Abstract

Supporting Carers of Children and Adolescents with Eating Disorders in Austria (SUCCEAT) is an intervention for carers of children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa and atypical anorexia nervosa. This paper describes the study protocol for a randomised controlled trial including the process and economic evaluation. Carers are randomly allocated to one of the 2 SUCCEAT intervention formats, either 8 weekly 2‐hr workshop sessions (n = 48) or web‐based modules (n = 48), and compared with a nonrandomised control group (n = 48). SUCCEAT includes the cognitive‐interpersonal model, cognitive behavioural elements, and motivational interviewing. The goal is to provide support for carers to improve their own well‐being and to support their children. Outcome measures include carers' distress, anxiety, depression, expressed emotions, needs, motivation to change, experiences of caregiving, and skills. Further outcome measures are the patients' eating disorder symptoms, emotional problems, behavioural problems, quality of life, motivation to change, and perceived expressed emotions. These are measured before and after the intervention, and 1‐year follow‐up.

Keywords: anorexia nervosa, carers, children and adolescents, skills training, motivational interviewing

1. INTRODUCTION

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a severe mental disorder with high mortality rates compared with other mental disorders (standardised mortality ratio = 5.9, 95% CI [4.2, 8.3]; Chesney, Goodwin, & Fazel, 2014). It is state of the art to involve carers (mostly parents) in the treatment of children and adolescents with eating disorders (EDs; National Institute for Clinical Excellence [NICE], 2017). Caring for a child who suffers from AN can have a serious emotional impact on the parents and lead to distress, anxiety, and depression (Kyriacou, Treasure, & Schmidt, 2008b; Whitney, Haigh, Weinman, & Treasure, 2007; Zabala, Macdonald, & Treasure, 2009).

On the one hand, previous studies have revealed that some parents are likely to show unhelpful behaviours for the patients' outcome, such as accommodating behaviours and dysfunctional interpersonal interactions. It is mostly the mothers of adolescent patients who spend more time involved in care compared with fathers, mainly providing food and emotional support; and they usually report higher levels of distress and accommodating behaviour (Rhind et al., 2016). Family members tend to show accommodating behaviours and reorganise their behaviours around the ED symptoms: For example, they accept meal rituals and low‐calorie foods and turn a blind eye to unwanted behaviours (Sepulveda, Kyriacou, & Treasure, 2009). When both parents are highly accommodating, these accommodating behaviours may maintain the illness and negatively influence the outcome of adolescents (Salerno, Rhind, Hibbs, Micali, Schmidt, Gowers, Macdonald, Goddard, Todd, Lo Coco, et al., 2016a). When the families' level of stress increases, family members are at risk of developing high expressed emotions (HEE; i.e., criticism and emotional overinvolvement; Sepulveda et al., 2010). Anxious parents, for example, might show emotional overinvolvement, which potentially prevents the patients' independence and inhibits their sense of self‐efficacy (Kyriacou, Treasure, & Schmidt, 2008a; Whitney et al., 2005).

On the other hand, there are families who seek help with their caregiving role (Haigh & Treasure, 2003; Zitarosa, de Zwaan, Pfeffer, & Graap, 2012). The importance of supportive interventions for the caregivers of someone with an ED has been demonstrated in various studies (Magill et al., 2016; Schwarte et al., 2017; Spettigue et al., 2015; Treasure et al., 2001). Family therapy has been proven to be effective with adolescent ED patients (Ciao, Accurso, Fitzsimmons‐Craft, Lock, & Le Grange, 2015; Eisler et al., 2016). Strategies to meet the needs of parents of patients with EDs aim to equip parents with knowledge and behaviour change skills. There are different approaches described in the literature: workshops for families (Whitney, Murphy, et al., 2012; Treasure, Whitaker, Todd, & Whitney, 2012), self‐care interventions with the guidance of experienced and trained carers including DVDs (Experienced Carers Helping Others, ECHO; Goddard, Macdonald, Sepulveda, et al., 2011; Goddard, Hibbs, et al., 2013; Goddard, Raenker, et al., 2013; Hibbs, Magill, et al., 2015; Magill et al., 2016), and intervention via the Internet (Grover, Naumann, et al., 2011; Grover, Williams, et al., 2011; Hoyle, Slater, Williams, Schmidt, & Wade, 2013). All of these approaches rely on “The New Maudsley Method” (Treasure, Schmidt, & Macdonald, 2010; Treasure, Smith, & Crane, 2007). The “New Maudsley Method” was developed for the adult carers of adult patients, and little work in this area has been carried out with the carers of adolescent patients. The ‘”New Maudsley Method” was found to reduce carers' HEE (emotional overinvolvement and criticism), distress, burden (Hibbs, Rhind, Leppanen, & Treasure, 2015), anxiety, negative experiences of caregiving (Grover, Naumann, et al., 2011), and time spent caregiving (Hibbs, Magill, et al., 2015). It was shown that the parents' improvement had positive effects on the patients with ED themselves. These included reduction of the ED psychopathology of patients with AN, a reduction of their inpatient bed days (Hibbs, Magill, et al., 2015), an improvement in their quality of life, and an increase in their weight gain (Goddard, Hibbs, et al., 2013; Whitney, Murphy, et al., 2012). Adult patients showed a positive attitude to involving parents in their care (Goddard, Macdonald, & Treasure, 2011).

The previous studies mostly included adult patients and fewer or no adolescent patients. Only one randomised controlled trial (RCT) has examined the effects of the self‐help intervention ECHO for parents of adolescent patients exclusively (13–21 years) so far (Rhind et al., 2014). Parents of adolescents received the training materials (a book and a set of DVDs), and coaches (individuals with experience in caregiving for someone with an ED) provided guidance via telephone. The parents of adolescents rated the intervention favourably and reported positive experiences on account of the ECHO intervention (Goodier et al., 2014). Optimising caregiving skills and reducing accommodating behaviours by the carers could aid the recovery of the patients (Salerno, Rhind, Hibbs, Micali, Schmidt, Gowers, Macdonald, Goddard, Todd, Lo Coco, et al., 2016a; Salerno, Rhind, Hibbs, Micali, Schmidt, Gowers, Macdonald, Goddard, Todd, Tchanturia, et al., 2016b).

A recent meta‐analysis of interventions for parents of children with EDs highlights a clear need for RCTs that include outcomes for the children and adolescents (Hibbs, Rhind, Leppanen, et al., 2015). In addition, there is also a need to make interventions for parents cost‐effective (Roick et al., 2001), available, and affordable (Fairburn & Patel, 2014).

Supporting Carers of Children and Adolescents with Eating Disorders in Austria (SUCCEAT) is based on “The New Maudsley Method” (MacDonald, Todd, Whitaker, Creasy, Langley, & Treasure, in prep.; Schmidt & Treasure, 2006; Treasure et al., 2010; Treasure, Smith, et al., 2007). For the SUCCEAT intervention, the material from “The New Maudsley Method” was adapted as a therapeutic 8‐week intervention for use with carers of children and adolescents (see Table 1). These were translated into German and also adapted to a German‐speaking cultural context (Treasure et al., in prep.). This is the first protocol for an RCT, which compares workshop support groups with web‐based support groups directly and also includes outcome of patients younger than 13 years (10–19 years).

Table 1.

SUCCEAT intervention components based on the cognitive‐interpersonal maintenance modela

| Content of eight SUCCEAT workshops sessions and web‐based modules | Aims | |

|---|---|---|

|

Aetiology of anorexia nervosa; explanation of relationship patterns: high expressed emotions, caring styles, and animal models | Knowledge about the illness, caring with just enough control, compassion, and consistency |

|

Effects of anorexia nervosa on the brain, thinking styles, obsessive‐compulsive personality traits, and self‐compassion | Recognising one's own thinking styles and personality traits, increasing flexibility, and being self‐compassionate |

|

Transtheoretical Model of change (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984), eliciting confidence, importance, and readiness to change | Recognizing the different stages of change and supporting changes in these different stages |

|

Introduction to Motivational Interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 2002), main principles of reflective listening and communication | Expressing empathy, motivating change, rolling with resistance, and supporting self‐efficacy |

|

Enhancement of Motivational Interviewing, communication tools: reflection, reframing, etc. | Initiating change talk (refers to desire, ability, reasons, and needs to change) and avoiding communication traps |

|

Improving emotional intelligence and managing personality traits (perfectionism and avoidance) | Supporting emotional self‐regulation |

|

Coping with difficult behaviours, elements of cognitive behavioural therapy: Antecedent–Behaviour–Consequence (ABC model; Ellis, 1973) | Changing antecedents, behaviours, and consequences |

|

Recognising recovery, complete remission, and partial remission; crisis management | Preventing relapses |

| Additional material offered to the carers | ||

| DVDb |

Instructions explain communication skills and animal models Role play scenarios show examples for disadvantageous and advantageous communication Audio files give examples of providing meal support |

|

| SUCCEAT workbook |

Summarises and extends the contents of the intervention, and contains further information and exercises One chapter informs the patients about the intervention |

|

Note. SUCCEAT = Supporting Carers of Children and Adolescents with Eating Disorders in Austria.

MacDonald, Todd, Whitaker, Creasy, Langley & Treasure, in prep.; Treasure et al. (2010); Treasure, Smith, et al. (2007); Schmidt and Treasure (2006); and Treasure and Schmidt (2013).

How to Care for Someone with an Eating Disorder (The Succeed Foundation, 2011; German translation of our research group).

1.1. Theoretical background of the SUCCEAT intervention

The SUCCEAT intervention highlights several benefits of “The New Maudsley Method” (Treasure, Smith, et al., 2007; Treasure et al., 2010; Treasure & Nazar, 2016). “The New Maudsley Method” consists of psychoeducation (e.g., aetiology of EDs, the effects of starvation on the brain, emotional self‐regulation, and personality traits) and communication tools; and it incorporates different theoretical models:

Motivational Interviewing (MI; Miller & Rollnick, 2002),

the cognitive‐interpersonal maintenance model (Goddard, Salerno, et al., 2013; Schmidt & Treasure, 2006; Treasure & Schmidt, 2013),

the Antecedent–Behaviour–Consequence model (ABC model; Ellis, 1973), and

the Transtheoretical Model of Change (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984).

Besides the focus on MI in two workshop sessions and web‐based modules, respectively (see Table 1), the whole SUCCEAT intervention provides skills for behaviour change through an MI framework (Miller & Rollnick, 2002; Treasure et al., 2012). The coaches from the SUCCEAT intervention act as role models and use MI to enable the parents to be self‐compassionate and to care for themselves (Schulz von Thun, 1981; Sepulveda, Lopez, Todd, Whitaker, & Treasure, 2008). The parents learn how to apply MI: to express empathy, to motivate change through discrepancy, to roll with resistance, and to support self‐efficacy (Sepulveda, Lopez, Macdonald, & Treasure, 2008).

The SUCCEAT intervention is based upon the cognitive‐interpersonal maintenance model of AN (Schmidt & Treasure, 2006; Treasure & Schmidt, 2013). This model proposes that the following factors cause and maintain EDs: (1.) obsessive–compulsive personality traits, (2.) avoidance as a personality characteristic, (3.) positive beliefs about the illness, and (4.) responses of close others.

Obsessive–compulsive personality traits, such as perfectionism and rigidity in patients with AN, can lead to attention to details and a fear of making mistakes, which may cause the illness to be maintained (Crane, Roberts, & Treasure, 2007; Swinbourne et al., 2012; Treasure et al., 2008).

Patients with AN tend to avoid experiences, intense emotions, and close relationships (Krug et al., 2012; Russell, Schmidt, Doherty, Young, & Tchanturia, 2009; Zabala et al., 2009). As a result of the loss of brain power, starvation may increase avoidance and rigidity (Anderluh, Tchanturia, Rabe‐Hesketh, & Treasure, 2003; Cardi et al., 2017; Cardi, Di Matteo, Corfield, & Treasure, 2012; Davies, Schmidt, Stahl, & Tchanturia, 2011; Sternheim et al., 2012; Treasure & Russell, 2011; Treasure, Sepulveda, et al., 2007). Some parents share obsessive–compulsive and avoidant personality traits (Fassino et al., 2002; Treasure et al., 2008; Treasure & Cardi, 2017; Ward et al., 2001). As parents often serve as a role model for their children, SUCCEAT teaches the parents how to show flexible behaviour (Harrison, Tchanturia, Naumann, & Treasure, 2012; Roberts, Tchanturia, Stahl, Southgate, & Treasure, 2007), to pay less attention to details (Goddard, Raenker, et al., 2013), and to overcome the fear of making mistakes (Goddard, Raenker, et al., 2013; Kanakam, Raoult, Collier, & Treasure, 2012).

Many patients with AN have positive beliefs about their illness. The patients believe that the illness helps them to feel in control, to feel special and powerful, to cope with emotions, and to have a sense of autonomy (Branch & Eurman, 1980; Serpell, Teasdale, Troop, & Treasure, 2004). To address these positive beliefs, parents are equipped with skills to help their children to reach these positive feelings (control, autonomy, etc.) by other means than the ED (Treasure, 2016b).

Several distressing ED symptoms make the parents anxious (Treasure et al., 2008). Parents sometimes try to reduce their anxiety by using HEE. Animal metaphors are used to reflect dysfunctional interaction styles (Sepulveda, Lopez, Macdonald, et al., 2008). SUCCEAT emphasises the importance of collaborative caregiving. Parents are equipped with health promoting skills, function as partners of the professionals, and work like cotherapists towards patients' recovery (Macdonald, Murray, Goddard, & Treasure, 2011; Sepulveda, Lopez, Todd, et al., 2008). Carers are taught how to give just enough guidance and to care for the patient with warmth, compassion, and consistency (Gilbert, 2009).

Some ED behaviours of the patients have become automated habits (e.g., over‐exercising, vomiting, and fasting) and are no longer related to goals (Nazar et al., 2017), and some patients use the ED behaviours to deal with stressful situations (Treasure et al., 2008). One strategy to change difficult behaviours is the ABC model (Ellis, 1973). The ABC model from cognitive behavioural therapy enables the parents to help the patients change their difficult behaviours by changing antecedents (e.g., creating a comfortable atmosphere before dinner), changing their own behaviour (e.g., talking about pleasant themes during dinner), and consequences (e.g., going for a walk together after dinner). Another strategy to change difficult behaviours is changing it according to the Transtheoretical Model of Change (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984). Carers are trained to identify which stage of change they are in themselves and which stage the patient is in (Treasure, 2016a; Whitney, Currin, Murray, & Treasure, 2012). Parents are taught how to support change in the different stages (Treasure, Sepulveda, et al., 2007). The SUCCEAT intervention informs the parents that patients sometimes relapse and need to go through repeated cycles of the stages of change (Hibbs, Magill, et al., 2015; McKnight & Boughton, 2009; Taborelli et al., 2016). The different theoretical models combine intrapersonal and interpersonal factors, as well as knowledge and skills, that can help parents to manage their own reaction to the illness and to provide an environment that is conducive to change (Treasure et al., 2010).

1.2. The SUCCEAT trial aims

There are three main goals of the SUCCEAT intervention: first, to increase the well‐being of the carers in order to reduce their own risk of developing a mental disorder; second, to support children's and adolescents' recovery from EDs; and third, to attain long‐term changes in the communication within the families to prevent patients from relapsing. A long‐term goal is to provide low‐threshold, cost‐effective, time‐efficient, and transregional support for carers in the future.

1.3. Hypotheses

The outcome measures are mentioned in brackets. These outcome measures are described in more detail in Table 2 and in Supplement S1.

Table 2.

Outcome measures of the RCT

| Instrument | Abbrev. | Domain | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Health Questionnaire (Linden et al., 1996) | GHQ | Psychological morbidity and distressa | PO, C |

| Eating Disorder Examination (Hilbert & Tuschen‐Caffier, 2006) | EDE | ED symptomatologyb | PO, P |

| Eating Disorder Inventory‐2 (Paul & Thiel, 2005) | EDI‐2 | Various dimensions of EDsa | PO, P |

| Caregiver Skills (Hibbs, Rhind, Salerno, et al., 2015, c) | CASK | Skills to support a child with an EDa | SO, C |

| Experience of Caregiving Inventory (Szmukler et al., 1996, c) | ECI | Experiences in caringa | SO, C |

| Eating Disorder Symptom Impact Scale (Sepulveda, Whitney, Hankins, & Treasure, 2008, c) | EDSIS | Burden concerning caring for a child with an EDa | SO, C |

| Carers' Needs Assessment Measure (Graap et al., 2005) | CaNAM | Unmet needs respective caringa | SO, C |

| Symptom Checklist 90 (Franke, 2002) | SCL‐90 | Psychiatric symptomatologya | SO, C |

| Beck Depression Inventory‐II (Hautzinger, Keller, & Kühner, 2006) | BDI‐II | Depressive symptomatologya | SO, C |

| State‐Trait‐Anxiety Inventory (Laux, Glanzmann, Schaffner, & Spielberger, 1981) | STAI | State and trait anxietya | SO, C |

| Family Questionnaire (Wiedemann, Rayki, Feinstein, & Hahlweg, 2002) | FQ | High expressed emotionsa | SO, C |

| University of Rhode Island Change Assessment Scale (Hasler, Klanghofer, & Buddeberg, 2003) | FEVER | Readiness for changea | SO, C |

| Body Mass Index (clinical measures of height and weight) | BMI | Weight statusa | SO, P |

| Youth Self‐Report (Arbeitsgruppe Deutsche Child Behavior Checklist, 1998) | YSR | Behavioural, emotional problemsa | SO, P |

| Health‐Related Quality of Life Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents (Ravens‐Sieberer & Bullinger, 1998a, 1998b) | KINDL | Quality of lifea | SO, P |

| Family Emotional Involvement and Criticism Scale (Kronmüller et al., 2001) | FEIWK | Perceived HEEa | SO, P |

| Anorexia Nervosa Stages of Change Questionnaire (Rieger, Touyz, & Beumont, 2002, c) | ANSOCQ | Readiness to recover from ANa | SO, P |

| SUCCEAT Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire | Feasibility and acceptability of the SUCCEAT intervention | C, Process evaluation | |

| Client Sociodemographic and Service Receipt Inventory (Roick et al., 2001) | CSSRI | Cost‐effectiveness | C, P Economic evaluation |

Note. SUCCEAT = Supporting Carers of Children and Adolescents with Eating Disorders in Austria; RCT = randomised controlled trial; HEE = high expressed emotions; AN = anorexia nervosa; PO = primary outcome; SO = secondary outcome; C = carers' assessment; P = patients' assessment; ED = eating disorder;

Self‐report measure.

Semistructured interview.

German translation of our research group with back translations by an English native‐speaking psychologist.

1.3.1. Primary hypothesis—Carers

-

1

Carers participating in the SUCCEAT intervention groups will report a greater reduction of distress (General Health Questionnaire: Linden et al., 1996) at postintervention (T1) than the carers in the control group.

1.3.2. Primary hypothesis—Patients

1.3.3. Secondary hypotheses

-

3

There will be differences in improvement of carers' and patients' outcome variables between the two SUCCEAT intervention groups (workshop support groups vs. web‐based support groups).

-

4

Carers participating in the SUCCEAT intervention groups will report a greater reduction of burden (Eating Disorder Symptom Impact Scale: Sepulveda, Whitney, et al., 2008), as well as psychiatric symptomatology (Symptom Checklist 90: Franke, 2002), anxiety (State–Trait Anxiety Inventory: Laux et al., 1981), depression (Beck Depression Inventory II: Hautzinger et al., 2006), HEE (Family Questionnaire: Wiedemann et al., 2002), and unmet needs (Carers' Needs Assessment Measure: Graap et al., 2005) at postintervention (T1) than the carers in the control group. Further, they will report a greater increase of motivation to change (University of Rhode Island Change Assessment Scale: Hasler et al., 2003), positive experiences of caregiving (Experience of Caregiving Inventory: Szmukler et al., 1996), and caregiving skills (Caregiver Skills: Hibbs, Rhind, Salerno, et al., 2015) at postintervention (T1) than the carers in the control group.

-

5

Carers will report acceptability and satisfaction with the SUCCEAT intervention (SUCCEAT Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire).

-

6

Patients whose carers participate in the SUCCEAT intervention groups will show a greater reduction of behavioural and emotional problems (Youth Self‐Report: Arbeitsgruppe Deutsche Child Behavior Checklist, 1998) and perceived HEE (Family Emotional Involvement and Criticism Scale: Kronmüller et al., 2001), as well as a greater increase of Body Mass Index, quality of life (Health‐Related Quality of Life Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents: Ravens‐Sieberer & Bullinger, 1998a, 1998b), and motivation to change (Anorexia Nervosa Stages of Change Questionnaire: Rieger et al., 2002) at postintervention (T1) than the patients in the control group.

-

7

Outcome variables of the carers participating in the SUCCEAT intervention groups and their patients will remain stable at follow‐up (T2) compared with postintervention (T1).

-

8

The costs of support (Client Sociodemographic and Service Receipt Inventory: Roick et al., 2001) will be lower for carers (and their patients) participating in the SUCCEAT intervention groups at postintervention (T1) and at follow‐up (T2) than for the carers (and their patients) in the control group.

2. METHODS

2.1. Trial design

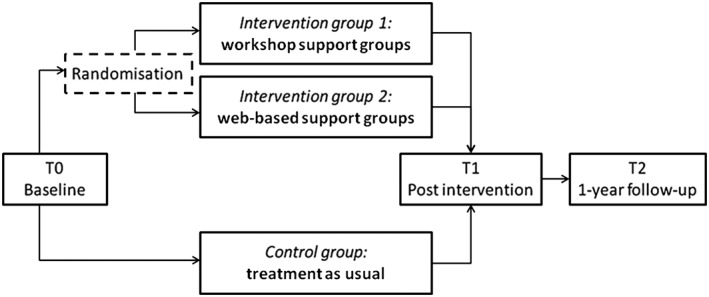

SUCCEAT is a two‐arm multicentre, parallel group RCT with a nonrandomised control group (see Figure 1). Incoming patients are screened for AN or atypical AN and are randomly allocated to the Intervention group 1 (workshop support groups) or the Intervention group 2 (web‐based support groups), respectively, in addition to treatment as usual (TAU), and compared with a nonrandomised control group (TAU). The study is conducted in Austria and Germany.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the trial design of the intervention: Supporting Carers of Children and Adolescents with Eating Disorders in Austria

2.2. Participants

2.2.1. Eligibility criteria for participants

The following are the inclusion criteria for children and adolescents:

Age between 10 and 19 years

Diagnosis of AN (F50.0) or atypical AN (F50.1) according to the International Classification of Diseases (World Health Organization, 1990)

Fluent German in order to answer outcome questionnaires

Ability to provide informed consent

Children and adolescents have to receive TAU according to the NICE guidelines (NICE, 2017). TAU is multidisciplinary, coordinated between services, and includes psychological treatment, psychoeducation, and monitoring of weight, mental, and physical health. Psychological treatment for children and young people includes sessions without and together with their family members (for further information, see Section 2.3.2). The frequency and duration of the psychological treatment for the patients depend on their needs. Dietary counselling and medication for the patients are only offered as part of a multidisciplinary approach. For patients with an acute mental health risk, psychiatric inpatient care is considered. Patients whose physical health is severely compromised are admitted to inpatient or day‐patient service for medical stabilisation and to initiate refeeding, if these cannot be done in an outpatient setting.

The following are the exclusion criteria for children and adolescents:

Severe comorbidity at baseline (e.g., psychosis)

No main carer (e.g., live in a children's home with no contact to own family)

The following are the inclusion criteria for main carers who complete outcome assessment:

Ability to provide informed consent

The main carer has to speak German fluently in order to answer the outcome questionnaires. The main carer is the one who spends the most time with the patient. Only the main carer will answer the questionnaires about the outcome measures. Besides the main carer, other family members and carers are also invited to take part in the intervention.

The following are the exclusion criteria for main carers:

Severe morbidity at baseline, which prevents carers from participating in the RCT (e.g., acute inpatient treatment because of physical illness)

Carers without internet access (85% of Austrian and 92% of German households have internet access; European Commission, 2016)

2.2.2. Study settings and locations where the data will be collected

Patients and carers will be recruited at different inpatient and outpatient centres with ED units, where they receive TAU. Carers and patients who meet the eligibility criteria are invited to participate in the study. Patients and carers both give their informed consent, and parents give their informed consent for children who are minors.

Carers and patients of the two SUCCEAT intervention groups will be recruited at the Medical University of Vienna, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and by consultant child and adolescent psychiatrists and at different centres with ED units in adjacent federal states to Vienna. Patients and carers in the two intervention groups give their informed consent and complete the questionnaires at the Medical University of Vienna, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

For the control group, patients and their carers will be recruited and receive TAU at three centres: at the Wilhelminenspital in Vienna, Department of Child and Adolescent Medicine, Inpatient and Outpatient Unit for Children and Adolescents; at the Clinical Centre Klagenfurt, Department of Neurology and Psychiatry for Children and Adolescents; and at the Parkland‐Clinic for Psychosomatic and Psychotherapy in Bad Wildungen, Germany. Patients and carers in the control group give their informed consent and complete the questionnaires at the recruiting site.

The interventions started in November 2014 and will continue approximately until April 2018. Follow‐up assessments for the remaining patients are expected to be completed by April 2019. The main ethics approval has been granted by the Medical University of Vienna Ethics Committee (1840/2013). Site‐specific ethics approvals are granted for all participating sites.

2.3. Treatment arms

2.3.1. SUCCEAT intervention

The SUCCEAT intervention consists of eight weekly workshop sessions and web‐based modules respectively (see Table 1 for content), a SUCCEAT workbook, and the DVD How to Care for Someone with an Eating Disorder (The Succeed Foundation, 2011; German translation by our research group). The SUCCEAT workshop support groups and SUCCEAT web‐based support groups consist of the same content and are designed to encourage the carers to read the materials, watch the DVD, and try new behaviours as “experiments” at home. The contents of the intervention and the DVD were translated into the German language and adapted to a German‐speaking cultural context (e.g., German names of actors and meals and topics of the conversations: lyrics from a German singer) prior to the study by the SUCCEAT research group. The audio track of the DVD How to Care for Someone with an Eating Disorder (The Succeed Foundation, 2011) has been synchronised to the German language, and the texts have been translated. Almost all of the scenes in the DVD show young patients who still live with their parents. Therefore, the DVD is applicable to the carers of adolescent patients in our RCT. One scene shows a young adult patient (who already lives with her partner), but the content of the scene (over‐exercising) is also applicable to patients who are minors. Carers of patients with ED (who were not included in the study) tested the German materials prior to the study and gave us feedback. The DVD shows examples for communication with HEE and the same scenarios with good communication incorporating change (e.g., a family with a child with AN in a restaurant and shopping for food with a daughter suffering from AN).

Both intervention groups (workshop support groups and web‐based support groups) will involve six subgroups. Each subgroup will include the carers of about eight patients. The same two professional SUCCEAT coaches guide all the carers in each of the SUCCEAT workshop support groups and in the SUCCEAT web‐based support groups. One coach is a consultant psychiatrist, child and adolescent psychiatrist, and psychotherapist; and the other coach is a senior registrar in child and adolescent psychiatry and a psychologist. The two coaches were trained in a 2‐day workshop by Gill Todd (e.g., Salerno, Rhind, Hibbs, Micali, Schmidt, Gowers, Macdonald, Goddard, Todd, Tchanturia, et al., 2016b), who is experienced in working with carers of patients with ED applying “The New Maudsley Method” (Treasure et al., 2010; Treasure, Smith, et al., 2007).

SUCCEAT Intervention group 1—Workshop support groups for carers

All SUCCEAT workshop support groups are held at the Medical University of Vienna, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, once in a week in the evening (from 6 p.m. to 8 p.m.) and consist of eight weekly workshop sessions (see Table 1). Carers receive the SUCCEAT workbook as a hardcopy and the DVD (The Succeed Foundation, 2011; German translation of our research group) at the first workshop session. The two SUCCEAT coaches present the contents of the SUCCEAT intervention listed in Table 1 with a PowerPoint presentation and support the carers personally during the sessions. In each session, the carers will get a hardcopy handout with a summary of the workshop session. The workshops are designed to be interactive with role plays and group work for the carers. The carers are encouraged to talk about their concerns and experiences with each other. They have time to report their “experiments” and to reflect together.

SUCCEAT Intervention group 2—Web‐based support groups for carers

All the carers get to know the two SUCCEAT coaches and the other participating carers of their web‐based support group personally in a welcome meeting at the beginning of the intervention at the Medical University of Vienna, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and subsequently complete the programme at home via Internet. The web‐based support groups consist of eight weekly web‐based modules (see Table 1). The SUCCEAT web‐based modules and the SUCCEAT workbook are available on a website within a structured program (http://www.succeat.at). The formal conditions are introduced at the welcome meeting, and the carers receive the DVD (The Succeed Foundation, 2011; German translation of our research group). Carers get access to one new web‐based module weekly. They are instructed how to work on the program at any time. Within the modules, carers fill in interactive fields of the exercises and report on their experiences and the “experiments” they carried out at home. In addition, carers are invited to use the opportunity to contact the coaches via a personal message system on the website. The coaches offer their support and give weekly feedback to the exercises and the “experiments” of the carers via the personal message system. The carers have the additional possibility to communicate with the other carers and to discuss different topics in an unguided online forum on the website. This online forum is controlled regularly by the coaches and the coaches delete disturbing comments.

2.3.2. Group 3 Control group—Conventional carers' support and TAU

Carers and patients receive TAU at inpatient and outpatient centres with ED units according to the NICE guidelines (NICE, 2017). Therefore, carers take part in conventional carers' support groups or in other treatments for families (e.g., psychotherapy, medical counselling, and psychoeducation). When patients with AN are weighed at specialist services, the results are shared with their family members or carers (if appropriate). Family members or carers (as appropriate) are included in any dietary education or meal planning for the patients. Psychological treatment of the patients includes some family sessions together with their family members and psychoeducation. The therapy emphasises the role of the family in helping the person to recover. Early in treatment, a good therapeutic alliance with the parents or carers and other family members is established and the parents or carers are supported to take a central role in helping the patients manage their eating. In the second phase, parents and carers help to support the patients to establish a level of independence appropriate for their level of development. The families' concerns are addressed and family members are supported in order to cope with distress.

2.4. Outcome measures

To describe the sample, clinical data and demographic information about the patients and their carers are collected at baseline (T0; age, sex, educational level, family situation, migration status, and socio‐economic status). Further assessments for the primary and secondary outcome measures (see Table 2) will take place before starting the intervention (T0), after 3 months (postintervention, T1), and 1 year after the intervention (follow‐up, T2). The semistructured interview of the Eating Disorder Examination (Fairburn & Cooper, 1993; German version: Hilbert & Tuschen‐Caffier, 2006) is conducted face‐to‐face or via telephone by professionals (clinical and health psychologists and psychotherapists). These professionals also administer the other questionnaires, which are answered in a paper–pencil version by the carers and patients themselves. These professionals have already been trained to use these measures before this RCT (by experienced professionals in this field) or received training by G. W. prior to the study. The questionnaires for the process evaluation are answered by the carers of the SUCCEAT intervention after each workshop session or web‐based module and at T1 and T2. Table 2 and Supplement S1 contain further information about the questionnaires.

2.5. Sample size calculations

Power analysis was done with G*Power version 3.1.5. In order to detect a difference for the primary outcome (General Health Questionnaire, see Sepulveda, Lopez, Todd, et al., 2008) by calculating repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA; if the sphericity assumption is not met) at a 5% significance level with 0.88 power, carers of 40 patients per group are needed to detect medium effects (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007). We expect a dropout rate of about 17% (see Wagner et al., 2015). Therefore, we plan to include the carers of 48 patients per treatment arm, resulting in a total sample size of 144.

2.6. Randomisation

After recruitment of the patients and their carers (at the Medical University of Vienna, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and by consultant child and adolescent psychiatrists in adjacent federal states to Vienna), patients and carers who meet the eligibility criteria give their informed consent, perform baseline assessments, and are randomly allocated to one of the two intervention groups (SUCCEAT workshop support group or SUCCEAT web‐based support group) by our research group at the Medical University of Vienna. Random allocation is made in a blockwise manner in order to keep the sizes of treatment groups similar. Incoming patients are numbered consecutively, and randomisation is done blockwise according to the consecutive numbering, in blocks of eight participants in the workshop support group and web‐based support group, respectively. The control group is not randomised.

2.7. Blinding

The clinical and health psychologists and psychotherapists, who conduct the assessments, are not blinded to the treatment arms.

2.8. Statistical analysis plan

The treatment effect will be analysed by using mixed‐design ANOVAs. The time points will be included as within group factor, and the group (workshop support group vs. web‐based support group vs. TAU) will be included as between group factor. t tests for dependent and independent samples will also be used in order to explore differences between specific groups and specific time points.

Two analysis strategies will be applied to account for missing data: Intention‐to‐treat analysis will be used as the primary analysis strategy. If posttreatment or follow‐up data are missing, the last‐value‐put‐forward method will be used. Additionally, the analyses will be repeated by including completers only. Completers will be defined by attending more than 50% of the workshop sessions or web‐based modules. To analyse the potential effect of treatment moderators, additional ANOVAs will be calculated including patient's age and duration of illness as covariates.

3. DISCUSSION

3.1. Limitations

On account of a research gap, some of the questionnaires that we use in this RCT are not validated in the German language yet, and there were no resources to validate them prior to this RCT. We found it important to translate and use these questionnaires because there are no comparable German versions. Although we translated these with back translations, we will validate these questionnaires in the course of this trial and calculate the psychometric properties of the questionnaires.

3.2. Generalisability

This study protocol describes an RCT of the SUCCEAT intervention, an intervention for carers of children and adolescents with AN and atypical AN. Several interventions show improvement for carers of adult patients with an ED (Goddard, Hibbs, et al., 2013; Grover, Naumann, et al., 2011; Hibbs, Magill, et al., 2015; Hibbs, Rhind, Leppanen, et al., 2015; Whitney, Murphy, et al., 2012). Still, little is known about the outcome of carers of children and adolescent patients (in contrast to adults) and also about the outcome of the affected children and adolescents themselves (Hibbs, Rhind, Leppanen, et al., 2015; Hoyle et al., 2013). Both of these issues are addressed in this RCT.

The SUCCEAT intervention has several further strengths in terms of carer's interventions. The feasibility and acceptability measures are included, which is important because we adapted the materials (Schmidt & Treasure, 2006; Treasure, Smith, et al., 2007; Treasure et al., 2010; Treasure & Nazar, 2016; Treasure & Schmidt, 2013) to be used with adolescents, as workshop support groups and web‐based support groups, and to be used in the German language. Above all, the SUCCEAT study will include eight families per SUCCEAT workshop support group and SUCCEAT web‐based support group in order to be even more cost‐effective than a previous study with two families per workshop (Whitney, Murphy, et al., 2012). Moreover, the content of the SUCCEAT groups is more structured than in previous workshop studies (Whitney, Murphy, et al., 2012), which facilitates replicability. Furthermore, we analyse the benefits of the DVD How to Care for Someone with an Eating Disorder (The Succeed Foundation, 2011) for the first time.

In addition, the SUCCEAT intervention concentrates more on MI than cognitive behavioural therapy (Grover, Naumann, et al., 2011), giving parents more time to practise communication skills, as there is evidence that therapy without a focus on weight and shape concerns can also be effective, and MI can be helpful with appealing to the patient (Pike, Walsh, Vitousek, Wilson, & Bauer, 2003; Schmidt & Treasure, 2006; Serfaty, Turkington, Heap, Ledsham, & Jolley, 1999). The content of the SUCCEAT intervention is similar to the self‐help ECHO intervention (Rhind et al., 2014), but the contents are delivered in a therapeutic form (as workshop support groups and web‐based support groups). The carers in the SUCCEAT intervention receive guidance from professional coaches, who are trained in MI and have extensive experience with EDs and other mental illnesses, in contrast to the earlier studies, where carers help other carers (ECHO; Goddard, Raenker, et al., 2013; Magill et al., 2016).

Furthermore, workshop support groups and web‐based support groups based on “The New Maudsley Method” (Treasure, Smith, et al., 2007; Treasure et al., 2010) are compared for the first time. On the one hand, the workshop support groups enable face‐to‐face contact with coaches and other carers. Some people might prefer learning in face‐to‐face settings (Williams, 2003). On the other hand, the SUCCEAT web‐based support groups are low threshold and popular. Web‐based support avoids the intimacy and stigmatization of psychotherapy, increases self‐efficacy, intensifies learning effects, and can be as effective as face‐to‐face support (Wagner et al., 2013; Williams, 2003). Our findings will show how the efficacy and acceptability of the SUCCEAT workshop support groups differ from the SUCCEAT web‐based support groups.

There is online support for patients with other mental disorders that shows positive effects: for parents of children with autism spectrum disorders (Clifford & Minnes, 2013), for parents of socially anxious youth (Reuland & Teachman, 2014), for parents to prevent anxiety problems in young children (Morgan et al., 2015), and for bipolar parents of young children (Jones et al., 2015).

Some of the themes of the SUCCEAT intervention could contribute to future interventions for carers and patients with several disorders, for example, how to deal with perfectionism, to improve emotional intelligence, and to reduce HEE. Results from this investigation will show whether the SUCCEAT intervention may be an effective, acceptable, feasible, affordable, time‐efficient, and transregional form of support for carers in the future.

TRIAL REGISTRATION

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02480907.

FUNDING

The study is funded by “Gemeinsame Gesundheitsziele aus dem Rahmen‐Pharmavertrag/Pharma Master Agreement” (a cooperation between the Austrian pharmaceutical industry and the Austrian social insurance)—Grant 99901002500 given to A. K. and G. W.

Supporting information

Supplement S1 Detailed description of the outcome measures used in the RCT

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our great thanks go to Gill Todd, RMN MSc for training the SUCCEAT coaches and we thank her and Professor Janet Treasure, OBE PhD FRCP FRCPsych for allocating their materials to our research group. We also thank the investigators who are involved in the recruitment of participants at inpatient/outpatient sites: Prim. Univ.‐Prof. Mag. Dr. Thomas Frischer, Dr. Eva Sadek, Dr. Regina Graßl‐Jurek, Wilhelminenspital, Vienna, and Dr. Ellen Auer‐Welsbach, Clinical Centre Klagenfurt, Department of Neurology and Psychiatry for Children and Adolescents. We also thank Daniela Brunner, BSc, Wolfgang Egermann, Elisabeth Jilka, Sarah Pilat, and Nina Weberberger for assisting in the operation of the project, Mag. Natalie Monika Sharp for the back translations of the questionnaires, and Mag. Renate Dosanj for proofreading this text.

Franta C, Philipp J, Waldherr K, et al. Supporting Carers of Children and Adolescents with Eating Disorders in Austria (SUCCEAT): Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Eur Eat Disorders Rev. 2018;26:447–461. 10.1002/erv.2600

Contributor Information

Andreas Karwautz, Email: andreas.karwautz@meduniwien.ac.at.

Gudrun Wagner, Email: gudrun.wagner@meduniwien.ac.at.

REFERENCES

- Anderluh, M. B. , Tchanturia, K. , Rabe‐Hesketh, S. , & Treasure, J. (2003). Childhood obsessive‐compulsive personality traits in adult women with eating disorders: Defining a broader eating disorder phenotype. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(2), 242–247. 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbeitsgruppe Deutsche Child Behavior Checklist . (1998). Fragebogen für Jugendliche; deutsche Bearbeitung der Youth Self‐Report Form der Child Behavior Checklist (YSR) Einführung und Anleitung zur Handauswertung mit deutschen Normen, bearbeitet von Döpfner M., Plück J., Bölte S., Lenz K., Melchers P. & Heim K. (2. Aufl.). Köln: Arbeitsgruppe Kinder‐, Jugend‐ und Familiendiagnostik (KJFD). [Google Scholar]

- Branch, C. , & Eurman, L. J. (1980). Social attitudes toward patients with anorexia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry, 137(5), 631–632. 10.1176/ajp.137.5.631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardi, V. , Di Matteo, R. D. , Corfield, F. , & Treasure, J. (2012). Social reward and rejection sensitivity in eating disorders: An investigation of attentional bias and early experiences. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 14(8), 622–633. 10.3109/15622975.2012.665479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardi, V. , Turton, R. , Schifano, S. , Leppanen, J. , Hirsch, C. R. , & Treasure, J. (2017). Biased interpretation of ambiguous social scenarios in anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review, 25(1), 60–64. 10.1002/erv.2493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney, E. , Goodwin, G. M. , & Fazel, S. (2014). Risks of all‐cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: A meta‐review. World Psychiatry, 13(153–160), 153–160. 10.1002/wps.20128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciao, A. , Accurso, E. C. , Fitzsimmons‐Craft, E. E. , Lock, J. , & Le Grange, D. (2015). Family functioning in two treatments for adolescent anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(1), 81–90. 10.1002/eat.22314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, T. , & Minnes, P. (2013). Logging on: Evaluating an online support group for parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(7), 1662–1675. 10.1007/s10803-012-1714-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane, A. M. , Roberts, M. E. , & Treasure, J. (2007). Are obsessive‐compulsive personality traits associated with a poor outcome in anorexia nervosa? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials and naturalistic outcome studies. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40(7), 581–588. 10.1002/eat.20419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, H. , Schmidt, U. , Stahl, D. , & Tchanturia, K. (2011). Evoked facial emotional expression and emotional experience in people with anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 44(6), 531–539. 10.1002/eat.20852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisler, I. , Simic, M. , Hodsoll, J. , Asen, E. , Berelowitz, M. , Connan, F. , … Landau, S. (2016). A pragmatic randomised multi‐centre trial of multifamily and single family therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa. BMC Psychiatry, 16, 422 10.1186/s12888-016-1129-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, A. (1973). Humanistic psychotherapy: The rational‐emotive approach. New York: Julian Press and McGraw‐Hill Paperbacks. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (2016). Internet access and use statistics—Households and individuals. Retrieved December 15, 2017, from https://deref-gmx.net/mail/client/X_RcMGQKuCk/dereferrer/?redirectUrl=http%3A%2F%2Fec.europa.eu%2Feurostat%2Fstatistics-explained%2Findex.php%2FInternet_access_and_use_statistics_-_households_and_individuals%23Internet_use_by_individuals.

- Fairburn, C. G. , & Cooper, Z. (1993). The Eating Disorder Examination (12th ed.) In Fairburn C. G., & Wilson G. T. (Eds.), Binge eating: Nature, assessment and treatment (pp. 317–360). New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn, C. G. , & Patel, V. (2014). The global dissemination of psychological treatments: A road map for research and practice. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(5), 495–498. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13111546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassino, S. , Svravic, D. , Abbate‐Daga, G. , Leombruni, P. , Amianto, F. , Stanic, S. , & Rovera, G. G. (2002). Anorectic family dynamics: Temperament and character data. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 43(2), 114–120. 10.1053/comp.2002.30806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F. , Erdfelder, E. , Lang, A.‐G. , & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. 10.3758/BF03193146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke, G. H. (2002). SCL‐90‐R ‐ Die Symptom‐Checkliste von L. R. Derogatis (2. vollständig überarbeitete und neu normierte Auflage). Göttingen: Beltz Test. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. (2009). The compassionate mind. London: Constable. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, E. , Hibbs, R. , Raenker, S. , Salerno, L. , Arcelus, J. , Boughton, N. , … Treasure, J. (2013). A multi‐centre cohort study of short term outcomes of hospital treatment for anorexia nervosa in the UK. BMC Psychiatry, 13, 287 10.1186/1471-244X-13-287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, E. , Macdonald, P. , Sepulveda, A. R. , Naumann, U. , Landau, S. , Schmidt, U. , & Treasure, J. (2011). Cognitive interpersonal maintenance model of eating disorders: Intervention for carers. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 199, 225–231. 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.088401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, E. , Macdonald, P. , & Treasure, J. (2011). An examination of the impact of the Maudsley Collaborative Care skills training workshops on patients with anorexia nervosa: A qualitative study. European Eating Disorders Review, 19(2), 150–161. 10.1002/erv.1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, E. , Raenker, S. , Macdonald, P. , Todd, G. , Beecham, J. , Nauman, U. , … Treasure, J. (2013). Carers' assessment, skills and information sharing: Theoretical framework and trial protocol for randomised controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of a complex intervention for carers of inpatients with anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review, 21(1), 60–71. 10.1002/erv.2193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, E. , Salerno, L. , Hibbs, R. , Raenker, S. , Naumann, U. , Arcelus, J. , … Treasure, J. (2013). Empirical examination of the interpersonal maintenance model of anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 46(8), 867–874. 10.1002/eat.22172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodier, G. H. , McCormack, J. , Egan, S. J. , Watson, H. J. , Hoiles, K. J. , Todd, G. , & Treasure, J. L. (2014). Parent skills training treatment for parents of children and adolescents with eating disorders: A qualitative study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(4), 368–375. 10.1002/eat.22224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graap, H. , Bleich, S. , Wilhelm, J. , Herbst, F. , Trostmann, Y. , Wancata, J. , & de Zwaan, M. (2005). Die Belastung und Bedürfnisse Angehöriger anorektischer und bulimischer PatientInnen. Neuropsychiatrie, 19(4), 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Grover, M. , Naumann, U. , Mohammad‐Dar, L. , Glennon, D. , Ringwood, S. , Eisler, I. , … Schmidt, U. (2011). A randomized controlled trial of an Internet‐based cognitive‐behavioural skills package for carers of people with anorexia nervosa. Psychological Medicine, 41, 2581–2591. 10.1017/S0033291711000766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover, M. , Williams, C. , Eisler, I. , Fairbairn, P. , McCloskey, C. , Smith, G. , … Schmidt, U. (2011). An off‐line pilot evaluation of a web‐based systemic cognitive‐behavioral intervention for carers of people with anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 44(8), 708–715. 10.1002/eat.20871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigh, R. , & Treasure, J. (2003). Investigating the needs of carers in the area of eating disorders: Development of the Carers' Needs Assessment Measure (CaNAM). European Eating Disorders Review, 11, 125–141. 10.1002/erv.487 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, A. , Tchanturia, K. , Naumann, U. , & Treasure, J. (2012). Social emotional functioning and cognitive styles in eating disorders. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 51(3), 261–279. 10.1111/j.2044-8260.2011.02026.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasler, G. , Klanghofer, R. , & Buddeberg, C. (2003). Der Fragebogen zur Erfassung der Veränderungsbereitschaft (FEVER). Testung der deutschen Version der University of Rhode Island Change Assessment Scale (URICA). Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, Medizinische Psychologie, 53, 406–411. 10.1055/s-2003-42172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hautzinger, M. , Keller, F. , & Kühner, C. (2006). Das Beck Depressionsinventar II. Deutsche Bearbeitung und Handbuch zum BDI II. Frankfurt a. M.: Harcourt Test Services. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbs, R. , Magill, N. , Goddard, E. , Rhind, C. , Raenker, S. , Macdonald, P. , … Treasure, J. (2015). Clinical effectiveness of a skills training intervention for caregivers in improving patient and caregiver health following in‐patient treatment for severe anorexia nervosa: Pragmatic randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 1(1), 56–66. 10.1192/bjpo.bp.115.000273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbs, R. , Rhind, C. , Leppanen, J. , & Treasure, J. (2015). Interventions for caregivers of someone with an eating disorder: A meta‐analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(4), 349–361. 10.1002/eat.22298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbs, R. , Rhind, C. , Salerno, L. , Lo Coco, G. , Goddard, E. , Schmidt, U. , … Treasure, J. (2015). Development and validation of a scale to measure caregiver skills in eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(3), 290–297. 10.1002/eat.22362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert, A. , & Tuschen‐Caffier, B. (2006). Eating Disorder Examination: Deutschsprachige Übersetzung. Münster: Verlag für Psychotherapie. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, D. , Slater, J. , Williams, C. , Schmidt, U. , & Wade, T. D. (2013). Evaluation of a web‐based skills intervention for carers of people with anorexia nervosa: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 46(6), 634–638. 10.1002/eat.22144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S. , Wainwright, L. D. , Jovanoska, J. , Vincent, H. , Diggle, P. J. , Calam, R. , … Lobban, F. (2015). An exploratory randomised controlled trial of a web‐based integrated bipolar parenting intervention (IBPI) for bipolar parents of young children (aged 3–10). BMC Psychiatry, 15, 122 10.1186/s12888-015-0505-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanakam, N. , Raoult, C. , Collier, D. , & Treasure, J. (2012). Set shifting and central coherence as neurocognitive endophenotypes in eating disorders: A preliminary investigation in twins. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 14(6), 464–475. 10.3109/15622975.2012.665478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronmüller, K. T. , Krummheuer, C. , Topp, F. , Zipfel, S. , Herzog, W. , & Hartmann, M. (2001). Der Fragebogen zur familiären emotionalen Involviertheit und wahrgenommen Kritik (FEIWK). Ein Verfahren zur Erfassung von Expressed Emotion. Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, Medizinische Psychologie, 51, 377–383. 10.1055/s-2001-16897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug, I. , Penelo, E. , Fernandez‐Aranda, F. , Anderluh, M. , Bellodi, L. , Cellini, E. , … Treasure, J. (2012). Low social interactions in eating disorder patients in childhood and adulthood: A multi‐centre European case control study. Journal of Health Psychology, 18(1), 26–37. 10.1177/1359105311435946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou, O. , Treasure, J. , & Schmidt, U. (2008a). Expressed emotion in eating disorders assessed via self‐report: An examination of factors associated with expressed emotion in carers of people with anorexia nervosa in comparison to control families. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 41, 37–46. 10.1002/eat.20469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou, O. , Treasure, J. , & Schmidt, U. (2008b). Understanding how parents cope with living with someone with anorexia nervosa: Modelling the factors that are associated with carer distress. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 41(3), 233–242. 10.1002/eat.20488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laux, L. , Glanzmann, P. , Schaffner, P. , & Spielberger, C. D. (1981). Das State‐Trait‐Angstinventar (Testmappe mit Handanweisung, Fragebogen STAI‐G Form X 1 und Fragebogen STAI‐G Form X 2). Weinheim: Beltz. [Google Scholar]

- Linden, M. , Maier, W. , Achenberger, M. , Herr, R. , Helmchen, H. , & Benkert, O. (1996). Psychische Erkrankungen und Ihre Behandlungen in Allgemeinarztpraxen in Deutschland. Nervenarzt, 67, 205–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, P. , Murray, J. , Goddard, E. , & Treasure, J. (2011). Carer's experience and perceived effects of a skills based training programme for families of people with eating disorders: A qualitative study. European Eating Disorders Review, 19, 475–486. 10.1002/erv.1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, P. , Todd, G. , Whitaker, W. , Creasy, L. , Langley, J. , & Treasure, J. (in prep). Supporting carers of people with eating disorders. Manuscript in preparation.

- Magill, N. , Rhind, C. , Hibbs, R. , Goddard, E. , Macdonald, P. , Arcelus, J. , … Treasure, J. (2016). Two‐year follow‐up of a pragmatic randomised controlled trial examining the effect of adding a carer's skill training intervention in inpatients with anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review, 24, 122–130. 10.1002/erv.2422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight, R. , & Boughton, N. (2009). A patient's journey. Anorexia nervosa. British Medical Journal, 339, b3800 10.1136/bmj.b3800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, W. R. , & Rollnick, S. (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing for change (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, A. J. , Rapee, R. M. , Tamir, E. , Goharpey, N. , Salim, A. , McLellan, L. F. , & Bayer, J. K. (2015). Preventing anxiety problems in children with Cool Little Kids Online: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials, 16, 507 10.1186/s13063-015-1022-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2017). Eating disorders: Recognition and treatment. Retrieved November 29, 2017, from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng69

- Nazar, B. P. , Gregor, L. K. , Albano, G. , Marchica, A. , Coco, G. L. , Cardi, V. , & Treasure, J. (2017). Early response to treatment in eating disorders: A systematic review and a diagnostic test accuracy meta‐analysis. European Eating Disorders Review, 25(2), 67–79. 10.1002/erv.2495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul, T. , & Thiel, A. (2005). EDI‐2. Eating Disorder Inventory‐2. Göttingen: Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, K. M. , Walsh, B. T. , Vitousek, K. , Wilson, G. T. , & Bauer, J. (2003). Cognitive behavior therapy in the posthospitalization treatment of anorexia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(11), 2046–2049. 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.2046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska, J. , & DiClemente, C. (1984). The transtheoretical approach: Crossing the traditional boundaries of therapy. Homewood, IL: Dow Jones‐Irwin. [Google Scholar]

- Ravens‐Sieberer, U. , & Bullinger, M. (1998a). Assessing health related quality of life in chronically ill children with the German KINDL: First psychometric and content‐analytical results. Quality of Life Research, 7, 399–407. 10.1023/A:1008853819715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravens‐Sieberer, U. , & Bullinger, M. (1998b). News from the KINDL‐questionnaire—A new version for adolescents. Quality of Life Research, 7, 653–682. 10.1023/B:QURE.0000004424.99048.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuland, M. M. , & Teachman, B. A. (2014). Interpretation bias modification for youth and their parents: A novel treatment for early adolescent social anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(8), 851–864. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhind, C. , Hibbs, R. , Goddard, E. , Schmidt, U. , Micali, N. , Gowers, S. , … Treasure, J. (2014). Experienced Carers Helping Others (ECHO): protocol for a pilot randomised controlled trial to examine a psycho‐educational intervention for adolescents with anorexia nervosa and their carers. European Eating Disorders Review, 22(4), 267–277. 10.1002/erv.2298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhind, C. , Salerno, L. , Hibbs, R. , Micali, N. , Schmidt, U. , Gowers, S. , … Treasure, J. (2016). The objective and subjective caregiving burden and caregiving behaviours of parents of adolescents with anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review, 24(4), 310–319. 10.1002/erv.2442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieger, E. , Touyz, S. W. , & Beumont, P. J. V. (2002). The Anorexia Nervosa Stages of Change Questionnaire (ANSOCQ): Information regarding its psychometric properties. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 32(1), 24–38. 10.1002/eat.10056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, M. , Tchanturia, K. , Stahl, D. , Southgate, L. , & Treasure, J. (2007). A systematic review and meta‐analysis of set‐shifting ability in eating disorders. Psychological Medicine, 37(8), 1075–1084. 10.1017/S0033291707009877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roick, C. , Kilian, R. , Matschinger, H. , Bernert, S. , Mory, C. , & Angermeyer, M. C. (2001). Die deutsche Version des Client Sociodemographic and Service Receipt Inventory. Ein Instrument zur Erfassung psychiatrischer Versorgungskosten. Psychiatrische Praxis, 28(2), 84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, T. A. , Schmidt, U. , Doherty, L. , Young, V. , & Tchanturia, K. (2009). Aspects of social cognition in anorexia nervosa: Affective and cognitive theory of mind. Psychiatry Research, 168(3), 181–185. 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salerno, L. , Rhind, C. , Hibbs, R. , Micali, N. , Schmidt, U. , Gowers, S. , … Treasure, J. (2016a). An examination of the impact of care giving styles (accommodation and skillful communication and support) on the one year outcome of adolescent anorexia nervosa: Testing the assumptions of the cognitive interpersonal model in anorexia nervosa. Journal of Affective Disorders, 191, 230–236. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salerno, L. , Rhind, C. , Hibbs, R. , Micali, N. , Schmidt, U. , Gowers, S. , … Treasure, J. (2016b). A longitudinal examination of dyadic distress patterns following a skills intervention for carers of adolescents with anorexia nervosa. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(12), 1337–1347. 10.1007/s00787-016-0859-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, U. , & Treasure, J. (2006). Anorexia nervosa: Valued and visible. A cognitive‐interpersonal maintenance model and its implications for research and practice. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 45, 343–366. 10.1348/014466505X53902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz von Thun, F. (1981). Miteinander reden 1: Störungen und Klärungen: Allgemeine Psychologie der Kommunikation. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarte, R. , Timmesfeld, N. , Dempfle, A. , Krei, M. , Egberts, K. , Jaite, C. , … Bühren, K. (2017). Expressed emotions and depressive symptoms in caregivers of adolescents with first‐onset anorexia nervosa—A long‐term investigation over 2.5 years. European Eating Disorders Review, 25, 44–51. 10.1002/erv.2490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda, A. R. , Kyriacou, O. , & Treasure, J. (2009). Development and validation of the Accommodation and Enabling Scale for Eating Disorders (AESED) for caregivers in eating disorders. BMC Health Services Research, 9, 171–183. 10.1186/1472-6963-9-171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda, A. R. , Lopez, C. , Macdonald, P. , & Treasure, J. (2008). Feasibility and acceptability of DVD and telephone coaching‐based skills training for carers of people with an eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 41(4), 318–325. 10.1002/eat.20502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda, A. R. , Lopez, C. , Todd, G. , Whitaker, W. , & Treasure, J. (2008). An examination of the impact of “the Maudsley eating disorder collaborative care skills workshops” on the well being of carers. A pilot study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43, 584–591. 10.1007/s00127-008-0336-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda, A. R. , Todd, G. , Whitaker, W. , Grover, M. , Stahl, D. , & Treasure, J. (2010). Expressed emotion in relatives of patients with eating disorders following skills training program. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 43(7), 603–610. 10.1002/eat.20749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda, A. R. , Whitney, J. , Hankins, M. , & Treasure, J. (2008). Development and validation of an Eating Disorders Symptom Impact Scale (EDSIS) for carers of people with eating disorders. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 6, 28–36. 10.1186/1477-7525-6-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serfaty, M. A. , Turkington, D. , Heap, M. , Ledsham, L. , & Jolley, E. (1999). Cognitive therapy versus dietary counselling in the outpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa: Effects of the treatment phase. European Eating Disorders Review, 7(5), 334–350. 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0968(199911)7:5%3C334::AID-ERV311%3E3.0.CO;2-H [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serpell, L. , Teasdale, J. D. , Troop, N. A. , & Treasure, J. (2004). The development of the P‐CAN, a measure to operationalize the pros and cons of anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 36(4), 416–433. 10.1002/eat.20040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spettigue, W. , Maras, D. , Obeid, N. , Henderson, K. A. , Buchholz, A. , Gomez, R. , & Norris, M. L. (2015). A psycho‐education intervention for parents of adolescents with eating disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Eating Disorders, 23(1), 60–75. 10.1080/10640266.2014.940790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternheim, L. , Startup, H. , Pretorius, N. , Johnson‐Sabine, E. , Schmidt, U. , & Channon, S. (2012). An experimental exploration of social problem solving and its associated processes in anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Research, 200(2–3), 524–529. 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinbourne, J. , Hunt, C. , Abbott, M. , Russell, J. , St Clare, T. , & Touyz, S. (2012). The comorbidity between eating disorders and anxiety disorders: Prevalence in an eating disorder sample and anxiety disorder sample. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 46(2), 118–131. 10.1177/0004867411432071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szmukler, G. I. , Burgess, P. , Herrman, H. , Benson, A. , Colusa, S. , & Bloch, S. (1996). Caring for relatives with serious mental illness: The development of the Experience of Caregiving Inventory. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 31, 137–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taborelli, E. , Easter, A. , Keefe, R. , Schmidt, U. , Treasure, J. , & Micali, N. (2016). Transition to motherhood in women with eating disorders: A qualitative study. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 89(3), 308–323. 10.1111/papt.12076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Succeed Foundation . (2011). How to Care for Someone with an Eating Disorder [DVD].

- Treasure, J. (2016a). Applying evidence‐based management to anorexia nervosa. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 92, 525–531. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treasure, J. (2016b). 3.2 Developmental perspectives of eating disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(10), 88–88. 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.07.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Treasure, J. , & Cardi, V. (2017). Anorexia nervosa, theory and treatment: Where are we 35 years on from Hilde Bruch's foundation lecture? European Eating Disorders Review, 25(3), 139–147. 10.1002/erv.2511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treasure, J. , Murphy, T. , Todd, G. , Gavan, K. , Schmidt, U. , Joyce, J. , & Szmukler, G. (2001). The experience of caregiving for severe mental illness: A comparison between anorexia nervosa and psychosis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 36, 343–347. 10.1007/s001270170039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treasure, J. , & Nazar, B. P. (2016). Interventions for the carers of patients with eating disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18, 16 10.1007/s11920-015-0652-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treasure, J. , & Russell, G. (2011). The case for early intervention in anorexia nervosa: Theoretical exploration of maintaining factors. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(1), 5–7. 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.087585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treasure, J. , & Schmidt, U. (2013). The cognitive‐interpersonal maintenance model of anorexia nervosa revisited: A summary of the evidence for cognitive, socio‐emotional and interpersonal predisposing and perpetuating factors. Journal of Eating Disorders, 1, 13 10.1186/2050-2974-1-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treasure, J. , Schmidt, U. , & Macdonald, P. (2010). The clinicians's guide to collaborative caring in eating disorders—The New Maudsley Method. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Treasure, J. , Sepulveda, A. R. , Macdonald, P. , Whitaker, W. , Lopez, C. , Zabala, M. , … Todd, G. (2008). The assessment of the family of people with eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 16, 247–255. 10.1002/erv.859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treasure, J. , Sepulveda, A. R. , Whitaker, W. , Todd, G. , Lopez, C. , & Whitney, J. (2007). Collaborative care between professionals and non‐professionals in the management of eating disorders: A description of workshops focussed on interpersonal maintaining factors. European Eating Disorders Review, 15, 24–34. 10.1002/erv.758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treasure, J. , Smith, G. , & Crane, A. (2007). Skills‐based learning for caring for a loved one with an eating disorder—The New Maudsley Method. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Treasure, J. , Smith, G. , Crane, A. , Philipp, J. , Wagner, G. , & Karwautz, A. (in prep.). Fertigkeiten zur Unterstützung von Menschen mit Essstörungen – Die neue Maudsley Methode. Wien: Facultas.

- Treasure, J. , Whitaker, W. , Todd, G. , & Whitney, J. (2012). A description of multiple family workshops for carers of people with anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review, 20, e17–e22. 10.1002/erv.1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, G. , Penelo, E. , Nobis, G. , Mayrhofer, A. , Wanner, C. , Schau, J. , … Karwautz, A. (2015). Predictors for good therapeutic outcome and drop‐out in technology assisted guided self‐help in the treatment of bulimia nervosa and bulimia like phenotype. European Eating Disorders Review, 23, 163–169. 10.1002/erv.2336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, G. , Penelo, E. , Wanner, C. , Gwinner, P. , Trofaier, M.‐L. , Imgart, H. , … Karwautz, A. (2013). Internet‐delivered cognitive–behavioural therapy v. conventional guided self‐help for bulimia nervosa: Long‐term evaluation of a randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 202(2), 135–141. 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.098582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward, A. , Ramsay, R. , Turnbull, S. , Steele, M. , Steele, H. , & Treasure, J. (2001). Attachment in anorexia nervosa: A transgenerational perspective. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 74(4), 497–505. 10.1348/000711201161145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney, J. , Currin, L. , Murray, J. , & Treasure, J. (2012). Family work in anorexia nervosa: A qualitative study of carers' experiences of two methods of family intervention. European Eating Disorders Review, 20, 132–141. 10.1002/erv.1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney, J. , Haigh, R. , Weinman, J. , & Treasure, J. (2007). Caring for people with eating disorders: Factors associated with psychological distress and negative caregiving appraisal in carers of people with eating disorders. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 46, 413–428. 10.1348/014466507X173781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney, J. , Murphy, T. , Landau, S. , Gavan, K. , Todd, G. , Whitaker, W. , & Treasure, J. (2012). A practical comparison of two types of family intervention: An exploratory RCT of family day workshops and individual family work as a supplement to inpatient care for adults with anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review, 20, 142–150. 10.1002/erv.1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney, J. , Murray, J. , Gavan, K. , Todd, G. , Whitaker, W. , & Treasure, J. (2005). Experience of caring for someone with anorexia nervosa: Qualitative study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 187, 444–449. 10.1192/bjp.187.5.444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (1990). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (10th revision). Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Wiedemann, G. , Rayki, O. , Feinstein, E. , & Hahlweg, K. (2002). The Family Questionnaire: Development and validation of a new self‐report scale for assessing expressed emotion. Psychiatry Research, 109, 265–279. 10.1016/S0165-1781(02)00023-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C. (2003). New technologies in self‐help: Another effective way to get better? European Eating Disorders Review, 11(3), 170–182. 10.1002/erv.524 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zabala, M. J. , Macdonald, P. , & Treasure, J. (2009). Appraisal of caregiving burden, expressed emotion and psychological distress in families of people with eating disorders: A systematic review. European Eating Disorders Review, 17(4), 338–349. 10.1002/erv.925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zitarosa, D. , de Zwaan, M. , Pfeffer, M. , & Graap, H. (2012). Angehörigenarbeit bei essgestörten Patientinnen. Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, Medizinische Psychotherapie, 62, 390–399. 10.1055/s-0032-1316335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplement S1 Detailed description of the outcome measures used in the RCT