Abstract

Aim

To evaluate the cost‐effectiveness of IDegLira versus basal‐bolus therapy (BBT) with insulin glargine U100 plus up to 4 times daily insulin aspart for the management of type 2 diabetes in the UK.

Methods

A Microsoft Excel model was used to evaluate the cost‐utility of IDegLira versus BBT over a 1‐year time horizon. Clinical input data were taken from the treat‐to‐target DUAL VII trial, conducted in patients unable to achieve adequate glycaemic control (HbA1c <7.0%) with basal insulin, with IDegLira associated with lower rates of hypoglycaemia and reduced body mass index (BMI) in comparison with BBT, with similar HbA1c reductions. Costs (expressed in GBP) and event‐related disutilities were taken from published sources. Extensive sensitivity analyses were performed.

Results

IDegLira was associated with an improvement of 0.05 quality‐adjusted life years (QALYs) versus BBT, due to reductions in non‐severe hypoglycaemic episodes and BMI with IDegLira. Costs were higher with IDegLira by GBP 303 per patient, leading to an incremental cost‐effectiveness ratio (ICER) of GBP 5924 per QALY gained for IDegLira versus BBT. ICERs remained below GBP 20 000 per QALY gained across a range of sensitivity analyses.

Conclusions

IDegLira is a cost‐effective alternative to BBT with insulin glargine U100 plus insulin aspart, providing equivalent glycaemic control with a simpler treatment regimen for patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on basal insulin in the UK.

Keywords: cost, cost‐effectiveness, diabetes mellitus, GLP‐1 receptor agonist, hypoglycaemia, IDegLira, insulin, UK

1. INTRODUCTION

Diabetes is a well‐characterised metabolic disorder known to affect approximately 6.2% of the UK population, with 2.9 million people estimated to have diabetes nationwide in 2015.1 Type 2 diabetes mellitus accounts for approximately 90% of diabetes cases, and is primarily caused by insulin resistance, with progressive beta‐cell loss eventually leading to insulin deficiency.2, 3 Poor glycaemic control has been linked to an increased risk of diabetes‐related complications, including retinopathy, nephropathy, autonomic nervous system malfunction, diabetic foot (possibly requiring amputation) and increased risk of stroke and myocardial infarction.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) outlined the most recent UK treatment guidelines for people with type 2 diabetes in 2015.12 Evidence‐based, patient‐specific education and lifestyle modification should form the initial basis of treatment. If this proves unsuccessful in controlling blood glucose levels (inadequate control defined as a glycated haemoglobin [HbA1c] level of ≥7.5% [53 mmol/mol]) then metformin should be administered as a first‐line pharmacologic therapy, followed by intensification of therapy as the disease progresses according to patient preferences and multifactorial treatment targets. The combination of metformin with long‐acting basal insulin should be considered an essential therapy for patients with advanced disease not achieving agreed HbA1c targets on current antidiabetic medications.13 However, it has been reported that approximately 64% of patients with type 2 diabetes on basal insulin therapy experience inadequate glycaemic control, with 60% not receiving intensified treatment in a timely manner.14, 15 At this stage, intensification to basal‐bolus insulin therapy is typically recommended. While efficacious in terms of reducing HbA1c, such a treatment regimen is associated with weight gain and high risk of hypoglycaemic episodes. Additionally, the multiple daily injections required represent a more complex treatment regimen. These factors have been linked to reduced patient adherence, leading to impaired glycaemic control.5, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21

A combination of basal insulin plus glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) receptor agonists represents an alternative to basal‐bolus insulin for patients with type 2 diabetes not achieving targets on basal insulin alone. Such a combination takes advantage of the complementary mechanisms of action of the 2 interventions, as GLP‐1 receptor agonists mitigate many of the undesirable side effects associated with basal insulin therapy, particularly weight gain and hypoglycaemia.22 Insulin degludec/liraglutide (IDegLira) combines insulin degludec, a basal insulin therapy with a half‐life of more than 24 h, and liraglutide, a GLP‐1 receptor agonist, in a fixed‐ratio, once‐daily injection.23 The recent 26‐week, non‐inferiority, treat‐to‐target DUAL VII trial compared the efficacy and safety of IDegLira versus a typical basal‐bolus therapy (BBT) in patients with inadequate glycaemic control (HbA1c 7.0%‐10.0%) on basal insulin therapy (20‐50 IU insulin glargine U100 plus metformin).24 BBT consisted of basal insulin glargine U100 (Lantus®) plus bolus insulin aspart (NovoRapid®), with any subsequent mention of insulin glargine U100 and insulin aspart referring to these formulations, unless otherwise stated. The patient population comprised 506 adults with mean age 58.3 years, mean baseline body mass index (BMI) 31.7 kg/m2, mean duration of diabetes 13.2 years, mean HbA1c 8.22% (66 mmol/mol), and mean pre‐trial insulin glargine U100 dose 33.4 IU. Following adjustment for differences between the trial arms, IDegLira and BBT were associated with similar HbA1c reductions (1.48% [16.2 mmol/mol] versus 1.46% [16.0 mmol/mol], respectively), with an estimated treatment difference (ETD) of −0.02% (−0.2 mmol/mol, 95% confidence interval [CI] −0.16% to 0.12% [−1.7 to 1.2 mmol/mol]), as would be expected due to the treat‐to‐target trial design. However, IDegLira was associated with a statistically significant reduction in BMI versus BBT after adjustment for differences between the baseline characteristics of the trial arms (−0.35 kg/m2 versus +0.96 kg/m2, ETD −1.31 [95% CI −1.53 to −1.08 kg/m2]). Additionally, fewer non‐severe hypoglycaemic episodes were observed with IDegLira versus BBT (2.28 versus 10.91 episodes per patient per year, a treatment ratio of 0.21 [95% CI 0.15‐0.30]). Non‐severe hypoglycaemia was defined as an episode that is blood‐glucose confirmed by a plasma glucose value <3.1 mmol/L (56 mg/dL) with or without symptoms consistent with hypoglycaemia but does not meet the American Diabetes Association (ADA) classification of a severe event.

Rates of diabetes‐related complications would not be expected to vary with IDegLira and BBT over the short term, due to the equivalent level of glycaemic control. Instead, assessing the impact of aspects of treatment that affect quality of life in the short term may provide salient information for healthcare payers. The aim of the present analysis was, therefore, to evaluate the short‐term cost‐effectiveness of intensifying therapy with IDegLira versus BBT in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on basal insulin therapy from a healthcare payer perspective in the UK setting.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Model overview

A cost‐utility model was developed in Microsoft Excel to evaluate clinical and economic outcomes associated with IDegLira and BBT with insulin glargine U100 plus insulin aspart over a 1‐year time horizon. The model accounted for pharmacy costs, including medication acquisition costs, required needles and self‐monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) testing, and costs of clinical events, including hypoglycaemic episodes. The model captured quality of life utilities associated with severe and non‐severe hypoglycaemic episodes, and changes in BMI over 25 kg/m2, with a disutility relating to injection frequency applied in a sensitivity analysis. The model reported outcomes in the form of cost breakdowns (expressed in pounds sterling [GBP]), quality of life benefits (measured in quality‐adjusted life years [QALYs]) and the incremental cost‐effectiveness ratio (ICER) in terms of additional cost per QALY gained with IDegLira treatment versus BBT. No discounting was applied as outcomes were not projected beyond 1 year.

2.2. Clinical events and disutilities

Rates of severe and non‐severe hypoglycaemic episodes and changes in BMI associated with IDegLira and BBT were taken from the DUAL VII trial.24 After adjustment for variations in baseline characteristics between the trial arms, IDegLira was associated with reduced frequency versus BBT of both severe (0.0003 vs. 0.0011 episodes per patient per year) and non‐severe (2.28 vs. 10.91 episodes per patient per year) hypoglycaemic episodes, with non‐severe hypoglycaemia defined as an episode that is blood‐glucose confirmed by a plasma glucose value <3.1 mmol/L (56 mg/dL) with or without symptoms consistent with hypoglycaemia, but which does not meet the ADA classification of a severe event (Table 1). Additionally, IDegLira was associated with a mean reduction in BMI of 0.35 kg/m2 per patient, in comparison with a mean increase in BMI of 0.96 kg/m2 per patient for BBT (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of clinical event rates and disutilities used in the base case analysis

| Input description | Input for IDegLira | Input for insulin glargine U100 plus insulin aspart |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical event rates | ||

| Non‐severe hypoglycaemic episodes (per patient per year) | 2.28 | 10.91 |

| Severe hypoglycaemic episodes (per patient per year) | 0.0003 | 0.0011 |

| Change from baseline in BMI (kg/m2) | −0.35 | +0.96 |

| Disutilities | ||

| Disutility per non‐severe hypoglycaemic episode | −0.0050 | |

| Disutility per severe hypoglycaemic episode | −0.0620 | |

| Disutility per 1 kg/m2 increase in BMI over 25 kg/m2 | −0.0061 | |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

Clinical event rates were taken from the DUAL VII trial.24 Disutilities for hypoglycaemia and increases in BMI were sourced from publications by Evans et al. and Bagust and Beale, respectively.25, 26 Non‐severe hypoglycaemia was defined as an episode that is blood‐glucose confirmed by a plasma glucose value <3.1 mmol/L (56 mg/dL) with or without symptoms consistent with hypoglycaemia but which does not meet the ADA classification of a severe event.

Disutilities per severe (−0.0620) and non‐severe (−0.0050) hypoglycaemic episodes were taken from a publication by Evans et al., which used a time trade‐off method with UK‐specific data and valuation of health states by the general population (as recommended by NICE).25 A disutility of −0.0061 per 1 kg/m2 increase in BMI above 25 kg/m2 was taken from the widely‐cited Cost of Diabetes in Europe – Type 2 (CODE‐2) study (Table 1).26

2.3. Medication resource use and costs

Mean daily doses of 40.1 dose steps for IDegLira, 52.7 IU for insulin glargine U100 and 32.3 IU for insulin aspart were used, based on the DUAL VII trial.24 Injection frequency was once daily with IDegLira and 4‐times daily with insulin glargine U100 plus insulin aspart (1 dose of insulin glargine U100 plus 3 bolus doses of insulin aspart), as this was the most common dosing schedule in DUAL VII. Each injection was assumed to be performed by a single, new needle, as recommended by the Forum for Injection Technique (FIT).27 Patients receiving IDegLira were assumed to use 1 SMBG test per day, compared with 4 per day with BBT, as recommended in guidelines issued by Training, Research and Education for Nurses in Diabetes‐United Kingdom (TREND‐UK).28

All costs were accounted from a healthcare payer perspective in pounds sterling (GBP). Annual costs of medications (IDegLira, insulin glargine U100 and insulin aspart), needles, and SMBG testing were based on wholesale acquisition costs (Table 2).29 Direct costs associated with severe hypoglycaemic episodes were based on values reported by Hammer et al., inflated to 2016 values using the Hospital & Community Health Services (HCHS) index.30, 31 Direct costs associated with non‐severe hypoglycaemic episodes were calculated using healthcare resource use reported by Chubb and Tikkanen, with updated unit costs applied (from the Unit Costs of Health and Social Care by the Personal Social Services Research Unit [PSSRU]), and SMBG acquisition costs from MIMS UK.29, 31, 32 No costs were applied to changes in BMI.

Table 2.

Summary of unit costs used in the base case

| Clinical event costs | Cost per episode (GBP) |

|---|---|

| Non‐severe hypoglycaemia | 3.95 |

| Severe hypoglycaemia | 419.60 |

| Pharmacy costs | Pack price (GBP) | Pack contents |

|---|---|---|

| IDegLira | 95.53 | 900 dose steps |

| Insulin glargine U100 (Lantus®) | 37.77 | 1500 IU |

| Insulin aspart (NovoRapid®) | 30.60 | 1500 IU |

| BD MicroFine Ultra™ 4 mm/32 G needles | 9.69 | 100 needles |

| SMBG test strips (Aviva) | 16.09 | 50 strips |

| SMBG lancets (FastClix) | 5.90 | 204 lancets |

2.4. Sensitivity analyses

A series of 1‐way sensitivity analyses were performed to identify key drivers of model outcomes. The upper and lower 95% CIs for the ETDs in BMI and severe and non‐severe hypoglycaemic episodes were applied to assess the impact of alternative clinical inputs. Smaller disutilities for hypoglycaemia, estimated at −0.0118 per severe episode and −0.0035 per non‐severe episode by Currie et al., were explored to assess the contribution of quality of life following these events to modelled outcomes.33 Larger BMI disutilities of −0.0210 (from Ridderstråle et al.) and −0.0100 (from Lee et al.) per each 1 kg/m2 over 25 kg/m2 were used to give a greater impact to weight changes in comparison with the conservative disutility applied in the base case.34, 35 Disutilities to capture the difference in injection frequency with IDegLira and BBT were applied, with twice‐daily injection (comprising 1 basal and 1 bolus injection) and 4‐times daily injection (comprising 1 basal and 3 bolus injections) associated with utility decrements of −0.0460 and −0.0700, respectively, versus once‐daily injection (this range of utility values reflects the variation of the BBT dosing schedule within the DUAL VII trial).24, 34 Alternative costs of severe and non‐severe hypoglycaemic episodes were sourced from a publication by Parekh et al. using the Local Impact of Hypoglycaemia Tool (LIHT), which estimated the cost per severe episode to be GBP 412.92 and the cost per non‐severe episode to be GBP 11.41, compared with GBP 419.60 and GBP 3.95 in the base case, respectively.36

Twice‐daily injection (comprising 1 basal and 1 bolus dose) was applied for BBT, and a scenario in which both needle and SMBG costs were excluded was prepared to evaluate the importance of the costs of consumables to cost‐effectiveness outcomes. Finally, a lower cost comparator (biosimilar insulin glargine [Abasaglar®], approximately 15% less costly than first‐to‐market insulin glargine U100 [Lantus]) was applied in the basal‐bolus regimen with no changes in clinical inputs. It was assumed that this biosimilar had the same efficacy and safety as first‐to‐market insulin glargine U100, but it should be noted that these treatments may not be identical, and approval of the use of biosimilars by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) does not involve any assessment or recommendation regarding interchangeability.37 Further scenarios with biosimilar insulin glargine were evaluated, with a twice‐daily injection regimen (1 basal and 1 bolus injection) with BBT, and needle and SMBG costs excluded.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Base case analysis

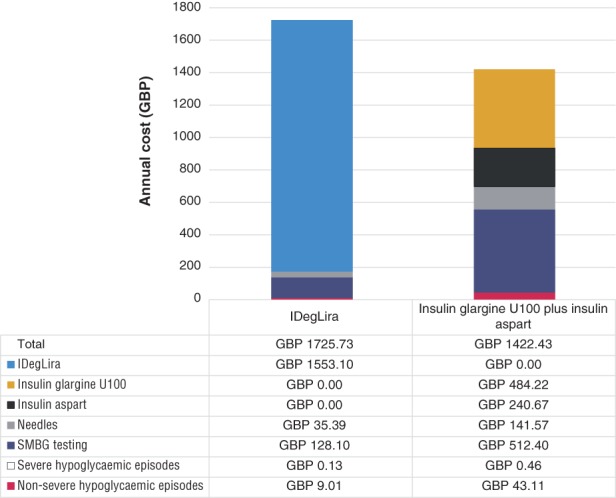

IDegLira was associated with an annual improvement of 0.0512 QALYs versus BBT. This was driven by fewer non‐severe hypoglycaemic events (resulting in a gain of 0.0432 QALYs) and benefits in BMI (resulting in a gain of 0.0080 QALYs) over the 1‐year time horizon of the analysis (Table 3). IDegLira was associated with a higher direct cost than BBT (a total difference of GBP 303) resulting from higher acquisition costs (a cost increase of GBP 828). However, this was partially offset by cost savings associated with avoidance of hypoglycaemic episodes (cost savings of GBP 34), reduced needle use (cost savings of GBP 106) and reduced SMBG resource use (cost savings of GBP 384) (Figure 1). The combination of clinical and cost outcomes to assess cost‐effectiveness resulted in an ICER of GBP 5924 per QALY gained for IDegLira versus BBT with insulin glargine U100 plus insulin aspart for the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes not achieving glycaemic targets on basal insulin.

Table 3.

Utility benefit per patient with IDegLira versus insulin glargine U100 plus insulin aspart

| Aspect of care | Utility benefit with IDegLira (QALYs) |

|---|---|

| Non‐severe hypoglycaemic episodes avoided | +0.0432 |

| Severe hypoglycaemic episodes avoided | +0.0001 |

| Changes in BMI | +0.0080 |

| Total | +0.0512 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; QALYs, quality‐adjusted life years.

Non‐severe hypoglycaemia was defined as an episode that is blood‐glucose confirmed by a plasma glucose value <3.1 mmol/L (56 mg/dL) with or without symptoms consistent with hypoglycaemia but which does not meet the ADA classification of a severe event.

Figure 1.

Summary of total costs per patient per year with IDegLira and insulin glargine U100 plus insulin aspart. Abbreviations: GBP, pounds sterling; SMBG, self‐monitoring of blood glucose

3.2. Sensitivity analyses

ICERs remained below the UK willingness‐to‐pay threshold of GBP 20 000 per QALY gained in all sensitivity analyses (Table 4).38, 39 Application of the upper and lower 95% CIs for BMI and hypoglycaemia ETDs resulted in only small changes in the difference in quality of life reported from the base case, with upper and lower limits for the BMI ETD giving ICERs of GBP 5773 and GBP 6091 per QALY gained, respectively. For hypoglycaemic episodes, the differences were slightly greater, with the ICER falling to GBP 5524 per QALY gained for the upper limit and increasing to GBP 6644 per QALY gained for the lower limit.

Table 4.

Sensitivity analyses results

| Analysis | Difference in quality of life per patient per year (QALYs) | Difference in costs per patient per year (GBP) | ICER (GBP per QALY gained) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base case | +0.0512 | +303 | 5924 |

| Upper 95% CI of BMI ETD | +0.0525 | +303 | 5773 |

| Lower 95% CI of BMI ETD | +0.0498 | +303 | 6091 |

| Upper 95% CI of hypoglycaemia ETD | +0.0544 | +301 | 5524 |

| Lower 95% CI of hypoglycaemia ETD | +0.0462 | +307 | 6644 |

| Currie et al hypoglycaemia disutilities33 | +0.0382 | +303 | 7938 |

| Ridderstråle et al BMI disutility34 | +0.0707 | +303 | 4289 |

| Lee et al BMI disutility35 | +0.0563 | +303 | 5387 |

| Disutility associated with increased injection frequency applied34 | +0.1212 | +303 | 2503 |

| Twice daily injection in basal‐bolus arm | +0.0512 | +630 | 12 311 |

| Parekh et al LIHT hypoglycaemic episode costs36 | +0.0512 | +239 | 4667 |

| Needle and SMBG costs excluded | +0.0512 | +794 | 15 505 |

| Biosimilar glargine in basal‐bolus arm | +0.0512 | +335 | 6548 |

| Biosimilar glargine and twice‐daily injection in basal‐bolus arm | +0.0512 | +662 | 12 935 |

| Biosimilar glargine in basal‐bolus arm and needle and SMBG costs excluded | +0.0512 | +826 | 16 128 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; ETD, estimated treatment difference; GBP, pounds sterling; ICER, incremental cost‐effectiveness ratio; LIHT, Local Impact of Hypoglycaemia Tool; QALYs, quality‐adjusted life years; SMBG, self‐monitoring of blood glucose.

Use of the smaller hypoglycaemia disutilities resulted in a reduced quality of life benefit with IDegLira (+0.0382 QALYs), and the ICER increasing slightly to GBP 7938 per QALY gained. The larger BMI disutilities led to decreased ICERs of GBP 4289 and GBP 5387 per QALY gained when the Ridderstråle et al. and Lee et al. disutilities were applied, respectively. Both were driven by a greater quality of life benefits with IDegLira. Hypoglycaemic event costs calculated using the LIHT resulted in a decreased cost difference of GBP 239, giving an ICER of GBP 4667 per QALY gained.

Application of the disutility for a 4‐times daily injection frequency for BBT (comprising 1 basal and 3 bolus doses) gave by far the largest difference in quality of life seen throughout sensitivity analyses (an increase of 0.1212 QALYs with IDegLira), resulting in the lowest reported ICER of GBP 2503 per QALY gained. Assuming that patients in the BBT arm used only twice‐daily injections (comprising 1 basal and 1 bolus injection) resulted in an increased cost difference of GBP 630, leading to an ICER of GBP 12 311 per QALY gained. Exclusion of needle and SMBG testing costs increased the cost difference even further to GBP 794, with the ICER also increasing to GBP 15 505 per QALY gained.

The biggest variation in costs was seen with the use of a lower‐cost comparator, biosimilar insulin glargine, in the BBT arm with needle and SMBG costs excluded, with the cost difference increasing to GBP 826, leading to an ICER of GBP 16 128 per QALY gained for IDegLira versus BBT. The use of biosimilar glargine with no changes in injection frequency and with a twice‐daily injection regimen (comprising 1 basal and 1 bolus dose) had a smaller impact, with ICERs of GBP 6548 and GBP 12 935 per QALY gained, respectively.

4. DISCUSSION

The present analysis found that IDegLira was associated with an ICER of GBP 5924 per QALY gained versus BBT with insulin glargine U100 plus insulin aspart. This falls below the willingness‐to‐pay threshold of GBP 20 000 per QALY gained in the UK.38, 39 Therefore, IDegLira was considered to be cost‐effective versus BBT with insulin glargine U100 plus insulin aspart for the management of patients with type 2 diabetes in patients experiencing inadequate glycaemic control on a basal insulin regimen in the UK. Quality of life was improved by a significant decrease in non‐severe hypoglycaemic episodes and a reduction, rather than an increase, in BMI. Cost increases were driven predominantly by the higher acquisition cost of IDegLira, but this was partially offset by cost savings associated with reduced use of needles, less SMBG testing, and fewer hypoglycaemic episodes (Figure 1). Avoidance of non‐severe hypoglycaemic episodes was the largest contributor to reduced clinical event costs as, while they are less costly than severe episodes, they occur much more frequently (Figure 1). IDegLira remained cost‐effective in all sensitivity analyses.

Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of insulin degludec and liraglutide for the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes.40, 41 These treatments have complementary modes of action, as GLP‐1 receptor agonists have been shown to mitigate adverse events associated with basal insulin therapy, such as weight gain and high risk of hypoglycaemia.22 This was also seen in the DUAL VII trial, with equivalent reductions in HbA1c (the primary endpoint for the trial) reported for IDegLira and BBT, and the only differences arising in secondary endpoints. BBT is a more complex treatment regimen requiring multiple daily injections, and was associated with an increased risk of hypoglycaemia and weight gain, which have all been shown to reduce patient adherence and quality of life.5, 16, 42, 43 Reduced patient adherence, in turn, may lead to impaired glycaemic control and extra economic burden in real‐world clinical practice (as opposed to the controlled, clinical trial setting of the DUAL VII study).16, 18, 19 Further studies are needed to evaluate any long‐term, real‐world difference in patient adherence between IDegLira and BBT and any subsequent clinical impact that these differences may have.

The rationale for the comparison with BBT was based on the common treatment paradigm of diabetes, whereby patients typically intensify treatment to BBT following failure on basal insulin (with or without additional oral antidiabetic medications), and on the recent DUAL VII clinical trial, which directly compared IDegLira with BBT in this patient population.13, 24 There is no current uniform national or international consensus for the optimal treatment regimen in type 2 diabetes, including the intensification steps beyond monotherapy, the ideal combination when basal insulin is introduced, and the appropriate medications to include in tailored, individualised therapy. IDegLira could therefore offer a viable treatment option for a variety of patients. However, the present analysis only suggests that IDegLira is a cost‐effective alternative in patients with inadequate glycaemic control on a basal insulin regimen compared with BBT, and assertions of cost‐effectiveness at other stages in the treatment paradigm cannot be definitively stated without further study.

One advantage of this short‐term analysis is its simplicity and transparency. Clinical inputs, disutilities and cost values can be easily varied, and the impact of each parameter on quality of life can be readily assessed. Outputs can also be easily explained to patients, allowing informed therapy selection. The analysis is easy to replicate without requiring programming expertise or access to proprietary models of type 2 diabetes (such as the IQVIA CORE Diabetes Model).

In contrast with long‐term models of type 2 diabetes, rates of complications were not included, as they were not expected to vary over the short‐term time horizon of the analysis.44, 45, 46 Furthermore, glycaemic control, a key driver of rates of diabetes‐related complications, was equivalent in both arms. However, rates of diabetes‐related complications can also be influenced by blood pressure, BMI and serum lipid levels, and IDegLira was associated with improvements in all of these risk factors versus BBT in the DUAL VII trial.24 Therefore, it would be expected that complication rates would decrease with long‐term IDegLira treatment.4, 47, 48 The present model is intended to allow for a relatively quick but informative analysis that can complement, rather than replace, conventional long‐term diabetes modelling, which typically projects outcomes (including microvascular and macrovascular complications and their associated impacts on costs and quality of life) over patient lifetimes.49

A limitation of the analysis is the reliance on non‐UK‐specific patient data, as the participants of the DUAL VII study were recruited outside of the UK. However, it is common practice to adapt clinical trial data from multinational cohorts to country‐specific analyses, with this methodology found throughout the published literature.45, 46, 50, 51, 52 Moreover, the effect of IDegLira and BBT would not be expected to vary across the different country settings included in the DUAL VII trial and the UK.

A further limitation is the application of treatment effects for 52 weeks, as the DUAL VII trial concluded after 26 weeks. However, treatment effects displayed stability over the course of the DUAL VII trial, with benefits seen at the start maintained for the full trial duration. Additional studies of diabetes medications have also shown that treatment effects observed at 26 weeks are maintained at 52 weeks.53 Therefore, it can be reasonably assumed that the benefits observed with IDegLira and BBT would be maintained over a 52‐week treatment course.

Across a wide range of sensitivity analyses, ICERs remained under the willingness‐to‐pay threshold of GBP 20 000 per QALY in the UK.38, 39 Sensitivity analyses identified the importance of needle and SMBG costs in driving outcomes, as removing these costs from the analysis increased the ICER to GBP 15 505 per QALY gained for IDegLira versus BBT (the second largest increase seen across the sensitivity analyses). Removal of these costs also contributed to the largest increase in the ICER, seen when these costs were excluded and the cost of biosimilar insulin glargine was applied in the BBT arm. Additionally, including a disutility for the increased 4‐times daily injection frequency associated with BBT (comprising 1 basal and 3 bolus doses) resulted in the biggest decrease in the ICER, falling to GBP 2503 per QALY gained. These data indicate that injection frequency is associated with a potentially important quality‐of‐life burden, concurring with previous studies displaying patient preference for less complex treatment regimens.16 The exclusion of a disutility for injection frequency from the base case analysis reinforces the conservative nature of the analysis, with IDegLira considered cost‐effective despite this. Application of upper and lower 95% CI for ETDs in BMI and hypoglycaemia for IDegLira and BBT resulted in only a minor change in ICERs (all within GBP 750 of the base case estimate), indicating the analysis is robust to plausible changes in the clinical inputs.

In conclusion, IDegLira is a cost‐effective alternative to BBT with insulin glargine U100 plus insulin aspart for patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on basal insulin in the UK. As the recent DUAL VII trial has shown, IDegLira offers equivalent reductions in HbA1c to BBT but provides a less complex treatment regimen and is associated with reduced risk of hypoglycaemic episodes and weight loss rather than weight gain. Further studies are needed to assess the long‐term cost‐effectiveness of IDegLira in the UK, but the present analysis suggests that IDegLira is cost‐effective versus BBT over a 1‐year time horizon.

Conflict of interest

R. S. D. has received speaker and advisory board fees and support for attendance at scientific meetings from Novo Nordisk Ltd. M. D. P. is an employee of Novo Nordisk Ltd. X. Y. L. is an employee of Novo Nordisk A/S. S. M. and B. H. are employees of Ossian Health Economics and Communications, which received consulting fees from Novo Nordisk A/S to support preparation of the analysis.

Author contributions

Russell Drummond, Michelle Du Preez, Xin Ying Lee and Barnaby Hunt contributed to the design of the present study. Michelle Du Preez, Xin Ying Lee and Barnaby Hunt contributed to data collection. Barnaby Hunt and Samuel Malkin conducted the analyses presented. All authors were involved in writing the present manuscript.

Drummond R, Malkin S, Du Preez M, Lee XY, Hunt B. The management of type 2 diabetes with fixed‐ratio combination insulin degludec/liraglutide (IDegLira) versus basal‐bolus therapy (insulin glargine U100 plus insulin aspart): A short‐term cost‐effectiveness analysis in the UK setting. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:2371–2378. 10.1111/dom.13375

Funding information The study was supported by funding from Novo Nordisk A/S.

REFERENCES

- 1. International Diabetes Federation (IDF) . IDF Diabetes Atlas – 8th Edition. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation (IDF); 2017. http://www.diabetesatlas.org/across-the-globe.html. Accessed December 4, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shi Y, Hu FB. The global implications of diabetes and cancer. Lancet. 2014;383(9933):1947‐1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bagust A, Beale S. Deteriorating beta‐cell function in type 2 diabetes: a long‐term model. QJM. 2003;96(4):281‐288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group . Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ. 1998;317(7160):703‐713. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group . Intensive blood‐glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet. 1998;352:837‐853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10‐year follow‐up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1577‐1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ismail‐Beigi F, Craven T, Banerji MA, et al. ACCORD trial group. Effect of intensive treatment of hyperglycaemia on microvascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes: an analysis of the ACCORD randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376:419‐430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. ADVANCE Collaborative Group . Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2560‐2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Duckworth W, Abraira C, Moritz T, et al. VADT Investigators. Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:129‐139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stettler C, Allemann S, Jüni P, et al. Glycemic control and macrovascular disease in types 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus: meta‐analysis of randomized trials. Am Heart J. 2006;152(1):27‐38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Control Group . Intensive glucose control and macrovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009;52(11):2288‐2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) . NICE Guidelines 28. Type 2 Diabetes in Adults: Management. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2015. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28. Accessed October 9, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient‐centered approach. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:140‐149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Giugliano D, Maiorino MI, Bellastella G, Chiodini P, Ceriello A, Esposito K. Efficacy of insulin analogs in achieving the hemoglobin A1c target of <7% in type 2 diabetes: meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(2):510‐517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blak BT, Smith HT, Hards M, Curtis BH, Ivanyi T. Optimization of insulin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: beyond basal insulin. Diabet Med. 2012;29(7):e13‐e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Peyrot M, Barnett AH, Meneghini LF, Schumm‐Draeger PM. Insulin adherence behaviours and barriers in the multinational global attitudes of patients and physicians in insulin therapy study. Diabet Med. 2012;29(5):682‐689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wild D, von Maltzahn R, Brohan E, Christensen T, Clauson P, Gonder‐Frederick L. A critical review of the literature on fear of hypoglycemia in diabetes: implications for diabetes management and patient education. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;68(1):10‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Peyrot M, Skovlund SE, Landgraf R. Epidemiology and correlates of weight worry in the multinational diabetes attitudes, wishes and needs study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(8):1985‐1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Donnelly LA, Morris AD, Evans JM. Adherence to insulin and its association with glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. QJM. 2007;100(6):345‐350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Matza LS, Boye KS, Yurgin N, et al. Utilities and disutilities for type 2 diabetes treatment‐related attributes. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(7):1251‐1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boye KS, Matza LS, Walter KN, Van Brunt K, Palsgrove AC, Tynan A. Utilities and disutilities for attributes of injectable treatments for type 2 diabetes. Eur J Health Econ. 2011;12(3):219‐230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Anderson SL, Trujillo JM. Basal insulin use with GLP‐1 receptor agonists. Diabetes Spectr. 2016;29(3):152‐160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang F, Surh J, Kaur M. Insulin degludec as an ultralong‐acting basal insulin once a day: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2012;5:191‐204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Billings LK, Doshi A, Gouet D, et al. Efficacy and safety of IDegLira versus basal‐bolus insulin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes uncontrolled on metformin and basal insulin; DUAL VII randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:1009‐1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Evans M, Khunti K, Mamdani M, et al. Health‐related quality of life associated with daytime and nocturnal hypoglycaemic events: a time trade‐off survey in five countries. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11(1):90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bagust A, Beale S. Modelling EuroQol health‐related utility values for diabetic complications from CODE‐2 data. Health Econ. 2005;14(3):217‐230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. The Forum for Injection Technique (FIT) . Diabetes care in the UK: The First UK Injection Technique Recommendations. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Becton, Dickinson UK Ltd; 2011. http://www.fit4diabetes.com/files/2613/3102/3031/FIT_Recommendations_Document.pdf. Accessed November 13, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28. TREND‐UK . Blood Glucose Monitoring Guidelines Consensus Document. Version 2.0. Brixworth, UK: TREND‐UK; 2017. http://trend-uk.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/170106-TREND_BG_FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 13, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Database of prescription and generic drugs, clinical guidelines. MIMS UK . Twickenham, UK: Haymarket Media Group; 2018. https://www.mims.co.uk. Accessed April 26, 2018.

- 30. Hammer M, Lammert M, Mejías SM, Kern W, Frier BM. Costs of managing severe hypoglycaemia in three European countries. J Med Econ. 2009;12(4):281‐290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Curtis L, Burns A. Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2016. Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent, Canterbury.

- 32. Chubb B, Tikkanen C. The cost of non‐severe hypoglycaemia in Europe. Value Health. 2015;18(7):A611. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Currie CJ, Morgan CL, Poole CD, Sharplin P, Lammert M, McEwan P. Multivariate models of health‐ related utility and the fear of hypoglycaemia in people with diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(8):1523‐1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ridderstråle M, Evans LM, Jensen HH, et al. Estimating the impact of changes in HbA1c, body weight and insulin injection regimen on health related quality‐of‐life: a time trade off study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee AJ, Morgan CL, Morrissey M, Wittrup‐Jensen KU, Kennedy‐Martin T, Currie CJ. Evaluation of the association between the EQ‐5D (health‐related utility) and body mass index (obesity) in hospital‐treated people with Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes and with no diagnosed diabetes. Diabet Med. 2005;22:1482‐1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Parekh WA, Ashley D, Chubb B, Gillies H, Evans M. Approach to assessing the economic impact of insulin‐ related hypoglycaemia using the novel local impact of hypoglycaemia tool. Diabet Med. 2015;32(9):1156‐1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. European Medicines Agency and the European Commission . Biosimilars in the EU: Information guide for healthcare professionals London, UK: European Medicines Agency; 2017. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Leaflet/2017/05/WC500226648.pdf. Accessed June 13, 2018.

- 38. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Social Value Judgements – Principles for the Development of NICE Guidance. 2nd ed. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2008. https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/what-we-do/Research-and-development/Social-Value-Judgements-principles-for-the-development-of-NICE-guidance.pdf ed. Accessed November 14, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McCabe C, Claxton K, Culyer AJ. The NICE cost‐effectiveness threshold: what it is and what that means. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(9):733‐744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Meneghini L, Atkin SL, Gough SCL, et al. The efficacy and safety of insulin degludec given in variable once‐daily dosing intervals compared with insulin glargine and insulin degludec dosed at the same time daily: a 26‐week, randomized, open‐label, parallel‐group, treat‐to‐target trial in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(4):858‐864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nauck M, Frid A, Hermansen K, et al. the LEAD‐2 Study Group. Efficacy and safety comparison of liraglutide, glimepiride, and placebo, all in combination with metformin, in type 2 diabetes: the LEAD (Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes)‐2 study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(1):84‐90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Walz L, Pettersson B, Rosenqvist U, Deleskog A, Journath G, Wändell P. Impact of symptomatic hypoglycemia on medication adherence, patient satisfaction with treatment, and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;30(8):593‐601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Grandy S, Fox KM, Hardy E. SHIELD Study Group. Association of Weight Loss and Medication Adherence among Adults with Type 2 diabetes mellitus: SHIELD (Study to Help Improve Early evaluation and management of risk factors Leading to Diabetes). Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2013;75:77‐82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hunt B, Mocarski M, Valentine WJ, Langer J. Evaluation of the long‐term cost‐effectiveness of IDegLira versus liraglutide added to basal insulin for patients with type 2 diabetes failing to achieve glycemic control on basal insulin in the USA. J Med Econ. 2017;20(7):663‐670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hunt B, Mocarski M, Valentine WJ, Langer J. IDegLira versus insulin glargine U100: a long‐term cost‐effectiveness analysis in the US setting. Diabetes Ther. 2017;8(3):531‐544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hunt B, Kragh N, McConnachie CC, Valentine WJ, Rossi MC, Montagnoli R. Long‐term cost‐effectiveness of two GLP‐1 receptor agonists for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Italian setting: Liraglutide versus lixisenatide. Clin Ther. 2017;39(7):1347‐1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gaede P, Vedel P, Larsen N, Jensen GV, Parving HH, Pedersen O. Multifactorial intervention and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(5):383‐393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gaede P, Lund‐Andersen H, Parving HH, Pedersen O. Effect of a multifactorial intervention on mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(6):580‐591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. American Diabetes Association Consensus Panel . Guidelines for computer modeling of diabetes and its complications. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(9):2262‐2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Johnston R, Uthman O, Cummins E, et al. Canagliflozin, dapagliflozin and empagliflozin monotherapy for treating type 2 diabetes: systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2017;21(2):1‐218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mezquita‐Raya P, Darbà J, Ascanio M, Ramírez de Arellano A. Cost‐effectiveness analysis of insulin degludec compared with insulin glargine u100 for the management of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus ‐ from the Spanish National Health System perspective. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2017;17(6):587‐595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Russell‐Jones D, Heller SR, Buchs S, Sandberg A, Valentine WJ, Hunt B. Projected long‐term outcomes in patients with type 1 diabetes treated with fast‐acting insulin aspart vs conventional insulin aspart in the UK setting. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19(12):1773‐1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Forst T, Guthrie R, Goldenberg R, et al. Efficacy and safety of canagliflozin over 52 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes on background metformin and pioglitazone. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16(5):467‐477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]