Abstract

Twinning is a crystal growth anomaly, which has posed a challenge in macromolecular crystallography (MX) since the earliest days. Many approaches have been used to treat twinned data in order to extract structural information. However, in most cases it is usually simpler to rescreen for new crystallization conditions that yield an untwinned crystal form or, if possible, collect data from non-twinned parts of the crystal. Here, we report 11 structures of engineered variants of the E. coli enzyme N-acetyl-neuraminic lyase which, despite twinning and incommensurate modulation, have been successfully indexed, solved and deposited. These structures span a resolution range of 1.45–2.30 Å, which is unusually high for datasets presenting such lattice disorders in MX and therefore these data provide an excellent test set for improving and challenging MX data processing programs.

Introduction

Twinning is a crystal growth anomaly or lattice disorder in which the crystal is composed of separate domains of differing orientations1. Twinning has posed a challenge in macromolecular crystallography since the earliest days2,3 and multiple computational approaches have been developed in order to treat twinned data in order to extract structural information. Several exhaustive reviews are available that discuss twinning and the methods to address it in detail1,4–7 nevertheless, for clarity, we give here a brief description of this phenomenon. Twinning is characterised by the twin law (a set symmetry operators, which relate the different orientations of the domains); and the twin fractions, αι, that characterise the relative volumes of the twinning domains. There are several types of twinning: merohedral twinning (when the twin operators are a subset of the exact rotational symmetry of the lattice); pseudo-merohedral twinning (when the twin operators approximate the rotational symmetry of the lattice); and non-merohedral twinning or epitaxial twinning (when the twin operators have the rotational symmetry of a sublattice in three or fewer dimensions). In this paper we present examples of pseudo-merohedral twinning.

When there are two twin domains, and the twin operator is a 2-fold rotation, the twinning is called hemihedral twinning. When the twin domains are sufficiently large, the diffracted waves from these domains do not interfere (or interference is negligible, depending on the coherence radius of the beam and twin domain sizes) and the observed intensities are simply the weighted sum of the intensities from each of the individual domains8. If the twin fraction α approaches 0.5 the diffraction pattern acquires an additional symmetry, imposed by the twinning operator, which may lead to erroneous indexing in a higher symmetry space group. If the twin fraction equals 0.5, the crystal is perfectly twinned and the intensity measurements cannot be deconvoluted. If the twin fraction is <0.5 it is possible to deconvolute the data in order to recover the untwinned intensities1. However, errors in the deconvoluted intensities increase proportionally and can become a very large fraction of the intensities as the twin fraction approaches 0.5. Twinning can thus hamper crystal structure determination at all stages, from indexing, to data reduction, phase determination and refinement.

Since the intensities of twin related reflections are correlated, twinning reduces the information content of the data. In the limit case of perfect merohedral twinning that reduction is equivalent to a reduction in the resolution limit by a factor of 1.26. An additional complication is that the statistical properties of the data from twinned and untwinned crystals are different and therefore overall statistics describing model quality such as the Rfactor/Rfree must be interpreted with extra care9. In particular, the gap between Rfactor and Rfree values as well as their individual values needs to be monitored during refinement. If refinement using the twin option leads to an increase of the gap between Rfactor and Rfree, this indicates a serious problem with the refinement protocol and data handling.

Another type of deviation from perfect periodicity in a crystal, is crystal modulation, in which the content of asymmetric unit is not perfectly replicated by the lattice operations and which can occur with a period commensurate or incommensurate with the lattice periodicity. As result of crystal modulation, primary Bragg reflections are flanked by off-lattice satellite reflections10. The direction and magnitude of such satellite reflections is described by an additional vector q, which needs to be added to the reciprocal space vector H to define a 4-dimensional reciprocal space vector. Although incommensurate crystals have been reported rarely in macromolecular protein crystallography11,12, the EVAL software suite can index and process such data10,13, and in silico simulations of modulated structure have been performed14.

In this report we present 11 diffraction data sets, in multiple space groups, from the E. coli enzyme N-acetyl-neuraminic acid lyase (NAL), which present twin lattices and incommensurate modulation. NAL is a tetramer in solution, that crystallises in low salt conditions15 to give four different crystal forms, three in space group P21 and one in P21212115–17. Interestingly, the three crystal forms in space group P21 were not related to each other, two of them were twinned and shared the same twinning operator, which made the monoclinic cells a pseudo-orthorombic cell.

Two of the crystal forms are reported here for the first time, and some were pseudo-merohedrally twinned with the additional complication of incommensurate modulation. Although they could all be solved by molecular replacement, they could not be refined satisfactorily using standard protocols. However, with improvements in REFMAC5, one of the software packages for macromolecular structure refinement available from ccp4 suite 7.018, with direct contribution from the presented test cases, we were able to refine models satisfactorily against all 11 datasets. Due to the varied diffraction data pathologies (pseudo-merohedral twinning with α up to 0.497 as well as crystal modulation) we believe these data form a useful test set for the development of macromolecular crystallographic data processing and structure refinement software and therefore we made them available to the community through the public repository Zenodo (public links in Data Records).

Results and Discussion

Data processing

NAL crystallised in four different crystal forms from the same crystallisation conditions, and in the same drops (100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0–8.2, 200 mM Na acetate, 18–22% w/v PEG3350). It was not possible to discriminate between the four crystal forms of NAL solely by inspection of the crystal morphology (Fig. S1). The most commonly obtained crystal form (I) belonged to space group P21 with unit cell parameters a = 55 Å, b = 142 Å, c = 84 Å, β = 109° (decimals are omitted due to variability between datasets); followed by crystal forms II (a = 84 Å, b = 95 Å, c = 91 Å, α = 90°, β = 116°, γ = 90°) and III (a = 78 Å, b = 108 Å, c = 148 Å, α = 90°, β = 116°, γ = 90°), both in space group P21, and crystal form IV (a = 78 Å, b = 116 Å, c = 84 Å, α = β = γ = 90°) in space group P212121 (Table S1).

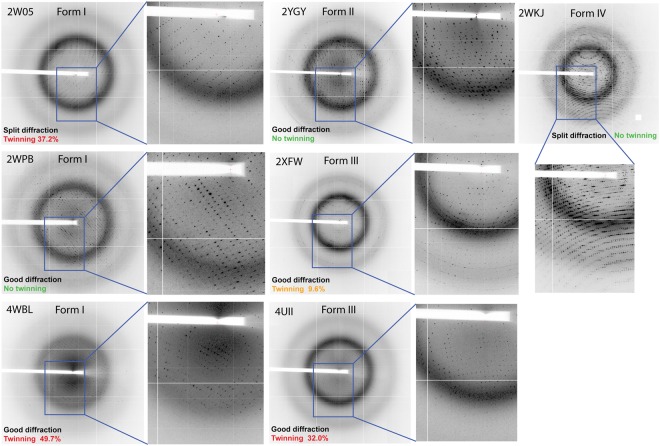

The diffraction patterns occasionally showed spot splitting in all four crystal forms of NAL and it was not possible to predict the successful indexing and scaling outcome based on the observed diffraction quality alone (Fig. 1). The main and satellite reflections are clearly distinct and the main lattice could be indexed separately while satellite reflections were ignored by MOSFLM19 (i.e. PDB 2WNN, 2WPB & 2WKJ, Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Diffraction pattern typologies observed for the crystal forms I, II, III and IV of NAL.

Closer inspection of the diffraction pattern of four of the seven datasets in crystal form I with DIALS viewer20 revealed two lattices but also some extra reflections, which did not belong to either lattices (Fig. S2). MOSLFLM successfully indexed the main lattice in all cases (Table 1), but we decided to further investigate whether these extra reflections in the diffraction pattern could be caused by crystal modulation, as they appeared to be occurring in a periodic manner.

Table 1.

Improvement of refinement statistics upon applying the twin option in REFMAC.

| Datasets | Res | Crystal form and cell parameters |

Obliquity* (ω) |

Twinning fraction* |

Twin on | Twin off |

PDB code |

Diamond Station |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type apo | 2.20 Å | P21 crystal form I a = 54.8 b = 142.2 c = 84.2 α = 90.00 β = 108.97 γ = 90.00 |

0.019 | 0.372 | Rfactor = 0.200 Rfree = 0.267 |

Rfactor = 0.251 Rfree = 0.319 |

2WO5 | I02 |

| Wild type pyruvate complex | 1.65 Å | P21 crystal form I a = 54.7 b = 142.5 c = 83.6 α = 90.00 β = 109.16 γ = 90.00 |

0.070 | 0.334 | Rfactor = 0.201 Rfreev = 0.245 |

Rfactor = 0.256 Rfreev = 0.293 |

2WNN | I03 |

| E192N apo | 1.80 Å | P21 crystal form I a = 54.6 b = 142.8 c = 84.3 α = 90.00 β = 108.8 γ = 90.00 |

0.130 | 0.463 | Rfactor = 0.195 Rfree = 0.244 |

Rfactor = 0.272 Rfree = 0.320 |

2WNQ | I04 |

| E192N pyruvate complex | 1.80 Å | P21 crystal form I a = 56.9 b = 143.0 c = 83.9 α = 90.00 β = 109.8 γ = 90.00 |

0.000 | — | Rfactor = 0.178 Rfree = 0.209 |

Rfactor = 0.187 Rfree = 0.223 |

2WNZ | I02 |

| E192N + pyruvate + THB** | 2.05 Å | P21 crystal form I a = 57.0 b = 143.7 c = 84.3 α = 90.00 β = 109.9 γ = 90.00 |

0.130 | — | Rfactor = 0.192 Rfree = 0.238 |

Rfactor = 0.191 Rfree = 0.242 |

2WPB | I03 |

| Y137A pyruvate complex | 1.80 Å | P21 crystal form I a = 54.7 b = 142.2 c = 83.6 α = 90.0 β = 109.0 γ = 90.0 |

0.119 | 0.149 | Rfactor = 0.287 Rfree = 0.331 |

Rfactor = 0.296 Rfree = 0.357 |

n./a.*** | I04 |

| Y137A pyruvate, ManNAc and Neu5Ac complex | 2.00 Å | P21 crystal form I a = 56.1 b = 143.5 c = 83.6 α = 90.0 β = 109.6 γ = 90.0 |

0.094 | 0.497 | Rfactor = 0.183 Rfree = 0.236 |

Rfactor = 0.265 Rfree = 0.321 |

4BWL | I02 |

| Wild type apo | 1.90 Å | P21 crystal form II a = 84.3 b = 95.9 c = 91.4 α = 90.00 β = 115.33 γ = 90.00 |

2.10 | — | Rfactor = 0.198 Rfree = 0.226 |

Rfactor = 0.197 Rfree = 0.225 |

2YGY | I02 |

| E192N/Y137F pyruvate complex | 1.80 Å | P21 crystal form III a = 78.0 b = 116.7 c = 83.7 α = 90.0 β = 118.06 γ = 90.00 |

0.290 | 0.328 | Rfactor = 0.156 Rfree = 0.183 |

Rfactor = 0.206 Rfree = 0.228 |

2YGZ | I02 |

| E192N + pyruvate complex | 1.85 Å | P21 crystal form III a = 78.1 b = 116.5 c = 83.7 α = 90.00 β = 116.5 γ = 90.00 |

0.150 | 0.096 | Rfactor = 0.165 Rfree = 0.186 |

Rfactor = 0.174 Rfree = 0.193 |

2XFW | I02 |

| E192N + pyruvate | 1.45 Å | P212121 crystal form IV a = 78.3 b = 108 c = 148.3 α = β = γ = 90.00 |

0.000 | — | Rfactor = 0.191 Rfree = 0.201 |

Rfactor = 0.188 Rfree = 0.205 |

2WKJ | I04 |

*As defined in Nespolo et al.,35.

**THB refers to the competitive inhibitor (2 R,3 R)-2,3,4-trihydroxy-N,N-dipropylbutanamide, as reported in Campeotto et al.16. ***Refinement statistics were not of enough quality for model and data deposition, although data analysis was beneficial for the discussion presented here and the raw images were deposited in the public Zenodo database.

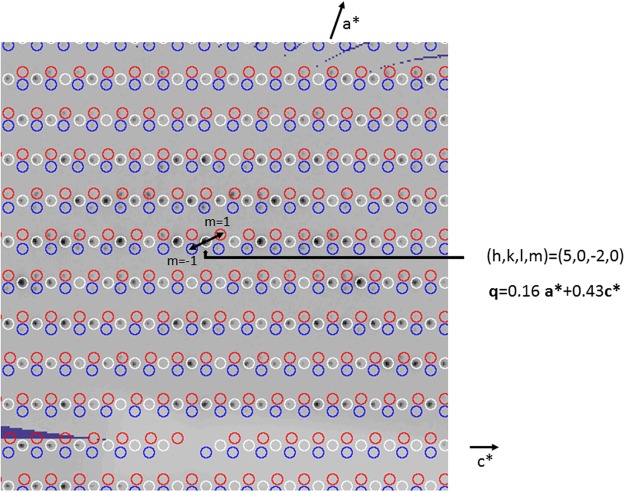

All the datasets in crystal form I were therefore indexed with Dirax21 to determine whether incommensurate modulation was present. This was indeed the case for four of the seven datasets, three of which were deposited in the PDB: 2WNN, 2WNQ, 2W05, whilst one, called Y137A, was not, due to unsatisfactory statistics. In those cases, reflections could be indexed and assigned either to the main lattice or to the satellite reflections with order m = −1 or 1 (see 2WNN as example in Fig. 2). No evidence of splitting of the main lattice was found, implying that the pseudo-merohedral twinned lattices almost exactly overlap. The data were processed with Eval10 and scaled with SADABS22 in 2 /m point group symmetry. The resulting statics are shown in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Precession reconstruction using of reciprocal space slice h0l of 2WNN (with Precession in the EVAL suite). The main lattice is coloured white. Satellite reflections with m = 1 and −1 are coloured red and blue, respectively. Satellites of (5, 0, −2) are indicated by arrows.

Table 2.

Analysis of the presence of crystal modulation in the structures belonging to crystal form I with EVAL15 package for modulated structures.

| Dataset ID | 2WNN | 2WNQ | 2WNZ | 2WO5 | 2WPB | 4BWL | Y137A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bravais | P | P | P | P | P | P | P |

| Pointgroup | 2/m | 2/m | 2/m | 2/m | 2/m | 2/m | 2/m |

| Cell axes a,b,c (Å) | 54.8, 142.8, 83.7 | 54.8, 142.1, 84.5 | 57.4, 143.0, 83.9 | 54.6, 141.9, 84.0 | 56.8, 143.5, 84.2 | 56.1, 143.5, 83.6 | 54.8, 142.4, 83.7 |

| alpha (°) | 90.00, 109.0, 90.00 | 90.00, 108.9, 90.00 | 90.00, 109.9, 90.00 | 90.00, 108.9, 90.00 | 90.00, 109.8, 90.00 | 90.00, 109.6, 90.00 | 90.00, 109.0, 90.00 |

| qvx1* | 0.16 | 0.14 | — | 0.18 | — | — | 0.22 |

| qvy1* | 0.00 | 0.00 | — | 0.00 | — | — | 0.00 |

| qvz1* | 0.43 | 0.42 | — | 0.42 | — | — | 0.42 |

| Resolution (Å) | 41.9-1.65 | 49.9-1.80 | 38.7-1.80 | 48.7-2.20 | 47.8-2.05 | 49.6-1.80 | 49.9-1.80 |

| Rmerge | 0.070 (0.482) | 0.081 (0.643) | 0.059 (0.445) | 0.121 (0.619) | 0.084 (0.367) | 0.088 (1.043) | 0.099 (0.751) |

| Rmeas | 0.083 (0.585) | 0.096 (0.769) | 0.069 (0.543) | 0.144 (0.737) | 0.099 (0.429) | 0.103 (1.217) | 0.119 (0.899) |

| Rpim | 0.044 (0.327) | 0.052 (0.417) | 0.036 (0.307) | 0.077 (0.395) | 0.052 (0.221) | 0.053 (0.623) | 0.064 (0.489) |

| <I/sigI> | 10.6 (1.8) | 8.5 (1.5) | 12.3 (1.8) | 6.8 (2.1) | 9.0 (2.9) | 7.4 (1.0) | 7.8 (1.4) |

| Completeness (%) | 92.0 (61.2) | 97.9 (97.0) | 99.4 (94.6) | 99.9 (99.7) | 98.5 (97.9) | 98.7 (98.0) | 99.8 (98.5) |

| Redundancy | 3.5 (3.2) | 3.4 (3.3) | 3.6 (3.1) | 3.4 (3.4) | 3.6 (3.7) | 3.7 (3.8) | 3.5 (3.4) |

| Reflections | 1358205 (75799) | 1111355 (107314) | 413549 (32220) | 625336 (60979) | 282230 (28483) | 419064 (42200) | 1132807 (108078) |

| Unique | 401726 (26603) | 331525 (32667) | 116035 (11021) | 183588 (18294) | 78040 (7722) | 113330 (11261) | 335150 (33038) |

| Main reflections only | |||||||

| Rmerge | 0.051 (0.340) | 0.053 (0.412) | — | 0.077 (0.362) | — | — | 0.061 (0.503) |

| Rmeas | 0.061 (0.413) | 0.064 (0.492) | — | 0.092 (0.432) | — | — | 0.073 (0.603) |

| Rpim | 0.033 (0.232) | 0.035 (0.267) | — | 0.050 (0.232) | — | — | 0.039 (0.329) |

| <I/sigI> | 12.6 (2.8) | 11.7 (2.5) | — | 8.1 (3.0) | — | — | 8.5 (1.9) |

| Completeness (%) | 91.9 (61.3) | 97.2 (96.6) | — | 99.8 (99.2) | — | — | 99.7 (98.3) |

| Redundancy | 3.5 (3.2) | 3.3 (3.4) | — | 3.4 (3.4) | — | — | 3.4 (3.4) |

| No. Reflections | 447223 (25340) | 354109 (35713) | — | 203706 (20152) | — | — | 373048 (35922) |

Four of the seven datasets were modulated. Statistics may differ slightly from Table 1 due to the processing being performed using a different package.

*q vector components.

All the modulated structures appeared also to be partially twinned (Tables 1 and 2). We speculate that the lack of modulation in 2WNZ and 4BWL is probably due to the larger unit cell axis a, which is large enough not to be incommensurate. With the P21 indexing choice, POINTLESS initially assigned the space group C2221 but reflections belonging to one of the 2-fold axes were much stronger than the others (data not shown), which is consistent with pseudo-merohedral twinning in P21, and indeed with this choice the structures could be easily solved.

However, in all the crystal forms, space group attribution was difficult or sometimes impossible and the choice of the point group was made based on the Rmeas values23. Weak molecular replacement solutions could also be obtained in multiple space groups. As a general rule, whenever only a single lattice with no incommensurate modulation was present, indexing, data reduction and molecular replacement were possible, but the (non-twin) refinement stalled at Rfactor and Rfree values of 30–35% for all datasets (resolution range 1.45–2.3 Å, <I/σ(I)> cut off = 2.0) where we would expect Rfactor values near or below 20% for well-behaved refinements.

Twinning analysis

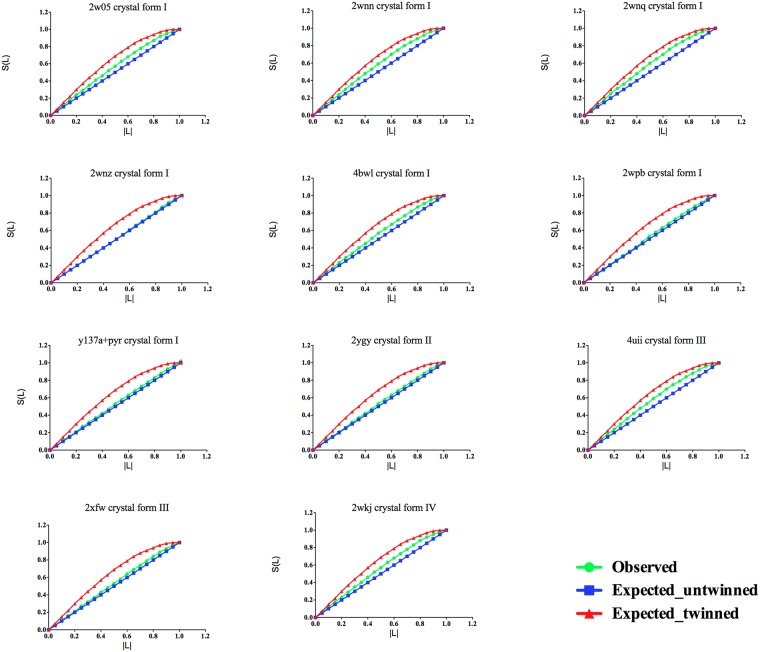

H and L twinning tests, as implemented in TRUNCATE18, were used as diagnostic tools for twinning. In our experience the L-test prediction was more consistent with estimates of twinning fraction performed internally in REFMAC.

This is probably due to the fact that H and L tests are affected by experimental errors and lack discrimination power if one of the NCS-operation axes is parallel to twin-operation axis. However, the H-test requires for data to be merged in correct point group, and even then, in case of the NCS, it may seem to indicate partial twinning for data from single crystal. L-test is free from these two issues. For these reasons only the L-test is reported for the presented datasets (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

L-test analysis of the 11 NAL datasets reported here. For each crystal the crystal form is indicated. Cumulative intensity difference plot of the intensity difference of local pairs of intensities that are not twin-related |L| {L = [I(h 1) − I(h 2)]/[I(h 1) + I(h 2)]} against the cumulative probability distribution N(L) of the parameter L.

Micro-seeding techniques were employed in an attempt to avoid twinning by growing larger single crystals24. However, twinning persisted, suggesting that it was likely to be a nucleation phenomenon, which was perpetuated when twinned seed crystals were used as nuclei. Diffraction data were collected at 100 K following flash cooling of crystals in cryo-protectants, which could have been a source of lattice disorder. Data collection at room temperature from multiple crystals, however, also showed both split diffraction and significant twinning (data not shown), indicating that the disorder pre-existed in the crystals. Ligand soaking experiments were similarly excluded as a cause of the twinning.

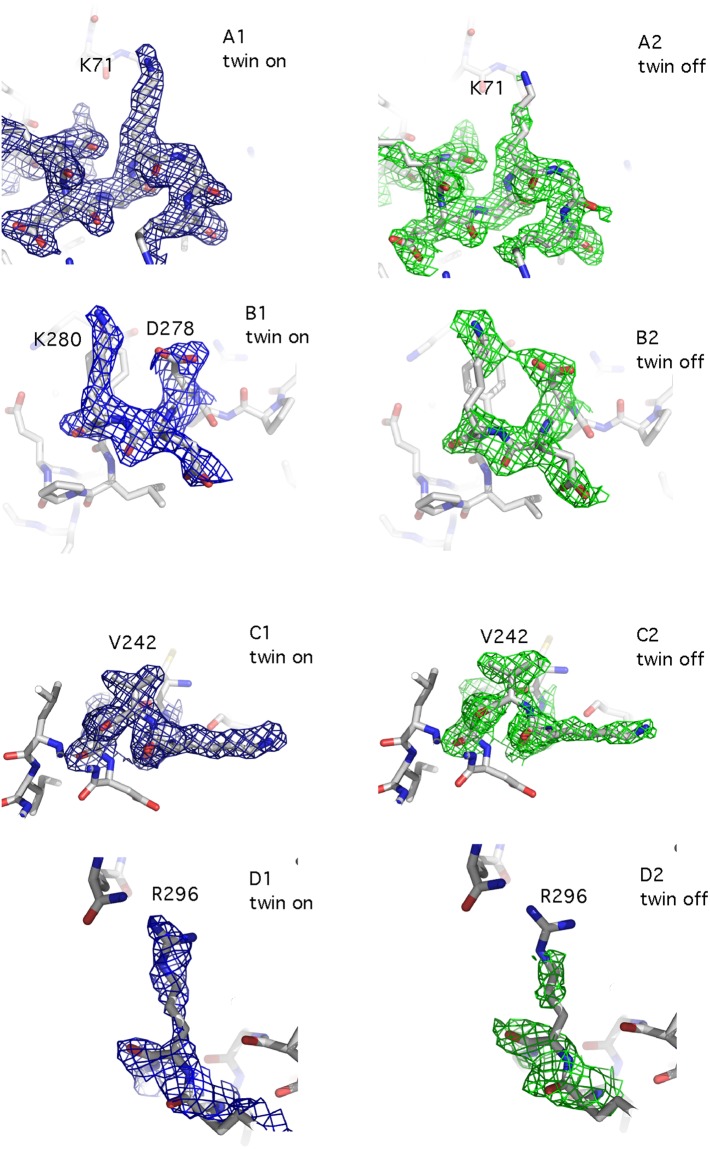

Refinement with the program REFMAC (versions 5.6 and 5.7) identified the twinning operator (−h, −k, h + l) for all the cases, in which twinning was detected. Twin refinement resulted in improved models with Rfactor and Rfree values ~18–20% (Table S2, data collection and final refinement statistics are summarised in Table 1). This improvement of the Rfactor quality indices was accompanied by local improvements of the electron density maps, which became better defined and showed increased connectivity (Fig. 4). The best refined model for each crystal form was validated using ZANUDA18, which confirmed the space group assignment in all cases by transforming the individual space group into the lower symmetry space groups, followed by refinement of the corresponding models using REFMAC and selection of the model with highest symmetry from the ones with best refinement statistics.

Figure 4.

Comparison between equivalent portions of the electron density map before (A1, B1, C1, D1) and after (A2, B2, C2, D2) applying the twin option in REFMAC. The electron density maps refer to different regions of dataset 4BWL, which belongs to crystal form I and showed a twin fraction of almost 50%.

Crystal packing analysis

Zanuda was used to expand the final refined models into space group P1 in order to compare packing in the different crystal forms. Inspection of the packing using the molecular graphics program COOT25 highlighted how not only the inter-monomer contacts within the NAL tetramers were different, but also the inter-tetramer contacts in the crystal lattice (Fig. 5). We speculate that the likelihood of NAL of crystallising in any one of the four forms is determined by small differences in the interfaces between tetramer during nucleation and the early stages of crystal growth. This process is kinetically and thermodynamically difficult to control and attempts to select for a specific crystal form were hindered by the fact that all four forms were obtained in the same crystallisation drops and therefore from identical crystallisation conditions. Surface accessible areas and free energies of interaction were calculated using PISA (Table 2)26. These did not show any significant differences in the strength of intra-tetramer interactions between the different crystal forms, consistent with our observation that all four crystal forms appeared in the same crystallisation drops.

Figure 5.

Crystal packing and crystal contacts in the four crystal forms of NAL. For each crystal form the crystal packing was inspected manually and the least overlapping orientation is presented as 2D layer (A1, B1, C1 and D1). The crystal contacts between tetramers in the given orientation are represented in more detail (A2, B2, C2, D2) as a red surface with the orientations of the tetramers kept the same as in the corresponding 2D layer. As examples of crystal forms I, II, III and IV, the structures of PDB code 2WNN, 2YGY, 2XFW and 2WKJ are represented respectively. Images were produced in PYMOL version 1.6.0.0.

Future developments

The presented datasets were the result of an extensive screening at the data collection stage and of an extensive processing at the data reduction and data refinement stages with very low success rate (Fig. S3). The development of twin refinement in REFMAC, which at the time was only implemented in the experimental version of the program, allowed the determination of several apo- and ligand bound structures of NAL and the proposal of the first detailed mechanism of the enzyme reaction15,16. Although twin refinement is currently included in REFMAC, the presented datasets are still a challenging test for current indexing and scaling programs, including iMosflm, LABELIT27 and XDS28, and they therefore offer an excellent opportunity for the development of these softwares.

Several improvements in MX software are still very desirable in the part of dealing with pathological data. This includes robust diagnostics and warning messages, automated space group assignment in at least obvious cases of twinning, and, importantly, robust integration of partially overlapping reflections and communication of all the necessary data and metadata to a refinement program. Crystal modulation was also detected only after structure deposition and although this had no effect on data processing in the presented cases, its diagnosis should be implemented to avoid reflection overlaps, which in severe cases can seriously hamper indexing, data reduction and ultimately phasing and satisfactory refinement.

Methods

Data collection and structure solution

We have previously reported several structures of wild type NAL and engineered variants and NAL crystals were obtained as previously described15,16. NAL crystals are plate-shaped and tend to grow in clusters and therefore micro-seeding experiments were required to obtain single large crystals. Crystal cryo-protection was achieved by serial transfer of the crystals through mother liquor containing 20% and then 25% v/v PEG 400, with 2 minutes soak time at each step. Eleven datasets were collected from single crystals at Diamond Light Source (beamlines I02, I03 and I04), at 100 K with a 1 s exposure and an oscillation of 0.5° per image and using a Q315 ADSC CCD detector. Data were processed using iMOSFLM and scaled and merged using SCALA29.

In the case of the datasets of crystal form I, diffraction patterns were inspected with DIALS20 for the presence of satellite reflection, indexed with Dirax22 and processed with EVAL1510. Scaling was performed with SADABS in 2/m point group symmetry. The results are shown in Table 2. For structure refinement only the main lattice reflections from MOSFLM were used, ignoring the weak satellite reflections.

In each dataset five percent of the reflections were excluded from the refinement and constituted the Rfree set. A new Rfree set was generated randomly for each new crystal form and then transferred to all datasets belonging to the same crystal form.

The first crystal structure obtained for each crystal form was solved by molecular replacement using PHASER30 and 1NAL as a starting model31, while refinement against other datasets of the same crystal form started with 20 cycles of rigid body refinement (resolution range 10.0–6.0 Å) followed by 10 cycles of preliminary restrained refinement (whole resolution range) in REFMAC5.

Refinement and Crystal packing analysis

Refinement was performed using REFMAC 5.6 or 5.7 (i.e. the latest version at the time of deposition or final refinement for each structure), with and without twin refinement, both for electron density calculations and evaluation of statistics. Refinement was performed with the same settings for all reported structures, i.e. 20 cycles per run (using the whole resolution range of the data), a weight matrix of 0.132, with riding hydrogen atoms.

For all structures involved, regardless of whether the unit cell parameters allowed for twinning by merohedry or not, the refinement protocol was identical and included twin-refinement in the final refinement rounds32. If no twinning operations are present, the twin refinement option means that REFMAC uses approximation to the likelihood target rather than its exact version. Such usage therefore only makes sense for comparison of refinement results for twinned and untwined crystals.

Rfactor and Rfree values were compared before and after twin refinement.

The values of the obliquity angle, which are a measure of pseudo-symmetry, were monitored and manual inspection of the diffraction pattern were performed with ADXV33.

The concept of obliquity is a measure of the overlap of lattices on the individuals forming a twin and Friedel provided a formal mathematical description since the early day of crystallography34. Briefly, the closest is the obliquity angle to zero, the more likely is the presence of merohedral twinning35, as the two twin lattices tend to overlap. Values of obliquity close to zero are, however, only a possible indicator that twinning may be present but not a fixed rule, as some of the presented datasets highlight. For instance, in the case of crystal form I and III, the obliquity angle is small enough to allow twinning in some cases, whilst in crystal form II is too large for twinning to occur (Table 1).

Manual model building was performed in COOT. Zanuda was used to expand the unit cell of each crystal form into P1 for each crystal form and these were refined against the data processed in P1 in order to confirm the correctness of the space group assignment in each case.

In order to assess how the four crystal forms of NAL were related to each other, Csymmatch from CCP4 was used to bring all the P1-expanded structures to the same origin and NCONTACT18 was used to calculate inter-tetramer contacts. The input file from NCONTACT was used in PYMOL to visualise the contact surface between monomers. Surface accessibility areas and crystal contact energy were calculated using PISA26 (Table S3).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

ARP was supported by a RCUK Academic Research Fellowship, and currently by the German Federal Excellence Cluster “Hamburg Centre for Ultrafast Imaging”. AL is supported by CCP4, GNM is supported by MRC grant (no MC_US_A025_0104) and IC was supported by the Wellcome Trust PhD programme, “The Molecular Basis of Biological Mechanisms”. We thank the MX beamline staff at Diamond Light Source for assistance with data collection and Diamond Light Source for access to beamlines i02, i03 and i04 (proposal number mx 302) for diffraction data collection.

Author Contributions

I.C. purified the protein, grew crystals, collected and processed the data, solved and deposited the structures and wrote the paper. A.L. provided advice for the refinement of the structures. L.K.-B. and A.S. analysed the datasets affected by crystal modulation, whilst E.L. provided advice for DIALS. S.E.V.P. supervised the research with A.R.P. A.R.P. also supervised data analysis, structure validation and deposition, and wrote the paper with I.C., G.N.M. developed some novel features of REFMAC for dealing with twinned data using some of the presented structures. All the authors contributed to the paper.

Data Records

The datasets (raw diffraction images) discussed in this manuscript have been deposited in the publicly available database zenodo at, https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.54568 and 10.5281/zenodo.1240503. Structural models and processed structure factor data deposited in the PDB are available under the accession codes given in Table 1, with the exception of dataset Y137A, as the R factor indices were not satisfactory for PDB deposition.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ivan Campeotto, Email: ivan.campeotto@leicester.ac.uk.

Arwen R. Pearson, Email: arwen.pearson@cfel.de

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-32962-6.

References

- 1.Yeates TO. Detecting and overcoming crystal twinning. Methods in enzymology. 1997;276:344–358. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.BERNAL J. D., FANKUCHEN I., PERUTZ MAX. An X-Ray Study of Chymotrypsin and HÆmoglobin. Nature. 1938;141(3568):523–524. doi: 10.1038/141523a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blow DM, Rossmann MG, Jeffery BA. The Arrangement of Alpha-Chymotrypsin Molecules in the Monoclinic Crystal Form. Journal of molecular biology. 1964;8:65–78. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(64)80149-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dauter Z. Twinned crystals and anomalous phasing. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2003;59:2004–2016. doi: 10.1107/S0907444903021085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helliwell JR. Macromolecular crystal twinning, lattice disorders and multiple crystals. Crystallography reviews. 2008;14:189–250. doi: 10.1080/08893110802360925. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parsons S. Introduction to twinning. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2003;59:1995–2003. doi: 10.1107/S0907444903017657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zwart PH, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Lebedev AA, Murshudov GN, Adams PD. Surprises and pitfalls arising from (pseudo)symmetry. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2008;64:99–107. doi: 10.1107/S090744490705531X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grainger CT. Pseudo-merohedral twinning. The treatment of overlapped data. Acta Crystallographica Section A. 1969;A25:427–434. doi: 10.1107/S0567739469000866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murshudov, G. N. Some statistical properties of the crystallographic reliability index Rfactor: Effect of twinning. Applied and Computational Mathematics, 250–261 (2011).

- 10.Porta J, Lovelace JJ, Schreurs AM, Kroon-Batenburg LM, Borgstahl GE. Processing incommensurately modulated protein diffraction data with Eval15. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2011;67:628–638. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911017884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lovelace JJ, et al. Protein crystals can be incommensurately modulated. Journal of applied crystallography. 2008;41:600–605. doi: 10.1107/S0021889808010716. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rupp B, Marshak DR, Parkin S. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of two new crystal forms of calmodulin. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 1996;52:411–413. doi: 10.1107/S0907444995011826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schreurs MMA, Xian X, Kroon-Batenburg JML. EVAL15: a diffraction data integration method based on ab initio predictied profile. J. Appl. Cryst. 2010;43:70–82. doi: 10.1107/S0021889809043234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lovelace JJ, Simone PD, Petricek V, Borgstahl GE. Simulation of modulated protein crystal structure and diffraction data in a supercell and in superspace. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2013;69:1062–1072. doi: 10.1107/S0907444913004630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campeotto I, et al. Structure of an Escherichia coli N-acetyl-D-neuraminic acid lyase mutant, E192N, in complex with pyruvate at 1.45 angstrom resolution. Acta crystallographica. Section F, Structural biology and crystallization communications. 2009;65:1088–1090. doi: 10.1107/S1744309109037403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campeotto I, et al. Structural insights into substrate specificity in variants of N-acetylneuraminic Acid lyase produced by directed evolution. Journal of molecular biology. 2010;404:56–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daniels AD, et al. Reaction mechanism of N-acetylneuraminic acid lyase revealed by a combination of crystallography, QM/MM simulation, and mutagenesis. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:1025–1032. doi: 10.1021/cb500067z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Battye TG, Kontogiannis L, Johnson O, Powell HR, Leslie AG. iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2011;67:271–281. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910048675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winter G, et al. DIALS: implementation and evaluation of a new integration package. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol. 2018;74:85–97. doi: 10.1107/S2059798317017235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duisenberg AJM. Indexing in Single-Crystal Diffractometry with an Obstinate List of Reflections. J. AppL Cryst. 1992;25:92–96. doi: 10.1107/S0021889891010634. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krause L, Herbst-Irmer R, Sheldrick GM, Stalke D. Comparison of silver and molybdenum microfocus X-ray sources for single-crystal structure determination. Journal of applied crystallography. 2015;48:3–10. doi: 10.1107/S1600576714022985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roversi P, Blanc E, Johnson S, Lea SM. Tetartohedral twinning could happen to you too. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2012;68:418–424. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912006737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bergfors T. Seeds to crystals. J Struct Biol. 2003;142:66–76. doi: 10.1016/S1047-8477(03)00039-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. Journal of molecular biology. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sauter NK, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD. Robust indexing for automatic data collection. Journal of applied crystallography. 2004;37:399–409. doi: 10.1107/S0021889804005874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kabsch Wolfgang. XDS. Acta Crystallographica Section D Biological Crystallography. 2010;66(2):125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans P. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2006;62:72–82. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. Journal of applied crystallography. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Izard T, Lawrence MC, Malby RL, Lilley GG, Colman PM. The three-dimensional structure of N-acetylneuraminate lyase from Escherichia coli. Structure. 1994;2:361–369. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(00)00038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murshudov GN, et al. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2011;67:355–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arvai, A. ADXV - a program to display X-ray diffraction images, http://www.scripps.edu/~arvai/adxv.html. (2012).

- 34.Donnay, J. D. H. a. D., G. International Tables for X-ray Crystallography. Birmingham: Kynoch PressIII (1959).

- 35.Nespolo M, Ferraris G. Overlooked problems in manifold twins: twin misfit in zero-obliquity TLQS twinning and twin index calculation. Acta crystallographica. Section A, Foundations of crystallography. 2007;63:278–286. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307012135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets (raw diffraction images) discussed in this manuscript have been deposited in the publicly available database zenodo at, https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.54568 and 10.5281/zenodo.1240503. Structural models and processed structure factor data deposited in the PDB are available under the accession codes given in Table 1, with the exception of dataset Y137A, as the R factor indices were not satisfactory for PDB deposition.