Abstract

Rationale:

Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis (ATIN) in children is most commonly due to allergic drug reactions. In neonates, diagnosis of ATIN is clinically suspected and a kidney biopsy is not routinely performed.

Presenting concern:

A 17-day-old newborn presented with vomiting and dehydration, along with anuric acute kidney injury, severe electrolyte disturbances, hypocomplementemia, and thrombocytopenia. Abdominal ultrasound revealed bilateral nephromegaly and hepatosplenomegaly. The patient was promptly started on intravenous (IV) fluid and broad-spectrum antibiotics. His electrolyte disturbances were corrected as per standard guidelines. The rapid progressive clinical deterioration despite maximal treatment and the unclear etiology influenced the decision to proceed to a kidney biopsy. Histopathological findings revealed diffuse interstitial edema with a massive polymorphic cellular infiltrate and destruction of tubular structures, consistent with severe ATIN. Elements of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) were observed.

Diagnosis:

The clinical presentation combined with imaging and histopathological findings was suggestive of ATIN caused by a severe acute bacterial pyelonephritis.

Intervention:

Methylprednisolone pulses followed by oral prednisolone were administered. Antibiotics were continued for 10 days. The patient was kept on invasive mechanical ventilation and on peritoneal dialysis for 12 days.

Outcome:

His condition stabilized following steroid pulses. His renal function progressively improved, and renal replacement therapy was weaned off. His renal ultrasound normalized. He has maintained a normal blood pressure, urinalysis, and renal function over the past 5 years.

Novel finding:

This case reports a severe presentation of acute bacterial pyelonephritis in a neonate. It highlighted the involvement of complement activation in severe infectious process. Histopathological findings of ATIN and TMA played a crucial role in understanding the physiopathology and severity of the disease.

Keywords: acute kidney injury, tubulointerstitial nephritis, kidney biopsy, newborn

Abrégé

Justification :

La néphrite tubulo-interstitielle aiguë (NTIA) chez l’enfant est le plus souvent attribuée à une réaction allergique aux médicaments. Chez les nouveau-nés, le diagnostic de la NTIA est cliniquement suspecté et une biopsie des reins n’est pas pratiquée de façon systématique.

Présentation du cas :

Un nouveau-né âgé de dix-sept jours pris de vomissements et déshydraté qui présentait une insuffisance rénale aiguë anurique, un grave déséquilibre électrolytique, une hypocomplémentémie et une thrombocytopénie. L’échographie abdominale a révélé une hypertrophie rénale bilatérale ainsi qu’une hépatosplénomégalie. Le patient a rapidement été traité avec des antibiotiques à large spectre par voie intraveineuse (IV), et les déséquilibres électrolytiques ont été corrigés conformément aux lignes directrices normalisées. La détérioration clinique rapide et progressive du patient malgré un traitement maximal et une étiologie incertaine a orienté la décision de procéder à une biopsie rénale. Les résultats histopathologiques ont révélé un œdème interstitiel diffus avec infiltrat cellulaire polymorphe et une destruction des structures tubulaires; des observations cohérentes avec une NTIA grave. Des éléments d’une microangiopathie thrombotique (MAT) avaient également été observés.

Diagnostic :

Le tableau clinique combiné aux résultats histopathologiques et d’imagerie suggérait une NTIA causée par une pyélonéphrite bactérienne grave.

Intervention :

Le traitement a consisté en des injections répétées de méthylprednisolone suivies par l’administration orale de prednisolone. Le traitement aux antibiotiques s’est poursuivi sur une période de dix jours. Le patient a également été maintenu sous ventilation mécanique effractive et sous dialyse péritonéale pendant douze jours.

Résultats :

L’état du patient s’est stabilisé à la suite des injections répétées de stéroïdes; sa fonction rénale s’est progressivement améliorée et la thérapie de remplacement rénal a pu être cessée. L’échographie rénale s’est normalisée. Le patient a maintenu une tension artérielle, des analyses d’urine et une fonction rénale normales au cours des cinq dernières années.

Constatations :

Ce rapport présente un cas grave de pyélonéphrite bactérienne aiguë chez un nouveau-né et a mis en lumière le rôle de l’activation du complément dans un processus infectieux grave. Les observations histopathologiques de la NTIA et de la MAT ont joué un rôle essentiel dans la compréhension de la physiopathologie et de la gravité de la maladie.

What was known before

Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis (ATIN) in children is frequently caused by allergic drug reaction. The diagnosis is usually clinically suspected and kidney biopsy is not required.

What this adds

The clinical presentation of acute bacterial pyelonephritis in a neonate can be severe and is associated with complement activation. Histopathological findings of ATIN can be associated with thrombotic microangiopathy, especially in severe infectious process.

Introduction

Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis (ATIN) is a cause of acute kidney injury (AKI).1,2 Drug-induced ATIN is the most frequent presentation in pediatric population, followed by less common etiologies such as infections and systemic inflammatory diseases.2-4 ATIN is a pathological diagnosis that is usually clinically suspected, but kidney biopsy is not routinely performed unless patients develop AKI of unknown etiology. Its true incidence is thus underestimated.5 In neonates, ATIN has rarely been reported and is usually drug-induced.6 We report the case of 17-day-old boy with an atypical presentation of severe AKI, visceromegaly, and multiple organ failure. The kidney biopsy confirmed an unexpected diagnosis.

Case Report

Clinical History and Initial Laboratory Data

A 17-day-old boy presented with 24-hour history of repetitive vomiting, minimal urine output, and low body temperature (lowest rectal temperature, 34°C; normal range, 36.6°C-38.0°C). He was pale, lethargic, and dehydrated. His vital signs were as follows: heart rate of 160 bpm (normal range, 110-160 bpm), blood pressure of 82/55 mm Hg (normal systolic range, 65-85 mm Hg; diastolic range, 45-55 mm Hg), and respiratory rate of 48/min (normal range, 35-55/min) with normal oxygen saturation. His heart and lung auscultation was unremarkable. He had a soft and nontender abdomen, with palpable hepatosplenomegaly. Mild peripheral edema and petechial lesions over his face, palate, feet, and buttock were observed. He had normal external male genitalia. On presentation, biochemical testing was compatible with severe AKI, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, and metabolic acidosis (Table 1). Moderate leukocytosis and severe thrombocytopenia were noted. Blood cultures were drawn before antibiotics were started. Urine culture was not performed as the patient was anuric. Intravenous (IV) fluid resuscitation (0.9% sodium chloride 20 mL/kg) was initiated along with broad-spectrum antibiotics (ampicillin and cefotaxime). Hyperkalemia was promptly treated with IV 10% calcium chloride (0.2 mL/kg) to stabilize the cell membrane and sodium bicarbonate (2 mmol/kg) before being transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit.

Table 1.

Laboratory Results.

| Result | Normal range | |

|---|---|---|

| Blood | ||

| BUN | 48.8 mmol/L | 1.4-6.2 mmol/L |

| Creatinine | 147 µmol/L | 13-33 µmol/L |

| Sodium | 107 mmol/L | 133-142 mmol/L |

| Potassium | 8.8 mmol/L | 3.4-6.0 mmol/L |

| Chloride | 89 mmol/L | 96-106 mmol/L |

| pH | 7.17 | 7.35-7.5 |

| HCO3 | 12.8 mmol/L | 17-27 mmol/L |

| Total calcium | 2.32 mmol/L | 2.08-2.64 mmol/L |

| Magnesium | 0.88 mmol/L | 0.75-1.15 mmol/L |

| Phosphate | 2.3 mmol/L | 1.56-2.67 mmol/L |

| AST | 0.33 µkat/L | 0.17-0.51 µkat/L |

| ALT | 0.17 µkat/L | 0.17-0.68 µkat/L |

| Albumin | 20 g/L | 23-48 g/L |

| Lactate | 2.0 mmol/L | 0-2.4 mmol/L |

| Ammonia | 18 | <35 µmol/L |

| CRP | 43.9 g/L | <10g/L |

| WBC | 24.9 ×109/L | 7.8-15.91 × 109/L |

| HB | 137 g/L | 100-153g/L |

| Platelets | 16 × 109/L | 160-400 × 109/L |

| RNI | 1.02 | 0.9-1.6 |

| APTT | 37.6 s | 25-35 s |

| Fibrinogen | 3.07 g/L | 1.9-4.3 g/L |

| Ferritin | 510 µg/L | 23-336 µg/L |

| C3 | 0.18 g/L | 0.79-1.52 g/L |

| C4 | 0.02 g/L | 0.16-0.38 g/L |

| Urine | ||

| Leukocytes | >50/hpf | 0-5/hpf |

| Red cell | 20-30/hpf | 0-5/hpf |

| Protein | >3 g/L | Negative |

| Nitrites | Positive | Negative |

| Bacteria | Abundant | Negative |

Note. BUN = blood urea nitrogen; AST = aspartate transaminase; ALT = alanine transaminase; CRP = C-reactive protein; WBC = white blood cell; HB = hemoglobin; APTT = activated partial thromboplastin time.

The patient was born at term from an unremarkable pregnancy, except for maternal systemic hypertension in the third trimester. He was breastfed for 10 days and then switched to infant formula because of feeding difficulties. He was reported to be sleepy and not peeing often since birth. A skin rash over his extremities was observed on days 8 and 15 of life. The patient had not received any medications before presenting to emergency department.

In the first 24 hours, the patient required invasive mechanical ventilation for respiratory failure. He developed a diffuse maculopapular rash. His hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, and metabolic acidosis were corrected as per standard guidelines. He remained anuric and developed generalized edema despite high dose of diuretics (IV furosemide 2.5 mg/kg every 4 hours). His thrombocytopenia (as low as 16 × 109/L) was refractory to platelet transfusions. Few urine drops were sent for culture and urinalysis (Table 1) 8 hours after admission. Urine microscopy did not reveal any casts. His abdominal ultrasound showed bilateral nephromegaly (right and left kidney long-axis measurement of 7.7 and 8.2 cm, respectively, without dilatation of the collective system) with a mild heterogeneous renal parenchyma and hepatosplenomegaly. To exclude a malignant process, a bone marrow biopsy was performed and revealed normal features. Further investigations showed low complement, high C-reactive protein, and high ferritin levels (Table 1). No schistocyte was seen on the blood smear. Plasma lactate dehydrogenase, haptoglobin, pyruvate, ammonia, creatinine kinase, triglycerides, and cortisol levels were normal. Urinary biomarkers of tubular dysfunction were not tested.

In the following 48 hours, the patient developed a disseminated intravascular coagulation, requiring fresh frozen plasma and cryoprecipitate transfusions. Blood and urine cultures as well as viral studies (including parainfluenza, influenza, pneumoviruses, adenoviruses, bocaviruses, rhinovirus, herpex, human herpesvirus-7 [HHV-7], cytomegalovirus [CMV], and varicella-zoster) were negative. Because of severe fluid overload, continuous venovenous hemofiltration was initiated and then discontinued due to hemodynamic instability. The patient’s clinical condition was rapidly and progressively deteriorating despite optimal antibiotic treatment and supportive care. As the clinical presentation was atypical and the etiology of AKI unclear, the decision to perform a kidney biopsy was made.

Pathology

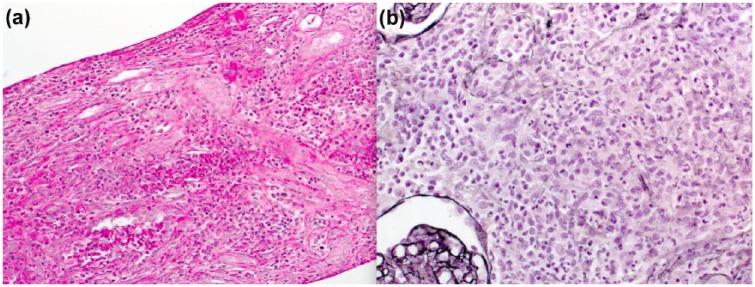

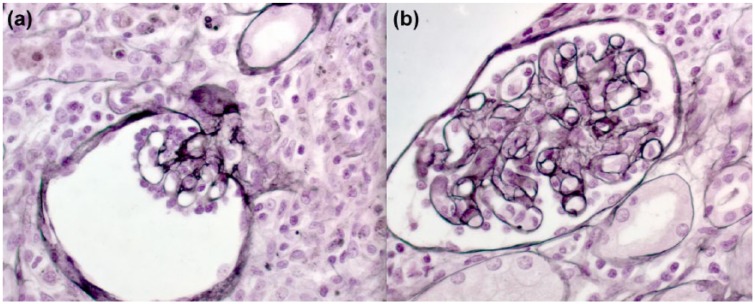

Following optimization of the coagulation profile with blood products, a kidney biopsy was performed under ultrasound guidance and general anesthesia. Light microscopy showed a massive dense multifocal cellular infiltration of neutrophils, eosinophils, and lymphocytes with few plasma cells (Figure 1a). Tubular injuries including tubulitis, breaks of tubular basement membrane, and necrosis of tubular cells (Figure 1) were seen. Neither fibrosis nor tubular atrophy was observed. Glomeruli showed ischemic collapse (Figure 2a) or mesangiolysis and double contours of the glomerular basement membrane (Figure 2b). There was no evidence of endo- or extracapillary proliferation, or cast identified in the glomeruli. Immunofluorescence studies were negative (including albumin, fibrin, IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, and C1q). No microorganism was demonstrated with Gram and Grocott stain. Poor quality of tissue was studied under electronic microscopy, which did not show any glomeruli.

Figure 1.

Histopathological findings on the kidney biopsy.

Note. The kidney biopsy was performed with an 18-gauge needle. (a) Diffuse interstitial edema with multifocal and polymorphic cellular infiltrate, and tubulitis (periodic acid-Schiff stain). (b), Tubular injuries including tubulitis, breaks of tubular membrane, and necrosis of tubular cells (Silver Jones stain).

Figure 2.

Features of thrombotic microangiopathy.

Note. The Silver Jones stain showed (a) ischemic glomerulus and (b) double contour of the glomerular basement membrane and mesangial edema.

A skin biopsy was performed on areas affected by the maculopapulous rash. It revealed edema of the papillary dermis with mild superficial perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and neutrophils. Few foci of extravasated red cells were observed. The epidermis was normal. These findings were suggestive of an urticarial lesion.

Diagnosis

Histopathological findings were consistent with a severe ATIN as well as some features of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), including mesangiolysis and double contouring of the glomerular basement membrane. Neutrophil infiltration originating from renal tubule pointed toward an infectious process originating from the renal tubules. The severity of the inflammatory process was reflected by the significant renal parenchyma destruction. Histopathological findings were consistent with an acute pathological process. The patient’s clinical presentation combined with biochemistry abnormalities (including hypocomplementemia), imaging, and histopathological findings was suggestive of acute bacterial pyelonephritis. Skin biopsy findings showed an inflammatory process suggesting urticarial-like lesion, which can be seen with ATIN.1,2

Clinical Follow-up

The histopathological findings prompted the initiation of IV methylprednisolone pulses (10 mg/kg/day on days 5, 6, and 7), followed by oral prednisolone (2 mg/kg/day).7 Antibiotics were given for 10 days. Peritoneal dialysis was initiated to help fluid management. His condition stabilized following the steroid pulses and then progressively improved with normalization of his renal function over several days. Extended investigations (including antinuclear, anti–double stranded DNA [dsDNA], anti-histone, anti-sjögren’s-syndrome-related antigen A (SSA), anti-sjögren’s syndrome type B (SSB), antiparietal cell, and anti–smooth muscle antibodies and lymphocyte immunophenotyping) were normal. Cytogenetic analyses were unremarkable (normal Comparative Genomic Hybridization (CGH), karyotype 46XY). The patient was extubated and peritoneal dialysis discontinued after 12 days. His hematology and biochemistry profile (including his complement) normalized. Oral prednisolone was slowly weaned and then discontinued after 12 weeks.

At 1-month follow-up, the patient had a normal renal function. His follow-up renal ultrasound showed a left pelviectasis (described by the radiologist but no measurement given) with a left thin and slightly heterogeneous renal parenchyma. Left grade III vesicoureteral reflux was diagnosed on voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG). At 10-month follow-up, renal scintigraphy with dimercaptosuccinic acid revealed normal kidney function, without scarring. His renal ultrasound and VCUG normalized at the 18-month follow-up. He has maintained a normal blood pressure, urinalysis, and renal function over the past 5 years.

Discussion

This report describes an atypical presentation of AKI with unexpected findings of severe ATIN and TMA on the kidney biopsy. ATIN is an immune-mediated AKI found on 3% to 7% of kidney biopsies in children.2,8 Antibiotics and non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are the most common etiologies (70%-85%).2,3,9 Urinary tract infection (UTI) and bacteremia are the main culprits in 10% to 15% of cases.2,3,9 Viral and parasitic infections are occasionally reported.2,3 Immune processes such as immune complex deposition and cell-mediated or antibody-mediated diseases have been described. Idiopathic, metabolic, hereditary, and obstructive causes are rarely reported.2,5 Histopathological findings of ATIN include diffuse interstitial edema with cellular infiltrate (lymphocytes, monocytes, macrophages, plasma cells).5,10 Eosinophils or granuloma can be observed depending on the cause.10 Inflammation may extend into tubular walls. Glomeruli and vessels are usually spared, but may be involved with severe inflammation.10 Even if immunofluorescence studies are usually negative, granular deposition of complement in tubular membranes can be observed.10

The sepsis-like presentation of the patient suggested by leukocytosis, elevated C-reactive protein, abnormal urinalysis, and histopathological findings on the kidney biopsy was in favor of ascending UTI despite negative urine culture (broad-spectrum antibiotics started before the urine sample was obtained).11 The histopathological findings showed severe ATIN. The presence of dense neutrophil infiltrate reflected an active infectious process. Features of TMA were atypical and unexpected, especially in context of normal hemoglobin, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and haptoglobin. Severe intrarenal inflammation may have caused severe endothelial damage and thus the presence of TMA on the kidney biopsy. The absence of granuloma was inconsistent with the diagnosis of tuberculous pyelonephritis.10 Chronic pyelonephritis was excluded as tubular atrophy, glomerular sclerosis, or interstitial fibrosis was not observed.10

Given the sepsis-like presentation, bacteremia was suspected but not found. It may be explained by an intermittent bacteremia, a finding well described in different settings including UTI.11 In a retrospective study assessing the concordance of UTI and positive blood culture in infants aged less than 121 days, 13% of patients had UTI and microbiologically proven bacteremia.12 In our patient, the infection-induced inflammation was likely the predominant clinical feature.

Other noninfectious etiologies were considered. The negative history for drug intake along with the absence of plasma cells and low percentage of eosinophils on the kidney biopsy was not in favor of a drug-induced ATIN.4 Granulomatous interstitial nephritis and granulomatous diseases were eliminated, as the histology did not reveal any granuloma or tubular crystals.13 The presence of a skin rash, thrombocytopenia, proteinuria, hypocomplementemia, and AKI were suggestive of neonatal lupus. The histopathological findings were, however, not consistent with this diagnosis. The negative inflammatory workup was not in favor of lupus (negative antinuclear, anti-DNA, anti-SSA, and anti-SSB antibodies). Few biochemistry and hematological abnormalities were suggestive of TMA, including thrombocytopenia, proteinuria, and AKI. A neonatal atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome was suspected, but visceromegaly, normal hemoglobin, normal LDH, and normal haptoglobin were not consistent. Histiocytosis and malignancy were eliminated based on renal biopsy findings and normal bone marrow biopsy. Acute renal dysfunction, heavy proteinuria, and hypocomplementemia are seen in IgG4-related ATIN.14 IgG4 study was not performed on the kidney biopsy and plasma IgG4 not measured. IgG4 disease has been described in adulthood, typically mid-age.14 Normal IgG, absence of eosinophilia, and negative antinuclear antibodies were not consistent with this diagnosis.15,16 The absence of granules and inclusion bodies within the macrophages excluded malakoplakia.17 Malakoplakia is characterized by a non-neoplastic infiltration of foamy macrophages resulting from abnormal intracellular processing of engulfed bacteria and macrophages containing granules or Michaelis-Gutmann bodies.

The hypocomplementemic profile was atypical. The low C3 and C4 levels (which normalized 15 days after admission) reflected a transient activation of the complement system. The complement system has a crucial role in the innate defense against microorganisms.18 Temporary insufficiency of complement activity related to complement protein consumption has been described with infections. Low serum C3 values are typically related to bacterial infection.18 Low serum C4 values involve anomalies in the classical pathway and may be related to predisposing conditions, which in the case of our patient was unknown.18 This hypocomplementemic state is consistent with a severe infectious process, such as a severe bacterial pyelonephritis.

Acute pyelonephritis in native kidneys rarely causes AKI, unless it is bilateral with a known urinary tract abnormality or when it is associated with sepsis. The diagnosis of urosepsis is clinical and kidney biopsy is not required. In the current report, the kidney biopsy was performed because of the atypical presentation. The role of corticosteroids in the treatment of ATIN is controversial in children.7 Corticosteroids were administrated after more than 72 hours of IV antibiotics. Administration of corticosteroids contributed to the recovery of the ATIN and potentially helped to treat TMA.19,20 Even if we think that corticosteroids helped the patient, the role of steroid therapy in ATIN has stayed controversial with no prospective trial.

ATIN has been rarely reported in neonates. One report describes a 3-week-old baby with drug-induced ATIN (cefotaxime and gentamicin).6 No kidney biopsy was performed. The patient recovered upon discontinuation of antibiotics, without requiring dialysis. For our patient, the kidney biopsy guided the management and led to a successful course. It has helped to understand the physiopathology of the disease and the potential severity of a UTI-induced ATIN in neonates.

Conclusion

We described an atypical presentation of severe ATIN induced by acute pyelonephritis and complicated by severe AKI requiring renal replacement therapy. It highlights the involvement of the complement activation within an infectious process. This case recalls the importance of obtaining blood and urine cultures before starting any antibiotics. Histopathological findings played a crucial role in understanding the physiopathology and the severity of the disease. Severe ATIN can be associated with TMA especially in severe infectious process. Proceeding to a kidney biopsy in a neonate has non-negligible risks and it should be considered when investigations are nonconclusive and atypical features are present.

Footnotes

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: Informed consent was obtained from the legal guardian of the patient described in this case report.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Andreoli SP. Acute kidney injury in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24(2):253-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ulinski T, Sellier-Leclerc AL, Tudorache E, Bensman A, Aoun B. Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27(7):1051-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Praga M, Gonzalez E. Acute interstitial nephritis. Kidney Int. 2010;77(11):956-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Perazella MA, Markowitz GS. Drug-induced acute interstitial nephritis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2010;6(8):461-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Raghavan R, Eknoyan G. Acute interstitial nephritis—a reappraisal and update. Clin Nephrol. 2014;82(3):149-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Essid A, Allani-Essid N, Rubinsztajn R, Estournet B, Bataille J. [A neonatal case of immunoallergic acute interstitial nephritis]. Arch Pediatr. 2010;17(11):1559-1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jahnukainen T, Saarela V, Arikoski P, et al. Prednisone in the treatment of tubulointerstitial nephritis in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28(8):1253-1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lanewala A, Mubarak M, Akhter F, Aziz S, Bhatti S, Kazi JI. Pattern of pediatric renal disease observed in native renal biopsies in Pakistan. J Nephrol. 2009;22(6):739-746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baker RJ, Pusey CD. The changing profile of acute tubulointerstitial nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19(1):8-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brodsky SV, Nadasdy T. Acute and chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis. In: Jennette JC, Olson J, Silva FG, D’Agati VD. eds. Heptinstall’s Pathology of the Kidney, vol. 2, ch. 25, 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015: 1111-1156. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wagenlehner FM, Lichtenstern C, Rolfes C, et al. Diagnosis and management for urosepsis. Int J Urol. 2013;20(10):963-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Downey LC, Benjamin DK, Jr, Clark RH, et al. Urinary tract infection concordance with positive blood and cerebrospinal fluid cultures in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Perinatol. 2013;33(4):302-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Joss N, Morris S, Young B, Geddes C. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(2):222-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stone JH, Zen Y, Deshpande V. IgG4-related disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(6):539-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Deshpande V, Zen Y, Chan JK, et al. Consensus statement on the pathology of IgG4-related disease. Mod Pathol. 2012;25(9):1181-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Salvadori M, Tsalouchos A. Immunoglobulin G4-related kidney diseases: an updated review. World J Nephrol. 2018;7(1):29-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Honjo K, Sato T, Matsuo M, Miyazaki S, Tomiyoshi Y. Renal parenchymal malakoplakia in a four-week-old infant. Clin Nephrol. 1997;47(5):341-344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carroll MV, Sim RB. Complement in health and disease. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011;63(12):965-975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gonzalez E, Gutierrez E, Galeano C, et al. Early steroid treatment improves the recovery of renal function in patients with drug-induced acute interstitial nephritis. Kidney Int. 2008;73(8):940-946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Prendecki M, Tanna A, Salama AD, et al. Long-term outcome in biopsy-proven acute interstitial nephritis treated with steroids. Clin Kidney J. 2017;10(2):233-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]