Abstract

Purpose

Off-target binding in the reference region is a challenge for recent tau tracers 18F-AV-1451 and 18F-THK5351. The conventional standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) method relies on the average uptake from an unaffected tissue sample, and therefore is susceptible to biases from off-target binding as well as variability among individuals in the reference region. We propose a new method, standardized uptake value peak-alignment (SUVP), to reduce the bias of the SUVR, and improve the quantitative assessment of tau deposition.

Methods

The SUVP normalizes uptake values by their mode and standard deviation. Instead of using a reference region, the SUVP derives the contrast from unaffected voxels over the whole brain. Using SUVP and SUVR methods, we evaluated the global and regional tau binding of 18F-THK5351 and 18F-AV-1451 on two independent cohorts (N = 18 and 32, respectively), each with cognitively normal (NL) subjects and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) subjects.

Results

Both tracers showed significantly increased binding for AD in the targeted cortical areas. In the temporal cortex, SUVP had a higher classification success rate (CSR) than SUVR (0.96 vs 0.89 for 18F-THK5351; 0.86 vs 0.75 for 18F-AV-1451), as well as higher specificity under fixed sensitivity around 0.80 (0.70 vs 0.45 specificity for 18F-THK5351; 1.00 vs 0.78 for 18F-AV-1451). In the cerebellar cortex, an AD-NL group difference with effect size (Cohen’s d) of 0.62 was observed for AV-1451, confirming the limitation of the SUVR approach using this region as a reference. A smaller cerebellar effect size (0.09) was observed for THK5351. Conclusion The SUVP method reduces the bias of the reference region and improves the NL-AD classification compared to the SUVR approach.

Keywords: PET, Standardized uptake value, Peak-alignment, Tau, Alzheimer’s disease

Introduction

Tau accumulates abnormally in the brain of neurodegenerative diseases known as tauopathies [1]. Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common tauopathy, affects over five million people in the United States. Abnormal tau accumulates in neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), initially in the entorhinal region then progresses in well-defined stages [2, 3]. Recently, several candidate NFT PET tracers have been developed and validated for imaging tau deposition in the brain [4, 5]. 18F-AV-1451 (denoted as AV1451 below) and 18F-THK5351 (denoted as THK5351 below) are among the most studied tau PET tracers [6]. Detecting tau deposition in vivo may differentiate tauopathies and improve the early diagnosis of AD [7]. To quantitate the tau deposition with PET tracers, we commonly employ the SUVR approach. This entails normalizing the standardized uptake value (SUV) to the uptake of a reference region that is unaffected by disease [8]. Recent studies from McGill University [9] and UC Berkeley [10] show that off-target binding affects the cerebellar cortex reference region in both of THK5351 and AV1451 images. These results suggest that the SUVR method may be affected by individual variability or group differences in the reference uptake between normal and disease subjects.

Here, we present a new method named standardized uptake value peak-alignment (SUVP). This method is based on the whole brain distribution comprised mostly of unaffected voxels. The goal is to reduce the quantitation sensitivity from the reference uptake and improve the precision of tau uptake measures. Based on a multi-site dataset of 50 well characterized AD and normal control (NL) subjects, the diagnostic value of SUVP was compared to SUVR separately using two tau PET tracers (AV1451 and THK5351). The region with strongest AD-NL group difference for SUVR was identified, and used to compare the AD classification accuracy of SUVR and SUVP. Our findings confirm the hypothesis that the SUVP normalization method improves on the SUVR in the detection of taupathology in AD by reducing bias from the cerebellar reference region.

Materials and methods

PET study participants

The subjects and PET images come from two sources: 18 subjects (nine AD patients, and nine NL) from the memory clinic of Tohoku University Hospital with THK5351 PET images; 32 Subjects (20 NL and 12 AD) from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) with AV1451 PET images. The age and MMSE of the ADNI sample were matched to the Tohoku University Hospital sample (independent cohort) for comparability. Both the ADNI and Tohoku University Hospital PET studies were approved by institutional review boards. All subjects signed an informed consent form. The ADNI was launched in 2003 as a public-private partnership, led by Principal Investigator Michael W. Weiner, MD. The primary goal of ADNI has been to test whether serial MRI, PET, other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and early AD. For up-to-date information, see www.adni-info.org. The Tohoku University Hospital sample was a cohort created to test the diagnostic value of the THK5351 compound.

Participant demographic data are shown in Table 1. All AD diagnoses were made at consensus conferences according to the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke/AD and Related Disorders Association criteria [11]. In addition to the PET scan, each participant received standardized neuropsychological and clinical assessments and a high resolution T1 weighted MRI scan.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| THK5351 | AV1451 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NL(n = 9) | AD(n = 9) | NL(n = 20) | AD(n = 12) | |

| Mean age* (min, max) | 73(61,90) | 76 (58, 88) | 73 (68, 82) | 78 (60, 90) |

| Female* (% in the group) | 2 (22%) | 3 (33%) | 9 (45%) | 6 (50%) |

| Mean MMSE (min, max) | 29 (27, 30) | 20 (18, 25) | 29 (28, 30) | 21 (14,25) |

No group differences between NL and AD subjects. Abbreviations: MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination

Image acquisition

THK5351

PET scans were conducted using an Eminence STARGATE PET scanner (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) [12]. After intravenous injection of 185 MBq THK5351, dynamic PET images were scanned immediately and obtained for 60 min in list mode. PET scans were iteratively reconstructed using 3D-DRAMA algorithm (one iteration, 128 filter cycle, Gaussian filter: 3 mm FWHM, 128 × 128 matrix, slice thickness of 2.6 mm). THK5351 was synthesized as previously described [12]. T1 weighted MR images were obtained for all participants using a SIGNA 1.5-Tesla system (General Electric, Milwaukee, WI). A 3-D volumetric acquisition of a T1-weighted gradient echo sequence produced a gapless series of thin axial sections by using a vascular TOF SPGR sequence (echo time/repetition time, 2.4/50 ms; flip angle, 45°; acquisition matrix, 256 × 256; one excitation; field of view, 22 cm; slice thickness, 2.0 mm). Both PET and MRI scans were acquired from the same site.

AV1451

All PET and MRI images were retrieved from the ADNI database server in the most fully pre-processed format (Advanced search: “AV45 Coreg, Avg, Std Img and Vox Siz, Uniform Resolution” for PET data; and “MR_MT1, GradWarp, N3m” for MRI data). For PET, an intravenous injection of 370 MBq AV1451 was followed by a saline flush.

At approximately 75 min following injection, a continuous 30-min brain scan (six frames of 5 min duration) was performed after a CT or transmission scan for attenuation correction. PET scans were iteratively reconstructed using a 3-D OSEM algorithm (four iterations, 12 subsets, Gaussian filter: 5 mm FWHM, 128 × 128 matrix, slice thickness of 3 mm). To account for variations between scanners, the PET data were smoothed to a uniform resolution (8-mm full width at half-maximum) according to standard ADNI procedures [24]. The MRI data consisted of T1-weighted sagittal 3-D MPRAGE sequences acquired at different field strengths and magnet manufacturers, with uniformed imaging parameters: acquisition matrix 240×256×176; pixel size 1.0 × 1.0 mm; slice thickness = 1.2 mm. More detailed information on the imaging protocols employed across ADNI sites and standardized image pre-processing steps for MRI and PET acquisitions can be found on the ADNI website (http://adni.loni.usc.edu/methods/).

Image preprocessing

Using Freesurfer (Version 5.1, Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, USA), regions of interest (ROIs) were determined on 3DT1 MRI images for the cerebral gray and white matter, the cerebellar gray and white matter, and the subcortical regions including, frontal, parietal, occipital, and temporal lobes. (ROI definitions are described in Supplemental Table 1). Dynamic PET frames were realigned to the mean image. No data were excluded for excessive motion. The 40–60 min summed images for THK5351 and 80– 100 min summed images for AV1451 were registered to the corresponding MRI images, where ROIs were segmented. Nearest-neighbor interpolation was used for reslicing. The realignment, coregistration and reslicing were all carried out with the Statistical Parametric Mapping software (Version 12, Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, UK).

Estimations of tracer binding

The SUV images were obtained by dividing PET activity in late dynamic frame by injected dose and body weight. According to the accepted procedures, tau deposition was determined for THK5351 with the 40–60 min SUV and for AV1451 with for the 80–100 min SUV [4, 6].

SUVR

Conventional SUVR images were constructed from each SUV image by first computing the average SUV in cerebellar cortex as the reference value [6], and then dividing the SUV in each voxel by the reference value.

SUVP

The SUVP image is computed from the SUVimage by a voxelwise operation: SUVP = (SUV-M)/S, where M is the mode of the whole brain SUV after rounding, and S is the standard deviation (SD) of the whole brain SUV after rounding. In this study, the SUV was rounded to the second digit after decimal point (i.e., data was ignored from the third decimal digit on) when determining M and S, because the signal-to-noise ratio of PET does not warrant better precision.

Since the SUVP image is a voxel-based image per subject, this allows investigation of individual subject’s binding profile in specific ROIs, by drawing the histograms of voxel-wise SUVP values for all the voxels in each ROI. Different subjects’ SUVP histograms for the same ROI can then be averaged over a subject group, defined by the tracer (THK5351 or AV1451) and the disease condition (AD or NL), to generate the group level SUVP histograms for that ROI.

For each PET exam, we first defined the ROIs from the segmented MRI, including a whole brain mask, which consists of the gray matter and white matter of both the cerebrum and the cerebellum. The Freesurfer definitions of these regions are listed in Suppl. Table 1. The regional histograms of SUVP image were then computed for each individual subject and ROI. Finally, the individual regional histograms were averaged within the four subject groups (two tracers × two conditions, Fig. 1). Note that the SUVP standardized the span of whole brain SUV into a similar range regardless of tracer or disease condition. This allows universal cutoff values of positive binding for different tracers. To evaluate the tracers’ binding profiles in the SUVP images, the positive binding percentages (PBP) were computed by dividing the number of positive binding (SUVP>cutoff) voxels by the total number of the voxels from the ROIs. A cutoff value of 1.5 was used to define positive binding voxel on SUVP, representing 1.5 times SD from whole brain mode. For comparison, SUVR PBP was also calculated by using previous published cutoff values, 1.5 for THK5351 PET and 1.19 for AV1451 PET [13–16]. The acquisition and reconstruction of THK5351 scans were identical as in the papers that report the cut-off values, and more or less similar for AV1451. In the latter case, this requires that the results of AV1451 should be interpreted with care.

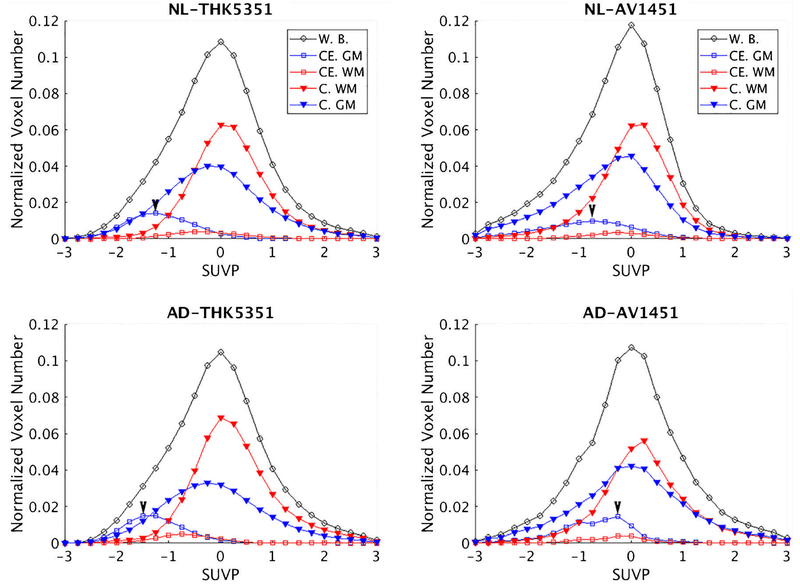

Fig. 1.

Group average histograms for SUVP-enhanced PET images in five different regions. The 2 × 2 layout corresponds to tracers (left-THK5351, right-AV1451) and diagnosis (top-normal, bottom-Alzheimer’s patients), corresponding subject numbers in Table 1. For each subplot, X axis is the SUVP value; Yaxis is the voxel counts divided by total intracranial voxel numbers, i.e., the percentage of voxels in whole brain, 0.01 = 1%. The peaks of cerebellar GM histograms are marked by arrows. Abbreviations: W.B.: Whole brain; CE. GM: cerebellar gray matter; CE. WM: cerebellar white matter; C. GM: cerebral gray matter; C. WM: cerebral white matter

Statistical analyses

The covariates’ influences were tested for each tracer between AD and NL groups, with t-tests for age and Chi-squared analysis for sex. With the absence of any significant group differences on these measures, they would not be included as covariates in any of the models.

Regional binding profiles

For each tracer, the SUVR mean, SUVR PBP and SUVP PBP were compared between AD and NL subjects for the following ROIs: temporal, frontal, parietal and occipital cortex. Nonparametric Mann-Whitney U tests were used for the THK5351 data because of the small sample size. Two-sample t-tests were used for the AV1451 data, log transform was used for the ROIs where the data showed significant deviations from the normal distribution in the normality tests (Shapiro-Wilk test and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). The AD-NL group difference of SUVP in Cerebellar GM was estimated in terms of effect size (Cohen’s d), to quantify the bias of using cerebellar GM as reference region in the SUVR. To find the most prominent cortical region in AD with THK5351 and AV1451 tracers, the binding (in SUVR and SUVP) in the temporal cortex was compared to the frontal cortex, parietal cortex, and occipital cortex, with pairwise t-tests.

Diagnostic accuracy

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were examined to assess the diagnostic group discrimination with SUVR and SUVP. We also computed the classification success rate (CSR) and true negative rate (specificity) values. CSR is computed by finding the optimal thresholds on the ROC curves for each measurement (SUVR mean, SUVR PBP and SUVP PBP) and tracer (THK5351 and AV1451), then dividing the number of successfully classified subjects (i.e., AD classified as AD, and NL classified as NL) by the total number of classified subjects. The specificity values of different measurements are compared under the same true positive rate (sensitivity). To simulate clinical use, in one scenario we compared the diagnostic specificity at sensitivity fixed to the closest value to 0.8. To compare the group separation capability of regional SUVP and SUVR, we examined the between-group ratio R of AD and NL average PBP for the temporal lobe, where SUVR group difference was found strongest (Table 1).

All models were tested for compliance with the model assumptions and any violations are reported. Bonferroni correction was used to account for multiple comparisons across ROIs and the adjusted threshold for statistical significance was set at 0.01. All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS (Version 23, IBM Inc.).

Results

SUVR in global and regional tracer binding

As expected, higher cerebral GM SUVRs were found in AD compared to NL for both THK5351 and AV1451 (U = 64, p < 0.05; t(30) = 2.0 p < 0.05, respectively) (Table 2). For THK5351, the temporal cortex SUVR was higher than the frontal (t(8) = 18.3 p < 0.01), parietal (t(8) = 8.8 p < 0.01) and occipital cortex (t(8) = 11.4 p < 0.01) SUVR. A similar finding was observed for AV1451, where the AD temporal cortex binding was statistically greater as compared to frontal (t(11) = 5.9 p < 0.01), parietal (t(11) = 5.8 p < 0.01) and occipital cortex (t(11) = 3.7 p < 0.01)(Table2).

Table 2.

Regional binding profiles with SUVR (mean)

| THK5351 | AV1451 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NL(n = 9) | AD(n = 9) | NL(n = 20) | AD(n = 12) | |

| Temporal cortex | 1.57(.21) | 1.88(.22)*+ | 1.18(.16) | 1.41(.35)*+ |

| Frontal cortex | 1.32(.20) | 1.38(.18) | 1.06(.07) | 1.18(.23) |

| Parietal cortex | 1.30(.24) | 1.46(.12) | 1.07(.10) | 1.25(30) |

| Occipital cortex | 1.22(.13) | 1.42(.16)+ | 1.09(.09) | 1.17(.13) |

Data presented as mean (SD).

Significantly higher than other regions.

AD significantly different from NL

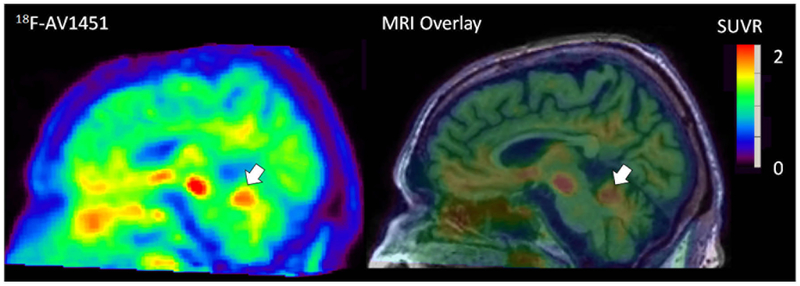

Comparing AD to NL, THK5351 showed significantly higher binding for AD in the temporal cortex (U = 73 p < 0.01) and the occipital cortex (U = 70 p < 0.01). AV1451 also showed higher binding for AD in the temporal cortex (t(30) = 2.6 p = 0.01). From the images, off-target binding was observed in the cerebellum in AV1451 and in the cerebral white matter and non-brain regions in both THK5351 and AV1451 (Figs. 2a–d and 3).

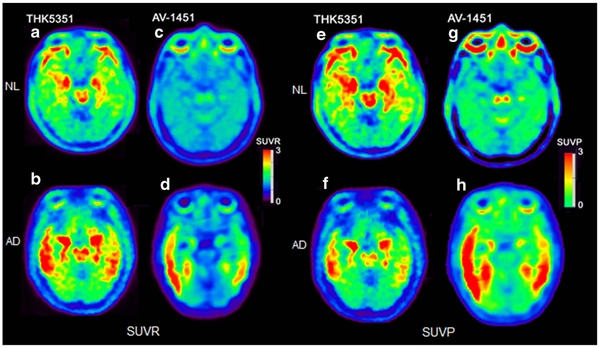

Fig. 2.

SUVR and SUVP images of four typical subjects, one from each tracer/condition. The first and second columns (slices a-d) are SUVR images. The first column contains two THK5351 scans of (a) 71-year-old male NL subject with MMSE 28, and (b) 78-year-old AD subject with MMSE 15. The second column contains two AV1451 scans of (c) 72-year-old male NL subject with MMSE 30 and (d) 77-year-old AD subject with MMSE 19. Slice was picked at midbrain level. The third and fourth columns (slices e-h) are SUVP images. The third column contains two THK5351 scans of the same subjects and slice positions as the first column. The fourth column contains two AV1451 scans of the same subjects and slice positions as the second column

Fig. 3.

AV1451 PET of AD subject showed off-target binding in cerebellum (marked by arrows)

SUVP in global and regional tracer binding

The mean SUVP histograms for the four groups (two tracers × two conditions) are shown in Fig. 1. Each histogram was computed with 25 bins centered from −3 to 3, with 0.25 intervals. As expected, the peak values of the cerebellar GM curves (CE. GM) are lower compared to other regions in all groups, reflecting less tracer retention. However, for both tracers the cerebellar GM shows a peak shift and difference in the number of affected voxels between AD and NL. This result demonstrates the potential bias of using cerebellar GM as the reference region. The SUVP value of the cerebellar GM peak in Fig. 1, although low as expected, showed opposite directions of group differences in two tracers (THK5351: AD<NL with effect size0.09; AV1451: AD>NL with effect size 0.62). These data further confirm the potential risk of relying on the cerebellar region to normalize regional data in a test for group differences.

With the SUVP method, AV1451 showed significantly higher total cerebral GM binding in AD compared to NL (t(30) = 2.9 p < 0.01). However, there is only a trend for THK5351 (p = 0.07). Similar to the SUVR analysis, for the THK5351 SUVP, the most prominent cortical region in AD in terms of binding is the temporal cortex, as compared to the frontal cortex (t(8) = 12.03 p < 0.01), parietal cortex (t(8) =8.21 p < 0.01) and occipital cortex(t(8) = 10.77 p < 0.01). A similar finding was observed in AV1451. Temporal cortex SUVP PBP was higher than frontal (t(11) = 3.86 p < 0.01), parietal (t(11) = 4.16 p < 0.01) and occipital cortex SUVP PBP (t(11) = 3.22 p < 0.01) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Regional binding profiles with SUVP (PBP)

| THK5351 | AV1451 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NL(n = 9) | AD(n = 9) | NL(n = 20) | AD(n = 12) | |

| Temporal cortex | 6.93(4.78) | 17.94(5.15)*+ | 5.44(11.10) | 20.72(20.48)*+ |

| Frontal cortex | 2.37(1.25) | 1.25(0.86)++ | 0.78(1.43) | 5.32(7.70) |

| Partial cortex | 0.17(0.21) | 2.16(3.33)+ | 0.95(3.21) | 10.2(15.2)+ |

| Occipital cortex | 0.05(0.09) | 1.73(2.79) | 0.54(1.58) | 5.59(8.23)+ |

Data presented as mean (SD).

Significantly higher than other regions.

AD significantly different from NL.

AD different from NL with trending significance. Abbreviations: PBP, positive binding percentage

Comparing AD to NL, the THK5351 SUVP showed higher binding in the temporal cortex (U = 75 p < 0.01) and parietal cortex (U = 73 p < 0.01). Interestingly, the frontal cortex showed only a trend for significance (U = 18 p = 0.05). AV1451 showed higher SUVP binding for AD in the temporal cortex (t(30) = 2.8 p < 0.01), parietal cortex (t(30) = 2.6 p =0.01) and occipital cortex (t(30) = 2.7 p = 0.01) (Table 3).

Figure 2e-h shows the SUVP images of the same four subjects/slices as in Fig. 2a-d. THK5351 showed more brain stem binding than AV1451 in both SUVR and SUVP images. For AV1451, compared with the SUVR images in Fig. 2a-d, the SUVP images enhanced the positive binding voxel clusters, as well as revealed tracer binding in substantia nigra, which was invisible on the SUVR images.

SUVR and SUVP in diagnostic accuracy

The classification success rate (CSR), specificity under fixed sensitivity, and AD-NL between group ratio (R) in temporal lobe are all reported in Table 4. For both tracers, SUVP (PBP) showed higher CSR, higher specificity and higher R than SUVR (mean and PBP), indicating high diagnostic accuracy. Note the fixed sensitivity values are slightly different in THK5351 and AV1451 (0.833 vs 0.788), due to the discrete ROC results.

Table 4.

Diagnostic accuracy with temporal lobe SUVR and SUVP

| Tracer | SUVR Mean | SUVR PBP | SUVP PBP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classification Success Rate | THK5351 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.96 |

| AV1451 | 0.75 | 0.73 | 0.86 | |

| Specificity under fixed sensitivity | THK5351(sen = 0.833) | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.70 |

| AV1451(sen = 0.788) | 0.78 | 0.89 | 1.00 | |

| Between-group ratio | THK5351 | 1.20 | 1.25 | 2.59 |

| AV1451 | 1.19 | 1.30 | 3.81 |

Abbreviations: sen, sensitivity. PBP, positive binding percentage

Discussion

Classic in vivo kinetic models with arterial sampling are still the gold standard for quantifying tau tracer retention on PET scans. However, less invasive methods without arterial sampling, such as SUVR and SUVP, are better suited for clinical usage. In this paper we compared the SUVR with the SUVP method for quantifying the tau binding profiles on PET images for two different tracers and contrasted AD and NL subjects.

Tracer binding profile

THK5351 and AV1451 both reflect tau pathology in AD brains [12, 17]. However, off-target binding appears to be an issue [9, 18, 19] and has been reported in the cerebral white matter, pons, and choroidal plexus [9, 17]. Moreover, both tracers show variability in the cerebellum, a conventional reference region for the SUVR. The SUVR measure can potentially be biased by these variations in the reference region, especially in AV1451, where there is more cerebellar GM binding in AD compared to NL. By comparison, cerebellar WM showed less variation on Fig. 2a–d and Supplementary Fig. 2. The variation of off-target binding between diagnostic groups limits the power of tau tracers in disease diagnosis. For the temporal lobe, using AV1451 the SUVP positive binding percentage (PBP) increased the diagnosis accuracy rate (CSR) to 86%, compared to SUVR PBP (73%) and conventional mean SUVR (75%) in temporal lobe tau measures.

MAO-B binding introduces noise with the THK5351 tracer [9]. Unlike in the temporal and parietal lobe, where more binding was observed in AD, less binding was observed in the frontal lobe of AD subjects. Histopathology studies have demonstrated levels of MAO-B are higher in frontal regions compared to other cortical regions [20], indicating the MAO-B binding for THK5351 is more involved in the frontal lobe. The THK5351 temporal cortex SUVP measure is robust in distinguishing AD from NL (CSR = 0.96), which possibly reflects the reactive astrogliosis after amyloid or tau deposition [21].

Comparison of SUVR, SUVP and other uptake quantification methods

Distributions of individual subjects’ SUV vary in peaks and spans on PET images because of scanner, tracer, and subject differences. Therefore, a standardization method is necessary for comparing tracer binding profiles of different subjects from different centers and with tracers that have variable impact on the reference region. The SUVP method uses the peak and span of whole brain SUV distributions to standardize and evaluate the signal intensity. Tau PET tracers were designed to bind hyperphosphorylated tau (PHF-tau) which represents only a small fraction of the brain volume. The unaffected tissue, therefore, becomes background signal and offers a natural reference to adjust the signal intensity. The mode of the SUV data reflects the majority of the background signal which is unaffected by tau pathology. Instead of using a reference region, SUVP picks unaffected background as contrast. As shown in the results section, a main advantage of SUVP is the standardization of the SUV range. For the same subjects, the groups mean histograms of SUVR (counting normalized by total intracranial voxel numbers) are shown in the Supplemental Data. Compared with the group mean histograms of SUVP (Fig. 1), the SUVR histograms showed large variations in the data ranges between two tracers, making it a challenge to compare the binding profiles across the tracers.

Klunk et al. proposed [22] to standardize the SUV readings from PiB and other Amyloid PET tracers into a fixed range of 1~100. This algorithm, named the Centiloid method, uses the group mean SUVRs of AD and NL groups as baselines. While the Centiloid method is attractive for its lower sensitivity to individual reference regions than SUVR, it is more laborious than SUVP. The comparison of Centiloid to SUVP would be an interesting topic for a future study.

Vemuri et al. proposed z-score standardization on tau SUVR to enhance AD/NL separation [8]. Rather than using the mean in the SUVR z-score method, the SUVP method uses sample mode for standardization. Under a skewed unimodal distribution, sample mode captures the “peak” better than mean or median [23]. There is also a practical argument for choosing the mode: when radiologists read PET scans, their perception of the “image brightness” does not reflect the mean pixel value of the image. Rather, their perception is based on the value of the majority pixels, i.e., the most frequent pixel value on the screen. Likewise, when radiologists adjust the intensity window of different PET scans to the same recognizable range for diagnoses, they are actually standardizing the image mode, not the mean.

Limitations

The small sample size of this study limited the statistical power of the results. One limitation of the SUVP method is the assumption of unimodal distribution for whole brain SUV, i.e., the mode is unique. This assumption holds true for all the tau PET data analyzed in this paper. However, it may not be true for other data. Future work includes developing alternative ways to estimate the peak and span of the SUV histograms, so that the SUVP can be extended to tracers with multimodal SUV distributions. Because the SUVP image and SUVR image are measured differently (PBP for SUVP vs. mean for SUVR), the SUVP PBP measurement showed a larger within-group variation than SUVR mean. However, that does not affect the SUVP classification improvement, as SUVP PBP showed larger between-group contrast. In the parietal cortex, for example, the coefficient of variation (the ratio of SD over mean) is under 25% for SUVR (Table 2) and over 100% for SUVP (Table 3). Nevertheless, SUVP still showed larger group difference than SUVR in both tracers.

Conclusion

Both AV1451 and THK5351 tracers showed significantly increased tau binding for AD subjects in the targeted cortical area. However, for both tracers binding was also found in the un-targeted areas, such as white matter and cerebellum. The cerebellar binding causes bias for the conventional SUVR approach, which uses the cerebellar cortex as the assumed unaffected reference tissue for binding normalization and quantification. As a result, it increases the variation of quantitative tau measurements in AD subjects. The SUVP approach reduces such bias by normalizing whole brain SUV distribution, controlling for both mode and standard deviation.

Our results show that the SUVP method can potentially improve upon the conventional SUVR method, with higher specificity and AD classification accuracy. The SUVP method offers an alternative approach for tracers with reference region issues. Because SUVP intrinsically normalizes SUV from different tracers into a comparable range, it can also be used as a framework for cross-tracer evaluation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Eugene M. Laska for his constructive advice on the SUVP algorithm, and Mi Ri Lee for her support in data management.

Data collection and sharing for this project was also funded by the ADNI (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12–2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Funding

This study was funded by NIH/NIA grants AG035137, AG032554, AG022374, AG13616, AG12101, AG08051, NIHHLB HL111724, HL118624, T32AG052909–01A1 and Cohen Veterans Bioscience. The work at Tohoku University was supported by Health and Labor Sciences research grants from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan, a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (23390297), a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (26117003), and a grant from the Japan Advanced Molecular Imaging Program (J-AMP) of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

Footnotes

The AV1451 data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-018-4040-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest.

Authors YL, JC and MdeL applied for a patent to be assigned to NYU, based on this work. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Williams DR. Tauopathies: classification and clinical update on neurodegenerative diseases associated with microtubule-associated protein tau. Intern Med J. 2006;36:652–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hyman BT, Trojanowski JQ. Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer disease from the National Institute on Aging and the Reagan institute working group on diagnostic criteria for the neuropathological assessment of Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56:1095–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). 1991;82:239–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okamura N, Furumoto S, Harada R, Tago T, Yoshikawa T, Fodero-Tavoletti M, et al. Novel 18F-labeled arylquinoline derivatives for noninvasive imaging of tau pathology in Alzheimer disease. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:1420–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson KA, Schultz A, Betensky RA, Becker JA, Sepulcre J, Rentz D, et al. Tau positron emission tomographic imaging in aging and early Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2016;79:110–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jang YK, Lyoo CH, Park S, Oh SJ, Cho H, Oh M, et al. Head to head comparison of [(18)F] AV-1451 and [(18)F] THK5351 for tau imaging in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sergeant N, Delacourte A, Buee L. Tau protein as a differential biomarker of tauopathies. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1739;2005: 179–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vemuri P, Lowe VJ, Knopman DS, Senjem ML, Kemp BJ, Schwarz CG, et al. Tau-PET uptake: regional variation in average SUVR and impact of amyloid deposition. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2016;6:21–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng KP, Pascoal TA, Mathotaarachchi S, Therriault J, Kang MS, Shin M, et al. Monoamine oxidase B inhibitor, selegiline, reduces 18F-THK5351 uptake in the human brain. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017;9:25, 017–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker SL, Maass A, Jagust WJ. Considerations and code for partial volume correcting [18F]-AV-1451 tau PET data. Data Brief. 2017;15:648–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harada R, Okamura N, Furumoto S, Furukawa K, Ishiki A, Tomita N, et al. 18F-THK5351: a novel PET radiotracer for imaging neurofibrillary pathology in Alzheimer disease. J Nucl Med. 2016;57: 208–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang L, Benzinger TL, Su Y, Christensen J, Friedrichsen K, Aldea P, et al. Evaluation of tau imaging in staging Alzheimer disease and revealing interactions between beta-amyloid and Tauopathy. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:1070–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y, Tsui W, Rusinek H, Butler T, Mosconi L, Pirraglia E, et al. Cortical laminar binding of PET amyloid and tau tracers in Alzheimer disease. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:270–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lockhart SN, Baker SL, Okamura N, Furukawa K, Ishiki A, Furumoto S, et al. Dynamic PET measures of tau accumulation in cognitively normal older adults and Alzheimer’s disease patients measured using [18F] THK-5351 . PLoS One. 2016;11:e0158460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maass A, Landau S, Baker SL, Horng A, Lockhart SN, La Joie R, et al. Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative. Comparison of multiple tau-PET measures as biomarkers in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroImage. 2017;157:448–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowe VJ, Curran G, Fang P, Liesinger AM, Josephs KA, Parisi JE, et al. An autoradiographic evaluation of AV-1451 Tau PET in dementia. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2016;4:58,016–031 5–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Passamonti L, Vazquez Rodriguez P, Hong YT, Allinson KS, Williamson D, Borchert RJ, et al. 18F-AV-1451 positron emission tomography in Alzheimer’s disease and progressive supranuclear palsy. Brain. 2017;140:781–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lockhart SN, Ayakta N, Winer JR, La Joie R, Rabinovici GD, Jagust WJ. Elevated 18F-AV-1451 PET tracer uptake detected in incidental imaging findings. Neurology. 2017;88:1095–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong J, Meyer JH, Furukawa Y, Boileau I, Chang LJ, Wilson AA, et al. Distribution of monoamine oxidase proteins in human brain: implications for brain imaging studies. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:863–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saura J, Luque JM, Cesura AM, Da Prada M, Chan-Palay V, Huber G, et al. Increased monoamine oxidase B activity in plaque-associated astrocytes of Alzheimer brains revealed by quantitative enzyme radioautography. Neuroscience. 1994;62:15–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klunk WE, Koeppe RA, Price JC, Benzinger TL, Devous MDS, Jagust WJ, et al. The Centiloid Project: standardizing quantitative amyloid plaque estimation by PET. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(1):15e1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basu S, DasGupta A. The mean, median, and mode of unimodal distributions:a characterization. Theory Probab Appl. 1997;41: 210–23. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joshi A, Koeppe RA, Fessler JA. Reducing between scanner differences in multi-center PET studies. NeuroImage. 2009;46:154–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.