Abstract

Over the last years, studies on microglia cell function in chronic neuro-inflammation and neuronal necrosis pointed towards an eminent role of these cells in Multiple Sclerosis, Parkinson's and Alzheimer's Disease. It was found, that microglia cell activity can be stimulated towards a pro- or an anti-inflammatory profile, depending on the stimulating signals. Therefore, investigation of receptors expressed by microglia cells and ligands influencing their activation state is of eminent interest.

A receptor found to be expressed by microglia cells is the mineralocorticoid receptor. One of its ligands is Aldosterone, a naturally produced steroid hormone of the adrenal cortex, which mainly induces homeostatic and renal effects. We evaluated if the addition of Aldosterone to LPS stimulated microglia cells changes their inflammatory profile.

Therefore, we assessed the levels of nitric oxide (NO), iNOS, IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α and COX-2 in untreated, LPS-treated and LPS/Aldosterone-treated microglia cells. Furthermore we analyzed p38-MAP-Kinase and NFκB signaling within these cells.

Our results indicate that the co-stimulation with Aldosterone leads to a decrease of the LPS-induced pro-inflammatory effect and thus renders Aldosterone an anti-inflammatory agent in our model system.

Keywords: Cell biology, Immunology, Molecular biology, Neuroscience

1. Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases like Multiple Sclerosis (MS), Alzheimer's Disease (AD), and Parkinson's Disease (PD) are at least partially caused or supported by inflammatory processes, which are possibly induced and prolonged by an overstimulation of microglial cell activity [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. Microglia are phagocytic myeloid cells of the innate immune system and therefore responsible for the first immune defense within the central nervous system (CNS) [7]. Amongst others, it is their responsibility to recognize and fight cerebral pathologies, infections and control neuro-inflammation, to minimize neuronal damage [8]. For a quick response to such conditions, resting microglia continuously survey the local environment with multiple ramifications. When perceiving a pathogen in the CNS, resting microglia become activated and turn into amoeboid like microglia in order to resolve the pathogen [9]. Associated with the activation an increased synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines and enzymes, like interleukin 6 (IL-6), interleukin 1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), inducible NO-synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) occurs. Under transient inflammatory conditions cytokine expression is switched off after some time and the system goes back into a steady-state condition [10]. However, if the inflammatory process persists, chronic inflammation develops, leading to neuronal loss and neurodegeneration [2, 4, 6].

Aldosterone (Aldo) is a naturally produced steroid hormone of the adrenal cortex, mainly inducing homeostatic and renal effects as part of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone-System [11]. Today it is widely accepted, that Aldo plays a specific role in cardiac and endothelial inflammation via binding to an organ specific mineralocorticoid receptor (MCR). Thereby, it induces a pro-inflammatory stimulus, which leads to endothelial destruction. As the MCR is expressed by microglia, Aldo might also be able to influence microglia cell functions through binding to the microglial MCR [12]. Moreover, it has been shown, that in LPS induced uveitis Aldo can also have an anti-inflammatory effect [13]. Therefore, we were keen to investigate the effect of Aldo in a primary microglia cell culture model. Interestingly, we found Aldo to reduce the LPS-induced pro-inflammatory effects on microglia, as evidenced by a reduced expression and secreted protein levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. This effect was mediated by reduced activity within the pro-inflammatory MAPK signal transducer p38.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Microglia cell culture

Primary microglia cells were prepared from rostral mesencephali and cerebral hemispheres of 2 day old Sprague Dawley neonates as described previously [14]. In brief, meninges, hippocampi and choroid plexus were removed from the brains and discarded. Cortices and mesencephali were prepared, minced and enzymatically dissociated. Subsequently, the isolated cells were seeded in cell culture flasks and cultivated in humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. After 8–10 days microglial cells were removed from the adherent astrocytes by shaking and the free-floating cells were harvested by centrifugation. The number of viable microglial cells was estimated by trypan-blue exclusion. To ensure purity of the microglia cell population, immunocytochemistry was carried out as described before [15, 16]. Cells were seeded on glass cover slips and allowed to adhere overnight. Cells were fixed (4% Paraformaldehyde and 0.2% picric acid in PBS) and antibodies against GFAP (1:500) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and OX42 (1:200) (AbCam) were used as described [17]. Translocation of NFκB was assessed as described before [17, 18]. Briefly, cells were seeded on glass slides, stimulated with PBS (control), 200 mM Aldosterone, 5 ng/ml LPS or 200 nM Aldosterone and 5 ng/ml LPS for 60 min and fixed afterwards (4% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% picric acid in PBS). The primary NFκB p65 antibody (1:50) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added for 60 min at room temperature, before the Alexa-488 coupled secondary antibody (1:700) was added for 45 min. Imaging was performed on an Olympus FV1000 confocal laser scanning microscope. Of each group 5 images showing at least 5 cells were taken and compared. Quantification was done with an in house developed computer script deploying ImageMagick (www.imagemagick.org) [15]. Here the overlay of the blue channel (DAPI, nucleus) and the green channel (NFκB p65) was calculated and expressed as the quotient of blue/green.

2.2. Cell stimulation

Microglial cells were seeded in a defined cell number for each experiment (NO measurement: 105 cells/well (96-well-plate), qPCR, ELISA and Western Blotting: 106 cells/well (12-well-plate), immunofluorescence staining: 105 cells/coverslip) and grown for 24 h before cells were stimulated and used for the different experiments. Cells were either stimulated with 200 nM Aldosterone (Sigma), 5 ng/ml Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Salmonella typhimurium, Sigma) or a combination of both. As a control cells were left unstimulated.

2.3. Measurement of nitric oxide production

After stimulation for 6 h or 24 h, levels of nitric oxide (NO) were indirectly determined in the supernatants, by measuring the nitrite accumulation with Griess-reagent (1% sulfanilamide and 0.1% N-(1-naphthyl)-ethylenediamine dihydrochloride in 5% H3PO4, Sigma). 100 μl Griess-reagent and 100 μl of each cell culture supernatant were mixed in triplicates in a 96 well plate and incubated for 15 min at room temperature before the absorption at 550 nm was measured using an automated plate reader (SLT reader 340 ATTC).

2.4. Qualitative PCR and quantitative real time PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated with a Nucleospin® RNA isolation Mini Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) according to the manufacturer's guidelines and RNA concentration was evaluated at 260 nm.

For quantitative reverse transcription, 1 μg RNA was transcribed into cDNA. Possible contaminating DNA was removed by using RNAse-free DNase (Promega). Afterwards the random hexamer primer mix (Amersham Biosciences) was added and after 5 min of primer annealing at 60 °C, the RevertAid™ H Minus M-muLV reverse transcriptase (Fermentas) was added and incubated at 42 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, the mix was heated to 70 °C for 10 min in order to inactivate the reverse transcriptase.

To determine the presence of the mineralocorticoid receptor (MCR) in microglia, the following primer pairs for the qualitative PCR were designed. Primer pair 1: 5′-GAT CCA GGT CGT GAA GTG GG-3′ (sense) and 5′-AGA GGA GTT GGC TGT TCG TG-3′ (antisense), primer pair 2: 5′-TTC AGT ATG CAG CCC TGT GG-3′ (sense) and 5′-TGT TTT CGA CAC TGG GGG AG-3′ (antisense) and primer pair 3: 5′-AGA AAG GTG CTC ACG ACG TT-3′ (sense) and 5′-CGC CTG AAC ATG AGT GCT TG-3′ (antisense).

For PCR a final amount of 0.2 μg cDNA, 33.7 μl RNase free water, 2.5 μl of each pair os primers, 2 μl dNTP-Mix, 10 × reaction buffer (5-Prime) and 0.3 μl Dream-Taq-Polymerase (Thermo Scientific) were mixed. Amplification of the DNA was performed for 35 cycles as follows: 5 min 94 °C, 30 sec 94 °C, 45 sec 60 °C and 30 sec 72 °C. Subsequently 10 μl of the amplified DNA and 1 μl peqGreen were mixed and the DNA was separated on a 2% agarose gel at 120 V and 160 mA. A 100-bp DNA ladder (Fermentas) was used for size control.

For qPCR a final amount of 0.1 μg cDNA, 1 μl TaqMan Assay on demand primer probes (Invitrogen; Table 1), 10 μl TaqMan universal PCR primer mastermix (Invitrogen) and 7 μl RNase free water were mixed and qPCR was performed on an ABI fast 7500 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems). The qPCR signal of the target transcript in the treatment groups was related to that of the control by relative quantification. The 2−ΔΔCT method was used to analyze the relative changes in gene expression. 18S rRNA was used as housekeeping gene and internal control. Results are expressed as percent change of gene expression relative to LPS-stimulated cells which was set to 100%.

Table 1.

qPCR primers.

| Primer | ATaqMan assay on demand identification | Sequenz 5′-3′ |

|---|---|---|

| iNOS (NOS2) | Rn00561646_m1 | CTATTCCCAGCCCAACAACACAGGA |

| IL-6 | Rn00561420_m1 | TGAGAAAAGAGTTGTGCAATGGCAA |

| IL-1β | Rn00580432_m1 | AGCCAACAAGTGGTATTCTCCATGA |

| TNF-α | Rn99999017_m1 | ACCCTCACACTCAGATCATCTTCTC |

| Cox-2 (Ptg2) | Rn00568225_m1 | CTGAGCCATGCAGCAAATCCTTGCT |

| 18S rRNA | Hs99999901_m1 | CCATTGGAGGGCAAGTCTGGTGCCA |

2.5. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were carried out to detect protein levels of soluble IL-6 and TNF-α in the cell supernatants after 6 h and 24 h. ELISAs were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (BD Opt EIA IL-6 (rat IL-6) and BD Opt EIA TNF (rat TNF-α), BD Bioscience).

2.6. Western blotting

Western blot analysis was carried out as described before [19]. In brief, stimulated microglia were washed with PBS three times (4 °C), lysed and homogenized in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 2 mM sodium vanadate, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerol-phosphate and 1 mM phenylmethyl-sulfonylfluoride in acetonitrile). Afterwards the concentrations of isolated total proteins were determined by using BCATM-Kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Thermo Fisher). 10 μg of isolated proteins were mixed with SDS buffer (2.3% (w/v) SDS, 12.5% (v/v) sample buffer (0.5 M Tris-HCL (pH 6.8) and 0.4% (w/v) SDS in distilled water), 10% (v/v) glycerin und 50 mM DTT) and filled up to 40 μl total volume. Samples were denaturized for 5 min (99 °C) prior to separation on a 10% SDS gel and transfer onto a PVDF membrane (Roth). The blotted membrane was blocked for 60 min in 5% (w/v) casein dissolved in TBST buffer (20 mM Tris; 0.14 M NaCl; 1 mM EDTA and 0.1% (w/v) Tween 20). For immune-detection the membrane was incubated with an antibody against phosphorylated p38 MAPK diluted 1:2,000 (p-p38 (Tyr 182) R sc-7975-R, 200 μg/ml, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) overnight at 4 °C. Antibody binding was detected with a HRP-conjugated secondary anti rabbit antibody at 1:30,000 dilution (goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP sc-2004 100 μg/ml, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 h at room temperature and visualized via enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL western blotting detection reagent, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The intensity of each band was quantified using Fusion SL (peqLab). For detection of p38, blots were incubated with an antibody against p38 diluted 1:1,000 (p38 MAPK # D1812, Cell Signaling). Binding was detected by HRP-conjugated secondary anti rabbit antibody diluted 1:20,000 (goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP sc-2031 100 μg/ml, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and visualized as described above. Quantification was carried out by calculating the ratio of phosphorylated p38 and non-phosphorylated p38 (pp38/p38) using the software Fusion SL and Microsoft® Excel.

For detection of IL-1β the detection antibody of an ELISA kit (DY401, R&D, Minneapolis, USA) and the associated HRP coupled secondary antibody (both 1:1000) were used.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Data are shown as Mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean). Statistical analyses were performed with Graph Pad Prism 5 software using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc testing. Significance levels were determined as following: *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001. For the comparison of the area under the curve (AUC), an unpaired t-test with Welch's correction was used.

2.8. Ethics statement

Two day old Sprague Dawley neonates were decapitated before removal of the brain, in accordance with the federal animal welfare and protection law. The devitalization of rats for organ removal was approved by the Ministry of Energy, Agriculture, Environment and Rural Areas of Schleswig-Holstein under the animal experiment application number 723.

3. Results

3.1. Verification of the primary microglia cell culture

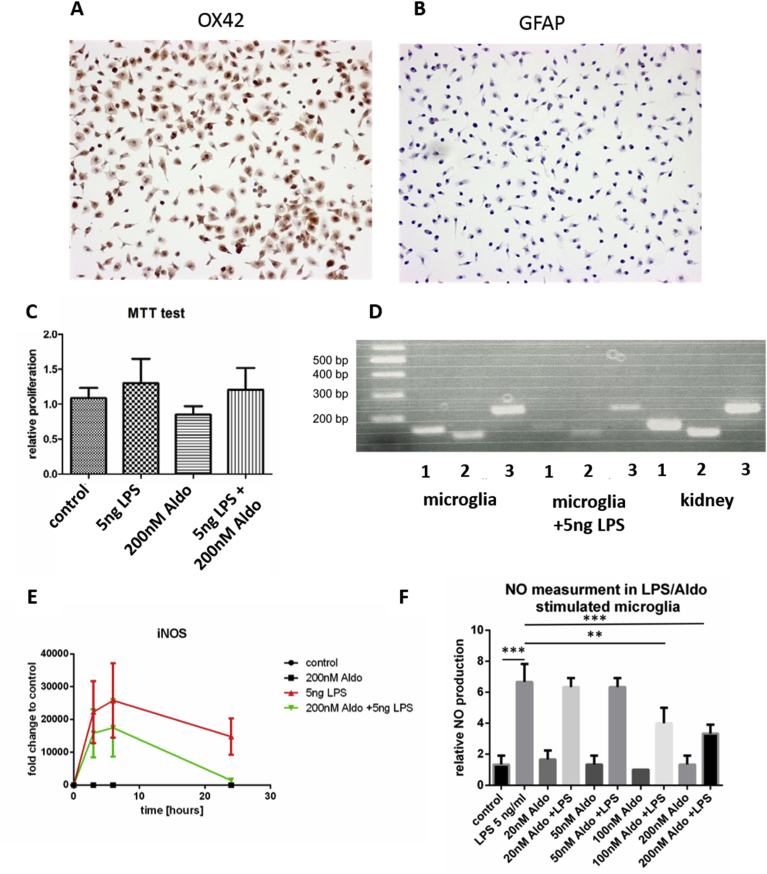

Isolation of primary microglia always involves the risk of co-purification of other cells from the CNS specifically astrocytes are prone to co-purification and maintenance. To exclude contamination, we performed immunocytochemistry and stained for the microglia marker CD11b (Integrin αM) using the OX-42 antibody as reported before [17] (Fig. 1A). As a control we stained for the Astrocyte marker glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), (Fig. 1B). We thereby confirmed the purity of our primary microglia cell population and excluded that the contribution of other cell types to effects detected in this study.

Fig. 1.

Microglia express the mineralocorticoid receptor (MCR) and release NO. A) Immuncytochemical staining of primary rat microglia against the microglia marker OX-42. B) As in A) but staining was performed against GFAP to exclude contamination with astrocytes. C) MTT test to determine cell viability after treatment with PBS (control), Aldostrone (Aldo), LPS or LPS and Aldo to ensure comparable cell numbers after 24 h treatment. D) Qualitative detection of mineral corticoid receptors (MCR) in microglia and, as a positive control, in kidney (original gel Supp-Fig. 1A). E) The production of nitric oxide (NO) upon LPS stimulation can be reduced in a dose dependent manner through the addition of Aldo (n = 4; ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001, one-way ANOVA). F) Expression of the inducible NO synthase (iNOS) in microglia stimulated with PBS (control, black line), Aldo (black line), LPS (red line) or LPS/Aldo (green line) determined at 3 h, 6 h and 24 h.

3.2. Cell viability and MCR monitoring in microglia

We first excluded the cytotoxicity of Aldo on microglia via MTT assay using following groups: PBS treated control, 5 ng/ml LPS, 200 nM Aldo and a combination of 5 ng/ml LPS and 200 mM Aldo. Although the LPS treated groups showed a slightly higher proliferation, these effects were not statistically significant (Fig. 1C). To re-evaluate the expression of the MCR in our microglia culture system, qualitative PCR analyses were performed and cDNA of the latter was found in unstimulated and LPS stimulated microglia (Fig. 1D). As a positive control rat kidney cDNA was used, as the MCR is expressed in this organ (Fig. 1D) [20]. As we found amplification products for all three primer pairs used for verification of the MCR, its expression was confirmed in the primary rat microglia system used in this study. However, the expression seemed to be reduced in LPS treated cells.

3.3. Aldo mediated decrease of NO-release

One hallmark of LPS induced inflammation in microglia cells is the release of nitric oxide (NO) into the cell culture supernatant [9]. Griess-Assay allows an indirect measurement of the NO levels in cell supernatants of LPS stimulated vs. LPS and Aldo stimulated cells. We found that the amount of NO released into the supernatant decreases in a dose and time dependent manner. Microglia cells were activated with LPS or LPS and increasing amounts of Aldo. We found that the NO release was significantly reduced at 100 nM and at 200 nM Aldo upon incubation for 24 h. Incubation with Aldo alone did not induce the release of NO compared to non-treated control cells (Fig. 1E). In microglia NO is produced by the inducible NO-synthase (iNOS) and therefore we evaluated the expression of this enzyme. Since 200 nM Aldo had the strongest effect, we used this concentration and followed the iNOS expression over 24 h. A clear trend for a reduced expression of iNOS was seen in LPS-stimulated microglia when co-treated with Aldo (Fig. 1F). The incubation with Aldo alone did not show a difference compared to control cells (Fig. 1F).

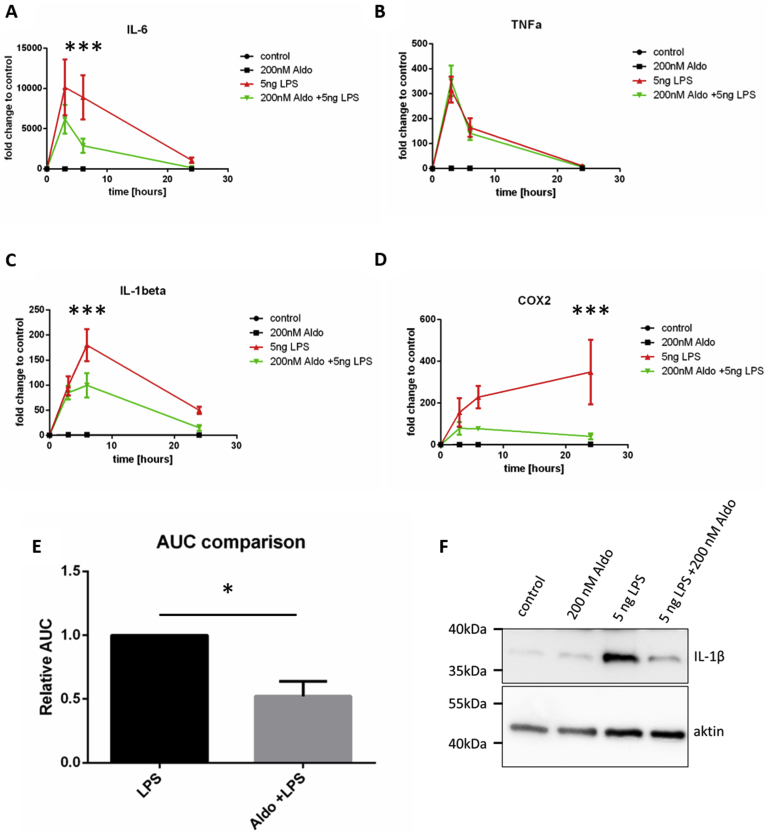

3.4. Aldo reduces the mRNA expression of IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α and COX2

Expression of pro-inflammatory cytokinesis an important step within the inflammatory response of microglia cells [10]. Thus we investigated the influence of Aldo on the mRNA-expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α or the IL-6- and IL-1β-induced enzyme COX2 in LPS activated microglia. Therefore, microglia were stimulated with either LPS or Aldo alone or a combination of LPS and Aldo for 3 h, 6 h or 24 h. As a control we used untreated or Aldo only treated cells.

For IL-6 and IL1β we found a significantly reduced expression 6 h after LPS stimulation, when cells were co-stimulated with Aldo (Fig. 2A,C). For TNF-α no alteration was found on the expression level upon Aldo treatment (Fig. 2B). The expression of all three cytokines returned to almost control conditions after 24 h (Fig. 2A–C). In contrast, the expression of COX2, which is dependent upon IL-6 and IL-1β, was found most upregulated in LPS stimulated microglia after 24 h (Fig. 2D). In LPS and Aldo co-stimulated microglia the induction of COX2 was strongly reduced, and a significant difference was measured at 24 h. To assess the overall cytokine expression, we determined the area under the curve (AUC) for iNOS, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β and COX2. When comparing LPS and LPS/Aldo stimulated groups, a significant decrease in expression was found for the LPS/Aldo treated group. For IL-1β an additional reduction was found on the protein level, when cells were treated with Aldo in addition to LPS (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

Aldo reduces LPS induced cytokine expression. A–D) The expression levels of IL-6 (A), TNF-α (B), IL-1β (C) and COX2 (D) were determined for PBS (control, black line), Aldo (black line), LPS (red line) and LPS/Aldo stimulation (green line). Under unstimulated conditions (control) or Aldo stimulation only (Aldo 200 nM) no expression of the cytokines was measured. For IL-6 (A), IL-1β (C) and COX2 a significantly reduced expression was detected, when cells were co-stimulated with LPS/Aldo compared to LPS stimulation only (n = 4; *** p ≤ 0.001, one-way ANOVA). E) Comparison of the area under the curve (AUC) between LPS and LPS/Aldo stimulated cells for the expression of iNOS, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β and COX2 (n = 5, * p ≤ 0.05, unpaired t-test) F) Western blot analysis of IL-1β 6 h after treatment of microglia. Note the reduction after co-incubation with LPS and Aldo (original Western Blot Supp-Fig. 1B).

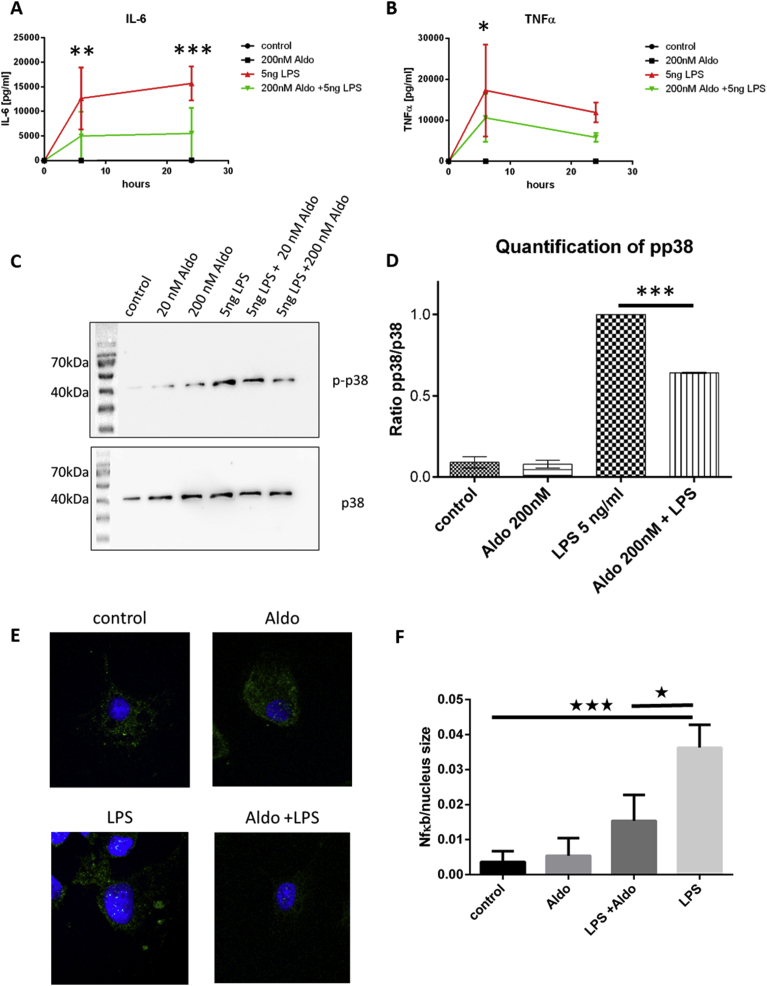

3.5. Aldo reduces IL-6 and TNF-α secretion, p38 activation and NFκB translocation

As we found reduced expression of cytokines in LPS activated microglia upon co-incubation with Aldo, we used ELISA analysis to further examine an Aldo mediated influence on activated microglia. Therefore, we investigated supernatant protein levels of IL-6 and TNF-α after microglial stimulation with Aldo, LPS or a combination of both after 6 h and 24 h, whereby the single LPS-stimulation was again used as a reference (Fig. 3A,B). For both cytokines a reduced secretion was detected, which was especially reduced for IL-6 (Fig. 3A). This fits to the cytokine expression profile and underlines the anti-inflammatory effect of Aldo in microglia. As toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signalling is induced by LPS stimulation [21], we looked at its downstream signal transducer p38. Here, we found a reduced phosphorylation after co-treatment of microglia with LPS/Aldo (Fig. 3C,D). Another hallmark of stimulated microglia is the translocation of NFκB p65 into the nucleus. Here, a reduction of the LPS induced translocation was seen upon co-incubation with Aldo (Fig. 3E,F).

Fig. 3.

Aldo reduces IL-6 and TNF-α protein amounts released by microglia cells. A-B) IL-6 and TNF-α levels were determined in supernatants of cells stimulated with LPS or LPS and Aldo by ELISA. For both cytokines a significant reduction was measured under co-stimulation conditions after 6 h and 24 h. The unstimulated (control) or Aldo only treated cells did not release measureable amounts of IL-6 or TNF-α. (n = 4; * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.001, *** p ≤ 0.001, one-way ANOVA) C) Western blot analyses of p38 phosphorylation under increasing amounts of Aldo (original blot Supp-Fig. 1C). D) Quantification of C) reveals that the p38 phosphorylation is significantly reduced after co-stimulation of LPs activated microglia with Aldo (*** p ≤ 0.001, one-way ANOVA) E) Representative images of 1 h stimulated microglia stained for NFκB (p65) (green) and the nucleus (blue). F) Quantification of the co-localization of NFκB with the nucleus (n = 4 images per group with at least 5 cells per image; * p ≤ 0.05, *** p ≤ 0.001, one-way ANOVA).

Taken together we could show, that Aldo reduces different pro-inflammatory hallmarks in our primary microglia cell culture model.

4. Discussion

Neurodegenerative diseases like MS, AD, and PD are thought to be connected to a dysregulation of microglia cell activation, leading to chronic neuro-inflammation and neuro-degeneration [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. Recently a new population of microglia cells was described that is located around Aβ-plaques and features a pro-inflammatory gene expression profile [22]. Thus, the identification of compounds which exert anti-inflammatory effects is of eminent interest. Here, we investigated a possible anti-inflammatory effect of Aldo on LPS activated primary rat microglia cells in vitro. We were able to confirm the expression of MCR by microglia which is a prerequisite for any Aldo mediated effect on these cells [8, 13].

We investigated the effect of Aldo on LPS activated microglia cells by measuring different pro-inflammatory mediators. In cell supernatants we found a significant reduction of NO, which is known to increase the amount of reactive oxygen species such as super oxide or peroxynitrite, both connected with neuronal loss [9, 23, 24]. Additionally, we found that Aldo reduces the expression of iNOS, the NO producing enzyme, which is highly expressed in activated microglia [9, 25].

Pro-inflammatory cytokines play a key role in neuro-inflammation and microglial activation. They can induce a self-amplifying feedback loop of neuronal inflammation that is detrimental and might play a role in many diseases such as MS, AD, PD [1, 3, 5, 26, 27, 28, 29]. Thus, we investigated the levels of IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α and the enzyme COX-2 in LPS activated microglia cells after the addition of Aldo. On the transcriptional level all cytokines (except TNF-α) and COX-2 were decreased significantly under the influence of Aldo in a time dependent manner. For IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α we found significantly lower protein levels upon co-stimulation with Aldo compared to LPS stimulation alone. For TNF-α this was surprising, as it was not seen on the transcriptional level. As the MAP-kinase- and the NFκB-pathway are well described transcriptional pathways activated upon LPS stimulation [10, 17, 30], leading towards transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines [10, 30, 31], we investigated the influence of Aldo on these pathways. We found that the incubation of LPS-activated microglia with Aldo leads to a decreased phosphorylation of the MAPK signaling mediator p38 and a reduced translocation of NFκB to the nucleus. The exact molecular mechanism how the Aldo induced signal interferes with these two signaling pathways, remains to be deciphered. However, our results indicate that Aldo has a different effect on microglia cells, compared to those on endothelial cells in earlier studies, where it was described to induce rather pro-inflammatory effects [30, 32]. On the other hand, an anti-inflammatory effect of Aldo has been described earlier in a model of LPS induced uveitis [13]. However, the influence of other cell types could not be ruled out in the uveitis model and thus we can now show a direct anti-inflammatory effect of Aldo on microglia. The physiological levels of Aldo in serum vary between new-borns (up to 8500 ng/l; ∼23 nM) and adults (∼150 ng/l; ∼0.4 nM) by a factor of about 20. Physiologically, only minor levels of Aldo reach the CNS, due to a strict control of the blood brain barrier [33]. In the brain another glucocorticoid, namely cortisol, binds to MCR as it circulates in micromolar concentrations there. However, in vitro studies have shown, that Aldo has a 10 fold higher potential to stimulate transcriptional changes, when interacting with MCR, then cortisol [34]. Future studies will have to elucidate if a direct application of Aldo into CNS cavities shows beneficial effects on inflammatory parameters.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Björn-Ole Bast, Uta Rickert, François Cossais: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Janna Schneppenheim: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Henrik Wilms: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Philipp Arnold: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Ralph Lucius: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the CH Foundation PO Box 94038 Lubbock, TX 794-934-038 (to Henrik Wilms and Ralph Lucius). Philipp Arnold is supported by CRC877 (Project A13).

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank Gaby Steinkamp, Monika Grell, Inez Götting, Marion Kölln, and Katrin Masuhr for excellent technical assistance. We acknowledge Z3 unit of CRC877 for access to the CLSM.

Contributor Information

Philipp Arnold, Email: p.arnold@anat.uni-kiel.de.

Ralph Lucius, Email: rlucius@anat.uni-kiel.de.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Loma I., Heyman R. Multiple sclerosis: pathogenesis and treatment. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2011;9(3):409–416. doi: 10.2174/157015911796557911. PubMed PMID: 22379455; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3151595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bogie J.F., Stinissen P., Hendriks J.J. Macrophage subsets and microglia in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128(2):191–213. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1310-2. PubMed PMID: 24952885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holtzman D.M., Morris J.C., Goate A.M. Alzheimer's disease: the challenge of the second century. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3(77):77sr1. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002369. PubMed PMID: 21471435; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3130546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mandrekar-Colucci S., Landreth G.E. Microglia and inflammation in Alzheimer's disease. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets. 2010;9(2):156–167. doi: 10.2174/187152710791012071. PubMed PMID: 20205644; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3653290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lees A.J., Hardy J., Revesz T. Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 2009;373(9680):2055–2066. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60492-X. PubMed PMID: 19524782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perry V.H., Holmes C. Microglial priming in neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2014;10(4):217–224. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.38. PubMed PMID: 24638131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Napoli IN H. Microglial clearance function in health and disease. Neuroscience. 2009;158(3):1030–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nimmerjahn A., Kirchhoff F., Helmchen F. Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo. Science. 2005;308(5726):1314–1318. doi: 10.1126/science.1110647. PubMed PMID: 15831717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sierra A., Navascues J., Cuadros M.A., Calvente R., Martin-Oliva D., Ferrer-Martin R.M. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in microglia of the developing quail retina. PLoS One. 2014;9(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106048. PubMed PMID: 25170849; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4149512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kettenmann H., Hanisch U.K., Noda M., Verkhratsky A. Physiology of microglia. Physiol. Rev. 2011;91(2):461–553. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2010. PubMed PMID: 21527731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Booth R.E., Johnson J.P., Stockand J.D. Aldosterone. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2002;26(1-4):8–20. doi: 10.1152/advan.00051.2001. PubMed PMID: 11850323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka J., Fujita H., Matsuda S., Toku K., Sakanaka M., Maeda N. Glucocorticoid- and mineralocorticoid receptors in microglial cells: the two receptors mediate differential effects of corticosteroids. Glia. 1997;20(1):23–37. PubMed PMID: 9145302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bousquet E., Zhao M., Ly A., Leroux Les Jardins G., Goldenberg B., Naud M.C. The aldosterone-mineralocorticoid receptor pathway exerts anti-inflammatory effects in endotoxin-induced uveitis. PLoS One. 2012;7(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049036. PubMed PMID: 23152847; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3494666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilms H., Sievers J., Rickert U., Rostami-Yazdi M., Mrowietz U., Lucius R. Dimethylfumarate inhibits microglial and astrocytic inflammation by suppressing the synthesis of nitric oxide, IL-1beta, TNF-alpha and IL-6 in an in-vitro model of brain inflammation. J. Neuroinflamm. 2010;7:30. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-30. PubMed PMID: 20482831; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2880998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bedau T., Peters F., Prox J., Arnold P., Schmidt F., Finkernagel M. Ectodomain shedding of CD99 within highly conserved regions is mediated by the metalloprotease meprin beta and promotes transendothelial cell migration. FASEB J. 2017;31(3):1226–1237. doi: 10.1096/fj.201601113R. PubMed PMID: 28003343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandenburg L.O., Varoga D., Nicolaeva N., Leib S.L., Wilms H., Podschun R. Role of glial cells in the functional expression of LL-37/rat cathelin-related antimicrobial peptide in meningitis. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2008;67(11):1041–1054. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31818b4801. PubMed PMID: 18957897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnold P., Rickert U., Helmers A.K., Spreu J., Schneppenheim J., Lucius R. Trefoil factor 3 shows anti-inflammatory effects on activated microglia. Cell Tissue Res. 2016;365(1):3–11. doi: 10.1007/s00441-016-2370-5. PubMed PMID: 26899249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Behrendt P., Arnold P., Brueck M., Rickert U., Lucius R., Hartmann S. A helminth protease inhibitor modulates the lipopolysaccharide-induced proinflammatory phenotype of microglia in vitro. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2016;23(2):109–121. doi: 10.1159/000444756. PubMed PMID: 27088850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnold P., Schmidt F., Prox J., Zunke F., Pietrzik C., Lucius R. Calcium negatively regulates meprin beta activity and attenuates substrate cleavage. FASEB J. 2015;29(8):3549–3557. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-272310. PubMed PMID: 25957281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amin M.S., Wang H.W., Reza E., Whitman S.C., Tuana B.S., Leenen F.H. Distribution of epithelial sodium channels and mineralocorticoid receptors in cardiovascular regulatory centers in rat brain. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2005;289(6):R1787–R1797. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00063.2005. PubMed PMID: 16141309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCarthy G.M., Bridges C.R., Blednov Y.A., Harris R.A. CNS cell-type localization and LPS response of TLR signaling pathways. F1000 Res. 2017;6:1144. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.12036.1. PubMed PMID: 29043065; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5621151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keren-Shaul H., Spinrad A., Weiner A., Matcovitch-Natan O., Dvir-Szternfeld R., Ulland T.K. A unique microglia type associated with restricting development of Alzheimer's disease. Cell. 2017;169(7):1276–1290 e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.018. PubMed PMID: 28602351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vincent V.A., Tilders F.J., Van Dam A.M. Inhibition of endotoxin-induced nitric oxide synthase production in microglial cells by the presence of astroglial cells: a role for transforming growth factor beta. Glia. 1997;19(3):190–198. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199703)19:3<190::aid-glia2>3.0.co;2-3. PubMed PMID: 9063726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuste J.E., Tarragon E., Campuzano C.M., Ros-Bernal F. Implications of glial nitric oxide in neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015;9:322. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00322. PubMed PMID: 26347610; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4538301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pacher P., Beckman J.S., Liaudet L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2007;87(1):315–424. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2006. PubMed PMID: 17237348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2248324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith J.A., Das A., Ray S.K., Banik N.L. Role of pro-inflammatory cytokines released from microglia in neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Res. Bull. 2012;87(1):10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.10.004. PubMed PMID: 22024597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rose J.W., Hill K.E., Watt H.E., Carlson N.G. Inflammatory cell expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in the multiple sclerosis lesion. J. Neuroimmunol. 2004;149(1-2):40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.12.021. PubMed PMID: 15020063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang W.Y., Tan M.S., Yu J.T., Tan L. Role of pro-inflammatory cytokines released from microglia in Alzheimer's disease. Ann. Transl. Med. 2015;3(10):136. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.03.49. PubMed PMID: 26207229; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4486922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teismann P. COX-2 in the neurodegenerative process of Parkinson's disease. Biofactors. 2012;38(6):395–397. doi: 10.1002/biof.1035. PubMed PMID: 22826171; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3563218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu C.J., Wang Q.Q., Zhou J.L., Liu H.Z., Hua F., Yang H.Z. The mineralocorticoid receptor-p38MAPK-NFkappaB or ERK-Sp1 signal pathways mediate aldosterone-stimulated inflammatory and profibrotic responses in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2012;33(7):873–878. doi: 10.1038/aps.2012.36. PubMed PMID: 22659623; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4011158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chantong B., Kratschmar D.V., Nashev L.G., Balazs Z., Odermatt A. Mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors differentially regulate NF-kappaB activity and pro-inflammatory cytokine production in murine BV-2 microglial cells. J. Neuroinflamm. 2012;9:260. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-260. PubMed PMID: 23190711; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3526453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilbert K.C., Brown N.J. Aldosterone and inflammation. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2010;17(3):199–204. doi: 10.1097/med.0b013e3283391989. PubMed PMID: 20422780; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4079531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geerling J.C., Loewy A.D. Aldosterone in the brain. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2009;297(3):F559–F576. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90399.2008. PubMed PMID: 19261742; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2739715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arriza J.L., Simerly R.B., Swanson L.W., Evans R.M. The neuronal mineralocorticoid receptor as a mediator of glucocorticoid response. Neuron. 1988;1(9):887–900. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90136-5. PubMed PMID: WOS:A1988R144000013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.