Abstract

Introduction:

Transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) aims at complete resection of all the visible tumors. Existing guidelines recommend restage TURBT in all patients with T1 and high-grade tumors, to avoid under-staging. However, restage TURBT may not be plausible/feasible at all the times. This study was performed with an aim to better define the utility of restage TURBT in a tertiary care hospital of India.

Methods:

Patients with high grade/T1 tumors at the first TURBT were prospectively enrolled. Their demographic profile, previous cystoscopic findings, and histological reports were recorded. The primary objective was to assess the tumor detection and stage up-migration rates at restage TURBT. The secondary objectives was to identify factors predicting presence of tumor at restage TURBT. Patients were followed up to detect recurrence and progression for a minimum of 3 months.

Results:

Of 128 prospective patients’ enrolled, 29 patients were lost to follow-up and 11 patients did not undergo restage. A total of eighty-eight patients underwent restage TURBT of which twenty-eight patients (31.8%) had tumor at their second TURBT with five of these patients being upstaged to T2. The risk of having a tumor at restage was significantly higher in patients with solid tumors (56.2% vs. 26.4%, P = 0.02, 95% confidence interval: 0.035–0.024) but was independent of the tumor size (P = 0.472), number of growths (P = 0.267), grade of tumor (P = 0.441), presence or absence of muscle at the initial TURBT (P = 0.371) and place of initial TURBT (P = 0.289). There was a significant difference in the recurrence and progression rates in patients who had tumor at restage as compared to those who did not (recurrence; 33.3% and 23.8%, P = 0.022, respectively vs. progression; 11.1% and 3.7% respectively, P = 0.07; mean follow-up = 10.8 months).

Conclusions:

We conclude that restage TURBT is necessary in patients with solid looking tumors and the presence of tumor at restage confers a higher risk of recurrence and progression.

INTRODUCTION

Transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) aims at completely resecting all the visible tumors, whenever feasible. This provides histological staging and grading to classify tumors as nonmuscle invasive or muscle invasive. The treatment and outcomes of these two histopathological stages are entirely different. However, in certain situations such as high-grade superficial disease, there is a possibility of inadequate/improper staging of the tumor. Persistent disease after resection has been observed in 33%–55% of the patients with T1 tumors and in about 41.4% of those with Ta high-grade tumors.[1,2,3,4,5] This is true even if detrusor muscle was included but not invaded at the initial TURBT especially if the histopathology was high grade T1. The likelihood of upstaging to T2 at second resection of an initially T1 tumor ranges from 4% to 25%, and increases to 45% if no muscle was seen in the initial resection specimen.[6] Hence, both the European Association of Urology (EAU) and American Urological Association guidelines recommend restage TURBT in all T1 as well as all high-grade tumors. The problem of restage TURBT are logistics, cost of repeat surgery and the complications associated with TURBT, such as bladder perforation and stricture. Moreover, restage may not be performed in the stipulated time because of lack of OR slot availability in public hospitals or poor compliance of patients. As the symptoms resolve, some patients tend to ignore advice or become hesitant to undergo second surgery within a short span. These patients either avoid the surgery or are lost to follow-up. These problems may be further compounded by resource constraints, typical to a tertiary care setup in India. Hence, there is a need to strongly rationalize the role of restage TURBT in resource constraint setup and to identify the tumor characteristics which can guide the requirement/exemption for restage TURBT.

METHODS

This was a prospective observational study performed with an aim of analyzing the utility of restage TURBT at a tertiary care center. The primary objective was to assess the tumor detection rate and change in stage after restage TURBT. The secondary objectives were to find the factors predicting recurrent tumors at restage TURBT, association of recurrence and progression in restage TURBT and the complications associated with restage TURBT. Disease progression was taken as upstaging or upgrading of the tumor in the follow-up period either detected by radiological investigation or by surgical resection and final HPE.

Study protocol

All patients with proven histological diagnosis of nonmuscle invasive urothelial cancer with either high grade or T1 cancers on histopathology were enrolled. The study duration was from July 2014 to December 2015. During initial cystoscopy, the operative details such as the number of lesions, solid or papillary configuration of lesions and the site of lesions were mapped and recorded. TURBT at our center was performed using a 26 Fr resectoscope and monopolar cautery (settings 70 for pure cutting and 30 for coagulation on fulguration mode). After complete TURBT, a deep biopsy from the base of the tumor was taken. The TURBT chips and the deep biopsy were sent separately. The data of patients in which TURBT was performed at a peripheral center was retrieved from the operative notes and those with incomplete data were excluded. Restage TURBT was advised at 4–6 weeks from initial TURBT as per the EAU guidelines. The cystoscopic findings were recorded during the restage TURBT similar to that at the initial TURBT. In patients with no obvious tumors, resection of the tumor bed was performed and sent for analysis. The histopathology reports of all patients were recorded. Post restage, the patients were then managed by a standard treatment protocol and follow-up. The complications of restage TURBT and recurrences and progression were recorded in the follow-up. The follow-up data of patients who could not undergo restage was maintained and analyzed separately.

Statistical analysis

The analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS STATISTICS (version 22.0, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp, USA). Continuous data was evaluated in mean, median, standard deviation, and categorical data in percentages. Paired t-test and unpaired t-test were applied for dependent and independent data variables of parametric data, respectively, and Wilcoxon signed rank test was applied to compare the nonparametric data. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards laid down by the Helsinki Declaration (modified in 2000) and Indian Council of Medical Research guidelines (1994). Appropriate ethical boards approved this prospective study.

RESULTS

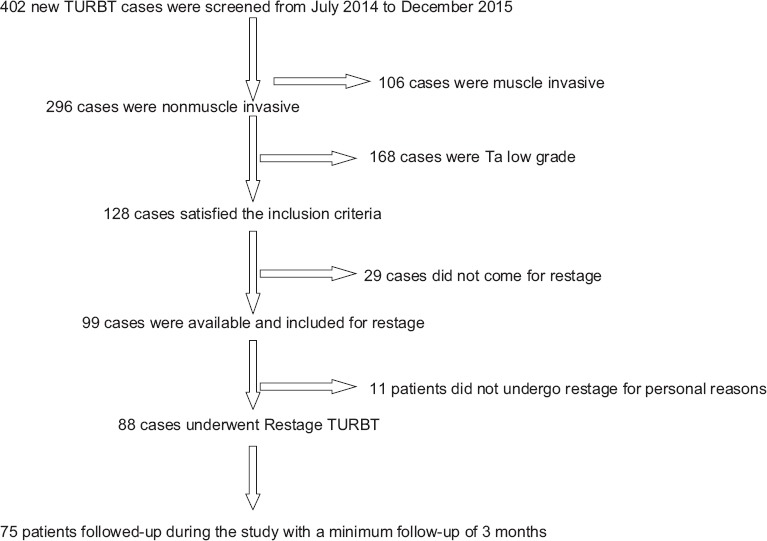

One hundred and twenty-eight patients satisfied the inclusion criteria as per EAU guidelines for restage (T1 or high grade). Sixty-three patients had T1 high grade, 58 patients had T1 low grade, and seven patients had Ta high-grade tumors. Twenty-nine patients were lost to follow-up, of the remaining 99 patients, 11 patients did not undergo restage for personal reasons. A total of 88 patients underwent restage TURBT, 72 patients within 4–6 weeks, and 16 patients between 6 to 12 weeks of the initial TURBT. The 11 patients who refused restage were under regular follow-up with check cystoscopy at 3 monthly intervals. The study cohort distribution is shown in Figure 1. The mean age of the 88 patients was 56.4 years (range 15–85 years) and fourteen (15.9%) of them were females. The findings of initial TURBT and patient characteristics were shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow

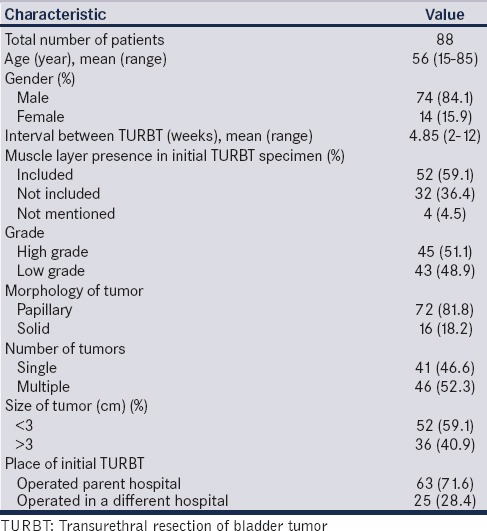

Table 1.

Primary characteristics of patients who underwent restage transurethral resection of bladder tumor

Primary outcomes

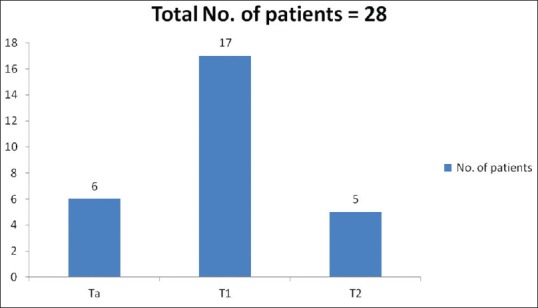

Tumor was detected in 28 patients (31.8%) during restage TURBT, of which 23 patients had noninvasive disease. The stage distribution after restage TURBT is shown in Figure 2. Of these 23 patients, tumor was present at the same site in 21 patients (91.3%) and at different site in two patients (8.7%). All the tumors were <3 cm in size, eighteen patients (78.2%) had single lesion and five patients (21.8%) had multiple growths. In seventeen patients (73.9%) the recurrence was of same stage (T1), in six (26.1%) it was of lower stage (Ta) and stage up-migration to muscle invasive disease (T2) was found in five cases (17.8%). In these five who had muscle invasive disease, deep muscle was not seen at the initial TURBT specimen in only one case.

Figure 2.

Stage distribution after re-stage

Secondary outcomes

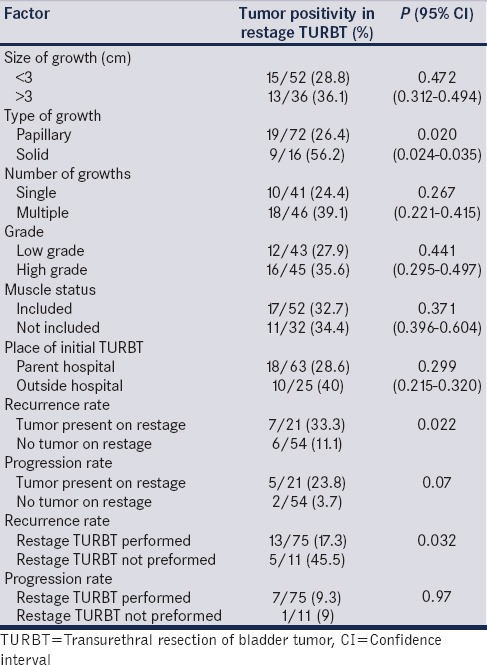

We assessed various tumor characteristics of the primary TURBT which could preict presence of tumor at restage. Patients with solid growths at the initial TURBT had a significant chance of the presence of tumor at restage TURBT (P = 0.02) as compared to those with papillary growths. Other features such as presence of multiple growths versus single growth, size less than versus > 3 cm, TURBT performed at peripheral center versus in the institute were comparable. Histopathological features of the primary TURBT, such as grade and presence or absence of deep muscle at the initial TURBT did not have any significant association with presence of tumor at restage [Table 2].

Table 2.

Analysis of factors affecting tumor positivity in restage transurethral resection of bladder tumor

Follow-up evaluation for recurrence and progression was available for 75 patients (5 upmigrated to T2 disease and underwent radical cystectomy and 8 were lost to follow-up). Of these 75 patients, 21 patients had tumor at restage and 54 did not. The median follow-up period was 10 months (3–21). Thirteen out of 75 patients (17.3%) had tumor recurrence during the follow-up and he mean recurrence period was 3.3 months (range 1–6 months). Of these 13 recurrences, 7 patients had tumor at restage and 6 did not. Seven out of 75 patients (9.3%) had progression of the disease (three had the grade up-migration and four had upstaging). Out of 7 progressions, 5 patients had tumor on restage and 2 did not. The recurrence and progression rates of those who had tumor at restage TURBT were 7/21 (33%) and 5/21 (23.8%) respectively, whereas they were 6/54 (11.1%) and 2/54 (3.7%) respectively for those who did not have tumor. There was statistically significant difference in recurrence and progression between two groups [P = 0.022 and 0.07 respectively; Table 2]. Eleven patients who did not undergo restage TURBT and were on follow-up with check cystoscopy. Five of these patients had recurrence and one had progression. There was a significant difference in the recurrence rate (17.3% vs. 45.5%, P value = 0.032) but not in the progression rate (9.3% vs. 9%, P value = 0.97) between those who had undergone restage TURBT and those who did not.

Overall 10% of patients had one or more complications. None of the patients had a major complications such as bladder perforation or severe bleeding requiring re-interventions. Few patients had minor complications related to spinal anesthesia in the form of postspinal headache.

DISCUSSION

Managing T1 lesions and high-grade lesions by a single TURBT is challenging. Guidelines state that restage TURBT is essential because of high risk of recurrence and progression. Restage TURBT has shown to be effective in staging the disease appropriately and thereby prognosticating it better. It also has shown that by early detection and resection of residual tumor restage TURBT reduces the risk of recurrence and progression. In an Indian setup, where the resources are limited compared to the patient population, there is always a dilemma regarding this second surgery. At times, it is very difficult to convince a patient to undergo second surgery when he is symptom free. It is an economic burden to him as well as adds to the health care costs of the nation. Hence, the question is whether restaging is necessary or is beneficial? And which patients will benefit from such an intervention the most.

The oncological benefit has been clearly shown in our study. Out of the 88 patients who underwent restage TURBT, 28 patients (33.3%) had residual disease and there was stage upmigration to T2 in 5.5% of patients. This is in accordance to already published literature wherein about one-third of patients would have residual disease detected on restage. The presence of muscle in the specimen of initial TURBT decreases the residual tumor rate at the second TUR.[7] In a study by Herr et al,[8] patients who did not have muscle in the initial TURBT had higher chances of having a residual tumor at restage sa compared to those who had muscle layer (49% vs. 14%). In our study, the presence of muscle specimen in the initial TURBT did not significantly affect the tumor presence on restage TURBT (33.3% vs. 38.5%, P = 0.315). These findings defy the common notion that restage TURBT has no value if muscle was included in the specimen. None of the patients had major complications such as bladder perforation or severe bleeding. Thus, restaging seems essential and safe. We can extrapolate these findings to all kinds of population and conclude that restaging is beneficial even in the developing countries.

The second question is what features at the initial TURBT predict the presence of tumor at restage thus making restage TURBT mandatory. Only the presence of a solid tumor growth at initial TURBT was associated with higher chances of finding a tumor at restage (56.2% vs. 26.4%, P = 0.020). Characteristics such as grade of the tumor and the size of the tumor did not significantly affect the outcomes of restage surgery. Similar observations about the number of tumors was made in another study performed at CMC Vellore,[9] where they identified solitary papillary lesions as a subgroup where second TUR is avoidable. We believe that restage could be specifically targeted to patients with these findings on initial CPE, thereby avoiding unnecessary surgeries and reducing health care costs.

Logically, the quality of initial TURBT should affect the residual tumor rates. Ark et al.,[10] compared the incidence of under-staging when the initial TURBT was performed at their institute versus at an outside hospital. However, there was no statistically significant difference in under-staging based on the place of initial TURBT (32.8% vs. 67.2%). We also did not find significant difference between those who had undergone initial TURBT in our institute or elsewhere. Thus, even when the initial TURBT is performed in other hospitals, the incidence of tumor at restage may be low when a careful complete resection is performed.

Third to addresses the question that does restaging TURBT helps in reducing the disease progression? We followed up these patients for recurrence and progression. The mean follow-up period was 10.8 months. The standard treatment protocol for managing nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) as per risk stratification of EAU was followed. The recurrence and progression rates were 17.3% and 9.3%, respectively. The recurrence rate for those who had tumor at the restage was significantly higher than the recurrence rate in those who did not (33.3% vs. 11.1%, P = 0.022). Thus, the presence of tumor at the restage implies high chances of recurrence at follow-up. This may be due to aggressive tumor biology. In a similar study by Shim et al.,[11] 29 patients with T1 high grade disease underwent restage TURBT and 22 of these were found to have residual tumor. There were total of 9 recurrences during followup after restage TURBT, 7 of which were in the group that had residual tumor at restage. Progression occurred in four patients within 2 years, all of whom had residual cancers at restage. The recurrence free survival at 3 years in residual tumor group was 68.6% as compared to 50% in the group without residual tumor (P = 0.5), Progression occurred in 4 patients, all in the residual tumor group. Thus authors recommended routine restage TURBT in T1 high grade tumors. In the current study, the recurrence rates when compared between those who had residual tumor at restage and those who did not were 33% vs 11.1% and the progression rates were 23.8% vs 3.7% (P = 0.07). Hence, the presence of tumor at restage is a risk factor for disease recurrence and progression.

Fourth what happens to patients who do not undergo restage TURBT? Of the patients who did not undergo restage TURBT but underwent regular check cystoscopy, 5 of the 11 (45.5%) had recurrence and 1 patient (9.1%) had disease progression. On comparing them, with those who underwent restage TURBT, there was a significant difference in recurrence rate (45.5% vs. 17.3%, P = 0.032) but the progression rate was similar t (9.1% vs. 9.3% P = 0.97). However, since the study did not aim to compare these two groups and the groups are discordant in sample size, a realistic conclusions cannot be made.

Limitation

The study has some limitations, 43.75% of eligible cohort did not or could not undergo restage TURBT in the stipulated timeframe, thus accounting for loss of a sizeable number of eligible patients, which might have affected the results. About 18% of the patients were lost to follow-up. Also, the initial TURBT and restage TURBT were not performed by the same surgeon. Despite these limitations, our study provides insight into rationality of doing TURBT in a specified group of NMIBC patients.

CONCLUSIONS

We conclude that restage TURBT is necessary in patients with solid bladder tumors. The presence of tumor at restage confers a higher risk of recurrence and progression. Poor patient compliance for a restage TURBT remains a matter of concern.

Footnotes

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grimm MO, Steinhoff C, Simon X, Spiegelhalder P, Ackermann R, Vogeli TA, et al. Effect of routine repeat transurethral resection for superficial bladder cancer: A long-term observational study. J Urol. 2003;170:433–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000070437.14275.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jahnson S, Wiklund F, Duchek M, Mestad O, Rintala E, Hellsten S, et al. Results of second-look resection after primary resection of T1 tumour of the urinary bladder. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2005;39:206–10. doi: 10.1080/00365590510007793-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Divrik RT, Yildirim U, Zorlu F, Ozen H. The effect of repeat transurethral resection on recurrence and progression rates in patients with T1 tumors of the bladder who received intravesical mitomycin: A prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Urol. 2006;175:1641–4. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)01002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lazica DA, Roth S, Brandt AS, Böttcher S, Mathers MJ, Ubrig B, et al. Second transurethral resection after ta high-grade bladder tumor: A 4.5-year period at a single university center. Urol Int. 2014;92:131–5. doi: 10.1159/000353089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasdev N, Dominguez-Escrig J, Paez E, Johnson MI, Durkan GC, Thorpe AC, et al. The impact of early re-resection in patients with pT1 high-grade non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Ecancermedicalscience. 2012;6:269. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2012.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herr HW, Donat SM. Quality control in transurethral resection of bladder tumours. BJU Int. 2008;102:1242–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shen YJ, Ye DW, Yao XD, Zhang SL, Dai B, Zhu YP, et al. Repeat transurethral resection for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Zhonghua wai ke za zhi [Chinese journal of surgery] 2009 May 15;47:725–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herr HW. The value of a second transurethral resection in evaluating patients with bladder tumors. J Urol. 1999;162:74–6. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199907000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katumalla FS, Devasia A, Kumar R, Kumar S, Chacko N, Kekre N, et al. Second transurethral resection in T1G3 bladder tumors-selectively avoidable? Indian J Urol. 2011;27:176–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.82833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ark JT, Keegan KA, Barocas DA, Morgan TM, Resnick MJ, You C, et al. Incidence and predictors of understaging in patients with clinical T1 urothelial carcinoma undergoing radical cystectomy. BJU Int. 2014;113:894–9. doi: 10.1111/bju.12245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shim JS, Choi H, Noh TI, Tae JH, Yoon SG, Kang SH, et al. The clinical significance of a second transurethral resection for T1 high-grade bladder cancer: Results of a prospective study. Korean J Urol. 2015;56:429–34. doi: 10.4111/kju.2015.56.6.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]