Abstract

Objective

To determine the efficacy of the addition of an ultrasound of the groins in routine follow up of women with vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) after a negative sentinel lymph node (SLN).

Design

Prospective single‐centre study.

Setting

A tertiary expert oncology centre for the treatment of vulvar cancer.

Population

All women with vulvar SCC with a negative SLN, treated between 2006 and 2014.

Methods

We prospectively collected data of 139 women with vulvar SCC treated with an SLN procedure. We analysed data of 76 patients with a negative SLN. Three‐monthly follow‐up visits consisted of physical examination combined with an ultrasound of the groins by a radiologist.

Main outcome measures

The diagnostic value of ultrasound in the follow up of women with vulvar SCC with a negative SLN during the first 2 years after treatment.

Results

During a routine visit, two asymptomatic isolated groin recurrences were detected. Both patients were treated by inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy and adjuvant radiotherapy and are alive without evidence of disease 39 and 120 months after diagnosis. In total, 348 ultrasounds and 29 fine‐needle aspiration were performed. The sensitivity of ultrasound to detect a groin metastasis was 100% (95% CI 16–100%), and specificity was 92% (95% CI 89–95%).

Conclusions

Routine follow up including ultrasound of the groin led to early detection of asymptomatic isolated groin recurrences. Further research is necessary to determine the exact role of ultrasound in the follow up of patients with vulvar SCC with a negative SLN.

Tweetable abstract

Routine follow up including ultrasound of the groin led to early detection of asymptomatic isolated groin recurrences.

Keywords: Follow up, groin recurrence, sentinel lymph node biopsy, ultrasonography, vulvar squamous cell carcinoma

Tweetable abstract

Routine follow up including ultrasound of the groin led to early detection of asymptomatic isolated groin recurrences.

Introduction

The sentinel lymph node (SLN) procedure has been integrated as standard care for a subgroup of patients with early‐stage vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) after the publication of the GROINSS‐V‐I and GOG‐173 studies.1, 2 If the SLN contains metastatic tumour, an inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy (IFL) is indicated. In patients with a negative SLN, close follow up is advised with the primary aim to identify locoregional recurrences as early as possible.

The largest long‐term follow‐up study of 377 patients with an SLN for primary vulvar SCC showed isolated groin recurrences in 2.3% of the SLN‐negative patients.3 In smaller, mainly retrospective, studies, the isolated groin recurrence rate varied between zero and 6.6%.4, 5

The main purpose of close follow up in patients with a negative SLN was to detect groin recurrence in asymptomatic patients as early as possible to achieve better survival, preferably with limited morbidity. As lymph node palpation is difficult to interpret for small nodes, especially in people who are overweight, the question arises whether an ultrasound of the groins during follow up has additional value for early detection of a groin recurrence.

There was no literature evaluating the additional value of ultrasound in the follow up of women with vulvar SCC with a negative SLN. The current guidelines for follow up after the SLN procedure in vulvar SCC are based on expert opinions rather than evidence. The Dutch guideline and The European Society of Gynaecological Oncology recommend follow up in the first 2 years, including clinical examination of the groins, but do not mention routine use of imaging of the groins.6, 7 Furthermore, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists states that recognition of recurrence as early as possible seems logical because salvage is largely dependent on either further excision or radiotherapy. However, there are no recommendations on performing an ultrasound or not.8 This implies the need for more knowledge with respect to the efficacy of an ultrasound of the groin in the follow up after a negative SLN in patients with vulvar SCC.

The primary aim of this study was to determine the diagnostic value of ultrasound in the follow up of women with vulvar SCC with a negative SLN during the first 2 years after treatment. Furthermore, our secondary aims were to determine the adherence to the follow‐up protocol and to estimate the costs of performing ultrasound for the detection of a recurrence.

Methods

A prospective study was performed at the Radboud University Medical Center, which is an expert centre for the treatment of vulvar cancer. In 2006, with the knowledge of the preliminary results of the GROINSS‐V‐I study (2–3% groin recurrences with poor prognosis) combined with the evidence for an ultrasound in the preoperative assessment of the lymph node status, we decided to add ultrasound of the groin to the routine follow up of patients with a negative SLN. We prospectively stored data of patients treated with an SLN from 2006 until the moment of closure (end of 2016) of the GROINSS‐V‐II study (NCT01500512) in an electronic database.

We selected patients if they met all of the following inclusion criteria: (1) primary unifocal macroinvasive vulvar SCC with a diameter of < 4 cm and clinically nonsuspicious groin lymph nodes by palpation and without abnormality at ultrasound and/or fine‐needle aspiration cytology (FNAC), (2) SLN treatment between 2006 and 2014, and (3) unilateral negative SLN after a unilateral procedure or bilateral negative SLN after a bilateral procedure.

Patients were not engaged in the development of our study. The local ethical committee of the Radboud University Medical Center approved this study (reference number 2017‐3191). There was no funding for this study.

A unilateral SLN procedure was performed in patients with lateralised tumours (≥ 1 cm from midline) and ipsilateral lymph flow on lymphoscintigraphy; in all other patients, a bilateral SLN procedure was performed. The procedure was performed using the combined technique (radioactive tracer and blue dye) to identify the SLNs as described previously.9 The removed SLNs were histopathologically examined by an expert gynaecological pathologist, including ultrastaging if necessary.1 Patients with a (unilateral) positive SLN(s) had an indication for further therapy of both groins.

Routine follow up consisted of a 3‐monthly visit at the outpatient clinic within the first 2 years after the SLN procedure. These visits included gynaecological examination with palpation of the groins by the gynaecologist and a routine ultrasound by the radiologist. In patients with a unilateral SLN procedure, both groins were examined during follow up. For logistical reasons, either the palpation or the ultrasound was performed first. After the first 2 years, follow up is less frequent (twice a year) without the performance of a routine ultrasound of the groin.

The ultrasound of the groin was performed by our ultrasound unit at the Department of Radiology. This is an expert centre with a dedicated team of professionals for the performance of ultrasounds for different types of cancer.

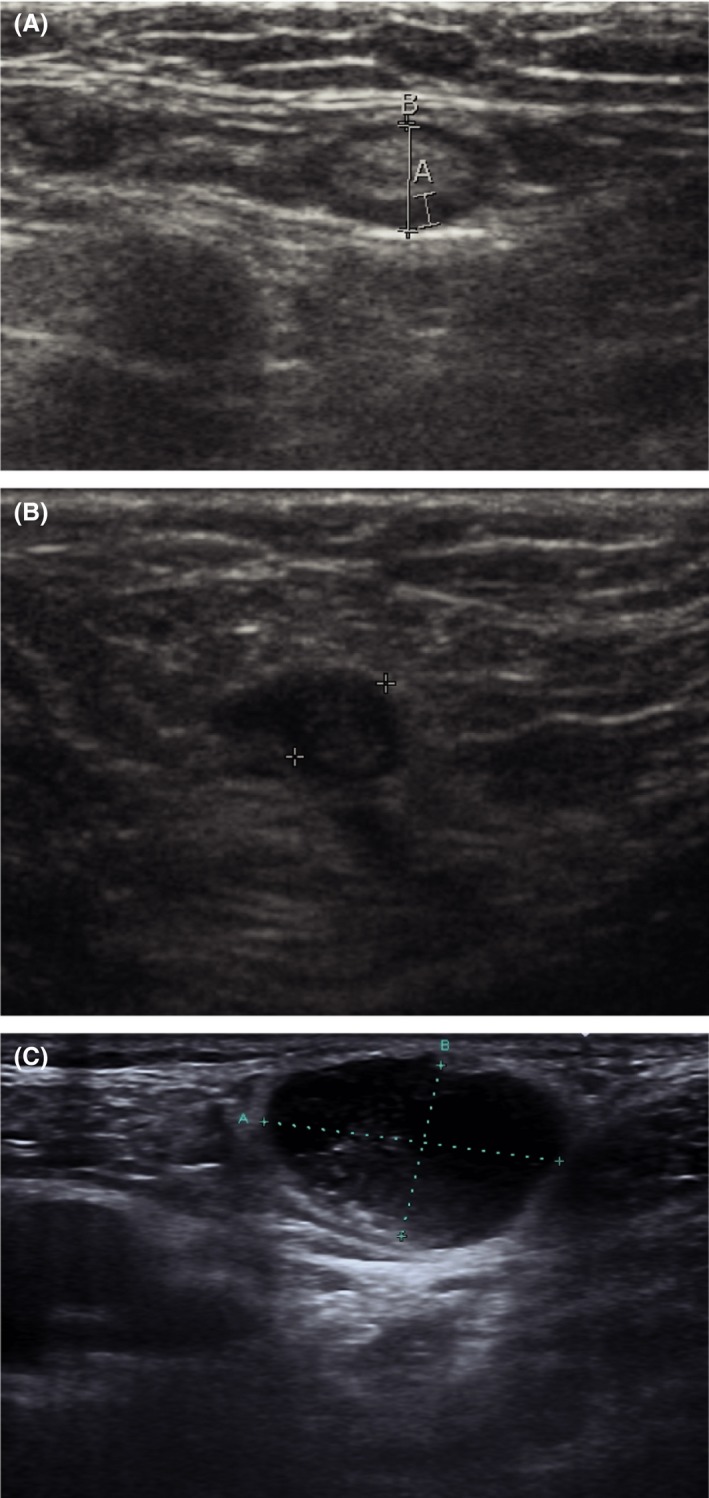

Suspicious lymph nodes on ultrasound were characterised by a short‐axis diameter ≥ 10 mm in oval‐shaped lymph nodes or ≥ 8 mm in circular‐shaped lymph nodes with a malignant aspect. Malignant aspects visualised by ultrasound are hilar hypoechogenicity, general attenuation, irregularity of the margin, or abnormal vascular pattern on Doppler (see Figure 3A–C). If a suspicious lymph node for metastasis was present, FNAC was performed in the same session.

Figure 3.

Ultrasound images. (A) Ultrasound image of a normal lymph node in the groin (measurement A: 1.4 mm, B: 4.6 mm). (B) Ultrasound image of a metastatic lymph node (patient A): enlarged (diameter 5.9 mm), focal cortical thickening on the left side and loss of echogenic hilar sinus fat. (C) Ultrasound image of a metastatic lymph node (patient B): enlarged oval‐shaped, loss of echogenic hilar sinus fat (measurement A: 23.1 mm, B: 14.3 mm).

An isolated groin recurrence was defined as a histologically proven metastasis of vulvar SCC in a lymph node in the groin, without a simultaneous local recurrence. In all patients with an isolated groin recurrence, we reviewed the indication for the SLN procedure and the technical aspects of the procedure itself, and an expert pathologist reviewed the pathological slides of the SLN(s).

Cost analysis

In our medical centre, the cost of the radiologist performing an ultrasound is €75, independent of inspecting one or both groins. A FNAC costs €329, including histopathological examination.

Statistical analysis

The start of the routine follow up was defined as the date of the SLN procedure. All routine and indicated visits during the follow‐up period, starting at 2.5 months and going to 25.5 months after the SLN procedure, were included for analyses. Not all visits took place exactly at the planned time. In the analysis, we assigned the data to the nearest targeted visit moment, using a time window of 3 months; visits occurring from 1.5 months before the planned moment of visit till 1.5 months after the planned moment of visit (that is, all results from the period between 4.5 and 7.5 months) were analysed as the 6‐month visit. Only the result of the first visit, planned at month 3, was based on a shorter time window, as data were included from 2.5 months till 4.5 months after the SLN procedure.

The duration of total follow up was defined as date of the SLN procedure until date of last follow up or death.

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of the ultrasound and FNAC were calculated, and the Clopper–Pearson exact method was used to determine the 95% CI.10 The test characteristics of palpation of the groin were not the aim of this study. A positive ultrasound (the presence of suspicious lymph nodes) and a positive FNAC were considered as truly positive if histopathological examination of the lymph nodes retrieved by IFL showed metastatic disease. A negative ultrasound or FNAC was considered as truly negative if there was no evidence of metastatic disease in the groin after at least 1 year of follow up.

Analyses were performed with SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).11

Results

Patient characteristics

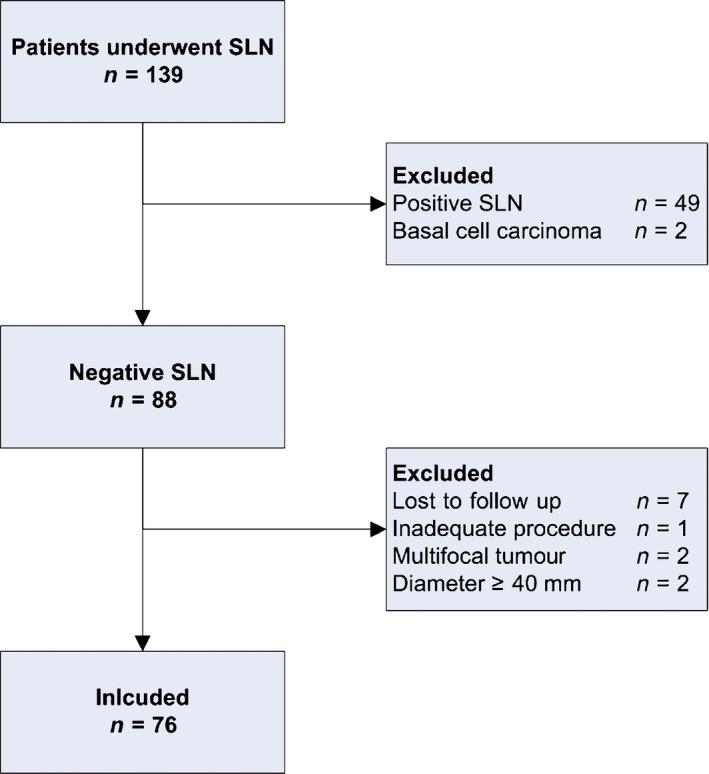

As shown in Figure 1, 139 women underwent an SLN procedure between 2006 and 2014. We excluded 49 patients because of a unilateral or bilateral positive SLN, two patients because definitive histopathological examination showed basal cell carcinoma, and another 12 patients were excluded because they had a multifocal/larger tumour, a technical inadequate SLN procedure, or were lost to follow up. In conclusion, we analysed data of 76 women with a negative SLN.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. SLN, sentinel lymph node; n, number of patients.

The median age was 67 years (range 37–89 years), and the median body mass index was 25.6 kg/m2 (range 16.5–36.1 kg/m2). A bilateral SLN procedure was performed in 58 patients; a unilateral procedure was performed in 18 patients. The median number of dissected nodes was three (range one to seven nodes) per patient after a bilateral SLN procedure and two (range one to four nodes) after a unilateral procedure. Median total follow‐up time was 47 months (range 3–142 months). For patient and tumour characteristics, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient and tumour characteristics

| Patient and tumour characteristics | Median (range) | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 67 (37–89) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.5 (16.5–36.1) | |

| FIGO stage (2009) | ||

| IA | 1 (1) | |

| IB | 75 (99) | |

| Localisation | ||

| Central | 58 (76) | |

| Lateral (≥ 1 cm from midline) | 18 (24) | |

| Tumour diameter (mm) | 14.5 (1.0–40.0) | |

| Depth of invasion (mm) | 3.0 (1.0–13.2) | |

| Grade of differentiation | ||

| I | 25 (33) | |

| II | 43 (57) | |

| III | 8 (10) | |

| Number of dissected sentinel nodes per patient | ||

| Bilateral procedure | 3 (1–7) | |

| Unilateral procedure | 2 (1–4) | |

Protocol adherence

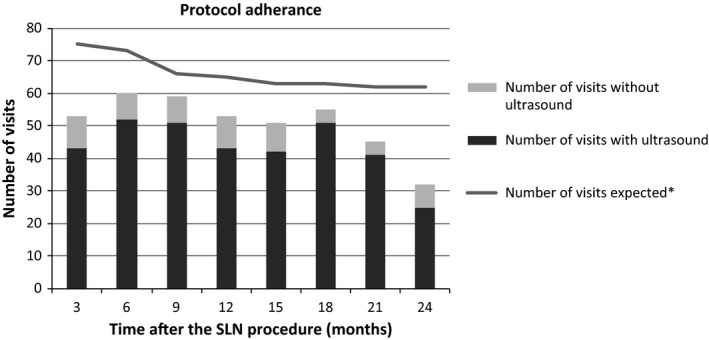

Based on a schedule of 3‐monthly routine visits during 2 years, the planned number of routine visits would be 608 (76 × 8). Due to shorter follow up of patients who died or for whom vulvar cancer recurrence was detected, the expected number of planned routine visits was 529. In total, 408 (77% of expected) follow‐up visits were performed, of which 403 were routine and five were interval visits because of complaints. Figure 2 shows the expected number of visits and the performed number of visits with and without an ultrasound per time period after the SLN procedure.

Figure 2.

Protocol adherence. *Number of expected visits was corrected for the actual follow‐up time of each patient by taking into consideration the date of death or detection of a vulvar cancer recurrence.

During the first year, 225/279 (81%) of the expected visits were performed compared with 183/250 (73%) in the second year.

The median number of performed follow‐up visits was seven (range zero to eight visits) per patient. Four patients did not show up at any follow‐up visit for different reasons: one patient had a local recurrence within 3 months after the SLN procedure, two patients chose not to participate, and in one patient, the reason is unknown.

As shown in Table 2, in 348 of the 408 (85%) visits, an ultrasound was performed; 29 (8%) ultrasounds showed one or more suspicious lymph nodes in the groin(s). As a consequence, an FNAC was performed of all suspected lymph nodes. In one patient, cytological examination was inconclusive; however, there was no evidence of a groin recurrence during a follow up at 92 months, and therefore, the FNAC was considered to be negative. In two patients, cytological examination of the FNAC showed a groin recurrence (see Isolated groin recurrences). In both patients, an ultrasound was performed during a routine follow‐up visit and a suspicious lymph node was identified in the groin, and a subsequent FNAC was performed. However, in one patient, there was a suspected lymph node in the groins at palpation. All ultrasound and/or FNAC‐negative patients were followed for at least one additional year and did not show a groin recurrence.

Table 2.

Summary of results of palpation, ultrasound, and fine‐needle aspiration cytology

| Time after SLN procedure in months | Number of visits | Number of patients with suspicious groins by palpation | Number of patients in which ultrasound was performed | Number of patients with suspicious lymph nodes on ultrasound | Number of patients in which FNAC was performed | Number of patients with positive cytologyf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 53 | 2a | 43 | 6d | 6d | 1 |

| 6 | 60 | 3b | 52 | 4e | 4e | 1 |

| 19 | 59 | 3b | 51 | 7e | 7e | 0 |

| 12 | 53 | 4c | 43 | 3d | 3d | 0 |

| 15 | 51 | 1a | 42 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| 18 | 55 | 3c | 51 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| 21 | 45 | 2a | 41 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| 24 | 32 | 1a | 25 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 408 | 19 | 348 | 29 | 29 | 2 |

FNAC, fine‐needle aspiration cytology; SLN, sentinel lymph node.

In all patients also suspicious on ultrasound.

In one patient not suspicious on ultrasound.

In two patients not suspicious on ultrasound.

In two patients bilateral.

In one patient bilateral.

For more detailed information, see Table 3.

Isolated groin recurrences

Using ultrasound, isolated groin recurrence of the vulvar SCC was diagnosed in two of 76 patients (2.6%); both recurrences were diagnosed within 8 months after the SLN procedure during a routine follow‐up visit (Table 3). Groin recurrence did not occur in any of the other patients.

Table 3.

Characteristics of women with an isolated groin recurrence

| Patient characteristics | Patient A | Patient B |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 60 | 77 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.1 | 23.5 |

| Primary tumour | ||

| Tumour localisation | Lateral, left | Midline |

| FIGO stage | IB | IB |

| Tumour diameter (mm) | 5 | 20 |

| Depth of invasion (mm) | 4.3 | 8.0 |

| Grade of differentiation | I | II |

| Primary treatment | ||

| Procedure adequate after revision | Yes | Yes |

| Dissected SLNs | ||

| Left | 2 | 1 |

| Right | – | 2 |

| Isolated groin recurrence | ||

| Groin recurrence | Right | Right |

| Time to recurrence (months) | 3.8 | 7.4 |

| Moment of diagnosis | Routine visit | Routine visit |

| Complaints | No | No |

| Palpable suspicious lymph nodes | No | Yes, right |

| Number of lymph node metastases | 1 | 1 |

| Diameter lymph node metastasis (mm) | 7 | 34 |

| Extranodal growth | No | No |

| Treatment | ||

| Bilateral inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy | ||

| Number of lymph nodes removed right (number of lymph nodes with metastatic disease) | 9 (1) | 17 (1) |

| Number of lymph nodes removed left (number of lymph nodes with metastatic disease) | 6 (0) | 11 (0) |

| Adjuvant radiotherapy | Yes | Yes |

| Survival | ||

| Patient status | Alive without evidence of disease (120 months) | Alive without evidence of disease (39 months) |

One woman (see Table 3, patient A) was diagnosed with a lateralised tumour (≥ 1 cm from midline) on the left side of the vulva; during clinical examination and an ultrasound of both groins, there was no suspicious lymph node identified, and a unilateral SLN procedure was performed; the lymphoscintigram showed ipsilateral lymph flow, and two SLNs were identified and removed. The SLN procedure was adequate, and no substandard factors could be identified afterwards. The patient went for a routine follow‐up visit 4 months after treatment, she had no complaints, and no abnormal lymph nodes were palpated by the gynaecologist. However, ultrasound showed one suspicious lymph node in the contralateral groin (see Figure 3B) and FNAC was performed; cytological examination showed SCC.

Treatment consisted of bilateral IFL. Histopathological examination showed five lymph nodes in the left side without evidence of disease and eight lymph nodes in the right groin; in one lymph node there was a metastasis of the known vulvar SCC, with a diameter of 7 mm without extranodal growth. Cloquet's node from both the left and right did not contain metastatic disease. Adjuvant radiotherapy was given. This patient is alive without evidence of disease 120 months after the diagnosis of the groin recurrence.

Another woman (see Table 3, patient B) was diagnosed with a midline tumour, without suspicious groin lymph nodes by palpation and ultrasound, and was treated by a bilateral SLN procedure; in total, three SLNs were identified and removed. The procedure was adequate, and no substandard factors could be identified afterwards. However, 8 months later, this patient visited the outpatient clinic for routine follow up. The gynaecologist identified a suspicious lymph node in the right groin at palpation, and subsequently, an ultrasound of both groins was performed. This ultrasound showed one suspicious lymph node in the right groin (see Figure 3C) and one suspicious lymph node in the left groin; a FNAC of both lymph nodes was performed. Cytological examination showed malignant cells that fitted with SCC in the right groin; no evidence of malignant disease was seen in the cytological material of the left groin.

Bilateral IFL was performed and histopathological examination showed 17 lymph nodes from the right groin, with one lymph node metastasis measuring 34 mm without extranodal growth. Examination of the removed tissue of the left groin showed 11 lymph nodes, without metastatic disease. Adjuvant radiotherapy was performed, and the patient is without evidence of disease 39 months after the groin recurrence.

Test characteristics

Test characteristics of the ultrasound in the follow up were as follows: the sensitivity of ultrasound to detect a groin metastasis was 100% (2/2; 95% CI 16–100%), the specificity was 92% (319/346; 95% CI 89–95%), PPV 6.8% (2/29; 95% CI 0.9–23%), and NPV 100% (346/346; 95% CI 99–100%).

For paired ultrasound and FNAC (FNAC after a positive ultrasound), the sensitivity was 100% (2/2; 95% CI 16–100%), specificity was 100% (27/27; 95% CI 87–100%), and both PPV and NPV were 100% (PPV: 2/2; 95% CI 16–100%; NPV: 27/27; 95% CI 87–100%).

Costs

In this study, one isolated nonpalpable groin recurrence was identified by the routine ultrasound of the groin. The other groin recurrence would have been detected by a follow‐up regimen without a routine ultrasound of the groin, as this recurrence was palpable during clinical examination. The detection of the nonpalpable asymptomatic groin recurrence required 348 ultrasounds (€26 100) and a FNAC in 29 patients (€9541), generating total costs of €35 641. This results in additional costs of €469 per patient.

Discussion

Main findings

We evaluated the diagnostic value of ultrasound of the groins in the follow up of 76 women with vulvar SCC after a negative SLN. Routine ultrasound in the follow up during the first 2 years resulted in the early diagnosis of one asymptomatic, nonpalpable groin recurrence. In our study, 348 ultrasounds and a FNAC in 29 patients were necessary to detect this recurrence. The sensitivity of ultrasound to detect a groin metastasis was 100% (95% CI 16–100%) and specificity was 92% (95% CI 89–95%).

Strengths and limitations

Our prospective study is the first determining the efficacy of ultrasound in the follow up of patients after a negative SLN. In addition to obvious limitations, such as low number of patients and low number of events, the single‐centre design is a possible drawback. Furthermore, the ultrasounds were performed by different radiologists working in our specialised ultrasound unit; this may have introduced bias because ultrasound examination and interpretation of the ultrasound features as the indication for a metastatic lymph node are radiologist‐dependent. However, this reflects daily clinical practice. Furthermore, the cost analyses are performed with the costs of an ultrasound and FNAC at our Dutch medical centre and therefore may not be reproducible for all medical centres in other countries.

Interpretation

A groin recurrence in patients with vulvar SCC is nearly always fatal; published literature reports a 5‐year survival of only 0–10%.12, 13, 14, 15 More recently, a 7‐year survival of 50% was reported in one study;16 this retrospective study described all 30 patients treated for a groin recurrence (isolated or a groin and pelvic recurrence). Primary groin treatment could be either an IFL or an SLN. Follow up consisted of clinical examination and, if needed, imaging of the groin.

The reported 7‐year survival of 50% is much higher than the previously reported 0–10%.12, 13, 14, 15, 16 This might imply that patients with a groin recurrence after a negative SLN procedure may have a better prognosis compared with patients with a groin recurrence after an IFL. This difference may be explained by either the (multimodal) treatment options available and/or pathogenesis. An isolated groin recurrence after an IFL can be caused by in‐transit metastases in lymph channels, as all lymph nodes are removed. On the contrary, an isolated groin recurrence after an SLN is more likely to be the result of remaining (isolated) tumour cells in the lymph nodes, probably with less spread outside the lymph node. However, all patients with a groin recurrence after a negative SLN in the GROINSS‐V‐I study, in whom follow up only consisted of palpation of the groin, died of disease.3 In contrast, in our study, both patients with a groin recurrence are still alive. Therefore, early detection and resection of a groin recurrence, for example, by routine ultrasound, may be of importance for improved survival.

In patients with penile SCC, the effect of early versus late resection of lymph node metastases was evaluated.17 This study retrospectively selected 40 patients with clinically node‐negative groin lymph node metastases treated with lymphadenectomy. The first 20 patients were treated with a ‘wait and see’ policy and strict follow up; when the lymph node(s) became clinically apparent and metastases were cytologically proven, lymphadenectomy was performed. The other 20 patients were treated using the SLN procedure, and if a positive SLN was present, an additional lymphadenectomy was performed. The disease‐specific 3‐year survival of the first group was 35% versus 84% for the second group (P = 0.0017). These results underline the importance of early diagnosis and resection of groin lymph node metastases.

Besides, the SLN procedure is also common practice in breast cancer patients. In these patients, the axillary recurrence rate after a negative SLN is only 0.3%.18 This is much lower compared with vulvar SCC and might be explained by differences in treatment; breast cancer patients more often receive (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy after a negative SLN. Furthermore, Leikola et al. concluded that, due to the low incidence of axillary recurrence, routine ultrasound of the axilla after a negative SLN was unlikely to be cost‐effective.19

We diagnosed two isolated groin recurrences within 8 months after the SLN procedure; one might question if the lymph node metastases have been missed in preoperative workup and/or the SLN was false negative. In‐depth analyses of the indication for this SLN procedure, the preoperative workup and the procedure itself, revealed no substandard factors. Therefore, these isolated groin recurrences may be the result of a false‐negative SLN, in which (isolated) tumour cells have not been identified.

In our study, both patients with a groin recurrence were asymptomatic and, remarkably, both patients are still alive without evidence of disease. Since the number of patients with a groin recurrence in our study was small, we were not able to calculate quality‐adjusted life years (QALY) and perform a cost‐effectiveness analysis. However, the ultrasound in patient A detected a nonpalpable groin recurrence, and this patient is still alive 10 years after diagnosis. The costs for the ultrasounds and subsequent FNACs were €35 641. Given the fact that patient A survived at least 10 years after diagnosis of the groin recurrence, the accepted threshold (in the Netherlands) of €50 000 per QALY is by far not reached.

To minimise the possible burden for the patient of a false‐positive ultrasound and the subsequent ‘unnecessary’ FNAC, ultrasound features that most accurately identify groin lymph node metastasis should be identified. In patients with breast cancer, ultrasound of the lymph nodes in the axilla to identify metastatic lymph nodes is frequently performed. In these patients, cortical thickness (with a 3 mm cut‐off) is shown to be the most reliable ultrasound feature predicting a lymph node metastasis.20, 21, 22 This characteristic is not routinely used in the evaluation of groin lymph nodes in patients with vulvar cancer but might be an option.

Future follow‐up schedules should be personalised and risk‐based; this can be based on body mass index, as this patient‐related factor can negatively influence the detection of a (small) groin recurrence by palpation. More research is needed to identify patients at high risk for a groin recurrence to offer a personalised risk‐based follow up.

The best way to evaluate the value of using ultrasound in terms of better survival is a randomised controlled trial comparing a follow‐up protocol with and without routine ultrasound. However, such a trial is not realistic given the low incidence of vulvar SCC on the one hand and the limited number of groin recurrences on the other. The most suitable design is a prospective multicentre phase II study. Furthermore, with current concerns over rising healthcare costs, further evaluation is needed to determine the most cost‐effective evidence‐based follow‐up schedule for patients with a negative SLN.

Conclusion

The performance of a routine ultrasound in the follow up of 76 women with vulvar SCC with negative SLNs resulted in the early diagnosis of one nonpalpable groin recurrence; this patient is still alive without evidence of disease 10 years after diagnosis. In our study, 348 ultrasounds and 29 FNACs were performed to detect this recurrence. In our view, this is counterbalanced by the earliest possible detection of groin recurrences leading to the best possible survival for the individual patient.

Disclosure of interest

None declared. Completed disclosure of interests form available to view online as supporting information.

Funding

None.

Contribution to authorship

AP, AvZ, LM, and JdH contributed to conceptualisation; AP, RM, JiH, AvZ, JB, LM, and JdH contributed to methodology; AP, RM, JiH, and JdH performed analysis; and AP, RM, JiH, AvZ, JB, LM, and JdH wrote the manuscript.

Supporting information

Acknowledgements

We thank Rosanne de Graaf, Julia Hulsmann, and Mara de Vries for their help with data collection.

Pouwer AW, Mus RDM, IntHout J, van der Zee AGJ, Bulten J, Massuger LFAG, de Hullu JA. The efficacy of ultrasound in the follow up after a negative sentinel lymph node in women with vulvar cancer: a prospective single‐centre study. BJOG 2018; 125:1461–1468.

References

- 1. Van der Zee AG, Oonk MH, De Hullu JA, Ansink AC, Vergote I, Verheijen RH, et al. Sentinel node dissection is safe in the treatment of early‐stage vulvar cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:884–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Levenback CF, Ali S, Coleman RL, Gold MA, Fowler JM, Judson PL, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy in women with squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:3786–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Te Grootenhuis NC, van der Zee AG, van Doorn HC, van der Velden J, Vergote I, Zanagnolo V, et al. Sentinel nodes in vulvar cancer: long‐term follow‐up of the GROningen INternational Study on Sentinel nodes in Vulvar cancer (GROINSS‐V) I. Gynecol Oncol 2016;140:8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moore RG, Robison K, Brown AK, DiSilvestro P, Steinhoff M, Noto R, et al. Isolated sentinel lymph node dissection with conservative management in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: a prospective trial. Gynecol Oncol 2008;109:65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Robison K, Roque D, McCourt C, Stuckey A, DiSilvestro PA, Sung CJ, et al. Long‐term follow‐up of vulvar cancer patients evaluated with sentinel lymph node biopsy alone. Gynecol Oncol 2014;133:416–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oonk MHM, Planchamp F, Baldwin P, Bidzinski M, Brannstrom M, Landoni F, et al. European Society of Gynaecological Oncology guidelines for the management of patients with vulvar cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2017;27:832–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oncoline . Vulvacarcinoom [updated 2011‐05‐02. Version 2.1]. [http://www.oncoline.nl/vulvacarcinoom] Accessed 29 May 2018.

- 8. Gynaecologists RCoO . Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of vulval carcinoma 2014. [https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/vulvalcancerguideline.pdf] Accessed 29 May 2018.

- 9. de Hullu JA, Hollema H, Piers DA, Verheijen RH, van Diest PJ, Mourits MJ, et al. Sentinel lymph node procedure is highly accurate in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:2811–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brown L, Cat TT, DasGupta A. Interval estimation for a proportion. Stat Sci 2001;16:101–33. [Google Scholar]

- 11. IBM. Corp . IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.; Released 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nooij LS, Brand FA, Gaarenstroom KN, Creutzberg CL, de Hullu JA, van Poelgeest MI. Risk factors and treatment for recurrent vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol/Hemat 2016;106:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cormio G, Loizzi V, Carriero C, Cazzolla A, Putignano G, Selvaggi L. Groin recurrence in carcinoma of the vulva: management and outcome. Eur J Cancer Care 2010;19:302–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hopkins MP, Reid GC, Morley GW. The surgical management of recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol 1990;75:1001–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Simonsen E. Treatment of recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Acta radiologica Oncol 1984;23:345–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frey JN, Hampl M, Mueller MD, Gunthert AR. Should groin recurrence still be considered as a palliative situation in vulvar cancer patients? A brief report. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2016;26:575–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kroon BK, Horenblas S, Lont AP, Tanis PJ, Gallee MP, Nieweg OE. Patients with penile carcinoma benefit from immediate resection of clinically occult lymph node metastases. J Urol 2005;173:816–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van der Ploeg IM, Nieweg OE, van Rijk MC, Valdes Olmos RA, Kroon BB. Axillary recurrence after a tumour‐negative sentinel node biopsy in breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of the literature. Eur J Surg Oncol 2008;34:1277–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leikola J, Saarto T, Joensuu H, Sarvas K, Vironen J, Von Smitten K, et al. Ultrasonography of the axilla in the follow‐up of breast cancer patients who have a negative sentinel node biopsy and who avoid axillary clearance. Acta Oncol (Stockholm, Sweden) 2006;45:571–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Choi YJ, Ko EY, Han BK, Shin JH, Kang SS, Hahn SY. High‐resolution ultrasonographic features of axillary lymph node metastasis in patients with breast cancer. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2009;18:119–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mainiero MB, Cinelli CM, Koelliker SL, Graves TA, Chung MA. Axillary ultrasound and fine‐needle aspiration in the preoperative evaluation of the breast cancer patient: an algorithm based on tumor size and lymph node appearance. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010;195:1261–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Deurloo EE, Tanis PJ, Gilhuijs KG, Muller SH, Kroger R, Peterse JL, et al. Reduction in the number of sentinel lymph node procedures by preoperative ultrasonography of the axilla in breast cancer. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990). 2003;39:1068–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials