Abstract

Single-photon emitters (SPEs) play an important role in a number of quantum information tasks such as quantum key distributions. In these protocols, telecom wavelength photons are desired due to their low transmission loss in optical fibers. In this paper, we present a study of bright single-photon emitters in cubic silicon carbide (3C-SiC) emitting in the telecom range. We find that these emitters are photostable and bright at room temperature with a count rate of ~ MHz. Altogether with the fact that SiC is a growth and fabrication-friendly material, our result may be relevant for future applications in quantum communication technology.

Room-temperature solid-state single photon emitters in the telecom range are suitable for quantum communication. Here, the authors observe defects in high-purity 3C-SiC epitaxy layers grown on a silicon substrate, with good characteristics in terms of brightness, emission’s polarization and photostability.

Introduction

Single-photon emitters (SPE) are used to generate “flying qubits” and they are critical in many quantum technology protocols such as quantum information processing1–4, quantum simulation5–7, quantum networks, and quantum communications8–11. Especially, in quantum key distribution (QKD), photons are used to send information in a secure way, protected by quantum mechanics11. Despite the fact that most QKD implementations use weak attenuated lasers to simulate SPE, a true SPE is still preferred due to its longer secure distance in theory and therefore its potentially better performance. In previous pioneer works, single-photon quantum cryptography has been demonstrated with photons emitted from a single nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond12. The difficulty of QKD using true SPE lies on the fact that it is challenging to find a bright, room temperature (RT) SPE working in the telecom range, which is required to minimize the transmission loss in optical fibers.

Extensive efforts have been made to realize telecom-compatible SPE. InAs/InP QDs (quantum dots) present single-photon emission at telecom wavelength13 and they have been utilized to realize 120 km QKD14. However, QDs require operation at cryogenic temperatures, which makes their use experimentally more demanding. Most recently, room temperature SPEs in carbon nanotubes have equally been demonstrated to have emission in the telecom range15,16.

SiC is a wide band gap semiconductor widely used in LED industry. It is also a prominent material in the application of advanced high power, high temperature electronics. In recent years, defects in SiC have attracted increasing attention owing to their magneto-optical properties and the convenience for fabrication and scalability. Different types of SPEs have been discovered in SiC17, such as carbon antisite–vacancy pair18,19, silicon vacancies20–24, and divacancies25–27. However, those SPEs have emission either in the visible range18–24,28 or being weak in the near-infrared range25–27.

In this paper, we present a type of bright ( ~ MHz) single emitters in 3C-SiC, which work at room temperature and emit in the telecom range. The sample we use is high-purity 3C-SiC epitaxy layer grown on a silicon substrate. First, we measured the photoluminescence (PL) spectrum of different SPEs and find that their fluorescence wavelengths lie in the telecom region. Then we investigated their optical properties: photostability and saturation behavior. Our results show that they have stable count rates of ~ MHz at room temperature. Finally, we investigate their polarization properties for both excitation and emission, which demonstrate that these emitters can be treated as almost perfect single dipole. The polarization degree of both excitation and emission can reach up to around 97%. All these properties are highly desired in the QKD protocols with polarization coding scheme.

Results

Single-photon emission

The use of an epitaxial layer ensures a low background level for SPEs detection. Moreover, it provides a natural way to obtain thin membranes for photonics and micromechanics applications rather than the thinning of bulk crystals26. We study the PL property of the emitters in home-made confocal microscopy systems. For the room temperature experiments, a 950 nm diode laser is used to excite the emitters through a high-NA (1.35) oil objective (Nikon). After passing through a 1000-nm dichroic mirror and a 1000-nm long pass filter, the fluorescence from the emitters is collected by a single-mode fiber. The emission is then guided to two channel superconducting single-photon detectors (SSPD, Scontel) in a Hanbury-Brown and Twiss (HBT) set-up. In the cryogenic experiments, we use a closed cycle cryostation (Montana Instruments) combined with a confocal microscopy system with an infrared air objective with NA of 0.65.

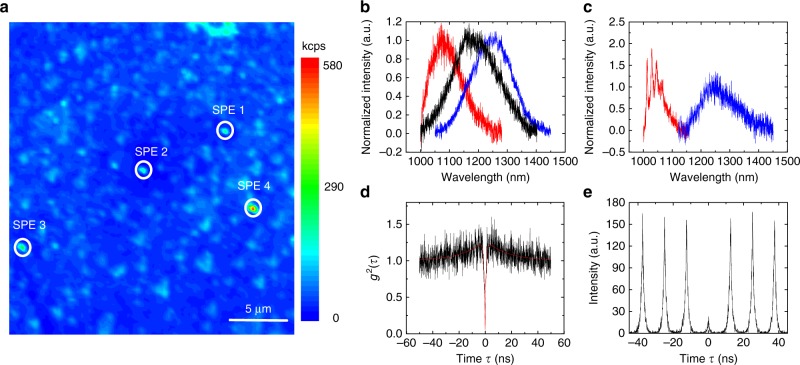

Figure 1a shows a confocal scan of the single emitters in an area of 25 × 25 µm2. Four bright SPEs are circled, which are verified by the continuous wave (CW) second-order autocorrelation function measurement using HBT interferometry. Then we continue to study the PL spectrum of the SPEs. As shown in Fig. 1b, the center wavelengths of three representative RT PL spectra are 1085, 1188, and 1250 nm. By measuring the PL spectrum of many SPEs, we find that the center wavelength of different emitters ranges from 1080 to 1265 nm and the FWHM of the linewidth ranges from 128 to 194 nm. Figure 1c displays a low-temperature (4 K) PL spectrum of the two representative SPEs. There is no sizable reduction of the linewidth, which shows that the linewidth broadening is not caused by phonons. In one of the SPEs, several sharp lines appear in low-temperature, which might come from emission coupled to phonons.

Fig. 1.

3C-SiC single-photon emitters. a 25 × 25 µm2 confocal can map of the SPEs found in 3C SiC epitaxy layer under 2 mW laser excitation. The scale bar is 5 µm. SPEs are marked with white circles. b Three representative RT PL spectrums of the SPEs. c Two representative PL spectrums of the SPEs at cryogenic temperature (5 K). d Second-order autocorrelation function of SPE 4 with g2(0) = 0.05 ± 0.03 under 0.2 mW continuous wave (CW) laser excitation. The black line is the raw data and red solid line is the fitting with Eq. (1). e Second-order autocorrelation function of SPE 4 with g2(0) = 0.13 ± 0.02 under pulsed laser excitation (50 µW)

Photon properties of the SPEs

Next, we focus on one of the bright emitters and and analyze their photon emission statistics with an HBT interferometer. Figure 1d shows the CW second-order autocorrelation function of SPE 4 (in Fig. 1a) under 0.2 mW excitation. The red line is the fitting result. In order to remove influence of the background, the raw autocorrelation function g2raw(τ) of the correlation function is corrected using the function g2(τ) = [g2raw(τ) − (1 − ρ2)]/ρ2 where ρ = s/(s + b). Here, s and b are the signal and background counts, respectively21,26. The background-corrected g2(τ) is then fitted using the function

| 1 |

where a, τ1, τ2 are power-dependent fitting parameters. From the fitting, the obtained value at zero time delay g2(0) = 0.05 ± 0.03. Figure 1e shows pulsed second-order autocorrelation function measurement of SPE 4 using 950 nm picosecond laser (50 µW) with a repetition rate of 80 MHz. The obtained value at zero time delay g2(0) = 0.13 ± 0.02. Which is well below 0.5 and, therefore, undoubtedly proves its nature of single-photon emission. Other emitters show similar experimental results.

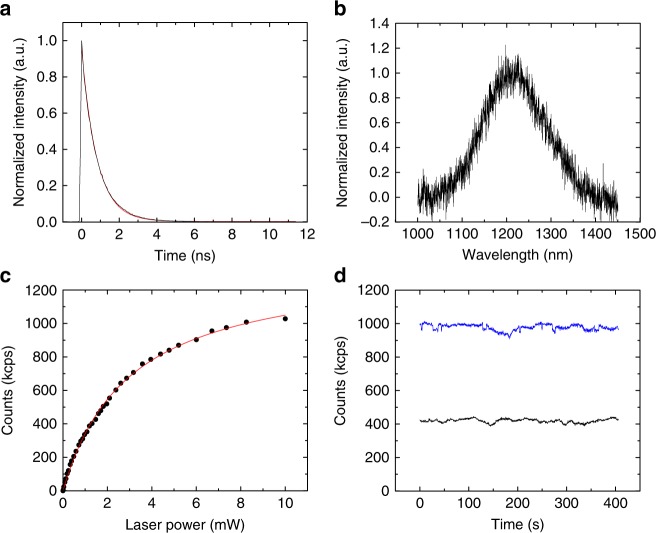

To further study the optical properties of the SPEs, we measured their lifetimes, power dependence and photostability. Figure 2a, b shows the spectrum and lifetime of the SPE 4. A lifetime of 0.81 ± 0.01 ns is obtained from the fitting with a single-exponential equation I(t)exp(−t/τ) where I(t) is the fluorescence intensity, and τ is the fluorescence lifetime. Next, we investigate the saturation behavior of the emitter SPE 4 under different power excitation. The total emission rate as a function of excitation power P is presented in Fig. 2c. The red line is the fitting of the date using the power dependence model I(P) = Is/(1 + P0/P), where Is is the maximal emission counts and P0 is the saturation power. Inferred from the fitting, the maximum count rate Is is about 1.36 Mcps and the saturation power P0 was about 3.0 mW. Moreover, fluorescence intensity trace of the emitter at the excitation powers of 1.5 mW and 8.2 mW with a sampling time bin size of 100 ms is displayed in Fig. 2d. The emission is stable without photon blinking or photon bleaching even under a high power excitation (8.2 mW), which verified that it is a room temperature photostable SPE.

Fig. 2.

Single-photon emitter characterization. a Lifetime measurement. The black curve is the raw data fitted with a single-exponential equation I(t)exp( − t/τ). From the fitting, τ = 0.81 ± 0.01 ns. b RT PL spectrum of the SPE 4. c Saturation behavior of the SPE 4 at different laser powers. The black curve is the raw data fitted with I(P) = Is/(1 + P0/P). d Fluorescence intensity trace at laser powers 1.5 mW (black) and 8.2 mW (blue) with a sampling time of 100 ms and duration 400 s at room temperature. No obvious blinking has been observed

Three-level model

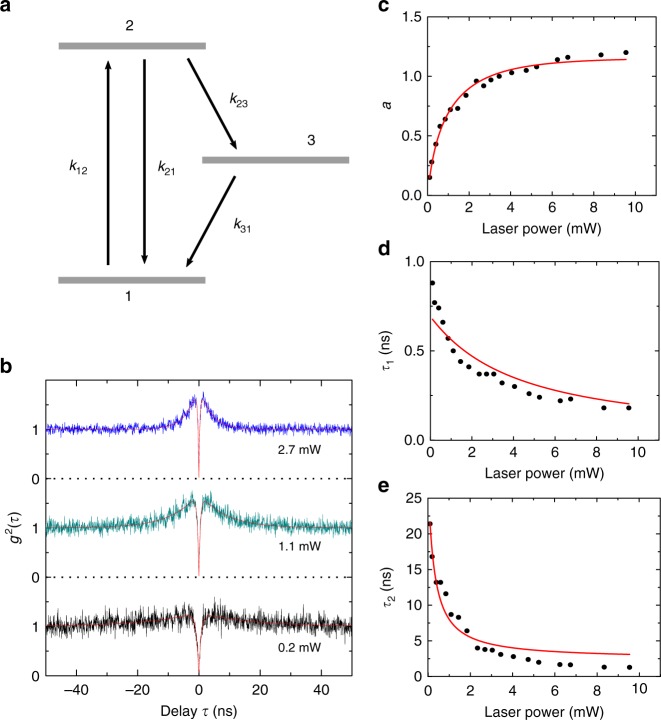

In order to understand more about the energy levels of the emitter, we measure a set of power-dependent autocorrelation functions, which can be modeled by a three-level model. Three representative g2(t) measurement are shown in Fig. 3b. The red lines are the fittings of the data using the equation (1). In the measurement, an obvious power dependence of the photon-bunching effect is observed, which indicates that it has a metastable state18–21. Figure 3a shows a three-level model of the SPEs with ground state |1> , excited state |2> , and metastable state |3> and the pump-power-dependent transition rates, which is similar with other SPEs in SiC18–21. Figure 3c–e shows the fitting parameters a, τ1, and τ2 of the power-dependent g2(t) using the fitting equation (1). The parameters a reveals the bunching, and τ1 reveals the transitions between the ground and excited state, τ2 reflects the behavior of the metastable state.

Fig. 3.

Energy level analysis for SPEs. a Three-level model of the SPEs with ground state |1> , excited state |2> , and metastable state |3> . The parameter k12 is the excitation rate from ground state |1> to excited state |2> , and other kij parameters represent the decay rate from state |i> to |j> , where i, j are number from 1 to 3. b Three representative CW second-order autocorrelation function measurements with different laser excitation powers. The red lines are the fitting using the Eq. (1). c, d, e The fitting parameters a, τ1 and τ2 of the antibunching curve as a function of excitation power. The red lines are the fitting of the data

We fit the parameters using the functions based on three-level rate equation21,29

| 2 |

| 3 |

Where the A = k12 + k21 + k23 + k31, B = k12(k23 + k31) + k31(k21 + k23). The fitting matches with the experimental data relatively well. Moreover, the calculated excited state lifetime, (k21 + k23)−1, 0.7 ± 0.05 ns roughly matches the measured lifetime value 0.81 ± 0.02 ns.

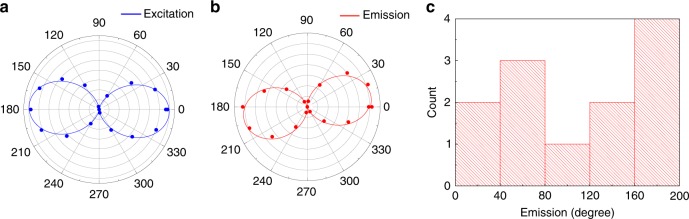

Polarization measurement

To know whether the SPE consists of a single dipole or multiple dipoles, we study the excitation and emission polarization by exciting the emitters using linearly polarized laser. The excitation polarization is measured by rotating a half-wave plate after the polarizer in the excitation path of the confocal set-up while fixing the emission polarization measurements. The measurement of the emission polarization is similar to the method described above, but exchanges the role of excitation and collection arm. Figure 4a and b are the excitation (blue points) and emission (red points) polarization measurements from a SPE, respectively. The data are fitted by the function I = a + bsin2(θ + ϕ), where a ,b, θ, and ϕ are the fitting parameters. The degree of the polarization (η = (Imax − Imin)/(Imax + Imin)) are about 97% and 98% for the excitation and emission polarization, respectively. The degree of both the excitation and emission polarization are larger than 90% for all the studied emitters. These results show that these emitters have single polarizations, which is characteristic of a single linearly polarized dipole transition. Figure 4c displays 12 emitters’ emission axis orientation. There is no obvious preference for the emission dipole directions. The high polarization degree ( > 95%) emission shows that they are well suitable for polarization encoding QKD such as in the Bennett-Brassard protocol.

Fig. 4.

Polarization of the SPEs. a, b The excitation (blue points) and emission (red points) polarization measurements from a SPE. Solid blue red lines are the fitting with I = a + bsin2(θ + ϕ). c Summary of 12 emitters’ emission axis orientation

Nature of the emitters

Finally, we discuss the origin of these emitters. We attribute the SPEs to the same type defect due to the following indicators. The SPEs’ PL spectrum at both room and low-temperature are similar. Moreover, they show similar linear polarization behavior and the matching of a three-level system. In order to confirm that the SPEs are indeed in the 3C-SiC epitaxy layer, three pieces of sample with 1 m epitaxy layer are etched using the reactive ion etching (RIE) to the depths of 200, 300, and 1 µm, respectively. We find that there are single emitters after 200 and 300 nm depth etching. However, no emitters are found after 1 µm etching. This confirms that the SPEs are indeed in the 3C-SiC epitaxy film. Moreover, we also irradiate the samples with 1 Mev electrons at a range of fluences (1015 cm–2 to 5 × 1016 cm–2). Then the sample was annealed under 800 °C in a vacuum at 2 × 10−4 Pa for half an hour. There is no observation of degradation regarding photostability, as well as no changes regarding the PL spectrum center wavelength position and the emitter density (see more in the Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). In addition, we have tested another wafer (2.7 μm epitaxy layer grown on Si substrate from Air Wafer Inc). Similar SPEs have been found (See Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1 for detailed information). These results indicate that the SPEs are intrinsic defects in the 3C-SiC epitaxial layer. The wavelength range of emission suggests that the emitters we discovered represent a type of emitter, which differs from other reported SPEs in 3C-SiC in the visible spectral range19. In the infrared range, one of the SPEs in 3C-SiC is well known and has been characterized: the divacancy defect (so called Ky5/L3 defect)26,27. However, its low-temperature PL spectrum shows a narrow zero phonon lines, which differs from our results. In addition, another major difference is that the saturated counts of Ky5 defect is about 25 kcps19, which is significantly smaller than the one reported here. Based on the fact that our emitters have a variable center wavelength ( ~ 100 nm), we rule out the possibility that strain in the 3C-SiC can induce such big PL shift. Like recently found SPEs in gallium nitride30, our emitters PL variance may be related to stacking faults, which usually present in hetero-epitaxial 3C-SiC layers. The photoluminescence is the result of exciton recombination process of electrons and holes. The hole is tightly localized at the point defect while the electron’s position is loosely localized due to the stacking faults. Thus, the binding energy of the exciton and PL wavelength are determined by the position of the point defect. We have performed PLE measurement by changing the excitation wavelength with the same power and record count rate (Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3). We found that the most efficient excitation wavelength is around 975 nm (1.27 eV) for a SPE whose PL centered at around 1275 nm (0.97 eV). Clearly further investigations are needed in order to exactly identify the defects at the origin of these SPEs.

Discussion

In conclusion, we present the observation of bright RT telecom SPEs in the 3C-SiC epitaxial films grown on silicon substrates. These SPEs are RT photostable and the saturation counts are in the range of ~ Mcps without requiring the formation of photonics structures. It can be expected that by using some photonics structures, such as solid immersion lenses20, nanopillars23, microdisks31,32, and circular bullseye grating33 the emission rate will be further increased. Moreover, the SPEs may also be used for electrically driven single-photon emitting devices28.

Methods

Fitting procedure

In order to fit the power-dependent parameters a, τ1, and τ2 of the g2(t) (Fig. 3c–e), we model the power-dependent rate k12 and k31 as k12 = KP and k31 = (A1/(1 + B1/P) + C), respectively, where A1, B1, C, and K are power-independent and P indicates power. We then optimize the values of A1, B1, C, K, k21, and k23 such that the theoretical model described by Eqs. (1) and (2) fits the power-dependent data. The value of the fitting parameters found are: A1 = 0.15 ± 0.03 GHz, B1 = 2.9 ± 1.1 mW, C = 0.035 ± 0.003 GHz, K = 0.38 ± 0.05 GHz/mW, k21 = 1.22 ± 0.07 GHz, and k23 = 0.22 ± 0.03 GHz. A and B can be expressed by A = 1.475 + 0.38P + 0.15/(1+2.9/P) and B = 0.0836P + (0.057P + 0.216)/(1 + 2.9/P), with the value A and B, τ1 and τ2 deduced by .

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank the discussion with Adam Gali. We acknowledge the support from the Singapore National Research Foundation through a Singapore 2015 NRF fellowship grant (NRF-NRFF2015-03) and its Competitive Research Program (CRP Award No. NRF-CRP14-2014-02), Singapore Ministry of Education (MOE2016-T2-2-077 and MOE2011-T3-1-005), A*Star QTE program and a start-up grant (M4081441) from Nanyang Technological University.

Author contributions

J.W., Y.Z. and Z.W. built the optical set-up and performed the optical measurements. J.W., Y.Z., A.R. and H.J.v.B. performed the data analysis. X.L. and J.Y. performed electron irradiation of the samples. J.W. and W.G. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Junfeng Wang, Yu Zhou.

Contributor Information

Xingji Li, Email: lxj0218@hit.edu.cn.

Hans Jürgen von Bardeleben, Email: vonbarde@insp.jussieu.fr.

Weibo Gao, Email: wbgao@ntu.edu.sg.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-06605-3.

References

- 1.Aharonovich I, Englund D, Toth M. Solid-state single-photon emitters. Nat. Photon. 2016;10:631–641. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2016.186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kok P, et al. Linear optical quantum computing with photonic qubits. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2007;79:135–174. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.79.135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Brien JL, Furusawa A, Vuckovic J. Photonic quantum technologies. Nat. Photon. 2009;3:687–695. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2009.229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lodahl P, Mahmoodian S, Stobbe S. Interfacing single photons and single quantum dots with photonic nanostructures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2015;87:347–400. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.87.347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aspuru-Guzik A, Walther P. Photonic quantum simulators. Nat. Phys. 2012;8:285–291. doi: 10.1038/nphys2253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Georgescu IM, Ashhab S, Nori F. Quantum simulation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2014;86:153–185. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.86.153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris NC, et al. Quantum transport simulations in a programmable nanophotonic processor. Nat. Photon. 2017;11:447–452. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2017.95. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Northup TE, Blatt R. Quantum information transfer using photons. Nat. Photon. 2014;8:356–363. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2014.53. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nilsson J, et al. Quantum teleportation using a light-emitting diode. Nat. Photon. 2013;7:311–315. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2013.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yin J, et al. Satellite-based entanglement distribution over 1200 kilometers. Science. 2017;356:1140. doi: 10.1126/science.aan3211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lo HK, Curty M, Tamaki K. Secure quantum key distribution. Nat. Photon. 2014;8:595–604. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2014.149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beveratos A, et al. Single photon quantum cryptography. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002;89:187901. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.187901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JH, Cai T, Richardson CJ, Leavitt RP, Waks E. Two-photon interference from a bright single-photon source at telecom wavelengths. Optica. 2016;3:577. doi: 10.1364/OPTICA.3.000577. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takemoto K, et al. Quantum key distribution over 120 km using ultrahigh purity single-photon source and superconducting single-photon detectors. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:14383. doi: 10.1038/srep14383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma X, Hartmann NF, Baldwin JKS, Doorn SK, Htoon H. Room-temperature single-photon generation from solitary dopants of carbon nanotubes. Nat. Nanotech. 2015;10:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2015.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He X, et al. Tunable room-temperature single-photon emission at telecom wavelengths from sp3 defects in carbon nanotubes. Nat. Photon. 2017;11:577–582. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2017.119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lohrmann A, Johnson BC, McCallum JC, Castelletto S. A review on single photon sources in silicon carbide. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2017;80:034502. doi: 10.1088/1361-6633/aa5171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castelletto S, et al. A silicon carbide room-temperature single-photon source. Nat. Mater. 2014;13:151–156. doi: 10.1038/nmat3806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castelletto S, et al. Room temperature quantum emission from cubic silicon carbide nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2014;8:7938–7947. doi: 10.1021/nn502719y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Widmann M, et al. Coherent control of single spins in silicon carbide at room temperature. Nat. Mater. 2015;14:164–168. doi: 10.1038/nmat4145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuchs F, et al. Engineering near-infrared single-photon emitters with optically active spins in ultrapure silicon carbide. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7578. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang JF, et al. Efficient generation of an array of single silicon-vacancy defects in silicon carbide. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2017;7:064021. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevApplied.7.064021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radulaski M, et al. Scalable quantum photonics with single color centers in silicon carbide. Nano. Lett. 2016;17:1782–1786. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b05102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lienhard B, et al. Bright and photostable single-photon emitter in silicon carbide. Optica. 2016;3:768. doi: 10.1364/OPTICA.3.000768. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christle DJ, et al. Isolated electron spins in silicon carbide with millisecond coherence times. Nat. Mater. 2015;14:160–163. doi: 10.1038/nmat4144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christle DJ, et al. Isolated spin qubits in SiC with a high-fidelity infrared spin-to-photon interface. Phys. Rev. X. 2017;7:021046. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Falk AL, et al. Polytype control of spin qubits in silicon carbide. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1819. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lohrmann A, et al. Single-photon emitting diode in silicon carbide. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7783. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neu E, et al. Single photon emission from silicon-vacancy colour centres in chemical vapour deposition nano-diamonds on iridium. New J. Phys. 2011;13:025012. doi: 10.1088/1367-2630/13/2/025012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amanuel BM, et al. Bright room-temperature single‐photon emission from defects in gallium nitride. Adv. Mater. 2017;29:12. doi: 10.1002/adma.201605092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radulaski M, et al. Visible photoluminescence from cubic (3C) silicon carbide microdisks coupled to high quality whispering gallery modes. ACS Photon. 2014;2:14–19. doi: 10.1021/ph500384p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lohrmann A, et al. Integration of single-photon emitters into 3C-SiC microdisk resonators. ACS Photon. 2017;4:462–468. doi: 10.1021/acsphotonics.6b00913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li L, et al. Efficient photon collection from a nitrogen vacancy center in a circular bullseye grating. Nano Lett. 2015;15:1493–1497. doi: 10.1021/nl503451j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on request.