Abstract

Background

Rapid point-of-care (POC) assessment of hemostasis is clinically important in patients with a variety of coagulation factor and platelet defects who have bleeding disorders.

Objective

To evaluate a novel dielectric microsensor, termed ClotChip, which is based on the electrical technique of dielectric spectroscopy for rapid, comprehensive assessment of whole blood coagulation.

Methods

The ClotChip is a three-dimensional, parallel-plate, capacitive sensor integrated into a single-use microfluidic channel with miniscule sample volume (<10 μL). The ClotChip readout is defined as the temporal variation in the real part of dielectric permittivity of whole blood at 1 MHz.

Results

The ClotChip readout exhibits two distinct parameters, namely, the time to reach a permittivity peak (Tpeak) and the maximum change in permittivity after the peak (Δεr,max) that are respectively sensitive towards detecting non-cellular (i.e., coagulation factor) and cellular (i.e., platelet) abnormalities in the hemostatic process. We evaluated the performance of ClotChip using clinical blood samples from 15 healthy volunteers and 12 patients suffering from coagulation defects. The ClotChip Tpeak parameter exhibited superior sensitivity at distinguishing among coagulation disorders as compared to conventional screening coagulation tests. Moreover, the ClotChip Δεr,max parameter detected platelet function inhibition induced by aspirin and exhibited strong positive correlation with light transmission aggregometry.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that ClotChip assesses multiple aspects of the hemostatic process in whole blood on a single disposable cartridge, highlighting its potential as a POC platform for rapid, comprehensive hemostatic analysis.

Introduction

Early identification of hemostatic dysregulation and bleeding risk is important in the management of patients who are critically ill, severely injured, or on antiplatelet/anticoagulation therapies [1]. Conventional laboratory-based coagulation tests are time-consuming, labor-intensive, and are not reliable indicators of hemostatic risk. Extant handheld point-of-care (POC) devices have uses that are limited to specific patient populations (e.g., CoaguChek for warfarin use), have low thromboplastin and partial thromboplastin reagent sensitivity (e.g., i-STAT device) resulting in only sub-optimal assessment of the coagulation process, and do not provide concurrent information on platelet function. Although thromboelastography (TEG) and rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) allow for the analysis of several aspects of clot formation and strength, representing a global measure of the hemostatic process, these viscoelastic tests rely on sensitive mechanical components that are expensive and difficult to miniaturize. Hence, there is an unmet clinical need for a low-cost, easy-to-use, and portable platform for comprehensive POC assessment of hemostasis outside of a central laboratory.

To address this need, we adapted the method of dielectric spectroscopy (DS), an electrical, label-free, and noninvasive technique, to monitor the hemostatic process ex vivo in a disposable microfluidic sensor. DS is the quantitative measurement of permittivity versus frequency and is a well-established method to extract information on the molecular and cellular components of biological tissues [2,3]. The main response of blood DS measurements in the MHz-frequency range arises from the interfacial polarization of cellular components [4,5]. DS measurements within the resulting dispersion region are used to gain information on the physical properties of blood [6,7]. In particular, DS measurements on blood in the MHz-frequency range are sensitive to aggregation of erythrocytes into a fibrin clot and subsequent erythrocyte deformation as a result of contractile forces from activated platelets [8–10] that characteristically occur during clot formation [11]. DS that assesses the blood coagulation process is termed dielectric coagulometry. We have developed a novel dielectric microsensor, termed ClotChip, which performs dielectric coagulometry on a miniscule volume (<10 μL) of whole blood. Presently, we show that ClotChip readouts are sensitive to several aspects of the hemostatic process, including thrombin formation and platelet activation. These features allow for comprehensive assessment of the hemostatic process ex vivo in a potentially portable platform, which is ideal for a POC device.

Methods

ClotChip Fabrication and Measurements

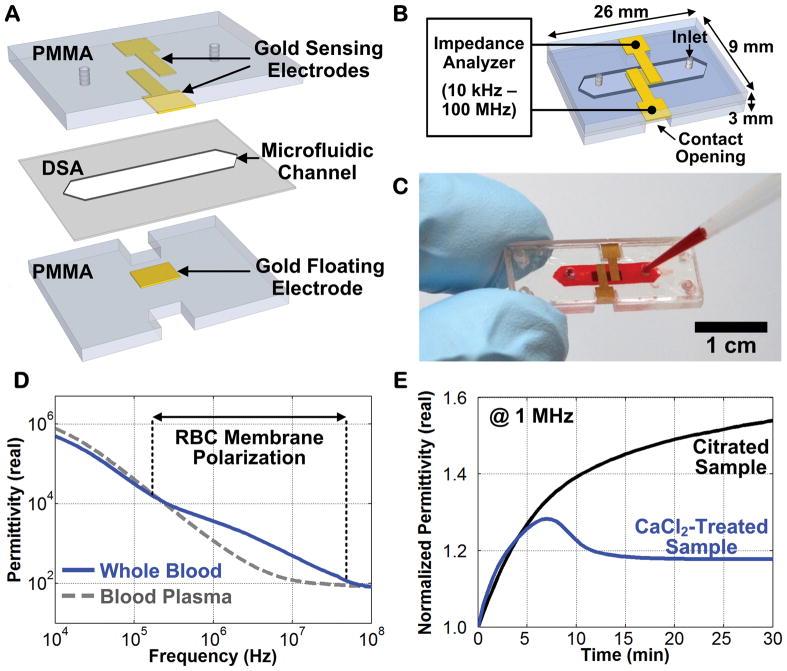

The ClotChip featured a parallel-plate capacitive sensor to extract the dielectric permittivity of whole blood within a microfluidic channel [12]. Two planar sensing electrodes were separated from a floating electrode through a microfluidic channel to form a three-dimensional capacitive sensing area. With a blood sample passing through this area, the impedance of the sensor would change based upon its dielectric permittivity. ClotChip was fabricated using biocompatible, chemically inert, polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) plastic substrate and cap (Figure 1A) [13,14]. The sensor fabrication and assembly process was based on a low-cost (<$1 material cost per chip), batch-fabrication method of screen-printing gold electrodes onto a 1.5 mm-thick PMMA plastic substrate and cap. A double-sided-adhesive (DSA) film with thickness of 250 μm was laser micromachined to form the walls of a microfluidic channel with dimensions of 12 mm × 3 mm, and then the ClotChip was assembled by attaching the PMMA cap to the PMMA substrate using the DSA film (Figure 1B). The fabricated sensor (Figure 1C) had a size of 26 mm × 9 mm × 3 mm and a total sample volume of 9 μL. The sensor was loaded with whole blood using a micropipette, placed into a thermostatic chamber set at 37°C, and characterized with an impedance analyzer (Agilent 4294A) over a frequency range of 10 kHz–100 MHz to capture the dispersion region associated with red blood cell (RBC) membrane polarization (Figure 1D). Measurements were performed in 10-sec intervals over a total measurement time of 30 min. The electrical properties of whole blood varied during coagulation, and a measurement frequency of 1 MHz was chosen to maximize the sensitivity to clot formation dynamics, including RBC aggregation and deformation. Therefore, the ClotChip readout was taken as the temporal variation in the real part of blood dielectric permittivity at 1 MHz (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

Study Design

All healthy volunteers and patients who enrolled in this study provided informed consent. The collection and use of blood samples from subjects were approved by the Institutional Review Board of University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center. Blood samples were drawn by venipuncture into collection tubes containing 3.2% sodium citrate anticoagulant (ratio of blood to anticoagulant = 9:1), and were used for both ClotChip measurements and conventional coagulation assays. Healthy volunteers were accrued only if they were off of medications and without diagnosis of an illness in the past 4 weeks. Twelve patients with coagulation defects (Table 1) were accrued from a hematology clinic and had been previously characterized by comprehensive medical history, screening coagulation tests, and specialized coagulation studies.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with coagulopathy.

| Patient | Diagnosis | ClotChip Tpeak (240–505 sec) | PT (9.3–14 sec) | aPTT (24–35 sec) | Specialized Coagulation Assays |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | FXII deficiency | 3,550 | 13.8 | > 120 | FXII:C: < 1% |

| A2 | Hemophilia A | 730 | 14 | 34.4 | FVIII:C: 50% |

| A3 | Hemophilia A w/Inhibitor | 980 | 12.2 | 43.1 | FVIII:C: 2–3% |

| A4 | Hemophilia A | 735 | 13.9 | 39.1 | FVIII:C: 2–4% |

| A5 | Hemophilia A | 900 | 13.9 | 38.3 | FVIII:C: 11% |

| A6 | Hemophilia A w/Inhibitor | 2,420 | 12.4 | 41.5 | FVIII:C: < 1% |

| A7 | Hemophilia A | 1,350 | 13.5 | 49.4 | FVIII:C: < 1% |

| A8 | Hemophilia B | 675 | 13.5 | 37.7 | FIX:C: 10% |

| A9 | Hemophilia B | 860 | 13.9 | 43.2 | FIX:C: 3% |

| A10 | Hemophilia A | 990 | 13 | 43.3 | FVIII:C: 4% |

| A11 | Hemophilia B | 1,335 | 13 | 37.7 | FIX:C: 11% |

| A12 | von Willebrand Disease Type IIB – V1316A polymorphism in A1 region of vWF | 680 | 12.8 | 29.8 | vWF antigen: 44% vWF activity (RCA): 35% vWF multimers: loss of high-molecular-weight multimers FVIII:C: 62% |

Patients with classic hemostatic defects were accrued from a specialty hematology clinic and agreed to participate in this study. ClotChip measurements along with relevant coagulation tests were performed. FVIII:C: Factor VIII coagulant activity (%); FIX:C: Factor IX coagulant activity (%); FXII:C: Factor XII coagulant activity (%); vWF: von Willebrand Factor; RCA: Ristocetin Co-factor Assay.

ClotChip measurements were performed in a research laboratory by a trained doctoral student within 2 hours from the time of blood collection. Prior to measurements and to initiate coagulation, 25.6 μL of 250 mM CaCl2 was pipetted into 300 μL of citrated blood sample that was pre-warmed to 37°C in a heating chamber, and 10 μL of the mixture was immediately injected into the ClotChip.

Additional ClotChip measurements were performed with whole blood obtained by fingerstick using a 23-gauge lancet and wiping away the first drop of blood. Another 2–3 drops of blood were collected in a polypropylene tube after which 10 μL of whole blood was immediately injected into the ClotChip using a micropipette. Duplicate measurements were performed within 1 min following the fingerstick procedure.

Calibration of the measurement setup was performed daily to implement quality control and ensure accurate electrical measurement of the blood sample. This step was performed using a custom printed-circuit board in the form of the ClotChip sensor that contained an equivalent circuit model of whole blood [12]. Additional quality control was implemented by testing a control sample from a pool of known healthy volunteer donors on each day that patient samples were examined.

Platelet Inhibition Studies

Platelet inhibition studies were performed ex vivo with blood samples from 10 healthy volunteers. Samples for ClotChip measurements were prepared by mixing whole blood with 120 mM aspirin in DMSO (final aspirin concentration of 0 to 2 mM) followed by incubation for 30 min at room temperature. Light transmission aggregometry (LTA) experiments were performed using platelet-rich plasma (PRP) within 3 hours of blood collection. PRP was diluted to 2.2 × 108 platelets per mL, then treated with aspirin (1 or 2 mM) for 30 min at room temperature. Aggregation was initiated with ADP (5 or 10 μM), arachidonic acid (0.5 mM), or SFLLRN (PAR1 agonist peptide, 10 μM). Aggregation was measured using a lumi-aggregometer (Model 700, Chrono-log Corp). The sample was stirred constantly at 1,200 RPM at 37°C.

Statistical Analysis

Data obtained in this study are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Wilcox matched-pairs signed test was used for comparing outcomes between two paired groups and Mann-Whitney U-test otherwise. All statistical comparisons were two-tailed. The statistical significance threshold was set at 95% confidence level for all tests (p < 0.05). Statistical data analysis was performed using Minitab 17 and GraphPad Prism software suites.

Results and Discussion

ClotChip measurements from 15 healthy volunteers who had normal activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and prothrombin time (PT) values are shown in Figure 2A. A characteristic rise to a permittivity peak was observed within 240–505 sec (Tpeak). Based on our previous studies, the Tpeak parameter was taken to be indicative of coagulation time [14,15]. ClotChip measurements then were performed with 12 patient samples obtained from individuals with well-characterized bleeding disorders. Compared to the normal curve, samples from patients with coagulopathy exhibited abnormal curves (Figure 2B) with a significantly prolonged Tpeak range of 675–3,550 sec (p < 0.0001; Figure 2C). The precision of Tpeak was evaluated by calculating a percentage coefficient of variance (CV) as the ratio of the within-subject standard deviation and the overall mean × 100 [16]. We used duplicate measurements from the 15 normal samples and 12 patient samples to establish a CV for “normal” and “high” ranges of Tpeak, respectively. The normal samples exhibited a mean Tpeak of 371 sec and CV of 7.6%. The patient samples exhibited a mean Tpeak of 1,267 sec and CV of 8.6%. The ClotChip CV values are similar to the reported precision (~6%) of a commercially available, POC, blood coagulation test [17].

Figure 2.

Conventional coagulation tests (aPTT and PT) were also performed for each sample. It should be noted that the most prolonged aPTT coagulation time was observed in the sample with factor XII deficiency, which also had the most prolonged Tpeak. We also observed prolonged aPTT coagulation times as well as prolonged Tpeak values in all moderate and severe hemophilia samples, accurately capturing this type of coagulopathy. However, for mild hemophilia A and von Willebrand Type IIB cases, both the aPTT and PT were normal. These patients were diagnosed with specialized coagulation assays following referral to our hematology clinic for work-up of clinical bleeding. In both cases, the ClotChip readout did show a prolonged Tpeak, indicating its superior sensitivity. Taken together, the data confirmed that ClotChip could capture defects at multiple aspects of the hemostatic pathway, with improved sensitivity as compared to standard screening coagulation tests.

We then investigated the effect of aspirin-induced inhibition of platelet activity on the ClotChip readout. Samples were treated with various concentrations of aspirin ex vivo. LTA studies were run on each sample, and we observed that with arachidonic acid-induced platelet aggregation, the percentage aggregation was reduced from >70% for baseline measurements to <5% for all aspirin-treated samples, confirming platelet inhibition in response to aspirin treatment. We found that aspirin treatment did not significantly change Tpeak (Figure 2D), as we had previously observed with coagulation factor defects. However, aspirin dose-dependently decreased the Δεr,max parameter, defined as one minus the ratio of final permittivity (i.e., permittivity at 30 min) and peak permittivity (i.e., permittivity at Tpeak; Figure 2E). Compared to untreated samples, a significant decrease in Δεr,max was observed for samples that were treated with 1 mM aspirin (n = 10, p < 0.0001) or 2 mM aspirin (n = 10, p < 0.0001; Figure 2F). The ClotChip Δεr,max parameter exhibited the strongest correlation (r = 0.81, p < 0.001, n = 30) to the percentage aggregation parameter of LTA with 5 μM ADP (Figure 2G). These data showed that the ClotChip Δεr,max parameter was sensitive to platelet activity.

Finally, we investigated the effect of pre-analytical conditions on the ClotChip readout. To test sample stability, we performed repeated measurements at different time points for blood samples from 6 healthy volunteers. Samples were stored at room temperature, and duplicate ClotChip measurements were performed at 30 min, 1.5 hr, 2.5 hr, 3.5 hr, and 4.5 hr after blood collection. The studies showed a downward trend in mean Tpeak as storage time increased (Figure 3A). The first of these results (performed 30 min after blood collection) represented the reference Tpeak for each sample, and the stability at different time points was analyzed via comparison to this first Tpeak value [18]. A significant difference was found for groups at 3.5 hr (p < 0.005) and 4.5 hr (p < 0.005) compared to the group at 30 min. No significant difference was found for groups at 2.5 hr and 1.5 hr compared to 30 min. These results demonstrate that ClotChip readout exhibits repeatable characteristics for citrated whole blood tested within 2.5 hours from blood draw.

Figure 3.

We then investigated the feasibility of using whole blood obtained from a fingerstick blood-collection method. Five healthy volunteers were recruited to donate blood by fingerstick and venipuncture techniques. Figure 3B shows nearly identical ClotChip readout for whole blood obtained by fingerstick and re-calcified whole blood obtained from venipuncture. While we did observe a decrease in Tpeak values for fingerstick samples (range: 260–360 sec) compared to re-calcified venipuncture samples (range: 320–440 sec) as shown in Figure 3C, the Tpeak values for all fingerstick samples fell within the range of all 15 healthy volunteers, as reported above (Figure 2A, C). This study demonstrates the potential of ClotChip to accurately perform with whole blood obtained from a fingerstick.

In conclusion, we show that the ClotChip readout of dielectric permittivity of whole blood at 1 MHz is sensitive to a wide range of hemostatic defects. Specifically, two distinct parameters of the ClotChip readout, Tpeak and Δεr,max, provide independent information on hemostatic defects arising from non-cellular (i.e., coagulation factor) and cellular (i.e., platelet) components, respectively, thereby allowing a discriminatory assessment of the comprehensive blood coagulation process. While early work on dielectric coagulometry revealed sensitivity to both clotting time and platelet activity [19–21], this technique was restricted to laboratory-based benchtop equipment and >100 μL-volume samples [22–25]. The ClotChip sensor used in this study features a simple fabrication process and enables dielectric coagulometry to be performed with <10 μL of blood sample volume in a disposable sensor. Furthermore, the electrical technique of dielectric coagulometry does not require bulky optical or mechanical components and is thus ideal for a POC platform. Although a small sample size of patients with known coagulation defects was employed in this proof-of-concept investigation, these initial studies pave the way for the development of a portable platform that allows for clinical testing to be performed at the POC. In future investigations we plan to expand the sample size, use the device to screen patients for disease, assess blood coagulation testing phenomena like lupus anticoagulants, and determine the correlation of test results with bleeding. We believe these studies are needed before translation to clinical practice. Nonetheless, our present work establishes that ClotChip has potential as a portable platform for rapid, comprehensive assessment of hemostasis at the POC using <10 μL of whole blood.

Essentials.

ClotChip is a novel microsensor for comprehensive assessment of ex vivo hemostasis.

Clinical samples show high sensitivity to detecting the entire hemostatic process.

ClotChip readout exhibits distinct information on coagulation factor and platelet abnormalities.

ClotChip has potential as a point-of-care platform for comprehensive hemostatic analysis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Lalitha V. Nayak, Case Western Reserve University, for providing additional clinical samples. This work was supported by the American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid 17GRNT33661005 (M. A. Suster and P. Mohseni), American Heart Association Scientist Development Award 15SDG25590000 (E. X. Stavrou), NIH Grants R01 HL126645 and R01 AI130131-01 (A. H. Schmaier), NIH Grant 5R01 HL121212 (A. Sen Gupta), DOD Grant BC150596P1 (A. H. Schmaier), the Case School of Engineering’s San Diego-based Wireless Health program, the Case-Coulter Translational Research Partnership, and the Advanced Platform Technology (APT) Center – A Veterans Affairs (VA) Research Center of Excellence at Case Western Reserve University. The contents do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Addendum

D. Maji, M. De La Fuente, E. Kucukal, U. D. S. Sekhon, and E. X. Stavrou performed experiments; M. A. Suster, E. X. Stavrou, P. Mohseni, M. T. Nieman, A. H. Schmaier, U. A. Gurkan, and A. Sen Gupta conceptualized and planned experiments; A. H. Schmaier and E. X. Stavrou designed the study and obtained clinical samples; P. Mohseni, D. Maji, M. A. Suster, and E. X. Stavrou prepared the figures; M. A. Suster, D. Maji, E. X. Stavrou, and P. Mohseni wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure:

D. Maji, U. A. Gurkan, E. X. Stavrou, P. Mohseni, and M. A. Suster are inventors of intellectual property that has been licensed by Case Western Reserve University to XaTek, Inc.

M. A. Suster and P. Mohseni receive consulting fees from XaTek, Inc.

References

- 1.Levi M, Hunt BJ. A critical appraisal of point-of-care coagulation testing in critically ill patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13:1960–7. doi: 10.1111/jth.13126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaatze U, Feldman Y. Broadband dielectric spectrometry of liquids and biosystems. Meas Sci Technol. 2006;17:R17. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kremer F. Dielectric spectroscopy – yesterday, today and tomorrow. J Non-Cryst Solids. 2002;305:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdalla S, Al-Ameer SS, Al-Magaishi SH. Electrical properties with relaxation through human blood. Biomicrofluidics. 2010;4:034101. doi: 10.1063/1.3458908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolf M, Gulich R, Lunkenheimer P, Loidl A. Broadband dielectric spectroscopy on human blood. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA-Gen Subj. 2011;1810:727–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asami K. Characterization of biological cells by dielectric spectroscopy. J Non-Cryst Solids. 2002;305:268–277. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heileman K, Daoud J, Tabrizian M. Dielectric spectroscopy as a viable biosensing tool for cell and tissue characterization and analysis. Biosens Bioelectron. 2013;49:348–59. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asami K, Sekine K. Dielectric modelling of erythrocyte aggregation in blood. J Phys Appl Phys. 2007;40:2197. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayashi Y, Oshige I, Katsumoto Y, Omori S, Yasuda A, Asami K. Dielectric inspection of erythrocyte morphology. Phys Med Biol. 2008;53:2553–64. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/10/007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merla C, Liberti M, Apollonio F, Nervi C, D’Inzeo G. Dielectric spectroscopy of blood cells suspensions: study on geometrical structure of biological cells. Proceedings of the 28th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); 2006; pp. 3194–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byrnes JR, Duval C, Wang Y, Hansen CE, Ahn B, Mooberry MJ, Clark MA, Johnsen JM, Lord ST, Lam WA, Meijers JCM, Ni H, Ariëns RAS, Wolberg AS. Factor XIIIa-dependent retention of red blood cells in clots is mediated by fibrin α-chain crosslinking. Blood. 2015;126:1940–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-06-652263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suster MA, Vitale NH, Maji D, Mohseni P. A circuit model of human whole blood in a microfluidic dielectric sensor. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst II Express Briefs. 2016;63:1156–60. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maji D, Suster MA, Kucukal E, Gurkan UA, Stavrou EX, Mohseni P. A PMMA microfluidic dielectric sensor for blood coagulation monitoring at the point-of-care. Proceedings of the 38th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); 2016; pp. 291–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maji D, Suster MA, Kucukal E, Sekhon UDS, Gupta AS, Gurkan UA, Stavrou EX, Mohseni P. ClotChip: A microfluidic dielectric sensor for point-of-care assessment of hemostasis. IEEE Trans Biomed Circuits Syst. 2017;11:1459–69. doi: 10.1109/TBCAS.2017.2739724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maji D, Suster MA, Stavrou E, Gurkan UA, Mohseni P. Monitoring time course of human whole blood coagulation using a microfluidic dielectric sensor with a 3D capacitive structure. Proceedings of the 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); 2015; pp. 5904–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Synek V. Evaluation of the standard deviation from duplicate results. Accreditation Qual Assur. 2008;13:335–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braun S, Watzke H, Hasenkam JM, Schwab M, Wolf T, Dovifat C, Völler H. Performance evaluation of the new CoaguChek XS system compared with the established CoaguChek system by patients experienced in INR-self management. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97:310–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Camenzind V, Bombeli T, Seifert B, Jamnicki M, Popovic D, Pasch T, Spahn DR. Citrate storage affects Thrombelastograph analysis. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:1242–9. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200005000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ur A. Changes in the electrical impedance of blood during coagulation. Nature. 1970;226:269–70. doi: 10.1038/226269a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ur A. Determination of blood coagulation using impedance measurements. Biomed Eng. 1970;5:342–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ur A. Detection of clot retraction through changes of the electrical impedance of blood during coagulation. Am J Clin Pathol. 1971;56:713–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/56.6.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayashi Y, Katsumoto Y, Omori S, Yasuda A, Asami K, Kaibara M, Uchimura I. Dielectric coagulometry: a new approach to estimate venous thrombosis risk. Anal Chem. 2010;82:9769–74. doi: 10.1021/ac101927n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayashi Y, Brun M-A, Machida K, Nagasawa M. Principles of dielectric blood coagulometry as a comprehensive coagulation test. Anal Chem. 2015;87:10072–9. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b02723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiba S, Uchibori K, Fujiwara T, Ogata T, Yamaguchi S, Shirai T, Masuo M, Okamoto T, Tateishi T, Furusawa H, Fujie T, Sakashita H, Tsuchiya K, Tamaoka M, Miyazaki Y, Inase N, Sumi Y. Dielectric blood coagulometry as a novel coagulation test. J Sci Res Rep. 2015;4:180–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otaki Y, Ebana Y, Yoshikawa S, Isobe M. Dielectric permittivity change detects the process of blood coagulation: Comparative study of dielectric coagulometry with rotational thromboelastometry. Thromb Res. 2016;145:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2016.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]