Abstract

Objective:

To analyze trends in the incidence, in-hospital management, and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) complicating pregnancy and the puerperium in the United States.

Patients and Methods:

Women age 18 years or older hospitalized during pregnancy and the puerperium were identified from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database from January 1st 2002 and December 31st 2014. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis and procedure codes were used to identify AMI during pregnancy-related admissions.

Results:

Overall, 55,402,290 pregnancy-related hospitalizations were identified. A total of 4,471 AMI (8.1 per 100,000 hospitalizations, 95% CI 7.5 – 8.6) occurred, with 20.6% of AMI identified in the antepartum period, 23.7% during labor and delivery, and 53.5% in the post-partum period. ST-segment elevation MI occurred in 42.4% of cases and non-ST-segment elevation MI occurred in 57.6%. Among patients with pregnancy-related AMI, 53.1% underwent invasive management and 25.1% underwent coronary revascularization. In-hospital mortality was significantly higher for patients with versus without AMI during pregnancy (adjusted OR 39.9 95% CI 23.3 – 68.4). The rate of AMI during pregnancy and the puerperium increased over time (adjusted OR 1.25 [for 2014 versus 2002], 95% CI 1.02 – 1.52).

Conclusion:

In patients hospitalized during pregnancy or the puerperium, AMI occurred in one of every 12,400 hospitalizations and rates of AMI increased over time. Maternal mortality rates were high. Additional research on the prevention and optimal management of AMI in pregnancy is necessary.

Keywords: Mortality, Myocardial Infarction, Outcomes, Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Peripartum, Pregnancy, Puerperium, Revascularization

Introduction:

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) during pregnancy is an uncommon but potentially devastating complication of the gravid state. AMI occurs during pregnancy with an incidence of approximately 3–10 cases per 100,000 deliveries,1–4 and is associated with 5 to 7% maternal case fatality with grave risks to the developing fetus.2,3 Hormonal and hemodynamic changes to the cardiovascular system and the hypercoagulable state of pregnancy in part account for the increased risk of AMI during pregnancy, which occurs with a frequency approximately 3–4 fold higher than for non-pregnant women of childbearing age.5 In addition, prior population-based studies demonstrate maternal age, tobacco use, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and thrombophilia are independent risk factors associated with AMI during pregnancy.2, 3 Investigation of AMI during pregnancy or the puerperium has been particularly challenging due to low incidence of events and heterogeneous clinical presentations. Consequently, recent epidemiology and data on the contemporary approaches to management of AMI in pregnancy are limited. We analyzed hospital admissions from a large national database to evaluate trends in the incidence, inhospital management, and outcomes of AMI complicating pregnancy and/or the puerperium in the United States.

Methods:

Data were obtained from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database from 2002 to 2014. The NIS is the largest publically available all-payer database and contains discharge-level administrative data on inpatient diagnoses and procedures from a 20% percent stratified sample of United States (U.S.) hospitals until 2012 and a 20% stratified sample of discharges among all U.S. hospitals thereafter. Sampling weights were applied to discharge records to generate national estimates for the U.S.6

Women age >18 years who were hospitalized during pregnancy and the puerperium were identified with the use of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis and procedure codes for labor and delivery, as well as ICD-9 diagnosis codes for antepartum and postpartum conditions. The ICD-9 codes used to identify pregnancy-related admissions are detailed in the Supplemental Table 1. AMI was identified using ICD-9 diagnosis codes for non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) (410.71) and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) (410.01 to 410.61, 410.81, and 410.91) in any position. Among patients with AMI, coronary artery dissection was defined by ICD-9 diagnosis code 414.12 and stress (Takotsubo) cardiomyopathy was identified by ICD-9 diagnosis code 429.83.

In-Hospital Management and Outcomes

Invasive management of AMI was defined by ICD-9 and CCS procedure codes for invasive coronary angiography, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) during inpatient hospitalization. Among patients who underwent PCI, procedure codes for bare-metal stent (BMS) (ICD-9 procedure code 36.06) and drug-eluting stent (DES) placement (ICD-9 procedure code 36.07) were identified. Intravascular ultrasound use was also identified (ICD-9 procedure code 00.24). Patients who did not have these invasive procedures coded were considered to have been managed conservatively. The primary outcome was in-hospital all-cause mortality.

Statistical Methodology

Categorical variables were reported as percentages and compared by Rao Scott Chi-square tests. Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard error (SER). The comparisons were made using PROC SURVEYREG procedure for continuous variables and PROC SURVEYFREQ for category variables to incorporate the complex survey design. Testing of trends over time were performed using the Cochran-Armitage test. Multivariable logistic regression models with patient demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, and comorbidities as covariates were used to estimate adjusted odds of AMI. Models included age, race/ethnicity, obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, tobacco use, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, prior coronary revascularization (with either PCI or CABG), known heart failure, history of atrial fibrillation, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, anemia, and malignancy as covariates for adjustment. Multivariable logistic regression models to estimate the adjusted odds of invasive management in patients with MI also included the diagnosis of STEMI, cardiogenic shock, and hospital characteristics as covariates. Sampling weights were applied to determine national incidence estimates in all analyses, according to HCUP guidance.6 Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and SPSS 22 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY). Two-sided P-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. The NIS is a publicly available, deidentified dataset and the study was exempt from institutional board review.

Patient Involvement

Patients were not involved in developing the research question, study outcome measures, study design, or conduct of the study. No patients provided input into the data analysis or interpretation of the results. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants. No patients served as authors or contributors to this work.

Results:

Overall, 55,402,290 hospitalizations during pregnancy or the puerperium were identified among women in the United States age >18 years (an average of 4,261,715 hospitalizations per year) between 2002 and 2014. A total of 4,164,077 hospitalizations (7.5%) occurred in the antepartum period, 49,829,753 hospitalizations (89.9%) for labor and delivery, and 1,238,900 hospitalizations (2.2%) occurred in the post-partum period. The timing of the hospitalization with respect to the pregnancy was either unspecified or could not be determined in the remaining 169,560 cases (0.3%).

A total of 4,471 AMI (8.1 per 100,000 hospitalizations in pregnancy, 95% CI 7.5 – 8.6) occurred during the study period. Of these, 922 AMI (22.1 per 100,000 hospitalizations, 95% CI 19.0 – 25.3; 20.6% of AMI) were identified in the antepartum period, 1,061 AMI (2.1 per 100,000 hospitalizations, 95% CI 1.8 – 2.4; 23.7% of AMI) occurred during a hospitalization for labor and delivery, and 2,390 AMI (192.9 per 100,000 hospitalizations, 95% CI 173.8 – 212.0; 53.5% of AMI) occurred in the postpartum period. The timing of AMI with respect to the pregnancy could not be determined in the remaining 98 cases (2.2% of AMI). After multivariable adjustment for demographics and clinical covariates, the odds of AMI were significantly higher in patients hospitalized during the antepartum (aOR 9.25, 95% CI 7.52 – 11.38) and postpartum (aOR 44.40, 95% CI 36.49 – 54.03) periods than those hospitalized for labor and delivery. Among patients hospitalized for labor and delivery, Cesarean sections were associated with higher frequency of AMI than vaginal deliveries (4.8 [95% CI 4.1 – 5.6] vs. 0.86 [95% CI 0.70 – 1.0] AMI per 100,000 hospitalizations for labor and delivery).

Among patients with AMI, STEMI occurred in 1,895 (42.4%) cases and NSTEMI occurred in 2,576 (57.6%) cases. Cardiogenic shock occurred in 290 cases of AMI (6.5%). Coronary dissection was identified in 647 cases (14.5%) of AMI overall, occurring in 23.1% of STEMI and 8.2% of NSTEMI, and in 24.6% of all patients undergoing invasive management. Coronary dissection was diagnosed in 23.1% of AMI in the postpartum period, 2.7% of AMI associated with labor and delivery, and 7.2% of AMI in the antepartum period. Takotsubo syndrome was identified in 83 cases of AMI (2.9%) from 2007 to 2014, the years for which the ICD-9 diagnosis code was available.

Baseline characteristics of patients with and without AMI complicating pregnancy or the puerperium are shown in Table 1. Women with pregnancy-related MI were older than those without AMI (mean age 33.1 vs. 28.0 years old, P<.001) and were more likely to have cardiovascular comorbidities (Table 1). The incidence of AMI per 100,000 hospitalizations during pregnancy or the puerperium increased significantly with maternal age (Figure 1, Table 2). Among patients with advanced maternal age, defined as age > 35 years, 23.3 (95% CI 21.1 – 25.6) AMI occurred per 100,000 hospitalizations in pregnancy. In a multivariable analysis, older maternal age, black race, tobacco, drug use, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, prior coronary revascularization, known heart failure, history of atrial fibrillation, anemia, and malignancy were independently associated with AMI during pregnancy or the puerperium (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with and without AMI complicating pregnancy and/or the puerperium

| Variable | All Hospitalizations during Pregnancy / Puerperium (n=5 5,402,2 90) |

AMI (n=4,471) |

No AMI (n=55,397,819) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years [mean (SER of the mean)] | 28.00 (0.07) | 33.11 (0.20) | 28.00 (0.07) | <0.001 |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| White non-Hispanic | 23588621 (42.6) | 1703 (38.1) | 23586918 (42.6) | |

| Black non-Hispanic | 6435508 (11.6) | 992 (22.2) | 6434516 (11.6) | |

| Hispanic | 10269415 (18.5) | 564 (12.6) | 10268851 (18.5) | |

| Others | 4798295 (8.7) | 364 (8.1) | 4797931 (8.7) | |

| Unknown | 10310450 (18.6) | 849 (19) | 10309602 (18.6) | |

| Obesity | 1724958 (3.1) | 421 (9.4) | 1724537 (3.1) | <0.001 |

| Obstructive Sleep Apnea | 37243 (0.1) | 62 (1.4) | 37181 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Tobacco Use | 1451408 (2.6) | 631 (14.1) | 1450777 (2.6) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol Abuse | 90067 (0.2) | 53 (1.2) | 90014 (0.2) | <0.001 |

| Drug Abuse | 879139 (1.6) | 314 (7.1) | 878825 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 4626294 (8.4) | 1458 (32.6) | 4624836 (8.3) | <0.001 |

| Gestational Hypertension | 2119699 (3.8) | 397 (8.9) | 2119302 (3.8) | <0.001 |

| Preeclampsia / Eclampsia | 2261361 (4.1) | 475 (10.6) | 2260886 (4.1) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 60420 (0.1) | 559 (12.5) | 59861 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 751824 (1.4) | 479 (10.7) | 751345 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| Gestational Diabetes Mellitus | 676874 (1.2) | 268 (6.0) | 676606 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease* | 23105 (0.1) | 69 (2.8) | 23036 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 16279 (0.03) | 1474 (33) | 14805 (0.03) | <0.001 |

| Prior Coronary Revascularization | 3723 (0.007) | 85 (1.9) | 3638 (0.007) | <0.001 |

| Percutaneous Coronary Intervention | 2569 (0.005) | 68 (1.5) | 2501 (0.005) | <0.001 |

| Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting | 1236 (0.002) | 22 (0.5) | 1214 (0.002) | <0.001 |

| History of TIA/Stroke* | 17793 (0.1) | 24 (1) | 17769 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Known Heart Failure | 60714 (0.1) | 853 (19.2) | 59861 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| History of Atrial Fibrillation | 16960 (0.03) | 105 (2.3) | 16855 (0.03) | <0.001 |

| Anemia | 5364769 (9.7) | 1186 (26.5) | 5363583 (9.7) | <0.001 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 47437 (0.1) | 15 (0.3) | 47422 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | 71523 (0.1) | 25 (0.6) | 71499 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Malignancy | 31155 (0.1) | 25 (0.6) | 31130 (0.1) | <0.001 |

Comorbidity data available from 2008–2014

Figure 1.

Frequency of AMI per 100,000 hospitalizations for any-pregnancy related hospitalization, or for labor and/or delivery, by age group.

Table 2.

Associations between clinical covariates and AMI during pregnancy and the puerperium period in multivariable analyses.

| Variable | Adjusted Odds Ratio for AMI |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–24 | Reference |

| 25–29 | 1.96(1.51 – 2.54) |

| 30–34 | 3.66(2.87 – 4.67) |

| 35–39 | 5.81 (4.58 – 7.37) |

| 40–44 | 10.30(7.42 – 14.29) |

| 45+ | 11.49(6.30 – 20.95) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White non-Hispanic | Reference |

| Black non-Hispanic | 1.46(1.15 – 1.85) |

| Hispanic | 0.95(0.76 – 1.19) |

| Others | 1.06(0.783 – 1.43) |

| Unknown | 1.23(1.028 – 1.47) |

| Obesity | 0.96(0.761 – 1.20) |

| Obstructive Sleep Apnea | 0.96(0.461 – 2.00) |

| Tobacco Use | 3.41 (2.74 – 4.25) |

| Alcohol Abuse | 1.26(0.59 – 2.68) |

| Drug Abuse | 2.73(1.99 – 3.74) |

| Hypertension | 2.46(2.04 – 2.97) |

| Dyslipidemia | 13.11 (8.78 – 19.59) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 1.89(1.38 – 2.60) |

| Prior Coronary Re vas cul arizati on | 6.38(2.56 – 15.90) |

| Known Heart Failure | 33.65(24.67 – 45.90) |

| History of Atrial Fibrillation | 5.67(2.75 – 11.70) |

| Anemia | 2.32(1.96 – 2.74) |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 0.90(0.17 – 4.74) |

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | 1.63(0.65 – 4.13) |

| Malignancy | 4.40(1.45 – 13.34) |

The proportion of patients with AMI was highest among patients with any preexisting coronary artery disease (CAD) risk factors (tobacco use, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, or renal disease) in comparison to patients without risk factors (66.1 [95% CI 59.4 – 72.7] vs. 5.2 [95% CI 4.7 – 5.7] AMI per 100,000 hospitalizations in pregnancy), although 61% of the AMI occurred in patients without established CAD risk factors.

Pregnancy-associated medical comorbidities were also associated with an increased frequency of AMI. Women with gestational diabetes mellitus were more likely to have AMI in comparison to women without a diagnosis of gestational diabetes (39.6 [95% CI 28.4 – 50.9] versus 7.7 [95% CI 7.1 – 8.2] AMI per 100,000 hospitalizations in pregnancy, P<.001). Similarly, AMI was more likely to occur in women with preeclampsia than those without a diagnosis of pre-eclampsia (21.0 [95% CI 16.9 – 25.2] vs.7.5 [95% CI 7.0 – 8.1] AMI per 100,000 hospitalizations in pregnancy, P<.001).

Management of AMI in Pregnancy

Among patients with AMI during a pregnancy-related hospitalization, 2,373 (53.1%) underwent invasive management. Patients who underwent invasive management were slightly older, more likely to use tobacco, have dyslipidemia and coronary artery disease, and less likely to have kidney disease or anemia (Table 3). Predictors of an invasive approach to AMI during pregnancy after multivariable adjustment are shown inTable 4. Patients were more likely to undergo invasive management of AMI in the postpartum period (69.8%, n=1,669) in comparison to the antepartum period (versus 42.7%, n=394, P<.001) or hospitalizations for labor and delivery (versus 24.2%, n=257, P<.001). Patients with STEMI were more likely to undergo invasive management than those with NSTEMI (64.5% vs. 44.6%, P<.001). Thrombolysis was performed in 0.8% of cases.

Table 3.

Characteristics of patients undergoing invasive versus conservative management of AMI complicating pregnancy and/or the puerperium

| Variable | All AMI (n=4,471) |

Invasive (n=2,373) |

Conservative (n=2,098) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years [mean (SER of the mean)] | 33.11 (0.20) | 33.98 (0.26) | 32.13 (0.29) | <0.001 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.03 | |||

| White non-Hispanic | 1703 (38.1%) | 937 (39.5%) | 766 (36.5%) | |

| Black non-Hispanic | 992 (22.2%) | 533(22.5%) | 459 (21.9%) | |

| Hispanic | 564 (12.6%) | 229 (9.6%) | 335 (16%) | |

| Others | 364 (8.1%) | 207 (8.7%) | 157 (7.5%) | |

| Unknown | 849 (19%) | 468 (19.7%) | 381 (18.2%) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Obesity | 421 (9.4%) | 186 (7.8%) | 236 (11.2%) | 0.07 |

| Obstructive Sleep Apnea | 62 (1.4%) | 18 (0.8%) | 44 (2.1%) | 0.08 |

| Tobacco Use | 631 (14.1%) | 430 (18.1%) | 200 (9.5%) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol Abuse | 53 (1.2%) | 29 (1.2%) | 24 (1.2%) | 0.90 |

| Drug Abuse | 314 (7.1%) | 95 (4%) | 220 (10.6%) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1458 (32.6%) | 753 (31.7%) | 705 (33.6%) | 0.50 |

| Gestational Hypertension | 397 (8.9%) | 245 (10.3%) | 152 (7.2%) | <0.001 |

| Preeclampsia / Eclampsia | 475 (10.6%) | 133 (5.6%) | 342 (16.3%) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 559 (12.5%) | 472 (19.9%) | 88 (4.2%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 479 (10.7%) | 221 (9.3%) | 258 (12.3%) | 0.14 |

| Gestational Diabetes Mellitus | 268 (6.0%) | 99 (4.2%) | 169(8.1%) | <0.001 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease* | 69 (2.8%) | 15(1.1%) | 54 (5%) | 0.002 |

| Prior Coronary Revascularization | 85 (1.9%) | 32 (1.3%) | 53 (2.5%) | 0.16 |

| PCI | 68 (1.5%) | 20 (0.8%) | 48 (2.3%) | 0.04 |

| CABG | 22 (0.5%) | 12 (0.5%) | 10 (0.5%) | 0.95 |

| History of TTA/Stroke* | 24 (1%) | 14 (1%) | 10 (0.9%) | 0.66 |

| Known Heart Failure | 853 (19.2%) | 423 (17.9%) | 430 (20.7%) | 0.29 |

| History of Atrial Fibrillation | 105 (2.3%) | 39 (1.6%) | 66(3.1%) | 0.15 |

| Anemia | 1186 (26.5%) | 517 (21.8%) | 669(31.9%) | <0.001 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 15 (0.3%) | 15 (0.3%) | 15 (0.6%) | <0.001 |

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | 25 (0.6%) | 11 (0.5%) | 14 (0.7%) | 0.68 |

| Malignancy | 25 (0.6%) | 15 (0.6%) | 9 (0.4%) | 0.57 |

| AMI Presentation | <0.001 | |||

| STEMI | 1895(42.4%) | 1225 (51.6%) | 671 (32.0%) | |

| NSTEMI | 2576 (57.6%) | 1149 (48.4%) | 1427 (68.0%) | |

| Cardiogenic Shock | 290 (6.5%) | 188 (7.9%) | 102 (4.9%) | 0.03 |

Comorbidity data available from 2008–2014

AMI: Acute myocardial infarction; CABG: Coronary artery bypass grafting; NSTEMI: non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction; PCI: Percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI: ST segment elevation myocardial infarction

Table 4.

Multivariable correlates of invasive management of AMI complicating pregnancy and/or the puerperium in years 2008–2014.

| Variable | Adjusted OR for invasive management of AMI |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–24 | Reference |

| 25–29 | 2.73(1.19 – 6.22) |

| 30–34 | 3.40(1.66 – 6.96) |

| 35–39 | 4.25(2.01 – 8.99) |

| 40–44 | 4.87(2.22 – 10.67) |

| 45+ | 3.31 (1.24 – 8.87) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White non-Hispanic | Reference |

| Black non-Hispanic | 1.32(0.83 – 2.12) |

| Hispanic | 0.61 (0.37 – 1.00) |

| Others | 1.37(0.81 – 2.31) |

| Unknown | 0.54(0.26 – 1.11) |

| Obesity | 0.49(0.27 – 0.89) |

| Tobacco Use | 1.63(0.96 – 2.77) |

| Alcohol Abuse | 3.10(0.71 – 13.66) |

| Drug Abuse | 0.22(0.10 – 0.48) |

| Dyslipidemia | 6.09(3.38 – 10.96) |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 0.24(0.08 – 0.72) |

| Prior Coronary Revascularization | 0.42(0.13 – 1.35) |

| Anemia | 0.75(0.50 – 1.10) |

| ST Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction | 2.90(1.90 – 4.43) |

| Cardiogenic Shock | 1.46(0.80 – 2.68) |

| Hospital Type | |

| Rural | Reference |

| Urban nonteaching | 1.31 (0.521 – 3.31) |

| Urban teaching | 2.00(0.828 – 4.84) |

Among patients who underwent invasive management, intravascular ultrasound was performed in 129 cases overall (2.9%), in 4.1% of STEMI and 2.1% of NSTEMI, and in 9.6% of patients with a discharge diagnosis of coronary dissection. Coronary revascularization was performed in 1,120 (25.1%) cases of AMI during pregnancy or the puerperium. Percutaneous coronary intervention was performed in 881 (78.7%) cases, with stent placement in 784 of these cases (89.0%). Coronary artery bypass grafting was performed in 239 cases (21.3%) and 65 of these patients (27.2%) underwent revascularization with both PCI and CABG. Following US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of second-generation drug eluting stents (2009–2014), drug-eluting stents and bare metal stents were placed in 53.5% and 46.5% of undergoing PCI, respectively. Among patients with coronary artery dissection, coronary revascularization was performed in 443 (68.5%) cases, of which 42.0% underwent PCI, 21.3% underwent CABG, and 5.1% underwent revascularization with both PCI and CABG.

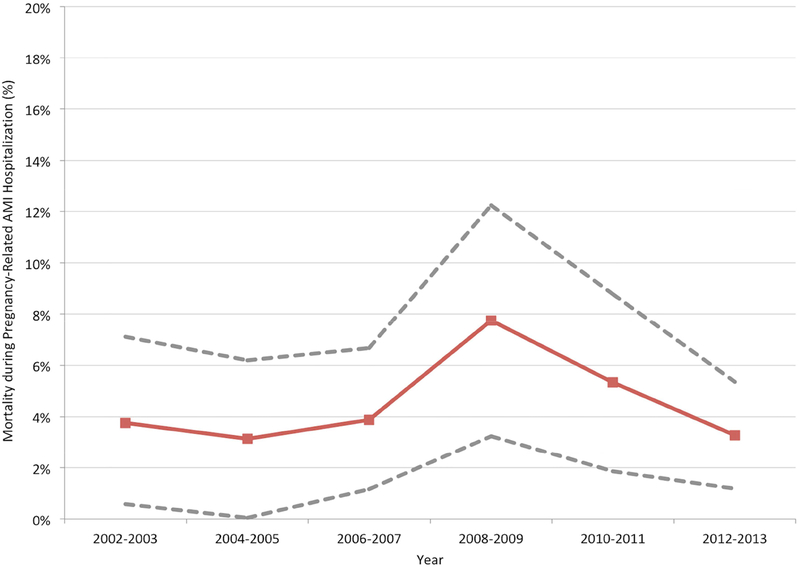

Outcomes

A total of 203 women (4.5%) died in-hospital following AMI that occurred during pregnancy or the puerperium. In-hospital mortality was significantly higher for patients with versus without AMI during pregnancy (adjusted OR [aOR] 39.9, 95% CI 23.3 – 68.4; Supplemental Table 2). In-hospital mortality was not different among patients with AMI during hospitalization for labor and delivery in comparison to those in the antepartum (6.6% vs. 3.2%, P=.10) or post-partum periods (6.6% vs. 4.0%, P=.09). Among women with pregnancy-related AMI, in-hospital mortality for patients with STEMI and NSTEMI was similar (5.0% vs. 4.2%, P=.58). Invasive management of AMI during pregnancy or the puerperium was associated with lower in-hospital mortality than conservative management in unadjusted analyses (1.8% vs. 7.6%, P<.001) and after adjustment for demographic and clinical covariates (aOR 0.17, 95% CI 0.07–0.42).

Trends in AMI Incidence and Outcomes

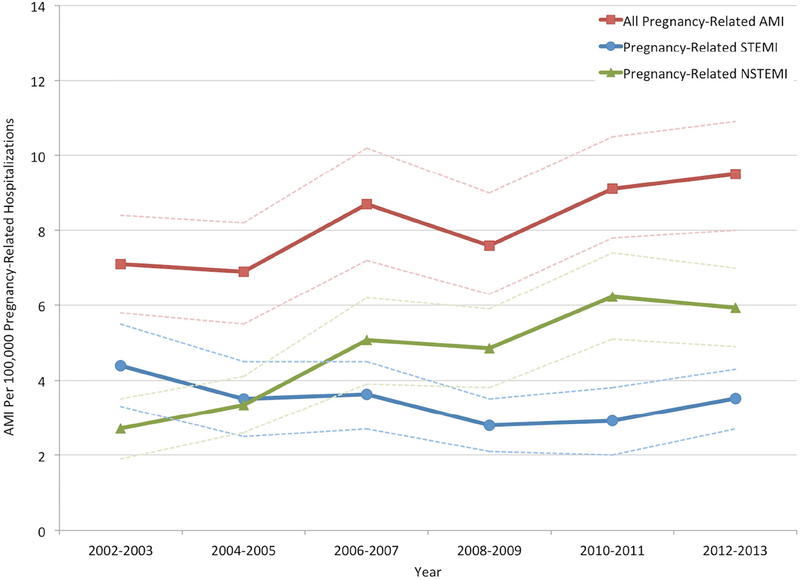

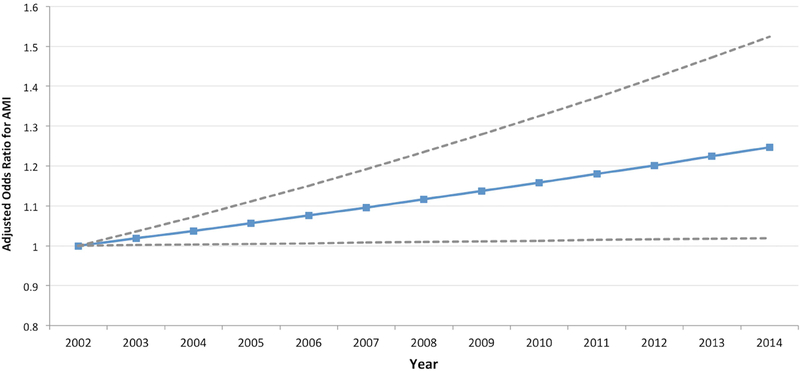

Between 2002 and 2013, the rate of AMI in hospitalizations during pregnancy and the puerperium increased over time (from 7.1 per 100,000 hospitalizations in 2002–03 to 9.5 per 100,000 hospitalizations in 2012–13; P for trend <.001), with an increase in the frequency of NSTEMI diagnoses (P for trend <.001) and a decline in STEMI (P for trend = .001) over time (Figure 2a). The mean age at hospitalization for labor and delivery also increased during this time, from 27.9±5.9 years in 2002–03 to 28.3±5.8 years in 2012–13 (P<.001). Trends in cardiovascular risk factors in patients hospitalized for labor and delivery are shown in the Supplemental Figure. The odds of AMI over time after multivariable adjustment for age and race/ethnicity (aOR 1.25 [for 2014 versus 2002], 95% CI 1.02 – 1.52) are shown in Figure 2b. Mortality associated with AMI remained stable (P for trend=0.24) during the study period (Figure 3).

Figure 2a.

Trends in the frequency of AMI complicating pregnancy and/or the puerperium over time.

P for trends <0.001

Figure 2b.

Odds ratios for acute myocardial infarction associated with pregnancy over time, after adjustment for age and race

Models were adjusted for patient demographics (age and race/ethnicity). Adjusted OR are calculated with 2002–03 as the reference time period. Bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 3.

Trends in the mortality of AMI complicating pregnancy and/or the puerperium over time.

P for trend = 0.24

Discussion:

In this analysis of a large national administrative database, AMI occurred in one in every 12,400 hospitalizations in pregnancy or the puerperium overall, and in one of every 46,921 hospitalizations for labor or delivery. AMI in pregnancy was independently associated with older maternal age, tobacco use, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, known heart failure, anemia, and malignancy. The frequency of AMI diagnoses during pregnancy or the puerperium increased over time, due to an increase in NSTEMI diagnoses. Acute MI during pregnancy was strongly associated with increased in-hospital mortality, in both unadjusted and multivariable-adjusted analyses. Mortality rates in patients with pregnancy-related AMI remained stable over time at 4.5%.

The rising incidence of AMI complicating pregnancy is remarkable, as it occurred despite advances in reduction of cardiovascular risk over the past decade. There are a number of plausible explanations for these trends. Greater numbers of patients of advanced maternal age may underlie some of the trends in AMI reported in this analysis, as the average age of hospitalization for labor and delivery increased over time. In the present study and in prior reports, advanced maternal age is strongly associated with AMI in pregnancy, with up to a 30-fold increased odds in women >40 years in comparison to the pregnant women <20.3, 5 Still, in the present analysis, there was a significant increase in rates of AMI over time after adjustment for age and race. Increases in AMI diagnoses in pregnancy may also be related to changes in the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors or the frequency of cardiac biomarker screening during hospitalization for pregnancy and/or the puerperium. Improved diagnosis of NSTEMI with higher sensitivity cardiac biomarker assays and increasing provider awareness of AMI in women may also be related to the observed findings.

Mechanisms of AMI during pregnancy are uncertain. In many cases, AMI may be due to conventional acute coronary syndromes. Traditional risk factors, including tobacco use, hypertension, and diabetes are independently associated with risk of AMI in pregnancy.2, 3, 7 As women of childbearing age are generally perceived to be at low cardiovascular risk, pre-existing ischemic heart disease may be under-diagnosed in this population. Young women with occult CAD may be less likely to receive intensive management of uncontrolled risk factors.8–11 However, in many cases, AMI may be independent of conventional cardiovascular risk factors. The hypercoagulable state of pregnancy increases the risk of thrombotic coronary syndromes due to increases in fibrinogen and other coagulation factor concentrations coupled with diminished fibrinolysis.12 Substantial increases in the circulating sex hormones estrogen and progesterone, changes in hemodynamics, hemodilution, and increases in cardiac output during pregnancy can lead to progressive connective tissue weakening, increased vascular shear stress, and spontaneous coronary artery dissection.13–15 In the present analysis, coronary dissection was documented in 15% of all AMI, although prior case series suggest that dissection may occur in up to 40% of AMI in pregnancy.5, 7, 16 Consequently, spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) has been frequently cited as a key etiology of AMI in pregnancy and the puerperium.17 The modest frequency of SCAD in the present analysis may reflect under-recognition or under-coding of this important diagnosis. Therefore, the true incidence and outcomes of SCAD in pregnancy warrant further exploration.

Surgical Cesarean sections were associated with higher frequency of AMI than vaginal deliveries in this cohort, another important finding that warrants further study. We were not able to assess the potential contributions of hemodilution, anemia, tachycardia, hypertension, surgical stressors, and other mismatches in myocardial oxygen supply and demand during pregnancy in relation to type 2 AMI.18

The optimal management of AMI in pregnancy remains uncertain. Based on the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines, coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention is the preferred strategy for patients with STEMI during pregnancy (Class I, LOE C) and invasive management should also be considered for patients with NSTEMI and high-risk features (Class IIa, LOE C).12 An analysis of outcomes data from time periods from 1992–1995 and 1995–2005 revealed a marked increase in the rates of percutaneous coronary intervention (from 2% to 42%) and a concomitant decrease in maternal mortality, from 20% to 11%, suggesting an association between invasive management and improved mortality.5 However, in the present analysis, nearly half of women with AMI complicating pregnancy were managed conservatively. This may be related to concerns about potential complications of coronary angiography and PCI in pregnancy, radiation risks to the mother and fetus, or a perception that atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is not anticipated in women of childbearing age. Although coronary angiography is necessary to establish a diagnosis of SCAD, PCI in this setting is associated with high rate of complications and should be reserved for select patients with ischemia refractory to medical therapy.17 Lower than expected invasive management of women with AMI during pregnancy and the puerperium may also relate to uncertainty regarding the safety of drug eluting stents or periprocedural anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy in this setting. Low dose acetylsalicylic acid is considered relatively safe during pregnancy. Thienopyridines are classified by the US FDA as pregnancy category B, although there is insufficient evidence to demonstrate long-term safety in pregnancy. Furthermore, antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy are associated with a risk of peripartum hemorrhage. Other guideline-directed medical therapies for cardiovascular risk reduction, including ACE inhibitors (US FDA pregnancy category D) and statins (US FDA pregnancy category X), are contraindicated in pregnancy due to the risk of harm to the fetus.19

In-hospital mortality rates of 4.5% in the present analysis are similar to previously published reports.3 Maternal case fatality after AMI was highest during the peripartum period and lower in the antepartum and post-partum periods.2, 5 This finding may be related to bleeding risks associated with labor and delivery that may preclude the use of preferred medical and percutaneous therapies for AMI.

Limitations:

There are several limitations to the present analysis. First, trimester of pregnancy could not be determined from this large administrative dataset, nor could the sequence of AMI and delivery when both events occurred during the same hospital admission. Similarly, the duration of the post-partum period is not specified by ICD-9 codes and could not be definitively established for this analysis, although it is conventionally defined as the 6-week period following delivery. However, thrombotic risks may persist beyond this 6-week time period.20 Second, due to the limitations of ICD-9 coding data from a national hospital dataset, detailed findings from coronary angiography were not available for patients who underwent an invasive strategy. As such, the frequency of atherosclerotic plaque rupture, intraluminal thrombus formation, coronary artery dissection, and coronary artery spasm could not be determined from these data. Similarly, the incidence of specific comorbidities associated with coronary artery dissection, such as fibromuscular dysplasia, were also not available. Rates of coronary dissection in this cohort were lower than those reported in small series of AMI in pregnancy.7 Since many women did not undergo coronary angiography for AMI in the present study, under-ascertainment of coronary dissection is possible. Third, in-hospital medical management was not recorded in this administrative dataset and was not available for the present analysis. Fourth, there is potential for undercoding and miscoding from administrative datasets, especially for cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities among patients with and without AMI during pregnancy. Changes in ICD-9 coding over time may have also affected the study findings and represents an unavoidable limitation of an analysis of a large administrative database. Fifth, treatment patterns may have evolved substantially over the 13-year time period used for the present analysis. Specifically, increasing recognition of the ischemic risks during pregnancy, greater sensitivity of cardiac biomarkers, and improvements in percutaneous coronary intervention may have impacted the present findings. As a consequence, definitive statements regarding the benefit of invasive therapy in this small cohort identified over a long time period may be unreliable. Sixth, although maternal in-hospital mortality was reported in the present study, fetal and newborn outcomes were not available. Finally, the study findings were derived from the US population and may not be generalizable to other cohorts.

Conclusions:

In a large national database from the United States, AMI occurred in 8.1 per 100,000 hospitalizations during pregnancy or the puerperium. Overall, 53% of patients with AMI during pregnancy underwent invasive management, and 25% underwent coronary revascularization. Invasive management was independently associated with lower mortality. Despite contemporary management strategies, maternal mortality rates remained high.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Nathaniel R. Smilowitz was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award 5T32HL098129.

Sponsor / Funding: Investigator-initiated

Abbreviations:

- AMI

Acute Myocardial Infarction

- aOR

adjusted OR

- BMS

bare-metal stent

- CABG

coronary artery bypass grafting

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- DES

drug-eluting stent

- HCUP

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision

- NIS

National Inpatient Sample

- NSTEMI

non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- SCAD

spontaneous coronary artery dissection

- STEMI

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- US

United States

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The authors report no relationships that could be construed as a conflict of interest. There is no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

References:

- 1.Roth A, Elkayam U. Acute myocardial infarction associated with pregnancy. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125(9):751–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ladner HE, Danielsen B, Gilbert WM. Acute myocardial infarction in pregnancy and the puerperium: a population-based study. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2005;105(3):480–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.James AH, Jamison MG, Biswas MS, Brancazio LR, Swamy GK, Myers ER. Acute myocardial infarction in pregnancy: a United States population-based study. Circulation. 2006; 113(12): 1564–1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Badui E, Enciso R. Acute myocardial infarction during pregnancy and puerperium: a review. Angiology. 1996;47(8):739–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roth A, Elkayam U. Acute myocardial infarction associated with pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(3):171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.HCUP. Trend Weights for HCUP NIS Data National Inpatient Sample. Vol 2016. Rockville, MD: US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elkayam U, Jalnapurkar S, Barakkat MN, et al. Pregnancy-associated acute myocardial infarction: a review of contemporary experience in 150 cases between 2006 and 2011. Circulation. 2014;129(16):1695–1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pope JH, Aufderheide TP, Ruthazer R, et al. Missed diagnoses of acute cardiac ischemia in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(16):1163–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaul P, Chang WC, Westerhout CM, Graham MM, Armstrong PW. Differences in admission rates and outcomes between men and women presenting to emergency departments with coronary syndromes. CMAJ. 2007; 177(10):1193–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levit RD, Reynolds HR, Hochman JS. Cardiovascular disease in young women: a population at risk. Cardiology in review. 2011;19(2):60–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bangalore S, Fonarow GC, Peterson ED, et al. Age and gender differences in quality of care and outcomes for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am JMed. 2012;125(10):1000–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Society of G, Association for European Paediatric C, German Society for Gender M, et al. ESC Guidelines on the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy: the Task Force on the Management of Cardiovascular Diseases during Pregnancy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2011;32(24):3147–3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manson JE, Hsia J, Johnson KC, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and the risk of coronary heart disease. NEngl J Med. 2003;349(6):523–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanis BC, van den Bosch MA, Kemmeren JM, et al. Oral contraceptives and the risk of myocardial infarction. NEngl J Med. 2001;345(25):1787–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saw J, Mancini GB, Humphries KH. Contemporary Review on Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(3):297–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lameijer H, Kampman MA, Oudijk MA, Pieper PG. Ischaemic heart disease during pregnancy or post-partum: systematic review and case series. Netherlands heart journal : monthly journal of the Netherlands Society of Cardiology and the Netherlands Heart Foundation. 2015;23(5):249–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayes SN, Kim ESH, Saw J, et al. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: Current State of the Science: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018. February 22 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smilowitz NR, Naoulou B, Sedlis SP. Diagnosis and management of type II myocardial infarction: increased demand for a limited supply of evidence. Current atherosclerosis reports. 2015;17(2):478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehta LS, Beckie TM, DeVon HA, et al. Acute Myocardial Infarction in Women: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(9):916–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamel H, Navi BB, Sriram N, Hovsepian DA, Devereux RB, Elkind MS. Risk of a thrombotic event after the 6-week postpartum period. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(14): 1307–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.