Abstract

In a competing risks analysis, interest lies in the cause-specific cumulative incidence function (CIF) which can be calculated by either (1) transforming on the cause-specific hazard (CSH) or (2) through its direct relationship with the subdistribution hazard (SDH). We expand on current competing risks methodology from within the flexible parametric survival modelling framework (FPM) and focus on approach (2). This models all cause-specific CIFs simultaneously and is more useful when we look to questions on prognosis. We also extend cure models using a similar approach described by Andersson et. al. for flexible parametric relative survival models. Using SEER public use colorectal data, we compare and contrast our approach with standard methods such as the Fine & Gray model, and show that many useful out-of-sample predictions can be made after modelling the cause-specific CIFs using a FPM approach. Alternative link functions may also be incorporated such as the logit link. Models can also be easily extended for time-dependent effects.

Introduction

To understand more about patient prognosis and disease impact, the probability of death due to a particular cause in the presence of other causes is needed and involves the consideration of competing causes of death. This probability is known as the cause-specific cumulative incidence function (CIF). From a statistical modelling perspective, this is usually obtained by either (1) estimating all the cause-specific hazard (CSH) functions, or (2) transforming using a direct relationship with the subdistribution hazard (SDH) function for the cause of interest. The choice of model on which to make our statistical inference depends on the research question to be answered. Wolbers et. al., 1 along with others, highlight that, if interest lies in prognosis, direct inference on the cause-specific CIF is most useful. On the other hand, for more aetiological-type research questions, regression models on the CSH are more important.2,3,4 In this paper we focus on developing methodology when interest is in prognosis where models have the advantage of maintaining the one-to-one correspondence between the covariates and the cause-specific CIF. On the other hand, models for the CSH estimate covariate effects on mortality rates amongst those at risk. Hence, parameter effects on the two models are not the same and have different interpretations. Although most researchers tend to focus on reporting results on either the CSH or SDH, we support the view that results on both CSH and SDH models should be reported together for a complete understanding on the impact of covariate on risk.5,6 At present, the most commonly implemented method for modelling covariate effects on the cause-specific CIF is the Fine & Gray model for the SDH.7,8 However, this approach models a single event and we must fit separate models for all events of interest if we want to understand the overall impact of a covariate. Jeong and Fine9 investigated a direct parametric inference approach and define a likelihood which allows us to model all the cause-specific CIFs simultaneously. We extend this approach to flexible parametric models (FPM) which offer some advantages. For instance, by adopting the direct approach in modelling the cause-specific CIF under FPMs, it is less computationally intensive compared to the Fine & Gray approach since it does not require the calculation of time-dependent weights for the censoring distribution. This gain in computational efficiency is especially useful when analysing larger datasets. Also, under the approach proposed in this paper for directly modelling the cause-specific CIF, a more flexible shape for the underlying cause-specific CIF whilst simultaneously modelling for more complex time-dependent effects is possible in contrast to the Jeong & Fine model. Finally, in comparison to the approach described by Jeong and Fine9, FPMs have the ability to model more complex shaped subdistribution hazard functions. Other methods for directly modelling the cause-specific CIF also implement estimation under alternative link functions. For example, Gerds et. al. 10 proposes the proportional odds model for the cause-specific CIF and makes the argument that this has the attractive property of simpler parameters with a more useful odds-ratio interpretation in comparison to the SDH model. However, there still remain some interpretation issues (see Section 2.4.1). Incorporating such alternative link functions on the cause-specific CIF is easy to implement using the approach outlined in this paper. In addition to the above, other useful comparative predictions to aid interpretation in FPMs is trivial since the baseline CIF is predicted as part of the likelihood in the model and is easily extractable as part of the linear predictor for further calculations involving the cause-specific CIFs. Standard errors and confidence intervals are calculated using the delta method.

Over a reasonably long enough follow up time, the cause-specific CIF for most cancers reach a plateau, referred to as “statistical” cure. At this point, patients no longer die from the cancer of interest and instead die from the other competing events, in which case, modelling the cure proportion amongst cancer patients may be of interest.11 We further develop cure models previously designed for the cause-specific or relative survival framework and extend to the approach outlined in this paper.12,13 Fitting these models allow us to obtain a direct estimate of the cure proportion.

In this paper, we introduce a FPM approach for direct likelihood inference on the cause-specific CIF. The model is then extended to estimate the cure proportion and estimate the probability of patients bound to die from cancer amongst those that are still alive.14 The remaining content of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews competing risks theory and introduces the SDH. The proportional flexible parametric log-cumulative SDH and proportional odds models are formulated followed by a demonstration of a simple extension for inclusion of time-dependent effects to model non-proportionality. The model is further extended to estimate the cure proportion. In Section 3, advantages of the model are demonstrated through an illustrative example using SEER colorectal data. Finally, Section 4 discusses the method, some limitations and potential areas of interest for future methodological development.

Methodology

Let T be the time to event any of K competing causes k = 1, ⋯ , K and D denote the type of event, where D = 1, ⋯ , K. Here, we consider the events to be death from different causes and so the cause-specific CIF, Fk(t), is the probability of dying from a particular cause, D = k, by time t whilst also being at risk of dying from other causes 15,

| (1) |

The all-cause CIF, F(t), which is the probability of dying from any of the K causes by time t, is the sum of all K cause-specific CIFs and can also be expressed as the complement of the overall survival function, S(t),

| (2) |

Cause-specific and subdistribution hazard functions

The cause-specific CIF, Fk(t), can be expressed as a function of the SDH for cause k or expressed as a function of the CSH functions for all k causes. The CSH function, gives the instantaneous mortality rate from a particular cause k given that the patient is still alive at time t in the presence of all the other causes of death.

| (3) |

The cause-specific CIF can be written as a function of the CSHs for all K causes such that,

| (4) |

Note here that the leading term within the integral gives the overall survival function, S(t).

Gray16 introduces the SDH for cause k, which gives a direct relationship with the cause-specific CIF. This has the following mathematical formulation,

| (5) |

and is interpreted as the instantaneous rate of failure at time t from cause k amongst those who are still alive, or have died from any of the other K – 1 competing causes excluding cause k.17 Consequently, the cause-specific CIF can be formulated directly in terms of the SDH function for cause k using standard survival relationships along with the cumulative SDH for cause

| (6) |

An important distinction between the CSH and SDH for cause k is found within the risk-set. The risk-set in the CSHs is described in the conventional epidemiological sense, i.e. those who have died from any of the k causes of death, are no longer considered to be at risk. In contrast, the risk-set for the SDH for cause k considers patients who have died from any of the K – 1 competing causes, excluding cause k, to still be at risk from dying of the cause of interest, k. A more detailed description and comparison of the risk-sets for the CSH and SDH for cause k can be found in Lau et. al. 18 Evidently, the risk-set associated with the SDH is unrealistic since of course those who have died from other causes excluding the cause of interest, i.e. cancer, cannot still be at risk. This has led to some discussion on the usefulness of the SDH function.19,6,20 However, a benefit of this construct is that it maintains a direct link to the cause-specific CIF and has been used in regression models so that we can identify a relationship between covariates and risk for cause k.

A useful relationship between the SDH and CSH was highlighted by Beyersmann and Schumacher21 in a letter regarding an article by Latouche et. al. 22,

| (7) |

Thus using the SDH functions for all K causes, we can also obtain the CSH functions for all K causes.

Regression modelling

A common approach for modelling the CSH function is by assuming proportional hazards (PH) using the Cox model. So with covariates, x, we have that,

| (8) |

where are log cause-specific hazard ratios (HR), and is the baseline CSH function. To re-iterate, in order to estimate one cause-specific CIF, it is necessary to estimate the CSHs for all k causes (see Equation 4).

Alternatively, the most common model for the SDH for cause k is the Fine & Gray model.7 This is derived in a similar way to the cause-specific Cox PH model in that it assumes proportionality of covariate effects on the SDH scale,

| (9) |

where are log-SDH ratios (SHR) for cause k.

A key difference between the two regression models in Equation 8 and Equation 9 is in the interpretation of the parameters exp (HRs) and exp (SHRs). The HRs give us the association on the effect of a covariate on the cause-specific mortality rate and SHRs give the association on the effect of a covariate on risk (refer to Wolbers et. al. 1 for further details on interpretation). In this paper, we focus on implementing and extending the SDH regression model in Equation 9 from within the FPM approach.

Likelihood estimation

We first describe parametric inference on K competing causes of death under the CSH approach, which models using the standard survival likelihood function with an observable failure or censoring time, ti, with independent and non-informative right censoring, for each individual i = 1, ⋯ , N,

| (10) |

where the censoring indicator, δik, tell us whether an individual died from any cause k (δik = 1), or not (δik = 0) and S(ti|xk) is the overall survival function.

Alternatively, Jeong and Fine9 showed that we can simultaneously fit parametric models directly on the cause-specific CIF for all k causes, Fk(ti|xk) (k = 1, ⋯ , K), without the requirement of indirect specification through the CSHs. Hence, the likelihood for direct inference on the cause-specific CIF is expressed as,

| (11) |

Note here, however, that, the cause-specific CIF, Fk (t), in Equation 11 is not a proper cumulative distribution function and is instead referred to as a subdistribution function since limt→∞ Fk (t) < 1.19

Flexible parametric regression model for the cause-specific CIF

Like the Cox model, the Fine & Gray model estimates covariate effects but does not specifically model the underlying baseline rates. We propose a parametric survival model which directly estimates both the covariate effects on the cause-specific CIF and the underlying baseline using the likelihood in Equation 11 simultaneously for all K causes. Standard parametric models such as the exponential, Weibull or Gompertz distributions, are often unable to capture more complex underlying baseline hazard functions containing one or more turning points.23 To better capture and represent the behaviour of real world data, a range of flexible parametric models on a variety of scales were introduced by Royston and Parmar.24 Building on the ideas of Royston and Parmar24, we use restricted cubic splines25, sk(ln(t); γk, mk), with M – 1 degrees of freedom where sk represents the spline function for cause k and ln(t) is to indicate operation on a log-time scale and consists of a vector of M knots, m, a vector of M – 1 parameters, γ. At time t = 0, as expected, we must have that the cumulative SDH, is equal to 0. Therefore, by operating on the log-time scale, as t → 0 we also have that Furthermore, log-time has a natural relationship with the Weibull cumulative SDH function when written in logarithmic form. Thus, we end up with the following log-cumulative SDH model which can be specified through a general link function, g(·), for the cause-specific CIF with covariates xk,

| (12) |

Where z1k, ⋯ , z(M–1)k are the basis functions of the RCS and are defined as follows:

| (13) |

where,

| (14) |

and

| (15) |

Usually, M knots are placed at equally spaced centiles of the distribution of the uncensored log-survival times including two boundary knots at the 0th and 100th centiles. The choice of the position and number of knots is subjective, which is used as an argument for a drawback of the flexible parametric modelling framework. However, others have explored this through a variety of sensitivity analyses of the knots and it has been shown to have very little influence on obtained predictions (please refer to Hinchliffe and Lambert26 and Rutherford et. al. 23 for more details).

Link functions

We showed in Equation 12 that we can derive a log-cumulative SDH model with covariates and through the general link function, g(·), for the cause-specific CIF, Fk(t), are able to apply similar transformations described in Royston and Parmar24 for the survival function. Lambert et. al. (submitted) offers more details on the various link functions available for the cause-specific CIF, but here we only introduce specification under a complementary log-log and logit link function.

The majority of regression models are specified through the complementary log-log link function which we will mainly focus on in this paper,

| (16) |

and we can calculate the SDH function for each cause k and the cause-specific CIF, which are defined as follows,

| (17) |

| (18) |

where the βk’s are log-SHRs.

Alternatively, Gerds et. al. 10 argues that specifying regression models on the cause-specific CIF through a logit link function, is advantageous due to simpler interpretation of the parameters as odds ratios. Thus, the general link function becomes,

| (19) |

and the cause-specific CIF is,

| (20) |

The logit link model described above, describes the probability of dying from the competing cause k in relation to the probability of not experiencing the competing event k which includes those that are still alive and those that have already died from one of the other competing events. Gerds et. al.10 argues that, because of this, the logit link models suffers from similar interpretation issues found in the SDH model.

Time-dependent effects to model non-proportionality

In Section, using the link function in Equation 16, we defined a proportional log-cumulative SDH FPM with RCS for the underlying baseline log-cumulative baseline SDH simultaneously for all K causes. A natural advantage of these models is that we can easily extend to incorporate time-dependent effects to model non-proportionality. This is achieved by fitting interactions between the associated covariates and the spline functions. Using this interaction, we can introduce a new set of knots, mek, which represent the eth time-dependent effect for cause k with associated parameters αek. If there are e = 1, ⋯ , E time-dependent effects, we can extend the cause-specific log-cumulative SDH in Equation 25 to,

| (21) |

In this approach, the spline function for different time-dependent effects can be different and requires fewer knots to the baseline spline function.27 This is an extension on the original approach proposed by Royston and Parmar.24 Furthermore, as mentioned previously, the choice of the number and position of these knots has shown to have little influence and is explored more extensively by Bower et. al. 27 As all K causes are modelled, it is also possible to specify different time-dependent effects for the each of the k cause-specific FPM regression model.

Estimating the cure proportion

Andersson et. al. 13 proposed a method that allows estimation of the cure proportion in a FPM framework. In the competing risks scenario, this would occur in a situation where the cause-specific CIF is constant after a certain point in time t. The plateau in the cause-specific CIF can be due to several reasons. The scenario in which is more interesting, is when the CSH becomes 0, which means that, by the relationship in equation 7, the SDH is also 0 for that cause. On the other hand, this plateau can also be observed due to other reasons, for example, when everyone has died from other causes, and there are no patients left who are at risk for the cause of interest. In this case, we want to avoid estimating cure when everyone has died from something else and should only be estimated if we know there are patients who are still at risk at any given time. By adapting the approach described by Andersson et. al. 13, we can estimate the cure proportion from within the flexible parametric log-cumulative SDH model specified in Section by forcing the log cumulative SDH to plateau after the last knot. This involves an adjustment to the way the spline variables are calculated. The first spline is a linear function of log-time and by calculating the splines backwards, the function is forced to be linear after the last knot (see Andersson et. al. 13 for more details). Since the SDH function for cause k on which we model the plateau needs to be evaluated whilst simultaneously modelling all other causes, the final knot must be specified after the final observed time of death. Finally, when we estimate the plateau in a cause-specific CIF, the level of this will depend on the CIF for all other competing events.14 Applying the methods in Andersson et. al. 13 and the above adjustment to a specific cause k = c on which cure is observed, we can fit a flexible parametric cure model with a complementary log-log link for a cause-specific CIF such that,

| (22) |

where,

| (23) |

Therefore, the constant parameters, γ0c and xc are used to model the cure proportion for cause k = c. Here, we also implement a constraint on the linear spline, γ1c, such that it is equal 0.

A useful prediction from these models is the estimate of the proportion of patients that will eventually die, or are bound-to-die, from cancer, or other causes, of those that are still alive. It should be noted, however, that this is a measure at the population level and individual patients are not specified to a particular group. Where a plateau is observed for a particular cause, e.g. cancer, the cancer-specific CIF will no longer increase beyond a given point in time and allows estimation of the proportion of patients bound-to-die of cancer amongst those that are still alive.14 Using these quantities, patients can be partitioned into two separate groups which are separated by the summation of those that are bound-to-die from cancer and the cause-specific CIF for death from competing causes over follow-up time. The two groups, i.e. patients who will ultimately die from their cancer where k = 1, Palive,can(t), and those who will die from competing causes where k = 2, ⋯ , K, Palive,oth(t), can be calculated as follows.

| (24) |

| (25) |

where πc is the proportion of those bound-to-die from cancer on which cure is assumed. These are a useful summary measure of patient prognosis and further complements the direct FPMs on the cause-specific CIFs when interest primarily lies in answering more prognostic-related research questions.

Simulation

Modelling the SDH for a particular cause is usually performed using the Fine & Gray approach and is widely considered as the standard for modelling covariate effects directly on the cause-specific CIF. To contrast this approach against the log-cumulative subdistribution hazards (-CSDH) FPM, we carried out a simple simulation to demonstrate that, like the Fine & Gray model, unbiased estimates are also obtained with good coverage. Furthermore, we will present relative gain in precision (RPG) of modelling under the log-CSDH FPM over the Fine & Gray approach. We also aim to explore a common area of concern around the use of log-CSDH FPM which is in the choice of the number of knots, or degrees of freedom, for the restricted cubic splines. In our simulation results, we hope to echo what has already been shown in previous simulation studies regarding the use of restricted cubic splines in flexible parametric survival models.23

Design

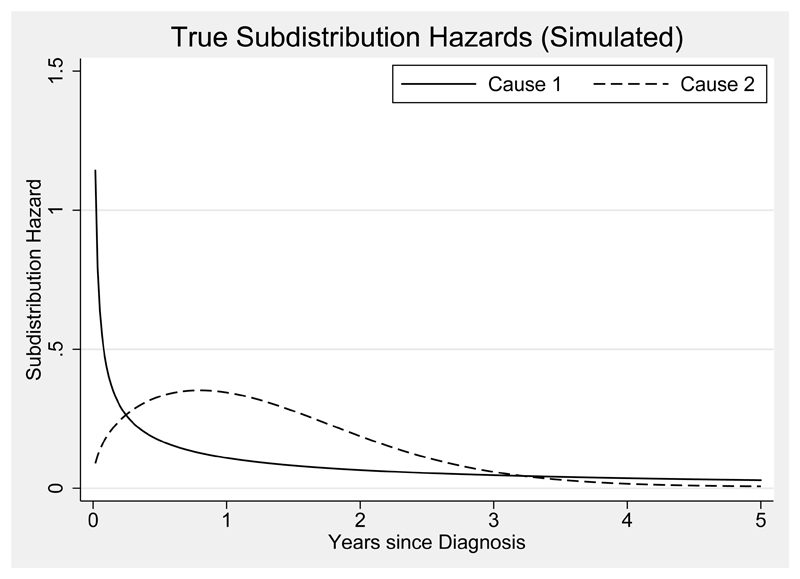

A simulation study was designed with one scenario where true SDH functions were generated for two causes which approached an asymptote of 0. These SDH functions were chosen to demonstrate that restricted cubic splines were robust enough to handle a scenario when there is potential for the optimiser to search in the incorrect direction leading to negative SDHs. The complexity in the shape of SDH functions for both causes were formulated under the mixture Weibull distribution with the assumption of proportionality.

The design of the simulation study is outlined below,

Survival times were generated from CSH functions for both causes which were transformed from SDH functions generated from mixture Weibull distributions using the relationship in equation 7.28 The shape, γ, scale, λ and mixture, p, parameters were chosen such that the SDH functions for both causes tended to an asymptote of 0 (see Figure 1). SDH functions were generated under the assumption of proportionality between the covariate groups for each cause using simulated competing risks data based on CSH functions as derived by Beyersmann et. al. 29 Note that we do not make any proportionality assumptions between the different causes. A censoring distribution was also simulated from an exponential distribution with mean equal to 0.1. Survival and censoring times were combined and an indicator variable for status was generated, choosing the minimum time to death, or censoring time. Administrative censoring was also imposed to restrict follow up time to 5 years.

A binary covariate was simulated from X ~ Uniform(0, 1) where X = 1 if Uniform(0, 1) < 0.5 and X = 0 if Uniform(0, 1) ⩾ 0.5

The binary covariate was assumed to have a proportional effect with a log-SHR of -0.5 for cause 1 and 0.2 for cause 2.

The Fine & Gray model and log-CSDH FPMs with 3, 4, 5, 6 and 9 degrees of freedom were fitted to each of the 1000 simulated datasets containing 200, 500 and 5000 observations.

From each model, log-SHRs and the cause-specific CIF for cause 1 were obtained to determine bias, along with their respective standard errors to calculate root-mean-square-error (rMSE) and 95% CIs for inspecting coverage.

Figure 1.

Subdistribution hazards (SDH) simulated from a mixture Weibull distribution with paramaters λ1,1 = 0.6, γ1,1 = 0.5, λ1,2 = 0.01, γ1,2 = 0.35 and p1 = 0.5 for the SDH for cause 1 and λ2,1 = 0.01, γ2,1 = 0.8, λ2,2 = 0.7, γ2,2 = 1.45 and p2 = 0.5 for cause 2

Results

Table 1 summarises the obtained log-SHRs for cause 1 and standard errors from 1000 replicated datasets with 200, 500 and 5000 observations. The simulation under the above parameters generated a mean of 22% right-censored individuals for 200 and 5000 observations and 23% for 500 observations and a mean of 28% failures from cause 1 for 200, 500 and 5000 observations. The bias, i.e. difference between the model log-SHR and true log-SHR of -0.5, coverage and rMSE is given. Overall, for the models that converge, it is clear that under both the Fine & Gray and FPM approach, we get negligible bias, indicating that all models, irrespective of the number of degrees of freedom used for the baseline RCS, are unbiased. We also demonstrate good coverage in all of the models. Finally, a marginally lower rMSE is observed in all of the log-CSDH FPMs in comparison to the Fine & Gray approach. This demonstrates that, overall, estimates are obtained with a lower bias and more precision under the FPM approach over the standard method.

Table 1.

Simulation results for the log-subdistribution hazard ratio (SHR) and cause-specific cumulative incidence function (CIF) for cause 1 from a proportional subdistribution hazards models with two competing causes and one binary covariate X.

| Log-SHR = -0.5 | CIF for Cause 1 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | Year 3 | Year 5 | ||||||||||||

| N | Code | Converged (%) | Bias | Coverage | rMSE | Bias | Coverage | rMSE | Bias | Coverage | rMSE | Bias | Coverage | rMSE |

| 200 | fg | 100.0 | -0.0295 | 0.9640 | 0.2691 | -0.0004 | 0.9420 | 0.0383 | -0.0004 | 0.9530 | 0.0464 | -0.0003 | 0.9580 | 0.0503 |

| 3df | 95.7 | -0.0248 | 0.9613 | 0.2645 | 0.0018 | 0.9592 | 0.0369 | -0.0020 | 0.9540 | 0.0447 | 0.0026 | 0.9530 | 0.0502 | |

| 4df | 96.0 | -0.0266 | 0.9625 | 0.2633 | 0.0003 | 0.9542 | 0.0375 | -0.0000 | 0.9573 | 0.0451 | 0.0013 | 0.9510 | 0.0501 | |

| 5df | 92.2 | -0.0287 | 0.9642 | 0.2633 | 0.0016 | 0.9469 | 0.0382 | -0.0006 | 0.9501 | 0.0454 | 0.0013 | 0.9523 | 0.0502 | |

| 6df | 93.0 | -0.0255 | 0.9613 | 0.2639 | 0.0002 | 0.9473 | 0.0378 | -0.0007 | 0.9473 | 0.0456 | 0.0004 | 0.9527 | 0.0502 | |

| 9df | 79.2 | -0.0262 | 0.9684 | 0.2592 | 0.0012 | 0.9470 | 0.0378 | 0.0012 | 0.9558 | 0.0458 | 0.0022 | 0.9558 | 0.0498 | |

| 500 | fg | 100.0 | -0.0111 | 0.9600 | 0.1697 | -0.0009 | 0.9620 | 0.0248 | -0.0008 | 0.9540 | 0.0297 | -0.0010 | 0.9580 | 0.0320 |

| 3df | 100.0 | -0.0101 | 0.9600 | 0.1668 | 0.0017 | 0.9560 | 0.0241 | -0.0024 | 0.9600 | 0.0282 | 0.0020 | 0.9660 | 0.0314 | |

| 4df | 100.0 | -0.0115 | 0.9600 | 0.1674 | 0.0001 | 0.9500 | 0.0246 | -0.0002 | 0.9580 | 0.0284 | 0.0005 | 0.9620 | 0.0315 | |

| 5df | 99.0 | -0.0130 | 0.9596 | 0.1675 | 0.0008 | 0.9556 | 0.0247 | -0.0008 | 0.9616 | 0.0285 | 0.0002 | 0.9636 | 0.0314 | |

| 6df | 97.4 | -0.0124 | 0.9589 | 0.1683 | -0.0003 | 0.9610 | 0.0244 | -0.0003 | 0.9610 | 0.0289 | -0.0002 | 0.9589 | 0.0315 | |

| 9df | 97.8 | -0.0127 | 0.9611 | 0.1680 | -0.0003 | 0.9591 | 0.0245 | -0.0004 | 0.9611 | 0.0290 | -0.0003 | 0.9611 | 0.0316 | |

| 5000 | fg | 100.0 | 0.0012 | 0.9570 | 0.0550 | -0.0009 | 0.9560 | 0.0077 | -0.0009 | 0.9450 | 0.0097 | -0.0010 | 0.9510 | 0.0104 |

| 3df | 100.0 | 0.0027 | 0.9560 | 0.0531 | 0.0009 | 0.9750 | 0.0073 | -0.0026 | 0.9510 | 0.0094 | 0.0019 | 0.9370 | 0.0104 | |

| 4df | 100.0 | 0.0014 | 0.9560 | 0.0532 | -0.0007 | 0.9550 | 0.0074 | -0.0007 | 0.9600 | 0.0092 | 0.0002 | 0.9550 | 0.0103 | |

| 5df | 100.0 | 0.0011 | 0.9560 | 0.0532 | 0.0001 | 0.9600 | 0.0075 | -0.0015 | 0.9630 | 0.0093 | -0.0002 | 0.9560 | 0.0103 | |

| 6df | 100.0 | 0.0009 | 0.9560 | 0.0533 | -0.0009 | 0.9600 | 0.0075 | -0.0008 | 0.9600 | 0.0093 | -0.0005 | 0.9560 | 0.0103 | |

| 9df | 100.0 | 0.0008 | 0.9560 | 0.0533 | -0.0008 | 0.9660 | 0.0076 | -0.0007 | 0.9600 | 0.0094 | -0.0007 | 0.9560 | 0.0103 | |

Similarly, also in Table 1, we have the bias, coverage and rMSE for the cause-specific CIFs at 1, 3 and 5 years since diagnosis. Again, we show that there is negligible bias in the estimates from all the models, good coverage is consistently shown over time and we also have similar rMSE across all the models. Overall, the simulation shows that, regardless of the number of degrees of freedom used for the baseline RCS, the parameters are stable across all the models and any differences between them are negligible.

However, convergence issues arise in the smaller simulated datasets for 200 and 500 observations. Non-convergence especially arise when more complicated models are fitted i.e. more degrees of freedoms are used. This suggests potential over-fitting of the models to the data since, for example, using 3 to 4 degrees of freedom in the simulation with 500 observations leads to no problems in model convergence.

Illustrative Example

In this Section, we provide an example to illustrate the different predictions available after fitting a FPM to directly model all cause-specific CIFs. We further demonstrate that we can more accurately capture the shape of the data when fitting FPMs with time-dependent effects to relax the assumption of proportionality. The prediction of other useful predictions to aid interpretation in these more complex models are also demonstrated.

Description of data

We demonstrate the methodology outlined in this paper through the use of SEER public use colorectal data.30 The dataset contains survival information on 35,508 male patients aged between 55 and 84 years old diagnosed with colorectal cancer from 1998 to 2013. The data contain information on whether the patients were at localised or regional stage colorectal cancer at diagnosis. We excluded patients with distant stage cancer due to very high mortality leaving a few patients at risk towards the end of follow up time. Most of these deaths are due to the cancer which means the effect of competing causes of death is small and thus less interesting practically. It is also problematic including such patients for cure models as it can lead to unstable estimates in the tails which can cause some model convergence problems. Furthermore, as discussed in Section, estimating cure is of less interest for distant stage cancer patients since, towards the end of follow up time, nearly everyone dies from their cancer. Analyses included time to death from a total of 3 causes; death from colorectal cancer, other causes and heart disease. Follow up time is restricted to 15 years from diagnosis.

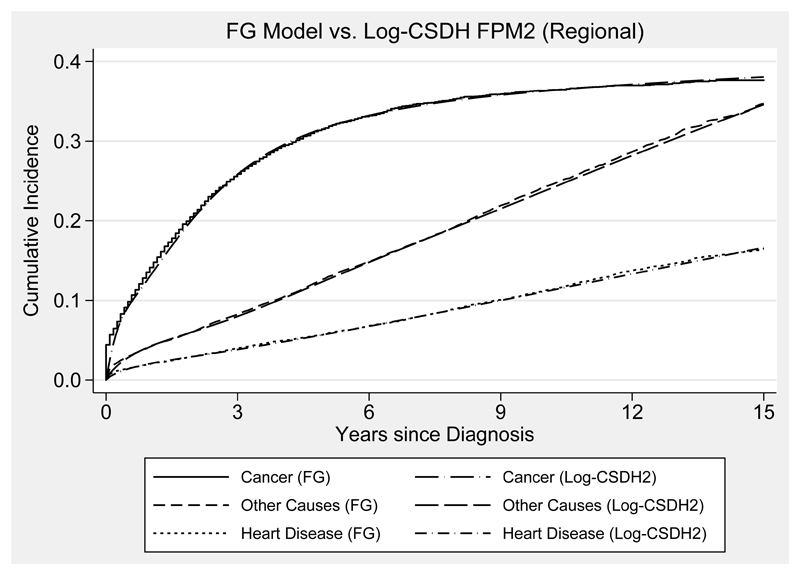

Proportional subdistribution hazards models

Separate Fine & Gray models were fitted for each of the 3 causes with stage at diagnosis as the only covariate. To illustrate the estimation process, we initially restricted analysis to patients aged above 75 years old where competing risks are more likely to make an impact. Parameter estimates are compared against those predicted under the FPM approach which were fitted for the log-cumulative baseline SDH for all 3 causes simultaneously using 5 df for the baseline RCS. Table 2 shows the fitted estimates from a Fine & Gray model and a log-CSDH FPM. The apparent disagreement between the estimated subdistribution hazard ratios (SHRs) and their 95% CIs can be partially explained by the unreasonable assumption of proportionality of the effect of stage at diagnosis for all 3 causes being made on the competing causes in the FPM approach. More complex models were fitted in order to demonstrate this issue by fitting 3 separate log-CSDH FPMs by including time-dependent effects for the other competing events. For this data, because there is non-proportionality, it is accounted for by including time-dependent effects for all causes when modelling using the FPM approach, which is more sensible (see Section). These “adjusted” estimates are also compared in Table 2 which is labelled Log-CSDH FPM2 and good agreement between all SHRs and their 95% CI is now observed. The estimated cause-specific CIFs from both models are illustrated in Figure 2. Here, it is clear that the Fine & Gray Model and Log-CSDH FPM2 yield similar estimates and we observe very good agreement between the two curves.

Table 2.

Subdistribution hazard ratios (SHRs) estimated from a Fine & Gray model, log-cumulative subdistribution hazards flexible parametric model (Log-CSDH FPM) and a Log-CSDH FPM adjusted for time-depedent effects on the competing events (Log-CSDH FPM2). SHRs compare regional stage patients to localised stage patients aged 75 to 84 years old assuming proportionality.

| Fine & Gray Model | Log-CSDH FPM | Log-CSDH FPM2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHR | 95% CI | SHR | 95% CI | SHR | 95% CI | |

| Colorectal: | 3.503 | [ 3.224 3.805 ] | 3.429 | [ 3.157 3.725 ] | 3.504 | [ 3.225 3.808 ] |

| Other Causes: | 0.753 | [ 0.703 0.806 ] | 0.720 | [ 0.673 0.771 ] | 0.737 | [ 0.689 0.789 ] |

| Heart Disease: | 0.731 | [ 0.661 0.807 ] | 0.686 | [ 0.622 0.757 ] | 0.719 | [ 0.651 0.794 ] |

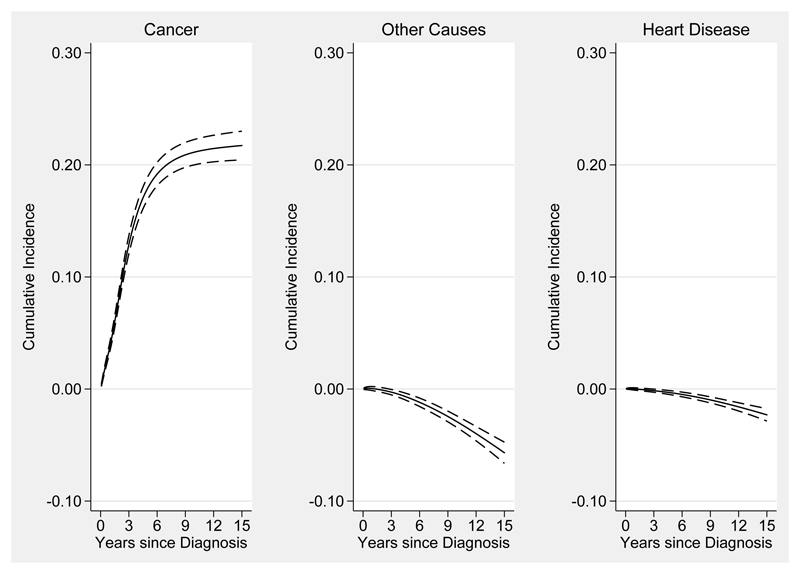

Figure 2.

A comparison of predicted cause-specific cumulative incidence functions from a Fine & Gray (FG) model and a log-cumulative subdistribution hazards flexible parametric model adjusted for time-depedent effects on the competing events (Log-CSDH FPM2). Predictions are made for 75 to 84 year old male patients diagnosed with regional stage colorectal cancer.

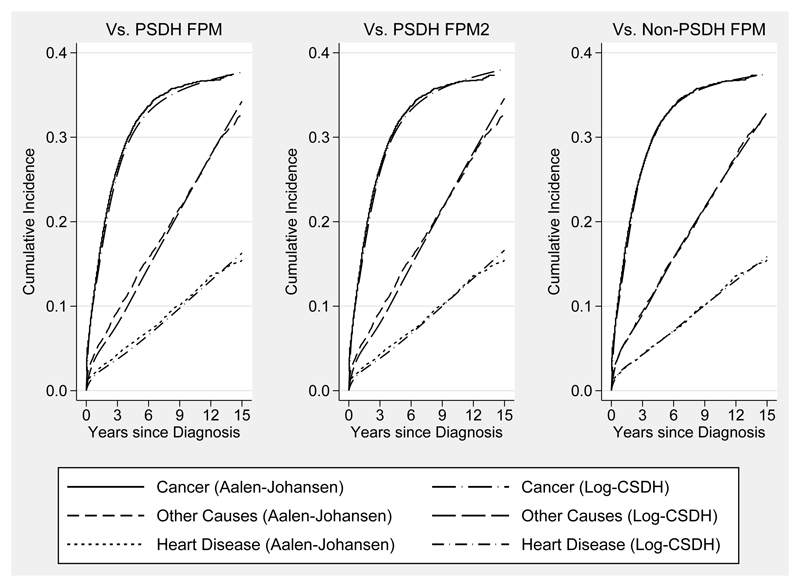

Non-proportional subdistribution hazards models

Generally, the effect of stage on mortality is stronger shortly after diagnosis compared to later on in time, indicating that proportional SDH may not be a reasonable assumption. To relax this assumption, time-dependent effects are included to allow the effect of stage at diagnosis to vary over time for all K causes of death using RCS with 3 df. To assess the accuracy in estimation, predictions from the model are compared to empirical estimates of the SDH for cause k using the Aalen-Johansen estimator for the cause-specific CIF31. Figure 3 shows that this improves the fit of the estimated cause-specific CIFs from the log-CSDH FPM compared to when we assume proportional SDH and now achieve an almost perfect agreement with the non-parametric estimates.

Figure 3.

Predicted cause-specific cumulative incidence functions comparing empirical estimates (Aalen-Johansen) against a proportional log-cumulative subdistribution hazards flexible paramteric model adjusted for time-depedent effects on the competing events (PSDH FPM2) on the right plot and a non-proportional log-cumulative subdistribution hazards flexible parametric model (Non-PSDH FPM) on the left plot. Predictions are made for 75 to 84 year old male patients diagnosed with regional stage colorectal cancer.

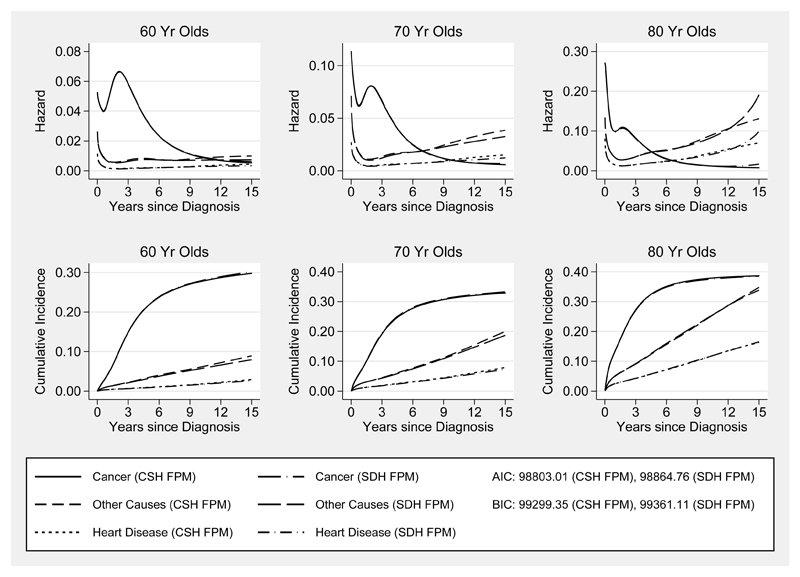

Transforming to the cause-specific hazards

From these log-CSDH regression models, we are also able to estimate the CSH functions since we model the SDH functions for all K causes using Equation 7. We return to analysing the full dataset and in Figure 4, the CSHs derived from a standard flexible parametric CSH regression model, as described by Hinchliffe and Lambert26, are compared to the CSHs calculated from a log-CSDH FPM using Equation 7. Both models use 5 df for the baseline effect and stage and continuous age at diagnosis are also included as covariates allowing for non-linear effects using RCS with 3 df. Time-dependent effects are also included to model non-proportionality for both stage and age with 3 df. The plots in Figure 4 show good agreement between the CSHs estimated from both models. For patients aged 80 years old, there is a small difference at the tails due to an inflated multiplier effect in the transformation as a result of increasingly high mortality and low overall survival. However, because there are very few events, this has a small impact on the estimated cause-specific CIFs. In fact, there is such a good agreement on the cumulative incidence scale that it makes it difficult to distinguish between the two curves.

Figure 4.

Predicted age-specific time-dependent cause-specific hazards and cumulative incidence functions after fitting a non-proportional log-cumulative subdistribution hazards flexible paramteric model (SDH FPM) comapred against a non-proportional cause-specific hazards flexible parametric model (CSH FPM) for 60, 70 and 80 year old male patients diagnosed with regional stage colorectal cancer.

Other useful predictions

The advantage of fitting FPMs and modelling all K causes simultaneously is that it is easy to obtain other predictions which aids interpretation. For example, as shown in Figure 5, we can present absolute differences in the cause-specific CIF for 65 year olds between covariate groups. 95% CIs can be calculated for these measures using the delta method26. The estimated absolute differences show us that, those with a more severe stage cancer at diagnosis, are more likely to die from cancer and less likely to die from other causes and heart disease.

Figure 5.

Absolute differences (regional stage minus localised stage), with 95% CIs (dashed line), between 65 year old patients with local and regional stage cancer at diagnosis.

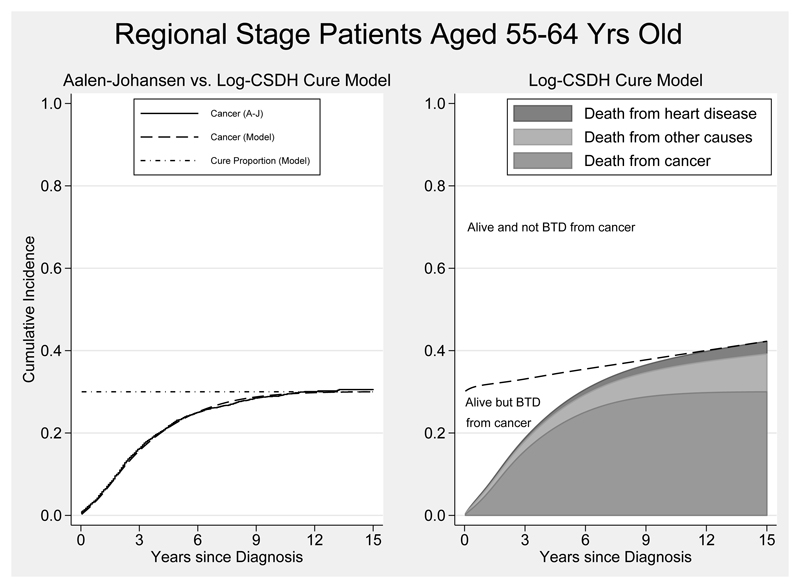

Cure models

In order to fit cure models, it must be reasonable to assume cure on the observed dataset. To assess the appropriateness of the cure assumption for cancer, the Aalen-Johansen empirical estimates were compared against the cancer-specific CIFs estimated from a log-CSDH cure model. Analysis was restricted to patients with regional stage cancer at diagnosis and the youngest age group, i.e. 55 to 64 year olds, where cure is found to be a reasonable assumption. Cure was modelled for patients who died from colorectal cancer and 5 df were used for the baseline RCS in the log-CSDH FPM. From Figure 6, it can be seen that, after approximately 13 years, the empirical curve plateaus at just above 30% and in comparison, the cancer-specific CIF predicted from the model slightly underestimates the cure proportion. Over follow-up time a good agreement is observed between the Aalen-Johansen and model estimates and overall, cure appears to be reasonable. Useful predictions are also estimable from the cure model such as the proportion of patients who are bound to die from cancer, or other causes, of those that are alive. The plot to the right in Figure 6 represents the stacked probabilities for each cause-specific CIF. The cancer-specific CIF plateaus at about 12 years after diagnosis and the cure proportion is estimated at 30%. The dashed-line partitions those who are still alive into two groups. For example, at 3 years after diagnosis, 20% have died and 15% are alive and bound to die from cancer and 65% are alive and not bound to die from cancer. However, at approximately 12 years since diagnosis, as the point of cure is approached, it is expected that, about 40% of patients have died and the remaining 60% are almost all bound to die from causes other than colorectal cancer.

Figure 6.

Predicted cancer-specific cumulative incidence functions (CIFs) for empirical Aalen-Johansen estimates compared against log-cumulative subdistribution hazards (Log-CSDH) estimates from a cure model (left). Stacked cause-specific CIFs and cure proportion (dashed-line) from a Log-CSDH cure model. The dashed-line partitions patients who are still alive into those who are bound to die (BTD) from cancer and not BTD from cancer (right). Predictions obtained for 55 to 64 year old male patients diagnosed with regional stage colorectal cancer.

Discussion

In this paper, extending on the ideas of Jeong and Fine32, we demonstrate a direct likelihood inference approach on the cause-specific CIF under a flexible parametric modelling framework. The direct FPM approach models all cause-specific CIFs simultaneously and offers an alternative to the more widely adopted Fine & Gray model for modelling the SDH function for an individual cause. FPMs extend on standard parametric models by using RCS to better capture real world data which may contain one or more turning points in the baseline SDH function. We also show that, through the use of constraints, a point of cure can be estimated for one (or more) of the cause-specific CIFs.

In general, modelling covariate effects on the cause-specific CIF in large population based studies requires relaxing the proportionality assumption. Including time-dependent effects in the FPM approach to relax the proportionality assumption is much quicker and less computationally intensive as there is no need to incorporate time-dependent weights on an expanded dataset or fit separate models for each of the cause-specific CIFs33,7.

In contrast to the Fine & Gray model, researchers are able to model all cause-specific CIFs simultaneously, which is better for a deeper understanding of the effects of covariates on all cause-specific CIFs and allows us to answer more complicated research questions on patient prognosis. Although these models may be more complex, there are a number of useful estimable measures including absolute differences in the cause-specific CIFs and relative contributions to the total mortality. Accompanied with these predictions, using the delta method, we can also obtain 95% CIs. Although it is also theoretically possible to obtain CIs for predictions from the Fine & Gray model, in practise, this is computationally intensive and is usually done using bootstrapping methods which is not optimal for large datasets. Hence, modelling using the approach in this paper is more accessible and easier to implement for researchers, especially when analysing larger datasets in the hundreds of thousands. Even though our approach estimates parameter effects on the cumulative incidence, because all cause-specific CIFs are modelled together, we show that the CSH functions can be estimated. However, since the multiplier in this equation is time-dependent, although the assumption of proportionality may be reasonable on the SDH scale, this may not also be true on the CSHs and vice versa21.

Another useful property of simultaneously modelling all cause-specific CIFs in a direct likelihood FPM approach, is that the methods can be easily extended to model the cure proportion. The method for estimating cure described by Andersson et. al. 13 for flexible parametric relative survival models was adapted to our approach when cure for a cause-specific CIF is observed to be reasonable in the data. This allows further estimation of some useful predictions such as the estimate of the proportion of patients that will eventually die, or are bound-to-die, from cancer, or other causes, of those that are still alive, as described by Eloranta et. al. 14.

Limitations

A well-known problem of direct regression models for the cause-specific CIF is that the sum of all probabilities may exceed 1 for certain covariate patterns. This is particularly problematic in the oldest age groups where patients are at a higher risk of dying from competing events leading to very high overall probability of death. This is also the case in our approach and it is sometimes avoided if models are not misspecified, for example, by adjusting for all appropriate covariates with any potential interactions and by including time-dependent effects. In some situations models may fail to converge when specified correctly, but this will depend on the use of better initial values for the optimiser so that it is not searching in the wrong direction. As an informal assessment of misspecification of the models, we can compare the CSHs derived from our approach to standard CSH regression modelling methods by allowing for appropriate model complexity on both scales. However, in many datasets, the all-cause CIF will not get close to one, since, in many studies, follow-up is usually restricted. Shi et. al. 34 has previously offered a solution to the constraint problem by modelling a baseline asymptote for one cause-specific CIF, with the remaining CIFs expressed as a function of this plateau. However, the limitation of this is that the one-to-one correspondence between the covariate effects and cause-specific CIF is lost. Alternatively, a non-linear constraint can be imposed to ensure that the all-cause CIF is indeed always bounded by 135.

If interest is only in the covariate effects on one cause, it is not imperative to model all cause-specific CIFs as this may unnecessarily complicate the analysis. In these cases, a single Fine & Gray model may suffice or model the cause-specific CIF using time-dependent weights 33. On the other hand, we argue that there is an advantage to understanding covariate effects on all cause-specific CIFs to get a fuller understanding of the impact of a given covariate.

A potential criticism of the FPM approach is the need to specify the positioning and number of knots. However, this has been shown to have little influence on the cause-specific CIF through sensitivity analyses and other similar studies have also been carried out on the sensitivity of knots26,27,23. An additional concern in the use of splines is that there are no formal constraints to ensure monotonicity of the CIF. Although, in theory, there is a potential that we may observe non-monotonicity in the modelling process because of the lack of constraints, in practise, this is rarely a problem in larger datasets. This is demonstrated in the simulations with 5000 observations where all models converged. In our simulation for 200 and 500 observations, there is a lack of convergence in a small proportion of models which increases with the number of degrees of freedom (see Table 1). These issues in convergence are potentially avoidable through a more refined choice in initial values used in the estimation process. Therefore, when fitting FPMs to smaller data, it is recommended that fewer degrees of freedom are used for the restricted cubic splines.

In smaller simulated datasets, where N = 200, 500, some models struggled to converge under the FPM approach. In these cases, since the likelihood is evaluated at the last observed time for either cause, we found that the reason for non-convergence was mainly attributed down to insufficient follow-up time for a cause which led to inappropriate extrapolation. Other possible reasons for convergence issues in these smaller datasets, as mentioned previously, may be due to the lack of events for a given cause towards the last observed follow-up time and over-fitting models. Therefore, when fitting FPMs to smaller data, such as clinical trial data, it is recommended that fewer degrees of freedom are used for the restricted cubic splines. However, this paper concentrates on the implementation of methods for population-based data which usually contain observations well above 5000. Hence, as demonstrated in the simulation, fitting models using the FPM approach in this scenario show excellent performance regardless of the choice in the number of degrees of freedom.

Conclusions

The choice of analytic approach ultimately depends on the research question to be answered and the scale on which we wish to make our inferences. Our proposed method is most useful when we wish to make inferences on absolute risks and understand covariate effects on all of the cause-specific CIFs simultaneously. As discussed above, there are further advantages of implementation from within a FPM approach. A generalisation of the Weibull distribution with RCS is used to model and more flexibly capture the baseline log-cumulative SDH function. As opposed to standard semi-parametric approaches, since the cumulative SDH function is estimated in FPMs, it is easy to obtain other predictions that facilitate risk communication, some of which have already been discussed. Alternatively, to make inferences on aetiology, the alternative CSH approach for FPMs is available, making it possible to fit equivalent models on both scales. In fact, literature suggests that reporting on both CSH and SDH regression models is advantageous for understanding the overall impact of cancer on risk. CSH functions are also easy to derive from the flexible parametric SDH regression models in this paper since all K causes are modelled simultaneously. Finally, to ensure that the methods are accessible for researchers, a user-friendly command, stpm2cr, is available in Stata36. In the Appendix, the code for fitting the models in Sections, and are included.

Supplementary Material

References

- [1].Wolbers M, Koller MT, Stel VS, Schaer B, Jager KJ, Leffondré K, Heinze G. Competing risks analyses: objectives and approaches. European Heart Journal. 2014 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu131. ehu131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sapir-Pichhadze R, Pintilie M, Tinckam K, Laupacis A, Logan A, Beyene J, Kim S. Survival analysis in the presence of competing risks: the example of wait-listed kidney transplant candidates. American Journal of Transplantation. 2016 doi: 10.1111/ajt.13717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Noordzij M, Leffondré K, van Stralen KJ, Zoccali C, Dekker FW, Jager KJ. When do we need competing risks methods for survival analysis in nephrology? Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2013;28(11):2670–2677. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Koller MT, Raatz H, Steyerberg EW, Wolbers M. Competing risks and the clinical community: irrelevance or ignorance? Statistics in Medicine. 2012;31(11–12):1089–1097. doi: 10.1002/sim.4384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Latouche A, Allignol A, Beyersmann J, Labopin M, Fine JP. A competing risks analysis should report results on all cause-specific hazards and cumulative incidence functions. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2013;66(6):648–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Beyersmann J, Dettenkofer M, Bertz H, Schumacher M. A competing risks analysis of bloodstream infection after stemcell transplantation using subdistribution hazards and cause-specific hazards. Statistics in Medicine. 2007;26(30):5360–5369. doi: 10.1002/sim.3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. Journal of the American statistical association. 1999;94(446):496–509. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fine JP. Regression modeling of competing crude failure probabilities. Biostatistics. 2001;2(1):85–97. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/2.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Jeong JH, Fine J. Direct parametric inference for the cumulative incidence function. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series C (Applied Statistics) 2006;55(2):187–200. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gerds TA, Scheike TH, Andersen PK. Absolute risk regression for competing risks: interpretation, link functions, and prediction. Statistics in Medicine. 2012;31(29):3921–3930. doi: 10.1002/sim.5459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Larson M, Dinse G. A mixture model for the regression analysis of competing risks data. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series C (Applied Statistics) 1985;34:201–211. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dickman PW, Adami HO. Interpreting trends in cancer patient survival. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2006;260(2):103–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Andersson TM, Dickman PW, Eloranta S, Lambert PC. Estimating and modelling cure in population-based cancer studies within the framework of flexible parametric survival models. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2011;11(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Eloranta S, Lambert PC, Andersson TML, Björkholm M, Dickman PW. The application of cure models in the presence of competing risks: a tool for improved risk communication in population-based cancer patient survival. Epidemiology. 2014;25(5):742–748. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Putter H, Fiocco M, Geskus R. Tutorial in biostatistics: competing risks and multi-state models. Statistics in Medicine. 2007;26(11):2389–2430. doi: 10.1002/sim.2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. The Annals of Statistics. 1988:1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Andersen PK, Keiding N. Interpretability and importance of functionals in competing risks and multistate models. Statistics in Medicine. 2012;31(11–12):1074–1088. doi: 10.1002/sim.4385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lau B, Cole SR, Gange SJ. Competing risk regression models for epidemiologic data. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009 doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp107. kwp107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Andersen PK, Geskus RB, de Witte T, Putter H. Competing risks in epidemiology: possibilities and pitfalls. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2012;41(3):861–870. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Grambauer N, Schumacher M, Beyersmann J. Proportional subdistribution hazards modeling offers a summary analysis, even if misspecified. Statistics in Medicine. 2010;29(7–8):875–884. doi: 10.1002/sim.3786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Beyersmann J, Schumacher M. Misspecified regression model for the subdistribution hazard of a competing risk. Statistics in Medicine. 2007;26(7):1649. doi: 10.1002/sim.2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Latouche A, Boisson V, Chevret S, Porcher R. Misspecified regression model for the subdistribution hazard of a competing risk. Statistics in Medicine. 2007;26(5):965–974. doi: 10.1002/sim.2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Rutherford MJ, Crowther MJ, Lambert PC. The use of restricted cubic splines to approximate complex hazard functions in the analysis of time-to-event data: a simulation study. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation. 2015;85(4):777–793. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Royston P, Parmar MK. Flexible parametric proportional-hazards and proportional-odds models for censored survival data, with application to prognostic modelling and estimation of treatment effects. Statistics in Medicine. 2002;21(15):2175–2197. doi: 10.1002/sim.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Statistics in Medicine. 1989;8(5):551–561. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hinchliffe SR, Lambert PC. Flexible parametric modelling of cause-specific hazards to estimate cumulative incidence functions. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2013;13(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bower H, Crowther M, Rutherford MJ, Andersson TML, Clements M, Liu X, Dickman P, Lambert P. Capturing simple and complex time-dependent effects using flexible parametric survival models. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2015 (submitted) [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bender R, Augustin T, Blettner M. Generating survival times to simulate cox proportional hazards models. Statistics in Medicine. 2005 Jun;24(11):1713–1723. doi: 10.1002/sim.2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Beyersmann J, Latouche A, Buchholz A, Schumacher M. Simulating competing risks data in survival analysis. Stat Med. 2009;28(6):956–971. doi: 10.1002/sim.3516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].National Cancer Institute SRPSSB DCCPS. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program ( www.seer.cancer.gov) Research Data (1973-2013) 2016. released april 2016, based on the november 2015 submission. edn.

- [31].Aalen OO, Johansen S. An empirical transition matrix for non-homogeneous Markov chains based on censored observations. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 1978;5(3):141–150. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Jeong JH, Fine JP. Parametric regression on cumulative incidence function. Biostatistics. 2007;8(2):184–196. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxj040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lambert P, Wilkes S, Crowther M. Flexible parametric modelling of the cause-specific cumulative incidence function. Statistics in Medicine. 2016 doi: 10.1002/sim.7208. (submitted) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Shi H, Cheng Y, Jeong JH. Constrained parametric model for simultaneous inference of two cumulative incidence functions. Biometrical Journal. 2013;55(1):82–96. doi: 10.1002/bimj.201200011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Madsen K, Nielsen HB, Tingleff O. Optimization with constraints. IMM, Technical University of Denmark. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- [36].Mozumder SI, Rutherford MJ, Lambert PC. A flexible parametric competing-risks model using a direct likelihood approach for the cause-specific cumulative incidence function. Stata Journal. 2017;17(2):462–489. (28). URL http://www.stata-journal.com/article.html?article=st0482. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.