Abstract

Nebulization is currently used for delivery of antibiotics for respiratory infections. Bacteriophages (or phages) are effective predators of pathogens including Pseudomonas aeruginosa commonly found in the lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis (CF). It is known that phages and antibiotics can potentially show synergistic antimicrobial effect on bacterial killing. In the present study, we investigated synergistic antimicrobial effect of phage PEV20 with five different antibiotics against three P. aeruginosa strains isolated from sputum of CF patients. The antibiotics included ciprofloxacin, tobramycin, colistin, aztreonam and amikacin, which are approved by U.S Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for inhaled administration. Phage and antibiotic synergy was determined by assessing bacterial killing performing time-kill studies. Among the different phage-antibiotic combinations, PEV20 and ciprofloxacin exhibited the most synergistic effect. Two phage-ciprofloxacin combinations, containing 1/4 and 1/2 of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of ciprofloxacin against P. aeruginosa strains FADD1-PA001 (A) and JIP865, respectively were aerosolized using both air-jet and vibrating mesh nebulizers and the synergistic antibacterial activity was maintained after nebulization. Air-jet nebulizer generated droplets with smaller volume median diameters (3.6–3.7 µm) and slightly larger span (2.3–2.4) than vibrating mesh nebulizers (5.1–5.3 µm; 2.1–2.2), achieving a higher fine particle fraction (FPF) of 70%. In conclusion, nebulized phage PEV20 and ciprofloxacin combination shows promising antimicrobial and aerosol characteristics for potential treatment of respiratory tract infections caused by drug-resistant P. aeruginosa.

Keywords: Phage therapy, Bacteriophage, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Respiratory tract infection, Nebulizer, Ciprofloxacin, Antibiotics, Inhalation, Cystic fibrosis

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa[1] has become one of the major causes for respiratory infection in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients[2]. This pathogen also causes chronic infections in patients with obstructive pulmonary disease[3]. To date, five inhalable antibiotics are approved by the U.S Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of respiratory infections: ciprofloxacin, tobramycin, colistin, aztreonam and amikacin. Inhaled antibiotics can deliver high concentrations of drugs to the primary site of infection, which can help to achieve sufficient therapeutic dose and minimize the risks of systemic toxicity[4].

Phage therapy is becoming increasingly encouraging as a treatment option for combating multi-drug-resistant (MDR) bacteria [5]. Unlike antibiotics, phages are highly specific to their target pathogen and thus, should not affect commensal bacteria[6]. Clinical cases using aerosolized phage cocktail to treat CF patient were reported[7]. As bacteria can develop resistance to phages [8–11], strategies to address this have focused on the use of bacteriophage mixes with or without the antibiotics. Over the past few years, studies have repeatedly shown synergistic interaction between antibiotics and phage in vitro [12–16] and in vivo[17, 18]. Therefore, pulmonary delivery of phage and antibiotic combination is a strategic treatment option for respiratory infections caused by MDR P. aeruginosa.

Nebulizers can be practical tools for delivering inhaled phage therapy. Commercially available nebulizers have been tested with phages D29 and PEV44. Carrigy et al[19] reported that active phage delivery rate was greater for vibrating mesh nebulizer (3.3 × 108 ± 0.8 × 108 plaque-forming unit (PFU) /min) than jet nebulizer (5.4 × 104 ± 1.3 × 104 PFU/min). Phage titers were reduced 60 ± 11%, 99.981 ± 0.005%, and 72 ± 14% for vibrating mesh nebulizer, jet nebulizer and soft mist nebulizer after nebulization, respectively. Astudillo et al[20] studied the effect of nebulizers on the morphology of PEV44. The proportion of “broken” phages (the capsid separated from the tail) was higher for air-jet nebulizer (83%) than mesh type nebulizers (50 – 60%). However, vibrating mesh nebulizers are much more costly than the air-jet nebulizer and the latter is more widely used[21].

PEV20 is a podovirus phage that demonstrates antibacterial activity against P. aeruginosa in vitro[22]and in vivo[23]. Spray dried PEV20 powder reduced bacterial load by 5.3-log10 in the lungs of P. aeruginosa-infected mice at 24 h after intratracheal administration[24]. The combined use of phage PEV20 and antibiotics has not been investigated. The purpose of this study was to determine (i) the most synergistic phage-antibiotic liquid combination, (ii) the nebulization performance of the liquid by jet and vibrating mesh nebulizers, and (iii) anti-microbial effect of the nebulized combination.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains

Clinical P. aeruginosa strains (FADD1-PA001, JIP865, 20844n/m(s)) were freshly subcultured from −80 ˚C stock prior to the experiment. Strains FADD1-PA001 and 20844n/m(s) were received from Li group, Monash University, Australia and JIP865 from Iredell group, Westmead Hospital, Australia. These three strains were chosen based on phage sensitivity testing carried out previously [22]. Strain FADD1-PA001, JIP865, 20844n/m(s) were 100%, 75% and 50% killed by phage PEV20. In brief, spot test was carried out and the percentage of killing was calculated as the ratio of the phage titres obtained with the target strains to those with a reference strain.

Bacteriophage

Phage PEV20 was provided by AmpliPhi Biosciences AU at a titre of 1010 PFU/mL in PBS [24]. This phage was formerly isolated from the sewage treatment plant in Olympia (WA, USA) by Kutter lab (Evergreen phage lab).

MIC determination of antibiotics

Ciprofloxacin hydrochloride, amikacin, aztreonam, colistin sulphate and tobramycin sulphate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. The Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antibiotics was determined as per [25] with minor modifications. Briefly, 100 µL of antibiotics (512, 256, 128, 64, 32, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.125 mg/L) were added to 100 µL of early-log phase bacterial culture (106 CFU/mL). The treated culture was incubated overnight at 37 °C with continuous shaking at 150 rpm. MIC was determined to be the concentration of antibiotic at which the optical density (OD600) was equal to that of a cell-free blank control.

Bacterial growth kinetics study

Antibacterial activities of PEV20 and antibiotics were determined by a time-kill curve method[14]. Single colony was inoculated with the wire loop into 20 mL of Nutrient broth for overnight at 37˚C with continuous shaking at 150r rpm. Overnight culture (10 mL) was diluted in 20mL of fresh Nutrient broth and incubate for 2h until it reached early-log phase. Early-log culture was diluted to a final bacterial density of 106 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL. Bacterial culture (200 µL) and 10 µL of antibiotics, phage PEV20 or their combinations were added to each well of a 96-well plate. The plate was incubated at 37 °C with continuous shaking. The study was repeated five times. Sub-inhibitory concentrations of each of the antibiotics in the system were set up at 1/4 MICs for strain FADD1-PA001, and 1/2 MICs for strain JIP865 and 20844n/m(s). Theoretical multiplicity of infection (MOI) were set up at 0.1, 100 and 1000 for strains FADD1-PA001, JIP865 and 20844n/m(s), respectively. Optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was measured at 0, 4, 8 and 24 h using a plate reader (FLUOstar Optima, BMG Lab technologies, Offenburg, Germany).

Nebulization

PEV20-ciprofloxacin combination (4 mL) was nebulized using PARI air-jet nebulizer and a PARI eFlow vibrating-mesh nebulizer. Two PEV20-ciprofloxacin combinations that showed synergy against two clinical P.aeruginosa isolates were tested: 80 µg/mL ciprofloxacin and 2 × 106 PFU/mL PEV20 for strain FADD1-PA001 and 40 µg/mL ciprofloxacin and 2 × 109 PFU/mL PEV20 for strain JIP865. A Suregard® filter was connected to the mouthpiece of an air-jet nebulizer to collect aerosols. For vibrating mesh nebulizer, and a stopper was applied to the mouthpiece to collect aerosols in the chamber. Nebulized samples were subjected to time-kill study. The study was repeated three times.

Aerosol droplet size distribution

The nebulized samples were characterised for aerosol particle size distribution using laser diffraction (Spraytec® Malvern Instruments Ltd., UK). One second measurements over 90 seconds of continuous nebulization were carried out for each of the two nebulizer devices. The results were expressed by the median diameter, and the span which is defined as (D90-D10)/D50, where D10, D50 and D90 are the particle diameter at 10, 50 and 90 percentile of the particle population. Droplets smaller than 5.4 µm were recorded to represent the fine particle fraction (FPF). Droplets smaller than 2.1 µm and larger than 11.6 µm were included to represent anticipated depositions in the alveolar region and the extra-thoracic region, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Bacterial survival rate at 24 h was calculated by dividing OD600 of treatment group with that of negative control group. The additive survival rate was calculated by multiplying bacterial survival rates under the treatment of single phage with that of single antibiotics to represent sum of efficacy. Phage-antibiotic synergy was defined if the observed bacterial survival rate of phage-antibiotic combinations was statistically lower than the calculated additive survival rate [26]. ANOVA was used to compare the logarithmic bacterial survival rate between different groups. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Antibacterial activities of phage PEV20, antibiotics and phage-antibiotic combinations

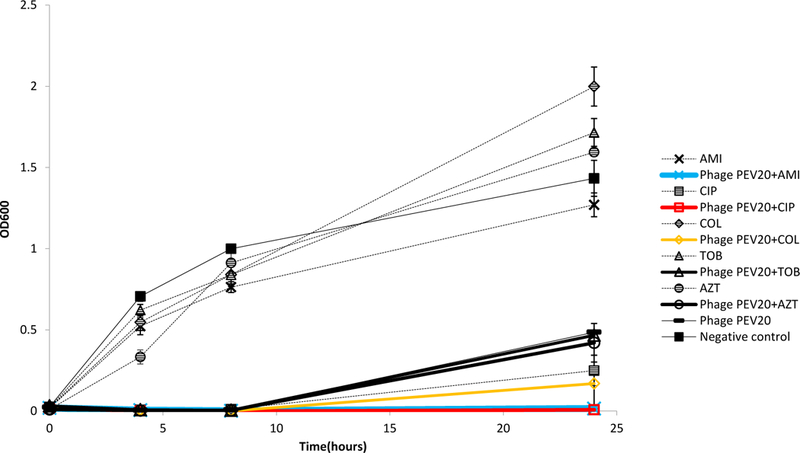

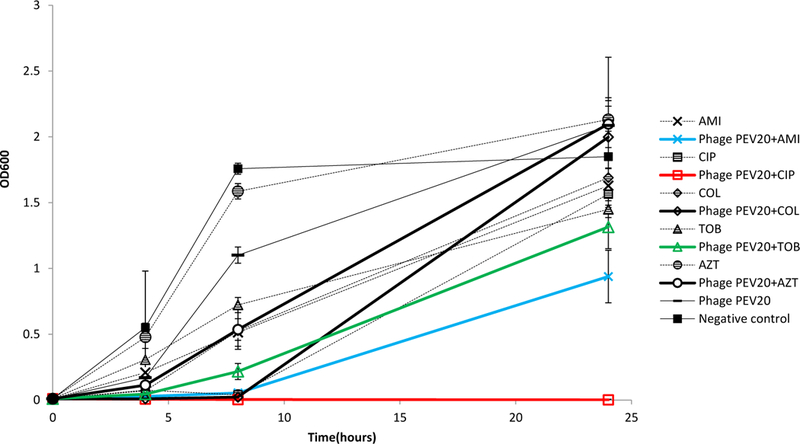

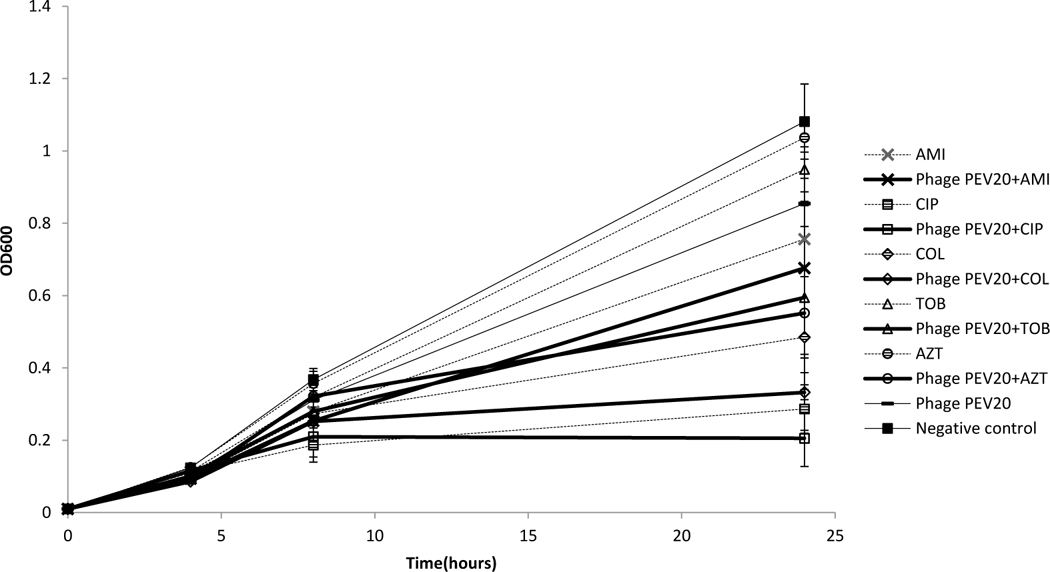

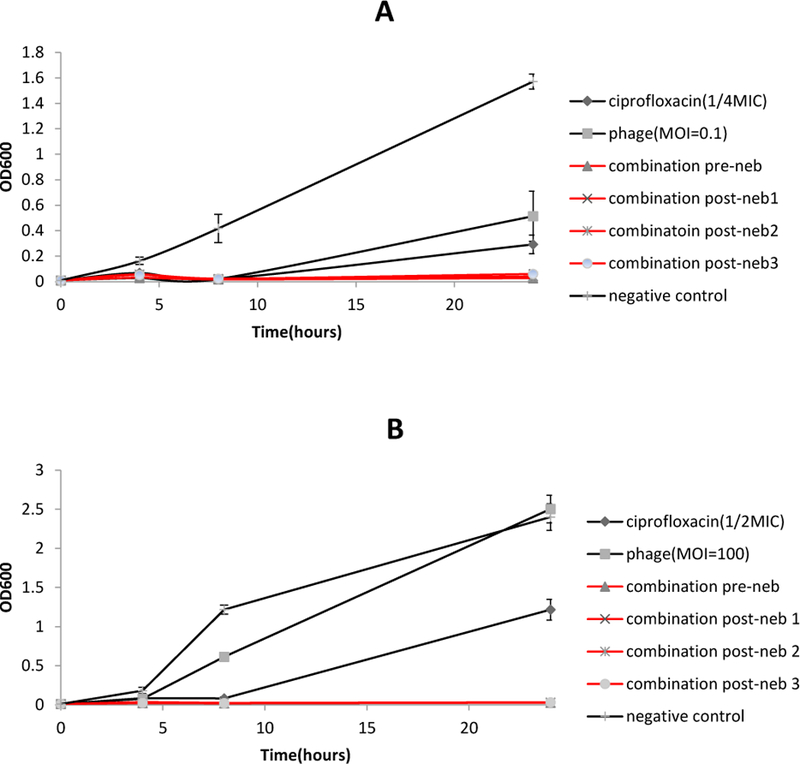

Combinations of PEV20 with ciprofloxacin, amikacin or colistin showed synergistic antibacterial activity against FADD1-PA001 (P<0.05, Table 1). Bacterial density of ciprofloxacin or amikacin in combination with phage PEV20 remained consistently low and did not exhibit any obvious growth throughout 24 h incubation (Figure 1). Combinations of PEV20 with ciprofloxacin, amikacin or tobramycin showed synergistic antibacterial activity against JIP865 (P<0.05, Table1). Only ciprofloxacin in combination with phage PEV20 completely inhibited obvious growth of bacteria (Figure 2). No synergy was observed for aztreonam on FADD1-PA001 or JIP865. For bacterial strain 20844n/m(s), no synergy was observed for all the phage-antibiotic combinations (Figure 3).

Table1.

Calculated and observed bacterial survival after 24 h treatment of phage PEV20 and antibiotic combinations (n=5).

| FADD1-PA001 | JIP865 | 20844n/m(s) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculated | Observed | Calculated | Observed | Calculated | Observed | |

| CIP +PEV20 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.005±0.001* | 1.0±0.2 | 0.001±0.002* | 0.2±0.09 | 0.2±0.02 |

| AMI+PEV20 | 0.3±0.04 | 0.01±0.01* | 1.0±0.1 | 0.5±0.1* | 0.6±0.2 | 0.8±0.3 |

| COL+PEV20 | 0.5±0.07 | 0.2±0.1* | 1.0±0.1 | 1.0±0.2 | 0.4±0.2 | 0.3±0.1 |

| TOB+PEV20 | 0.4±0.07 | 0.3±0.1 | 0.9±0.1 | 0.7±0.1* | 0.7±0.3 | 0.6±0.3 |

| AZT+PEV20 | 0.3±0.04 | 0.3±0.09 | 1.3±0.2 | 1.1±0.2 | 0.8±0.3 | 0.6±0.3 |

Note: Ciprofloxacin (CIP), Tobramycin (TOB), Aztreonam (AZT), Colistin (COL), Amikacin (AMI)

Calculated survival for combinations was the multiplying product of bacteria survival under each individual treatment. Observed survival for combination was the observed OD value under combination treatment divided by that of negative control.

Statistically significant (p<0.05)

Figure 1.

Antibacterial activities of phage PEV20 (MOI=0.1) against P. aeruginosa FADD1-PA001 in the presence of 1/4 MIC of ciprofloxacin (CIP), amikacin (AMI), colistin (COL), tobramycin (TOB), and aztreonam (AZT).(n=5)

Figure 2.

Antibacterial activities of phage PEV20 (MOI=100) against P. aeruginosa JIP865 in the presence of 1/2 MIC of ciprofloxacin (CIP), amikacin (AMI), colistin (COL), tobramycin (TOB), and aztreonam (AZT) (n=5).

Figure 3.

Antibacterial activities of phage PEV20 (MOI=1000) against P. aeruginosa 20844n/m(s) in the presence of 1/2 MIC of ciprofloxacin (CIP), amikacin (AMI), colistin (COL), tobramycin (TOB), and aztreonam (AZT) (n=5).

Nebulization of phage PEV20-ciprofloxacin

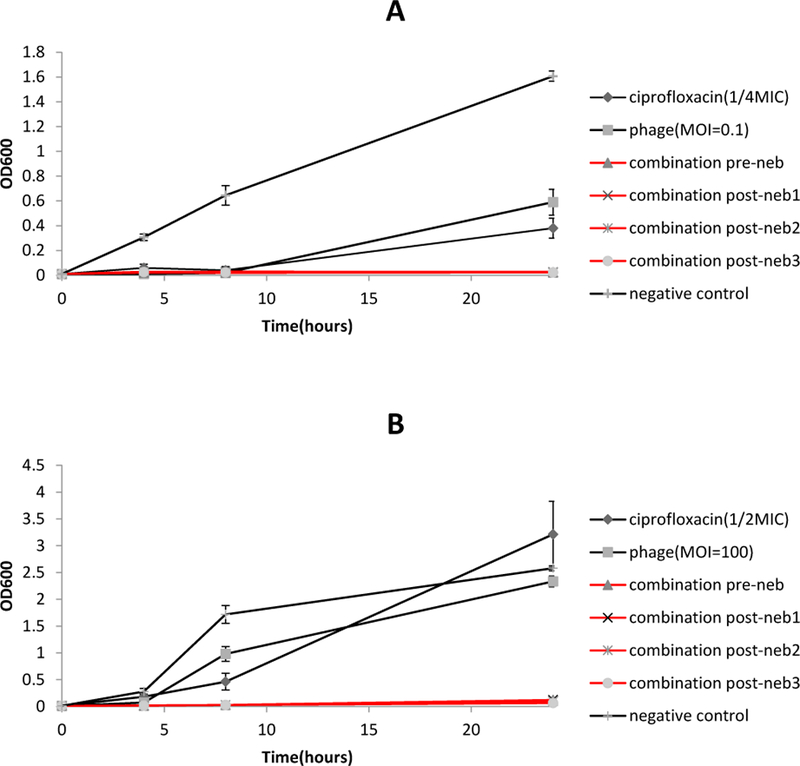

PEV20 and ciprofloxacin combination maintained synergistic antibacterial effect against P. aeruginosa FADD1-PA001 and JIP865 (Table 2) after nebulization using air-jet (Figure 4) or vibrating mesh nebulizers (Figure 5).

Table 2.

Calculated and observed bacterial survival rate of strain FADD1-PA001 or JIP865 of PEV20-ciprofloxacin combination at 24 h of bacterial growth kinetics study before and after nebulization (n=6).

| FADD1- PA001 |

JIP865 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Air-jet nebulizer |

Calculated | 0.06±0.02 | 0.53±0.07 |

| Observed before nebulization |

0.02±0.002* | 0.01±0.006* | |

| Observed after nebulization | |||

| Run 1 | 0.03±0.007* | 0.01±0.003* | |

| Run 2 | 0.02±0.009* | 0.01±0.005* | |

| Run 3 | 0.03±0.008* | 0.01±0.004* | |

| Vibrating mesh nebulizer |

Calculated | 0.09±0.02 | 1.0±0.3 |

| Observed before nebulization |

0.01±0.003* | 0.03±0.007* | |

| Observed after nebulization | |||

| Run 1 | 0.01±0.003* | 0.05±0.002* | |

| Run 2 | 0.02±0.005* | 0.04±0.003* | |

| Run 3 | 0.01±0.001* | 0.03±0.01* | |

Statistically significant (p<0.05) according to ANOVA.

Note: nebulization was carried out in triplicate using both nebulizers.

Figure 4.

Antibacterial activities of phage PEV20, ciprofloxacin and their combination against P. aeruginosa FADD1-PA001 (A) and P. aeruginosa JIP865 (B) before and after nebulisation using vibrating mesh nebulizer (n=5).

Figure 5.

Antibacterial activities of phage PEV20, ciprofloxacin and their combination against strains FADD1-PA001 (A) and JIP865 (B) before and after nebulization using air-jet nebulizer (n=5).

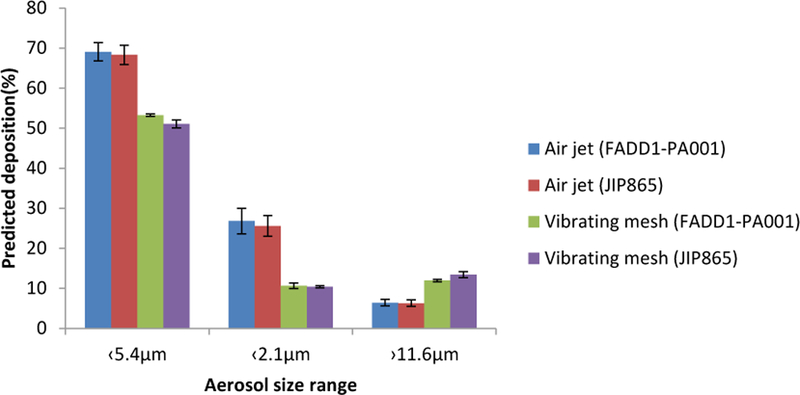

Particle size distribution of nebulized aerosols

The geometric particle size of aerosols generated by the two nebulizers are shown in Table 3. The Pari air-jet nebulizer generated smaller droplets (3.6–3.7µm) than eFlow vibrating mesh nebulizer (5.1–5.3µm). FPF were 68%−69% and 51%−53% for the air-jet and vibrating mesh nebulized aerosols, respectively (Figure 6).

Table 3.

Geometric particle size distributions of aerosols generated by the two nebulizers of phage-ciprofloxacin combinations (n=3)

| Nebulizers | Target strain | D10 (µm) | D50 (µm) | D90 (µm) | Span |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air-jet | FADD1-PA001 JIP865 |

1.25±0.16 1.26±0.13 |

3.62±0.22 3.72±0.21 |

9.82±0.45 9.80±0.45 |

2.37±0.07 2.29±0.05 |

| Vibrating mesh | FADD1-PA001 JIP865 |

2.09±0.06 2.11±0.02 |

5.12±0.03 5.31±0.09 |

12.68±0.04 13.51±0.55 |

2.07±0.02 2.14±0.07 |

Figure 6.

FPF of the nebulized phage-ciprofloxacin combinations using the Pari air-jet nebulizer and eFlow vibrating mesh nebulizer (n=3).

Discussion

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the most common pathogen isolated from airways in CF patients [27]. At present, some inhaled antibiotics are approved for the treatment of P. aeruginosa infection in the lungs of patients with CF[28] and patients with pneumonia in the intensive care unit[29]. As an alternative for treating MDR bacterial infections, inhaled phage delivery is under investigation with promising application prospects [19, 20, 22]. Combination use of phage and antibiotics is a logical and important choice as bacteria can develop resistance to both [8] . Both in vitro [12–16]and in vivo [17, 18] studies had demonstrated that phage when combined with antibiotics can produce synergistic antimicrobial effects [12–16][12–16][12–16][12–16][12–16][12–16][12–16][12–16][12–16][13–17]. However, the synergy of nebulized phage-antibiotic combinations suitable for inhalation therapy has not been addressed.

In our study, among the five FDA approved inhalable antibiotics, ciprofloxacin was found to have the maximal synergistic effect with PEV20 against two clinical P. aeruginosa strains FADD1-PA001 and JIP865, and this finding is consistent with recent work on other phage involving phage-antibiotic combination and P. aeruginosa[14, 17]. Another antibiotic candidate amikacin also showed synergy with PEV20 for two clinical strains, however, synergistic effect was less than ciprofloxacin for strain JIP865. Amikacin was reported to be synergistic with bacteriophages against P. aeruginosa biofilm [30] and planktonic cultures [31] as well. For colistin and tobramycin, synergy with PEV20 was observed on FADD1-PA001 and JIP865, respectively. However, bacterial growth was not completely inhibited. Although aztreonam did not show synergy with PEV20, additive effects were observed. Colistin or tobramycin with PEV20 also showed additive effect on JIP865 and FADD1-PA001, respectively. Previous research showed that colistin and tobramycin were synergistic with phage against P. aeruginosa [26, 32]. Aztreonam was reported to have synergy with phage against Escherichia coli [12]. The underlying molecular mechanisms for phage antibiotics synergy (PAS) are unclear. Chan et al [14] reported that it was much more difficult for bacteria to evolve resistance to both antibiotics and bacteriophage because of the evolutionary trade-off. Ciprofloxacin works by inhibiting DNA gyrase inside the bacteria, while phage PEV20 could change the activity of drug efflux pump and thereby increases intracellular concentrations of ciprofloxacin. Another study showed that sub-lethal concentrations of cefotaxime could also stimulate the production of phages inside bacterial cells[16]. Susceptibility of the three clinical isolates FADDI-PA001, JIP865 and 20833n/m(s) used in our study to phage PEV20 was high, medium and low, respectively. These strains were selected to represent the bacterial populations with different susceptibility to the phage. Hence, the MOIs of PEV20 each were set at 0.1, 100 and 1000. The bacterial growth kinetics study showed that higher susceptibility to PEV20 resulted in higher synergistic effect for different combinations against the bacteria. The combination of PEV20 and ciprofloxacin induced synergistic antimicrobial effect against the clinical strains FADD1-PA001 and JIP865 but not against 20844n/m(s), demonstrating dependence of the synergy on phage susceptibility.

Nebulization causes a loss in titre for phage [20]. As PEV20-ciprofloxacin combination was the most effective for strains FADD1-PA001 and JIP865, we chose these two strains to do a bacterial growth kinetics study after nebulization. For the two strains, we use two PEV20 and ciprofloxacin combinations and were able to demonstrate that synergy of phage PEV20 and ciprofloxacin was maintained after nebulisation. In vitro aerosol performance of phage PEV20-ciprofloxacin combinations delivered by the two nebulizers was characterized by particle size distribution and FPF. No significant difference was observed between the two combinations using the same nebulizer. The jet nebulizer generated smaller droplets than the vibrating mesh nebulizer, therefore resulting in higher FPF. The dead volume was less than 1 mL for both nebulizers. However, the aerodynamic particle size distribution and FPF are not sufficient to predict the regional pulmonary deposition of aerosols produced by nebulizers. The breath pattern[33] and differences in the geometry of the respiratory tract [34] are also important for deposition. A previous study used Pari LC star and eFlow nebulizers to deliver phages of Burkholderia cepacia complex in combination with a pulmonary waveform generator to simulate the breathing pattern of an adult. This indicated that the varying numbers of phages could be predicted to deposit in different regions of the lung predicted [35].

Dosing regimens for inhaled antibiotics are influenced by the pattern of drug-resistance of the target bacteria, the mechanism of action and aerosol performance of the drugs, as well as the release rate of formulation. To optimize dosing strategy, ratios of area under the curve (AUC) in plasma or epithelial lining fluid over MICs can be used in the modelling of PD/PK of inhalation antibiotics[36]. A single dose of dry powder ciprofloxacin (PulmoSphere™) approved for inhalation is 32.5 mg[4], while 100 mg of nebulized liposome ciprofloxacin has been used in clinical trials[37]. Higher concentrations could be used for liposome ciprofloxacin formulation owing to slow release rate. In our study, the maximum dose of used was 320 µg, which is far less than other formulations under development. However, PEV20-ciprofloxacin concentrations in suspension were based on MICs of different target strains in vitro. It is reasonable to use a lower dose for phage antibiotic combination compared with antibiotics alone if the MICs of combinations are also much lower. To determine the regimens for clinical dosing, pre-clinical PK/PD studies are necessary to determine the optimal dosing strategy

It is generally believed that phage are specific to bacteria thus cause no harm to human cells. Phage therapy utilizes obligatory lytic phages to kill bacterial host. New phages are produced during the lytic cycle of infection within bacterial cells and released from the host via cell lysis and the cycle restarts[38]. However, toxicity research is important for the clinical use .Safety of phage PEV20 dry powder had been evaluated in vitro and in vivo[23]. Cell survival rates of human epithelial (A549 and HEK239) and macrophage (THP-1) were not affected after 24h exposure to PEV20. In vivo safety evaluation also showed no toxicity in lung tissues of mice after pulmonary delivery of PEV20. For PEV20 and ciprofloxacin combination, future animal studies are needed to verify in vivo synergy and safety.

The use of ciprofloxacin for inhalation therapy has a risk of drug resistance, especially during long-term treatment [37]. Development of resistant bacteria to single phage is also inevitable. Based on this in vitro study, phage PEV20 in combination with ciprofloxacin suppresses the regrowth of clinical P. aeruginosa strains 24 h post-treatment. Inhalation delivery of synergistic phage-antibiotic combinations provides a realistic approach to address the pressing clinical problems of MDR bacteria.

Conclusion

The combination of phage PEV20 and ciprofloxacin showed the most synergistic antibacterial effect against the three P. aeruginosa clinical strains used in this study. Aerosols of these combinations generated with both the air-jet and vibrating mesh nebulizers were inhalable with maintenance of the bacterial killing synergy. Since the air-jet nebulizer generates aerosol particles with smaller diameters than the vibrating mesh nebulizer, it may be more suitable to nebulize phage-antibiotic combinations for the treatment of deeper infections in the respiratory tract. Phage-antibiotic combinations for inhalation can provide a promising means to combat antibiotic-resistant bacterial infection in the respiratory system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease of the National Institutes of Health under award number R33 AI121627 (H.-K.C and J.L).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allery and Infectious Diseases or the National Institute of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Breidenstein EB, de la Fuente-Nunez C, Hancock RE, Pseudomonas aeruginosa: all roads lead to resistance, Trends in microbiology, 19 (2011) 419–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ahlgren HG, Benedetti A, Landry JS, Bernier J, Matouk E, Radzioch D, Lands LC, Rousseau S, Nguyen D, Clinical outcomes associated with Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa airway infections in adult cystic fibrosis patients, BMC pulmonary medicine, 15 (2015) 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Martínez-Solano L, Macia MD, Fajardo A, Oliver A, Martinez JL, Chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Clinical Infectious Diseases, 47 (2008) 1526–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Velkov T, Rahim NA, Zhou QT, Chan H-K, Li J, Inhaled anti-infective chemotherapy for respiratory tract infections: successes, challenges and the road ahead, Advanced drug delivery reviews, 85 (2015) 65–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Abedon ST, Phage therapy of pulmonary infections, Bacteriophage, 5 (2015) e1020260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ryan EM, Gorman SP, Donnelly RF, Gilmore BF, Recent advances in bacteriophage therapy: how delivery routes, formulation, concentration and timing influence the success of phage therapy, Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 63 (2011) 1253–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hraiech S, Brégeon F, Rolain J-M, Bacteriophage-based therapy in cystic fibrosis-associated Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections: rationale and current status, Drug design, development and therapy, 9 (2015) 3653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Labrie SJ, Samson JE, Moineau S, Bacteriophage resistance mechanisms, Nature Reviews Microbiology, 8 (2010) 317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hyman P, Abedon ST, Bacteriophage host range and bacterial resistance, in: Advances in applied microbiology, Elsevier, 2010, pp. 217–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Buckling A, Rainey PB, Antagonistic coevolution between a bacterium and a bacteriophage, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 269 (2002) 931–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sorek R, Kunin V, Hugenholtz P, CRISPR—a widespread system that provides acquired resistance against phages in bacteria and archaea, Nature Reviews Microbiology, 6 (2008) 181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Comeau AM, Tétart F, Trojet SN, Prere M-F, Krisch H, Phage-antibiotic synergy (PAS): β-lactam and quinolone antibiotics stimulate virulent phage growth, PLoS One, 2 (2007) e799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Knezevic P, Curcin S, Aleksic V, Petrusic M, Vlaski L, Phage-antibiotic synergism: a possible approach to combatting Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Research in microbiology, 164 (2013) 55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chan BK, Sistrom M, Wertz JE, Kortright KE, Narayan D, Turner PE, Phage selection restores antibiotic sensitivity in MDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Scientific reports, 6 (2016) 26717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Torres-Barceló C, Hochberg ME, Evolutionary rationale for phages as complements of antibiotics, Trends in microbiology, 24 (2016) 249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ryan EM, Alkawareek MY, Donnelly RF, Gilmore BF, Synergistic phage‐ antibiotic combinations for the control of Escherichia coli biofilms in vitro, Pathogens and Disease, 65 (2012) 395–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Oechslin F, Piccardi P, Mancini S, Gabard J, Moreillon P, Entenza JM, Resch G, Que YA, Synergistic Interaction Between Phage Therapy and Antibiotics Clears Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Infection in Endocarditis and Reduces Virulence, J Infect Dis, 215 (2017) 703–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kamal F, Dennis JJ, Burkholderia cepacia complex Phage-Antibiotic Synergy (PAS): antibiotics stimulate lytic phage activity, Applied and environmental microbiology, 81 (2015) 1132–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Carrigy NB, Chang RY, Leung SS, Harrison M, Petrova Z, Pope WH, Hatfull GF, Britton WJ, Chan H-K, Sauvageau D, Anti-Tuberculosis Bacteriophage D29 Delivery with a Vibrating Mesh Nebulizer, Jet Nebulizer, and Soft Mist Inhaler, Pharmaceutical research, 34 (2017) 2084–2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Astudillo A, Shui Yee Leung S, Kutter E, Morales S, Chan HK, Nebulization effects on structural stability of bacteriophage PEV 44, Eur J Pharm Biopharm, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- [21].Kendrick A, Smith E, Wilson R, Selecting and using nebuliser equipment, Thorax, 52 (1997) S92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chang RY, Wong J, Mathai A, Morales S, Kutter E, Britton W, Li J, Chan HK, Production of highly stable spray dried phage formulations for treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection, European journal of pharmaceutics and biopharmaceutics : official journal of Arbeitsgemeinschaft fur Pharmazeutische Verfahrenstechnik e.V, 121 (2017) 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Chang RYK, Chen K, Wang J, Wallin M, Britton W, Morales S, Kutter E, Li J, Chan H-K, Proof-of-Principle Study in a Murine Lung Infection Model of Antipseudomonal Activity of Phage PEV20 in a Dry-Powder Formulation, Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 62 (2018) e01714–01717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chang RYK, Chen K, Wang J, Wallin M, Britton W, Morales S, Kutter E, Li J, Chan H-K, Anti-Pseudomonal activity of phage PEV20 in a dry powder formulation—A proof-of-principle study in a murine lung infection model, Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, (2017) AAC. 01714–01717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [25].Wiegand I, Hilpert K, Hancock RE, Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances, Nature protocols, 3 (2008) 163–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chaudhry WN, Concepción-Acevedo J, Park T, Andleeb S, Bull JJ, Levin BR, Synergy and order effects of antibiotics and phages in killing Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms, PloS one, 12 (2017) e0168615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lucca F, Guarnieri M, Ros M, Muffato G, Rigoli R, Da Dalt L, Antibiotic resistance evolution of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis patients (2010ȓ2013), The clinical respiratory journal, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- [28].Newman SP, Delivering drugs to the lungs: The history of repurposing in the treatment of respiratory diseases, Advanced drug delivery reviews, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- [29].Alves J, Alp E, Koulenti D, Zhang Z, Ehrmann S, Blot S, Bassetti M, Conway-Morris A, Reina R, Teran E, Nebulization of antimicrobial agents in mechanically ventilated adults in 2017: an international cross-sectional survey, European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases, (2018) 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [30].Nouraldin AAM, Baddour MM, Harfoush RAH, Essa SAM, Bacteriophage-antibiotic synergism to control planktonic and biofilm producing clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Alexandria Journal of Medicine, 52 (2016) 99–105. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Uchiyama J, Shigehisa R, Nasukawa T, Mizukami K, Takemura-Uchiyama I, Ujihara T, Murakami H, Imanishi I, Nishifuji K, Sakaguchi M, Piperacillin and ceftazidime produce the strongest synergistic phage–antibiotic effect in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Archives of virology, (2018) 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [32].Danis-Wlodarczyk K, Vandenheuvel D, Jang HB, Briers Y, Olszak T, Arabski M, Wasik S, Drabik M, Higgins G, Tyrrell J, A proposed integrated approach for the preclinical evaluation of phage therapy in Pseudomonas infections, Scientific reports, 6 (2016) 28115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bauer A, McGlynn P, Bovet LL, Mims PL, Curry LA, Hanrahan JP, The influence of breathing pattern during nebulization on the delivery of arformoterol using a breath simulator, Respiratory care, 54 (2009) 1488–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Yang MY, Ruzycki C, Verschuer J, Katsifis A, Eberl S, Wong K, Golshahi L, Brannan JD, Finlay WH, Chan H-K, Examining the ability of empirical correlations to predict subject specific in vivo extrathoracic aerosol deposition during tidal breathing, Aerosol Science and Technology, 51 (2017) 363376 [Google Scholar]

- [35].Golshahi L, Seed KD, Dennis JJ, Finlay WH, Toward modern inhalational bacteriophage therapy: nebulization of bacteriophages of Burkholderia cepacia complex, Journal of aerosol medicine and pulmonary drug delivery, 21 (2008) 351–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lin Y-W, Zhou QT, Han M-L, Onufrak NJ, Chen K, Wang J, Forrest A, Chan H-K, Li J, Mechanism-Based Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Modeling of Aerosolized Colistin in a Mouse Lung Infection Model, Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 62 (2018) e01965–01917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Cartlidge MK, Hill AT, Inhaled or nebulised ciprofloxacin for the maintenance treatment of bronchiectasis, Expert opinion on investigational drugs, 26 (2017) 1091–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Chang RYK, Wallin M, Lin Y, Leung SSY, Wang H, Morales S, Chan H-K, Phage therapy for respiratory infections, Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.