Abstract

Background

Non‐motor fluctuations represent a main source of disability in Parkinson's disease (PD). Among them, neuropsychiatric fluctuations are the most frequent and are often under‐recognized by patients and physicians, partly because specific tools for assessment of neuropsychiatric fluctuations are lacking.

Objective

To develop a scale for detecting and evaluating the presence and the severity of neuropsychological symptoms during the ON and OFF phases of non‐motor fluctuations.

Methods

Neuropsychiatric symptoms reported by PD patients in the OFF‐ and the ON‐medication conditions were collected using different neuropsychiatric scales (BDI‐II, BAI, Young, VAS, etc.). Subsequently, tree phases of a pilot study was performed for cognitive pretesting, identification of ambiguous or redundant items (item reduction), and to obtain preliminary data of acceptability of the new scale. In all the three phases, the scale was applied in both the OFF and ON condition during a levodopa challenge.

Results

Twenty items were selected for the final version of the neuropsychiatric fluctuation scale (NFS): ten items measured the ON neuropsychological symptoms and ten items the OFF neuropsychological manifestations. Each item rated from 0‐3, providing respective subscores from 0 to 30.

Conclusions

Once validated, our NFS can be used to identify and quantify neuropsychiatric fluctuations during motor fluctuations. The main novelty is that it could be used in acute settings. As such, the NFS can assess the neuropsychiatric state of the patient at the time of examination. The next step will be to validate the NFS to be used in current practice.

Introduction

Although non‐motor symptoms in Parkinson's disease (PD) have been reported since the first description of the disease, for a long time PD has been considered mainly as a motor disease.1 There is a growing attention to non‐motor symptoms in PD patients, encompassing neuropsychiatric, autonomic, sensory/pain, and sleep domains.2 These symptoms might occur within the different stages of PD, from the premotor to the advanced phase. Over the course of the disease, some of these non‐motor symptoms might fluctuate in parallel with motor symptoms. These non‐motor fluctuations (NMF) can represent a main source of disability in PD.3, 4 Moreover, up to 47% of patients with motor fluctuations might also suffer from NMF, and this percentage may be underestimated.5 Among NMF, neuropsychiatric fluctuations are the most frequent3, 6, 7, 8 Anxiety, sadness, lack of energy and motivation, fatigue, and pain are common symptoms during the OFF medication condition,9 whereas euphoria, well‐being, impulse control disorders (ICD), hypomania, and psychosis might occur during the ON‐medication condition. These neuropsychiatric fluctuations might hasten the development of addiction due to dopaminergic medication,10 since patients might seek the “super ON” (i.e., a “high” feeling experienced during the ON condition), and try to avoid the OFF condition. This behavior would result in auto‐medication, with progressive increase of dose and frequency, until the vicious circle of dopamine dysregulation syndrome.11 Thus, early diagnosis of these neuropsychiatric fluctuations is crucial in order to optimize the management of PD patients.

Neuropsychiatric fluctuations can be under‐recognized by patients in the same way as dyskinesia.12 Moreover, specific tools for detecting and quantifying neuropsychiatric fluctuations are lacking. The Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS),13 which has been, for decades, the most used evaluation tool to assess parkinsonian symptoms, does not include any item to evaluate neuropsychiatric fluctuations. Furthermore, most tools available for NMF are not specific for neuropsychiatric symptoms. They are retrospective self‐questionnaires to be interpreted by both patient and rater, and do not fit for a prompt diagnosis.14, 15, 16, 17

There is also a semi structured interview, the Ardouin Scale for Behavioral Assessment in Parkinson 's Disease, which evaluates hypo‐ and hyperdopaminergic behaviors and can also detect and quantify neuropsychiatric fluctuations by evaluating OFF‐drug dysphoria and ON‐drug euphoria.18, 19 It has been shown that self‐administered questionnaires are more sensitive for the detection of both motor and non‐motor fluctuations than semi‐structured questionnaire.6 Therefore, there is the urgent need for a practical scale able to detect neuropsychiatric fluctuations at specific times in PD patients.

The objective of the present study was to develop a self‐applied assessment of NMF centered on neuropsychiatric symptoms to promptly identify their presence and severity in PD patients.

Material and Methods

The construction of the scale was made according to the following five steps: (a) Identification and selection of items of interest from a pool of neuropsychiatry items; (b) construction and testing of the first draft of the scale (phase 1 of the pilot study); (c) reassessment and reformulation of a second version of the scale with subsequent application (phase 2 of the pilot study); (d) reassessment and reformulation of a third version of the scale with subsequent evaluation (phase 3 of the pilot study); and (e) construction of the final version of the scale.

Identification and Selection of Items

To identify and select neuropsychiatric items of interest, we used data coming from a large database, including 102 advanced PD patients from the movement disorders centers of Grenoble and Lyon (France). This database was developed in the context of a previous study,20 in which patients were assessed in the ON‐ and OFF‐medication conditions using different neuropsychiatric scales, including the Beck Depression Inventory II for depression (BDI‐II),21 the Beck Anxiety Inventory for anxiety (BAI),22 the Starkstein Apathy Scale for apathy,23 a visual analogue scale assessing the “mood and cognitive status” (VAS),24 the Addiction Research Center Inventory (ARCI, a scale used for assessing the acute effects of drugs),25 and the Young Mania rating scale.26 From this database we used the “non‐motor fluctuations” items of the Ardouin Scale of Behavior in Parkinson's Disease18, 19 to detect and select the patients who presented with neuropsychiatric fluctuations. Sixty patients (58.9%) met these criteria. From their data we finally selected 38 neuropsychiatric items that appeared to be the most sensitive during the ON and OFF conditions. Sensitivity was analyzed by means of the raw difference in score magnitude between the ON and OFF condition. Among these 38 items, 27 presented a potentially high difference in magnitude between the ON and OFF condition and 11 an average sensibility, and thus, were eliminated. Among the remaining 27 items, three were found to be redundant and as such removed. A total of 24 items were finally retained.

Construction and Testing (Phase 1 of the Pilot Study)

A preliminary scale was constructed, including these 24 selected neuropsychiatric items: five items coming from the ARCI, five from the BAI, four from the Starkstein apathy scale, four from the BDI‐II, four from the VAS, and two from the young mania rating scale. We then standardized the questions and determined a Likert‐scale‐type of scoring:27 from ‐2 to +2: ‐2 (fully disagree), ‐1 (partly disagree), 0 (neither agree nor disagree), +1 (partially agree), +2 (fully agree). Overall, 13 items described neuropsychological symptoms related to the ON‐condition, and 11 suitable for the OFF‐condition. The total score could vary from ‐48 to + 48. One pilot study was performed for cognitive pretesting, identification of ambiguities and redundancies, and obtaining preliminary data of acceptability and sensitivity between the ON and the OFF condition.

Reassessment and Reformulation (Phase 2 of the Pilot Study)

An adaptation of the scale was made from the phase 1 of the pilot study. The scale was divided in two parts: the ON part (including items describing feelings during the ON‐condition of a levodopa challenge), and the OFF part (including items describing feeling during the OFF‐condition of a levodopa challenge). Scoring options were also modified to a 0 to 3 range (0 [no], 1 [a little], 2 [moderately], 3 [a lot]). As such, two parts of 14 items each of them with a total score ranging from 0–42 were obtained. This new version of the scale was assessed in the second pilot study.

Reassessment and Reformulation (Phase 3 of the Pilot Study)

The scale was readapted again according to the feedback from the second phase of the pilot study. We reworded some items of the OFF part and the ON part, but the overall length of the scale was kept unchanged. This third version was assessed by a third phase.

Construction of the Final Version of the Scale

The OFF part and the ON part of the scale were merged. We further eliminated four redundant items. The final version of the NFS was composed of 20 items, with a mix of ten items measuring the “ON psychological state” and ten items measuring the “OFF psychological state.” The three phases of the pilot study were performed in PD patients who were hospitalized in the Movement Disorders Unit of the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire of Grenoble for treatment adjustments, other investigations, or evaluation before deep brain stimulation surgery.

All patients signed the informed consent form to authorize the utilization of their clinical data in the frame of the research.

Data Analysis

The prevalence of each item in each scale was determined during the OFF and ON medication condition (during a levodopa challenge),28 in order to determine which item was specific to the ON or the OFF or both conditions. For each item of the OFF part, scores between the OFF and ON medication conditions were determined, and the comparison was tested for statistical significance (p < 0.05) using the Wilcoxon test. In a similar manner, items of the ON part were compared in the ON and OFF conditions. These analyses were conducted to identify the items most sensitive to the change of condition and those that were insensitive. For each scale, Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was used to identify the most consistently sensitive items to the change of condition. When the difference between the ON and the OFF conditions was not significant, the item was reformulated or deleted. Data are presented as mean and standard deviation or proportions.

Results

Phase 1 of the Pilot Study

For this study, during a standard levodopa challenge, 30 PD patients filled the scale in the OFF and ON medication conditions. Four patients were excluded from the analysis, two had uncertain diagnosis of idiopathic PD and two were unable to fill correctly the scale because of cognitive impairment. Table 1 shows the main clinical characteristics of the patients.

Table 1.

Demographic Data for the Three Phases of the Pilot Study

| Pilot study 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Means | SD | Range (min‐max) | ||

| Patients | N = 26 | |||

| M/F | 15/11 | |||

| Age | 60 | 9 | 45‐76 | |

| MDS UPDRS III OFF | 34 | 13 | 5‐64 | |

| MDS UPDRS III ON | 16 | 10 | 2‐44 | |

| Hoehn et Yahr | 2 (median) |

ct 25 = 2* ct 75 = 3* |

2‐4 | |

| MMSE | 28 | 2 | 21‐30 | |

| Pilot study 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Means | SD | Range (min‐max) | ||

| Patients | N = 21 | |||

| M/F | 15/5 | |||

| Age | 56 | 11 | 31‐76 | |

| MDS UPDRS III OFF | 41 | 16 | 18‐72 | |

| MDS UPDRS III ON | 16 | 9 | 1,5‐36 | |

| Hoehn et Yahr | 2 (Median) |

ct 25 = 2* ct75 = 2* |

1‐3 | |

| MMSE | 29 | 1 | 26‐30 | |

| Pilot study 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Means | SD | Range (min‐max) | ||

| Patients | N = 16 | |||

| M/F | 9/7 | |||

| MDS UPDRS III OFF | 35 | 12 | 18‐63 | |

| MDS UPDRS III ON | 15 | 10 | 2‐40 | |

Abbreviation: IQ, interquatile.

The analysis of the 24 items showed that five items were highly specific of the OFF medication condition (items 7, 9, 15, 17, 24), five others items were highly specific of the ON medication condition (items 1, 6, 14, 21, 22), and 11 items were sensitive for both the OFF and ON conditions (items 3, 4, 5, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 18, 19, 23; Table 2). Three items were not sensitive (items 2, 16, 19), and were removed. Subsequently, the scale was divided in two parts, one specific for the ON (ON part) and the other for the OFF (OFF part) medication state. The ON part was composed by items sensitive to the ON (items 1, 6, 14, 21, 22) and by reformulated items from those specific to both ON and OFF conditions (items 3, 4, 5, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 18). During the reformulation process, item 20 was found to be redundant with the item 4, whereas item 23 could not be reformulated. Therefore, they were both removed from the ON part. Similarly, the OFF part was composed by items sensitive to the OFF condition (items 7, 9, 15, 17, 24) and by reformulated items from those specific to both ON and OFF conditions (items 3, 5, 8, 10, 12, 13, 18, 20, 23). During the reformulation process, item 4 was redundant with the item 20, whereas item 11 could not be reformulated. These two items were then removed from the OFF part.

Table 2.

Items Specificity

| NFS ‐ OFF | NFS ‐ ON | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items |

Disagree (8) |

0 (0) |

Agree (7) |

Disagree (8) |

0 (0) |

Agree (7) |

| 1 | 9 * | 5 | 16 | 3 | 4 | 23 |

| 2 | 12 | 5 | 13 | 6 | 6 | 18 |

| 3 | 17 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 15 |

| 4 | 22 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 19 |

| 5 | 22 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 17 |

| 6 | 13 | 4 | 13 | 6 | 5 | 19 |

| 7 | 18 | 4 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 12 |

| 8 | 23 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 9 | 14 |

| 9 | 26 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 12 | 11 |

| 10 | 21 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 20 |

| 11 | 24 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 19 |

| 12 | 25 | 2 | 3 | 9 | 6 | 15 |

| 13 | 21 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 13 |

| 14 | 10 | 8 | 12 | 18 | 5 | 7 |

| 15 | 5 | 5 | 20 | 12 | 6 | 12 |

| 16 | 8 | 8 | 14 | 15 | 6 | 9 |

| 17 | 7 | 7 | 16 | 13 | 7 | 10 |

| 18 | 7 | 3 | 20 | 15 | 7 | 9 |

| 19 | 10 | 6 | 14 | 17 | 3 | 10 |

| 20 | 6 | 8 | 16 | 15 | 7 | 8 |

| 21 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 19 | 4 | 7 |

| 22 | 10 | 4 | 16 | 17 | 5 | 8 |

| 23 | 7 | 4 | 19 | 19 | 3 | 8 |

| 24 | 6 | 5 | 19 | 12 | 3 | 15 |

*The numbers represent the number of patients answering each question. In bold: items highly specific to the OFF‐medication condition (1, 6, 14, 21, and 22). In underline: items highly specific to the ON‐medication condition (7, 9, 15, 17, and 24). In grey: items specifics to both conditions.

Phase 2 of the Pilot Study

Twenty‐one patients completed the new version of the scale in both the ON and OFF conditions during a levodopa challenge. Demographics of patients are listed in Table 1.

To control the specificity of both the OFF and ON parts of the scale, patients filled both parts in the OFF and ON medication conditions. Taking into account the results from the statistical analysis and the patient's comments, we reworded the following items: in the OFF scale, 1, 3, 4, 8 and in the ON scale, 1 and 14. The number of items and the global length of the scale were kept unchanged (Table 3). Nevertheless, this new form of the scale was assessed in a third phase.

Table 3.

Wilcoxon Test After the Second Phase of the Pilot Study

| Difference OFF‐OFF to OFF‐ON | p |

|---|---|

| 1. Currently, my thoughts are a little slow. | N.S. |

| 2. At the moment, I feel lethargic. | 0.004 |

| 3. I feel as if something unpleasant has just happened to me. | 0.05 |

| 4. At the moment, it would be difficult for me to plan things properly. | 0.06 |

| 5. Currently, everything seems more unpleasant to me. | 0.0004 |

| 6. At the moment, I lack energy for everyday activities. | 0.0008 |

| 7. At the moment, I feel low. | 0.001 |

| 8. Currently, I don't want to communicate, I feel less talkative. | N.S. |

| 9. At the moment, I feel fragile. | 0.005 |

| 10. Now, I feel so low that other people must notice. | 0.002 |

| 11. At the moment, I am unable to relax. | 0.001 |

| 12. At the moment, I am lacking in confidence. | 0.0003 |

| 13. At the moment, I have “jelly legs, trembling”. | 0.0001 |

| 14. Now, I am tired. | 0.009 |

| DIFFERENCE ON‐ON to ON‐OFF | p |

|---|---|

| 1. At the moment, I want to learn new things. | 0.005 |

| 2. Currently, ideas come to me more easily than usual. | 0.001 |

| 3. At the moment, I feel full of energy. | 0.0002 |

| 4. I feel as if something pleasant has just happened to me. | 0.0001 |

| 5. Currently, everything seems more pleasant to me. | 0.0001 |

| 6. At the moment, I would have enough energy for everyday activities. | 0.0002 |

| 7. I would be permanently satisfied if I could feel like I do now all the time. | 0.0005 |

| 8. At the moment, I feel in top form. | 0.0002 |

| 9. Currently, I feel talkative, I want to communicate. | 0.0001 |

| 10. Now, I am able to concentrate properly on something. | 0.0002 |

| 11. At the moment, I feel sure of myself. | 0.0002 |

| 12. Currently, I feel competent at doing things. | 0.0001 |

| 13. At the moment, I have a feeling of well‐being. | 0.0001 |

| 14. Currently, I feel interested in certain things. | 0.004 |

Phase 3 of the Pilot Study

Sixteen patients filled the third version of the scale in the ON and OFF conditions during the levodopa challenge. They also filled a quality questionnaire to check what they thought about the scale. Clinical data of these patients are available in Table 1.

The analysis of the third phase of the pilot study showed good prevalence (proportion of patients scoring > 0) of items of the ON part in the ON medication condition (average: 96.14%). Conversely, items of the ON part were less prevalent in the OFF medication condition (average: 37.57%). The OFF part items were comparatively less prevalent in the OFF medication condition (average: 74.64%), but also in the ON medication condition (average: 23.32%). Items 1, 3, 8, 9 from the OFF part and item 1 from the ON part were not very sensitive (p > 0.0035).

Construction of the Final Version of the Scale

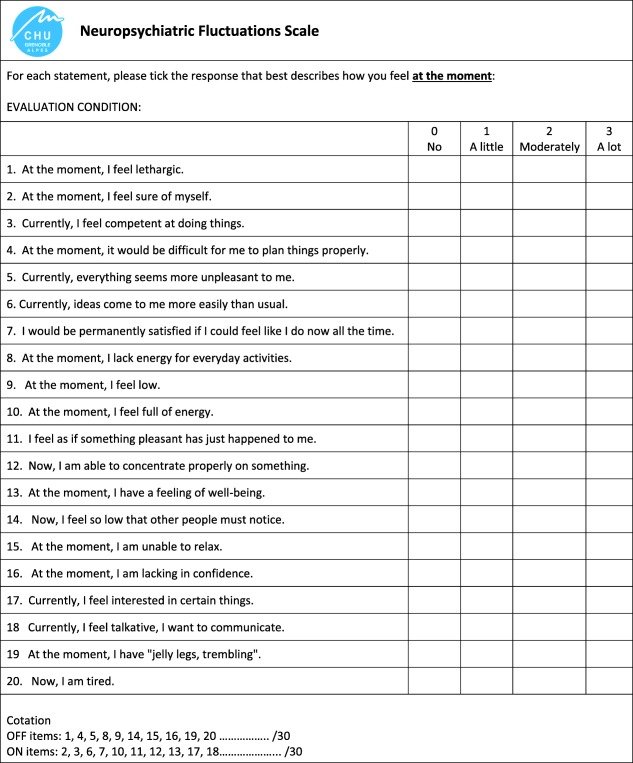

To make the final scale easy to use for both patients and clinicians, we decided to put together the two parts (the ON part and the OFF part; Fig. 1). This fusion allowed eliminating several redundant items from the ON part (items 3, 6, 8, 5, 13) and several not very sensitive items from the OFF part (items 1, 3, 8, 9). This final version of the scale was called the neuropsychiatric fluctuations scale (NFS). The NFS is composed by 20 items, ten items measuring the ON neuropsychological symptoms and ten items for the OFF neuropsychological manifestations, since the ON and OFF items were mixed (Fig. 1). Scoring (0 to 3) and formulation of items remain the same.

Figure 1.

Final version of the “neuropsychiatric fluctuations scale” (NFS).

Eleven PD patients filled this final version of the scale in the OFF and ON conditions during a levodopa challenge. There were eight men and three women, with a motor MDS‐UPDRS mean score of 32.6/132 and 11.6/132 in the OFF and the ON conditions, respectively. Although we did not quantify their impressions captured through the ad hoc questionnaire, both patients and clinicians found the scale easy to fill and use.

Discussion

We have constructed a new self‐applied assessment tool, the NFS, aimed at promptly scoring the neuropsychiatric fluctuations in PD patients. This NFS is composed of 20 items, ten measuring the ON neuropsychological symptoms and ten measuring the OFF neuropsychological symptoms. It provides two sub‐scores with a maximal total score of 30 each. Like all self‐applied assessments, the NFS is appropriate only for non‐demented PD patients able to fill in the scale.

The strength of this new scale is to fill a current relevant gap in clinic and research, providing patients with the most adapted words to describe subjective neuropsychiatric changes that they may not even be aware of. This wording does not come from a theoretical construct, but stems from a large series of 102 PD patients with motor fluctuations who used six different neuropsychiatric tools in the ON and OFF medication conditions (i.e. a total of 106 different neuropsychiatric items). Only the most representative ones were selected to quantify two opposite neuropsychological conditions. The aim of the NFS is not to make a psychiatric diagnosis, but to detect and quantify subjectively felt changes in neuropsychological conditions. Indeed, these subjective feelings are symptoms belonging to PD and related to anti‐PD medications (medication withdrawal in the OFF medication condition and medication psychotropic effect in the ON medication condition).

Neuropsychiatric fluctuations are frequent and bothersome in PD patients. For example, the presence of anxiety correlates with the score of disability generated by NMF,3 and like other mood fluctuations, anxiety can have more impact than motor fluctuations.29 Neuropsychiatric fluctuations are often under‐recognized by the patients, their relatives, and clinicians, with potential harmful consequences. Neuropsychiatric fluctuations might herald or even hasten dopaminergic medication addiction. Patients might increase their dopaminergic treatment in order to have a “super‐ON,”30 in order to avoid the neuropsychiatric OFF, which would reinforce the compulsory component of medication seeking. Surprisingly, available tools to assess NMF are nonspecific for neuropsychiatric symptoms, and assess motor, sensory, dysautonomic, and neuropsychiatric dimensions all together. Moreover, the existing tools have several important limitations since they are retrospective, in the format of questionnaires or semi structured‐interviews.6, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19

Our scale is designed to specifically identify and quantify neuropsychiatric fluctuations during the so‐called motor fluctuations. Therefore, it is a scale to be used in acute settings. To our knowledge, it is the first scale with this purpose.

Our scale has been developed using self‐administered questionnaires. It has been shown that self‐administered questionnaires are more sensitive to detect both motor and non‐motor fluctuations rather than semi‐structured questionnaire,6 probably because it can be difficult for the patient to separate and report several symptoms that occur at the same point time. Moreover, this scale not only allows the detection of neuropsychiatric fluctuations, but also assesses their severity. To maximize the detection of neuropsychiatric fluctuations, the scale should be filled by the patients in both the OFF and ON conditions. There are indeed patients, who present with a severe neuropsychiatric ON or OFF state not systematically associated with such severe motor OFF condition or dyskinesia. As already mentioned, recognizing neuropsychiatric fluctuations are crucial for optimizing their management. This scale can also help to differentiate neuropsychiatric phenotypes of patients, such as patients with predominant OFF, patients with predominant ON, and patients with both ON and OFF neuropsychiatric fluctuations. Differentiating the neuropsychiatric fluctuations profile is crucial for tailoring the treatment.

This scale may also prove to be sensitive to capture a chronic neuropsychiatric state, such hypodopaminergic or hyperdopaminergic syndromes, in patients who do not present with neuropsychiatric fluctuations. The same holds true for motor symptoms as measured by the UPDRS motor subscale that can be used once in non‐fluctuating patients or repeated during a levodopa challenge. Patients with a prevailing hypodopaminergic syndrome (anxiety, depression, apathy) would thus score similarly to patients with OFF neuropsychiatric fluctuations in the OFF condition, whereas patients with hyperdopaminergic behaviors (addictions, creativity) would score similarly to patients with ON neuropsychiatric fluctuations in the ON condition. Future studies should test whether such use is meaningful in clinical practice.

The interest of this scale goes beyond the diagnostic use, since it could be used as an evaluation tool in patient's and caregivers educations programs, which are demonstrated to be effective in improving quality of life.31 PD educational programs focus for now on communication, stress management, anxiety, and depression management when aiming at psychological aspects of the disease without linking this aspects to potential neuropsychiatric non‐motor fluctuations.31, 32 The interest of the scale also extends to the research field. For instance, when performing functional imaging or electrophysiological studies using a behavioral paradigm the scale could allow acute assessment of the neuropsychiatric state of the patient in that precise moment, since emotional state deeply influence cognitive performances.33

Conclusions

We have described the construction of a tool aiming at identifying and quantifying neuropsychiatric fluctuations in parallel to motor fluctuations, filling a gap in clinics and research. The scale facilitates the self‐assessment of the neuropsychiatric state of PD patients using wording adapted to express their feelings during the OFF and ON conditions. The NFS has been developed to be used in acute settings, allowing the determination of the neuropsychological state of the patient during a given situation. This new tool will require a validation study before being widely used in clinical practice or research.

Author Roles

1. Research Project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; 2. Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; 3. Manuscript Preparation: A. Writing the First Draft, B. Review and Critique.

E.S: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2C, 3A, 3B

P.K: 1A, 1B, 2C, 3B

A.C: 1A, 1B, 2C, 3B

H.K: 3B

A.B: 1C, 3B

E.L: 1C, 3B

P.P: 1A, 1B, 2C

V.F: 1C, 3B

S.T: 3B

E.M: 3A, 3B

P.MM: 1A, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3B

Disclosures

Ethical Compliance Statement: We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines. The authors confirm that the approval of an institutional review board was not required for this work

Funding Sources and Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to this work. This project received grants from Lundbeck.

Financial Disclosures for the previous 12 months: E. Schmitt has received honoraria from the Movement Disorder Society and Elivie Santé. P. Krack has received research grants from Orkyn, Novartis, UCB, Medtronic, LVL, Boston Scientific, St Jude, France Parkinson, Fondation Louis Jeantet, Carigest Foundation, and Swiss National Science Foundation, and honoraria for lecturing or consultation from the Movement Disorder Society, Lundbeck, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, UCB, Medtronic, Orkyn, Abbott, Orion, TEVA, and Boston Scientific. A. Castrioto has received honoraria from the Movement Disorder Society.

A. Bichon has received honoraria from the Movement Disorder Society. S. Thobois has received honoraria from Medtronic, Novartis, UCB, Teva and Aguettant. E. Moro has received honoraria from Medtronic and the Movement Disorders Society. She has also received research grant support from Amadys.

Relevant disclosures and conflicts of interest are listed at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Parkinson J. An essay on the shaking palsy. 1817. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2002;14(2):223–236; discussion 222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Garcia‐Ruiz PJ, Chaudhuri KR, Martinez‐Martin P. Non‐motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease A review…from the past. J Neurol Sci 2014;15;338(1–2):30–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Witjas T, Kaphan E, Azulay JP, et al. Nonmotor fluctuations in Parkinson's disease: frequent and disabling. Neurology 2002;59(3):408–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schrag A, Jahanshahi M, Quinn N. What contributes to quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;69(3):308–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Raudino F. Non motor off in Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurol Scand 2001;104(5):312–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stacy M, Bowron A, Guttman M, et al. Identification of motor and nonmotor wearing‐off in Parkinson's disease: comparison of a patient questionnaire versus a clinician assessment. Mov Disord Off J Mov Disord Soc 2005;20(6):726–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seki M, Takahashi K, Uematsu D, et al. Clinical features and varieties of non‐motor fluctuations in Parkinson's disease: a Japanese multicenter study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2013;19(1):104–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Storch A, Schneider CB, Wolz M, et al. Nonmotor fluctuations in Parkinson disease: severity and correlation with motor complications. Neurology 2013;80(9):800–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Skorvanek M, Gdovinova Z, Rosenberger J, et al. The associations between fatigue, apathy, and depression in Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurol Scand 2015;131(2):80–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brown RM, Lawrence AJ. Compulsive use of dopamine replacement therapy in Parkinson's disease: insights into the neurobiology of addiction. Addict Abingdon Engl 2012;107(2):250–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Delpont B, Lhommée E, Klinger H, et al. Psychostimulant effect of dopaminergic treatment and addictions in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord Off J Mov Disord Soc 2017;32(11):1566–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hung SW, Adeli GM, Arenovich T, Fox SH, Lang AE. Patient perception of dyskinesia in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010;81(10):1112–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goetz CG, Tilley BC, Shaftman SR, et al. Movement Disorder Society‐sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (MDS‐UPDRS): Scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov Disord 2008;23(15):2129–2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Martinez‐Martin P, Hernandez B, Q10 Study Group . The Q10 questionnaire for detection of wearing‐off phenomena in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2012;18(4):382–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Martinez‐Martin P, Tolosa E, Hernandez B, Badia X, ValidQUICK Study Group . Validation of the “QUICK” questionnaire—a tool for diagnosis of “wearing‐off” in patients with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord Off J Mov Disord Soc 2008;23(6):830–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stacy MA, Murphy JM, Greeley DR, et al. The sensitivity and specificity of the 9‐item wearing‐off questionnaire. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2008;14(3):205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kleiner‐Fisman G, Martine R, Lang AE, Stern MB. Development of a non‐motor fluctuation assessment instrument for Parkinson disease. Park Dis 2011:292719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ardouin C, Chéreau I, Llorca P‐M, et al. Assessment of hyper‐ and hypodopaminergic behaviors in Parkinson's disease. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2009;165(11):845–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rieu I, Martinez‐Martin P, Pereira B, et al. International validation of a behavioral scale in Parkinson's disease without dementia. Mov Disord Off J Mov Disord Soc 2015;30(5):705–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thobois S, Lhommée E, Klinger H, et al. Parkinsonian apathy responds to dopaminergic stimulation of D2/D3 receptors with piribedil. Brain J Neurol 2013;136(Pt 5):1568–7157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories ‐IA and ‐II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess 1996;67(3):588–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988;56(6):893–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Starkstein SE, Mayberg HS, Preziosi TJ, Andrezejewski P, Leiguarda R, Robinson RG. Reliability, validity, and clinical correlates of apathy in Parkinson's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1992;4(2):134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Norris H. The action of sedatives on brain stem oculomotor systems in man. Neuropharmacology. 1971;10(21):181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Haertzen CA. Development of scales based on patterns of drug effects, using the addiction Research Center Inventory (ARCI). Psychol Rep 1966;18(1):163–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci 1978;133:429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch Psychol 1932;22(140):5–55. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Albanese A, Bonuccelli U, Brefel C, et al. Consensus statement on the role of acute dopaminergic challenge in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord Off J Mov Disord Soc 2001;16(2):197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Riley DE, Lang AE. The spectrum of levodopa‐related fluctuations in Parkinson's disease. Neurology 1993;43(8):1459–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Delpont Benoit, Lhommée E, Helene Klinger, et al. Psychostimulant effect of antiparkinsonian drugs drives both behavioural addiction and abuse of médication. Brain J Neurol 2017. 10.1002/mds.27101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. A'Campo LEI, Spliethoff‐Kamminga NGA, Roos R a. C. An evaluation of the patient education programme for Parkinson's disease in clinical practice. Int J Clin Pract 2011;65(11):1173–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ory Magne F, Arcari C, Canivet C, et al. A therapeutic educational program in Parkinson's disease: ETPARK. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2014;170(2):128–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Eysenck MW, Derakshan N, Santos R, Calvo MG. Anxiety and cognitive performance: attentional control theory. Emot Wash DC 2007;7(2):336–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]