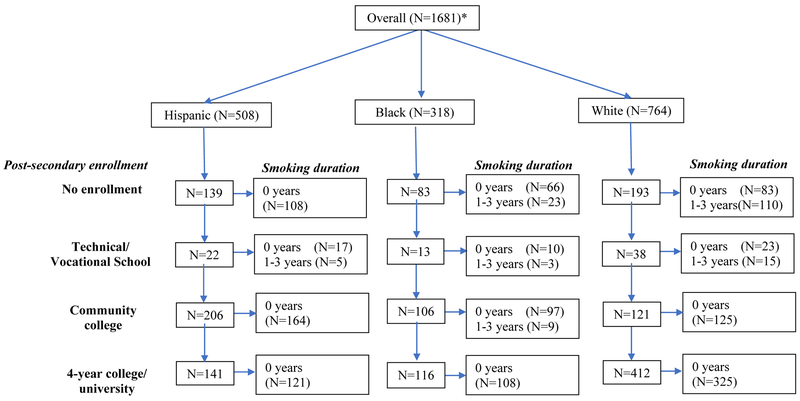

Table 1 summarizes unweighted and weighted demographic characteristics of the study sample (n=1681). Approximately one-fourth of students (24.7% unweighted) reported smoking cigarettes at least once during high school, where a fifth (19.8%) of the smokers reported past 30-day smoking all three years. Twenty-six percent of participants reported no post-secondary education enrollment at T4, while 43.2% enrolled in a 4-year college/university, and 21.7% and 5% enrolled in a community college and technical/vocational school, respectively. Unweighted and weighted smoking duration in the past 30-days during high school and post-secondary education enrollment overall are shown by gender (Table 2) and by ethnicity/race (Table 3), respectively. In addition, unweighted flow diagrams provide a detailed participant distribution of post-secondary enrollment and smoking duration by gender (Figure 1) and by ethnicity/race (Figure 2). About 40% of students with no post-secondary education enrollment smoked cigarettes during high school, compared to 32.6% of technical/vocational school, 21.1% of community college, and 15.4% of 4-year college/university. Similar trends were seen among both males and females. The levels of post-secondary education enrollment and the prevalence of smoking duration in high school were inversely related for both genders, although fewer females reported smoking during high school when compared to males. Because of the low prevalence of smoking in some ethnic/racial groups, we presented 0 year versus 1-3 years of smoking for ethnicity/race stratified analysis in Table 3. Data for non-Hispanic Other were not presented due to low overall sample size. Although most results show the prevalence of smoking was lower among Hispanics, non-Hispanic Blacks, and then non-Hispanic White, highest prevalence of smoking during high school were consistently observed among those with no post-secondary education enrollment.

Table 1.

Unweighted and weighted general characteristics at baseline (N=1681).

| Unweighted | Weighted | |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | % (95% CL) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 678 (40.3) | 39.6 (35.5-43.8) |

| Female | 1003 (59.7) | 60.4 (56.2-64.3) |

| Urbanicity | ||

| Urban | 590 (35.1) | 12.4 (0.0-25.8) |

| Suburban | 566 (33.7) | 48.2 (27.9-68.5) |

| Rural | 525 (31.2) | 39.4 (23.1-55.7) |

| Ethnicity/Race | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 764 (45.5) | 65.7 (55.1-77.4) |

| Hispanic | 508 (30.2) | 18.3 (9.2-27.5) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 318 (18.9) | 10.9 (5.5-15.8) |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 91 (5.4) | 4.7 (2.4-7.1) |

| Parental education attainment | ||

| ≤ High School | 215 (13.4) | 6.8 (2.0-11.5) |

| High School/GED | 378 (23.6) | 23.0 (18.8-27.2) |

| Some College/Technical/AA Degree | 594 (31.2) | 40.5 (36.9-45.1) |

| Bachelor Degree | 232 (14.5) | 16.6 (11.7-21.4) |

| Graduate Degree | 179 (11.2) | 13.2 (8.7-17.6) |

| Family Affluence Scale (FAS) score | ||

| Low | 487 (29.0) | 19.8 (13.9-25.8) |

| Medium | 804 (47.8) | 49.8 (46.5-53.0) |

| High | 390 (23.2) | 30.4 (24.0-36.8) |

| Smoking duration in HS (T1-3) | ||

| 0 years | 1282 (76.3) | 68.4 (62.0-74.8) |

| 1 year | 221 (13.2) | 14.8 (11.1-18.4) |

| 2 years | 99 (5.9) | 10.0 (6.4-13.6) |

| 3 years | 79 (4.7) | 6.8 (4.7-9.0) |

| Post-Secondary Education Enrollment (T4) | ||

| No post-secondary education enrollment | 429 (25.5) | 30.1 (25.9-34.2) |

| Technical /vocational school | 76 (4.5) | 5.0 (2.3-7.6) |

| Community college | 457 (21.7) | 21.7 (16.7-26.6) |

| 4-year college/university | 718 (43.2) | 43.2 (38.1-48.4) |

Table 2.

Unweighted and weighted sums and percentages of cigarette smoking duration in high school and type of post-secondary education enrollment, overall and by gender.

| Post-secondary education enrollment |

Smoking duration in HS |

Overall | Male | Female | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted N (%) |

Weighted % (95% CL) |

Unweighted N (%) |

Weighted % (95% CL) |

Unweighted N (%) |

Weighted % (95% CL) |

||

| No enrollment | 0 years | 264 (61.5) | 49.8 (36.3-63.3) | 125 (61.3) | 47.5 (31.3-63.7) | 139 (61.8) | 51.8 (38.3-65.4) |

| 1 year | 84 (19.6) | 22.0 (13.1-30.8) | 33 (16.2) | 19.8 (9.8-29.9) | 51 (22.7) | 23.9 (11.9-36.0) | |

| 2 years | 37 (8.6) | 15.4 (7.2-23.5) | 25 (12.2) | 18.6 (12.0-25.2) | 12 (5.3) | 12.4 (0.6-24.2) | |

| 3 years | 44 (10.3) | 12.9 (8.0-17.7) | 21 (10.3) | 14.0 (4.6-23.4) | 23 (10.2) | 11.8 (4.5-19.2) | |

|

Technical/vocational school |

|||||||

| 0 years | 52 (68.4) | 66.2 (52.3-80.1) | 17 (63.0) | 55.0 (25.0-84.9) | 35 (71.4) | 73.0 (26.5-89.4) | |

| 1 year | 12 (15.8) | 18.0 (7.2-28.9) | 6 (22.2) | 31.7 (8.2-54.5) | 6 (12.2) | 9.8 (0.0-24.4) | |

| 2 years | 4 (5.3) | 6.4 (0.0-13.0) | 1 (3.7) | 4.2 (2.0-6.3) | 3 (6.1) | 7.8 (0.0-17.7) | |

| 3 years | 8 (10.5) | 9.3 (4.3-14.4) | 3 (11.1) | 9.1 (0.1-18.1) | 5 (10.2) | 9.5 (1.4-17.5) | |

| Community college | |||||||

| 0 years | 365 (79.9) | 74.4 (64.6-84.2) | 146 (82.0) | 77.6 (64.3-90.9) | 219 (78.5) | 72.6 (61.7-83.6) | |

| 1 year | 55 (12.0) | 13.5 (8.0-19.0) | 18 (10.1) | 7.3 (3.2-11.3) | 37 (13.3) | 17.0 (8.7-25.2) | |

| 2 years | 26 (5.7) | 6.0 (2.3-9.6) | 11 (6.2) | 6.1 (0.5-11.6) | 15 (5.4) | 5.9 (0.8-11.0) | |

| 3 years | 11 (2.4) | 6.1 (0.7-11.6) | 3 (1.7) | 9.0 (0.0-23.3) | 8 (2.9) | 4.5 (0.8-8.2) | |

| 4-year college/university | |||||||

| 0 years | 601 (84.6) | 78.7 (70.5-86.8) | 222 (82.5) | 76.3 (64.2-88.5) | 378 (84.2) | 80.0 (71.2-88.7) | |

| 1 year | 70 (9.7) | 10.1 (6.5-13.6) | 30 (11.2) | 13.9 (8.4-19.4) | 40 (8.9) | 7.9 (3.9-11.9) | |

| 2 years | 32 (4.4) | 8.6 (3.3-14.0) | 10 (3.7) | 6.5 (0.4-12.6) | 22 (4.9) | 9.9 (2.8-16.9) | |

| 3 years | 16 (2.2) | 2.6 (0.9-4.4) | 7 (2.6) | 3.3 (0.0-6.7) | 9 (2.0) | 2.2 (0.2-4.3) | |

Table 3.

Weighted percentage of cigarette smoking duration in high school and type of post-secondary education enrollment by ethnicity/race.

| Post-secondary education enrollment |

Smoking duration in HS |

Hispanic | Non-Hispanic Black | Non-Hispanic White | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted N (%) |

Weighted % (95% CL) |

Unweighted N (%) |

Weighted % (95% CL) |

Unweighted N (%) |

Weighted % (95% CL) |

||

| No enrollment | 0 years | 108 (77.7) | 75.5 (56.4-94.5) | 66 (79.5) | 71.1 (44.4-97.9) | 83 (43.0) | 39.1 (26.7-51.4) |

| 1-3 years | 31 (22.3) | 24.5 (5.5-43.6) | 17 (20.1) | 28.8 (2.1-55.6) | 110 (57.0) | 61.9 (48.6-73.3) | |

|

Technical/vocational school |

0 years | 17 (77.3) | 64.2 (0.0-100.0) | 10 (76.9) | 82.8 (48.6-100.0) | 23 (60.5) | 62.9 (45.6-80.3) |

| 1-3 years | 5 (22.7) | 35.8 (0.0-100.0) | 3 (23.1) | 17.2 (0.0-51.3) | 15 (39.5) | 37.1 (19.7-54.4) | |

| Community college | 0 years | 164 (79.6) | 73.1 (44.6-100.0) | 97 (91.5) | 79.7 (50.0-100.0) | 86 (71.1) | 74.8 (66.0-83.5) |

| 1-3 years | 42 (20.4) | 26.9 (0.0-55.4) | 9 (8.5) | 20.3 (0.0-50.0) | 35 (28.9) | 25.2 (16.4-34.0) | |

| 4-year college/university | 0 years | 120 (85.8) | 90.3 (81.0-99.5) | 108 (93.1) | 94.9 (86.4-100.0) | 325 (78.9) | 73.9 (63.7-84.2) |

| 1-3 years | 20 (14.2) | 9.7 (0.5-19.0) | 8 (6.9) | 5.1 (0.0-13.6) | 88 (21.1) | 26.1 (15.8-36.3) | |

Note: NH-other not displayed due to small sample size.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants by gender (unweighted sample sizes) for smoking duration in high school and type of post-secondary education enrollment.

Figure 2.

Flow of participants by race/ethnicity (unweighted sample sizes) for smoking duration in high school and type of post-secondary education enrollment.

* Overall includes excluded ethnic group, Non-Hispanic Other (Asians, Alaskan Natives, & Native Hawaiian Pacific Islanders; N= 91)

The adjusted odds ratios between post-secondary education enrollment and cigarette smoking duration are described in Table 4, which presents the results of a multinomial logistic regression models in the full sample and separately for sex and ethnic/racial groups, with post-education enrollment at T4.

Table 4.

Weighted odds ratio for type of post-secondary education enrollment by cigarette smoking duration in high school, gender, and ethnicity/race.

| Smoking duration in HS | Technical/Vocational | Community College | 4-year College |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CL) | OR (95% CL) | OR (95% CL) | |

| Overall | |||

| 0 years | ref | ref | ref |

| 1 year | 0.81 (0.44-1.50) | 0.72 (0.49-1.05) | 0.32 (0.22-0.46) |

| 2 years | 0.43 (0.19-1.00) | 0.31 (0.18-0.53) | 0.32 (0.21-0.49) |

| 3 years | 1.21 (0.55-2.69) | 0.40 (0.22-0.72) | 0.16 (0.10-0.28) |

| Female | |||

| 0 years | ref | ref | ref |

| 1 year | 0.60 (0.26-1.38) | 0.64 (0.40-1.02) | 0.24 (0.15-0.39) |

| 2 years | 1.41 (0.50-4.00) | 0.49 (0.23-1.06) | 0.74 (0.39-1.41) |

| 3 years | 3.93 (1.42-10.86) | 0.41 (0.16-1.03) | 0.22 (0.11-0.43) |

| Male | |||

| 0 years | ref | ref | ref |

| 1 year | 0.94 (0.38-2.38) | 0.51 (0.27-0.98) | 0.45 (0.27-0.76) |

| 2 years | 0.24 (0.04-1.34) | 0.47 (0.23-0.97) | 0.15 (0.07-0.31) |

| 3 years | 0.79 (0.25-2.51) | 0.23 (0.09-0.58) | 0.15 (0.07-0.21) |

| Hispanic | |||

| 0 years | ref | ref | ref |

| 1-3 years | 0.85 (0.18-3.96) | 1.45 (0.64-3.27) | 0.59 (0.24-1.45) |

| Black | |||

| 0 years | ref | ref | ref |

| 1-3 years | 2.87 (0.34-23.98) | 0.70 (0.23-2.10) | 0.10 (0.02-0.63) |

| White | |||

| 0 years | ref | ref | ref |

| 1-3 years | 0.46 (0.26-0.82) | 0.31 (0.21-0.47) | 0.26 (0.19-0.35) |

NOTE: Bolded estimates are statistically significant (p<0.05). Overall analyses adjusted for gender, ethnicity/race, urbanicity, family affluence, parent education attainment, depressive symptoms, and school poverty index. Model reference is no post-secondary education enrollment

Adolescents who smoked during grades 10, 11, and 12 had 0.40 (95% CI= 0.22-0.72) and 0.16 (95% CI= 0.10-0.28) times odds of enrolling in a community college or 4-year college/university, respectively, than non-smoking adolescents. Similarly, students who reported 2-year smoking history were less likely to enroll in community college (AOR=0.31, 95% CI=0.18-53) and 4-year college/university (AOR=0.32, 95% CI=0.21-49) than those with no post-secondary education enrollment. In the stratified analysis, compared to non-smokers, male smokers were less likely to attend a community college (1 year smoker AOR=0.51, 95% CI=0.27-0.98; 2 year smoker AOR=0.47, 95% CI=0.23-0.97; 3 year smoker AOR=0.23, 95% CI=0.09-0.58), or a 4-year college/university (1 year smoker AOR=0.45, 95% CI=0.27-0.76; 2 year smoker AOR=0.15, 95% CI=0.07-0.31; 3 year smoker AOR=0.15, 95% CI=0.07-0.21) than no post-secondary enrollment education as years of high school smoking history increased. Among females, those who smoked 3-years were more likely to attend a technical/vocational school (AOR=3.93, 95% CI=1.42-10.86) or less likely to attend a 4-year college/university (AOR=0.22, 95% CI=0.11-0.43) versus females who did not smoke and no post-secondary education enrollment. Non-Hispanic Black participants who reported smoking during high school (versus those reported no smoking during high school) were less likely to attend a 4-year college/university than no enrollment (AOR=0.10, 95% CI=0.02-0.63). Among non-Hispanic Whites, high school smokers were less likely to enroll in any type of post-secondary education (1 year smoker AOR=0.46, 95% CI=0.26-0.82; 2 year smoker AOR=0.31, 95% CI=0.21-0.47; 3 year smoker AOR=0.26, 95% CI=0.19-0.35) than those with no enrollment when compared to non-smokers.

Multivariable analyses revealed that, compared to participants with no post-secondary education enrollment, students with higher family affluence and parental educational attainment were more likely enrolled in any type of post-secondary education (Supplemental Table). In addition, students who reported higher symptoms of depression, as well those who attended a high school district with a disproportionate number of families living in poverty were less likely to attend a 4-year college/university than no post-secondary education enrollment. Compared to non-Whites, Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks were more likely to attend technical/vocational schools than no post-secondary education enrollment; Hispanics were also more likely to attend community colleges than non-Hispanic Whites.

DISCUSSION

Previous longitudinal research suggests a strong inverse association between cigarette smoking history and academic achievement [12,13,14]. Using a nationally representative sample of adolescents, we found that positive high school smoking history was associated with lower odds of post-secondary education enrollment. Our findings extended those of previous adolescent studies which found that cigarette smoking during adolescence is adversely associated with enrolling into college [31,32].

Tobacco use remains to be a significant modifiable health behavior related to morbidity, mortality, and social factors among youth and adults [33]. Smoking is often established during adolescence and extends into adulthood, impacting various social and health outcomes over the lifespan. Our current study identifies adolescent smoking as a risk factor for not enrolling in post-secondary education for both genders and different race/ethnic groups. Identifying this temporal association of adolescent smoking on college enrollment has an impact on further highlighting social determinants and health disparities. It is important to address the effect of educational attainment and health among adolescents to account for potential adulthood outcome differences in employment, (family) income status, and marital status. As seen cross-sectionally and longitudinally, educational achievement is strongly correlated with higher income, which is associated with better job opportunities and access to resources, and in the long term, better health outcomes [34,35].

Our findings posit that smoking could be an important marker for a range of factors implicated with negative outcomes during adolescence such as academic underperformance, associating with deviant peers, and/or bad behavior, which collectively may lead to no post-secondary education enrollment after high school graduation.

Among educational researchers, common predictors of college enrollment are achievement benchmarks or academic performance indicators such as high school GPA, passing exit/entrance exams, and participation in college preparatory programs (e.g. advance placement courses, summer bridge programs) [36]. Academic performance (often ascertained through GPA, grades, standardized test scores, or grade retention) is consistently reported by behavioral researchers as inversely related to smoking, where students who perform academically well were less likely to smoke and non-smoking students were more likely to perform academically better than their smoking counterparts. [12-15,37]. Furthermore, some researchers suggest smoking as a contributing cause for academic performance decline due to cognitive impairment [38]. In a study by Jacobsen and colleagues, poor performance on verbal and working memory were strongly associated among regular smoking adolescents seeking cessation treatment compared to non-smokers [39]. Poor academic performance, despite differences in measurement or development, may contribute to both, smoking behavior and college enrollment.

Furthermore, various adolescent behavior theories, such as problem behavior theory, suggest that negative school-related behavior (e.g. skipping class, bad conduct, rebelliousness, etc.) is related to delinquency, substance use experimentation, and social norms [40]. Therefore, low academic achievement and cigarette smoking may be mutually reinforcing each other [41,42]. In fact, a previous longitudinal study conducted in Finland found evidence for a reciprocal relationship between smoking and academic performance, and the effect of this shared association on subsequent educational attainment [12]. The study showed that between the ages of 12 and 17, smoking predicted school performance, and school performance predicted subsequent smoking behavior. In turn, adolescent smoking was directly associated with young adult educational attainment, and indirectly influencing adolescent academic performance and potential future income. These various mechanisms could be operating in our study sample, although we did not collect information on academic performance to test this hypothesis.

Smoking in high school may represent experimental rebellious behavior, while consistent persistent smoking may represent a commitment to unconventional behavior, addiction, or association with deviant peers. Various studies suggest that individuals who smoke and perform poor academically are more likely to affiliate with peers who endorse smoking [37,43,44]. Previous research using data from the Monitoring the Future study found that participants’ smoking status at age 14 was positively associated with peer misbehaviors, and negatively associated with participants’ own academic achievement and college plan [37]. Perhaps adolescent smoking fosters and maintains a social group that is supportive of smoking and has low motivation for studying or attending college.

These findings are to be interpreted with some limitations. These results cannot be generalized to adolescents who did not attend a public or private high school (i.e. homeschooled) and may have left high school prior to 10th grade. Past 30-day smoking may not fully capture irregular smoking behavior between annual assessments; however, it provides a snapshot of regular smoking behavior over time. Although information on academic performance was not collected, we believe that educational attainment is a subsequent outcome of academic performance. To ensure the consistency of information, only individuals who participated in all 4 waves were included in the study. The data were weighted to account for attrition and minimize selection bias. The nationally representative sample of adolescents in our study and longitudinal design are strengths of our study.

Adolescence is a complex developmental stage where multiple system factors (e.g. psychosocial, family, neighborhood, school, etc.) co-exist with and/or influence smoking behavior. For example, growing research implicates various factors of adolescent health, such as smoking, as causal pathways where low socioeconomic status effects academic and educational outcomes [36]. Disentangling the potential causal effects of smoking from other potential predictors (e.g. biological determinants, school environment, neighborhood characteristics, other psychosocial factors, etc.) and compound risk behaviors (e.g. diet, physical activity, sleep, drug use) that may be associated with smoking to impact post-secondary education enrollment goes beyond the scope of this study. Future mediation studies or quasi-experimental designs may facilitate a better understanding of smoking behavior and other adolescent determinants on post-secondary education enrollment. For example, future research may warrant a further understanding of potential moderators and mediators associated with smoking and post-secondary education enrollment that were not explored or accounted for in this study.

CONCLUSION

While the direct effects of smoking on health is well-documented, the potential influence of adolescent smoking on social determinants of health is less known. Our results suggest that adolescent smoking is a relevant predictor of educational attainment, where a high school smoking history predicts a lower likelihood of an adolescent subsequently enrolling into post-secondary education. Although causality and mechanisms underlying these relationships are undetermined, smoking during high school may be a risk factor for shortened educational career. If it is, deferring and/or delaying smoking onset as well as promoting early cessation in adolescence may provide health benefits beyond those that are associated with tobacco itself, but more broadly through health benefits associated with through higher educational attainment. This may be interesting to policy, educators, and researchers as we identify adolescents most vulnerable to health and social disparities and the most in need of higher education bridge programs. The findings of this study add to further promote the Healthy People 2020 objective AH-5, “increase educational achievement of adolescent and young people” [45], as we aim to address the potential impact of adolescent smoking on educational attainment, and thusly advocating for equitable academic success and narrowing health disparities over the lifespan.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

High school smoking duration is inversely linked to prospective college enrollment.

High school smoking may contribute negatively to educational attainment.

Deferring/mitigating smoking onset will provide further long-term health benefits.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors were supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (Sabado and Choi) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Haynie, Gilman, and Simons-Morton). The NEXT Generation Health Study is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Contract # HHSN275201200001I), and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) of the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marmot M Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 2005; 365(9464):1099–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep 2014;129; 19–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilman SE T Martin L, Kawachi I, Kubzansky LD, Loucks EB, Rudd RE, et al. Education and smoking: A causal association? Inter J Epidemiol 2006; 37(3): 615–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loucks EB, Gilman SE, Howe CJ, Kawachi I, Kubzansky LD, Rudd RE, et al. Education and coronary heart disease risk: potential mechanisms such as literacy, perceived constraints, and depressive symptoms. Health Educ Behav 2015;42(3):370–9. DOI: 10.1177/1090198114560020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braveman PA, Kumanyika S, Fielding J, et al. Health disparities and health equity: the issue is justice. Am J of Public Health 2011; 101: S149–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamal A, Homa DM, O’Connor E, et al. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015; 64:1233–1240. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6444a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berg CJ, Ling PM, Hayes RB, et al. Smoking frequency among current college student smokers: distinguishing characteristics and factors related to readiness to quit smoking. Health Edu Res 2012;27(l);141–50. DOI: 10.1093/her/cyrl06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solberg LI, Asche SE, Boyle R, et al. Smoking and cessation behaviors among young adults of various educational backgrounds. Am J Public Health 2007; 97(8):1421–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suhrcke M, de Paz Nieves C. The impact of health and health behaviours on educational outcomes in high-income countries: a review of the evidence. World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGee R, Williams S, Nada-Raja S, Olsson CA. Tobacco smoking in adolescence predicts maladaptive coping styles in adulthood. Nicotine Tob Res 2013:15(12);1971–7. DOI: 10.1093/ntr/ntt081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rose JE, Ananda S, Jarvik ME. Cigarette smoking during anxiety-provoking and monotonous tasks. Addict Behav 1983; 8(4):353–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Latvala A, Rose RJ, Pulkkinen L, Dick DM, Korhonen T, Kaprio J. Drinking, smoking, and educational achievement: Cross-lagged associations from adolescence to adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014; 137:106–113. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ. High-risk behaviors associated with early smoking: results from a 5-year follow-up. J Adolesc Health 2001; 28(6):465–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley BJ, Greene AC. Do health and education agencies in the United States share responsibility for academic achievement and health? A review of 25 years of evidence about the relationship of adolescents’ academic achievement and health behaviors. J Adolesc Health 2013; 52:523–532. DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox RG, Zhang L, Johnson WD, Bender DR. Academic performance and substance use: findings from a state survey of public high school students. J Sch Health 2007;77(3):109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeynes WH. The relationship between the consumption of various drugs by adolescents and their academic achievement. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 2002;28(l):15–35. DOI: 10.1081/ADA-120001279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diego MA, Field TM, Sanders CE. Academic performance, popularity, and depression predict adolescent substance use. Adolescence 2003;38(149):35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dallongeville J, Marecaux N, Fruchart JC, Amouyel P. Cigarette smoking is associated with unhealthy patterns of nutrient intake: a meta-analysis. J of nutrition 1998; 128(9): 1450–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baer Wilson D, Nietert PJ. Patterns of fruit, vegetable, and milk consumption among smoking and nonsmoking female teens. Am J Prev Med 2002;22(4):240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson DB, Smith BN, Speizer IS, Bean MK, Mitchell KS, Uguy LS, et al. Differences in food intake and exercise by smoking status in adolescents. Prev Med 2005;40(6):872–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paavola M, Vartiainen E, Haukkala A. Smoking, alcohol use, and physical activity: a 13-year longitudinal study ranging from adolescence into adulthood. J Adolesc Health 2004;35(3):238–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crosnoe R The connection between academic failure and adolescent drinking in secondary school. Soc Edu 2006;79(1), 44–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bellatorre A, Cho T, Lewin D, Haynie D, Simons-Morton B. Relationships between smoking and sleep problems in Black and White adolescents. Sleep 2016; 40(l):zsw031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shochat T, Cohen-Zion M, Tzischinsky O. Functional consequences of inadequate sleep in adolescents: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev 2014; 18(l):75–87. DOI: 10.1016/j.smrv.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conway KP, Vullo GC, Nichter B, et al. Prevalence and patterns of polysubstance use in a nationally representative sample of 10th graders in the United States. J Adolesc Health 2013; 52(6): 716–723. DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Currie CE, Elton RA, Todd J, Platt S. Indicators of socioeconomic status for adolescents: the WHO Health Behaviour in School-aged Children Survey. Health Edu Res 1997;12(3):385–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boyce W, Torsheim T, Currie C, Zambon A. The family affluence scale as a measure of national wealth: validation of an adolescent self-report measure. Soc Indic Res 2006; 78:473–487. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Provasnik S, KewalRamani A, Coleman MM, et al. Status of Education in Rural America. NCES 2007–040. National Center for Education Statistics. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dahlberg LL, Toal SB, Swahn MH, Behrens CB. Measuring violence-related attitudes, behaviors, and influences among youths: A compendium of assessment tools. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.SAS 9.4. SAS institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chassin L, Presson CC, Pitts SC, Sherman SJ. The natural history of cigarette smoking from adolescence to adulthood in a midwestern community sample: multiple trajectories and their psychosocial correlates. Health Psychol 2000; 19(3):223–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cook PJ, Hutchinson R Smoke signals: adolescent smoking and school continuation. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance – United States, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ 2016; 62:1–174. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6506a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gan L, Gong G. Estimating interdependence between health and education in a dynamic model. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Basch CE. Healthier students are better learners: A missing link in school reforms to close the achievement gap. J Sch Health 2011;81(10):593–8. DOI: 10.1111/j.l746-1561.2011.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dymnicki A, Sambolt M, Kidron Y. Improving college and career readiness by incorporating social and emotional learning. College and Career Readiness and Success Center 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bryant AL, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. How academic achievement, attitudes, and behaviors relate to the course of substance use during adolescence: A 6-year, multiwave national longitudinal study. J Res Adolesc 2003;13(3):361–97. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Byrd RS, Weitzman ML. Predictors of early grade retention among children in the United States. Pediatr 1994;93(3):481–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacobsen LK, Krystal JH, Mencl WE, Westerveld M, Frost SJ, Pugh KR. Effects of smoking and smoking abstinence on cognition in adolescent tobacco smokers. Biol Psychiatry 2005;57(l):56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. New York, NY: Academic Press, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allison KR. Academic stream and tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use among Ontario high school students. Int J Addict 1992;27(5):561–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henry KL, Muth6én B. Multilevel latent class analysis: An application of adolescent smoking typologies with individual and contextual predictors. Struct Equ Modeling 2010;17(2):193–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tucker JS, Martinez JF, Ellickson PL, Edelen MO. Temporal associations of cigarette smoking with social influences, academic performance, and delinquency: a four-wave longitudinal study from ages 13–23. Psychol Addict Behav 2008; 22(1):1–11. DOI: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brook JS, Balka EB, Rosen Z, Brook DW, Adams R. Tobacco use in adolescence: Longitudinal links to later problem behavior among African American and Puerto Rican urban young adults. J Genet Psychol 2005;166(2):133–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Healthy People 2020. https://www.healthypeople.gov. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [cited October 1 2016]. Available from: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/Adolescent-Health/objectives [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.