Abstract

Background

Eribulin has significantly improved overall survival (OS) for patients with metastatic breast cancer who received ≥ 2 prior chemotherapy regimens for advanced disease. This trial assessed eribulin as adjuvant therapy for patients with early-stage breast cancer.

Methods

Patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative, stage I–III breast cancer received doxorubicin 60mg/m2 and cyclophosphamide 600mg/m2 intravenously (IV) on Day (D)1 of each 14-day cycle for 4 cycles, with pegfilgrastim on D2; followed by 4 cycles of eribulin mesylate 1.4mg/m2 IV on D1 and D8 every 21 days. There were 2 cohorts—cohort 1: no prophylactic growth factor with eribulin (allowed at physician’s discretion only); cohort 2: prophylactic filgrastim with eribulin. The primary endpoint was feasibility. Relative dose intensity of eribulin and toxicities are summarized by cohort. Exploratory endpoints included 3-year disease-free survival (DFS) and OS.

Results

81 Patients (cohort 1, n=55; cohort 2, n=26) entered the treatment phase; 88% completed treatment. Feasibility was 72.9 % (90% CI, 60.4, 83.2) in cohort 1 and 60.0% (90% CI, 41.7, 76.4) in cohort 2. The most frequent eribulin-related adverse events (AEs; all grades) were fatigue (75.9%), peripheral neuropathy (54.4%), nausea (39.2%), neutropenia (35.4% [31.5% of patients in cohort 1; 44.0% in cohort 2]), and arthralgia (26.6%).

Conclusions

The primary endpoint of >80% feasibility was not met. No unexpected AEs were observed and 62% of patients achieved full dosing with no dose delay or reduction. Further investigation of this regimen with alternative dosing schedules or use of growth factors could be considered.

Keywords: phase 2, eribulin, dose-dense doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide, HER2-negative breast cancer, growth factor

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer among women.1 An estimated 252,710 new cases of breast cancer will be diagnosed in 2017 in the United States, accounting for 15% of total cancer cases.2 Anthracycline- and taxane-containing adjuvant regimens are a standard of care for the treatment of early-stage breast cancer in women who are at high risk for recurrence with dose dense therapy demonstrating improved overall survival over conventional scheduling.3,4 Although there has been progress in the development of adjuvant systemic therapy for breast cancer, there is still a significant unmet medical need for patients with high-risk or poor-prognosis early-stage breast cancer.5

Eribulin is a microtubule inhibitor that belongs to the halichondrin class of antineoplastic drugs.6 It is a pharmaceutically optimized, fully synthetic analogue of halichondrin B, a natural occurring macrolide isolated from the marine sponge Halichondria okadai.7 Eribulin has a novel mode of action that is distinct from that of other tubulin-targeting drugs including both taxanes and vinca alkaloids: it induces irreversible mitotic blockade by binding to a small number of high-affinity sites on the growing (plus) ends of microtubules to inhibit their growth, but has no measurable effect on microtubule shortening.8,9 Eribulin also exhibits a range of additional, non-mitotic, complex effects on tumor biology, including induction of vascular remodeling, suppression of cancer-cell migration and invasion, and reversal of the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition.10-12

Eribulin is approved for the treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer who have previously received at least 2 (in the United States) or at least 1 (in the European Union) chemotherapeutic regimens in the metastatic setting, including an anthracycline and a taxane in any setting.13-15 The efficacy and safety of eribulin have been demonstrated in a number of trials in patients with anthracycline- and taxane-pretreated metastatic breast cancer15 and in patients in an earlier-line chemotherapeutic setting.16,17 The survival benefit of eribulin in patients with advanced or metastatic HER2-negative disease provides a rationale for assessing the efficacy of eribulin in the adjuvant setting. This phase 2, single-arm, open-label study assessed the feasibility of administering eribulin as adjuvant therapy following dose-dense AC in patients with early-stage (I–III), HER2-negative breast cancer.

Methods

Patients

Eligible patients were ≥18 years old with histologically confirmed diagnosis of stage I–III invasive breast cancer that was HER2-negative. HER2-negative status was defined as an immunohistochemistry score of 0/1+ or an absence of HER2 amplification as determined by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Eligible patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1 and had adequate cardiac, renal, bone marrow, and liver function. Key exclusion criteria included prior chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy, or biotherapy for current breast cancer, nonmalignant systemic disease that would preclude any of the study drugs, and patients with a concurrently active second malignancy other than adequately treated nonmelanoma skin cancers or in situ cervical cancer.

Study Design and Treatment

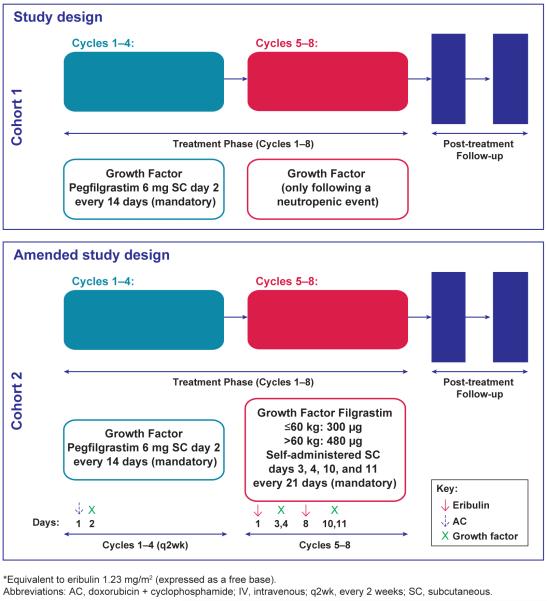

All patients received a dose-dense AC regimen of doxorubicin 60 mg/m2 intravenously (IV) and cyclophosphamide 600 mg/m2 IV on day 1 of each 14-day cycle for 4 cycles. Pegfilgrastim 6 mg subcutaneously (SC) was administered on day 2 of each AC cycle. Substitution of filgrastim for pegfilgrastim was permitted at the discretion of the treating physician. Following the dose-dense AC regimen, patients received eribulin mesylate 1.4 mg/m2 (equivalent to eribulin 1.23 mg/m2 [expressed as a free base]), administered IV over 2–5 minutes on day 1 and day 8 of each 21-day cycle for 4 cycles (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study design

Complete blood count was monitored with eribulin therapy with parameters for treatment requiring: absolute neutrophil count (ANC) > 1000 cells/ mm3 and platelets >75,000 cells/ mm3. A reduction in eribulin mesylate dose to 1.1 mg/m2 occurred for hematologic adverse events including any grade 3 or 4 event in the previous cycle recovered to grade ≤ 2, ANC < 500 cells/mm3 for > 7 days, ANC < 1000 cells/mm3 with fever or infection, platelets < 25,000 cells/mm3, and platelets < 50,000 cells/mm3 requiring transfusion and for non-hematologic adverse events including any Grade 3 or 4 event in the previous cycle recovered to Grade ≤ 2 in ≤ 7 days. A complete listing of recommended dose modifications for eribulin are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Recommended dose reductions for eribulin.

| Adverse reaction | Eribulin Dose Modification |

|---|---|

| Hematologic: Any grade 3 or 4 event in the previous cycle, recovered to grade ≤ 2: ANC < 500 cells/mm3 for > 7 days ANC < 1000 cells/mm3 with fever or infection Platelets < 25 000 cells/mm3 Platelets < 50 000 cells/mm3 requiring transfusion |

1.1 mg/m2 |

| Nonhematologic: Any Grade 3 or 4 event in the previous cycle recovered to Grade ≤ 2 in ≤ 7 days |

1.1 mg/m2 |

| All: Omission or delay of day 8 eribulin dose in previous cycle for toxicity |

1.1 mg/m2 |

| Occurrence of any event requiring dose reduction while receiving 1.1 mg/m2 eribulin |

0.7 mg/m2 |

| Occurrence of any event requiring dose reduction while receiving 0.7 mg/m2 eribulin |

Discontinuation |

ANC, absolute neutrophil count.

In the original study design (cohort 1), after entry to the eribulin treatment phase, growth factor (pegfilgrastim or filgrastim) was administered only at the treating physician’s discretion following a neutropenic event. However, due to the number of neutropenic events during the eribulin portion of this regimen, the study design was amended to include a second cohort (cohort 2) in which administration of prophylactic growth factor with eribulin therapy was required. Cohort 2 received an empirically designed short course of prophylactic filgrastim at a dose of 300 μg for patients ≤ 60 kg or 480 מg for patients > 60 kg that was self-administered SC on days 3, 4, 10, and 11 of each eribulin 21-D cycle.

This study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by an Institutional Review Board. All patients provided informed consent prior to any study-specific procedures being performed.

Endpoints and Assessments

The primary endpoint was feasibility of dose-dense AC for 4 cycles followed by eribulin for 4 cycles in the adjuvant setting. Feasibility was defined as the percentage of patients who completed the eribulin portion of the regimen without a dose omission, delay, or reduction due to an eribulin-related adverse event (AE). A dose delay was defined as a delay due to an eribulin-related AE of >2 days for subsequent doses or cycles after the full dose of eribulin was administered. A feasibility rate of 80% was set as the threshold, based on historical data from adjuvant trials in which >80% of patients completed the intended treatment regimen without dose delay or reduction.18-21 Patients were considered not evaluable if there was an event of study drug dose omission, delay, reduction, or withdrawal for which eribulin could be excluded as the attribution agent. Relative dose intensity (RDI) of eribulin treatment was a secondary endpoint of feasibility and was defined as the total actual dose of eribulin divided by the total planned dose of eribulin.

The secondary endpoint was to evaluate the toxicities associated with 4 cycles of AC followed by 4 cycles of eribulin. Safety assessments included monitoring and recording of all AEs and serious AEs (SAEs) based on the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0. Exploratory endpoints included 3-year disease-free survival (DFS) and 3-year overall survival (OS).

Statistical Analysis

The full analysis set comprised all patients who received at least 1 dose of AC, and the eribulin-treated analysis set comprised all patients who received at least 1 dose of eribulin. The safety analysis set comprised all patients who were enrolled, received at least 1 dose of study treatment, and had at least 1 posttreatment safety assessment. The eribulin-treated safety analysis set comprised all patients who were enrolled, received at least 1 dose of eribulin treatment, and had at least 1 post-eribulin treatment safety assessment.

Feasibility rates were calculated separately for each of the 2 cohorts. The proportion of patients who completed the eribulin portion of the regimen without a dose omission, delay, or reduction due to an eribulin-related AE were estimated via the observed completion rate, and an exact 90% confidence interval (CI) was constructed. 3-Year DFS and 3-year OS were analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method and were summarized for the overall study population and the 2 individual cohorts.

Results

Patients

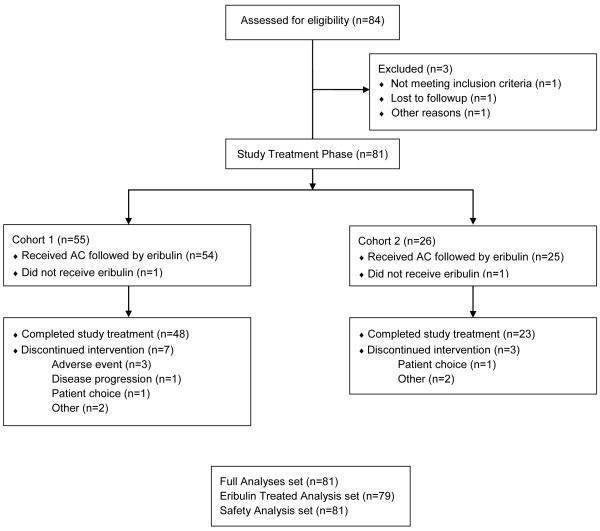

In this phase 2 study, 84 patients were enrolled, 3 of who were screen failures, resulting in 81 patients entering the study-treatment phase (n=55 patients in cohort 1; n=26 patients in cohort 2) (Figure 2). While all 81 patients received AC treatment, 2 patients (1 in each cohort) did not receive eribulin following AC treatment (patient choice, n=1; per protocol due to >2 weeks of treatment delays, n=1). The remaining 79 patients received eribulin following AC treatment (n=54 in cohort 1; n=25 in cohort 2) (Figure 2). Demographic and baseline characteristics were generally similar between cohorts (Table 2). Patients had a median age of 49 years (range: 26-69). The majority of the patients were white (67.9%). Demographic and baseline characteristics were generally similar between cohorts, however there were more African American patients in cohort 2. African Americans comprised 18.5% of the total patient population and 30.8% of the patients in cohort 2. The majority of patients (85.2%) had an ECOG performance status of 0.

Figure 2.

Patient Disposition

Table 2. Demographics and baseline characteristics in the full analysis set.

| Characteristic | Cohort 1 n = 55 |

Cohort 2 n =26 |

Total N = 81 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (range) | 50.0 (26, 65) | 47.5 (36, 69) | 49.0 (26, 69) |

| Women, n (%) | 55 (100.0) | 26 (100.0) | 81 (100.0) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 42 (76.4) | 13 (50.0) | 55 (67.9) |

| Black or African American | 7 (12.7) | 8 (30.8) | 15 (18.5) |

| Asian | 3 (5.5) | 1 (3.8) | 4 (4.9) |

| Othera | 3 (5.5) | 3 (11.5) | 6 (7.4) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (3.8) | 1 (1.2) |

| ECOG status, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 46 (83.6) | 23 (88.5) | 69 (85.2) |

| 1 | 7 (12.7) | 3 (11.5) | 10 (12.3) |

| Missing | 2 (3.6) | 0 | 2 (2.5) |

| ER/PR status, n (%) | |||

| ER+ or PR+ | 43 (78.2) | 19 (73.1) | 62 (76.5) |

| ER− and PR− (ie, TNBC) | 12 (21.8) | 7 (26.9) | 19 (23.5) |

| Cancer stage, n (%) | |||

| I | 12 (21.8) | 5 (19.2) | 17 (21.0) |

| II | 33 (60.0) | 13 (50.0) | 46 (56.8) |

| III | 10 (18.2) | 8 (30.8) | 18 (22.2) |

American Indian, Alaskan Native, or unknown.

Abbreviations: ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ER = estrogen receptor; PR = progesterone receptor; TNBC = triple-negative breast cancer.

Feasibility

Of the 81 patients who received study treatment, 73 (90%) were considered evaluable for feasibility. Of the 8 nonevaluable patients, 2 patients did not receive eribulin treatment, 2 discontinued treatment (patient choice, progressive disease) and the remaining 4 patients had 5 AEs (hypertension, paronychia, pyrexia, upper respiratory infection, tooth abscess) leading to study drug dose omissions, delays, reductions, or withdrawals that were not attributable to eribulin. The feasibility threshold of 80% was not reached in either cohort 1 or cohort 2 (Table 3), with a feasibility rate of 72.9% (90% CI 60.4, 83.2) in cohort 1 and 60.0% (90% CI 41.7, 76.4) in cohort 2. There was no difference in the feasibility rate between cohorts (P = 0.2958).

Table 3. Analysis of feasibility (eribulin-treated analysis set, evaluable patients).

| Evaluable | Cohort 1 (n=48) | Cohort 2 (n=25) | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feasible, n | 35 | 15 | |

|

|

|||

| Feasibilityb (%) | 72.9 | 60.0 | 0.2958 |

|

|

|||

| 90% Confidence intervalc | 60.4, 83.2 | 41.7, 76.4 | |

Exploratory analysis: comparing primary feasibilities between 2 cohorts, based on Fisher’s Exact test.

Feasibility = feasible patient n/N × 100.

90% confidence interval is based on exact method.

Exposure and Safety

The extent of exposure to eribulin in the eribulin-treated analysis set is summarized in Table 4. Of the 79 patients who received eribulin following dose-dense AC, 71 (89.9%) completed study treatment. The mean RDI per patient was 92.0 in cohort 1 and 90.9 in cohort 2 (Table 4). The most frequent (≥30%, any grade) eribulin-related treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) were fatigue (n=60, 75.9%), peripheral neuropathy (n=43, 54.4%), nausea (n=31, 39.2%), and neutropenia (n=28, 35.4%). Eribulin-related TEAEs of all grades that occurred in at least 10% of patients in either cohort, and TEAEs that occurred at Grades 3 or 4 are summarized in Table 5. The most common hematological TEAE was neutropenia, with an overall incidence of 35.4% (n=28; Grade 3 or 4: 27.8%, n=22,). Neutropenic events, of all grades, were reported in 31.5% (n=17) of patients in cohort 1 and 44.0% (n=11) of patients in cohort 2. Eribulin-related febrile neutropenia occurred in 2 patients (both grade 3), 1 in each cohort. The timing of dose delays due to neutropenia was variable across both cohorts and occurred on both cycle day 1 and day 8 (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 4. Extent of exposure to eribulin in eribulin-treated patients.

| Group | Cohort 1 n = 54 |

Cohort 2 n = 25 |

Total n = 79 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Completed study treatment, n (%) | 48 (88.9) | 23 (92.0) | 71 (89.9) |

| Relative dose intensity per patient %,a mean (SD) |

92.0 (17.0) | 90.9 (18.2) | 91.7 (17.3) |

| Patients with any dose modification, n (%) | |||

| Dose reductionb | 13 (24.1) | 9 (36.0) | 22 (27.8) |

| Dose delay | 13 (24.1) | 9 (36.0) | 22 (27.8) |

| Dose interruption | 0 | 1 (4.0) | 1 (1.3) |

| Permanent discontinuation due to adverse event |

3 (5.6) | 0 | 3 (3.8) |

| Dose missing | 5 (9.3) | 4 (16.0) | 9 (11.4) |

| Duration of dose delays,c n (%) | |||

| < 1 week | 2 (3.7) | 0 | 2 (2.5) |

| 1 to < 2 weeks | 11 (20.4) | 9 (36.0) | 20 (25.3) |

Relative dose intensity = total actual dose of eribulin divided by the total planned dose of eribulin.

Dose reduction does not include the cases of missed dose.

Based on worst (longest) dose delay recorded; score = 0 if no dose delay.

Abbreviations:SD, standard deviation.

Table 5. Eribulin-related TEAEs occurring in at least 10% of patients* in any cohort in the eribulin-treated safety analysis set.

| TEAEs, n (%) | Total n = 79 |

Cohort 1 n = 54 |

Cohort 2 n = 25 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred Term | Any Grade |

Grade 3-4 | Any Grade |

Grade 3-4 | Any Grade |

Grade 3-4 |

| Fatigue | 60 (75.9) | 1 (1.3) | 43 (79.6) | 1 (1.9) | 17 (68.0) | 0 |

| Neuropathy peripheral | 43 (54.4) | 1 (1.3) | 32 (59.3) | 1 (1.9) | 11 (44.0) | 0 |

| Nausea | 31 (39.2) | 1 (1.3) | 18 (33.3) | 1 (1.9) | 13 (52.0) | 0 |

| Neutropenia | 28 (35.4) | 22 (27.8) | 17 (31.5) | 12 (22.2) | 11 (44.0) | 10 (40.0) |

| Arthralgia | 21 (26.6) | 1 (1.3) | 14 (25.9) | 1 (1.9) | 7 (28.0) | 0 |

| Dry eye | 13 (16.5) | 1 (1.3) | 6 (11.1) | 0 | 7 (28.0) | 1 (4.0) |

| Leukopenia | 12 (15.2) | 5 (6.3) | 11 (20.4) | 5 (9.3) | 1 (4.0) | 0 |

| Menstruation irregular | 11 (13.9) | 1 (1.3) | 6 (11.1) | 0 | 5 (20.0) | 1 (4.0) |

| Vomiting | 10 (12.7) | 1 (1.3) | 7 (13.0) | 1 (1.9) | 3 (12.0) | 0 |

| Mucosal inflammation | 10 (12.7) | 1 (1.3) | 6 (11.1) | 0 | 4 (16.0) | 1 (4.0) |

Only those preferred terms with TEAEs (any grade) occurring in at least 10% of patients in any cohort and that also occurred at Grades 3–4 are included. TEAE = treatment-emergent adverse event.

In the eribulin-treated safety analysis set (n=79), 3 patients in cohort 1 (5.6%) and 0 patients in cohort 2 discontinued study treatment due to TEAEs (neutropenia, peripheral neuropathy, and hypertension). A total of 25 (31.6%) patients had a TEAE that resulted in either treatment interruption or dose reduction of eribulin. Grade 3 or 4 neutropenia was the most common TEAE requiring dose modification (20 patients total, 25.3%; 10 patients in each cohort). In the safety analysis set (n=81), the occurrence of SAEs was low (12.3%). Nonfatal SAEs were observed in 6 patients (10.9%) in cohort 1 and 4 patients (15.4%) in cohort 2. There were no Grade 5 events. The safety profile of eribulin in this study was consistent with the known safety profile of eribulin, and no new or unexpected safety signals were observed.

Survival

As of data cutoff (28 Apr 2015), the 3-year DFS rate for patients in the eribulin-treated analysis set was 89.5%. Three patients developed MBC and 2 patients had ipsilateral locoregional recurrence. The median follow-up times for DFS were 32.2 months (range: 2.6–44.8 months) for cohort 1 and 12.9 months (range: 3.8–20.4 months) for cohort 2. Median DFS was not evaluable at the time of analysis.

The 3-year OS rate for patients in the eribulin-treated analysis set was 97.1%. 3 Patients (3.8%) died due to progressive disease. The median follow-up times for OS were 33.9 months (range: 4.2–44.8 months) for cohort 1 and 12.9 months (range: 4.8–20.4 months) for cohort 2. Median OS was not evaluable at the time of analysis.

Discussion

The aim of this phase 2 study was to evaluate the feasibility of administering eribulin as an adjuvant therapy following dose-dense AC in patients with early-stage, HER2-negative, breast cancer. In the pivotal EMBRACE (eribulin monotherapy versus treatment of physician’s choice in patients with metastatic breast cancer) phase 3 study eribulin demonstrated a statistically significant OS advantage in patients with heavily pretreated metastatic breast cancer compared with TPC (13.1 months vs 10.6 months for eribulin and treatment of physician’s choice, respectively; hazard ratio [HR] 0.81, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.66–0.99; P=0.041) with a manageable safety profile.15 A subgroup analysis from a subsequent phase 3 study (study 301) that evaluated eribulin versus capecitabine in the first-, second-, or third-line setting for advanced/metastatic disease found that HER2-negative patients treated with eribulin demonstrated an OS benefit of 2.4 months (15.9 vs 13.5 months for eribulin and capecitabine, respectively; HR 0.84; P=0.03).22 Further, in a pooled analysis of EMBRACE/301 studies, eribulin treatment significantly prolonged OS compared with control treatment in subgroups of patients with HER2-negative disease (15.2 vs 13.3 months; HR 0.82; P=0.002) and with triple-negative disease (12.9 vs 8.2 months; HR 0.74; P=0.006).23 Additionally, evidence from phase 2 trials demonstrated the clinical activity of eribulin in the first-line setting in locally recurrent or metastatic HER2-negative breast cancer.16,24 These compelling data in support of the clinical activity of eribulin for metastatic breast cancer led to interest incorporating eribulin into an anthracycline-based adjuvant regimen.

Dose-dense chemotherapy with anthracycline and paclitaxel is a preferred regimen for HER2-negative breast cancer in the adjuvant/neoadjuvant setting.3 However, common side effects observed with taxanes include neuropathy, myalgia, and arthralgia.25 The most frequent (≥30%, any grade) eribulin-related treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) were fatigue, peripheral neuropathy, nausea, and neutropenia. All of these TEAEs are consistent with the known safety profile of eribulin in breast cancer. Neutropenia was the most common hematological TEAE, occurring in 35.4% of patients (at all grades) and 27.8% of patients (at grade 3 or 4).

Phase 2 clinical trial data suggest that eribulin may exhibit less neurotoxicity and myalgia/arthralgia, as compared to ixabepilone.26 Although the patient number in this study is small, grade 3-4 peripheral neuropathy occurred in 1% of total patients, which is thought provoking in the setting of adjuvant breast cancer therapy where neuropathy may have long term impact on quality of life.27 Previous data have suggested that taxane therapy in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer, is associated with grade 3-4 peripheral neuropathy rates of 6-10%.28,29 As of data cutoff (28 Apr 2015), the 3-year DFS rate and the 3-year overall survival rate for all patients was 89.5% and 97.1% respectively. At the time of analysis, median DFS and median OS were non-evaluable. The median follow-up times for DFS were 32.2 months (range: 2.6–44.8 months) for cohort 1 and 12.9 months (range: 3.8–20.4 months) for cohort 2. Median follow-up times for OS were 33.9 months (range 4.2 – 44.8 months) for Cohort 1 and 12.9 months (range 4.8 – 20.4 months) for Cohort 2.

Feasibility was the primary endpoint of this study. Data from previous studies indicate that more than 80% of the patients in standard adjuvant trials completed the planned therapeutic regimen without a dose delay or reduction.18,19,21 Therefore, the target for feasibility for this phase 2 study was set at 80%. However, this target was not met for either cohort, primarily driven by the incidence of neutropenia—the most common treatment-related TEAE leading to eribulin dose reduction or interruption. However, a total of 50/73 (68.5%) evaluable patients achieved full dosing without dose delay or reduction (35/48 patients [72.9%] in cohort 1; 15/25 [60.0%] in cohort 2). In addition, the average relative dose intensities for eribulin in eribulin-treated patients were greater than 90% in both cohorts. The administration of eribulin following dose-dense AC in patients was well-tolerated, with very few patients (4%) discontinuing eribulin because of TEAEs.

An alternative dosing schedule for administering growth factor may contribute to a more favorable tolerability profile for AC+eribulin. It is noteworthy that growth factor in this study was administered as a short course on days 3, 4, 10, and 11 of eribulin cycles. Changes in the quantity and/or frequency of growth factor support following eribulin treatment may have an impact on observed neutropenia rates and warrants consideration of further investigation in this setting. However, the design and selection of an appropriate G-CSF regimen requires a balance between functional adequacy (ie, controlling neutropenia), patient and physician practicality, and economic feasibility. These factors contributed to the empirical design of the G-CSF schedule in this study, with the goal of safely managing neutropenia while minimizing impact to patients.

The treatment sequence of an anthracycline-based regimen followed by a taxane is traditional of adjuvant trials of taxanes in early breast cancer; this is primarily due to the introduction of anthracyclines into clinical practice prior to taxanes. Several studies evaluating the role of different anthracycline and taxane sequences in the adjuvant setting have demonstrated that the reverse sequence is acceptable.30 For example, in a randomized phase 2 study of patients with node-positive breast cancer, dose-dense docetaxel followed by doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide resulted in fewer dose reductions (46% versus 18%) than the reverse sequence.31 The administration of eribulin prior to dose-dense AC may improve the feasibility of this regimen, but requires formal investigation in this setting.

Conclusion

The primary endpoint of feasibility for eribulin following dose dense AC was not met. Further, amendment of the protocol to include the administration of an empirically designed brief (2-day) duration of growth factor following eribulin treatment did not improve feasibility. Nevertheless, eribulin treatment as an adjuvant therapy following dose-dense AC in patients with early-stage, HER2-negative, breast cancer was tolerable and the majority of patients completed the planned treatment with no dose delay or reduction. Further investigation into alternative dosing schedules or use of growth-factors is recommended.

Supplementary Material

Microabstract.

We investigated eribulin as adjuvant therapy following dose-dense doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide for patients with HER2-negative early-stage breast cancer.

The primary endpoint of feasibility of this regimen was not met, even with mandatory prophylactic growth factor support with eribulin treatment.

Unexpected adverse events were not observed with this regimen and the majority of patients achieved full dosing without dose delay or reduction.

Clinical Practice Points: 238/250.

Dose-dense chemotherapy with sequential paclitaxel is a preferred regimen for HER2-negative breast cancer in the adjuvant/neoadjuvant setting. However, common side effects observed with taxanes include neuropathy, myalgia, and arthralgia. The efficacy and safety of eribulin have been demonstrated in a number of randomized phase 3 trials in patients with anthracycline- and taxane-pretreated metastatic breast cancer and in patients in an earlier-line chemotherapeutic setting. Eribulin is a microtubule inhibitor that has a novel mode of action that is distinct from that of other tubulin-targeting drugs including both taxanes and vinca alkaloids. Eribulin also exhibits a range of additional, non-mitotic, complex effects on tumor biology, including induction of vascular remodeling, suppression of cancer cell migration and invasion, and reversal of the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Given its clinical activity in improving OS in patients with locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer, we aimed to investigate eribulin in the adjuvant setting following dose dense doxorubicin+cyclophosphamide (AC).

In this study, the primary endpoint of feasibility for the regimen was not met. Further, amendment of the protocol to include the administration of an empirically designed brief duration of growth factor following eribulin treatment did not improve feasibility. Nevertheless, eribulin treatment as an adjuvant therapy following dose-dense AC in patients with early-stage, HER2-negative, breast cancer was tolerable as the majority of patients completed the planned treatment with no dose delay or reduction. Further investigation of this regimen with alternative dosing schedules or use of growth-factors is recommended.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Erhan Berrak and James Song for their contributions to this manuscript.

Funding:

This study was sponsored by Eisai Inc., Woodcliff Lake, NJ, USA. Medical writing and editorial assistance was provided by Oxford PharmaGenesis, Newtown, PA and was funded by Eisai. KAC and TAT were in part supported in the preparation of this study by NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant No. P30 CA008748 to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest disclosure: Karen Cadoo has nothing to disclose. Peter Kaufman reports grants and advisory board fees from Eisai. Andrew Seidman reports personal fees for speakers’ bureau and advisory boards from Eisai. Cassandra Chang has nothing to disclose. Dongyuan Xing is an employee of Eisai Inc. Tiffany Traina reports non-financial support for advisory boards from Eisai and advisory board fees from Genomic Health.

References

- 1.International Agency for Research on Cancer; World Health Organization. [August 2, 2017];Cancer Fact Sheets: Breast Cancer. http://globocan.iarc.fr/old/FactSheets/cancers/breast-new.asp.

- 2.National Cancer Institute. [August 2, 2017];SEER Cancer Statistics Factsheets: Female Breast Cancer. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html.

- 3.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) [August 2, 2017];Breast Cancer. 2017 doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0146. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Senkus E, Kyriakides S, Ohno S. et al. Primary breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(Suppl 5):v8–v30. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Food and Drug Administration; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) [August 2, 2017];Guidance for Industry Pathological Complete Response in Neoadjuvant Treatment of High-Risk Early-Stage Breast Cancer: Use as an Endpoint to Support Accelerated Approval. 2014 https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM305501.pdf.

- 6.Smith JA, Wilson L, Azarenko O. et al. Eribulin binds at microtubule ends to a single site on tubulin to suppress dynamic instability. Biochemistry. 2010;49:1331–1337. doi: 10.1021/bi901810u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Towle MJ, Salvato KA, Budrow J. et al. In vitro and in vivo anticancer activities of synthetic macrocyclic ketone analogues of halichondrin B. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1013–1021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okouneva T, Azarenko O, Wilson L, Littlefield BA, Jordan MA. Inhibition of centromere dynamics by eribulin (E7389) during mitotic metaphase. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:2003–2011. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jordan MA, Kamath K, Manna T. et al. The primary antimitotic mechanism of action of the synthetic halichondrin E7389 is suppression of microtubule growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:1086–1095. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dybdal-Hargreaves NF, Risinger AL, Mooberry SL. Eribulin mesylate: mechanism of action of a unique microtubule-targeting agent. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:2445–2452. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Funahashi Y, Okamoto K, Adachi Y. et al. Eribulin mesylate reduces tumor microenvironment abnormality by vascular remodeling in preclinical human breast cancer models. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:1334–1342. doi: 10.1111/cas.12488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshida T, Ozawa Y, Kimura T. et al. Eribulin mesilate suppresses experimental metastasis of breast cancer cells by reversing phenotype from epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) to mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) states. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:1497–1505. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halaven 0.44 mg/ml solution for injection [summary of product characteristics] Eisai Europe Limited; Hertfordshire, UK: [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halaven (eribulin mesylate) injection [prescribing information] Eisai Inc; Woodcliff Lake, NJ: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cortes J, O'Shaughnessy J, Loesch D. et al. Eribulin monotherapy versus treatment of physician's choice in patients with metastatic breast cancer (EMBRACE): a phase 3 open-label randomised study. Lancet. 2011;377:914–923. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McIntyre K, O'Shaughnessy J, Schwartzberg L. et al. Phase 2 study of eribulin mesylate as first-line therapy for locally recurrent or metastatic human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;146:321–328. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2923-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maeda S, Saimura M, Minami S. et al. Efficacy and safety of eribulin as first- to third-line treatment in patients with advanced or metastatic breast cancer previously treated with anthracyclines and taxanes. Breast. 2017;32:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2016.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Citron ML, Berry DA, Cirrincione C. et al. Randomized trial of dose-dense versus conventionally scheduled and sequential versus concurrent combination chemotherapy as postoperative adjuvant treatment of node-positive primary breast cancer: first report of Intergroup Trial C9741/Cancer and Leukemia Group B Trial 9741. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1431–1439. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henderson IC, Berry DA, Demetri GD. et al. Improved outcomes from adding sequential Paclitaxel but not from escalating Doxorubicin dose in an adjuvant chemotherapy regimen for patients with node-positive primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:976–983. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mamounas EP, Bryant J, Lembersky B. et al. Paclitaxel after doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide as adjuvant chemotherapy for node-positive breast cancer: results from NSABP B-28. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3686–3696. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buzdar AU, Singletary SE, Valero V. et al. Evaluation of paclitaxel in adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with operable breast cancer: preliminary data of a prospective randomized trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1073–1079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Twelves C, Awada A, Cortes J. et al. Subgroup analyses from a phase 3, open-label, randomized study of eribulin mesylate versus capecitabine in pretreated patients with advanced or metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer (Auckl) 2016;10:77–84. doi: 10.4137/BCBCR.S39615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Twelves C, Cortes J, Vahdat L. et al. Efficacy of eribulin in women with metastatic breast cancer: a pooled analysis of two phase 3 studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;148:553–561. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3144-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takashima T, Tokunaga S, Tei S. et al. A phase II, multicenter, single-arm trial of eribulin as first-line chemotherapy for HER2-negative locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. Springerplus. 2016;5:164. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-1833-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rampurwala MM, Rocque GB, Burkard ME. Update on adjuvant chemotherapy for early breast cancer. Breast Cancer (Auckl) 2014;8:125–133. doi: 10.4137/BCBCR.S9454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vahdat LT, Garcia AA, Vogel C. et al. Eribulin mesylate versus ixabepilone in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a randomized Phase II study comparing the incidence of peripheral neuropathy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;140:341–351. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2574-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hurtz HJ, Tesch H, Göhler T. et al. Persistent impairments 3 years after (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: results from the MaTox project. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;165:721–731. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4365-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sparano JA, Wang M, Martino S. et al. Weekly paclitaxel in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1663–1671. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gradishar WJ, Tjulandin S, Davidson N. et al. Phase III trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel compared with polyethylated castor oil-based paclitaxel in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7794–7803. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bines J, Earl H, Buzaid AC, Saad ED. Anthracyclines and taxanes in the neo/adjuvant treatment of breast cancer: does the sequence matter? Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1079–1085. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Puhalla S, Mrozek E, Young D. et al. Randomized phase II adjuvant trial of dose-dense docetaxel before or after doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide in axillary node-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1691–1697. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.3941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.