Abstract

Although cartilaginous fishes have played crucial roles in various fields, including evolutionary biology, marine ecology, bioresources, and aquarium exhibitions, molecular information for these species is poorly available. The present study reports a transcriptome assembly from an embryo of the zebra bullhead shark (Heterodontus zebra), produced by paired-end RNA sequencing. Transcriptome data is generated with a de novo transcriptome assembler, Trinity. Amino acid sequences are predicted from the assemblies, using TransDecoder. Because cartilaginous fishes serve as the outgroup of bony vertebrates, the data would contribute to comparative analyses of a various biological fields. In addition, this study would be useful for conservation biology, such as transcriptome-based population genetics.

Subject terms: Transcriptomics, Molecular evolution

Background & Summary

Long generation cycle, large body size, and slow growth rate are the characteristics of cartilaginous fishes1,2, and also the main reasons why they are difficult to keep in laboratories. These factors have distracted researchers from the modern molecular studies of cartilaginous fishes. Instead, animals with a small body and short generation time, such as fruit flies, nematodes, zebrafishes, and mice have been intensely studied as "model organisms", which has accelerated our understandings of biology3. However, such convenience-oriented choices of species may lead to accumulation of biased knowledge4–6. Indeed, recent studies showed that non-coding sequences are more comparable between the genomes of humans and cartilaginous fishes than between those of humans and zebrafishes7–9. This comparability is likely attributed to the slower molecular clock of cartilaginous fishes than that of teleosts1,10,11. Therefore, the study of cartilaginous fishes helps us recognize the secondary modifications of model vertebrate species. Because molecular information of cartilaginous fishes is currently available for a limited number of species, further augmentation of molecular data in this clade would be useful for comparative studies.

In addition, cartilaginous fishes play important roles for marine ecology, bioresources, and aquarium exhibitions2. Owing to the slow growth rate, long generation time, and sparse reproductive cycles, it has been realized that cartilaginous fishes are vulnerable to human impacts2. Therefore, an efficient and precise conservation policy is required for a sustainable interaction between humans and cartilaginous fishes. Recently, transcriptome data is increasingly utilized for population genetics, which can estimate divergence and effective population size of species12,13. In addition, a molecular phylogenetics-based score, “evolutionary distinctness” (ED), which evaluates species uniqueness, is also used for conservation prioritization14,15. In these respects, molecular information would contribute to making a more effective conservation policy for cartilaginous fishes.

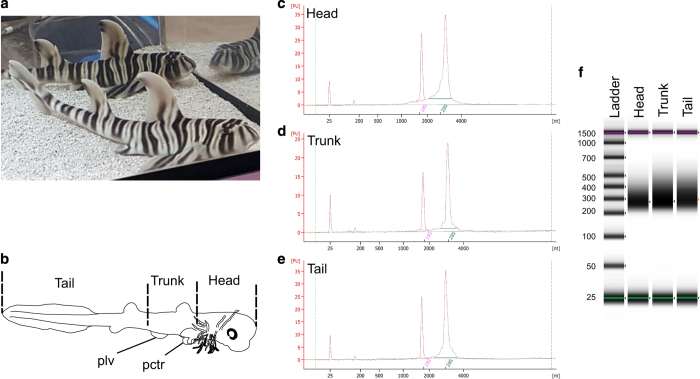

In this study, we report transcriptome data of the zebra bullhead shark (Heterodontus zebra; Fig. 1a). The zebra bullhead shark is an elasmobranch species that is common in the Western Pacific ranging from Japan to Australia16. The order that this species belongs to is Heterodontiformes, which includes only one living genus with nine species and relatively high ED score17. While the zebra bullhead shark is currently classified as Least Concern by the IUCN’s Red List, five out of the nine species are Data Deficient because their biological information is virtually missing18. Thus, the zebra bullhead shark may serve as a reference to characterize the species of this genus in the future. An embryo of the zebra bullhead shark was collected from Ibaraki Prefectural Oarai Aquarium. About 900,000 transcripts were assembled from the paired-end libraries of its RNAs produced by Illumina HiSeq. Of them, about 79,000 protein-coding sequences were predicted from the obtained transcript contigs.

Figure 1. The zebra bullhead shark and sample preparation.

(a) Juvnile zebra bullhead sharks. (b) A schematic diagram of a zebra bullhead shark embryo. Dashed lines, dissected positions; pctr, pectoral fins; plv, pelvic fins. (c-e) RNA length distribution analysis of head (c), trunk (d), and tail (e) samples on the 2100 Bioanalyzer, respectively. (f) DNA length distribution analysis of prepared libraries on the 2100 Bioanalyzer.

Methods

Generation of the datasets

Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), RIKEN Kobe Branch. Zebra bullhead shark eggs were incubated at 24.5 °C, 8.0–8.2 pH in a tank of Ibaraki Prefectural Oarai Aquarium. An egg 33 days after deposition was collected, and an about 33 mm-long embryo was dissected into the head, trunk, and tail parts (Fig. 1b), and flash-frozen with liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. RNAs were extracted with the RNeasy Mini plus kit (QIAGEN, Cat. No. 74134). Genomic DNA was removed with gDNA Eliminator columns in this kit. For a quality control, the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer system and Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Kit (Agilent, Cat. No. 5067-1511) were used to measure their RNA integrity number, which yielded the score of 10.0 for all samples (Fig. 1c-e). For RNA-seq, using 0.5 μg of each of the extracted total RNAs, strand-specific RNA-seq libraries were prepared with the TruSeq Stranded mRNA LT Sample Prep Kit (Illumina, Cat. No. RS-122-2101 and/or RS-122-2102 ). For DNA purification, we applied 1.8x (after end repair) and 1.0x (after PCR) volumes of Agencourt AMPure XP (Beckman Coulter, Cat. No. A63880). The optimal number of PCR cycles was determined by a preliminary PCR using KAPA Library Amplification Kit (KAPA, Cat. No. KK2702) and estimated to be three cycles. The quality of the libraries was checked by Agilent 4200 TapeStation (Agilent; Fig. 1f). The libraries were sequenced after on-board cluster generation for 127 cycles using 3x HiSeq Rapid SBS Kit v2-HS (50 cycle; Illumina, Cat. No. FC-402-4022) and HiSeq PE Rapid Cluster Kit v2-HS (Illumina, Cat. No. PE-402-4002) on a HiSeq 1500 (Illumina) operated by HiSeq Control Software v2.0.12.0. The output was processed with Illumina RTA 1.18.64 for basecalling and with bcl2fastq 1.8.4 for de-multiplexing. Quality control of the obtained fastq files for individual libraries was performed with FASTQC v0.11.5. The produced data set is indicated in Table 1.

Table 1. List of raw reads.

| Organism | Sample | Protocol 1 | Protocol 2 | read-pairs | BioSample | Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hetrodontus zebra | Embryonic head | RNA extraction | RNA-Sequencing (paired-end) | 105,062,934 | SAMN08388717 | SRR6649877 |

| Hetrodontus zebra | Embryonic trunk | RNA extraction | RNA-Sequencing (paired-end) | 112,030,698 | SAMN08388717 | SRR6649876 |

| Hetrodontus zebra | Embryonic tail | RNA extraction | RNA-Sequencing (paired-end) | 103,255,692 | SAMN08388717 | SRR6649875 |

Data processing

Using a sequence trimming pipeline, trim-galore (https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore, version 0.4.4; parameters: --paired --phred33 -e 0.1 -q 30), adaptors and low-quality sequences were removed from the data set. To avoid contamination, we removed reads that were mapped to the genomes of other species sequenced in the same HiSeq lane (humans, mice, and the brown-banded bamboo shark), using bowtie219 (version 2.2.6) to map reads and paifq (https://github.com/sestaton/Pairfq, version 0.17.0) to make pairs from unmapped reads. The overall mapping rates to other genomes were 0.11–0.12% for the human genome, 8.83–9.39% for bamboo shark genome, and 0.09–0.12% for mouse genome. This process was included because we found some contaminated transcripts in a preliminary assessment. Using a de novo transcriptome assembler, Trinity20 (version 2.4.0), the decontaminated reads were assembled to two initial transcriptome sets with two parameter sets: --SS_lib_type RF --trimmomatic (Assembly 1), or --SS_lib_type RF --trimmomatic --jaccard_clip (Assembly 2). Protein coding sequences (Assembly1_prot and Assembly2_prot) were predicted with a coding region finding program, TransDecoder21 (version 3.0.1) and using results from BlastP22 (2.2.31+) search against the Swissprot database23 and hmmscan (http://hmmer.org/, version 3.1b2) with the Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org/) according to the guide in TransDecoder. To reduce the complexity of the assemblies, overlapping amino acid sequences were removed from the predicted data with a clustering programme, cd-hit24 (parameters: -c 0.90 -n 5; Assembly1_prot_single and Assembly2_prot_single). The details of the assemblies were listed in Table 2. The commands were listed in “script.txt” in Data Citation 1.

Table 2. Transcriptome assembly metrics.

| Assembly name | Source | Data processing | Coding contigs |

BUSCOv2+vertebrates (2586 core genes) |

BUSCOv2+CVG (233 core genes) |

Horn shark genes (124) | Data Accession | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete (+partial) | Percentage | Orthologs per core genes | Complete (+partial) | Percentage | Orthologs per core genes | ||||||

| Assembly1_prot | Assembly1 | transdecoder | 189096 | 2496 (2553) | 96.52 (98.72) | 3.1 | 227 (233) | 97.42 (100) | 3.05 | 50a | figshare (Data Citation 1) |

| Assembly1_prot_single | Assembly1 | transdecoder+cd-hit | 79601 | 2494 (2552) | 96.44 (98.69) | 1.2 | 227 (233) | 97.42 (100) | 1.15 | 50a | figshare (Data Citation 1) |

| Assembly1_prot | Assembly2 | jaccard+transdecoder | 186370 | 2489 (2551) | 96.25 (98.65) | 3.05 | 227 (233) | 97.42 (100) | 3 | 55 | figshare (Data Citation 1) |

| Assembly1_prot_single | Assembly2 | jaccard+transdecoder+cd-hit | 79383 | 2487 (2551) | 96.17 (98.65) | 1.2 | 227 (233) | 97.42 (100) | 1.15 | 55 | figshare (Data Citation 1) |

aMissings: AAA59375.1, AAF44636.1, AAA59377.1, AAA59373.1; too short: CAA35661.1.

Data Records

The decontaminated sequence read data, which contains three records, were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (Data Citation 2 and Table 1). The Assembly 1 was deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank (Data Citation 3 and Table 2; through the registration to the GenBank, several possible contaminants were removed from the assembly). Untrimmed reads, unfiltered Assembly 1 and 2, predicted amino acid sequences, and full quality metrics are available on figshare (Data Citation 1 and Tables 2 and 3).

Table 3. Completeness assessment of coding gene sets predicted from the transcriptome assemblies.

| Name | Libraries | Parameters | Contigs | Smallest | Largest | Mean length | n50 | gc | Transrate assembly score | Good contig % | Data Accession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assembly 1 | pooled reads from embryonic head, trunk, and tail | trimmomatic | 947144 | 201 | 42242 | 709 | 1611 | 0.436 | 0.1999 | 88% | GenBank (Data Citation 3) figshare (Data Citation 1) |

| Assembly 2 | pooled reads from embryonic head, trunk, and tail | trimmomatic, jaccard clip | 952464 | 201 | 32662 | 689 | 1482 | 0.436 | 0.2004 | 68% | figshare (Data Citation 1) |

Technical Validation

Firstly, using a transcriptome quality analysis tool, TransRate25 (v1.0.3), we measured assembly scores and contig scores. Because this program evaluates the quality of a transcriptome assembly through mapping reads to it, we performed additional curations to the trimmed reads with trimmomatic26 with the same parameter set that Trinity uses (parameters: ILLUMINACLIP:$TRIMMOMATIC_DIR/adapters/TruSeq3-PE.fa:2:30:10 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:5 LEADING:5 TRAILING:5 MINLEN:25). We also modified parameters of snap-aligner26 and salmon27 in TransRate; “-h” of snap-aligner, and “--noEffectiveLengthCorrection” and “--useFSPD” of salmon were commented. The assembly scores were listed in Table 2. The program also provided “good contigs”, which were determined by the cutoff optimisation procedure described in [25]28–31.

Next, we evaluated the completeness of the translated assemblies, using the BUSCO programme32 through gVolante web server33. The scores were calculated with the BUSCO Vertebrata gene set34 and with the CVG gene set35 (Table 3). Overall, the completeness assessment yielded high scores for all assemblies. However, the assessment with the BUSCO Vertebrata gene set indicated slightly better completeness for Assembly 1. These figures should be interpreted carefully because the gene sets used for the assessment are mostly composed of house-keeping genes. Given the samples were obtained from a particular stage of a developing embryo, the true completeness, i.e. assembled genes/all genes that the species has, should be lower than these figures.

Because the assembly scores and the completeness scores were slightly inconsistent with each other, we also performed additional quality evaluation by examining whether the assemblies cover known genes of the horn shark (Heterodontus francisci), a closely related species to our target. We queried 124 genes (Data Citation 3) of the horn shark deposited in the GenBank against the translated assemblies, showing that Assembly 2 covered more known genes than Assembly 1 (Table 3). These results suggest that these two assemblies cover partially different genes. Therefore, we suggest that users need to search both of the assembles to find genes of interests.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Onimaru, K. et al. A de novo transcriptome assembly of the zebra bullhead shark, Heterodontus zebra. Sci. Data. 5:180197 doi: 10.1038/sdata.2018.197 (2018).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Osamu Nishimura and the staff of the Phyloinformatics unit at RIKEN CLST for technical support, and the staff of the Fish Exhibition Division at Ibaraki Prefectural Oarai Aquarium for helping us collect samples. This work was supported by a research grant from MEXT to the RIKEN Center for Life Science Technologies.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data Citations

- Onimaru K., Tatsumi K., Shibagaki K., Kuraku S. 2018. figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.5856912.v5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Onimaru K., Tatsumi K., Shibagaki K., Kuraku S. 2018. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP131715

- Onimaru K., Tatsumi K., Shibagaki K., Kuraku S. 2018. GenBank. GGGL00000000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

References

- Martin A. P., Naylor G. J. P. & Palumbi S. R. Rates of mitochondrial DNA evolution in sharks are slow compared with mammals. Nature 357, 153–155 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimley A. P.. The biology of sharks and rays. The University of Chicago Press, (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Hedges S. B. The origin and evolution of model organisms. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 838–849 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell J. J. et al. Non-model model organisms. BMC Biol. 15 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein B. & King N. The Future of Cell Biology: Emerging Model Organisms. Trends Cell Biol. 26, 818–824 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuraku S., Feiner N., Keeley S. D. & Hara Y. Incorporating tree-thinking and evolutionary time scale into developmental biology. Dev. Growth Differ. 58, 131–142 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh B. et al. Ancient noncoding elements conserved in the human genome. Science 314, 1892 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A. P., Kerk S. Y., Tan Y. Y., Brenner S. & Venkatesh B. Ancient vertebrate conserved noncoding elements have been evolving rapidly in teleost fishes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 1205–1215 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onimaru K. et al. A shift in anterior–posterior positional information underlies the fin-to-limb evolution. Elife 4, e07048 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh B. et al. Elephant shark genome provides unique insights into gnathostome evolution. Nature 505, 174–179 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renz A. J., Meyer A. & Kuraku S. Revealing less derived nature of cartilaginous fish genomes with their evolutionary time scale inferred with nuclear genes. PLoS One 8, e66400 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dlugosch K. M., Lai Z., Bonin A., Hierro J. & Rieseberg L. H. Allele Identification for Transcriptome-Based Population Genomics in the Invasive Plant Centaurea solstitialis. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 3, 359 LP–359367 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayral P. et al. Reference-free population genomics from next-generation transcriptome data and the vertebrate invertebrate gap. PLoS Genet. 9 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac N. J. B., Turvey S. T., Collen B., Waterman C. & Baillie J. E. M. Mammals on the EDGE: Conservation priorities based on threat and phylogeny. PLoS One 2 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonini J. F. R., Beard K. H., Ferreira R. B., Jetz W. & Pyron R. A. Fully-sampled phylogenies of squamates reveal evolutionary patterns in threat status. Biol. Conserv. 204, 23–31 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Ebert D. A., Fowler S., Compagno L. & Dando M.. Sharks of the world. Wild Nature Press, (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Stein R. W. et al. Global priorities for conserving the evolutionary history of sharks, rays and chimaeras. Nat. Ecol. Evol 2, 288–298 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read T. D. et al. Draft sequencing and assembly of the genome of the world’s largest fish, the whale shark: Rhincodon typus Smith 1828. BMC Genomics 18, 532 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B. & Salzberg S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr M. G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–652 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas B. J. et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 8, 1494–1512 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho C. et al. BLAST + : architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 1–9 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A. et al. UniProt: The universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D158–D169 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. & Godzik A. Cd-hit: A fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 22, 1658–1659 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Unna R., Boursnell C., Patro R., Hibberd J. M. & Kelly S. TransRate: Reference-free quality assessment of de novo transcriptome assemblies. Genome Res. 26, 1134–1144 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger A. M., Lohse M. & Usadel B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaharia M. et al. Faster and More Accurate Sequence Alignment with SNAP. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1111.5572 (2011).

- Patro R., Duggal G., Love M. I., Irizarry R. A. & Kingsford C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 14, 417–419 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simão F. A., Waterhouse R. M., Ioannidis P., Kriventseva E. V. & Zdobnov E. M. BUSCO: Assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura O., Hara Y. & Kuraku S. gVolante for standardizing completeness assessment of genome and transcriptome assemblies. Bioinformatics 33, 3635–3637 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra G., Bradnam K., Ning Z., Keane T. & Korf I. Assessing the gene space in draft genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 289–297 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara Y. et al. Optimizing and benchmarking de novo transcriptome sequencing: from library preparation to assembly evaluation. BMC Genomics 16, 977 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Onimaru K., Tatsumi K., Shibagaki K., Kuraku S. 2018. figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.5856912.v5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Onimaru K., Tatsumi K., Shibagaki K., Kuraku S. 2018. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP131715

- Onimaru K., Tatsumi K., Shibagaki K., Kuraku S. 2018. GenBank. GGGL00000000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]