Abstract

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is associated with impairments in relationship functioning. Beyond the abundance of research that has demonstrated this basic link, more recent research has begun to explore possible mediators and moderators of this association. The present paper reviews and synthesizes existing literature in the context of an overarching organizational framework of potential ways in which PTSD impacts relationship functioning. The framework organizes findings in terms of specific elements of PTSD and comorbid conditions, mediators (factors that are posited to explain or account for the association), and moderators (factors that are posited to alter the strength of the association). Specific symptoms of PTSD, comorbid symptoms, and many of the potential mediators explored have extensive overlap, raising questions of possible tautology and redundancy in findings. Some findings suggest that nonspecific symptoms, such as depression or anger, account for more variance in relationship impairments than trauma-specific symptoms, such as re-experiencing. Moderators, which are characterized as individual, relational, or environmental in nature, have been the subject of far less research in comparison to other factors. Recommendations for future research and clinical implications of the findings reviewed are also presented.

Keywords: posttraumatic stress disorder, PTSD, marriage, relationship, spouse

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a multifaceted disorder resulting from intense and/or life-threatening trauma (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – 5th edition [DSM-5]; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). In addition to the individual psychological distress associated with the disorder, PTSD is frequently associated with relationship distress in one or both partners in a romantic relationship. Two recent meta-analyses have confirmed such associations for both those with PTSD (ρ = .38; Taft Watkins, Stafford, Street, & Monson, 2011) and their partners (r = .24; Lambert, Engh, Hasbun & Holzer, 2012), and some researchers have begun to focus on involving romantic partners in PTSD treatment (e.g., Monson et al., 2012). Thus, there is a need for a more comprehensive understanding of the specific ways in which romantic relationships affect and are affected by PTSD.

Relationship functioning is a broad construct that encompasses the overall health of a relationship. It includes broad indices, such as relationship satisfaction and distress, as well as more specific constructs, such as communication behaviors, degree of perceived alliance, and extent of mutual trust. Research examining how PTSD symptoms might be associated with a variety of such constructs has grown exponentially, and researchers have also developed several conceptual models of the effects of trauma/PTSD on relationships. Nelson Goff and Smith (2005) proposed the Couple Adaptation to Traumatic Stress (CATS) model, which was based in systems theory and posited that trauma affects survivors and their partners both individually and as a couple. The authors also suggested several processes by which individual and couple-level factors might be reciprocally associated, but they cited limited empirical evidence for them. Monson, Fredman, and Dekel (2010) proposed the Cognitive Behavioral Interpersonal (CBI) model, which also asserts bidirectional associations among individual and couple-level factors and focuses primarily on cognitions, behaviors, and emotions. Most recently, Marshall and Kuijer (2017) proposed the Dyadic Responses to Trauma (DRT) model, which hypothesizes that event interpretation and coping styles lead to specific psychological responses that, in turn, impact relationship processes. Each of these models captures the importance of considering both partners and proposes a set of specific individual and couple-level factors as key mechanisms of action. In each case, however, only varying levels of empirical evidence are cited, and several existing findings are left unaddressed.

In our review, rather than specifying a model and including only findings that fit the model, we attempt to organize the vast array of identified findings into a single, overarching framework. By doing so, we seek to highlight factors that are likely key in understanding the links between PTSD and relationship functioning, while also noting primary limitations and gaps in the literature. We hope that this review will serve as a guide for future research from a wide range of theoretical orientations, as well as a basis for evaluating the degree to which future contributions move our knowledge forward.

Method

Although we did not endeavor to conduct a meta-analysis, we ensured a thorough review by trying to identify all possibly relevant articles through a multi-step process. Using PsycInfo and Google Scholar to search articles through October 2017, we entered a combination of the keyword “PTSD” with each of the following: “relationship distress,” “relationship satisfaction,” “relationship quality,” “relationship adjustment,” marital distress,” “marital satisfaction,” “marital quality,” “marital adjustment” and “mechanisms.” We restricted our search to peerreviewed articles and chapters in English-language publications, which yielded well over 1,000 articles. Abstracts for all articles were searched to screen out those that were clearly irrelevant. The several hundred remaining articles were reviewed to identify those that met the following criteria: 1) use of a defined method for assessing of PTSD in trauma survivors (either for inclusion in the study or included in model tested), 2) use of quantitative analysis, and 3) some form of testing of a potential mediator or moderator of the association of PTSD and relationship functioning. The reference sections of all identified relevant publications were then reviewed for additional references, and further searches were performed for additional works by the first authors of identified relevant publications. Although most articles identified in this manner were repeats of articles we had already identified, we reviewed the few new articles that arose from those search methods in the same manner.

Overarching Framework

Attempts to distinguish causal pathways within the field typically raise more questions than answers – but without such attempts, testable hypotheses are difficult to generate and evaluate. Rather than summarizing findings and noting all possible permutations of pathways among various associations, we provide a framework for considering how PTSD symptoms may cause or exacerbate relationship problems, based on the literature reviewed. There is ample research to suggest alternative directions of causality, such as relationship problems increasing the likelihood of developing PTSD following trauma exposure (e.g., Dirkzwager, Bramsen, & van der Ploeg, 2003) and decreasing PTSD treatment response (e.g., Evans, Cowlishaw, Forbes, Parslow, & Lewis, 2010). Such findings are mounting (e.g., Leblanc et al., 2016) and highlight the bidirectional nature of associations between PTSD symptoms and relationship problems. Although there may be some overlap in factors that influence associations in both directions, many pathways by which PTSD leads to relationship problems may differ from those by which relationship problems lead to PTSD. To answer such questions requires prospective data, ideally from time periods that predate the experience of trauma and onset of PTSD, but at least starting at the onset of trauma. The limited data of this nature suggest that, shortly after a trauma, interpersonal problems contribute to the development of PTSD, whereas over time, PTSD symptoms appear to drive interpersonal difficulties (Hall, Bonanno, Bolton, & Bass, 2014; Kaniasty & Norris, 2008; Robinaugh et al., 2011; Shallcross, Arbisi, Polusny, Kramer, & Erbes, 2016; but see Fredman et al., 2017). As the preponderance of existing research focuses on couples in which one partner already has PTSD, we have little information on how relationship problems might contribute to the development of PTSD. Thus, our review focuses on processes by and conditions under which PTSD might lead to relationship problems.

In line with this focus, we differentiate specific symptoms of PTSD and related conditions from two other broad types of constructs: mediators and moderators. We use the conceptual meaning of these terms, as described in Baron and Kenny’s (1986) seminal writing on the topic. Thus, the term mediator refers to any factor that may be caused by PTSD symptoms and, in turn, lead to impaired relationship functioning. True empirical evidence demonstrating this step-by-step causal pathway is rarely available. Indeed, even longitudinal studies that allow for evaluation of pathways over time are rare. Thus, we use findings from cross-sectional and (less frequently) longitudinal studies to inform our framework (cf. Hayes & Rockwood, 2017). Ultimately, however, longitudinal research is needed to truly evaluate possible causal pathways. The other term, moderator, refers to any contextual variable that may alter the strength of the association between PTSD and relationship functioning at differing levels of that variable. To date, little empirical research has evaluated moderation of the association of PTSD with relationship functioning. The few studies in this area focus on individual-level constructs in trauma survivors or their partners, with little attention to relationship-level or environmental moderators of this association.

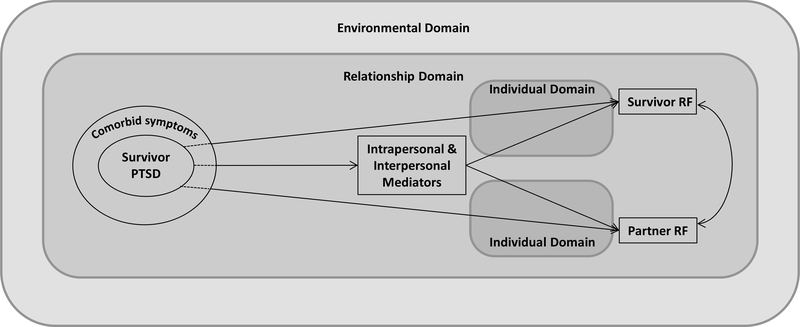

Our organizational framework is shown in Figure 1. Below, we review findings with regard to each piece of this framework. We then propose recommendations for future research, based on both limitations of existing research and elements of the proposed framework lacking empirical evidence. We conclude with potential clinical implications of the findings reviewed.

Figure 1.

Organizational framework for findings related to how PTSD impacts relationship functioning. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; RF = relationship functioning.

Specific Elements of Psychopathology

PTSD Symptom Clusters

PTSD is defined in terms of symptom clusters. The DSM-IV (APA, 1994) defined three clusters: re-experiencing (e.g., reactivity to trauma-related stimuli, flashbacks of the trauma), avoidance (e.g., avoidance of trauma-related stimuli, emotional numbing), and hyperarousal (e.g., irritability, hypervigilance). Subsequent empirical research (e.g., King, Leskin, King, & Weathers, 1998) suggested that the avoidance cluster could be broken further into effortful avoidance (avoidance of trauma-related stimuli) and emotional numbing (more general symptoms of numbing and withdrawal). In the DSM-5 (APA, 2013), the avoidance cluster was separated into effortful avoidance and negative alterations in cognitions/mood (which included emotional numbing, as well as some symptoms that were not previously in the DSM-IV).

Several studies have evaluated the simultaneous, multivariate associations of PTSD symptom clusters with relationship functioning. Such an approach does not speak to mediation per se, but rather, to the relative variance in relationship functioning that is uniquely accounted for by specific components of PTSD symptomatology. In interpreting these results, it is important to acknowledge that, in almost all studies, each individual symptom cluster shares a significant, negative bivariate association with indices of relationship functioning (e.g., Evans, Cowlishaw, Forbes, Parslow, & Lewis 2010). Also, given the high intercorrelation of symptom clusters, these multivariate analyses suffer from high multicollinearity. Despite these limitations, some clear patterns of findings have emerged, and researchers frequently draw conclusions about the clinical importance of specific clusters based on results of multivariate analyses. Thus, these studies represent an important subset of the existing literature.

Multivariate analyses (i.e., simultaneous inclusion) of the three clusters from the DSM-IV model consistently indicate that the avoidance cluster exerts the clearest multivariate association with relationship functioning, with small to medium effect sizes (Evans, Cowlishaw, Forbes, Parslow, & Lewis 2010; Evans, Cowlishaw, & Hopwood, 2009; Evans, McHugh, Hopwood, & Watt, 2003; Solomon, Debby-Aharon, Zerach, & Horesh, 2011; Solomon, Dekel, & Zerach, 2008; but see Hamilton, Nelson Goff, Crow, & Riesbig, 2009; Hendrix, Erdmann, & Briggs, 1998). Findings from studies that used separate effortful avoidance and emotional numbing clusters further indicate that emotional numbing demonstrates the strongest association with relationship functioning, with effortful avoidance usually demonstrating nonsignificant associations in these analyses (Beck, Grant, Clapp, & Palyo, 2009; Cook, Riggs, Thompson, Coyne, & Sheikh, 2004; Erbes, Meis, Polusny, Compton, & MacDermid Wadsworth, 2012; Lunney & Schnurr, 2007; Renshaw & Campbell, 2011; Renshaw, Allen, et al., 2014; Riggs, Byrne, Weathers, & Litz, 1998; Taft, Schumm, Panuzio, & Proctor, 2008; but see Erbes, Meis, Polusny, & Compton, 2011). Finally, one group of researchers has studied a model of PTSD symptom clusters termed the dysphoria model, which combines emotional numbing symptoms with symptoms of general distress from the arousal cluster (irritability, difficulty sleeping, difficulty concentrating). The two studies using this conceptualization have revealed that the dysphoria cluster accounts for the most variance in relationship functioning in multivariate analyses with all symptom clusters (Erbes et al., 2011, 2012). Of note, no study using updated DSM-5 criteria was published during our search period.

When simultaneously evaluating all symptom clusters, several individual and dyadic studies have failed to find a significant, direct association between hyperarousal symptoms and relationship variables (Cook, et al., 2004; Erbes et al., 2011, 2012; Evans et al., 2003; Lunney & Schnurr, 2007; Riggs et al., 1998). On the other hand, three veteran self-report studies (Evans et al., 2009; Solomon et al., 2011; Taft et al., 2008) and four dyadic studies (Evans et al., 2010; Hamilton et al., 2009; Hendrix et al., 1998; Renshaw, Campbell, Meis, & Erbes, 2014) revealed significant negative associations between hyperarousal and relationship functioning both cross-sectionally and longitudinally, whereas two multivariate cross-sectional studies have found a small positive association of hyperarousal symptoms with relationship functioning (Beck et al., 2009; Solomon, Dekel, & Zerach, 2008). Thus, most studies seem to suggest a null or negative association, but evidence is mixed. Finally, most analyses indicate that re-experiencing symptoms are not significantly associated with relationship functioning when accounting for the other PTSD clusters (Beck et al., 2009; Cook et al., 2004; Erbes et al., 2011; Erbes et al., 2012; Evans, McHugh, Hopwood, & Watt, 2003; Lunney & Schnurr, 2007; Riggs et al., 1998; Solomon, Dekel, & Zerach, 2008; Taft et al., 2008), although three studies detected negative associations (Evans et al., 2010; Hamilton et al., 2009; Solomon et al., 2011), and one revealed a positive association (Erbes et al., 2011).

In sum, the results of these studies reveal that, when all PTSD symptom clusters are evaluated simultaneously, the symptoms of emotional numbing have the most consistently negative association with relationship functioning. The hyperarousal cluster demonstrates a less consistent but typically negative association with relationship functioning, and re-experiencing shows little consistent association when controlling for other types of symptoms. These findings suggest that non-specific symptoms (emotional numbing, hyperarousal) account for greater variance in relationship functioning than do trauma-specific symptoms (re-experiencing and effortful avoidance), when all symptoms are examined simultaneously. These findings conflict with some anecdotal reports, for instance regarding the negative impact of effortful avoidance on relationships (e.g., Makin-Byrd, Gifford, McCutcheon, & Glynn, 2011; Monson et al., 2010; Sautter, Glynn, Cretu, Senturk, & Vaught, 2015). However, this pattern is consistent with findings related to relatives of individuals with schizophrenia. In studies of such relatives, it is the more diffuse negative symptoms (e.g., avolition) rather than overt positive symptoms (e.g., hallucinations) that are significantly associated with relationship distress (Hooley, Richters, Weintraub, & Neale, 1987). Hooley and colleagues interpreted these findings to reflect the more ambiguous nature of negative schizophrenia symptoms, in contrast with symptoms like hallucinations, which are more clearly illness-based. In the context of PTSD, re-experiencing and effortful avoidance are explicitly tied to trauma reminders, whereas symptoms of emotional numbing and hyperarousal may be more diffuse and not clearly linked to the trauma (Renshaw & Caska, 2012; Renshaw, Allen et al., 2014).

It is important to acknowledge that all types of symptoms have significant, bivariate associations with relationship functioning. Moreover, the more general symptoms of PTSD (e.g., difficulty concentrating) may be intrinsically tied to trauma-specific symptoms (e.g., intrusive thoughts). Thus, these results do not suggest that attending to symptoms like re-experiencing is unnecessary when attempting to address relationship difficulties. They do suggest that more general symptoms may be more directly associated with relationship impairment than symptoms that are trauma-specific.

In addition, the pattern of findings is consistent with broader research on relationship functioning, which suggests that deficits in positive affect and behavior account for more variance in relationship functioning than excesses of negative affect and behavior, both cross-sectionally and longitudinally (e.g., Gottman & Levenson, 2000; Laurenceau, Troy, & Carver, 2005; Pasch & Bradbury, 1998; Smith, Vivian, & O’Leary, 1990). Symptoms such as emotional numbing and interpersonal withdrawal mirror deficits of positive affect and behavior in the context of romantic relationships. Thus, the pattern of findings from multivariate analyses of PTSD symptom clusters is consistent with findings from the broader relationship literature.

Comorbid Psychopathology

Depression, anger, and aggression are the most commonly explored co-occurring psychological symptoms in the link between PTSD and relationship functioning. Some research exists to suggest that PTSD may be more predictive of subsequent depression than the opposite pathway (review by Stander, Thomsen, & Highfill-McRoy, 2014), but such pathways are not yet clear. Moreover, studies of PTSD and relationship functioning that have included constructs such as depression or anger have largely been cross-sectional in nature, prohibiting evaluation of temporal precedence among the variables. In multivariate analyses of the simultaneous contributions of PTSD symptoms and depressive symptoms to relationship functioning, symptoms of depression have been found to account for more variance than survivors’ PTSD symptoms in both survivors’ and partners’ relationship functioning (Beck et al., 2009; Evans et al., 2003; but see Nelson Goff, Crow, Reisbig, & Hamilton, 2007). In evaluating the simultaneous prediction of marital satisfaction by PTSD and aggression, Dekel and Solomon (2006a, 2006b) found that both PTSD symptoms and aggression were significant for combat veterans (2006a) and their wives (2006b). In contrast, other studies that have used path analysis to test direct and indirect (via anger or aggression) effects of PTSD on relationship functioning have generally found that aggression and perceptions of threat of violence partially or fully mediate the association of PTSD symptoms with relationship functioning (Brown et al., 2012; Dekel et al., 2008; Solomon, Dekel, & Zerach, 2008). In sum, findings are somewhat mixed, but the preponderance of evidence suggests that symptoms of depression and anger account for equal or greater variance in relationship functioning, relative to symptoms of PTSD.

One issue that this set of studies brings to the forefront is the overlap of constructs and possible tautologies in this area. Symptoms of depression, anger, and aggression have extensive overlap with symptoms of PTSD (e.g., Stander, Thomsen, & Highfill-McRoy, 2014), and they may even reflect manifestations of symptoms of emotional numbing and hyperarousal. Thus, separating these types of symptoms out from the broader construct of PTSD is, in some ways, impossible, meaning that the associations reviewed above may not necessarily reflect mediation, even if formal mediational analyses were conducted.

Mediators

Intrapersonal Constructs

Greater PTSD severity has been linked with avoidant attachment in both survivors (meta-analysis by Woodhouse, Ayers, & Field, 2015) and partners (Ein-Dor, Doron, Solomon, Mikulincer, & Shaver, 2010; Gallagher et al., 2017). PTSD has also been associated with anxious attachment in survivors (e.g., Busuito et al., 2014; Franz et al., 2014; Ogle, Rubin, & Siegler, 2016; Renaud, 2008; Solomon et al., 2008) but not in partners (Ein-Dor et al., 2010). Although some researchers have pointed to attachment as a critical consideration in the link between PTSD and relationship functioning (e.g., Johnson & Williams-Keeler, 1998), no empirical research has explicitly investigated attachment as a mediator in this link.

In studies using formal mediational analyses, survivors’ self-reported loneliness (Itzhaky, Stein, Levin, & Solomon, 2017; Solomon & Dekel, 2008), perceived lack of availability of secure relationships (Tsai, Harpaz-Rotem, Pietrzak, & Southwick, 2012), lack of motivation to approach relationship conflict (also known as threat sensitivity; Meis et al., 2017), and perceived lack of forgiveness by partners (Solomon, Dekel, & Zerach, 2009) have all been found to partially or fully mediate the association of PTSD symptoms with relationship functioning. Dekel (2010) also found that partners’ forgiveness of ex-POWs accounted for variance in their own relationship functioning above and beyond the ex-POWs’ PTSD symptoms. Despite the potential explanatory promise of these results, the distinguishability of these constructs from each other and from other constructs reviewed in other sections (e.g., depression, anger) is questionable. Thus, it is difficult to determine whether these constructs are additive or overlapping in accounting for variance in relationship functioning. Moreover, most data in these studies are cross-sectional, raising questions about the directionality of associations.

Interpersonal Constructs & Behaviors

A number of studies have found that survivors with PTSD and their partners report deficits in both emotional intimacy (e.g., Cook et al., 2004; Riggs et al., 1998) and physical intimacy (review by Yehuda, Lehrner, & Rosenbaum, 2015). Although such deficits in survivors are largely synonymous with PTSD symptoms, findings in partners are more novel. One study found some evidence of stronger associations of PTSD symptoms with sexual concerns in African American women as compared to European American women (Gobin & Allard, 2016), although the small sample and lack of statistical comparison of associations limits the confidence in this result.

Some researchers used formal mediational analyses (e.g., path analysis) and found that deficits in emotional and physical intimacy partially or fully mediated the link between PTSD and relationship functioning (Allen, Rhoades, Stanley, & Markman, 2010; Dekel, Enoch, & Solomon, 2008; Riggs, 2014; Zerach, Anat, Solomon, & Heruti, 2010). Although some researchers interpreted such findings in terms of actual mediation (i.e., whereby PTSD leads to intimacy deficits, which then lead to relationship impairment), it is notable that one study also found that relationship functioning partially mediated the negative association of ex-POWs’ PTSD symptoms with their sexual satisfaction (Zerach et al., 2010). Thus, the direction of effects among these variables is not clear. Together with the overlap of reduced emotional intimacy with PTSD symptoms like emotional numbing or social isolation (Badour, Gros, Szafranski, & Acierno, 2015; Nunnink, Goldwaser, Afari, Nievergelt, & Baker, 2010) and the intrinsic links between intimacy and relationship functioning, these limitations make it difficult to derive firm conclusions about a directional pathway among these constructs. Regardless, these findings do indicate that more general decreases in intimacy are more directly associated with relationship problems of trauma survivors than are the specific symptoms of PTSD.

Several researchers have also investigated more overt interpersonal behaviors in the context of the link between PTSD and relationship functioning. Using self-report, partner-report, and objective coding, investigators have documented associations of survivors’ PTSD symptoms with deficits in overall communication, self-disclosure, social skills, expressiveness, humor, active social coping, support provision, and constructive problem solving (Al-Turkait & Ohaeri, 2008; Carroll, Rueger, Foy, & Donahoe, 1985; Hanley, Leifker, Blandon, & Marshall, 2013; Hendrix et al., 1998; LaMotte et al., 2017; Miller, et al., 2013; Solomon, Waysman, Avitzur, & Enoch, 1991; Tsai et al., 2012; Westerink & Giarratano, 1999), as well as increased fear, sadness, and guilt in response to pro-relationship behaviors (Leifker, White, Blandon, & Marshall, 2015). Others have documented similar behavioral deficits in partners (e.g., Bakhurst, McGuire, & Halford, 2018; Hanley et al., 2013; Solomon et al., 1991; Westerink & Giarratano, 1999), and some researchers have again shown such deficits to be particularly tied to symptoms of avoidance/ emotional numbing (e.g., Hendrix et al., 1998; LaMotte et al., 2017). Lastly, some researchers have used formal tests of statistical mediation and found that these types of behaviors partially or fully mediate the association of PTSD with various indices of relationship functioning (Bakhurst et al., 2018; Campbell & Renshaw, 2013; Dekel et al., 2008; Solomon, Dekel, & Zerach, 2008; Tsai et al., 2012). Thus, once again, these more general behavioral issues typically account for more variance in relationship functioning than do specific PTSD symptoms.

A fair amount of research has been conducted on the more specific construct of partner burden. In this context, burden includes experiences like increased household responsibilities, financial difficulties, and social problems that arise due to living with someone with PTSD. Typically, the construct blends both frequency of such problems and the distress experienced due to these problems. A number of studies have found that PTSD symptoms are significantly, directly associated with increased reports of burden in spouses (Beckham, Lytle, & Feldman, 1996; Calhoun, Beckham, & Bosworth, 2002; Caska & Renshaw, 2011; Dekel, Solomon, & Bleich, 2005; Manguno-Mire et al., 2007). Building on this, an additional study of wives of PTSD treatment-seeking veterans found, via structural equation modeling, that wives’ reported burden fully mediated the association of veterans’ functional disability, and partially mediated the association of veterans’ psychological distress, with wives’ relationship functioning (Dekel et al., 2005).

Another specific construct that has begun to receive more attention in the literature is partners’ behavioral accommodation of survivors’ PTSD symptoms. PTSD-related accommodation is defined as actions taken by a romantic partner or family member that are intended to somehow manage or reduce symptoms of PTSD (Fredman, Vorstenbosch, Wagner, Macdonald, & Monson, 2014). Examples of PTSD-related accommodation include restricting noise in the house to avoid provoking a startle response, limiting social engagements if survivors are nervous or on edge when in public, and limiting difficult discussions or emotionally intense topics to avoid arguments (Monson, et al., 2010). Using simultaneous regression, Fredman and colleagues (2014) found that partners’ reported accommodation was negatively associated with relationship functioning, above and beyond their own psychological distress and perceptions of survivors’ PTSD symptoms.

Given that burden and accommodation are both defined as reactions to PTSD, there is conceptual support for the notion that PTSD precedes increases in these constructs. Additionally, the results to date support the idea that burden and accommodation are associated with poorer relationship quality. However, more research is needed to formally evaluate these constructs in a statistical mediation model with longitudinal data. Such research could illuminate possible pathways among these constructs and relationship functioning and might have the potential to provide insight into the causes and byproducts of burden and behavioral accommodation.

Finally, a specific behavior that may play an important role in relationships in the context of PTSD is trauma-related disclosure. Disclosure of traumatic events to close others has been shown to be beneficial to survivors’ mental health, especially when survivors receive positive responses to their disclosure (e.g., Balderrama-Durbin et al., 2013; Bolton, Glenn, Orsillo, Roemer, & Litz, 2003; Koenen, Stellman, Stellman, & Sommer, 2003; Pennebaker & Susman, 1988). The effects of trauma disclosure on partners of trauma survivors, however, are less clear. In two separate studies, when survivors had greater symptoms of PTSD, greater degree of disclosure specifically about their traumatic experience was linked with higher levels of relationship or psychological distress in partners (Campbell & Renshaw, 2012; Lev-Wiesel & Amir, 2001). On the other hand, Monk and Nelson Goff (2014) found that PTSD symptoms were associated with relationship functioning only in military couples with low-moderate levels of trauma disclosure, not in military couples with high levels of trauma disclosure. The question of how much and what type of trauma-related disclosure within romantic relationships is best has been discussed in multiple clinical writings (e.g., Monson & Fredman, 2012), but more research is needed to offer guidance in this area.

Summary

Symptoms of PTSD and related conditions (e.g., depression) are associated with – or may lead to – a variety of intrapersonal and interpersonal experiences in survivors and partners that appear to contribute to relationship distress. Many studies suggest that more general symptoms and behaviors appear to account for greater variance in relationship impairments than do trauma-specific symptoms and behaviors. This pattern holds when evaluating PTSD symptom clusters simultaneously, as well as when evaluating PTSD symptoms together with other constructs. In addition, there is some evidence that constructs representing deficits in positive functioning may account for greater variance in relationship functioning than do excesses of negative constructs, which is consistent with findings from more general investigations of relationship functioning (Gottman & Levenson, 2000; Laurenceau et al., 2005; Pasch & Bradbury, 1998; Smith et al., 1990). However, these findings have been restricted to the context of multivariate analyses of PTSD clusters, rather than analyses of PTSD with other constructs outside PTSD (e.g., depression, anger), in relation to relationship functioning.

There are multiple limitations to the findings reviewed above. First, most data in these studies are cross-sectional in nature, preventing any evaluation of directionality in associations. Research that traces symptoms of PTSD and other related conditions, intrapersonal and interpersonal constructs, and relationship functioning over time is needed to truly test causal mediational pathways. Such data need to be gathered before (or very soon after) a trauma, to rule out the possibility that certain constructs increase the likelihood of developing PTSD after a trauma, and not vice versa.

Second, there is clear conceptual overlap among PTSD symptoms, comorbid symptoms, and many of the other constructs (e.g., intimacy, communication behavior, anger) that have been studied. Thus, even if longitudinal data can be collected, this overlap of constructs raises questions of tautology. For example, does PTSD lead to reduced emotional intimacy, which in turn contributes to relationship dysfunction? Or, is reduced emotional intimacy simply a behavioral manifestation of the emotional numbing symptoms of PTSD and a key index of the broader construct of relationship functioning, thus making the association implied by the very nature of these constructs? Questions such as these must be answered to demonstrate the utility of mediational findings in this area. A key element of addressing these questions may be to examine the specificity of constructs – for instance, does a survivor experience reduced emotional connection across all relationships, or is he or she still able to maintain emotional connection to a romantic partner despite broader emotional distancing?

Third, results of many of these analyses are further confounded by shared method variance. For instance, partners’ reported relationship functioning shares greater method variance with partners’ reports of communication than with survivors’ reports of PTSD. Therefore, shared method variance alone could account for the finding that partners’ reports of communication mediate the link between survivors’ PTSD symptoms and partners’ relationship distress (e.g., Campbell & Renshaw, 2013). Given these problems, research needs to disentangle constructs methodologically, using self-report, partner-report, and more objective measures, to be able to define potential targets of treatment and illuminate statistical and methodological artifacts. As an example, physiological measures may hold some promise as more objective measures of functioning. Preliminary work has shown that PTSD is associated with greater physiological reactivity and attention to threat (Sherin & Nemeroff, 2011), faster attention to partners’ expressions of anger in survivors (Marshall, 2013), and greater cardiovascular reactivity to conflict discussions in both survivors and their partners (Caska et al., 2014). As yet, however, no studies have evaluated whether such physiological excesses are related to relationship distress in the context of PTSD.

Fourth, many studies examine single constructs in isolation as possible mediators of the associations between PTSD and relationship functioning. Given problems in conceptual overlap among symptoms, possible mediators, and relationship functioning, as well as the problems in shared methodological variance, similar approaches in future studies may be of limited value. Rather, studies of potential mediators should likely include measures of other, already established, constructs, to determine whether the new potential mediator accounts for any additional variance in relationship functioning above and beyond established constructs. This type of research can help us identify whether certain domains are additive or overlapping in terms of their ability to explain the link of PTSD with relationship impairments. In such research, conceptual descriptions of how such constructs are thought to relate to each other will be needed. Based on our review, it seems particularly important to attend to whether constructs under investigation are trauma-specific (like re-experiencing symptoms) or general in nature (like emotional withdrawal), as well as whether they represent deficits of positive constructs or excesses of negative constructs. At the same time, given issues with conceptual overlap of constructs and shared methodological variance, care should be taken not to draw definitive conclusions from simple findings of multivariate analyses that attempt to identify which variables are significant. For instance, if a multivariate analysis revealed that psychological aggression was significantly predictive of relationship dysfunction but anger was not, one would not argue that anger was unimportant in understanding relationship dynamics.

Finally, none of the research reviewed above used analyses that would address the possibility of moderation or moderated mediation. One could also argue that several of these constructs could alter the strength of the association between PTSD and relationship functioning (i.e., act as moderators). From the standpoint of our organizational framework, these variables could represent individual or relationship-based moderators, but as yet, there has been very little investigation of this nature.

Contextual Moderators

Our framework also includes a series of contextual moderating variables that may alter the strength or direction of this association. We have grouped these variables into individual, relationship, and environmental domains.

Individual Domain

To date, the construct that has received the greatest empirical attention in this area has been partners’ cognitions about survivors’ symptoms. An attributional model of partner distress (cf. Weiner, 1985) is supported by research showing that the link between combat veterans’ symptoms of PTSD and partners’ relationship distress appears weaker (and often nonsignificant) when partners make external attributions for symptoms of PTSD and when they view symptoms of PTSD as part of an overall disorder (Renshaw, Allen et al., 2014; Renshaw & Campbell, 2011; Renshaw & Caska, 2012; Renshaw, Rodrigues, & Jones, 2008). Thus, romantic partners’ understanding of the nature and causes of PTSD symptoms may moderate the association of those symptoms on their own relationship functioning. This notion is consistent with the inclusion of psychoeducation for partners in couple-based PTSD treatment (e.g., Monson et al., 2012; Sautter et al., 2015). Of note, partners’ attributions could also be conceptualized as a mediator of the link between PTSD and relationship dysfunction. In line with this possibility, Renshaw, Allen, et al. (2014) found that symptoms of re-experiencing were more related to external attributions, whereas symptoms of emotional numbing were more related to internal attributions, but no research has formally examined attributions as mediators.

We identified no other studies of individual-level moderators of the link between PTSD and relationship functioning. However, there are several additional variables that could play a role in this association and warrant future research. As noted above, several constructs that have been studied as mediators could also function as individual moderators. Pre-existing depression in survivors could strengthen the degree to which PTSD symptoms are linked with relationship functioning. Conversely, one could posit a weakening of the association in the context of preexisting depression, as the relationship functioning of such couples may already be compromised and, thus, have less room to deteriorate. Similarly, much as empathy buffers caregivers of older adults from worse relationship functioning (Lee, Brennan, & Daly, 2001), partners’ empathy may enable them to sustain higher levels of relationship satisfaction in spite of stress caused by PTSD symptoms. On the other hand, partners high in empathy may experience greater psychological distress when survivors are highly distressed, which could lead to worsened relationship functioning (e.g., Dekel, Siegel, Fridkin, & Svetlitzky, 2018). Also, partners’ prior experiences with mental illness (e.g., in family members) may make partners more understanding, or may contribute to greater stigmatization of mental illness. In addition, survivors’ willingness to seek treatment could attenuate or exacerbate this association. Couples in which a survivor is actively seeking to improve his or her functioning are likely to be more satisfied than those in which a survivor is resistant or unwilling to seek help. Empirical research is clearly needed to evaluate the potential impact of these types of contextual moderators and identify ways to improve relationship functioning even in the presence of PTSD.

Additional contextual factors that could influence the ways in which PTSD affect relationships include time since trauma, time since onset of PTSD, and type of trauma. Research suggests that social support buffers against the development of PTSD in the immediate aftermath of trauma, but over time, chronic levels of PTSD lead to an erosion of social support (Hall et al., 2014; Kaniasty & Norris, 2008; Robinaugh et al., 2011; Shallcross et al., 2016). Thus, in the immediate aftermath of a trauma, support and closeness may actually increase in well-functioning couples, but as symptoms persist over time, partners’ understanding might wane and burden might increase, impairing relationship functioning. Trauma type, particularly whether the trauma was interpersonal in nature, is another possible moderator. Relative to other traumatic events, those involving assaultive violence tend to be associated with the highest rates of PTSD (e.g., Bresslau et al., 1998; Kilpatrick et al., 2013). Given potential difficulties in interpersonal trust arising from such traumas, assaultive traumas may be associated with greater relationship problems, but to date, no research on this issue exists.

Finally, other possible moderators include the roles of sex, gender, and sexual orientation. Few studies have been published in these areas, but research appears to be growing. First, the meta-analysis by Lambert et al. (2012) revealed that the association of PTSD with perceived relationship quality is stronger for female partners of male trauma survivors than for male partners of female survivors. Also, Renshaw, Campbell, et al. (2014) found that emotional numbing symptoms were more strongly associated with relationship functioning in female combat veterans compared to male combat veterans, and in female partners of combat veterans compared to male partners of combat veterans. Hanley, and colleagues (2013) found that men with greater PTSD symptoms provided less support in couple interactions than did women with greater PTSD. Caska-Wallace, Katon, Lehavot, McGinn, and Simpson (2016) found that, when women veterans reported low partner support, the association of PTSD and relationship functioning was more strongly negative in lesbian couples than in heterosexual couples. The opposite was true when survivors reported high partner support. Finally, Fredman, Le, Marshall, Brick, and Feinberg (2017) found that partner effects of PTSD symptoms on couple functioning were unexpectedly stronger in men than in women when men received a couple-based coparenting intervention. Greater focus on the influences of sex, gender, and sexual orientation is needed to further our understanding of these issues.

Relationship Domain

Partners’ shared understanding of the nature of the trauma, the presence, severity, and nature of survivors’ symptoms, and the need for treatment are also likely moderators of how PTSD impacts relationship functioning. In two separate studies, combat veterans’ self-reported symptoms were negatively associated with partners’ relationship distress after accounting for partners’ perceptions of veterans’ PTSD symptoms, particularly when partners perceived high levels of PTSD (Renshaw et al., 2008; Renshaw, Rodebaugh, & Rodrigues, 2010). This counterintuitive negative association may reflect a benefit of couple agreement about the severity of PTSD symptoms. Also, a recent cross-sectional study by Lambert and colleagues (2015) revealed that the negative association of combat veterans’ self-reported PTSD symptoms with partners’ self-reported relationship quality was attenuated when partners perceived the veteran as supportive and the couple as working together in times of stress. A similar pattern was detected in a longitudinal study of self-report data from couples who experienced an earthquake (Marshall, Kuijer, Simpson, & Szepsenwol, 2017). Thus, as might be expected, the negative impact of PTSD on the relationship is lessened when the broader relationship is strong.

Although we identified no additional research in this area, several relationship characteristics may affect relationship functioning in the context of PTSD. Perhaps the most obvious group of possible moderators – at least, for those who are already in a relationship when a trauma occurs – is pre-trauma relationship functioning. The level of investment, commitment, satisfaction, communication, conflict, and intimacy prior to a trauma or the development of PTSD likely influence the impact of post-trauma symptoms on later couple functioning. This notion is captured by many who have written about couples and trauma (e.g., Nelson Goff & Smith, 2005), but no comprehensive prospective studies of such effects yet exist. More nuanced questions include how such positive relationship characteristics might facilitate better individual responses to trauma, how such qualities might change after the development or maintenance of post-trauma psychopathology, or how pre-existing problems in a couple may be exacerbated or attenuated in the face of a traumatic experience.

Environmental Domain

Environmental factors have been discussed in the context of broader models of couples adjusting to stress and physical illness (e.g., Berg & Upchurch, 2007; Bodenmann, 2005), but we identified no empirical examinations of such factors in the study of couples’ responses to PTSD. External supports, financial resources, and treatment access may profoundly impact the way in which PTSD and couple processes affect each other. For instance, if a survivor and partner agree about the need for treatment but lack ready access, the couple may have a different relationship outcome than a similar couple with ample treatment opportunities. Similarly, even in couples where both individuals agree that treatment is needed and treatment is available, there may be limited improvement in survivors’ functioning (review by Schottenbauer, Glass, Arnkoff, Tendick, & Gray, 2008). Such a lack of improvement could lead to couples’ hopelessness about change, or partners blaming survivors for failing to improve. Other factors, such as external supports (e.g., social network strength and diversity), family and friends’ attitudes, and external stressors (e.g., employment, childcare), are also likely influential.

Summary and Implications

Great strides have been made in understanding the processes by which PTSD may affect romantic relationship functioning. In this paper, we attempted to organize this research in a framework that attends to specific types of symptoms, potential mediators, and potential moderators. Our conceptualization, while broad, allows for consideration of constructs from multiple theoretical orientations. Key limitations identified in our review are that many studies have identified factors that have a great deal of overlap with actual symptoms of PTSD and associated conditions, many studies have focused on purportedly novel mediators in isolation, most studies have relied on cross-sectional data, and few studies have conducted analyses that speak to the question of moderation.

The summation of findings suggests that distinguishing between general constructs (e.g., depression, impaired communication) and trauma-specific constructs (e.g., physiological reactivity to stimuli, disclosure about the traumatic event) may be important in this area of research. In addition, the distinction between “deficits” in positive constructs and “excesses” of negative constructs, similar to that often made in the broader relationship literature (e.g., Laurenceau et al., 2005), may also be important. Consistent with these patterns, recent work by Monson et al. (2012) called for greater attention to emotional numbing and behavioral avoidance in PTSD treatments, which some newer therapies address (Monson et al., 2012; Sautter et al., 2015; Weissman et al., 2018). Such recommendations are not meant to suggest that attending to symptoms like re-experiencing is unimportant, but that symptoms like emotional numbing should not be neglected in the context of addressing more overt symptoms, such as irritability or hypervigilance.

Numerous individual, interpersonal, and environmental factors may also play a role in attenuating or exacerbating the association of PTSD symptoms with relationship functioning. Although such moderating factors could offer intervention targets that do not rely on reducing PTSD symptoms, comparatively little empirical research has been done in this realm to date. Additional work in this area could advance relationship-based treatments for survivors and partners.

Based on our review, we make several recommendations for future research below. We conclude by discussing the clinical implications of the findings reviewed.

Recommendations for Future Research

Collect more extensive longitudinal data.

The majority of the studies use cross-sectional data. Those that use longitudinal data typically rely on only two time points (but see Evans et al., 2009, 2010; Franz et al., 2014; Marshall et al., 2017). There is strong evidence of bidirectional associations between PTSD symptoms and interpersonal variables (e.g., Campbell, Renshaw, Kashdan, Curby, & Carter, 2017; Carter et al., 2016; Dirkzwager, Bramsen & van der Ploeg, 2003). Moreover, time since trauma or PTSD development may play a role in the causal pathways (e.g., Robinaugh et al., 2011). Thus, longitudinal studies of PTSD symptoms, relationship functioning, and potential mediators and moderators that begin pre-trauma are needed to truly identify pathways by which PTSD and relational problems affect each other. Opportunities for such studies exist in samples likely to experience traumatic events (e.g. military service members, emergency responders). Alternatively, studies beginning close to the time of trauma may also be informative.

Move beyond global, retrospective self-report.

Extensive research demonstrates that couple members may have significantly discrepant reports of behaviors like aggression or emotional numbing (e.g., Lamotte, Taft, Reardon, & Miller, 2014). Accordingly, some researchers have begun collecting dyadic data, which should become standard practice in this area. Furthermore, reliance on self-report measures can potentially inflate associations. For instance, biased perceptions of those with PTSD (e.g., Dekel, Peleg, & Solomon, 2013) could lead to artificially high scores on both symptom- and relationship-related measures of distress. Also, using self-report from partners leaves open potential problems with shared method variance when interpreting results of mediational analyses. Measures such as behavioral observation and psychophysiological data can help reduce such bias. Finally, most research to date has used retrospective self-report assessing symptoms or relationship constructs over the previous 2 weeks, 1 month, etc. Studies that use daily diary or ecological momentary assessment methodologies could minimize recall bias, strengthening confidence in the veracity of self-reports, particularly for constructs likely to be dynamic, such as mood, feelings of intimacy, etc.

Address potential tautologies and conceptual overlap.

In many studies reviewed above, proposed mediators and moderators of the association of PTSD with poor relationship functioning have extensive overlap with each other, with PTSD symptoms, and with aspects of relationship functioning. These conceptual overlaps create potential tautologies. Future research should focus on identifying conceptually and empirically distinct mediators and moderators of the association of PTSD with relationship functioning. Moreover, such research should go beyond evaluating simple variations of previously studied constructs (e.g., reduced communication, anger). To address the magnitude of a study’s contribution to the literature, studies of potentially novel mediators should include assessments of other conceptually related constructs that have already been studied in this area, to enable an evaluation of the unique contribution that the new construct makes.

Study constructs of potentially high clinical relevance.

Many constructs that have been frequently written about clinically in the context of PTSD and relationships, such as partner accommodation, survivor substance use, and trauma-specific disclosure, have not yet been subject to sufficient empirical research. Several questions about these constructs thus remain unanswered. For instance, what level of trauma disclosure is optimal within couples, and what factors influence that optimal level? What types of instrumental support might be best suited to reduce partners’ experience of burden? Are the consequences of partner accommodation of PTSD symptoms uniformly negative, or might there be some beneficial effects of moderate levels of accommodation (e.g., increases in survivors’ perceptions of support)? Without more focused research on these trauma- and PTSD-specific constructs in the context of romantic relationships, we lack sufficient evidence to most accurately inform clinical recommendations.

Attend to potential moderators.

To date, very little attention has been paid to contextual variables, or moderators, that may influence the links between PTSD and relationship functioning. Variables such as sex of survivor/partner, timing and nature of trauma, and types of symptoms, among others, need greater attention in future studies.

Clinical Implications

The pathways between PTSD and relationship functioning are complex, and no universal treatment plan is likely to be successful for all distressed couples in which PTSD is a factor. PTSD treatments that incorporate attention to relationships, or even include significant others, are growing (Monson & Fredman, 2012; Sautter et al., 2015), but understanding potential pathways is essential to identifying an expanded array of treatment options. Based on our review, we propose the following constructs as warranting particular clinical attention.

Communication assessment and training.

Empirical research has identified humor, constructive problem solving, support provision, withdrawal, perspective taking, hostility, and self-disclosure as important elements of communication in couples with a trauma survivor. Behavioral research has further shown that PTSD can affect the intimacy in couples’ discussions (Leifker et al., 2015). Thus, attention to these constructs is warranted in treatment. Cognitivebehavioral interventions may be well-suited to address impairments in and interpretations of communication (e.g., Epstein & Baucom, 2002), and such techniques are part of emerging couples-based therapies for PTSD (Monson & Fredman, 2012; Sautter et al., 2015).

Partner cognitions.

Partners’ perceptions of the traumatic event and survivors’ symptoms and their attributions for those symptoms are potentially important contributions to couples’ relationship functioning. Depending on the nature of these cognitions, psychoeducation on PTSD symptoms or clinically managed trauma disclosure may be indicated. It may be particularly important for clinicians to ensure that partners understand the broad sequelae of trauma exposure, which may help lessen the negative impact of some of the more diffuse symptoms (e.g., depression, emotional numbing).

Attend to trauma-specific and non-specific symptoms of PTSD.

In line with the recommendations of Monson et al. (2012), clinicians should ensure adequate attention to symptoms like emotional numbing and behavioral avoidance, in addition to more overt symptoms, such as anger and aggression. This recommendation is not meant to suggest that attending to symptoms such as re-experiencing or aggression is unimportant. Rather, the empirical evidence reviewed here suggests that clinicians working with couples should ensure that symptoms like emotional numbing receive as much focus as more overt symptoms, such as irritability or hypervigilance. Emerging couples-based therapies for PTSD (Monson & Fredman, 2012; Sautter et al., 2015) are valuable resources for addressing such deficits in a dyadic format.

Trauma disclosure.

As yet, there is no empirical information to inform the optimal level of disclosure, which likely varies significantly across couples. Thus, clinicians should be cautious with the level of detail encouraged or facilitated in such disclosures and work actively with couples to identify what boundaries are advisable (e.g., Monson & Fredman, 2012).

Anger and aggression.

Anger is associated with poorer relationship functioning (e.g., Gottman & Levenson, 2000), and repeated expression of anger may sustain hyperarousal symptoms. Relaxation training, emotion regulation skill-building, and other anger management strategies may be appropriate for survivors with excessive experiences of anger. Moreover, aggression should be closely assessed before beginning dyadic treatment (see Monson & Fredman, 2012) and monitored as treatment progresses. Elimination of severe aggressive behavior is a primary and necessary treatment goal prior to beginning couple therapy.

Partners’ behavioral accommodation and burden.

Clinicians should assess, monitor, and address these constructs as needed with couples. Particular attention should be paid to balancing logistical needs of survivors and preferences of partners with the potential interference of accommodating behaviors with treatment progress (e.g., Fredman et al., 2016). Moreover, accommodating partners may need specific psychoeducation about PTSD symptoms and the role of avoidance, as well as clear treatment rationales for exposure-based treatments. Such efforts can successfully modify levels of accommodation (Pukay-Martin et al., 2015).

Role of Funding Sources

Partial funding for this work was provided by NIMH Grant F31-MH098581-A1. NIMH had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Highlights.

Presents organizational framework of links between PTSD and relationship functioning

Specific elements of psychopathology, mediators, and moderators are discussed

Moderators are categorized as individual, relational, or environmental

Clinical implications of findings are discussed

Recommendations for future research are made

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (grant number F31MH098581). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIH.

Author Biographies

Sarah B. Campbell, Ph.D. is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Health Services Research and Development, VA Puget Sound, and a Senior Fellow at the University of Washington, Department of Health Services. Her program of research examines PTSD and its intersection with interpersonal support. Her research additionally explores issues of access to and engagement in PTSD treatment, specifically for military veterans.

Keith D. Renshaw, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor and Chair of the Psychology Department at George Mason University. His research focuses on stress, trauma, anxiety, and relationships in adults, with a particular focus on the experience of military/veteran couples.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Both authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sarah B. Campbell, Department of Psychology, George Mason University, and VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle Division

Keith D. Renshaw, Department of Psychology, George Mason University

References

- Al-Turkait FA, & Ohaeri JU (2008). Post-traumatic stress disorder among wives of Kuwaiti veterans of the first Gulf War. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22, 18–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen ES, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, & Markman HJ (2010). Hitting home: Relationships between recent deployment, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and marital functioning for Army couples. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 280–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed. text revision). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Badour CL, Gros DF, Szafranski DD, & Acierno R (2015). Problems in sexual functioning among male OEF/OIF veterans seeking treatment for posttraumatic stress. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 58, 74–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhurst M, McGuire A, & Halford WK (2018). Trauma symptoms, communication, and relationship satisfaction in military couples. Family Process, 57, 241–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balderrama-Durbin C, Snyder DK, Cigrang J, Talcott GW, Tatum J, Baker M, … Smith Slep AM (2013). Combat disclosure in intimate relationships: Mediating the impact of partner support on posttraumatic stress. Journal of Family Psychology, 27, 560–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck JG, Grant DM, Clapp JD, & Palyo SA (2009). Understanding the interpersonal impact of trauma: Contributions of PTSD and depression. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23, 443–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham JC, Lytle BL, & Feldman ME (1996). Caregiver burden in partners of Vietnam War veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 1068–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CA, & Upchurch R (2007). A developmental-contextual model of couples coping with chronic illness across the adult life span. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 920–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount TH, Peterson AL, & Monson CM (2017). A case study of cognitive-behavioral conjoint therapy for combat-related PTSD in a same-sex military couple. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 24, 319–328. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G (2005). Dyadic coping and its significance for marital functioning In Revenson T, Kayser K, & Bodenmann G (Eds.), Couples coping with stress: Emerging perspectives on dyadic coping (pp. 33–50). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton EE, Glenn DM, Orsillo S, Roemer L, & Litz BT (2003). The relationship between self-disclosure and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in peacekeepers deployed to Somalia. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16, 203–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury T, Rogge R, & Lawrence E (2001). Reconsidering the role of conflict in marriage In Booth A, Crouter AC, & Clements M (Eds.), Couples in conflict (pp. 59–81). Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, & Andreski P (1998). Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: The 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry, 55, 626–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M, Banford A, Mansfield T, Smith D, Whiting J, & Ivey D (2012). Posttraumatic stress symptoms and perceived relationship safety as predictors of dyadic adjustment: A test of mediation and moderation. American Journal of Family Therapy, 40, 349–362. [Google Scholar]

- Busuito A, Huth-Bocks A, & Puro E (2014). Romantic attachment as a moderator of the association between childhood abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Journal of Family Violence, 29, 567–577. [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun PS, Beckham JC, & Bosworth HB (2002). Caregiver burden and psychological distress in partners of veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 15, 205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, & Renshaw KD (2012). Distress in spouses of Vietnam veterans: Associations with communication about deployment experiences. Journal of Family Psychology, 26, 18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, & Renshaw KD (2013). PTSD symptoms, disclosure, and relationship distress: Explorations of mediation and associations over time. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27, 494–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Renshaw KD, Kashdan TB, Curby TW, & Carter SP (2017). A daily diary study of posttraumatic stress disorder and romantic partner accommodation. Behavior Therapy, 48, 222–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll EM, Rueger DB, Foy DW, & Donahoe CP (1985). Vietnam combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: Analysis of marital and cohabitating adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 94, 329–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter SP, DiMauro J, Renshaw KD, Curby TW, Babson KA, & Bonn-Miller MO (2016). Longitudinal associations of friend-based social support and PTSD symptomatology during a cannabis cessation attempt. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 38, 62–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caska CM, & Renshaw KD (2011). Perceived burden in spouses of National Guard/Reserve service members deployed during Operations Enduring and Iraqi Freedom. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25, 346–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caska CM, Smith TW, Renshaw KD, Allen SN, Uchino B, Carlisle M, & Birmingham W (2014). Posttraumatic stress disorder and responses to couple conflict: Implications for cardiovascular risk. Health Psychology, 33, 1273–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caska-Wallace CM, Katon JG, Lehavot K, McGinn MM, & Simpson TL (2016). Posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity and relationship functioning among partnered heterosexual and lesbian women veterans. LGBT Health, 3, 186–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemtob CM, Hamada RS, Roitblat HL, & Muraoka MY (1994). Anger, impulsivity, and anger control in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 827–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemtob CM, Novaco RW, Hamada RS, Gross DM, & Smith G (1997). Anger regulation deficits in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 10, 17–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JM, Riggs DS, Thompson R, Coyne JC, & Sheikh JI (2004). Posttraumatic stress disorder and current relationship functioning among World War II ex-prisoners of war. Journal of Family Psychology, 18, 36–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currier JM, Holland JM, & Allen D (2012). Attachment and mental health symptoms among U.S. Afghanistan and Iraq veterans seeking health care services. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25, 633–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekel R (2010). Couple forgiveness, self-differentiation and secondary traumatization among wives of former POWs. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27, 924–937. [Google Scholar]

- Dekel R, Enoch G, & Solomon Z (2008). The contribution of captivity and post-traumatic stress disorder to marital adjustment of Israeli couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25, 497–510. [Google Scholar]

- Dekel R, Siegel A, Fridkin S, & Svetlitzky V (2018). The double-edged sword: The role of empathy in military veterans’ partners’ distress. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 10, 216–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekel R, & Solomon Z (2006a). Marital relations among former prisoners of war: Contribution of posttraumatic stress disorder, aggression, and sexual satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 709–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekel R, & Solomon Z (2006b). Secondary traumatization among wives of Israeli POWs: the role of POWs’ distress. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41, 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekel R, Solomon Z, & Bleich A (2005). Emotional distress and marital adjustment of caregivers: Contribution of level of impairment and appraised burden. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 18, 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Dekel S, Peleg T, & Solomon Z (2013). The relationship of PTSD to negative cognitions: A 17-year longitudinal study. Psychiatry, 76, 241–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E (1999). Introduction to the special section on the structure of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 803–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dindia K, & Allen M (1992). Sex differences in self-disclosure: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 106–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirkzwager AJ, Bramsen I, & van der Ploeg HM (2003). Social support, coping, life events, and posttraumatic stress symptoms among former peacekeepers: a prospective study. Personality and Individual Differences, 34, 1545–1559. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton LG, & Funder DC (2001). Emotional experience in daily life: Valence, variability, and rate of change. Emotion, 1, 413–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ein-Dor T, Doron G, Solomon Z, Mikulincer M, & Shaver PR (2010). Together in pain: Attachment-related dyadic processes and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57, 317–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhai JD, Biehn TL, Armour C, Klopper JJ, Frueh BC, & Palmieri PA (2011). Evidence for a unique PTSD construct represented by PTSD’s D1–D3 symptoms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25, 340–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein NB, & Baucom DH (2002). Enhanced cognitive-behavioral therapy for couples: A contextual approach. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Erbes CR, Meis LA, Polusny MA, & Compton JS (2011). Couple adjustment and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in National Guard veterans of the Iraq war. Journal of Family Psychology, 25, 479–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbes CR, Meis LA, Polusny MA, Compton JS, & MacDermid Wadsworth S (2012). An examination of PTSD symptoms and relationship functioning in U.S. soldiers of the Iraq War over time. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25, 187–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans L, Cowlishaw S, Forbes D, Parslow R, & Lewis V (2010). Longitudinal analyses of veterans and their partners across treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 611–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans L, Cowlishaw S, & Hopwood M (2009). Family functioning predicts outcomes for veterans in treatment for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Family Psychology, 23, 531–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans L, McHugh T, Hopwood M, & Watt C (2003). Chronic posttraumatic stress disorder and family functioning of Vietnam veterans and their partners. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 37, 765–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz CE, Lyons MJ, Spoon KM, Hauger RL, Jacobson KC, Lohr JB, … Kremen WS (2014). Post-traumatic stress symptoms and adult attachment: A 24 year longitudinal study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22, 1603–1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredman SJ, Beck JG, Shnaider P, Le Y, Pukay-Martin ND, Pentel KZ, … & Marques L (2017). Longitudinal associations between PTSD symptoms and dyadic conflict communication following a severe motor vehicle accident. Behavior Therapy, 48, 235–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredman SJ, Le Y, Marshall AD, Brick TR, & Feinberg ME (2017). A dyadic perspective on PTSD symptoms’ associations with couple functioning and parenting stress in first-time parents. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 6, 117–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredman SJ, Pukay-Martin ND, Macdonald A, Wagner AC, Vorstenbosch V, & Monson CM (2016). Partner accommodation moderates treatment outcomes for couple therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84, 79–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredman SJ, Vorstenbosch V, Wagner AC, Macdonald A, & Monson CM (2014). Partner accommodation in posttraumatic stress disorder: Initial testing of the Significant Others’ Responses to Trauma Scale (SORTS). Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28, 372–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher HC, Lusher D, Gibbs L, Pattison P, Forbes D, Block K, … & Bryant RA (2017). Dyadic effects of attachment on mental health: Couples in a postdisaster context. Journal of Family Psychology, 31, 192–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobin RL, & Allard CB (2016). Associations between sexual health concerns and mental health symptoms among African American and European American women veterans who have experienced interpersonal trauma. Personality and Individual Differences, 100, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, & Levenson RW (2000). The timing of divorce: predicting when a couple will divorce over a 14-year period. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62, 737–745. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Coan J, Carrere S, & Swanson C (1998). Predicting marital happiness and stability from newlywed interactions. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60, 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hall BJ, Bonanno GA, Bolton PA, & Bass JK (2014). A longitudinal investigation of changes to social resources associated with psychological distress among Kurdish torture survivors living in Northern Iraq. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27, 446–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton S, Nelson Goff BS, Crow JR, & Reisbig AMJ (2009). Primary trauma of female partners in a military sample: Individual symptoms and relationship satisfaction. American Journal of Family Therapy, 37, 336–346. [Google Scholar]

- Hanley KE, Leifker FR, Blandon AY, & Marshall AD (2013). Gender differences in the impact of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms on community couples’ intimacy behaviors. Journal of Family Psychology, 27, 525–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, & Rockwood NJ (2017). Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 98, 39–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix CC, Erdmann MA, & Briggs K (1998). Impact of Vietnam veterans’ arousal and avoidance on spouses’ perceptions of family life. American Journal of Family Therapy, 26, 115–128. [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, Richters JE, Weintraub S, & Neale JM (1987). Psychopathology and marital distress: The positive side of positive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 96, 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhaky L, Stein JY, Levin Y, & Solomon Z (2017). Posttraumatic stress symptoms and marital adjustment among Israeli combat veterans: The role of loneliness and attachment. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9, 655–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MD, Cohan CL, Davila J, Lawrence E, Rogge RD, Karney BR, Sullivan KT, & Bradbury TN (2005). Problem-solving skills and affective expressions as predictors of change in marital satisfaction. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 15–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SM, & Williams-Keeler L (1998). Creating healing relationships for couples dealing with trauma: The use of emotionally focused marital therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 24, 25–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniasty K, & Norris FH (2008). Longitudinal linkages between perceived social support and posttraumatic stress symptoms: sequential roles of social causation and social selection. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21, 274–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Milanak ME, Miller MW, Keyes KM, & Friedman MJ (2013). National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26, 537–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King DW, Leskin GA, King LA, & Weathers FW (1998). Confirmatory factor analysis of the clinician-administered PTSD Scale: Evidence for the dimensionality of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Assessment, 10, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch-Fedders LM, Caska-Wallace CM, Smith TW, & Renshaw KD (2017). Battling on the home front: Posttraumatic stress disorder and conflict behavior among military couples. Behavior Therapy, 48, 247–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenen KC, Stellman JM, Stellman SD, & Sommer JF Jr. (2003). Risk factors for course of posttraumatic stress disorder among Vietnam veterans: A 14-year follow-up of American legionnaires. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 980–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JE, Engh R, Hasbun A, & Holzer J (2012). Impact of posttraumatic stress disorder on the relationship quality and psychological distress of intimate partners: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Family Psychology, 26, 729–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JE, Hasbun A, Engh R, & Holzer J (2015). Veteran PTSS and spouse relationship quality: The importance of dyadic coping. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 7, 493–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamotte AD, Taft CT, Reardon AF, & Miller MW (2014). Agreement between veteran and partner reports of intimate partner aggression. Psychological Assessment, 26, 13691374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMotte AD, Taft CT, Weatherill RP, & Eckhardt CI (2017). Social skills deficits as a mediator between PTSD symptoms and intimate partner aggression in returning veterans. Journal of Family Psychology, 31, 105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]