Abstract

Introduction:

The aim was to study the accuracy of Xpert® (Cepheid Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) Mycobacterium tuberculosis/rifampicin (MTB/RIF) assay as compared to a composite gold standard (urine culture, imaging, and biopsy) and to asses its utility as the initial test compared to smear microscopy to diagnose urinary tuberculosis.

Methods:

This prospective study included adult patients suspected to have urinary tuberculosis from March 2014 to December 2017. Three urine samples were collected from each patient and were subjected to Xpert MTB/RIF assay, acid-fast bacillus (AFB) smear microscopy, and liquid media (BACTEC Mycobacteria Growth Indicator Tube [MGIT] 960) culture. Imaging and tissue biopsies were performed as clinically indicated. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value were calculated using the bootstrap method for 95% confidence intervals for the Xpert assay.

Results:

Xpert MTB/RIF assay was found to be superior to the currently best available light-emitting diode fluorescent smear microscopy as the initial test for urinary tuberculosis (sensitivity of 69.09% vs. 32.72%). The Xpert MTB/RIF polymerase chain reaction test was found to have a moderate sensitivity (69.09%) and high specificity (100%) as compared to the composite reference standard. The sensitivity of liquid AFB culture MGIT 960 as compared to the reference standard was 90.32%.

Conclusions:

Xpert MTB/RIF assay on an early morning first void urine specimen can replace smear microscopy as the initial diagnostic test for urinary tuberculosis.

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis remains a major public health concern in the developing countries. Paucibacillary specimens and unconventional presentation pose a diagnostic challenge in patients with extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB). In India, where it accounts for 10%–15% of all the TB cases, EPTB is a major health concern.[1] Early case detection and establishment of multidrug-resistant disease, therefore, is critical to successful patient management. Xpert® Mycobacterium tuberculosis/rifampicin (MTB/RIF) assay (Cepheid Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) is a cartridge-based nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT), endorsed by the WHO in 2010 for the rapid diagnosis of tuberculosis after spectacular results in pulmonary specimens.[2] Subsequently, its use was extended to extrapulmonary (EP) disease in 2013.[3] The efficacy and role of the Xpert MTB/RIF test for the diagnosis of urinary tuberculosis remains undefined, as most of the studies, including meta-analysis, have assessed efficacy on pooled EP specimens rather than urine specimens alone.[4] We proposed to study the accuracy of Xpert assay to diagnose urinary tuberculosis compared to a composite gold standard reference comprising of mycobacterial culture, radiological imaging, and tissue biopsy. The secondary outcome was to compare the accuracy of Xpert MTB/RIF assay with the currently used initial test for urinary tuberculosis, light-emitting diode (LED) fluorescence microscopy.

METHODS

This was a single center, prospective study carried out at a tertiary care teaching hospital from March 2014 to June 2017. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee (IRB minute no.: 8727 [DIAGNOSE] dt. 6.3.14) and registered with the Clinical Trial Registry of India (CTRI/2017/02/007758).

The study enrolled adult patients (18 years or older), with clinical or radiological features suggestive of urinary tuberculosis such as severe storage lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), hematuria, sterile pyuria, patients with genital stigmata of tuberculosis, or suspicion of urinary tuberculosis in patients with newly diagnosed tuberculosis at other sites. Patients who had completed antitubercular treatment, patients diagnosed with nontubercular mycobacterial infection or those with a history of previous intravesical Bacillus Calmette–Guerin therapy were excluded from the study.

Patients with a strong clinical suspicion of urinary tuberculosis were asked to provide urine samples for examination. Three urine samples were collected from each patient, with at least two early morning first void samples. The first, early morning sample was treated with N-acetylcysteine-sodium hydroxide 1%, homogenized for 1 min in a centrifuge and was split into aliquots, with some aliquots being sent for Xpert MTB/RIF assay, and the remainder being subjected to concentrated quantitative LED fluorescence acid-fast bacillus (AFB) microscopy and quantitative culture on BACTEC Mycobacteria Growth Indicator Tube (MGIT) 960 liquid culture. MPT64 antigen assay was performed on positive tubes for rapid confirmation of M. tuberculosis complex growth. The second first-void urine and third spot sample were subjected to LED fluorescence microscopy only. All smears were stained by the auramine stain and examined under fluorescent microscope using standard WHO protocols.[5] To confer maximum advantage to the reference initial test, for this study, urine was considered to be smear positive even if any of the urine samples showed a scanty smear score. Radiological imaging such as intravenous urography, retrograde pyelogram (RGP), and tissue biopsies were performed as clinically indicated. Urine mycobacterial culture (MGIT 960 and LJ solid media for speciation), imaging, and biopsy were used as a composite reference gold standard for the diagnosis of M. tuberculosis. Any one of the three being positive was considered as a positive for urinary tuberculosis. Mere clinical suspicion or initiation of empiric antitubercular therapy was not considered diagnostic of tuberculosis in absence of definitive radiological features or mycobacterial evidence. Culture was objectively reported, and the biopsy was considered positive if necrotizing granulomatous inflammation was seen. Isolated ureteric strictures and subjective fuzziness of calyces were not considered diagnostic in the absence of microbiological evidence. However, more extensive urinary tract destruction such as definite calyceal distortion, infundibular strictures, absent calyces, contracted pelvis, extensive ureteric strictures, and small bladders were considered diagnostic even in the absence of microbiological evidence.

The GeneXpert diagnostic system consists of two parts which integrates sample processing and real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in a single step, minimizing exposure, and cross contamination. The technical aspects of the GeneXpert system has been well described by several authors.[6]

Based on Lawn and Zumla,[7] the sensitivity of GeneXpert PCR in urine was reported as 87%; assuming a precision of 10%, with a 95% confidence intervals (CIs), this would provide us with the sample size of 54 TB cases. The measures used to quantify diagnostic significance include sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) and likelihood ratios. Bootstrap methods were used to estimate the 95% CIs. Bootstrap method of the 2 × 2 table was resampled 1000 times. McNemar's test was used to compare sensitivities.

RESULTS

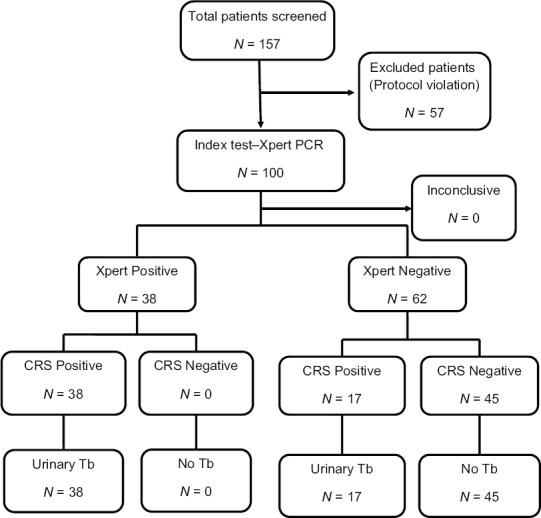

Of the 157 patients with suspected urinary tuberculosis that were screened, 57 patients were excluded either because they did not fulfil the inclusion/exclusion criteria or did not complete the mandatory tests as per protocol. A total of 100 patients were included for analysis [Figure 1 Modified STARD flow chart]. Of these, 55 fulfilled the study's diagnostic criteria (composite reference) and were labelled as positive for urinary tuberculosis while 45 patients had a negative evaluation and were considered as negative for urinary tuberculosis. Figure 1 shows modified STARD flow chart for this study.

Figure 1.

Modified STARD flowchart. CRS – Composite reference standard

The most common presentation in patients with urinary tuberculosis was storage LUTS (68%), followed by hematuria (48%), fever, and weight loss; 15% had genital stigmata of tuberculosis. All patients had an abnormal urinalysis characterized by microscopic hematuria and pyuria, 68% had elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 39% had positive findings on chest radiograph, and about 25% had an elevated serum creatinine. One patient had HIV coinfection. The mean time to result was 1 h and 45 min for Xpert assay while it was 30.5 days (range 7–42 days and a median of 10.5 days) for MGIT 960 AFB culture. In 30 of the positive 55 patients, tissue biopsy was available either in the form of a nephrectomy specimen or from the bladder. Of these, 18 (60%) were positive for tuberculosis. Fifty-four of the 55 positive patients had features suggestive of tuberculosis on imaging (intravenous urogram, RGP, or contrast computed tomography abdomen). One patient who did not have overt imaging features was diagnosed on the basis of biopsy and also had Xpert assay positive.

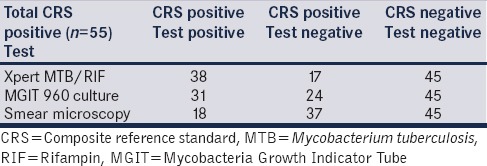

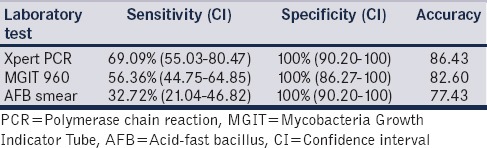

Table 1 shows the results of microbiological evaluation. When compared to the composite reference standard, a single Xpert assay had a sensitivity of 69.09% (95% CI 55.03–80.47%) and a specificity of 100% (95% CI 90.2–100%). The PPV was 100% (CI 95% 88.56–100%), and NPV was 72.58% (95% CI 59.55–82.78%). In contrast, the sensitivity of a single smear examination was only 22.22%. Three serial AFB smear examinations improved the sensitivity to 32.72% (21.04–46.82). When MGIT 960 liquid AFB culture was compared to the composite standard using the other variables, the sensitivity was 56.36% (95% CI 44.75–64.85%). McNemar's test showed that Xpert MTB/RIF assay was significantly superior to three auramine-O-fluorescent smear microscopy examinations (69.09% vs. 32.72%, P = −0.0003) while its better performance over the MGIT 960 AFB culture was not statistically significant (69.09 vs. 56.36, P = 0.09).

Table 1.

Results of microbiological examination

If the mycobacterial AFB culture was solely used as the reference standard, the Xpert MTB/RIF assay showed a sensitivity of 90.32% (95% CI 73.09–97.46%), with a high specificity (85.56% CI 74.49–92.46%), unlike the previous NAATs and other measures such as radiological imaging.

Xpert MTB/RIF assay identified 58.3% of smear-negative and 34.78% of culture-negative cases. However, it missed 2 of the 31 (6.4%) culture-positive patients. None of the patients had rifampicin resistance either on Xpert MTB/RIF assay or on AFB cultures. Table 2 shows the comparative efficacy of Xpert MTB/RIF, BACTEC MGIT 960, and AFB smear fluorescence microscopy. The accuracy of Xpert assay in diagnosing urinary tuberculosis was 86.43% compared to 82.6% for MGIT 960 culture and 77.43% for AFB smear microscopy.

Table 2.

Comparative efficacy of Gene Xpert Mycobacterium tuberculosis/rifampin polymerase chain reaction, mycobacteria growth indicator tube 960, and acid-fast bacillus smear microscopy

DISCUSSION

Tuberculosis of the urinary system, unlike its other forms, lacks systemic symptoms and has long latency periods leading to a delay in evaluation. Rapid diagnosis is critical as timely initiation of antitubercular therapy may limit the structural and functional damage to the urinary tract. Several of the rapid tests for tuberculosis have had limited clinical utility, especially in endemic countries and in paucibacillary settings. For over a century, AFB smear microscopy was the only available rapid and reliable test.

The heterogeneity of EPTB means that there is variation in diagnostic accuracy estimates of the same test on different specimens. Previous studies have included urine samples in the pooled analysis of various EP specimens or have reported a combined tissue and urine analysis in patients with genitourinary tuberculosis. Also, these are largely retrospective reports and only a few have compared Xpert MTB/RIF to the modern smear microscopy, the test it is intended to replace. Till date, no study has exclusively focused on urinary tuberculosis or defined the role of Xpert MTB/RIF assay from a clinical perspective. Hence, we decided to evaluate the efficacy and role of the Xpert MTB/RIF assay in the diagnosis of urinary tuberculosis.

Against the microbiological gold standard of AFB culture as the reference standard, the sensitivity of Xpert MTB/RIF assay was 90.32% in the study population (CI 95% 73.09–97.46%). Hillemann et al.[8] evaluated 521 nonrespiratory specimens (91 urine, 30 gastric aspirate, 245 tissue, 113 pleural fluid, 19 cerebrospinal fluid, and 23 stool specimens) submitted to the German National Reference Laboratory for the detection of Mycobacteria. These specimen were subjected to Xpert MTB/RIF assay, liquid (MGIT 960), and solid (LJ and Stonebrink) culture methods. The sensitivity and specificity for urine specimens of the Xpert assay as compared to the culture methods were reported as 100% and 98.6%. However, of the 91 urine samples included in their study, there were only six cases of urinary tuberculosis. Lawn and Zumla[7] also assessed 238 EPTB samples and reported a sensitivity of 87.5% (CI 71–100%) for Xpert MTB/RIF assay for urine specimens, however, of these 238 specimens only 6% were urine specimens.

Tortoli et al.[9] studied 1476 EP samples; however, like the others, there were only 130 urine specimens and only 16 of them were from positive cases of urinary tuberculosis and also included samples from children. They reported an overall sensitivity and specificity of the Xpert assay as 81.3% and 99.8%, respectively, as compared to the culture and a sensitivity and specificity of 92.3% and 99%, respectively, as compared to a composite gold standard. Their diagnostic gold standard included both positive culture and clinical findings, but diagnostic criteria were less rigorously explained with leeway for clinical interpretation. A meta-analysis by Penz et al.[10] included eight studies and analyzed about 725 specimens. However, they only reported a pooled sensitivity of urine and tissue samples in genitourinary tuberculosis with a sensitivity of 70% (95% CI 53–95%) and a pooled specificity of 94% (95% CI 71–99%). Estimates of accuracy from pooling disparate clinical entities such as urinary and genital tuberculosis (our study had only a 15% overlap) does not clarify pre and posttest likelihood of disease for practicing clinicians. Limited sample size, pooled analysis of specimens, the limitations of an imperfect reference standard, and limited positive samples i mar the interpretation, accuracy and generalisability of the results of efficacy of Xpert assay as depicted in these studies.

A systematic review has suggested that implementation of fluorescence microscopy in tuberculosis endemic countries might improve tuberculosis case finding due to an increase in direct smear sensitivity and decrease in turnaround time for reporting of the smear results. Strong evidence suggests that fluorescence microscopy is more sensitive than conventional light microscopy (with no significant loss in specificity).[11] In paucibacillary disease, however, despite technical improvements, smear microscopy has abysmal sensitivity and predictive value in addition to tedious processing and interpretation. We found Xpert MTB/RIF assay superior to the best current available LED fluorescent smear microscopy on serial specimens as an initial test for urinary tuberculosis (sensitivity of 69.09% vs. 32.76%).

Another study from India compared LED fluorescent microscopy with the GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay for the diagnosis of pulmonary and EP TB and reported LED smear-positive rates of 9.1% (95% CI 6.1–13.3) versus Xpert positive rates of 29.2% (95% CI 24–35.2), but this study did not include urine in the EP specimens.[12] The WHO results show that the accuracy of LED microscopy is equivalent to that of international reference standards; it is more sensitive than conventional Ziehl–Neelsen microscopy, and it has qualitative, operational, and cost advantages over both conventional fluorescence and Ziehl–Neelsen microscopy. Based on these findings, in 2010, the WHO recommends that conventional fluorescence microscopy be replaced by LED microscopy and that LED microscopy be phased in as an alternative for conventional Ziehl–Neelsen light microscopy.[13]

Xpert MTB/RIF assay succeeds in combining diagnostic accuracy with practical utility. The console limits specimen handling and decreases cross contamination, does not require specialized laboratories or labor, has a rapid turnover time while processing multiple specimens simultaneously, and retains impressive specificity. Boehme et al.[14] have studied its utility in peripheral clinics and have supported its implementation in public health programs. This study attempted to replicate, as closely as possible, the utility of the Xpert assay test in the early detection of urinary tuberculosis in a clinical setting. Xpert assay performed twice as well as compared to smear microscopy, the standard initial test for tuberculosis. It also performed well in smear-negative cases, identifying 58% of smear-negative, and 34% of culture-negative patients, who had additional features of tuberculosis by the reference standard. Two smear- and culture-positive patients were missed by the Xpert assay. Nonstandardized preprocedure processing in EPTB specimens and calibration with different thresholds can contribute to such results.[11]

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting the efficacy of Xpert MTB/RIF assay in diagnosing urinary tuberculosis. The strengths of our study are that it is a prospective study and it compared the Xpert MTB/RIF assay with the LED fluorescent microscopy and also with a composite gold standard. The limitation of our study was a higher precision point than that is ideal. The perfect reference standard in paucibacillary tuberculosis is elusive, and our study results reflect this drawback. Schumacher et al.[15] using childhood tuberculosis as a template have suggested Bayesian latency models to improve accuracy estimates in clinical scenarios where reference standards are imperfect. We are aware that a composite reference standard is likely to underestimate sensitivity and therefore results in false negatives. The practice implication is that when Xpert PCR is negative, decision to start antitubercular therapy should depend on all available clinical information. In patients in endemic countries with clear signs of disease, immunocompromised individuals or others who have life- or organ-threatening disease, Xpert PCR may not provide the best post test probability and therapy may be started despite a negative result. The high PPV means that in cases where the result is positive, anti-tubercular therapy can be confidently started without necessarily waiting for further bacteriological confirmation, especially in resource-poor settings were other diagnostic methods may not be available.

CONCLUSIONS

As the initial screening test for urinary tuberculosis, a single Xpert assay is superior to the best available, LED fluorescent smear microscopy on serial (three) specimens. Good performance in smear- and culture-negative samples means it performs well as an add-on test also. Precluding availability and cost, a single Xpert assay on an early morning first void urine specimen can replace smear microscopy as the initial diagnostic test for urinary tuberculosis. The moderate sensitivity means that when the Xpert MTB/RIF assay test is negative, the interpretation should be in the context of all the available clinical information. Our results support Xpert MTB/RIF assay test as the best initial test in the diagnosis of urinary tuberculosis which can help the clinician in prompt and rational use of antitubercular therapy.

Footnotes

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vadwai V, Boehme C, Nabeta P, Shetty A, Alland D, Rodrigues C, et al. Xpert MTB/RIF: A new pillar in diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis? J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:2540–5. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02319-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boehme CC, Nabeta P, Hillemann D, Nicol MP, Shenai S, Krapp F, et al. Rapid molecular detection of tuberculosis and rifampin resistance. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1005–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. World Health Organization | Global Tuberculosis Report. 2014. [Last accessed on 2014 Dec 06]. Available from: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/

- 4.Maynard-Smith L, Larke N, Peters JA, Lawn SD. Diagnostic accuracy of the Xpert MTB/RIF assay for extrapulmonary and pulmonary tuberculosis when testing non-respiratory samples: A systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:709. doi: 10.1186/s12879-014-0709-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Global Laboratory Initiative. TB Sputum Microscopy Handbook. 2013. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 06]. p. 31. Available from: http://www.stoptb.org/wg/gli/assets/documents/TB%20MICROSCOPY%20HANDBOOK_FINAL .

- 6.Helb D, Jones M, Story E, Boehme C, Wallace E, Ho K, et al. Rapid detection of mycobacterium tuberculosis and rifampin resistance by use of on-demand, near-patient technology. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:229–37. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01463-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawn SD, Zumla AI. Diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis using the Xpert(®) MTB/RIF assay. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2012;10:631–5. doi: 10.1586/eri.12.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hillemann D, Rüsch-Gerdes S, Boehme C, Richter E. Rapid molecular detection of extrapulmonary tuberculosis by the automated gene Xpert MTB/RIF system. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:1202–5. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02268-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tortoli E, Russo C, Piersimoni C, Mazzola E, Dal Monte P, Pascarella M, et al. Clinical validation of Xpert MTB/RIF for the diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:442–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00176311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Penz E, Boffa J, Roberts DJ, Fisher D, Cooper R, Ronksley PE, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the Xpert® MTB/RIF assay for extra-pulmonary tuberculosis: A meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19:278. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steingart KR, Henry M, Ng V, Hopewell PC, Ramsay A, Cunningham J, et al. Fluorescence versus conventional sputum smear microscopy for tuberculosis: A systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:570–81. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70578-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alvarez-Uria G, Azcona JM, Midde M, Naik PK, Reddy S, Reddy R, et al. Rapid diagnosis of pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients. Comparison of LED fluorescent microscopy and the geneXpert MTB/RIF assay in a district hospital in India. Tuberc Res Treat 2012. 2012:932862. doi: 10.1155/2012/932862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Flouresecent Light Emitting Diode Microscopy for Diagnosis of Tuberculosis: Policy Statement. Geneva: World health Organization; 2010. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 06]. Available from: http://www.who.int/tb/laboratory/who_policy_led_microscopy_july10.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boehme CC, Nicol MP, Nabeta P, Michael JS, Gotuzzo E, Tahirli R, et al. Feasibility, diagnostic accuracy, and effectiveness of decentralised use of the Xpert MTB/RIF test for diagnosis of tuberculosis and multidrug resistance: A multicentre implementation study. Lancet. 2011;377:1495–505. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60438-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schumacher SG, van Smeden M, Dendukuri N, Joseph L, Nicol MP, Pai M, et al. Diagnostic test accuracy in childhood pulmonary tuberculosis: A Bayesian latent class analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;184:690–700. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]