Abstract

Background

Effective inhibition of plasma kallikrein may have significant benefits for patients with hereditary angioedema due to deficiency of C1 inhibitor (C1‐INH‐HAE) by reducing the frequency of angioedema attacks. Avoralstat is a small molecule inhibitor of plasma kallikrein. This study (OPuS‐2) evaluated the efficacy and safety of prophylactic avoralstat 300 or 500 mg compared with placebo.

Methods

OPuS‐2 was a Phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel‐group study. Subjects were administered avoralstat 300 mg, avoralstat 500 mg, or placebo orally 3 times per day for 12 weeks. The primary efficacy endpoint was the angioedema attack rate based on adjudicator‐confirmed attacks.

Results

A total of 110 subjects were randomized and dosed. The least squares (LS) mean attack rates per week were 0.589, 0.675, and 0.593 for subjects receiving avoralstat 500 mg, avoralstat 300 mg, and placebo, respectively. Overall, 1 subject in each of the avoralstat groups and no subjects in the placebo group were attack‐free during the 84‐day treatment period. The LS mean duration of all confirmed attacks was 25.4, 29.4, and 31.4 hours for the avoralstat 500 mg, avoralstat 300 mg, and placebo groups, respectively. Using the Angioedema Quality of Life Questionnaire (AE‐QoL), improved QoL was observed for the avoralstat 500 mg group compared with placebo. Avoralstat was generally safe and well tolerated.

Conclusions

Although this study did not demonstrate efficacy of avoralstat in preventing angioedema attacks in C1‐INH‐HAE, it provided evidence of shortened angioedema episodes and improved QoL in the avoralstat 500 mg treatment group compared with placebo.

Keywords: C1 inhibitor, hereditary angioedema, oral kallikrein inhibitor, prophylaxis

1. BACKGROUND

Hereditary angioedema (HAE) with C1 inhibitor deficiency (C1‐INH‐HAE) is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of swelling of the skin, pharynx, larynx, gastrointestinal tract, genitals, and extremities,1 and is due primarily to mutations in the SERPING1 gene that results in insufficient production of the natural plasma kallikrein inhibitor, C1 inhibitor (C1‐INH). C1‐INH is a serine protease inhibitor (serpin) that prevents uncontrolled contact activation and bradykinin (BK) production by covalently binding to and inactivating kallikrein, a serine protease integral to the contact activation pathway.2 Extensive evidence from animal models and clinical studies supports the role of BK as the principal mediator of the signs and symptoms of C1‐INH‐HAE.3, 4, 5 Activation of the BK B2 receptor by BK results in vasodilatation, increased vascular permeability, and smooth muscle contraction, all of which contribute to the angioedema attacks in C1‐INH‐HAE patients.3 Oropharyngeal and laryngeal swelling can be life‐threatening. Angioedema attacks in other sites, including the limbs, genitalia, face, and intestines, can be painful, disabling, and disfiguring, and have a significant impact on functionality and quality of life of the patients.6, 7, 8, 9

The effective management of C1‐INH‐HAE involves the prevention and treatment of angioedema attacks.10 Kallikrein is a proven target in the treatment of C1‐INH‐HAE. In the EU and the United States, licensed therapy for long‐term or routine prevention of angioedema attacks is limited to purified plasma‐derived C1‐INH administered intravenously (Cinryze®) or subcutaneously (Haegarda® – USA only) every 3‐4 days; oral doses of attenuated androgens (such as danazol) are also prescribed for C1‐INH‐HAE attack prophylaxis. While administration of androgens is convenient, unacceptable adverse effects (such as androgenic hormonal effects, intracranial hypertension, and hepatocellular adenoma and carcinoma) and contraindications (including pregnancy and pediatrics) limit their clinical use.10, 11

Avoralstat (formerly BCX4161) is a potent, small molecule inhibitor of kallikrein that was discovered at BioCryst Pharmaceuticals, Inc.12 Effective inhibition of kallikrein with an orally bioavailable small molecule such as avoralstat may have significant benefits for patients with C1‐INH‐HAE by reducing the frequency of angioedema attacks. In a prior Phase 2 study, the safety and efficacy of avoralstat 400 mg taken 3 times per day were evaluated as a prophylactic treatment to reduce the frequency of angioedema attacks in subjects with C1‐INH‐HAE.13 Treatment with avoralstat resulted in significantly fewer angioedema attacks per week, demonstrating proof of concept for avoralstat in the prevention of angioedema attacks in subjects with C1‐INH‐HAE. In the Phase 2 study, treatment with avoralstat also showed statistically significant improvements in subject quality of life (QoL), severity of disease, and number of attack‐free days. Avoralstat was generally well tolerated with no discontinuations due to drug‐related adverse events (AEs), no Grade 4 AEs or treatment‐related serious adverse events (SAEs), and few Grade 3 AEs or laboratory abnormalities.

This OPuS‐2 Phase 3 study evaluated the efficacy and safety of prophylactic avoralstat 300 and 500 mg administered 3 times per day for 12 weeks compared with placebo, assessed the effects of avoralstat on C1‐INH‐HAE disease activity and angioedema attack characteristics. This study also evaluated the effects of avoralstat on patients’ QoL and described the population pharmacokinetics (PK) of avoralstat.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

OPuS‐2 was a Phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel‐group study performed at 46 centers in North America and Europe. Eligible subjects, stratified by screening angioedema attack rates (≥1 attack per week vs <1 attack per week), were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive avoralstat 500 mg, avoralstat 300 mg, or placebo administered orally 3 times per day for 12 weeks. Details of HAE attacks were recorded in an electronic diary. Attacks were treated in accordance with the subject's normal standard of care.

The OPuS‐2 trial (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov ID# NCT02303626 and EudraCT # 2014‐002655‐26) was approved by independent ethics committees or institutional review boards. All patients provided written informed consent.

2.2. Subjects

Subjects aged ≥18 years of age with a clinical diagnosis of type 1 or 2 C1‐INH‐HAE as documented by either a low C1 INH antigenic level (Type I HAE) or a normal C1‐INH antigenic level and a low C1 INH functional level (Type II HAE) were eligible. Documentation of minimum angioedema attack rate of 2 per month was required, either by audit of medical record (at least 2 angioedema attacks per month for 3 consecutive months within the 6 months prior to screening) or a subject diary record of at least 4 unique angioedema attacks collected in a run‐in period of a maximum of 2 months, with at least 1 attack occurring each month. Use of C1INH or tranexamic acid within 7 days prior to the screening visit or expected use at any time during the study was exclusionary. The use of androgens within 30 days was also an exclusion criterion unless the subject was receiving a stable dose of androgens at least 90 days prior to the screening visit, met the required angioedema attack frequency while on the stable dose, and planned to remain on the current dose of androgens during the study.

2.3. Study treatment

Subjects received avoralstat 500 mg, avoralstat 300 mg, or placebo administered orally 3 times per day for 12 weeks, and were asked to avoid taking study drug with food. Study drug assignment was blinded to the investigator and clinical site personnel, study subjects, and study staff.

2.4. Study measures

The primary efficacy outcome was weekly angioedema attack rate based on the number of confirmed episodes. Secondary efficacy endpoints included the weekly subject‐reported attack rate, number of attack‐free days, the AE‐QoL score, and the average attack severity score. Efficacy data collected included the number of angioedema attacks and related details (timing, severity, duration of symptoms, anatomical location, treatment used [if any]), number of attack‐free days, Angioedema Quality of Life (AE‐QoL) Questionnaire,14, 15 and angioedema activity score (AAS,16). An angioedema attack was defined as subject‐reported indication of swelling at any location following a report of no swelling on the previous day. Abdominal attacks were defined by abdominal pain with or without nausea or vomiting; laryngeal attacks were defined by difficulty swallowing or breathing, voice change, or lump or tightness in the throat. Peripheral attacks were defined by cutaneous swelling. Prior to inclusion in efficacy analyses, each subject‐reported angioedema attack was reviewed by the investigator, and all attacks were reviewed and confirmed or rejected by an expert adjudication panel blinded to treatment arm.

Plasma samples for determination of avoralstat concentrations were collected at baseline (Day 1) and predose (trough) at the Week 4, 8, and 12 visits for all subjects. Subjects who consented to participate in a PK substudy had additional plasma samples drawn through 6 hours following the first dose on Day 1 and for one morning dose at or between the Week 4 and Week 8 visits.

Safety was assessed by monitoring of adverse events (AEs) and through clinical laboratory assessments, vital signs, electrocardiograms (ECGs), abdominal ultrasonography, and physical examinations. An independent data monitoring committee periodically reviewed safety data.

2.5. Populations for analysis

The intent‐to‐treat (ITT) and safety populations included all subjects who were randomized and received at least 1 dose of study drug.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The primary efficacy endpoint was the angioedema attack rate based on confirmed attacks. The study was designed to investigate the superiority of avoralstat over placebo. Assuming a normalized placebo attack rate of 1 unit and standard deviations of 0.45 and 0.40 units for avoralstat and placebo attack rates, respectively, a sample size of 32 subjects was anticipated to have 90% power to detect a treatment difference of 0.35 units per time period between avoralstat and placebo, based on a 2‐sided test at a significance level of 0.05.

An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model, including treatment group as a fixed term and angioedema attack stratum (≥1 or <1 attack per week) as a covariate, was used for the primary analysis, which reported the estimated treatment difference in attack rate (for each avoralstat dose minus placebo) with its associated 95% CI and P‐value.

Secondary efficacy endpoints included the number of attack‐free days, the AE‐QoL score, the number of subject‐reported attacks, and the average attack severity score. Attack‐free days were analyzed in a similar manner as the primary efficacy endpoint. Changes from baseline in AE‐QoL data were summarized by the four AE‐QoL domain scores and a total score using the appropriate scoring algorithm. Average attack severity score was summarized.

Avoralstat plasma PK parameters were estimated using noncompartmental analysis (Phoenix WinNonlin, version 6.4 or later).

Safety data were summarized descriptively.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Baseline characteristics

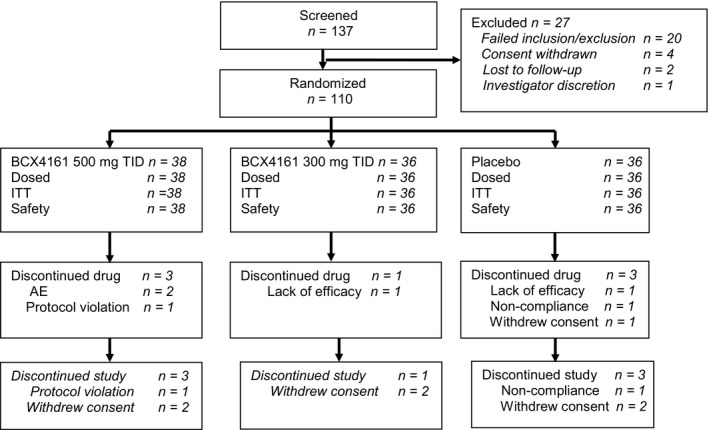

The study was conducted from December 2014 to January 2016. Of the 137 subjects screened, 110 subjects were randomized and dosed (Figure 1). Of the 110 subjects randomized, 103 subjects (93.6%) completed study drug and 7 subjects (6.4%) discontinued study drug prior to Week 12. Reasons for study drug discontinuation included AEs (1 subject due to rash and 1 subject due to angioedema attack in the avoralstat 500 mg group), lack of efficacy (1 subject each in the avoralstat 300 mg group and the placebo group), a positive pregnancy test (1 subject in the placebo group), protocol violation (1 subject in the avoralstat 500 mg group), and study noncompliance (1 subject in the placebo group).

Figure 1.

Consort diagram. AE, adverse event; ITT, intent to treat; TID, 3 times per day

The majority of subjects were female (77.3%) and Caucasian (92.7%), the mean age was 41.2 years, and the mean BMI was 26.8 kg/m2 (Table 1). A small number of subjects (9.1%) continued with concurrent androgen prophylaxis on study. The mean (SD) weekly qualifying attack rate was 0.93 (0.37). Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were generally similar across the treatment groups.

Table 1.

Demographics and select baseline disease characteristics (ITT population)

| Avoralstat 500 mg TID (N = 38) | Avoralstat 300 mg TID (N = 36) | Placebo (N = 36) | Total (N = 110) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 41.1 (15.1) | 40.4 (12.4) | 42.1 (12.5) | 41.2 (13.3) |

| Sex (female), n (%) | 30 (78.9) | 29 (80.6) | 26 (72.2) | 85 (77.3) |

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 26.7 (4.5) | 28.1 (5.4) | 25.6 (3.9) | 26.8 (4.7) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 | 1 (2.8) | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Asian | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.8) | 0 | 2 (1.8) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0 | 1 (2.8) | 1 (2.8) | 2 (1.8) |

| White | 36 (94.7) | 32 (88.9) | 34 (94.4) | 102 (92.7) |

| Other | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.8) | 1 (2.8) | 3 (2.7) |

| Hereditary angioedema type, n (%) | ||||

| Type I | 34 (89.5) | 32 (88.9) | 35 (97.2) | 101 (91.8) |

| Type II | 4 (10.5) | 4 (11.1) | 1 (2.8) | 9 (8.2) |

| Age at diagnosis of C1‐INH‐HAE (years), mean (SD) | 17.8 (10.6) | 19.4 (12.1) | 22.8 (12.1) | 20.0 (11.7) |

| Qualifying attack rate (attack/week)a, mean (SD) | 0.95 (0.39) | 0.93 (0.39) | 0.92 (0.34) | 0.93 (0.37) |

| <1 attack per week, n (%) | 26 (68.4) | 26 (72.2) | 22 (61.1) | 74 (67.3) |

| ≥1 attack per week, n (%) | 12 (31.6) | 10 (27.8) | 14 (38.9) | 36 (32.7) |

| Concurrent androgen use, n (%) | 2 (5.3) | 4 (11.1) | 4 (11.1) | 10 (9.1) |

BMI, body mass index; C1‐INH‐HAE, hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency; ITT, intent to treat; SD, standard deviation; TID, 3 times per day.

Qualifying HAE attack rate was derived based on subject‐reported historical attacks or attacks during the run‐in period when historical attack data were not available.

3.2. Primary efficacy measure

The least squares (LS) mean attack rates per week of confirmed attacks were 0.59, 0.68, and 0.59 for subjects during treatment with avoralstat 500 mg, avoralstat 300 mg, and placebo groups, respectively (P ≥ .5, Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of primary and secondary efficacy endpoints (ITT population)

| Avoralstat 500 mg TID (N = 38) | Avoralstat 300 mg TID (N = 36) | Placebo (N = 36) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weekly rate of confirmed attacks | |||

| LS mean | 0.59 | 0.68 | 0.59 |

| Differencea (95% CI) | −0.00 (−0.25, 0.24) | 0.08 (−0.17, 0.33) | |

| Treatment effect P‐value | .98 | .51 | |

| Weekly rate of subject‐reported attacks | |||

| LS mean | 0.62 | 0.73 | 0.65 |

| Differencea (95% CI) | −0.03 (0.29,0.23) | 0.08 (−0.18, 0.35) | |

| Treatment effect P‐value | .80 | .53 | |

| Weekly rate of confirmed attacks requiring treatment | |||

| LS mean | 0.49 | 0.58 | 0.50 |

| Differencea (95% CI) | −0.02 (−0.27, 0.23) | −0.07 (−0.18, 0.32) | |

| Attack duration hours | |||

| LS mean | 25.4 | 29.4 | 31.4 |

| Differencea (95% CI) | −6.0 | −2.0 | |

| Treatment effect P‐value | .01 | .40 | |

| Number of attack‐free days | |||

| LS mean | 67.2 | 64.1 | 64.2 |

| Differencea (95% CI) | 3.0 (−4.5, 10.4) | −0.1 (−7.7, 7.5) | |

| Treatment effect P‐value | .43 | .98 | |

| Attack‐free subjects | |||

| n (%) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.8) | 0 |

| AAS84 | |||

| LS mean | 83.94 | 109.08 | 94.84 |

| Differencea (95% CI) | −10.90 | 14.24 | |

| Treatment effect P‐value | .59 | .49 | |

AAS, angioedema activity score; AE‐QoL, angioedema quality of life; CI, confidence interval; ITT, intent to treat; LS, least squares; TID, 3 times per day.

Avoralstat – placebo.

3.3. Secondary efficacy measures

The LS mean attack rates per week of all subject‐reported attacks were 0.62, 0.73, and 0.65 for subjects in the avoralstat 500 mg, avoralstat 300 mg, and placebo groups, respectively (P ≥ .5, Table 2). The LS mean attack rates per week of confirmed attacks requiring treatment were 0.49, 0.58, and 0.50 for subjects in the avoralstat 500 mg, avoralstat 300 mg, and placebo groups, respectively (Table 2). The most commonly used medications to treat attacks were icatibant and plasma‐derived C1‐INH concentrate.

Both the number and percent of attack‐free days were similar between active and placebo treatment groups, with approximately 80% of the total days on study treatment attack‐free. Overall, 1 subject in each of the avoralstat groups and no subjects in the placebo group were attack‐free during the 84‐day treatment period. The LS mean duration of all confirmed attacks was 25.4, 29.4, and 31.4 hours for subjects in the avoralstat 500 mg (P = .01), avoralstat 300 mg (P = .40), and placebo groups, respectively.

The LS mean reduction from baseline (improvement) in total AE‐QoL scores in the avoralstat 500 mg group was significantly greater than in the placebo group at Week 4 (−7.23 points, P = .03) and Week 8 (−8.83 points, P = .01), but not at Week 12 (−5.31 points, P = .16) (Table 3). Greater reductions were observed for the avoralstat 500 mg group compared with placebo for each of the individual domain scores with significant differences observed at specific time points: Weeks 4 and 8 for functioning, Week 8 for fear/shame, and Week 12 for fatigue/mood. No significant differences were observed between the avoralstat 300 mg group and placebo at any time point.

Table 3.

Summary of the LS mean change from baseline in the total AE‐QoL score (ITT population)

| Treatment | N | LS mean | Standard error | Difference vs placeboa | 95% CI for treatment difference | P‐value for treatment difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 4 | ||||||

| Avoralstat 500 mg | 38 | −16.63 | 2.37 | −7.23 | −13.6, −0.8 | .03 |

| Avoralstat 300 mg | 35 | −5.06 | 2.47 | 4.34 | −2.2, 10.9 | .19 |

| Placebo | 33 | −9.41 | 2.14 | — | — | — |

| Week 8 | ||||||

| Avoralstat 500 mg | 37 | −18.55 | 2.66 | −8.83 | −15.6, −2.1 | .01 |

| Avoralstat 300 mg | 34 | −10.96 | 3.02 | −1.23 | −8.6, 6.1 | .74 |

| Placebo | 33 | −9.72 | 2.08 | — | — | — |

| Week 12 | ||||||

| Avoralstat 500 mg | 36 | −17.45 | 2.66 | −5.31 | −12.8, 2.2 | .16 |

| Avoralstat 300 mg | 33 | −9.89 | 3.11 | 2.25 | −5.9, 10.4 | .59 |

| Placebo | 33 | −12.14 | 2.64 | — | — | — |

AE‐QoL, angioedema quality of life; CI, confidence interval; ITT, intent to treat; LS, least squares.

A reduction in total score represents an improvement in QoL.

Angioedema activity score scores were not significantly different comparing either 500 mg or 300 avoralstat groups with placebo.

3.4. Pharmacokinetics

Following multiple oral dose administration, maximal avoralstat concentrations were achieved approximately 1 hour postdose. Plasma concentrations are shown in Figure 2. A large variability in plasma concentrations was observed at both doses, with many time points below the target therapeutic concentration of 4‐8 times the EC50 of avoralstat for plasma kallikrein.

Figure 2.

Avoralstat plasma concentrations. The blue bar represents a target therapeutic concentration in the range of 4‐8 times the EC 50 of avoralstat for plasma kallikrein in a plasma‐based assay17

3.5. Safety

Avoralstat was generally safe and well tolerated, with only 2 discontinuations due to unrelated AEs (an angioedema attack, considered serious, and a mild rash; both in the avoralstat 500 mg group), and no life‐threatening AEs or treatment‐related SAEs were reported. No deaths were reported. Most AEs were mild or moderate in severity. Grade 3 AEs considered related to study drug were flatulence, diarrhea, and abdominal distension in the avoralstat 300 mg group and flatulence and headache in the placebo group. No Grade 3 AEs considered related to study drug were reported in the 500 mg group. No treatment‐emergent Grade 4 AEs were reported.

The most commonly reported AEs (Table 4) in the combined avoralstat groups and placebo, respectively, were diarrhea (32.4%, 33.3%), flatulence (20.3%, 25.0%), and nasopharyngitis (17.6%, 19.4%). The nature and frequency of the AEs were generally similar between the avoralstat treatment groups and the placebo group.

Table 4.

Adverse events occurring in ≥5% of subjects in any treatment group (safety population)

| Avoralstat 500 mg TID (N = 38) | Avoralstat 300 mg TID (N = 36) | Placebo (N = 36) | Avoralstat total (N = 74) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) of subjects with at least 1 treatment‐emergent AE, n (%) | ||||

| Diarrhea | 16 (42.1) | 8 (22.2) | 12 (33.3) | 24 (32.4) |

| Flatulence | 10 (26.3) | 5 (13.9) | 9 (25.0) | 15 (20.3) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 8 (21.1) | 5 (13.9) | 7 (19.4) | 13 (17.6) |

| Headaches | 7 (18.4) | 4 (11.1) | 6 (16.7) | 11 (14.9) |

| Nausea | 3 (7.9) | 4 (11.1) | 3 (8.3) | 7 (9.5) |

| Abdominal distension | 2 (5.3) | 3 (8.3) | 2 (5.6) | 5 (6.8) |

| Abdominal pain | 4 (10.5) | 0 | 2 (5.6) | 4 (5.4) |

| Urinary tract infection | 2 (5.3) | 2 (5.6) | 1 (2.8) | 4 (5.4) |

| Abdominal pain upper | 0 | 3 (8.3) | 0 | 3 (4.1) |

| Blood alkaline phosphatase increased | 0 | 3 (8.3) | 0 | 3 (4.1) |

| Blood in urine present | 0 | 3 (8.3) | 0 | 3 (4.1) |

| Cystitis | 2 (5.3) | 1 (2.8) | 0 | 3 (4.1) |

| GGT increased | 0 | 3 (8.3) | 0 | 3 (4.1) |

| Hereditary angioedema | 1 (2.6) | 2 (5.6) | 1 (2.8) | 3 (4.1) |

| Myalgia | 1 (2.6) | 2 (5.6) | 0 | 3 (4.1) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 2 (5.3) | 1 (2.8) | 1 (2.8) | 3 (4.1) |

| Viral infection | 2 (5.3) | 1 (2.8) | 0 | 3 (4.1) |

| Acne | 2 (5.3) | 0 | 1 (2.8) | 2 (2.7) |

| Arthralgia | 0 | 2 (5.6) | 1 (2.8) | 2 (2.7) |

| Back pain | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.8) | 2 (5.6) | 2 (2.7) |

| Contusion | 2 (5.3) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.7) |

| Dizziness | 0 | 2 (5.6) | 0 | 2 (2.7) |

| Dyspepsia | 2 (5.3) | 0 | 1 (2.8) | 2 (2.7) |

| Feces soft | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.8) | 3 (8.3) | 2 (2.7) |

| Frequent bowel movements | 0 | 2 (5.6) | 0 | 2 (2.7) |

| Gastroenteritis | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.8) | 2 (5.6) | 2 (2.7) |

| Influenza | 2 (5.3) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.7) |

| Oropharyngeal pain | 0 | 2 (5.6) | 0 | 2 (2.7) |

| Sinusitis | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.8) | 3 (8.3) | 2 (2.7) |

| Tonsillitis | 2 (5.3) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.7) |

| Vulvovaginal candidiasis | 2 (5.3) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.7) |

| Oral herpes | 0 | 1 (2.8) | 2 (5.6) | 1 (1.4) |

| Ovarian cyst | 1 (2.6) | 0 | 2 (5.6) | 1 (1.4) |

| Somnolence | 1 (2.6) | 0 | 2 (5.6) | 1 (1.4) |

TID, 3 times per day.

Adverse events were coded using Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 16.0. Treatment‐emergent adverse events included events that started on and after the date of the first dose up to the last dose plus 30 d.

Grade 3 or 4 chemistry abnormalities generally occurred in a similar proportion of subjects in the avoralstat and placebo groups. No subject experienced a Grade 3 or 4 hematology or coagulation laboratory abnormality. No notable changes in vital signs (systolic and diastolic blood pressure and pulse) were reported during the study.

4. DISCUSSION

This study failed to confirm the benefit of avoralstat in reducing angioedema attack rates seen in the OPuS‐1 Phase 2 study. With the exception of quality of life, no differences were observed in the prespecified secondary endpoints of the study, although the LS mean attack duration for the avoralstat 500 mg group was significantly less than placebo.

The failure of this Phase 3 study was surprising, given the clear treatment effect demonstrated in the earlier Phase 2 study, OPuS‐1. A number of factors associated with the PK of avoralstat may explain the poor outcome observed in this study.

Overall, reported study drug compliance was high with a median compliance rate of approximately 99% across all treatment groups. However, trough PK data indicate a wide spread in the time since last recorded dose of study drug, indicating that adherence to an 8‐hourly dosing regimen and taking study drug on an empty stomach, which were required due to the short plasma half‐life of the drug and known food effect on exposure, respectively, was a challenge for study subjects. Intervals between the 3 daily doses were not evenly spaced, with the largest mean interval of approximately 11 hours. Thus, while reported dosing compliance was 99%, dosing frequency (three times daily) and food effect likely impacted efficacy outcomes by contributing to variability in drug exposure.

Plasma concentrations of avoralstat were widely distributed, with many time points showing drug levels below the target therapeutic range of 4‐8 times the EC50 of avoralstat for plasma kallikrein. This variability in exposure was likely due to a combination of the low oral bioavailability of the drug and its relatively rapid clearance,17 coupled with variation in dosing interval and food effects.

Although there were no significant reductions in angioedema attack rate with avoralstat compared with placebo, there was some evidence suggesting that treatment with avoralstat 500 mg improved quality of life. The AE‐QoL scores in the avoralstat 500‐mg group showed a significant reduction (improvement) compared to placebo at Weeks 4 and 8; however, the difference was not significant at Week 12. QoL measures are increasingly being incorporated into HAE treatment trials as clinically meaningful endpoints. While clearly insufficient to prove efficacy in this study, the difference in QoL scores between the avoralstat 500 mg group and placebo treatment groups is intriguing as a potential indirect marker of pharmacodynamic effect.

Overall, treatment with avoralstat 500 or 300 mg 3 times daily for 12 weeks was generally safe and well tolerated with no treatment‐related SAEs. Gastrointestinal side effects were most common, but did not lead to treatment discontinuation. Gastrointestinal events common to all groups were most likely due to excipients as the rates of these events were similar in drug‐treated and placebo groups.

In summary, this rigorous randomized controlled trial of avoralstat did not demonstrate efficacy in preventing angioedema attacks in C1‐INH‐HAE patients. However, the study provided evidence of shortened angioedema episodes and improved QoL measures in the avoralstat 500 mg treatment group compared to placebo, and established safety of oral kallikrein inhibition in this study cohort.

In the future, additional compounds of this drug class with improved pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles may be of substantial therapeutic benefit in C1‐INH‐HAE. Ongoing studies are investigating an oral once‐daily kallikrein inhibitor with improved bioavailability and a longer half‐life.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

This study was sponsored by BioCryst Pharmaceuticals, Inc (BioCryst), Durham, NC. Dr. Riedl reports grants from BioCryst during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from BioCryst, CSL Behring, Shire, and Pharming; and personal fees from Adverum, Alnylam, Ionis, and Kalvista outside the submitted work. Dr. Aygören‐Pürsün reports grants from BioCryst during the conduct of the study; personal fees and nonfinancial support from BioCryst; grants, personal fees, and nonfinancial support from CSL Behring; grants, personal fees, and nonfinancial support from Shire; and personal fees from Pharming and Adverum outside the submitted work. Dr Baker reports grants from BioCryst during the course of the study. Dr. Farkas reports personal fees from BioCryst during the conduct of the study, and personal fees from CSL Behring, Pharming, and Shire outside the submitted work. Dr. Anderson reports other from BioCryst during the conduct of the study, and personal fees from Shire, CSL Behring, and Pharming outside the submitted work. Dr. Bernstein reports grants and personal fees from BioCryst, Shire, CSL Behring, and Pharming during the conduct of the study. Dr. Bouillet reports personal fees and nonfinancial support from Shire; grants, personal fees, and nonfinancial support from Behring; personal fees and nonfinancial support from Pharming; grants, personal fees, and nonfinancial support from Novartis; nonfinancial support from GSK, nonfinancial support from Pfizer, and grants and nonfinancial support from LFB outside the submitted work. Dr, Busse received personal fees from CSL Behring; grants, personal fees, and other from Shire; personal fees and other from Pharming; personal fees from Pearl Therapeutics; personal fees from Teva; other from Law Offices of Victoria Broussard; and personal fees from Global Life Sciences outside the submitted work. Dr. Manning reports grants from BioCryst during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from Shire and CSL Behring, and Dyax; and personal fees from Pharming outside the submitted work. Dr. Magerl reports personal fees and nonfinancial support from Shire, Viropharma, CSL Behring, and BioCryst, and personal fees from Sobi outside the submitted work. Dr. Gompels reports other from Allergy Therapeutics; other from Bristol Myers; personal fees from Advisory board for BioCryst; and other from Viiv, Gilead, BMS, and Janssen outside the submitted work. Dr. Huissoon reports nonfinancial support from CSL limited and Shire Limited outside the submitted work. Dr. Longhurst reports grants and personal fees from BioCryst during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from CSL Behring; personal fees from Kalvista; personal fees from Pharming; personal fees from Adverum; and grants and personal fees from Shire outside the submitted work. Dr. Lumry reports consultancy fees from BioCryst during the conduct of the study; nonfinancial support from Medical Advisory Board of US HAEA; other from Shire/Viropharma, Pharming, Adverum, and CSL Behring; research grants from Shire/Viropharma and CSL Behring; and speakers bureau honoraria and travel support from Shire/Viropharma, CSL Behring, and Pharming outside the submitted work. Dr Ritchie reports grants from BioCryst during the conduct of the study. Dr. Shapiro reports investigator and speaker; consultant fees from Shire; and investigator fees from GreenCross. Dr. Soteres reports other from BioCryst during the conduct of the study and other from BioCryst; personal fees and other from Shire; personal fees from CSL Behring; and personal fees from Pharming outside the submitted work. Dr. Banerji reports research grants and other from BioCryst during the conduct of the study; research grants and other from Shire; and other from CSL, Alnylam, and Pharming outside the submitted work. Dr Cancian reports grants from BioCryst during the conduct of the study. Dr. Johnston reports grants and personal fees from BioCryst, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Shire; personal fees from CSL Behring; personal fees from BioCryst; and personal fees from Pharming outside the submitted work. Dr. Craig reports grants and other from BioCryst, during the conduct of the study; other from CSL Behring; other from Shire; other from Grifols; other from Pharming; and other from HAE Association, outside the submitted work. Dr. Launay reports grants from BioCryst Pharmaceuticals; grants from Shire; and grants from CSL Behring, during the conduct of the study. Dr Li reports grants and nonfinancial support from BioCryst during the conduct of the study, and grants, personal fees, and nonfinancial support from Shire, CSL Behring, and Pharming outside the submitted work. Drs. Nickel and Schrijvers report other from BioCryst during the conduct of the study. Drs Offenberger, Rae, Triggiani, and Wedner report grants from BioCryst during the conduct of the study. S. Dobo, M. Cornpropst, D. Clemons, P. Collis, and W. Sheridan are employees of BioCryst. L. Fang reports consultancy fees from BioCryst. Dr. Maurer reports grants and personal fees from BioCryst during the conduct of the study, and grants and personal fees from BioCryst, Shire, Pharming, and CSL Behring outside the submitted work. There is no further conflict of interests to declare.

The sponsor provided research grant support to all investigators. All authors had access to all of the data in the study and approved the final published manuscript. The corresponding author had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

MR, E A‐P, SD, MC, DC, LF, PC, WPS, and MMaurer made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study and the analysis and interpretation of the data. MR, E A‐P, JB, HF, JA, JAB, LB, PB, MManning, MMagerl, MG, APH, HL, WL, BR, RS, DS, AB. MC, DTJ, DL, HHL, ML, TN, JO, WR, RS, MT, HJW, and MMaurer made substantial contributions to the acquisition of data. MR, E A‐P, PC, WPS, and M Maurer were responsible for drafting and/or revising the article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all of the patients and study teams for their commitment to this study and Aubri Charboneau and Caren Carver of Sage Scientific Writing, LLC for writing and editorial assistance.

Riedl MA, Aygören‐Pürsün E, Baker J, et al. Evaluation of avoralstat, an oral kallikrein inhibitor, in a Phase 3 hereditary angioedema prophylaxis trial: The OPuS‐2 study. Allergy. 2018;73:1871–1880. 10.1111/all.13466

Riedl and Aygören‐Pürsün equally contributed to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Longhurst H, Cicardi M. Hereditary angio‐oedema. Lancet. 2012;379:474‐481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kaplan AP, Joseph K. The bradykinin‐forming cascade and its role in hereditary angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;104:193‐204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kaplan AP. Enzymatic pathways in the pathogenesis of hereditary angioedema: the role of C1 inhibitor therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:918‐925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zuraw BL, Christiansen SC. Pathophysiology of hereditary angioedema. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2011;25:373‐378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nussberger J, Cugno M, Cicardi M. Bradykinin‐mediated angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:621‐622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lumry WR, Castaldo AJ, Vernon MK, Blaustein MB, Wilson DA, Horn PT. The humanistic burden of hereditary angioedema: impact on health‐related quality of life, productivity, and depression. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31:407‐414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Caballero T, Aygören‐Pürsün E, Bygum A, et al. The humanistic burden of hereditary angioedema: results from the Burden of Illness Study in Europe. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2014;35:47‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nordenfelt P, Dawson S, Wahlgren CF, Lindfors A, Mallbris L, Björkander J. Quantifying the burden of disease and perceived health state in patients with hereditary angioedema in Sweden. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2014;35:185‐190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aygören‐Pürsün E, Bygum A, Beusterien K, et al. Estimation of EuroQol 5‐Dimensions health status utility values in hereditary angioedema. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:1699‐1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cicardi M, Bork K, Caballero T, et al. Evidence‐based recommendations for the therapeutic management of angioedema owing to hereditary C1 inhibitor deficiency: consensus report of an International Working Group. Allergy. 2012;67:147‐157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maurer M, Magerl M. Long‐term prophylaxis of hereditary angioedema with androgen derivates: a critical appraisal and potential alternatives. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:99‐107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhang J, Krishnan R, Arnold CS, et al. Discovery of highly potent small molecule kallikrein inhibitors. Med Chem. 2006;2:545‐553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aygören‐Pürsün E, Magerl M, Graff J, et al. Prophylaxis of hereditary angioedema attacks: a randomized trial of oral plasma kallikrein inhibition with avoralstat. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:934‐936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Weller K, Groffik A, Magerl M, et al. Development and construct validation of the angioedema Quality of Life Questionnaire. Allergy. 2012;67:1289‐1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Weller K, Magerl M, Peveling‐Oberhag A, Martus P, Staubach P, Maurer M. The angioedema quality of life questionnaire (AE‐QoL) – assessment of sensitivity to change and minimal clinically important difference. Allergy. 2016;71:1203‐1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weller K, Groffik A, Magerl M, et al. Development, validation, and initial results of the angioedema activity score. Allergy. 2013;68:1185‐1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cornpropst M, Collis P, Collier J, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of avoralstat, an oral plasma kallikrein inhibitor: phase 1 study. Allergy. 2016;71:1676‐1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]