Abstract

Background and aims

Tinder is a geo-located online dating application, which is present in almost 200 countries and has 10 million daily users. The aim of the present research was to investigate the motivational, personality, and basic psychological need-related background of problematic Tinder use.

Methods

After qualitative pretest and item construction, in Study 1 (N = 414), confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to corroborate the different motivational factors behind Tinder use. In Study 2 (N = 346), the associations between Big Five traits, Tinder motivations, and problematic Tinder use were examined with structural equation modeling (SEM). In Study 3 (N = 298), the potential role of general self-esteem, relatedness need satisfaction, and frustration in relation to Tinder-use motivations and problematic Tinder use was examined with SEM.

Results

In Study 1, a 16-item first-order factor structure was identified with four motivational factors, such as sex, love, self-esteem enhancement, and boredom. In Study 2, problematic Tinder use was mainly related to using Tinder for self-esteem enhancement. The Big Five personality factors were only weakly related to the four motivations and to problematic Tinder use. Counterintuitively, Study 3 showed that instead of global self-esteem, relatedness need frustration was the strongest predictor of self-esteem enhancement Tinder-use motivation which, in turn, was the strongest predictor of problematic Tinder use.

Discussion

Four motivational factors were identified as predictors of problematic use with need frustration being a relevant background variable instead of general personality traits.

Keywords: Big Five Inventory (BFI), need satisfaction, need frustration, Tinder-use motivations, problematic Tinder use, self-determination theory (SDT)

Introduction

One third of US marriages are a result of people meeting on online dating sites (Cacioppo, Cacioppo, Gonzaga, Ogburn, & VanderWeele, 2013). Such popularity of online dating is rooted in the advantages it has compared with offline dating: the threat of perceived rejections is lower, it requires less effort and time, partners can easily be preselected based on a number of preferences, and it can extend one’s social network more effectively (Couch & Liamputtong, 2008; Wiederhold, 2015). As online dating sites construct specific situations, it can lead to specific self-presentation strategies (Whitty, 2008; Whitty & Young, 2016), which can be text- and photo-based. The present research focuses on one of the most recent forms of location-based, smartphone-related online dating applications, and the most prominent exemplar of it: Tinder, which mainly allows photo-based self-presentation. This application (and service) is present in 196 countries (Dredge, 2015) and has 10 million daily users (Smith, 2016). In contrast to classical dating sites, Tinder – as a geo-located application – has the advantages of the mobile platform in terms of locatability, portability, availability, and multimediality (Marcus, 2016; Schrock, 2015). Despite Tinder’s popularity and its advantages, no empirical study examined the psychological background of problematic Tinder use. For this purpose, first, a short and reliable measure was constructed that can assess the different aspects of Tinder-use motivations. Subsequently, the motivational, personality, and need-related background of problematic Tinder use was explored.

Tinder is a dating smartphone application, which uses the location of users to offer them potential dating partners. The mechanism of Tinder is really simple: after downloading the application, one can set up a profile by connecting his/her Tinder account to Facebook, resulting in automatic data synchronization. Then, a dating pool can be set up from which the dater can choose potential future partners. Basic information can be filtered, such as age or the distance of potential partners. When this setup is finished, the act of “Tindering” can start. The user gets a photo and has to decide if he/she likes that person or not based on that photo. If he/she likes the other person, he/she has to swipe the picture of this person right. If he/she does not like that individual, he/she has to swipe left. If both parties like each other and swipe right, they are “matched” and conversations begin (Margalit, 2014). Subsequently, a message can be sent, and users can only talk to each other if they are mutually interested; as Tinder provides very limited information of the user (pictures, education, age, mutual interests, and mutual friends), it is convenient to browse through people (Xia, 2014, as cited in Dickson, 2014).

The built-in characteristics of Tinder can also be important from the perspective of problematic use, such as the fact that small effort is necessary for selecting potential partners, there is no opportunity for rejection, very high availability, and affordability. Problematic Tinder use (Orosz, Tóth-Király, Bőthe, & Melher, 2016) can be defined on the basis of Griffiths’ (2005) six-component model including the following components: salience (Tinder use dominates thinking and behavior), mood modification (Tinder improves mood), tolerance (increasing amounts of Tinder use), withdrawal (occurrence of unpleasant feelings when Tinder use is discontinued), conflict (Tinder use compromises social relationships and other activities), and relapse (reversion to earlier patterns of Tinder use after abstinence or control). As far as we know, no prior research examined the motivational or personality background of problematic Tinder use.

The six-component model of Griffiths (2005) was examined in case of several online behaviors such as social media addiction (Andreassen, Torsheim, Brunborg, & Pallesen, 2012), problematic series watching (Orosz, Bőthe, & Tóth-Király, 2016), Youtube addiction (Balakrishnan & Griffiths, 2017), or online pornography addiction (Bőthe et al., 2018). This model appears to be theoretically well-established and appropriate regarding diverse online problematic behaviors and behavioral addictions. Similarly to other behaviors, such as online gaming or Internet addiction (e.g., Billieux et al., 2011; Király et al., 2015; Kwon, Chung, & Lee, 2011; Yee, 2006; Zanetta Dauriat et al., 2011), certain motivations are expected to lead to problematic behavior, whereas others are not. Despite the motivational background of various online activities are identified, the role of Tinder-use motivations in problematic Tinder use has not been investigated before.

Only a few exploratory studies examined the motivational basis of Tinder use. Ligtenberg (2015) identified four motivational factors behind Tinder use in a questionnaire study: entertainment, social interaction, identity exploration, and information. The social interaction factor included motivations of finding a soulmate or sexual partners. The entertainment factor was related to having fun and relieving boredom. The identity exploration factor was close to getting the feeling of empowerment through gaining knowledge about the self and getting information about who they are and what they would like from life. In case of Tinder use, it can be used for elevating self-esteem. Finally, the information factor referred to the need of social comparison and the need to gain information about the user’s own attractiveness. Qualitative studies pointed out that the speed of decisions and the immediate gratification features of Tinder might be also relevant regarding its motivational background (Chamorro-Premuzic, 2014; Seefeldt, 2014).

More recently, Ranzini and Lutz (2016) adapted Van de Wiele and Tong’s (2014) Grindr (a dating site for LGBTQ males) motives and gratification scale to Tinder and identified six motives: sex (finding sexual partners), friends (building social network), relationship (finding someone to date), traveling (dating in a different place), self-validation (getting an ego-boost), and entertainment (satisfying social curiosity). Although this measure aimed to assess various motivations behind Tinder use, it did not have strong psychometric properties in terms of factor structure.

Considering the shortcomings of prior Tinder motivation measures, the main goal was to construct a new measure, which is based on qualitative data and has strong psychometric properties in terms of factor structure and reliability. In Study 1, the psychometric properties of a new Tinder Use Motivation Scale (TUMS) were tested. In Study 2, Tinder-use motivations and general personality traits were investigated as potential predictors of problematic Tinder use. In Study 3, general self-esteem, the need-related background, and Tinder-use motivations were examined as predictors of problematic Tinder.

Study 1 – The Development of the TUMS

The aim of this study was to construct items on the basis of qualitative answers for the TUMS, which could assess the most important motivations of Tinder use. We aimed to construct a short measure with strong psychometric properties in terms of factor structure, construct validity, and internal consistency.

Methods

Procedure

An online questionnaire system was used to carry out data gathering, which occurred in April 2015 in various public Facebook groups. Before participations, potential respondents were informed about the aims of the study and they were also assured of their anonymity. They had to explicitly indicate their willingness to participate. If they did so, the first part of the questionnaire included the TUMS. The subsequent page contained demographic and Tinder-specific questions (e.g., gender, age, level of education, relationship status, and their frequency of Tinder use). The fill-out process took 5 min on average. Six-hundred and seven respondents started to fill the questionnaire, but three of them did not agree to participate in the research, and 190 of them indicated at the beginning that they have never used Tinder. Therefore, for the data analysis, we used the responses of 414 (female = 246, 59.4%) respondents.

Participants

The sample of Study 1 included 414 Hungarian participants (female = 246; 59.4%) between the ages of 18 and 43 years (Mage = 22.71 years; SDage = 3.56 years). They reported their place of residence as the capital city (63.1%), county towns (8.2%), towns (22.2%), or villages (6.5%); their highest level of education as primary (4.1%), secondary (61.1%), and higher education (34.8%); and their relationship status as single (78%) or in a relationship (22%).

Measures

To assess the most important factors of Tinder-use motivations, a focus group of 17 Tinder user university students (5 males, 12 females, Mage = 20.59 years; SDage = 1.78) was invited for multiple sessions to qualitatively assess diverse aspects of Tinder-use motivation as precisely as they can. For item construction, the protocol of Tóth-Király, Bőthe, Tóth-Fáber, Hága, and Orosz (2017) was followed. As a result of this procedure, a total of 16 items were constructed. A 7-point scale was chosen as answer options (ranging from 1 = not true to me at all to 7 = completely true to me).

The boredom factor included three items referring to the individual’s reasons to use Tinder to relieve boredom (e.g., “If I’m bored, I use Tinder”). The self-esteem factor included three items referring to using Tinder to enhance self-esteem (e.g., “I feel that I’m more valuable after using Tinder than before.”). The sex factor refers to using Tinder to satisfy sexual needs by finding a casual partner (e.g., “I signed up to Tinder to find sexual partners.”). The love factor included items referring to using Tinder to find consummate love (Sternberg, 1986). Therefore, this factor included two items from the three aspects of love as intimacy (e.g., “I use Tinder to establish intimate relationship with someone.”), commitment (e.g., “I wish to find a committed partner on Tinder.”), and passion (e.g., “I look for the overflowing love.”).

Statistical analysis

Normality was assessed by the investigation of skewness and kurtosis. Curran, West, and Finch (1996) recommended the absolute values of 2.0 for skewness and 7.0 for kurtosis, which could be interpreted as thresholds for acceptability. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was then performed in Mplus 7.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2015) with maximum likelihood estimation. When assessing the models, multiple goodness of fit indices were observed (Brown, 2015) with good or acceptable values based on the following thresholds (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Marsh, Hau, & Grayson, 2005). Regarding the comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), values higher than 0.95 indicated that a model had good fit, whereas values higher than 0.90 indicated that a model had acceptable fit. Regarding the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with its 90% confidence interval (90% CI), a model can be considered good if its RMSEA value is below 0.06, whereas it can be considered acceptable if this value is below 0.08. When assessing the magnitude of the factor loadings, the suggestions of Comrey and Lee (1992) were employed: ≥0.45 as fair, ≥0.55 as good, ≥0.63 as very good, and ≥0.71 as excellent.

Internal consistency was measured by Cronbach’s α using Nunnally’s (1978) suggestions about the acceptability of the value (0.70 is acceptable and 0.80 is good). However, as Cronbach’s α can be less reliable (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2014; Sijtsma, 2009), one additional index was calculated as an indicator of reliability: factor determinacy (FD). FD describes the correlation between the true factor scores and the estimated ones with values closer to one indicating higher levels of reliability (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2015).

Moreover, to test whether gender and age could have an effect on TUMS scores, a Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes (MIMIC) analysis (Brown, 2015) was carried out. MIMIC models are regression models essentially where the latent variables are regressed on a number of predictors.

Ethics

This research including all three studies was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and it was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Eötvös Loránd University. All respondents provided informed consent.

Results and Brief Discussion

The factor structure of the TUMS

First, the normality of the items was examined and did not violate the thresholds of Curran et al. (1996) neither for skewness (ranging from −0.69 to 2.21), nor for kurtosis (ranging from −1.17 to 4.37). Then, a first-order model with four factors was examined with CFA and showed acceptable model fit (CFI = 0.966, TLI = 0.959, RMSEA = 0.067, [90% CI = 0.058–0.076]). The four factors were well-defined by their respective factor with factor loadings (overall λ = 0.62 − 0.96, M = 0.85), while interfactor correlations were moderate (overall r = |.08| − |.29|, M = 0.19). The internal consistencies of the four factors (αlove = 0.96, αself-esteem = 0.89, αsex = 0.91, and αboredom = 0.82) and the FDs (FDlove = 0.98, FDself-esteem = 0.97, FDsex = 0.97, and FDboredom = 0.92) were adequate.

MIMIC model analysis

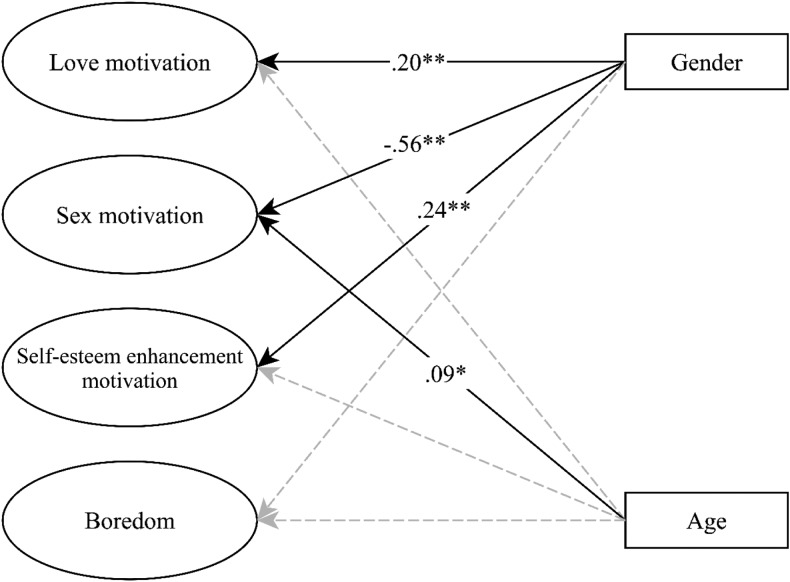

To investigate the effect of gender and age on Tinder-use motivations, a MIMIC analysis was applied. The model fit indices showed that the model remained acceptable (CFI = 0.964, TLI = 0.956, RMSEA = 0.063, [90% CI = 0.055–0.071]). Gender (males were coded as 0, whereas females were coded as 1) was significantly associated with love (β = 0.20, p < .001), sex (β = −0.56, p < .001), and self-esteem (β = 0.24, p < .001) motivations; however, it was not significantly related to the boredom motivation (β < −0.01, p = .965). Moreover, age was significantly associated only with the sex motivation (β = 0.09, p = .043), whereas it was not related to love (β = 0.08, p = .089), self-esteem (β = −0.05, p = .288), and boredom (β = −0.07, p = .213) motivations (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The MIMIC model of Tinder-use motivations (Study 1). Note. All variables presented in ellipses are latent variables. For the sake of clarity, indicator variables related to them were not depicted in this figure. One-headed arrows represent standardized regression weights. Dashed lines represent non-significant pathways. Factor correlations are not depicted. Gender was coded as male = 0 and female = 1. *p < .05. **p < .01

According to the results of Study 1, the TUMS is a reliable measure of Tinder-use motivations with established factor structure (see Appendix for the final items). The four identified factors are in line with prior qualitative and quantitative studies on online and geo-located smartphone dating motivations (Couch & Liamputtong, 2008; Levine, 2015; Ligtenberg, 2015; Quiroz, 2013). Women were more likely to use Tinder to find “true love” and to boost their self-esteem, whereas men were more likely to use Tinder to find casual sex. Furthermore, older users were slightly more likely to use Tinder to find casual sex partners. In the following step, we explored the potential background variables behind these motivations.

Study 2 – The Five-Factor Personality Background of Problematic Tinder Use and the Mediating Role of Tinder-Use Motivations

The aim of this study was to examine how motivations of Tinder use are related to problematic Tinder use. Previously, a negative relationship was found between self-esteem and different online behavioral addictions or addictive tendencies, such as excessive Internet use (Armstrong, Phillips, & Saling, 2000), instant messaging (Ehrenberg, Juckes, White, & Walsh, 2008), and problematic or addictive mobile phone use (Bianchi & Phillips, 2005; Ha, Chin, Park, Ryu, & Yu, 2008; Leung, 2008). With obtaining matches, Tinder can provide frequent immediate positive social feedback or reward from many different potential partners and it can become one of the important sources of enhancing self-esteem. Therefore, self-esteem enhancement through Tinder use can be a potential predictor of problematic Tinder use.

In addition, our second goal was to identify the personality background of Tinder-use motivations using the Big Five personality theory (John & Srivastava, 1999). Based on problematic social networking site use, we expected that neuroticism and extraversion are positively related to problematic Tinder use, whereas openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness are negatively related to it (Andreassen et al., 2012). Besides these expectations, we did not hypothesize specific relationships between personality factors, boredom, love-, and sex-related Tinder motivations.

Methods

Procedure

The study was conducted on an online platform; it took approximately 10 min to fill out the questionnaire. Data collection occurred in the spring of 2016 in different public Facebook groups. Similar to the previous study, participants were informed about the aims and the content of the study and they were assured of their anonymity and the confidentiality of their answers. Besides general demographic questions, Tinder-use motivations and problematic Tinder use were assessed.

Participants

A total number of 376 participants were recruited for this study, although 30 participants had to be excluded from the sample, because they were either underaged (11 individuals) or have never used Tinder before (19 individuals). Therefore, 346 (female = 165, 47.7%) respondents remained in the final sample who were aged between 18 and 51 (Mage = 22.02; SDage = 3.41). The vast majority of them were still enrolled into college or university (260; 75.1%), 50 (14.5%) have finished college or university, 25 (7.2%) had high-school degree, and 11 (3.2%) were still enrolled in high school. About 225 (65.1%) of them lived in the capital, 41 (11.8%) in county towns, 62 (17.9%) of them lived in towns, and 18 (5.2%) lived in rural areas. Regarding their relationship status, 281 (81.2%) people were single, 65 (18.8%) were in a relationship, and no one was married. Concerning the frequency of their Tinder use, 44 (12.7%) participants used it more than once a day, 56 (16.2%) on a daily basis, 86 (24.9%) more than once a week, 42 (12.1%) used it once a week, 27 (7.8%) every second week, 27 (7.8%) monthly, and 64 (18.5%) used it less frequently than once a month.

Measures

Tinder Use Motivation Scale (TUMS)

For details, see Study 1. In this study, the internal consistencies of the factors were acceptable (αlove = 0.95, αsex = 0.92, αself-esteem = 0.88, and αboredom = 0.78).

Problematic Tinder Use Scale (PTUS)

This scale was developed by Orosz, Tóth-Király, Bőthe, et al. (2016). It contains six items that cover Griffiths’ (2005) model of problematic use. The six components are salience, tolerance, mood modification, relapse, withdrawal, and conflict. Response options ranged from “1 – never” to “5 – always.” In this study, the internal consistency of the PTUS was acceptable (α = 0.75).

Big Five Inventory (BFI) – Hungarian version

The BFI is a 45-item scale created by John and Srivastava (1999). A shorter Hungarian version is available that contains 15 items (three items on each factor) with six being reverse-coded (Farkas & Orosz, 2013). The BFI assesses the personality of the respondent by five factors: openness to arts (e.g., “I see myself as someone who values artistic, aesthetic experiences;” α = 0.86), agreeableness (e.g., “I see myself as someone who is helpful and unselfish with others;” α = 0.60), extraversion (e.g., “I see myself as someone who is outgoing, sociable;” α = 0.74), conscientiousness (e.g., “I see myself as someone who perseveres until the task is finished;” α = 0.56), and neuroticism (e.g., “I see myself as someone who gets nervous easily;” α = 0.75). Respondents have to indicate their level of agreement on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Higher scores on these subscales indicate higher levels of openness, agreeableness, extraversion, conscientiousness, and neuroticism.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 22 and Mplus 7.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2015). To test the associations between the variables, structural equation modeling (SEM) analyses with latent variables were conducted with robust maximum likelihood estimation to examine the relationship pattern between Big Five factors, Tinder motivations, and problematic Tinder use. Following previous applications (Chiorri, Marsh, Ubbiali, & Donati, 2016; Marsh et al., 2010), the Big Five factors were estimated in the exploratory SEM framework (for more details, see Morin, Marsh, & Nagengast, 2013 or Tóth-Király, Bőthe, Rigó, & Orosz, 2017). The same fit indices and guidelines were applied as in Study 1.

Results and Brief Discussion

Table 1 demonstrates the descriptive results with reliability indices. Although several scales have significantly correlated, they all have weak associations. SEM was conducted to examine the relationship patterns between personality traits and problematic Tinder use mediated by Tinder-use motivations. The model had acceptable fit (CFI = 0.941, TLI = 0.928, RMSEA = 0.043, [90% CI = 0.038–0.048]). The strongest predictor of problematic Tinder use was self-esteem enhancement motivation (β = 0.37, p < .001). Furthermore, sex (β = 0.32, p < .001) and love (β = 0.23, p < .001) motivational factors had smaller and positive relationship with problematic Tinder use. Boredom was unrelated to problematic Tinder use (β < 0.02, p = .757). Personality variables did not significantly predict problematic Tinder use. However, agreeableness (β = 0.15, p = .074) and neuroticism (β = 0.13, p = .077) were marginally related to problematic Tinder use.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations of the examined variables (Study 2)

| Range | Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. TUMS love motivation | 1–7 | 3.20 (1.62) | – | ||||||||

| 2. TUMS sex motivation | 1–7 | 2.63 (1.56) | 0.36** | – | |||||||

| 3. TUMS self-esteem enhancement motivation | 1–7 | 2.31 (1.44) | 0.14** | −0.00 | – | ||||||

| 4. TUMS boredom motivation | 1–7 | 4.42 (1.60) | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.24** | – | |||||

| 5. Problematic Tinder Use Scale | 1–6 | 1.94 (0.60) | 0.19** | 0.15** | 0.42** | 0.17** | – | ||||

| 6. BFI extraversion | 1–5 | 3.74 (0.88) | −0.06 | −0.02 | 0.09 | 0.12* | −0.01 | – | |||

| 7. BFI agreeableness | 1–5 | 3.78 (0.72) | 0.16** | −0.07 | 0.15** | 0.09 | 0.17** | 0.12* | – | ||

| 8. BFI conscientiousness | 1–5 | 3.00 (0.76) | 0.05 | −0.18** | −0.02 | −0.17** | 0.04 | 0.06* | 0.10 | – | |

| 9. BFI neuroticism | 1–5 | 2.78 (0.98) | −0.03 | −0.13* | 0.14** | 0.02 | 0.15** | −0.11* | −0.22** | 0.03 | – |

| 10. BFI openness | 1–5 | 3.31 (1.09) | −0.08 | −0.08 | 0.11* | −0.09 | 0.02 | 0.14* | 0.14* | 0.04 | 0.07 |

Note. TUMS: Tinder Use Motivations Scale; BFI: Big Five Inventory; SD: standard deviation.

*p < .05. **p < .01.

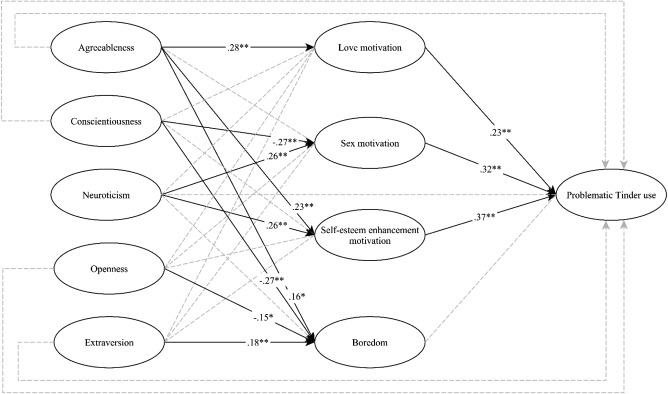

BFI dimensions weakly but significantly predicted Tinder-use motivations. Love motivation was predicted by agreeableness (β = 0.28, p < .001). Self-esteem enhancement motivation was predicted by agreeableness (β = 0.23, p < .010) and neuroticism (β = 0.26, p < .001). Sex motivation was predicted by conscientiousness (β = −0.27, p < .010) and neuroticism (β = −0.16, p < .050). Boredom motivation was positively predicted by extraversion (β = 0.18, p < .050) and agreeableness (β = 0.16, p < .050), and negatively by conscientiousness (β = −0.27, p < .010) and openness (β = −0.15, p < .050). However, it was marginally related to neuroticism (β = 0.15, p = .057). The motivational and personality variables explained 31.7% of the variance of problematic Tinder use (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The mediational model of personality traits, Tinder-use motivations and problematic Tinder use (Study 2). Note. All variables presented in ellipses are latent variables. For the sake of clarity, indicator variables related to latent variables and correlations between the variables were not depicted in this figure. One-headed arrows represent standardized regression weights. The non-significant pathways were not depicted on the figure for the sake of simplicity; *p < .05. **p < .01

Previous studies reported strong associations between low self-esteem and problematic online behaviors as users wish to raise their self-esteem by means of the virtual environment (e.g., Armstrong et al., 2000; Yang & Tung, 2007). According to the present results, the self-esteem enhancing motivation of Tinder use plays an important role in problematic Tinder use. Besides our expectations, love and sex motivations also appeared to be associated with problematic Tinder use. However, in case of these motivations, the links were weaker compared with self-esteem enhancement motivation. In sum, looking for true love, casual sex partners or elevating one’s self-esteem through Tinder use can be sources of developing problematic Tinder use. However, if we consider these motivations of Tinder use, Big Five personality traits did not have any significant direct effect on problematic Tinder use.

Regarding the personality background of Tinder-use motivations, no strong associations between the five traits and the four motivational variables were found. Extraversion was only related to boredom-motivated Tinder use. Tinder seems to provide stimulation for extraverted individuals in monotonous situations, and therefore, it can alleviate their boredom.

Agreeableness was related to love, self-esteem, and boredom motivations of Tinder use. Based on these results, individuals with higher levels of agreeableness are more inclined to use Tinder to find romantic love, to boost their self-esteem, and to cope with boredom. Individuals with high agreeableness perceive themselves as selfless, kind, and tender who are friendly with others. These characteristics can be valuable in online dating situations such as in case of Tinder use. This might be one of the reasons as to why agreeable individuals had higher scores on most of the dimensions of the Tinder-use motivations.

Conscientiousness was negatively related to boredom motivation, indicating that less-conscientious individuals are motivated to use this application to alleviate their boredom. However, individuals with lower level of conscientiousness were also more motivated to use Tinder for finding casual sex partners. In sum, conscientiousness is related to dutifulness, carefulness, and foreseeing, which can be one of the possible explanations why they experience less boredom in general and why they do not prefer ambiguous, spontaneous, and rather unpredictable casual sexual relationships.

Openness was negatively related only to boredom motivation, indicating that less open individuals are less motivated to use this application for alleviating boredom. Presumably, more open individuals can find other activities that reduce the possibility of being bored. It is also possible that individuals with higher level of openness find more curiosity in the application than less open Tinder users.

Neuroticism predicted self-esteem enhancement motivation, indicating that emotionally unstable individuals are more inclined to use Tinder to enhance their self-esteem, because the lack of rejection does not trigger their emotional instability. Furthermore, emotional stability was negatively related to using Tinder for finding a casual sex partner. Moreover, neuroticism was related to the two strongest motivational predictors of problematic Tinder use. These results indicate that being emotionally stable and being able to deal with stress effectively provide lower probability to use Tinder for self-esteem enhancement or for finding casual sex partners, and it can work against the development and maintenance of problematic Tinder use. Besides the cross-sectional nature of this study, the main limitation was not specifically focusing on those broader personality characteristics that can be related to self-esteem enhancement. The following study aimed to overcome this limitation with the inclusion of variables that can be more specific predictors of Tinder-use motivations relative to the Big Five traits.

Study 3 – Self-Esteem Versus Relatedness Need Frustration as Predictors of Problematic Tinder Use

The aim of this study was to investigate the role of more proximal personality-related variables and characteristics than Big Five traits. Considering the role of self-esteem enhancing Tinder motivations in problematic Tinder use (see Study 2), we aimed to examine the role of global self-esteem that can be strongly related to this motivation. Global self-esteem reflects on how someone appraises his or her value. It is a subjective judgment, not necessarily a display of one’s objective talents or accomplishments (Leary & Baumeister, 2000). The stereotype-based notion that Internet dating sites are mostly used by people who have lower levels of self-esteem is not broadly supported by the literature. The majority of these studies have found no difference in self-esteem between those who use Internet dating sites and those who do not (Aretz, Demuth, Schmidt, & Vierlein, 2010; Blackhart, Fitzpartrick, & Williamson, 2014; Gatter & Hodkinson, 2016; Kim, Kwon, & Lee, 2009). However, on the basis of the solid associations between self-esteem enhancing Tinder motivation and problematic Tinder use – although there might be no difference between Tinder users versus non-users – self-esteem restoration motives of Tinder use can make a difference. It is especially true if we consider Valkenburg and Peter’s (2007) social compensation hypothesis, which proposes that low self-esteem individuals date less in person-to-person offline situations and are more inclined in online dating. Building on this theory, we may assume that low self-esteem individuals can use Tinder more frequently than high self-esteem individuals that allow them to develop stronger self-esteem enhancing Tinder-use motivation, which, in turn, can result in higher levels of problematic Tinder use.

Another broader psychological construct that could be a potential predictor of self-esteem Tinder motivation stems from the basic psychological needs theory. According to the self-determination theory (SDT), basic psychological needs serve as nutriments for psychological and physical health and social wellness (Ryan & Deci, 2017). This theory states that there are three basic psychological needs related to this innate human motivation, which, if fulfilled, grants development toward an organized, more coherent and unified functioning (Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013). The first need, competence, refers to the experience of being able to effectively initiate interactions with one’s environment. The second need, autonomy, can be described as the individual’s experience of acting with volition and endorsement. While the third and of major importance in the present case, relatedness, refers to the need of affection and reciprocal care with important others (such as parents, romantic partners, and friends). These needs can be satisfied or frustrated. In case of need satisfaction, the three needs are met, resulting in well-being. However, need frustration appears if the needs are actively thwarted and frustrated, which result in ill-being, psychopathology, or maladaptive functioning (Bartholomew, Ntoumanis, Ryan, Bosch, & Thøgersen-Ntoumani, 2011; Van den Broeck, Ferris, Chang, & Rosen, 2016; Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013). Among the three needs, relatedness satisfaction and frustration appear to be the most relevant ones regarding online dating applications, such as Tinder. It can be expected that if a Tinder user’s relatedness need is frustrated – as a result of the lack of affection, love, or mutual care with significant others – this user can develop stronger self-esteem enhancing motivation in Tinder use than those individuals whose relatedness need is satisfied. Relatedness frustration is expected to lead to stronger inclination in getting positive interpersonal feedback from attractively evaluated individuals to fulfill this frustrated need and Tinder can provide an instantly available source of this sort of need fulfillment. As satisfaction and frustration can be measured in strongly negatively correlated but separate dimensions (Chen et al., 2015), we tested their role in separate models. In sum, in Study 3, we aimed to identify the role of general self-esteem and relatedness satisfaction and frustration as relevant proximal variables in problematic Tinder use by considering the mediating role of Tinder-use motivations.

Methods

Procedure

The study was conducted on an online platform (Qualtrics, Provo, Utah) and the questionnaire was shared in online groups and pages where members’ main aim was to make friends, and find dating partners. The answers were collected in March 2017 and filling out took 15 min on average. Before filling out the questionnaire, participants were informed about the goal of the research and they were reassured of anonymity and confidentiality of their answers. If they agreed to participate and were over 18 years old, a box had to be checked to continue. The first part of the questionnaire encompassed demographic questions, including gender, age, level of education, place of living, job status, and relationship status. The following part contained measurements of global self-esteem, psychological need satisfaction, and Tinder-use motivations.

Participants

Although a total number of 898 respondents were recruited for the study, a high number of participants had to be excluded from the sample, because they either never used Tinder or they did not use it over the past 1 year. Therefore, 298 (female = 177; 59.4%) participants remained in the final sample who were aged between 19 and 65 (Mage = 25.09; SDage = 5.82). About 159 (53.4%) lived in the capital, 37 (12.4%) of them lived in county towns, 71 (23.8%) in towns, and 31 (10.4%) in villages. Regarding their level of education, 26 (8.7%) had a primary school degree, 164 (55%) had a high-school degree, 17 (5.7%) had a vocational degree, 91 (30.5%) had a degree in higher education, while 149 (50%) of them were still enrolled in college or university. Concerning their job status, 104 (34.9%) of them had a full-time job, 58 (19.5%) of them had a part-time job, 41 (13.8%) worked occasionally, and 95 (31.9%) were unemployed. Regarding the relationship status of the participants, 169 (56.7%) people were single, 116 (38.9%) were in a relationship, 4 respondents (1.3%) were engaged, 5 (1.7%) were married, and 4 (1.3%) were divorced.

Measures

Tinder Use Motivational Scale (TUMS)

For details, see Study 1. In this study, the internal consistencies of the factors were acceptable (αlove = 0.95, αsex = 0.87, αself-esteem = 0.87, and αboredom = 0.84).

Problematic Tinder Use Scale (PTUS)

For details, see Study 2. In this study, internal reliability was acceptable (α = 0.71).

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES)

Self-esteem was assessed using the 10-item (e.g., “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself;” α = 0.91) RSES (Rosenberg, 1965; Urbán, Szigeti, Kökönyei, & Demetrovics, 2014). The participants rated responses on a scale of 0 (strongly agree) to 3 (strongly disagree).

Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Need Frustration Scale (BPNSFS)

The Hungarian version of BPNSFS was used to assess psychological need satisfaction and frustration of relatedness (e.g., “I feel that the people I care about also care about me;” αsatisfaction = 0.80, e.g., “I feel excluded from the group I want to belong to;” αfrustration = 0.80) (Chen et al., 2015; Tóth-Király, Morin, Bőthe, Orosz, & Rigó, 2018). The relatedness subscale scale consists of eight items, four of which measures need satisfaction and four which measures need frustration. Respondents were asked to rate each item on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (very true).

Statistical analysis

For data analyses, SPSS version 23 and Mplus 7.3 were used using the MLR estimator. At first, the descriptive statistics were analyzed and correlations between scales and subscales were measured. The proposed model was analyzed using SEM to examine the relationship pattern between global self-esteem, relatedness satisfaction, Tinder motivations, and problematic Tinder use. The same fit indices and guidelines were applied as in Study 1.

Results and Brief Discussion

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations among the examined variables. Overall, all Tinder motivations were moderately and positively related to problematic Tinder use. General self-esteem was weakly and positively related to sex motivation, whereas relatedness satisfaction was weakly related to problematic use and moderately to self-esteem. Relatedness frustration was weakly related to the Tinder-use motivations and moderately to self-esteem and relatedness satisfaction.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlations of the examined variables (Study 3)

| Range | Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. TUMS love motivation | 1–7 | 3.02 (1.62) | – | ||||||

| 2. TUMS sex motivation | 1–7 | 2.53 (1.41) | −0.19** | – | |||||

| 3. TUMS self-esteem enhancement motivation | 1–7 | 2.13 (1.37) | 0.32** | 0.12* | – | ||||

| 4. TUMS boredom motivation | 1–7 | 3.82 (1.74) | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.16** | – | |||

| 5. Problematic Tinder Use Scale | 1–5 | 1.69 (0.56) | 0.33** | 0.20** | 0.55** | 0.26** | – | ||

| 6. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale | 0–3 | 1.82 (0.65) | −0.07 | 0.17** | −0.07 | 0.01 | −0.10 | – | |

| 7. BPNSFS Relatedness Satisfaction Scale | 1–5 | 3.97 (0.83) | 0.02 | −0.06 | −0.15* | −0.02 | −0.19** | 0.42** | – |

| 8. BPNSFS Relatedness Frustration Scale | 1–5 | 1.92 (0.83) | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.27** | 0.04 | 0.29** | −0.50** | −0.67** |

Note. TUMS: Tinder Use Motivation Scale; BPNSFS: Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Need Frustration Scale; SD: standard deviation.

*p < .05. **p < .01.

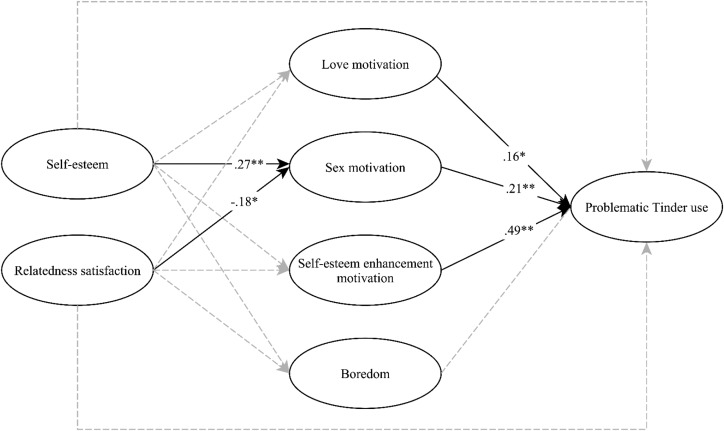

In the first mediational model, the role of relatedness satisfaction and general self-esteem was investigated regarding problematic Tinder use through Tinder-use motivations (Figure 3). The model showed acceptable fit to the data (CFI = 0.922, TLI = 0.913, RMSEA = 0.057, [90% CI = 0.051–0.062]). Regarding the predictors of motivations, sex motivation was positively predicted by general self-esteem (β = 0.27, p < .001) and negatively by relatedness satisfaction (β = −0.18, p < .050). Self-esteem enhancement motivation was negatively predicted by relatedness satisfaction (β = −0.21, p < .001), whereas the other motivations were not predicted by general self-esteem or relatedness satisfaction. Furthermore, three out of the four Tinder-use motivations were significant, positive predictors of problematic Tinder use; self-esteem enhancement motivation (β = 0.49, p < .001) was the strongest predictor followed by sex motivation (β = 0.21, p < .001) and love boredom motivation (β = 0.16, p < .05), whereas boredom was not a significant predictor (β = 0.05, p = .631). The overall explained variance of problematic Tinder use was 39.4%.

Figure 3.

The role of self-esteem and relatedness satisfaction in problematic Tinder use mediated by Tinder-use motivations (Study 3). Note. All variables presented in ellipses are latent variables. For the sake of clarity, indicator variables related to latent variables and correlations between the variables were not depicted in this figure. One-headed arrows represent standardized regression weights. The non-significant pathways were not depicted on the figure for the sake of simplicity. *p < .05. **p < .01

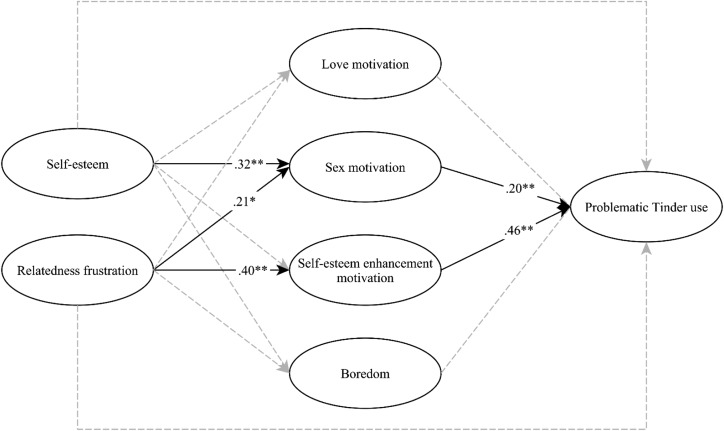

In the second mediational model, the role of relatedness frustration and general self-esteem was investigated regarding problematic Tinder use through Tinder-use motivations (Figure 4). The model showed acceptable fit (CFI = 0.920, TLI = 0.910, RMSEA = 0.058, [90% CI = 0.052–0.063]). Once again, sex motivation was predicted by general self-esteem (β = 0.32, p < .001) and relatedness frustration (β = 0.21, p < .050). Interestingly, self-esteem enhancement motivation was predicted by relatedness frustration (β = 0.40, p < .001). The outcome of problematic Tinder use was predicted by the motivational factors of sex (β = 0.20, p < .010) and self-esteem enhancement (β = 0.46, p < .001), but not the other ones. The overall explained variance of problematic Tinder use was 40.4%.

Figure 4.

The role of self-esteem and relatedness frustration in problematic Tinder use mediated by Tinder-use motivations (Study 3). Note. All variables presented in ellipses are latent variables. For the sake of clarity, indicator variables related to latent variables and correlations between the variables were not depicted in this figure. One-headed arrows represent standardized regression weights. The non-significant pathways were not depicted on the figure for the sake of simplicity. *p < .05. **p < .01

In this study, the main goal was to examine self-esteem- and need satisfaction/frustration-related background of problematic Tinder use. Furthermore, the mediating role of Tinder-use motivations between the predictors of self-esteem and relatedness satisfaction/frustration and the outcome of problematic Tinder use were examined. Self-esteem, relatedness satisfaction, and frustration were not directly associated with problematic Tinder use. Self-esteem predicted positively only one motivational aspect: using Tinder to find casual sexual partners and surprisingly it did not predict self-esteem enhancement motivation. On the other hand, relatedness need frustration positively predicted both the sex and the self-esteem motivations for using Tinder. Finally in the satisfaction model, self-esteem, sex, and love motivations were positively associated with problematic Tinder use. However, the link between love motivation was very weak, which became marginally significant in the frustration model. Therefore, in the frustration model, only two motivations significantly predicted problematic Tinder use: sex and self-esteem enhancement.

This study was only the first step in the identification of the potential background variables behind problematic Tinder use. For this reason, future research should overcome the current limitations (i.e., correlational self-reported data) by conducting longitudinal or experimental studies in which relatedness needs are manipulated. This setting could facilitate the understanding of how relatedness satisfaction could lead to reduced problematic Tinder use. Such experimental research can provide the basis of future interventions focusing on the reduction of problematic Tinder use.

General Discussion

Considering the popularity of online dating (Cacioppo et al., 2013) and the widespread presence of Tinder (Dredge, 2015; Smith, 2016), it appears to be important to examine the psychological mechanisms behind problematic Tinder use, which is based on one of the most popular psychological models of behavioral addictions (Griffiths, 2005; Orosz, Tóth-Király, Bőthe, et al., 2016). The importance of this research stream is also underscored by studies conducted in relation to other online addictions where some motivational factors were related to problematic behaviors, whereas others were not (Billieux et al., 2011; Király et al., 2015). Tinder appears to be different from many “classical” online dating platforms (Whitty, 2008; Whitty & Young, 2016) in terms of precise locatability that promotes immediate dating. Besides this aspect, contrasting to the more classical online platforms, which were optimized to computers, this smartphone application has the advantages of portability, constant availability, and multimediality (Marcus, 2016; Schrock, 2015). For these reasons, the identification of psychological mechanisms as motivations, Big Five traits (John & Srivastava, 1999), self-esteem (Rosenberg, 1965; Urbán et al., 2014), and psychological need satisfaction and frustration (Chen et al., 2015; Tóth-Király et al., 2018) appears to be an adequate inquiry considering state of the art of relevant research in psychological science.

Considering the main results of the present work, among the potential motivational predictors, four factors were examined, namely sex, love, self-esteem enhancement, and boredom motivations. In line with the results of prior studies on problematic online behaviors (e.g., Armstrong et al., 2000; Yang & Tung, 2007), self-esteem enhancement motivation of Tinder use was positively related to problematic Tinder use. Among the motivational variables, self-esteem enhancement had the strongest link to problematic Tinder use, but sex, love, and boredom motivations were also related to it in Studies 2 and 3 as well.

The mediating role of motivations between personality and problematic Tinder use

The strongest motivational dimension that predicted problematic Tinder use was the self-esteem enhancement factor. The present results indicated that individuals who use Tinder to feel more valuable or appreciated by others could be more inclined toward problematic Tinder use. This association is in line with previous studies in which lower self-esteem was related to problematic online activities (Armstrong et al., 2000; Bianchi & Phillips, 2005, Ehrenberg et al., 2008; Ha et al., 2008; Leung, 2008). However, in this case, self-esteem enhancement appeared as a motivational variable, not as the indicator of the level of general self-esteem (see the role of general self-esteem below), as this motivational factor can be similar to feeling empowered by feedback during online dating (Quiroz, 2013).

In case of Tinder, the combination of multiple positive social reinforcements and the lack of explicit rejection – the user can only see matches – can be the sources of this motivation. According to previous studies (James, 2015), for Tinder users, checking matches and messages as immediate positive social feedback appears to be among the most valuable and joyful aspects of self-esteem enhancement. Finally, those individuals who were reportedly emotionally less stable and more unfriendly were more motivated to use Tinder to enhance their self-esteem. Furthermore, in both Studies 2 and 3, self-esteem enhancement motivation was the strongest predictor of problematic Tinder use. Therefore, this association indicated that self-esteem enhancement motivation was a reliable mediator between personality (agreeableness and neuroticism) and need-related (relatedness need frustration) background variables and problematic Tinder use.

Individuals are characterized by sex motivation use Tinder to find casual sex partners. In line with previous studies on online dating (Couch & Liamputtong, 2008), the relevance of this motivational aspect was expected, given that Tinder was advertised as an application of facilitating casual relationships. Having casual sexual partners as a motivation of Tinder use was higher among males than females and it was slightly and positively related to age. More importantly, sex motivation appeared to be a relevant predictor of problematic Tinder use (both in Studies 2 and 3) and a reliable mediator between personality variables, relatedness needs (satisfaction and frustration also), and problematic Tinder use. Therefore, sex motivation can be interpreted as a “mediating hub,” which was predicted by high global self-esteem, emotional instability, carelessness, and relatedness need frustrations, which in turn reliably predicted problematic Tinder use. Therefore, using Tinder for finding casual sex partners can appear to have a complex personality background and it contributes to the development and maintenance of problematic Tinder use.

The love motivation factor was conceptualized on the basis of the triangular theory of love (Sternberg, 1986) including items referring to intimate, passionate, and committed aspects of romantic love. Love motivation was related to both agreeableness and problematic Tinder use. This relationship pattern indicates that individuals who reported themselves as a kind, selfless, and tender person were motivated to find love using Tinder and this motivation can contribute to the development and maintenance of problematic Tinder use. However, compared with sex and self-esteem motivations, the link between love motivation and problematic Tinder use appears to be weaker.

Among Tinder-use motivations, boredom motivation was consistently unrelated to problematic Tinder use. These results suggest that using Tinder to reduce or relieve boredom does not appear to be a risk factor in the development and maintenance of problematic Tinder use.

Personality and need-related background of problematic Tinder use

One of the most important findings of Studies 2 and 3 is that none of the background predictors had a direct association with problematic Tinder use. Basic personality factors, general self-esteem, relatedness satisfaction, and frustration were only related to problematic Tinder use through different Tinder-use motivations. Personality factors appeared to be rather distal predictors, which influence the given behavior through more proximal constructs such as motivations. For these reasons, the present results are in line with more recent theories and results suggesting that it might be erroneous to talk about addictive personality especially if we focus on problematic online behaviors (Griffiths, 2017). According to the present results, we can suppose that personality can influence specific motivations, which in turn, can play a significant role in the development and maintenance of the problematic behavior.

Counterintuitively, general self-esteem was not associated with the motivation of enhancing self-esteem through Tinder use. This result is in line with previous studies (Aretz et al., 2010; Blackhart et al., 2014; Gatter & Hodkinson, 2016; Kim et al., 2009), where self-esteem was unrelated to the use of dating sites. There are some explanations of these associations; however, all of these need further research. First, if users have low self-esteem, then they might not believe that others would like to choose them and swipe them to the right, hence they are not keen to use Tinder to enhance their own global self-esteem. Second, considering an inverse direction of effect between the two variables than in the model, the lack of association can be attributed to the fact that the self-esteem enhancing experience of Tinder use is only temporary and has a relatively small effect on one’s global self-esteem. Third, as negative feedback on Tinder is practically non-existent – users only see their matches, but not those experiences when the other party rejects them – and without this contrasting negative experience, the perceived personal value of “match” is relatively small, which can lead to temporary and very small positive affects, but does not influence the general self-esteem. In sum, as there is no explicit measure for the number of rejections, it cannot decrease one’s global self-esteem. Fourth, it is also possible that users tend to swipe everyone to the right and if they do so, the value of matching conveys much less significance especially regarding one’s general self-esteem. Fifth, as self-esteem enhancement Tinder-use motivation had the lowest mean among other motivations, it is also possible that social desirability can affect the link between low self-esteem and using Tinder for elevating self-esteem. All of these are only possible explanations that should be carefully tested in future studies.

Another finding of this study was related to the SDT and more specifically the satisfaction and frustration of relatedness as one of the basic psychological needs (Deci & Ryan, 2000). When one’s need for relatedness is satisfied, feelings of closeness and intimacy are experienced with others and this person does not feel pressured to pursuit other sources of connectedness and initiate causal relationships on online platforms, such as Tinder, which facilitates dating. On the other hand, when we feel that our basic psychological needs are obstructed or thwarted (such as our findings about relatedness frustration), we directly or indirectly begin to develop coping strategies that could counter the experience of need frustration (Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013). One of the potential coping strategies or mechanisms is related to the development of need substitutes (Ryan & Deci, 2017). As the persistent experience of need frustration could be a foundation for feelings of insecurity, individuals start to search for external indicators of worth that could compensate this feeling. In case of Tinder, popularity and attractiveness are the two extrinsic goals that are quickly achievable via the matches, which could temporarily counteract this negative experience. However, as these goals are of extrinsic sources (rather than intrinsic), their effects are only short-lived. Moreover, if this compensatory behavior underscored by extrinsic goals is sustained, then rigid behavioral patterns could develop as these patterns provide a sense of structure, predictability, and security (Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013) that lacks as a result of need frustration. Finally, a stronger investment in extrinsic goals is often related to problematic behaviors including drug use (Williams, Hedberg, Cox, & Deci, 2000) or anxiety (Sebire, Standage, & Vansteenkiste, 2009). Our results support this notion as relatedness frustration was related to problematic Tinder use through the motivations.

Addressing the issue of overpathologization

Although the present findings about problematic Tinder use and its predictors are promising, it is important to consider the concept of overpathologization (Billieux, Schimmenti, Khazaal, Maurage, & Heeren, 2015; Kardefelt-Winther et al., 2017), which argues that everyday activities are being turned into behavioral addictions. On the basis of the present, non-representative samples, it is not clear that problematic Tinder use affects a large part of the Hungarian population. For avoiding the overpathologization and establishing accurate diagnosis, clinically validated diagnostic tests are needed (Maraz, Király, & Demetrovics, 2015). Considering these suggestions, problematic Tinder use belongs to a group of problematic behaviors that can be less addictive and less prevalent than classical substance addictions. Nevertheless, we suggest that it might be important to consider such specific online problematic behaviors (as in the case of Tinder use) in today’s era in which online activities in general (in terms of time spent online and affective bonds to these activities) gets more and more emphasis in the everyday life.

Limitations

Although the present research is among the first ones to identify Tinder motivations as mediators between broader individual differences and problematic Tinder use, several limitations should be mentioned. As it was mentioned above, none of the samples were representative and the scales were self-reported. As this research used cross-sectional data gathering, causality cannot be inferred from the present results. The examination of the temporal stability of the used measures would be useful in future studies. While a new motivation instrument was constructed, the convergent and discriminant validity of this scale was not tested in any of studies.

Furthermore, additional research could examine the validity of the TUMS in different populations, among younger or older Tinder users. Within the framework of the current research, only cross-sectional studies were carried out, which did not allow the investigation of different life events that could influence Tinder-use motivations. Therefore, a longitudinal design could be fruitful in examining how different motivations change during Tinder use. The internal consistency of the agreeableness and conscientiousness scales of the BFI was not adequate; therefore, it is possible that the low level of internal consistencies might distort the present findings. In addition, it might be important to consider that Tinder motivations can be modulated by self-presentational biases and the motivations can also influence the different forms of self-presentation (Ellison, Heino, & Gibbs, 2006). We aimed to predict problematic Tinder use and not Tinder-use intensity as the outcome variable. However, future studies can examine Tinder-use intensity similarly to Ellison, Steinfield, and Lampe’s (2007) or Orosz, Tóth-Király, and Bőthe’s (2016) Facebook intensity. Furthermore, we believe that PTUS can assess problematic Tinder use, but measures developed on the basis of other addiction models should be developed and tested with these predictors to support the present results. The predictors we used could explain only 31.7% of the variance as it can be seen in Figure 2; however, further research is needed to explore the two third of the not explained variance.

Conclusions

Considering the high number of Tinder users (McHugh, 2015) and the continuously increasing number of smartphone online daters (Goodman, 2014), Tinder – and problematic use of similar geo-located smartphone dating applications – deserves more attention from the scientific community. The present research was one of the first steps in the identification of the motivational, personality, and need-related factors behind the problematic use of geo-located dating applications. Self-esteem enhancement motivation to use Tinder consistently showed an important role in the development and maintenance of problematic Tinder use compared to the effects of personality traits.

Appendix: Tinder Use Motivation Scale

The following statements are related to Tinder use. Please indicate the answer that most applies to you.

| 1 – not true to me at all | 2 – not true to me | 3 – rather not true to me | 4 – somewhat true to me | 5 – rather true to me | 6 – true to me | 7 – absolutely true to me |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I look for an intimate relationship on Tinder. | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

| 2. I consider myself more valuable when I use Tinder than before. | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

| 3. I use Tinder to find a casual partner. | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

| 4. If I’m bored, I use Tinder. | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

| 5. I use Tinder to initiate an intimate relationship with someone. | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

| 6. I use every means necessary to find a casual partner. | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

| 7. I would like to find a committed partner on Tinder. | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

| 8. I feel like I am more valuable after using Tinder than before. | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

| 9. I look for the overwhelming love. | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

| 10. I signed up to Tinder to find a sex partner. | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

| 11. I use Tinder when I am bored during travelling. | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

| 12. I use Tinder because I wish to find deep emotions. | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

| 13. Since I use Tinder, I like myself more. | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

| 14. I look for future partners on Tinder who are easily available for casual relationships. | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

| 15. When the lesson/lecture/work is boring I use Tinder. | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

| 16. I look for a partner on Tinder with whom we can live out our lives together. | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

Scoring: Add the scores of the items of each factor and divide them by the number of items that represent the given factor.

- Love:

1, 5, 7, 9, 12, 16

- Self-esteem enhancement:

2, 8, 13

- Sex:

3, 6, 10, 14

- Boredom:

4, 11, 15

Funding Statement

Funding sources: The study was supported by the Hungarian National Research, Development and Innovation Office (grant numbers: FK124225 and PD116686) and the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (Lendület Project LP2012-36). The sixth author (IT-K) was supported by the ÚNKP-17-3 New National Excellence Program awarded by the Ministry of Human Capacities.

Authors’ contribution

All authors contributed to the study design and concept, data analysis, and interpretation of the data. They also contributed substantially to the manuscript writing and all approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Andreassen C. S., Torsheim T., Brunborg G. S., Pallesen S. (2012). Development of a Facebook Addiction Scale. Psychological Reports, 110(2), 501–517. doi: 10.2466/02.09.18.PR0.110.2.501-517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aretz W., Demuth I., Schmidt K., Vierlein J. (2010). Partner search in the digital age. Psychological characteristics of online-dating-service-users and its contribution to the explanation of different patterns of utilization. Journal of Business and Media Psychology, 1(1), 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong L., Phillips J. G., Saling L. L. (2000). Potential determinants of heavier Internet usage. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 53(4), 537–550. doi: 10.1006/ijhc.2000.0400 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan J., Griffiths M. D. (2017). Social media addiction: What is the role of content in YouTube? Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(3), 364–377. doi: 10.1556/2006.6.2017.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K. J., Ntoumanis N., Ryan R. M., Bosch J. A., Thøgersen-Ntoumani C. (2011). Self-determination theory and diminished functioning: The role of interpersonal control and psychological need thwarting. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(11), 1459–1473. doi: 10.1177/0146167211413125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi A., Phillips J. G. (2005). Psychological predictors of problem mobile phone use. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 8(1), 39–51. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2005.8.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billieux J., Chanal J., Khazaal Y., Rochat L., Gay P., Zullino D., Van der Linden M. (2011). Psychological predictors of problematic involvement in massively multiplayer online role-playing games: Illustration in a sample of male cybercafé players. Psychopathology, 44(3), 165–171. doi: 10.1159/000322525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billieux J., Schimmenti A., Khazaal Y., Maurage P., Heeren A. (2015). Are we overpathologizing everyday life? A tenable blueprint for behavioral addiction research. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(3), 119–123. doi: 10.1556/2006.4.2015.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackhart G. C., Fitzpatrick J., Williamson J. (2014). Dispositional factors predicting use of online dating sites and behaviors related to online dating. Computers in Human Behavior, 33, 113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bőthe B., Tóth-Király I., Zsila Á., Griffiths M. D., Demetrovics Z., Orosz G. (2018). The development of the Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale (PPCS). The Journal of Sex Research, 55(3), 395–406. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2017.1291798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo J. T., Cacioppo S., Gonzaga G. C., Ogburn E. L., VanderWeele T. J. (2013). Marital satisfaction and break-ups differ across on-line and off-line meeting venues. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(25), 10135–10140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222447110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamorro-Premuzic T. (2014). The Tinder effect: Psychology of dating in the technosexual era. The Guardian. Retrieved September 1, 2016, from http://www.theguardian.com/media-network/media-network-blog/2014/jan/17/tinder-dating-psychology-technosexual [Google Scholar]

- Chen B., Vansteenkiste M., Beyers W., Boone L., Deci E. L., Van der Kaap-Deeder J., Duriez B., Lens W., Matos L., Mouratidis A., Ryan R. M., Sheldon K. M., Soenens B., Van Petegem S., Verstuyf J. (2015). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion, 39(2), 216–236. doi: 10.1007/s11031-014-9450-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiorri C., Marsh H. W., Ubbiali A., Donati D. (2016). Testing the factor structure and measurement invariance across gender of the Big Five Inventory through exploratory structural equation modeling. Journal of Personality Assessment, 98(1), 88–99. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2015.1035381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comrey A. L., Lee H. B. (1992). A first course in factor analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Couch D., Liamputtong P. (2008). Online dating and mating: The use of the Internet to meet sexual partners. Qualitative Health Research, 18(2), 268–279. doi: 10.1177/1049732307312832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran P. J., West S. G., Finch J. F. (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 1(1), 16–29. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deci E. L., Ryan R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson E. J. (2014). Tinder and its clones have stalled dating app innovation. The Daily Dot. Retrieved September 1, 2017, from http://www.dailydot.com/technology/tinder-effect-on-online-dating-apps/ [Google Scholar]

- Dredge S. (2015). Research says 30% of Tinder users are married. Business Insider. Retrieved December 10, 2017, from http://www.businessinsider.com/a-lot-of-people-on-tinder-arent-actually-single-2015-5 [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenberg A., Juckes S., White K. M., Walsh S. P. (2008). Personality and self-esteem as predictors of young people’s technology use. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 11(6), 739–741. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison N., Heino R., Gibbs J. (2006). Managing impressions online: Self-presentation processes in the online dating environment. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(2), 415–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00020.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison N. B., Steinfield C., Lampe C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1143–1168. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas D., Orosz G. (2013). The link between ego-resiliency and changes in Big Five traits after decision making: The case of extraversion. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(4), 440–445. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.04.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gatter K., Hodkinson K. (2016). On the differences between Tinder™ versus online dating agencies: Questioning a myth. An exploratory study. Cogent Psychology, 3(1), 1162414. doi: 10.1080/23311908.2016.1162414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M. (2005). A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use, 10(4), 191–197. doi: 10.1080/14659890500114359 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M. D. (2017). The myth of ‘addictive personality’. Global Journal of Addiction & Rehabilitation Medicine (GJARM), 3(2), 1–3. doi: 10.19080/GJARM.2017.03.555610 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman E. (2014). Tinder sparks renewed interest in online dating category. ComScore. Retrieved September 1, 2017, from https://www.comscore.com/Insights/Blog/Tinder-Sparks-Renewed-Interest-in-Online-Dating-Category [Google Scholar]

- Ha J. H., Chin B., Park D., Ryu S., Yu J. (2008). Characteristics of excessive cellular phone use in Korean adolescents. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 11(6), 783–784. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair J. F., Black W. C., Babin B. J., Anderson R. E. (2014). Exploratory factor analysis. Multivariate data analysis, 7th Pearson new international. Harlow, UK: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., Bentler P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- James J. L. (2015). Mobile dating in the digital age: Computer-mediated communication and relationship building on Tinder. Master’s thesis, Texas State University Retrieved September 1, 2017, from https://digital.library.txstate.edu/bitstream/handle/10877/5529/JAMES-THESIS-2015.pdf?sequence=1 [Google Scholar]

- John O. P., Srivastava S. (1999). The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In Pervin L. A., John O. P. (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 102–138). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kardefelt-Winther D., Heeren A., Schimmenti A., Rooij A., Maurage P., Carras M., Edman J., Blaszczynski A., Khazaal Y., Billieux J. (2017). How can we conceptualize behavioural addiction without pathologizing common behaviours? Addiction, 112(10), 1709–1715. doi: 10.1111/add.13763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M., Kwon K. N., Lee M. (2009). Psychological characteristics of Internet dating service users: The effect of self-esteem, involvement, and sociability on the use of Internet dating services. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 12(4), 445–449. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Király O., Urbán R., Griffiths M. D., Ágoston C., Nagygyörgy K., Kökönyei G., Demetrovics Z. (2015). The mediating effect of gaming motivation between psychiatric symptoms and problematic online gaming: An online survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(4), e88. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon J. H., Chung C. S., Lee J. (2011). The effects of escape from self and interpersonal relationship on the pathological use of Internet games. Community Mental Health Journal, 47(1), 113–121. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9236-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary M. R., Baumeister R. F. (2000). The nature and function of self-esteem: Sociometer theory. In Zanna M. P. (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 32, pp. 1–62). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leung L. (2008). Linking psychological attributes to addiction and improper use of the mobile phone among adolescents in Hong Kong. Journal of Children and Media, 2(2), 93–113. doi: 10.1080/17482790802078565 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levine D. (2015). Online dating – The psychology (and reality). New York, NY: Elsevier; Retrieved September 1, 2016, from https://www.elsevier.com/connect/online-dating-the-psychology-and-reality [Google Scholar]

- Ligtenberg L. (2015). Tinder, the app that is setting the dating scene on fire: A uses and gratification perspective. Master’s thesis, Graduate School of Communication Retrieved September 1, 2016, from http://dare.uva.nl/cgi/arno/show.cgi?fid=605982 [Google Scholar]

- Maraz A., Király O., Demetrovics Z. (2015). Commentary on: Are we overpathologizing everyday life? A tenable blueprint for behavioral addiction research: The diagnostic pitfalls of surveys: If you score positive on a test of addiction, you still have a good chance not to be addicted. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(3), 151–154. doi: 10.1556/2006.4.2015.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus S.-R. (2016, June 9–13). “Swipe to the right”: Assessing self-presentation in the context of mobile dating applications. Paper presented at 2016 Annual Conference of the International Communication Association (ICA), Fukuoka, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- Margalit L. (2014). Tinder and evolutionary psychology. TechCrunch. Retrieved from https://techcrunch.com/2014/09/27/tinder-and-evolutionary-psychology/?ncid=rss

- Marsh H. W., Hau K.-T., Grayson D. (2005). Goodness of fit evaluation in structural equation modeling. In Maydeu-Olivares A., McArdle J. (Eds.), Contemporary psychometrics: A festschrift for Roderick P. McDonald (pp. 275–340). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh H. W., Lüdtke O., Muthén B., Asparouhov T., Morin A. J. S., Trautwein U., Nagengast B. (2010). A new look at the Big Five Factor structure through exploratory structural equation modeling. Psychological Assessment, 22(3), 471–491. doi: 10.1037/a0019227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin A. J. S., Marsh H. W., Nagengast B. (2013). Exploratory structural equation modeling. In Hancock G. R., Mueller R. O. (Eds.), Structural equation modeling: A second course (pp. 395–436). Charlotte, NC: Information Age. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh M. (2015). 42 percent of Tinder users aren’t even single. Wired. Retrieved September 1, 2017, from http://www.wired.com/2015/05/tinder-users-not-single [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L. K., Muthén B. O. (1998–2015). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Orosz G., Bőthe B., Tóth-Király I. (2016). The development of the Problematic Series Watching Scale (PSWS). Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(1), 144–150. doi: 10.1556/2006.5.2016.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orosz G., Tóth-Király I., Bőthe B. (2016). Four facets of Facebook intensity – The development of the Multidimensional Facebook Intensity Scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 100, 95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.11.038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orosz G., Tóth-Király I., Bőthe B., Melher D. (2016). Too many swipes for today: The development of the Problematic Tinder Use Scale (PTUS). Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(3), 518–523. doi: 10.1556/2006.5.2016.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiroz P. A. (2013). From finding the perfect love online to satellite dating and ‘Loving-the-One-You’re Near’: A look at Grindr, Skout, Plenty of Fish, Meet Moi, Zoosk and Assisted Serendipity. Humanity & Society, 37(2), 181–185. doi: 10.1177/0160597613481727 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ranzini G., Lutz C. (2016). Love at first swipe? Explaining Tinder self-presentation and motives. Mobile Media & Communication, 5(1), 80–101. doi: 10.1177/2050157916664559 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan R. M., Deci E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York, NY: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Schrock A. R. (2015). Communicative affordances of mobile media: Portability, availability, locatability, and multimediality. International Journal of Communication, 9, 1229–1246. [Google Scholar]

- Sebire S. J., Standage M., Vansteenkiste M. (2009). Examining intrinsic versus extrinsic exercise goals: Cognitive, affective, and behavioral outcomes. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 31(2), 189–210. doi: 10.1123/jsep.31.2.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seefeldt B. (2014). Tinder initiation messages. Chicago, IL: Department of Computer Science, University of Illinois; Retrieved from http://m.benseefeldt.com/content/sites/Tinder/tinder_paper.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Sijtsma K. (2009). Reliability beyond theory and into practice. Psychometrika, 74(1), 169–173. doi: 10.1007/s11336-008-9103-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C. (2016, October). 45 impressive Tinder statistics. DMR. Retrieved December 19, 2016, from http://expandedramblings.com/index.php/tinder-statistics/ [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg R. J. (1986). A triangular theory of love. Psychological Review, 93(2), 119–135. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.93.2.119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tóth-Király I., Bőthe B., Rigó A., Orosz G. (2017). An illustration of the exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM) framework on the Passion Scale. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1968. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tóth-Király I., Bőthe B., Tóth-Fáber E., Hága G., Orosz G. (2017). Connected to TV series: Quantifying series watching engagement. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(4), 472–489. doi: 10.1556/2006.6.2017.083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]