Abstract

Background

Two methods for testing inducibility of atrial fibrillation (AF)—atrial pacing and isoproterenol infusion—have been proposed to determine the endpoint of catheter ablation. However, the utility of the combination for testing electrophysiological inducibility (EPI) and pharmacological inducibility (PHI) is unclear.

Methods

After pulmonary vein isolation (PVI), inducibility of atrial tachyarrhythmia was assessed with the dual methods in 291 consecutive patients with AF (65% paroxysmal) undergoing initial catheter ablation.

Results

The incidence of EPI was significantly higher in patients with persistent AF than paroxysmal AF (32.0% vs 11.7%, respectively, P < .001). The incidence of PHI was not significantly different between the two groups (25.2% vs 26.1%, respectively, P = .87). There was no significant difference in AF recurrence according to inducibility in paroxysmal AF. In persistent AF, however, patients achieving neither EPI nor PHI under PVI‐only strategy had significantly lower rates of AF recurrence than those achieving either EPI or PHI and consequently requiring additional ablation for inducible atrial tachyarrhythmia (68.5% vs 49.0%, respectively; log‐rank test, P = .022). In persistent AF, multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that achieving neither EPI nor PHI was a negative independent predictor of AF recurrence (HR 0.492, 95% CI 0.254‐0.916, P = .026).

Conclusions

Achieving neither EPI nor PHI following PVI was associated with favorable outcome in patients with persistent AF. The combination of tests may discriminate patients responsive to the PVI‐only strategy. Further selective approaches are necessary to improve outcome for inducible atrial tachyarrhythmia in patients with persistent AF.

Keywords: atrial pacing, catheter ablation, inducibility, isoproterenol, persistent atrial fibrillation

1. INTRODUCTION

Although pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) is a well‐established treatment for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF), this strategy has been reported to be insufficient for treating persistent AF, with suboptimal success rate.1 This led to the development of the adjunctive ablation strategies to target nonpulmonary vein (PV) triggers2, 3 and atrial substrate for perpetuating AF, including ablation of complex fractionated atrial electrograms (CFAE)4 and linear lesion creation in the left atrium (LA).5, 6 However, it remains unclear how to select patients requiring each adjunctive ablation strategy beyond PVI.

Two different methods, rapid atrial pacing7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and high‐dose isoproterenol infusion,13, 14 have been proposed to test the inducibility of atrial tachyarrhythmia to determine the endpoint of catheter ablation after PVI. These alternate methods for testing inducibility may evaluate separate mechanisms for the development of AF. While rapid atrial pacing may test the arrhythmogenic substrate, isoproterenol may be useful to provoke potential non‐PV triggers of AF. Previous studies showed that noninducibility with each method was useful to evaluate the prognostic value after AF ablation in paroxysmal AF.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 However, the clinical role of a combination of the dual inducibility method at the end of the ablation procedure is still unclear. This study was performed to assess the incidence of atrial tachyarrhythmia inducibility with the dual methods following PVI and the impact of each electrophysiological and pharmacological inducibility on the long‐term outcome in patients with paroxysmal and persistent AF.

2. METHODS

2.1. Subjects

A total of 297 consecutive patients undergoing initial catheter ablation for drug‐refractory AF between October 2011 and February 2014 in the Cardiovascular Institute were identified. Paroxysmal AF was defined as AF that self‐terminated in 7 days or less, while persistent AF was defined as continuous AF that lasted for more than 7 days. After excluding six patients for whom inducibility of atrial tachyarrhythmia was not sequentially assessed with the dual methods, 291 patients were included in the analysis. All patients provided written informed consent prior to the procedure, and the Institutional Review Board of the Cardiovascular Institute approved the study (Date of IRB approval; January 28, 2016; Approval number, 285).

2.2. Procedural details

All patients had anticoagulation therapy for more than 3 weeks before ablation and underwent transesophageal echocardiography to exclude atrial thrombus within 3 days before ablation. Oral anticoagulant drugs except warfarin were interpreted on the morning of the procedure. All antiarrhythmic drugs (AAD) were discontinued for at least five half‐lives, and no patients received any oral amiodarone therapy before the procedure. All procedures were performed under deep sedation using fentanyl and continuous infusion of propofol. A temperature probe (Sensitherm; St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN) was placed at the mid‐portion of the esophagus through the nose, and esophageal temperature was monitored continuously during the procedure. Vascular accesses were obtained through the right femoral vein and the right jugular vein. After vascular access, activated clotting time (ACT) was kept at 300‐350 seconds by a bolus of 5000 IU heparin and continuous administration of intravenous heparin. A 16‐polar 2‐site catheter—6‐polar for the right atrium (RA) and 10‐polar for the coronary sinus (CS) (St. Jude Medical)—was placed in the CS via the right jugular vein. The left atrium (LA) was accessed by single transseptal puncture or via the patent foramen ovale. For pulmonary vein (PV) mapping, two 20‐polar, circular mapping catheters (Lasso; Biosense Webster, Diamond Bar, CA, or Libero; Japan Lifeline, Tokyo, Japan) were placed in the ipsilateral PVs via two long sheaths (8 F or 8.5 F, Swartz Braided SL0 curve; St. Jude Medical). A 3.5 mm tip irrigated ablation catheter (Navistar ThermoCool; Biosense Webster, or CoolPath Duo; St. Jude Medical) was advanced into the LA through the gap of the atrial septum between two circular mapping catheters. PVI was performed by circumferential applications of radiofrequency energy at each PV antrum with a 3‐dimensional mapping system (CARTO XP/CARTO 3; Biosense Webster, or EnSite NavX; St. Jude Medical). Radiofrequency (RF) energy was delivered at a maximum power of 25 W, with a target temperature of 43°C. Direct current cardioversion (DCCV) was performed if AF was still present after PVI. The endpoint of PVI was elimination of all PV potentials and demonstration of exit block by pacing from circular mapping catheters. The dormant conduction provoked by administration of adenosine triphosphate (ATP, 20 mg) was also ablated at the initial documentation of PVI and the end of the procedure.

Following PVI, linear ablation at the cavotricuspid isthmus (CTI) was performed in all patients. RF energy was delivered at a maximum power of 30 W, with a target temperature of 43°C. A 20‐pole Halo catheter was placed along the tricuspid annulus to assess the bidirectional conduction block using a differential pacing method.

2.3. Inducibility tests and adjunctive ablation strategy

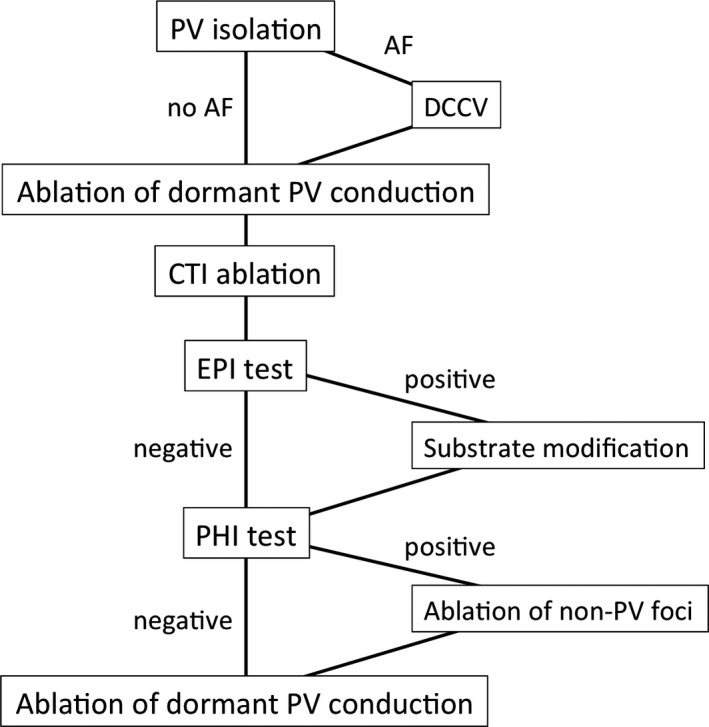

Figure 1 shows the procedural flowchart in this study. After completion of PVI and CTI ablation, the inducibility of atrial tachyarrhythmia was assessed sequentially with two methods. First, electrophysiological inducibility (EPI) was assessed by rapid atrial pacing, which was delivered from proximal CS for 5 seconds, starting at a pacing cycle length of 250 ms, and reducing in steps of 10 ms to a minimum of 180 ms at 3 seconds intervals, without administration of isoproterenol. Positive EPI was defined as sustained AF/AT for at least 5 minutes. Additional ablation targeting complex fractionated atrial electrograms (CFAE) were performed if sustained AF lasting more than 5 minutes was induced by EPI test. CFAE was defined as low amplitude multiple potential atrial signals with a very short cycle length (<120 ms).4 The atrial septum, inferior LA, ostium of the left appendage, CS, and right atrium were systematically mapped and ablated with the endpoint of AF termination or elimination of CFAE in these target lesions. DCCV was performed if AF termination was not achieved within 30 applications for CFAE. If AF was converted into organized atrial tachycardia (AT) during CFAE ablation, AT was mapped and ablated under 3D mapping system guidance.

Figure 1.

Procedural flowchart. PV, pulmonary vein; AF, atrial fibrillation; DCCV, direct current cardioversion; CTI, cavotricuspid isthmus; EPI, electrophysiological inducibility; PHI, pharmacological inducibility

Following EPI test, the pharmacological inducibility (PHI) was assessed using isoproterenol. Isoproterenol was rapidly infused through the jugular vein at escalating doses of 4, 8, 12, and 16 μg at 2 minute intervals. Isoproterenol infusion was discontinued upon induction of AF or repetitive non‐PV ectopies, a decrease in systolic blood pressure to <70 mm Hg, or ST depression <1 mm on the electrocardiogram. Positive PHI was defined as AF initiation or repetitive non‐PV ectopic beats (>10 beats/minute). The origins of non‐PV foci were mapped using a 16‐polar CS‐RA catheter, 20‐pole circular catheter placed in the LA septum, and 20‐pole Halo catheter located along the tricuspid annulus. These catheters were located in the stable position to avoid iatrogenic ectopic beats. If ectopic beats originating from the superior vena cava (SVC) were identified by the 16‐polar CS‐RA catheter, SVC isolation was added under the guidance of the 20‐polar circular mapping catheter. Focal ablation at the earliest ectopic site was added with the endpoint of elimination of non‐PV triggers or repetitive non‐PV ectopic beats with the same induction protocol.

2.4. Follow‐up

All patients were followed up at our outpatient clinic every month for 3 months after the procedure and thereafter every 2‐3 months for 9 months after the procedure. Oral anticoagulants were maintained for at least 3 months after the procedure. AAD except beta‐blockers were continued for 1‐2 months and then discontinued if the patients had no AF/AT recurrence. AF/AT recurrence was defined as any episode of atrial tachyarrhythmia lasting >30 seconds after 3 months of the blanking period without AAD. The recurrence of AF/AT was evaluated based on clinical symptoms and ECG, including 12‐lead ECG at every visit, 24 hour Holter ECG at 3 months and 12 months, and 30 seconds ECG recorded with a mobile event recorder at a minimum 1‐2 times a day for 3‐6 months after the procedure.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Continuous data are given as mean ± standard deviation. Differences in continuous and categorical variables were evaluated by unpaired Student's t test and chi‐square test, respectively. Cox regression analyses with univariate and multivariate models were performed to evaluate the influences of AF inducibility and other covariates on AF/AT recurrence. Kaplan‐Meier analysis was used to estimate the cumulative rate of freedom from recurrent AF/AT, and the differences between groups were tested for significance by the log‐rank test. All reported P‐values are two‐sided, and P < .05 was taken to indicate statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patient characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1: 188 (64.6%) patients with paroxysmal AF and 103 (35.4%) patients with persistent AF, mean age 59.8 ± 10.7 years old, 42 female (14.4%), mean CHADS2 score 0.45 ± 0.64, mean CHA2DS2VASc score 0.96 ± 1.02, and mean LA diameter on echocardiogram 39.9 ± 6.1 mm. Patients with persistent AF had significantly larger LA diameter (43.3 ± 5.2 mm vs 39.7 ± 5.6 mm, respectively, P < .001) and lower left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (61.6% ± 8.8% vs 66.1% ± 7.0%, P < .001) than patients with paroxysmal AF.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients

| Total (n = 291) | Paroxysmal AF (n = 188) | Persistent AF (n = 103) | * P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 59.8 ± 10.7 | 59.7 ± 10.9 | 59.4 ± 10.3 | .802 |

| Female | 42 (14.4) | 26 (13.8) | 16 (15.5) | .744 |

| Hypertension | 96 (33.0) | 56 (29.8) | 40 (38.8) | .084 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 15 (5.2) | 8 (4.3) | 7 (6.8) | .322 |

| CHADS2 | 0.45 ± 0.64 | 0.39 ± 0.59 | 0.53 ± 0.66 | .079 |

| CHA2DS2VASc | 0.96 ± 1.022 | 0.92 ± 0.99 | 1.01 ± 1.05 | .473 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 7 | 6 | 1 | |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 5 | 3 | 2 | |

| Valvular disease | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Tachycardia‐induced cardiomyopathy | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Atrial septal defect | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| LA diameter, mm | 39.9 ± 6.1 | 39.7 ± 5.6 | 43.3 ± 5.2 | <.001 |

| LVEF, % | 64.6 ± 7.9 | 66.1 ± 7.0 | 61.6 ± 8.8 | <.001 |

| AF duration, months | NA | NA | 13.9 ± 20.8 | |

| AF duration ≥12 mo | NA | NA | 41 (39.8) |

AF = atrial fibrillation; CHADS2 = congestive heart failure, age over 75 years, diabetes mellitus, previous stroke/transit ischemic attack; CHA2DS2VASc = congestive heart failure, age over 75 years old, diabetes mellitus, previous stroke/transit ischemic attack, vascular disease, age 65‐74 years, sex; LA = left atrium; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; NA = not applicable.

Values are expressed as mean ± SD or as n (%). *P‐value is comparing paroxysmal AF and persistent AF.

3.2. Results of inducibility tests and ablation procedures

PVI and CTI ablation were performed successfully in all patients. After PVI, sustained AF was terminated by DCCV in 113 patients: 19 of 188 (10.1%) paroxysmal AF patients and 94 of 103 (91.2%) persistent AF patients. The results of inducibility tests and procedural results are summarized in Table 2. EPI and PHI were observed in 55 (18.9%) and 75 (25.8%) of 291 patients, respectively. The incidence of EPI was significantly higher in patients with persistent AF than paroxysmal AF (32.0% vs 11.7%, respectively, P < .001). There was no significant difference in the incidence of PHI between paroxysmal and persistent AF (26.1% vs 25.2%, respectively, P = .87). CFAE ablation and linear ablation in LA were added more frequently in patients with persistent AF compared with paroxysmal AF (32.0% vs 11.7%, respectively, P < .001 and 9.7% vs 2.1%, respectively, P = .004, respectively). Linear ablation lesions connecting the left superior PV with the anterior mitral annulus were added to eliminate perimitral atrial flutter in 14 patients, and the bidirectional conduction block of the linear lesions was achieved in 12 (85.7%) of these patients. After substrate modification, sustained AF or AT was terminated by DCCV in 6 of 22 (27.2%) patients with paroxysmal AF, and 23 of 33 (69.9%) patients with persistent AF. Following EPI test with or without substrate modification, PHI test was performed. AF was induced in three (1.0%) patients, and 72 (24.7%) patients had repetitive non‐PV ectopic beats without induction of AF during isoproterenol infusion. Of the 75 patients with 76 non‐PV foci, 32 were from SVC, 12 from the atrial septum, four from the inferior LA wall, three each from the anterior LA wall and the posterior LA wall, two from the lateral LA wall, seven from the coronary sinus, and six from the crista terminalis. The localization could not be identified for seven multifocal non‐PV ectopic beats and were classified as failure to ablate. (three paroxysmal AF patients and four persistent AF patients). Non‐PV/SVC foci were more frequently observed in patients with persistent AF than paroxysmal AF (20.4% vs 13.3%, respectively, P = .113). Total procedure time (139.1 ± 37.9 minutes vs 159.9 ± 44.7 minutes, P < .001), fluoroscopic time (23.5 ± 7.1 minutes vs 26.3 ± 7.8 minutes, P = .02), and ablation time (46.9 ± 18.1 minutes vs 54.7 ± 21.6 minutes, P = .01) were significantly shorter in patients with paroxysmal AF than persistent AF.

Table 2.

Comparison of the results of inducibility tests and ablation procedure between paroxysmal AF and persistent AF

| Total (n = 291) | Paroxysmal AF (n = 188) | Persistent AF (n = 103) | * P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Results of inducibility tests | ||||

| EPI (+) | 55 (18.9) | 22 (11.7) | 33 (32.0) | <.001 |

| PHI (+) | 75 (25.8) | 49 (26.1) | 26 (25.2) | .87 |

| EPI (−), PHI (−) | 179 (61.5) | 125 (66.5) | 54 (52.4) | .01 |

| EPI (+), PHI (−) | 37 (12.7) | 14 (7.4) | 23 (22.3) | |

| EPI (−), PHI (+) | 58 (19.9) | 41 (21.8) | 17 (16.5) | |

| EPI (+), PHI (+) | 18 (6.1) | 8 (4.3) | 10 (9.7) | |

| Procedural results | ||||

| Total procedure time, min | 146.5 ± 42.7 | 139.1 ± 37.9 | 159.9 ± 44.7 | <.001 |

| Fluoroscopic time, min | 24.5 ±7.5 | 23.5 ± 7.1 | 26.3 ±7.8 | .002 |

| Ablation time, min | 49.7 ± 19.7 | 46.9 ± 18.1 | 54.7 ± 21.6 | .001 |

| Additional ablation | ||||

| CFAE ablation | 55 (18.9) | 22 (11.7) | 33 (32.0) | <.001 |

| Liner ablation in LA | 14 (4.8) | 4 (2.1) | 10 (9.7) | .004 |

| SVC isolation | 32 (11.0) | 24 (12.8) | 8 (7.8) | .192 |

| Ablation of non‐PV/SVC foci | 46 (15.8) | 25 (13.3) | 21 (20.4) | .113 |

CFAE = complex fractionated atrial electrogram; EPI = electrophysiological inducibility; LA = left atrium; PHI = pharmacological inducibility; SVC = superior vena cava; PV = pulmonary vein.

Values are expressed as mean ± SD or as n (%). *P‐value is comparing paroxysmal AF and persistent AF.

3.3. Follow‐up

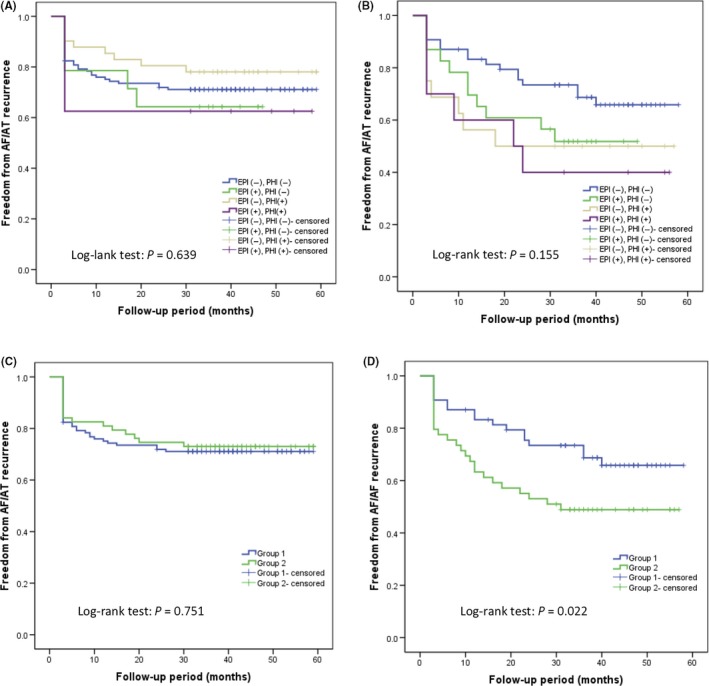

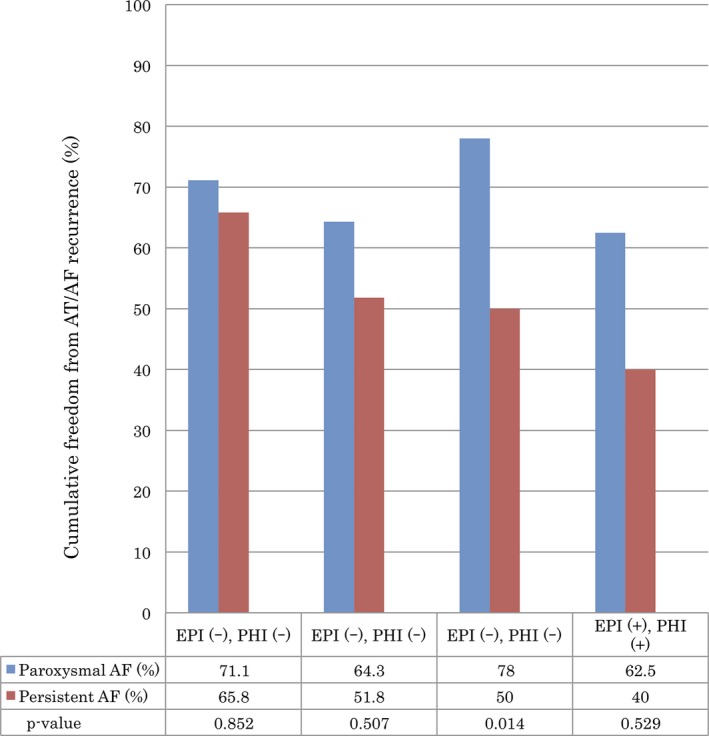

During a mean follow‐up period of 42.5 ± 9.3 months, there was a significant difference in AF/AT recurrence‐free rate without AAD between paroxysmal and persistent AF (71.8% vs 59.2%, respectively, log‐rank test, P = .043). Figure 2A and 2B shows Kaplan‐Meier curves of the AF/AT recurrence‐free rate among the four groups divided by the results of each test in patients with paroxysmal and persistent AF, respectively. Although there was no significant trend for AF/AT recurrence among the four groups in patients with paroxysmal AF (log‐rank test, P = .639), the patients with neither EPI nor PHI showed a trend favoring long‐term outcome in persistent AF in comparison with other groups (log‐rank test, P = .155). Figure 3 shows a comparison of cumulative freedom from AT/AF recurrence according to the results of inducibility tests between paroxysmal and persistent AF. The AF/AT recurrence‐free rate in patients with neither EPI nor PHI was comparable between paroxysmal and persistent AF (71.1% vs 65.8%, respectively, log‐rank test, P = .852). In comparison of the patients with negative EPI and positive PHI, paroxysmal AF had a significantly higher AF/AT recurrence‐free rate than persistent AF (78.0% vs 50.0%, respectively, log‐rank test, P = .014).

Figure 2.

Kaplan‐Meier estimate curve comparing freedom from AF/AT recurrence according to the results of inducibility tests after a single procedure. A, Paroxysmal AF. B, Persistent AF. C, Paroxysmal AF. D, Persistent AF. AF, atrial fibrillation; AT, atrial tachycardia; EPI, electrophysiological inducibility; PHI, pharmacological inducibility; Group 1, neither electrophysiological inducibility nor pharmacological inducibility after pulmonary vein isolation; Group 2, either electrophysiological inducibility or pharmacological inducibility, or both after pulmonary vein isolation

Figure 3.

Comparison of cumulative freedom from AT/AF recurrence according to the results of inducibility tests using the log‐rank test between paroxysmal and persistent AF. AF, atrial fibrillation; AT, atrial tachycardia; EPI, electrophysiological inducibility; PHI, pharmacological inducibility

3.4. Clinical Impact of neither electrophysiological nor pharmacological inducibility

The 291 patients were reassessed and divided into two groups according to the results of inducibility tests as follows: Group 1 (179 patients), inducible atrial arrhythmias with neither EPI nor PHI test; Group 2 (112 patients), inducible any atrial arrhythmias with both or either test.

A comparison of patient characteristics and procedural results between Group 1 and Group 2 is shown in Table 3. There were no significant differences in age, gender, LA diameter, or LVEF between Group 1 and Group 2, while diabetes mellitus (2.8% vs 8.9%, respectively, P = .021) and paroxysmal AF (69.8% vs 56.3%, respectively, P = .018) showed significant differences between the two groups. In the patients with persistent AF, mean LA diameter was significantly larger (44.4 ± 5.7 mm vs 42.2 ± 4.6 mm, respectively, P = .039) and diabetes mellitus was more frequent (12.4% vs 1.9%, respectively, P = .036) in Group 2 than in Group 1. Total procedure time (132.6 ± 32.7 minutes vs 168.2 ± 47.8 minutes, respectively, P < .001), fluoroscopic time (22.8 ± 6.9 minutes vs 27.2 ± 7.7 minutes, respectively, P = .02), and ablation time (44.1 ± 14.9 minutes vs 60.9 ± 23.0 minutes, respectively, P < .001) were significantly shorter in Group 1 than in Group 2.

Table 3.

Comparison of patient characteristics and ablation procedure between Group 1 and Group 2

| Total | Paroxysmal AF | Persistent AF | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (n = 179) | Group 2 (n = 112) | P‐value | Group 1 (n = 125) | Group 2 (n = 63) | P‐value | Group 1 (n = 54) | Group 2 (n = 49) | P‐value | |

| Patient characteristics | |||||||||

| Age, y | 59.8 ± 10.3 | 59.3 ± 11.2 | .68 | 60.1 ± 10.1 | 59.0 ± 12.3 | .505 | 59.1 ± 10.8 | 59.7 ± 9.8 | .797 |

| Female | 9 (16.7) | 7 (14.3) | .746 | 18 (14.4) | 8 (12.7) | .75 | 9 (16.7) | 7 (14.3) | .739 |

| Hypertension | 56 (31.3) | 40 (35.7) | .434 | 34 (27.2) | 22 (34.9) | .275 | 22 (40.7) | 18 (36.7) | .677 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (2.8) | 10 (8.9) | .021 | 4 (3.2) | 4 (6.3) | .313 | 1 (1.9) | 6 (12.4) | .036 |

| CHADS2 score | 0.41 ± 0.60 | 0.51 ± 0.67 | .181 | 0.38 ± 0.61 | 0.42 ± 0.58 | .631 | 0.46 ± 0.57 | 0.61 ± 0.75 | .269 |

| CHA2DS2VASc score | 0.92 ± 1.03 | 1.01 ± 0.99 | .45 | 0.92 ± 1.02 | 0.92 ± 0.93 | .997 | 0.91 ± 1.05 | 1.12 ± 1.05 | .303 |

| LA diameter, mm | 39.4 ± 5.6 | 40.3 ± 6.6 | .196 | 38.2 ± 5.6 | 37.2 ± 5.5 | .263 | 42.2 ± 4.6 | 44.4 ± 5.7 | .039 |

| LAD ≥40 mm | 89 (49.7) | 62 (55.4) | .349 | 50 (40) | 21 (33.3) | .373 | 39 (72.2) | 41 (83.3) | .163 |

| LVEF, % | 64.9 ± 7.8 | 63.9 ± 7.8 | .28 | 66.0 ± 7.2 | 66.4 ± 6.5 | .699 | 62.5 ± 9.3 | 60.7 ± 8.4 | .298 |

| Paroxysmal AF | 125 (69.8) | 63 (56.3) | .018 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| AF duration, mo | NA | NA | NA | NA | 11.8 ± 11.5 | 17.4 ± 28.4 | .212 | ||

| AF duration ≥12 mo | NA | NA | NA | NA | 24 (44.4) | 17 (34.7) | .313 | ||

| Procedural results | |||||||||

| Procedure time, min | 132.6 ± 32.7 | 168.2 ± 47.8 | <.001 | 129.3 ± 28.6 | 158.6 ± 50.6 | <.001 | 141.1 ± 39.3 | 180.6 ± 41.3 | <.001 |

| Fluoroscopic time, min | 22.8 ± 6.9 | 27.2 ± 7.7 | .002 | 22.4 ± 6.3 | 25.8 ± 8.2 | .002 | 23.3 ± 8.1 | 28.9 ±6.8 | .001 |

| Ablation time, min | 44.1 ± 14.9 | 60.9 ± 23.0 | <.001 | 43.7 ± 14.3 | 55.3 ± 22.8 | .001 | 44.9 ± 16.2 | 65.5 ± 21.7 | <.001 |

AF = atrial fibrillation; CHADS2 = congestive heart failure, age over 75 years, diabetes mellitus, previous stroke/transit ischemic attack; CHA2DS2VASc = congestive heart failure, age over 75 years old, diabetes mellitus, previous stroke/transit ischemic attack, vascular disease, age 65‐74 years, sex; LA = left atrium; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; NA = not applicable.

Values are expressed as mean ± SD or as n (%).

After the single ablation procedure, although there were no significant differences in AF/AT recurrence‐free rate between Group 1 and Group 2 in paroxysmal AF (71.2% vs 73.0%, respectively, log‐rank test, P = .751; Figure 2C), in the persistent AF, Group 1 had a significantly higher AF/AT recurrence‐free rate than Group 2 (68.5% vs 49.0%, respectively, log‐rank test, P = .022; Figure 2D).

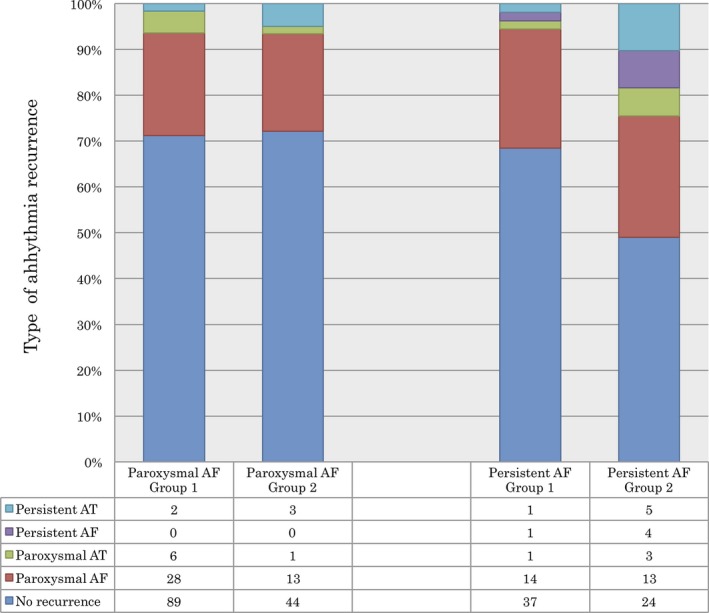

Figure 4 shows a comparison of the type of clinical arrhythmia recurrence between Group 1 and Group 2. In the patients with persistent AF, paroxysmal AF was the most common type of recurrent arrhythmia in Group 1 (25.9%) and Group 2 (26.5%). The recurrences as persistent AF and persistent AT were observed less frequently in Group 1 than in Group 2 after the single procedure for persistent AF (1.9% vs 6.1% and 1.9% vs 8.2%, respectively, P = .09).

Figure 4.

Comparison of the type of arrhythmia recurrence between Group 1 and Group 2. AF, atrial fibrillation; AT, atrial tachycardia

Table 4 shows the hazard ratios of clinical parameters on AF/AT recurrence in patients with persistent AF by Cox regression analysis. Age over >60 years old, female sex, hypertension, diabetes, CHADS2 score, and LAD >40 mm were not associated with AF/AT recurrence. Neither EPI nor PHI after PVI was significantly associated with a lower cumulative risk of AF/AT recurrence (HR 0.516, 95% CI 0.278‐0.958, P = .036) in univariate analysis. In multivariate stepwise analysis, neither EPI nor PHI was an independent predictor of AF/AT recurrence (HR 0.492, 95% CI 0.254‐0.916, P = .026).

Table 4.

Predictor of AF/AT recurrence in patients with persistent AF

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P‐value | HR | 95% CI | P‐value | |

| Age ≥60 y | 0.857 | 0.468‐1.571 | .857 | |||

| Female | 1.847 | 0.907‐3.759 | .091 | 1.974 | 0.966‐4.035 | .062 |

| Hypertension | 1.288 | 0.687‐2.423 | .433 | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 3.322 | 0.457‐24.162 | .236 | |||

| CHADS2 | 0.781 | 0.488‐1.249 | .302 | |||

| LA diameter ≥40 mm | 1.013 | 0.485‐2.117 | .972 | |||

| AF duration ≥12 mo | 1.34 | 0.729‐2.463 | .345 | |||

| Neither EPI nor PHI | 0.516 | 0.278‐0.958 | .036 | 0.492 | 0.254‐0.916 | .026 |

AF = atrial fibrillation; AT, atrial tachycardia; CHADS2 = congestive heart failure, age over 75 years, diabetes mellitus, previous stroke/transit ischemic attack; EPI = electrophysiological inducibility; LA = left atrium; PHI = pharmacological inducibility.

3.5. Complications

One case of pericardial effusion requiring pericardiocentesis seen after the ablation procedure occurred in Group 2 of persistent AF. There were no cases of symptomatic stroke, symptomatic PV stenosis, or atrioesophageal fistula in this study.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Main findings

The present study was performed to examine the impacts of electrophysiological and pharmacological inducibility following PVI on the long‐term outcome of the initial ablation procedure for paroxysmal and persistent AF. Although we found no significant correlations of electrophysiological and pharmacological inducibility with long‐term outcome in paroxysmal AF, neither electrophysiological nor pharmacological inducibility was identified as a significant predictor of favorable long‐term outcome in multivariate analysis of persistent AF. In persistent AF, if atrial tachyarrhythmia could not be induced with the dual methods following PVI, the independent risk of recurrent AF/AT was 2.0‐fold lower than that in patients with either electrophysiological or pharmacological inducibility. In addition, combination of the dual tests may not only discriminate patients responding to the PVI‐only strategy, but also reduce the procedure time and fluoroscopic time with the reduction of unnecessary ablation lesions.

4.2. Electrophysiological and pharmacological inducibility

In the present study, the electrophysiological test was performed to assess atrial vulnerability from rapid atrial stimulation and sustainability for perpetuating AF, and the pharmacological test was used to provoke residual focal source for initiating AF following PVI.

A number of studies have suggested that noninducibility of AF by atrial pacing at the end of AF ablation is associated with lower rates of AF recurrence, especially in patients with paroxysmal AF.7, 8, 9, 10, 12 The incidence of pacing‐induced AF following PVI in the present study was lower than in previous studies (28.2%‐60.0% in paroxysmal7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17 and 42%‐62% in persistent AF9, 11, 16, 17). In addition, the present study showed no significant association between electrophysiological inducibility and long‐term outcome in patients with paroxysmal or persistent AF. Consistent with our findings, previous studies have indicated no prognostic value in pacing‐induced AF following PVI.11, 15, 16, 17

These differences in the prognostic significance of electrophysiological inducibility may be related to (i) the pacing protocol, (ii) the definition of inducible AF, and (iii) the ablation strategy. Our pacing protocol was based on previous studies evaluating the incidence of pacing‐induced AF in patients without clinical AF to decrease the number of nonspecific AF inductions.18, 19 Therefore, our pacing protocol was less aggressive than those used in previous studies evaluating inducibility of AF after ablation.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15 Second, the definition of inducibility of AF also differed widely in the minimum duration of induced AF considered to be significant (10 seconds9 up to 10 minutes10, 15). In the present study, positive electrophysiological inducibility was considered as sustained AF lasting >5 minutes, because a short duration (<5 minutes) of inducible AF was suggested to be a nonspecific phenomenon in clinical practice.11, 19 Moreover, shorter duration of AF is also not suitable for mapping to identify the AF substrate including the location of CFAE or reentrant circuits.

Finally, the ablation strategy for adjunctive ablation lesions following inducibility test was heterogeneous among previous studies.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15 In the present study, limited CFAE ablation without empirical linear ablation lesions in LA was performed as substrate modification for pacing‐induced AF, and the incidence of persistent AT following the initial ablation procedure was low (6.5%) in patients with persistent AF. Consistent with our findings, a previous study suggested that a limited CFAE ablation strategy provides a lower incidence of recurrent macroreentrant AT, and better reverse remodeling of the LA compared with extensive CFAE ablation strategies in the initial ablation procedure for persistent AF.20 Further selective approach for substrate modification is necessary to improve clinical for pacing‐induced AF.

Isoproterenol is most commonly used to provoke non‐PV triggers in patients without spontaneously firing non‐PV triggers.13, 14 Using our protocol, non‐PV triggers inducing AF could be induced in 1.0% of cases, which was lower than in previous studies (11%‐32%14, 21, 22, 23). However, the incidence of non‐PV foci including non‐PV ectopic beats not initiating AF was comparable.21 The difference in rate of pharmacological inducibility of AF may have been related to our protocol of isoproterenol infusion, that is, lower total dosage and shorter infusion time,13, 14 and lack of DCCV of pacing‐induced AF during isoproterenol infusion24 compared with previous studies. In addition, CFAE ablation may have resulted in fortuitous ablation of non‐PV foci, because the sites of the origin of the non‐PV triggers were found to be associated with the location of those of the presence of CFAE.25, 26

Many investigators have reported that non‐PV triggers inducing AF are associated with higher AF recurrence rate,14, 22, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 and ablation of non‐PV triggers added to PVI has been shown to improve the clinical outcome in patients with paroxysmal AF.28, 30, 31 In addition, Elayi et al26 reported that non‐PV ectopic beats not inducing AF were also associated with higher AF recurrence rate. Thus, our approach for ablation strategy of non‐PV foci may contribute to prevention of long‐term outcomes in patients with paroxysmal AF.

In contrast, pharmacological inducibility was strongly associated with AF/AF recurrence in patients with persistent AF in comparison with paroxysmal AF. This difference may be related to (i) the distribution of non‐PV foci and/or (ii) atrial vulnerability. First, the distribution of non‐PV foci may be different between patients with paroxysmal and persistent AF. Consistent with our findings, Santangeli et al23 reported that the distribution of non‐PV foci appeared different in persistent AF, with a higher prevalence of left atrial triggers than in patients with paroxysmal AF. This difference may also explain the progression of left atrial remodeling in patients with persistent AF, as well as the difference in electrophysiological inducibility. Moreover, we could not identify 15.3% of the localization of non‐PV foci in patients with persistent AF. Some investigators have reported that unsuccessful identification of non‐PV triggers is significantly associated with AF recurrence.27, 28 In addition, the recurrence of non‐PV foci was even found in 30% of patients successfully eliminating these triggers.22 Therefore, further studies are necessary to determine the optimal methods for provoking AF triggers and mapping the accurate localization of non‐PV/SVC foci, and an optimal endpoint of ablation for non‐PV/SVC foci.

Second, residual or recurrent triggers after the ablation procedure may have different behaviors between patients with paroxysmal and persistent AF. Due to the definition of AF/AT recurrence, episodes of nonsustained AT/AF <30 seconds may be considered as no recurrence in patients with lower atrial vulnerability, such as paroxysmal AF. In contrast, these triggers may be more likely to become sustained AF in the presence of progressively remodeled atria, such as persistent AF. Our findings suggest that ablation of non‐PV triggers plays an important role in prevention of long‐term outcomes not only in patients with paroxysmal AF, but also in patients with persistent AF.

4.3. Clinical implications of the combination of alternate inducibility tests

To our knowledge, there have been no previous reports regarding the utility of electrophysiological and pharmacological inducibility methods, sequentially combined with atrial pacing and isoproterenol infusion, on long‐term outcome after the initial ablation procedure. The present study demonstrated that the PVI‐only strategy provides favorable outcome in persistent AF patients with neither electrophysiological nor pharmacological inducibility following PVI, and comparable to those with paroxysmal AF. In addition, persistent AF was converted into paroxysmal AF after the single ablation procedure without any substrate modification in 26% of the patients achieving neither electrophysiological nor pharmacological inducibility. These findings suggest that selection of individuals with low atrial vulnerability from rapid atrial stimulation and lack of potential of non‐PV foci may discriminate patients that would show a response to the PVI‐only strategy and avoid unnecessary adjunctive substrate modification in patients not terminating AF with PVI.

Consistent with our findings, the recent meta‐analysis of the PVI‐only strategy in persistent AF patients showed a single‐procedure arrhythmia‐free survival rate of 66.7%.32 A limited ablation strategy of PVI and ablation of only documented non‐PV triggers was also found to provide transformation from persistent to paroxysmal AF,33 and good long‐term AF control with a low frequency of AT in the majority of patients.34

Our data also indicated that patients with more enlarged LA diameter and with diabetes mellitus were more likely to have inducible atrial tachyarrhythmias in persistent AF. These factors were associated with progressive remodeling to maintain perpetuating AF with intraatrial conduction delay and decreased voltage.35, 36

Ablation strategies for persistent AF have not been well established. Our observations suggest that the combination of electrophysiological and pharmacological inducibility tests at the end of the ablation procedure may be effective for evaluating alternate mechanisms of non‐PV substrate or non‐PV triggers and could determine the optimal endpoint of the ablation procedure in individual patients. However, further selective approaches are required to improve the outcome of inducible atrial tachyarrhythmia following PVI in patients with persistent AF.

4.4. Study limitations

The present study had several limitations. First, this was a prospective observational study, and the results of inducibility of atrial tachyarrhythmia were used to guide further ablation added to PVI. In the present study, inducible atrial tachyarrhythmia was always targeted for ablation, and therefore, the clinical outcome might be modified by the additional ablation in patients with inducible atrial tachyarrhythmia following PVI.

Second, any substrate mapping to identify the localization of CFAE or low‐voltage zone was not performed in the present study, and which might be useful to determine selective approaches for substrate modification in individual patients.

Finally, findings of repeat ablation procedures in patients with AT/AF recurrence could not be shown in the present study, because repeat ablation procedures were not fully performed in all patients with recurrent AF/AT. Although we did not assess AF burden after ablation, rare and/or shorter episodes of AF recurrence may be satisfactory to the patients or their physicians, and they may hesitate to refer for repeat ablation.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Achieving neither electrophysiological nor pharmacological inducibility of atrial tachyarrhythmia following PVI was associated with favorable long‐term outcome in patients with persistent AF. The combination of electrophysiological and pharmacological tests may discriminate patients likely to respond to a PVI‐only strategy for persistent AF, with reduction of procedure time and unnecessary additional ablation lesions. Further studies are necessary to determine the optimal ablation strategy for induced atrial tachyarrhythmia after PVI, especially in patients with persistent AF.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Authors declare no conflict of interests for this article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There was no financial support associated with this study.

Otsuka T, Sagara K, Arita T, et al. Impact of electrophysiological and pharmacological noninducibility following pulmonary vein isolation in patients with paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation. J Arrhythmia. 2018;34:501–510. 10.1002/joa3.12085

REFERENCES

- 1. Brooks AG, Stiles MK, Laborderie J, et al. Outcomes of long‐standing persistent atrial fibrillation ablation: a systematic review. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:835–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lin WS, Tai CT, Hsieh MH, et al. Catheter ablation of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation initiated by non‐pulmonary vein ectopy. Circulation. 2003;107:3176–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schmitt C, Ndrepepa G, Weber S, et al. Biatrial multisite mapping of atrial premature complexes triggering onset of atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:1381–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nademanee K, McKenzie J, Kosar E, et al. A new approach for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: mapping of the electrophysiologic substrate. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:2044–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fassini G, Riva S, Chiodelli R, et al. Left mitral isthmus ablation associated with PV isolation: long‐term results of a prospective randomized study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16:1150–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jaïs P, Hocini M, Hsu LF, et al. Technique and results of linear ablation at the mitral isthmus. Circulation. 2004;110:2996–3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Haissaguerre M, Sanders P, Hocini M, et al. Changes in atrial fibrillation cycle length and inducibility during catheter ablation and their relation to outcome. Circulation. 2004;109:3007–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oral H, Chugh A, Lemola K, et al. Noninducibility of atrial fibrillation as an end point of left atrial circumferential ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a randomized study. Circulation. 2004;110:2797–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Essebag V, Baldessin F, Reynolds MR, et al. Non‐inducibility post‐pulmonary vein isolation achieving exit block predicts freedom from atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:2550–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jais P, Hocini M, Sanders P, et al. Long‐term evaluation of atrial fibrillation ablation guided by noninducibility. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:140–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Richter B, Gwechenberger M, Filzmoser P, et al. Is inducibility of atrial fibrillation after radio frequency ablation really a relevant prognostic factor? Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2553–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chang SL, Tai CT, Lin YJ, et al. Efficacy of inducibility and circumferential ablation with pulmonary vein isolation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:607–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oral H, Crawford T, Frederick M, et al. Inducibility of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation by isoproterenol and its relation to the mode of onset of atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:466–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Crawford T, Chugh A, Good E, et al. Clinical value of noninducibility by high‐dose isoproterenol versus rapid atrial pacing after catheter ablation of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010;21:13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Satomi K, Tilz R, Takatsuki S, et al. Inducibility of atrial tachyarrhythmias after circumferential pulmonary vein isolation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: clinical predictor and outcome during follow‐up. Europace. 2008;10:949–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leong‐Sit P, Robinson M, Zado ES, et al. Inducibility of atrial fibrillation and flutter following pulmonary vein ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2013;24:617–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Santangeli P, Zado ES, Garcia FC, et al. Lack of prognostic value of atrial arrhythmia inducibility and change in inducibility status after catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2018;15:660–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Huang W, Liu T, Shehata M, et al. Inducibility of atrial fibrillation in the absence of atrial fibrillation: what does it mean to be normal? Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:489–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kumar S, Kalman JM, Sutherland F, et al. Atrial fibrillation inducibility in the absence of structural heart disease or clinical atrial fibrillation: critical dependence on induction protocol, inducibility definition, and number of inductions. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5:531–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lin YJ, Chang SL, Lo LW, et al. A prospective and randomized comparison of limited versus extensive atrial substrate modification after circumferential pulmonary vein isolation in nonparoxysmal atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2014;25:803–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Elayi CS, Di Biase L, Bai R, et al. Administration of isoproterenol and adenosine to guide supplemental ablation after pulmonary vein antrum isolation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2013;24:1199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chang HY, Lo LW, Lin YJ, et al. Long‐term outcome of catheter ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation originating from nonpulmonary vein ectopy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2013;24:250–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Santangeli P, Zado ES, Hutchinson MD, et al. Prevalence and distribution of focal triggers in persistent and long‐standing persistent atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:374–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee SH, Tai CT, Hsieh MH, et al. Predictors of non‐pulmonary vein ectopic beats initiating paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: implication for catheter ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1054–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lo LW, Lin YJ, Tsao HM, et al. Characteristics of complex fractionated electrograms in nonpulmonary vein ectopy initiating atrial fibrillation/atrial tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:1305–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Elayi CS, DI Biase L, Bai R, et al. Identifying the relationship between the non‐PV triggers and the critical CFAE sites post‐PVAI to curtail the extent of atrial ablation in longstanding persistent AF. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2011;22:1199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Inoue K, Kurotobi T, Kimura R, et al. Trigger‐based mechanism of the persistence of atrial fibrillation and its impact on the efficacy of catheter ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5:295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hayashi K, An Y, Nagashima M, et al. Importance of nonpulmonary vein foci in catheter ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:1918–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Takigawa M, Takahashi A, Kuwahara T, et al. Impact of non‐pulmonary vein foci on the outcome of the second session of catheter ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2015;26:739–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhao Y, Di Biase L, Trivedi C, et al. Importance of non‐pulmonary vein triggers ablation to achieve long‐term freedom from paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in patients with low ejection fraction. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:141–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mohanty S, Trivedi C, Gianni C, et al. Procedural findings and ablation outcome in patients with atrial fibrillation referred after two or more failed catheter ablations. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2017;28:1379–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Voskoboinik A, Moskovitch JT, Harel N, et al. Revisiting pulmonary vein isolation alone for persistent atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14:661–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liang JJ, Elafros MA, Muser D, et al. Pulmonary vein antral isolation and nonpulmonary vein trigger ablation are sufficient to achieve favorable long‐term outcomes including transformation to paroxysmal arrhythmias in patients with persistent and long‐standing persistent atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2016;9:e004239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lin D, Frankel DS, Zado ES, et al. Pulmonary vein antral isolation and nonpulmonary vein trigger ablation without additional substrate modification for treating longstanding persistent atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012;23:806–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chang SL, Tai CT, Lin YJ, et al. Biatrial substrate properties in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:1134–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chao TF, Suenari K, Chang SL, et al. Atrial substrate properties and outcome of catheter ablation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation associated with diabetes mellitus or impaired fasting glucose. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:1615–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]