Abstract

To date, a large number of mutations in SCN5A, the gene encoding the pore-forming α-subunit of the primary cardiac Na+ channel (NaV1.5), have been found in patients presenting with a wide range of ECG abnormalities and cardiac syndromes. Although these mutations all affect the same NaV1.5 channel, the associated cardiac syndromes each display distinct phenotypical and biophysical characteristics. Variable disease expressivity has also been reported, where one particular mutation in SCN5A may lead to either one particular symptom, a range of various clinical signs, or no symptoms at all, even within one single family. Additionally, disease severity may vary considerably between patients carrying the same mutation. The exact reasons are unknown, but evidence is increasing that various cardiac and non-cardiac conditions can influence the expressivity and severity of inherited SCN5A channelopathies. In this review, we provide a summary of identified disease entities caused by SCN5A mutations, and give an overview of co-morbidities and other (non)-genetic factors which may modify SCN5A channelopathies. A comprehensive knowledge of these modulatory factors is not only essential for a complete understanding of the diverse clinical phenotypes associated with SCN5A mutations, but also for successful development of effective risk stratification and (alternative) treatment paradigms.

Keywords: NaV1.5, LQT3, Brugada syndrome, conduction, co-morbidities

Introduction

To date, an increasing number of mutations in SCN5A, the gene encoding the pore-forming α-subunit of the primary cardiac Na+ channel (NaV1.5), is found in patients with a wide range of electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities and cardiac syndromes (1–3). Although they are all due to mutations in the same ion channel, these syndromes show a myriad of phenotypes (4). While this may be partly explained by mutation-specific biophysical changes in the current generated by NaV1.5 channels (here named Na+ current, INa), it has now become clear that a single mutation in SCN5A may also result in a large number of disease phenotypes within one and the same family [for review, see (2)]. Also, disease severity often varies significantly among affected individuals, with some SCN5A mutation-positive patients suffering from life-threatening arrhythmias at young age while others do not display any clinical signs (i.e., reduced and incomplete penetrance).

At this moment, clinical management of SCN5A mutation-positive patients is hindered by this reduced penetrance as well as by the considerable variation in disease severity and risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) observed in affected individuals. Cardiac and non-cardiac modulatory factors and co-morbidities are supposed to modify disease severity and expressivity, however, till now they are largely unexplored. A major reason for the lack of detailed information on such disease modifiers in SCN5A-mutation related disorders is the large genetic heterogeneity between individual patients. In addition, different mutations result in different biophysical alterations and thus give rise to further variability between individuals. In this review, we provide an updated summary of presently identified cardiac disease entities secondary to SCN5A mutations, and give an overview of a broad spectrum of concomitant disorders and conditions which may modify disease severity and expressivity of SCN5A channelopathies.

Cardiac disorders associated with SCN5A mutations

NaV1.5 channels are widely distributed in the mammalian heart, but the number of channels (5–7) and their electrophysiological function (6, 8–10) may differ between various parts of the heart. Consequently, SCN5A mutations can lead to multiple cardiac disease phenotypes, and even considerable overlap may exist, named “overlap syndrome,” between these cardiac clinical entities (2). Aside from the heart, NaV1.5 channels are also expressed in other tissues throughout the body, and SCN5A mutations therefore are also associated with extracardiac phenotypes, including gastrointestinal dysfunction (11) and epilepsy (12). Below, we first provide a brief overview of the NaV1.5 channel and INa properties and subsequently introduce briefly the various SCN5A-related cardiac disorders in relation to the associated biophysical NaV1.5 channel defects.

NaV1.5 structure and function

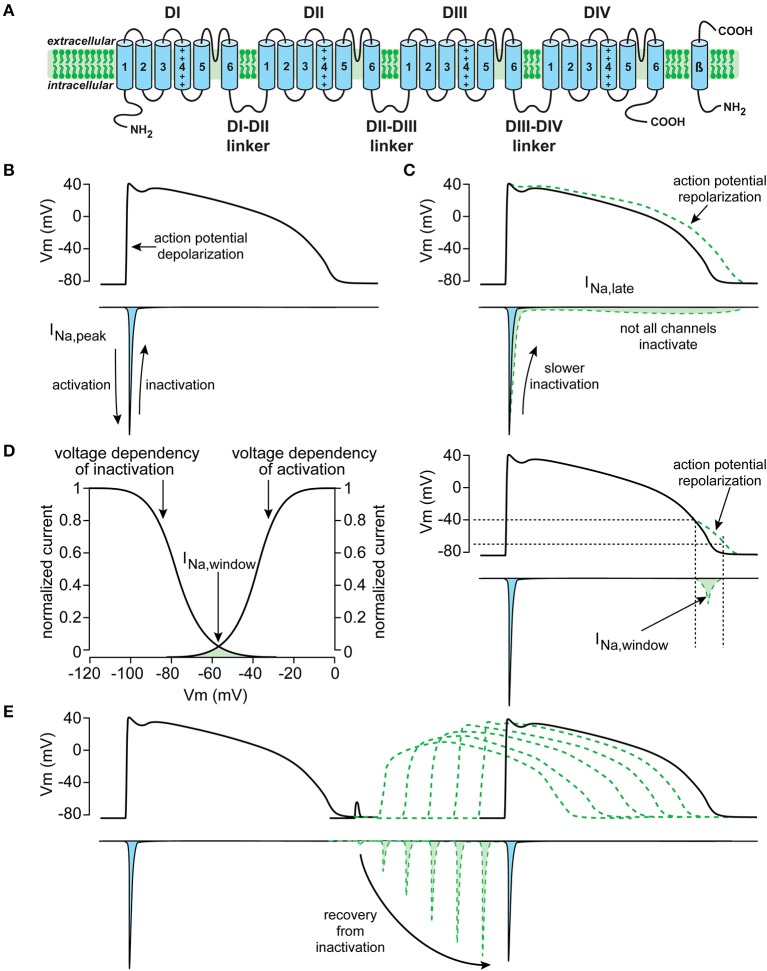

As reviewed in detail elsewhere (13), the NaV1.5 protein is formed by four homologous domains (D1–DIV) each composed of six transmembrane spanning helices (S1–S6) (Figure 1). NaV1.5-based channels are voltage dependent and open upon depolarization, resulting in a rapid activation of INa. In working myocytes, this INa is large and generates the fast action potential (AP) depolarization (6, 14). Typically, NaV1.5 channels also close rapidly due to inactivation. This fast inactivation, together with the reduction in driving force of Na+ ions occurring during the AP upstroke, results in a rapid decrease of INa (Figure 1B). Although most NaV1.5 channels show fast inactivation, some channels may inactivate slower and/or incompletely. Consequently, a small persistent or late INa current is generated (Figure 1C), which may affect AP repolarization (15). Moreover, a small overlap exists between the voltage dependence of activation and inactivation. Therefore, NaV1.5 channels can activate but are not inactivated completely, resulting in a small INa at this range of membrane potentials, named the “window current” (Figure 1D). Such a window current also contributes to the AP repolarization phase. In addition, late and/or window INa may also affect pacemaker activity of sinoatrial nodal (SAN) cells (8, 10) and excitability (16). Upon return to hyperpolarized potentials, i.e., during or following the AP repolarization, NaV1.5 channels can quickly recover from inactivation (14). The speed of recovery from inactivation regulates NaV1.5 channel availability for subsequent APs, and is therefore responsible for the refractory period (17).

Figure 1.

Schematic drawings of the cardiac sodium channel NaV1.5 encoded by the SCN5A gene (A), and important biophysiological properties and function of the current generated by SCN5A (here named INa), including peak INa (B), late INa (C), window INa (D), and recovery from inactivation (E).

SCN5A-related disorders

Brugada syndrome (BrS) is characterized on the ECG by ST-segment elevation in the right-precordial leads V1 to V3. BrS is associated with ventricular arrhythmias and SCD, which occur particularly during rest and sleep in apparently healthy and young (age < 40 years) individuals (18). The characteristic ST-segment elevation of the ECG is often variably present, and can be unmasked by INa blockade or exercise [see (18)]. SCN5A mutations linked to BrS are so called “loss-of-function” mutations, which typically result in a decreased INa (1). This reduction in INa may be due to decreased trafficking and membrane channel expression and/or altered gating properties of the channel resulting in disruption of voltage dependency of (in)activation, accelerated speed of inactivation, or slowed recovery from inactivation.

Long QT syndrome (LQTS) is characterized by a QT-interval prolongation on the ECG accompanied by an enhanced risk for SCD as a result of ventricular tachyarrhythmias. LQTS type 3 (LQT3), the subtype caused by SCN5A mutations, is associated with bradycardia and arrhythmias and/or SCD occurring mostly at slow heart rates such as during rest or sleep (19). SCN5A mutations underlying LQT3 are typically “gain-of-function” mutations inducing various biophysical alterations (such as slower INa inactivation, larger late INa, larger window INa, and/or increased INa density (1), all leading to an enhanced INa function during the AP repolarization phase and consequent AP prolongation.

Atrial fibrillation (AF), a rapid and irregular beating of the atria, is mostly found in elderly patients with structural alterations in the heart. Evidence is increasing that AF in young patients with structurally normal hearts may also be hereditary. In familial forms of AF, both SCN5A loss-of-function and gain-of-function mutations have been identified (20). The gain-of-function can be due to various gating changes including negative shifts in voltage dependence of activation, positive shifts in voltage dependence of inactivation, slower current inactivation, and faster recovery from inactivation [see (16), and primary references cited therein]. Loss-of-function can be the consequence of reduced INa density (21) or of a negative shift in voltage dependence of inactivation (22).

Sick sinus syndrome (SSS) is described as the “intrinsic inadequacy of the SAN to perform its pacemaking function due to a disorder of automaticity and/or inability to transmit its impulse to the rest of the atrium” [see (23)]. A number of SCN5A mutations have been associated with inherited SSS, and interestingly these can be both loss-of-function and gain-of-function mutations. Consequently, the occurrence of SSS has a considerable overlap with BrS (24) and LQT3 (25, 26). Loss-of-function, i.e., a reduction of INa availability, decreases the speed of the diastolic depolarization phase of SAN cells and thereby pacemaker activity (25). The overlap of SSS and gain-of-function mutations associated with LQT3 is more complex. Although an increase in late INa results in faster pacemaker activity (25), the concurrent changes in INa density and the shifts in voltage dependency of activation and inactivation counteract the enhanced late INa, resulting in a slower pacemaker activity (25).

Progressive cardiac conduction defect (PCCD) is characterized by progressive conduction slowing through the His-Purkinje system. PCCD is associated with PQ- and QRS-interval prolongation, complete atrio-ventricular (AV) and right and/or left bundle branch block, syncope and SCD. PCCD is often observed in BrS patients, and similar to BrS, is due to loss-of-function mutations (18).

Multifocal ectopic Purkinje-related premature contraction (MEPPC) is characterized by frequent premature ventricular contractions originating from the Purkinje system, especially at rest (16). The SCN5A mutations underlying MEPPC are typically gain-of-function mutations due to an increased window INa, faster recovery from inactivation and/or increased channel availability of NaV1.5 (see (16), and primary references cited therein).

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) is characterized by the sudden unexplained death of a seemingly healthy infant younger than 1 year. SIDS is a disease with multiple pathophysiological mechanisms (27), and cardiac ion channel gene mutations appear to be involved in approximately 20% of the cases of SIDS, from which more than half of the mutations are related to INa [for review, see (28)]. These may include mutations in SCN5A, but also in the INa-modulatory β-subunits (SCN3B and SCN4B) and other “regulatory genes” (CAV3, SNTA1, and GPD1-L), which could result in either INa loss-of function or gain-of-function mutations [see (28, 29), and primary references cited therein].

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a structural heart disease characterized by dilated chambers, pump failure, and arrhythmia. DCM is a multifactorial disorder with several proposed pathophysiological mechanisms (30), including SCN5A mutations (31). Both loss-of-function and gain-of-function are associated with DCM, but the pathophysiological mechanisms of DCM secondary to SCN5A mutations are not exactly known (2, 32). As reviewed by Wilde and co-workers, DCM may be: (i) secondary to SCN5A mutation induced arrhythmias and/or bradycardia; (ii) due to increased late INa and consequent changes in intracellular Na+ and Ca2+; or (iii) secondary to the non-electrical role of NaV1.5 as a potential anchoring protein for structural and cytoskeletal proteins (33).

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) is an inherited cardiomyopathy characterized by fibrofatty replacement of the right ventricle, ventricular arrhythmias, and SCD (34). Up to 60–70% of the ARVC index cases carry a causal desmosomal [such as plakophilin-2 (PKP2) or desmoglein-2 (DSG2)] gene mutation, but various non-desmosomal genes may also be involved (35, 36), including SCN5A (37). Although the percentage of pathogenic SCN5A mutations in ARVC is very low, PKP2 knockdown and overexpression of Dsg2 mutations both result in a decrease in INa (38, 39), and such a decrease in INa is proposed to be a critical factor in arrhythmogenesis in ARVC (40).

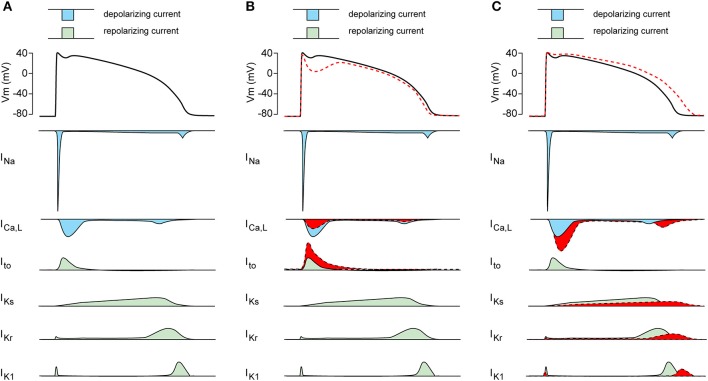

Variable expressivity in SCN5A channelopathy

Patients harboring SCN5A mutations demonstrate a significant variability in disease expression (41). Obviously, such variability in SCN5A-releated diseases can be due to different severities of the INa biophysical defect, with truncating SCN5A loss-of-function mutations resulting in more pronounced conduction slowing than missense SCN5A mutations (42). The range of biophysical alterations induced by a particular genetic defect in SCN5A (1) may also determine the capability of that mutation to cause cardiac rhythm disorders. Importantly, the variability in SCN5A-releated disease severity and expressivity is also present in family members carrying the same mutation, as exemplified in a large Dutch family with the SCN5A-1795insD “overlap syndrome” mutation (43). Some mutation carriers in this family display predominantly loss-of-function phenotypes with BrS and/or conduction disease, while other family members carrying this mutation show mainly a gain-of-function phenotype resulting in QT-prolongation (44). In addition, and apart from family members with a clear phenotype, other family members carrying the same SCN5A-1795insD mutation appear unaffected (43). Thus, independent of the mutation-specific effects, individual-specific factors also appear to contribute importantly to the regulation of disease expressivity and severity in SCN5A channelopathy. Moreover, the variability in NaV1.5 disease expression and severity is not only related to INa defects, but likely also closely related to other cardiac ion channels which contribute to the cardiac AP. Apart from INa, the AP morphology is the consequence of a fine balance between the inwardly directed L-type Ca2+ current (ICa,L; CaV), and various outwardly directed K+ currents (KV) including the transient outward K+ current (Ito), the inward rectifier K+ current (IK1) and the slow and rapid delayed rectifier K+ currents (IKs and IKr, respectively) (Figure 2A). Changes in these CaV and various KV currents may affect the expressivity of SCN5A channelopathies. For example, a decrease in ICa,L and/or increase Ito (Figure 2B, in red) may increase phase-1 repolarization and lower the AP plateau phase which may promote ST-segment elevation and BrS (45), while an increase in ICa,L and/or decrease of KV currents (Figure 2C, in red) will result in longer APs thus promoting LQT3 (46).

Figure 2.

(A) Schematic drawing of the cardiac action potential (AP) and its underlying membrane currents. INa, Na+ current; ICa,L, L-type Ca2+ current; Ito, transient outward K+ current; IKs, slow component of the delayed rectifier K+ current; IKr, rapid component of the delayed rectifier K+ current; IK1, inward rectifier K+ current. (B) Schematic drawing of AP plateau suppressing ion channels changes (in red). (C) Schematic drawing of AP prolonging ion channels changes (in red).

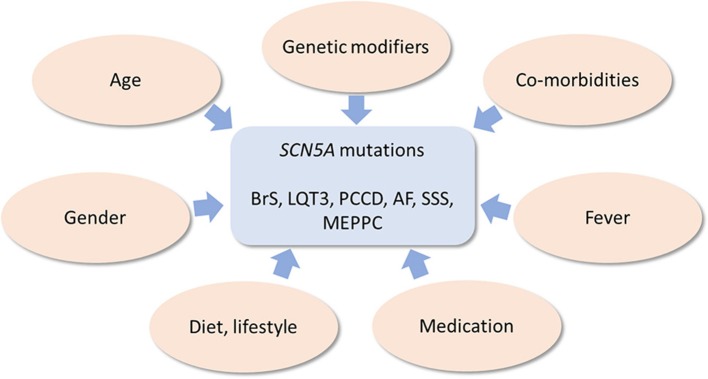

Below, we provide an overview of various known genetic and non-genetic disease modifiers of inherited cardiac SCN5A channelopathies, which are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic drawing of genetic and non-genetic disease modifiers of inherited cardiac SCN5A channelopathies.

Genetic modifiers of SCN5A channelopathy

Genetic background and modifiers are considered important determinants of disease expressivity and/or severity in SCN5A channelopathies, especially among patients carrying the same mutation (47–49). This has been clearly demonstrated in experimental studies where the impact on genetic variability on disease severity was evaluated in two distinct strains (129P2 and FVBN/J background) of mice carrying the Scn5a-1798insD/+ mutation, the equivalent to SCN5A-1795insD in humans. A more severe phenotype was present in 129P2 mice as compared to FVBN/J mice (50, 51). In addition, subsequently identified potential modifiers of conduction disease severity were found. Comparison of cardiac gene expression between the 129P2 mice and FVBN/J mice demonstrated that Scn4b (encoding a ß-subunit of sodium channels) is an important modifier of conduction disease severity (52). Furthermore, by performing a system genetics approach on F2 progeny arising from these two mouse strains, we showed that Tnni3k (encoding troponin 1 interacting kinase) is another modulator of AV conduction (53). These genetic studies clearly underline the relevance of genetic background and genetic modifiers in sodium channelopathy.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms, frequently observed in the general population, may further determine disease expressivity and/or severity. For example, H558R is the most commonly found SCN5A polymorphism (with a 9–36% prevalence), and its distribution varies between different ethnic populations (54). Co-existence of this polymorphism and SCN5A mutations may affect the functional consequences of the latter, including plasma-membrane targeting of NaV1.5, INa density and/or INa gating properties (55–60). Moreover, a combination of specific polymorphisms [haplotype (HapB)] within the SCN5A promoter region may affect conduction in BrS patients (61). HapB is frequently present in Asians, and may therefore partly explain the high prevalence of BrS in individual with an Asian background. In addition, polymorphisms in non-SCN5A genes may also contribute to disease expressivity in sodium channelopathy. For example, Groenewegen et al. (62) demonstrated that phenotype severity of SCN5A-D1275N mutation carriers was importantly modulated by 2 closely linked polymorphisms forming a haplotype within the promotor region of the GJA5, the gene underlying the atrial-specific connexin-40 gap junction protein. SCN5A-D1275N mutation carriers homozygous for the GJA5 promoter polymorphisms exhibited atrial standstill, while carriers without or with only a heterozygous GJA5 promoter polymorphism displayed only a mild PR-interval prolongation (62).

Additionally, genetic variation due to the presence and relative expression of two important SCN5A alternatively spliced variants, i.e., SCN5A-Q1077del and SCN5A-Q1077 (63), may further modulate sodium channelopathy severity. The BrS phenotype severity associated with the SCN5A-G1406R mutation was enhanced in combination with the Q1077 variant (64). Q1077del has furthermore been shown to modulate INa density, gating properties, and recovery from inactivation of SCN5A mutations associated with DCM (65).

Non-genetic modifiers of SCN5A channelopathy

Gender

Gender is a clear modifier of disease severity in SCN5A channelopathy, exemplified by the preponderance of BrS in males (66), and LQT3 in females especially in the 30–40 year age range (67). In addition, within one family with the G1406R loss-of-function mutation, females were found to have mostly cardiac conduction defects whereas males showed predominantly a BrS phenotype (47). Gender, and particularly sex hormones, has a significant impact on ion channels responsible for repolarization, and is associated with a larger ICa,L and smaller Ito and consequently higher QTc values in females [see (68), and primary references cited therein]. This lower repolarization reserve intrinsic to female hearts is thought to augment the detrimental impact of a mutation-induced late INa. Barajas-Martinez and colleagues reported a higher INa magnitude in male epi- and endocardial myocytes compared to female (69). In addition, they found in females a larger ventricular transmural dispersion of INa density. They suggested that in the setting of decreased INa, epicardial myocytes display more easily all-or-none repolarization leading to BrS in males (with a smaller ICa,L and larger Ito), while females with a smaller INa are more sensitive to loss of conduction velocity.

Age

Age is another determinant of severity and expressivity of SCN5A channelopathies (70–72). For example, carriers of the SCN5A-1795insD mutation show QT-interval prolongation and conduction disorders from birth, while features of BrS mostly develop later in life (72). While peak INa density and INa availability (i.e., AP upstroke velocity) does not appear to change with age (73, 74), aging may result in an acceleration of INa inactivation and an enhanced use-dependent decrease in INa (73). In addition, aging myocytes also show AP prolongation secondary to both an increase in late INa and a reduction in KV currents (74). These ion channel changes, together with a prolonged AP (74) (hence, a shorter time for recovery from inactivation) may promote BrS, conduction delay, and LQT3. Furthermore, fibrosis due to aging is thought to play another major role in modulating conduction and repolarization disorder severity (75–77).

Medication

It is well known that many clinically used antiarrhythmic, psychotropic, and anesthetics drugs may induce type-1 ECG and/or arrhythmias in BrS patients (78, 79). These drugs with potential adverse effects for BrS patients (for overview, see the website www.brugadadrugs.org) are known to block INa and/or CaV currents significantly, thereby increasing the susceptibility for BrS. In addition, many clinically used drugs are also known to result in QT-interval prolongation (71, 80). For an overview of QT-interval prolonging drugs, see the website www.QTdrugs.org. These drugs prolong the QT-interval due to blockade of IKr or IKs, rather than an increase of late INa, and increase the arrhythmia risk in patients with inherited LQTS, including LQT3 (81).

Lifestyle

Evidence is increasing that lifestyle can have a significant impact on SCN5A channelopathies by either a direct modulation of INa properties or indirectly via impacting on KV and CaV channels, making the heart more sensitive to (the consequences of) SCN5A mutations.

Alcohol

Alcohol consumption has been associated with BrS (82). Alcohol intoxication may have pro-arrhythmic actions through INa channel inhibition, thereby mimicking the actions of INa blocking drugs (83, 84). Furthermore, ethanol shortens the AP through multiple effects on CaV and KV channels [see (84), and primary references cited therein]; hence, alcohol could theoretically reduce QT-interval prolongation and arrhythmias in the setting of LQT3. On the other hand, episodic excessive alcohol intake is associated with an increase in QT duration dispersion due to cardiac autonomic imbalance (85), which may in fact promote repolarization abnormalities.

Recreational drug use

Recreational drug use is another well-known factor in BrS, especially cocaine (79). Cocaine has multiple indirect and direct effects on the electrical activity of the heart as demonstrated by increases in PR-, QRS-, and QT-intervals due to inhibition of CaV, KV and NaV currents (86). The decrease in INa appears to be caused by slower recovery from inactivation in combination with a shift in voltage dependency of inactivation (86). The cocaine-induced QT-prolongation is importantly due to a blockade of IKr, and predisposes to the occurrence of EADs and TdP (86).

Tobacco

Tobacco use has many detrimental effects on general health. In addition, nicotine and carbon monoxide (CO), a major component of smoke, also cause changes in cardiac development as well as ion channel remodeling (87, 88). For example, a low plasma concentration of nicotine increased peak INa and late INa, with shifts in both inactivation and activation kinetics resulting also in a larger INa window current (88). In addition, sublethal CO exposure is frequently associated with cardiac arrhythmias, and it has been demonstrated that its effects may be due to NaV1.5 channel modulation, causing an increase in late INa, but a decrease of peak INa (89).

Exercise

Exercise, especially swimming, may trigger most types of LQTS (90), but paradoxically appears to lower arrhythmia risk in LQT3 patients (91). On the other hand, exercise may aggravate the ECG defects observed in BrS patients (92). These acute effects of exercise on BrS and LQT3 may be explained by vagal activity and rapid heart rates, resulting in less recovery from inactivation in combination of a lower driving force of Na+ ions due to intracellular Na+ accumulation (91–93). Regular low intensity exercise and endurance training can also lead to structural and electrical remodeling of the heart [for review, see (92)]. A well-known effect of exercise training is a reduction of resting heart rate, partially via a decrease of the hyperpolarization-activated current, If (94). Theoretically, such a lower resting heart rate may itself increase the susceptibility to both BrS and LQT3. On the other hand, exercise training does not affect the expression of SCN5A mRNA (95), but reduces Ito in epicardial myocytes thereby reducing the transmural gradient of Ito significantly (96). This could potentially suppress BrS, but may increase LQT3 due to AP prolongation (96).

Diet and dietary supplements

Diet may have both beneficial and detrimental effects on SCN5A-related diseases, but underlying mechanisms appear complex. For example, acute application of polyunsaturated fatty acids, in particular those of the n-3 class (PUFAs), inhibits INa (97) and therefore may facilitate BrS. Yagi et al. (98), however, suggested that n-3 PUFAs may prevent ventricular fibrillation in BrS, likely due to additional blockade of various other cardiac ion channels (68), including Ito (99). High cholesterol and fat intake may constitute additional diet-related modulatory factors. Both are associated with a slower recovery from INa inactivation, but with a more negative voltage dependence of INa activation, which may lower the threshold for excitation of NaV1.5 channels (100). To date, the clinical impact of high cholesterol and fat intake on LQT3 and BrS patients are as yet unknown. Interestingly, consuming a large meal, resulting in vagal stimulation, may trigger sudden cardiac arrest in BrS (101, 102). In addition, glucose load (alone and in combination with insulin infusion), as well as Thai high glycemic index (HGI) meals are known to affect ST-segment elevation in BrS patients (see (103), and primary references cited therein). The mechanism behind this effect may be related to glucose-induced insulin secretion. In myocytes, insulin results in activation of the Na/K pump (104), and consequently, in an increased outwardly directed current during the AP thereby theoretically promoting repolarization. On the other hand, insulin in myocytes enhanced the depolarizing ICa,L (105), while it inhibits IKr (106) and IKs (107), thereby prolonging the QTc in humans (108) which may favor LQTS. More studies are required to elucidate the exact role of glucose/insulin on BrS and LQT3, and to explain the so-called diabetic death-in-bed syndrome as mentioned by Skinner et al. (109). Furthermore, high salt and glucose intake can result in hypertension and diabetes, respectively. Both diseases have significant impact on ion channel function, and hence likely also modulate disease expressivity and severity in the setting of SCN5A mutations (see also below).

These days, dietary supplements, natural drugs, and/or traditional Chinese medicines are increasingly used (110). Some ingredients in these preparations shorten the cardiac AP due to INa and ICa,L inhibition [for review, see (110)], thus caution for BrS patients seems appropriate. Other compounds, such as Wenxin Granule [for review, see (111)], may however have a therapeutic effect on BrS. Although Wenxin Granule was shown to reduce INa, it also suppressed the electrocardiographic and arrhythmic manifestations of BrS due to inhibition of Ito (112). It has also been shown to reduce late INa (113, 114), and therefore may also have an impact in LQT3 patients. Resveratrol, a polyphenol compound that is primarily derived from grapes, also inhibits late INa as well as ICa,L (110); hence, LQT3 patients may have some benefit from such natural and readily available supplements. Another example of a traditional Chinese medicine is dimethyl lithospermate B (dmLSB), an extract of Chinese herbal Danshen. dmLSB slows INa inactivation, thereby potentially eliminating the arrhythmogenic substrate responsible for BrS (115). Other ingredients of natural drugs and/or traditional Chinese medicines are known to prolong the AP due to KV blockade which may consequently predispose to arrhythmias in LQT3 patients [for review, see (110)]. Finally, apart from direct action om membrane currents, diet and dietary supplements may lead to electrolyte changes, which may have an indirect impact on ion channel function and thereby modify disease expression. For example, higher K+ levels may shorten the QT-interval in LQT3 patients while hypokalemia is a well-known trigger of QT-interval prolongation and arrhythmias in patients with LQTS (116). Thus, diet and dietary supplements may impact on various SCN5A- related conditions, but randomized clinical trials are required to assess their potential beneficial and/or detrimental effects in SCN5A channelopathy patients.

Environmental conditions

Environmental conditions should also be considered as potential disease modifiers in SCN5A channelopathies. Particulate air pollution, for example, has been associated with increased QTc duration (117), and thus may theoretically increase disease severity in LQT3. In addition, sudden noises are well-known to trigger SCN5A-related arrhythmias (1), but evidence is increasing that more chronic, environmental noise pollution also increased incidence of arrhythmias, especially AF (118). The exact mechanism is yet unknown, but noise is a non-specific stressor that activates the autonomous nervous system and endocrine signaling with multiple effects on human health [for review, see (119)].

Fever

Some SCN5A mutations may induce BrS-associated symptoms especially during fever episodes, with may be due to changes in INa channel gating properties in response to increasing temperature (120, 121). We and others have shown that specific SCN5A mutations promote slow inactivation of INa at higher temperatures (i.e., enhanced slow inactivation), thereby causing reduced peak INa availability (122, 123). To date, specific LQT3-associated SCN5A mutations which display enhanced temperature sensitivities have not been described (121). In general, increased temperature does not affect the ratio between late and peak INa (124), but enhances the transmural repolarization dispersion thus facilitating the occurrence of torsade de pointes (TdP) during LQTS (125). While these observations suggest an increased sensitivity for LQT3 during fever, evidence for this is as yet lacking.

Diabetes

Patients with diabetes are more vulnerable for the development of arrhythmias, independent of other risk factors like hypertension and atherosclerosis (126). QT-interval prolongation is more often observed in diabetic patients as compared to non-diabetic individuals (127). QT prolongation, due to downregulation of KV4 channels, is also observed in rat and mouse models of diabetes (126, 128). Interestingly, diabetic mice also show an enhanced late INa (126). It is therefore plausible that diabetes increases disease severity in LQT3 patients, but evidence for such a modulatory effect is currently lacking. On the other hand, a decrease in NaV1.5 expression and INa has been reported in rabbit and rat models of diabetes (129, 130), which may have important implications for BrS.

Obesity

Obesity, marked by excessive fat accumulation and weight gain, may result in various chronic disorders such as dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, hypertension, hyperglycemia, and type 2 diabetes (131). Thus, it has multiple similarities with a number of other topics discussed in this review. Therefore, it is not unexpected that obesity can lead to various cardiac electrical disorders including AF, (supra)ventricular arrhythmias (128, 132), and LQTS (133). At this moment, it is not known whether obesity impacts on disease expressivity and/or severity in SCN5A-related channelopathies. However, given its QT-prolonging effect through an increase in ICa,L and a decrease of various KV channels (132), it is conceivable that obesity may exacerbate LQT3-associated features. Direct effects of obesity on peak and late INa have only been investigated in limited fashion, with contrasting results (for review, see (132), and primary references cited therein). Nevertheless, since the number of obese individuals is steadily rising, further studies are essential to elucidate potential obesity-related ion channel remodeling and consequences for arrhythmogenesis in the setting of ion channelopathies.

Hypertension

Hypertension may lead to progressive myocardial remodeling, ultimately resulting in the development of cardiac hypertrophy and associated electrical, homeostatic and structural alterations (134). The latter may act synergistically with biophysical alterations secondary to a SCN5A mutation resulting in an enhanced pro-arrhythmogenic substrate (135). Due to its progressive nature, the impact of hypertension-induced pro-arrhythmic remodeling is expected to increase with age. Indeed, we have recently demonstrated that co-existing hypertension increased arrhythmia risk and reduced the efficacy of pacemaker treatment in carriers of the SCN5A-1795insD mutation above the age of 40 years. Enhanced late INa, a known consequence of hypertrophy, was shown to be at least partly involved and may constitute a promising therapeutic strategy by additionally preventing intracellular sodium/calcium dysregulation (51, 136, 137). Other studies have shown a similar interaction between hypertension and disease severity and outcome, for example in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (138). Hence, careful monitoring of hypertension and hypertrophy in addition to aggressive anti-hypertensive treatment should be considered in SCN5A mutation carriers.

Coronary artery disease

Coronary artery disease may enhance the risk for cardiac events in BrS and LQTS patients. Co-existence of BrS and coronary spasm has been observed in Japanese patients (139–142), but not in European patients (143). The relation to SCN5A mutations were not mentioned in these studies, but van Hoorn and colleagues found that the prevalence of coronary artery disease was significantly higher among BrS patients with SCN5A mutations than among BrS patients without SCN5A mutations (144). Interestingly, Kujime and coworkers reported that coronary artery vasospasm could be a risk factor for cardiac events in patients with BrS (145). Coronary artery disease was reported to augment the risk for LQTS-related cardiac events in LQTS patients over age the age of 40 years (146), but no subdivision into the various types of LQTS was performed. The exact reason for such an augmentation is not known, but may be related to longer QTc intervals in patients with coronary artery disease (147, 148). Alternatively, it may be consequent to alterations in the tissue substrate (e.g., ischemia, scar formation, reduced ejection fraction) which may lower the threshold for afterdepolarizations in LQTS, a critical factor in the initiation of torsade de pointes that is thought to be the arrhythmogenic mechanism in LQTS-related cardiac events [see (146)]. Thus, it appears that coronary artery disease may enhance the risk for cardiac events in both BrS and LQTS patients, but further clinical studies are required to substantiate these observations.

Conclusions

Genetic modifiers, (common) co-morbidities, environmental influences, and life style factors including diet and exercise may modify disease expressivity and severity, and as such significantly modulate the risk for arrhythmia occurrence and survival in SCN5A channelopathy. Importantly, the impact of modulatory factors may differ between distinct mutations, but may also vary with age and gender. Hence, clinical management of patients with SCN5A mutations should include careful and continuous assessment of co-existing diseases and other modulatory factors, in addition to rigorous treatment of relevant co-morbidities. Identification of disease modifiers will be an essential step in further research related to SCN5A channelopathies and may help to design better risk stratification algorithms and to improve development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by an Innovational Research Incentives Scheme Vidi grant from ZonMw (grant no. 91714371, to CR), in addition to the Netherlands CardioVascular Research Initiative, an initiative with support from the Dutch Heart Foundation (CVON2012-10 PREDICT and CVON2015-12 e-DETECT).

References

- 1.Tan HL, Bezzina CR, Smits JP, Verkerk AO, Wilde AAM. Genetic control of sodium channel function. Cardiovasc Res. (2003) 57:961–73. 10.1016/S0008-6363(02)00714-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Remme CA. Cardiac sodium channelopathy associated with SCN5A mutations: electrophysiological, molecular and genetic aspects. J Physiol. (2013) 591:4099–116. 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.256461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilde AAM, Amin AS. Clinical apectrum of SCN5A mutations: long QT syndrome, Brugada syndrome, and cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol Clin Electrophysiol. (2018) 4:569–79. 10.1016/j.jacep.2018.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Remme CA, Wilde AAM. SCN5A overlap syndromes: no end to disease complexity? Europace (2008) 10:1253–5. 10.1093/europace/eun267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Remme CA, Verkerk AO, Hoogaars WM, Aanhaanen WT, Scicluna BP, Annink C, et al. The cardiac sodium channel displays differential distribution in the conduction system and transmural heterogeneity in the murine ventricular myocardium. Basic Res Cardiol. (2009) 104:511–22. 10.1007/s00395-009-0012-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weidmann S. The effect of the cardiac membrane potential on the rapid availability of the sodium-carrying system. J Physiol. (1955) 127:213–24. 10.1113/jphysiol.1955.sp005250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zygmunt AC, Eddlestone GT, Thomas GP, Nesterenko VV, Antzelevitch C. Larger late sodium conductance in M cells contributes to electrical heterogeneity in canine ventricle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2001) 281:H689–97. 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.2.H689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baruscotti M, DiFrancesco D, Robinson RB. Na+ current contribution to the diastolic depolarization in newborn rabbit SA node cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2000) 279:H2303–09. 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.5.H2303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kokubun S, Nishimura M, Noma A, Irisawa H. Membrane currents in the rabbit atrioventricular node cell. Pflugers Arch. (1982) 393:15–22. 10.1007/BF00582385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lei M, Jones SA, Liu J, Lancaster MK, Fung SS, Dobrzynski H, et al. Requirement of neuronal- and cardiac-type sodium channels for murine sinoatrial node pacemaking. J Physiol. (2004) 559:835–48. 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.068643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verstraelen TE, Ter Bekke RM, Volders PG, Masclee AA, Kruimel JW. The role of the SCN5A-encoded channelopathy in irritable bowel syndrome and other gastrointestinal disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil. (2015) 27:906–13. 10.1111/nmo.12569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parisi P, Oliva A, Coll Vidal M, Partemi S, Campuzano O, Iglesias A, et al. Coexistence of epilepsy and Brugada syndrome in a family with SCN5A mutation. Epilepsy Res. (2013) 105:415–8. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2013.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balser JR. Structure and function of the cardiac sodium channels. Cardiovasc Res. (1999) 42:327–38. 10.1016/S0008-6363(99)00031-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berecki G, Wilders R, de Jonge B, van Ginneken ACG, Verkerk AO. Re-evaluation of the action potential upstroke velocity as a measure of the Na+ current in cardiac myocytes at physiological conditions. PLoS ONE (2010) 5:e15772. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Remme CA, Verkerk AO, Nuyens D, van Ginneken ACG, van Brunschot S, Belterman CN, et al. Overlap syndrome of cardiac sodium channel disease in mice carrying the equivalent mutation of human SCN5A-1795insD. Circulation (2006) 114:2584–94. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.653949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lieve KV, Verkerk AO, Podliesna S, van der Werf C, Tanck MW, Hofman N, et al. Gain-of-function mutation in SCN5A causes ventricular arrhythmias and early onset atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. (2017) 236:187–93. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.01.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Savio-Galimberti E, Gollob MH, Darbar D. Voltage-gated sodium channels: biophysics, pharmacology, and related channelopathies. Front Pharmacol. (2012) 11:124 10.3389/fphar.2012.00124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meregalli PG, Wilde AAM, Tan HL. Pathophysiological mechanisms of Brugada syndrome: depolarization disorder, repolarization disorder, or more? Cardiovasc Res. (2005) 67:367–78. 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwartz PJ. The congenital long QT syndromes from genotype to phenotype: clinical implications. J Intern Med. (2006) 259:39–47. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01583.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Savio-Galimberti E, Darbar D. Atrial fibrillation and SCN5A variants. Card Electrophysiol Clin. (2014) 6:741–8. 10.1016/j.ccep.2014.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ziyadeh-Isleem A, Clatot J, Duchatelet S, Gandjbakhch E, Denjoy I, Hidden-Lucet F, et al. A truncated SCN5A mutation combined with genetic variability causes sick sinus syndrome and early atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. (2014) 11:1015–23. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.02.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellinor PT, Nam EG, Shea MA, Milan DJ, Ruskin JN, MacRae CA. Cardiac sodium channel mutation in atrial fibrillation. Heart. Rhythm. (2008) 5, 99–105. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verkerk AO, Wilders R. Pacemaker activity of the human sinoatrial node: an update on the effects of mutations in HCN4 on the hyperpolarization-activated current. Int J Mol Sci. (2015) 16, 3071–3094. 10.3390/ijms16023071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayashi H, Sumiyoshi M, Nakazato Y, Daida H. Brugada syndrome and sinus node dysfunction. J Arrhythmia. (2018) 34, 216–221. 10.1002/joa3.12046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilders R. Sinus bradycardia in carriers of the SCN5A-1795insD mutation: unraveling the mechanism through computer simulations. Int J Mol Sci. (2018) 19:E634. 10.3390/ijms19020634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilders R, Verkerk AO. Long QT syndrome and sinus bradycardia - a mini review. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2018) 5:106. 10.3389/fcvm.2018.00106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Opdal SH, Rognum TO. The sudden infant death syndrome gene: does it exist? Pediatrics (2004) 114:e506–12. 10.1542/peds.2004-0683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klaver EC, Versluijs GM, Wilders R. Cardiac ion channel mutations in the sudden infant death syndrome. Int J Cardiol. (2011) 152:162–70. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.12.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ioakeimidis NS, Papamitsou T, Meditskou S, Zafiroula Iakovidou-Kritsi Z. Sudden infant death syndrome due to long QT syndrome: a brief review of the genetic substrate and prevalence. J Biol Res(Thessalon) (2017) 24:6. 10.1186/s40709-017-0063-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hershberger RE, Hedges DJ, Morales A. Dilated cardiomyopathy: the complexity of a diverse genetic architecture. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2013) 10:531–47. 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McNair WP, Ku L, Taylor MR, Fain PR, Dao D, Wolfel E, et al. SCN5A mutation associated with dilated cardiomyopathy, conduction disorder, and arrhythmia. Circulation (2004) 110:2163–7. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000144458.58660.BB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bezzina CR, Remme CA. Dilated cardiomyopathy due to sodium channel dysfunction: what is the connection? Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2008) 1:80–2. 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.791434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Veerman CC, Wilde AAM, Lodder EM. The cardiac sodium channel gene SCN5A and its gene product NaV1.5: role in physiology and pathophysiology. (2015) Gene 573, 177–187. 10.1016/j.gene.2015.08.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basso C, Corrado D, Marcus FI, Nava A, Thiene G. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Lancet (2009) 373:1289–300. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60256-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kapplinger JD, Landstrom AP, Salisbury BA, Callis TE, Pollevick GD, Tester DJ, et al. Distinguishing arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia-associated mutations from background genetic noise. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2011) 57:2317–27. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.12.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Basso C, Corrado D, Bauce B, Thiene G. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2012) 5:1233–46. 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.962035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu J, Hu J, Dai X, Cao Q, Xiong Q, Liu X, et al. SCN5A mutation in Chinese patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. Herz (2014) 39:271–5. 10.1007/s00059-013-3998-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sato PY, Musa H, Coombs W, Guerrero-Serna G, Patiño GA, Taffet SM, et al. Loss of plakophilin-2 expression leads to decreased sodium current and slower conduction velocity in cultured cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. (2009) 105:523–6. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.201418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rizzo S, Lodder EM, Verkerk AO, Wolswinkel R, Beekman L, Pilichou K, et al. Intercalated disc abnormalities, reduced Na+ current density, and conduction slowing in desmoglein-2 mutant mice prior to cardiomyopathic changes. Cardiovasc Res. (2012) 95:409–18. 10.1093/cvr/cvs219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilders R. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: considerations from in silico experiments. Front Physiol. (2012) 3:168. 10.3389/fphys.2012.00168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Probst V, Wilde AAM, Barc J, Sacher F, Babuty D, Mabo P, et al. SCN5A mutations and the role of genetic background in the pathophysiology of Brugada syndrome. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. (2009) 2:552–7. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.853374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meregalli PG, Tan HL, Probst V, Koopmann TT, Tanck MW, Bhuiyan ZA, et al. Type of SCN5A mutation determines clinical severity and degree of conduction slowing in loss-of-function sodium channelopathies. Heart Rhythm. (2009) 6:341–8. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bezzina C, Veldkamp MW, van den Berg MP, Postma AV, Rook MB, Viersma JW, et al. A single Na+ channel mutation causing both long-QT and Brugada syndromes. Circ Res (1999) 85:1206–13. 10.1161/01.RES.85.12.1206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Postema PG, Wolpert C, Amin AS, Probst V, Borggrefe M, Roden DM, et al. Drugs and Brugada syndrome patients: review of the literature, recommendations, and an up-to-date website (www.brugadadrugs.org). Heart Rhythm. (2009) 6:1335–41. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoogendijk MG, Potse M, Vinet A, de Bakker JMT, Coronel R. ST segment elevation by current-to-load mismatch: an experimental and computational study. Heart Rhythm. (2011) 8:111–8. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.09.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paci M, Passini E, Severi S, Hyttinen J, Rodriguez B. Phenotypic variability in LQT3 human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes and their response to antiarrhythmic pharmacologic therapy: an in silico approach. Heart Rhythm. (2017) 14:1704–12. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.07.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kyndt F, Probst V, Potet F, Demolombe S, Chevallier JC, Baro I, et al. Novel SCN5A mutation leading either to isolated cardiac conduction defect or Brugada syndrome in a large French family. Circulation (2001) 104:3081–6. 10.1161/hc5001.100834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van den Berg MP, Wilde AAM, Viersma TJW, Brouwer J, Haaksma J, van der Hout AH, et al. Possible bradycardic mode of death and successful pacemaker treatment in a large family with features of long QT syndrome type 3 and Brugada syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. (2001) 12:630–6. 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00630.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kolder IC, Tanck MW, Bezzina CR. Common genetic variation modulating cardiac ECG parameters and susceptibility to sudden cardiac death. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2012) 52:620–9. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Remme CA, Scicluna BP, Verkerk AO, Amin AS, van Brunschot S, Beekman L, et al. Genetically determined differences in sodium current characteristics modulate conduction disease severity in mice with cardiac sodium channelopathy. Circ Res. (2009) 104:1283–92. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.194423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rivaud MR, Baartscheer A, Verkerk AO, Beekman L, Rajamani S, Belardinelli L, et al. Enhanced late sodium current underlies pro-arrhythmic intracellular sodium and calcium dysregulation in murine sodium channelopathy. Int J Cardiol. (2018) 263:54–62. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.03.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scicluna BP, Tanck MW, Remme CA, Beekman L, Coronel R, Wilde AAM, et al. Quantitative trait loci for electrocardiographic parameters and arrhythmia in the mouse. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2011) 50:380–9. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lodder EM, Scicluna BP, Milano A, Sun AY, Tang H, Remme CA, et al. Dissection of a quantitative trait locus for PR interval duration identifies Tnni3k as a novel modulator of cardiac conduction. PLoS Genet. (2012) 8:e1003113. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ackerman MJ, Splawski I, Makielski JC, Tester DJ, Will ML, Timothy KW, et al. Spectrum and prevalence of cardiac sodium channel variants among black, white, Asian, and Hispanic individuals: implications for arrhythmogenic susceptibility and Brugada/long QT syndrome genetic testing. Heart Rhythm. (2004) 1:600–7. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Viswanathan PC, Benson DW, Balser JR. A common SCN5A polymorphism modulates the biophysical effects of an SCN5A mutation. J Clin Invest. (2003) 111:341–6. 10.1172/JCI200316879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ye B, Valdivia CR, Ackerman MJ, Makielski JC. A common human SCN5A polymorphism modifies expression of an arrhythmia causing mutation. Physiol Genomics (2003) 12:187–93. 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00117.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Poelzing S, Forleo C, Samodell M, Dudash L, Sorrentino S, Anaclerio M, et al. SCN5A polymorphism restores trafficking of a Brugada syndrome mutation on a separate gene. Circulation (2006) 114:368–76. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.601294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gui J, Wang T, Trump D, Zimmer T, Lei M. Mutation-specific effects of polymorphism H558R in SCN5A-related sick sinus syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. (2010) 21:564–73. 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2010.01762.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marangoni S, Di Resta C, Rocchetti M, Barile L, Rizzetto R, Summa A, et al. A Brugada syndrome mutation (p.S216L) and its modulation by p.H558R polymorphism: standard and dynamic characterization. Cardiovasc Res. (2011) 91:606–16. 10.1093/cvr/cvr142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shinlapawittayatorn K, Du XX, Liu H, Ficker E, Kaufman ES, Deschênes I. A common SCN5A polymorphism modulates the biophysical defects of SCN5A mutations. Heart Rhythm. (2011) 8:455–62. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.11.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bezzina CR, Shimizu W, Yang P, Koopmann TT, Tanck MW, Miyamoto Y, et al. Common sodium channel promoter haplotype in asian subjects underlies variability in cardiac conduction. Circulation. (2006) 113:338–44. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.580811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Groenewegen WA, Firouzi M, Bezzina CR, Vliex S, van Langen IM, Sandkuijl L, et al. A cardiac sodium channel mutation cosegregates with a rare connexin40 genotype in familial atrial standstill. Circ Res. (2003) 92:14–22. 10.1161/01.RES.0000050585.07097.D7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Makielski JC, Ye B, Valdivia CR, Pagel MD, Pu J, Tester DJ, et al. A ubiquitous splice variant and a common polymorphism affect heterologous expression of recombinant human SCN5A heart sodium channels. Circ Res. (2003) 93:821–8. 10.1161/01.RES.0000096652.14509.96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tan BH, Valdivia CR, Song C, Makielski JC. Partial expression defect for the SCN5A missense mutation G1406R depends on splice variant background Q1077 and rescue by mexiletine. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2006) 291:H1822–8. 10.1152/ajpheart.00101.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheng J, Morales A, Siegfried JD, Li D, Norton N, Song J, et al. SCN5A rare variants in familial dilated cardiomyopathy decrease peak sodium current depending on the common polymorphism H558R and common splice variant Q1077del. Clin Transl Sci. (2010) 3:287–94. 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2010.00249.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Matsuo K, Akahoshi M, Nakashima E, Suyama A, Seto S, Hayano M, et al. The prevalence, incidence and prognostic value of the Brugada-type electrocardiogram: a population-based study of four decades. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2001) 38:765–70. 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01421-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wilde AAM, Moss AJ, Kaufman ES, Shimizu W, Peterson DR, Benhorin J, et al. Clinical aspects of type 3 long-QT syndrome: an international multicenter study. Circulation (2016) 134:872–8. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Verkerk AO, Wilders R, de Geringel W, Tan HL. Cellular basis of sex disparities in human cardiac electrophysiology. Acta Physiol. (2006) 187:459–77. 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2006.01586.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Barajas-Martinez H, Haufe V, Chamberland C, Roy MJ, Fecteau MH, Cordeiro JM, et al. Larger dispersion of INa in female dog ventricle as a mechanism for gender-specific incidence of cardiac arrhythmias. Cardiovasc Res. (2009) 81:82–9. 10.1093/cvr/cvn255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Postema PG, Wilde AAM. Aging in brugada syndrome: what about risks? JACC Clin Electrophysiol. (2017) 3:68–70. 10.1016/j.jacep.2016.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Postema PG, Tan HL, Wilde AAM. Ageing and Brugada syndrome: considerations and recommendations. J Geriatr Cardiol. (2013) 10:75–81. 10.3969/j.issn.1671-5411.2013.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Beaufort-Krol GC, van den Berg MP, Wilde AAM, van Tintelen JP, Viersma JW, Bezzina CR, et al. Developmental aspects of long QT syndrome type 3 and Brugada syndrome on the basis of a single SCN5A mutation in childhood. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2005) 46:331–337. 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Baba S, Dun W, Hirose M, Boyden PA. Sodium current function in adult and aged canine atrial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2006) 291:H756–61. 10.1152/ajpheart.00063.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Signore S, Sorrentino A, Borghetti G, Cannata A, Meo M, Zhou Y, et al. Late Na+ current and protracted electrical recovery are critical determinants of the aging myopathy. Nat Commun. (2015) 6:8803. 10.1038/ncomms9803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chadda KR, Ahmad S, Valli H, den Uijl I, Al-Hadithi AB, Salvage SC, et al. The effects of ageing and adrenergic challenge on electrocardiographic phenotypes in a murine model of long QT syndrome type 3. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:11070. 10.1038/s41598-017-11210-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Probst V, Kyndt F, Potet F, Trochu JN, Mialet G, Demolombe S, et al. Haploinsufficiency in combination with aging causes SCN5A-linked hereditary Lene‘gre disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2003) 41:643–52. 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)02864-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Royer A, van Veen TAB, Le Bouter S, Marionneau C, Griol-Charhbili V, Léoni AL, et al. Mouse model of SCN5A-linked hereditary Lenègre's disease: age-related conduction slowing and myocardial fibrosis. Circulation (2005) 111:1738–46. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000160853.19867.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Postema PG, Neville J, de Jong JSSG, Romero K, Wilde AAM, Woosley RL. Safe drug use in long QT syndrome and Brugada syndrome: comparison of website statistics. Europace (2013) 15:1042–9. 10.1093/europace/eut018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yap YG, Behr ER, Camm AJ. Drug-induced Brugada syndrome. Europace (2009) 11:989–94. 10.1093/europace/eup114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fazio G, Vernuccio F, Grutta G, Lo Re G. Drugs to be avoided in patients with long QT syndrome: vocus on the anaesthesiological management. World J Cardiol. (2013) 5:87–93. 10.4330/wjc.v5.i4.87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Diness JG, Hansen RS, Nissen JD, Jespersen T, Grunnet M. Antiarrhythmic effect of IKr activation in a cellular model of LQT3. Heart Rhythm. (2009) 6:100–6. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Achaiah A, Andrews N. Intoxication with alcohol: an underestimated trigger of Brugada syndrome? JRSM Open (2016) 7:2054270416640153. 10.1177/2054270416640153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Klein G, Gardiwal A, Schaefer A, Panning B, Breitmeier D. Effect of ethanol on cardiac single sodium channel gating. Forensic Sci Int. (2007) 171:131–5. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2006.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bebarova M, Matejovic P, Pasek M, Simurdova M, Simurda J. Dual effect of ethanol on inward rectifier potassium current IK1 in rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol Pharmacol. (2014) 65:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Uyarel H, Ozdol C, Gencer AM, Okmen E, Cam N. Acute alcohol intake and QT dispersion in healthy subjects. J Stud Alcohol. (2005) 66:555–558. 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.O'Leary ME, Hancox JC. Role of voltage-gated sodium, potassium and calcium channels in the development of cocaine-associated cardiac arrhythmias. Br J Clin Pharmacol. (2010) 69:427–42. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03629.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sartiani L, Cerbai E, Lonardo G, DePaoli P, Tattoli M, Cagiano R, et al. Prenatal exposure to carbon monoxide affects postnatal cellular electrophysiological maturation of the rat heart: a potential substrate for arrhythmogenesis in infancy. Circulation (2004) 109:419–23. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000109497.73223.4D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ton AT, Biet M, Delabre J-F, Morin N, Dumaine R. In-utero exposure to nicotine alters the development of the rabbit cardiac conduction system and provides a potential mechanism for sudden infant death syndrome. Arch Toxicol. (2017) 91:3947–60. 10.1007/s00204-017-2006-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dallas ML, Yang ML, Boyle Z, Boycott JP, Scragg HE, Milligan JL, et al. Carbon monoxide induces cardiac arrhythmia via induction of the late Na current. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2012) 186:648–56. 10.1164/rccm.201204-0688OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Splawski I, Shen J, Timothy KW, Lehmann MH, Priori S, Robinson JL, et al. Spectrum of mutations in long-QT syndrome genes. KVLQT1, HERG, SCN5A, KCNE1, and KCNE2. Circulation (2000) 102:1178–85. 10.1161/01.CIR.102.10.1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Potet F, Beckermann TM, Kunic JD, George AL, Jr. Intracellular calcium attenuates late current conducted by mutant human cardiac sodium channels. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2015) 8:933–41. 10.1161/CIRCEP.115.002760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mascia G, Arbelo E, Hernández-Ojeda J, Solimene F, Brugada R, Brugada J. Brugada syndrome and exercise practice: current knowledge, shortcomings and open questions. Int J Sports Med. (2017) 38:573–81. 10.1055/s-0043-107240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mascia G, Arbelo E, Solimene F, Giaccardi M, Brugada R, Brugada J. The long-QT syndrome and exercise practice: the never-ending debate. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. (2018) 29:489–96. 10.1111/jce.13410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.D'Souza A, Bucchi A, Johnsen A-B, Logantha SJRJ, Monfredi O, Yanni J, et al. Exercise training reduces resting heart rate via downregulation of the funny channel HCN4. Nat Commun. (2014) 5:3775. 10.1038/ncomms4775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Salem KA, Qureshi MA, Sydorenko V, Parekh K, Jayaprakash P, Iqbal T, Singh J, et al. Effects of exercise training on excitation-contraction coupling and related mRNA expression in hearts of Goto-Kakizaki type 2 diabetic rats. Mol Cell Biochem. (2013) 380:83–96. 10.1007/s11010-013-1662-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Stones R, Billeter R, Zhang H, Harrison S, White E. The role of transient outward K+ current in electrical remodelling induced by voluntary exercise in female rat hearts. Basic Res Cardiol. (2009) 104:643–52. 10.1007/s00395-009-0030-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Xiao YF, Kang JX, Morgan JP, Leaf A. Blocking effects of polyunsaturated fatty acids on Na+ channels in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1995) 92:11000–4. 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yagi S, Soeki T, Aihara KI, Fukuda D, Ise T, Kadota M, et al. Low serum levels of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid are risk factors for cardiogenic syncope in patients with Brugada syndrome. Int Heart J. (2017) 58:720–3. 10.1536/ihj.16-278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Macleod JC, Macknight ADC, Rodrigo GC. The electrical andmechanical response of adult guinea pig and rat ventricular myocytes to omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Eur J Pharmacol. (1998) 356:261–70. 10.1016/S0014-2999(98)00528-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wu CC, Su MJ, Chi JF, Wu MH, Lee YT. Comparison of aging and hypercholesterolemic effects on the sodium inward currents in cardiac myocytes. Life Sci. (1997) 61:1539–51. 10.1016/S0024-3205(97)00733-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ikeda T, Abe A, Yusu S, Nakamura K, Ishiguro H, Mera H, et al. The full stomach test as a novel diagnostic technique for identifying patients at risk of Brugada syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. (2006) 17:602–7. 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00424.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ozyilmaz I, Akyol B, Ergul Y. Sudden cardiac arrest while eating a hot dog: a rare presentation of Brugada syndrome in a child. Pediatrics (2017) 140:e20162485. 10.1542/peds.2016-2485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chanavirut R, Leelayuwat N. Brugada syndrome and carbohydrate metabolism. J Cardiol Curr Res. (2017) 8:00294 10.15406/jccr.2017.08.00294 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hansen PS, Buhagiar KA, Gray DF, Rasmussen HH. Voltage-dependent stimulation of the Na+-K+ pump by insulin in rabbit cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. (2000) 278:C546–53. 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.3.C546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Aulbach F, Simm A, Maier S, Langenfeld H, Walter U, Kersting U, et al. Insulin stimulates the L-type Ca2+ current in rat cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. (1999) 42:113–20. 10.1016/S0008-6363(98)00307-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Shi YQ, Yan M, Liu LR, Zhang X, Wang X, Geng HZ, et al. High glucose represses hERG K+ channel expression through trafficking inhibition. Cell Physiol Biochem. (2015) 37:284–96. 10.1159/000430353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wu M, Obara Y, Norota I, Nagasawa Y, Ishii K. Insulin suppresses IKs (KCNQ1/KCNE1) currents, which require β-subunit KCNE1. Pflügers Arch. (2014) 466:937–46. 10.1007/s00424-013-1352-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gastaldelli A, Emdin M, Conforti F, Camastra S, Ferrannini E. Insulin prolongs the QTc interval in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. (2000) 279:R2022–5. 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.6.R2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Skinner JR, Marquis-Nicholson R, Luangpraseuth A, Cutfield R, Crawford J, Love DR. Diabetic dead-in-bed syndrome: a possible link to a cardiac ion channelopathy. Case Rep Med. (2014) 2014:47252. 10.1155/2014/647252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Li J, Hu D, Song X, Han T, Gao Y, Xing Y. The role of biologically asctive ingredients from natural drug treatments for arrhythmias in different mechanisms. Biomed Res Int. (2017) 2017:4615727. 10.1155/2017/4615727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Heart Rhythm Society of the Chinese Society of Biomedical Engineering, and Nao Xin Tong Zhi Committee of the Chinese Association of Integrative Medicine Expert consensus on Wenxin granule for treatment of cardiac arrhythmias. Chin Med J. (2017) 130, 203–10. 10.4103/0366-6999.198003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Minoura Y, Panama BK, Nesterenko VV, Betzenhauser M, Barajas-Martínez H, Hu D, et al. Effect of Wenxin Keli and quinidine to suppress arrhythmogenesis in an experimental model of Brugada syndrome. Heart Rhythm. (2013) 10:1054 −62. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hou JW, Li W, Guo K, Chen XM, Chen YH, Li CY, et al. Antiarrhythmic effects and potential mechanism of WenXin KeLi in cardiac Purkinje cells. Heart Rhythm. (2016) 13:973–82. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Xue X, Guo D, Sun H, Wang D, Li J, Liu T, et al. Wenxin Keli suppresses ventricular triggered arrhythmias via selective inhibition of late sodium current. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. (2013) 36:732–40. 10.1111/pace.12109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Fish JM, Welchons DR, Kim YS, Lee SH, Ho WK, Antzelevitch C. Dimethyl lithospermate B, an extract of Danshen, suppresses arrhythmogenesis associated with the Brugada syndrome. Circulation (2006) 113:1393–400. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.601690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Shah SR, Park K. Long QT syndrome: a comprehensive review of the literature and current evidence. Curr Probl Cardiol. (2018). 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2018.04.002. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Mordukhovich I, Kloog I, Coull B, Koutrakis P, Vokonas P, Schwartz J. Association between particulate air pollution and QT interval duration in an elderly cohort. Epidemiology (2016) 27:284–90. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hahad O, Beutel M, Gori T, Schulz A, Blettner M, Pfeiffer N, Rostock T, et al. Annoyance to different noise sources is associated with atrial fibrillation in the Gutenberg Health Study. Int J Cardiol. (2018) 264:79–84. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.03.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Münzel T, Sørensen M, Schmidt F, Schmidt E, Steven S, Kröller-Schön S, et al. The adverse effects of environmental noise exposure on oxidative stress and cardiovascular risk. Antioxid Redox Signal. (2018) 28:873–908. 10.1089/ars.2017.7118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Amin AS, Klemens CA, Verkerk AO, Meregalli PG, Asghari-Roodsari A, de Bakker JMT, et al. Fever-triggered ventricular arrhythmias in Brugada syndrome and type 2 long-QT syndrome. Neth Heart J. (2010) 18:165–9. 10.1007/BF03091755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Egri C, Ruben PC. A hot topic. Channels (2012) 6:75–85. 10.4161/chan.19827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Amin AS, Verkerk AO, Bhuiyan ZA, Wilde AAM, Tan HL. Novel Brugada syndrome-causing mutation in ion-conducting pore of cardiac Na+ channel does not affect ion selectivity properties. Acta Physiol Scand. (2005) 185:291–301. 10.1111/j.1365-201X.2005.01496.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Dumaine R, Towbin JA, Brugada P, Vatta M, Nesterenko DV, Nesterenko VV, et al. Ionic mechanisms responsible for the electrocardiographic phenotype of the Brugada syndrome are temperature dependent. Circ Res. (1999) 85:803–9. 10.1161/01.RES.85.9.803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Nagatomo T, Fan Z, Ye B, Tonkovich GS, January CT, Kyle JW, et al. Temperature dependence of early and late currents in human cardiac wild-type and long QT Delta KPQ Na channels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (1998) 275:2016–24. 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.6.H2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Burashnikov A, Shimizu W, Antzelevitch C. Fever accentuates transmural dispersion of repolarization and facilitates development of early afterdepolarizations and torsade de pointes under long-QT Conditions. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2008) 1:202–8. 10.1161/CIRCEP.107.691931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Lu Z, Jiang YP, Wu CY, Ballou LM, Liu S, Carpenter ES, et al. Increased persistent sodium current due to decreased PI3K signalling contributes to QT prolongation in the diabetic heart. Diabetes (2013) 62:4257–65. 10.2337/db13-0420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Veglio M, Borra M, Stevens LK, Fuller JH, Perin PC. The relation between QTc interval prolongation and diabetic complications. Diabetologia (1999) 42:68–75. 10.1007/s001250051115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Chapalamadugu K, Panguluri SK, Miranda A, Sneed KB, Tipparaju SM. Pharmacogenomics of cardiovascular complications in diabetes and obesity. Recent Pat Biotechnol. (2014) 8:123–35. 10.2174/1872208309666140904123023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Stables CL, Musa H, Mitra A, Bhushal S, Deo M, Guerrero-Serna G, et al. Reduced Na+ current density underlies impaired propagation in the diabetic rabbit ventricle. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2015) 69:24–31. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.12.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Yu P, Hu L, Xie J, Chen S, Huang L, Xu Z, et al. O-GlcNAcylation of cardiac Nav1.5 contributes to the development of arrhythmias in diabetic hearts. Int J Cardiol (2018) 260, 74–81. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.02.099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Pi-Sunyer FX. The obesity epidemic: pathophysiology and consequences of obesity. Obes Res. (2002) 10:97S–104S. 10.1038/oby.2002.202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Aromolaran AS, Boutjdir M. Cardiac ion channel regulation in obesity and the metabolic syndrome: relevance to long QT syndrome and atrial fibrillation. Front. Physiol. (2017) 8:431. 10.3389/fphys.2017.00431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Huang H, Amin V, Gurin M, Wan E, Thorp E, Homma S, et al. Diet-induced obesity causes long QT and reduces transcription of voltage-gated potassium channels. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2013) 59:151–8. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Nadruz W. Myocardial remodeling in hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. (2015) 29:1–6. 10.1038/jhh.2014.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Coronel R, Casini S, Koopmann TT, Wilms-Schopman FJG, Verkerk AO, de Groot JR, et al. Right ventricular fibrosis and conduction delay in a patient with clinical signs of Brugada syndrome: a combined electrophysiological, genetic, histopathologic, and computational study. Circulation (2005) 112:2769–77. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.532614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Remme CA, Wilde AAM. Late sodium current inhibition in acquired and inherited ventricular (dys)function and arrhythmias. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. (2013) 27:91–101. 10.1007/s10557-012-6433-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Rivaud MR, Jansen JA, Postema PG, Nannenberg EA, Mizusawa Y, van der Nagel R, et al. A common co-morbidity modulates disease expression and treatment efficacy in inherited cardiac sodium channelopathy. Eur Heart J. (2018) 39:2898–907. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Claes GR, van Tienen FH, Lindsey P, Krapels IP, Helderman-van den Enden AT, Hoos MB, et al. Hypertrophic remodelling in cardiac regulatory myosin light chain (MYL2) founder mutation carriers. Eur Heart J. (2016) 37:1815–1822. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Noda T, Shimizu W, Taguchi A, Satomi K, Suyama K, Kurita T, et al. ST-segment elevation and ventricular fibrillation without coronary spasm by intracoronary injection of acetylcholine and/or ergonovine maleate in patients with Brugada syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2002) 40:1841–7. 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)02494-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Sasaki T, Niwano S, Kitano Y, Izumi T. Two cases of Brugada syndrome associated with spontaneous clinical episodes of coronary vasospasm. Intern Med. (2006) 45:77–80. 10.2169/internalmedicine.45.1404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Nishizaki M, Fujii H, Ashikaga T, Yamawake N, Sakurada H, Hiraoka M. ST-T wave changes in a patient complicated with vasospastic angina and Brugada syndrome: differential responses to acetylcholine in right and left coronary artery. Heart Vessels. (2008) 23:201–5. 10.1007/s00380-007-1036-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Ohkubo K, Watanabe I, Okumura Y, Kofune M, Nagashima K, Mano H, et al. Brugada syndrome in the presence of coronary artery disease. J Arrhyth. (2013) 29:211–6. 10.1016/j.joa.2012.09.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Ong P, Bastiaenen R, Batchvarov VN, Athanasiadis A, Raju H, Kaski JC, et al. Prevalence of the type 1 Brugada electrocardiogram in Caucasian patients with suspected coronary spasm. Europace (2011) 13:1625–31. 10.1093/europace/eur205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.van Hoorn F, Campian ME, Spijkerboer A, Blom MT, Planken RN, van Rossum AC, et al. SCN5A mutations in Brugada syndrome are associated with increased cardiac dimensions and reduced contractility. PLoS ONE (2012) 7:e42037. 10.1371/journal.pone.0042037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Kujime S, Sakurada H, Saito N, Enomoto Y, Ito N, Nakamura K, et al. Outcomes of Brugada syndrome patients with coronary artery vasospasm. Intern Med. (2017) 56:129–35. 10.2169/internalmedicine.56.7307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Sze E, Moss AJ, Goldenberg I, McNitt S, Jons C, Zareba W, et al. Long QT syndrome in patients over 40 years of age: increased risk for LQTS-related cardiac events in patients with coronary disease. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. (2008) 13:327–31. 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2008.00250.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Dekker JM, Schouten EG, Klootwijk P, Pool J, Kromhout D. Association between QT interval and coronary heart disease in middle-aged and elderly men. Zutphen Study Circ. (1994) 90:779–85. 10.1161/01.CIR.90.2.779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Korantzopoulos P, Letsas KP, Christogiannis Z, Kalantzi K, Massis I, Milionis HJ, et al. Exercise-induced repolarization changes in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. (2011) 107:37–40. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.08.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]